Executive Summary

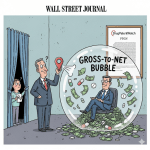

The United States pharmaceutical market is characterized by a complex and often opaque pricing structure, leading to a significant divergence between the initial “list price” of a drug and the “net price” that manufacturers ultimately realize. This considerable gap is frequently referred to as the “gross-to-net bubble,” which reached an estimated $356 billion for brand-name drugs in 2024.1 This intricate system creates substantial opacity, making it challenging for patients, policymakers, and even various industry participants to ascertain the true cost of medications.1

Manufacturer Net Price (MNP) represents the actual revenue a manufacturer receives after accounting for all deductions, including various rebates, discounts, and fees.3 This stands in stark contrast to publicly cited “list prices” such as the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) and Average Wholesale Price (AWP). These list prices are notably higher and do not reflect the actual transaction price paid by purchasers.4 For instance, brand-name drugs are frequently sold for approximately half of their stated list prices after the application of discounts.8 Other price references, including Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) and Average Sales Price (ASP), are closer approximations of net prices as they incorporate various concessions. However, each of these serves a specific regulatory or reimbursement purpose rather than representing the manufacturer’s ultimate realized revenue across all distribution channels.9

The expansion of the gross-to-net bubble is primarily driven by negotiated and statutory rebates, distribution fees, product returns, and program-specific discounts.1 Key intermediaries, such as Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), play a central role in negotiating these rebates. While these negotiations can influence favorable formulary placement for drugs, they can also inadvertently contribute to higher list prices and increased out-of-pocket costs for patients.13 Economic factors, including the substantial costs of research and development (R&D), the period of market exclusivity granted by patents, and the dynamics of competition from generic and biosimilar alternatives, profoundly shape pharmaceutical pricing decisions.15 Furthermore, recent regulatory changes, notably the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and various state-level transparency laws, are beginning to exert downward pressure on prices and enhance accountability within the industry.19 The persistent lack of transparency and the inherent complexity of these pricing mechanisms continue to create significant affordability challenges for patients, often leading to medication non-adherence and considerable financial hardship.23

Introduction: The US Pharmaceutical Pricing Puzzle

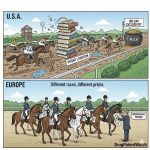

The United States consistently faces the challenge of having the highest prescription drug prices globally. In 2022, prices for both brand-name and generic drugs in the U.S. were nearly three times higher than those in 33 other developed countries.27 This persistent phenomenon is often described as a “puzzle” due to the intricate, multi-layered, and non-transparent nature of drug pricing within the nation’s healthcare system. The complexity stems from a multi-payer model, where numerous transactions occur among diverse entities including manufacturers, wholesalers, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), healthcare providers, and various payers.28 This inherent opacity makes it difficult for patients and policymakers alike to fully comprehend the true economic burden and actual cost of medications.1

At the heart of this “puzzle” lies a central question: Why do manufacturer net prices differ so significantly from other common price references in the U.S. pharmaceutical market? This report aims to dissect this fundamental divergence between the publicly visible “list prices” and the “net prices” that pharmaceutical manufacturers ultimately receive. By defining these key price references and explaining the complex mechanisms that contribute to the “gross-to-net bubble,” a clearer understanding of this critical issue can be achieved.

Understanding these pricing discrepancies is paramount for all stakeholders within the healthcare ecosystem. For patients, clarity on these differences is crucial for navigating their out-of-pocket costs and ensuring equitable access to essential medicines, as their cost-sharing obligations are frequently tied to higher, less-adjusted list prices.14 For policymakers, a deep understanding of these dynamics is vital for developing effective legislation and regulatory frameworks that can genuinely control costs and improve drug affordability across the population.22 Similarly, for healthcare providers and payers, this knowledge is essential for informing their reimbursement strategies, making judicious formulary decisions, and managing the overall financial health of the healthcare system.5 This report seeks to provide the analytical foundation necessary to address these complexities.

Understanding Manufacturer Net Price (MNP)

Definition: The Actual Revenue Manufacturers Receive After All Deductions

Manufacturer Net Price (MNP), frequently referred to simply as “Net Price,” represents the actual revenue that a pharmaceutical manufacturer realizes from the sale of a drug after all applicable rebates, discounts, and other price reductions have been accounted for.3 It is the ultimate economic value that the manufacturer receives, reflecting the true financial outcome of their product’s sale after navigating the complex U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain.4

Significance: True Indicator of Manufacturer’s Realized Revenue

The MNP holds significant importance as it provides a far more accurate representation of a manufacturer’s true profitability and the financial impact of various pricing adjustments than any gross or list price. It is the core figure that quantifies the “gross-to-net bubble”—the substantial difference between the initial gross sales revenue (calculated based on the list price) and the final net sales revenue received by the manufacturer.1 This distinction is critical because publicly reported list prices often bear little resemblance to the actual revenue manufacturers earn, creating a misleading perception of drug costs.

Initial Insights into its Calculation Components (Rebates, Discounts, etc.)

The calculation of the net price involves a series of deductions from the initial gross revenue generated by a drug’s sale. These deductions are multifaceted and contribute to the complexity and opacity of the pharmaceutical pricing system.33 Key components of these gross-to-net adjustments include:

- Negotiated Discounts and Rebates: These are financial concessions provided by manufacturers to various entities within the supply chain, such as payers (e.g., insurance companies, PBMs), pharmacies, and wholesalers. These can be negotiated based on volume, market share, or formulary placement.33

- Chargebacks: These occur when a wholesaler sells a drug to a downstream purchaser (like a pharmacy or hospital) at a contractually agreed-upon price that is lower than the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). The wholesaler then “charges back” the manufacturer for the difference.33

- Fees: Manufacturers pay various fees to wholesalers and distributors for their services, which are deducted from the gross revenue. Additionally, bona fide service fees paid to dispensing pharmacies for patient services can also be a factor, particularly for high-touch therapies.33

- Product Returns: Units returned from wholesalers, distributors, or pharmacies due to damage, expiration, or being unsalable are also accounted for as deductions from gross revenue.33

- Other Adjustments: Changes in contracting, pricing, and reimbursement terms that occur between the initial sale to the wholesaler and the final payment by the payer for a dispensed drug can also necessitate deductions or additions to the gross revenue.33

This intricate interplay of deductions is precisely what renders the pharmaceutical pricing system so challenging to fully comprehend, as the journey from a drug’s list price to its manufacturer net price is far from straightforward.33

Key US Pharmaceutical Price References: Definitions and Uses

The U.S. pharmaceutical market employs a variety of price references, each serving distinct purposes within the complex supply chain and regulatory framework. Understanding these definitions and their relationships to the manufacturer net price is fundamental to deciphering the overall pricing puzzle.

List Price / Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC)

Definition: The Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) is the manufacturer’s published catalog or list price for a drug product when sold to wholesalers or other direct purchasers in the United States.7 It is considered the industry standard for describing the price paid by a wholesaler or distributor for drugs purchased from the manufacturer.34 Crucially, WAC explicitly does not include any prompt pay discounts, rebates, allowances, or other price concessions offered by the supplier of the product.7

Uses: WAC serves as a foundational benchmark in the pharmaceutical supply chain. It is a primary basis for price negotiations between manufacturers and downstream purchasers, including distributors and pharmacies.36 Furthermore, WAC is often referenced in formulary rebate agreements negotiated between manufacturers, health plans, and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs).36 State Medicaid programs, Medicare Part D, and commercial plans also utilize WAC in their reimbursement formulas for pharmaceuticals, typically as a percentage of WAC plus a dispensing fee.36

Analysis: The Disconnect of the “Starting Price”

The nature of WAC as a “list price” or “sticker price” that excludes any discounts or rebates 7 immediately highlights a significant disconnect between the initial reported price and the actual transaction prices that occur throughout the pharmaceutical supply chain. This means that the very starting point for pricing discussions and calculations does not reflect the true cost of the drug as it moves through the system. Consequently, all subsequent calculations and reimbursements that are based on WAC are inherently inflated or distorted. This fundamental structural characteristic directly contributes to the expansion of the “gross-to-net bubble” and fosters widespread confusion among patients, payers, and policymakers regarding the actual cost of medicines. The reliance on a gross, pre-discounted price as a primary reference point creates an illusion of higher costs, which then necessitates a complex web of adjustments to arrive at the true net price.

Average Wholesale Price (AWP)

Definition: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) is an average or “sticker price” for a drug, representing the price at which wholesalers sell prescription drugs to retail pharmacies, physicians, and other retail purchasers, prior to any discounts or concessions.5 It is a self-reported figure by manufacturers and does not necessarily reflect the actual price paid in transactions.5 AWP is generally inflated, often by as much as 20% relative to actual market prices or the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC).6 Notably, AWP is not a government-regulated price.9

Uses: AWP has historically been a commonly used benchmark for reimbursement purposes by third-party payers, including private insurance companies and government programs like Medicare and Medicaid.5 It helps these entities determine the amount they will reimburse healthcare providers for the cost of prescription drugs.5 AWP also serves as a reference point for pricing negotiations and for financial forecasting within the pharmaceutical industry.5 Despite its known unreliability and a history of litigation alleging inflated reporting, AWP has persisted as a widely used benchmark for decades due to the absence of other readily available and reliable methods for payers to obtain real market prices.6

Analysis: The “Ain’t What’s Paid” Paradox and its Systemic Impact

The common industry quip, “AWP means ‘Ain’t What’s Paid'” 36, succinctly captures the artificial nature of this pricing benchmark. The continued reliance on a benchmark known to be inflated and unreflective of actual transaction prices 5 creates profound systemic inefficiencies within the pharmaceutical supply chain. This inflated baseline provides opportunities for practices such as “spread pricing” by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), where PBMs are reimbursed by insurers based on AWP (or a discount off AWP) but pay pharmacies a lower amount, retaining the difference.13 This mechanism directly contributes to higher costs for payers and, ultimately, for patients, whose out-of-pocket cost-sharing is often calculated as a percentage of this inflated AWP-based price.6 The persistence of AWP as a primary reimbursement benchmark, despite its documented unreliability and the numerous lawsuits it has engendered 6, underscores the pervasive lack of transparency and the historical difficulty in obtaining accurate, real-world market prices in the U.S. drug distribution system. This perpetuates a system where the perceived cost is significantly higher than the actual acquisition cost for many entities in the chain.

Average Manufacturer Price (AMP)

Definition: The Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) is the average price paid to the manufacturer by wholesalers and pharmacies that purchase directly from a manufacturer for drugs subsequently sold to retail pharmacies.9 This price is defined under federal law, specifically by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1990.9 AMP reflects various price reductions, including cash discounts, volume discounts, and other adjustments to the actual price paid.10 Manufacturers are legally mandated to report AMP data for all Medicaid-covered drugs to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) on a quarterly basis, though this data is considered proprietary and is not accessible to states.10

Uses: The primary use of AMP is to calculate drug rebates under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP).9 For brand-name drugs, the Medicaid rebate amount is determined as the greater of 23.1% of the AMP or the difference between the AMP and the “Best Price” (AMP-BP).10 For generic drugs, the rebate is set at 13% of the AMP.10 The intent behind establishing AMP was to ensure that Medicaid rebates were based on the actual manufacturer prices received, rather than on potentially inflated retail prices.10 Prior to the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), AMP was used exclusively for rebate determination and not as a basis for reimbursement.10

Analysis: AMP as a Regulatory Lever for Net Price Control

The design of AMP as a federally defined metric, explicitly incorporating various discounts and reductions, positions it as a direct regulatory mechanism aimed at aligning Medicaid rebates with the actual prices manufacturers receive.10 This means AMP serves as a direct attempt to steer the price closer to a “net” figure for a specific, significant government program. The direct linkage between Medicaid rebates and AMP (alongside Best Price) means that manufacturers’ broader pricing strategies, including their gross-to-net adjustments, are significantly influenced by the need to manage their AMP to control their rebate liabilities.9 The elimination of the Medicaid rebate cap as of 2024 introduces a new dynamic, potentially incentivizing manufacturers to launch drugs at higher prices or risk paying rebates that exceed the total cost of the drug, which further complicates the strategic management of AMP.9 This demonstrates how targeted government programs can directly influence the effective net price for a specific segment of the market, thereby driving manufacturer behavior across their entire portfolio.

Best Price (BP)

Definition: Best Price (BP) is defined as the lowest price available from a manufacturer for a single source drug or innovator multiple source drug to any purchaser in the United States during a rebate period.9 This includes any wholesaler, retailer, provider, health maintenance organization (HMO), nonprofit entity, or government entity, with certain statutory exceptions.9 Best Price is legally required to reflect all applicable discounts, rebates, and other pricing adjustments.10 Specific exclusions from the Best Price calculation include prices charged to federal government entities (such as the Indian Health Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, and Public Health Service), prices negotiated under Medicare Part D, and certain manufacturer-sponsored patient programs (e.g., coupons, copay assistance) where the full value is passed directly to the consumer without any price concession to the pharmacy or other entity.41 Best Price data is reported to CMS and states but remains confidential.40

Uses: Best Price is a critical component in the calculation of Medicaid drug rebates for brand-name drugs.10 Its purpose is to ensure that the Medicaid program receives the lowest price offered by the manufacturer in the commercial market.10

Analysis: Best Price as a Floor and its Influence on Commercial Negotiations

Best Price functions as a statutory “floor” for Medicaid drug pricing, legally compelling manufacturers to extend their lowest commercial price to the Medicaid program.10 This regulatory requirement has a significant ripple effect on manufacturers’ commercial pricing strategies. If a manufacturer offers a particularly deep discount to a large commercial payer, a Group Purchasing Organization (GPO), or any other eligible entity, that discounted price could potentially become the Best Price. This, in turn, would directly increase the manufacturer’s Medicaid rebate liability for that drug across all Medicaid sales. This statutory linkage creates a strong incentive for manufacturers to meticulously manage their commercial discounts and rebate agreements. An aggressive commercial deal, while beneficial for that specific commercial purchaser, could have substantial and unintended financial consequences on the manufacturer’s government pricing obligations. This demonstrates how a specific regulatory definition, designed to protect government programs, can indirectly but powerfully shape broader commercial pricing strategies and influence the overall “net” revenue realized by manufacturers.

Average Sales Price (ASP)

Definition: Average Sales Price (ASP) represents a manufacturer’s average sales price to all purchasers, calculated net of all discounts, rebates, chargebacks, and credits applied during the sales process.9 This metric is specifically used for drugs and biologicals covered under Medicare Part B.9 ASP is determined by dividing the total revenue earned from these sales by the total units sold.9

Uses: ASP serves as the primary basis for reimbursement for drugs and biologicals administered under Medicare Part B.9 Medicare typically reimburses healthcare providers at a rate of ASP plus an additional 6%.9 CMS publishes these payment amounts on a quarterly basis, providing transparency for Part B drug pricing.12

Analysis: ASP as a Closer Proxy to Net Price for Specific Segments

Unlike the Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which is an inflated list price, ASP is explicitly defined as “net of discounts, rebates, chargebacks, and credits”.9 This fundamental difference means that ASP provides a much closer reflection of the manufacturer’s actual

net revenue for drugs covered under Medicare Part B. The additional 6% payment to providers on top of ASP 12 is intended to cover administrative and handling costs associated with acquiring and administering the drug. The adoption of ASP for Medicare Part B reimbursement demonstrates a deliberate effort by a major government program to utilize a pricing benchmark that more accurately reflects the manufacturer’s realized price. This approach aims for a more transparent and cost-effective reimbursement model compared to systems that rely on inflated list prices like AWP, thereby contributing to a more direct relationship between the manufacturer’s received price and the public’s expenditure for this segment of the market.

340B Ceiling Price

Definition: The 340B ceiling price is the maximum statutory price that a pharmaceutical manufacturer can charge a “covered entity” for the purchase of a covered outpatient drug.44 Covered entities include certain hospitals, federally qualified health centers, and other clinics that serve a disproportionate share of low-income or uninsured patients.45 The 340B ceiling price is calculated as the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) from the preceding calendar quarter for the smallest unit of measure, minus the Unit Rebate Amount (URA).44 The Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) calculates this price to six decimal places and then publishes it, rounded to two decimal places, in the 340B OPAIS (Office of Pharmacy Affairs Information System).44

Uses: The 340B Drug Pricing Program mandates that drug manufacturers participating in Medicaid must provide covered outpatient drugs to enrolled “covered entities” at or below this statutorily defined ceiling price.45 The program’s core purpose is to enable these covered entities to “stretch scarce Federal resources as far as possible,” allowing them to serve more eligible patients and provide more comprehensive services.45

Analysis: 340B as a Deep Discount Mechanism and its Systemic Tensions

The 340B program mandates a deeply discounted price (AMP minus URA) 44, which represents a significant reduction from even the AMP. This pushes the price point far closer to a true “net” for the specific set of purchasers that are covered entities. While the program’s intent is to empower safety-net providers to expand patient access 45, this deep discount creates considerable tensions and complexities within the broader pharmaceutical pricing ecosystem. Manufacturers have, for instance, challenged the program’s expansion, particularly concerning the role of contract pharmacies, which dispense 340B drugs on behalf of covered entities.46 This has led to ongoing litigation and concerns about “duplicate discounts” where Medicaid might claim rebates on drugs already sold at 340B-discounted prices.39 This dynamic highlights a policy designed to achieve extremely low net prices for a specific segment of the healthcare system, but which simultaneously generates complex financial and legal challenges across the entire supply chain, impacting manufacturers’ overall revenue streams and potentially influencing their broader list price strategies.

National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC)

Definition: The National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) represents the average price that pharmacies pay for prescription drugs.37 This data is collected through weekly surveys administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and specifically reflects the invoice prices paid by retail pharmacies.37 Unlike the Average Wholesale Price (AWP), NADAC is considered a more realistic measure, representing actual acquisition costs rather than a “fabricated and inflated value”.37

Uses: NADAC is utilized as a standard for understanding the supply and demand dynamics of prescription drugs and provides enhanced transparency and insight into drug spending.37 To mitigate monthly rate volatility, CMS has implemented a three-month moving average for calculating NADAC rates for generic drugs.47 NADAC is widely regarded as a more accurate reflection of pharmacy acquisition costs compared to AWP.37

Analysis: NADAC as a Transparency-Driven Alternative to AWP

NADAC was specifically developed by CMS to address the long-standing criticisms and inaccuracies associated with the Average Wholesale Price (AWP).37 Its foundation in actual invoice prices reported by pharmacies and its frequent, weekly updates 37 position it as a significantly more “real-world” acquisition cost for pharmacies. This provides a more transparent and less inflated benchmark for drug pricing. Evidence comparing NADAC-based drug prices with AWP highlights this distinction, showing that NADAC-based generic drug prices have significantly decreased over time, while AWP remained stagnant.37 This stark contrast underscores NADAC’s potential to drive down costs if it were more widely adopted as a benchmark for pharmacy reimbursement in commercial contracts. The development and promotion of NADAC represent a clear policy-driven effort to move towards more transparent and acquisition-cost-based pricing, which could fundamentally alter how pharmacies are reimbursed and how the “net” price is perceived and managed at the retail level.

Key Table: Comparison of US Pharmaceutical Price References

The following table summarizes the key U.S. pharmaceutical price references, illustrating their definitions, primary uses, relationships to the Manufacturer Net Price (MNP), and notable characteristics. This comparison is vital for understanding the multi-faceted nature of drug pricing in the U.S. and how various benchmarks contribute to or diverge from the actual revenue realized by manufacturers.

| Price Reference | Definition | Primary Use | Relationship to Manufacturer Net Price (MNP) | Key Characteristics & Nuances | Relevant Snippets |

| Manufacturer Net Price (MNP) | Actual revenue manufacturer receives after all rebates, discounts, and other price reductions. | True indicator of manufacturer’s realized revenue and profitability. | Directly represents MNP. | The actual economic value realized by the manufacturer. The core of the “gross-to-net bubble.” | 3 |

| Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) | Manufacturer’s published list price to wholesalers/direct purchasers, before any concessions. | Basis for price negotiations; used in some reimbursement formulas. | Typically significantly higher than MNP; the “starting price” before deductions. | Does not include discounts/rebates. Industry standard for wholesaler purchase price. Contributes to gross-to-net bubble. | 7 |

| Average Wholesale Price (AWP) | “Sticker price” for drug sold by wholesalers to retail pharmacies/providers, before concessions. | Primary benchmark for third-party payer reimbursement; pricing reference. | Typically inflated and much higher than MNP; often 20% above WAC. | Self-reported, not government-regulated. Subject to manipulation and litigation (“Ain’t What’s Paid”). Enables “spread pricing.” | 5 |

| Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) | Average price paid to manufacturer by wholesalers/direct-purchasing pharmacies for drugs sold to retail pharmacies; includes cash/volume discounts. | Calculates drug rebates under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP). | Closer to MNP than WAC/AWP, as it accounts for some reductions. | Federally defined. Proprietary data. A regulatory lever for net price control for Medicaid. | 9 |

| Best Price (BP) | Lowest manufacturer price to any purchaser (with exceptions); reflects all discounts/rebates. | Critical component in calculating Medicaid drug rebates for brand-name drugs. | Represents the lowest possible MNP for any commercial transaction (with exclusions). | Statutory “floor” for Medicaid pricing. Confidential. Influences commercial negotiation strategies. | 9 |

| Average Sales Price (ASP) | Manufacturer’s average sales price to all purchasers, net of discounts, rebates, chargebacks, credits. | Basis for Medicare Part B drug/biological reimbursement (ASP + 6%). | Directly reflects MNP for Medicare Part B drugs. | Published quarterly by CMS. Aims for more transparent, acquisition-cost-based reimbursement. | 9 |

| 340B Ceiling Price | Maximum statutory price a manufacturer can charge a “covered entity” (AMP – URA). | Mandated price for covered outpatient drugs under the 340B Drug Pricing Program. | Represents a deeply discounted MNP for specific safety-net providers. | Designed to stretch federal resources. Creates systemic tensions and challenges (e.g., duplicate discounts). | 44 |

| National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) | Average price pharmacies pay for prescription drugs, based on actual invoice prices. | Standard for supply/demand; provides transparency into pharmacy acquisition costs. | Reflects the pharmacy’s acquisition cost, which is downstream from MNP. | Developed by CMS to be more accurate than AWP. Weekly updates. Potential for driving down costs if widely adopted. | 37 |

The Gross-to-Net Bubble: Mechanisms and Impact

Defining the Gross-to-Net Bubble

The “gross-to-net bubble” is a term coined to describe the ever-widening financial gap between the list prices of brand-name drugs and the actual net revenues that manufacturers ultimately receive after accounting for all rebates, discounts, and other price reductions.1 This terminology is used to characterize the rapid speed and significant size of the growth in the total dollar value of manufacturers’ gross-to-net reductions.1 In 2024, the total value of these gross-to-net reductions for all brand-name drugs reached an estimated $356 billion.1 While this marked a record total, the bubble expanded at its slowest rate in at least a decade (7% increase over the previous year), suggesting a potential shift in underlying dynamics.1

Major Components of Gross-to-Net Adjustments

The substantial difference between a drug’s list price and its manufacturer net price is a result of numerous adjustments throughout the supply chain. These adjustments are complex and often opaque, contributing to the “gross-to-net bubble.” The primary components include:

- Rebates: These are retrospective discounts provided by pharmaceutical manufacturers to payers, primarily Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and insurance companies. Rebates are often tied to specific conditions, such as securing preferred formulary placement, achieving certain sales volumes, or meeting performance criteria.33 Rebates are the largest and most significant component of gross-to-net price differences.1 While intended to reduce net costs for payers, they can inadvertently contribute to higher list prices, as manufacturers may raise list prices to accommodate larger rebate demands.49

- Discounts and Allowances: These encompass various negotiated price reductions, such as volume-based discounts for large purchases, prompt payment discounts, and other contractual allowances provided to wholesalers, pharmacies, or other entities.33 These are direct reductions from the gross price at the point of sale or retrospectively.

- Chargebacks: This mechanism involves price adjustments where a wholesaler sells a drug to a downstream purchaser (e.g., a hospital or pharmacy) at a contractually agreed-upon price that is lower than the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). The wholesaler then claims the difference from the manufacturer as a chargeback.33

- Fees: Manufacturers pay various fees to entities within the supply chain for services rendered. This includes fees to wholesalers and distributors for their logistical and inventory management services, as well as bona fide service fees paid to dispensing pharmacies for specific patient services, particularly for high-touch therapies.33

- Product Returns: Deductions are made from gross revenue for units of product returned from wholesalers, distributors, or pharmacies that are damaged, expired, or otherwise unsalable.33

- Program Discounts: Significant price reductions are mandated by government programs, such as the 340B Drug Pricing Program, which provides deeply discounted drugs to eligible covered entities, and the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, which requires manufacturers to pay rebates to states.1 Future Medicare price negotiations under the Inflation Reduction Act will also contribute to these reductions.1

Impact on Stakeholders

The gross-to-net bubble has profound and often disparate impacts across various stakeholders in the pharmaceutical ecosystem:

- Manufacturers: For manufacturers, the gross-to-net bubble means that their realized revenue is substantially lower than the list prices they set. This necessitates complex financial management and strategic decisions regarding the balance between list price increases and the depth of rebates offered.1 The existence of this bubble means manufacturers earn significantly less revenue than list prices suggest, creating a challenge in communicating their true financial position and the actual cost of innovation.1

- Patients: Patients are disproportionately affected by the gross-to-net bubble because their out-of-pocket costs (e.g., co-insurance, deductibles) are frequently tied to the higher, undiscounted list prices, not the lower net prices after rebates.14 This can lead to significant affordability issues, forcing patients to resort to strategies like cutting pills in half, skipping doses, or not filling prescriptions altogether due to cost.23 Such non-adherence can result in poorer health outcomes and increased financial hardship for individuals.24

- Payers (Insurers, PBMs): PBMs negotiate substantial rebates from manufacturers, which are intended to reduce the net cost of pharmaceuticals for the health plans and employers they serve. While PBMs do pass a portion of these rebates to plan sponsors (e.g., 91% to commercial insurers), they also retain a significant share, often through practices like “spread pricing”.13 This can create a situation where PBMs have a financial incentive to favor drugs with higher list prices and larger rebates, even if lower-cost therapeutic alternatives exist, which can lead to higher overall drug spending and patient costs.13

- Wholesalers & Pharmacies: Wholesalers purchase drugs from manufacturers (often at a discount off WAC) and then mark up the price before selling to pharmacies.55 Pharmacies, in turn, set their cash prices, often based on an inflated Average Wholesale Price (AWP) plus a dispensing fee.32 When patients use insurance, pharmacies are reimbursed by PBMs or insurers based on negotiated contracts, which are typically the lowest of the pharmacy’s usual/customary fee, a contracted rate (often AWP-based), or a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) for generics.32 This system incentivizes pharmacies to set high cash prices to avoid receiving lower reimbursement if their usual and customary price falls below the contracted rate, further contributing to high out-of-pocket costs for uninsured or high-deductible patients.32

Case Studies: List Price vs. Net Price Discrepancies

Several prominent examples highlight the significant discrepancies between list prices and manufacturer net prices in the U.S. pharmaceutical market:

- Insulin: A study analyzing 32 insulin products between 2014 and 2018 found that while the manufacturer list price increased by 40.1%, the net price actually decreased by an average of 30.8%.58 This divergence was attributed to the increasing discounts negotiated within the supply chain. In a notable recent development, major insulin manufacturers like Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk announced substantial reductions in the list prices of their insulin products (by 70% and 75% respectively for Humalog and NovoLog).58 This strategic move aimed to directly transfer a significant portion of the discount from PBMs to patients, as patient cost-sharing obligations are typically tied to the higher list prices.58

- Humira: Humira (adalimumab) has long been known for its high cost, with a carton of two subcutaneous kits costing over $8,000 per month without insurance.59 The introduction of biosimilar alternatives to Humira has brought about significant price competition. For example, Blue Shield of California announced it would purchase an FDA-approved Humira biosimilar for a transparent net price of $525 per monthly dose, a stark contrast to Humira’s market-reported net price of $2,100.60 This illustrates how competition can drive net prices down, even for complex biologic drugs.

- Medicare Part D Negotiated Drugs (Inflation Reduction Act): The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 granted Medicare the authority to negotiate drug prices for certain high-expenditure drugs, with the first 10 negotiated prices for Part D drugs taking effect in 2026.19 For these initial 10 drugs, the negotiations resulted in discounts ranging from 38% to 79% off their list prices.61 This direct government intervention demonstrates a powerful mechanism to reduce the gross-to-net gap and lower costs for Medicare beneficiaries, directly impacting the manufacturer’s realized net price for these specific drugs.61

Analysis: The Gross-to-Net Bubble’s Systemic Effects

The gross-to-net bubble is not merely an accounting phenomenon; it is a fundamental structural characteristic of the U.S. pharmaceutical market that creates a distorted economic environment. The maintenance of high list prices, while allowing for substantial rebates, enables PBMs to negotiate large concessions, which can then incentivize them to favor those high-list-price drugs for formulary placement.13 This opacity fundamentally obscures the true cost of medications, making it exceedingly difficult for consumers and policymakers to understand where the money flows and who benefits. The system effectively shifts a significant portion of the financial burden to patients, whose out-of-pocket costs are often calculated based on these inflated list prices, even as the manufacturer receives a much lower net price.14 This lack of transparency also hinders effective price comparison and competition.

The recent observation of a slower growth rate in the gross-to-net bubble 1 is a notable development. This deceleration is linked to significant policy changes, such as the elimination of the Medicaid rebate cap by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, and the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).1 These regulatory shifts, coupled with evolving market access strategies by manufacturers (e.g., voluntarily lowering list prices for highly rebated products), are beginning to reshape the incentives within the system.1 This suggests a potential, albeit gradual, movement towards more transparent pricing models and a narrowing of the gap between list and net prices, driven by both legislative pressure and strategic adaptations from manufacturers.

The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain and Flow of Funds

The U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain is a complex ecosystem involving multiple interconnected parties, each playing a distinct role in the journey of a drug from manufacturer to patient. Understanding the flow of products and, critically, the flow of money through this chain is essential to grasping the intricacies of pharmaceutical pricing.

Key Players and Their Interrelationships

The primary entities involved in the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain include:

- Drug Manufacturers: These are the originators and producers of pharmaceutical products. They are responsible for setting the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC), which serves as the baseline price for their products.63 Manufacturers engage in formulary agreements with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) to ensure their drugs are covered by insurance plans, and they establish distribution agreements with wholesalers.64

- Wholesalers (Distributors): Wholesalers act as crucial intermediaries, purchasing bulk drugs from manufacturers (often at negotiated discounts off WAC).56 They manage vast inventories and are responsible for the physical distribution of these products to pharmacies and hospitals across the country.55 Wholesalers typically apply a markup to the prices before selling to pharmacies.56

- Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): PBMs are central to the financial flow of prescription drugs. They negotiate rebates and discounts with drug manufacturers on behalf of health plans and employers, manage drug formularies (lists of covered drugs), process pharmacy claims, and reimburse pharmacies for dispensed medications.13 PBMs also establish network agreements with pharmacies and formulary agreements with manufacturers.64

- Pharmacies: Pharmacies acquire drugs from wholesalers and are the final point of dispensing to consumers.32 They set their cash prices, often based on the Average Wholesale Price (AWP) plus a dispensing fee.32 When patients use insurance, pharmacies are reimbursed by PBMs or insurers based on their contractual agreements, typically the lowest of their usual and customary fee, a contracted rate (often AWP-based), or a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) for generics.32 Pharmacies also have prime vendor agreements with distributors and network agreements with PBMs.64

- Payers (Insurers, Employers, Government Programs): These entities contract with PBMs to manage prescription drug benefits for their members or beneficiaries.13 They receive a share of the manufacturer rebates negotiated by PBMs and reimburse PBMs for their services. Consumers pay premiums to these payers.64

- Consumers/Patients: As the end-users of prescription drugs, consumers pay premiums to their payers and copayments or deductibles directly to pharmacies for dispensed medications.14 They ultimately bear the financial impact of the pricing structure, particularly the high list prices through their cost-sharing obligations.14

Complex Financial Flows and Rebate Dynamics

The U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain is characterized by distinct, often disconnected, flows of product and money, contributing significantly to its complexity and opacity.

- Product Flow: The physical movement of drugs is relatively straightforward: Drug manufacturers ship bulk drugs to distributors, who then ship them to pharmacies, and finally, pharmacies dispense the drugs to consumers.64

- Money Flow (Simplified): The financial flow is considerably more intricate. Consumers pay premiums to their payers (e.g., insurance companies) and copayments directly to pharmacies.64 Payers, in turn, reimburse Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), who then provide payment to pharmacies for dispensed drugs.64 Pharmacies pay distributors for wholesale drugs, and distributors, in turn, pay drug manufacturers.64

- Rebate Flow: A critical and often misunderstood aspect is the flow of rebates. Manufacturers pay rebates directly to PBMs, and these rebates do not flow through the wholesale or retail pharmacy channels.64 PBMs then share a portion of these rebates with plan sponsors (payers), which helps to reduce the net prescription costs for those plans.66 However, PBMs also retain a significant portion of these rebates as revenue.13

Analysis: The “Rube Goldberg Machine” of Drug Payments

The U.S. pharmaceutical financial system has been likened to a “Rube Goldberg machine” due to its deliberately over-engineered and convoluted nature to perform a seemingly simple task: getting a drug from manufacturer to patient.66 This complexity, particularly the separation of the product flow from the rebate money flow, creates a system where the “sticker price” is almost never the “paid price” for the manufacturer. This structural characteristic leads to profound opacity, making it exceedingly difficult to trace the true cost of a drug at any given point in the chain. The convoluted financial pathways allow various intermediaries, notably PBMs, to capture significant value through practices like spread pricing, where they retain the difference between what they charge insurers and what they reimburse pharmacies.13

The fact that manufacturer rebates do not flow through the traditional retail channel has a direct and detrimental impact on patients. Since patients’ out-of-pocket costs (e.g., co-insurance, deductibles) are often calculated based on the higher list price, they do not directly benefit from the substantial rebates negotiated by PBMs.14 This disconnect exacerbates affordability issues for consumers, as they pay a share of a price that is significantly higher than what the manufacturer ultimately receives, contributing to widespread frustration and financial hardship. This intricate and opaque financial architecture is a primary driver of the “pharmaceutical pricing puzzle.”

Factors Influencing Pharmaceutical Pricing and the Net Price

The determination of pharmaceutical prices in the U.S. is influenced by a dynamic interplay of economic, market, and regulatory factors. These elements collectively shape not only the initial list prices but also the eventual manufacturer net prices.

Economic and Market Dynamics

- Research and Development (R&D) Costs: Pharmaceutical companies frequently assert that the substantial investment in R&D is a primary justification for high drug prices, necessary to recoup the years of research, rigorous clinical trials, and complex regulatory approval processes.15 Estimates for bringing a new drug to market range from $1 billion to $3 billion.67 However, independent studies have challenged this direct correlation, finding no consistent link between a drug’s R&D costs and its launch price or subsequent pricing.67 This suggests that companies often price drugs based on “what the market will bear” rather than solely on R&D expenditure.67 This creates a fundamental tension: while R&D is undeniably costly, the industry’s pricing practices do not always directly reflect these costs, leading to public scrutiny and debates about pricing fairness.68

- Market Exclusivity (Patents & Regulatory Exclusivities): Intellectual property (IP) rights, primarily patents and regulatory exclusivities granted by the FDA, are critical determinants of pricing power.15 These rights grant manufacturers a temporary monopoly, allowing them to charge higher-than-competitive prices for a period ranging from six months to up to 12 years.17 This exclusivity is intended to incentivize innovation and allow companies to recoup R&D investments.17 However, critics argue that certain patenting practices, such as “evergreening” (filing new patents on secondary features as earlier ones expire) or “patent thickets” (accumulating numerous overlapping patents), unduly extend these periods of exclusivity.17 This delays the entry of lower-cost generic and biosimilar competition, thereby contributing to persistently high drug prices.17

- Competition (Generics & Biosimilars): The entry of generic and biosimilar competitors is the most significant factor in driving down drug prices.15 Studies consistently demonstrate that drug prices fall substantially with an increasing number of generic competitors. For instance, prices can decline by 20% in markets with approximately three competitors and by 70% to 80% relative to the pre-generic entry price in markets with 10 or more competitors after three years.18 Policies that support and accelerate the entry of lower-priced generics and biosimilars are therefore crucial for enhancing affordability and patient access.18

- Drug Efficacy and Perceived Therapeutic Value: The effectiveness and perceived value of a drug significantly influence its pricing potential.15 Drugs that offer substantial clinical benefits, such as saving or extending lives, reducing the need for expensive hospital visits or surgeries, or providing significant therapeutic advances over existing treatments, can command higher prices.15 Value-based pricing models, which link a drug’s price to its clinical outcomes and overall value to patients and the healthcare system, are an emerging strategy that aims to align cost with tangible health improvements.72

- Consumer Price Sensitivity & Brand Value: Pharmaceutical companies also consider consumer price sensitivity, including patient demographics, income levels, insurance coverage, and willingness to pay for premium medications.15 The brand reputation and trust associated with a well-established pharmaceutical company can also allow it to charge higher prices, as patients and physicians may prefer a reputable brand even if similar, lower-cost alternatives exist.15

Regulatory and Policy Landscape

The U.S. pharmaceutical pricing landscape is increasingly shaped by a dynamic and evolving regulatory and policy environment at both federal and state levels.

- Federal Initiatives:

- Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022: This landmark legislation represents a significant shift in federal drug pricing policy. It mandates that the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) negotiate prices for certain high-cost drugs covered under Medicare Part D (starting in 2026) and Part B (starting in 2028).19 The IRA also imposes “inflation rebates,” requiring drug companies to pay rebates to Medicare if their drug prices rise faster than the rate of inflation for drugs used by Medicare beneficiaries.20 Furthermore, the Act introduces an annual out-of-pocket spending cap of $2,000 for Medicare Part D enrollees starting in 2025, and caps monthly insulin costs at $35.16 These provisions are designed to lower costs for Medicare beneficiaries and reduce federal drug spending, marking a direct intervention into pricing previously left to market forces.19

- Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) Pricing: Recent executive orders have aimed to align U.S. drug prices with the lower prices paid in other developed nations, often referred to as “most-favored-nation” pricing.76 These initiatives seek to address the perceived “global freeloading” where other countries benefit from deeply discounted drug prices while the U.S. pays significantly more.78

- State-Level Initiatives:

- Drug Price Transparency Laws: Over a dozen U.S. states have enacted drug price transparency laws, starting with Vermont in 2016.22 These laws require various entities in the supply chain, including manufacturers, PBMs, health plans, and wholesalers, to report information on drug pricing. This includes reporting on Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) increases or high launch prices for new drugs.22 The goal is to shed light on opaque pricing practices, establish accountability for price increases, and provide data infrastructure for policy solutions.22

- Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs): Building on transparency efforts, some states have established Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs).22 These regulatory bodies are empowered to review high-cost drugs and, in certain states, to set upper payment limits to ensure that consumers do not pay more than a specified amount.22 PDABs leverage the data collected through state transparency programs to identify drugs for review and inform their decisions.22

Analysis: The Shifting Regulatory Tides and Their Influence on Net Price

The recent federal and state policy interventions signify a growing governmental intent to address high drug prices and the opacity of the gross-to-net bubble. The Inflation Reduction Act’s provisions for Medicare drug price negotiation and inflation rebates directly target the dynamics of the gross-to-net gap by exerting downward pressure on manufacturer net prices for a significant portion of the market.1 Similarly, state-level transparency laws, while not directly setting prices, expose the magnitude of the gross-to-net difference and create public accountability for price increases and high launch prices.22 This increased scrutiny can compel manufacturers to reconsider their list price strategies or rebate practices to avoid negative public perception or regulatory attention. These policy shifts are beginning to fundamentally reshape the incentives for pharmaceutical manufacturers, potentially leading to a “popping” or at least a deceleration in the growth of the gross-to-net bubble by narrowing the long-standing gap between list and net prices. The increasing regulatory oversight aims to drive greater price efficiency and transparency throughout the supply chain.

Conclusion

The U.S. pharmaceutical pricing landscape remains a complex and often perplexing puzzle, primarily characterized by a substantial and growing “gross-to-net bubble.” This phenomenon, where the initial list prices of drugs diverge significantly from the actual net revenues manufacturers realize after accounting for a myriad of rebates, discounts, and fees, creates a system fraught with opacity and inefficiency. Key price references like WAC and AWP, while widely used, often serve as inflated benchmarks that do not reflect true transaction costs, contributing to systemic distortions. Conversely, metrics like AMP, Best Price, and ASP, while closer to manufacturer net prices, serve specific regulatory or reimbursement purposes, highlighting the fragmented nature of pricing transparency.

This intricate system, involving a complex web of manufacturers, wholesalers, PBMs, pharmacies, payers, and patients, leads to convoluted financial flows where rebates often bypass the direct retail channel. This structural design means that patients, whose out-of-pocket costs are typically tied to higher list prices, disproportionately bear the burden of the gross-to-net gap. This results in significant affordability challenges, leading to medication non-adherence, adverse health outcomes, and considerable financial hardship for many Americans.

However, the landscape is in a state of dynamic evolution. Growing public and political pressure has spurred significant regulatory interventions, notably the Inflation Reduction Act at the federal level and an increasing number of state-level transparency laws and Prescription Drug Affordability Boards. These policies are designed to exert downward pressure on prices, enhance accountability, and increase transparency across the supply chain. The IRA’s provisions for Medicare drug price negotiation and inflation rebates directly target the gross-to-net dynamics, aiming to reduce the gap between list and net prices for a substantial portion of the market. Similarly, state transparency efforts are shedding light on previously hidden pricing practices, potentially influencing manufacturers’ strategic decisions regarding list prices and rebate offerings.

The ongoing tension between fostering pharmaceutical innovation and ensuring affordable access to essential medicines continues to define the U.S. market. While economic factors such as R&D costs, market exclusivity, and competition profoundly influence pricing, the increasing regulatory scrutiny and the emergence of new market dynamics (e.g., lower-list-price biosimilars, direct-to-patient models) suggest a gradual, yet significant, shift towards a more transparent and potentially more equitable pricing environment. The “puzzle” of pharmaceutical pricing is far from solved, but the analytical tools and policy levers now in play offer a pathway toward greater clarity and improved affordability for patients.

Works cited

- Gross-to-Net Bubble Hits $356B in 2024—But … – Drug Channels, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/07/gross-to-net-bubble-hits-356b-in.html

- Pharmaceutical Gross-to-Net Bubble Reaches $356 Billion in 2024 Amid Slowest Growth in a Decade – GeneOnline, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/pharmaceutical-gross-to-net-bubble-reaches-356-billion-in-2024-amid-slowest-growth-in-a-decade/

- Terms of the Game | TruthinRx, accessed July 25, 2025, https://truthinrx.org/terms-game

- Inflation-Adjusted U.S. Brand-Name Drug Prices Fell for the Seventh Consecutive Year as a New Era of Drug Pricing Dawns – Drug Channels, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/01/inflation-adjusted-us-brand-name-drug.html

- Average Wholesale Price (AWP) | Definitive Healthcare, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.definitivehc.com/resources/glossary/average-wholesale-price

- Average wholesale price – Wikipedia, accessed July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Average_wholesale_price

- Changes in the List Prices of Prescription Drugs, 2017 … – HHS ASPE, accessed July 25, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/0cdd88059165eef3bed1fc587a0fd68a/aspe-drug-price-tracking-brief.pdf

- 2024 Gross-to-Net Realities at 9 Top Drugmakers: A … – Drug Channels, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/07/2024-gross-to-net-realities-at-9-top.html

- Glossary of Drug Pricing Terms | PCMA – Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.pcmanet.org/glossary-of-drug-pricing-terms/

- [Box], What Is the AMP? – Medicaid Payment for Generic Drugs – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560328/box/ib839.box2/?report=objectonly

- Average manufacturer price (AMP) | Definitive Healthcare, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.definitivehc.com/resources/glossary/average-manufacturer-price

- Medicare Part B Drug Average Sales Price – CMS, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-for-service-providers/part-b-drugs/average-drug-sales-price

- PBM Regulations on Drug Spending | Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending

- How PBMs Are Driving Up Prescription Drug Costs – The New York Times, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.nacds.org/pdfs/PBMarticle-6-21-24.pdf

- 8 Factors Affecting Drug Prices and How to Get Them Right, accessed July 25, 2025, https://unimrkthealth.com/blog/8-factors-affecting-drug-prices-and-how-to-get-them-right/

- How Pharmaceutical Companies Price Their Drugs in the U.S., accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/020316/how-pharmaceutical-companies-price-their-drugs.asp

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing …, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic … – HHS ASPE, accessed July 25, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- FAQs about the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare Drug Price … – KFF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/faqs-about-the-inflation-reduction-acts-medicare-drug-price-negotiation-program/

- Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act Any Relief of Financial Hardship for Patients With Cancer?, accessed July 25, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10550564/

- Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act – KFF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/

- Drug Price Transparency Laws Position States to Impact Drug Prices …, accessed July 25, 2025, https://nashp.org/drug-price-transparency-laws-position-states-to-impact-drug-prices/

- The truth behind drug prescription pricing – American Medical Association, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.ama-assn.org/health-care-advocacy/federal-advocacy/truth-behind-drug-prescription-pricing

- Drug Prices and Shortages Jeopardize Patient Access to Quality Hospital Care | AHA News, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.aha.org/news/blog/2024-05-22-drug-prices-and-shortages-jeopardize-patient-access-quality-hospital-care

- Public Opinion on Prescription Drugs and Their Prices – KFF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/public-opinion-on-prescription-drugs-and-their-prices/

- Drug Costs and Their Impact on Care | Arnold Ventures, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.arnoldventures.org/stories/drug-costs-and-their-impact-on-care

- U.S. drug prices are 278% higher than 33 other countries, report shows, accessed July 25, 2025, https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2024/02/u-s-drug-prices-are-278-higher-than-33-other-countries-report-shows/

- Pricing & Reimbursement Laws and Regulations 2024 | USA – Global Legal Insights, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/pricing-reimbursement-laws-and-regulations/usa/

- The impact of pharmaceutical rebates on patients’ drug expenditures – PMC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6422779/

- List Price vs Net Price – Novo Nordisk, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.novonordisk-us.com/content/dam/nncorp/us/en_us/homepage/perspectives/our-perspectives-on-pricing-and-affordability/List_vs_Net.pdf

- US Pharmaceutical Pricing Policies – OHE – Office of Health Economics, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.ohe.org/education-hub/academy/us-pharmaceutical-pricing-policies/

- How Does Drug Pricing Work in the US? – GoodRx, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.goodrx.com/hcp-articles/providers/how-does-drug-pricing-work-in-the-us

- What Does Gross to Net (GTN) Mean for Drugs? | Magnolia Market …, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.magnoliamarketaccess.com/what-does-gross-to-net-mean-for-drugs/

- Wholesale Acquisition Cost, accessed July 25, 2025, https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/html-attachments/h_hi_2019a_02202019_020347_pm_committee_summary/190220%20AttachC.pdf

- Definition: wholesale acquisition cost from 42 USC § 1395w-3a(c)(6) – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/definitions/uscode.php?def_id=42-USC-1456693790-604647169

- AWP (Average Wholesale Price) and WAC (Wholesale Acquisition Cost): What You Need to Know – American Conference Institute, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.americanconference.com/drug-pricing/wp-content/uploads/sites/2103/2024/11/Nov-4-Drug-Pricing-AWP-and-WAC.pdf

- What is NADAC & How Does It Differ From AWP? – Capital Rx, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.cap-rx.com/insights/what-is-nadac-how-does-it-differ-from-awp

- Medicaid Pricing and Rebates 2.0 Complexities and Challenges, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.americanconference.com/drug-pricing/wp-content/uploads/sites/2103/2023/10/10.30.2023-345pm_Medicaid-Pricing-and-Rebate-2.0.pdf

- Navigating Medicaid Drug Rebate … – The Healthcare Lawyers, accessed July 25, 2025, https://the-healthcare-lawyers.com/news-publication/navigating-medicaid-drug-rebate-program-mdrp-compliance-a-guide-for-pharmaceutical-manufacturers/

- Untitled – Healthcare Value Hub, accessed July 25, 2025, https://archive.healthcarevaluehub.org/download_file/view/619/1758

- 42 CFR § 447.505 – Determination of best price. – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/42/447.505

- 42 CFR 447.505 — Determination of best price. – eCFR, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-IV/subchapter-C/part-447/subpart-I/section-447.505

- A Methodology for Estimating Medicaid and Non-Medicaid Net Prices Using Top Brand-Name Drugs, 2015–2019 – Urban Institute, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/A%20Methodology%20for%20Estimating%20Medicaid%20and%20Non-Medicaid%20Net%20Prices%20Using%20Top%20Brand-Name%20Drugs.pdf

- What is the difference between the 340B ceiling price and package …, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.hrsa.gov/about/faqs/what-difference-between-340b-ceiling-price-package-adjusted-price-which-are-both-published-340b

- 340B Glossary of Terms, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.340bpvp.com/Documents/Public/340B%20Tools/340b-glossary-of-terms.pdf

- Selected Issues in Pharmaceutical Drug Pricing | Congress.gov …, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12272

- Pharmacy Pricing – Medicaid, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/pharmacy-pricing

- Key Terms in Pharmaceutical Government Pricing – Prescription Analytics Inc., accessed July 25, 2025, https://prescriptionanalytics.com/white-paper/key-terms-in-pharmaceutical-government-pricing/

- Pharmaceutical Rebates: Their Impact and Value Explained – incentX, accessed July 25, 2025, https://incentx.com/blog/pharmaceutical-rebates/

- incentx.com, accessed July 25, 2025, https://incentx.com/blog/pharmaceutical-rebates/#:~:text=The%20immediate%20financial%20effect%20of,overall%20drug%20spend%20and%20costs.

- Optimizing Pharma Gross To Net Calculations: Strategies For Profitability | by Aman dubey, accessed July 25, 2025, https://medium.com/@amandubey_6607/optimizing-pharma-gross-to-net-calculations-strategies-for-profitability-a7443a06b67d

- Accounting Pricing Adjustment Wholesaler Acquisition Cost Profit-Sharing Gross-to-Net, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.eisneramper.com/insights/technology/pricing-adjustment-gross-to-net-cat-0318/

- Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs – KFF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/americans-challenges-with-health-care-costs/

- PBMs & Middlemen – PhRMA, accessed July 25, 2025, https://phrma.org/policy-issues/pbms-middlemen

- The High Cost of Access: Fact or Fiction? – AmerisourceBergen, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.amerisourcebergen.com/brand-stories/mythbusting-the-high-cost-of-access

- Following the Money: Untangling U.S. Prescription Drug Financing …, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/following-the-money-untangling-u-s-prescription-drug-financing/

- What Is the Price Anyway? – The Actuary Magazine, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/what-is-the-price-anyway/

- Insulin: Uneven Progress Toward Affordability | Drug Pricing Explained, accessed July 25, 2025, https://drugpricing.norc.org/content/rx-supplychain/us/en/playbooks/insulin.html

- Humira cost savings and tips – SingleCare, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.singlecare.com/blog/humira-cost/

- Blue Shield of California Slashes Cost of World’s Best-Selling Drug, accessed July 25, 2025, https://news.blueshieldca.com/2024/10/01/blue-shield-of-california-slashes-cost-of-worlds-best-selling-drug

- IRA Research Series – Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program – HHS ASPE, accessed July 25, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3e8abec86039ac0ed674a8c5fac492e3/price-change-over-time-brief.pdf

- Estimated discounts generated by Medicare drug negotiation in 2026 – PMC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10397328/

- Follow The Pill: Understanding the U.S. Commercial Pharmaceutical Supply Chain – Report – KFF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/follow-the-pill-understanding-the-u-s-commercial-pharmaceutical-supply-chain-report.pdf

- Prescription Drugs: Flowchart Text Version | ASPE, accessed July 25, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/prescription-drugs-flowchart-text-version

- The Role of Health Insurance Providers in Keeping Prescriptions Affordable – NAIC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/call_materials/AHIP%20NAIC%20PBM%20WG_10.24.22_1.pdf

- Follow the Dollar: The U.S. Pharmacy Distribution … – Drug Channels, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2016/07/follow-dollar-us-pharmacy-distribution.html

- High R&D Isn’t Necessarily Why Drugs Are So Expensive, accessed July 25, 2025, https://today.ucsd.edu/story/high-rd-isnt-necessarily-why-drugs-are-so-expensive

- Do R&D costs justify the price of drugs? Nope, new study says | PharmaVoice, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.pharmavoice.com/news/rd-costs-justify-price-drugs-BMJ/643774/

- Prescription Drug Costs | Pros, Cons, Debate, Arguments, Economy, Laws, Government, & Regulation | Britannica, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/procon/prescription-drug-costs-debate

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Generic Competition and Drug Prices | FDA, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/generic-competition-and-drug-prices

- Value-Based Pricing in Pharma – Number Analytics, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ultimate-guide-value-based-pricing-drug-development

- Decoding Drug Pricing Models: A Strategic Guide to Market Domination – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/decoding-drug-pricing-models-a-strategic-guide-to-market-domination/

- International Experience in Therapeutic Value and Value-Based Pricing: A Rapid Review of the Literature – ResearchGate, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343038225_International_Experience_in_Therapeutic_Value_and_Value-Based_Pricing_A_Rapid_Review_of_the_Literature

- Inflation Reduction Act Research Series – HHS ASPE, accessed July 25, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ee9b0f2bf15e69d7e3c7ca7618eaa2af/projecting-impact-part-d.pdf

- Drug Pricing FDA Considerations Under Recent Executive Orders and Congressional Bills, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.lw.com/en/insights/drug-pricing-fda-considerations-under-recent-executive-orders-and-congressional-bills

- A Federal Update on Prescription Drug Policy – Minnesota.gov, accessed July 25, 2025, https://mn.gov/commerce-stat/insurance/pdab/07-08-2025/portal_mn_pdab_federal_drug_pricing_update_7.8.25.pdf

- Delivering Most-Favored-Nation Prescription Drug Pricing to American Patients, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/05/delivering-most-favored-nation-prescription-drug-pricing-to-american-patients/

- State Drug Transparency Laws — 2025 Update | Insights & Resources – Goodwin, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/06/alerts-lifesciences-state-drug-transparency-laws