Section I: The Strategic Imperative of Drug Repositioning

1.1 Beyond Serendipity: The Evolution from Accidental Discovery to Deliberate Strategy

Drug repositioning, also referred to as drug repurposing or reprofiling, is the strategic investigation of existing drugs for new therapeutic purposes.1 Although the term was formally coined in 2004 by Ashburn and Thor, the practice of finding new uses for old drugs has a long and storied history.3 The earliest successes were largely serendipitous, arising from astute clinical observations of unexpected side effects or off-target activities. Landmark examples include the repurposing of sildenafil, initially studied for angina, to treat erectile dysfunction, and the resurrection of thalidomide, a drug withdrawn for its teratogenic effects, as a treatment for complications of leprosy and multiple myeloma.5 These historical cases, while transformative, were products of chance rather than systematic design.8

The modern paradigm represents a fundamental shift from this reactive, serendipitous model to a proactive, deliberate strategy. This evolution is propelled by significant advances in genomics, network biology, and chemoproteomics, which provide a deeper understanding of the molecular underpinnings of disease.1 The advent of powerful computational tools, big data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI) has transformed repositioning into a rational, data-driven process that allows for the systematic and exhaustive exploration of new therapeutic opportunities.7 This modern philosophy is aptly captured by the words of Nobel laureate pharmacologist James Black: “The most fruitful basis for the discovery of a new drug is to start with an old drug”.4

1.2 Countering Eroom’s Law: The Economic and Clinical Rationale for Repurposing

The strategic importance of drug repositioning is best understood in the context of the pharmaceutical industry’s escalating R&D productivity crisis. Since the mid-1990s, despite exponential increases in research and development spending, the number of new drugs approved per billion US dollars invested has steadily declined—a trend famously dubbed Eroom’s Law (Moore’s Law in reverse).12 The traditional

de novo drug discovery process is an arduous, high-risk endeavor. It takes an average of 10 to 17 years and costs an estimated $2.6 billion to bring a single new chemical entity (NCE) to market, a figure that accounts for the high cost of failures.14 With clinical attrition rates exceeding 90%, the traditional pipeline is both economically unsustainable and slow to address pressing medical needs.4

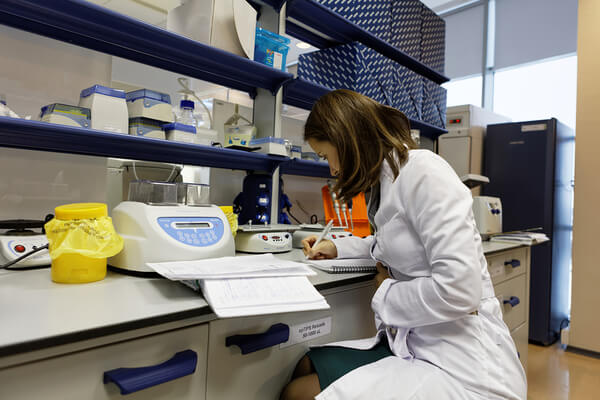

Drug repositioning offers a compelling strategic solution to this challenge. By starting with compounds that have already undergone extensive preclinical and often early-stage clinical testing, the process inherently leverages de-risked assets.2 These drugs have established safety, toxicology, pharmacokinetic, and formulation data, which allows developers to bypass the most failure-prone early stages of discovery.23 This strategy is particularly vital for addressing unmet medical needs in areas that are often not commercially attractive for the high-risk investment of

de novo R&D, such as rare, orphan, and neglected diseases.1

The high attrition rate of traditional drug discovery, often seen as a liability, thus becomes a primary source of repositioning candidates. The so-called “valley of death,” where promising compounds are abandoned for reasons like lack of efficacy in a specific indication or strategic portfolio changes, is not a graveyard but a rich reservoir of de-risked assets.20 A compound that fails to show superiority for hypertension but has a well-documented safety profile is an ideal candidate for screening against other diseases. This reframes the enormous sunk costs of R&D failures into a strategic library of opportunities, making repositioning a critical hedge against the systemic risks of the pharmaceutical industry. Facing pressures from patent cliffs on blockbuster drugs and declining productivity, repositioning has evolved from an opportunistic tactic into an essential component of portfolio and lifecycle management.29

1.3 The Repositioning Advantage by the Numbers: A Comparative Analysis

The strategic and economic benefits of drug repositioning are quantifiable and substantial when compared to the de novo discovery pathway.

- Accelerated Timelines: The development timeline for a repurposed drug is typically 3 to 12 years, a significant acceleration compared to the 10 to 17 years required for a new drug.17 This can save an average of 6 to 7 years, primarily by eliminating or shortening the preclinical and Phase I safety trial stages.20

- Reduced Costs: The average cost to bring a repurposed drug to market is approximately $300 million.17 This represents a potential cost saving of over 85% compared to the $2.6 billion average for an NCE.15

- Higher Success Rates: The probability of a repurposed drug gaining market approval is reported to be around 30%, a threefold increase over the approximately 10% success rate for new drug applications.20 This improved success rate is largely attributable to the pre-existing safety data, as safety concerns account for roughly 30% of all failures in clinical trials.23 It is important to note, however, that while safety risks are mitigated, demonstrating efficacy in the new indication remains a significant hurdle where failure rates can still be high.20

- Significant Market Impact: Repurposed products are not a niche category; they are a major contributor to the pharmaceutical market. Various analyses indicate that 30% to 40% of all new drugs and biologics approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are repurposed products.20 Notably, a study found that 35% of “transformative” drugs—those with groundbreaking effects on patient care—were repurposed products, underscoring their clinical importance.1

| Metric | De Novo Discovery | Drug Repositioning | Source(s) |

| Average Development Time | 10–17 years | 3–12 years | 4 |

| Average Development Cost | ~$2.6 billion (incl. failures) | ~$300 million | 15 |

| Probability of Success | ~10% | ~30% | 20 |

| Key Failure Point | Efficacy & Safety | Efficacy | 20 |

| Primary Advantage | Novelty (Composition of Matter IP) | Reduced Risk, Time, & Cost | 5 |

Table 1: De Novo Discovery vs. Drug Repositioning: A Comparative Snapshot

Section II: A Framework for Opportunity: Methodologies and Approaches

The identification and validation of new uses for existing drugs have evolved into a multi-pronged discipline, integrating strategic frameworks with advanced computational and experimental tools. This systematic approach allows for a comprehensive exploration of the therapeutic potential hidden within the existing pharmacopoeia.

2.1 The Three Pillars: Strategic Frameworks

Three primary strategic frameworks guide the search for repositioning candidates, each starting from a different point of the drug-target-disease triad.

- Drug-Centric Approach: This strategy begins with a specific drug—often one that is nearing patent expiry, was abandoned for non-safety reasons, or has shown interesting off-label effects—and systematically screens it for new therapeutic indications.37

- Disease-Centric Approach: This is the most common framework, accounting for over 60% of repositioning projects.10 It starts with an unmet medical need, such as a rare disease with no approved treatment, and screens a library of existing compounds to find one with potential efficacy against that disease’s pathology.10

- Target-Centric Approach: This knowledge-driven approach links a disease to a specific, druggable molecular target (e.g., a receptor or enzyme). The search then focuses on identifying existing drugs known to modulate that target.5 This can be further divided into “on-target” repositioning, where the drug’s known mechanism of action is applied to a new disease sharing the same pathway, and “off-target” repositioning, where a drug’s previously unknown interaction with a different target provides the new therapeutic effect.5

2.2 The Computational Toolkit: Leveraging AI, Network Biology, and In Silico Screening

Computational, or in silico, methods are the engine of modern drug repositioning. They enable the rapid, cost-effective analysis of massive and complex biological datasets to generate and prioritize testable hypotheses, significantly reducing the scope of expensive and time-consuming wet-lab experimentation.1

- Network-Based Methods: These approaches construct and analyze complex biological networks to map the relationships between drugs, protein targets, genes, and diseases.2 By applying principles like “guilt-by-association,” these models can infer novel drug-disease connections.40 Advanced techniques include building sophisticated knowledge graphs that capture the polarity and effect of relationships (e.g., Protein A

negatively regulates Disease X) and employing graph neural networks (GNNs) to predict drug-target interactions across these vast data structures.2 - Signature-Based Methods: This technique relies on comparing the gene expression “signature” of a disease state with a library of signatures produced by various drugs. The goal is to identify drugs that induce a transcriptional profile opposite to that of the disease, suggesting they could reverse the disease pathology.20 Databases such as the Connectivity Map (CMap) are central to this approach.

- Molecular Docking: This is a structure-based computational technique that simulates the physical interaction between a drug molecule and the three-dimensional structure of a protein target. It allows for the virtual screening of thousands or even millions of compounds against a disease-relevant target to predict which ones are most likely to bind and modulate its function.20

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): AI and ML algorithms are increasingly used to integrate and analyze highly diverse datasets, including chemical structures, bioactivity data, clinical side effects, and genomic information. By applying techniques such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forests, and deep learning, these models can identify subtle, complex patterns that are not apparent to human researchers, thereby predicting novel drug-indication pairs with greater accuracy.5

2.3 The Experimental Engine: From High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening to Target-Based Assays

While computational methods generate hypotheses, experimental validation is essential to confirm them. Modern experimental approaches are designed for speed, relevance, and scale.

- Phenotypic Screening: In contrast to target-based methods, phenotypic screening is a “target-agnostic” approach. It involves testing compounds in a biologically relevant system—such as a cell culture, organoid, or whole organism model of a disease—and identifying those that produce a desired phenotypic change (e.g., killing cancer cells while sparing healthy ones).9 This method does not require prior knowledge of the drug’s molecular target and has been particularly successful in discovering first-in-class drugs with novel mechanisms of action.44

- Target-Based Assays: These assays are designed to screen compounds against a specific, pre-validated molecular target known to be critical to a disease pathway. While this approach provides clear mechanistic insight, its scope is limited to the universe of known and validated targets.46

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): HTS leverages automation, robotics, and miniaturization to conduct thousands or millions of biochemical or cell-based tests in a short period. It is the underlying technology that enables both phenotypic and target-based screening to be performed at the scale of large compound libraries.20

A powerful synergy exists in modern repositioning workflows that combine these approaches. Target-agnostic methods like phenotypic screening or real-world data mining can identify a promising link between a compound and a disease phenotype. This discovery then triggers focused, target-based computational and experimental work to deconvolve the underlying mechanism of action (MOA). This integrated process, moving from a functional observation to a mechanistic understanding, yields discoveries that are not only more robust but also more readily patentable and optimizable.44

2.4 The Real-World Lens: Mining Clinical Observations and Electronic Health Records

The final source of repositioning opportunities comes from observing drug effects in the real world, a process that has also evolved from serendipity to systematic analysis.

- Clinical Observation: The historical bedrock of repositioning, this involves recognizing unexpected therapeutic benefits during clinical trials or post-marketing surveillance.5 The discovery of sildenafil’s efficacy for erectile dysfunction is the canonical example, identified through side effects reported in trials for angina.3

- Systematic Analysis of Real-World Data (RWD): Today, this process is systematized through the large-scale mining of observational data from sources like Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and insurance claims databases.1 By applying advanced statistical and causal inference methods, researchers can analyze the health outcomes of millions of patients to identify statistically significant associations between the use of a particular drug and a reduced incidence or progression of a different disease.39 This approach can effectively emulate hundreds of randomized trials, providing a powerful engine for both generating and validating repurposing hypotheses on a population scale.51

This evolution also changes the perception of a drug’s fundamental properties. Historically, a drug’s off-target effects, or its interaction with multiple biological targets (polypharmacology), were viewed primarily as a source of undesirable side effects. Modern repositioning reframes this molecular promiscuity as a key strategic asset.5 The fact that most drugs are not perfectly selective “magic bullets” but rather interact with a network of targets means they harbor a vast landscape of unexplored therapeutic potential. The goal of systematic repositioning is to map and exploit these off-target interactions, turning a historical liability into a rich source of innovation.24

Section III: The Intellectual Property Arsenal: Forging a Competitive Moat

For any drug repositioning project to be commercially viable, a robust and defensible intellectual property (IP) strategy is not just an ancillary legal step but a core component of the business model. While the clinical and scientific hurdles are significant, the greatest challenge often lies in creating a period of market exclusivity sufficient to recoup the substantial investment required for late-stage clinical trials and commercialization.

3.1 The Patentability Puzzle: Overcoming Novelty and Non-Obviousness Hurdles

The central IP challenge in drug repositioning is that the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is, by definition, already known. This immediately precludes the strongest form of protection: a new composition-of-matter patent on the drug itself, as the compound lacks novelty.27 Any new patent must therefore be based on a novel and non-obvious aspect of the drug’s new application.54

- Novelty: The new use, formulation, or dosage must not have been previously disclosed in the prior art, which includes scientific literature, previous patents, and public use.55

- Non-Obviousness: This is typically the highest barrier to overcome. The new use must not be an obvious extension of existing knowledge to a “person having ordinary skill in the art”.55 A patent examiner might argue, for instance, that using a known anti-inflammatory drug to treat another inflammatory condition was obvious. The most powerful way to rebut an obviousness rejection is by demonstrating “unexpected results”.55 This requires robust data showing that the drug worked surprisingly well, was effective at an unexpectedly low dose, or exhibited a synergistic effect when combined with another agent—outcomes that could not have been reasonably predicted from the prior art.

3.2 Beyond the Composition of Matter: Mastering Secondary Patents

Since the drug itself cannot be patented, the IP strategy must focus on securing “secondary patents” that protect specific aspects of the new application.

- Method-of-Use (or Method-of-Treatment) Patents: This is the foundational IP tool for drug repositioning. The patent claims protect the specific method of using the known drug to treat the newly discovered indication.5 For example, “A method of treating multiple myeloma, comprising administering a therapeutically effective amount of thalidomide.” While essential, these patents are considered weaker than composition-of-matter patents because they can be vulnerable to off-label prescribing and generic competition via “skinny labels”.1 Nonetheless, they can create exclusive markets and provide critical leverage in licensing and enforcement.56

- Formulation Patents: A highly effective strategy is to develop and patent a new formulation of the drug tailored to the new indication. This could be an extended-release version, a topical gel, a nasal spray, or a long-acting injectable.28 A new formulation creates a physically distinct product that a generic manufacturer cannot easily copy or substitute, providing a much stronger barrier to competition than a method-of-use patent alone.27

- Dosage and Regimen Patents: If the new indication requires a specific dosage or a novel dosing schedule that differs from the original use, this new regimen can be patented.54 This adds another layer of protection that can be difficult for competitors to design around without inducing infringement.

- Combination Patents: Patenting a new fixed-dose combination of the repurposed drug with one or more other APIs is a powerful strategy. This creates a novel therapeutic product with its own unique clinical profile and strong IP protection.28

3.3 Building a Defensible Portfolio: Integrating IP with R&D

A successful IP strategy requires that R&D and legal teams work in concert from the very beginning of a repositioning project. The goal is to build a multi-layered patent portfolio, or “patent thicket,” that creates a formidable competitive moat.

The R&D program should be explicitly designed to generate data that supports these secondary patent claims. For instance, instead of only testing the original oral tablet, the development plan should include exploring new formulations or testing the drug in combination with other agents specifically to create patentable inventions.55 Early and strategic patent filing is crucial to establish priority before research findings are publicly disclosed.57

This integrated approach is critical to overcoming the primary commercial threat to repurposed drugs: the “skinny label.” This is a tactic where a generic manufacturer launches a copy of an off-patent drug but omits the still-patented indication from its product label and prescribing information.1 Because pharmacists can often substitute generics for branded drugs, the innovator who spent hundreds of millions developing the new indication can see their market rapidly eroded by off-label use of the cheaper generic. This commercial reality underscores why the clinical success of a repurposed drug is inextricably linked to the strength of its IP. A project that relies solely on a method-of-use patent is at high risk. In contrast, a project that results in a new, patented formulation creates a distinct product that cannot be automatically substituted, ensuring the innovator can capture the value of their investment. This transforms the R&D path from a purely scientific exercise into a critical IP strategy decision. The practice of filing these secondary patents, sometimes pejoratively called “evergreening,” is not merely a defensive tactic to extend a blockbuster’s patent life; for off-patent repurposed drugs, it is the foundational and necessary offensive strategy that makes the entire enterprise commercially viable in the first place.54 Without the prospect of securing new, defensible patents, the financial incentive to fund the required clinical trials for a new indication evaporates.1

| Patent Type | Description | Key Challenge to Obtain | Strength of Protection vs. Generics | Strategic Application/Example |

| Method-of-Use | Protects the use of a known drug for a new disease. | Non-obviousness; demonstrating the new use was not predictable. | Weak: Vulnerable to “skinny labels” and off-label prescribing. | Foundational patent for any repurposed drug; e.g., patenting the use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular events. |

| New Formulation | Protects a novel delivery system (e.g., extended-release, topical, injectable). | Novelty and non-obviousness of the formulation itself. | Strong: Creates a physically distinct product that cannot be automatically substituted by a generic of the original form. | Repurposing an oral drug as a transdermal patch for a new indication, improving patient compliance and creating a new product. |

| New Dosage/Regimen | Protects a specific dose or dosing schedule required for the new indication. | Demonstrating the new regimen is novel and critical for efficacy/safety. | Moderate: Can deter direct copying, but may still be susceptible to off-label use with different dosing. | Discovering that a much lower dose of a drug is effective for a new indication, with a better safety profile. |

| Combination Therapy | Protects a fixed-dose combination of the repurposed drug with another API. | Demonstrating synergistic or additive effects that are non-obvious. | Strong: Creates a new chemical entity (in practice) with a unique clinical profile and strong patent protection. | Combining an old chemotherapy agent with a repurposed drug that overcomes resistance, creating a new standard of care. |

Table 2: Intellectual Property Strategies for Repurposed Drugs

Section IV: From Patent Filings to Market Intelligence: A Guide to Competitive Analysis

In the competitive landscape of the pharmaceutical industry, patent data is more than a legal record; it is a powerful source of strategic intelligence. For drug repositioning, where the field of play is defined by existing compounds and evolving science, the ability to systematically mine and interpret this data provides a significant competitive advantage.

4.1 Decoding the Landscape: Using Patent Databases as a Strategic Map

Patent applications represent the earliest public signals of a company’s research and development intentions, often filed years before a program is disclosed in clinical trial registries or scientific publications. A sophisticated competitive intelligence program must therefore be patent-centric, treating patent databases as a leading indicator of corporate strategy.59 By systematically tracking a competitor’s filings for method-of-use, formulation, and combination patents, an organization can:

- Identify emerging interest in new therapeutic areas.

- Uncover the specific molecular targets or pathways they are pursuing.

- Anticipate future repositioning strategies long before they become public knowledge.

The true power of this intelligence, however, comes not from a single data source but from its integration. A patent filing from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), when linked to a trial registration on ClinicalTrials.gov, cross-referenced with compound and target data from PubChem or DrugBank, and analyzed within a comprehensive commercial platform, transforms disparate data points into a coherent picture of a competitor’s strategy, funding, and timeline.61

4.2 Leveraging Commercial Platforms for Actionable Intelligence

While public databases provide the raw data, commercial intelligence platforms are essential for aggregating, structuring, and analyzing this information efficiently. These platforms integrate patent, clinical, regulatory, and commercial data into a single, searchable interface, providing tools to turn data into actionable insights.

- DrugPatentWatch: This platform specializes in providing integrated global intelligence on drug patents, regulatory status, and litigation.59 Its services are critical for:

- Forecasting Generic Entry: By tracking patent expirations and Paragraph IV challenges, companies can precisely predict when a branded drug will face generic competition. This identifies a window of opportunity to launch a repurposed version or informs the lifecycle management of an existing asset.59

- Assessing IP Risk: Its tools for conducting prior art searches are invaluable for evaluating the patentability of an internal repositioning candidate or assessing the strength of a competitor’s IP portfolio around a potential target.60

- Clarivate Cortellis: This is a comprehensive intelligence solution covering the entire drug development lifecycle, from early discovery to post-market analysis.62 For repositioning, Cortellis enables users to:

- Map the Competitive Pipeline: With data on over 100,000 pipeline drugs and 6 million patents, it allows for a complete analysis of a therapeutic area, identifying all players and their stages of development.63

- Benchmark and Prioritize: Users can compare the preclinical and clinical performance of their drug candidates against competitors, access drug sales forecasts, and use AI-based tools to predict probabilities of success, enabling data-driven go/no-go decisions on repositioning projects.62

4.3 Identifying White Space and In-Licensing Opportunities

A proactive patent analysis strategy can reveal both threats and opportunities.

- Identifying “White Space”: By mapping the patent landscape for a particular disease, target, or technology, a company can identify areas with minimal or no existing IP protection. This “white space” represents a strategic opportunity to develop a repurposed drug with a strong freedom-to-operate position and a higher likelihood of securing broad and defensible patents.64

- Scouting for In-Licensing Opportunities: A significant portion of promising drug candidates are abandoned by large pharmaceutical companies not because of safety issues, but for strategic reasons such as a shift in therapeutic focus or portfolio consolidation.20 These “shelved assets” represent a trove of de-risked, high-value opportunities for other companies. Systematically monitoring patent filings and clinical trial discontinuations can uncover these assets, creating opportunities for in-licensing or acquisition, often at a favorable valuation.20

4.4 Case Study: Deconstructing a Competitor’s Repositioning Strategy Through Patent Analysis

Consider a hypothetical scenario: a competitive intelligence team at “Company B” is monitoring “Company A,” a leader in cardiovascular medicine. The team’s patent watch alerts them to a new method-of-use patent application from Company A, claiming the use of their established cardiovascular drug, “CardiaCure,” for treating diabetic nephropathy. This is the first signal of a strategic pivot.

Six months later, a second patent application from Company A is published. This one claims a new extended-release formulation of CardiaCure at a lower dose than is used for its cardiovascular indication. This filing is a critical piece of intelligence. It indicates that Company A is not merely exploring an idea but is investing in formulation R&D to create a differentiated product specifically for the new indication, likely to build a stronger IP moat and support a 505(b)(2) regulatory filing.

By integrating these patent filings with a search on ClinicalTrials.gov, Company B’s team discovers that Company A has initiated a Phase IIa trial for “CardiaCure XR” in diabetic nephropathy. This multi-source analysis allows Company B to anticipate a potential market entry by Company A years in advance. They can now make a strategic decision: accelerate their own internal program for a competing repurposed drug, initiate a search for an asset to in-license, prepare a legal strategy to challenge Company A’s patents, or cede the space and reallocate resources to a different target. This proactive capability, driven by patent intelligence, is the hallmark of a modern competitive strategy.

| Resource Name | Type | Key Data Provided | Strategic Use Case |

| DrugBank | Public Database | Comprehensive drug and drug target information, including pharmacology, interactions, pathways, and product details. | Identifying a drug’s known targets and pathways to generate “on-target” repositioning hypotheses; understanding MOA. |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | Public Database | Registry of public and private clinical trials conducted globally, including study design, status, and adverse events. | Monitoring competitor clinical activity for repurposed drugs; identifying shelved assets; mining adverse event data for potential new indications. |

| PubChem | Public Database | Information on chemical substances and their biological activities. | Sourcing compound information; linking chemical structures to bioassay data to find initial hits. |

| DrugPatentWatch | Commercial Platform | Integrated database of patents, regulatory data, litigation, and generic/biosimilar market entry intelligence. | Forecasting patent expiry and loss of exclusivity; identifying “first-to-file” generic challengers; conducting prior art searches to assess patentability. |

| Cortellis (Clarivate) | Commercial Platform | Comprehensive intelligence on drug pipelines, deals, patents, biomarkers, and clinical trials with analytical tools. | Benchmarking candidates against the competitive landscape; making data-driven go/no-go decisions; forecasting market dynamics. |

| REPO4EU | Public-Private Platform | European platform for mechanism-based drug repurposing, offering resources, training, and matchmaking for stakeholders. | Finding academic or industry partners for collaborative repurposing projects, particularly within the EU. |

| Open Targets | Public-Private Consortium | Integrates genomics, genetics, and chemical data to identify and prioritize drug targets. | Validating the link between a gene/target and a disease to support a target-centric repositioning strategy. |

Table 3: Key Resources for Drug Repositioning Intelligence

Section V: Navigating the Regulatory Gauntlet: Accelerating Pathways to Market

A successful drug repositioning strategy requires not only scientific innovation and robust IP but also a sophisticated understanding of the regulatory landscape. Navigating the correct regulatory pathway can dramatically accelerate timelines, reduce costs, and, most importantly, grant periods of valuable market exclusivity that are essential for commercial success.

5.1 The 505(b)(2) Advantage: A Strategic Analysis of the FDA’s Hybrid Pathway

The primary regulatory tool for repurposed drugs in the United States is the 505(b)(2) New Drug Application (NDA) pathway.65 Established by the Hatch-Waxman Amendments of 1984, this pathway was designed to encourage innovation on existing drugs by creating a streamlined process that avoids the unnecessary duplication of studies.65

- Definition and Purpose: The 505(b)(2) pathway is a hybrid that sits between a full 505(b)(1) NDA for a new chemical entity and a 505(j) Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) for a generic.67 Its key feature is that it allows a sponsor to rely, in part, on data they do not own, such as the FDA’s previous findings of safety and efficacy for a previously approved drug (the “reference listed drug” or RLD), as well as data from published scientific literature.31

- Strategic Application for Repositioning: This pathway is ideally suited for most repositioning projects, including those involving a new indication, a new formulation, a new dosage form, a new route of administration, or a new combination of approved drugs.65 The sponsor must conduct any new studies necessary to bridge their new product to the existing data of the RLD. For example, a new oral formulation may only require pharmacokinetic (PK) bridging studies to demonstrate comparable bioavailability, while a new indication will require new Phase II and III clinical trials to establish efficacy.65

- Trends in Approval: The 505(b)(2) pathway has become a major engine of drug development. Its use has grown dramatically, and in recent years, the number of 505(b)(2) approvals has consistently outpaced that of 505(b)(1) NCEs. In 2024, 505(b)(2) approvals accounted for 40% of all new FDA approvals, even surpassing generic drug approvals, demonstrating its establishment as a mainstream strategic pathway.15

The 505(b)(2) pathway fundamentally alters the risk-reward calculation for pharmaceutical R&D. It creates a viable middle ground of innovation that is less costly and risky than de novo discovery but creates more value and differentiation than standard generic manufacturing. This allows companies to focus investment on clinically meaningful improvements with a higher probability of success and a clear route to market, establishing a distinct and highly attractive business model.65

5.2 Maximizing Market Exclusivity: Regulatory Incentives

Beyond an accelerated timeline, the most significant commercial benefit of the regulatory process is the potential to gain market exclusivity—a period during which the FDA will not approve a competing generic product, regardless of patent status.

- 505(b)(2) Exclusivity: An application approved via the 505(b)(2) pathway may be eligible for three years of market exclusivity if new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) were essential to the approval.65 If the repurposed drug is considered a new chemical entity (e.g., a new salt or ester of a previously approved drug), it may qualify for five years of exclusivity.65

- Orphan Drug Designation (ODD): This is one of the most powerful incentives. If a drug is repurposed to treat a rare disease (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.), it can be granted ODD. Upon approval, an orphan drug receives seven years of market exclusivity for that indication. ODD also provides benefits such as tax credits for clinical trial costs and a waiver of prescription drug user fees.54

- Pediatric Exclusivity: To encourage the study of drugs in children, the FDA can grant an additional six months of market exclusivity, which is appended to any existing patent or regulatory exclusivity periods.57

For a repurposed drug with limited remaining patent life, these regulatory exclusivities can be far more commercially valuable than its patent portfolio. A seven-year monopoly granted through ODD provides a much stronger and more certain shield against competition than a method-of-use patent that can be circumvented by off-label prescribing. Consequently, the potential to secure these regulatory incentives should be a primary consideration in the selection and prioritization of repositioning projects.

5.3 The Generic Repurposing Challenge and Proposed Solutions

A significant gap exists in the current regulatory framework for repurposing off-patent, multi-source generic drugs, particularly for non-commercial sponsors like academic researchers or non-profit organizations.32 These entities may conduct successful clinical trials demonstrating a new use for a cheap, widely available generic, but there is no straightforward pathway for them to get this new indication added to the drug’s official label.68 They are not manufacturers, so they cannot file a traditional NDA, and generic manufacturers have little financial incentive to invest in the process themselves.68

To address this, a “labeling-only” 505(b)(2) pathway has been proposed.68 Under this framework, a non-manufacturer could submit an application based on new clinical data. If approved, the FDA would update the labeling for the drug’s established name, which would then apply to all therapeutically equivalent generic products. The non-manufacturer would be responsible for indication-specific post-marketing surveillance, while product-specific responsibilities would remain with the manufacturers.68 This innovative proposal could unlock the immense therapeutic potential of countless low-cost generic drugs, though it faces complex questions regarding implementation, funding, and liability.

Section VI: Market Landscape and Future Horizons

The drug repositioning market is not only a significant and growing segment of the pharmaceutical industry but is also at the forefront of technological disruption, with artificial intelligence and personalized medicine poised to redefine the future of therapeutic development.

6.1 Market Analysis: Sizing, Segmentation, and Growth Projections

The global drug repurposing market is a substantial economic force. Valuations in 2024 ranged from approximately $29.4 billion to $35.3 billion.10 Projections for the coming decade indicate robust growth, with forecasts for 2030-2034 ranging from $37.3 billion to $59.3 billion, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of anywhere from 2.9% to 8.3%, depending on the scope of the analysis.69

- Key Market Segments:

- By Therapeutic Area: Oncology is currently the largest segment, commanding approximately 37% of the market share.70 This is driven by the high unmet need in cancer, the potential for combination therapies, and a deep understanding of molecular pathways. However, the fastest-growing segment is rare and orphan diseases, with a projected CAGR of nearly 15%. This rapid growth is fueled by strong regulatory incentives (like the Orphan Drug Act), premium pricing potential, and dedicated patient advocacy groups.70

- By Geography: North America is the dominant market, accounting for roughly 45-47% of global revenue. This leadership is sustained by a high level of R&D investment, a mature venture capital ecosystem, and a favorable and well-defined regulatory framework, particularly the 505(b)(2) pathway.10 The Asia-Pacific region is forecast to be the fastest-growing market, driven by increasing healthcare expenditure and expanding research infrastructure.70

- Primary Market Drivers: The market’s expansion is propelled by a confluence of factors. The immense pressure of patent cliffs on blockbuster drugs forces companies to seek lifecycle extension strategies.30 The prohibitive cost and high failure rate of

de novo R&D make the de-risked nature of repositioning highly attractive.71 Furthermore, the rising prevalence of chronic and rare diseases creates a persistent demand for new and more affordable therapeutic options.69

6.2 The AI Disruption: Automating Discovery and Strategy

Artificial intelligence is rapidly transitioning from a specialized tool for candidate identification to an end-to-end engine for drug discovery and development. AI’s ability to analyze vast, multimodal datasets—spanning genomics, proteomics, clinical records, chemical libraries, and scientific literature—is fundamentally changing the speed, scale, and success rate of repositioning efforts.74 AI platforms can predict novel drug-target interactions, identify candidates that reverse disease signatures, and de-risk development by predicting potential toxicity early in the process.78

This technological shift is giving rise to a new class of competitor: the “techbio” company. Firms like Exscientia, Recursion, Standigm, and Bullfrog AI lead with proprietary AI platforms rather than specific biological assets.80 These companies can analyze the entire landscape of approved and failed drugs to generate and prioritize a pipeline of repositioning candidates with unprecedented speed and cost-efficiency.80 As Jordan Lane, CSO of Ignota Labs, noted, “Without the help of AI, it is essentially the status quo, where it is easier to simply throw away a failing drug than to fix it”.83 This indicates that AI is enabling a business model that was previously unviable, posing both a competitive threat and a valuable partnership opportunity for traditional pharmaceutical companies. Industry leaders recognize this shift as a “massive transition from a nascent technology to being a real tool” that is reshaping R&D.84

6.3 The Personalization Paradigm: The Intersection of Drug Repositioning and Precision Medicine

The future of medicine lies in personalization—tailoring treatments to the unique genetic, molecular, and environmental profile of each patient.85 Drug repositioning is a critical enabler of this paradigm shift. By leveraging genomic and biomarker data, repositioning strategies can identify existing drugs that are highly effective for specific, molecularly-defined subgroups of patients within a broader disease category.22 For example, a drug that failed in a large trial for lung cancer might be highly effective in the 5% of patients who carry a specific genetic mutation.

This intersection creates a powerful synergy. Personalized medicine dramatically increases the probability of demonstrating efficacy in a well-defined patient population, thereby de-risking clinical trials.86 While this narrows the potential market for a drug, it also significantly increases its value proposition for that targeted group, justifying value-based pricing.88 This model aligns perfectly with the economics of drug repositioning. The lower development costs associated with repurposing make these smaller, high-value markets commercially attractive, particularly when supported by regulatory frameworks like the Orphan Drug Act.16 This combination makes it economically feasible to develop therapies for highly specific patient populations that would be overlooked by the traditional blockbuster drug model. However, challenges remain, including inter-patient heterogeneity, where not all patients with the same biomarker respond to treatment, and the inevitable development of acquired resistance to targeted therapies, which necessitates ongoing research into combination strategies.22

Section VII: Strategic Imperatives and Recommendations

In an industry defined by high risk and escalating costs, the systematic repositioning of existing drugs has matured from an opportunistic tactic into a core strategic imperative. For pharmaceutical companies, biotechs, and investors, mastering this discipline is essential for sustainable innovation and long-term value creation. The following recommendations provide a blueprint for integrating drug repositioning into corporate strategy and operations.

7.1 Integrating Repositioning into Corporate Strategy: From R&D to Business Development

Drug repositioning should be embedded across the organization as a continuous, systematic function rather than an ad-hoc or isolated activity.

- Portfolio and Lifecycle Management: R&D and commercial teams should proactively and regularly screen their own portfolios of in-line and shelved assets for new therapeutic opportunities. This includes compounds that failed for efficacy but have clean safety profiles, as well as marketed drugs approaching patent expiry. This process transforms the “valley of death” from a cost center into an internal asset library.

- Business Development and In-Licensing: Business development teams should make repositioning a key pillar of their external scouting strategy. This involves actively identifying de-risked assets being divested by large pharmaceutical companies due to portfolio shifts and seeking partnerships with innovative, AI-driven “techbio” companies that can generate high-quality repositioning candidates at scale.

7.2 A Blueprint for Action: Key Steps for Building a Successful Repositioning Program

A successful repositioning program requires the integration of data, technology, and cross-functional expertise.

- Step 1: Establish an Integrated Intelligence Hub: Create a dedicated, cross-functional team comprising experts from R&D, legal/IP, regulatory affairs, and commercial strategy. This team’s mandate is to continuously monitor and synthesize intelligence from patent databases (e.g., USPTO), clinical trial registries (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov), and commercial platforms (e.g., DrugPatentWatch, Cortellis). This hub will serve as the central nervous system for identifying threats and opportunities.

- Step 2: Adopt a Hybrid Discovery Model: Build a discovery engine that combines the strengths of multiple methodologies. Use large-scale computational screening and real-world data analysis to generate and prioritize hypotheses efficiently. Then, use advanced and physiologically relevant experimental models, such as patient-derived organoids and high-content phenotypic screens, for rapid and robust validation of the most promising candidates.

- Step 3: Design for IP from Day One: The R&D process must be inextricably linked with IP strategy. From the earliest stages, development plans should be designed not just to prove efficacy, but to generate data that supports a multi-layered patent portfolio. Prioritize the development of novel formulations, dosages, or combinations that create physically distinct products, as these provide the strongest defense against generic competition and the “skinny label” challenge.

- Step 4: Prioritize with a Regulatory and Commercial Lens: Evaluate potential new indications based on a holistic assessment of their commercial viability. This analysis must go beyond market size to include the strength of the potential IP, the likelihood of securing valuable regulatory exclusivities (e.g., Orphan Drug Designation), and the reimbursement landscape. In many cases, a smaller market with a seven-year orphan drug exclusivity will be a more valuable asset than a larger market protected only by a weaker method-of-use patent.

7.3 Concluding Analysis: The Future of Value Creation in the Pharmaceutical Industry

The pharmaceutical industry is at a crossroads, facing the dual pressures of declining R&D productivity and the imperative to deliver value to patients and healthcare systems. In this environment, the ability to systematically unlock the hidden potential within existing medicines is no longer a peripheral activity but a central driver of innovation and competitive advantage. Drug repositioning, powered by computational biology and guided by sophisticated IP and regulatory strategy, offers a faster, cheaper, and less risky path to developing transformative therapies. The future of pharmaceutical value creation will increasingly belong to those organizations that can master this complex interplay of science, data, and strategy to give old drugs new life.

Works cited

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed July 29, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_repositioning

- Drug repurposing: approaches, methods and considerations – Elsevier, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.elsevier.com/industry/drug-repurposing

- DRUG REPURPOSING – European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network, accessed July 29, 2025, https://ecrin.org/sites/default/files/Ecrin/pdf/Chapter13_final.pdf

- Drug reprofiling history and potential therapies against Parkinson’s disease – Frontiers, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.1028356/full

- Drug Repurposing Strategies, Challenges and Successes …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.technologynetworks.com/drug-discovery/articles/drug-repurposing-strategies-challenges-and-successes-384263

- Chapter 1: Introduction and Historical Overview of Drug Repurposing Opportunities – RSC Books, accessed July 29, 2025, https://books.rsc.org/books/edited-volume/1885/chapter/2472263/Introduction-and-Historical-Overview-of-Drug

- Drug repositioning: a brief overview – PubMed, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32301512/

- Drug repositioning: a brief overview | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340716234_Drug_repositioning_a_brief_overview

- Phenotypic Drug Discovery: Recent successes, lessons learned and …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9708951/

- Drug Repurposing Market: Strategic Approaches, Technological, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/market-report/drug-repurposing-market/273130/

- (PDF) An Overview of Drug Repurposing: Review Article – ResearchGate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361415151_An_Overview_of_Drug_Repurposing_Review_Article

- Drug repositioning: Identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs – ResearchGate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8422835_Drug_repositioning_Identifying_and_developing_new_uses_for_existing_drugs

- Value Propositions for Drug Repurposing – NCBI, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235871/

- What Is Drug Repurposing? | Drug Repositioning – Oakwood Labs, accessed July 29, 2025, https://oakwoodlabs.com/what-is-drug-repurposing/

- The Benefits and Pitfalls of Repurposing Drugs – PHETAIROS, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.phetairos.com/insights/integrated-product-development/the-benefits-and-pitfalls-of-repurposing-drugs/

- Drug Repositioning: Concept, Classification, Methodology, and Importance in Rare/Orphans and Neglected Diseases, accessed July 29, 2025, https://japsonline.com/admin/php/uploads/2711_pdf.pdf

- How drug repurposing can advance drug discovery: challenges and opportunities – Frontiers, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/drug-discovery/articles/10.3389/fddsv.2024.1460100/full

- A Review of Current In Silico Methods for Repositioning Drugs and Chemical Compounds, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8340770/

- Review of Drug Repositioning Approaches and Resources – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6097480/

- Drug repurposing: a systematic review on root causes, barriers and facilitators – PMC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9336118/

- Drug repurposing: A futuristic approach in drug discovery – ResearchGate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372508766_Drug_repurposing_A_futuristic_approach_in_drug_discovery

- Drug repositioning for personalized medicine – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3446277/

- Drug Repositioning: A Review, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.rroij.com/open-access/drug-repositioning-a-review.pdf

- (PDF) Drug Repurposing: Engineering New Uses for Existing …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390389929_Drug_Repurposing_Engineering_New_Uses_for_Existing_Medications

- Drug Repositioning Market Size, Demand, Outlook by 2033 – Business Research Insights, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.businessresearchinsights.com/market-reports/drug-repositioning-market-109017

- Drug Repurposing: An Overview – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drug-repurposing-an-overview/

- Repositioned Drugs: Integrating Intellectual Property and Regulatory Strategy, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251702941_Repositioned_Drugs_Integrating_Intellectual_Property_and_Regulatory_Strategy

- Intellectual property and other legal aspects of drug repurposing – ResearchGate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241120780_Intellectual_property_and_other_legal_aspects_of_drug_repurposing

- The Drug Repurposing Ecosystem: Intellectual Property Incentives, Market Exclusivity, and the Future of “New” Medicines | Yale Journal of Law & Technology, accessed July 29, 2025, https://yjolt.org/drug-repurposing-ecosystem-intellectual-property-incentives-market-exclusivity-and-future-new

- Drug Repurposing Strategic Research Business Report 2024-2025 & 2030 – Patent Expiry Pressures Encourage Pharma Companies to Extend Value of Existing Assets via New Indications – ResearchAndMarkets.com, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250528921205/en/Drug-Repurposing-Strategic-Research-Business-Report-2024-2025-2030—Patent-Expiry-Pressures-Encourage-Pharma-Companies-to-Extend-Value-of-Existing-Assets-via-New-Indications—ResearchAndMarkets.com

- The risk-reward balance in drug repurposing – Alacrita, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/blog/the-risk-reward-balance-in-drug-repurposing

- International regulatory and publicly-funded initiatives to advance drug repurposing, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1387517/full

- Drug repurposing in the era of COVID‐19: a call for leadership and government investment, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/10/drug-repurposing-era-covid-19-call-leadership-and-government-investment

- Drug Repositioning: New Approaches and Future Prospects for Life-Debilitating Diseases and the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak – PubMed Central, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7551028/

- Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations – PharmaKure, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pharmakure.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Drug-Repurposing-Review.pdf

- www.technologynetworks.com, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.technologynetworks.com/drug-discovery/articles/drug-repurposing-strategies-challenges-and-successes-384263#:~:text=Drug%20repurposing%20approaches%20can%20offer,populations%2C%20similar%20to%20novel%20compounds.

- Exploring Drug Repositioning Approaches and Resources – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/review-of-drug-repositioning-approaches-and-resources/

- In silico drug repositioning – what we need to know – CiteSeerX, accessed July 29, 2025, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=8f583b34a66e993faf46d80fca550f351dd81900

- Computational Approaches to Drug Repurposing … – Annual Reviews, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-110123-025333?crawler=true&mimetype=application/pdf

- A review of computational drug repurposing – PMC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6989243/

- Personalized drug repositioning using gene expression – Scholarly Publications Leiden University, accessed July 29, 2025, https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A3619746/download

- Performing an In Silico Repurposing of Existing Drugs by Combining Virtual Screening and Molecular Dynamics Simulation | Springer Nature Experiments, accessed July 29, 2025, https://experiments.springernature.com/articles/10.1007/978-1-4939-8955-3_2

- Phenotypic Screening: A Powerful Tool for Drug Discovery – Technology Networks, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.technologynetworks.com/drug-discovery/articles/phenotypic-screening-a-powerful-tool-for-drug-discovery-398572

- Phenotypic screening – Wikipedia, accessed July 29, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phenotypic_screening

- Phenotypic Screening – Creative Biolabs, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.creative-biolabs.com/drug-discovery/therapeutics/phenotypic-screening.htm

- Target-Based Drug Repositioning Using Large-Scale Chemical-Protein Interactome Data, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26580494/

- Pathway Analysis for Drug Repositioning Based on Public Database Mining, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ci4005354

- Combining Target Based and Phenotypic Discovery Assays for Drug Repurposing, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0gzc0n_QClg

- Drug Repurposing: Innovative Approaches and Clinical Impact – IJCRT, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2507170.pdf

- Drug repositioning: computational approaches and research examples classified according to the evidence level, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6941545/

- Framework for identifying drug repurposing candidates from …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jamiaopen/article/3/4/536/6055941

- Computational Drug Repositioning: Current Progress and Challenges – MDPI, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/10/15/5076

- Patenting New Uses for Old Inventions – Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law, accessed July 29, 2025, https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2919&context=vlr

- Biopharmaceuticals: The Patent Implications of Drug Repurposing – PatentPC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-implications-of-drug-repurposing

- Patenting Repurposed Drugs – Patent Docs, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.patentdocs.org/2018/09/patenting-repurposed-drugs.html

- Why Method of Treatment Patents for Repurposed Drugs Are Worth …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/why-method-of-treatment-patents-for-92813/

- Intellectual Property Rights and Regulatory Considerations for Drug Repurposing, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/intellectual-property-rights-and-regulatory-considerations-for-drug-repurposing/

- Repurposing generic drugs can reduce time and cost to develop new treatments, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.michiganmedicine.org/health-lab/repurposing-generic-drugs-can-reduce-time-and-cost-develop-new-treatments

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed July 29, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- What are the top Biopharmaceutical Business Intelligence Services …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-are-the-top-biopharmaceutical-business-intelligence-services/

- Publications Directory | DrugBank Help Center, accessed July 29, 2025, https://dev.drugbank.com/publications?__hsfp=3300808088&__hssc=52229942.1.1742256000181&__hstc=52229942.73bd3bee6fa385653ecd7c9674ba06f0.1742256000178.1742256000179.1742256000180.1&page=385

- Cortellis Drug Discovery Intelligence Platform | Clarivate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://clarivate.com/life-sciences-healthcare/research-development/discovery-development/cortellis-pre-clinical-intelligence/

- Cortellis Pharma Competitive Intelligence & Analytics | Clarivate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://clarivate.com/life-sciences-healthcare/portfolio-strategy/competitive-intelligence/cortellis-competitive-intelligence-analytics/

- The role of IP in strategies for repurposing medicines – Pinsent Masons, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/the-role-of-ip-strategies-repurposing-medicines

- Review of Drugs Approved via the 505(b)(2) Pathway: Uncovering …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/review-of-drugs-approved-via-the-505b2-pathway-uncovering-drug-development-trends-and-regulatory-requirements/

- 505(b)(2) Pathway | CRO Services | Consulting – Premier Research, accessed July 29, 2025, https://premier-research.com/expertise/505b2-development-pathway/

- 505(b)(1) vs 505(b)(2): Understanding the Key Differences in FDA Drug Approval Processes, accessed July 29, 2025, https://vicihealthsciences.com/505b1-vs-505b2/

- Clearing the Path for New Uses for Generic Drugs, accessed July 29, 2025, https://fas.org/publication/clearing-the-path-for-new-uses-for-generic-drugs/

- Drug Repurposing Market Size, Industry Trends And Future Outlook By 2033, accessed July 29, 2025, https://straitsresearch.com/report/drug-repurposing-market

- Drug Repurposing Market Size, Share & 2030 Growth Trends Report, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/drug-repurposing-market

- Drug Repurposing Market Size, Share, Trends, Analysis & Forecast, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/drug-repurposing-market/

- Drug Repurposing Market Size, Competitors & Forecast to 2030, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/drug-repositioning-market

- Drug Repurposing Market Size to Hit USD 59.30 Billion by 2034 – Precedence Research, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.precedenceresearch.com/drug-repurposing-market

- Opportunities and Challenges in Drug Repurposing – Frontiers, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/64551/opportunities-and-challenges-in-drug-repurposing

- The Future of Personalized Medicine AI-Driven Solutions in Drug Discovery and Patient Care – ResearchGate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389919887_The_Future_of_Personalized_Medicine_AI-Driven_Solutions_in_Drug_Discovery_and_Patient_Care

- Full article: Drug discovery in the context of precision medicine and artificial intelligence, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23808993.2024.2393089

- Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Drug Repurposing – PMC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11984889/

- AI in Precision Medicine: Benefits, Case Studies & Future Trends – Intuz, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.intuz.com/blog/generative-ai-in-precision-medicine

- Accelerated Drug Repurposing With AI and Machine Learning – Aptitude Health, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.aptitudehealth.com/oncology-news/accelerated-drug-repurposing-ai-machine-learning/

- Top 10 AI Drug Discovery Startups to Watch in 2025 – GreyB, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/ai-drug-discovery-startups/

- AI-Driven Drug Rescue and Repurposing – Bullfrog AI, accessed July 29, 2025, https://bullfrogai.com/solutions/drug-rescue-and-repurposing/

- Drug Repurposing | Accelerating Drug Development – Delta4 | AI, accessed July 29, 2025, https://delta4.ai/services/

- How biotechs are using AI to rescue failed drugs – Labiotech.eu, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.labiotech.eu/in-depth/ai-rescuing-failed-drugs/

- AI’s ‘massive transition’ in biopharma shapes leadership mindsets — tension and all, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.pharmavoice.com/news/biotech-ai-sanofi-jnj-pharma-mindset/752019/

- Pharmacogenomics and Drug Repositioning – Number Analytics, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/pharmacogenomics-drug-repositioning-personalized-medicine

- The Impact of Personalized Medicine on Pharmaceutical Industry, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.precisionmedicineinvesting.com/the-impact-of-personalized-medicine-on-pharmaceutical-industry

- Computational Drug Repositioning: Current Progress and Challenges – ResearchGate, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343170864_Computational_Drug_Repositioning_Current_Progress_and_Challenges

- Impact of Precision Medicine on Drug Repositioning and Pricing: A Too Small to Thrive Crisis, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6313451/

- Impact of Precision Medicine on Drug Repositioning and Pricing: A Too Small to Thrive Crisis – MDPI, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4426/8/4/36