In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical innovation, the standard 20-year patent term is a comforting illusion. From the moment a promising molecule is first conceived and a patent application is filed, a clock starts ticking.1 However, this is not the countdown to commercial success; it is the countdown to commercial extinction. The grueling, multi-year, and multi-billion-dollar journey through preclinical studies, clinical trials, and regulatory review by agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) consumes a vast portion of this precious 20-year term. For many blockbuster drugs, the “effective patent life”—the actual time they are on the market with patent protection—can be whittled down to a mere handful of years.

This reality creates a monumental financial challenge. With R&D costs soaring—sometimes exceeding $4.5 billion per drug—and a staggering 90% of drugs that enter clinical trials ultimately failing, the pressure to recoup investment and fund the next generation of innovation during this shortened window of market exclusivity is immense.5 When the patent cliff arrives, the impact is swift and brutal. The entry of generic competition can obliterate up to 90% of a drug’s revenue almost overnight, turning a blockbuster into a legacy product in a matter of months.5

It is within this crucible of commercial pressure and regulatory reality that the true art of intellectual property strategy is forged. Extending a product’s market exclusivity is not merely a legal exercise; it is one of the most powerful levers a pharmaceutical company can pull to maximize the value of its innovation. Mechanisms like Patent Term Extension (PTE) in the United States and Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) in Europe were created to restore some of this lost time. But the true masters of the craft know that the game doesn’t end with a single extension.

This report is your guide to the advanced strategies of the second act. We will move beyond the conventional wisdom of “one patent, one extension” and delve into the nuanced, complex, and sometimes controversial world of securing multiple layers of extended protection for a single product. We will dissect the legal frameworks of the U.S. and Europe, explore the landmark court cases that have defined the boundaries of what’s possible, and lay out actionable strategies that integrate IP, regulatory, and clinical development into a cohesive lifecycle management plan. For the strategic IP decision-maker, this is not just about understanding the law; it’s about learning how to wield it as a powerful tool for competitive advantage.

The Grand Bargain: Why Patent Term Restoration Exists

To master the art of extending patent life, one must first understand the fundamental philosophy that underpins it. Patent term restoration is not a loophole or a legislative oversight; it is a carefully constructed, deliberate compromise designed to balance two competing, yet equally vital, public interests: the need to incentivize groundbreaking medical innovation and the need to ensure broad public access to affordable medicines. This delicate equilibrium is most famously embodied in the U.S. Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.10

Before 1984, the U.S. pharmaceutical market was plagued by two significant “distortions” that hampered this balance.10 First, innovator companies were losing years of their patent term while their products languished in the FDA’s mandatory premarket review process. This erosion of effective patent life blunted the very incentive the patent system was designed to provide. Second, generic drug manufacturers were legally prohibited from even beginning the development and testing required for their own FDA approval until

after the innovator’s patent had expired. This created a de facto extension of the innovator’s monopoly, as it would take several more years for a generic to navigate the regulatory pathway and finally reach the market.

The Hatch-Waxman Act was a legislative masterstroke that sought to correct both distortions through a “grand bargain”. It offered something crucial to each side:

- For Innovators: Patent Term Extension (PTE). The Act created the modern PTE system under 35 U.S.C. § 156, allowing pharmaceutical companies to “restore” a portion of the patent term lost during the FDA’s regulatory review. This was a direct acknowledgment that the unique burdens of drug development deserved a unique form of compensation to keep the engine of innovation running.10

- For Generics: The “Safe Harbor” Provision. In what is often called the “Bolar exemption,” the Act created a “safe harbor” under 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1). This provision made it explicitly not an act of patent infringement for a generic company to use a patented invention for activities “reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the manufacture, use, or sale of drugs”. In simple terms, it gave generic companies a green light to begin their development work and prepare their Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) well before the innovator’s patent expired, ensuring they could be ready to launch on day one post-expiry.

This same fundamental logic applies in Europe, albeit through a different legal instrument. The European Union created Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) to address the same core problem: the erosion of effective patent life due to the lengthy process of obtaining regulatory marketing authorization.17 An SPC is not a direct extension of the patent itself, but a unique (

sui generis) right that comes into force the day after the basic patent expires, providing up to five additional years of protection for the specific approved product.

Understanding this foundational “grand bargain” is critical for any strategic thinking about patent term extension. The entire legal framework is a negotiated truce in the ongoing war between innovation and access. Every strategy an innovator employs to maximize their extension is, in effect, a test of the limits of this bargain. It inevitably invites scrutiny and counter-pressure from generic competitors, who will challenge these extensions in court, and from regulatory bodies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which actively monitors for practices it deems anti-competitive, such as the improper listing of patents in the FDA’s Orange Book.21 Therefore, any aggressive lifecycle management strategy must be developed with a keen awareness of this dynamic tension, incorporating a robust risk assessment of the potential for legal and regulatory pushback.

A Critical Distinction: Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) vs. Patent Term Extension (PTE)

Before we venture into the sophisticated strategies of lifecycle management, we must establish a clear and unambiguous understanding of two terms that are frequently confused, often with costly consequences: Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE). While both mechanisms can add time to the life of a U.S. patent, they originate from different statutes, serve entirely different purposes, and, most critically, have different vulnerabilities.27

Patent Term Adjustment (PTA), governed by 35 U.S.C. § 154, is an administrative remedy for delays caused by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) during the prosecution of a patent application. It was created by the American Inventors Protection Act of 1999 to ensure that inventors are not penalized for the patent office’s own inefficiencies. If the USPTO fails to meet certain statutory deadlines—such as issuing a first office action within 14 months or issuing a patent within three years of filing—the patent term is “adjusted” on a day-for-day basis to compensate for that delay. PTA can apply to any utility or plant patent, regardless of the technology.

Patent Term Extension (PTE), governed by 35 U.S.C. § 156, is the mechanism we have been discussing, born from the Hatch-Waxman Act. It compensates a patent owner for delays caused by a federal regulatory agency—most commonly the FDA—during the premarket approval process for a specific product.10 PTE is highly specific; it is available only for patents covering certain regulated products like human drugs, biologics, and medical devices.

The distinction becomes strategically vital when we consider their interaction with a common feature of pharmaceutical patent portfolios: the terminal disclaimer. Pharmaceutical companies often build “patent thickets” around a valuable drug, filing multiple patents on various aspects of the invention (e.g., the compound, a formulation, a method of use). To overcome potential “obviousness-type double patenting” (ODP) rejections from the USPTO, where two patents claim inventions that are not patentably distinct, companies file a terminal disclaimer, which contractually agrees that the later-issued patent will expire on the same day as the earlier patent.28

Here lies the crucial difference:

- PTA is vulnerable to terminal disclaimers. The Federal Circuit’s landmark decision in In re Cellect confirmed that if a patent has received PTA, a terminal disclaimer filed against an earlier-expiring patent in the same family can effectively wipe out that PTA.34 The disclaimer truncates the patent’s term

after the PTA has been added, negating the adjustment. - PTE is immune to terminal disclaimers. In stark contrast, the Federal Circuit held in cases like Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal and later affirmed in Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC that a validly obtained PTE is not affected by a terminal disclaimer.15 The statutory grant of PTE to compensate for regulatory delay is considered a distinct right that cannot be negated by the judge-made doctrine of ODP.

This legal divergence creates a clear strategic hierarchy within a patent family. A patent that is eligible for PTE is inherently more valuable and robust than one that is only eligible for PTA. When a company has multiple patents covering an approved drug and must choose only one to extend, the obvious choice might seem to be the one with the longest potential term (i.e., the one with the most PTA already accrued). However, this can be a strategic trap. It may be far wiser to select a different patent in the family for the PTE—even one with zero PTA—because the five-year PTE it receives will be a durable, defensible asset, immune to the ODP challenges that could nullify the PTA on another patent. This non-obvious choice requires looking beyond a simple calculation of days and understanding the fundamental legal character of each type of extension.

The U.S. Framework: Navigating the Hatch-Waxman Act

The United States represents the largest and most lucrative pharmaceutical market in the world, and the Hatch-Waxman Act is the foundational text governing the interplay of patents, regulatory approvals, and market exclusivity. Mastering its provisions, particularly the intricate details of 35 U.S.C. § 156, is an absolute prerequisite for any successful lifecycle management strategy. This is not a landscape for amateurs; it is a complex game with clearly defined rules, and victory goes to those who know them best.

Deep Dive into 35 U.S.C. § 156: The Rules of the Game

At its core, the PTE statute is a gatekeeping mechanism. It lays out a series of hurdles that a patent and its associated product must clear to be deemed worthy of a term extension. Let’s break down these rules piece by piece.

Eligibility: Is Your Product and Patent a Candidate?

The statute begins by laying out five core conditions that must be met for a patent to be eligible for extension. These are not suggestions; they are absolute requirements, and failure to meet any one of them is fatal to an application.13

- The patent has not expired before the PTE application is submitted.

- The patent’s term has never been previously extended under this specific statute (§ 156). A patent can only receive one PTE in its lifetime.

- A valid application is submitted by the owner of record of the patent (or its agent) in compliance with all procedural requirements.

- The product has been subject to a “regulatory review period” before its commercial marketing or use. This is the foundational requirement—the product must have gone through the FDA approval gauntlet.

- The approval is the first permitted commercial marketing or use of the product. This is arguably the most litigated and strategically critical of all the requirements.

The type of patent also matters. Eligibility is limited to patents that claim one of three things: the product itself (e.g., the active pharmaceutical ingredient), a method of using that product (e.g., treating a specific disease), or a method of manufacturing that product.36 This scope is broad enough to cover the most commercially relevant patents in a pharmaceutical portfolio. The eligible products themselves include human drugs, biologics, Class III medical devices, food and color additives, and certain veterinary products.10

The Crucial Definition of a “Product”

Of all the terms in the statute, none is more important than “product.” The entire eligibility analysis, particularly the “first permitted use” requirement, hinges on its precise legal definition. Under 35 U.S.C. § 156(f), a “product” is defined as the “active ingredient… including any salt or ester of the active ingredient”.14

This definition may seem straightforward, but it creates a critical distinction from the terminology often used by the FDA. For its own regulatory exclusivities, such as the five-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity, the FDA often focuses on the “active moiety”—the core, therapeutically active portion of a molecule, excluding any appended salts or esters. The PTE statute, however, is more literal and chemical. It looks at the entire active ingredient as it exists in the final drug product.

The landmark case of PhotoCure ASA v. Kappos (2010) drove this point home. The case involved two related compounds: aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and methyl aminolevulinate (MAL). An ester of ALA (ALA HCl) had been previously approved by the FDA. Later, PhotoCure received approval for a new drug, Metvixia, whose active ingredient was MAL HCl. The USPTO initially denied PTE for the patent covering MAL HCl, arguing that because both MAL and ALA shared the same “active moiety,” the approval of Metvixia was not the “first permitted commercial marketing” of that moiety. The Federal Circuit reversed this decision, focusing squarely on the statute’s text. The court held that the term “product” refers to the specific “active ingredient,” not the broader “active moiety.” Since MAL HCl was a chemically distinct active ingredient from the previously approved ALA HCl, its approval was the first permitted use of that specific product, making the patent eligible for PTE.14

This strict, literal interpretation of “product” has profound strategic implications. On one hand, it prevents a simple form of evergreening; a company cannot get a new PTE simply by making a new salt of an already-approved active ingredient and calling it a new product. On the other hand, it opens a sophisticated strategic door. If a company develops a genuinely new ester or salt that is chemically distinct and has never been approved before, that new entity is considered a “new product” for PTE purposes, even if it is pharmacologically related to a previously approved drug. This means its approval can serve as the basis for a brand-new PTE, providing a powerful lifecycle management tool that hinges entirely on a nuanced understanding of chemical structure and patent law.

For combination products containing two or more active ingredients, the rule is generally that PTE is available only if at least one of the active ingredients is new (i.e., has never been approved before as a salt or ester).14 A new combination of two previously approved drugs, no matter how innovative or synergistic, is typically not eligible for PTE.

Calculating the Extension: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Once a patent is deemed eligible, the length of the extension is calculated according to a specific statutory formula. The goal is to restore time lost during the regulatory review period, but with several important limitations and deductions. The basic formula is as follows 15:

PTE=21(Testing Phase)+(Approval Phase)

Let’s break down the components:

- Testing Phase: This is the period of clinical investigation. It begins on the later of the patent’s issue date or the date the Investigational New Drug (IND) application becomes effective. It ends on the date the New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) is submitted to the FDA. Critically, the innovator is only credited for one-half of this time. The legislative reasoning is that some commercially valuable research and development activities can occur during this phase.

- Approval Phase: This is the period during which the FDA is formally reviewing the marketing application. It begins on the later of the patent’s issue date or the date the NDA/BLA was submitted, and it ends on the date the application is approved. The innovator is credited for the full duration of this phase.

From this total, any time during which the applicant did not act with “due diligence” is subtracted. Finally, the entire calculation is subject to two overarching statutory caps:

- The maximum extension granted cannot exceed five years.15

- The total remaining term of the patent after the FDA approval date cannot exceed fourteen years.15

This 14-year cap is a crucial check on the system. It ensures that regardless of how long the regulatory review took, the innovator cannot have more than 14 years of effective market life remaining on that patent from the moment of approval. The final extension granted is the shortest of the calculated period, five years, or the period needed to hit the 14-year cap.

The Pediatric Exclusivity Windfall: Adding a Golden Six Months

Beyond the standard PTE mechanism lies one of the most valuable and strategically unique tools for extending market exclusivity in the United States: pediatric exclusivity. It is a powerful incentive created by Congress to address a critical public health need—the lack of properly studied and labeled medicines for children. For the savvy IP strategist, it represents a golden opportunity to add a highly valuable six-month period of protection across an entire product franchise.

What makes pediatric exclusivity so potent is its unique mechanism of action. Unlike PTE, which extends a single patent, pediatric exclusivity is a “tack-on” that attaches to and extends all existing forms of patent protection and regulatory exclusivity for a given active moiety.48 If a drug has five patents expiring on different dates and also has a period of Orphan Drug Exclusivity, obtaining pediatric exclusivity adds six months to the expiration date of

all five patents and to the end of the orphan exclusivity period.

The process for obtaining this valuable extension is not tied to commercial success but to regulatory cooperation 49:

- The FDA Issues a Written Request: The process begins with the FDA formally requesting that the drug’s sponsor conduct specific pediatric studies. This is not an informal suggestion; it is a detailed document outlining the required trials, patient populations, and timelines.

- The Sponsor Conducts the Studies: The company must then conduct the clinical studies exactly as specified in the Written Request.

- The Sponsor Submits the Study Reports: Finally, the company submits the complete reports of these studies to the FDA.

Here is the most critical strategic point: the sponsor is rewarded simply for completing the work. The drug does not need to be proven safe or effective in children, nor does it need to gain an approved pediatric indication on its label to receive the six-month exclusivity. The reward is for generating the data the FDA requested, regardless of the outcome. This de-risks the endeavor for the company; the exclusivity is granted upon the FDA’s acceptance of the study reports as having met the terms of the Written Request.

The financial incentive is enormous. For a blockbuster drug generating $50 million per month in revenue, this “golden” six months translates directly into an additional $300 million of sales that would have otherwise been lost to generic competition.

Furthermore, the strategic leverage of pediatric exclusivity extends far beyond a single product. Because the six-month extension attaches to the active moiety, not just the specific drug product studied, it can act as a “master key” for a company’s entire portfolio. Imagine a company has a successful active moiety that it markets in three different products: an oral tablet for one indication, an extended-release version for another, and a topical cream for a third. By conducting the requested pediatric studies on just the oral tablet, the company can secure a six-month extension not only on the patents covering the tablet but also on all the patents covering the extended-release and topical cream formulations as well.49 This transforms the ROI calculation from a product-level decision to a portfolio-level strategic imperative. It makes pursuing pediatric exclusivity one of the highest-leverage investments a company can make in its lifecycle management plan, turning a regulatory obligation into a powerful, portfolio-wide commercial asset.

The “Rule of Ones”: Myth vs. Reality in Obtaining Multiple PTEs

We now arrive at the heart of our inquiry and one of the most sophisticated and contentious strategies in U.S. patent law: the quest for multiple Patent Term Extensions for a single product. The conventional wisdom, often repeated in legal circles, is the “Rule of Ones”: one patent may be extended for one product based on one regulatory review, resulting in one PTE. This rule is grounded in the statutory language of 35 U.S.C. § 156(c)(4), which states, “in no event shall more than one patent be extended… for the same regulatory review period for any product”.15 For years, this was considered the end of the story.

However, for a period of time, clever legal interpretation and strategic clinical development cracked this rule wide open, creating a pathway to what was once thought impossible. Yet, just as this strategy became established, a dramatic policy reversal by the USPTO has plunged it back into uncertainty, creating a new and unsettled landscape for IP strategists.

The Same-Day Approval Strategy: A Pathway to Multiple Extensions

The key to breaking the “Rule of Ones” lay in a careful reading of the statute. The law prohibits extending more than one patent for the same regulatory review period. What if, innovators asked, a single product was the subject of multiple, distinct regulatory review periods?

This question gave rise to a brilliant strategy. A company could, for example, develop two different formulations of a new drug (e.g., an oral tablet and an intravenous solution) or pursue two different initial indications in parallel. Each of these would require its own separate New Drug Application (NDA) and would therefore have its own distinct regulatory review period. The strategic challenge was to coordinate the clinical trials and regulatory submissions so that both NDAs would be approved by the FDA on the exact same day.

If this could be achieved, the company could argue that neither approval was the “first” relative to the other. Both represented the first permitted commercial marketing of the active ingredient. Since there were two distinct regulatory review periods culminating in approval on the same day, the company could apply for two separate PTEs on two different patents, each one tethered to one of the NDAs.

For years, the USPTO accepted this logic. This strategy was not merely theoretical; it was successfully executed by several major pharmaceutical companies, resulting in multiple, concurrent PTEs that extended the market exclusivity for their blockbuster drugs 42:

- Omnicef® (cefdinir): Two separate NDAs for different dosage forms were approved on the same day, leading to two PTEs on two different patents.

- Lyrica® (pregabalin): Two NDAs for different indications were approved on the same day, also resulting in two PTEs for two patents.

- Nesina® (alogliptin): This was the landmark case that solidified the strategy. In 2016, the USPTO granted an unprecedented three PTEs based on the same-day approval of three different NDAs: one for Nesina® itself (alogliptin), one for Kazano® (a combination with metformin), and one for Oseni® (a combination with pioglitazone). Each product had a different regulatory review period, and the innovator was able to extend three different patents, each tied to one of the three same-day approvals.

These successes transformed the “Rule of Ones” from a hard-and-fast rule into a rebuttable presumption. It created a powerful incentive for companies to undertake the enormous expense and complexity of running parallel clinical development programs, with the predictable and highly valuable reward of securing multiple layers of extended patent protection.

The USPTO’s Policy Reversal: Navigating the New, Unsettled Landscape

Just as the same-day approval strategy seemed to be established precedent, the ground shifted. In 2020, in a stunning and abrupt about-face, the USPTO began to reject this long-standing practice. In a series of letters to applicants, the office declared a new interpretation of the law: “Section 156 does not allow for multiple extensions of patents beyond the one patent per one approved product”.

The USPTO’s new rationale is that the statute’s requirement of a “first permitted commercial marketing or use” is singular. For any given active ingredient, there can be only one “first” day of approval. Even if multiple NDAs are approved on that day, they all share the same status as the “first” permission, and therefore, this single event can only support the extension of a single patent. The office has explicitly acknowledged that this is a reversal of its past practice but maintains that its new interpretation is the correct reading of the statute, citing recent court decisions (though the relevance of these citations has been questioned by legal experts).

This policy reversal has thrown the entire strategy into disarray and is currently being tested in high-profile cases. Gilead, for its cancer drug Zydelig®, and Pfizer, for its heart medication tafamidis (marketed as Vyndamax® and Vyndaqel®), both secured same-day approvals for different NDAs and have applied for multiple PTEs, only to be met with the USPTO’s new hardline stance. These cases are the current battleground, and their outcomes will determine the future viability of the multiple PTE strategy in the United States.

This shift represents a massive increase in regulatory risk and fundamentally changes the strategic calculus for pharmaceutical companies. What was once a known, albeit difficult, pathway to a predictable reward has become a high-stakes gamble. The R&D investment decisions made years ago, based on the assumption that parallel development could lead to multiple PTEs, may no longer yield their expected return. This seemingly arcane change in patent office policy has a direct and chilling effect on clinical trial design, R&D budgeting, and the speed at which new formulations and indications of vital medicines reach the market. For now, the “Rule of Ones” is back in force, and any attempt to challenge it must be undertaken with the full knowledge that it will likely lead to a protracted and uncertain legal battle with the USPTO.

The European Framework: Mastering the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC)

Crossing the Atlantic, we enter a different world of patent term restoration. The European system, governed by the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC), shares the same fundamental goal as the U.S. PTE system—to compensate for regulatory delays—but it achieves this through a legally distinct and strategically unique instrument. Understanding these differences is paramount for any company operating in the global pharmaceutical market, as a lifecycle management strategy that is brilliant in the U.S. can be completely ineffective in Europe, and vice versa.

Understanding the SPC: A Unique Right for a Unique Market

The first and most critical distinction to grasp is that an SPC is not a patent extension. It is a sui generis—or “of its own kind”—intellectual property right.17 While a U.S. PTE adds time directly to the term of the underlying patent, an SPC is a separate right that only comes into force the day

after the basic patent expires.17 This legal nuance has significant practical consequences for enforcement and litigation.

The legal framework for SPCs is established by EU regulations, primarily Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 for medicinal products.17 However, the administration of the system is highly fragmented. Unlike the centralized U.S. system, SPCs must be applied for and granted on a country-by-country basis in each member state of the European Economic Area (EEA) where protection is sought.17 This creates a significant administrative and cost burden, and has led to ongoing efforts by the European Commission to create a more streamlined “unified” or “unitary” SPC system, though this remains a work in progress.54

The duration of an SPC is also calculated differently. The formula is designed to provide a maximum of 15 years of total market exclusivity from the date of the first marketing authorization in the EEA.16 The term of the SPC itself is calculated as follows, subject to a five-year cap 17:

SPC Term=(Date of first EEA Marketing Authorisation)−(Date of basic patent filing)−5 years

This means that if the time between patent filing and the first marketing authorization is less than five years, no SPC term is available. If it is more than ten years, the SPC term is capped at five years.17

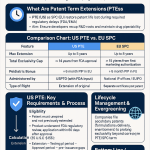

To provide a clear, at-a-glance comparison of these two complex systems, the following table highlights the key strategic differences between the U.S. PTE and the EU SPC.

| Feature | United States (Patent Term Extension – PTE) | European Union (Supplementary Protection Certificate – SPC) |

| Legal Basis | 35 U.S.C. § 156 (Hatch-Waxman Act) | Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 (Medicinal Products) |

| Nature of Right | An extension of the term of the basic patent itself. | A sui generis (unique) IP right that takes effect after the basic patent expires. 17 |

| Application Process | Centralized application to the USPTO. | National applications filed in each individual EU member state. 17 |

| Filing Deadline | Within 60 days of the first permitted commercial marketing approval. 10 | Within 6 months of the first Marketing Authorisation in the EEA (or 6 months from patent grant, whichever is later). 18 |

| Maximum Term | Up to 5 years. 15 | Up to 5 years. 17 |

| Overall Cap | Total effective patent life post-approval cannot exceed 14 years. 15 | Total protection (patent + SPC) generally cannot exceed 15 years from the first MA. 16 |

| Pediatric Extension | 6 months added to all existing patents and exclusivities for the active moiety. 49 | 6 months added to the SPC term itself (max 5.5 years). 17 |

| Eligible “Product” | The specific “active ingredient” (including salt/ester) in the approved product. 38 | The “active ingredient or combination of active ingredients.” 17 |

| New Formulations | Potentially eligible if the patent claims the new formulation and it’s the first approval of that specific product. | Ineligible if the active ingredient has been previously authorized (Abraxis). |

| New Uses/Indications | Potentially eligible if a method-of-use patent is extended based on the first approval for that use. | Ineligible if the active ingredient has been previously authorized (Santen). |

| Multiple Extensions | Historically possible via same-day approvals; now highly contested by the USPTO. Generally “one patent per product.” 42 | Possible to get multiple SPCs from one patent for different products, or for one product from different patents. 62 |

The Pediatric Extension: The Reward for PIP Compliance

Much like the U.S., the EU offers an incentive for conducting pediatric studies. However, the mechanism and scope are different. A six-month extension is available, but it is added directly to the term of the SPC, not to the underlying patent or other exclusivities. This can extend the maximum life of an SPC from 5 years to 5.5 years.17

To qualify, the company must conduct studies in accordance with a Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP) that has been agreed upon with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and include the results in their marketing authorization application.64 A critical procedural hurdle is that the application for the pediatric extension must typically be filed at least two years

before the SPC is due to expire, which demands significant long-range planning from clinical and regulatory teams.20 The key strategic difference from the U.S. system is its narrower scope: the EU pediatric extension benefits only the specific product for which the SPC was granted, whereas the U.S. extension provides a portfolio-wide benefit for the entire active moiety.

The Multiplicity Question in Europe: Stacking SPCs

The rules governing multiple SPCs in Europe are a complex tapestry woven from CJEU case law. The principles are quite different from those in the U.S., offering both unique opportunities and distinct limitations.

Multiple SPCs from a Single Patent: The Georgetown II Doctrine

One of the most significant departures from U.S. practice is the principle that a single basic patent can support multiple SPCs, provided they are for different “products.” This was clarified in a series of cases, notably the Georgetown University II decision.62

Imagine a single, broad patent that covers three distinct inventions: active ingredient A, active ingredient B, and the combination product A+B. If the company later obtains separate marketing authorizations for a monotherapy drug containing only A, and a combination therapy drug containing A+B, the Georgetown II doctrine allows the patent holder to obtain two separate SPCs from that single patent: one for “product” A and another for “product” A+B. This “one SPC per product, per patent” rule stands in stark contrast to the U.S. “one extension per patent” rule and provides a powerful avenue for extending protection for different commercial products that spring from a single foundational patent.

SPCs for Combination Products: Applying the CJEU’s “Invention Test”

While it is possible to get an SPC for a combination product, the CJEU has recently imposed a significant hurdle known as the “invention test.” This test arises from the requirement in Article 3(a) of the SPC Regulation that the “product is protected by a basic patent in force.” The question is, what does “protected” really mean in the context of a combination?

In the landmark Teva/Merck cases, the CJEU ruled that it is not enough for the basic patent to simply mention the combination of active ingredients A and B, for instance, in a dependent claim. To be truly “protected” for SPC purposes, the combination itself must be part of the core inventive concept of the patent. The court is essentially asking: “Is the invention of this patent just about compound A, or is the invention truly about the novel combination of A+B?”

This has led to inconsistent rulings in national courts as they grapple with how to apply this test. A French court found that a mere statement in the patent’s description about a potential “synergistic effect” was enough to satisfy the test. In contrast, a Swedish court, faced with a similar patent, ruled that a prediction of synergy without any supporting data or evidence in the patent was insufficient.

This legal uncertainty sends a clear and powerful message to IP strategists: patent applications must now be drafted with future SPC eligibility for combination products explicitly in mind. The old practice of simply adding a claim to “compound A plus a known drug B” is no longer sufficient. To secure an SPC for that combination down the line, the patent application itself should ideally contain data or a strong, detailed technical rationale demonstrating why the combination is inventive—for example, by showing an unexpected synergistic effect. This requires a level of foresight and integration between R&D and patent law departments that is more critical than ever before. A failure to build this case for inventiveness at the patent drafting stage, potentially a decade before an SPC is even considered, can permanently foreclose the opportunity to protect a valuable combination product.

The Hard Line: Why New Formulations and New Uses of Old Drugs Fail the Test

The CJEU’s philosophy on the purpose of SPCs becomes crystal clear when examining its rulings on new formulations and new therapeutic uses of existing drugs. Here, the court has drawn a very hard line, effectively shutting down two common lifecycle management strategies in the European context.

The key is the court’s strict interpretation of Article 3(d), which requires that the marketing authorization (MA) supporting the SPC application be the first authorization to place the “product” on the market.60 The CJEU has repeatedly defined “product” as the active ingredient itself.

- New Formulations: In the Abraxis case, the court ruled that a new formulation of a previously approved active ingredient does not constitute a new “product.” Therefore, an MA for a new formulation (e.g., an extended-release version) cannot be the “first authorization” if the active ingredient has ever been marketed before in any form. As a result, new formulations are ineligible for SPCs.

- New Uses/Indications: The landmark Santen decision applied the same logic to new therapeutic uses. Santen had developed a new ophthalmic use for ciclosporin, an active ingredient that had been approved decades earlier as an immunosuppressant. The CJEU ruled that the MA for the new ophthalmic product was not the “first authorization” for the product (ciclosporin) and was therefore ineligible to support an SPC.

These decisions reveal an overarching judicial philosophy: SPCs are intended as a reward for the high-risk, high-cost research that brings a fundamentally new therapeutic molecule to patients for the very first time. They are not intended to reward the incremental, follow-on research that characterizes much of modern pharmaceutical lifecycle management. This creates a major strategic divergence between the U.S. and Europe. An innovation like a new, patented extended-release formulation might be eligible for a PTE in the U.S., but it will receive zero additional SPC protection in Europe. This reality must be factored into the global ROI calculation for any lifecycle management project, as the potential for extended exclusivity can differ dramatically between the world’s two largest pharmaceutical markets.

Advanced Strategies and Execution

Understanding the intricate legal frameworks of the U.S. and Europe is only the first step. Translating that knowledge into a coherent, actionable strategy that maximizes the commercial life of a product is where true value is created. This requires breaking down the traditional silos between intellectual property, regulatory affairs, and clinical development teams. A successful lifecycle management plan must be a fully integrated, forward-looking endeavor that begins not when a patent is about to expire, but at the earliest stages of research and development.

Integrating IP and Regulatory Strategy for Maximum Term

The pursuit of multiple patent term extensions is a clear example of where IP and regulatory strategies are inextricably linked. The possibility of securing multiple PTEs in the U.S. via the same-day approval strategy, for instance, is not a decision that can be made by the legal department alone. It requires a conscious, strategic choice by the clinical development team to run expensive and complex trials in parallel for different formulations or indications. This decision must be made with a full understanding of the potential IP reward, but also with a clear-eyed assessment of the new regulatory risk created by the USPTO’s recent policy reversal. Is the potential for multiple extensions worth the gamble, or is a more conservative, serial development approach now more prudent?

Similarly, in Europe, the CJEU’s “invention test” for combination products has direct implications for patent drafting. IP attorneys can no longer draft patents in a vacuum. They must work closely with R&D scientists to understand and articulate why a combination is inventive and ensure that evidence of this inventiveness, such as data on synergistic effects, is included in the patent application itself. This proactive approach, years before an SPC application is even contemplated, can be the difference between securing a valuable SPC for a combination product and having the application rejected.

Flawless execution also depends on procedural mastery. The filing deadlines for these extensions are notoriously strict and unforgiving. The 60-day window following FDA approval in the U.S. and the six-month window in the EU leave no room for error.10 A single day’s delay can result in the forfeiture of years of potential market exclusivity worth hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars. This necessitates the creation of robust internal systems and clear communication channels between the regulatory teams who receive the approval notices and the IP teams who must file the applications.

Building a Resilient Portfolio: The Role of Secondary Patents and Patent Thickets

Patent term extensions, as powerful as they are, represent only one layer of a comprehensive lifecycle management strategy. The ultimate goal is to build a defensive fortress around a valuable product, and this is achieved through the strategic accumulation of secondary patents, creating what is often referred to as a “patent thicket”.33

While only one “primary” patent covering the core active ingredient can typically receive a PTE or SPC, a company can and should file numerous other patents covering every conceivable aspect of the product. This practice, sometimes criticized as “evergreening,” is a standard and essential defensive strategy.33 These secondary patents can cover:

- New Formulations: Extended-release versions, new dosage forms (e.g., oral to injectable), or formulations with improved stability or bioavailability.75

- New Methods of Use: Patents covering the treatment of new diseases or patient populations discovered after the initial approval.

- Combination Products: Combining the drug with other active ingredients to create a new therapy.

- Stereoisomers: Isolating a single, more effective enantiomer from a previously approved racemic mixture (a “chiral switch”).

- Manufacturing Processes: New, more efficient, or purer methods of synthesizing the drug.

A single blockbuster drug can be protected by a dense web of over 100 such patents, with staggered expiration dates that can extend the product’s total period of protection for years beyond the expiration of the original composition-of-matter patent.33 While these secondary patents may not be eligible for PTE or SPC, they still serve as a formidable barrier to entry for generic competitors. Any generic company wishing to launch must navigate this thicket, either by designing around the patents or by challenging their validity in court—a costly and time-consuming process that can delay generic entry and preserve the innovator’s market share.

The Orange Book and Beyond: Strategic Patent Listings and Competitive Intelligence

In the U.S., the FDA’s publication, “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” known colloquially as the Orange Book, is not merely a regulatory database; it is a strategic battlefield. By law, an innovator company must submit to the FDA a list of all patents that claim the approved drug or a method of using it, which the FDA then lists in the Orange Book.77

This listing has immense strategic importance. When a generic company files an ANDA seeking to market a copy of the drug, it must make a certification regarding each patent listed in the Orange Book. If it files a “Paragraph IV” certification, alleging that a listed patent is invalid or will not be infringed by its generic product, this act is considered an act of patent infringement and gives the innovator the right to sue. The filing of that lawsuit automatically triggers a 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic drug, giving the innovator time to litigate the patent’s validity before the generic can enter the market.

This powerful 30-month stay has led to intense scrutiny of what gets listed in the Orange Book. The FTC has recently taken an aggressive stance against what it deems “improper” listings, such as patents that claim a device component of a drug-device combination (like an inhaler) but not the active ingredient itself.21 This new regulatory risk means that companies must be more judicious than ever in their listing strategies, balancing the defensive benefits of a broad listing against the potential for antitrust challenges.

Leveraging DrugPatentWatch to Forecast Expiry and Track Competitors

Navigating this complex landscape of patent expiries, extensions, and strategic listings is a data-intensive challenge. It is here that specialized competitive intelligence platforms become indispensable tools. Services like DrugPatentWatch provide the critical data and analytics necessary to move from a reactive, defensive posture to a proactive, strategic one.78

By aggregating and analyzing data from global patent offices, regulatory agencies, and litigation records, these platforms offer a multi-faceted view of the competitive environment. A company can use DrugPatentWatch to:

- Forecast Loss of Exclusivity (LOE): Systematically track the expiration dates of key patents for competitor products, including any granted PTEs, SPCs, or pediatric exclusivities. This allows for precise forecasting of when a market will open up to generic competition, informing both defensive strategies for one’s own products and offensive strategies for generic or biosimilar development.80

- Analyze Competitor Pipelines: Patent applications are typically published 18 months after filing, providing an early-warning system for a competitor’s R&D activities long before a product is announced or enters clinical trials. By monitoring these filings in specific therapeutic areas, a company can gain invaluable insights into a rival’s research direction, identify emerging threats, and spot potential “white space” opportunities for its own pipeline.

- Deconstruct Patent Thickets: Analyze the full patent portfolio surrounding a competitor’s blockbuster drug to understand the strength and depth of their “patent thicket.” This intelligence is crucial for generic companies planning a Paragraph IV challenge, as it helps identify the weakest patents in the portfolio and formulate a targeted litigation strategy.

Ultimately, proactive competitive intelligence transforms a company’s strategic capabilities. Instead of simply managing its own IP portfolio in isolation, it can understand and anticipate the moves of its competitors. This landscape-level view, powered by platforms like DrugPatentWatch, enables more accurate financial forecasting, better-informed R&D investment decisions, and the ability to time market entries and product launches with surgical precision. It is the key to not just playing the game, but shaping the board itself.

Procedural Mastery: A Practical Guide to Filing and Avoiding Pitfalls

All the brilliant strategy in the world is for naught if the execution is flawed. The application processes for PTEs and SPCs are rigid, deadline-driven, and unforgiving. A simple procedural error can lead to the complete forfeiture of a valuable extension. This section provides a practical checklist of key requirements and common mistakes to avoid.

For a U.S. Patent Term Extension (PTE) application, the process is governed by 37 C.F.R. § 1.740. Key requirements include 15:

- The 60-Day Deadline: The application must be submitted to the USPTO within 60 days of the FDA’s marketing approval date. This is an absolute, non-extendable deadline.

- Applicant: The application must be filed by the owner of record of the patent or its authorized agent.

- Content: The application is a detailed document that must include:

- A complete identification of the approved product and the federal statute under which it was reviewed.

- The identity of the patent for which extension is sought, and a clear statement of which claims cover the approved product.

- All relevant dates needed to calculate the regulatory review period (e.g., IND effective date, NDA submission date, approval date).

- A calculation of the patent term extension being claimed.

For a European Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC), the process is governed by national patent offices, but the requirements are harmonized by EU regulations 17:

- The 6-Month Deadline: The application must be filed within six months of the date on which the first Marketing Authorisation (MA) was granted in the EEA, or within six months of the date the basic patent was granted, whichever is later.18

- Applicant: The application must be filed by the holder of the basic patent.

- Content: The application must include:

- A request for the grant of an SPC.

- A copy of the MA that identifies the product.

- The number of the basic patent and its title.

Common and Costly Pitfalls to Avoid:

Drawing from common errors in complex application processes, several pitfalls stand out for PTE and SPC filings 87:

- Missing the Filing Deadline: This is the most common and catastrophic error. Robust internal calendaring and communication between regulatory and IP teams are essential to prevent this.

- Incorrect Patent Selection: Especially in the U.S., where only one patent can be extended, choosing the wrong one can be a major strategic blunder. As discussed, the patent with the most PTA is not always the best choice due to its vulnerability to terminal disclaimers. A thorough analysis of the entire patent family is required.

- Misunderstanding the “Product”: Filing an SPC application in Europe based on a new formulation or new use of a previously approved active ingredient is a guaranteed rejection in light of the Abraxis and Santen decisions. Similarly, filing a U.S. PTE application based on a product whose active ingredient (or a salt/ester thereof) has already been approved will fail the “first permitted use” test.

- Incomplete or Inaccurate Information: Any errors in the dates provided for the regulatory review period calculation can lead to a shorter extension or a complete rejection. Meticulous record-keeping throughout the entire R&D and regulatory process is vital.

- Failure to Coordinate Globally: A decision made in one jurisdiction can impact another. For example, the timing of the first MA anywhere in the EEA starts the clock for all SPC applications across Europe. A coordinated global strategy is essential to avoid inadvertently compromising rights in a key market.

Synthesizing the Strategies: A Global Approach to Maximizing Product Lifecycles

The journey through the complex landscapes of U.S. PTEs and European SPCs reveals a clear, overarching truth: maximizing the commercial life of a pharmaceutical product is a global chess match, not a series of independent games. The rules differ significantly from one side of the board to the other, and a winning strategy requires a sophisticated, globally coordinated approach that is tailored to the unique legal and regulatory realities of each major market.

In the United States, the strategy revolves around a deep understanding of the Hatch-Waxman Act’s “grand bargain.” The potential for a portfolio-wide, six-month windfall from pediatric exclusivity makes it a high-priority strategic goal. The now-risky but potentially high-reward “same-day approval” strategy for multiple PTEs highlights the need for a tight integration of clinical, regulatory, and IP planning, balanced by a realistic assessment of the USPTO’s current adversarial stance. The key is to leverage the literal definitions within the U.S. code while building a resilient “patent thicket” to deter generic challenges.

In Europe, the focus shifts to the sui generis nature of the SPC and the judicial philosophy of the CJEU. The strategy here is less about extending a single patent and more about securing separate rights for distinct products emerging from a foundational patent. The CJEU’s hard line against extensions for new formulations and new uses of old drugs means that lifecycle management strategies must be fundamentally different from those in the U.S. The emphasis must be on demonstrating true, front-loaded innovation, particularly for combination products, where the case for inventiveness must be built into the patent application from day one.

Looking ahead, this landscape will continue to evolve. The push for a unitary SPC system in Europe could one day simplify the administrative burden, but it may also introduce new complexities.54 In the U.S., increased scrutiny from the FTC on patent listing practices and the ongoing legal battles over the multiple PTE doctrine will continue to shape the boundaries of permissible strategy.21 Success will belong to those organizations that not only master the current rules but also anticipate and adapt to the changes on the horizon. The art of the second act is not a static discipline; it is a dynamic process of continuous learning, strategic adaptation, and flawless execution.

“Pharmaceutical companies gain an average three years in monopoly protections on branded drugs by filing multiple secondary patents… These exclusivity extensions cost U.S. patients, insurance companies and other drug buyers about $148.3 million per drug by delaying competition from producing far cheaper generic brands.”

— Charu Gupta, UCLA Anderson School of Management

Key Takeaways

- “Effective Patent Life” is the Key Metric: The standard 20-year patent term is misleading. The true measure of a drug’s commercial opportunity is its “effective patent life”—the time it is on the market with exclusivity. Patent term extensions are a critical tool for maximizing this period.

- PTE and SPCs Are Fundamentally Different: U.S. Patent Term Extension (PTE) extends the life of a single patent. European Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) are separate IP rights that take effect after a patent expires. This legal distinction drives major strategic differences.

- The U.S. vs. EU Strategic Divide: A lifecycle management strategy based on a new formulation or new use of an existing drug may be viable for a PTE in the U.S. but is definitively ineligible for an SPC in the EU. Global strategies must be bifurcated to account for this.

- Multiple Extensions Are Possible, But Challenging: In the EU, one patent can support multiple SPCs for different products. In the U.S., the historic “same-day approval” strategy for multiple PTEs is now highly contested by the USPTO, making it a high-risk endeavor.

- Pediatric Exclusivity is a Portfolio-Wide Asset: In the U.S., the six-month pediatric exclusivity is uniquely powerful because it extends all patents and exclusivities for an active moiety, making it a high-leverage strategic goal with portfolio-wide benefits.

- Proactive Strategy is Essential: Maximizing patent term is not a last-minute activity. It requires integrating IP, regulatory, and clinical development strategies from the earliest stages of R&D, including drafting patents with future extension eligibility in mind.

- Competitive Intelligence is Non-Negotiable: Understanding the patent expiry and extension strategies of competitors is crucial. Tools like DrugPatentWatch are essential for forecasting market dynamics, identifying opportunities, and deconstructing competitor patent thickets.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. In the U.S., if I have two patents covering my approved drug, one with 500 days of PTA and one with zero PTA, which one should I choose for a PTE?

This is a classic strategic dilemma. While extending the patent with 500 days of PTA would result in the longest theoretical term, it may not be the wisest choice. That PTA is vulnerable to being eliminated if a terminal disclaimer was filed (or is later required in litigation) over an earlier-expiring patent in the family. The PTE, however, is immune to this threat.34 Therefore, a more conservative and resilient strategy is often to apply the PTE to the patent with zero PTA. This “banks” the full, defensible PTE term and avoids the risk of having the PTA portion of the other patent’s term invalidated by a double-patenting challenge. The decision requires a careful risk assessment of the entire patent portfolio.

2. My company has a patent on a new extended-release formulation of a drug whose active ingredient was first approved in Europe ten years ago. Can we get an SPC for this new formulation?

No. Based on the CJEU’s clear and consistent case law, particularly the Abraxis decision, an SPC cannot be granted for a new formulation of a previously approved active ingredient. The SPC regulation requires the marketing authorization to be the first authorization for the “product” (defined as the active ingredient) in the EEA. Since the active ingredient was approved a decade ago, any subsequent MAs for new formulations or new uses of that same active ingredient are not considered the “first” and cannot support an SPC.

3. We are developing a combination drug in Europe where our novel compound is combined with a well-known generic drug. What is the single most important thing we can do now at the patent drafting stage to improve our chances of getting an SPC for the combination product later?

You must build a case for the inventiveness of the combination itself within the text of your patent application. Following the CJEU’s “invention test” from the Teva/Merck cases, it is no longer sufficient to simply claim “our compound + generic drug”. You should include experimental data, or at least a detailed and credible scientific rationale, in the patent’s description demonstrating that the combination provides an unexpected or synergistic effect. This evidence helps prove that the combination is not just a simple aggregation of known elements but is central to the “invention covered by the basic patent,” which is now a prerequisite for securing a combination SPC.

4. The USPTO has reversed its policy on allowing multiple PTEs for same-day approvals. Is there any strategic reason to still pursue parallel development of two NDAs for a single product?

While the primary IP reward is now highly uncertain, there may still be commercial or regulatory reasons to do so. For example, having two different formulations (e.g., oral and IV) available at launch could capture a wider patient market from day one. Or, launching with two distinct indications simultaneously could establish a broader clinical profile and competitive advantage. However, from a purely IP perspective, the justification is much weaker. The enormous cost of parallel development must now be weighed against the possibility of winning a protracted legal battle against the USPTO to secure a second PTE. It has shifted from a predictable IP strategy to a high-risk, high-cost legal and commercial gamble.

5. How can a tool like DrugPatentWatch help me decide whether to challenge a competitor’s patent extension?

A platform like DrugPatentWatch provides the critical data needed for such a decision. First, it allows you to see the full patent landscape around the competitor’s drug, including all listed patents and their expiration dates, helping you identify which patent was extended. Second, by providing litigation history and data on Paragraph IV challenges, you can assess how robust that specific patent has been against previous challenges. Third, you can analyze the regulatory history to verify the PTE calculation, checking the IND, NDA, and approval dates to ensure the extension period was determined correctly and that there were no undisclosed periods of applicant delay. This comprehensive data allows you to move from a guess to a data-driven assessment of whether a legal challenge has a reasonable probability of success.

References

- 2701-Patent Term – USPTO, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2701.html

- Patent term: how to calculate the expiration date of an EP patent? – Obtaining an EP Patent – A crash course for the US applicant #7 | Plasseraud IP, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.plass.com/en/articles/patent-term-how-calculate-expiration-date-ep-patent-obtaining-ep-patent-crash-course-us

- When Does My Patent Expire? – Gesmer Updegrove LLP, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.gesmer.com/publications/when-does-my-patent-expire/

- Understanding Patent Term Extensions: An Overview – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-patent-term-extensions-an-overview/

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? – PMC, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/

- The Economics of Drug Discovery and the Impact of Patents – R Street Institute, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-economics-of-drug-discovery-and-the-impact-of-patents/

- Patent and Marketing Exclusivities 101 for Drug Developers – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10242760/

- The Impact of Drug Patent Expiration: Financial Implications, Lifecycle Strategies, and Market Transformations – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Drug Patent Expirations and the “Patent Cliff” – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/drug-patent-expirations-and-the-patent-cliff

- 2750-Patent Term Extension for Delays at other Agencies under 35 …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2750.html

- Patent Term Extensions and the Last Man Standing | Yale Law & Policy Review, accessed July 28, 2025, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/patent-term-extensions-and-last-man-standing

- The Hatch-Waxman Act and Its Effect on the Term of a U.S. Patent, accessed July 28, 2025, https://grr.com/publications/the-hatch-waxman-act-and-its-effect-on-the-term-of-a-u-s-patent/

- Understanding the Statute on Patent Term Extension – IPWatchdog.com, accessed July 28, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2024/10/28/understanding-statute-patent-term-extension/id=182598/

- PATENT TERM EXTENSION FOR FDA-APPROVED PRODUCTS – Mayer Brown, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/perspectives-events/publications/2024/04/240410-wdc-webinar-lifesci-successfully-navigating-slides.pdf?rev=537cb0623a9841a1ad320d7e52889377

- Patent Term Extension – Sterne Kessler, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/patent-term-extension/

- Patent Term Extensions | Merck.com, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.merck.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/124/2023/12/Patent-Term-Extensions_MRK_DEC11.pdf

- Supplementary protection certificate – Wikipedia, accessed July 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supplementary_protection_certificate

- European Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) for Pharmaceuticals – Gill Jennings & Every LLP, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.gje.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/European-Supplementary-Protection-Certificates-SPCs-for-pharmaceuticals-A-practical-guide-2022.pdf

- Supplementary protection certificates – Efpia, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.efpia.eu/about-medicines/development-of-medicines/intellectual-property/supplementary-protection-certificates/

- Introduction to Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) – Dyoung, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.dyoung.com/en/knowledgebank/faqs-and-guides/spcs

- What the FTC Gets Wrong About the FDA’s Orange Book, accessed July 28, 2025, https://cip2.gmu.edu/2024/11/18/what-the-ftc-gets-wrong-about-the-fdas-orange-book/

- FTC Revives Orange Book Listing Challenges – McDermott Will & Emery, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.mwe.com/insights/ftc-revives-orange-book-listing-challenges/

- Republican FTC renews challenges to Orange Book patent listings – Hogan Lovells, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.hoganlovells.com/en/publications/republican-ftc-renews-challenges-to-orange-book-patent-listings

- The Current Status of FTC’s Orange Book Listings Challenge: A Mixed Bag, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/current-status-ftcs-orange-book-listings-challenge-mixed-bag

- The FTC Challenges Companies’ Allegedly Improper Orange Book Patent Listings | Insights | Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2024/06/quarterly-insights/the-ftc-challenges-companies

- US FTC Continues Aggressive Scrutiny of Pharmaceutical Patents Listed in the Orange Book | Insights | Mayer Brown, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/insights/publications/2024/05/us-ftc-continues-aggressive-scrutiny-of-pharmaceutical-patents-listed-in-the-orange-book

- Reclaiming Their Time: Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE) Post Supernus, Novartis I, and Novartis II | Finnegan, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/blogs/prosecution-first/reclaiming-their-time-patent-term-adjustment-pta-and-patent-term-extension-pte-post-supernus-novartis-i-and-novartis-ii.html

- Maximizing Patent Term in the United States: Patent Term Adjustment, Patent Term Extension, and the Evolving Law of Obviousness-Type Double Patenting | Thought Leadership, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.bakerbotts.com/thought-leadership/publications/2025/january/maximizing-patent-term-in-the-united-states

- What is the difference between the Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE)? – Wysebridge Patent Bar Review, accessed July 28, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-the-patent-term-adjustment-pta-and-patent-term-extension-pte

- What is the difference between “patent term adjustment” and “patent term extension”?, accessed July 28, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-patent-term-adjustment-and-patent-term-extension

- Patent Term Adjustment and Extension | 2 Important Practices, accessed July 28, 2025, https://carsonpatents.com/patent-term-adjustment/

- Patent Term Adjustment Data June 2025 – USPTO, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/dashboard/patents/patent-term-adjustment-new.html

- Patent Problems Create Higher Drug Prices. Time to Fix the System – R Street Institute, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/patent-problems-create-higher-drug-prices-time-to-fix-the-system/

- Federal Circuit Holds Patent Term Adjustment May Lead To Invalidation by Obviousness-Type Double Patenting for Related Patents | Crowell & Moring LLP, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.crowell.com/en/insights/client-alerts/federal-circuit-holds-patent-term-adjustment-may-lead-to-invalidation-by-obviousness-type-double-patenting-for-related-patents

- Patent Term Adjustments in Jeopardy After In re Cellect – WilmerHale, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.wilmerhale.com/en/insights/client-alerts/20230829-patent-term-adjustments-in-jeopardy-after-in-re-cellect

- 2751-Eligibility Requirements – USPTO, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2751.html

- Pharmaceutical Patent Term Extension: An Overview – Alacrita, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/whitepapers/pharmaceutical-patent-term-extension-an-overview

- 35 U.S. Code § 156 – Extension of patent term – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/35/156

- blueironip.com, accessed July 28, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-is-considered-a-product-for-patent-term-extension-purposes/#:~:text=For%20patent%20term%20extension%20purposes%2C%20the%20term%20%E2%80%9Cproduct%E2%80%9D%20is,certain%20limitations%20on%20manufacturing%20processes)

- What is considered a “product” for patent term extension purposes? – BlueIron IP, accessed July 28, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-is-considered-a-product-for-patent-term-extension-purposes/

- 37 CFR § 1.710 – Patents subject to extension of the patent term. – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/37/1.710

- Surely You Must be Kidding, PTO?!? “No, and Don’t Call Me Shirley …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.thefdalawblog.com/2024/02/surely-you-must-be-kidding-pto-no-and-dont-call-me-shirley-the-seemingly-slapstick-but-yet-unfunny-world-of-recent-patent-term-extension-decisions-part-1/

- Patent Term Extension Considerations For Regulated Products | Sterne Kessler, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/patent-term-extension-considerations-regulated-products/

- Patent Term Extension under 35 USC § 156, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.aipla.org/docs/default-source/committee-documents/bcp-files/mtill_pte.pdf

- Patent Term Extension Statistics: What Innovators Need to Know – PatentPC, accessed July 28, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-term-extension-statistics-what-innovators-need-to-know

- Patent Term Extension and the Active Ingredient Problem, accessed July 28, 2025, https://jipel.law.nyu.edu/patent-term-extension-and-the-active-ingredient-problem/

- Incentivizing Pharmaceutical Pediatric Data with Patent Extensions – Cornell Law School, accessed July 28, 2025, https://publications.lawschool.cornell.edu/jlpp/2023/11/27/incentivizing-pharmaceutical-pediatric-data-with-patent-extensions/

- Benefits of FDA Pediatric Exclusivity – Pharmaceutical Law Group, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.pharmalawgrp.com/blog/4/benefits-of-fda-pediatric-exclusivity/

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- Qualifying for Pediatric Exclusivity Under Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act – FDA, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/qualifying-pediatric-exclusivity-under-section-505a-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-frequently

- New FDA Draft Guidance Aims to Limit Pediatric Exclusivity Extension Awards, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.pharmalawgrp.com/blog/20/new-fda-draft-guidance-aims-to-limit-pediatric-exclusivity-extension-awards/

- Pediatric Exclusivity and Extensions – Umbrex, accessed July 28, 2025, https://umbrex.com/resources/industry-analyses/how-to-analyze-a-pharmaceutical-company/pediatric-exclusivity-and-extensions/

- How to Obtain Multiple Patent Term Extensions for a Single Product …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.troutman.com/insights/how-to-obtain-multiple-patent-term-extensions-for-a-single-product.html

- Supplementary Protection Certificates: Future developments in Europe ? – Regimbeau, accessed July 28, 2025, https://regimbeau.eu/en/insight/supplementary-protection-certificates-future-developments-in-europe/

- Regulation – 469/2009 – EN – EUR-Lex – European Union, accessed July 28, 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/469/oj/eng

- Q&A on the Supplementary Protection Certificates – European Commission, accessed July 28, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/el/QANDA_23_2455

- Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPC) – Franks & Co, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.franksco.com/media/bhjj02j1/supplementaryprotectioncertificates.pdf

- Supplementary protection certificates for pharmaceutical and plant protection products – European Commission – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, accessed July 28, 2025, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/strategy/intellectual-property/patent-protection-eu/supplementary-protection-certificates-pharmaceutical-and-plant-protection-products_en

- Patent Term Extension for Drugs not Limited to new Chemical …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-term-extension-for-drugs-not-limited-to-new-chemical-entities/

- SPCs: new formulations of previously marketed … – D Young & Co, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.dyoung.com/en/knowledgebank/articles/spc-new-formulations

- CJEU does a U-turn: SPCs are not available for new therapeutic …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.schlich.co.uk/cjeu-does-a-u-turn-spcs-are-not-available-for-new-therapeutic-applications/

- SPC Blog – Part 4: One SPC per product (Article 3(c)) – Brantsandpatents, accessed July 28, 2025, https://brantsandpatents.com/en/news/spc-blog–part-4-ensuring-single-protection-article-3c

- More than One Supplementary Protection Certificate for One Basic Patent? | Insights | Jones Day, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2013/12/one-for-all-or-one-for-one-more-than-one-supplementary-protection-certificate-for-one-basic-patent

- Paediatric extensions to SPCs – Taylor Wessing, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.taylorwessing.com/en/insights-and-events/insights/2013/10/paediatric-extensions-to-spcs

- Paediatric extensions to Supplementary Protection Certificates in the EU / EEA and UK, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.jakemp.com/knowledge-hub/paediatric-extensions-to-supplementary-protection-certificates-in-the-eu-eea-and-uk/

- Paediatric extensions – Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.ige.ch/en/protecting-your-ip/patents/after-your-patent-has-been-granted/the-supplementary-protection-certificate-spc/paediatric-extensions

- Revision of the EU legislation on medicines for children and rare diseases – European Parliament, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/747440/EPRS_BRI(2023)747440_EN.pdf

- What are Paediatric Extensions and how do they work – MPA Business Services, accessed July 28, 2025, http://mpasearch.co.uk/paediatric-extensions

- Recent Decisions of the European Court of Justice of the European Union on Supplementary Protection Certificates: A Few Answers—Many Questions, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4208616/

- National courts apply the CJEU’s “invention test” for combination …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.jakemp.com/knowledge-hub/national-courts-apply-the-cjeus-invention-test-for-combination-spcs-and-differ-in-their-application/

- EU court limits pharma’s scope for patent extensions – Pinsent Masons, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/cjeu-pharma-patent-extensions-limited

- $52.6 Billion: Extra Cost to Consumers of Add-On Drug Patents – UCLA Anderson Review, accessed July 28, 2025, https://anderson-review.ucla.edu/52-6-billion-extra-cost-to-consumers-of-add-on-drug-patents/

- Biopharmaceutical Patenting: The Controversy Over Evergreening | PatentPC, accessed July 28, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patenting-the-controversy-over-evergreening

- Drug patents: the evergreening problem – PMC, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3680578/

- Strategies forExtending theLifeofPatents, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.alston.com/-/media/files/insights/publications/2005/05/strategies-for-extending-the-life-of-patents/files/biopharm-spruill-may2005/fileattachment/biopharm-spruill-may2005.pdf

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Patent Listing in FDA’s Orange Book – Congress.gov, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12644

- Drug Patent Research: Expert Tips for Using the FDA Orange and …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drug-patent-research-expert-tips-for-using-the-fda-orange-and-purple-books/

- How to Track Competitor R&D Pipelines Through Drug Patent Filings – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-track-competitor-rd-pipelines-through-drug-patent-filings/

- The Strategic Value of Orange Book Data in Pharmaceutical Competitive Intelligence, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-strategic-value-of-orange-book-data-in-pharmaceutical-competitive-intelligence/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed July 28, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- DrugPatentWatch not only saved us valuable time in tracking patent expirations but also streamlined our processes, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- DrugPatentWatch Highlights 5 Strategies for Generic Drug Manufacturers to Succeed Post-Patent Expiration – GeneOnline News, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drugpatentwatch-highlights-5-strategies-for-generic-drug-manufacturers-to-succeed-post-patent-expiration/

- Formal Requirements for Patent Term Extension Application – BlueIron IP, accessed July 28, 2025, https://blueironip.com/ufaqs/what-are-the-formal-requirements-for-a-patent-term-extension-application/

- 2752-Patent Term Extension Applicant – USPTO, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2752.html

- Supplementary Protection Certificates – Guide for Applicants, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.gnaipr.com/NoticeGnaipr/Supplementary%20Protection%20Certificates%20-%20Mar%2009.pdf

- Common PTE Mistakes and How to Avoid Them – Edulyte, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.edulyte.com/blog/common-pte-mistakes/