I. The Modern Pharmaceutical Crucible: Navigating the Economics of Erosion and Uncertainty

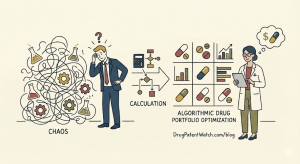

The pharmaceutical industry operates within a crucible of unprecedented complexity. For decades, the model of discovering, developing, and commercializing new medicines, while always challenging, followed a relatively predictable financial logic. Today, that logic has been fractured. Portfolio managers find themselves navigating a chaotic whirlwind of collapsing profit margins, a fragmented and labyrinthine global regulatory maze, geopolitically fragile supply chains, and disruptive government policies that rewrite the rules of market entry.1 The traditional, often heuristic-based methods of portfolio management, which have served the industry for over two decades, are proving increasingly inadequate in this new environment.2 To move from this state of chaos to one of strategic clarity, organizations must first understand the fundamental forces that define the modern pharmaceutical landscape: a brutal economic reality, the staggering statistical improbability of the research and development (R&D) process itself, and the subtle but powerful influence of human cognitive biases on high-stakes decisions.

1.1 Deconstructing the “Chaos”: The New Economic Reality

At the heart of the industry’s current predicament lies a brutal economic dynamic: the relentless and accelerating erosion of price and profit margins.1 This is not a cyclical downturn but a structural shift in the risk-reward calculus that underpins all portfolio decisions. The moment a generic drug enters the market, it triggers a precipitous race to the bottom that threatens the viability of producing many essential medicines.1

The value proposition of a generic drug is its affordability, delivered through competition. However, the intensity of this competition has created a pricing death spiral. The decline is not gradual; it is a cliff. Data consistently shows that the entry of a single generic competitor slashes the price of a drug by 30% to 39% compared to the brand price.1 With two competitors, the price falls by 54%, and with six or more generics in the market, the average manufacturer price collapses by a staggering 95%.1 This extreme level of price erosion means that for many mature products, particularly simple oral solids, margins become “razor-thin or non-existent,” making continued production economically unsustainable for all but the most scaled and cost-efficient manufacturers.1 This dynamic creates a vicious cycle: as prices plummet, manufacturers with higher overheads are forced to exit the market, which can, paradoxically, lead to drug shortages for essential, low-margin medicines.1

This pressure is compounded by the consolidated power of buyers. Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs), pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and large hospital networks wield immense negotiating leverage, demanding steep discounts and rebates that further compress margins.1 For a generic company, gaining access to a major GPO’s formulary is essential for achieving volume, but it comes at a significant cost, placing firms in a perpetually defensive position.1

Government policy has emerged as another powerful and disruptive force. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the United States, for instance, fundamentally alters the financial calculus for both brand and generic manufacturers. Its Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program allows the government to set a “Maximum Fair Price” (MFP) for certain high-cost drugs years before their patents expire.1 This transforms the traditional “patent cliff”—a sharp drop from a high brand price to a low generic price—into a “patent slope”.1 By negotiating the brand price down while it is still on patent, the IRA erodes the potential profit pool that generic entrants historically targeted. This introduces a profound new layer of uncertainty and may drive investment away from small-molecule drugs, which are eligible for negotiation nine years after approval, and toward biologics, which have a longer 13-year window.1

Finally, brand-name manufacturers employ sophisticated defense strategies to delay generic entry, adding legal and commercial hurdles. Tactics like “pay-for-delay” settlements, where a brand company compensates a generic manufacturer to delay its launch, and “product hopping,” where minor formulation changes are made to secure new patents and force patient switching, further complicate the landscape and increase the costs and risks for generic competitors.1 This confluence of intense price competition, buyer power, policy disruption, and brand defense strategies creates the chaotic external environment in which every portfolio decision must now be made.

1.2 The R&D Gauntlet: A Statistical Portrait of Cost, Time, and Failure

If the external commercial environment is a crucible, the internal R&D process is a gauntlet. The journey from a promising molecule in a lab to an approved medicine on a pharmacy shelf is one of the most expensive, lengthy, and failure-prone endeavors in any industry. Understanding the stark statistical realities of this process is fundamental to appreciating the need for advanced optimization.

The cost of developing a new drug is staggering. While estimates vary depending on methodology and the types of companies studied, the figures consistently point to a massive capital investment. A 2020 study estimated the median cost to bring a new drug to market was $985 million, with the average cost being $1.3 billion.4 Other analyses, particularly those from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development which focus on large pharmaceutical companies and include the cost of failed projects, have placed the average capitalized cost as high as $2.87 billion.4 It is crucial to distinguish between out-of-pocket cash expenses and capitalized costs. Capitalized cost, the standard accounting treatment for long-term investments, accounts for the time value of money over the decade-plus development cycle and the cost of failed projects. This figure, which can be more than double the out-of-pocket cost, represents the true economic burden of R&D.4

These immense costs are incurred over exceptionally long timelines. The average time to develop a new medicine from initial discovery through regulatory approval is 10 to 15 years.5 The clinical phase alone, which begins with first-in-human studies, lasts an average of around eight years and accounts for nearly 70% of total R&D expenditures.9 A more granular breakdown reveals the protracted nature of each stage: Phase I trials average 2.3 years, Phase II trials average 3.6 years, and the large, pivotal Phase III trials average 3.3 years, followed by another 1.3 years for regulatory submission and review.5 This long duration means that, on average, half of a drug’s 20-year patent life is consumed before it ever generates revenue, a delayed return on investment that would be unacceptable in nearly any other industry.5

The primary driver of both the high capitalized cost and the need for long timelines is the astronomical rate of failure. Drug development is a process of attrition, where the vast majority of candidates are eliminated along the way. The overall likelihood of approval (LOA) for a drug candidate entering Phase I clinical trials has steadily fallen and is now just 6.7%.11 This means that for every 100 drugs that begin human testing, fewer than seven will ever reach the market. Attrition rates are particularly brutal in the middle of the pipeline. While Phase I success rates (transitioning to Phase II) are around 47%, Phase II has the lowest success rate of any stage, with only about 28% of programs successfully completing it.11 This stage, often called the “valley of death,” is where many drugs fail to show sufficient efficacy, leading to the termination of the project after hundreds of millions of dollars have already been invested.12 Even for drugs that make it to the final, most expensive stage, success is not guaranteed, with Phase III success rates hovering around 55%.11 This unforgiving statistical reality means that the profits from the few successful drugs must cover the enormous costs of the many failures.4

Table 1: The Economics of Pharmaceutical R&D

| Development Stage | Average Timeline (Years) | Average Out-of-Pocket Cost per Successful Drug (USD Millions) | Average Capitalized Cost per Successful Drug (USD Billions) | Probability of Success (Phase Transition Rate) | Key Therapeutic Area Variations |

| Preclinical | 3–6 | ~$430 | ~$1.1 | 69% | Varies significantly by target novelty. |

| Phase I | ~2.3 | ~$48 | ~$0.1 | ~47% | Generally higher across TAs, focused on safety. |

| Phase II | ~3.6 | ~$86 | ~$0.2 | ~28% | Lowest success rates; Oncology and Neurology are particularly challenging. |

| Phase III | ~3.3 | ~$282 | ~$0.7 | ~55% | Most expensive phase; Neurology and Respiratory have lower success rates. |

| Submission to Launch | ~1.3 | ~$15 | ~$0.04 | ~92% | High success, but delays can occur. |

| Overall | 10–15 | ~$985 | ~$2.8 | ~6.7% | Oncology, Neurology, and Respiratory are among the most expensive and high-risk areas. |

Note: Costs and probabilities are synthesized estimates from multiple sources and represent industry averages, which can vary significantly by therapeutic area (TA), drug modality, and company. Capitalized costs include the cost of failures and the time value of money. Data synthesized from.4

1.3 The Human Factor: Cognitive Biases in High-Stakes Decision-Making

The chaotic external environment and the brutal internal statistics of R&D are challenging enough on their own. However, their effects are amplified by a third, often-overlooked factor: the fallibility of human decision-making. Pharmaceutical portfolio management is a process uniquely susceptible to cognitive biases, the systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment.16 In an industry defined by high uncertainty, sparse data (especially in early stages), and immense pressure to innovate, these psychological phenomena can lead to fallacious asset prioritization, suboptimal resource allocation, and ultimately, portfolio failure.16

A survey of 92 industry practitioners identified several cognitive biases as being particularly pervasive in portfolio decision-making.16 Among the most frequently observed are:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to seek out, interpret, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. In a portfolio context, a project team may unconsciously overweigh positive data from a clinical trial while downplaying or explaining away negative signals, leading to a skewed assessment of a drug’s potential.16

- Champion Bias: This occurs when the influence or reputation of a project’s advocate—often a senior scientist or executive—disproportionately affects its evaluation. The project is judged not solely on its own merits, but on the perceived track record of its “champion,” leading to the selection of projects based on internal politics rather than objective data.16

- Sunk-Cost Fallacy: This is the tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made. This bias is a primary driver of one of the most significant challenges in pharma portfolio management: the failure to terminate failing projects in a timely manner.16 Teams and executives become emotionally and professionally invested in a project, and the prospect of “wasting” the millions of dollars already spent makes it psychologically difficult to make the rational decision to cut losses. This leads to the proliferation of “zombie” projects that continue to consume scarce resources with little hope of return, bloating the portfolio and starving more promising candidates.16

These biases are not isolated psychological quirks; they have profound systemic consequences. The immense financial and career risks associated with R&D failure create a powerful organizational incentive for risk aversion. This environment naturally amplifies biases like Loss Aversion, where the pain of a loss is felt more acutely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain.16 Consequently, decision-makers may systematically favor safer, incremental projects over high-risk, high-reward innovations that have the potential to be transformative. This strategic preference often leads to a focus on developing “me-too” drugs in already crowded therapeutic areas, where the scientific and regulatory paths are better understood.18 However, this seemingly rational response to high failure rates creates a strategic paradox. These crowded, commoditized markets are precisely the ones most susceptible to the intense price erosion and margin collapse described previously.1 Thus, the very attempt to mitigate scientific risk through conservative project selection can lead directly to a portfolio strategy that guarantees low commercial returns. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle of poor R&D productivity, where the rational fear of failure inadvertently drives strategic choices that ensure financial mediocrity. It is this complex interplay of external economic pressure, internal statistical difficulty, and ingrained human bias that constitutes the modern pharmaceutical crucible and creates the undeniable imperative for a more disciplined, data-driven, and algorithmic approach to portfolio optimization.

II. Foundational Frameworks for Valuation: The Power and Pitfalls of rNPV

To impose order on the chaos of pharmaceutical R&D, portfolio managers have long sought quantitative tools to guide their investment decisions. For more than two decades, the cornerstone of this effort has been a financial valuation methodology adapted specifically for the unique risks of drug development: the risk-adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV).2 This framework provides a structured, systematic way to estimate the economic value of a drug candidate by integrating projections of future cash flows with the probabilities of success at each stage of the development lifecycle. Understanding the construction, application, and inherent limitations of the rNPV model is essential, as it represents both the foundation upon which modern algorithmic methods are built and the flawed paradigm they seek to transcend.

2.1 The Logic of Discounted Cash Flow in Pharma: From NPV to rNPV

At its core, any financial valuation of a long-term project begins with the principle of Net Present Value (NPV). NPV is defined as the difference between the present value of future cash inflows and the present value of future cash outflows over a period of time.20 The calculation discounts future cash flows to their value in today’s dollars, accounting for the fundamental financial concept of the time value of money—a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow—and the risk associated with the investment. The standard NPV formula is:

NPV=t=0∑n(1+i)tRt

Where Rt is the net cash flow during a single period t, i is the discount rate, and n is the total number of time periods.21 A project with a positive NPV is generally considered a worthwhile investment, while one with a negative NPV is not.21

However, this standard NPV model is inadequate for valuing early-stage pharmaceutical assets. The primary reason is its handling of risk. In a conventional NPV analysis, the profound risk of project failure is bundled implicitly into a single, very high discount rate.1 This approach has two major drawbacks. First, it is a blunt instrument that fails to capture the dynamic, stage-specific nature of drug development risk; the probability of failure is much higher in Phase II than it is after a successful Phase III trial. Second, applying a single high discount rate to all future cash flows disproportionately penalizes the revenues that occur many years in the future, potentially undervaluing long-term, transformative assets.23

To address these shortcomings, the industry adopted the risk-adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV) model, also referred to as expected NPV (eNPV), which has become the de facto standard for valuing clinical-stage assets.1 The key innovation of rNPV is that it unbundles the distinct components of risk. It uses a lower discount rate to account for the time value of money and commercial risk, while explicitly accounting for development risk by multiplying the cash flows at each stage by the

Probability of Success (PoS) for that stage.23 This probability is also known as the Probability of Technical and Regulatory Success (PTRS).24 This creates a more nuanced and dynamic valuation that changes as an asset progresses through the R&D pipeline and its probability of reaching the market increases.27

2.2 Anatomy of an rNPV Model: Deconstructing the Inputs

A credible rNPV model is not a simple calculation but a complex synthesis of multiple, distinct forecasts. The final valuation is only as reliable as the inputs that feed it. A thorough deconstruction of an rNPV model reveals four critical components, each presenting a significant analytical challenge.

- Forecasting Revenues (Cash Inflows): The primary driver of positive value in an rNPV model is the projection of post-launch revenues. This is not a single peak sales number but a forecast of the entire commercial lifecycle, from the initial market uptake curve to the sharp revenue decline, or “patent cliff,” that occurs at the Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) when generic or biosimilar competitors enter the market.26 Two main methodologies are used: a top-down analysis, which estimates the drug’s potential market share within a defined therapeutic area, and a bottom-up analysis, which builds the forecast from the size of the addressable patient population, pricing assumptions, and expected treatment duration.26

- Estimating Costs (Cash Outflows): The negative cash flows in an rNPV model are dominated by R&D expenditures. These costs are not uniform; they escalate dramatically as a drug progresses through development, with Phase III trials being the most expensive component.22 Accurate, phase-specific cost estimation is therefore essential. The model must also account for post-launch costs, including the cost of goods sold (COGS) and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses.

- Determining Probability of Success (PoS/PTRS): This is the most defining and scrutinized input in the model, as it numerically represents the asset’s unique development risk.26 Traditionally, these probabilities are derived from large-scale, retrospective analyses of historical industry data, which show how many drugs successfully transition from one phase to the next. These benchmarks vary significantly by development stage, therapeutic area (e.g., oncology has different success rates than anti-infectives), and drug modality (e.g., small molecules versus biologics).26

- Selecting the Discount Rate: The discount rate in an rNPV model accounts for the risks that remain after adjusting for the probability of development failure—namely, the time value of money and commercial risk (e.g., the risk of underperforming against sales forecasts even if approved). This rate is typically based on the company’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), which reflects the blended cost of its equity and debt financing.21 The appropriate discount rate varies by stage and company type. A pre-revenue biotech firm, financed entirely by high-risk equity, will have a much higher WACC and thus a higher discount rate than a large, profitable pharmaceutical company with a balanced capital structure. Industry benchmarks suggest discount rates ranging from 15-18% for preclinical assets down to 10-13% for assets in Phase III.26

Table 2: Deconstructing the rNPV Model

| Input Component | Definition & Role in Model | Common Data Sources & Methodologies | Key Sensitivities & Potential Biases |

| Peak Sales Forecast | The projected maximum annual revenue a drug will achieve. It is the primary driver of positive cash flows. | Market research reports, competitive intelligence, epidemiological data, patient-based forecasting models (top-down/bottom-up). | Highly sensitive to assumptions about market share, price, and patient uptake. Susceptible to Optimism Bias from commercial teams. |

| R&D Costs by Phase | The estimated out-of-pocket expenses for each stage of clinical development (Phase I, II, III) and for regulatory submission. | Historical internal company data, industry benchmark reports, clinical trial cost simulators. | Can be underestimated, especially for complex trials. Fails to capture the full capitalized cost of failures. |

| Probability of Success (PoS) by Phase | The probability that a drug will successfully transition from its current phase to the next. It is the key risk-adjustment factor. | Historical industry benchmark data (e.g., from BIO, PhRMA), proprietary company data, expert opinion. | Highly sensitive to the choice of benchmark data (e.g., TA-specific vs. general). Susceptible to Confirmation Bias and Champion Bias. |

| Discount Rate (WACC) | The rate used to discount future risk-adjusted cash flows to their present value. Accounts for time value of money and commercial risk. | Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) to determine cost of equity, analysis of company’s debt structure, industry benchmarks. | Choice of rate can be subjective. Using a rate that is too low will inflate the valuation. |

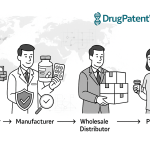

| Patent Expiry Date (LOE) | The date when market exclusivity is lost, leading to a sharp decline in revenue (the “patent cliff”). Defines the duration of peak cash flows. | Patent databases (e.g., DrugPatentWatch), regulatory filings (e.g., FDA Orange Book), legal analysis. | Can be extended by secondary patents or regulatory exclusivities, creating complexity. Litigation outcomes can alter dates unexpectedly. |

Note: This table outlines the primary components of a standard rNPV model. The quality of the final valuation is entirely dependent on the rigor and objectivity of these input forecasts. Data synthesized from.16

2.3 The Limits of the Standard: “Misplaced Concreteness” and Strategic Blind Spots

Despite its widespread use, the standard rNPV model suffers from significant limitations that can lead to flawed strategic decision-making. Its primary weakness is that it can create a sense of “misplaced concreteness”—the tendency to treat a single, precise numerical output as an objective fact, while overlooking the profound uncertainties and subjective assumptions embedded in its inputs.19

One fundamental conceptual problem is that the rNPV method applies a probability weighting to cash flows. For example, if a Phase II trial costs $100 million and has a 45% chance of success to enter Phase III, the model calculates a risk-adjusted cash flow based on 45% of the subsequent costs and revenues. In reality, however, there is no such thing as 45% of a cash flow; the outcome is binary. The trial either succeeds, and the company incurs the full cost of Phase III, or it fails, and there are no further cash flows.19 By averaging these potential outcomes, the standard rNPV model obscures the true, bimodal risk profile of the asset and fails to capture the full impact of a catastrophic failure.

This issue is compounded by the model’s extreme sensitivity to its inputs. As the deconstruction in the previous section shows, every key variable—from peak sales to PoS—is a forecast, not a certainty. These forecasts are often generated by internal teams and external experts who are themselves subject to the cognitive biases discussed in Section I. An overly optimistic commercial team can inflate sales projections, or a powerful project champion can influence the internal assessment of a drug’s PoS. These biased inputs are then fed into the rNPV formula. The model performs its mathematical operations correctly, but the output is merely a precise calculation based on flawed premises. The final rNPV figure, presented as a hard number like “$484 million,” lends an air of objectivity and authority that can mask the underlying subjectivity. In this way, the rNPV model, while intended to bring quantitative rigor, can inadvertently function as a sophisticated mechanism for “bias laundering,” transforming subjective hopes and political influence into an objective-looking financial justification.

Finally, the rNPV framework has a major strategic blind spot. Due to the nature of discounting and the compounding of probabilities, the model inherently favors projects that are shorter-term, lower-risk, and offer more certain, albeit smaller, returns. A long-term, high-risk, potentially transformative project in a novel disease area will be heavily penalized by years of discounting and low cumulative success probabilities. In contrast, a “me-too” drug in a well-understood class entering Phase III will have a much higher rNPV. When used as the primary tool for prioritization, rNPV can systematically steer a company’s portfolio away from breakthrough innovation and towards incrementalism, undermining long-term growth and competitive advantage.19

III. The Algorithmic Intervention: Introducing Mathematical Rigor to Portfolio Selection

The limitations of single-asset valuation tools like rNPV necessitate a more sophisticated approach—one that moves beyond simply ranking individual projects to optimizing the entire portfolio as a cohesive strategic entity. This marks a pivotal shift from asking “What is this drug worth?” to asking “What is the optimal combination of drugs to pursue to achieve our corporate objectives?” To answer this more complex question, pharmaceutical companies are increasingly turning to algorithmic methods adapted from the fields of modern finance and operations research. These techniques provide a mathematical framework for constructing portfolios that maximize value and balance risk, all while adhering to real-world resource constraints.

3.1 Principles of Modern Portfolio Theory in a Pharmaceutical Context

The foundational concept for modern quantitative portfolio management is Mean-Variance Optimization (MVO), introduced by Nobel laureate Harry Markowitz in 1952.30 MVO is based on the principle that an investor’s goal is to maximize a portfolio’s expected return for a given level of risk, which is defined as the variance (or standard deviation) of the returns. The set of all portfolios that offer the highest expected return for each level of risk is known as the

“efficient frontier”.30 Any portfolio not on this frontier is suboptimal because another portfolio exists that offers either a higher return for the same risk or the same return for lower risk.

These financial concepts can be powerfully adapted to a pharmaceutical portfolio. In this context, a drug asset’s “expected return” can be represented by its risk-adjusted NPV, and its “risk” can be defined as the variance or uncertainty surrounding that rNPV, driven by the probabilities of clinical success and the volatility of commercial forecasts.31 The MVO algorithm then uses the expected returns of all candidate projects, their individual variances, and the correlations between them to identify the specific combination of projects that constitutes the efficient frontier.

The introduction of MVO represents a fundamental paradigm shift away from simple rNPV ranking. Traditional analysis evaluates each asset in isolation, leading to a list of projects ranked by their standalone value. MVO, by contrast, forces a holistic, combinatorial analysis. Its core principle is that the risk of an asset should not be viewed alone, but in terms of how it contributes to the overall portfolio’s risk. An asset with high standalone risk might actually reduce total portfolio risk if its outcomes are uncorrelated or negatively correlated with other assets in the portfolio. For example, a high-risk, novel Alzheimer’s drug might be a strategically valuable addition to a portfolio dominated by lower-risk oncology drugs. Because the biological and market success of the Alzheimer’s drug is likely independent of the oncology assets, it provides true diversification, making the overall portfolio more resilient. This is a concept that simple rNPV ranking is blind to. It moves the organization from tactical asset selection to true strategic portfolio construction.

Despite its power, MVO has limitations, including a high sensitivity to its input estimates—small errors in expected returns can lead to large changes in the optimal portfolio.31 This has led to the exploration of alternative frameworks like

Risk Parity, which seeks to construct a portfolio where each asset contributes equally to the overall portfolio risk.31 This approach, which focuses on diversifying risk rather than maximizing return, is particularly relevant for the pharmaceutical industry, where the binary, high-impact failure of a single late-stage candidate can have devastating consequences for a company’s future.

3.2 Resource Allocation as a Constrained Optimization Problem

Beyond balancing risk and return, a central challenge of portfolio management is allocating finite resources—capital, personnel, and infrastructure—among competing projects. This can be framed as a classic constrained optimization problem, solvable with techniques from the field of operations research, such as mathematical programming.

Linear Programming (LP) and Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP) are powerful techniques for determining the optimal course of action when resources are limited.33 In the context of a drug portfolio, the objective function is typically to maximize the total rNPV of the selected projects. This objective is then subjected to a series of constraints, such as:

- A total R&D budget that cannot be exceeded.

- Limits on the number of projects that can be active in a specific phase (e.g., a maximum of three Phase III trials at any one time due to limited clinical operations capacity).

- Headcount constraints for specific scientific departments.

- Strategic goals, such as ensuring a certain number of projects are in a particular therapeutic area.

A concrete application of this approach is in optimizing the allocation of promotional resources. One study detailed a 0-1 mixed-integer program designed to allocate drug samples to thousands of healthcare providers (HCPs) to maximize the projected uplift in prescriptions.36 The model’s decision variables were binary (

xij ∈ {0,1}), representing whether to choose a specific sample-drop scenario j for HCP i. The objective was to maximize the total uplift, subject to constraints on the per-HCP sample counts, territory-level budgets, and a global pill budget.36 This demonstrates how MIP can translate complex business rules and resource limitations into a solvable mathematical problem to drive efficient resource allocation.

While LP and MIP assume linear relationships, many real-world dynamics are non-linear. For example, the response to marketing spend often shows diminishing marginal returns, and the value of adding a third drug to a therapeutic franchise may not be additive due to market cannibalization. In such cases, Non-Linear Programming (NLP) models are required to capture these complex relationships and find an optimal solution.35

3.3 Modeling Uncertainty with Monte Carlo Simulation

Both MVO and mathematical programming rely on input parameters that are treated as single-point estimates (e.g., an expected return, a fixed project cost). This approach, like standard rNPV, can fall prey to the “misplaced concreteness” fallacy, masking the profound uncertainty inherent in drug development. Monte Carlo simulation is a computational algorithm that directly addresses this problem by explicitly modeling uncertainty.19

The methodology is straightforward but powerful. Instead of using a single value for an uncertain input, the analyst defines a probability distribution that represents the range of possible values. For example, instead of assuming a Phase II trial will cost exactly $86 million, one might model it with a triangular distribution defined by a minimum ($70 million), most likely ($85 million), and maximum ($120 million) cost.40 The simulation then runs the entire portfolio model thousands or even tens of thousands of times. In each iteration, it draws a random value for each uncertain variable from its specified probability distribution. The result is not a single NPV for the portfolio, but a probability distribution of thousands of possible NPV outcomes.38

This approach provides a much richer and more realistic picture of the portfolio’s risk-return profile. It allows managers to answer questions like: “What is the probability that our portfolio’s NPV will be negative in five years?” or “What is the 90% confidence interval for our total R&D spend over the next decade?”.41 Monte Carlo simulation is particularly adept at modeling complex systems with many interacting variables and dependencies. For instance, it can model a scenario where the delay of one project (due to a random event like slow patient recruitment) has a cascading effect on the start times and resource availability for other projects in the pipeline.39 By simulating the full range of possible futures, it provides a robust foundation for making strategic decisions under uncertainty, moving far beyond the limitations of deterministic, single-point-estimate models.

Table 3: A Comparative Analysis of Optimization Methodologies

| Methodology | Primary Objective | Handling of Uncertainty | Key Data Requirements | Primary Use Case in Pharma |

| rNPV | Maximize the risk-adjusted value of a single asset. | Single-point Probability of Success (PoS) estimates for each phase. | Cash flow forecasts (revenues, costs), phase-specific PoS, discount rate. | Initial valuation and ranking of individual drug development projects. |

| Mean-Variance Optimization (MVO) | Minimize portfolio variance (risk) for a given level of expected return; identify the efficient frontier. | Uses variance and covariance of asset returns. Assumes returns are normally distributed. | Expected rNPV for each asset, variance of rNPVs, and the covariance matrix between all assets. | Strategic portfolio construction to achieve optimal risk-return trade-offs and diversification benefits. |

| Risk Parity | Construct a portfolio where each asset contributes equally to the overall portfolio risk. | Focuses on risk contribution rather than return forecasts. Less sensitive to return estimate errors. | Volatility of each asset and correlations between assets. | Building a more resilient portfolio that is less exposed to the failure of any single high-risk asset. |

| Linear/Integer Programming | Maximize a total value (e.g., portfolio rNPV) subject to a set of linear constraints. | Deterministic; does not inherently model uncertainty, but relies on expected values as inputs. | Objective function coefficients (e.g., rNPV of each project), resource usage per project, and constraint limits (e.g., total budget). | Tactical and operational resource allocation; selecting the optimal subset of projects to fund under strict budget or capacity limits. |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Model the full range of possible outcomes for a portfolio by simulating thousands of scenarios. | Explicitly models uncertainty by using probability distributions for all key variables instead of single-point estimates. | Probability distributions for all uncertain inputs (costs, timelines, PoS, revenues, etc.). | Quantifying the full range of potential portfolio outcomes and understanding the probability of achieving strategic goals or facing catastrophic losses. |

Note: These methodologies form a complementary toolkit. For instance, Monte Carlo simulation can generate robust, probabilistic inputs that are then used in a Mean-Variance Optimization framework to construct an efficient portfolio, which is then refined using Linear Programming to ensure it adheres to budget constraints. Data synthesized from.19

IV. The Intelligence Layer: AI and Machine Learning in Predictive Portfolio Management

The mathematical frameworks introduced in the previous section—MVO, constrained optimization, and Monte Carlo simulation—provide powerful tools for constructing and evaluating portfolios based on a given set of inputs. However, their effectiveness is fundamentally limited by the quality of those inputs. The true revolution in drug portfolio management lies in the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) to dramatically improve the accuracy, objectivity, and dynamism of the predictive data that fuels these optimization engines. This “intelligence layer” moves beyond optimizing with existing information to generating superior, forward-looking insights, transforming the entire portfolio management process from a static calculation into a dynamic, learning system.

4.1 Forecasting the Unforecastable: Using Machine Learning to Predict PTRS

The most significant weakness of traditional rNPV and its derivatives is the reliance on static, historical benchmarks for the Probability of Success (PoS). Using an industry-average success rate for a specific therapeutic area is a crude approximation that fails to account for the unique characteristics of an individual drug program. Machine Learning offers a vastly superior approach to estimating an asset-specific Probability of Technical and Regulatory Success (PTRS).29

The core advantage of ML lies in its ability to analyze massive, high-dimensional datasets and identify complex, non-linear patterns that correlate with clinical and regulatory success—patterns that are often invisible to traditional regression analysis or human experts.29 An ML model can simultaneously consider hundreds of features related to a drug’s biology, its clinical trial design, the competitive landscape, and the sponsoring company’s track record to generate a nuanced, data-driven probability of success.46 This approach has demonstrated remarkable performance, with some models achieving retrospective predictive accuracy of 83-89% and prospective accuracy of 80%, far exceeding the 56-70% accuracy of methods based on historical averages alone.43 By replacing a generic benchmark with a tailored, asset-specific PTRS, ML provides a much more reliable input for valuation and optimization models, allowing for a more accurate differentiation between promising and unpromising assets.

4.2 The Data Fueling the AI Engine: A Multi-Modal Approach

The predictive power of any ML model is entirely dependent on the quality, breadth, and depth of the data on which it is trained. Building a robust PTRS prediction engine requires the creation of a vast, integrated data ecosystem that spans multiple domains of pharmaceutical R&D. This is not simply a matter of accessing large databases; it involves the immense challenge of curating, cleaning, and harmonizing structured and unstructured data from dozens of disparate sources into a consistent, AI-ready format.29 The key data categories that fuel these advanced models are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4: Key Data Features for AI-Powered PTRS Prediction

| Category | Specific Feature | Rationale & Impact on Success | Common Data Sources |

| Drug Biology & Target | Target Novelty (First-in-class vs. Validated) | First-in-class targets carry higher scientific risk but offer greater commercial potential if successful. Validated targets have lower risk. | PubMed, Genetic Databases, Pathway Analysis Tools |

| Biomarker Presence/Use | Trials using validated biomarkers to select patients are significantly more likely to succeed than those without. | ClinicalTrials.gov, Scientific Literature, Company Presentations | |

| Modality (Small Molecule, mAb, Gene Therapy) | Different modalities have distinct historical success profiles, safety concerns, and manufacturing complexities. | Industry Databases, Regulatory Filings | |

| Clinical Trial Design | Phase of Development | The most fundamental predictor; success probability increases significantly after passing each phase. | ClinicalTrials.gov, Corporate Pipelines |

| Endpoint Type (e.g., OS, PFS, Surrogate) | Choice of primary endpoint is critical. Trials relying on surrogate endpoints may face higher regulatory scrutiny. | Trial Protocols, FDA/EMA Guidance Documents | |

| Control Arm Type (Placebo vs. Active) | Trials against an active comparator have a higher bar for demonstrating superiority, affecting the probability of success. | ClinicalTrials.gov | |

| Patient Population Size & Accrual Rate | Trial size impacts statistical power. Slow patient accrual is a leading cause of trial delays and failure. | Trial Registries, Historical Trial Performance Data | |

| Regulatory Factors | Regulatory Designation (e.g., Fast Track) | Designations like Breakthrough Therapy are correlated with higher success rates, indicating regulatory alignment on unmet need. | FDA/EMA Databases, Company Press Releases |

| Historical Regulatory Precedents | Past regulatory decisions for similar drugs in the same indication provide powerful clues about agency expectations. | Drugs@FDA, EMA EPARs, Regulatory Intelligence Reports | |

| Commercial Landscape | Unmet Medical Need | Drugs addressing high unmet needs are more likely to receive regulatory flexibility and achieve strong market access. | Market Research Reports, KOL Interviews, RWE |

| Competitive Landscape | The number and stage of competitor programs in the same indication directly impact future market share and pricing power. | Commercial Intelligence Platforms (e.g., DrugPatentWatch) | |

| Intellectual Property | Patent Expiration & Litigation Risk | The strength and duration of patent protection define the commercial lifecycle. High litigation risk adds uncertainty. | Patent Databases (USPTO, EPO), Legal Databases |

| Company-Specific Factors | Sponsor Track Record | Companies with a history of successful drug development in a specific therapeutic area have a higher probability of future success. | Historical Approval Data, Financial Reports |

Note: This table illustrates a subset of the hundreds of features that can be used to train a machine learning model for PTRS prediction. The ability to integrate and analyze these diverse data types is the key advantage of AI-driven approaches. Data synthesized from.28

4.3 Beyond PTRS: AI for Dynamic Market Forecasting and Lifecycle Management

The application of AI in portfolio management extends far beyond the prediction of clinical success. The same principles of learning from vast datasets can be applied to improve the accuracy and dynamism of commercial forecasting. Traditional sales forecasts often rely on static assumptions about market growth and competitor actions. AI models, in contrast, can analyze real-time data streams—including physician prescribing patterns, electronic health records, insurance claims data, and even market sentiment from news articles and social media—to generate more nuanced and continuously updated market forecasts.48 This allows for a more realistic projection of a drug’s revenue potential, a critical input for any valuation model.

Furthermore, advanced AI techniques like Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) are being explored for dynamic portfolio management, drawing parallels to their successful application in algorithmic financial trading.60 A DRL agent can be trained to make sequential resource allocation decisions over time. It learns an optimal policy by observing the state of the portfolio and the external environment, taking an action (e.g., accelerate Project A, terminate Project B), and receiving a reward based on the outcome (e.g., an increase in the portfolio’s long-term expected value). This allows the system to learn how to adaptively rebalance the portfolio in response to new information, such as the unexpected failure of a competitor’s trial or a change in regulatory guidance.60

The synthesis of these advanced algorithmic components—ML for asset-specific prediction, Monte Carlo for uncertainty modeling, and MVO or DRL for holistic optimization—enables the creation of a powerful new strategic tool: a “digital twin” of the R&D portfolio. This is not merely a static spreadsheet or valuation model; it is a dynamic, in-silico simulation environment that mirrors the real-world portfolio and its potential future states. This digital twin allows executives to move beyond simple valuation to conduct sophisticated strategic “wargaming.” They can ask and receive data-driven answers to complex “what-if” scenarios that were previously intractable. For example: “What is the impact on our portfolio’s 5-year expected value and risk profile if we de-prioritize our lead oncology asset and acquire a Phase II immunology drug with a 45% ML-predicted PTRS?” or “Let’s simulate the impact of a key competitor’s unexpected Phase III success on the commercial viability of our lead candidate and identify the optimal reallocation of its marketing budget.” This capability transforms portfolio management from a periodic, retrospective assessment into a continuous, forward-looking strategic planning function, allowing organizations to navigate uncertainty with far greater agility and foresight.

V. Implementation and the Path Forward: From Algorithm to Organizational Reality

The theoretical power of algorithmic drug portfolio optimization is immense, promising to bring quantitative rigor, predictive accuracy, and strategic agility to one of the most complex business challenges in the world. However, translating this potential into tangible value requires more than just sophisticated software; it demands a deep understanding of the practical implementation hurdles, a clear-eyed view of the return on investment, and a commitment to navigating the profound organizational and cultural changes that these new technologies entail. The path forward involves learning from real-world applications, directly confronting the barriers to adoption, and keeping an eye on the next frontier of technological innovation.

5.1 Algorithmic Optimization in Practice: Case Studies and ROI

Evidence of the value of AI and advanced analytics in pharmaceutical R&D is rapidly accumulating. Leading companies are no longer just experimenting with these tools but are integrating them into core processes, with measurable results.

- AstraZeneca has been a pioneer in using AI to enhance its R&D productivity. The company employs sophisticated knowledge graphs that integrate vast datasets on genomics, disease pathways, and clinical information. By applying graph neural networks to this data, AstraZeneca can uncover novel biological patterns and predict new drug targets. This approach led to the selection of the first two AI-generated drug targets into the company’s portfolio in 2021, in collaboration with BenevolentAI.53 AstraZeneca also uses AI across 70% of its small molecule chemistry projects to predict which molecules to synthesize next, significantly accelerating the design-make-test-analyze cycle.53 One case study highlights an AI agent that reduced the time required for discovering potential treatments for chronic kidney disease by 70%, fast-tracking drugs for clinical development.61

- Insilico Medicine demonstrated the dramatic potential of AI to shorten development timelines. Using its generative AI platform, the company designed a novel drug candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and advanced it from initial concept to the start of human clinical trials in under 30 months—a fraction of the industry average.62

- Pfizer has applied AI to optimize various aspects of its R&D pipeline. The company uses machine learning to improve the quality of regulatory submissions by predicting in advance what questions regulators are likely to ask, saving weeks of back-and-forth communication.63 Pfizer has also used AI-powered in-silico simulations to optimize the design of clinical trials, including for its vaccine programs.64

The return on investment (ROI) from these applications is substantial. A McKinsey Global Institute analysis estimates that AI could generate up to $110 billion in annual economic value for the pharmaceutical industry.65 Their research suggests that AI has the potential to enhance R&D throughput by more than 100%.66 A separate McKinsey report projects that generative AI alone could create upwards of $50 billion in annual value across the discovery, research, and clinical development phases.67 These gains are driven by multiple factors: a 10% increase in trial success rates through better patient selection, a 15-30% acceleration in trial timelines, and a 15-30% boost in productivity.67 A PwC study corroborates this potential, projecting that innovative pharmaceutical companies could see their operating margins climb from 20% to over 40% by 2030 with strategic AI adoption.68

5.2 Critical Challenges to Adoption: The Human and Technical Hurdles

Despite the compelling ROI, the path to implementing algorithmic portfolio management is fraught with significant challenges that are as much human as they are technical.

- The “Black Box” Problem and Regulatory Acceptance: One of the most frequently cited barriers to AI adoption is the “black box” nature of many advanced machine learning models, particularly deep neural networks.69 When a model recommends de-prioritizing a multi-billion-dollar drug program, executives and scientists understandably want to know

why. The inability of some models to provide a clear, interpretable rationale for their predictions can erode trust and hinder adoption.70 However, the regulatory perspective on this issue is more pragmatic than often assumed. Officials from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have indicated that they are prepared to consider AI applications even if they are not fully explainable. The agency’s focus is less on the internal workings of the model and more on its validation, performance, and the transparency of the data used to train it.71 If the output of a black box model is supported by other corroborating evidence, it can be considered a valid part of a regulatory submission. This pragmatic stance suggests that while explainability is desirable, a lack of it is not an insurmountable barrier if the model’s performance can be rigorously validated.71 - Data Quality, Integration, and Governance: The adage “garbage in, garbage out” is acutely true for AI. The predictive models described in Section IV are only as good as the vast, multi-modal data they are trained on. A major technical hurdle for most pharmaceutical companies is their fragmented and siloed data landscape.72 Clinical trial data, genomic data, commercial forecasts, and regulatory information often reside in legacy systems that do not communicate with each other. The data itself is frequently of low quality, inconsistent, or incomplete.74 The process of collecting, cleaning, standardizing, and integrating these disparate datasets into a harmonized, AI-ready format is a massive and costly undertaking that is often underestimated.47 Without a robust data governance strategy, any AI initiative is doomed to fail.

- Organizational and Cultural Resistance: Arguably the greatest barrier to adoption is human. The introduction of algorithmic decision-making can be perceived as a threat to the autonomy and authority of experienced managers and scientists.75 This can lead to significant organizational resistance, driven by a fear of change, a desire to maintain control, and a fundamental distrust of algorithms.73 Overcoming this resistance requires a concerted change management effort. Leadership must champion a culture of innovation that encourages experimentation and rewards data-driven decision-making.76 This involves not only implementing new technology but also investing heavily in upskilling teams to be data-literate and fostering a collaborative environment where domain experts and data scientists can work together effectively.77

This final point highlights a crucial re-framing of the human role in an AI-augmented organization. The implementation of a mature algorithmic portfolio optimization system does not eliminate the need for human experts; it fundamentally inverts their role. Traditionally, experts have been the primary source of subjective inputs and heuristic decisions—a process proven to be vulnerable to bias. In the new paradigm, the expert’s role shifts to become the critical interrogator and validator of the model’s outputs. Their job is no longer to provide the initial guess for a drug’s PoS, but to stress-test the model’s recommendations. They must ask sophisticated questions like: “The model is de-prioritizing our lead oncology asset. Let’s examine the key features driving its low PTRS prediction. Does it correctly interpret the nuance of this novel biomarker data?” or “The optimized portfolio is heavily weighted towards immunology. What assumptions about market growth and competitive entry is the model making, and are they realistic?” This requires a new hybrid skill set, blending deep domain knowledge with data literacy. The successful organization will not replace its experts with AI but will empower them to collaborate with it, transforming their role from one of biased intuition to one of sophisticated, data-informed skepticism and strategic oversight.

5.3 The Next Frontier: Generative AI and Quantum Computing

Looking ahead, the evolution of algorithmic portfolio optimization will be shaped by the next wave of transformative technologies.

- Generative AI: While current AI models excel at prediction and classification, Generative AI is moving the frontier from analysis to creation. In drug discovery, generative models like VAEs and GANs are already being used to design entirely novel molecules with optimized properties from scratch.78 This allows researchers to explore vast regions of chemical space that are inaccessible through traditional screening methods. The application to portfolio management is equally profound. In the future, generative AI could be used to create entire portfolio strategies or optimal clinical development plans, which could then be tested and refined within the “digital twin” simulation environment. This moves the technology from being a decision-support tool to a strategic-generation engine.78

- Quantum Computing: On a longer time horizon, quantum computing holds the potential to solve optimization problems that are computationally intractable for even the most powerful classical computers.81 Portfolio optimization, especially for a large company with hundreds of assets and complex interdependencies, is a massive combinatorial problem. Quantum algorithms are theoretically capable of exploring the entire solution space simultaneously, potentially finding a truly global optimum that classical algorithms can only approximate.82 While still in its early stages, the application of quantum computing to financial portfolio optimization is an active area of research, and its eventual application to the even more complex domain of pharmaceutical portfolios could represent another paradigm shift in strategic management.81

Conclusion

The pharmaceutical industry stands at a critical inflection point. The traditional models of R&D and portfolio management, which relied on heuristic decision-making and static financial tools, are no longer sufficient to navigate an environment defined by intense economic pressures, staggering rates of scientific failure, and the inherent biases of human judgment. The path from the current state of chaos to a future of strategic clarity is paved with data and algorithms.

This report has detailed the evolution of a new paradigm: Algorithmic Drug Portfolio Optimization. This approach systematically replaces subjective intuition with data-driven rigor at every stage of the decision-making process. It begins by acknowledging the limitations of foundational valuation tools like rNPV, which, while useful, can create a false sense of precision and even serve to legitimize cognitive biases. It then introduces a toolkit of mathematical optimization and simulation techniques—from Modern Portfolio Theory to Monte Carlo analysis—that shift the strategic focus from valuing individual assets in isolation to constructing a holistically optimized portfolio that balances risk, return, and resource constraints.

The true transformative power of this new paradigm is unlocked by the intelligence layer of AI and machine learning. By leveraging vast, multi-modal datasets, ML models can generate asset-specific predictions of clinical success with unprecedented accuracy, providing far more reliable inputs for the optimization engines. The synthesis of these capabilities enables the creation of a dynamic “digital twin” of the R&D portfolio—a sophisticated simulation environment for strategic wargaming and continuous, adaptive planning.

However, the journey to implementation is not merely a technical one. It requires confronting significant challenges related to data infrastructure, the “black box” nature of some algorithms, and, most importantly, organizational culture. Success will not come from replacing human experts with AI, but from fundamentally inverting their role—transforming them from sources of subjective inputs into sophisticated interrogators of algorithmic outputs.

As emerging technologies like Generative AI and quantum computing appear on the horizon, the pace of change will only accelerate. The pharmaceutical companies that will thrive in the coming decades will be those that embrace this algorithmic transformation. They will be the organizations that successfully build the data foundations, cultivate the necessary talent, and foster a culture that weds human expertise with machine intelligence to make smarter, faster, and more objective decisions in the relentless pursuit of the next generation of life-saving medicines.

Works cited

- From Chaos to Clarity: Streamlining Your Generic Drug Portfolio – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/from-chaos-to-clarity-streamlining-your-generic-drug-portfolio/

- Challenges of Portfolio Management in Pharmaceutical Development – IDEAS/RePEc, accessed August 17, 2025, https://ideas.repec.org/h/spr/sprchp/978-3-319-09075-7_5.html

- Potential Impact of the IRA on the Generic Drug Market – Lumanity, accessed August 17, 2025, https://lumanity.com/perspectives/potential-impact-of-the-ira-on-the-generic-drug-market/

- Cost of drug development – Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cost_of_drug_development

- What’s the average time to bring a drug to market in 2022? – N-SIDE, accessed August 17, 2025, https://lifesciences.n-side.com/blog/what-is-the-average-time-to-bring-a-drug-to-market-in-2022

- R&D Costs | Knowledge Portal, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.knowledgeportalia.org/costs-r-d

- The R&D Cost of a New Medicine – Office of Health Economics, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.ohe.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/380-RD-Cost-NME-Mestre-Ferrandiz-2012.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Industry Facts & Figures – IFPMA, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IFPMA_Always_Innovating_Facts__Figures_Report.pdf

- From the microscope to the macroscopic: changing from the bench to portfolio management – PMC, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5662252/

- Drug Development – HHS ASPE, accessed August 17, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/drug-development

- Why are clinical development success rates falling? – Norstella, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.norstella.com/why-clinical-development-success-rates-falling/

- R&D Time and Success Rate – Knowledge Portal on Innovation and Access to Medicines, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.knowledgeportalia.org/r-d-time-and-success-rate

- Costs of Drug Development and Research and Development Intensity in the US, 2000-2018, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11214120/

- Deloitte pharma study: R&D returns are improving – regulation could stifle innovation, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.deloitte.com/ch/en/about/press-room/deloitte-pharma-study-r-and-d-returns-are-improving.html

- The endless frontier? The recent increase of R&D productivity in …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7147016/

- Trends, challenges, and success factors in pharmaceutical portfolio …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.knowledge-house.com/wp-content/uploads/Trends-challenges-and-success-factors-in-pharmaceutical-portfolio-management_DDT_2023_knowledge-house.com_.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Portfolio Management: A Complete Primer – Planview, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.planview.com/resources/articles/pharmaceutical-portfolio-management-a-complete-primer/

- Drug Attrition in Check: Shifting Information Input to Where it Matters – HARMONY Alliance, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.harmony-alliance.eu/webimages/files/PLS_DDD_WP_Attrition-Elsevier.pdf

- What’s wrong with NPV valuations? – Alacrita, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/whitepapers/pharma-and-biotech-valuations-divergent-perspectives

- Portfolio Management In Pharmaceutical/Biotechnology R&D, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.wcu.edu/pmi/1994/94PMI368.PDF

- Net Present Value (NPV): What It Means and Steps to Calculate It – Investopedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/npv.asp

- Net Present Value in Pharma – Genedata, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.genedata.com/net-present-value-in-pharma

- Why rNPV is Preferred for Biopharmaceutical Valuation – Anplify, accessed August 17, 2025, https://anplify.com/why-rnpv-is-preferred-for-biopharmaceutical-valuation/

- 2025 Ultimate Pharma & Biotech Valuation Guide – BiopharmaVantage, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.biopharmavantage.com/pharma-biotech-valuation-best-practices

- Risk-adjusted net present value – Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://wikipedia.org/wiki/RNPV

- Architecting Value: A Framework for Biotech Asset Valuation from …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://inbistra.com/en/blog/biotech-valuation-framework

- Valuing Pharmaceutical Assets: When to Use NPV vs rNPV – Alacrita, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/whitepapers/valuing-pharmaceutical-assets-when-to-use-npv-vs-rnpv

- Valuation of Pharma Companies: 5 Key Considerations – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/valuation-of-pharma-companies-5-key-considerations-2/

- Why We Need Artificial Intelligence to Predict the Probability of …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.intelligencia.ai/ai-predict-drug-development-success/

- Portfolio optimization – Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portfolio_optimization

- Quantitative Methods for Drug Portfolio Optimization – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/quantitative-methods-for-portfolio-optimization/

- Application of portfolio optimization to drug discovery | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327936103_Application_of_portfolio_optimization_to_drug_discovery

- Where efficiency saves lives: A linear programme for the optimal allocation of health care resources in developing countries | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5147762_Where_efficiency_saves_lives_A_linear_programme_for_the_optimal_allocation_of_health_care_resources_in_developing_countries

- Linear Programming Applications – Number Analytics, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/linear-programming-applications

- Solving Patient Allocation Problem during an Epidemic Dengue Fever Outbreak by Mathematical Modelling, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8775972/

- (PDF) Optimising HCP Sample Allocation in Pharma: Combining …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394456778_Optimising_HCP_Sample_Allocation_in_Pharma_Combining_Non-Linear_Ensemble_Learning_Spatial_Lags_and_Integer_Programming

- Monte Carlo methods in clinical research: applications in multivariable analysis – PubMed, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9291696/

- What Is Monte Carlo Simulation? – IBM, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/monte-carlo-simulation

- The Perks of Using Monte Carlo Simulations in Drug Development, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.captario.com/post/the-perks-of-using-monte-carlo-simulations-in-drug-development

- How do you use Monte Carlo simulation to value real options? – ResearchGate, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/post/How-do-you-use-Monte-Carlo-simulation-to-value-real-options

- Method “Monte Carlo” in healthcare – PMC, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11230067/

- Portfolio-wide Optimization of Pharmaceutical R&D Activities Using Mathematical Programming, accessed August 17, 2025, https://optimization-online.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/7770.pdf

- Improving the Prediction of Clinical Success Using Machine Learning | medRxiv, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.01.21250864v1.full-text

- A Machine Learning approach for assessing drug development risk | bioRxiv, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.08.331926v2.full?trk=public_post_comment-text

- Insights & Solutions for Drug Development – Intelligencia AI FAQs, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.intelligencia.ai/faq/

- Using machine learning to better predict clinical trial outcomes | MIT Sloan, accessed August 17, 2025, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/using-machine-learning-to-better-predict-clinical-trial-outcomes

- A Machine Learning approach for assessing drug development risk – bioRxiv, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.08.331926v1.full-text

- AI-Powered Portfolio Management in Pharmaceuticals – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/ai-powered-portfolio-management-in-pharmaceuticals/

- Unlocking peak operational performance in clinical development with artificial intelligence, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/unlocking-peak-operational-performance-in-clinical-development-with-artificial-intelligence

- [Regulatory Intelligence] Basics of Regulatory Precedence Research : r/RegulatoryClinWriting – Reddit, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/RegulatoryClinWriting/comments/1bvtx8z/regulatory_intelligence_basics_of_regulatory/

- How Regulatory Strategy Drives Innovation in Biopharma – SYNER-G, accessed August 17, 2025, https://synergbiopharma.com/how-regulatory-strategy-drives-innovation-biopharma/

- How to Use Drug Price Data for Generic Entry Portfolio Management and Prioritization, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-use-drug-price-data-for-generic-entry-pricing/

- Data Science & Artificial Intelligence: Unlocking new science insights, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.astrazeneca.com/r-d/data-science-and-ai.html

- Evaluate Ltd. transforms pharma R&D risk assessment with launch of Product Specific PTRS – Massachusetts Biotechnology Council, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.massbio.org/news/member-news/evaluate-ltd-transforms-pharma-rd-risk-assessment-with-launch-of-product-specific-ptrs/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 17, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio and Patent Expiry Risk – Umbrex, accessed August 17, 2025, https://umbrex.com/resources/industry-analyses/how-to-analyze-a-pharmaceutical-company/intellectual-property-ip-portfolio-and-patent-expiry-risk/

- Portfolio Optimization: Best-Practices Strategies to Maximize Value, accessed August 17, 2025, https://unitedlex.com/insights/portfolio-optimization-best-practices-strategies-to-maximize-value/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 17, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch/

- AI in Pharmaceutical Market Analysis | Industry Growth, Size & Forecast Report 2030, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/artificial-intelligence-in-pharmaceutical-market

- A Combined Algorithm Approach for Optimizing Portfolio Performance in Automated Trading: A Study of SET50 Stocks – MDPI, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/13/3/461

- 10 ROI of AI case studies show results – BarnRaisers, LLC, accessed August 17, 2025, https://barnraisersllc.com/2025/06/20/10-roi-of-ai-case-studies-show-results/

- AI in Drug Development: Use-cases and Trends | Scilife, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.scilife.io/blog/ai-in-drug-development

- Artificial Intelligence: On a mission to Make Clinical Drug Development Faster and Smarter, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/news/articles/artificial_intelligence_on_a_mission_to_make_clinical_drug_development_faster_and_smarter

- AI-driven innovations in pharmaceuticals: optimizing drug discovery and industry operations, accessed August 17, 2025, https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2025/pm/d4pm00323c

- Why Big Pharma is Quietly Using AI: Industry Insights for 2025 – PharmaDiversity Blog, accessed August 17, 2025, https://blog.pharmadiversityjobboard.com/?p=408

- R&D recharged by AI | McKinsey & Company, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/week-in-charts/r-and-d-recharged-by-ai

- Faster, smarter trials: Modernizing biopharma’s R&D IT applications – McKinsey, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/faster-smarter-trials-modernizing-biopharmas-r-and-d-it-applications

- AI in Pharma: Use Cases, Success Stories, and Challenges in 2025, accessed August 17, 2025, https://scw.ai/blog/ai-in-pharma/

- AI’s mysterious ‘black box’ problem, explained – University of Michigan-Dearborn, accessed August 17, 2025, https://umdearborn.edu/news/ais-mysterious-black-box-problem-explained

- Don’t settle for black box: Why explainable AI is built for pharma. – Abzu.ai, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.abzu.ai/blog/pharmafocus-dont-settle-for-black-box/

- AI And The ‘Black Box’ Problem: US FDA Is More Comfortable Than …, accessed August 17, 2025, https://insights.citeline.com/PS155189/AI-And-The-Black-Box-Problem-US-FDA-Is-More-Comfortable-Than-Some-May-Think/

- Boosting biopharma R&D performance with a next-generation technology stack – McKinsey, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/boosting-biopharma-r-and-d-performance-with-a-next-generation-technology-stack

- Unlock AI Use Cases in Pharma: The Ultimate Guide – SmartDev, accessed August 17, 2025, https://smartdev.com/ai-use-cases-in-pharma/

- Data Quality Issues Affecting the Pharmaceutical Industry: Finding a Solution – FirstEigen, accessed August 17, 2025, https://firsteigen.com/blog/data-quality-issues-affecting-the-pharmaceutical-industry-finding-a-solution/

- Exploring Facilitators and Barriers to Managers’ Adoption of AI-Based Systems in Decision Making: A Systematic Review – MDPI, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2673-2688/5/4/123

- www.technology-innovators.com, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.technology-innovators.com/building-ai-ready-organizations-cios-strategies-for-overcoming-resistance-to-ai-implementation/#:~:text=Create%20a%20culture%20of%20innovation,willing%20to%20try%20new%20things.

- How is your organization approaching AI adoption? – ProjectManagement.com, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.projectmanagement.com/discussion-topic/219476/how-is-your-organization-approaching-ai-adoption-

- Generative AI in Drug Discovery: Transforming … – DelveInsight, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.delveinsight.com/blog/generative-ai-drug-discovery-market-impact

- The future of generative AI and automation in drug discovery, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.iptonline.com/articles/the-future-of-generative-ai-and-automation-in-drug-discovery

- (PDF) THE FUTURE OF AI-DRIVEN PORTFOLIO OPTIMIZATION IN BIOPHARMACEUTICAL PROGRAM MANAGEMENT – ResearchGate, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388999083_THE_FUTURE_OF_AI-DRIVEN_PORTFOLIO_OPTIMIZATION_IN_BIOPHARMACEUTICAL_PROGRAM_MANAGEMENT

- How quantum computing is changing molecular drug development | World Economic Forum, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/quantum-computing-drug-development/

- The Future of Portfolio Optimization is in Quantum, accessed August 17, 2025, https://meetiqm.com/case-study/the-future-of-portfolio-optimization-is-in-quantum/