The pharmaceutical industry operates at the nexus of groundbreaking scientific discovery, immense financial investment, and critical public health needs. At the heart of this intricate ecosystem lies the drug patent system, a legal framework designed to incentivize innovation by granting temporary monopolies to pioneering companies. Yet, this very mechanism, while fostering advancements, has become a sophisticated arena where innovator companies deploy a formidable array of tactics not just to protect their discoveries, but to actively block competitors and extend their market exclusivity. This report delves into these intricate strategies, dissecting their mechanics, analyzing their profound economic and social consequences, and exploring the evolving landscape of counter-strategies and regulatory oversight. For business professionals navigating this high-stakes environment, understanding these dynamics is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical imperative for competitive advantage and strategic foresight.

The Bedrock of Biopharmaceutical Innovation: Understanding Drug Patents

Pharmaceutical patents form the bedrock of intellectual property protection in the drug industry, safeguarding the innovations that drive medical advancements. These patents are distinct in their subject matter but adhere to universal patentability standards, playing a crucial role in a drug’s market journey.

Defining Pharmaceutical Patents: A Foundation of Exclusivity

Pharmaceutical patents are a form of intellectual property that grants inventors, typically pharmaceutical companies, exclusive rights to sell a newly developed drug for a specified period, generally 20 years from the date of patent application filing.1 This temporary monopoly prevents other entities from manufacturing, using, selling, or importing the patented invention without explicit permission, thereby providing a powerful incentive for continued Research and Development (R&D) and fostering groundbreaking scientific discoveries.1 In the United States, these patents are granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

The very nature of pharmaceutical patents presents a fundamental tension. While they are explicitly designed to incentivize the colossal investments required for R&D—often billions of dollars over many years—the exclusivity they confer inherently creates a monopolistic environment. This allows the patent holder to set drug prices without direct competition, enabling them to recoup their substantial investment and generate profits.2 However, from a broader societal perspective, this temporary monopoly can stifle competition and hinder societal progress by limiting access to potentially life-saving medications.4 This system is, in essence, a deliberate competition barrier artificially established to compensate for the high costs and lengthy development cycles of innovative drugs.4

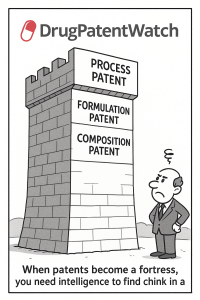

Types of Drug Patents: A Multi-Layered Shield

Pharmaceutical companies employ a diverse array of patent types to secure comprehensive protection for their innovations, extending beyond the core active ingredient to encompass various aspects of a drug’s development and application. This multi-layered approach is a strategic imperative designed to create a robust defensive perimeter around a drug.

- Composition of Matter Patents: These are widely considered the most valuable and sought-after patents in the pharmaceutical industry. They protect the specific chemical compound that constitutes the active ingredient of a drug, offering the broadest competitive advantage by preventing others from producing chemically identical versions.1

- Method of Use Patents: These patents protect a specific, novel way of utilizing an already known compound, drug, or product. This can include newly discovered therapeutic uses for existing drugs, allowing companies to expand the market for their innovations.1

- Formulation Patents: These safeguard the specific composition of a drug, including its inactive ingredients, unique combinations, delivery mechanisms (e.g., tablets, injections, extended-release systems), or specialized packaging that optimizes drug performance.1

- Process Patents: These cover the methods and processes used to manufacture the drug. They are essential for protecting proprietary manufacturing techniques that can be critical to the drug’s efficacy and safety, thereby creating additional barriers to entry for competitors.5

- Design Patents: Beyond the chemical or functional aspects, these patents protect the ornamental design of packaging and delivery systems, such as inhalers or injectors, adding another layer of intellectual property protection.10

- Tertiary Patents: This category often involves using medical devices paired with an active ingredient that may be off-patent to prolong market exclusivity. These patents demonstrate the creative lengths companies go to maintain market control.7

The existence and strategic deployment of these diverse patent types reveal that a pharmaceutical company’s intellectual property strategy extends far beyond merely protecting the initial chemical discovery. Instead, it represents a deliberate, multi-faceted approach to construct a “dense and overlapping network of protection”—often referred to as a “patent thicket”—around a single drug.6 This comprehensive layering aims to maximize and extend market control, transforming patent protection into a dynamic tool for competitive dominance rather than just a static safeguard for invention.

Patentability Criteria: The Gatekeepers of Innovation

For a patent to be granted by the USPTO, an invention must satisfy rigorous criteria, ensuring that only truly novel and non-obvious advancements receive monopolistic protection. These criteria act as gatekeepers, theoretically preventing the patenting of trivial modifications.

- Novelty: The invention must not have been publicly known or used by others before the patent applicant invented it. This ensures that the patent protects genuinely new creations.1

- Non-obviousness: The invention must not be an obvious development to a person skilled in the relevant field. This criterion prevents the patenting of incremental improvements that would naturally occur to an expert.1

- Usefulness (Industrial Applicability): The invention must possess a practical utility or be capable of industrial application, demonstrating a tangible benefit or function. It must solve a real-world problem or provide a tangible advantage.1

Patent Term vs. Effective Market Exclusivity: The Shrinking Window

The statutory term for a new patent is uniformly set at 20 years from the date the patent application was filed.1 This 20-year minimum standard is a global mandate, established for all World Trade Organization (WTO) member nations under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). However, a critical distinction exists between this statutory patent term and the “effective patent life”—the actual period during which a drug enjoys market exclusivity free from generic competition. This effective period is consistently and significantly shorter than the nominal 20 years.

A substantial portion of the 20-year statutory term, often 10 to 15 years, is consumed by the extensive preclinical and clinical trials, followed by the rigorous regulatory review process that must be completed before a drug can be legally marketed.1 Consequently, the average effective exclusivity period from a drug’s market launch until generic alternatives become available is typically cited as ranging from 7 to 10 years.1

This significant reduction in effective market life creates immense pressure on innovator companies. It means that despite the 20-year statutory term, the window for recouping billions in R&D investment is compressed. This financial imperative directly incentivizes companies to adopt aggressive “lifecycle management” strategies, including evergreening and the creation of patent thickets.2 The looming threat of the “patent cliff,” where multiple blockbuster drugs are set to lose exclusivity, threatens over $230 billion in revenue in the U.S. market alone over the next five years.6 This phenomenon transforms patent strategy from a mere legal compliance function into a core, proactive business imperative for long-term growth and revenue generation. The goal shifts from simply obtaining a patent to strategically extending its commercial viability for as long as possible.

Patents vs. Regulatory Exclusivities: Distinct but Complementary Protections

While patents and regulatory exclusivities both contribute to market protection, they are distinct legal and regulatory instruments with different origins, timing, scope, and bases.1 Understanding this differentiation is crucial for comprehending the multifaceted nature of pharmaceutical market protection.

- Patents: Granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), patents represent a legal property right. They can be issued or expire at any point during a drug’s development lifecycle, irrespective of its regulatory approval status. The scope of patent protection is broad, encompassing various claims such as the drug substance (active ingredient), the drug product (its formulation), and specific methods of using the drug. Patents are awarded based on rigorous criteria of novelty, non-obviousness, and usefulness of the invention.1 Their primary purpose is to incentivize R&D by granting a temporary monopoly, thereby allowing the inventor to recoup their investment.

- Regulatory Exclusivities: These are exclusive marketing rights conferred by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These rights are granted only upon approval of a drug product if statutory requirements are met.1 Regulatory exclusivities vary in term depending on the type:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: Provides 5 years of exclusivity for drugs containing a new active ingredient.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): Grants 7 years of exclusivity for drugs developed to treat “orphan diseases,” defined as conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 people annually in the U.S..1 This aims to incentivize R&D for smaller patient populations.2

- Pediatric Exclusivity: Adds 6 months to existing patents or exclusivities if pediatric studies are conducted, encouraging research into drug use in children.

- 180-Day Generic Exclusivity: A significant incentive awarded to the first generic company that successfully challenges a brand-name drug’s patent by filing a Paragraph IV certification and winning approval.1

- Biologics Exclusivity (BPCIA): Provides 12 years of market exclusivity for reference biological products, with an additional 1 year for the first interchangeable biosimilar.1

Concerns about exclusivity abuses and potential reform usually focus on patents because the patent exclusivity term is longer and can be lengthened through secondary patents, whereas regulatory exclusivity grants are provided only to new drug applicants and are generally fixed in duration.3 This distinction highlights why patents are the primary battleground for competitive blocking tactics.

The Innovator’s Arsenal: Tactics to Prolong Monopoly and Deter Entry

Innovator pharmaceutical companies, driven by the imperative to maximize returns on their substantial R&D investments, have developed a sophisticated arsenal of tactics to prolong their market monopolies and deter generic or biosimilar competition. These strategies often push the boundaries of intellectual property law, leading to intense legal and public scrutiny.

Evergreening Strategies: Extending the Patent Horizon

Evergreening is a widely debated strategy by which pharmaceutical companies extend the lifetime of their patents that are about to expire, often by obtaining new patents for minor modifications, improvements, or new applications of existing products.20 Robin Feldman, a leading researcher in intellectual property and patents, defines evergreening as “artificially extending the life of a patent or other exclusivity by obtaining additional protections to extend the monopoly period”.20

Common evergreening tactics include:

- New Formulations, Dosage Forms, and Delivery Systems: This involves modifying a drug’s dosage form (e.g., converting tablets to liquids or capsules to extended-release versions), altering its combination with other ingredients, changing its route of administration (e.g., an oral version of a drug previously given by injection), or modifying its release characteristics.1 A notable example is Purdue Pharma’s OxyContin, which had its original patent extended through an extended-release formulation.23 Similarly, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) obtained a patent on chewable and dispersible tablets for lamotrigine, extending its protection for 12 years beyond the original patent term.24

- New Indications and Combination Drug Patents: This strategy involves patenting newly discovered therapeutic uses for existing drugs (e.g., developing a previously patented compound for use in a different disease) or creating a new product by combining an existing active ingredient with one or more other active ingredients.1 For instance, Pfizer’s Viagra, beyond its compound patent, secured method-of-use patents for erectile dysfunction, stretching its exclusivity.8

The practice of evergreening is a heated, controversial topic. Supporters, often from within the pharmaceutical industry, argue that it encourages continuous innovation and allows companies to recoup their immense R&D costs, leading to enhanced product efficacy and safety.21 However, opponents, including consumer groups and healthcare advocates, contend that it stifles fair competition, elevates drug prices, and restricts access to affordable treatments.21 The line between genuine improvement and an anticompetitive strategy is often blurred.20

The ethical and economic trade-off of “incremental innovation” in evergreening is a significant point of contention. While evergreening involves minor modifications to existing drugs to extend patent life, critics argue that these changes often lack “significant therapeutic advantage” 25 or “clinically meaningful” benefits over the original drug.26 Instead, these modifications primarily serve a “company’s economic advantage” 25 and are “far less expensive for the companies to develop than discovering a new drug”.27 This suggests that the patent system, by rewarding even minor changes, incentivizes companies to invest in low-risk, high-return “tweaks” rather than truly novel, high-risk R&D aimed at addressing unmet medical needs.13 This dynamic raises a profound ethical question: does the current system truly optimize public health outcomes, or does it primarily serve corporate profit motives? Critics argue that it can lead to “unjust enrichment” for companies and a “double burden on consumers” who pay once through public funding of R&D and again through inflated prices protected by layered patents.22

Product Hopping: Shifting the Market Landscape

Product hopping, also known as product switching, is an anti-competitive practice where a patent, and consequent revenue stream, is extended by patenting a minor variation on the original product, thereby further delaying the entry of a generic onto the market.20 This strategy involves shifting a customer base from an older drug to a newer one with a longer remaining patent life.28

Product hopping can manifest in two primary forms:

- Hard Switches: This occurs when the older drug is actively pulled from the market and replaced with its newer counterpart.28 This tactic is generally viewed as more aggressive and is significantly more likely to be deemed anticompetitive by courts.28

- Soft Switches: In this scenario, the older drug remains for sale, but all marketing efforts are strategically shifted to the new drug, subtly encouraging patient and prescriber transitions.28

Case studies vividly illustrate the impact of product hopping:

- Namenda (memantine): In the landmark case of New York v. Actavis, Forest Laboratories, the manufacturer of the Alzheimer’s drug Namenda, attempted a hard switch. It announced plans to discontinue the immediate-release (IR) version of Namenda before its patent expired, aiming to transition patients to a new extended-release (XR) version with a later patent expiry. The court issued a preliminary injunction, compelling Forest to continue selling the older drug. The court found that the hard switch was anticompetitive because it eliminated consumer choice, effectively forcing patients onto the newer, patented version and preventing generic versions of the original formulation from gaining market traction.20

- Copaxone (glatiramer acetate): Product hopping involving this multiple sclerosis drug by Teva Pharmaceuticals led to a staggering cost to consumers, estimated at $4.3 to $6.5 billion over two and a half years before the new patent was ultimately invalidated by the courts.20 The introduction of a 40mg pre-filled syringe version of Copaxone, with a patent expiring in 2030, caused a two-year delay for generic entry, significantly impacting generic market share and revenue.30

- QVAR (asthma inhaler): Teva Pharmaceuticals also faced allegations of product hopping for its QVAR asthma inhaler. Plaintiffs alleged that Teva employed two product hops: first, by discontinuing the original QVAR in 2014 and replacing it with a new version that included a dose counter (following FDA guidance that did not apply to existing inhalers), and second, by discontinuing the original QVAR again in 2017 after receiving FDA approval for QVAR Redihaler, which dispensed the drug upon inhale. These actions were alleged to have hampered competition by discontinuing products nearing patent expiration and switching consumers to new products with purportedly insignificant changes.29

Product hopping represents a strategic maneuver that exploits regulatory gaps to achieve forced transitions. It is not simply about introducing an improved product; it is a calculated effort to circumvent state laws that facilitate generic substitution at the pharmacy counter.28 Generic companies rely heavily on these automatic substitution laws to “free ride” on the brand’s initial marketing efforts and quickly gain market share once their bioequivalent product is approved. By introducing a slightly modified, newly patented version and then withdrawing the old one (a hard switch), innovator companies effectively force patients and prescribers to switch to the new version. This action directly blocks generic entry for the original formulation and extends the innovator’s market dominance, highlighting how companies can strategically exploit regulatory frameworks designed to promote competition to achieve the opposite effect.

Patent Thickets: Weaving a Defensive Web

A patent thicket refers to a dense web of overlapping patents held by multiple entities, creating a complex environment for navigating intellectual property rights.33 In the pharmaceutical industry, companies may file numerous patents related to a single drug to extend their market exclusivity and delay the entry of generic competitors.6

The anatomy of a patent thicket involves layering protection through various patent types:

- Innovator companies construct a “multi-layered ‘web of protection'” 6 using a combination of primary patents (covering the active ingredient) and secondary patents (covering peripheral features such as dosage forms, manufacturing methods, or storage requirements).35 A striking statistic reveals that for top-selling drugs, 66% of patent applications are submitted

after FDA approval.35 This post-approval patenting is a key component of thicket formation. - AbbVie’s Humira stands as a prominent example, protected by over 250 patents, which significantly delayed biosimilar entry in the U.S. until 2023, despite the drug’s initial launch in 2002.33 This extensive patenting strategy allowed Humira to generate $47.5 million per day in revenue before biosimilars entered the market.35

- Merck’s Keytruda, another blockbuster drug, has sought 129 patents, including those for seemingly trivial changes like sterile packaging.35 Its extended monopoly is projected to cost Americans over $137 billion.35

- Amarin holds over 100 patents on fish oil, making it harder for generics to enter the market despite the supplement having been available for many years.34

The impact of patent thickets on generic entry and the litigation barriers they create are substantial:

- Thickets create significant barriers for new entrants due to the prohibitive cost and complexity of navigating through existing patents to ensure freedom to operate.33

- Challenging the numerous patents within a thicket can be extraordinarily expensive, with costs reaching “millions” per drug for generics.35 Litigation can also be protracted, as exemplified by the case of

Revlimid, where litigation blocked generics for 18 years despite the primary patents having expired.35 - As patent attorney Ha Kung Wong notes, “Thickets force biosimilar developers to navigate dozens of overlapping claims, delaying affordable alternatives by years”.35

The formation of patent thickets transforms litigation into a strategic deterrent, rather than merely a mechanism for dispute resolution. The primary function of a patent thicket is not necessarily to assert the inherent strength or groundbreaking nature of each individual patent. Instead, it is to create an overwhelming “litigation barrier”.35 The sheer volume and complexity of patents within a thicket make it economically unfeasible for generic and biosimilar companies to challenge every single one, regardless of the individual patent’s merit. This strategy effectively extends monopolies through the legal process itself, leveraging the burden of litigation to deter competition through attrition and financial strain, rather than through pure technological innovation.

Pay-for-Delay Agreements: The Antitrust Flashpoint

“Pay-for-delay” agreements, also known as reverse payment patent settlements, are a controversial type of agreement used to settle pharmaceutical patent infringement litigation.37 In these arrangements, the patent holder (innovator company) agrees to pay the alleged infringer (generic company) to halt its alleged infringing activity for a specified period and to cease disputing the validity of the patent.38 This is a reversal of the typical patent settlement, where the alleged infringer pays the patent holder.38

The mechanism of reverse payment settlements often arises from a peculiarity in U.S. regulatory law, specifically the Hatch-Waxman Act. This Act incentivizes generic companies to challenge brand-name patents by granting 180 days of market exclusivity to the first generic company that successfully challenges a patent and gains FDA approval.38 In settling litigation, both the innovator and generic companies can calculate the potential income or losses if the litigation were to continue versus if they reached a settlement. This often leads to a mutually beneficial cash payment from the innovator to the generic, where both parties benefit more than they would from continued litigation.38

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) views opposing pay-for-delay agreements as one of its top priorities, considering them anticompetitive practices that stifle competition from lower-cost generic medicines.37 The FTC estimates that these deals cost consumers and taxpayers a staggering $3.5 billion annually, accumulating to $35 billion over a decade in higher drug costs.37 Since 2001, the FTC has actively pursued numerous lawsuits to halt these agreements.37

The Supreme Court’s landmark 2013 decision in FTC v. Actavis, Inc., was pivotal. The Court ruled that reverse payment settlement agreements are not per se illegal but should be analyzed according to the “rule of reason” under antitrust law.38 This decision initially led to a substantial decrease in potential pay-for-delay deals in the year following the ruling.37 However, these settlements have evolved, becoming more complex and opaque. Recent analysis indicates that while direct cash payments might be less common, the underlying anti-competitive objective persists through “side business deals” and “restrictive supply arrangements” where the financial flow still goes from the brand to the generic.41

This evolution of pay-for-delay agreements highlights the dynamic and adaptive nature of anti-competitive tactics in the pharmaceutical industry. As regulators and courts close one loophole, companies devise new, more intricate methods to achieve the same goal of delaying generic competition. This necessitates continuous vigilance and adaptation in antitrust enforcement, as the “chess game” between industry and regulators constantly evolves.

Strategic Litigation and Regulatory Exploitation

Innovator companies employ various litigation and regulatory maneuvers to delay generic entry, leveraging the legal framework to their advantage, often transforming procedural safeguards into instruments of delay.

- The 30-Month Stay: A Powerful Delay Tactic: Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, if a brand-name company files a patent infringement lawsuit against a generic manufacturer who has submitted a Paragraph IV certification (asserting non-infringement or invalidity), it automatically triggers a 30-month stay on FDA approval of the generic product.42 This stay is a crucial part of the Hatch-Waxman process, designed to allow time for patent disputes to be resolved in court before a generic can launch.42 However, this mechanism is often strategically exploited. Innovator companies are incentivized to “file and litigate as many patents as possible, even low-quality ones, to delay generics and keep prices high”.44 The 30-month stay, in this context, becomes a guaranteed period of extended monopoly, regardless of the patent’s ultimate validity, effectively weaponizing a procedural safeguard for anti-competitive ends.

- Misuse of Citizen Petitions and Sample Withholding:

- Citizen Petitions: Brand-name manufacturers can file “citizen petitions” with the FDA, ostensibly to raise concerns about generic applications. While the FDA is legally required to prioritize and respond to these petitions, they are frequently filed by branded drug manufacturers (92% of all citizen petitions, according to the FDA) near the patent expiration date.20 This tactic effectively limits potential generic competition for an additional 150 days, serving as a regulatory delay mechanism.20

- Sample Withholding: Generic drug manufacturers require samples of the brand-name drug to conduct bioequivalence testing, a prerequisite for generic approval. Innovator companies have, at times, restricted access to these samples, creating a barrier to generic development. The CREATES Act, passed in December 2019, was designed to address these issues and facilitate sample access for generic manufacturers.20

The strategic exploitation of these procedural safeguards reveals a systemic vulnerability within the regulatory framework. Mechanisms ostensibly designed to ensure orderly market entry and address legitimate concerns are transformed into instruments of delay. The 30-month stay, in particular, can be leveraged to secure a guaranteed period of extended monopoly, independent of the patent’s true merit. This highlights how legal and regulatory processes can be manipulated to achieve anti-competitive outcomes, underscoring the constant need for vigilance and reform.

The Ripple Effect: Consequences of Patent Blocking Tactics

The strategic use of drug patents to block competitors has far-reaching consequences that extend beyond corporate balance sheets, profoundly impacting healthcare systems, patient access, and the very trajectory of pharmaceutical innovation.

Economic Burden: Inflated Drug Prices and Healthcare Costs

The most direct and widely felt consequence of patent blocking tactics is the significant economic burden imposed through inflated drug prices and escalating healthcare costs. The cost of prescription drugs has skyrocketed in recent years. Between 2011 and 2021, America’s annual spending on prescription drugs surged by 64% (adjusted for inflation), from $366 billion to $603 billion.46 Prescription drugs now account for a substantial 22% of health insurance premiums.46 Projections indicate that the total U.S. drug costs will continue to rise dramatically, reaching an estimated $917 billion by 2030, a 62% increase from 2020.46

These patent abuses are identified as a “key reason drugs are so expensive”.46 The financial impact on consumers and payers is staggering:

- For example, Revlimid, a top-selling drug, experienced a more than 300% price increase over 20 years, escalating from $6,000 to $24,000 per month.35

- Delayed generic entry through patent thickets and other tactics costs consumers and taxpayers billions annually. An estimated $167 billion was wasted on just three drugs (Humira, Keytruda, and Revlimid) due to delayed generic entry in the U.S. compared to the European Union.35

- “Pay-for-delay” agreements alone are estimated to cost American consumers $3.5 billion annually, accumulating to $35 billion over a decade.37

The lost savings from delayed generic and biosimilar entry represent a massive economic opportunity cost. Generic drugs are typically priced significantly lower than their brand-name counterparts, often 80-85% less.18 Generic competition has been a powerful force in cost reduction, saving the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $2.6 trillion over the last decade 46, and $313 billion in 2019 alone.47 However, the average market entry of a first generic is between 12 and 14 years, and a first biosimilar is a little over 18 years.49 This significant delay means that lower-cost competition often emerges

after a drug has already generated substantial revenue for the innovator, and sometimes even after new price controls, such as those under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), begin to apply.49

The economic consequence of these blocking tactics is not merely the high price of the branded drug, but the compounding cost of lost savings that would have accrued from earlier generic competition. Every month of delayed generic entry can cost consumers and payers millions in potential savings.47 This creates a continuous and escalating financial burden on individuals, insurance providers, and government healthcare programs, directly linking aggressive patent strategies to the broader affordability crisis in healthcare.

Social Impact: Patient Access and Health Disparities

Beyond the economic toll, drug patent blocking tactics have profound social consequences, directly impacting patient access to essential medications and exacerbating existing health disparities.

Due to the persistently high cost of drugs, a growing number of Americans struggle to afford necessary medicine. A concerning statistic reveals that one in ten Medicare beneficiaries did not fill a physician’s prescription because they could not afford it.46 This financial barrier can lead to medication non-adherence, resulting in suboptimal treatment outcomes and a decline in overall public health.50

The situation also raises significant ethical dilemmas. Critics argue that it is morally questionable for companies to profit extensively from life-saving or quality-of-life-maintaining medications, contending that health should be treated as a fundamental human right and essential drugs as public goods.50 The high prices enabled by extended patent monopolies can render crucial treatments inaccessible to many, especially in lower-income countries or for individuals without adequate insurance coverage.50 This creates a stark ethical conflict between a company’s profit motive and the broader societal goal of maximizing public health and well-being.50

Furthermore, the current patent system inadvertently skews research and development priorities. It incentivizes R&D efforts towards diseases affecting large populations in wealthy countries, where the potential for high prices and substantial profits is greatest.50 This leads to a disproportionate focus on “blockbuster” drugs, potentially neglecting treatments for less common diseases or conditions prevalent in lower-income populations, such as malaria, tuberculosis, and neglected tropical diseases.50 This “skew in research priorities exacerbates global health disparities” and leaves millions of the world’s most vulnerable populations without access to needed treatments.50

This phenomenon also contributes to what some term “Intellectual Property (IP) colonialism.” This refers to the criticism that the global patent system, largely shaped by wealthy nations, disproportionately benefits them at the expense of developing countries.50 This manifests in several ways: strong patent protections can hinder the transfer of pharmaceutical technologies to developing countries, fostering dependence on foreign manufacturers; companies sometimes patent drugs based on traditional or indigenous knowledge without proper compensation; and developed countries often push for stricter IP protections in trade agreements, which may limit developing nations’ access to affordable generic medicines.50

The high cost of drugs and the resulting patient rationing, coupled with the skewed R&D priorities, reveal a profound societal and ethical conflict. While patents are a market-driven mechanism for fostering innovation, their application in pharmaceuticals, particularly when extended through aggressive blocking tactics, creates a system where market profitability can override fundamental public health needs. This leads to a problem of “missing” drugs in critical areas 53 and exacerbates global health disparities, challenging the very notion of universal access to health technologies as a fundamental human right.

Innovation Distortion: Shifting R&D Priorities

While the patent system is designed to reward and stimulate R&D, the aggressive use of tactics like patent thickets and evergreening can paradoxically distort innovation, diverting resources and stifling the development of truly novel therapies.

- Focus on Incremental Changes Over Novel Therapies: Evergreening strategies, which involve patenting minor modifications to existing drugs, have become pervasive. Data indicates that 78% of new patents protect existing drugs rather than introducing novel therapies.35 This means that a significant portion of R&D resources is diverted from discovering new drugs to patenting minor changes to existing ones. For instance, Merck spent years patenting Keytruda’s subcutaneous injection method instead of developing entirely new drugs.35 This allocation of resources suggests that the current system often rewards “legal maneuvering far more than scientific breakthroughs”.35 The incentive structure makes it “far more profitable to extend market monopolies for existing medicines, and develop variants of these, than it is to undertake riskier research to develop totally new medicines”.13

- Impact on Biotech Startups and Comprehensive Research: The proliferation of secondary patents, forming “patent thickets,” increases the cost and complexity of genuine R&D efforts, particularly for smaller biotechnology firms and startups.22 These smaller entities often face significantly higher litigation risks—approximately 25% higher in thicket-heavy fields like biologics.35 This can stifle innovation by deterring new entrants from pursuing research in crowded patent landscapes and slowing the overall pace of R&D across the industry.33 The sheer volume of patents makes it challenging for new companies to develop or commercialize products without infringing on existing rights, leading to increased costs and legal risks.33

The excessive exploitation of the patent system, therefore, leads to a distortion of innovation. Instead of driving truly transformative breakthroughs, it encourages incremental “me-too” drugs and defensive patenting. This ties up valuable R&D resources that could otherwise be directed towards high-risk, high-reward areas addressing significant unmet medical needs. This unintended consequence directly contradicts the stated purpose of the patent system to promote progress in science and the useful arts.

The Challenger’s Playbook: Strategies for Generic and Biosimilar Companies

In the face of aggressive patent blocking tactics by innovator companies, generic and biosimilar manufacturers have developed sophisticated strategies to challenge existing patents, navigate complex regulatory pathways, and ultimately bring more affordable medicines to market.

Leveraging the Hatch-Waxman Act: The Generic Pathway

The “Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984,” commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, fundamentally reshaped the pharmaceutical landscape. It established the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, allowing generic manufacturers to gain FDA approval by proving their product is bioequivalent to a brand-name drug, without repeating costly and time-consuming clinical trials to establish safety and efficacy.18 This legislative act transformed the generic drug industry, leading to a significant increase in generic prescriptions filled in the U.S., from a mere 19% in 1984 to over 90% today.54

- Paragraph IV Certifications: The Gateway to Market Entry: Generic manufacturers initiate patent challenges by filing an ANDA that includes a Paragraph IV (PIV) certification. This certification asserts that the brand-name patent is either invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed upon by the generic product.42 Filing a PIV certification automatically triggers patent litigation if the brand manufacturer responds within 45 days, effectively initiating a legal battle over market entry.43

- Securing 180-Day Exclusivity: The First-to-File Advantage: A critical incentive for generic companies is the 180-day market exclusivity granted to the first generic manufacturer that files an ANDA with a PIV certification and successfully prevails in the subsequent patent infringement lawsuit.12 This temporary monopoly allows the generic company to be the sole generic version on the market for six months, enabling it to capture significant market share and maximize profits before other generic competitors enter and erode prices.18 A classic example is Barr Laboratories’ PIV challenge against Eli Lilly’s Prozac (fluoxetine). After five years of litigation, Barr prevailed, and during its six-month monopoly on generic fluoxetine sales, it generated $360 million, nearly doubling its gross profit margin.43 This success significantly increased interest in PIV challenges across the generic industry.43

The 180-day exclusivity, while a powerful incentive, also presents a double-edged sword. While it rewards the first generic challenger, brand companies can launch “authorized generics” (AGs) during this 180-day period.20 AGs are chemically identical to the brand-name drug but are marketed without the brand name on the label.20 The presence of an AG during the 180-day exclusivity period significantly reduces the first-filer generic’s revenues, by an estimated 40-52%.58 This means that while the “first-to-file” advantage remains lucrative, it is not an unhindered monopoly. Generic companies must factor in potential AG competition into their market entry and pricing strategies, highlighting how brand companies can mitigate the impact of generic entry even within the established regulatory framework designed to foster competition.

Strategic Patent Analysis and Validity Challenges

Generic companies must conduct thorough patent analysis and due diligence to identify potential weaknesses or vulnerabilities in existing patents.18 This rigorous examination is the foundation of a successful patent challenge.

- Prior Art Research and Prosecution History Review: A key strategy involves meticulously searching for “prior art”—existing publications, patents, or other publicly available information that predates the invention and could demonstrate a lack of novelty or non-obviousness.10 Potent sources for prior art include drug labels with timestamps and scientific literature.56 Additionally, generic companies review the patent’s prosecution history (the record of its examination by the patent office) to look for inconsistencies or instances where claims were narrowed to gain approval, which can be leveraged to argue invalidity.56

- Targeting Secondary Patents and PTAB Proceedings: Secondary patents, such as those covering formulations or methods of use, are generally considered more vulnerable and easier to invalidate than primary patents protecting the active ingredient itself.56 Generic companies strategically target these peripheral patents. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) offers a faster, cheaper, and often more effective avenue for challenging patent validity through Inter Partes Review (IPR) proceedings. The PTAB has a notable success rate, invalidating claims in approximately 60-70% of cases.56 Best practices often involve combining IPR with traditional district court litigation to exert maximum pressure on patent holders.56

The precision of legal attack in patent challenges is a testament to the sophistication of generic strategies. Successful patent challenges are not broad, speculative attacks but highly targeted, data-driven legal endeavors. Generic companies invest heavily in forensic analysis of patent claims and their historical context to identify specific vulnerabilities. This transforms the inherent complexity of patent law into a strategic advantage for market entry, demonstrating that a deep understanding of the legal landscape is as crucial as scientific prowess in this competitive arena.

Navigating the Biologics Landscape: The BPCIA and the “Patent Dance”

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), enacted on March 23, 2010, as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, was modeled after the Hatch-Waxman Act. Its dual aim is to encourage competition and promote innovation in the complex field of biologics.19 The BPCIA creates an abbreviated pathway for biosimilars (lower-cost versions of previously approved biologic medicines) to gain FDA approval through the submission of an abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA).19

- The “Patent Dance” for Biosimilar Approval: A unique feature of the BPCIA is its outline of a pre-litigation framework colloquially known as the “patent dance.” This is a structured, stepwise information exchange designed to facilitate the early resolution of patent disputes between the reference product sponsor (RPS, the innovator) and the biosimilar applicant. The ultimate goal is to narrow the scope of potential litigation.19 This process involves the biosimilar applicant providing a detailed, claim-by-claim statement outlining the factual and legal bases for any assertions of invalidity, unenforceability, or non-infringement for each identified patent.60 The Supreme Court’s landmark 2017 decision in

Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc. fundamentally reshaped the biosimilar patent dance by confirming its optionality. This ruling provided biosimilar applicants with unprecedented strategic flexibility, clarifying that if a biosimilar applicant chooses not to provide its aBLA to the RPS, the patent owner’s only recourse is to initiate a patent infringement lawsuit, as the RPS cannot compel participation in the information exchange.60 - Purple Book Insights and Strategic Considerations: The FDA publishes the “Purple Book” (formally, Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluation). This crucial resource contains information on FDA-licensed reference products, biosimilars, and interchangeable biologics. It lists reference product exclusivities and evaluations of biosimilarity or interchangeability, and importantly, provides information about the patents that reference product sponsors consider potentially infringed by biosimilar or interchangeable products for which aBLAs have been filed.59 Unlike the Orange Book for small-molecule drugs, the Purple Book’s patent categories are not limited and may include patents claiming methods of manufacture, purification, starting materials, and expression vectors, reflecting the greater complexity of biologics.59

Despite being an “abbreviated pathway,” biosimilar market entry is far from straightforward; it is a highly formalized, legally intricate process. The “patent dance” is a complex choreography of legal maneuvers, not a simple regulatory checklist, where strategic decisions about information disclosure and litigation are paramount. This underscores the unique challenges and high stakes involved in bringing biosimilars to market, highlighting the continuous legal and regulatory navigation required.

Designing Around Patents: Fostering True Innovation

To avoid patent infringement and navigate the intellectual property landscape, generic and biosimilar companies often employ a strategic approach known as “designing around” existing patents. This involves creating non-infringing products or processes by finding alternative solutions that do not fall within the scope of the innovator’s patent claims.10 This approach fosters true innovation within the generic sector, pushing companies to develop novel methods and formulations.

- Creative Solutions to Avoid Infringement: Designing around patents requires a deep understanding of both the scientific principles of the drug and the precise language of patent claims. This can involve developing:

- Different crystalline structures (polymorphs) or enantiomers of the active ingredient, which may offer improved stability or bioavailability while avoiding infringement.7

- Unique formulations that alter the combination of ingredients, carriers, or delivery mechanisms.2

- Novel delivery methods, such as a nasal spray, transdermal patches, or extended-release systems, that achieve similar therapeutic effects through a different mechanism.2

- New manufacturing processes that produce the drug without infringing on existing process patents.7

- Case Studies of Successful Design-Arounds: While specific detailed examples are often proprietary due to their competitive nature, the practice is well-documented by intellectual property firms. Case studies illustrate how IP firms assist clients in:

- Identifying key patents to “design around” in complex processes, such as a barrel lubrication process for an injectable drug, enabling the client to finalize their manufacturing process in a cost-effective and non-infringing manner.61

- Analyzing existing patent landscapes and ongoing litigation to develop non-infringing product designs and filing strategies that minimize litigation risk and potentially allow for earlier market entry.61

- Identifying “white spaces” within the patent landscape—areas where novel and inventive products can be developed without infringing existing patents—thereby supporting the development of new and differentiated generic products.61

Designing around patents is not merely a defensive legal tactic; it is a powerful form of competitive innovation. It compels generic companies to invest in their own R&D and apply creative scientific and engineering solutions to find alternative, non-infringing pathways to market. This dynamic demonstrates how patent protection, while seemingly restrictive, can paradoxically stimulate new forms of innovation and product differentiation within the industry, fostering a more diverse and competitive market landscape.

Competitive Intelligence for Strategic Advantage

In the complex and high-stakes pharmaceutical patent landscape, competitive intelligence is paramount for both innovator and generic companies. The ability to anticipate market shifts, identify opportunities, and mitigate risks hinges on access to accurate, actionable, and timely data.

- Utilizing Platforms like DrugPatentWatch for Market Insights: Specialized platforms, such as DrugPatentWatch, serve as leading global biopharmaceutical business intelligence tools, providing “accurate, actionable, and timely intelligence to help make better decisions”.62 These platforms offer a comprehensive suite of functionalities critical for strategic planning:

- Patent Expiry Dates: Tracking when drug patents are set to expire is fundamental for identifying market entry opportunities.62

- Generic Entry Dates: Providing insights into when generic versions of drugs are expected to enter the market allows for precise timing of R&D and commercialization efforts.62

- Patent Litigation: Detailed information on legal disputes concerning drug patents, including case status and outcomes, helps assess risks and predict market dynamics.62

- Patent Term Extensions: Data on extensions granted to patent terms provides a clearer picture of actual market exclusivity periods.62

- Drug Sales Data: Access to information regarding drug sales performance allows companies to evaluate market potential and prioritize development efforts.62

- Generic Entry Opportunities: The platform assists in identifying lucrative low-competition generic drug markets—niches where only a few manufacturers produce a specific generic, leading to higher pricing power and better margins.18

- Confidential Royalty and Settlement Terms: Access to sensitive market data, including royalty and settlement terms, can inform negotiation strategies.62

- Automated Reports and Custom Dashboards: These tools enable continuous monitoring of biosimilar and 505(b)(2) activity, providing a dynamic view of the competitive landscape.62

In an industry defined by complex intellectual property and high financial stakes, access to and sophisticated analysis of granular data is transformative. It allows companies to transition from reactive responses to proactive strategic planning. By leveraging competitive intelligence platforms, businesses can anticipate competitor moves, identify market “white spaces,” and optimize their R&D and market entry investments with data-driven precision. This capability transforms raw data into a decisive competitive advantage, enabling companies to make informed decisions that shape their market position and profitability.

The Evolving Landscape: Regulatory Oversight and Policy Reforms

The dynamic interplay between innovator and generic pharmaceutical companies is constantly shaped by evolving regulatory oversight and ongoing legislative efforts. Governments and advocacy groups are increasingly scrutinizing patent blocking tactics, seeking to rebalance the system to ensure both innovation and affordable access to medicines.

Antitrust Enforcement in Pharmaceuticals: A Watchdog’s Role

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) share responsibility for enforcing antitrust laws in the U.S., including the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act. These laws aim to protect competition for the benefit of consumers, ensuring strong incentives for businesses to operate efficiently, keep prices down, and maintain high quality.40

- FTC and DOJ Actions Against Anti-Competitive Practices: The FTC has made opposing “pay-for-delay” agreements a top priority, filing numerous lawsuits and actively supporting legislation to end these deals.37 Beyond pay-for-delay, the FTC has publicly challenged over 300 “junk” patent entries in the FDA’s Orange Book, asserting that these “erroneous listings aim to ‘prolong the introduction of lower-cost generic alternatives into the market, thus maintaining artificially inflated prices for brand-name pharmaceuticals'”.66 This aggressive stance reflects a commitment to using all available tools to reduce barriers to generic competition and lower drug prices.67

- Application of Sherman Act and Clayton Act:

- Sherman Act: This foundational antitrust law outlaws “every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade” and any “monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy or combination to monopolize”.40 The Supreme Court, in

FTC v. Actavis, Inc. (2013), ruled that reverse payment settlements in the pharmaceutical industry are not per se illegal but should be analyzed under the “rule of reason” to determine if their anticompetitive effects outweigh any pro-competitive justifications.40 Product hopping cases, particularly those involving “hard switches” (where the older drug is removed from the market), have also been found anticompetitive under the Sherman Act, as seen in

New York v. Actavis regarding the Alzheimer’s drug Namenda.28 - Clayton Act: Section 7 of the Clayton Act specifically prohibits mergers and acquisitions that may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.40 Antitrust scrutiny extends to transactions aiming to expand influence into other markets, which may infringe both Section 2 of the Sherman Act and Section 7 of the Clayton Act.66

The application of antitrust laws to the pharmaceutical industry, particularly concerning patent abuses, highlights the fluidity of enforcement in IP-rich sectors. While clear abuses like explicit pay-for-delay agreements are actively targeted, more nuanced strategies such as patent thickets often operate within the technical bounds of patent law, making them challenging to address as direct antitrust violations. For instance, the Seventh Circuit’s decision in In re Humira Antitrust Litigation held that merely assembling a large patent portfolio (a “patent thicket”) is not, in itself, an antitrust violation.68 This necessitates a “surgical” approach to enforcement to avoid inadvertently disrupting legitimate innovation.41 This ongoing legal chess game requires continuous adaptation by both regulators and industry players.

Legislative Proposals and Judicial Trends: Shaping the Future

Policymakers across the political spectrum largely agree that the U.S. pharmaceutical pricing system is deeply flawed, with patent abuses being a significant contributing factor.53 This consensus has spurred various legislative proposals and judicial trends aimed at rebalancing the system.

- Efforts to Limit Patent Thickets and Product Hopping: Proposed bills seek to reduce barriers to generic entry and curb anti-competitive practices. These include measures to improve coordination between the USPTO and FDA, limit product hopping, penalize baseless citizen petitions, and strengthen the FTC’s authority to challenge pay-for-delay settlements.44 Some legislative proposals, such as the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act, specifically aim to cap the number of patents a drug company can assert in a lawsuit, for instance, limiting it to one patent per family in a thicket.44 These proposals directly respond to the industry’s strategic exploitation of the patent system.

- Calls for USPTO-FDA Coordination: Experts advocate for better coordination between the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to prevent the patenting of trivial variations that contribute to evergreening and patent thickets.69 The FTC has also taken direct action by challenging improper Orange Book listings, which are often used to trigger automatic delays for generic entry.67

The legislative response to strategic exploitation in the pharmaceutical patent landscape is a continuous process. Each legislative proposal is a direct reaction to a specific industry tactic, highlighting an ongoing “cat-and-mouse” game between pharmaceutical companies seeking to maximize exclusivity and policymakers attempting to rebalance the system for broader public benefit. This dynamic underscores the need for continuous adaptation in both industry strategy and regulatory frameworks.

International Perspectives and Comparative Approaches: A Global View

Patent evergreening and thickets are not confined to the U.S.; they are global concerns, with varying legal approaches and challenges across jurisdictions. Different countries offer diverse models for balancing innovation incentives with public access to medicines.

- Lessons from India’s Stricter Evergreening Laws: India’s Patents Act, particularly Section 3(d), stands out for its explicit prohibition against patenting new forms of known substances unless they demonstrate “enhanced efficacy”.22 This stricter standard has had a profound impact. In April 2013, India’s Supreme Court denied Novartis a patent for a new version of its cancer drug imatinib (Gleevec), ruling it was not sufficiently different from the original.22 This landmark decision has significantly influenced the availability of cheaper generics globally, as India is a major supplier of affordable pharmaceuticals to developing nations.26

- Canada, European Union, and Japan: Diverse Regulatory Frameworks:

- Canada: Canada has historically been considered lenient towards evergreening, with half of all patented drugs having multiple subsequent patents that extend the original patent’s lifetime by approximately 8 years.7 Its patent linkage system has led to extensive litigation, with generic firms sometimes having to litigate a single brand patent twice.13 Despite this, biosimilars tend to enter the Canadian market more quickly than in the U.S..76 There are ongoing calls for Canada to adopt stricter regulations similar to India’s.26

- European Union (EU): The EU allows secondary patents if they meet novelty and inventive step criteria, though there is increasing scrutiny around trivial modifications. The EU employs an “8+2+1” formula for regulatory data exclusivity (8 years of data exclusivity, 2 years of market exclusivity, plus a potential 1-year extension for new indications).13 EU competition law can be invoked against anti-competitive practices like patent clusters and thickets.79

- Japan: Japan’s patent linkage system ties regulatory approval of generics and biosimilars to an evaluation of innovator patents, with a heavy emphasis on administrative review rather than judicial mechanisms for infringement disputes.80 This system has been criticized for a lack of publicly accessible patent information, creating uncertainty.85 However, recent court rulings have awarded record damages in patent infringement cases, signaling a potential shift in judicial willingness to recognize substantial monetary awards.80

The varying approaches across these jurisdictions demonstrate how national policy choices and legal interpretations significantly influence market dynamics and health outcomes. Countries that prioritize public access through stricter patentability criteria or more robust antitrust enforcement (like India) tend to experience less severe impacts from evergreening and thickets. Conversely, systems that allow broader patenting of minor modifications or rely less on judicial review (like the U.S. in some aspects) may inadvertently foster these blocking strategies, leading to higher drug prices and delayed generic entry. This underscores that intellectual property policy is a powerful lever for shaping market dynamics and health outcomes on a global scale.

The Future of Pharmaceutical IP Policy: Balancing Incentives and Access

The ongoing debate surrounding pharmaceutical intellectual property policy centers on a fundamental challenge: how to strike the optimal balance between incentivizing groundbreaking innovation, which often requires immense investment and carries high risk, and ensuring broad public access to life-saving medicines at affordable prices.7

- Challenges of AI in Drug Discovery: The rapid emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in drug discovery is poised to significantly disrupt this balance. AI promises to dramatically reduce the cost, risk, and time traditionally associated with drug development.87 This technological leap raises fundamental questions about whether the current levels of intellectual property protection, which are predicated on high R&D costs, remain justified.87 A potential irony arises if AI-discovered drugs are deemed unpatentable because no human inventor is directly involved in the creative step, which would profoundly challenge the pharmaceutical industry’s long-standing business model.87 This presents a future scenario where AI is not just an R&D tool but a potential disruptor of the entire pharmaceutical IP framework, necessitating a fundamental re-evaluation of how innovation is incentivized and how access is ensured.

- Proposals for Reform: Academics and advocates propose a shift towards aligning innovation rewards more closely with the social value of innovations, rather than solely on market exclusivity and pricing power. Key proposals include:

- Ensuring broad access to innovations, both domestically and internationally.53

- Implementing targeted direct funding for R&D through public agencies like the National Institutes of Health, particularly for late-stage drug development and production.53

- Adopting value-based reimbursements for drugs, where payments are tied to a drug’s demonstrated added value for patients, rather than linking Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements to private-sector prices.53 This approach could also allow government payers to offer higher reimbursements for highly effective drugs and vaccines in areas where current prices are too low to stimulate development.53

- The experience with COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated that high rewards for developers can be successfully coupled with free access for patients, saving millions of lives globally.53 This model challenges policymakers to structure a pluralistic system of subsidies and rewards that fosters valuable innovations, reduces wasteful ones, and lowers out-of-pocket costs for patients.

The rise of AI in drug discovery presents a unique challenge to the existing IP paradigm. If drug development becomes substantially cheaper and faster due to AI, the traditional rationale for lengthy, broad monopolies weakens. This suggests that AI is not just a technological advancement but a potential disruptor of the entire pharmaceutical IP framework, necessitating a fundamental re-evaluation of how innovation is incentivized and how access is ensured in a future where drug discovery is increasingly automated. The future of pharmaceutical IP policy will likely involve navigating these complex technological, economic, and ethical considerations to forge a more equitable and efficient system.

Conclusion: Mastering the Patent Chessboard for Competitive Edge

The landscape of pharmaceutical patents is undeniably a complex chessboard, where innovator companies strategically deploy a formidable array of tactics—from the subtle extensions of evergreening and the impenetrable walls of patent thickets to the controversial maneuvers of pay-for-delay agreements—all meticulously designed to prolong market exclusivity and block competitors. These strategies, while often operating within the bounds of current legal frameworks, impose significant economic burdens on healthcare systems and patients, exacerbate health disparities by limiting access, and can paradoxically distort the very innovation they are meant to foster by incentivizing incremental rather than breakthrough R&D.

Yet, the game is not one-sided. Generic and biosimilar challengers are increasingly sophisticated, leveraging the nuances of legislation like the Hatch-Waxman Act and BPCIA, employing meticulous patent analysis and validity challenges, and fostering their own innovation through “design-around” strategies. The dynamic interplay between these powerful forces is constantly shaped by evolving regulatory oversight and legislative reforms, with international approaches offering diverse models for balancing incentives and access.

For business professionals in this high-stakes arena, mastering this patent chessboard—understanding the tactics employed by all players, anticipating the far-reaching consequences, and leveraging competitive intelligence tools like DrugPatentWatch—is not merely about legal compliance. It is the ultimate competitive advantage, crucial for navigating complex market dynamics, informing strategic R&D investments, and ultimately shaping the future of global healthcare. The ability to forecast patent expirations, identify generic entry opportunities, and understand the intricacies of patent litigation is paramount for any entity seeking to thrive in this intellectually rich yet fiercely competitive industry.

Key Takeaways

- Patents are a Dual-Purpose Instrument: While essential for incentivizing R&D and enabling companies to recoup massive investments (often billions of dollars over 10-15 years), their inherent monopolistic nature creates a tension with market competition and affordable access.

- Strategic Patenting Extends Monopoly: Innovator companies employ multi-layered patenting (secondary and tertiary patents) and tactics like evergreening (new formulations, indications) and product hopping (shifting patient bases) to artificially extend market exclusivity well beyond the core patent’s life.

- Patent Thickets Create Litigation Barriers: Dense webs of overlapping patents generate prohibitive litigation costs and protracted delays for generic entrants, effectively blocking competition regardless of individual patent strength.

- Pay-for-Delay Adapts and Persists: Despite legal challenges and increased scrutiny, “pay-for-delay” agreements have evolved into more complex “side business deals” that continue to delay generic entry, demonstrating the adaptability of anti-competitive tactics.

- Procedural Exploitation is Common: Innovators strategically exploit regulatory mechanisms such as the 30-month FDA stay and citizen petitions to create significant, often unwarranted, market delays for generic drugs.

- Economic and Social Costs are Substantial: These blocking tactics lead to inflated drug prices, costing consumers and healthcare systems billions annually (e.g., $3.5 billion/year from pay-for-delay alone), and exacerbate health disparities by limiting patient access to affordable medicines.

- Innovation Can Be Distorted: The intense focus on extending existing drug monopolies can divert valuable R&D resources away from truly novel, breakthrough therapies towards incremental, defensive patenting, thereby stifling genuine scientific progress.

- Generics Employ Sophisticated Counter-Strategies: Generic and biosimilar companies leverage the incentives of Paragraph IV certifications for 180-day exclusivity, conduct meticulous patent analysis to target weak patents, navigate the complex “patent dance” for biologics, and “design around” existing patents through creative innovation.

- Competitive Intelligence is Indispensable: Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are vital tools for generic companies to monitor patent expirations, litigation, and market dynamics, transforming raw data into actionable competitive advantage for strategic decision-making.

- Regulatory and Legislative Reforms are Ongoing: Governments and advocacy groups are actively pursuing antitrust enforcement, legislative changes (e.g., limiting patent thickets), and improved inter-agency coordination (USPTO-FDA) to rebalance the pharmaceutical intellectual property system.

- Global Disparities Highlight Policy Impact: International differences in patent laws (e.g., India’s strict evergreening rules versus the broader scope in the U.S.) underscore how national policy choices significantly influence market dynamics and access to medicines worldwide.

- AI Challenges Future IP Landscape: The rise of Artificial Intelligence in drug discovery may fundamentally alter R&D costs and timelines, potentially necessitating a re-evaluation of traditional patent incentives and intellectual property frameworks to ensure continued innovation and broad public benefit.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How do pharmaceutical companies legally extend drug patents beyond the typical 20-year term, and what is the primary motivation behind this?

Pharmaceutical companies legally extend drug patents through various “evergreening” strategies. These tactics include patenting new formulations, dosage forms, or drug delivery systems for existing medications; discovering and patenting new therapeutic indications for an already approved drug; or creating new combination drugs by pairing an existing active ingredient with another.1 They also establish “patent thickets” by accumulating numerous overlapping patents around a single product.33 The primary motivation behind these strategies is to prolong market exclusivity and maintain profitability. Given that the effective market life of a drug post-regulatory approval is often significantly shorter than the statutory 20-year patent term (typically ranging from 7 to 10 years), these extensions are crucial for maximizing revenue before generic competition drives down prices.6

2. What is the “patent dance” in the context of biosimilars, and how does it impact their market entry compared to generic small-molecule drugs?

The “patent dance” is a structured, pre-litigation information exchange process outlined in the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) for biosimilar approval.19 It involves a series of exchanges between the reference product sponsor (innovator) and the biosimilar applicant, where they share detailed patent lists, product information, and arguments regarding patent validity and infringement. The goal is to facilitate early resolution of patent disputes and narrow the scope of potential litigation.60 While intended to streamline biosimilar entry, this process is often complex, legally intricate, and can lead to protracted negotiations and litigation. Consequently, biosimilar market entry typically takes longer and is more complex than for generic small-molecule drugs, which primarily navigate the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway under the Hatch-Waxman Act.59 On average, biosimilars enter the market a little over 18 years after the reference product’s approval, a significantly longer delay compared to small-molecule generics.49

3. How do “patent thickets” specifically affect generic drug manufacturers, and what are the financial implications for the healthcare system?

“Patent thickets” create significant barriers for generic drug manufacturers by presenting a dense web of numerous, often overlapping, patents related to a single brand-name drug.33 To enter the market, generic companies must either wait for all relevant patents to expire or challenge them. Challenging these patents is an extremely costly and time-consuming endeavor, often costing millions of dollars per drug and leading to litigation that can last for many years (e.g., 18 years for Revlimid).35 The sheer volume and complexity of patents within a thicket make it economically unfeasible to challenge every single one, regardless of individual patent merit. This effectively delays generic entry, which in turn keeps drug prices artificially high. For the healthcare system, this translates to billions of dollars in wasted spending annually; for instance, an estimated $167 billion was lost on just three drugs due to delayed generic entry in the U.S. compared to the European Union market.35

4. What role does competitive intelligence, particularly platforms like DrugPatentWatch, play in the strategies of generic pharmaceutical companies?

Competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch are crucial tools for generic pharmaceutical companies to gain a strategic advantage in the market. They provide accurate, actionable, and timely intelligence by offering comprehensive databases on patent expiry dates, generic entry opportunities, patent litigation status, and drug sales data.18 This intelligence enables generic companies to: identify lucrative low-competition markets where fewer existing manufacturers mean higher pricing power and better margins 18; anticipate brand-name strategies, including potential evergreening or product hopping maneuvers; track first-to-file opportunities for the valuable 180-day market exclusivity; and inform their R&D and market entry decisions with data-driven precision, thereby transforming raw data into a decisive competitive advantage.18

5. How is the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in drug discovery expected to impact the future of pharmaceutical patent policy and market competition?

The rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in drug discovery is poised to significantly impact pharmaceutical patent policy and market competition by potentially reducing the traditional high costs, risks, and lengthy timelines associated with drug development.87 This technological advancement challenges the fundamental economic justification for the current patent system, which is largely built on compensating for these substantial R&D burdens. If AI makes drug discovery substantially cheaper and faster, the rationale for lengthy, broad monopolies may weaken. Furthermore, AI’s role in invention raises complex questions about patentability itself, particularly if an AI system, rather than a human, is perceived as the primary inventor. This could necessitate a fundamental re-evaluation of patent laws and intellectual property frameworks to ensure they continue to incentivize innovation effectively while promoting equitable access to new medicines in an increasingly AI-driven pharmaceutical landscape.87

References

.1# Using Drug Patents to Block Competitors: The Tactics and Consequences

The pharmaceutical industry operates at the nexus of groundbreaking scientific discovery, immense financial investment, and critical public health needs. At the heart of this intricate ecosystem lies the drug patent system, a legal framework designed to incentivize innovation by granting temporary monopolies to pioneering companies. Yet, this very mechanism, while fostering advancements, has become a sophisticated arena where innovator companies deploy a formidable array of tactics not just to protect their discoveries, but to actively block competitors and extend their market exclusivity. This report delves into these intricate strategies, dissecting their mechanics, analyzing their profound economic and social consequences, and exploring the evolving landscape of counter-strategies and regulatory oversight. For business professionals navigating this high-stakes environment, understanding these dynamics is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical imperative for competitive advantage and strategic foresight.

The Bedrock of Biopharmaceutical Innovation: Understanding Drug Patents

Pharmaceutical patents form the bedrock of intellectual property protection in the drug industry, safeguarding the innovations that drive medical advancements. These patents are distinct in their subject matter but adhere to universal patentability standards, playing a crucial role in a drug’s market journey.

Defining Pharmaceutical Patents: A Foundation of Exclusivity

Pharmaceutical patents are a form of intellectual property that grants inventors, typically pharmaceutical companies, exclusive rights to sell a newly developed drug for a specified period, generally 20 years from the date of patent application filing.1 This temporary monopoly prevents other entities from manufacturing, using, selling, or importing the patented invention without explicit permission, thereby providing a powerful incentive for continued Research and Development (R&D) and fostering groundbreaking scientific discoveries.1 In the United States, these patents are granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

The very nature of pharmaceutical patents presents a fundamental tension. While they are explicitly designed to incentivize the colossal investments required for R&D—often billions of dollars over many years—the exclusivity they confer inherently creates a monopolistic environment. This allows the patent holder to set drug prices without direct competition, enabling them to recoup their substantial investment and generate profits.2 However, from a broader societal perspective, this temporary monopoly can stifle competition and hinder societal progress by limiting access to potentially life-saving medications.4 This system is, in essence, a deliberate competition barrier artificially established to compensate for the high costs and lengthy development cycles of innovative drugs.4

Types of Drug Patents: A Multi-Layered Shield

Pharmaceutical companies employ a diverse array of patent types to secure comprehensive protection for their innovations, extending beyond the core active ingredient to encompass various aspects of a drug’s development and application. This multi-layered approach is a strategic imperative designed to create a robust defensive perimeter around a drug.

- Composition of Matter Patents: These are widely considered the most valuable and sought-after patents in the pharmaceutical industry. They protect the specific chemical compound that constitutes the active ingredient of a drug, offering the broadest competitive advantage by preventing others from producing chemically identical versions.1

- Method of Use Patents: These patents protect a specific, novel way of utilizing an already known compound, drug, or product. This can include newly discovered therapeutic uses for existing drugs, allowing companies to expand the market for their innovations.1

- Formulation Patents: These safeguard the specific composition of a drug, including its inactive ingredients, unique combinations, delivery mechanisms (e.g., tablets, injections, extended-release systems), or specialized packaging that optimizes drug performance.1

- Process Patents: These cover the methods and processes used to manufacture the drug. They are essential for protecting proprietary manufacturing techniques that can be critical to the drug’s efficacy and safety, thereby creating additional barriers to entry for competitors.5

- Design Patents: Beyond the chemical or functional aspects, these patents protect the ornamental design of packaging and delivery systems, such as inhalers or injectors, adding another layer of intellectual property protection.10

- Tertiary Patents: This category often involves using medical devices paired with an active ingredient that may be off-patent to prolong market exclusivity. These patents demonstrate the creative lengths companies go to maintain market control.7