Implementation of Canada’s Patent Linkage System: Balancing Innovation and Market Access

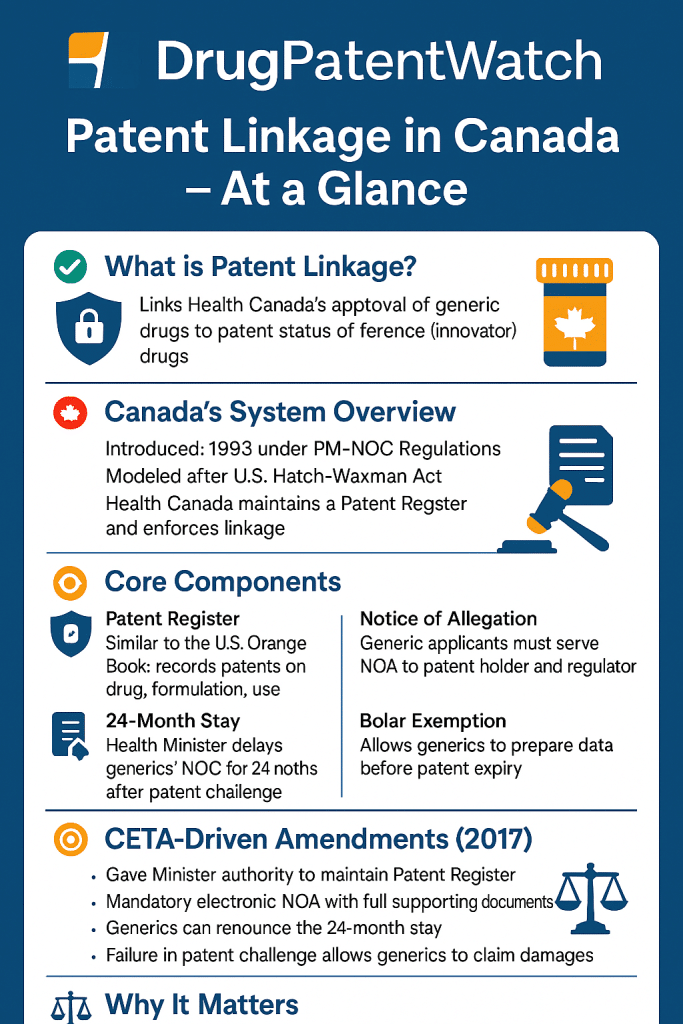

Canada’s patent linkage system represents a critical intersection of intellectual property law and pharmaceutical regulation, designed to balance the rights of patent holders with the timely entry of generic medications into the market. Established under the Patented Medicines (Notice of Compliance) Regulations (PMNOC Regulations), this framework ties regulatory approval of generic and biosimilar drugs to the resolution of patent disputes, ensuring that intellectual property rights are upheld without unduly delaying competition. Recent amendments, particularly those implemented in 2017, have refined the system to align with international trade agreements like the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), introducing procedural reforms to enhance fairness and efficiency[5][7].

Legal Framework and Legislative Evolution

Historical Context and Early Regulations

Canada’s patent linkage system originated in the early 1990s as part of broader reforms to pharmaceutical regulation. The PMNOC Regulations, enacted under Section 55.2(4) of the Patent Act, were initially modeled after the U.S. Hatch-Waxman Act but diverged significantly in practice[1][3]. The original system allowed innovators to list patents on a public register managed by Health Canada, known as the Patent Register. Generic manufacturers seeking approval for their products were required to address these patents through a “notice of allegation” (NOA), asserting either non-infringement or invalidity[4][12]. However, early iterations of the PMNOC Regulations faced criticism for procedural inefficiencies, including prolonged summary proceedings and a dual-track litigation system that allowed redundant lawsuits[5][13].

The 2017 Amendments and CETA Compliance

In September 2017, substantial amendments to the PMNOC Regulations took effect, driven by Canada’s obligations under CETA. These changes replaced summary proceedings with full patent infringement actions, granting both innovators and generics the right to appeal decisions and introducing live testimony during trials[5][7]. The reforms aimed to eliminate the dual-track system, where patent disputes could be litigated simultaneously under the PMNOC Regulations and the Patent Act, which often led to conflicting outcomes and strategic delays[5][13]. Notably, the 2017 amendments also established Certificates of Supplementary Protection (CSPs), extending patent terms by up to two years to compensate for regulatory approval delays[2][8].

Structural Components of the Patent Linkage System

The Patent Register and Eligibility Criteria

At the core of Canada’s system lies the Patent Register, a searchable database maintained by Health Canada that lists patents relevant to approved drugs. To qualify for listing, a patent must contain at least one claim covering the medicinal ingredient, formulation, dosage form, or approved use of the drug[4][8]. Innovators must submit a “Form IV: Patent List” alongside their regulatory submission for market approval, with late additions permitted within 30 days of patent issuance[8][10]. This requirement ensures that only patents directly related to the commercialized product are included, preventing “evergreening” tactics aimed at unjustly extending monopolies[3][12].

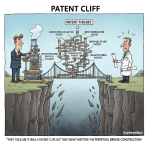

Certificates of Supplementary Protection (CSPs)

Introduced as part of CETA compliance, CSPs provide up to 24 months of additional market exclusivity for drugs facing regulatory approval delays. Eligible patents must pertain to new medicinal ingredients or combinations, with CSPs extending protection beyond the original patent expiry date[2][8]. Unlike the U.S. system, which offers up to five years of exclusivity for new chemical entities, Canada’s CSP framework is narrower, reflecting a deliberate balance between incentivizing innovation and facilitating generic entry[3][11].

Procedural Mechanisms and Litigation Process

Notice of Allegation (NOA) and Judicial Review

When a generic manufacturer files a submission referencing an innovator’s drug, it must serve an NOA to the patent holder, detailing its grounds for alleging non-infringement or invalidity[4][13]. The innovator then has 45 days to initiate a judicial review in the Federal Court, triggering an automatic 24-month stay on generic approval[1][11]. This stay period, shorter than the 30-month stay under Hatch-Waxman, is designed to expedite resolution while providing sufficient time for evidence gathering and expert testimony[1][7].

Trial Proceedings and Evidence Standards

Post-2017, PMNOC litigation follows procedures akin to traditional patent infringement actions, including documentary disclosures, examinations for discovery, and live witness testimony[5][7]. Unlike U.S. district courts, Canadian courts do not conduct Markman hearings for claim construction, relying instead on early claim charts and written arguments[1][7]. The burden of proof rests with the plaintiff (innovator) to demonstrate infringement on a balance of probabilities, while the defendant (generic) must prove invalidity under the same standard[1][13]. This contrasts with the U.S. system, where invalidity requires “clear and convincing evidence”[1][11].

Comparative Analysis with International Systems

Key Differences from the U.S. Hatch-Waxman Act

While Canada’s system shares foundational principles with Hatch-Waxman, critical distinctions exist:

– Patent Listing Requirements: Canada’s Patent Register excludes method-of-manufacture patents and imposes stricter relevance criteria, limiting the scope of eligible patents compared to the U.S. Orange Book[1][11].

– Statutory Stay Duration: The 24-month stay in Canada is shorter than the 30-month period in the U.S., reflecting a policy preference for faster generic entry[1][7].

– Litigation Finality: Post-2017, Canadian court decisions under the PMNOC Regulations are binding on subsequent litigation, eliminating the risk of duplicative lawsuits—a persistent issue in the U.S. dual-track system[5][7].

Alignment with Global Best Practices

Canada’s framework incorporates elements from both U.S. and European models. The CSP system mirrors the Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) used in the EU, while the emphasis on single-action litigation aligns with CETA’s demand for “equivalent and effective rights of appeal”[5][7]. However, Canada’s exclusion of biologics from certain provisions, unlike the U.S. Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), highlights ongoing gaps in addressing advanced therapies[1][8].

Impact and Criticisms

Balancing Innovation and Access

Proponents argue that the PMNOC Regulations strike an equitable balance by safeguarding patent rights without unduly delaying generics. The 2017 amendments, in particular, have reduced average litigation timelines from 36 months to under 24 months, enhancing market predictability[5][7]. However, critics contend that CSPs and stringent patent listing requirements disproportionately favor innovators, citing Canada’s stagnant pharmaceutical R&D investment compared to global peers[3][8].

Administrative and Procedural Challenges

Health Canada’s Office of Patented Medicines and Liaison (OPML) faces ongoing challenges in auditing the Patent Register, with concerns about overlisting and procedural complexity[10][12]. Generic manufacturers have criticized the 45-day response window for judicial review as overly restrictive, arguing that it pressures innovators to file premature lawsuits[11][13].

Recent Developments and Future Directions

2021 Regulatory Updates

Further amendments in April 2021 clarified the Minister of Health’s role in maintaining the Patent Register, emphasizing transparency and public accessibility[6][10]. These changes also streamlined the process for removing improperly listed patents, addressing longstanding concerns about register accuracy[6][12].

Emerging Issues in Biologics and Biosimilars

As biologics dominate pharmaceutical innovation, Canada’s failure to fully integrate biosimilars into the PMNOC framework has drawn scrutiny. Unlike small molecules, biosimilars face no statutory stay under the current regulations, creating uncertainty for manufacturers and potentially discouraging investment[1][8].

Conclusion

Canada’s patent linkage system has evolved into a sophisticated mechanism for reconciling patent rights with public health imperatives. The 2017 amendments marked a paradigm shift, replacing fragmented summary proceedings with unified, binding litigation processes that respect international norms. While challenges persist—particularly in biologics regulation and CSP implementation—the system’s emphasis on procedural fairness and efficiency underscores Canada’s commitment to fostering both innovation and competition. Future reforms must address gaps in biologics coverage and streamline administrative processes to maintain Canada’s position as a global leader in pharmaceutical policy.

“The 2017 amendments to the PMNOC Regulations represent a watershed moment, aligning Canada’s patent linkage system with global best practices while preserving its unique balance between innovation and access.” [5][7]

References

- https://www.americanconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Smart-Biggars-Chart-PharmaBiotech.pdf

- https://www.americanconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Smart-Biggar-Article.pdf

- https://policyoptions.irpp.org/fr/magazines/the-liberal-renewal/improving-canadas-drug-patent-protection-good-for-canada-good-for-trade/

- https://www.blg.com/en/insights/2021/12/regulatory-context-for-patented-pharmaceuticals-and-biotechnology-drugs-in-canada

- https://www.osler.com/en/insights/updates/the-first-steps-taken-at-the-canadian-pharmaceutical-patent-dance/

- https://canadagazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2021/2021-04-24/html/reg2-eng.html

- https://cassels.com/insights/major-changes-to-canadas-intellectual-property-and-patent-landscape-with-the-implementation-of-ceta/

- https://www.smartbiggar.ca/patent-linkage-and-term-extension-in-canada

- https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-linkage-resolving-infringement/

- https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/scp/en/scp_32/scp_32_f_health.pdf

- https://www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/GIPC-Linkage-Zoom-In-Report.pdf

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3073891/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4448703/