Section 1: The Regulatory Compact: Establishing the Framework for Generic Drugs

The modern pharmaceutical landscape, characterized by the widespread availability of low-cost generic drugs, is not a product of chance. It is the result of a deliberate and complex regulatory architecture designed to balance two competing, yet essential, societal goals: fostering therapeutic innovation and ensuring affordable access to medicine. The perception of generic drug safety is inextricably linked to the integrity and rigor of this framework. Understanding this system, both in the United States and abroad, is the necessary first step in any critical evaluation of whether generic drugs are less safe than their brand-name counterparts. The evidence demonstrates that the system is not an ancillary process but a carefully constructed compact that has fundamentally reshaped the pharmaceutical market.

1.1 The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Genesis of the Modern Generic Market in the U.S.

Prior to 1984, the generic drug market in the United States was nascent and fraught with prohibitive barriers. Generic manufacturers were often required to conduct their own extensive and expensive clinical trials to independently establish the safety and effectiveness of their products, a duplicative process that largely defeated the purpose of creating a low-cost alternative.1 This regulatory environment changed profoundly with the passage of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, more commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.3 This landmark legislation, sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, was a grand compromise designed to restructure the economic and legal dynamics between innovator and generic pharmaceutical companies.1

The Act’s core purpose was twofold: to streamline the market entry of lower-cost generic drugs and, simultaneously, to compensate innovator companies for the patent life consumed during the lengthy U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory review process.5 To achieve the first goal, Hatch-Waxman created the modern Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, codified under Section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act.1 The ANDA is termed “abbreviated” because it allows a generic manufacturer to rely on the FDA’s previous finding of safety and effectiveness for the original, brand-name drug—officially known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD).6 This critical provision eliminated the need for generic firms to repeat costly and ethically questionable clinical trials in humans, a change that single-handedly made the development of generic medicines economically viable.1

To achieve its second goal of preserving incentives for innovation, the Act provided brand-name manufacturers with several key benefits. It established a mechanism for patent term restoration, allowing companies to reclaim a portion of the patent time lost during the FDA’s New Drug Application (NDA) review.5 It also codified periods of market exclusivity, independent of patent status, such as a five-year exclusivity for New Chemical Entities (NCEs), during which the FDA cannot approve a generic version.5 For their part, generic manufacturers were granted a “safe harbor” provision, protecting them from patent infringement lawsuits while conducting the development work necessary to prepare an ANDA submission.1

The impact of this legislative compact has been transformative. Before Hatch-Waxman, generic drugs constituted a mere 19% of all prescriptions dispensed in the U.S..1 Today, they account for approximately 90% of prescriptions filled, generating hundreds of billions of dollars in annual savings for the healthcare system and providing the foundation for widespread patient access to essential medicines.1

A critical examination of the Hatch-Waxman Act reveals that its structure inherently fosters a litigious environment. By linking generic approval directly to the patent status of the brand-name drug and creating powerful incentives for patent challenges—most notably, a 180-day period of market exclusivity for the first generic company to successfully file a “Paragraph IV” certification challenging a brand’s patent—the legislation institutionalized a “legal minefield”.5 This framework ensures that the path to market for a generic drug is frequently a high-stakes legal and strategic battle in addition to a scientific one.14 The safety and availability of a generic medication can therefore be influenced not just by its scientific merit but by the outcomes of complex patent litigation. This dynamic shapes the entire industry, incentivizing strategies like “patent thicketing” by brand-name firms to prolong monopoly protection and aggressive litigation by generic firms to accelerate market entry.15

Furthermore, the regulatory structure established by the Act is the direct driver of the “patent cliff” phenomenon, where a brand-name drug experiences a sudden and precipitous decline in revenue upon the expiration of its market exclusivity.17 The Act creates a defined period of monopoly for the brand, followed by an abrupt loss of that protection, which allows multiple generic competitors to enter the market simultaneously, triggering intense price competition.20 This economic reality is inseparable from the safety debate. The immense financial pressure of an approaching patent cliff can incentivize brand-name companies to employ strategies that delay generic entry, which may include public relations efforts designed to cast doubt on the quality and safety of forthcoming generics.16 Conversely, the fierce price erosion that follows generic entry places significant pressure on generic manufacturers to maintain profitability, raising questions about the long-term sustainability of high-quality manufacturing—a concern the FDA itself has acknowledged.23 The regulatory framework is thus not merely a set of procedural rules but the very engine of the economic and competitive forces that frame the public discourse on generic drug safety.

1.2 The FDA’s ANDA Review Process: The Modern Gauntlet

The ANDA submitted to the FDA is a comprehensive scientific dossier designed to prove that a proposed generic product is a high-quality, equivalent copy of the RLD.9 These applications are typically compiled in the electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) format and submitted via the FDA’s Electronic Submission Gateway, a process intended to streamline review.6 The review itself is a rigorous, multi-faceted process conducted by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), with primary responsibility falling to the Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) and the Office of Safety and Clinical Evaluation (OSCE).6

An ANDA must provide convincing evidence to meet a series of stringent requirements. The applicant must demonstrate that the generic drug is pharmaceutically equivalent and bioequivalent to the RLD. Beyond these core scientific tenets, the manufacturer must prove it is capable of making the drug correctly and consistently, in full compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). The ANDA must also show that the drug is stable over its proposed shelf life, that its container and closure system are appropriate, and that its labeling is essentially the same as the RLD’s, with certain permissible differences.8

The regulatory relationship between a manufacturer and the FDA does not cease upon approval. The agency maintains lifecycle oversight, and manufacturers are required to report any post-approval changes to the drug product or its manufacturing process. These changes are categorized by their potential impact on the drug’s safety or efficacy. Major changes, such as a significant modification to the manufacturing process, require a Prior Approval Supplement and cannot be implemented until the FDA reviews and approves the submission. Moderate changes that do not significantly affect safety can be implemented sooner under a Changes Being Effected (CBE) supplement, with concurrent notification to the FDA. Minor changes can be documented in annual reports submitted to the agency.8 This system ensures continuous oversight and accountability throughout a generic drug’s market life.

1.3 The European Medicines Agency (EMA) Framework: A Comparative Perspective

While procedural details differ, the scientific principles underpinning generic drug approval in the European Union are closely aligned with those of the FDA, reflecting a broad international consensus on what constitutes a safe and effective generic medicine. The European Medicines Agency (EMA), along with national competent authorities in member states, oversees a system that requires a generic medicine to have the same qualitative and quantitative composition of active substance(s), the same pharmaceutical form (e.g., tablet, injectable), and demonstrated bioequivalence to a “reference medicinal product” that has been authorized in the EU.28

A key procedural difference is the availability of multiple approval pathways in the EU. A generic of a centrally authorized product can gain approval for the entire EU market through the centralized procedure, managed directly by the EMA. This route is also available for generics that constitute a significant therapeutic, scientific, or technical innovation.28 However, the vast majority of generic medicines in the EU are approved via non-centralized routes, including the Decentralised Procedure (DCP) and the Mutual Recognition Procedure (MRP), which involve coordination and cooperation between the regulatory agencies of individual member states.30

The European framework also formally includes the concept of a “hybrid application.” This pathway is for medicines that do not strictly meet the definition of a generic—for example, because they have a different strength, a different route of administration, or a new therapeutic indication compared to the reference product. These applications rely in part on the data from the reference product but must be supplemented with new pre-clinical or clinical data to bridge the differences.29 This provides a flexible regulatory path for products that represent incremental innovations over existing medicines. The parallel existence of these robust systems in the U.S. and Europe underscores that the core scientific requirements for generic approval—sameness of active ingredient, quality manufacturing, and proven bioequivalence—are not arbitrary but represent a global regulatory standard.

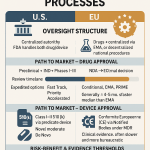

Table 1: Comparison of Generic Drug Approval Frameworks: FDA vs. EMA

| Feature | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | European Medicines Agency (EMA) & National Authorities |

| Governing Legislation/Body | Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch-Waxman Act); oversight by FDA/CDER 1 | Directive 2001/83/EC; oversight by EMA and/or National Competent Authorities 28 |

| Primary Application Type | Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) 6 | Generic Application; Hybrid Application for non-standard generics 28 |

| Core Scientific Requirement | Bioequivalence to a Reference Listed Drug (RLD) 6 | Bioequivalence to a Reference Medicinal Product authorized in the EU 28 |

| Clinical Data Requirement | Relies on RLD’s established safety and efficacy data; no new clinical trials required for standard generics 1 | Relies on reference product’s established data; no new trials for standard generics; bridging data required for hybrid applications 29 |

| Approval Pathways | Single federal pathway for all generics 6 | Multiple pathways: Centralised (via EMA), National, Mutual Recognition (MRP), and Decentralised (DCP) 28 |

| Manufacturing Standard | Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) as per 21 CFR Parts 210 & 211 8 | Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), aligned with international standards 33 |

Section 2: The Scientific Foundation of “Sameness”: Deconstructing Therapeutic Equivalence

For a generic drug to be considered a safe and effective substitute for a brand-name product, it must be, for all clinical purposes, the “same.” The regulatory definition of this sameness is not casual; it is a precise, hierarchical concept built upon layers of scientific evidence. At its heart is the principle of therapeutic equivalence, a designation that allows pharmacists and clinicians to substitute a generic for a brand with the full expectation of achieving the same clinical effect and safety profile. Deconstructing this concept and the rigorous science used to establish it is essential for dispelling common myths and understanding the true relationship between brand and generic medicines.

2.1 The Hierarchy of Equivalence: From Pharmaceutical to Therapeutic

The journey to regulatory approval and market substitution involves clearing three distinct but related hurdles of equivalence, each more stringent than the last.

First, a generic must be a pharmaceutical equivalent to its brand-name counterpart. This is the foundational requirement, stipulating that the two products must contain the identical active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), in the identical dosage form (e.g., tablet, injectable), for the identical route of administration (e.g., oral, topical), and at the identical strength or concentration (e.g., 250 mg).26 At this stage, differences are permitted in characteristics that are not expected to affect therapeutic performance, such as the product’s shape, color, scoring configuration, and, most notably, its inactive ingredients, or excipients.34 A product that differs in the active ingredient (e.g., a different salt or ester, such as tetracycline hydrochloride versus tetracycline phosphate) is not a pharmaceutical equivalent but a

pharmaceutical alternative.34

Second, and most critically, the generic must demonstrate bioequivalence. This concept is built upon the definition of bioavailability, which is the rate and extent to which an active ingredient is absorbed from a drug product and becomes available at the site of action in the body.36 Two drug products are considered bioequivalent if there is no significant difference in their rate and extent of bioavailability when they are administered to subjects under similar conditions.37 This is the scientific linchpin of the generic approval process. The entire regulatory system for generics is constructed upon what has been termed the “fundamental bioequivalence assumption”: the hypothesis that if two pharmaceutically equivalent products are proven to be bioequivalent, they can be assumed to be therapeutically equivalent.38 This means that if a generic drug delivers the same amount of the active ingredient into the bloodstream over the same period of time as the brand-name drug, it will produce the same clinical effects—both beneficial and adverse. The remainder of this report, particularly the review of clinical evidence in Section 4, serves as a real-world test of this fundamental assumption.

Finally, if a drug product is both a pharmaceutical equivalent and has been proven to be bioequivalent, the FDA designates it as a therapeutic equivalent. This is the highest level of equivalence and signifies that the generic product can be expected to have the same clinical effect and safety profile as the brand-name drug when administered to patients under the conditions specified in the labeling.34 Products that the FDA has determined to be therapeutically equivalent are listed in its official publication,

Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, commonly known as the “Orange Book”.6 This designation serves as the official guide for state laws that permit or encourage pharmacists to substitute a lower-cost generic for a prescribed brand-name drug.34

2.2 The Bioequivalence Study: A Closer Look at the Data

The demonstration of bioequivalence is not a theoretical exercise; it is a clinical trial with a specific design and rigorous statistical criteria. The typical bioequivalence (BE) study is a randomized, single-dose, crossover trial conducted in a small cohort of healthy adult volunteers, usually between 24 and 48 individuals.6 In a crossover design, each volunteer acts as their own control, receiving both the generic (test) drug and the brand-name (reference) drug on separate occasions, separated by a “washout” period to ensure the first drug is completely eliminated from their system before the second is administered.24 After each administration, a series of blood samples are drawn over a set period to measure the concentration of the active ingredient in the blood plasma.6

From these plasma concentration-time curves, two key pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters are derived to quantify bioavailability 24:

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): This value represents the total drug exposure over time, calculated as the area under the plasma concentration-time graph. It is the primary measure of the extent of drug absorption.

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration): This is the highest concentration that the drug reaches in the bloodstream. It is the primary measure of the rate of drug absorption.

The most persistent and damaging myth surrounding generic drugs stems from a misunderstanding of the statistical criteria used to analyze these PK parameters. The common misconception is that a generic drug’s active ingredient can be anywhere from 20% less to 25% more than the brand’s, suggesting a potential 45% variance that could have profound clinical consequences.40 This interpretation is factually incorrect.

The 80% to 125% range is not a measure of the allowed content of the active ingredient in the pill. It is the prespecified acceptance boundary for the 90% Confidence Interval (CI) of the ratio of the population geometric means (Test/Reference) for both AUC and Cmax.24 A confidence interval is a statistical range that is likely to contain the true population average. For the FDA to conclude that two products are bioequivalent, the

entire 90% CI for the ratio of the means must fall completely within the 80% to 125% window. For this to occur, the observed average values for the generic and brand products must be very close to each other. A large-scale analysis of over 2,000 bioequivalence studies submitted to the FDA found that the average difference in absorption (both AUC and Cmax) between the generic and brand-name product was only about 3.5%.41 This level of minor variability is considered clinically insignificant and is comparable to the batch-to-batch variability observed when comparing two different manufacturing lots of the same brand-name drug.43

Therefore, the 80%-125% standard should not be viewed as a measure of permissible potency but as a statistical risk-management tool. It is designed to provide a very high degree of confidence (a 90% CI) that the true difference in average bioavailability between the generic and brand populations is small and clinically irrelevant. This reframing is essential for building trust, as it shifts the narrative from a misleading “the FDA allows generics to be 20% weaker” to a more accurate “the FDA employs a strict statistical test to ensure that any difference between the average performance of the generic and the brand is highly unlikely to be clinically meaningful.”

2.3 Beyond Standard Studies: Biowaivers and Complex Generics

The regulatory framework is adaptable to the specific characteristics of different drug products. For certain types of drugs where in-vivo bioavailability is highly predictable and poses little risk—such as parenteral solutions for injection or simple oral solutions—the FDA may grant a “biowaiver”.36 This allows the manufacturer to forgo human BE studies, provided the generic product is demonstrated to be qualitatively (Q1) and quantitatively (Q2) the same as the brand, meaning it contains the same inactive ingredients in the same concentrations.36

Conversely, the pharmaceutical landscape is increasingly populated by “complex generics,” which are products that are harder to copy and for which traditional BE studies may be insufficient. These can include drug-device combination products (like inhalers), long-acting injectables, or drugs with complex formulations.1 The FDA, through its science and research program funded by the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), has dedicated significant resources to developing new, product-specific guidances and analytical tools to establish bioequivalence for these more challenging products, ensuring the pathway to market remains scientifically rigorous as technology evolves.46

Table 2: Key Definitions in Pharmaceutical Equivalence

| Term | Definition | Source(s) |

| Pharmaceutical Equivalent | Drug products that contain the identical active ingredient(s), in the identical dosage form and route of administration, and are identical in strength or concentration. They may differ in characteristics such as shape, scoring, release mechanisms, packaging, and excipients. | 34 |

| Pharmaceutical Alternative | Drug products that contain the identical therapeutic moiety or its precursor but not necessarily in the same amount, dosage form, or the same salt or ester (e.g., tetracycline hydrochloride vs. tetracycline phosphate complex). | 34 |

| Bioavailability | The rate and extent to which the active ingredient or active moiety is absorbed from a drug product and becomes available at the site of action. | 36 |

| Bioequivalent | The absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient in pharmaceutical equivalents becomes available at the site of drug action when administered at the same molar dose under similar conditions. | 37 |

| Therapeutic Equivalent | Drug products that are pharmaceutical equivalents and are bioequivalent. They can be expected to have the same clinical effect and safety profile when administered to patients under the conditions specified in the labeling. | 34 |

Section 3: The Unseen Standard: Manufacturing, Quality, and Global Supply Chains

While the scientific principles of equivalence form the theoretical basis for generic drug safety, the practical assurance of that safety rests on a different, though equally critical, foundation: the quality of the manufacturing process. The safety of any drug, whether it carries a well-known brand name or is a low-cost generic, is fundamentally dependent on the integrity of its production. The regulatory framework recognizes this by imposing a single, universal standard of quality on all manufacturers. However, the realities of a globalized supply chain introduce complexities and potential vulnerabilities that challenge regulatory oversight and shape the safety debate.

3.1 Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP): A Universal Mandate

The bedrock of pharmaceutical quality control in the United States is the FDA’s Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) regulations, codified primarily in Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Parts 210 and 211.24 These regulations establish the minimum requirements for the methods, facilities, and controls used in the manufacturing, processing, packing, and holding of all drug products.32 Their purpose is to ensure that every drug product is safe for use and possesses the identity, strength, quality, and purity it claims to have.32

Crucially, the cGMP mandate is universal. These exacting standards apply equally to both brand-name and generic drug manufacturers.27 The FDA’s approval process for any new or generic drug application includes a rigorous review of the manufacturer’s ability to comply with cGMP.26 FDA assessors and investigators evaluate whether a firm has the necessary facilities, equipment, and validated processes to manufacture the drug consistently and reliably before approval is granted.32

The scope of cGMP is comprehensive, demonstrating that quality is not merely confirmed by testing the final product but is built into every stage of the lifecycle.24 Key pillars of the regulations include:

- Quality Management Systems: A structured approach to managing quality and risk.

- Personnel: Requirements for adequate training, experience, and qualifications for all staff involved in manufacturing.

- Facilities and Equipment: Standards for the design, maintenance, and calibration of buildings and equipment to prevent contamination and errors.

- Control of Materials: Strict procedures for the receipt, testing, storage, and handling of all raw materials and components, including the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API).

- Production and Process Controls: The establishment of written procedures and in-process controls for every step of manufacturing to ensure consistency and prevent deviations.

- Laboratory Controls: Rigorous requirements for testing raw materials, in-process materials, and finished products using validated analytical methods.

- Packaging and Labeling Controls: Strict controls to prevent mix-ups and ensure that products are accurately labeled with correct information and expiration dates.

- Documentation and Record-Keeping: Meticulous and comprehensive records of every aspect of manufacturing, ensuring traceability, transparency, and accountability.24

3.2 The Reality of Globalized Manufacturing and FDA Oversight

The modern pharmaceutical supply chain is a complex global network. A significant portion of the drugs consumed in the United States, and/or their essential Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), are manufactured in facilities located overseas.49 India and China, in particular, are major hubs for pharmaceutical production, with India being one of the largest suppliers of finished generic medicines to the U.S. market.50

The FDA’s cGMP authority extends to these foreign facilities. The agency is responsible for inspecting all manufacturing sites, whether domestic or international, that produce drugs intended for U.S. consumption.47 The FDA asserts that it conducts thousands of inspections annually and will not permit drugs to be made in facilities that fail to meet its standards.47

However, this global oversight presents formidable logistical challenges. Recent history has revealed instances of significant quality control lapses at foreign manufacturing sites. The most prominent example is the discovery of carcinogenic nitrosamine impurities, such as N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), in several widely used generic drugs, including the blood pressure medication valsartan and the heartburn medication ranitidine.49 These contamination events, which also affected some brand-name products, often originated from overseas API or finished drug manufacturers and led to widespread recalls.49 Furthermore, critics and government reports have raised concerns that the FDA’s inspection resources are stretched thin, with some analyses suggesting that hundreds of foreign facilities exporting to the U.S. had never been inspected by the agency.49 These events highlight a real-world vulnerability in the global supply chain.

The safety debate must therefore move beyond a simplistic “brand versus generic” dichotomy to a more nuanced discussion of “high-quality manufacturer versus low-quality manufacturer,” irrespective of a product’s market status. The cGMP regulations are universal, and a quality control failure can occur at any facility, brand or generic, domestic or foreign. The critical variable for ensuring the ongoing safety of a medication is not the name on the box, but the culture of quality and rigorous execution of cGMP within a specific manufacturing plant. This reframes the central question from “Are generics less safe?” to a more precise and relevant inquiry: “What are the inherent risks in the globalized pharmaceutical manufacturing system, how are they being managed, and how do they apply to all drugs?”

This globalization creates a fundamental paradox of cost versus risk. The immense cost savings that generic drugs provide to the healthcare system—savings that are a core public policy objective—are enabled, in part, by a globalized supply chain that leverages lower-cost manufacturing in regions like Asia.50 Yet, this same globalization introduces the significant challenge of effective regulatory oversight across thousands of facilities in dozens of countries.49 There is an inherent tension between the goal of lowering drug prices through global competition and the goal of ensuring a perfectly secure and monitored supply chain. While a generic drug’s

design is proven safe and equivalent through the ANDA process, its ongoing safety is contingent on the integrity of this complex international system—a systemic risk that applies to the entire modern pharmaceutical industry but is often disproportionately and unfairly attributed solely to generics.

3.3 The Myth of Inferior Facilities

A persistent myth that fuels public skepticism is the notion that generic drugs are produced in substandard facilities while brand-name drugs are made in state-of-the-art plants.47 The FDA directly refutes this, stating that generic firms operate facilities that are comparable to those of brand-name firms, as both must meet the same cGMP standards to gain and maintain approval.47

The distinction is further blurred by the deeply interconnected nature of the pharmaceutical industry. Brand-name manufacturers are major players in the generic market themselves, accounting for an estimated 50% of all generic drug production in the U.S..47 It is common practice for innovator companies to manufacture and sell generic versions of their own products (often called “authorized generics”) or to produce generics for other companies. Some firms, like Pfizer, explicitly state that they maintain responsibility for and continue to monitor the quality and safety of their medicines even after they lose patent protection and become generics.55 This reality completely undermines the simplistic and misleading narrative of two separate and unequal manufacturing worlds.

Section 4: The Clinical Verdict: A Synthesis of Evidence from Major Therapeutic Areas

While regulatory frameworks and manufacturing standards provide the foundation for safety, the ultimate test of equivalence lies in clinical outcomes. The central question is whether the “fundamental bioequivalence assumption”—the principle that proven bioequivalence implies therapeutic equivalence—holds true in real-world patient populations. A systematic review of the clinical evidence, from large-scale meta-analyses to deep dives into the most contentious drug classes, provides a clear and compelling answer. The overwhelming weight of high-quality scientific evidence supports the conclusion that generic and brand-name drugs are clinically equivalent, though specific nuances, particularly concerning drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, warrant careful consideration.

4.1 The Broad Consensus: Evidence from Large-Scale Meta-Analyses

The most powerful evidence for the clinical equivalence of generic drugs comes from large-scale studies and meta-analyses, particularly in therapeutic areas involving millions of patients and critically important outcomes. Cardiovascular medicine is a prime example. A landmark meta-analysis published in 2015, which synthesized data from 74 randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular drugs, delivered a striking verdict. For both “soft” efficacy outcomes (such as changes in LDL cholesterol or systolic blood pressure) and “hard” efficacy outcomes (such as major adverse cardiovascular events and death), 100% of the included trials showed non-significant differences between the generic and brand-name drugs.56 The aggregate effect size for all outcomes hovered near zero, indicating no evidence of superiority for either group. The study’s authors concluded that the analysis strengthens the evidence for clinical equivalence and should reassure physicians and healthcare organizations about the widespread use of generic cardiovascular drugs.56

This finding is corroborated by other major studies. A large-scale observational study from Austria, analyzing real-world data from millions of patient records, found that for chronic metabolic diseases like hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, generic medications were associated with clinical outcomes that were at least as good as, and in some cases statistically superior to, their branded counterparts.57 Another comprehensive review of 47 studies focusing on cardiovascular drugs similarly concluded that the available evidence does not support the notion that brand-name products are superior to generics.58 These broad findings are consistent with the underlying pharmacokinetic data; as previously noted, the average difference in absorption between generics and brands is a clinically insignificant 3.5%, a level of variability also seen between different batches of the same brand-name drug.42

When the full body of clinical data is organized according to the hierarchy of evidence, a distinct pattern emerges. The highest and most reliable levels of evidence—large-scale meta-analyses of randomized trials and well-designed, large cohort studies—consistently find no clinically meaningful difference in safety or efficacy between generic and brand-name drugs.56 In contrast, findings of generic inferiority or negative outcomes are more likely to originate from lower levels of evidence, such as anecdotal case reports, small or poorly controlled observational studies, or research with potential conflicts of interest, such as industry sponsorship.60 This suggests that much of the perceived “controversy” over generic safety is a result of giving undue weight to lower-quality evidence while discounting the robust conclusions from more rigorous study designs. An expert evaluation must prioritize the findings from the highest levels of evidence, which overwhelmingly support the principle of therapeutic equivalence.

4.2 The Challenge of Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) Drugs

The most intense debate over generic substitution centers on a specific class of medications known as Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs. These are defined as drugs for which small differences in dose or blood concentration may lead to serious therapeutic failures (e.g., organ transplant rejection, breakthrough seizures) or severe adverse drug reactions (e.g., toxicity, life-threatening bleeding).62 This category includes critical medications like antiepileptics, the anticoagulant warfarin, the immunosuppressant tacrolimus, and the thyroid hormone levothyroxine.

The concern is that even the small, legally permissible variations in bioavailability between formulations could, for these sensitive drugs, be clinically significant for some patients. However, it is crucial to recognize that the FDA is aware of this heightened risk and, as a result, imposes more stringent standards on generic NTI drugs than on other medications. For example, the acceptable range for the API content in a batch (the quality assay) is tightened from the standard 90%-110% to a stricter 95%-105%. Furthermore, the bioequivalence standards themselves are often tightened to ensure an even greater degree of similarity to the brand-name product.63 This heightened regulatory scrutiny is a key counterargument to the claim that the FDA is cavalier about the risks associated with substituting NTI drugs.

The nuanced clinical debate over NTI drugs is best understood not as a question of inherent generic inferiority, but as a question of managing inter-individual variability. Even when two drug formulations are proven to be equivalent on a population average, there can still be slight pharmacokinetic variations in how a specific individual absorbs and metabolizes them. For most drugs with a wide therapeutic window, this minor variability is clinically irrelevant. For an NTI drug, however, this small inter-individual difference upon switching from one formulation to another could theoretically shift a vulnerable patient’s blood levels enough to matter. This leads to the prudent clinical recommendation for closer monitoring during the act of switching—whether from brand-to-generic, generic-to-generic, or even generic-to-brand. This vigilance is not an admission that the generic product is flawed; rather, it is a risk management strategy that correctly identifies the moment of transition as the point of potential risk that requires careful clinical oversight. This critical distinction reframes the NTI debate away from a false generic-versus-brand dichotomy and toward a more sophisticated understanding of clinical pharmacology.

4.3 Case Study: Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs)

For decades, the epilepsy community has harbored significant concerns about generic substitution, fueled by anecdotal reports from patients and physicians of breakthrough seizures following a switch from a brand-name to a generic AED.65 These concerns prompted the funding of a landmark clinical trial to address the issue head-on. The EQUIGEN study, a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial published in

The Lancet Neurology, was specifically designed to test a worst-case scenario. Researchers identified the two most disparate FDA-approved generic versions of the AED lamotrigine—one that absorbed relatively quickly and one that absorbed more slowly, but both well within bioequivalence standards—and had patients with epilepsy switch between them.59 The results were definitive: the pharmacokinetic measures of the two generics were found to be equivalent in patients, and there were

no significant differences in seizure frequency, adverse events, or other clinical outcomes between the two formulations.59

Observational data on AEDs have been more conflicting, but recent, well-designed studies have added important nuance. One large case-crossover study sought to disentangle the effect of switching manufacturers from the effect of simply getting a prescription refilled. It found that the act of refilling a generic AED prescription was associated with a small but statistically significant 8% increase in the odds of a seizure-related hospital visit. However, when a patient switched to a different generic manufacturer during that refill, there was no additional risk beyond that associated with the refill itself.65 This clever design suggests that factors related to the refilling process—such as a brief interruption in adherence or psychological factors—may play a larger role than any chemical difference between the pills.

4.4 Case Study: Warfarin (an NTI Anticoagulant)

Warfarin is a classic NTI drug where maintaining a stable level of anticoagulation, measured by the International Normalized Ratio (INR), is critical to prevent both life-threatening clots and dangerous bleeding. A systematic review of the literature on brand versus generic warfarin found that randomized crossover trials consistently showed no statistically significant difference in the average INR or in the number of dosage adjustments required after patients were switched between brand and generic formulations.68 A series of n-of-1 trials, a powerful design that studies treatment effects within a single patient, also found no difference in INR variability between brand and generic warfarin.70

However, the review also highlighted a key nuance. While the population-level data from randomized trials was reassuring, some observational studies reported changes in INR control at the individual patient level following a switch.68 This body of evidence leads to a balanced and clinically sound conclusion: generic warfarin products are safe and effective substitutes for the brand-name product, but because of the potential for small variations in individual response, it is reasonable and prudent for clinicians to conduct closer INR monitoring in the period immediately following any switch between different warfarin formulations.68

4.5 Case Study: Levothyroxine (an NTI Thyroid Hormone)

Levothyroxine, used to treat hypothyroidism, is another NTI drug where prescriber hesitancy about generic substitution has been common, despite its widespread use.72 To address these concerns, the FDA collaborated with researchers to conduct a large-scale study using real-world evidence from administrative health claims. This retrospective cohort study compared thousands of patients starting on generic levothyroxine for the first time with thousands starting on the brand-name version. The study found

similar attainment of normal thyroid status, as measured by levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), regardless of whether the patient received the generic or brand-name product.73 A separate large study using a similar design found

no difference in the rates of major cardiovascular events (such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or stroke) between patients taking generic versus brand-name levothyroxine.74

It is important to acknowledge the existence of conflicting evidence. One large, retrospective real-world study, sponsored by the manufacturer of the brand-name product Synthroid, found that a small but statistically significant higher proportion of patients achieved their target TSH goal when treated with Synthroid compared to generic levothyroxine (78.5% vs. 77.2%).61 While the clinical significance of this small difference is debatable, its existence highlights the potential for funding bias in research and underscores the need for clinicians and policymakers to critically evaluate the totality of evidence, giving appropriate weight to study design and potential conflicts of interest.

Table 3: Summary of Major Clinical Studies and Meta-Analyses on Generic vs. Brand-Name Drug Outcomes

| Drug Class / Indication | Study Type & Reference | Key Findings (Efficacy & Safety) | Conclusion on Equivalence |

| Cardiovascular Drugs | Meta-analysis of 74 RCTs 56 | 100% of trials showed non-significant differences for both soft (e.g., BP, LDL) and hard (e.g., death, MACE) clinical outcomes. Aggregate effect size was negligible. | Strong evidence for clinical equivalence. |

| Antiepileptics (Lamotrigine) | Randomized, double-blind, crossover trial (EQUIGEN) 59 | No significant differences in pharmacokinetic measures, seizure frequency, or adverse events between two disparate generic versions in patients with epilepsy. | Strong evidence supports bioequivalence and clinical equivalence between different generic formulations. |

| Anticoagulants (Warfarin) | Systematic review of RCTs and observational studies 68 | RCTs showed no difference in mean INR or dose adjustments. Some observational data suggest individual variability. | Evidence supports population-level safety and efficacy. Closer monitoring on switch is recommended as a prudent measure for individual patients. |

| Thyroid Hormone (Levothyroxine) | Large retrospective real-world evidence study (FDA) 73 | Similar attainment of normal TSH levels and similar rates of cardiovascular events in patients initiated on generic vs. brand-name levothyroxine. | Strong real-world evidence supports therapeutic equivalence for initial therapy. |

Section 5: Mind Over Medicine: The Role of Perception and the Nocebo Effect

The robust body of scientific and clinical evidence supporting the equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs stands in stark contrast to a persistent undercurrent of skepticism among some clinicians and a significant portion of the public. This gap between evidence and perception cannot be ignored, as it has tangible consequences for patient health. The discrepancy is largely explained not by pharmacology, but by psychology. A combination of misinformation, cognitive biases, and the powerful and often underestimated “nocebo effect” can lead to real, negative health outcomes that are then incorrectly attributed to the generic medicine itself.

5.1 The Persistence of Doubt: Physician and Patient Perceptions

Despite decades of successful use and regulatory oversight, surveys consistently reveal that a meaningful number of both healthcare providers and patients harbor negative perceptions about generic drugs. A systematic review aggregating data from 52 different studies found that nearly 29% of doctors and 24% of pharmacists viewed generics as less effective than branded medication.75 Even more concerning, 24% of doctors believed generics caused more side effects.75 In some regions, the knowledge gap is profound; a study of physicians in Iraq found that the majority held incorrect beliefs about generic drug standards, with only about 27% correctly identifying that generics are required to be therapeutically equivalent to brands.76

These negative perceptions are even more prevalent among the general public. The same systematic review found that nearly 36% of lay people believed generics were less effective, and 34% felt negatively about the practice of generic substitution.75 This skepticism is often rooted in common cognitive biases and misinformation, such as the deeply ingrained belief that higher cost equates to higher quality.42 The lower price of generics, which is their primary public health benefit, paradoxically becomes a source of suspicion about their worth.62

5.2 The Nocebo Effect: When Negative Expectations Create Real Symptoms

This gap between evidence and perception provides fertile ground for the nocebo effect. Often described as the “evil twin” of the better-known placebo effect, the nocebo effect is the phenomenon whereby a patient’s negative expectations about a treatment lead to the experience of real, adverse symptoms that are not caused by the pharmacological properties of the intervention itself.78 These are not imaginary symptoms; the nocebo response is mediated by genuine neurobiological pathways, including the activation of stress and anxiety circuits (such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis) and alterations in pain perception pathways, which can produce measurable physiological effects.78

Generic substitution is a textbook scenario for inducing a nocebo response, driven by several powerful triggers:

- Provider Communication: The way a healthcare professional frames the switch is paramount. A physician or pharmacist who expresses hesitation, uses cautious language, or over-emphasizes potential side effects can inadvertently plant a negative expectation in the patient’s mind.79 Research has shown that the simple act of informing patients about possible side effects can dramatically increase the rate at which those side effects are reported.80

- Change in Physical Appearance: Perhaps the most potent trigger is the change in a pill’s physical characteristics. When a patient who has been taking a familiar round, white pill for years is suddenly given a new, oval, blue pill, it provides a concrete, visible signal that the medication is “different”.43 This change can activate latent anxieties and negative beliefs about generics, leading the patient to become hypervigilant and attribute any subsequent background symptom (a headache, fatigue, an upset stomach) to the “new” medicine.65

- Prior Negative Experiences and Misinformation: A patient’s past negative experience with a medication can become a conditioned response, leading them to anticipate a similar bad outcome with any new formulation.78 This can be compounded by negative information gleaned from friends, family, or the internet, which reinforces the belief that generics are inferior.

The “safety” of a generic drug is therefore not solely a function of its chemical composition. It is partially determined by the narrative surrounding its use. A drug’s experienced safety profile is a product of both its pharmacology and the patient’s mindset, which is profoundly shaped by the cues and information they receive from their environment—most critically, from their doctor, their pharmacist, and the appearance of the pill itself. This means a clinician who confidently and positively frames a switch to a generic (“This is the exact same medicine that works in the same way, just in a different package”) can actively contribute to a better safety outcome and higher adherence than a clinician who communicates hesitancy (“The pharmacy is switching you to a generic; let me know if you have any problems”). The safety of the drug is, in a very real sense, co-created during the clinical encounter.

5.3 Re-interpreting the Evidence: Nocebo as a Confounding Factor

The nocebo effect provides a robust and scientifically plausible alternative explanation for many of the anecdotal reports and conflicting observational studies that have documented negative outcomes after a switch to a generic drug.60 When a patient expects a generic to be less effective or to cause more side effects, they are more likely to experience precisely those outcomes. This can manifest in two critical ways:

- Symptom Misattribution: Patients are more likely to misattribute pre-existing or unrelated somatic symptoms to the new generic medication simply because their attention has been primed to search for adverse effects.79

- Reduced Medication Adherence: The belief that a generic is inferior or the experience of nocebo-induced side effects can cause a patient to become non-adherent—skipping doses or discontinuing the therapy altogether.79 This non-adherence then leads to a genuine therapeutic failure (e.g., elevated blood pressure, a breakthrough seizure), which the patient and sometimes the clinician wrongly blame on the quality of the generic drug, rather than on the patient’s behavior, which was itself driven by negative expectations.

This creates a vicious cycle where the perception of inferiority generates behaviors that produce real negative outcomes, which in turn reinforce the original perception. The profound disconnect between the strong scientific evidence for equivalence (Section 4) and the widespread public and professional doubt (Section 5.1) is therefore not a benign academic debate; it is a major, unaddressed public health problem. The nocebo effect, fueled by this gap, causes real harm in the form of unnecessary side effects, reduced medication adherence, and avoidable therapeutic failures, which ultimately increase healthcare costs and lead to poorer patient outcomes. This suggests that the most significant “safety issue” associated with generic drugs may not be the drugs themselves, but the pervasive misinformation and lack of confidence surrounding them. The problem is as much one of communication, education, and psychology as it is of pharmacology.

Section 6: An Analysis of Permissible Differences: Excipients, Appearance, and Labeling

While generic and brand-name drugs are required to be identical in their therapeutic action, the regulatory frameworks in both the U.S. and Europe permit certain differences. These tangible distinctions in inactive ingredients, physical appearance, and sometimes labeling, while typically not clinically significant, are often the focal point of patient and provider concern. Understanding what these differences are, why they are permitted, and what their real-world implications are is crucial for bridging the gap between scientific equivalence and public perception.

6.1 Inactive Ingredients (Excipients): Function and Safety

The most significant compositional difference between a generic and a brand-name drug lies in their inactive ingredients, also known as excipients. These are the substances other than the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) that are included in a formulation to serve various functions, such as acting as fillers or binders, adding color or flavor, or aiding in the manufacturing process.9 While the API must be identical, the excipients used in a generic drug can, and often do, differ from those in the brand-name product.27

This difference is permitted only under strict regulatory control. A generic drug manufacturer must provide the FDA with comprehensive evidence demonstrating that all excipients used in its product are safe and have been previously approved for human use.26 Critically, the manufacturer must also show that any differences in excipients between its product and the brand-name drug have no effect on the overall function, safety, or effectiveness of the medication, particularly its bioavailability.27 The FDA rigorously reviews this evidence as a core component of the ANDA approval process.26

For the vast majority of patients, these differences in inactive ingredients are clinically irrelevant. However, it is important to acknowledge the rare but real possibility that a patient may have a specific allergy or intolerance to an excipient, such as lactose, gluten, or certain dyes.40 In such cases, a difference in excipients between two formulations could be clinically meaningful for that specific individual. This represents a valid, though uncommon, medical reason for a patient to require a particular brand or a specific generic formulation that does not contain the problematic ingredient.

6.2 Physical Appearance: The Mandate to Be Different

One of the most noticeable differences between brand and generic drugs is their physical appearance. A generic pill may have a different color, size, or shape than its brand-name counterpart. This distinction is not an indicator of inferior quality; rather, in the United States, it is often a legal requirement. Trademark laws generally prevent a generic drug manufacturer from making its product look exactly like the brand-name drug, as the brand’s appearance (its “trade dress”) is considered part of its proprietary identity.54

This legally mandated difference is a primary source of the evidence-perception gap. The tangible, visible distinction in a pill’s appearance provides concrete “proof” for a skeptical patient or clinician that the two drugs are “not the same.” This physical evidence, while therapeutically irrelevant in almost all cases, directly fuels the psychological mechanisms of doubt and the nocebo effect discussed in the previous section. This creates a paradox where a legal principle (trademark law) designed to protect a brand’s commercial identity inadvertently undermines public confidence in the scientific principle of therapeutic equivalence.

The concept of the “authorized generic” further complicates and ultimately undermines the entire brand-versus-generic dichotomy. An authorized generic is a medication that is marketed as a generic but is, in fact, the exact same product as the brand-name drug—identical in both active and inactive ingredients, as well as in physical appearance.43 These products are marketed under a different name, often by the brand-name manufacturer itself or with its permission, typically as a strategy to compete on price after patent expiry.43 The existence of authorized generics is the ultimate proof that the “brand” versus “generic” label is frequently a matter of marketing and economics, not of medicine. A patient could be taking the physically and chemically identical product one month under a brand name and the next under a generic name without any change in the pill itself. This fact is a powerful, if underutilized, educational tool that can effectively dismantle the perception of inferiority and build confidence in the safety and reliability of generic substitution.

6.3 Labeling Differences: The “Skinny Label”

As a general rule, the drug information label, or package insert, for a generic medicine must be the same as the FDA-approved label for the brand-name drug.26 This ensures that prescribers and patients have consistent information regarding the drug’s use, dosage, warnings, and side effects.

However, there is a significant exception to this rule that is driven by patent law. A brand-name drug may be approved for multiple different uses, or indications. If one or more of these indications are still protected by patents or other market exclusivities at the time a generic is ready to launch, the generic manufacturer is permitted to use a “skinny label”.9 This is a label that “carves out,” or omits, the information related to the still-protected uses, allowing the generic to be approved and marketed only for those indications whose patents have expired.26 This is a critical legal and commercial strategy that enables earlier generic competition and access. While necessary, this practice can sometimes cause confusion for clinicians and pharmacists who may not be aware of why the generic label differs from the brand’s label, potentially leading to questions about the generic’s approved uses.

Section 7: Synthesis, Conclusions, and Recommendations

The question of whether generic drugs are less safe than their branded equivalents is a matter of significant public health importance, influencing prescribing habits, patient adherence, and healthcare costs. A comprehensive analysis of the regulatory frameworks, scientific principles, clinical evidence, and perceptual factors yields a clear, albeit nuanced, conclusion. The overwhelming body of evidence demonstrates that approved generic drugs are not less safe than their brand-name counterparts. The persistent skepticism to the contrary is largely fueled by a misunderstanding of the science, powerful psychological factors, and legitimate but often misattributed concerns about the global pharmaceutical supply chain.

7.1 Synthesis of Findings: A Multi-Factorial Conclusion

The core conclusion of this exhaustive review is that FDA-approved generic drugs are therapeutically equivalent to, and therefore just as safe and effective as, their brand-name counterparts. This conclusion is supported by several converging lines of evidence:

- Robust Regulatory Foundation: The regulatory systems in the United States and the European Union are built upon a rigorous and internationally accepted scientific foundation designed to ensure therapeutic equivalence. The Hatch-Waxman Act created a deliberate framework that balances innovation with access, and the ANDA process requires generic manufacturers to meet exacting standards for pharmaceutical equivalence, bioequivalence, and manufacturing quality under cGMP.

- Overwhelming Clinical Evidence: The highest-quality clinical evidence, including large-scale meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials in critical therapeutic areas, consistently confirms that generic drugs produce the same clinical outcomes and safety profiles as brand-name drugs. Even in the case of controversial Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs, rigorous studies support the safety of substitution, with the caveat that prudent clinical monitoring during a switch is a wise standard of care.

- The Power of Perception: The persistent belief that generics are less safe is not supported by this body of evidence. Instead, it is fueled by a confluence of non-pharmacological factors. A widespread misunderstanding of the stringent statistical standards for bioequivalence creates an opening for doubt. This doubt is amplified by the powerful influence of the nocebo effect, which is triggered by legally mandated differences in pill appearance and can be magnified by the negative expectations of both patients and providers. This can lead to real adverse events and non-adherence, which are then wrongly blamed on the generic drug’s quality.

- Systemic, Not Generic-Specific, Risks: Legitimate concerns do exist, but they are systemic to the modern pharmaceutical industry, not specific to generics. The challenges of regulatory oversight in a vast, globalized manufacturing supply chain can lead to quality control lapses, such as contamination, that can affect both brand and generic drugs. The critical safety determinant is the quality of a specific manufacturer, not its brand or generic status. Similarly, the rare but real potential for an allergic reaction to an inactive ingredient (excipient) is a formulation-specific issue, not a generic-specific one.

In summary, the safety and efficacy of a generic drug’s design are assured by the rigorous science of the ANDA process. Its ongoing safety is assured by the same cGMP and post-market surveillance systems that apply to all drugs. The perception of inferiority is a separate, psychologically driven phenomenon that, paradoxically, may represent the greatest “safety risk” associated with generics by fostering non-adherence and nocebo-induced harm.

7.2 Recommendations for Stakeholders

Addressing the gap between the scientific reality of generic drug safety and public perception requires a concerted effort from all participants in the healthcare system.

For Clinicians and Pharmacists:

- Adopt Proactive, Positive Communication: The clinical encounter is a critical intervention point. When prescribing or dispensing a generic, frame the medication with confidence. Use clear, positive language such as, “I am prescribing/dispensing the generic version of this medicine. It has the same active ingredient and works in the exact same way as the brand-name drug to treat your condition.” This can actively build patient trust and mitigate the nocebo effect.

- Provide Targeted Patient Education: Briefly explain that the FDA has the same high standards for quality, safety, and effectiveness for all approved medicines, brand and generic alike. A useful analogy is that the small, acceptable variability between a generic and a brand is similar to the variability between two different batches of the same brand-name drug.

- Acknowledge and Explain Differences: Preempt patient concerns by acknowledging that the pill may look different. Explain that this is a result of trademark laws and does not reflect a difference in the medicine’s action. When dispensing, it is good practice to inquire about known allergies to common excipients like lactose or specific dyes.

- Maintain Vigilance with NTI Drugs: For NTI drugs, continue the established best practice of enhanced clinical monitoring (e.g., checking INR for warfarin, TSH for levothyroxine, or seizure frequency for AEDs) in the period immediately following any switch in formulation. Frame this not as a concern about the generic’s quality, but as a standard of good clinical care to account for potential minor variations in an individual patient’s response.

For Patients:

- Engage and Ask Questions: If a refilled prescription looks different from what you are used to, do not hesitate to ask your pharmacist to confirm that it is the correct medication and dose. Understanding why it looks different can build confidence.

- Communicate Openly with Providers: Inform your doctor and pharmacist of any known allergies or sensitivities to medications or other substances. If you experience new or worsening symptoms after switching to a new formulation, report them to your provider. It is important to work together to determine the cause, which may be unrelated to the medication or related to expectancy.

- Trust the Regulatory Process: Understand that the United States and other developed nations have rigorous, science-based regulatory systems in place to ensure that all approved medicines on the market are safe and effective. The lower cost of a generic drug is a result of a more efficient approval pathway, not inferior quality.

For Policymakers and Regulators:

- Strengthen Global Manufacturing Oversight: Continue to invest in and expand the FDA’s capacity for timely, frequent, and unannounced inspections of foreign manufacturing facilities. Ensuring the integrity of the global supply chain is paramount for the safety of all drugs, both brand and generic.

- Fund Public and Professional Education Campaigns: The gap between evidence and perception is a significant public health issue that warrants a public health response. Develop and fund evidence-based educational campaigns aimed at both consumers and healthcare professionals. These campaigns should clearly explain the science of bioequivalence, the rigor of the generic approval process, and the nature of the nocebo effect, with the specific goal of countering misinformation and improving medication adherence.

- Enhance Transparency: Promote greater public awareness of industry practices, such as the marketing of “authorized generics.” Highlighting that brand-name companies themselves are major participants in the generic market can be a powerful tool to demystify the brand-versus-generic divide and build public trust in the equivalence of these essential medicines.

Works cited

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- Pharmaceutical Innovation – Incentives, Competition, and Cost-Benefit Analysis in International Perspective – DukeSpace, accessed August 4, 2025, https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/bitstreams/8b9cc750-0755-490e-835a-b998a0015164/download

- cdn.aglty.io, accessed August 4, 2025, https://cdn.aglty.io/phrma/global/blog/import/pdfs/Fact-Sheet_What-is-Hatch-Waxman_June-2018.pdf

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Abbreviated New Drug Application – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbreviated_New_Drug_Application

- Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDA) Explained: A Quick-Guide – The FDA Group, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/abbreviated-new-drug-applications-anda

- Navigating the ANDA and FDA Approval Processes – bioaccess, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.bioaccessla.com/blog/navigating-the-anda-and-fda-approval-processes

- The Definitive Guide to Generic Drug Approval in the U.S.: From ANDA to Market Dominance – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/obtaining-generic-drug-approval-in-the-united-states/

- Hatch-Waxman Turns 30: Do We Need a Re-Designed Approach for the Modern Era? – Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository, accessed August 4, 2025, https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/5929/Kesselheim_2.pdf

- Generic Drugs – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/buying-using-medicine-safely/generic-drugs

- Report: 2023 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report, accessed August 4, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2023-savings-report-2/

- Report: 2022 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report, accessed August 4, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2022-savings-report/

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 4, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- The Impact of Patent Cliff on the Pharmaceutical Industry – Bailey Walsh, accessed August 4, 2025, https://bailey-walsh.com/news/patent-cliff-impact-on-pharmaceutical-industry/

- Strategies That Delay Market Entry of Generic Drugs – Commonwealth Fund, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/strategies-delay-market-entry-generic-drugs

- Patent Cliff: What It Means, How It Works – Investopedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/patent-cliff.asp

- Patent cliff – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_cliff

- The End of Exclusivity: Navigating the Drug Patent Cliff for Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- 5 Pharma Powerhouses Facing Massive Patent Cliffs—And What They’re Doing About It, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/business/5-pharma-powerhouses-facing-massive-patent-cliffs-and-what-theyre-doing-about-it

- The Generic Drug Supply Chain | Association for Accessible Medicines, accessed August 4, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/generic-drug-supply-chain/

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed August 4, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- Generic Competition and Drug Prices | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/generic-competition-and-drug-prices

- How to Ensure Your Generic Drug Meets FDA Standards: A …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-ensure-your-generic-drug-meets-fda-standards/

- Ensuring the Safety of FDA-Approved Generic Drugs, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/ensuring-safety-fda-approved-generic-drugs

- What Is the Approval Process for Generic Drugs? | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/what-approval-process-generic-drugs

- Generic Drugs: Questions & Answers – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/frequently-asked-questions-popular-topics/generic-drugs-questions-answers

- Generic and hybrid applications | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/generic-hybrid-medicines/generic-hybrid-applications

- Generic and hybrid medicines – EMA – European Union, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/generic-hybrid-medicines

- EMA and International Engagement for Generics Development – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/177936/download

- Comparing FDA and EMA Decisions for Market Authorization of Generic Drug Applications covering 2017–2020, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/156611/download

- Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) Regulations | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/current-good-manufacturing-practice-cgmp-regulations

- Myths, questions, facts about generic drugs in the EU – GaBIJ, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/myths-questions-facts-about-generic-drugs-in-the-eu.html

- Orange Book Preface – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/orange-book-preface

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations 40th Edition (Orange Book) – Maryland General Assembly, accessed August 4, 2025, https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/cmte_testimony/2020/hgo/4171_02252020_101316-408.pdf

- Bioequivalence – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/abbreviated-new-animal-drug-applications/bioequivalence

- Definition of Bioavailability and Bioequivalence – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/110310/download

- Bioequivalence: tried and tested – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3721767/

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- Similarities and Differences Between Brand Name and Generic Drugs | CDA-AMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.cda-amc.ca/similarities-and-differences-between-brand-name-and-generic-drugs

- Generic vs. Brand-Name Drugs: What’s the Difference? – Humana, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.humana.com/pharmacy/medication-information/difference-between-generic-and-brand-drug

- A review of the differences and similarities between generic drugs and their originator counterparts, including economic benefits associated with usage of generic medicines, using Ireland as a case study – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3579676/

- Utilizing Generic Drug Awareness to Improve Patient Outcomes with Dr. Sarah Ibrahim | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/utilizing-generic-drug-awareness-improve-patient-outcomes-dr-sarah-ibrahim

- Insights Into Effective Generic Substitution – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/insights-into-effective-generic-substitution

- Generics-at-a-Glance with Dr. Sarah Ibrahim – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/generics-glance-dr-sarah-ibrahim

- Office of Generic Drugs 2022 Annual Report – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/office-generic-drugs-2022-annual-report

- “FDA Ensures Equivalence of Generic Drugs”, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.forwardhealth.wi.gov/wiportal/content/provider/pac/pdf/FDAEnsuresEquivalence.pdf.spage

- Generic Drug Facts | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/generic-drug-facts

- Is the Quality of Generic Drugs Cause for Concern? – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10391121/

- Domestic pharma industry may face setback if US imposes tariffs, accessed August 4, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/domestic-pharma-industry-may-face-setback-if-us-imposes-tariffs/articleshow/123002989.cms

- Trump tariffs to push up US drug prices, won’t change India’s pharma growth playbook: Pharmexcil, accessed August 4, 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/trade/exports/insights/trump-tariffs-to-push-up-us-drug-prices-wont-change-indias-pharma-growth-playbook-pharmexcil/articleshow/123041531.cms

- The Economics of Generic Drug Pricing Strategies: A Comprehensive Analysis – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-economics-of-generic-drug-pricing-strategies-a-comprehensive-analysis/

- Pharmaceutical Quality Resources – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources

- Generic vs Brand Drugs: Your FAQs Answered, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/article/generic_drugs.html

- Branded vs. Generic: Know the Difference – Pfizer, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pfizer.com/products/how-drugs-are-made/branded-versus-generics

- Generic versus brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular diseases – PubMed, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26620809/

- Comparative effectiveness of branded vs. generic versions of antihypertensive, lipid-lowering and hypoglycemic substances: a population-wide cohort study, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7136234/

- Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis – PubMed, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19050195/

- No difference in efficacy between generic antiepileptic drugs – The Pharmaceutical Journal, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/no-difference-in-efficacy-between-generic-antiepileptic-drugs

- Safety and efficacy of generic drugs with respect to brand formulation – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3853662/

- Comparative Effectiveness of Persistent Use of a Name-Brand Levothyroxine (Synthroid®) vs. Persistent Use of Generic Levothyroxine on TSH Goal Achievement: A Retrospective Study Among Patients with Hypothyroidism in a Managed Care Setting – ResearchGate, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357035210_Comparative_Effectiveness_of_Persistent_Use_of_a_Name-Brand_Levothyroxine_SynthroidR_vs_Persistent_Use_of_Generic_Levothyroxine_on_TSH_Goal_Achievement_A_Retrospective_Study_Among_Patients_with_Hypoth

- (PDF) Generic Substitution Issues: Brand-generic Substitution, Generic-generic Substitution, and Generic Substitution of Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI)/Critical Dose Drugs – ResearchGate, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51697241_Generic_Substitution_Issues_Brand-generic_Substitution_Generic-generic_Substitution_and_Generic_Substitution_of_Narrow_Therapeutic_Index_NTICritical_Dose_Drugs

- FDA Q&A: Generic Versions of Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs National Survey of Pharmacists’ Substitution Beliefs and Practices – DIA Global Forum, accessed August 4, 2025, https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue/july-2019/fda-qa-generic-versions-of-narrow-therapeutic-index-drugs-national-survey-of-pharmacists-substitution-beliefs-and-practices/

- Understanding generic narrow therapeutic index drugs. – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/162779/download

- Switching generic antiepileptic drug manufacturer not linked to seizures: A case-crossover study – PMC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5089522/

- Barriers to generic antiseizure medication use: Results of a global survey by the International League Against Epilepsy Generic Substitution Task Force, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9159248/

- Equivalence Among Antiepileptic Drug Generic and Brand Products in People With Epilepsy: Chronic-Dose 4-Period Replicate Design | ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed August 4, 2025, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01713777

- Brand name versus generic warfarin: a systematic review of the literature – PubMed, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21449627/

- Brand Name versus Generic Warfarin: A Systematic Review of the Literature – ResearchGate, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/50935251_Brand_Name_versus_Generic_Warfarin_A_Systematic_Review_of_the_Literature

- Are Brand-Name and Generic Warfarin Interchangeable? Multiple N-of-1 Randomized, Crossover Trials – McMaster Experts, accessed August 4, 2025, https://experts.mcmaster.ca/display/publication440187

- Is switching anticoagulant brands safe – Coumadin and Marevan?, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.amsj.org/archives/4762

- Brand and Generic Medication Explained – American Thyroid Association, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.thyroid.org/brand-generic-medication/

- Real-world Evidence from a Narrow Therapeutic Index Product (Levothyroxine) Reflects the Therapeutic Equivalence of Generic Drug Products | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/spotlight-cder-science/real-world-evidence-narrow-therapeutic-index-product-levothyroxine-reflects-therapeutic-equivalence