Part I: The New Frontier of IP Strategy: From Reactive Defense to Predictive Offense

The journey from a promising molecule to a market-approved therapy is a marathon fraught with peril. It is a decathlon of scientific rigor, regulatory navigation, and, above all, staggering financial investment. Yet, lurking beneath the more visible hurdles of clinical trial failures and market access challenges is a more fundamental risk, one that can invalidate a decade of work and billions of dollars in an instant: the risk of unpatentability. For too long, intellectual property strategy has been a reactive discipline, a legal backstop engaged late in the development cycle. But what if you could see the future? What if you could predict, with a high degree of data-driven certainty, whether a new compound would survive the gauntlet of patent examination before committing the lion’s share of your R&D budget? This is no longer science fiction. The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and vast, digitized patent datasets is ushering in a new era of predictive IP strategy, transforming a legal necessity into a powerful engine of competitive advantage.

The Strategic Imperative: Why Predict Patentability?

The pharmaceutical industry operates on a scale of risk and reward that is almost unparalleled. The average cost to develop a single new prescription drug now stands at a breathtaking $2.6 billion, a figure that accounts for the immense cost of the many candidates that fail along the way.1 This journey is not only expensive but also agonizingly long, typically spanning 10 to 15 years from initial discovery to market approval.1 The odds are daunting; a mere 12% of drugs that enter the first phase of clinical trials will ultimately receive the nod from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Other estimates place the failure rate for drugs entering clinical trials even higher, at nearly 90%.

In this environment, what justifies such a monumental gamble? The answer is the patent. The 20-year period of market exclusivity granted by a utility patent is the foundational pillar of the innovator business model.4 It is the sole mechanism that allows a company to recoup its colossal R&D investment and, critically, to fund the next wave of innovation. Without it, a newly launched, life-saving drug could be easily and cheaply replicated by generic competitors who bore none of the initial discovery costs but are poised to capture the profits.

Historically, the critical assessment of a compound’s patentability has been a milestone reached relatively late in the preclinical stage, often after hundreds of millions of dollars and several years have already been invested. This traditional approach positions IP as a reactive, defensive function. The paradigm is now shifting. The strategic imperative is to move this assessment upstream, to the very earliest stages of discovery and lead optimization. By leveraging AI to analyze patent data, companies can now forecast patentability, transforming IP from a legal checkpoint into a proactive, strategic tool for de-risking the entire R&D pipeline. In an industry where a single patent dispute can swing a company’s valuation by billions, the ability to forecast these outcomes becomes as vital as the R&D investment itself. A “go/no-go” decision, informed by an early and accurate patentability prediction, can prevent a catastrophic misallocation of resources, saving a company from investing further in a compound doomed to fail not in the clinic, but in the patent office.

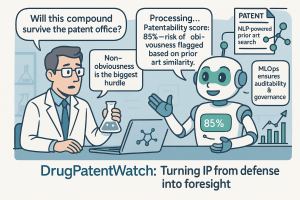

This shift in thinking allows for the reframing of “patentability” itself. It ceases to be a binary legal question of “yes” or “no” and becomes a continuous, quantifiable financial risk score. Pharmaceutical companies are, at their core, portfolio managers, balancing a collection of high-risk, high-reward assets. Each project in the R&D pipeline is evaluated based on its probability of clinical success, its potential market size, and other commercial factors. The ultimate net present value (NPV) of any of these projects, however, is fundamentally contingent on securing market exclusivity through a patent. The probability of obtaining that patent is therefore a direct and critical input into the financial modeling of that asset. Where this probability was once a qualitative, “gut-feel” assessment by patent attorneys, AI now provides the means to make it quantitative, data-driven, and systematic. By generating a “patentability score”—for instance, an 85% probability of overcoming non-obviousness challenges based on an analysis of all known prior art—a company can more accurately model a project’s expected return on investment (ROI). This allows for more rational capital allocation across the entire portfolio, elevating the IP function from a necessary cost center to a core driver of value creation and strategic decision-making.

Deconstructing the Patentability Gauntlet: A Business-Focused Primer

To build a system that predicts patentability, one must first understand the criteria it seeks to predict. In the United States and Europe, the two largest pharmaceutical markets, the core requirements for a utility patent are conceptually similar, though their application can differ significantly.4 These criteria are the gatekeepers of the patent system, ensuring that only genuine, substantive innovations are granted the powerful right of market exclusivity.

The three pillars of patentability are:

- Utility / Industrial Applicability: This is generally the most straightforward requirement to meet in the pharmaceutical context. The invention must have a “useful” purpose. For a new chemical compound, this means it must have a credible, specific, and substantial utility, such as treating a particular disease or modulating a biological target. A hypothetical or trivial use is not sufficient; the patent application must articulate a real-world benefit.

- Novelty: The invention must be new. This is a strict requirement. An invention is considered “anticipated” and thus not novel if every single one of its claimed elements is disclosed in a single piece of prior art—be it a previously published patent, a scientific journal article, a public presentation, or any other public disclosure.9 The European Patent Office (EPO) adheres to a standard of “absolute novelty,” meaning any public disclosure anywhere in the world before the filing date can be novelty-destroying. Crucially, Europe offers no grace period for an inventor’s own disclosures, making the timing of the first patent filing a critical strategic decision.12 The U.S. provides a limited one-year grace period for disclosures made by the inventor, but relying on this is often a risky strategy in a global market.

- Non-Obviousness (U.S. § 103) / Inventive Step (EPC Art. 56): This is, without question, the highest and most subjective hurdle to clear. An invention can be novel—meaning it’s not identically disclosed in the prior art—but still be denied a patent if the differences between it and the prior art are such that the invention as a whole would have been “obvious” at the time it was made to a “Person Having Ordinary Skill in The Art” (PHOSITA).6 This requirement prevents the patenting of trivial advancements that are merely predictable combinations or modifications of known elements. It is the primary battleground where the majority of patent applications are rejected and where the most intense legal arguments take place.

In the U.S., the framework for determining obviousness is guided by the Supreme Court’s decision in Graham v. John Deere Co., which established three key factual inquiries: (A) determining the scope and content of the prior art; (B) ascertaining the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art; and (C) resolving the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art. For years, the courts applied a relatively rigid “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” (TSM) test, which required the prior art to contain an explicit suggestion to make the claimed combination. However, the landmark 2007 Supreme Court case KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc. dramatically reshaped this landscape.15 The

KSR decision rejected the rigid TSM test in favor of a more flexible, expansive, and common-sense-based approach. It affirmed that an invention could be obvious if it was “obvious to try”—for instance, by choosing from a finite number of identified, predictable solutions with a reasonable expectation of success. This shift made the non-obviousness determination far more unpredictable and subjective, creating a perfect environment for data-driven AI models to find patterns that humans might miss.

The challenge is amplified for chemical compounds, where small structural modifications can lead to unpredictable changes in biological activity. The EPO, for instance, has specific and evolving case law around “selection inventions,” where a patent is sought for a specific compound or a narrow sub-range that falls within a broader, previously disclosed genus of compounds. In such cases, establishing an inventive step often requires demonstrating an “unexpected technical effect”—such as surprisingly higher potency or lower toxicity—compared to the compounds in the prior art.14 This is precisely the kind of evidence that AI models can help uncover by predicting properties and comparing them against known data.

The very tools being developed to predict patentability are also poised to change the standard itself. The legal concept of non-obviousness is judged through the eyes of the PHOSITA, a hypothetical expert who is presumed to have access to all relevant prior art and a level of ordinary creativity. As AI tools for target identification, molecule design, and literature analysis become ubiquitous in the pharmaceutical industry—with over 90% of companies now investing in AI for drug discovery —it is inevitable that the legal definition of “ordinary skill” will evolve to include proficiency with these tools. The hypothetical PHOSITA of tomorrow will be an AI-augmented PHOSITA.

This has profound strategic implications. A new molecule that could be generated with relative ease by a standard AI model, given a known biological target and access to public chemical databases, might be deemed “obvious to try” and therefore unpatentable.16 In this future landscape, securing a patent will require more than just novelty; it will demand a demonstration of human ingenuity that goes

beyond what a standard AI could predictably generate. A predictive patentability system, therefore, becomes more than just a tool for assessing the existing prior art. It becomes an essential strategic guide, steering R&D efforts away from crowded, “AI-obvious” chemical spaces and toward territories that are truly inventive and legally defensible. It is a necessary instrument for staying ahead of a constantly rising bar for innovation.

Part II: The Digital Blueprint of Innovation: Unlocking Patent Data

The predictive power of any AI system is born from the data it consumes. For predicting patentability, the raw material is the global corpus of patent documents and scientific literature—a digital blueprint of human innovation stretching back centuries. To build an effective model, one must first learn to see these documents not as static legal texts, but as rich, multimodal datasets waiting to be unlocked.

Anatomy of a Pharmaceutical Patent: Data Beyond the Text

A patent is a complex document, a hybrid of dense legal language and detailed scientific disclosure. Each of its components represents a different type of data, requiring specialized tools for extraction and analysis. A successful AI strategy must appreciate this multimodal nature.

- The Specification: The Scientific Disclosure: This is the technical core of the patent. It must contain a “written description” of the invention that is detailed enough to prove the inventor was in “possession” of what is claimed, and an “enablement” disclosure that teaches a PHOSITA how to make and use the invention without “undue experimentation”.12 Recent landmark court decisions, most notably

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, have dramatically raised the standards for enablement, particularly for broad claims covering a genus of molecules. The Supreme Court affirmed that the specification must enable the full scope of what is claimed, not just provide a few examples and a “roadmap” for further research. This makes the specification a critical data source, not just for understanding the invention, but for assessing the very strength and validity of the patent itself. - The Claims: The Legal Fences: The claims are the legally operative part of the patent, defining the precise boundaries of the intellectual property. Each claim is a single, meticulously crafted sentence, typically broken down into three parts:

- The Preamble: Defines the class of the invention (e.g., “A pharmaceutical composition…”).

- The Transitional Phrase: A critical term that defines the claim’s breadth. “Comprising” is open-ended, meaning the invention can include other, unlisted elements. “Consisting of” is closed-ended, meaning the invention includes only the listed elements. This choice has massive implications for infringement and is a key data point for analysis.

- The Body: Lists the essential elements of the invention.

Different types of claims represent distinct data structures that must be parsed accordingly. Composition of matter claims are the “gold standard,” protecting the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. These can be narrow “species claims” for a single compound or broad “genus claims” that use a Markush structure to define an entire family of related molecules with variable chemical groups. Method of use claims protect new applications for compounds, vital for drug repurposing strategies , while formulation and dosage claims are crucial secondary patents that can extend a drug’s market exclusivity by protecting the final commercial product. - Prior Art: The Known Universe: The list of citations in a patent is merely the starting point. The true “prior art” is the entire global universe of knowledge publicly available before the patent’s filing date. This includes all patents, published patent applications, scientific journal articles, conference presentations, and even doctoral theses.15 For an AI system, this represents a vast, interconnected graph of knowledge that must be navigated to determine if a new invention is truly novel and non-obvious.

A failure to recognize the multimodal nature of this data is a primary reason why simple text-based AI approaches are insufficient. A patent is not a flat text file. It is a semi-structured document containing legal language (claims), scientific prose (specification), structured chemical data (Markush formulas, IUPAC names, SMILES strings), graphical data (2D chemical drawings), and relational data (citation networks, inventor histories). An effective AI system cannot simply “read” a patent; it must deploy a suite of specialized models. It needs Natural Language Processing (NLP) to parse the legal nuances of the claims, computer vision and optical character recognition (OCR) to extract structures from drawings , and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to interpret the topology of the resulting chemical graphs. This integrated, multimodal approach is the core technical challenge and the key to building a truly insightful predictive system.

Building the Foundation: Data Acquisition and Pipelines

With a clear understanding of the data types involved, the next step is to build a robust and scalable pipeline to acquire, process, and manage this information. The quality of this foundation will directly determine the reliability of the final predictions.

- Public Data Sources: The world’s major patent offices provide bulk access to their data, forming the bedrock of any analysis. Key sources include the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Bulk Data files, the European Patent Office’s (EPO) Worldwide Patent Statistical Database (PATSTAT), and the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO) PATENTSCOPE database.22 These are complemented by specialized public databases focused on medicines, such as WIPO’s Pat-INFORMED, which provides patent status information directly from pharmaceutical companies, and the Medicines Patent Pool’s MedsPaL database.28

- Commercial Data Providers: While public sources are comprehensive, their raw data is often messy and difficult to work with. Commercial data providers add immense value by cleaning, harmonizing, and enriching this data. Platforms such as DrugPatentWatch are invaluable, as they don’t just provide patent text; they curate and link it to critical contextual information, including Orange Book listings, patent litigation outcomes, clinical trial data, and patent expiration forecasts.6 This enriched data provides a 360-degree view of a drug’s IP landscape. Other services from companies like LexisNexis , IPD Analytics , and InQuartik perform the laborious but essential tasks of correcting misspelled assignee names, standardizing formats, and disambiguating entities (e.g., linking patents filed by various subsidiaries back to a single parent corporation).

- The Data Pipeline Architecture: A production-grade data pipeline for patent analysis involves several key stages, often orchestrated on a cloud platform like Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Google Cloud for scalability 34:

- Ingestion: Automated scripts regularly pull the latest data releases from patent offices and commercial feeds.

- Parsing and Structuring: Raw data formats, typically XML, are parsed to extract and separate distinct fields—claims, specification, inventors, assignees, dates, etc.—into a structured database.

- Cleaning and Harmonization: This is the critical “janitorial” work. Algorithms, often supplemented by human experts, correct errors, standardize names and addresses, and resolve ambiguities. This process, known as entity disambiguation, is a core value proposition of commercial data providers and is essential for accuracy.27

- Storage: The cleaned and structured data is stored in a scalable data warehouse or data lake, ready for querying and use by machine learning models.

The importance of this foundational data work cannot be overstated. The old adage of “garbage in, garbage out” is acutely true for AI systems. Raw patent office data is notoriously “dirty”. A model trained on this raw data will learn incorrect patterns and produce flawed predictions. For example, it might fail to identify a crucial prior art patent simply because the inventor’s name was misspelled in the original filing, leading to a dangerously false assessment of a new compound’s novelty. This would be a catastrophic failure. Therefore, the investment in high-quality, curated data and a robust data cleaning pipeline is not an optional expense; it is the single most critical determinant of a predictive patentability system’s success and reliability. A company must either commit to building this complex data engineering capability in-house or partner with a specialized provider who has already mastered it. To do otherwise is to build a powerful engine on a foundation of sand, resulting in a system that produces predictions that are fast, confident, and dangerously wrong.

Part III: The AI Toolkit for Patent Intelligence

Once a clean, structured, and multimodal patent dataset has been established, the next stage is to deploy a specialized arsenal of AI tools to extract meaning from it. No single AI model can master the complexity of patent data. A successful system requires a symphony of different technologies, each tailored to a specific task: one to understand the language, another to see the molecules, and a final one to synthesize these signals into a coherent prediction.

Decoding the Language of Patents with Natural Language Processing (NLP)

The bulk of a patent is text, but it is a unique and challenging dialect of legalese and dense scientific terminology. Natural Language Processing (NLP) provides the tools to translate this complex language into machine-readable insights.

The journey begins by moving beyond primitive keyword searching. A simple keyword search for “kinase inhibitor” might miss a critical prior art document that uses the synonym “protein kinase antagonist” or describes the mechanism of action without using the exact phrase. This is where semantic search becomes transformative. Powered by deep learning, semantic search models don’t just match words; they understand the underlying concepts and context. This allows them to find relevant documents even when the terminology differs, dramatically improving the comprehensiveness of a prior art search.

At the heart of modern NLP are Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs), most famously the BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) architecture and its many successors.37 These models are “pre-trained” on billions of sentences from the internet and vast book corpora, allowing them to develop a deep, contextual understanding of language. For the highly specialized domain of patents and science, even more powerful variants have emerged. Models like

SciBERT, which is pre-trained specifically on a massive corpus of scientific publications, demonstrate superior performance on technical documents compared to general-purpose models like the original BERT.

In the context of predicting patentability, these powerful NLP models are applied in several key ways:

- Automated Prior Art Search: This is the most direct application. An R&D team can input a description of a new compound, a biological target, or even a draft patent claim. The NLP model then converts this query into a high-dimensional vector and searches the database for patents and scientific articles with the most similar vectors. This process can scan millions of documents in seconds, surfacing a highly relevant list of potential prior art that would take a human researcher days or weeks to compile.25

- Patent Classification: The international patent system uses complex hierarchical classification codes like the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) to organize inventions. NLP models can be trained to automatically assign these codes to new patent applications with high accuracy, helping to rapidly narrow the search for prior art to the most relevant technical domains.38

- Claim Analysis: The legal scope of a patent is defined by its claims. NLP models can be used to parse the intricate grammar and legal terminology of claims, identifying the key elements and limitations of the invention. This structured output can then be systematically compared against features extracted from prior art documents to flag potential novelty or obviousness issues.

Seeing the Molecules: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in Cheminformatics

While NLP models are masters of text, they are blind to the most important piece of information in a pharmaceutical patent: the chemical structure of the molecule itself. A molecule is not a string of characters; it is a graph, with atoms as the nodes and chemical bonds as the edges. Its biological properties are a direct function of this 3D topology. Treating a molecule as a simple text string, like its SMILES representation, fundamentally misunderstands its nature and loses the rich structural information that determines its function.

This is where Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) become indispensable. GNNs are a class of deep learning models designed specifically to work with graph-structured data.24 They operate on a principle often analogized to “message passing.” In each layer of the network, every atom (node) sends “messages” containing information about itself to its immediate neighbors along the bonds (edges). It then receives messages from its neighbors and uses this aggregated information to update its own state or representation. By repeating this process over several layers, each atom builds up a sophisticated understanding of its local and, eventually, global chemical environment within the molecule.

For predicting patentability, GNNs offer several unique and powerful capabilities that are impossible for text-based models:

- Quantitative Structural Similarity Assessment: A GNN can take a molecule as input and output a fixed-length vector, known as a “learned embedding,” that numerically represents its structure. To assess obviousness, the system can generate embeddings for both the new drug candidate and a structurally related compound from the prior art. The mathematical distance (e.g., cosine similarity) between these two vectors provides a powerful, objective measure of their structural similarity.23 This moves the analysis from a qualitative human judgment to a quantifiable metric.

- Markush Structure Analysis: A major challenge in patent analysis is dealing with Markush claims, which can define a genus of millions or even billions of potential compounds. GNNs can be adapted to process these complex chemical spaces, for example, by sampling representative molecules from the genus and analyzing their properties, thereby helping to determine if a new compound is likely to fall within the scope of a prior art Markush claim.

- Prediction of “Unexpected Technical Effects”: As discussed, a key strategy for overcoming an obviousness rejection, particularly at the EPO, is to show that a new compound possesses an unexpected beneficial property compared to the prior art. GNNs can be trained on large datasets of molecules and their measured biological activities to become powerful property predictors. A GNN could, for instance, predict the binding affinity of a new compound for its target protein. If this predicted affinity is significantly higher than that of a structurally similar prior art compound, it provides strong, data-driven evidence to support an argument for inventive step.45

The Prediction Engine: Machine Learning Models for Patentability Scoring

The NLP and GNN models serve as sophisticated feature extractors. They transform raw, unstructured patent data into a set of meaningful, numerical features: semantic similarity scores from the text, structural similarity scores from the GNNs, predicted chemical properties, and so on. The final step is to feed this rich feature set into a predictive model that learns the complex relationships between these features and the ultimate outcome of patent examination.

This is a classic supervised machine learning task: the model is trained on a historical dataset of patent applications, where the features are the extracted data points and the “label” is the known outcome (e.g., granted, or rejected for obviousness). The goal is for the model to learn a function that can take the features of a new, unseen compound and predict its likely outcome.

Several types of models can be used for this final classification step, each with its own trade-offs between performance and interpretability.

Table: Comparison of Machine Learning Models for Patentability Prediction

| Model Family | Primary Task in Patentability Prediction | Key Characteristics | Interpretability | Data Requirements | Pros | Cons |

| Traditional ML (SVM, Random Forest) | Final patentability classification; Baseline for prior art search. | Uses engineered features (e.g., TF-IDF, molecular fingerprints). Strong performance on structured data. | Medium-High | Moderate | Highly interpretable (especially Random Forest); computationally efficient; robust with smaller datasets. | Relies heavily on quality of feature engineering; may not capture complex non-linear patterns. |

| Transformers (BERT, SciBERT) | Prior art search; Text analysis of claims & specification; Feature extraction from text. | Contextual understanding of language; pre-trained on massive corpora. | Low | Very Large | State-of-the-art performance on NLP tasks; captures semantic nuance; less feature engineering needed. | Computationally expensive to train/fine-tune; can be a “black box”; requires significant data. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Chemical structure analysis; Structural similarity scoring; Property prediction. | Learns directly from molecular graph structure; “message passing” architecture. | Low-Medium | Large | Captures topological information missed by other models; state-of-the-art for molecular tasks. | Can be complex to implement; interpretability is an active area of research; performance depends on graph quality. |

| Ensemble Methods (XGBoost, ExtraTrees) | Final patentability classification, often outperforming single models. | Combines predictions from multiple weaker models to create a strong predictor. | Low | Moderate-Large | Typically highest predictive accuracy; robust to overfitting; handles mixed data types well. | Can be computationally intensive; less interpretable than single models like Random Forest. |

The final output of this entire system is not a definitive “yes” or “no.” Instead, it is a probability score—for example, “This compound has a 75% probability of being deemed non-obvious over the known prior art.” This single, powerful number encapsulates the analysis of millions of data points and becomes the quantitative risk metric that can be integrated directly into the strategic portfolio management and R&D decision-making processes discussed in Part I. It transforms ambiguity into actionable intelligence.

Part IV: Building the Predictive Patentability System

With the conceptual framework and the AI toolkit defined, the focus shifts to the practical engineering challenge of building, training, and operationalizing a predictive patentability system. This is a sophisticated data science endeavor that requires meticulous attention to detail at every stage, from preparing the raw data to deploying the final models in a scalable and governable manner.

From Raw Data to Actionable Features: The Art of Preprocessing and Engineering

Before any machine learning model can work its magic, the raw data from the pipelines must be transformed into a clean, numerical format that the algorithms can understand. This process of preprocessing and feature engineering is often the most time-consuming part of an ML project, but it is absolutely critical for model performance.

For the textual components of patents, the preprocessing pipeline involves several standard but essential steps.48 First is

tokenization, the process of breaking down long passages of text into individual words or sub-word units (tokens). This is followed by lowercasing all text to ensure consistency. Then, stop word removal eliminates common, low-information words like “the,” “is,” and “a,” which add noise without adding meaning. Finally, stemming or lemmatization reduces words to their root form (e.g., “treating,” “treated,” and “treats” all become “treat”) to consolidate their semantic meaning. Beyond these basics, patent-specific noise removal is crucial, which involves stripping out recurring legal boilerplate, headers, and other formatting artifacts that are irrelevant to the technical content.49

Once the text is clean, it must be converted into numerical vectors. While foundational methods like Bag-of-Words (BoW) or TF-IDF exist, they are limited as they treat words as independent units.51 A more powerful approach is the use of

word embeddings. Techniques like Word2Vec and GloVe learn a dense vector representation for each word from a large corpus, where the geometry of the vector space captures semantic relationships. For instance, in this space, the vector for “king” minus the vector for “man” plus the vector for “woman” results in a vector very close to that of “queen”.51 This ability to capture meaning is the precursor to the even more advanced contextual embeddings generated by transformer models like BERT, which represent the current state-of-the-art.

For the molecular data, a similar feature engineering process is required. The most common method is the creation of molecular fingerprints. These are bit vectors where each bit corresponds to the presence (1) or absence (0) of a specific chemical substructure or pattern within the molecule. Popular fingerprinting algorithms include MACCS keys, which check for a predefined list of 166 structural features, and Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs), also known as Morgan fingerprints, which systematically encode the circular neighborhood around each atom.54 These fingerprints provide a simple and computationally efficient way to convert a complex molecule into a fixed-length numerical vector that can be fed into traditional machine learning models. However, as with word embeddings, the more powerful approach is to use a GNN to learn a molecular representation directly from the graph structure. These

GNN embeddings are not based on predefined rules but are learned representations that capture the holistic topology of the molecule, often outperforming hand-crafted fingerprints on complex predictive tasks.57

Training, Validating, and Deploying the Models

With the data transformed into engineered features, the process of training the predictive models can begin. This is a supervised learning problem, which means it requires a large dataset of historical examples where the correct outcome is already known. Creating this dataset is a significant undertaking, involving the collection of thousands of past patent applications which are then meticulously labeled with their final examination outcomes (e.g., “granted,” “rejected under §103,” “abandoned”).

The labeled dataset is then typically split into three parts: a training set (usually ~70-80% of the data) used to teach the model the patterns, a validation set (~10-15%) used to tune the model’s hyperparameters and prevent it from “overfitting” (memorizing the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns), and a test set (~10-15%) that is held back and used only once at the very end to provide an unbiased evaluation of the final model’s performance.

The performance of the models is measured using a set of standard evaluation metrics. For the final classification task (patentable vs. unpatentable), key metrics include Precision (of the patents predicted to be granted, what fraction actually were?), Recall (of all the patents that were actually granted, what fraction did the model correctly identify?), and the F1-Score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. For the prior art retrieval task, which returns a ranked list of documents, metrics like Mean Average Precision (MAP) and Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG) are used, as they evaluate not only whether relevant documents were found but also whether they were ranked highly in the results list.61

Training these sophisticated models on datasets containing millions of patents is a computationally intensive task that is impractical for on-premise servers. This is where cloud computing becomes essential. Major cloud providers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure offer the on-demand, scalable infrastructure needed for large-scale machine learning. They provide access to powerful hardware like GPUs and TPUs, which can accelerate model training by orders of magnitude, and offer managed AI/ML platforms (e.g., Amazon SageMaker, Google’s Vertex AI) that simplify the process of building, training, and deploying models at scale.34 Pfizer, for example, leverages AI on AWS to achieve the global scale necessary for its R&D and clinical trial operations.34

Operationalizing Intelligence with MLOps

Developing a successful prototype model is a significant achievement, but it is only the beginning. To deliver sustained business value, the model must be deployed into a production environment and maintained over time. The landscape of science and patent law is not static; new prior art is published daily, and legal standards evolve. A model trained today will see its performance degrade over time if it is not continuously updated. This is the challenge that MLOps (Machine Learning Operations) is designed to solve.66

MLOps is a set of practices that combines machine learning, data engineering, and DevOps to automate and manage the end-to-end lifecycle of an ML model. It provides the framework to move from a one-off, manually managed model to a robust, automated, and continuously improving production system. For a pharmaceutical company, a mature MLOps framework includes several key components 69:

- Automation: The entire pipeline, from new data ingestion and preprocessing to model training, validation, and deployment, is automated. This ensures consistency, repeatability, and scalability.66

- Version Control: This is perhaps the most critical principle. MLOps mandates rigorous versioning of not just the model’s code, but also the dataset it was trained on and the resulting model artifact itself. This creates a complete, auditable lineage for every prediction the system makes.

- Continuous Monitoring: Once deployed, the model’s performance is continuously monitored in real-time. This includes tracking for “model drift,” a phenomenon where the model’s predictive accuracy degrades as the real-world data it sees in production begins to differ from the data it was trained on. When drift is detected, an alert can automatically trigger a retraining of the model on the latest data.70

- Governance and Compliance: MLOps establishes a structured process for model review, validation, and approval before deployment. This ensures that models are fair, unbiased, and compliant with the stringent regulatory and data privacy requirements of the pharmaceutical industry.66

In the highly regulated pharmaceutical world, MLOps transcends being a mere technical best practice for efficiency. It becomes a critical framework for ensuring regulatory compliance and building defensible, auditable AI systems. The decisions informed by a patentability prediction model can be worth billions of dollars—for example, the decision to terminate a promising drug program due to a low patentability score. If this decision is ever challenged, whether by internal auditors, regulators, or in shareholder litigation, a company must be able to provide a complete and transparent account of why the AI made its prediction. A manually managed model offers no such defense. In contrast, a mature MLOps framework provides an immutable audit trail. It can prove exactly which version of the code, running on which version of the data, produced which version of the model that made the critical prediction on a specific date. This transforms the AI from an opaque and potentially risky tool into a governed, transparent, and legally defensible component of the corporate decision-making apparatus.

Part V: From Prediction to Profit: Integrating AI into Business Strategy

Building a technically sophisticated predictive patentability system is a formidable achievement. However, its true value is only realized when it is seamlessly integrated into the strategic fabric of the organization. The system’s output—a probability score and a list of prior art—is not an answer, but a question. It is a powerful new input that must be interpreted by human experts and used to drive smarter, faster, and more profitable R&D decisions. This requires a new kind of collaboration, a symbiotic partnership between human intellect and machine intelligence.

Interpreting the Output: The Human-in-the-Loop Imperative

A common misconception about AI is that it is an autonomous decision-maker. In high-stakes domains like law and science, this could not be further from the truth. The most effective AI systems function not as autopilots, but as incredibly powerful co-pilots, augmenting the capabilities of human experts rather than replacing them.73 An AI-generated patentability score should never be taken as an infallible verdict. It is a highly informed starting point for a deeper, human-led analysis.

The optimal workflow is a human-in-the-loop (HITL) process that leverages the best of both worlds: the speed and scale of the machine, and the nuance and judgment of the human expert.75 This collaborative cycle typically unfolds in three stages:

- AI’s First Pass: The process begins with the AI system performing the heavy lifting. It scans millions of patents and scientific articles, analyzes thousands of chemical structures, and in minutes, surfaces the 10 or 20 most relevant prior art references from a universe of possibilities. It synthesizes this information into a preliminary patentability score, flagging the key risks.

- Expert Review and Refinement: This is where human expertise becomes irreplaceable. A team, typically comprising a patent attorney and a medicinal chemist, takes the AI’s output as their starting point. The chemist uses their deep domain knowledge to assess the technical relevance of the cited art and the scientific feasibility of any proposed combinations. The patent attorney applies their understanding of legal doctrine to interpret the scope of prior art claims, assess the subtleties of obviousness arguments, and consider jurisdiction-specific nuances that an AI might miss. They validate the AI’s findings, reject false positives, and may use their intuition to uncover related art the algorithm overlooked.

- Iterative Feedback Loop: The process does not end with the expert review. The conclusions of the human experts are fed back into the system. By marking certain AI-surfaced documents as “highly relevant” and others as “irrelevant,” they provide new labeled data that is used to continuously retrain and improve the underlying models. This creates a virtuous cycle where the AI gets progressively smarter and more aligned with the specific needs and context of the organization over time.

This symbiotic approach is essential because, for all their power, AI models still struggle with the uniquely human aspects of patent law. The art of claim construction, the subjective assessment of what a PHOSITA would have found obvious, and the strategic anticipation of a patent examiner’s arguments all require a level of contextual judgment and creative reasoning that is currently beyond the reach of any algorithm.

Beyond the Black Box: The Role of Explainable AI (XAI) in Legal Tech

One of the most significant barriers to the adoption of AI in legal and other high-stakes fields is the “black box” problem.77 The most powerful deep learning models are often the least transparent. A neural network might predict with 95% accuracy that a patent claim will be rejected, but it cannot easily articulate

why it reached that conclusion.79 This opacity is unacceptable when billion-dollar decisions hang in the balance. A lawyer cannot confidently advise a client to abandon a research program based on a computer’s inscrutable pronouncement.

This is the challenge that Explainable AI (XAI) is designed to address. XAI is not a single technology but a collection of methods and techniques aimed at making the decisions of AI models understandable and interpretable to human users.81 In the context of a patentability prediction system, XAI can be implemented in several ways:

- Feature Importance: Techniques like LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) or SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) can be applied to a model’s prediction to reveal which input features had the most influence on the outcome.83 For example, the XAI layer could report: “The model assigned a high risk of obviousness primarily because of the structural similarity to compound X in patent Y, specifically the presence of a pyridine ring at the R1 position.” This transforms an opaque score into an actionable insight.

- Example-Based Explanations: The system can provide visual explanations. When flagging a structural similarity risk, it could display the two molecules side-by-side and highlight the specific substructures that the GNN identified as being most similar, allowing a chemist to immediately grasp the basis for the AI’s concern.

- Building Trust and Accountability: Ultimately, XAI is about building trust. When legal and scientific professionals can understand the reasoning behind an AI’s recommendation, they can critically evaluate it, identify potential flaws in its logic, and confidently incorporate it into their own decision-making process. It provides the necessary transparency to ensure the model is not relying on spurious correlations or hidden biases in the data, making the entire system more robust and accountable.

Case Studies and ROI: Quantifying the Impact

The theoretical benefits of AI in pharmaceutical R&D are now being validated by a growing number of real-world applications and compelling financial metrics.

Companies at the forefront of this wave are demonstrating transformative results. Insilico Medicine, a prominent AI-driven drug discovery company, famously used its platform to progress a novel drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from initial target identification to a preclinical candidate in just 18 months—a process that traditionally takes five to six years.18 This is not an isolated case. AI is also proving to be a powerful tool for drug repurposing.

BenevolentAI used its knowledge graph platform to analyze vast amounts of biomedical data and identify Baricitinib, an existing rheumatoid arthritis drug, as a potential treatment for COVID-19, a finding that was later validated and led to FDA approval.86 On the IP operations side, specialized AI software is enabling pharmaceutical firms to slash the time required for comprehensive patent research from months to mere days.

These case studies translate into a powerful return on investment (ROI) that can be quantified across several dimensions:

- Direct Cost Reductions: AI-powered platforms can reduce the direct costs of R&D by up to 40%. This is achieved by improving the efficiency of preclinical research, reducing the number of failed experiments, and, most importantly, enabling the early termination of projects focused on compounds that a predictive patentability system flags as high-risk. This avoids the massive downstream costs of advancing an unprotectable asset.

- Accelerated Timelines and Increased Revenue: AI has the potential to cut drug discovery timelines by as much as 50%. Getting a drug to market years earlier has a twofold financial benefit: it starts generating revenue sooner, and it extends the effective patent life on the market before generic competition begins, maximizing the total return from the asset.

- Improved R&D Productivity and Portfolio Value: By systematically weeding out projects with a low probability of securing patent protection, companies can focus their finite resources—scientists, lab capacity, and capital—on assets with the highest probability of both clinical and commercial success. This improves the overall productivity and expected ROI of the entire R&D portfolio.7 In one documented instance, early patent intelligence that flagged a competitor’s activity saved a company an estimated $100 million in what would have been wasted development costs.

The market itself is voting with its dollars, providing the ultimate validation of this technology’s value. The global market for AI in drug discovery is projected to explode from approximately $1.5 billion today to nearly $13 billion by 2032, reflecting a massive wave of investment and industry-wide adoption. This is not a niche experiment; it is a fundamental reshaping of the pharmaceutical innovation landscape.

Part VI: Navigating the Future: Challenges and Ethical Horizons

The adoption of any transformative technology is accompanied by new challenges and ethical considerations. As pharmaceutical companies integrate predictive AI into the core of their IP and R&D strategies, they must navigate a complex landscape of inherent risks, from biased data to the evolving legal definitions of inventorship. Proactively addressing these issues is not just a matter of compliance; it is essential for building sustainable, trustworthy, and effective AI-powered innovation engines.

Addressing Inherent Risks: Bias, Confidentiality, and Legal Evolution

While AI offers immense promise, it also presents significant risks that must be managed with vigilance.

- Data Bias: Machine learning models are a reflection of the data they are trained on. If the training data contains biases, the model will learn and amplify them.90 Patent datasets are not immune to this. They can be skewed towards certain technology classes, geographical regions, or the filings of large, established corporations.91 An AI model trained on such data might, for example, underestimate the novelty of an invention from an emerging field or a smaller company simply because it has seen fewer similar examples. Mitigating this requires a conscious effort to build balanced and representative training datasets and to use XAI tools to audit models for biased decision-making patterns.

- Confidentiality and Data Security: This is a non-negotiable, paramount concern for any company dealing with pre-publication intellectual property. Using public, third-party AI tools for patentability analysis is fraught with peril. Submitting an invention disclosure or a novel chemical structure to a service like the public version of ChatGPT could be interpreted as a public disclosure, an act that would instantly destroy the novelty of the invention worldwide. Furthermore, it represents a grave breach of client confidentiality and data security, as the data could be used to train the provider’s model and potentially be exposed to other users. The only responsible approach is to use AI models that are deployed in a secure, private environment, whether on-premise or within a virtual private cloud (VPC), where the company maintains absolute control over its data.

- The Evolving Legal Landscape of AI: The law is still racing to catch up with the pace of AI development. A critical area of uncertainty is the concept of inventorship. Globally, the legal consensus, solidified by landmark cases like the Thaler v. Vidal decision in the U.S., is that an “inventor” must be a human being.85 An invention generated solely by an AI system is not currently patentable. However, the USPTO issued crucial guidance in 2024 clarifying that an invention is patentable if one or more humans made a “significant contribution” to its conception.18 For drug discovery, this means it is absolutely critical for companies to meticulously document the human involvement in the AI-assisted discovery process. This includes records of how scientists designed the AI model, curated the training data, interpreted the AI’s outputs to select promising candidates, and conducted the lab experiments to validate the results. This documentation is the key evidence needed to prove human inventorship and secure a valid patent.

The Future of the AI-Augmented IP Professional

The rise of predictive AI will not make patent attorneys, IP analysts, or R&D strategists obsolete. Instead, it will profoundly transform their roles, automating routine, labor-intensive tasks and elevating their focus to higher-value strategic work. The AI-augmented IP professional of the near future will require a new blend of legal, scientific, and data literacy.

Their value will shift from manual document discovery and review to more sophisticated functions :

- Strategic Prompt Engineering: The quality of an AI’s output is highly dependent on the quality of the input query. Professionals will become experts at crafting nuanced, sophisticated prompts that guide the AI to the most relevant information and analyses.

- Critical Output Validation: As the “human in the loop,” their primary role will be to apply their deep legal and scientific judgment to interpret, validate, and contextualize the AI’s results, separating the signal from the noise and identifying the subtleties the machine missed.

- Proactive Strategic Counsel: Armed with predictive insights, their role will become more forward-looking. They will advise R&D teams not just on whether a current compound is patentable, but on how to proactively “invent around” AI-identified prior art. They will use the AI’s landscape analysis to identify “white spaces”—areas of therapeutic need with low patent congestion—and guide research toward these more promising and defensible territories.

At the same time, the increasing accessibility of powerful AI-driven search tools will likely democratize patent intelligence. Smaller biotech companies and even individual inventors will have access to prior art analysis capabilities that were once the exclusive domain of large corporate legal departments. This could lead to an overall increase in the quality and rigor of patent applications filed across the industry.

Industry Insight

In conclusion, the future of pharmaceutical IP is not one of human experts being replaced by machines. It is a future of powerful symbiosis. The AI will provide the scale, speed, and data-processing power to illuminate the vast landscape of prior art. The human expert will provide the wisdom, judgment, and strategic creativity to navigate that landscape and chart a course to true innovation. The pharmaceutical companies that master this collaboration—fusing machine intelligence with human intellect—will not only de-risk their R&D pipelines and optimize their IP portfolios; they will be the ones to discover, protect, and deliver the next generation of life-saving medicines.

Key Takeaways

- Shift from Reactive to Predictive IP: Leveraging AI to forecast patentability early in the R&D cycle transforms intellectual property from a defensive legal function into a proactive strategic tool for de-risking multi-billion dollar investments.

- Patentability as a Quantifiable Financial Risk: AI models can generate a “patentability score,” allowing companies to integrate IP risk directly into portfolio management and NPV calculations, leading to more rational capital allocation.

- Non-Obviousness is the Main Battlefield: While novelty and utility are critical, the subjective and high bar of non-obviousness is the primary hurdle for pharmaceutical patents. AI is uniquely suited to analyze the vast prior art landscape to assess this risk.

- A Hybrid AI Toolkit is Essential: Predicting patentability requires a multimodal AI approach. Natural Language Processing (NLP) models like BERT are needed to analyze text, while Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are essential for interpreting and comparing chemical structures.

- Data Quality is Paramount: The maxim “garbage in, garbage out” is critically important. The accuracy of any predictive system depends entirely on the quality of the underlying patent data. Investing in clean, curated, and harmonized data from sources like DrugPatentWatch is a non-negotiable prerequisite for success.

- The Human-in-the-Loop is Irreplaceable: AI is a powerful co-pilot, not an autopilot. The optimal workflow combines the speed and scale of AI for initial analysis with the nuanced judgment of patent attorneys and scientists for validation, interpretation, and strategic decision-making.

- MLOps Provides a Framework for Governance: Implementing Machine Learning Operations (MLOps) is crucial for automating, managing, and monitoring predictive models at scale, ensuring reproducibility, and providing the auditability required in a regulated industry.

- The Bar for Inventive Step is Rising: As AI becomes a standard tool in drug discovery, the legal standard for what is considered “obvious” will likely rise. Future patentable inventions will need to demonstrate ingenuity that surpasses what a standard AI could predictably generate.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can an AI system truly predict a legal outcome like a patent grant, which involves subjective human judgment from a patent examiner?

An AI system cannot predict a legal outcome with absolute certainty, as human judgment, legal interpretation, and negotiation are always involved. However, it can provide a highly accurate probabilistic forecast. The system works by learning patterns from hundreds of thousands of past patent applications and their outcomes. It identifies features in the invention’s description, claims, and chemical structure that have historically correlated with success or failure in overcoming rejections, particularly for non-obviousness. The output is best understood not as a definitive “yes/no” answer, but as a data-driven risk assessment—for example, “There is an 85% probability that this compound will be considered non-obvious based on existing prior art.” This quantitative insight is an incredibly powerful tool to augment, not replace, the strategic advice of experienced patent counsel.

2. How do Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) handle the complexity of Markush structures in prior art patents, which can represent billions of compounds?

This is an advanced application and an active area of research. A direct, exhaustive comparison is computationally infeasible. Instead, GNN-based systems use several clever strategies. One approach is “negative sampling,” where the model learns to distinguish the new candidate molecule from a large, representative sample of molecules that are known to be inside the Markush structure’s scope. Another method involves breaking down the Markush structure into its core scaffold and its variable “R-groups.” The GNN can then learn embeddings for the scaffold and for each possible R-group, allowing it to assess whether the new compound’s structure is a plausible combination of the prior art’s building blocks. This provides a robust method for estimating whether a new molecule is likely to be covered by a broad genus claim without having to enumerate every possibility.

3. If we use an AI to predict patentability, does that create a risk that our own invention could be deemed “obvious” because an AI helped guide the research?

This is a sophisticated and forward-looking question. Currently, the use of AI as a tool in the inventive process does not, by itself, render an invention obvious. The legal standard of non-obviousness is assessed against the publicly available prior art from the perspective of a PHOSITA. However, as AI tools become ubiquitous in the industry, the baseline capabilities of the hypothetical PHOSITA will inevitably rise. An invention that is a simple, predictable output of a standard, widely available AI model might indeed face a stronger obviousness challenge in the future. The key to patentability will be demonstrating significant human contribution and ingenuity beyond the routine application of the AI tool—for example, by using the AI’s output in a non-obvious way, by solving a problem the AI was not designed for, or by showing an unexpected result that the AI itself did not predict.18 Meticulous documentation of this human intellectual contribution is therefore essential.

4. What is the single biggest mistake a company can make when implementing a predictive patentability system?

The single biggest mistake is underestimating the importance of data quality and curation. Many organizations are seduced by the power of the algorithms (the “model”) but fail to recognize that the model’s performance is entirely capped by the quality of the data it’s trained on. Raw patent data from public sources is notoriously inconsistent and error-prone, with misspelled names, ambiguous entities, and fragmented ownership information. Building a system on this “dirty” data will lead to a model that is confidently incorrect, which is far more dangerous than no model at all. The most successful implementations recognize that 80% of the work is in the unglamorous tasks of data engineering: building robust pipelines, cleaning and harmonizing data, and performing rigorous entity disambiguation. This foundational work is the true driver of reliable and trustworthy predictions.

5. How does Explainable AI (XAI) work in practice for a patent attorney reviewing a model’s output?

In practice, XAI provides a crucial layer of transparency on top of the model’s prediction. Instead of just seeing a score like “72% risk of §103 rejection,” the attorney would see an interactive dashboard that explains the score. For example, it might list the top three prior art references contributing to the risk, with the specific passages highlighted by the NLP model. For a structural risk, it might show a 2D alignment of the candidate molecule and a prior art molecule, with the GNN highlighting the specific substructures it found most alarmingly similar. The XAI system could also use techniques like SHAP to show that, for instance, “50% of the risk score comes from Patent A, 30% from the predicted low binding affinity, and 20% from a key term in the claim language.” This allows the attorney to immediately focus their expert analysis on the most critical issues, validate the AI’s reasoning, and build a much more targeted and effective prosecution or R&D strategy.81

References

- The Cost of Drug Development: How Much Does It Take to Bring a Drug to Market? (Latest Data) | PatentPC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/the-cost-of-drug-development-how-much-does-it-take-to-bring-a-drug-to-market-latest-data

- AI in Drug Discovery: How AI Is Accelerating Pharma Research (Key Stats) | PatentPC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/ai-in-drug-discovery-how-ai-is-accelerating-pharma-research-key-stats

- Patents and Drug Pricing: Why Weakening Patent Protection Is Not in the Public’s Best Interest – American Bar Association, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/2025-spring/drug-pricing-weakening-patent-protection-not-best-interest/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary Magazine, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- Patent Defense Isn’t a Legal Problem. It’s a Strategy Problem. Patent Defense Tactics That Every Pharma Company Needs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-defense-isnt-a-legal-problem-its-a-strategy-problem-patent-defense-tactics-that-every-pharma-company-needs/

- 5 Ways to Predict Patent Litigation Outcomes – DrugPatentWatch …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/5-ways-to-predict-patent-litigation-outcomes/

- Maximizing ROI on Drug Development by Monitoring Competitive Patent Portfolios, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/maximizing-roi-on-drug-development-by-monitoring-competitive-patent-portfolios/

- AI-Powered Portfolio Management in Pharmaceuticals – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/ai-powered-portfolio-management-in-pharmaceuticals/

- Novelty and Non-Obviousness: How to Define a Patentable Invention, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.dbllawyers.com/how-to-define-a-patentable-invention/

- Patentability Meaning: An Easy Guide to Essential Requirements – The Rapacke Law Group, accessed August 8, 2025, https://arapackelaw.com/patents/patentability-meaning/

- Is it patentable? | epo.org, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/new-to-patents/is-it-patentable

- Drafting Detailed Drug Patent Claims: The Art and Science of …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drafting-detailed-drug-patent-claims-the-art-and-science-of-pharmaceutical-ip-protection/

- Patent Requirements – BitLaw, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.bitlaw.com/patent/requirements.html

- Patentability of known substances in Europe – Marks & Clerk, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.marks-clerk.com/insights/latest-insights/102ju8n-patentability-of-known-substances-in-europe/

- Patentability of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients – PLI, accessed August 8, 2025, https://legacy.pli.edu/emktg/toolbox/patpharm_ing36.doc

- 2141-Examination Guidelines for Determining Obviousness Under …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2141.html

- Selection inventions before the EPO – Mewburn Ellis, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.mewburn.com/news-insights/selection-inventions-before-the-epo

- Patenting Drugs Developed with Artificial Intelligence: Navigating the Legal Landscape, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patenting-drugs-developed-with-artificial-intelligence-navigating-the-legal-landscape/

- 2163-Guidelines for the Examination of Patent Applications Under the 35 U.S.C. 112(a) or Pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, first paragraph, “Written Description” Requirement – USPTO, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2163.html

- Medical Procedures & Pharma Patents In The US – TT Consultants, accessed August 8, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/medical-procedures-pharma-patents-in-the-us/

- 2182-Search and Identification of the Prior Art – USPTO, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2182.html

- Prior Art Search in Chemistry Patents based on Semantic Concepts and Co-Citation Analysis – Text REtrieval Conference, accessed August 8, 2025, https://trec.nist.gov/pubs/trec19/papers/fraunhofer-scai.chem.rev.pdf

- [2308.12234] MolGrapher: Graph-based Visual Recognition of Chemical Structures – arXiv, accessed August 8, 2025, https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.12234

- [2209.05582] Graph Neural Networks for Molecules – arXiv, accessed August 8, 2025, https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.05582

- Free AI Patent Search Tool – Powerful, Instant Results – Founders Legal, accessed August 8, 2025, https://founderslegal.com/pqai-free-patent-search/

- PATSTAT | epo.org – European Patent Office, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/searching-for-patents/business/patstat

- PatentsView Data Pipeline, accessed August 8, 2025, https://patentsview.org/data-pipeline

- Pat-INFORMED – The Gateway to Medicine Patent Information – WIPO, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/pat-informed/en/

- MedsPal | Medicines Patents, & Licences Database | MPP, accessed August 8, 2025, https://medicinespatentpool.org/what-we-do/medspal

- Strategic Imperatives: Leveraging Patent Pending Data for Competitive Advantage in the Pharmaceutical Industry – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-patent-pending-data-for-pharmaceuticals/

- Patent Data Quality | LexisNexis Intellectual Property Solutions, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.lexisnexisip.com/solutions/quality-patent-data/

- IPD Analytics | The Industry Leader in Drug Life-Cycle Insights, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ipdanalytics.com/

- Patent Data: Best Datasets & Databases 2025 – Datarade, accessed August 8, 2025, https://datarade.ai/data-categories/patent-data

- Cloud Computing Solutions for Life Sciences – AWS, accessed August 8, 2025, https://aws.amazon.com/health/life-sciences/

- Exploring the Role of Cloud Computing in the Pharmaceutical Industry – Avahi, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.avahitech.com/blog/cloud-computing-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- How is AI Solving the Biggest Headaches in Prior Art Search? – XLSCOUT, accessed August 8, 2025, https://xlscout.ai/how-is-ai-solving-the-biggest-headaches-in-prior-art-search/

- A Survey on Patent Analysis: From NLP to … – ACL Anthology, accessed August 8, 2025, https://aclanthology.org/2025.acl-long.419.pdf

- A Comprehensive Survey on AI-based Methods for Patents – arXiv, accessed August 8, 2025, https://arxiv.org/html/2404.08668v1

- Supplementing USPTO Prior Art Searches with AI Tools – DEV Community, accessed August 8, 2025, https://dev.to/patentscanai/supplementing-uspto-prior-art-searches-with-ai-tools-1jd9

- Research on patent classification technology based on deep learning – Consensus, accessed August 8, 2025, https://consensus.app/papers/research-on-patent-classification-technology-based-on-fei-zhang/6cfe7bfefc4b554594ad6eb6dbbc6e1f/

- Integrating concept of pharmacophore with graph neural networks for chemical property prediction and interpretation – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9351086/

- [PDF] Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/81fee2fd4bc007fda9a1b1d81e4de66ded867215

- Graph neural networks for molecular and materials representation – OAE Publishing Inc., accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.oaepublish.com/articles/jmi.2023.10

- Intelligent System for Automated Molecular Patent Infringement Assessment – arXiv, accessed August 8, 2025, https://arxiv.org/html/2412.07819v2

- Tutorial at the 39th Annual AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2025) – Graph Neural Networks, accessed August 8, 2025, https://gnn.seas.upenn.edu/aaai-2025/

- Graph Neural Networks as a Potential Tool in Improving Virtual Screening Programs – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8811035/

- accessed December 31, 1969, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9362097/

- Machine Learning for Text Analysis – Saiwa, accessed August 8, 2025, https://saiwa.ai/blog/machine-learning-for-text-analysis/

- Text Preprocessing for Machine Learning & NLP – Kavita Ganesan, PhD, accessed August 8, 2025, https://kavita-ganesan.com/text-preprocessing-tutorial/

- US20220342583A1 – Methods and apparatus for data preprocessing – Google Patents, accessed August 8, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US20220342583A1/en

- NLP 101: Feature Engineering and Word Embeddings – SheCanCode, accessed August 8, 2025, https://shecancode.io/nlp-101-feature-engineering-and-word-embeddings/

- A Hierarchical Feature Extraction Model for Multi-Label Mechanical Patent Classification – Scholar Commons, accessed August 8, 2025, https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1263&context=csce_facpub

- A comparative analysis of embedding models for patent similarity – arXiv, accessed August 8, 2025, https://arxiv.org/html/2403.16630v1

- Representation of Molecular Fingerprints with Python and RDKit for AI Models, accessed August 8, 2025, https://zoehlerbz.medium.com/representation-of-molecular-fingerprints-with-python-and-rdkit-for-ai-models-8b146bcf3230

- Virtual Screening of Molecules via Neural Fingerprint-based Deep Learning Technique, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11100899/

- Deep kernel learning improves molecular fingerprint prediction from tandem mass spectra | Bioinformatics | Oxford Academic, accessed August 8, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/article/38/Supplement_1/i342/6617526

- Molecular Graph Representation Learning and Generation for Drug Discovery – DSpace@MIT, accessed August 8, 2025, https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/143362

- Learning Molecular Representations for Medicinal Chemistry – ACS Publications, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00385

- Validation in Innovation Data – iiindex, accessed August 8, 2025, https://iiindex.org/guides/validation/

- Evaluation measures (information retrieval) – Wikipedia, accessed August 8, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evaluation_measures_(information_retrieval)

- The aRt of RAG Part 4: Retrieval evaluation | by Ross Ashman (PhD) | Medium, accessed August 8, 2025, https://medium.com/@rossashman/the-art-of-rag-part-4-retrieval-evaluation-427bb5db0475

- A new metric for patent retrieval evaluation – SciSpace, accessed August 8, 2025, https://scispace.com/pdf/a-new-metric-for-patent-retrieval-evaluation-5097ichfoe.pdf

- Google Cloud for Healthcare and Life Sciences, accessed August 8, 2025, https://cloud.google.com/solutions/healthcare-life-sciences

- intuitionlabs.ai, accessed August 8, 2025, https://intuitionlabs.ai/articles/google-cloud-gcp-in-pharma-industry#:~:text=Google%20Cloud’s%20prowess%20in%20machine,quantum%20chemistry%20simulations%20on%20TPUs.

- Data and AI are Helping to Get Medicines to Patients Faster – Pfizer, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/sites/default/files/investors/financial_reports/annual_reports/2022/story/data-and-ai-are-helping-to-get-medicines-to-patients-faster/

- What is MLOps? – Machine Learning Operations Explained – AWS, accessed August 8, 2025, https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/mlops/

- What is MLOps? – IBM, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/mlops

- LLMOps vs MLOps: Key differences, use cases, and success stories – N-iX, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.n-ix.com/llmops-vs-mlops/

- Revolutionizing Pharma: MLOps, AI, & Data Synergy for Commercial Ops, accessed August 8, 2025, https://insights.axtria.com/articles/beyond-boundaries-reshaping-pharmas-commercial-horizon-with-mlops

- MLOps in Life Sciences: Ensuring Compliance & Driving Performance – v4c.ai, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.v4c.ai/blog/mlops-in-life-sciences-ensuring-compliance-driving-performance

- What is an MLOps Framework and 8 Steps to Build Your Own – Control Plane, accessed August 8, 2025, https://controlplane.com/community-blog/post/what-is-an-mlops-framework

- MLOps Use Cases: 10 Real-World Examples & Applications – Citrusbug Technolabs, accessed August 8, 2025, https://citrusbug.com/blog/mlops-use-cases/

- The Future of Patent Intelligence Tools: How AI is Revolutionizing the Landscape, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-future-of-patent-intelligence-tools-how-ai-is-revolutionizing-the-landscape/

- AI Patent Searching and the Importance of Keeping a Human-in-the-Loop | MaxVal, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.maxval.com/blog/ai-patent-searching-and-the-importance-of-keeping-a-human-in-the-loop/

- AI and Human-in-the-Loop for Prior Art Search – Lumenci, accessed August 8, 2025, https://lumenci.com/blogs/ai-human-in-the-loop-prior-art-search/

- Artificial Intelligence For Patent Prior Art Searching – ML4Patents, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ml4patents.com/blog-posts/artificial-intelligence-for-patent-prior-art-searching

- What Is Black Box AI and How Does It Work? – IBM, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/black-box-ai

- Addressing the Black Box Problem in Legal Generative AI – World Lawyers Forum, accessed August 8, 2025, https://worldlawyersforum.org/news/addressing-the-black-box-problem-in-legal-generative-ai/

- AI’s mysterious ‘black box’ problem, explained | University of Michigan-Dearborn, accessed August 8, 2025, https://umdearborn.edu/news/ais-mysterious-black-box-problem-explained

- Black box algorithms and the rights of individuals: no easy solution to the “explainability” problem | Internet Policy Review, accessed August 8, 2025, https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/black-box-algorithms-and-rights-individuals-no-easy-solution-explainability

- Explainable AI For Legal Systems – Meegle, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.meegle.com/en_us/topics/explainable-ai/explainable-ai-for-legal-systems

- Explainable AI in Law: A Comprehensive Guide – Number Analytics, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/explainable-ai-in-law-guide

- What is Explainable AI (XAI)? – IBM, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/explainable-ai

- INTERPRETING GRAPH NEURAL NETWORKS WITH MYERSON VALUES FOR CHEMINFORMATICS APPROACHES | ChemRxiv, accessed August 8, 2025, https://chemrxiv.org/engage/api-gateway/chemrxiv/assets/orp/resource/item/668c3885c9c6a5c07aaca81e/original/interpreting-graph-neural-networks-with-myerson-values-for-cheminformatics-approaches.pdf

- AI Meets Drug Discovery – But Who Gets the Patent? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/ai-meets-drug-discovery-but-who-gets-the-patent/

- Aligning AI Innovation with IP Strategy in Drug Discovery – Mathys & Squire LLP, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.mathys-squire.com/insights-and-events/news/aligning-ai-innovation-with-ip-strategy-in-drug-discovery/

- AI in Drug Discovery: Why IP Searches Are the Key to Securing Market Leadership – Evalueserve IP and R&D, accessed August 8, 2025, https://iprd.evalueserve.com/blog/ai-in-drug-discovery-why-ip-searches-are-the-key-to-securing-market-leadership/

- Patent Research Using AI – Case Study – Quy technology, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.quytech.com/case-study/ai-powered-patent-research.php

- AI in Pharma and Biotech: Market Trends 2025 and Beyond – Coherent Solutions, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.coherentsolutions.com/insights/artificial-intelligence-in-pharmaceuticals-and-biotechnology-current-trends-and-innovations

- IBM’s Patents on AI Bias Mitigation: Legal Implications for Developers | PatentPC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/ibms-patents-on-ai-bias-mitigation-legal-implications-for-developers

- The use and misuse of patent data: Issues for finance and beyond – Harvard Business School, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/The%20use%20of%20patent%20data%206.3.21_e6b7f575-10d8-4331-b0f4-b55fdf36834a.pdf

- Use and Misuse of Patent Data: Issues for Finance and Beyond | The Review of Financial Studies | Oxford Academic, accessed August 8, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article-abstract/35/6/2667/6324822

- US11636386B2 – Determining data representative of bias within a model – Google Patents, accessed August 8, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/US11636386/en

- The Ethics and Practicality of AI Assisted Patent Drafting, accessed August 8, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2023/08/31/ethics-practicality-ai-assisted-patent-drafting/id=166094/

- Emerging Legal Terrain: IP Risks from AI’s Role in Drug Discovery – Fenwick, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fenwick.com/insights/publications/emerging-legal-terrain-ip-risks-from-ais-role-in-drug-discovery

- How AI Is Transforming Patent Drafting: Insights from Leading European Attorneys, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.solveintelligence.com/blog/post/podcast-on-how-ai-is-transforming-patent-practice

- Insights – Marshall, Gerstein & Borun LLP, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.marshallip.com/insights/

- Understanding Patent Law in Your Industry – Schmeiser, Olsen & Watts, LLP, accessed August 8, 2025, https://iplawusa.com/understanding-patent-law-in-your-industry/