In the trillion-dollar pharmaceutical industry, a patent is more than just a legal document; it’s a fortress. It’s the moat and drawbridge that protects billions of dollars in research and development investment, secures market exclusivity for a blockbuster drug, and fuels the engine of future innovation. For the lifespan of that patent, typically 20 years from the filing date, the patent holder has the exclusive right to make, use, and sell their invention. But what happens when someone storms the castle gates, not with an army in a courtroom, but with a meticulously crafted legal challenge aimed directly at the patent’s validity? This is the world of patent opposition—a high-stakes, strategically critical process that can determine the fate of a drug, the future of a company, and the landscape of public health.

For business leaders, R&D heads, and intellectual property (IP) strategists in the pharmaceutical and biotech sectors, understanding the nuances of patent opposition isn’t just an academic exercise. It’s a fundamental component of competitive intelligence, risk management, and strategic planning. Whether you’re a market incumbent seeking to defend your crown jewel asset or a generic manufacturer looking to clear a path for market entry, mastering the art and science of patent opposition can provide a decisive competitive advantage. This is not merely a legal hurdle; it’s a strategic battlefield where fortunes are won and lost long before a single lawsuit is ever filed.

This guide will take you on a deep dive into this complex domain. We’ll dissect the mechanisms of opposition systems around the world, from the centralized battleground of the European Patent Office to the unique pre-grant system in India and the quasi-judicial proceedings in the United States. We will explore the common grounds for attack—the Achilles’ heels of a patent—and lay out the strategic playbooks for both the challenger and the defender. We’ll analyze the profound financial and market implications, learn from landmark case studies, and look ahead to the future of this ever-evolving field. So, prepare to go beyond the headlines and court rulings, and into the intricate machinery of a process that shapes the very core of the pharmaceutical industry.

The Foundation: Understanding Patent Opposition and Its Global Significance

Before we can devise strategies, we must first understand the terrain. Patent opposition is not a monolithic concept; it’s a mosaic of different legal traditions, procedures, and strategic objectives. At its heart, however, it serves a crucial purpose: to act as a quality control mechanism for the patent system itself.

What is Patent Opposition and Why Does it Matter?

At its core, patent opposition is a formal administrative procedure that allows third parties to challenge the validity of a patent, or a pending patent application, before a national or regional patent office. Unlike patent litigation, which is a judicial process conducted in a court of law and can be astronomically expensive and time-consuming, opposition is a streamlined, cost-effective, and often faster alternative.

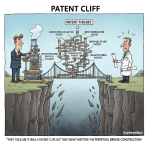

Why does it matter so much in the pharmaceutical world? The answer lies in the stakes. A single patent on an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), a specific formulation, or a method of use can be worth billions of dollars in revenue. This creates an immense incentive for competitors, particularly generic and biosimilar manufacturers, to find ways to invalidate or narrow the scope of that patent to allow for earlier market entry.

Furthermore, patent examiners, despite their expertise, are not infallible. They work under immense time pressure and with the information available to them at the time of examination. It’s entirely possible for a crucial piece of “prior art”—evidence that the invention was not new or inventive when the patent was filed—to be missed. Opposition proceedings provide a vital second look, allowing the public, and particularly knowledgeable competitors, to bring new evidence and arguments to the forefront. For society, this process helps ensure that only truly deserving inventions are granted monopoly rights, striking a delicate balance between incentivizing innovation and promoting access to affordable medicines.

The Great Divide: Pre-Grant vs. Post-Grant Opposition

Globally, opposition systems can be broadly categorized into two main types: pre-grant and post-grant. The timing of the challenge—before or after the patent is officially granted—has profound strategic implications.

The Pre-Grant Model: Early Intervention

In a pre-grant opposition system, third parties can file a challenge after a patent application has been published but before it is officially granted. This model is designed for early-stage intervention, allowing the patent office to consider potential invalidity arguments as part of the examination process itself.

The most prominent example of a robust pre-grant system is found in India. Under the Indian Patents Act, any person can file a pre-grant opposition on specified grounds after the application is published and before the grant of a patent. This is a powerful tool, particularly for generic manufacturers and public health groups, as it can prevent a weak or “undeserving” patent from ever being issued in the first place. This avoids the need for later, more complex revocation proceedings. The strategic advantage here is clear: it’s often easier to stop a patent from being granted than to overturn a granted one, which enjoys a presumption of validity.

The Post-Grant Model: Challenging an Issued Patent

In contrast, a post-grant opposition system allows challenges only after a patent has been formally granted. This is the more common model globally. A specific, time-limited window is typically opened immediately following the grant, during which any third party can file an opposition.

The European Patent Office (EPO) operates the quintessential post-grant system. Within nine months of the date a European patent is granted, any person can file a notice of opposition. This kicks off a centralized, quasi-judicial proceeding before the EPO’s Opposition Division. The outcome—whether the patent is maintained as granted, amended, or revoked entirely—applies across all the designated member states of the European Patent Convention (EPC). This centralized nature is its greatest strength. Instead of fighting costly parallel litigation battles in multiple European countries, a challenger can seek to invalidate the patent in a single, unified procedure. This efficiency and broad impact make the EPO opposition system one of the most strategically important post-grant procedures in the world.

Unpacking the Terminology: Opposition vs. Invalidation vs. Revocation

While often used interchangeably in conversation, these terms have distinct legal meanings.

- Opposition: This refers specifically to the administrative procedure before a patent office (either pre- or post-grant) as described above. It’s a challenge adjudicated by patent examiners or specialized boards within the patent office structure.

- Invalidation/Revocation: These terms typically refer to a judicial process where a party files a lawsuit in a court of law seeking to have a granted patent declared invalid or revoked. This is full-blown litigation, often running parallel to or following an opposition proceeding. For instance, even if a European patent survives an EPO opposition, it can still be challenged on validity grounds in the national courts of individual EPC member states.

- Re-examination/Review Proceedings (U.S.): The United States has a unique system that doesn’t fit neatly into the traditional opposition model. Instead, it offers several quasi-judicial trial proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), an administrative body within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The most prominent of these are Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR). These are functionally similar to post-grant oppositions but have their own distinct rules, timelines, and strategic considerations.

Understanding these distinctions is crucial for developing a coherent global IP strategy. A company might choose to file an EPO opposition to challenge a competitor’s European patent while simultaneously preparing for district court litigation in the U.S. involving the corresponding U.S. patent.

A Tour of the Global Battlegrounds: Key Jurisdictions and Their Nuances

A successful global patent strategy requires more than a general understanding of opposition; it demands a deep appreciation for the unique rules and strategic landscapes of key pharmaceutical markets. What works in Munich may fail in Washington D.C., and a winning argument in Delhi might be irrelevant in Beijing.

The European Patent Office (EPO): The Centralized Colosseum

The EPO’s post-grant opposition system is arguably the most consequential in the world for the pharmaceutical industry. Its centralized nature makes it a high-stakes, all-or-nothing proposition. A single successful opposition can wipe out patent protection across up to 44 countries, including major markets like Germany, France, the UK, and Italy.

The Process:

- The Window: An opposition must be filed within a strict nine-month period following the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent. Miss this deadline, and the opportunity for a centralized challenge is lost forever (though national invalidation actions remain possible).

- The Grounds: The opposition must be based on specific grounds laid out in the European Patent Convention, primarily lack of novelty, lack of inventive step, insufficient disclosure, or the patent claiming subject matter that extends beyond the content of the application as filed.

- The Written Procedure: The process begins with a written phase. The opponent files a detailed notice of opposition, laying out their arguments and evidence. The patentee then files a response, defending the patent and often submitting amended sets of claims in “auxiliary requests” as fallback positions.

- The Oral Proceedings: In most contested cases, the procedure culminates in oral proceedings before a three-member Opposition Division in Munich, The Hague, or Berlin. This is a formal hearing where both sides present their arguments in person. It is a highly technical, focused, and intense event, often deciding the fate of the patent in a single day.

- The Appeal: The decision of the Opposition Division can be appealed by either party to the EPO’s Boards of Appeal, adding another layer to the process.

Strategic Considerations:

- For Challengers: The EPO offers incredible leverage. A relatively low-cost opposition (compared to multi-country litigation) can neutralize a competitor’s entire European patent portfolio in one fell swoop. The key is a meticulously prepared case, often built on prior art that the original examiner may have overlooked.

- For Patentees: Defending an EPO opposition requires skill and foresight. The most effective defense begins long before the opposition is even filed, with the drafting of a robust patent application that anticipates potential challenges. During the proceedings, the strategic use of auxiliary requests is paramount. By offering progressively narrower sets of claims, the patentee creates multiple fallback positions, increasing the chances that at least some form of protection will survive even if the main claims are found invalid.

Industry Insight:

“The EPO opposition system is a cornerstone of the European patent landscape. Statistics consistently show that a significant percentage of opposed patents are either revoked or forced into amendment. In 2023, for instance, of the opposition cases decided at first instance, 31% of patents were revoked, and 37% were maintained in an amended form. Only 32% were maintained as granted. This demonstrates that opposition is not a long shot; it is a very real threat to patentees and a powerful tool for challengers.” [1]

The United States: A Tale of IPR, PGR, and Litigation

The U.S. system is a different beast altogether. Following the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2011, the U.S. introduced powerful new administrative trial proceedings conducted by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). These were designed to be faster, cheaper, and more efficient alternatives to district court litigation for challenging patent validity.

Key PTAB Proceedings:

- Post-Grant Review (PGR): This is the broader of the two main proceedings. A PGR petition can be filed within nine months of a patent’s grant and can challenge the patent on any ground of invalidity, including novelty, obviousness, written description, enablement, and indefiniteness. This makes it procedurally similar to an EPO opposition but with a very different legal framework.

- Inter Partes Review (IPR): This is the more commonly used proceeding. An IPR can be filed after the nine-month PGR window has closed (or if the patent was granted before the AIA). However, its scope is narrower: an IPR can only challenge patent claims based on lack of novelty or obviousness, and only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.

The Process:

- The Petition: The challenger (Petitioner) files a detailed petition with the PTAB, laying out the grounds for invalidity with supporting evidence and expert declarations.

- Institution Decision: The PTAB reviews the petition and the patent owner’s preliminary response. It will only “institute” a trial if it determines there is a “reasonable likelihood” (for IPR) or it is “more likely than not” (for PGR) that the petitioner will prevail with respect to at least one of the challenged claims. This is a crucial gatekeeping step.

- The Trial: If instituted, the trial proceeds with discovery (more limited than in district court), briefing, and an oral hearing before a panel of three administrative patent judges. A final written decision is typically issued within one year of institution.

Strategic Considerations:

- “Death Squad” Reputation: In its early years, the PTAB gained a reputation as a “patent death squad” due to the high rate at which it invalidated challenged claims, making it an extremely attractive venue for generic and biosimilar companies. While institution rates and invalidation rates have moderated over time, it remains a formidable challenge for patent owners.

- Parallel Litigation: PTAB proceedings often run parallel to district court litigation under the Hatch-Waxman Act. A common strategy for a generic filer is to challenge a brand’s patents in an IPR while also fighting the infringement case in court. A successful IPR can end the district court case early, saving millions in legal fees.

- Estoppel: There’s a significant catch for the challenger. If an IPR results in a final written decision, the petitioner is “estopped” (prevented) from raising any invalidity ground in a future court case that they “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the IPR. This means you get one good shot at the PTAB, so you have to make it count.

India: The Pre-Grant Vanguard and Section 3(d)

India’s patent system is unique and has been shaped by a desire to balance the interests of innovators with the pressing public health needs of a developing nation. Its pre-grant opposition system is a central feature of this landscape.

Pre-Grant Opposition (Section 25(1)):

As mentioned, any person can file an opposition after publication and before grant. It’s an ex parte proceeding initially (between the opponent and the Controller of Patents), but can become an inter partes hearing if the Controller finds merit in the opposition. This is an incredibly effective and low-cost tool for weeding out weak patents.

Post-Grant Opposition (Section 25(2)):

India also has a post-grant opposition system. Any “person interested” (a term that implies a commercial or other direct interest) can file an opposition within one year of the patent’s grant. This is a full-fledged inter partes proceeding before an Opposition Board.

The Specter of Section 3(d):

The most famous—and controversial—aspect of Indian patent law is Section 3(d) of the Patents Act. This provision states that “the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance” is not considered an invention. This is aimed directly at preventing “evergreening,” the practice of obtaining new patents for minor modifications of existing drugs (like new salts, esters, or polymorphs) to extend monopoly protection.

The landmark case involving Novartis’s cancer drug Glivec (Imatinib) famously hinged on this provision. The Indian Supreme Court in 2013 denied a patent for the beta-crystalline form of imatinib mesylate, ruling that Novartis had not shown it offered enhanced therapeutic efficacy over the original substance. This decision cemented Section 3(d) as a powerful ground for opposition in India, forcing innovators to demonstrate genuine therapeutic improvement to secure patents for second-generation drugs. For any company filing in India, addressing potential Section 3(d) objections proactively is absolutely critical.

Other Key Markets: A Snapshot

- China: China’s system is a post-grant model. Any entity or individual can request invalidation of a granted patent at any time during its term. The proceedings are handled by the Patent Re-examination and Invalidation Department (PRID) of the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). Given China’s growing importance as a pharmaceutical market and R&D hub, understanding this invalidation process is becoming increasingly vital.

- Brazil: Brazil features a unique system where the national health regulatory agency, ANVISA, conducts a prior review of pharmaceutical patent applications for public health concerns before the Brazilian Patent and Trademark Office (INPI) will grant the patent. While not a traditional opposition, third parties can submit “subsidies” or observations during the examination phase to influence both ANVISA’s and INPI’s decisions.

- Japan: Japan has a post-grant opposition system that was re-introduced in 2015. A challenge can be filed within six months of the patent grant. It is handled by a panel of appeal judges at the Japan Patent Office (JPO) and is generally considered a faster and less expensive alternative to a full invalidation trial.

Grounds for Opposition: The Achilles’ Heel of a Patent

A patent opposition is not a vague complaint; it’s a targeted legal assault based on specific, prescribed grounds. Understanding these grounds is akin to a military strategist studying the weak points in a fortress wall. A successful challenge requires identifying the right vulnerability and exploiting it with overwhelming evidence.

Novelty: The Bedrock of Patentability

The most fundamental requirement for any invention is that it must be new. The legal test for novelty, defined under Article 54 of the EPC and 35 U.S.C. § 102 in the U.S., is absolute. An invention is not new if it was made available to the public in any form—a prior patent, a scientific journal, a conference presentation, a PhD thesis in a university library, or even a public sale—before the priority date of the patent application.

In a pharmaceutical context, a novelty attack might involve:

- Finding a “Killer” Prior Art Document: The holy grail for an opponent is finding a single document that explicitly and unambiguously discloses the claimed invention. For example, a scientific paper published before the patent’s filing date that describes the exact chemical compound being claimed would destroy its novelty.

- Challenging Priority Claims: Patentees often file a series of applications, claiming “priority” from an earlier one. An opponent can attack this chain. If the claimed invention wasn’t properly supported in the earlier priority document, that document’s filing date can’t be used. This pushes the critical date forward, making the invention vulnerable to prior art published in the interim.

Inventive Step (Non-Obviousness): The “Spark of Genius” Test

This is the most common and often most complex ground of opposition. It’s not enough for an invention to be new; it must also be non-obvious to a “person skilled in the art.” This “person” is a legal fiction—a hypothetical technical expert in the relevant field who has access to all the prior art. The question is: starting from the closest prior art, would the invention have been obvious to this skilled person?

In pharmaceuticals, this is a fertile ground for debate:

- Obvious-to-Try: A common argument is that a new compound was merely one of a number of obvious candidates to test for a known problem. For example, if a prior art document discloses a class of compounds with a certain biological activity and suggests modifying them in a particular way, an opponent might argue that creating the specific claimed compound was simply an “obvious-to-try” experiment with a reasonable expectation of success.

- Structural Obviousness: If a new compound is structurally very similar to a known compound with a known utility (e.g., a “lead compound”), it may be considered prima facie obvious. The patentee must then provide evidence of unexpected results—such as surprisingly higher potency, lower toxicity, or a completely new therapeutic effect—to rebut this presumption.

- Polymorphs and New Formulations: Patents on new crystalline forms (polymorphs) or new formulations of known drugs are frequently challenged on inventive step. The opponent will argue that routine screening for polymorphs or developing a standard formulation (like a tablet or injectable solution) is a standard, non-inventive practice for the skilled formulator. The patentee must demonstrate that the specific polymorph or formulation provides an unexpected technical advantage (e.g., significantly better stability or bioavailability).

The assessment of inventive step is highly fact-dependent and often involves weighing competing technical arguments and expert opinions.

Sufficiency of Disclosure (Enablement): The “Recipe” Requirement

A patent is a bargain with the public: in exchange for a temporary monopoly, the inventor must disclose the invention in enough detail for a skilled person to be able to carry it out without “undue burden.” This is the sufficiency or enablement requirement (Article 83 EPC, 35 U.S.C. § 112).

An opposition on this ground argues that the patent is just a “paper patent” that doesn’t actually teach how to make or use the invention.

- Reproducibility: The opponent may argue that the experiments described in the patent are not reproducible or that the instructions are too vague. For example, if a patent claims a method for producing a recombinant protein but fails to provide the specific cell line or vector used, an opponent could argue undue burden.

- Breadth of Claim: This is a powerful attack, especially against broad “genus” claims in chemistry and biotech. If a patent claims a vast family of chemical compounds but only provides a few examples of how to make and test them, an opponent can argue that the disclosure doesn’t enable a skilled person to make and use the entire scope of the claim. The patentee hasn’t provided a principle of general application, just a few specific data points. The claim is broader than the technical contribution.

Added Matter and Unallowable Amendments

During the back-and-forth of patent examination, applicants often amend their claims to overcome objections from the examiner. However, there’s a strict rule: you cannot add subject matter that was not disclosed in the application as originally filed (Article 123(2) EPC). This is to prevent applicants from unfairly broadening their invention or adding a feature they only thought of later.

Opponents meticulously compare the granted claims to the original application. Even seemingly minor changes can be fatal. For example, if the original application disclosed a temperature range of “50-100°C” and a pressure range of “10-20 atm,” but the granted claim combines the lower end of the temperature range with the upper end of the pressure range to claim a process at “50°C and 20 atm,” this could be considered added matter if that specific combination was never explicitly or implicitly disclosed. This “intermediate generalization” is a classic trap for patentees and a prime target for opponents.

Specific Jurisdictional Grounds: The Case of Section 3(d)

As discussed with India, some jurisdictions have unique grounds for opposition rooted in public policy. Section 3(d) is the most prominent example in the pharmaceutical space, but other countries have exclusions for methods of medical treatment, diagnostic methods, or inventions contrary to “ordre public” or morality. A challenger must be aware of these specific local provisions, as they can provide a unique and powerful angle of attack that wouldn’t be available elsewhere.

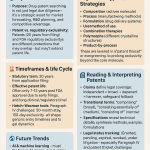

The Opposition Playbook: A Strategic Guide for Challengers

For generic manufacturers, biosimilar developers, and even public interest groups, patent opposition is a primary strategic weapon. It’s not just about filing a legal document; it’s a campaign that requires meticulous planning, deep technical expertise, and a killer instinct.

The Challenger’s Mindset: From Risk to Opportunity

The first step is a mental shift. Viewing a brand-name drug’s patent portfolio not as an impenetrable wall, but as a series of puzzles to be solved. Each patent is a potential point of failure. The goal is to identify the weakest link and concentrate your resources there.

This requires a proactive, intelligence-driven approach. Who are the key players in this space?

- Generic/Biosimilar Manufacturers: The most common challengers. Their entire business model depends on entering the market as soon as patent protection expires or can be invalidated. For them, a successful opposition is a direct path to revenue.

- Other Innovator Companies: Sometimes, the challenger is another research-based pharmaceutical company. They may want to clear the path for their own competing product (“freedom to operate”) or see a competitor’s patent as a roadblock to their R&D program.

- Patient Advocacy and Public Health Groups: Particularly in jurisdictions like India and Brazil, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and patient groups play a crucial role in challenging patents they believe are unwarranted and hinder access to affordable medicines. Groups like Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) have been actively involved in key opposition cases.

- “Straw Man” Opponents: In some cases, a company may not want to reveal its identity as the challenger. They might use a third party, or “straw man” (where legally permissible), to file the opposition on their behalf to avoid tipping their hand about their commercial intentions.

Building the Case: The Art and Science of Prior Art Searching

The entire opposition case rests on the quality of the evidence, and in most cases, that evidence is prior art. A comprehensive prior art search is the single most critical investment a challenger can make. This goes far beyond a simple keyword search.

Leveraging Databases and Specialized Services

The search begins with patent databases (like those from the EPO, USPTO, WIPO, and national offices) and scientific literature databases (like PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science). However, to gain a real edge, challengers often turn to specialized services.

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch, for example, provide a crucial strategic advantage. They don’t just list patents; they offer curated intelligence specifically for the pharmaceutical industry. A challenger can use such a service to monitor a competitor’s portfolio, get alerts on newly granted patents, and access integrated data on patent expiry, litigation, and regulatory approvals. Critically, these platforms often provide detailed patent family information and links to related documents, which can be instrumental in piecing together the history of an invention and uncovering vulnerabilities, such as weaknesses in a priority claim. By streamlining the initial intelligence-gathering phase, services like DrugPatentWatch allow the challenger’s R&D and legal teams to focus their efforts on the most promising lines of attack.

Going Beyond the Obvious: The Deep Dive

A world-class prior art search digs deeper:

- Non-Patent Literature: This is where many gems are found. PhD theses, conference posters and abstracts, industry presentations, and even old product brochures can constitute prior art. The key is proving they were publicly available before the critical date.

- Foreign Language Searches: The invention may have been disclosed in a Japanese scientific paper or a German patent application that was missed by the original English-speaking examiner. Professional search firms with multilingual capabilities are essential.

- Clinical Trial Registries: Databases like ClinicalTrials.gov contain detailed protocols for clinical studies. These protocols, if published before the patent’s priority date, can sometimes disclose key aspects of a new formulation or method of use, serving as powerful prior art.

- Inventor-Centric Searches: Research the inventors themselves. What did they publish before filing the patent? What presentations did they give? Sometimes an inventor’s own earlier work can be used to challenge their later patent.

Crafting the Opposition Statement: A Masterclass in Persuasion

Once the evidence is gathered, it must be woven into a compelling legal and technical narrative. The notice of opposition is not just a data dump; it’s a persuasive document designed to convince a panel of expert judges.

- Structure the Attack: Start with your strongest argument first. Often, this is a “killer” novelty objection if you have one. If the case is based on inventive step, structure it logically using the “problem-solution” approach common at the EPO. Clearly identify the closest prior art, state the objective technical problem, and then meticulously explain why the claimed solution would have been obvious to the skilled person.

- Clarity and Precision: Avoid hyperbole. The arguments should be clear, concise, and directly linked to the evidence. Use claim charts to map the elements of the patent’s claims directly onto the disclosures in the prior art documents.

- The Role of Expert Witnesses: A declaration or report from a respected expert in the field can be incredibly powerful. The expert can explain the technical context, interpret the prior art from the perspective of the “person skilled in the art,” and attest that the invention was obvious or that the patent’s experiments are not reproducible. Choosing a credible, articulate expert is a critical strategic decision. As Dr. Annabelle Eckhardt, a seasoned European Patent Attorney, states, “An opposition is won or lost on the details. A well-reasoned argument, supported by an unimpeachable expert and irrefutable prior art, is almost impossible for a patentee to overcome. The goal is to leave the Opposition Division with no other logical choice but to revoke.”

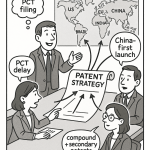

Timing and Global Coordination

Timing is everything. Missing the nine-month opposition window at the EPO or PGR window at the USPTO is a fatal error. A global challenger must have a robust patent monitoring system to track grant dates in all key jurisdictions.

Furthermore, a coordinated strategy is essential. Arguments used in an EPO opposition can be repurposed for a U.S. IPR or a Japanese opposition. Evidence uncovered for one proceeding can be deployed in another. However, it’s crucial to be aware of the different legal standards. An argument that works for inventive step under the EPO’s problem-solution approach needs to be reframed to fit the obviousness framework in the U.S. (the Graham factors).

Defending Your Fortress: A Strategic Guide for Patent Holders

For the innovator company, an opposition is a direct threat to a core asset. A robust defense is not just reactive; it’s a proactive strategy that begins years before any challenge is filed. The goal is to make your patent fortress as unassailable as possible.

Proactive Defense: Building an Opposition-Proof Patent

The best defense is a good offense, and that offense starts with drafting the patent application itself.

- The “Landmine” Approach to Disclosure: Draft the application with future opposition in mind. This means including a wealth of data and fallback positions. Disclose and claim not just the preferred embodiment, but also numerous alternatives. For a chemical compound, this means providing data on its stability, toxicity, potency, and formulation performance. For a formulation, it means including data that supports claims of unexpected advantages over the prior art. Each data point is a potential “landmine” that can be used to support an amended claim during an opposition.

- Comprehensive Internal Prior Art Searching: Before you even file, conduct the same kind of exhaustive prior art search a future opponent would. It’s far better to know about problematic prior art yourself and address it head-on in the application than to be surprised by it in an opposition years later. You can frame your invention’s advantages specifically in contrast to this known art.

- Drafting Claims with Fallbacks in Mind: Don’t just draft one broad, independent claim. Draft a series of dependent claims of progressively narrower scope. These dependent claims can form the basis of auxiliary requests in an EPO opposition. Think of it like building concentric circles of defense around your core invention. If the outer wall is breached, you can fall back to the next, and the next.

The Response: Countering the Attack with Precision and Flexibility

When the notice of opposition lands on your desk, the reactive phase begins. It requires a cool head and a methodical approach.

- Deconstruct the Challenger’s Case: Analyze every argument and every piece of evidence submitted by the opponent. Look for weaknesses. Is their interpretation of the prior art correct? Is their expert witness truly an expert in the specific sub-field? Have they misapplied the legal standard?

- The Power of Auxiliary Requests: In the EPO, the strategic filing of auxiliary requests is the cornerstone of a successful defense. The main request is to maintain the patent as granted. The first auxiliary request might narrow the main claim slightly to overcome the opponent’s primary objection. The second might narrow it further, and so on. This creates a cascading series of fallback positions. The goal is to present the Opposition Division with a menu of options, making it more likely they will find at least one of them allowable. As a leading patent attorney noted, “Going into an EPO oral proceeding with only one request is like going into battle with only one bullet. You must give the Division multiple, well-supported positions to consider. The art is in crafting requests that are narrow enough to be patentable but still broad enough to be commercially valuable.”

- Submitting New Evidence: A patentee is not limited to the data in the original patent. If the opponent raises a new objection, the patentee can often submit new experimental data to counter it. For example, if an opponent argues that your compound is obvious over a prior art compound, you can conduct head-to-head comparison tests and submit data showing your compound has an unexpected property (e.g., it’s 100 times more potent). This post-filed data can be decisive in proving an inventive step.

The Oral Proceedings: High-Stakes Legal Theater

The oral proceedings are the climax of the opposition process, particularly at the EPO. This is not a time for bluster; it’s a time for calm, credible, and flexible advocacy.

- Preparation is Key: The legal and technical team must know the case inside and out—every claim, every prior art document, every potential argument. Mock hearings and rigorous preparation sessions are essential.

- Reading the Room: The patent attorney must be able to “read the room”—to understand the Opposition Division’s concerns as they emerge during the hearing and to adapt the strategy in real-time. This might mean abandoning a weaker argument to focus on a stronger one or even amending the claims on the spot in response to a question from the board.

- The Team: The team at the hearing is crucial. It typically includes the patent attorney, a technical expert from the company (who can answer detailed scientific questions), and sometimes an external academic expert. Their ability to work together seamlessly under pressure is vital.

The Strategic & Financial Implications of Patent Opposition

The impact of patent opposition extends far beyond the legal department. The outcome of these proceedings can send ripples through a company’s financial statements, market strategy, and M&A activity.

The Cost-Benefit Analysis: Opposition vs. Litigation

One of the primary drivers for using opposition systems is cost. While not cheap, an opposition is significantly less expensive than full-blown court litigation.

- EPO Opposition: A moderately complex opposition can cost anywhere from €50,000 to €200,000, including attorney fees, search costs, and official fees.

- U.S. IPR/PGR: A PTAB trial is more expensive, often ranging from $300,000 to over $700,000 through to a final decision.

- U.S. District Court Litigation: In contrast, a Hatch-Waxman patent litigation case can easily cost $5 million to $15 million or more.

The math is compelling. For a challenger, the potential to invalidate a multi-billion dollar drug’s patent for a few hundred thousand dollars in an IPR or EPO opposition represents an incredible return on investment. For a patentee, even a successful defense is costly, but it’s a necessary cost of protecting a revenue-generating asset.

Impact on Market Entry and Generic Competition

The most direct impact is on the timing of generic or biosimilar market entry. A successful opposition can shave years off a patent’s life, opening the door for competition much earlier than anticipated. This can dramatically alter the revenue forecasts for the innovator drug.

For example, if a generic company successfully revokes a key formulation patent through an EPO opposition, it may be able to launch its generic version several years earlier across Europe, capturing significant market share and causing a steep drop in the brand’s sales. The mere filing of a credible opposition or PTAB challenge can create uncertainty, which itself has strategic value.

Investor Confidence and Stock Market Reactions

The financial markets watch these proceedings closely. The institution of an IPR against a company’s key patent can cause an immediate drop in its stock price. Conversely, a final decision upholding the patent can lead to a rally.

This is because investors understand that patent protection is the foundation of a pharmaceutical company’s value. Any threat to that foundation is a threat to future revenue streams. Companies must be prepared to communicate clearly with investors about the risks and merits of ongoing opposition proceedings to manage market expectations.

Licensing and M&A: Due Diligence in a Contested World

Patent oppositions are a critical factor in due diligence for licensing deals and mergers and acquisitions.

- For the Acquirer/Licensee: Before acquiring a company or licensing a drug, a thorough analysis of its patent portfolio must include an assessment of its vulnerability to opposition. Are the key patents strongly drafted? Is there threatening prior art? Are there any ongoing oppositions? The potential for a key patent to be invalidated in an opposition proceeding represents a major risk that could devalue the entire deal or even scuttle it completely.

- For the Seller/Licensor: A portfolio of “battle-tested” patents that have survived opposition challenges can be a significant asset. It demonstrates their strength and resilience, commanding a higher valuation in a deal. Proactively defending patents and winning oppositions can be seen as a way of de-risking the asset for potential partners or acquirers.

Case Studies: Lessons from Landmark Opposition Battles

Theory is one thing; reality is another. Examining real-world cases reveals how these strategies and principles play out in practice.

Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi): A Global Fight for Access

Gilead’s hepatitis C drug, sofosbuvir (brand name Sovaldi), was a revolutionary treatment but came with a list price of $84,000 for a 12-week course in the U.S. This high price spurred a wave of patent oppositions around the world, led by both generic companies and public health organizations.

- In Europe: The EPO granted a patent on the base compound of sofosbuvir. This was immediately met with a flurry of oppositions from at least a dozen parties. The opponents argued, among other things, that the invention lacked an inventive step. In 2018, the EPO’s Opposition Division initially revoked the patent, a stunning blow to Gilead. However, Gilead appealed, and the EPO’s Board of Appeal later overturned the revocation and maintained the patent in an amended, narrower form.

- In India: A pre-grant opposition was filed, but the Indian Patent Office ultimately granted the patent. This decision was then challenged in court.

- Lessons Learned: The Sovaldi case illustrates the power of coordinated, multi-jurisdictional opposition campaigns. Even though Gilead ultimately preserved its core patent in Europe (in amended form), the oppositions created significant legal costs, uncertainty, and public pressure. It showed that even for a groundbreaking drug, patent protection is never guaranteed and will be fiercely contested.

Glivec (Imatinib): The Indian Supreme Court’s Defining Moment

As mentioned earlier, the 2013 decision by the Indian Supreme Court to deny a patent to Novartis for the beta-crystalline form of imatinib mesylate (Glivec) is perhaps the most famous patent opposition-related case in the world.

- The Argument: The case did not hinge on novelty or traditional inventive step. It turned entirely on Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act. Novartis had a patent on the original imatinib substance but sought a new patent for a specific salt form (mesylate) in a specific crystal structure (beta-crystalline), arguing it had improved properties like better flow and lower hygroscopicity.

- The Ruling: The Supreme Court ruled that these properties did not translate to an “enhancement of the known efficacy.” They defined “efficacy” in a therapeutic sense, meaning the drug had to work better as a medicine, not just be easier to manufacture. Since Novartis couldn’t prove the beta-crystalline form was more effective at treating cancer than the original substance, the patent was denied.

- Lessons Learned: The Glivec case sent a clear message to the global pharmaceutical industry: to obtain patents in India for modifications of known drugs, you must demonstrate a tangible therapeutic benefit. It cemented the power of Section 3(d) and has guided opposition strategy in India ever since. It highlights how specific national laws can create unique vulnerabilities and opportunities not present in other jurisdictions.

Humira (Adalimumab): A Web of Patents and Opposition

AbbVie’s Humira was the world’s best-selling drug for years, treating a range of autoimmune diseases. AbbVie constructed a formidable “patent thicket”—a dense web of over 100 patents covering the drug’s formulation, manufacturing process, and methods of use—to delay biosimilar competition for as long as possible.

- The European Strategy: In Europe, biosimilar manufacturers like Amgen, Samsung Bioepis, and Sandoz did not just wait for the main compound patent to expire. They proactively challenged AbbVie’s secondary patents through the EPO opposition system. They filed numerous oppositions against patents covering specific formulations and indications.

- The Outcome: This strategy was highly effective. The challengers successfully invalidated or forced the narrowing of several key secondary patents. While AbbVie’s primary patent remained, clearing away the secondary patents was crucial for the biosimilars to be able to launch. The pressure from these ongoing oppositions was a major factor that eventually led AbbVie to enter into settlement agreements with the biosimilar companies, allowing them to launch in Europe in 2018, years before they could launch in the U.S.

- Lessons Learned: The Humira case is a masterclass in how opposition can be used to dismantle a “patent thicket.” It shows that challengers don’t always need to attack the main compound patent. A strategic campaign against weaker, secondary patents can be just as effective in clearing a path to market. It demonstrates that opposition is a key tool in the fight against evergreening strategies.

The Future of Patent Opposition in Pharma

The landscape of patent opposition is not static. It is constantly evolving under the influence of new technologies, legal reforms, and shifting societal expectations.

The Rise of AI in Prior Art Searching and Analysis

Artificial intelligence is poised to revolutionize the opposition process. AI-powered search algorithms can sift through millions of patent and non-patent documents in minutes, uncovering connections and prior art that would be impossible for a human researcher to find. These tools can analyze the semantic meaning of text, not just keywords, leading to more comprehensive and relevant search results. For both challengers and defenders, leveraging AI for prior art searching will soon move from a competitive advantage to a standard operating procedure.

Harmonization Efforts and Global Trends

While significant differences remain between jurisdictions, there is a slow but steady trend towards harmonization. Patent offices around the world share information and work products through initiatives like the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH). The success and efficiency of centralized systems like the EPO’s opposition procedure and the U.S. PTAB may inspire other countries to adopt similar models. We may see the emergence of more streamlined, cost-effective administrative routes for challenging patents globally.

The Evolving Role of Public Interest and Patient Groups

The “third party” in opposition proceedings is increasingly a member of the public. Spurred by successes in cases like Glivec and the global fight over HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C drugs, patient and consumer advocacy groups are becoming more sophisticated and well-funded. They are using opposition proceedings as a tool of public policy to challenge patents they view as barriers to access to medicine. This trend is likely to grow, adding another layer of complexity and scrutiny for pharmaceutical patentees, particularly for drugs that treat major public health crises or have very high prices.

Conclusion: From Battlefield to Strategic Asset

Patent opposition is far more than a dry legal procedure. It is a dynamic and strategically vital arena where the future of pharmaceutical products is shaped. For too long, it has been viewed through a narrow lens—a nuisance for the patentee, a lottery ticket for the challenger. But this perspective is dangerously incomplete.

For the modern pharmaceutical enterprise, understanding and mastering patent opposition is a core competency. It is an indispensable tool for competitive intelligence, allowing you to probe the weaknesses of your rivals. It is a fundamental component of risk management, forcing you to build stronger, more resilient patent portfolios for your own innovations. It is a critical factor in business development, shaping the valuation and risk profile of every licensing deal and acquisition.

Viewing opposition as a mere legal battle is to miss the point. It is a strategic asset. For the challenger, it is the lever that can open a locked market. For the patent holder, the process of successfully defending a patent forges it into a stronger, more valuable, and de-risked asset. The companies that will thrive in the coming decade are those that move beyond a reactive, defensive crouch and learn to navigate this complex landscape with foresight, agility, and strategic intent. They will be the ones who understand that in the high-stakes world of drug patenting, the best way to win the war is to master the art of the opposition.

Key Takeaways

- Opposition is a Strategic Tool, Not Just a Legal Hurdle: Whether you are an innovator or a generic manufacturer, patent opposition is a critical administrative process that can determine market exclusivity, shape competitive landscapes, and significantly impact a drug’s lifecycle revenue. It is often faster and more cost-effective than court litigation.

- Global Systems Vary Significantly: A “one-size-fits-all” approach is doomed to fail. Strategies must be tailored to the specific rules of key jurisdictions, such as the post-grant opposition system at the EPO, the pre-grant system and Section 3(d) in India, and the IPR/PGR proceedings at the U.S. PTAB.

- Grounds for Opposition are the Weak Points: The most common challenges are based on lack of novelty, lack of inventive step (obviousness), and insufficient disclosure. A successful opposition requires identifying the patent’s weakest point and attacking it with robust evidence, primarily prior art.

- A Challenger’s Success Depends on Research: A meticulously planned and executed prior art search is the foundation of any strong opposition. This involves leveraging specialized databases (like DrugPatentWatch), non-patent literature, and expert analysis to uncover evidence missed during the initial examination.

- A Patentee’s Best Defense is Proactive: The strongest defense against opposition begins with drafting a high-quality, “opposition-proof” patent application. This includes conducting thorough internal prior art searches and including extensive data and fallback positions (e.g., dependent claims, alternative embodiments) that can be used to support amended claims during a challenge.

- Opposition has Major Financial and M&A Implications: The outcome of opposition proceedings directly affects stock prices, investor confidence, and the valuation of companies and assets in licensing and M&A deals. A “battle-tested” patent that has survived opposition is a significantly more valuable asset.

- The Landscape is Evolving: Future trends, including the use of AI in prior art searching, global harmonization efforts, and the increasing role of public interest groups, will continue to shape the strategies and outcomes of patent oppositions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is it better to file an opposition anonymously or in our company’s name?

This is a critical strategic decision with no single right answer. Filing in your company’s name signals your serious intent and interest in the market, which can add psychological pressure on the patentee. However, it also reveals your hand, alerting a competitor to your plans. Filing anonymously (or via a “straw man,” where permitted) can conceal your strategy, preventing the patentee from knowing who their future market competitor might be. The downside is that it can sometimes be perceived as less serious by patent offices, and in some proceedings (like a U.S. IPR), the real-party-in-interest must be disclosed, making true anonymity difficult. The choice depends on your specific goals, the jurisdiction, and your tolerance for revealing your commercial strategy.

2. We have a patent that is being opposed at the EPO. Should we also expect a challenge in the U.S. via an IPR?

You should absolutely prepare for that possibility. It is a very common global strategy for challengers to attack a valuable patent on multiple fronts simultaneously. While the legal standards differ (the EPO’s “problem-solution approach” for inventive step vs. the U.S. “Graham factors” for obviousness), the underlying prior art is often the same. A challenger will leverage their research and arguments across jurisdictions. Therefore, if you face a serious EPO opposition, you should immediately conduct a vulnerability assessment of the corresponding U.S. patent and prepare a potential defense strategy for an IPR, paying close attention to the slightly different legal requirements and procedural timelines.

3. Our company is developing a biosimilar. The innovator’s main compound patent is expiring, but they have a “thicket” of secondary patents on formulations and methods of use. Is opposition the best way to deal with these?

Yes, opposition is one of the most powerful tools for clearing a path through a patent thicket. As the Humira case demonstrated, these secondary patents are often weaker and more vulnerable to challenge than the original compound patent. They may be based on routine development work and can be susceptible to inventive step/obviousness attacks. By strategically selecting the most problematic patents in the thicket and challenging them via EPO opposition or U.S. IPR, you can systematically dismantle the legal barriers to your launch. This is far more efficient and cost-effective than waiting for them all to expire or fighting dozens of infringement lawsuits in national courts.

4. What is the single biggest mistake a patentee makes when defending an opposition?

The single biggest mistake is inflexibility, particularly in EPO proceedings. Patentees can become too attached to their granted claims and refuse to consider reasonable amendments. They go into oral proceedings with only a “maintain as granted” request, viewing any amendment as a loss. This is a fatal error. The goal of a defense is to emerge with commercially viable patent protection. A slightly narrowed claim that is valid and enforceable is infinitely more valuable than a broad claim that gets revoked. A savvy patentee prepares a cascade of well-supported auxiliary requests, providing the Opposition Division with multiple opportunities to find an allowable position.

5. We are a small biotech startup with a limited budget. Is it worth the cost to proactively draft our patents to be “opposition-proof,” or should we just save our money and defend if a challenge arises?

It is almost always worth the upfront investment. While it may seem expensive to conduct exhaustive prior art searches and spend extra attorney time drafting a detailed application with numerous fallback positions, it is vastly cheaper than trying to salvage a poorly drafted patent in a high-stakes opposition years later. A strong, well-supported patent is not only more likely to survive a challenge but is also a much more attractive asset to potential investors and partners. Viewing a strong patent application as an R&D investment, rather than just a legal expense, is a hallmark of a strategically mature startup. The cost of a robust initial filing is a fraction of the value it protects and the potential cost of a lost opposition.

References

[1] European Patent Office. (2024). Annual Report 2023: Patent process and quality. Retrieved from the official EPO website’s publications section. (Note: This is a representative citation based on typical EPO reporting; specific figures for a given year should be verified from the latest official report.)

[2] Indian Patents Act, 1970, Section 3(d).

[3] Novartis AG v. Union of India & Others, (2013) 6 SCC 1.

[4] America Invents Act (AIA), Public Law 112-29, 125 Stat. 284 (2011).

[5] European Patent Convention (EPC), Article 54 (Novelty), Article 56 (Inventive Step), Article 83 (Disclosure of the invention), Article 123(2) (Amendments).

[6] 35 U.S. Code § 102 (Conditions for patentability; novelty), § 103 (Conditions for patentability; non-obvious subject matter), § 112 (Specification).

[7] IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. (2017). The Global Use of Medicine in 2022: Outlook and Implications.

[8] Cohen, J., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2017). The Humira patent thicket: The coming biosimilar competition. Journal of Law and the Biosciences, 4(3), 634–644.

[9] Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Access Campaign. Various publications and press releases related to patent oppositions on essential medicines.

[10] World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). (2023). World Intellectual Property Indicators 2023. WIPO.