Section 1: Introduction: The Paradox of Pharmaceutical Patents

The modern patent system is founded on a fundamental societal bargain: in exchange for the public disclosure of a new and useful invention, the state grants the inventor a temporary, exclusive right to commercialize it.1 This temporary monopoly, typically lasting 20 years from the date of filing, is designed to incentivize the costly and high-risk process of innovation, allowing creators to recoup their investments and fund future discovery.2 In no sector is this bargain considered more critical than in the pharmaceutical industry, where the journey from a laboratory concept to a market-approved, life-saving medicine can consume billions of dollars and over a decade of research and development (R&D).3 Once this period of exclusivity ends, the public receives its benefit: the knowledge is added to the public domain, and competitors can enter the market, driving down prices and increasing access.

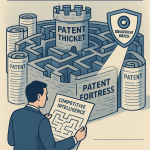

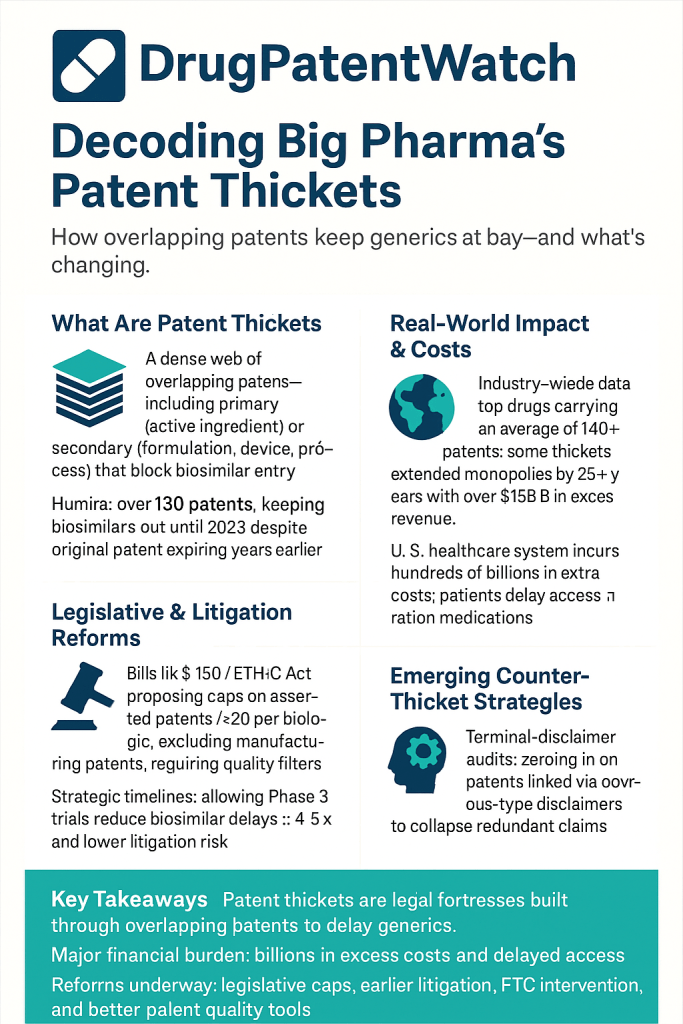

However, a growing body of evidence suggests this foundational bargain has been systematically distorted within the United States pharmaceutical sector. The instrument of this distortion is the “patent thicket,” a term that has evolved from legal jargon into a centerpiece of the debate on drug pricing and healthcare affordability. A patent thicket is not merely a large collection of patents; it is a “dense web of overlapping intellectual property rights that a company must hack its way through in order to actually commercialize new technology”.5 In the pharmaceutical context, this manifests as a brand-name drug company accumulating dozens, or even hundreds, of patents around a single blockbuster drug.1 These patents often cover not the core active ingredient, which is protected by an initial “primary” patent, but a vast array of secondary characteristics such as manufacturing processes, new dosages, methods of administration, or different crystalline forms of the molecule.1 The European Commission has also referred to this phenomenon as the creation of ‘patent clusters’.6

This report argues that pharmaceutical patent thickets are not an unforeseen anomaly but a predictable and rational corporate response to the unique legal, regulatory, and commercial framework governing drug patents in the United States. This framework, while ostensibly designed to foster innovation, has inadvertently created a set of perverse incentives that prioritize the extension of monopolies on existing, highly profitable drugs over the riskier pursuit of novel therapies. This strategic manipulation of the patent system imposes a staggering economic burden on patients, employers, and government payers; stifles the very competition the system is meant to eventually foster; and alters the trajectory of medical innovation itself. The prevalence and density of these thickets are most pronounced in the U.S., not because of the inherent nature of patent law, but as a direct consequence of specific domestic policy choices that diverge sharply from those of other developed nations.1

The strategic objective of a patent thicket is to create a litigation landscape so complex, so costly, and so time-consuming to navigate that would-be generic or biosimilar competitors are deterred from even attempting to enter the market.1 This transforms the role of a patent from a simple shield protecting a single invention into an offensive legal weapon of attrition. The success of the strategy lies not in the unassailable strength of any individual patent within the thicket, but in the collective, prohibitive cost of challenging the entire portfolio.9 For a lower-cost generic to reach patients, its manufacturer must successfully invalidate

every single patent asserted from the thicket—a daunting and financially ruinous proposition.9 The brand-name company, in contrast, needs only one patent to be upheld to maintain its monopoly. In this environment, the legal system itself becomes the primary barrier to market entry. The competitive battle is won not on the scientific merits of the invention or the legal validity of the core patent, but on the challenger’s financial inability to sustain a multifront, multi-year legal war. This represents a systemic exploitation of legal process, where the cost of seeking justice exceeds the potential reward of market competition, fundamentally undermining the principles the law is intended to uphold and setting the stage for the complex dynamics explored in this report.

Section 2: The Legal Architecture of Exclusivity in the United States

The formidable market protection enjoyed by brand-name pharmaceuticals in the United States is not derived from a single source. Instead, it is built upon two separate but deeply intertwined pillars: patent exclusivity, granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and regulatory exclusivity, granted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).2 These two systems of protection can run concurrently, overlap, and cover different aspects of the same drug product, creating a multi-layered and often lengthy period of monopoly that is far more complex than the standard 20-year patent term.11 Understanding the distinct roles of these agencies and the landmark legislation that governs their interaction is essential to deconstructing how patent thickets are enabled.

The Dual Pillars of Protection

The USPTO is the federal agency responsible for examining patent applications and granting utility patents for inventions that meet the statutory criteria of being new, useful, and non-obvious.2 A granted patent confers upon its owner the exclusive right to make, use, sell, and import the invention for a term of 20 years from the application filing date.2 In the pharmaceutical context, these patents can claim a wide array of inventions, from the chemical compound itself to its formulation, method of use, or manufacturing process.2 A critical factor in the formation of patent thickets is the USPTO’s historically permissive standards for what constitutes a “non-obvious” improvement and its willingness to grant numerous “secondary” patents for minor modifications to an existing drug.1 While the USPTO has stated its focus is on issuing “robust and reliable patents” and ensuring the system is not used to “improperly delay” generic competition, this creates an inherent tension in its mission.12

The FDA, on the other hand, is the primary public health agency responsible for ensuring the safety and efficacy of drugs and biologics before they can be marketed.2 Distinct from the patent system, the FDA grants its own periods of regulatory exclusivity for certain types of drugs upon approval. These exclusivities are designed to incentivize development in specific areas. For example, a New Chemical Entity (NCE) may receive five years of exclusivity, while a drug for a rare “orphan” disease can receive seven years.11 During these periods, the FDA is barred from approving a generic or biosimilar competitor, regardless of the patent status.2 These two forms of exclusivity—patent and regulatory—operate in parallel, and a drug can benefit from both simultaneously, further extending its time on the market without competition.11

The Role of the FDA and Its Key Publications

The FDA’s role extends beyond granting exclusivity; it also serves as the gatekeeper of information that is central to the patent challenge process. It maintains two critical publications that have become battlegrounds in the fight over generic entry.

- The Orange Book: Officially titled “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” the Orange Book is the FDA’s comprehensive list of approved small-molecule drugs. Crucially, under the Hatch-Waxman Act, brand-name manufacturers are required to list the patents that claim their drug or its method of use in this publication.2 The Orange Book thus becomes the definitive reference for generic companies seeking to challenge those patents. Its central role has also made it a tool for anticompetitive behavior. In 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) took the unprecedented step of challenging over 100 patent listings in the Orange Book as improper, alleging they were for drug-device components rather than the drug itself and were listed solely to block competition.13

- The Purple Book: The equivalent publication for large-molecule biologics, the Purple Book lists licensed biological products and their biosimilars.11 Historically, a major point of contention was that the Purple Book did not contain patent information, creating significant uncertainty and risk for biosimilar developers who had no clear way of knowing which patents they might be accused of infringing.11 The Biologic Patent Transparency Act, part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, and the Purple Book Continuity Act of 2020 have sought to remedy this by requiring brands to list patents in the Purple Book, but this requirement is often triggered only after litigation has begun, limiting its proactive utility.14

Landmark Legislation Enabling the System

Two pieces of legislation form the bedrock of the modern pharmaceutical patent landscape in the U.S., creating the very pathways and procedures that are now strategically exploited.

- The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch-Waxman Act): This act is a grand compromise that created the modern generic drug industry while also offering new protections to brand-name manufacturers.

- Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) Pathway: The Act’s most significant contribution to competition was the creation of the ANDA pathway. This allows generic manufacturers to gain FDA approval by demonstrating their product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug, relying on the brand’s original safety and efficacy data and thereby avoiding the need to conduct their own costly and duplicative clinical trials.2

- Paragraph IV Certification and the 30-Month Stay: The Act also established a formal process for generic companies to challenge a brand’s patents. A generic applicant can file a “Paragraph IV certification,” asserting that a patent listed in the Orange Book is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.2 However, if the brand-name company responds by filing a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days, it triggers an

automatic 30-month stay, during which the FDA is generally prohibited from granting final approval to the generic drug.2 This mechanism fundamentally alters the strategic calculus of patent litigation. The mere act of filing a lawsuit, irrespective of the underlying patent’s strength or merits, grants the brand manufacturer a substantial, often risk-free, extension of its monopoly revenue. This transforms patent litigation from a tool for resolving genuine disputes into a low-risk, high-reward business strategy, directly incentivizing the accumulation of even weak or questionable secondary patents, as each one can serve as a trigger for another lawsuit and another guaranteed delay. This legislative feature is a key structural driver of the patent thicket problem for small-molecule drugs. - The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA): Enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act, the BPCIA created the abbreviated approval pathway for biosimilars, the “generic” versions of complex, large-molecule biologic drugs.

- The “Patent Dance”: Instead of the Paragraph IV process, the BPCIA established a highly complex, multi-step process for exchanging patent information and litigating disputes, colloquially known as the “patent dance”.1 This process involves a series of prescribed deadlines for the two parties to disclose lists of patents they believe are relevant and their arguments regarding infringement and validity.

- Unlimited Patent Assertions: A crucial difference from Hatch-Waxman is that the BPCIA framework allows brand manufacturers to assert a potentially unlimited number of patents against a biosimilar challenger.1 This feature makes the BPCIA landscape particularly conducive to patent thicket strategies, as a brand can overwhelm a biosimilar competitor with a massive volume of patents, each requiring a costly and complex legal defense.

The interaction between these two agencies and two legislative acts creates a uniquely American system. There is a fundamental misalignment of purpose between the agencies that is ripe for exploitation. The USPTO can grant a patent based on purely technical, non-clinical grounds—for instance, for a minor change to a drug’s formulation that offers no proven therapeutic benefit to patients.16 However, once that patent is listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, it becomes a powerful legal tool that can be used to trigger a 30-month stay and block a therapeutically equivalent, lower-cost generic from reaching the market. A patent granted on “trivial” grounds by one agency can thus be used to obstruct patient access to affordable medicine regulated by another. This regulatory gap, born from the siloed operations of the USPTO and FDA, is the fertile ground in which pharmaceutical patent thickets have grown and flourished. The recent push for enhanced USPTO-FDA collaboration is a direct, albeit belated, admission of this long-standing systemic flaw.12

Section 3: Anatomy of a Thicket: Corporate Strategies and Tactics

The construction of a pharmaceutical patent thicket is not a random accumulation of intellectual property but a deliberate and sophisticated corporate strategy. It relies on a specific set of tactics designed to extend a drug’s market monopoly far beyond the 20-year term of its foundational patent. This “lifecycle management” strategy is built upon a clear distinction between primary and secondary patents and is executed through practices like “evergreening” and “product hopping,” all held together by a crucial legal mechanism known as the terminal disclaimer.

Primary vs. Secondary Patents: The Building Blocks

The architecture of a patent thicket begins with understanding its two fundamental components.1

- Primary Patents: These are the foundational patents that protect the core of a new medicine. Typically, this is the patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the novel molecule that produces the therapeutic effect. This primary patent grants the initial 20-year monopoly and is the basis for the drug’s original market entry.1

- Secondary Patents: These are patents filed later in a drug’s lifecycle, often years after it has been approved by the FDA. They do not cover the core API but instead target a wide array of peripheral, incremental, or follow-on inventions related to the original drug.1 The scale of this practice is vast. One analysis by the Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge (I-MAK) found that for top-selling drugs, an average of 66% of patent applications are submitted

after the drug has already received FDA approval.1 Another study found that 78% of all new drug-related patents are for existing medicines, not novel therapies.3 This timing strongly indicates that the primary motivation is not to protect the initial invention but to construct defensive legal barriers against future competition.

“Evergreening”: The Overarching Strategy of Lifecycle Management

“Evergreening” is the overarching corporate strategy that employs secondary patents to build thickets and extend market exclusivity.1 It is a deliberate, systematic effort to “artificially extend the life of a patent” to maintain monopoly pricing and block competition from generics and biosimilars.1 This is achieved by layering new, 20-year patents for minor modifications on top of the original, expiring patent. Common evergreening tactics include patenting 2:

- New Formulations: This can involve creating an extended-release version of a pill, developing a new salt form (polymorph) that might offer slightly different stability or solubility, or changing the inactive ingredients.1

- New Methods of Use or Indications: This involves patenting the use of a drug that is already on the market to treat a different disease or condition. While this can represent a genuine and valuable innovation, it is also a common tactic to add another layer of patents to an existing product.2

- New Dosages or Methods of Administration: Companies can obtain new patents for offering the drug in a different strength (e.g., a 5mg pill instead of a 10mg pill) or for a new delivery system. AbbVie’s patent thicket for Humira, for example, famously included patents on the injector device used to deliver the medication and even a separate patent on the device’s firing button.9

- Fixed-Dose Combinations: This involves combining two or more existing drugs, often generics, into a single pill and patenting the combination as a new invention.7

This strategic approach exploits a crucial semantic gap in intellectual property law. Industry defenders argue that these secondary patents protect legitimate “inventions,” which is often technically true under the USPTO’s standards.2 Critics, however, contend that these are frequently “trivial” changes that do not represent meaningful clinical “innovation” for patients.16 A minor modification to a manufacturing process or a new dosage strength might meet the low legal bar for being a “new and non-obvious” invention, but it does not necessarily provide any additional therapeutic benefit. The patent system, as it currently operates in the U.S., rewards the creation of these new “inventions” regardless of their innovative value. This allows companies to build a thicket of legally defensible patents that contribute little to public health, thereby shifting R&D focus from the high-risk discovery of new cures to the low-risk, high-reward process of finding new ways to patent existing ones.

“Product Hopping”: Stranding the Generic Market

“Product hopping” is a particularly aggressive evergreening tactic designed to neutralize the threat of generic competition entirely.16 The strategy works as follows: shortly before the patents on a blockbuster drug are set to expire, the brand-name company will launch a “new and improved” version of the drug. This new version is typically only slightly modified—for example, a change from a capsule to a tablet, or a new extended-release formulation—but it is covered by a new set of later-expiring patents.17 The company then puts its entire marketing force behind convincing doctors and patients to switch to the new version. In its most aggressive form, known as a “hard switch,” the company may even pull the original product from the market entirely.17

This tactic is devastating for generic competitors. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, a generic drug must prove it is bioequivalent to the specific brand-name product that was originally approved (the “reference listed drug”).11 If the original product is no longer on the market, it becomes difficult or impossible for the generic to conduct the necessary comparison studies.10 Even in a “soft switch,” where the original product remains available, the mass migration of patients to the new version decimates the market for the incoming generic, making it financially unviable to launch. The case of AstraZeneca’s heartburn medication Prilosec is a classic example, where the company successfully “hopped” the market to its next-generation drug, Nexium, just as Prilosec’s patents were expiring.16

The Legal Linchpin: Terminal Disclaimers

A key legal mechanism that enables the proliferation of duplicative patents within a thicket is the terminal disclaimer. Often, when a company files an application for a secondary or “off-spring” patent, the USPTO will reject it on the grounds of “obviousness-type double patenting,” meaning the new invention is not patentably distinct from the original “parent” patent.9 To overcome this rejection, the company can file a terminal disclaimer. This is a legal statement that agrees to link the expiration date of the new, duplicative patent to the expiration date of the original parent patent.9

On its face, this seems to prevent the company from extending its monopoly timeline. However, its strategic value is immense. By filing a terminal disclaimer, the company is allowed to obtain the new patent, even though it is not meaningfully different from the first. This allows the company to build a dense thicket of dozens of legally separate but substantively overlapping patents. As detailed research by legal scholar Dr. Rachel Goode has shown, some of the most formidable patent thickets, such as Humira’s, are comprised of up to 80% duplicative patents linked together by terminal disclaimers.21

This creates a situation of profound legal and financial asymmetry, a form of “asymmetrical warfare” in litigation. To enter the market, a generic challenger must prove that every single patent in the thicket is invalid or not infringed.9 The brand-name company, by contrast, only needs

one of its hundred-plus patents to be upheld in court to block competition.10 The cost to challenge a single patent through an

inter partes review (IPR) at the USPTO is estimated to be between $775,000 and $1 million.18 Faced with a thicket of 100 patents, a challenger is looking at a potential legal bill approaching $100 million, a nearly insurmountable barrier to entry. This asymmetry creates a market failure. The decision to launch a generic is no longer based on the scientific ability to manufacture the drug or the legal weakness of the primary patent. It becomes a purely financial calculation of whether the company can survive the guaranteed, multi-front, and ruinously expensive litigation assault. This deters competition even when the brand’s patents are weak, effectively granting a monopoly far beyond what the law intended and making it a rational business decision for generic companies to accept “pay-for-delay” settlements to avoid the fight.7

Section 4: Economic Consequences: The Price of Prolonged Monopoly

The strategic construction of patent thickets is not an abstract legal exercise; it carries profound and quantifiable economic consequences that ripple through the entire U.S. healthcare system. By systematically delaying the entry of lower-cost generic and biosimilar drugs, these tactics maintain artificially high prices for blockbuster medications, imposing a direct and substantial financial burden on government programs, private insurers, and individual patients.

Quantifying the Cost to the U.S. Healthcare System

The most direct way to measure the cost of patent thickets is to understand the value of the competition they prevent. The introduction of generic drugs is the single most powerful mechanism for reducing prescription drug spending in the United States. Data shows that the market entry of the first generic competitor triggers an average price drop of 39% relative to the brand-name price. When six or more generic competitors are on the market, prices can plummet by more than 95%.15

Collectively, the savings generated by this competition are immense. In 2022 alone, generic and biosimilar medicines saved the U.S. healthcare system $408 billion.15 Over the decade ending in 2023, these savings amounted to a staggering $3.1 trillion.15 These figures, typically framed as a success of the Hatch-Waxman Act, can be inverted to reveal a different story. Every dollar “saved” by generics represents a dollar of monopoly rent that was previously being extracted by a brand-name drug. Therefore, this annual savings figure also serves as a powerful proxy for the annual

cost of patent-protected monopoly pricing. When a patent thicket successfully delays generic entry for a class of drugs by even a single year, the cost to the system is the portion of those hundreds of billions in savings that are not realized.

Specific case studies make this cost tangible. The five-year delay in the U.S. market entry of biosimilars for Humira, directly attributable to its patent thicket, is estimated to have cost the American healthcare system anywhere from tens of billions of dollars to over $80 billion.1 An analysis of just five drugs with patent thickets found they accounted for more than $16 billion in lost savings in a single year.17 The extended monopoly on the cancer drug Revlimid, protected by its own thicket, cost Americans an estimated $45 billion.24

Table 4.1: The Economic Scale of Generic Competition vs. Monopoly Pricing

| Year | Total Annual Savings from Generics/Biosimilars | Brand-Name Drugs’ Share of Prescriptions | Brand-Name Drugs’ Share of Spending | Generic Drugs’ Share of Prescriptions | Generic Drugs’ Share of Spending |

| 2020 | $338 billion 15 | ~10% 15 | ~80% 25 | ~90% 15 | ~20% 25 |

| 2021 | $373 billion 15 | ~10% 15 | ~80% 25 | ~90% 15 | ~20% 25 |

| 2022 | $408 billion 15 | ~10% 15 | ~80% 25 | ~90% 15 | ~20% 25 |

| 2023 | $445 billion 15 | 10% 15 | 86.9% 15 | 90% 15 | 13.1% 15 |

This data starkly illustrates the economic leverage of monopoly pricing. Brand-name drugs, which constitute a small fraction of all prescriptions dispensed, are responsible for the vast majority of total pharmaceutical spending. This dynamic highlights that the drug pricing crisis is overwhelmingly concentrated in the small segment of the market protected by patents and, increasingly, by the patent thickets that extend their lifespan.

The Burden on Payers and Patients

The immense costs of prolonged monopolies are not abstract figures; they are borne by every participant in the healthcare system. Public payers like Medicare and Medicaid are heavily impacted. In 2022, generics saved Medicare $130 billion, demonstrating the massive exposure the program has to high brand prices.15 Commercial health plans, which cover most working-age Americans, saved $194 billion that same year.15

Ultimately, these costs are passed down to patients, either through higher insurance premiums and taxes or directly through out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy counter. The average copayment for a generic prescription in 2023 was $7.05, compared to an average of $56.12 for a brand-name drug.15 The financial strain of these high prices has a direct and regressive impact on public health. One study found that approximately 37% of Americans earning less than $40,000 annually report skipping doses, cutting pills in half, or forgoing prescriptions entirely due to cost.23 The case of Revlimid is illustrative: as its price soared from around $6,000 per month in 2002 to $24,000 per month in 2022 under the protection of its patent thicket, it became unaffordable for many of the cancer patients who needed it.24

This system also functions as a direct driver of healthcare inflation, a major macroeconomic concern. Patent thickets do not just maintain a high price; they enable further price increases on that monopoly price because there is no competitive pressure to restrain them. The price of Humira was increased by 18% per year between 2012 and 2016, and the price of Revlimid was raised 22 times after its launch.26 This pricing power, shielded by a wall of patents, allows a small number of products to have an outsized inflationary effect on the entire healthcare sector.

Perverse Incentives and the Role of Inequality

In certain contexts, particularly with cures for infectious diseases, the monopoly pricing enabled by patents creates deeply perverse incentives. Consider Gilead’s breakthrough drug for Hepatitis C, sofosbuvir, which was launched at a price of $84,000 for a course of treatment.28 From a purely commercial standpoint, providing universal access to a cure at an affordable price would be a poor business decision, as it would rapidly shrink and eventually eliminate the market for the drug. A more profitable strategy is to price the drug at a level that is accessible to the affluent, while leaving the disease to circulate within poorer populations who cannot afford it. This ensures a persistent reservoir of the disease and, consequently, a sustained future demand for the cure. In this grim calculus, the patent holder profits from the very existence of those who cannot afford its product, as they may infect others who can.28

This dynamic reveals how patent-driven monopoly pricing intersects with and exacerbates economic inequality. A rational, profit-maximizing firm will set its price at a point that excludes a certain portion of the potential market. The shape of the demand curve, which is heavily influenced by income distribution, dictates the optimal price. In a society with high levels of inequality, the demand curve can become highly convex, meaning there is a small population with very high willingness and ability to pay. In such a scenario, it becomes most profitable for the company to set an exorbitant price that serves only this wealthy minority, effectively pricing out the vast majority of the patient population.28 Therefore, greater financial inequality broadens the exclusion from patented medicines, and the patent system, in turn, deepens the public health impact of that inequality.

Section 5: The Innovation Paradox: Fostering Discovery or Stifling Competition?

The debate over patent thickets cuts to the core of the patent system’s purpose: do they represent a legitimate reward for ongoing innovation, or do they distort the system’s incentives, stifling competition and redirecting resources away from true medical breakthroughs? Both sides of this “innovation paradox” present compelling arguments, but a close examination of corporate behavior and empirical data reveals a system whose incentives may have gone awry.

The Industry Argument: Recouping R&D and Rewarding Incremental Innovation

The primary defense of robust and extensive patenting practices is rooted in the economics of drug development. Pharmaceutical companies and their advocates argue that strong patent protection is absolutely necessary to justify the massive, high-risk investments required to bring a new drug to market. Estimates for this cost vary widely but are consistently substantial, ranging from $161 million to as high as $4.5 billion per approved drug, with the industry as a whole spending $83 billion on R&D in 2019 alone.2 The temporary monopoly granted by a patent is what allows a company to recoup these immense costs and generate the profits needed to fund the next generation of research.2

From this perspective, every patent in a thicket, including secondary patents, protects a “legitimate innovation” that has been duly examined and found to be new, useful, and non-obvious by the USPTO.20 Defenders argue that complex products, whether a smartphone or a biologic drug, naturally require multiple patents to protect their various components and features.20 They further contend that secondary patents are not trivial, but often represent valuable incremental innovations that improve a drug’s safety, efficacy, or patient convenience. For example, a new extended-release formulation might reduce the number of pills a patient needs to take each day, while a modified version of a drug could have significantly fewer side effects.7 Without the ability to patent these follow-on improvements, companies would have little incentive to invest in the costly research required to develop them.

A common defense is to draw an analogy to the high-technology sector, where companies like Apple and Samsung hold vast patent portfolios.20 This argument posits that large numbers of patents are simply a feature of modern, complex innovation and that the pharmaceutical industry is no different. However, this “high-tech analogy” has been shown to be a false equivalence. A deep analysis of the purpose of these portfolios reveals a fundamental difference. In the technology sector, a single product like a smartphone is an assemblage of thousands of patented components owned by

many different companies. Firms amass large patent portfolios primarily for defensive cross-licensing—a strategy of “I’ll let you use my patents if you let me use yours”—which is necessary to gain the freedom to operate and participate in the market.32 In stark contrast, in the pharmaceutical industry, a single company typically owns

all the relevant patents for a single drug product. They do not need to license technology from competitors to bring their product to market. Therefore, the purpose of accumulating patents is not defensive or collaborative, but purely exclusionary: to block rivals from entering the market.33 This distinction dismantles a key industry talking point and highlights the uniquely anticompetitive nature of pharmaceutical patent thickets.

The Critic’s Counterargument: A Shift from Breakthroughs to Lifecycle Management

Critics of patent thickets argue that they represent a fundamental distortion of the patent system’s innovative purpose. Rather than encouraging the development of truly new medicines, the system incentivizes a shift in R&D resources toward low-risk, high-reward “lifecycle management” strategies for existing blockbuster drugs.3 The goal becomes not discovering the next cure, but finding endless new ways to patent the last one.

The data supporting this view is compelling. A significant majority of new patents associated with drugs are for medicines that are already on the market. One study found this figure to be 78%.3 Another analysis of the 10 highest-grossing drugs in 2021 revealed that 72% of their patent applications were filed

after they had already received FDA approval.3 This strategic post-approval patenting is seen as a clear indication of gaming the system to protect revenue streams rather than advancing public health.24 As one expert noted, the current system often rewards “legal maneuvering far more than scientific breakthroughs”.13

This redirection of resources carries a significant, if unquantifiable, opportunity cost. The time, money, and scientific talent spent developing and patenting a new subcutaneous injection method for Keytruda, for example, were resources that could have been dedicated to researching a novel cancer therapy.13 While we can calculate the billions of dollars lost to delayed generic competition, we can never calculate the societal value of the breakthrough treatments that were never discovered because R&D funding was diverted to a “product hopping” scheme. This represents the profound and hidden public health consequence of the innovation paradox.

Empirical Evidence on R&D and Innovation

The academic literature on the topic suggests that, far from spurring innovation, patent thickets can actively hinder it. Theoretical models show that dense webs of overlapping patents increase the transaction costs of innovation, forcing companies to navigate a legal minefield and potentially pay royalties to multiple parties, which can discourage R&D investment.35

Empirical studies have borne this out, finding that patent thickets can reduce R&D investment and lead to an overall decrease in innovation, particularly in industries with complex technologies like biologics.35 One econometric analysis found that while firms may not necessarily reduce their R&D spending in direct response to growing thickets, the thickets themselves have a negative impact on a firm’s market value, holding its R&D and patenting activities constant.36 This suggests that financial markets view thickets not as value-creating assets, but as costly liabilities to be managed. The very presence of a dense thicket can create a formidable barrier to entry, deterring smaller companies and startups from even attempting to innovate in that therapeutic area, which slows the overall pace of scientific progress and concentrates market power in the hands of a few incumbent firms.8

Section 6: Case Studies in Strategic Patenting: The Blockbuster Playbook

The strategies used to construct and leverage patent thickets are best understood through the examination of their real-world application. The cases of several blockbuster drugs—Humira, Keytruda, Revlimid, and Eliquis—provide a clear and data-rich playbook for how pharmaceutical companies have used the U.S. patent and regulatory system to extend their monopolies, generating billions in additional revenue at a significant cost to the healthcare system.

Humira (AbbVie): The Archetype of the Patent Thicket

AbbVie’s strategy for its anti-inflammatory drug Humira is the quintessential example of a patent thicket. It is the case most frequently cited by critics and policymakers as evidence of systemic abuse.

- The Thicket: AbbVie constructed a legal fortress around Humira, filing over 250 patent applications and securing at least 132 to 136 granted patents in the U.S..9 An astonishing 89% of these patent applications were filed

after Humira received its initial FDA approval in 2002.27 Further analysis revealed the composition of this thicket: peer-reviewed research concluded that approximately 80% of the patents in Humira’s U.S. portfolio were “non-patentably distinct,” meaning they were legally duplicative of each other and held together by terminal disclaimers.21 - The Impact: This impenetrable wall of patents achieved its strategic goal. Biosimilar versions of Humira entered the much stricter European market in 2018, but AbbVie’s U.S. thicket delayed their entry into the American market until 2023—a full five-year difference.1 The economic consequences of this delay were staggering, with estimates of the excess cost to the U.S. healthcare system ranging from $80 billion to over $100 billion.23 In the years leading up to biosimilar competition, Humira was a financial juggernaut for AbbVie, generating daily revenues estimated between $47.5 million and $57 million.13

- The Legal Battle: The Humira thicket was the subject of a major antitrust lawsuit, In re Humira (Adalimumab) Antitrust Litigation, which argued that the sheer volume of overlapping and allegedly weak patents was a form of sham litigation designed to illegally monopolize the market.6 However, the courts ultimately dismissed the suit, ruling that AbbVie was “playing hardball” but had not done anything illegal, effectively concluding that the company had simply exploited the advantages conferred upon it by lawful practices.6 This ruling highlighted the difficulty of using current antitrust doctrine to combat patent thickets.

Keytruda (Merck): The “Patent Wall” and Product Hop

Merck’s blockbuster cancer immunotherapy, Keytruda, is projected to become the world’s best-selling drug, and it is protected by a formidable “patent wall” that illustrates the next generation of lifecycle management strategy.

- The Thicket: Merck has built a thicket around Keytruda comprising at least 129 to 180 patent applications, which have so far resulted in 53 to 78 granted patents.39 Mirroring the Humira playbook, the majority of these were filed after Keytruda’s 2014 FDA approval; over 60% of applications were post-approval, and 74% of them cover secondary aspects like new formulations or methods of treating different cancers, rather than the core anti-PD-1 antibody itself.39

- The Impact: The key patents on Keytruda’s active ingredient are set to expire in 2028. However, the secondary patents in the thicket create layers of protection that extend out to at least 2036.42 This additional eight-plus years of monopoly is projected to cost the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $137 billion in spending on branded Keytruda that would otherwise face biosimilar competition.42

- The Strategy: Merck is not just relying on the patent wall. The company is actively pursuing a “product hop” strategy. It is developing a new subcutaneous (under-the-skin) formulation of Keytruda and plans to launch it before the patents on the original intravenous version expire in 2028.13 The goal is to switch as many patients as possible to the new, patent-protected version, thereby eroding the market for any biosimilars of the original formulation that may launch after 2028.

Revlimid (BMS/Celgene): Abusing Safety Programs

The case of Revlimid, a crucial treatment for multiple myeloma, demonstrates how patent thicket strategies can be combined with the manipulation of regulatory requirements to block competition.

- The Thicket: Celgene (later acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb) filed over 200 patent applications on Revlimid, resulting in a thicket of dozens of granted patents.45

- The Unique Tactic: Celgene’s most potent tactic was to weaponize Revlimid’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). A REMS is a safety program mandated by the FDA for certain drugs with serious risks. Celgene argued that the strict controls of the Revlimid REMS program prevented it from providing samples of the drug to generic manufacturers.26 These samples are legally required for generic companies to conduct the bioequivalence studies needed for FDA approval. By refusing to provide samples, Celgene effectively used a patient safety program as an anticompetitive tool to physically block generic development for years.26

- The Impact: Shielded by its thicket and REMS strategy, Celgene raised the price of Revlimid over 22 times, with the cost for a one-month supply tripling from roughly $5,900 to over $19,000.19 These strategies successfully delayed widespread generic competition until early 2026, a full seven years after the drug’s primary patent expired in 2019. Even then, the entry is limited by volume due to settlement agreements.46

Eliquis (BMS/Pfizer): Mastering Extensions and Follow-ons

The blood thinner Eliquis, co-marketed by Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer, is a case study in how companies can leverage every available tool—statutory extensions, follow-on patents, and litigation—to maximize a product’s monopoly period.

- The Thicket: The Eliquis strategy combines a nearly five-year Patent Term Extension (PTE) granted by the USPTO to compensate for regulatory review delays with a thicket of follow-on patents.48 In total, the companies have filed 48 patents and been awarded 27.49

- The Impact: Eliquis’s original compound patent was set to expire on September 17, 2022. The combination of the PTE and litigation over a single key follow-on patent has successfully blocked generic entry until at least April 1, 2028, with some settlements potentially pushing it to 2031.48 This extended monopoly of nearly six years beyond the original patent expiration is projected to generate over

$50 billion in additional U.S. revenue for the brand-name companies—revenue that would have otherwise been subject to price-lowering generic competition.48

Table 6.1: The Blockbuster Playbook: A Comparative Case Study

| Drug (Manufacturer) | Primary Patent Expiration | Total Patents (Filed/Granted) | Key Strategies Employed | Years of Extended Monopoly | Estimated Cost to U.S. System |

| Humira (AbbVie) | 2016 18 | 250+ Filed / 130+ Granted 9 | Patent Thicket, Duplicative Patenting (Terminal Disclaimers) | 7 years (2016-2023) 27 | $80B+ 23 |

| Keytruda (Merck) | 2028 39 | 180+ Filed / 78+ Granted 39 | Patent Wall, Product Hopping (Subcutaneous Formulation) | 8+ years sought (2028-2036+) 42 | $137B+ 42 |

| Revlimid (BMS/Celgene) | 2019 26 | 200+ Filed / 117+ Granted 46 | Patent Thicket, REMS Abuse (Blocking Samples) | 7 years (2019-2026) 46 | $45B+ 24 |

| Eliquis (BMS/Pfizer) | 2022 48 | 48 Filed / 27 Granted 49 | Patent Term Extension (PTE), Follow-on Patents, Litigation | ~6 years (2022-2028) 48 | $50B+ 48 |

The recurring patterns in this playbook are unmistakable. In each case, a highly successful drug is protected by a vast number of post-approval, secondary patents. This legal fortress is then used to delay competition for many years beyond the expiration of the core patent, resulting in tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars in additional costs to the healthcare system. These are not isolated incidents but rather a systematic, repeatable, and highly profitable corporate strategy.

Section 7: The Global Context: A Comparative Analysis of U.S. and European Patent Regimes

The proliferation of dense pharmaceutical patent thickets is not a global phenomenon. It is a problem largely, and acutely, concentrated in the United States. A comparative analysis of the U.S. patent system with that of the European Union, administered by the European Patent Office (EPO), reveals that the U.S. is a significant outlier. The permissive legal standards and procedures of the USPTO create a favorable environment for building patent thickets that simply does not exist to the same extent in Europe.1 This divergence is not a matter of minor technical differences but reflects a fundamental difference in patenting philosophy, with profound real-world consequences for drug prices and market competition.

Contrasting Patentability Standards

The core of the divergence lies in the stringency of the criteria used to grant a patent. The EPO consistently applies stricter standards than the USPTO across several key doctrines, making it significantly harder to obtain the low-quality or duplicative secondary patents that form the bulk of a thicket.51

- Inventive Step vs. Non-Obviousness: To be patentable, an invention must not be obvious to a person skilled in the relevant field. While the U.S. and Europe share this principle, their application differs. The EPO employs a stricter “inventive step” analysis. It is more likely to reject a patent on a combination of previously known elements if a skilled person would have a reasonable expectation of success in combining them.51 The USPTO, in contrast, has often required evidence of a specific “teaching, suggestion, or motivation to combine” elements in the prior art, a higher bar for rejection that allows more marginal improvements to be patented.51

- Prohibition on Double-Patenting: This is perhaps the most critical difference. The EPO enforces a strict prohibition against granting two patents to the same applicant for the same subject matter.52 This rule directly prevents the kind of duplicative patenting that is rampant in U.S. thickets. As discussed, the U.S. system allows companies to overcome double-patenting rejections by filing a terminal disclaimer, a practice that facilitates the accumulation of numerous, substantively identical patents.9 The EPO’s firm stance closes this loophole.

- Added Matter Doctrine: The EPO’s “added matter” doctrine is a powerful structural barrier against the expansion of patent claims. It strictly prohibits an applicant from adding subject matter to a patent application that was not disclosed in the application as it was originally filed.1 This prevents the common U.S. practice of incrementally broadening or changing claims during the prosecution phase to capture later developments or build out a thicket from a single inventive concept.

- Enablement and Disclosure Requirements: The two systems also differ on the level of proof required to show an invention works. The EPO generally demands verifiable, experimental data within the patent application to demonstrate that the invention is reproducible and can be practiced across its full claimed scope.51 The USPTO, conversely, has been known to permit “prophetic examples”—hypothetical descriptions of experiments that have not actually been performed. This can lead to the granting of overly broad patents for inventions that may not be fully operable or reproducible.51

Table 7.1: Comparative Analysis of U.S. (USPTO) and European (EPO) Patent Standards

| Key Doctrine | USPTO Standard | EPO Standard | Implication for Patent Thickets |

| Inventive Step / Non-Obviousness | More permissive; often requires a specific “motivation to combine” prior art to prove obviousness.51 | Stricter “inventive step” analysis; a reasonable expectation of success in combining elements can suffice.51 | The USPTO’s standard allows more patents on minor or obvious modifications to be granted, which are the building blocks of thickets. |

| Double Patenting | Permitted through the use of “terminal disclaimers,” which link expiration dates but allow duplicative patents to issue.9 | Strictly prohibited; two patents cannot be granted to the same applicant for the same subject matter.52 | The EPO’s prohibition directly prevents the core tactic of amassing large numbers of legally duplicative patents around a single invention. |

| Added Matter | More flexible, allowing for the expansion of claims during prosecution. | Strict prohibition on adding matter not present in the original application, limiting claim expansion.1 | The EPO’s rule prevents the gradual build-out of a thicket from a single initial filing. |

| Data Requirements (Enablement) | Allows “prophetic examples” (hypothetical data), potentially leading to overly broad or non-reproducible claims.51 | Requires verifiable experimental data, ensuring the invention is plausible and can be practiced as claimed.51 | The EPO’s standard filters out more speculative or poorly supported patent applications, improving overall patent quality. |

| Medical Method Patenting | Methods of treating patients are generally patentable subject matter.51 | Methods for treatment of the human body by surgery or therapy are excluded from patentability.51 | The EPO’s exclusion removes an entire category of secondary patents commonly used in U.S. thickets. |

The Real-World Consequences

These divergent legal standards are not merely academic; they lead to starkly different outcomes in the real world. The most direct consequence is that far more patents are granted for the same drug in the U.S. than in Europe. For the top-selling drugs in 2021, an analysis found that over four times as many patents were granted in the U.S. compared to Europe.39

The Humira case provides the most dramatic illustration of this divergence. While AbbVie built a U.S. thicket of over 130 granted patents, it held far fewer in Europe. As a direct result, biosimilar competition began in Europe in 2018, while the U.S. had to wait until 2023.1 The tens of billions of dollars in excess healthcare costs paid by Americans during that five-year gap were a direct result of domestic U.S. patent policy.

This demonstrates unequivocally that dense patent thickets are not an inevitable byproduct of pharmaceutical innovation. They are a policy choice. The U.S. system is not the global “gold standard” of patent law it is often portrayed to be; in the pharmaceutical sector, it is a global outlier. This reality has profound implications, suggesting that the high drug prices endemic to the U.S. are not just a market phenomenon but a direct consequence of a domestic legal framework that is out of step with other major developed economies. This provides a powerful, evidence-based argument for reforms aimed at harmonizing U.S. standards with the more rigorous, competition-friendly approach of its international peers.

Section 8: The Role of Intermediaries: Pharmacy Benefit Managers and the Formulary Wall

The barriers that delay affordable generic and biosimilar drugs are not exclusively legal. Even after a lower-cost alternative overcomes a patent thicket in court, it faces a formidable commercial barrier erected by some of the most powerful and least understood players in the U.S. healthcare system: Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). These intermediaries, through their control of insurance formularies and a complex system of rebates, can create a “formulary wall” that is often as effective at blocking competition as a wall of patents.

Introduction to Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

PBMs are third-party companies that act as intermediaries, managing prescription drug benefits on behalf of health insurers, large employers, and government programs like Medicare Part D.54 The market is extraordinarily concentrated. Just three giant PBMs—CVS Caremark, Cigna’s Express Scripts, and UnitedHealth Group’s Optum Rx—control over 80% of the market.25 Their core functions include processing prescription claims, creating networks of retail pharmacies, and, most critically, negotiating with pharmaceutical manufacturers to create drug formularies—the tiered lists of medications covered by a health plan.56

The Rebate System and Formulary Placement

The primary source of a PBM’s power and profitability is the rebate system. PBMs leverage their control over millions of patients to negotiate substantial discounts, or rebates, from brand-name drug manufacturers.56 In exchange for these rebates, the PBM gives the manufacturer’s drug preferential placement on its formulary. This typically means placing the drug on a lower “tier,” which translates to a lower out-of-pocket co-payment for patients and, consequently, a much higher volume of prescriptions.57

This system creates a deeply perverse incentive. Rebates are almost always calculated as a percentage of a drug’s list price (its initial, undiscounted price). This means that a PBM can often earn more revenue from a high-priced brand-name drug that offers a large rebate than from a low-priced generic or biosimilar that offers a small rebate or no rebate at all.56 For example, a 30% rebate on a $1,000 drug yields $300 for the PBM and its client, whereas a 10% rebate on a $200 generic yields only $20. This dynamic gives the PBM a direct financial incentive to favor higher-priced drugs on its formulary.

The “Formulary Thicket”: A Commercial Barrier to Generics

This rebate-driven system allows PBMs to construct a “formulary thicket” or “formulary wall” that blocks competition. When a new, lower-cost generic or biosimilar becomes available, the PBM may choose to exclude it from the formulary entirely or place it on a “non-preferred” tier with prohibitively high patient cost-sharing.25 This decision is often made not on the basis of clinical value—the generic is, by definition, therapeutically equivalent—but to protect the lucrative stream of rebate revenue generated by the incumbent brand-name drug.

This creates a situation where a generic drug can win the legal battle against a patent thicket only to lose the commercial war at the pharmacy counter. If patients cannot get the generic covered by their insurance, or if their co-pay for the generic is higher than for the “preferred” brand, the generic will fail to gain market share. This commercial barrier effectively extends the brand’s monopoly, even in the absence of patent protection. Evidence presented to Congress indicates that PBMs regularly place higher-cost medications in more favorable formulary positions, even when equally safe and effective lower-cost options are available, precisely because of the rebate dynamic.25

Vertical Integration and Market Power

The market power of PBMs is amplified by massive vertical integration. The three largest PBMs are no longer standalone companies; they are integrated parts of healthcare conglomerates that also own major health insurance companies (CVS Caremark is part of Aetna; Express Scripts is part of Cigna; Optum Rx is part of UnitedHealth Group) and, in some cases, the largest pharmacy chains (CVS Pharmacy).25 This consolidation allows them to exert influence at every stage of the pharmaceutical supply chain, steering patients toward the drugs, insurance plans, and pharmacies that maximize profits for the parent corporation.

This reveals a powerful, symbiotic relationship between the legal barriers of patent thickets and the commercial barriers of the PBM rebate system. The patent thicket is what allows the brand-name drug’s price to remain artificially high for an extended period. This high list price, in turn, is what makes it possible for the manufacturer to offer the large rebate that the PBM finds so attractive. The large rebate then incentivizes the PBM to grant the brand drug preferential formulary placement, protecting it from competition from lower-cost generics. It is a mutually reinforcing loop: the patent thicket creates the financial conditions for the PBM rebate system to operate, and the PBM system provides a powerful commercial defense that reinforces the monopoly created by the patent thicket. They are two sides of the same anticompetitive coin. This synergy means that any policy solution that addresses only patent law without also reforming the opaque and incentive-driven PBM market is likely to be incomplete and ultimately ineffective at restoring true competition and lowering drug prices.

Section 9: Pathways to Reform: Legislative, Regulatory, and Antitrust Solutions

The growing recognition of patent thickets as a primary driver of high prescription drug costs has spurred a multifaceted response from policymakers, regulators, and legal experts. Proposed solutions aim to dismantle the current system from several angles: reforming the litigation process to reduce the power of attrition, strengthening patent quality at the source to prevent weak patents from issuing, and applying antitrust law to challenge these strategies as anticompetitive behavior.

Legislative Reforms

Congress has become a key battleground for patent reform, with several bipartisan bills introduced to address the loopholes that enable thicket strategies.

- The ETHIC Act (Eliminating Thickets to Improve Competition): This is one of the most prominent and targeted legislative proposals. Introduced by a bipartisan group of lawmakers in both the House and Senate, the ETHIC Act aims directly at the core litigation strategy of the patent thicket.59 Its central provision would limit a brand-name pharmaceutical company to asserting only

one patent from a family of “terminally disclaimed” patents in litigation against a single generic or biosimilar challenger.59 As previously detailed, terminal disclaimers are used to obtain numerous, legally duplicative patents. By restricting the brand to defending the single best patent from each inventive group, the bill seeks to prevent the “war of attrition” strategy, where challengers are overwhelmed by the sheer volume of lawsuits. This would streamline litigation, reduce costs for generic competitors, and focus legal disputes on the merits of the core invention rather than the challenger’s financial endurance.9 - Other Legislative Proposals: Beyond the ETHIC Act, a suite of other reforms has been proposed to tackle different aspects of the problem. These include bills aimed at increasing the transparency of patent ownership and listings, particularly for biologics; raising the statutory standards for patentability to make it more difficult to obtain secondary patents on minor modifications; and creating new mechanisms to address “product hopping” by making it more difficult for brands to switch markets to new formulations just before patent expiry.17 The overarching goal of these legislative efforts is to rebalance the patent system to reward genuine, significant innovation while ensuring that the pathway to fair market competition remains open and viable.9

Regulatory and Administrative Reforms

In parallel with legislative action, there is a strong push for administrative reforms within the federal agencies that oversee the patent and drug approval systems.

- Enhanced USPTO-FDA Collaboration: Recognizing the disconnect between their missions, the USPTO and FDA have launched initiatives to improve collaboration and data sharing.12 The goal is to provide USPTO patent examiners with better information from the FDA regarding a drug’s clinical context. This could help examiners more effectively assess whether a claimed “invention” in a secondary patent application (e.g., a new formulation or dosage) is truly “non-obvious” or if it represents a trivial modification with no meaningful clinical benefit. By bridging this information gap, the agencies hope to prevent the issuance of low-quality patents that are later used to block competition.12

- Strengthening Patent Quality at the USPTO: Many critics and reformers argue that the most fundamental solution is to improve patent quality at the source. This involves calls for the USPTO to administratively tighten its own examination guidelines to prevent weak, non-inventive patents from being granted in the first place.1 Specifically, advocates urge the USPTO to adopt stricter interpretations of novelty and non-obviousness that align more closely with the more rigorous standards of the European Patent Office (EPO). This would involve raising the bar for what constitutes a patentable invention, thereby making it much more difficult to build a thicket out of dozens of marginal patents.51

Antitrust Enforcement

A third avenue of reform involves leveraging antitrust law to challenge patent thickets as an illegal form of anticompetitive conduct.

- Scrutiny from the FTC and DOJ: The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have signaled increasing interest in treating the strategic accumulation of patents not as legitimate legal activity, but as a potential violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act’s prohibition on illegal monopolization.63 The FTC’s recent challenges to improper Orange Book listings and its ongoing investigations into “pay-for-delay” settlements—where brand companies pay generics to abandon their patent challenges and stay off the market—are part of this broader enforcement push.7

- Landmark Litigation: The In re Humira antitrust case was a watershed moment, representing the first major attempt to apply antitrust law directly to a patent thicket.6 While the lawsuit was ultimately unsuccessful at the district and appellate levels, it established a legal theory that could be refined in future cases. The primary hurdle for such lawsuits is the

Noerr-Pennington doctrine, which provides broad immunity from antitrust liability for the act of petitioning the government, which includes filing patents and lawsuits.41 Future cases will likely focus on arguing that amassing a thicket of weak or duplicative patents with the sole intent of blocking competition falls under the “sham” exception to this doctrine.

However, these varied approaches to reform highlight a significant challenge: the risk of playing policy “whack-a-mole.” The patent thicket is not a single tactic but a complex, interconnected system of legal and commercial strategies. A reform that successfully targets only one component of this system may simply incentivize companies to shift their resources and ingenuity to another. For example, if litigation is streamlined by the ETHIC Act, companies might respond by filing even more patents earlier in the drug’s lifecycle or by relying more heavily on PBM rebates and formulary walls to block competition. This suggests that a truly effective solution cannot be a single piece of legislation or a single agency action. It requires a coordinated, holistic approach that simultaneously reforms patent granting standards at the USPTO, closes litigation loopholes through acts of Congress, empowers vigorous antitrust enforcement by the FTC and DOJ, and addresses the perverse financial incentives within the PBM market. Without such a comprehensive strategy, policymakers risk closing one door only to find that another has been opened, leaving the core problem of delayed competition and high drug prices intact.

Section 10: Conclusion and Recommendations

The analysis presented in this report leads to an unequivocal conclusion: pharmaceutical patent thickets are not an accidental feature of the U.S. intellectual property landscape but a deliberate and highly refined strategy of monopoly extension. They are the logical outcome of a system where permissive patent granting standards, unique litigation rules, and opaque commercial arrangements have created powerful incentives to prioritize the legal defense of existing blockbusters over the scientific pursuit of new ones. This system has proven to be enormously costly to the American public, has distorted the very nature of pharmaceutical innovation, and has created a stark and unfavorable divergence between healthcare outcomes in the United States and those in other developed nations. The fundamental bargain of the patent system—a temporary monopoly in exchange for innovation and eventual public access—has been compromised.

Restoring balance to this system requires a comprehensive and multi-layered approach that addresses the problem at its roots. Piecemeal solutions, while potentially helpful, risk being circumvented. A coordinated effort across all branches of government is necessary to recalibrate the system so that it rewards genuine, breakthrough discoveries without enabling the indefinite suppression of the competition that is essential for an affordable and equitable healthcare system.

Multi-Layered Recommendations

For the U.S. Congress:

- Enact Targeted Litigation Reform: Congress should pass legislation modeled on the Eliminating Thickets to Improve Competition (ETHIC) Act. By limiting brand-name companies to asserting a single patent from a family of duplicative, terminally disclaimed patents, this reform would directly neutralize the “war of attrition” litigation strategy that makes challenging thickets financially prohibitive.59 This is a critical first step to ensure legal disputes are decided on merit, not financial might.

- Strengthen Statutory Patentability Standards: Congress should amend the Patent Act to introduce a higher standard for secondary patents. For example, legislation could require that patents claiming new formulations, dosages, or methods of use for an existing drug demonstrate a significant, evidence-based clinical benefit over existing therapeutic options. This would shift the focus from patenting trivial modifications to rewarding meaningful improvements in patient care.

- Mandate PBM and Price Transparency Reform: The symbiotic relationship between patent thickets and the rebate system must be broken. Congress should enact comprehensive PBM reform that, at a minimum, bans spread pricing and mandates that PBM compensation be delinked from a drug’s list price, moving instead to a flat, transparent fee-for-service model.54 This would remove the perverse incentive for PBMs to favor high-cost, high-rebate brand drugs over lower-cost generics and biosimilars on their formularies.

For the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) & Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

- Deepen and Mandate Agency Collaboration: The ongoing collaboration between the USPTO and FDA should be formalized and expanded.12 The USPTO should be required to consider FDA data on clinical efficacy and therapeutic equivalence when examining secondary patent applications. This would equip examiners with the necessary context to reject patents on modifications that offer no real-world advantage to patients.

- Harmonize USPTO Standards with International Best Practices: The USPTO should undertake a comprehensive review of its examination guidelines with the express goal of aligning them with the stricter standards of the European Patent Office (EPO).51 This should include adopting a more rigorous “inventive step” analysis, a stricter prohibition on “double patenting” without reliance on terminal disclaimers, and more stringent data requirements to prove enablement. Raising the quality bar at the source is the most effective long-term strategy to prevent the formation of thickets.

For Antitrust Agencies (FTC & DOJ):

- Pursue Aggressive and Precedent-Setting Enforcement: The FTC and DOJ should continue to aggressively investigate patent thickets as a potential violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits illegal monopolization.63 While early cases have faced headwinds, the agencies should continue to develop and refine the legal theory that amassing a thicket of weak, overlapping, or duplicative patents for the primary purpose of deterring competition constitutes an anticompetitive act.

- Scrutinize Litigation Settlements: Antitrust agencies must continue their rigorous scrutiny of settlements that arise from patent thicket litigation. These settlements often contain anticompetitive terms, such as “pay-for-delay” provisions or volume-limited market entry for the generic, which serve to share monopoly profits between the brand and the challenger at the expense of the consumer.7

Ultimately, the challenge of the patent thicket is a challenge to the integrity of the innovation ecosystem itself. The goal of reform is not to weaken patents or diminish the rewards for groundbreaking research. Rather, it is to restore the patent system’s intended purpose: to act as a temporary catalyst for discovery, not a permanent barrier to access. By implementing these coordinated reforms, the United States can begin to untangle the dense web of patents that currently stands between millions of Americans and the affordable, life-saving medicines they need, ensuring that the system fosters both the innovation we need and the competition we deserve.

Works cited

- The Global Patent Thicket: A Comparative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Monopoly Strategies in the U.S., Europe, and Emerging Markets – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-do-patent-thickets-vary-across-different-countries/

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- The Economics of Drug Discovery and the Impact of Patents – R Street Institute, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-economics-of-drug-discovery-and-the-impact-of-patents/

- Does Pharma Need Patents? – The Yale Law Journal, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/feature/does-pharma-need-patents

- www.drugpatentwatch.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-do-patent-thickets-vary-across-different-countries/#:~:text=Defining%20the%20Drug%20Patent%20Thicket,to%20actually%20commercialize%20new%20technology%E2%80%9D.

- Patent thicket – Wikipedia, accessed August 6, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_thicket

- Patent Evergreening In The Pharmaceutical Industry: Legal Loophole Or Strategic Innovation? – IJLSSS, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ijlsss.com/patent-evergreening-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-legal-loophole-or-strategic-innovation/

- Untangling Patent Thickets: The Hidden Barriers Stifling Innovation – TT CONSULTANTS, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/untangling-patent-thickets-the-hidden-barriers-stifling-innovation/

- BILL TO ADDRESS PATENT THICKETS, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.welch.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Welch.Braun_.Klobuchar-Patent-bill.pdf

- Potential Abuses Within U.S. Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation – The Actuary Magazine, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/potential-abuses-within-u-s-pharmaceutical-patent-regulation/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- USPTO – FDA Collaboration Initiatives, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration

- The Dark Reality of Drug Patent Thickets: Innovation or Exploitation? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dark-reality-of-drug-patent-thickets-innovation-or-exploitation/

- Addressing Patent Thickets To Improve Competition and Lower Prescription Drug Prices – I-MAK, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Addressing-Patent-Thickets-Blueprint_2023.pdf

- The Impact of Generic Drugs on Healthcare Costs …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-generic-drugs-on-healthcare-costs/

- Patent Database Exposes Pharma’s Pricey “Evergreen” Strategy – UC Law San Francisco, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.uclawsf.edu/2020/09/24/patent-drug-database/

- THEY SAID IT! CONSUMER ADVOCATES AND EXPERTS SHINE A …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/they-said-it-consumer-advocates-and-experts-shine-a-light-on-big-pharmas-egregious-anti-competitive-tactics-that-extend-monopolies-and-keep-drug-prices-high/

- Drug Pricing and Pharmaceutical Patenting Practices …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R46221.html

- Patent thickets and their impact on plan spend – Marsh McLennan Agency, accessed August 6, 2025, https://mmaeast.com/blog/patent-thickets-plan-spend/

- Fact Check: Debunking Myths About Patents in the Pharmaceutical Industry, accessed August 6, 2025, https://c4ip.org/fact-check-debunking-myths-about-patents-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry/

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an American problem – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9439849/

- An Interview with Rachel Goode, Ph.D, about Biological Patent Thickets | JD Supra, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/an-interview-with-rachel-goode-ph-d-5763996/

- Patent thickets are pricing Americans out of medicine – FREOPP, accessed August 6, 2025, https://freopp.org/oppblog/patent-thickets-are-pricing-americans-out-of-medicine/

- Bad Patents Keep Drug Prices High – R Street Institute, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/bad-patents-keep-drug-prices-high/

- The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers in Prescription Drug Markets – House Oversight Committee, accessed August 6, 2025, https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PBM-Report-FINAL-with-Redactions.pdf

- Congressional Investigation of RevAssist-Linked and General Pricing Strategies for Lenalidomide | JCO Oncology Practice – ASCO Publications, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP.23.00579

- Humira – I-MAK, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/i-mak.humira.report.3.final-REVISED-2020-10-06.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Patents and Economic Inequality – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10733756/

- Pharmaceutical Patents and Economic Inequality – Health and Human Rights Journal, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.hhrjournal.org/2023/12/06/pharmaceutical-patents-and-economic-inequality/

- The Patent Playbook Your Lawyers Won’t Write: Patent strategy development framework for pharmaceutical companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-playbook-your-lawyers-wont-write-patent-strategy-development-framework-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- C4IP Slams ETHIC Act Targeting Patent Thickets as Destabilizing to Innovation Ecosystem, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/08/05/c4ip-slams-ethic-act-targeting-patent-thickets-destabilizing-innovation/id=190934/

- Are ‘Patent Thickets’ Smothering Innovation? – Yale Insights, accessed August 6, 2025, https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/are-patent-thickets-smothering-innovation

- Why Pharmaceutical Patent Thickets Are Unique – Rutgers University, accessed August 6, 2025, https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=01RUT_INST&filePid=13778612650004646&download=true

- Arrington Leads Bipartisan Effort to Address Patent Thickets and Increase Competition in the Prescription Drug Market, accessed August 6, 2025, https://arrington.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=1174

- Patent Thickets: A Barrier to Innovation? – Number Analytics, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/patent-thickets-barrier-to-innovation

- (PDF) Patent Thickets, Defensive Patenting, and Induced R&D: An Empirical Analysis of the Costs and Potential Benefits of Fragmentation in Patent Ownership * – ResearchGate, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299484433_Patent_Thickets_Defensive_Patenting_and_Induced_RD_An_Empirical_Analysis_of_the_Costs_and_Potential_Benefits_of_Fragmentation_in_Patent_Ownership

- To Promote Innovation – Supreme Court, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/URLs_Cited/OT2005/05-130/05-130.pdf

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets, accessed August 6, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- Statement of Tahir Amin Senate HELP Committtee Final 6 Feb, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.help.senate.gov/download/02/08/2024/statement-of-tahir-amin-senate-help-committtee-final-8-feb

- In the case of brand name drugs versus generics, patents can be bad medicine, WVU law professor says, accessed August 6, 2025, https://wvutoday.wvu.edu/stories/2022/12/19/in-the-case-of-brand-name-drugs-vs-generics-patents-can-be-bad-medicine-wvu-law-professor-says

- In the Thick(et) of It: Addressing Biologic Patent Thickets Using the Sham Exception to Noerr-Pennington, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol33/iss3/5/

- Keytruda’s Patent Wall – I-MAK, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/i-mak.keytruda.report-2021-05-06F.pdf

- Keytruda’s Patent Wall – I-MAK, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/keytruda/

- BIG PHARMA WATCH: MERCK EXPEDITES ANTI-COMPETITIVE STRATEGY ON BLOCKBUSTER CANCER DRUG – CSRxP.org, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/big-pharma-watch-merck-expedites-anti-competitive-strategy-on-blockbuster-cancer-drug/

- Congressional Investigation of RevAssist-Linked and General Pricing Strategies for Lenalidomide – ASCO Publications, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ascopubs.org/doi/pdf/10.1200/OP.23.00579

- How Celgene and Bristol Myers Squibb Used Volume Restrictions to Delay Revlimid Competition – I-MAK, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/2025/04/04/how-celgene-and-bristol-myers-squibb-used-volume-restrictions-to-delay-revlimid-competition/

- Congressional Investigation of RevAssist-Linked and General …, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/OP.23.00579

- Overpatented 2025 – I-MAK, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/overpatented/

- (2024-08-07) Research on Medicare Negotiation Targets Patent Abuses (FINAL).docx – Accountable US, accessed August 6, 2025, https://accountable.us/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2024-08-07-Research-on-Medicare-Negotiation-Targets-Patent-Abuses-FINAL.docx.pdf

- Bipartisan Package to Curb Pharmaceutical Industry Abuses and Lower Drug Prices Wins Senate Judiciary Committee Approval – Public Interest Patent Law Institute, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.piplius.org/news/bipartisan-package-to-curb-pharmaceutical-industry-abuses-and-lower-drug-prices-wins-senate-judiciary-committee-approval