Executive Summary: Unlocking the Multi-Billion Dollar Potential of Drug Repositioning

Drug repositioning, often referred to as drug repurposing, is rapidly transforming the pharmaceutical landscape, offering a compelling and increasingly vital alternative to traditional de novo drug discovery. This innovative strategy involves leveraging existing, approved, or previously investigated drugs for new therapeutic indications, thereby significantly reducing the time, cost, and inherent risks associated with bringing novel therapies to market . For pharmaceutical companies and business professionals navigating the complexities of modern drug development, this approach is not merely about efficiency; it represents a profound opportunity for competitive advantage and substantial profit maximization.

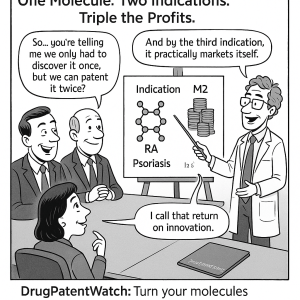

By identifying novel uses for molecules with established safety profiles, organizations can strategically extend patent life, expand their market reach, and unlock significant new revenue streams . The economic impact of this paradigm shift is already evident: the global drug repurposing market was valued at an impressive $34.08 billion in 2024 and is projected to surge to $53.69 billion by 2033, underscoring its substantial and growing economic importance. This trajectory highlights the potential for a single molecule to generate multiple revenue streams, effectively delivering “triple the profits” from existing assets. This transformation is being propelled by remarkable advancements in computational methodologies, particularly artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), alongside sophisticated preclinical models such as organ-on-a-chip technology and CRISPR screening. Furthermore, a strategic understanding of intellectual property (IP) and adept navigation of regulatory pathways are proving critical in harnessing this immense potential .

1. The Strategic Imperative: Why Drug Repositioning is Reshaping Pharma

The pharmaceutical industry constantly seeks innovative pathways to deliver life-changing therapies to patients while ensuring sustainable growth and profitability. In this dynamic environment, drug repositioning has emerged as a strategic imperative, fundamentally altering the traditional drug discovery and development paradigm.

1.1. Defining Drug Repositioning: A New Horizon for Existing Assets

At its core, drug repositioning, also known as drug repurposing, reprofiling, or re-tasking, represents a sophisticated drug discovery strategy. It involves taking an existing drug—one that has already received regulatory approval for a specific disease or has been extensively investigated—and utilizing it as a therapeutic agent for an entirely different disease or a novel indication . This process is akin to “widening a drug’s use for more than one indication”.

The scope of this strategy extends beyond merely identifying new therapeutic applications. It also encompasses the development of different formulations for the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), or the creation of novel combinations of existing medicines, sometimes even integrating them with medical devices. A particularly compelling aspect of this approach is “drug rescue,” which offers a “second chance” to compounds that may have failed in their original development pathway due to insufficient efficacy but demonstrated a robust safety profile. The increasing appeal of drug repositioning stems from its inherent advantages: it offers a “rapid, cost-effective, and reduced-risk strategy” when compared to the protracted and expensive traditional de novo drug discovery process .

The fundamental advantage of this approach lies in its de-risked foundation. Traditional drug discovery faces exceptionally high attrition rates, with a significant number of promising compounds failing due to unforeseen safety and toxicity issues that often emerge late in the development cycle. Drug repositioning, by contrast, begins with compounds that have already undergone extensive safety testing in humans. This means that many of the foundational preclinical and early-phase clinical (Phase I) trials, typically the most failure-prone stages of drug development, can often be bypassed . This pre-validated safety profile inherently de-risks the entire development pathway. The resources—capital, time, and scientific expertise—that would otherwise be consumed in establishing basic safety can now be redirected. The focus shifts from the fundamental question of “will this molecule be safe in humans?” to the more targeted inquiry of “will it demonstrate efficacy for this new condition?” This reallocation of resources accelerates the path to market and significantly improves the probability of clinical success.

1.2. A Historical Journey: From Serendipity to Systematic Innovation

The history of drug repositioning is a fascinating narrative, evolving from chance observations to highly systematic, data-driven scientific endeavors.

1.2.1. Early Discoveries Born from Serendipity

In its nascent stages, many of the most celebrated drug repurposing cases arose from accidental findings or “serendipitous” discoveries . These instances often involved astute clinicians or researchers noticing unexpected beneficial effects in patients.

- Sildenafil (Viagra): Perhaps the most iconic example, sildenafil was originally developed by Pfizer in the mid-1990s as an anti-hypertensive drug intended to treat angina (chest pain) . During Phase I clinical trials, an unexpected side effect of inducing erections was observed in male participants . Despite proving ineffective for angina, this unforeseen observation led to a strategic pivot. Sildenafil was subsequently studied and approved for erectile dysfunction (ED) in 1998, marketed globally as Viagra . This accidental finding transformed it into a monumental blockbuster drug.

- Thalidomide: This drug has one of the most dramatic and complex histories in pharmacology. Initially marketed as a sedative and anti-emetic in the late 1950s, it was tragically withdrawn from the market in 1961 due to its severe teratogenic effects, causing devastating birth defects . Despite its troubled past, clinical interest resurfaced decades later. In 1964, its unexpected efficacy in treating erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) was observed . Further research uncovered its potent anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and anti-angiogenic properties, leading to its approval for ENL in 1998 and, remarkably, for multiple myeloma in 2006 . This represented a profound renaissance for a drug once synonymous with tragedy.

- Aspirin: This ubiquitous medication, initially developed as an analgesic and antipyretic in the late 19th century, later evolved into an antiplatelet therapy, widely used for cardiovascular disease prevention .

- Minoxidil: Originally prescribed for hypertension, it was repurposed to treat androgenic alopecia (hair loss) after its side effect of promoting hair growth was observed .

1.2.2. The Shift to Rational and Systematic Approaches

In recent years, drug repositioning has transcended its serendipitous origins, becoming a deliberate and highly systematic scientific discipline . This evolution has been significantly propelled by rapid advancements in human genomics, network biology, chemoproteomics, and sophisticated computational methodologies .

Modern systematic approaches to drug repositioning can be broadly categorized:

- Disease-centric approaches begin with a specific medical condition and seek to identify existing drugs that might effectively treat it by analyzing disease mechanisms, genetic signatures, and molecular pathways .

- Target-centric approaches link a known biological target (e.g., a protein or pathway) to a new disease indication, then search for existing drugs that modulate that target .

- Drug-centric approaches start with a known drug and explore its potential interactions with new targets or its effects on new disease indications, often leveraging its “polypharmacology” (activity on multiple targets) .

This shift from serendipitous discovery to systematic methodologies reflects a profound maturation of scientific understanding and technological capability. Early successes were indeed fortunate observations, but the advent of high-throughput “omics” data (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) and the exponential growth in computational power (AI, machine learning) have enabled researchers to proactively and rationally search for new indications. This is achieved by deeply understanding underlying biological mechanisms and precisely mapping drug-target interactions . This evolution implies that drug repurposing is no longer a “lucky break” but a deliberate, data-driven strategy. It transforms drug development from a high-risk, often exploratory endeavor into a more predictable, hypothesis-driven process, allowing for more efficient allocation of R&D resources and a higher probability of success.

1.3. The Economic Driver: Addressing R&D Costs and Timelines

The pharmaceutical industry faces an escalating crisis of R&D costs and protracted timelines for novel drug development. This challenge has made drug repositioning an increasingly attractive and economically sensible alternative.

Traditional de novo drug discovery is an extraordinarily expensive and time-consuming undertaking. Bringing a new drug to market typically spans 10 to 17 years and incurs costs ranging from $2.5 billion to a staggering $2.8 billion . Furthermore, the process is fraught with high failure rates, with over 90% of drug candidates failing during clinical trials . This unsustainable model exerts immense pressure on pharmaceutical companies to find more efficient and less risky pathways to innovation.

Drug repositioning offers a compelling solution by significantly reducing both the time and financial investment required. Repurposed drugs can reach the market in a much shorter timeframe, typically within 3 to 12 years, with an average time saving of 6 to 7 years compared to de novo development . This acceleration is accompanied by a substantial reduction in overall development expenses. The estimated cost for developing a repurposed drug is around $300 million, a mere fraction of the $2-3 billion required for novel compounds. This represents a remarkable 50-60% reduction in overall development costs .

The inherent de-risking of drug repositioning also translates into a lower probability of failure. Because repurposed drugs have already undergone extensive safety and toxicity testing in humans, they possess established safety profiles. This significantly reduces the likelihood of unexpected adverse events in later clinical stages. Consequently, the approval rate for repurposed drugs that have successfully completed Phase I trials can be as high as 30%, a notable improvement over the typical success rate of less than 10% for traditional new drug development .

The pharmaceutical industry often encounters a “valley of death” where promising compounds fail due to unforeseen safety or efficacy issues, particularly during the early clinical phases. Drug repositioning effectively bridges this gap by bypassing or significantly de-risking these initial, most failure-prone stages (preclinical and Phase I), as the safety of the compound in humans is already known . This fundamental shift in the development paradigm dramatically improves the probability of clinical success and enhances the return on investment, making drug repurposing an increasingly attractive strategy for pharmaceutical companies seeking to populate their pipelines more efficiently and sustainably. This redefines the risk-reward equation for R&D, allowing for more predictable and successful outcomes.

2. The Profit Multiplier: Economic Advantages and Value Creation

The allure of drug repositioning extends far beyond mere efficiency; it is a powerful engine for economic growth and value creation within the pharmaceutical sector. By strategically leveraging existing assets, companies can unlock new revenue streams and significantly enhance their market position.

2.1. Accelerated Development: Speed to Market, Reduced Risk

One of the most compelling economic advantages of drug repositioning is the substantial acceleration of the development timeline, which directly translates into a faster path to market and reduced financial exposure. The ability to leverage the extensive existing knowledge base surrounding a drug’s safety, pharmacokinetics, and formulation is paramount . This pre-existing data often allows for the bypassing of time-consuming and expensive preclinical studies and even Phase I clinical trials, enabling a direct progression to Phase II clinical studies that focus specifically on demonstrating efficacy for the new indication .

This streamlined process also contributes to a faster regulatory review. With a significant body of existing data already reviewed and approved, new candidate therapies can be prepared for clinical trials more quickly, thereby accelerating their assessment by regulatory bodies such as the FDA . This expedited pathway becomes particularly critical during public health crises, as vividly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, where existing drugs were rapidly investigated and deployed to address urgent medical needs . The inherent de-risking and accelerated timeline also contribute to higher approval rates for repurposed drugs compared to novel chemical entities. Approximately one-third of new FDA approvals are, in fact, repurposed drugs.

In the highly competitive pharmaceutical market, time-to-market is an exceptionally valuable strategic asset. Every year saved in development translates directly into an earlier market entry, a longer period of market exclusivity, and a faster generation of revenue. The ability to bypass early-stage trials is not solely about cost savings; it is fundamentally about capitalizing on market opportunities before competitors can, and responding swiftly and effectively to urgent medical needs . This acceleration of development directly impacts a company’s financial performance and its potential for market leadership. It allows for quicker recoupment of R&D investments and the establishment of a stronger market position, particularly in rapidly evolving therapeutic areas or during unforeseen health emergencies.

2.2. Cost Efficiency: A Fraction of De Novo Drug Discovery

The financial benefits of drug repositioning are arguably its most attractive feature, offering a dramatic reduction in the capital investment typically required for drug development. The estimated overall development cost for repurposed drugs hovers around $300 million, a stark contrast to the staggering $2-3 billion often required to bring a novel drug to market .

This substantial cost reduction primarily stems from the ability to leverage existing safety and efficacy data, which significantly minimizes the need for expensive and time-consuming preclinical and early-phase clinical studies . The FDA’s 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway in the United States serves as a prime example of this efficiency, allowing applicants to rely on existing data from previously approved products without having to generate it themselves, thereby avoiding redundant studies . While Phase II and III trials are still often necessary to demonstrate efficacy for the new indication, the foundational safety work is already complete, streamlining the overall clinical development process and reducing its financial burden .

The massive cost savings realized through drug repurposing mean that pharmaceutical companies can achieve a greater number of therapeutic breakthroughs with the same R&D budget. This capital efficiency can be strategically reinvested into other innovative projects, including more de novo discovery efforts, or specifically directed towards therapeutic areas with high unmet medical needs but traditionally lower commercial viability . This fosters a more sustainable and productive R&D ecosystem. It allows companies to diversify their portfolios, pursue niche indications such as rare diseases, and potentially contribute to lowering drug prices for patients, thereby creating a positive feedback loop that benefits both public health and corporate social responsibility .

2.3. Expanding Revenue Streams and Market Footprint

Beyond cost savings and accelerated development, drug repositioning offers a powerful mechanism for pharmaceutical companies to expand their revenue streams and significantly enlarge their market footprint.

Repurposing can breathe new life into a drug and its associated intellectual property. Companies can file for new “method-of-use” patents, which specifically cover the novel therapeutic indication. This strategy can secure additional years of market exclusivity, even after the original compound patent has expired . Furthermore, seeking secondary patents for new formulations, dosages, or combinations involving the repurposed drug serves as another strategic tool to prolong market exclusivity . Such innovations can improve patient convenience, enhance efficacy, or optimize bioavailability, thereby creating new patentable features .

Seeking regulatory approval for a new therapeutic use opens up entirely new patient populations and market segments that were previously untapped . This strategy is particularly valuable when a drug’s original market is maturing or beginning to face intense generic competition . The economic scale of this opportunity is substantial: the global drug repurposing market was valued at $34.08 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to $53.69 billion by 2033, demonstrating its significant and increasing economic impact. Repurposed drugs are already a major contributor to pharmaceutical revenues, capable of generating between 25% and 40% of annual pharmaceutical sales .

Pharmaceutical companies constantly face the looming threat of the “patent cliff,” where blockbuster drugs lose their exclusivity, leading to drastic revenue declines due to the entry of generic competitors . Drug repurposing offers a crucial strategic defense against this phenomenon by creating new patentable uses for existing molecules. This effectively extends their commercial lifespan and mitigates the severe impact of patent expirations . This strategy transforms a potential revenue drain into a new growth opportunity, allowing companies to maintain profitability and reinvest in further innovation. It represents a proactive approach to portfolio management, ensuring sustained value from past and present R&D investments.

2.4. Addressing Unmet Needs: A Dual Mandate for Impact and Profit

Drug repositioning holds exceptional relevance for addressing critical unmet medical needs, particularly in the realm of rare or neglected diseases. In these areas, conventional de novo drug development is often financially unviable due to small patient populations and uncertain market returns, leading to a significant therapeutic gap .

This approach facilitates earlier access to much-needed medicines for serious and life-threatening conditions, including pediatric diseases, where treatment options are often scarce. Recognizing this societal benefit, regulatory bodies worldwide frequently provide incentives for drug repurposing in these areas. Orphan Drug Designation (ODD), for instance, offers benefits such as market exclusivity, tax credits, and regulatory assistance for drugs targeting rare diseases, further incentivizing repurposing efforts .

While the primary driver for pharmaceutical companies is often profit, repurposing for rare diseases presents a unique opportunity to align commercial interests with significant public health impact. The reduced R&D costs inherent in repurposing, coupled with the regulatory incentives for orphan drugs, make these niche markets more attractive than they would be for de novo development. This transforms what was once a “neglected” area into a viable business case . This alignment fosters a more ethical and socially responsible pharmaceutical industry, demonstrating that addressing critical unmet medical needs can also be a path to sustainable profitability. It encourages investment in therapeutic areas where traditional models have historically failed, ultimately benefiting patient populations who desperately need new therapies.

3. Unveiling New Indications: Methodologies and Technologies

The ability to identify new indications for existing drugs has been revolutionized by a convergence of advanced methodologies and cutting-edge technologies. These tools enable researchers to move beyond serendipity toward systematic and predictive discovery.

3.1. Computational Approaches: The Power of In Silico Discovery

Computational drug repurposing, often referred to as in silico screening, involves the use of advanced algorithms and high-throughput biological data to predict new therapeutic applications for approved drugs . This approach offers significant advantages, including the rapid processing of vast datasets, the identification of non-obvious connections between drugs and diseases, and substantial cost-effectiveness .

3.1.1. AI, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), lies at the heart of modern computational drug repurposing. These technologies are adept at processing and analyzing large quantities of diverse data—including genomic, proteomic, and clinical information—to identify intricate patterns and predict drug-disease relationships . This capability significantly increases the precision of candidate identification and shortens decision cycles in the discovery process .

AI models can predict drug-target interactions, optimize molecular design, and even forecast clinical outcomes, thereby accelerating the entire screening process . They are capable of retrospectively analyzing historical clinical data, including adverse event reports and electronic health records (EHRs), to predict suitable repurposed candidates . The impact of AI in this domain is profound: AI-driven in silico screening can identify new targets and novel indications for molecules that have already cleared Phase I trials and are deemed safe. This not only broadens the intellectual property (IP) space for innovators but also accelerates patient access to new therapies. Projections suggest that success rates in Phase I trials for AI-discovered drugs could improve significantly, from a historical 40-65% to an impressive 80-90%.

3.1.2. Knowledge Graphs and Network Biology

Another powerful computational approach involves the creation and analysis of knowledge graphs and the application of network biology principles. Knowledge graphs organize complex biological data into interconnected networks, allowing researchers to rapidly identify, visualize, and analyze direct and indirect relationships between various biological concepts (e.g., diseases, cellular processes) and molecular classes (e.g., proteins, small molecules) . Network-based approaches represent biological systems as intricate networks of drugs, proteins, and diseases, enabling the identification of non-obvious repurposing opportunities by uncovering connections that might otherwise remain hidden .

These methodologies excel at integrating heterogeneous data types, including gene expression data, protein-protein interaction data, and insights gleaned from vast scientific literature, to construct comprehensive disease models . The utility of knowledge graphs lies in their ability to provide a rapid and holistic understanding of disease biology, directing researchers toward critical evidence that can power repurposing projects . Furthermore, graph neural networks (GNNs), a form of deep learning, can be employed to screen large databases of approved drugs and predict novel drug-target interactions .

The evolution of computational methods, particularly AI and knowledge graphs, represents a fundamental shift from merely generating hypotheses about drug-disease relationships to predicting them with increasing accuracy and confidence. This is achieved by moving beyond simple data correlations to building complex, multi-dimensional models that can infer novel connections and mechanisms . This predictive capability significantly reduces the number of false positives and the need for extensive, costly experimental validation, making the initial discovery phase of drug repurposing far more efficient and targeted. It transforms drug discovery into a data science problem, enabling faster identification of promising candidates.

3.2. Advanced Preclinical Validation: Bridging the Gap to Clinic

Despite the promise of in silico findings, the transition from preclinical research to human clinical trials remains a formidable challenge. Over 90% of investigational drugs fail during clinical development, largely due to the poor translation of pharmacokinetic, efficacy, and toxicity data from preclinical models to human settings . Advanced preclinical validation technologies are crucial for bridging this gap.

3.2.1. Organ-on-a-Chip Technology: Human-Relevant Models

Organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems are microfluidic in vitro culture systems meticulously designed to mimic the physiological properties of human organs, providing unprecedented insights into organ function and pathophysiology . These sophisticated chips replicate the cellular microenvironment, including vital physical forces such as fluid shear stress and mechanical compression, and allow for real-time, high-resolution optical imaging of cellular responses to environmental cues .

OoCs are emerging as a potential replacement for traditional animal testing, offering more human-relevant models for evaluating drug efficacy and toxicity . For example, a human lung airway chip was successfully used to identify the antimalarial drug amodiaquine as a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 infection, accurately predicting its effect where conventional cell cultures failed . Multi-organ chips are also being developed to simulate complex systemic drug effects, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, providing a more comprehensive understanding of drug behavior in the human body . The ability of OoCs to produce data consistent with clinical observations underscores their high functionality, which can significantly optimize drug regimens for early-phase clinical trials.

The “bench-to-bedside” translation has historically been a major bottleneck in drug development, largely due to the inadequacy of traditional preclinical models, such as animal models, which often fail to accurately predict human responses . Advanced tools like Organ-on-a-Chip provide more human-relevant and precise data, allowing for earlier and more accurate predictions of drug efficacy and toxicity in humans . This directly impacts the success rate of drug repurposing by providing robust evidence that can guide clinical trial design, patient selection, and dosing regimens more effectively. This ultimately reduces the risk of costly late-stage clinical failures and accelerates the development of repurposed therapies that are more likely to succeed in human patients.

3.2.2. CRISPR Screening: Precision Target Identification

CRISPR-Cas9, a Nobel Prize-winning gene-editing tool, has revolutionized molecular biology by enabling precise alterations in DNA sequences, thereby facilitating the in-depth investigation of gene functions. CRISPR-based screening approaches allow for genome-wide screening, systematically identifying potential therapeutic targets by activating or inhibiting specific genes .

In the context of drug repurposing, CRISPR screens can uncover novel synthetic lethal targets, provide a clearer understanding of a therapeutic’s mechanism of action, and help stratify patients to identify those most likely to respond to treatment . They are also invaluable for understanding the mechanisms of drug resistance and sensitivity before compounds enter clinical trials. For instance, CRISPR screens can identify genes crucial for cell survival in various cancers or pinpoint mutations that contribute to drug resistance, offering new avenues for therapeutic intervention .

This technology significantly enhances the precision of target identification and validation, streamlining the drug discovery process and offering novel insights into complex biological systems . This directly supports rational drug repurposing by pinpointing the exact molecular pathways affected by existing drugs, thereby providing a strong scientific rationale for their new applications.

3.3. Omics Technologies: A Holistic View of Disease and Drug Action

Omics technologies, encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, provide a comprehensive, multi-dimensional view of biological systems at the molecular level . The integration of these diverse datasets is paramount for gaining a holistic understanding of complex disease mechanisms and the intricate ways in which drugs exert their actions .

These technologies have multiple applications in drug repurposing:

- Target Identification: By analyzing gene expression patterns, protein profiles, and metabolic pathways in diseased states, omics data can identify novel drug targets or confirm existing ones, providing a robust foundation for repurposing hypotheses .

- Mechanism Elucidation: Proteomics, for example, can reveal how drugs interact with the human body at a molecular level, including identifying protein biomarkers for diseases and understanding complex protein-protein interactions . Metabolomics, on the other hand, helps explore metabolic pathways and identify the metabolic impacts of drugs, offering insights into their broader physiological effects .

- Signature-Based Methods: A powerful application involves comparing the gene expression signatures induced by drugs against those characteristic of specific diseases. This can identify compounds that effectively reverse pathological gene expression patterns, thereby suggesting promising repurposing opportunities .

- Patient Stratification: When combined with AI and machine learning, omics data can be used to stratify patients based on their unique genetic profiles or protein expression patterns. This enables the identification of patient subgroups most likely to benefit from a repurposed therapy, a cornerstone of precision medicine .

Diseases are inherently complex, often involving a multitude of genes, proteins, and metabolic pathways. Relying on a single “omic” layer provides only a partial and often misleading picture. Integrating multi-omics data allows for a holistic understanding of disease networks and drug-induced changes, revealing subtle or non-obvious connections that might be missed by analyses focused on a single data type . This deeper, more comprehensive understanding is critical for identifying truly effective repurposed candidates. Omics technologies therefore enable a more rational and precise approach to drug repurposing, moving beyond simple phenotypic observations to a mechanistic understanding of why a drug might work for a new indication. This increases the scientific rationale for embarking on clinical trials and supports the development of personalized treatment strategies.

3.4. Real-World Evidence (RWE) and Clinical Observation

While cutting-edge computational and preclinical methodologies drive much of modern drug repurposing, real-world evidence (RWE) and astute clinical observation continue to play a vital, complementary role.

Historically, many significant repurposing opportunities have emerged from the unexpected benefits of a drug noticed during clinical trials for its original indication or through the “off-label” use by clinicians in routine practice . Sildenafil’s discovery for erectile dysfunction, as previously discussed, serves as a prime example of such serendipitous yet impactful clinical observation .

In recent years, the advent of medical big data has transformed the utility of real-world evidence. Large-scale datasets, including electronic health records (EHRs) and insurance claims data, now offer a rich and invaluable source for drug-repositioning research . RWE enables the analysis of patients with diverse backgrounds and in various regions, facilitating a more comprehensive evaluation of drug efficacy and safety in actual clinical practice. This extensive data can also help detect adverse events that might not be apparent among the limited patient populations in controlled clinical trials. Furthermore, RWE can be used to validate computational findings and to systematically examine patterns of off-label drug usage, providing empirical support for potential new indications.

Platforms such as CURE ID exemplify the power of RWE in action. This tool allows clinicians to report their real-world experiences treating patients with repurposed drugs, including observations on new uses, drug combinations, dosing regimens, and patient populations. This crowdsourced information helps to identify potential “efficacy signals,” particularly for very rare diseases where conducting traditional randomized controlled trials may be infeasible .

Real-world evidence and clinical observation create a vital feedback loop that extends from post-market drug use back into the discovery pipeline. This “bottom-up” approach effectively complements the “top-down” computational and preclinical methods. It captures the nuanced effects of drugs in diverse patient populations and real-world settings, which tightly controlled clinical trials might inadvertently miss . This integration of real-world data enhances the robustness of repurposing hypotheses, provides valuable insights that inform the design of subsequent clinical trials, and offers compelling evidence for regulatory approval. It transforms anecdotal observations into actionable insights, thereby accelerating the translation of promising therapeutic potentials into formally approved treatments.

4. Navigating the Regulatory Landscape: Pathways to Approval and Market Access

Successfully bringing a repurposed drug to market requires a sophisticated understanding and strategic navigation of complex regulatory pathways. While the inherent advantages of repurposing streamline many aspects, unique challenges persist.

4.1. The FDA’s 505(b)(2) Pathway: A Streamlined Route

In the United States, the 505(b)(2) New Drug Application (NDA) pathway is a cornerstone for drug repurposing. Established under the Hatch-Waxman Amendments of 1984, this pathway offers a streamlined route for approval by allowing applicants to rely, in part, on data from previously approved products. This includes published literature or the FDA’s prior findings regarding the safety and efficacy of a reference listed drug (RLD), even if the applicant did not generate that data themselves . The primary objective of this pathway is to avoid redundant studies, thereby significantly expediting the approval process .

The 505(b)(2) pathway is particularly well-suited for drug repurposing efforts involving new formulations, new indications, novel combinations of existing drugs, different dosage forms, altered strengths, or new routes of administration . By leveraging existing data, companies can significantly reduce development timelines, often by 5-10 years, and substantially lower costs compared to a full 505(b)(1) NDA . While the pathway leverages existing data, applicants must still provide sufficient new data, typically through “bridging studies,” to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of the specific new product .

Successful examples of products approved via the 505(b)(2) pathway include advanced formulations like Suboxone® film (buprenorphine + naloxone) for opioid use disorder, which quickly gained market dominance, and Glumetza® (metformin hydrochloride extended-release) for type 2 diabetes, offering once-daily dosing with improved gastrointestinal tolerability .

The 505(b)(2) pathway acts as a crucial regulatory “fast lane” for drug repurposing. Without it, companies would face the full burden of de novo approval, effectively negating many of repurposing’s inherent advantages. Its very existence signals regulatory recognition of the immense value in leveraging existing scientific knowledge and clinical experience . This pathway is a cornerstone for the commercial viability of drug repurposing, providing a clear, albeit sometimes complex, route to market exclusivity and profitability. It incentivizes innovation around existing molecules by offering a more predictable and efficient regulatory journey, which is vital for attracting investment and driving development.

4.2. Tailored Clinical Trials: Adapting Phases for Repurposed Drugs

The clinical development process for repurposed drugs is often significantly modified compared to traditional de novo drug development, allowing for greater efficiency and speed. For repurposed medicines, Phase I trials, which typically involve testing a novel medicine in healthy volunteers to ensure safety at a relevant dose, may often be bypassed . This is possible because the drug’s safety profile has already been well-established in humans for its original indication .

This streamlining allows development efforts to often proceed directly to Phase II and III trials. These later-stage trials then focus specifically on demonstrating efficacy and safety within the new patient population and for the novel indication . Key considerations for designing these tailored trials include:

- A strong scientific rationale for the new indication.

- Thorough evaluation of potential drug combinations, as polytherapy is increasingly common.

- A comprehensive assessment of the drug’s safety profile within the new patient population, paying close attention to potential drug-drug interactions.

- Careful dose adjustments, as the optimal dosage for a new indication may differ from the original.

- Precise definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure patient safety and trial validity for the new patient group.

- Appropriate selection of clinical endpoints that accurately measure the therapeutic effect in the new disease context.

Furthermore, preclinical biomarkers and mechanistic insights are increasingly instrumental in informing clinical trial design for repurposed drugs. These insights guide patient selection, helping to identify subgroups most likely to benefit from the therapy, and aid in defining appropriate endpoints, particularly in the context of precision medicine approaches . For example, mouse clinical trials (MCTs), which are preclinical population studies, can help identify biomarker panels to optimize patient stratification and enrollment criteria for repurposed drugs, potentially expanding indications or trial populations.

While the safety of a repurposed drug is largely known, demonstrating its efficacy for a new indication remains paramount. The ability to skip Phase I trials is a tremendous advantage, but it shifts the burden of proof heavily onto Phase II and III studies. This necessitates highly targeted and meticulously designed trials that account for potential differences in patient populations, dosages, and drug interactions within the new therapeutic context . The strategic use of biomarkers and mechanistic insights derived from preclinical studies helps to make these trials more efficient and significantly increases their chances of success by ensuring the selection of the right patients and the most relevant endpoints . This tailored approach to clinical trial design is crucial for maximizing the inherent advantages of drug repurposing. It ensures that the clinical evidence generated is robust enough to satisfy stringent regulatory requirements while simultaneously minimizing unnecessary costs and accelerating the path to approval for the new indication.

4.3. Regulatory Hurdles: Addressing Old Data and New Requirements

Despite the inherent advantages, navigating the regulatory landscape for repurposed drugs is not without its complexities. A significant challenge stems from the lack of specific regulatory pathways solely dedicated to repurposed drugs; instead, existing pathways like 505(b)(2) must be adapted, which can introduce intricate requirements .

One particularly acute hurdle arises when dealing with older generic drugs: the available toxicology data may be decades old and often does not meet current, more stringent regulatory standards . Regulatory agencies, such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA), may demand original toxicology reports for registration . This requirement can create a considerable power imbalance, as the original Marketing Authorization Holder (MAH) may be reluctant to disclose old dossiers that might contain gaps when assessed against modern regulations, or they may fear that new scrutiny could raise questions about their existing approvals . This reluctance can effectively impede the approval process for a new indication, even after academic institutions or smaller enterprises have invested heavily in clinical trials, especially for rare diseases where additional studies are prohibitively expensive .

Furthermore, determining the appropriate dosage and treatment regimen for a new patient population can be complex. Often, reformulation of the drug may be required to suit the new indication, adding another layer of regulatory complexity and cost .

A pervasive challenge, particularly for off-patent generic drugs, is the lack of financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies to pursue formal regulatory approval for new indications. Doctors can legally prescribe these drugs off-label, and generic manufacturers operate on low profit margins, offering little motivation for costly label expansion efforts .

The current regulatory framework, while designed to incentivize new innovation (via patents) and foster generic competition (once patents expire), often places repurposed off-patent drugs in a regulatory “grey area.” While off-label use is legal, it lacks the formal regulatory backing and market incentives (e.g., consistent reimbursement, widespread physician awareness) that come with an on-label indication . This creates a challenging situation: without formal approval, market uptake and patient access remain limited, but without sufficient market incentive, companies are reluctant to pursue the costly and complex formal approval process. This regulatory gap significantly hinders the full potential of generic drug repurposing, particularly for achieving widespread adoption and ensuring equitable patient access. Policy changes, such as the implementation of dedicated regulatory pathways for non-manufacturers or new incentives for label expansion of generics, are increasingly recognized as necessary to unlock this vast, untapped therapeutic potential .

5. Intellectual Property: Securing Your Competitive Edge

In the pharmaceutical industry, intellectual property (IP) is the lifeblood that protects massive R&D investments and grants companies exclusive market rights . For drug repurposing, a well-crafted IP strategy is paramount to securing competitive advantage and maximizing profitability.

5.1. Method-of-Use Patents: Extending Product Lifecycles

The core IP strategy in drug repurposing revolves around obtaining “method-of-use” patents. These patents protect the specific new method by which an existing drug is used to treat a novel condition, thereby serving as the primary mechanism for extending the patent life of a repurposed drug . To be granted, this new use must satisfy standard patentability criteria: it must be novel, non-obvious, and demonstrate a useful purpose . However, the presence of prior art or even subtle hints in original scientific literature can significantly complicate the patenting process.

A critical challenge arises with off-patent generic drugs. While method-of-use patents offer theoretical exclusivity for a new indication, their practical value can be severely diminished by generic substitution at the pharmacy level . In many jurisdictions, pharmacists can legally dispense a cheaper generic version of the drug, even if that generic’s label does not include the newly patented indication, effectively circumventing the method-of-use patent .

This situation creates an IP paradox in drug repurposing. The pharmaceutical industry relies heavily on patent protection to recoup its massive R&D investments. While method-of-use patents offer a theoretical extension of exclusivity, their practical enforceability for off-patent drugs is severely limited by generic substitution laws . This fundamental limitation creates a significant disincentive for traditional pharmaceutical companies to invest in repurposing generics, as the potential financial returns are uncertain and difficult to protect . This IP paradox is a major barrier to realizing the full public health benefit of generic drug repurposing. It underscores the urgent need for policy innovation, such as the proposed “labeling-only” 505(b)(2) pathways for non-manufacturers, to create viable commercial incentives for these valuable new uses .

5.2. Secondary Patents and Formulation Innovations

Beyond method-of-use patents, companies can strategically seek “secondary patents” for new formulations, dosages, or combinations involving the repurposed drug . These innovations are not merely incremental; they can significantly improve patient convenience, enhance therapeutic efficacy, or optimize drug bioavailability . For instance, developing extended-release tablets, transdermal patches, or new liquid formulations can be patented separately from the original drug’s active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) . Similarly, combining an existing drug with another active ingredient can create a synergistic effect and, crucially, new intellectual property .

These secondary patents serve as a powerful strategic tool to prolong market exclusivity well beyond the expiration of the original compound patent, forming a key component of a company’s “lifecycle management” strategy . The value of a drug is not solely confined to its active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Innovations in how it is delivered (e.g., through new formulations or routes of administration) or how it is combined with other therapeutic agents can create substantial new therapeutic advantages and, critically, new patentable intellectual property . This implies that even if the core molecule is off-patent, a company can still develop a differentiated, proprietary product for the repurposed indication. This strategy allows pharmaceutical companies to continue innovating and deriving value from mature assets. It shifts the focus from purely de novo chemical entity discovery to a broader spectrum of pharmaceutical innovation, encompassing drug product development and combination therapies, thereby extending revenue potential and competitive advantage.

5.3. The “Evergreening” Debate: Balancing Exclusivity and Public Good

The practice of “evergreening” has become a contentious issue in healthcare policy, highlighting the tension between incentivizing pharmaceutical innovation and ensuring public access to affordable medicines. Evergreening refers to strategies employed by drug producers to extend patent protections beyond the original 20-year term by obtaining new patents on minor modifications to existing drugs, such as new formulations, dosage forms, delivery systems, or slight variations to the original compound .

Critics argue that evergreening artificially extends monopolies, delays the market entry of more affordable generic alternatives, and keeps drug prices unnecessarily high, primarily serving a company’s economic advantage rather than providing significant therapeutic benefits . The legal battle between Novartis and the Indian government over the cancer drug Gleevec (imatinib) is a prominent example, where India’s patent law was amended to prevent patenting minor variations unless they demonstrated enhanced therapeutic efficacy .

Pharmaceutical companies, conversely, defend these practices as legitimate protection of ongoing innovation, arguing they are necessary to recoup the high costs of R&D and to incentivize further investment in drug development . They contend that even minor modifications can improve patient safety, reduce adverse effects, or enhance adherence. Research suggests a nuanced reality: while some evergreening tactics may indeed delay certain generic formulations, they often do not completely prevent all generic competition.

The “evergreening” debate encapsulates a fundamental tension in pharmaceutical policy: how to balance the need to incentivize costly R&D and protect intellectual property with the public’s need for affordable and accessible medicines. Drug repurposing, particularly when achieved through minor modifications or new formulations, often falls squarely into this contentious area . This ongoing debate significantly shapes the regulatory and legal environment for drug repurposing. Policymakers must continually evaluate whether current IP frameworks adequately serve both innovation and public health objectives, potentially leading to legislative changes that could impact the commercial attractiveness of certain repurposing strategies.

5.4. Leveraging Patent Data for Strategic Intelligence (Mention DrugPatentWatch)

In the biopharmaceutical sector, where intellectual property is often described as “the lifeblood” of the industry, patent analytics is not merely a legal compliance exercise; it is a crucial discipline for informing R&D decisions, identifying market opportunities, and anticipating competitive moves . It provides a comprehensive understanding of the existing IP landscape, revealing both untapped opportunities and potential pitfalls.

For drug repurposing, leveraging patent data offers several strategic advantages:

- Guiding R&D Investment: By meticulously analyzing patent trends, companies can identify emerging technologies, assess the competitive environment, and make data-driven decisions on where to invest R&D budgets for repurposing initiatives. This helps in pinpointing therapeutic areas or molecular mechanisms that are ripe for new indications.

- Competitive Intelligence: Patent analytics provides invaluable insights into competitors’ strategies. It reveals where rivals are investing their resources, what technologies they are focusing on, and how aggressively they are protecting their IP. This intelligence is critical for shaping one’s own patent strategy, whether to collaborate, compete directly, or strategically avoid crowded IP spaces.

- Risk Mitigation: Proactive patent analysis helps identify potential patent infringement risks before they escalate into costly lawsuits, allowing companies to navigate the complex IP landscape more safely.

- Identifying White Space: Detailed patent data can reveal unexplored areas for new indications or innovative formulations where new IP can be secured without infringing existing patents . This “white space” analysis is crucial for carving out defensible market positions.

Tools like DrugPatentWatch are invaluable for this purpose. They offer detailed insights into patent expirations, exclusivity periods, and generic entry opportunities . By analyzing this rich data, companies can identify gaps where new innovations won’t infringe existing patents and strategically secure their own intellectual property . DrugPatentWatch provides comprehensive business intelligence on biologic and small molecule drugs, aiming to help companies transform raw data into actionable market domination strategies.

In an industry where intellectual property is indeed “the lifeblood,” relying solely on traditional legal counsel for patent searches is insufficient. Strategic competitive advantage in drug repurposing demands proactive, data-driven patent analytics . This means not just securing patents, but intelligently navigating the entire patent landscape to identify opportunities for new IP and avoid costly litigation. Companies that effectively leverage patent intelligence tools, such as DrugPatentWatch, can gain a significant competitive edge in the repurposing space. This allows them to make informed decisions about which molecules to pursue, how to formulate them, and what new indications to target, all while optimizing their IP portfolio for maximum market protection and profitability.

6. Commercialization and Market Acceptance: From Lab to Leadership

The journey of a repurposed drug from a promising laboratory discovery to a widely adopted clinical treatment is complex, involving not only scientific validation and regulatory approval but also strategic commercialization and overcoming market acceptance hurdles.

6.1. Market Size and Growth Projections: A Lucrative Future

The global drug repurposing market is not merely a niche area; it is a substantial and rapidly expanding segment of the pharmaceutical industry, signaling a lucrative future for strategic investors. The market was valued at an impressive $34.08 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $53.69 billion by 2033, demonstrating a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.18%. Other analyses project it to reach as high as $59.30 billion by 2034 with a CAGR of 5.42%.

North America currently dominates this market, holding the largest revenue share (47% in 2024), a position attributed to its well-established pharmaceutical industry, mature healthcare system, and supportive regulatory environment. Asia-Pacific is projected to be the fastest-growing region, indicating a global expansion of repurposing efforts. Analysis of market segments reveals that the “same therapeutic area” segment held a significant revenue share (68% in 2024), suggesting a strong trend towards expanding indications within existing disease categories. Similarly, the disease-centric approach to repurposing also commanded the largest revenue share (43% in 2024), emphasizing a focused, rational expansion of drug utility rather than purely serendipitous discoveries. Therapeutic areas such as oncology and central nervous system (CNS) diseases are specifically anticipated to show significant growth in the coming years .

The substantial market size and consistent growth projections confirm that drug repurposing is no longer a fringe strategy but a mature and economically significant segment of the pharmaceutical industry. The dominance of “same therapeutic area” and “disease-centric” approaches suggests a more focused, rational expansion of drug utility rather than solely relying on serendipitous discoveries. This market maturity signals a compelling opportunity for businesses to invest, but it also implies increased competition. Companies must therefore develop sophisticated strategies to identify and commercialize repurposed drugs, leveraging advanced technologies and navigating regulatory pathways adeptly to capture market share and achieve leadership.

6.2. Overcoming Market Hurdles: Physician Adoption and Reimbursement Challenges

Despite the compelling scientific and economic advantages of drug repurposing, real-world market acceptance can present significant hurdles, particularly concerning physician adoption and reimbursement policies for off-label uses.

6.2.1. Physician Reluctance in Off-Label Prescribing

While physicians are legally permitted to prescribe approved drugs for unapproved (off-label) indications, this practice often faces significant barriers to broad adoption:

- Lack of Adequate Scientific Data: Physicians may prescribe off-label without sufficient scientific data, leading to concerns about efficacy and safety that have not undergone formal regulatory risk-benefit analysis . Reports indicate that only about 30% of off-label prescribing is supported by adequate scientific data .

- Medico-Legal Risks: Off-label prescribing can expose physicians to medico-legal risks, such as malpractice lawsuits, which naturally limits its widespread use even when supportive evidence exists .

- Lack of Awareness and Information: Outdated generic drug labeling means prescribers may not have access to all necessary information regarding the full risk-benefit profile of a repurposed drug for a new indication. Physicians often rely on sources other than old labels, and community-based practitioners, in particular, may struggle to stay updated on new treatment options across many diverse diseases .

- Disincentives for Manufacturers: From a business perspective, seeking supplemental regulatory approval for new uses late in a drug’s patent life is often not financially enticing for pharmaceutical companies. The developmental cost of new uses, coupled with the risk of non-supportive evidence, can outweigh the perceived benefits of formal approval, especially when off-label use is already common .

6.2.2. Reimbursement Challenges for Off-Label Use

Insurance coverage for off-label uses of repurposed drugs is a complex and often inconsistent area:

- “Experimental” or “Investigational” Designation: Managed care organizations and private health insurance plans frequently decline reimbursement for off-label uses, categorizing them as “experimental” or “investigational” .

- Compendia and Guidelines: Medicare, for instance, may cover off-label uses if they are listed in major drug compendia (e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Drugs and Biologics Compendium) or are supported by authoritative medical literature and accepted standards of medical practice . However, comprehensive guidelines do not exist for every disease or medical specialty, creating gaps in coverage .

- Pricing Uncertainty: For newly repurposed drugs, particularly those targeting complex conditions like addiction disorders, there is often “a lot of uncertainty around how reimbursement and pricing would actually play out,” which can deter investment .

The scientific and economic advantages of drug repurposing are clear, but their full real-world impact is often constrained by significant barriers to market acceptance. The disconnect between legal off-label prescribing and formal regulatory approval, coupled with fragmented reimbursement policies and physician awareness gaps, creates a substantial chasm . This means that even highly effective repurposed therapies may not reach all patients who could benefit from them. To fully capitalize on the potential of drug repurposing, the industry must actively engage with regulatory bodies, healthcare providers, and payers to streamline approval processes for new indications, improve physician education and awareness, and ensure consistent reimbursement. This necessitates a multi-stakeholder approach to bridge the gap from scientific discovery to widespread patient access.

6.3. The Role of Patient Advocacy Groups and Collaborative Initiatives

In the challenging landscape of drug repurposing, particularly for diseases with high unmet needs, patient advocacy groups (PAGs) and collaborative initiatives play an increasingly critical role. These stakeholders are vital in driving research, shaping policy, and facilitating market acceptance.

6.3.1. Patient Advocacy Groups as Driving Forces

PAGs serve as powerful catalysts, especially for rare diseases, by providing essential resources, building supportive communities, and actively engaging in research and drug development efforts . They are often motivated by the urgent needs of patients and are willing to step in where traditional pharmaceutical companies may lack sufficient financial incentives for de novo development.

PAGs exert significant influence on research priorities, clinical trial design, and regulatory decision-making . They can contribute directly to trial design and assist with patient recruitment by raising awareness and facilitating screening . Many PAGs also directly fund and co-develop studies into promising drug candidates, thereby accelerating the path from discovery to clinical trials . Beyond research, PAGs are crucial in policy advocacy, successfully lobbying for legislation like the Orphan Drug Act, which provides vital incentives for rare disease drug development . They also actively push for broader insurance coverage and fair pricing regulations, striving to ensure patient access to therapies .

6.3.2. Collaborative Initiatives and Open Science

The complexities of commercializing repurposed drugs, particularly for rare or neglected diseases, are often too great for any single entity to overcome. This has led to the rise of multi-partner collaborations and open science initiatives. These collaborations involve academia, industry, regulators, and patient groups, pooling resources, expertise, and data to accelerate the translation of repurposed drugs .

Platforms like Drug Repurposing Central, funded by initiatives such as REPO4EU, exemplify the power of open science. These platforms foster transparency and collaboration by providing open access to research results, preprints, and open peer review. They also offer interactive bibliographies and tools that promote data sharing within the repurposing community .

The challenges in commercializing repurposed drugs, especially for rare or neglected diseases, are indeed too great for any single entity to overcome. The rise of patient advocacy groups and collaborative initiatives demonstrates a clear recognition that a collective, open-science approach involving academia, industry, regulators, and patients is absolutely essential . This collaborative ecosystem can effectively pool diverse resources, specialized expertise, and vast datasets, thereby accelerating the translation of repurposed drugs from promising candidates to accessible therapies. This ultimately maximizes both patient benefit and shared economic value across the pharmaceutical landscape.

7. Illustrative Success Stories: Case Studies in Repositioning

The theoretical advantages of drug repositioning are best illuminated by real-world success stories that have transformed patient care and generated substantial economic value.

7.1. Sildenafil: The Unexpected Blockbuster

Sildenafil, universally recognized by its brand name Viagra, stands as the quintessential poster child for successful drug repurposing.

- Original Indication: Developed by Pfizer in the mid-1990s, sildenafil was initially conceived and investigated as an anti-hypertensive drug to treat angina pectoris, a condition characterized by chest pain due to reduced blood flow to the heart .

- Repurposing Discovery: The pivotal moment occurred during Phase I clinical trials. While the drug proved largely ineffective for angina, researchers observed an unexpected and consistent side effect: male participants experienced erections . This serendipitous finding, a testament to astute clinical observation, prompted a strategic pivot in the drug’s development.

- New Indication & Approval: Following dedicated studies for this unforeseen effect, sildenafil received approval for the treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED) in 1998, marketed as Viagra .

- Market Impact: The commercial impact was nothing short of monumental. Viagra became a global phenomenon, generating over $35 billion in worldwide sales, with its annual peak sales reaching an impressive $2 billion in 2012 . It fundamentally reshaped the market for ED treatments.

- Further Repurposing: Sildenafil’s journey didn’t end there. It was later repurposed again and approved for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in 2005 . Furthermore, it continues to be investigated for other potential uses, including Alzheimer’s disease and peripheral neuropathy.

Sildenafil’s journey vividly illustrates that even within systematic drug development, unexpected “side effects” can be the genesis of a far more lucrative and impactful indication. This underscores the critical importance of keen clinical observation and the organizational flexibility to pivot R&D efforts based on unforeseen, yet compelling, data . Companies should foster a culture that not only systematically captures all observed drug effects, but also actively investigates them, not just the intended ones. This proactive “pharmacovigilance for opportunity” can unlock significant hidden value within existing drug portfolios, transforming perceived failures or minor side effects into major commercial successes.

7.2. Thalidomide: A Remarkable Renaissance

Thalidomide’s story is arguably one of the most dramatic and instructive in the history of drug repurposing, showcasing a remarkable journey from tragedy to therapeutic triumph.

- Original Indication & Tragedy: Introduced in the late 1950s, thalidomide was widely marketed as a sedative and anti-emetic, particularly popular among pregnant women for treating morning sickness . However, its widespread use led to a catastrophic outcome: it was found to cause severe teratogenic effects, resulting in devastating birth defects . This tragic discovery led to its withdrawal from the market in 1961 and a worldwide ban by the end of the decade, prompting significant reforms in drug regulation globally.

- Repurposing Discovery: Despite its dark past, clinical interest in thalidomide resurfaced in 1964 when Dr. Jacob Sheskin observed its unexpected efficacy in treating erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), a painful inflammatory complication of leprosy . This observation marked the beginning of its therapeutic renaissance.

- New Indications & Approval: Following extensive research that elucidated its potent anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and anti-angiogenic properties, thalidomide received approval for ENL in 1998 . A pivotal moment came in 2006 when it was approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma, a plasma cell cancer .

- Market Impact: Thalidomide derivatives have since achieved significant clinical and economic success in treating multiple myeloma . It became a first-line agent and a “standard” treatment in combination therapies for multiple myeloma, notably improving response rates and extending time to disease progression .

- Regulatory Innovation: The tragic history of thalidomide directly spurred the development of stringent drug safety regulations. In the U.S., the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (S.T.E.P.S.) program was implemented, a highly controlled distribution system that became a model for managing high-risk, high-benefit drugs, ensuring patient safety while allowing access to a vital therapy.

Thalidomide’s story is a powerful testament to the inherent complexity of drug action and the potential for molecules to possess multiple, sometimes seemingly contradictory, effects. It also highlights the pharmaceutical industry’s capacity for profound resilience and adaptation, both scientifically (through a deeper understanding of new mechanisms) and regulatorily (by implementing strict risk mitigation programs like S.T.E.P.S.). This case underscores that even drugs with a history of severe safety issues should not be discarded prematurely. Instead, continuous scientific inquiry into their full pharmacological profiles, coupled with robust risk management strategies, can unlock significant therapeutic value.

7.3. Metformin: A Diabetes Drug’s Anti-Cancer Promise

Metformin, a mainstay in diabetes management, exemplifies the vast untapped potential within widely prescribed, off-patent generic drugs, revealing a compelling new chapter in its therapeutic journey.

- Original Indication: Metformin is one of the most widely prescribed oral anti-diabetic medications globally, serving as the first-line therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus since its FDA approval in 1995 . It is a low-cost, generally well-tolerated generic medication, with over 86 million prescriptions in the United States in 2022 alone, making it the second most commonly prescribed medication .

- Repurposing Discovery: The anti-cancer potential of metformin began to emerge in the early 2000s. Epidemiological data revealed that diabetic patients taking metformin exhibited a lower risk of developing various cancers and demonstrated improved survival rates, prompting researchers to investigate its anti-tumor abilities .

- Mechanistic Insights: Preclinical studies have since elucidated several anticancer mechanisms of metformin. These include the inhibition of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), activation of AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase), reduction of inflammation, and modulation of key metabolic pathways that are often dysregulated in cancer cells . Metformin has also been observed to activate T cell-mediated immune responses against cancer cells .

- Clinical Trials & Impact: The promising preclinical and epidemiological data have propelled metformin into extensive clinical investigation for cancer. It is currently being tested in over 100 clinical trials worldwide for various cancer treatments and prevention strategies . While comprehensive data on survival outcomes are still awaited, early trials have shown intriguing results, such as a significant decrease in Ki67 (a proliferation marker) in pre-surgical endometrial cancer patients treated with metformin monotherapy . Some experts have even suggested that metformin “may have already saved more people from cancer deaths than any other drug in history,” though its full impact remains to be quantified .

Metformin’s journey highlights the vast, untapped potential residing within widely prescribed, off-patent generic drugs. Its low cost and exceptionally well-established safety profile make it an ideal candidate for repurposing, particularly for chronic diseases like cancer where long-term, affordable treatment is crucial . The sheer volume of patients exposed to such drugs in routine clinical practice creates a rich source of real-world data that can be mined for identifying new therapeutic indications. This case underscores the profound societal and economic value of systematically exploring new uses for generic drugs. It challenges the traditional profit-driven model by demonstrating that significant public health benefits and cost savings can be achieved through repurposing, even for drugs that offer limited direct financial incentive to their original manufacturers.

7.4. Other Transformative Repurposing Examples

The impact of drug repurposing extends across a broad spectrum of therapeutic areas, demonstrating its versatility and potential to address diverse medical needs.

- Aspirin: Beyond its initial uses as an analgesic and antipyretic, aspirin was famously repurposed as an antiplatelet agent for cardiovascular disease prevention.

- Propranolol: Originally used for hypertension and angina, propranolol found new indications in migraine prophylaxis and anxiety. More notably, its effect on infantile hemangiomas was discovered through an unexpected clinical observation in a baby being treated for a heart condition, leading to its formal approval for this pediatric indication .

- Dexamethasone: A widely used corticosteroid for conditions like severe allergies, asthma, and arthritis, dexamethasone was rapidly repurposed during the COVID-19 pandemic. It proved highly effective in reducing mortality among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, highlighting the critical role of repurposing in public health emergencies .

- Raloxifene: This drug, originally developed as a treatment for osteoporosis, has been successfully repurposed to reduce the risk of breast cancer in high-risk women .

- Miltefosine: Initially a canine antiparasitic agent, miltefosine was repurposed as an effective treatment for leishmaniasis, a parasitic infection in humans.

- AZT (Azidothymidine): Originally developed as a potential cancer therapeutic in the 1960s but never progressed, AZT was rapidly identified as a potent anti-HIV compound during the AIDS crisis. This repurposing effort accelerated its journey from in vitro testing to clinical use in less than three years, demonstrating the speed and urgency drug repurposing can offer in public health emergencies.

These diverse examples collectively demonstrate that drug repurposing is not confined to specific therapeutic areas or drug classes. Its applicability spans from chronic conditions like cancer and neurological disorders to acute public health emergencies such as pandemics, and even extends from veterinary medicine to human applications . This broad utility underscores the fundamental principle of polypharmacology—the understanding that drugs often interact with multiple biological targets beyond their primary intended one . The sheer variety of successful repurposing cases suggests that almost any existing drug could potentially hold hidden therapeutic value. This encourages a broad, systematic approach to drug discovery that seeks to fully characterize the pharmacological landscape of known molecules, rather than focusing solely on de novo development.

8. The Future of Drug Repositioning: Trends and Opportunities

The landscape of pharmaceutical innovation is continuously evolving, and drug repositioning is poised to play an increasingly central role in shaping its future. Several key trends and opportunities are emerging that will further enhance its impact.

8.1. Personalized Medicine and Targeted Therapies

The shift towards personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to an individual’s unique genetic and molecular profile, is accelerating rapidly . Drug repurposing is a natural fit for this trend. By leveraging advancements in genomics, proteomics, and AI, researchers can identify existing drugs that are most likely to be effective for specific patient subgroups based on their disease biomarkers or genetic mutations . This approach minimizes trial-and-error prescribing, improves therapeutic outcomes, and reduces adverse effects.

For example, AI models trained on multi-omics data can predict drug response based on genetic markers, enabling more precise patient stratification for repurposed therapies . This allows for the repurposing of drugs for niche indications within a broader disease, or for specific genetic subtypes of a disease, maximizing efficacy for targeted patient populations . The growth of the personalized medicine market, projected to surpass $950 billion by 2030, will continue to drive demand for such tailored repurposing approaches .

8.2. Open Science and Global Collaboration

The complexity and scale of drug repurposing necessitate a collaborative ecosystem. Open science initiatives are increasingly fostering transparency, data sharing, and collaboration across academic institutions, pharmaceutical companies, and patient advocacy groups . Platforms like Drug Repurposing Central exemplify this trend, providing open access to research results, preprints, and open peer review mechanisms .

Global collaborations, such as the REPO4EU Horizon Europe project, are building platforms to streamline drug repurposing efforts across continents . These initiatives recognize that pooling resources, expertise, and diverse datasets can accelerate discovery and overcome barriers that individual entities might face, particularly for rare or neglected diseases . This collective approach enhances reproducibility, digital interoperability, and ultimately, the efficiency of research, leading to faster development of new treatments . The increasing engagement of patient advocacy groups, who often directly fund and shape research for unmet needs, further underscores the power of multi-stakeholder collaboration in this field .

8.3. Sustainable Drug Development and Public Health Impact

Drug repurposing is inherently a more sustainable approach to drug development compared to de novo discovery. By maximizing the utility of existing drugs, it reduces the need for extensive resources and investments in creating entirely new chemical entities, which often have a significant environmental footprint due to manufacturing processes and waste generation . This lean and agile alternative leverages prior investments in R&D, aligning pharmaceutical innovation with broader sustainability goals .

Beyond environmental sustainability, drug repurposing has a profound public health impact. It offers a viable pathway to address unmet medical needs, particularly for rare diseases where traditional drug development is often economically unfeasible . The ability to bring new treatments to patients faster and at a lower cost can significantly improve access to essential medicines, especially in resource-limited settings. The rapid deployment of repurposed drugs during public health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, vividly demonstrates this critical societal value . This approach promotes equitable access and contributes to a more resilient global healthcare system.

Key Takeaways: Strategic Imperatives for Pharma Leaders

Drug repositioning is no longer a peripheral strategy but a central pillar of modern pharmaceutical innovation, offering compelling advantages for businesses seeking to maximize profitability and societal impact.

- Embrace Repurposing as a Core R&D Strategy: Recognize that drug repurposing is a de-risked, cost-efficient, and accelerated pathway to market compared to traditional de novo drug discovery. Allocate dedicated resources and expertise to identify and develop new indications for existing assets.

- Invest in Advanced Methodologies: Leverage the power of AI, machine learning, knowledge graphs, and multi-omics data integration to systematically identify promising repurposing candidates. Prioritize the use of advanced preclinical models like organ-on-a-chip technology and CRISPR screening to improve translational accuracy and reduce late-stage failures.

- Master the Regulatory Landscape: Develop deep expertise in navigating expedited pathways like the FDA’s 505(b)(2). Proactively engage with regulatory bodies to address challenges related to old toxicology data, dosage adjustments, and formulation changes. Advocate for policy reforms that incentivize label expansion for generic drugs.

- Innovate IP Beyond the Molecule: Understand that intellectual property protection for repurposed drugs extends beyond method-of-use patents. Strategically pursue secondary patents for new formulations, dosages, and combinations to prolong market exclusivity and create differentiated products. Utilize patent analytics tools like DrugPatentWatch to gain competitive intelligence and identify IP white space.