The statutory patent term for a novel pharmaceutical is nominally 20 years from the earliest effective filing date.1 However, this duration is frequently misleading when assessing the commercial lifespan of a drug product.2 The patent clock begins running during the initial discovery or clinical trial phase, often years before a therapeutic candidate reaches the market.2 Consequently, a substantial portion of the nominal term is eroded by the mandatory research, development, and stringent regulatory review phases, which can consume five to ten years of the granted term before commercial sales commence.1

To counteract this inevitable erosion, the United States intellectual property framework relies on the seminal Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.3 This legislation provides crucial corrective instruments: Patent Term Extension (PTE) to compensate for U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory review delays, Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) to compensate for U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) administrative delays, and a complex matrix of statutory regulatory exclusivities (e.g., NCE, ODE).3

This report provides an exhaustive, mechanistic analysis of these instruments. The analysis demonstrates that while these mechanisms are designed to restore lost time, strategic utilization of secondary patents, new formulation patents, and regulatory approval pathways often allows innovators to construct “patent fortresses,” resulting in periods of effective market exclusivity (EME) that significantly exceed the intended compensation, thereby maximizing portfolio valuation and delaying generic competition until the predetermined Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date.1

Section 1: Foundations of Pharmaceutical Intellectual Property (IP)

1.1. The Nominal 20-Year Patent Term: Filing Date and Early Erosion

Under 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2), the foundational legal principle dictates that the nominal patent term is 20 years, calculated from the earliest effective filing date of the application.1 For the life sciences industry, this statutory baseline creates a structural disadvantage: the filing of a foundational patent often occurs early in the discovery phase, initiating the 20-year clock before the molecule has completed preclinical testing or entered the costly, multi-phase clinical trial process.1

The consequence of this early start is that market exclusivity is immediately compromised. The average research and development lifecycle routinely consumes years of the patent term before marketing approval is even sought. Furthermore, the period between the patent filing date and the patent grant date, known as patent pendency, also contributes significantly to this erosion. For a sample of New Chemical Entities (NCEs), the average patent pendency period was calculated at 3.8 years.6 This time loss is compounded for complex inventions, where the top 20% of applications in terms of pendency averaged 8.49 years from filing to grant.6

The current system, resulting from the GATT/TRIPS international agreements, replaced the older “17 years from grant” rule with the “20 years from filing” rule. This structural change imposes a direct, quantifiable penalty on drugs requiring long development cycles. Since the life is now determined by the earliest date of filing, lengthy pre-market testing and lengthy USPTO prosecution delays inherently reduce the effective market life unless specific corrective mechanisms are applied.6 This structural erosion makes Patent Term Extension a necessary legislative correction to preserve the economic incentive required for highly risky pharmaceutical innovation.

1.2. The Pivotal Compromise: The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch-Waxman Act)

The Hatch-Waxman Act serves as the cornerstone of pharmaceutical IP and regulatory affairs in the United States, embodying a legislative trade-off designed to facilitate generic drug access while maintaining adequate innovation incentives for brand manufacturers.4

The Act established the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway (505(j)), which allows generic manufacturers to rely on the brand manufacturer’s clinical trial data to prove safety and efficacy, thus dramatically reducing generic development costs and expediting the approval timeline.3 To further incentivize generic entry, the Act created the Paragraph IV certification framework, enabling generic manufacturers to challenge innovator patents early in court.7 Furthermore, the first generic manufacturer to successfully file a Paragraph IV certification is granted 180 days of market exclusivity, providing a substantial competitive advantage.3

In exchange for this expedited generic entry pathway, the Act provided innovators with two essential tools to safeguard their investments: the restoration of patent time lost during regulatory review (PTE) and the establishment of regulatory data exclusivities (e.g., 5-year NCE, 3-year NCI).3 This dual mandate aims to balance the needs of innovators, who assume significant risks and costs in drug development, with the public health interest in timely access to low-cost generic alternatives.3

1.3. Defining the Moment of Commercial Jeopardy: The Patent Cliff and Loss of Exclusivity (LOE)

For business development teams and investors, the accurate determination of a drug’s valuation depends fundamentally on the Effective Market Exclusivity (EME)—the time between commercial launch and the moment competition enters the market.1 This moment is known as the “Patent Cliff,” defined as the expiration of the last enforceable intellectual property right, encompassing the final patent and any relevant regulatory exclusivity that prevents generic or biosimilar entry.1

The financial implications of crossing the LOE boundary are profound and immediate. When patents lapse, the entry of generics and biosimilars triggers a dramatic revenue decline.8 Small-molecule drugs typically face rapid market share erosion, often losing up to 90% of revenue within months.8 This is accompanied by significant price deflation: the average price of oral medications declines by about 25%, while physician-administered drugs experience even steeper drops, ranging between 38% and 48% following patent expiration.8 Although biosimilar competition for biologics is generally slower, resulting in a 30% to 70% decline in the first year due to complex production and slower clinical adoption, the financial impact remains severe.8

The scale of this challenge confirms that IP strategy has evolved beyond a purely legal concern to become a central issue of corporate financial stability. The pharmaceutical industry is currently facing a projected $236 billion patent cliff between 2025 and 2030, involving approximately 70 high-revenue products.8 Managing this risk requires an integrated approach across legal, regulatory, and financial planning departments to model the precise LOE date and develop mitigating strategies for maintaining profitability.1

Section 2: Mechanisms for Recovering Lost Patent Time

The recovery of lost patent time in the U.S. system is achieved through two distinct, potentially additive statutory mechanisms: Patent Term Extension (PTE) and Patent Term Adjustment (PTA).

2.1. Patent Term Extension (PTE) under 35 U.S.C. § 156

PTE is the key mechanism under the Hatch-Waxman Act designed exclusively to restore patent life lost during the period of mandatory regulatory review by the FDA.2

2.1.1. Eligibility Criteria and Statutory Limitations

To be eligible for PTE, the patent must claim the drug, a method of using the drug, or a method of manufacturing the drug, and the drug product must have received its first regulatory marketing approval (NDA or BLA).9

Statutory limitations place a hard ceiling on the compensation granted:

- Maximum Duration: The maximum allowable extension is five (5) years.2

- Effective Patent Life Cap: The extension cannot result in a total remaining patent term, measured from the date of regulatory approval up to the extended patent expiration date, that exceeds fourteen (14) years.2 This 14-year effective life rule establishes the statutory goal for post-approval market exclusivity guaranteed by the PTE mechanism.

- One Extension Rule: Only one patent can be extended per approved drug product.

2.1.2. Mechanistic Calculation of PTE

The USPTO calculates the length of the extension using a complex statutory formula that relies on the regulatory review period (RRP) determined by the FDA.10 The calculation compensates for time spent during clinical testing and regulatory approval.

The calculation is the sum of the regulatory “testing period” and the “approval period,” minus specific time periods attributable to applicant delays or pre-grant time.9

- Testing Period (TP): This period begins on the effective date of the Investigational New Drug (IND) application and concludes on the date of initial submission of the NDA/BLA.9

- Approval Period (AP): This period starts on the NDA/BLA initial submission date and ends on the date the FDA grants approval.9

A crucial complexity arises because the NDA/BLA submission date is counted in both the testing period and the approval period.9 The core principle is that the patent holder is compensated for half of the time spent in testing plus all the time spent in approval, with deductions for applicant delays (due diligence) or time occurring before the patent was granted.

The PTE calculation formula involves subtracting periods that occurred before the patent was granted (PGRRP) and periods of delay attributable to the applicant’s lack of due diligence (DD).10 Specifically, the inclusion of the Due Diligence (DD) variable in the formula necessitates that innovator companies rigorously document all regulatory interactions. This is because generic challengers frequently scrutinize regulatory records, attempting to prove that the innovator intentionally or negligently delayed responses to the FDA during the RRP. Successfully proving a lack of due diligence results in a subtraction from the calculated PTE, effectively reducing the brand manufacturer’s monopoly period. This transforms accurate RRP documentation into a critical legal defense tool.

2.2. Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) under 35 U.S.C. § 154

Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) operates independently of PTE. Its purpose is to compensate patent applicants for delays caused by the USPTO during the patent prosecution process.11

2.2.1. Purpose and Mechanism

PTA restores time lost to administrative inefficiencies, ensuring that the innovator receives the full benefit of the 20-year term despite bureaucratic processing delays. PTA is triggered when the USPTO fails to meet specific compliance deadlines.11

The significance of PTA lies in its additive nature: it adds directly to the nominal 20-year term and runs concurrently with any PTE granted. Unlike PTE, which is limited by the 14-year effective term rule, PTA has no statutory maximum duration.11

2.2.2. Triggers for Adjustment (A, B, and C Delays)

PTA is calculated based on three categories of USPTO failure to meet prescribed deadlines:

- A-Delay (14-Month Trigger): Occurs if the USPTO fails to issue a first Office action (or a notice of allowance) within 14 months of the application filing date.11

- B-Delay (4-Month Trigger): Results from the USPTO failing to respond to an applicant’s amendment within 4 months, or failing to issue the patent within 4 months after the issue fee is paid.11

- C-Delay: Delays resulting from certain administrative or appellate review procedures (e.g., secrecy orders or Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) decisions).11

The interaction between PTE and PTA is crucial for determining the final Loss of Exclusivity date. PTA is calculated and granted at the time of patent issuance, establishing the extended baseline expiration date. The subsequent PTE calculation then utilizes this PTA-adjusted date as the starting point for its own regulatory extension. Therefore, an innovator facing substantial administrative USPTO delays (high PTA) combined with lengthy FDA review periods (high PTE) can secure a total patent term significantly exceeding 20 years, making both mechanisms indispensable elements of a comprehensive exclusivity strategy.

The comparison between these two primary mechanisms is summarized below:

| Comparison of Patent Term Extension (PTE) vs. Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) |

| Feature |

| Governing Statute |

| Purpose |

| Maximum Term |

| Effective Life Limit |

| Applicability |

Section 3: The Parallel Barrier: Regulatory Exclusivities Granted by the FDA

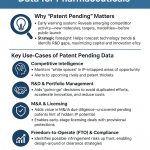

Regulatory exclusivities are distinct market monopolies granted by the FDA that operate independently of patent rights. These exclusivities prohibit the FDA from approving certain competitive applications for a set period, thereby forming a regulatory barrier that runs concurrently with any patent protection.5

3.1. New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: The 5-Year Wall

New Chemical Entity exclusivity is granted for a duration of five years.5 It is triggered by the approval of a drug that contains an active moiety never before approved by the FDA in any other application.13 Generally, a salt of an approved drug is not considered a new active moiety and is ineligible for this protection. However, NCE exclusivity applies to fixed-combination products where at least one active moiety is new, or where both active moieties have not been previously approved.13

The NCE period creates a hard bar: during the five-year term, no applicant may submit an ANDA or 505(b)(2) application seeking regulatory approval of a drug product containing the same active moiety.13 This acts as a powerful deterrent to competition during the critical initial years of commercialization.

NCE-1: The Litigation Trigger

A crucial exception, known as the NCE -1 date, dictates that if there are patents listed in the Orange Book under the NDA, a generic applicant can submit an ANDA or 505(b)(2) application with a Paragraph IV certification one year early, at the 4-year mark.13 The NCE-1 date is the point where the regulatory barrier immediately converts into a legal challenge. Although the generic cannot be approved until the full five years expire, filing the Paragraph IV certification in Year 4 initiates the 45-day window for the brand manufacturer to file an infringement lawsuit. This action automatically triggers a 30-month stay on the FDA’s ability to approve the generic application.7 Therefore, NCE exclusivity provides, in practical terms, only four years of commercial certainty before mandatory, high-stakes Hatch-Waxman litigation commences.

3.2. Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): 7 Years of Protection

Orphan Drug Exclusivity provides a robust seven-year market monopoly for drugs designated to treat rare diseases or conditions.5 Due to its longer duration compared to NCE exclusivity (7 years vs. 5 years), ODE often represents the single most valuable regulatory barrier, particularly if the foundational chemical patent is already close to expiration or if the drug is approved solely for the orphan indication.

3.3. Other Key Exclusivity Types and Additive Measures

Several other exclusivity types are available under the Hatch-Waxman framework:

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity (NCI): This grants three years of exclusivity for approval of an improvement, such as a new formulation, a new dosage form, or a new indication, provided that the approval required new clinical studies to demonstrate safety and efficacy.3 This mechanism is fundamental for sophisticated late-stage lifecycle management, allowing innovators to secure additional protection even as the original patent ages.

- Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Exclusivity: This adds an additional five years to existing exclusivities for qualified infectious disease products.5

- 180-Day Market Exclusivity: This exclusivity is granted to the first generic applicant to file a Paragraph IV certification, serving as a primary incentive for generics to challenge brand patents quickly.5

3.4. Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): The Six-Month Extension Multiplier

Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) is a highly valuable, short-term extension mechanism that provides an additional six months added to all existing patents and regulatory exclusivities listed in the Orange Book.5 To qualify, the innovator must voluntarily conduct studies in children according to an FDA-approved protocol. Because this six-month extension is added to every layer of protection—from the compound patent to formulation patents and regulatory exclusivities—it can generate enormous returns on investment, potentially adding billions of dollars in monopoly revenue.

A summary of primary U.S. regulatory exclusivities is provided below:

| U.S. Regulatory Exclusivities and Duration |

| Exclusivity Type |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) |

| New Clinical Investigation (NCI) |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) |

| 180-Day Market Exclusivity (PC/CGT) |

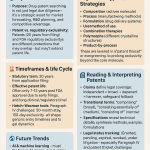

Section 4: Strategic Maximization of Market Monopoly

To achieve effective market exclusivity that approaches the desired 14-year post-approval lifespan, pharmaceutical companies employ sophisticated IP strategies focused on portfolio maximization, often leveraging multiple, overlapping protections far beyond the scope of the original compound patent.

4.1. Building the Fortress: Secondary Patents and Lifecycle Management

The initial foundational patent covering the new chemical entity is often the first patent to expire. Innovators, therefore, focus on developing and prosecuting a portfolio of secondary patents that cover incremental developments in the drug lifecycle. These patents may include new formulations, specific dosage regimens, crystalline structures (polymorphs), methods of use for new indications, or controlled-release technologies.4

The strategic importance of secondary patents is undeniable. A comprehensive study of top-selling branded drugs revealed that 91% of drugs that successfully obtained Patent Term Extensions subsequently maintained their monopolies well beyond the expiration of those extensions by relying on secondary patents.4 This phenomenon illustrates that although Hatch-Waxman limits PTE to one specific term restoration, its underlying mechanism is rendered incomplete if the innovator successfully places a series of later-expiring secondary patents in the Orange Book. This practice structurally enables innovators to circumvent the intended terminal date established by the PTE mechanism.

4.2. The Controversial Strategy of Patent Thickets

The accumulation of numerous secondary patents around a single drug product often results in a legal barrier known as a “patent thicket.” This strategy involves filing a large, dense, and often overlapping set of intellectual property rights.14

The primary function of the patent thicket is not necessarily to secure genuinely novel innovation for every filing, but to increase the difficulty, cost, and time required for generic manufacturers to enter the market. Generic companies attempting to utilize the ANDA pathway are required to certify against every patent listed in the Orange Book. A dense thicket forces the generic competitor to challenge dozens of patents simultaneously, driving up litigation costs and increasing the risk of injunctions or prolonged court battles.4 This practice is frequently referred to as “patent gamesmanship” and is perceived as exploiting loopholes in the current patent system to delay competition.15

The extensive reliance on secondary patents and thickets to extend monopolies confirms a significant economic consequence of the Hatch-Waxman framework’s operational complexity. While the Act was intended to facilitate faster generic access, the cost of these extended protections secured by strategic IP maneuvers is conservatively estimated to be $53.6 billion to the healthcare system, demonstrating that the current market reality often contradicts the Act’s original public policy objective.4 In response to this perceived abuse, lawmakers have introduced bipartisan legislation, such as the Eliminating Thickets to Increase Competition (ETHIC) Act, designed to place “reasonable limits” on the number of patents an innovator can assert, ensuring that new patents cover “real innovation” and add value to patients, rather than simply delaying competition.14

4.3. Stacking Patent Term Extensions (PTEs) and Exclusivities

Although the PTE statute limits the extension to one patent per approved drug product, sophisticated legal interpretation and regulatory timing allow innovators to effectively stack multiple extensions for a single active moiety by leveraging the distinct regulatory review periods associated with combination products.

Case Study: The Nesina® Triple-PTE Strategy

The 2016 approval of the alogliptin family of products represents a landmark case in PTE maximization. The innovator simultaneously obtained same-day approvals for three distinct New Drug Applications (NDAs): the monotherapy drug, Nesina® (alogliptin); and two fixed-dose combination products, Kazano® (alogliptin with metformin) and Oseni® (alogliptin with pioglitazone).16

The critical legal maneuver here was the determination that each NDA constituted a separate “product” eligible for its own regulatory review period (RRP). Because each product had a different regulatory history—even though they shared the same core molecule—the innovator was able to secure an unprecedented three separate PTE grants.16 This strategic execution allowed the innovator to extend three different patents, each tied to one of the three same-day approvals. The same strategy was employed for Lyrica® (pregabalin), where two different indications were approved on the same day, resulting in two corresponding PTEs.16

This success story demonstrates that maximizing market exclusivity requires the seamless integration of Regulatory Affairs and IP Counsel. The precise timing of NDA submissions, particularly for combination products, must be coordinated with patent expiry dates to exploit the statutory interpretation that an NDA approval, even for a related or fixed-combination product, establishes a distinct “regulatory review period” eligible for a separate PTE calculation. This strategy allows innovators to strategically bypass the explicit statutory limitation of “one extension per drug” when narrowly interpreted against the legal definition of an NDA.

Section 5: Global IP Frameworks: The Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC)

The challenges of pre-market development time are not unique to the United States. In the European Union (EU), the corresponding corrective mechanism to restore lost patent time is the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC).17

5.1. Overview of the European Union’s SPC System

The SPC is a sui generis industrial property right that extends the protection of a basic patent for a medicinal or plant protection product.18 Its objective is to compensate the patent holder for the significant period elapsed between the date the patent application was filed and the date of the first Marketing Authorisation (MA) in the European Economic Area (EEA).17

5.2. SPC Term Calculation and Limitations

The term of the SPC is calculated based on the delay incurred, utilizing a specific formula:

$$ \text{SPC Term} = (\text{Date of } 1\text{st MA in the EEA}) – (\text{Date of filing of corresponding patent}) – 5 \text{ years} $$ 18

The SPC system enforces strict limitations, similar to the U.S. PTE system:

- Maximum Term: An SPC can extend the patent right for a maximum duration of five years.17

- Floor Condition: If less than five years have elapsed between the filing date of the patent and the date of the first MA, no SPC term is granted.18

- Ceiling Condition: If the MA is issued more than ten years after the patent filing date, the SPC is automatically granted for the full five-year term.18

5.3. The Paediatric Extension in the EU

Mirroring the U.S. Pediatric Exclusivity, the EU provides a six-month additional extension to the SPC term.17 This extension is granted if the SPC relates to a medicine for children for which clinical data has been submitted in accordance with an agreed Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP).17 PIPs ensure that sufficient data is collected on the medicine’s effects on children, and the extension compensates the manufacturer for the associated additional clinical trials and testing.17

The addition of the paediatric extension means the maximum term of an SPC can reach 5.5 years. Consequently, the maximum duration of market exclusivity (patent term plus SPC) can reach up to at least 15.5 years in the EU.18 This extended exclusivity period closely mirrors the 14-year effective term rule set by the U.S. PTE system, confirming a global policy consensus that innovators should generally receive 14 to 15 years of post-approval exclusivity to recoup their investments.

Section 6: Commercial and Financial Implications of Patent Duration

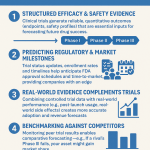

The exhaustive analysis of patent duration confirms that the true value of a pharmaceutical asset lies in the certainty and duration of its Effective Market Exclusivity (EME).

6.1. Quantifying the Risk: Navigating the Projected Patent Cliff

Accurate determination of the Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date is arguably the most critical variable in the strategic planning and valuation of pharmaceutical assets.1 The current forecast of a massive $236 billion patent cliff between 2025 and 2030 highlights the catastrophic financial risk associated with failing to defend or extend IP rights adequately.8 Any miscalculation of the final LOE date, even by a few months, can expose an asset prematurely to generic competition, resulting in valuation errors measured in hundreds of millions or billions of dollars.

The financial erosion following LOE is rapid and substantial. For small-molecule drugs, the market transforms swiftly, with innovators losing 90% of their market share within months as generic competitors introduce substantially lower-priced alternatives.8 While biosimilar competition is initially less aggressive for biologics, resulting in a 30% to 70% decline in the first year, the long-term price erosion remains a major threat.8

6.2. Strategic Requirements for LOE Mitigation

The strategic imperative for innovators is to transition seamlessly from dependency on the primary compound patent to reliance on robust secondary IP and regulatory exclusivities.

Strategic lifecycle management requires the aggressive pursuit of New Clinical Investigation (NCI) exclusivity by developing improved versions, new formulations, or new indications that require new clinical studies well in advance of the primary patent expiration.3 This provides an additional three-year regulatory buffer. Furthermore, the mandatory requirement of pediatric studies for the highly advantageous 6-month Pediatric Exclusivity should be treated not as a regulatory burden but as an essential IP investment.5

Finally, the success demonstrated by case studies achieving multiple PTEs for a single active moiety underscores a key organizational requirement: The maximization of market exclusivity hinges on a non-negotiable integration between the Regulatory Affairs team (which manages the timing of IND and NDA/BLA submissions, vital for PTE and exclusivity triggers) and the IP Counsel (which manages patent prosecution and litigation). Strategic coordination of these submissions is the mechanism by which sophisticated innovators exploit statutory definitions—such as the definition of a “drug product” or “regulatory review period”—to secure stacking opportunities that extend the monopoly beyond the literal intent of the one-PTE rule.16

Conclusions and Recommendations

The effective market exclusivity for a pharmaceutical product is a meticulously constructed legal and regulatory edifice, bearing little resemblance to the nominal 20-year patent term. The actual duration is dictated by the precise interaction of Patent Term Extension (PTE), Patent Term Adjustment (PTA), and a hierarchy of FDA regulatory exclusivities.

Nuanced Conclusions

- Hatch-Waxman’s Double Edge: While the Hatch-Waxman Act successfully expedited generic market entry, the compensatory mechanisms (PTE and exclusivities) have been strategically leveraged by innovators, resulting in monopoly periods that routinely extend well beyond the intended 14-year effective term through the aggressive use of secondary patents. This strategic reliance on patent thickets, despite attracting legislative scrutiny, often renders the expiration of the original PTE meaningless in determining the final LOE date.4

- The Supremacy of Regulatory Timing: The most successful strategies for monopoly maximization, exemplified by the Nesina case, rely not only on strong patents but on the precise regulatory timing of NDA submissions, especially for combination products.16 This regulatory gamesmanship allows innovators to stack PTEs and maximize the concurrent running of regulatory exclusivities (NCE, ODE, NCI).

- The Financial Imperative: Given the scale of the impending Patent Cliff, IP strategy must be recognized as a core financial and business development function. The legal mandate is not merely to prosecute patents, but to manage the entire portfolio risk profile against a dynamically calculated and heavily defended LOE date.1

Actionable Recommendations

For pharmaceutical innovators seeking to maximize their duration of market exclusivity, the following strategies are required:

- Establish Integrated IP-Regulatory Planning: Implement unified teams responsible for coordinating NDA/BLA filings, pediatric study submissions, and patent prosecution to maximize opportunities for stacking PTEs and securing the 6-month Pediatric Exclusivity.5

- Prioritize Defensive IP: Focus secondary patent filing efforts on unique and defensible aspects (e.g., novel crystalline forms, specific indications) that can withstand Paragraph IV challenges, rather than relying on volume (patent thickets) alone, which increasingly invites political and legislative pushback.14

- Global Harmonization: Ensure that US PTE/PED strategies are synchronized with applications for the European SPC and Paediatric Extension to secure parallel, maximal global market exclusivity, achieving up to 15.5 years post-approval exclusivity in key jurisdictions.18

Works cited

- Maximizing Pharmaceutical Patent Longevity: A Mechanistic and Strategic Guide to IP Term Extension and Lifecycle Fortification – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- How Long Does a Patent Last for Drugs? A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Duration – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-does-a-patent-last-for-drugs/

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: What is the Hatch-Waxman Act? | PhRMA, accessed November 13, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-what-is-the-hatch-waxman-act

- Patent Term Extensions and the Last Man Standing | Yale Law & Policy Review, accessed November 13, 2025, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/patent-term-extensions-and-last-man-standing

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- Effective patent life in pharmaceuticals – Henry G. Grabowski and John M. Vernon – DukeSpace, accessed November 13, 2025, https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/bitstreams/c36aa185-8049-40cc-bf59-7d72e0892a6c/download

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed November 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- 5 Steps to Take When Your Drug Patent is About to Expire, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/5-steps-to-take-when-your-drug-patent-is-about-to-expire/

- 2020 Patent Prosecution Tool Kit: Patent Term Extension – Sterne Kessler, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/patent-term-extension/

- Introduction to Patent Term Extensions (PTE) – Fish & Richardson, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/ip-law-essentials/intro-patent-term-extension/

- Patent Term Adjustment Data September 2025 – USPTO, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/dashboard/patents/patent-term-adjustment-new.html

- Appendix E: Description of the Patent Term Adjustment Data Release – USPTO, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Appendix%20E.pdf

- Exclusivity–Which one is for me? | FDA, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/135234/download

- Cornyn, Blumenthal Introduce Bill to Lower Drug Costs by Preventing Patent System Abuse, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.cornyn.senate.gov/news/cornyn-blumenthal-introduce-bill-to-lower-drug-costs-by-preventing-patent-system-abuse/

- Arrington Introduces ETHIC Act to Increase Competition in the Prescription Drug Market, accessed November 13, 2025, https://arrington.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=2738

- The Art of the Second Act: A Strategic Guide to Obtaining Multiple Patent Term Extensions for a Single Product – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-obtain-multiple-patent-term-extensions-for-a-single-product/

- Supplementary protection certificates for pharmaceutical and plant protection products – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, accessed November 13, 2025, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/strategy/intellectual-property/patent-protection-eu/supplementary-protection-certificates-pharmaceutical-and-plant-protection-products_en

- Supplementary protection certificate – Wikipedia, accessed November 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supplementary_protection_certificate