Introduction – An Industry in Transformation

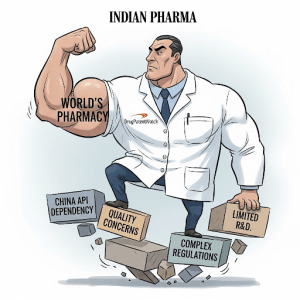

The Indian pharmaceutical industry stands as a colossus in the global healthcare landscape, a testament to decades of strategic policy, manufacturing prowess, and entrepreneurial vision. Familiarly known as the “Pharmacy of the World,” the sector has built an unparalleled reputation for providing affordable, high-quality medicines to virtually every corner of the globe.1 However, this behemoth is now at a critical inflection point. The very foundations of its success—high-volume, low-cost generic drug production—are being tested by a confluence of new challenges and opportunities. The industry’s next chapter will be defined not by its ability to simply scale production, but by its capacity to innovate, climb the value chain, and transition from a global manufacturer to a global leader in healthcare solutions.

The scale of the Indian pharmaceutical industry is immense. In the fiscal year 2023-24, the market was valued between USD 50 billion and USD 65 billion, a figure that underscores its significant economic contribution.1 This valuation is built on a robust export engine, with exports valued at USD 26.5 billion, slightly outpacing domestic consumption at USD 23.5 billion.4 The industry’s growth trajectory is equally impressive, with projections indicating a surge to USD 120-130 billion by 2030 and an ambitious target of USD 400-450 billion by 2047.1 This anticipated expansion, supported by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) estimated between 8.1% and 11.32%, signals a period of profound transformation and opportunity.9

Yet, a defining characteristic of the Indian pharmaceutical landscape is a striking paradox: its immense scale in production volume is not mirrored in its global value ranking. While the nation stands as the third-largest producer of pharmaceuticals by volume, it ranks a distant 13th or 14th by value.1 This disparity is not merely a statistical curiosity; it is the central strategic challenge that defines the industry’s past, present, and future. It is a direct consequence of a business model historically centered on the production of generic medicines, which, while essential for global health equity, command lower prices than their patented counterparts.13 This volume-value gap highlights the urgent need for the industry to move up the value chain. The ambitious growth targets for 2030 and beyond cannot be achieved by simply producing more of the same; they necessitate a strategic pivot towards more complex, higher-value products.

This pivot is already underway, giving rise to a “two-speed” industry. The foundational business of traditional generics remains a cornerstone, providing essential medicines and stable revenue streams. However, the engines of future growth are increasingly found in high-value segments like biologics, biosimilars, complex generics, and specialty drugs.8 This diversification is not happening in a vacuum; it is being actively encouraged by government policy. The formulation of a “National Policy on Research & Development and Innovation in the Pharma-MedTech Sector” and the launch of the Scheme for Promotion of Research & Innovation in Pharma Sector (PRIP) are clear signals of a national strategy to foster an ecosystem of innovation.4 This creates a dynamic where established generic players must balance operational efficiency with strategic investments in R&D, while a new class of innovation-focused firms emerges, leading to a future likely defined by strategic partnerships, consolidation, and a divergence of business models.

The Indian pharmaceutical industry, having built its global dominance on a foundation of cost-effective generic manufacturing, is now at a strategic crossroads. To achieve its ambitious growth targets and evolve from the “Pharmacy of the World” to an indispensable global healthcare leader, it must navigate profound challenges—including supply chain vulnerabilities, stringent regulatory scrutiny, and a shifting intellectual property landscape—while strategically embracing innovation in high-value segments and leveraging the transformative power of digital technologies. This report will provide an exhaustive analysis of this journey, dissecting the historical forces that shaped the industry, the complex regulatory environment it operates within, the critical challenges it confronts, and the promising growth vectors that will define its future.

| Metric | Value | Sources |

| Market Size (FY 2024) | USD 50-65 Billion | 1 |

| Projected Market Size (2030) | USD 120-130 Billion | 1 |

| Projected Market Size (2033/2047) | USD 174-450 Billion | 7 |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2033) | 8-12% | 9 |

| Global Rank (by Volume) | 3rd | 1 |

| Global Rank (by Value) | 13th/14th | 1 |

| Share of Global Generics Supply | ~20% | 1 |

| Share of Global Vaccine Supply | ~60% | 1 |

The Bedrock of a Behemoth – A Legacy of Policy and Ingenuity

The ascent of the Indian pharmaceutical industry to global prominence was not a matter of chance or a simple market phenomenon. It was the direct result of a series of deliberate, strategic, and often audacious policy decisions that fundamentally reshaped the nation’s industrial and public health landscape. To understand the industry’s current strengths and challenges, one must first appreciate the historical arc of its development, a journey marked by a revolutionary pivot in patent law that transformed India from a dependent importer into a self-reliant global supplier.

Pre-1970s: The Era of Multinational Dominance

Before 1970, the Indian pharmaceutical market bore little resemblance to its current form. It was overwhelmingly dominated by multinational corporations (MNCs), which controlled the vast majority of the market through the import of finished drug formulations.14 The legal framework of the time, the Indian Patent Act of 1911, was a relic of the British colonial era. This act provided robust protection for both product and process patents for extended periods, making it illegal for indigenous Indian firms to manufacture or sell drugs patented by foreign companies.18

The consequences of this structure were profound. Drug prices were prohibitively high for a large segment of the population in a developing nation, and access to essential medicines was severely limited.14 The domestic industry was nascent and fragmented, largely confined to distributing or, in some cases, formulating products under license from MNCs. India was a net importer of medicines, dependent on foreign innovation and supply chains for its healthcare needs. This state of dependency, coupled with the pressing public health challenges of a post-independence nation, set the stage for a radical policy shift.

The 1970 Indian Patents Act: A Revolutionary Pivot

The single most transformative event in the history of the Indian pharmaceutical industry was the passage of the Indian Patents Act in 1970. This legislation was not merely a technical adjustment to intellectual property law; it was a profound act of industrial policy designed to achieve two clear national objectives: ensuring access to affordable medicines for its citizens and building a self-sufficient domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing base.19

The genius of the 1970 Act lay in a critical distinction it made for pharmaceuticals, food, and chemicals. It completely abolished product patents, meaning the final drug molecule itself could not be patented in India. Instead, it only recognized process patents, which protected the specific method of manufacturing a drug.14 Furthermore, the term for these process patents was shortened to just five to seven years, a fraction of the duration in Western countries.21

This legal framework effectively legalized and incentivized what came to be known as “reverse engineering.” Indian scientists and companies could now legally develop and patent alternative, non-infringing processes to manufacture drugs that were under product patent protection elsewhere in the world.14 This allowed them to produce generic versions of the latest medicines without paying royalties to the original innovator. This policy masterstroke, combined with supportive measures like the Drug Policy of 1978 and the Drug Price Control Order (DPCO), created a fertile ground for the domestic industry.13

The impact was immediate and dramatic. Freed from the constraints of product patents, a wave of Indian pharmaceutical companies emerged, mastering the chemistry of reverse engineering and scaling up production of affordable generic drugs. The nation’s status rapidly shifted from being a major medicine importer to a leading exporter by the 1980s.13 The 1970 Act provided the bedrock upon which the entire Indian generics powerhouse was built, fostering a unique ecosystem of process chemistry expertise, cost-efficient manufacturing, and entrepreneurial dynamism.

The Global Pivot: TRIPS and the 2005 Amendment

The era of process patents, while transformative for India, was out of step with the evolving global consensus on intellectual property rights. When India became a founding member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, it committed to complying with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).18 A central requirement of the TRIPS agreement was the re-introduction of product patents for pharmaceuticals for a uniform term of 20 years.

This necessitated a fundamental overhaul of the 1970 Act. After a transitional period, India passed the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005, bringing its legal framework into compliance with its international obligations.19 This amendment marked the end of the golden age of legal reverse engineering in India. Indian companies could no longer freely produce generic versions of newly patented drugs.

This seismic shift forced a complete strategic reorientation. To survive and thrive in the new TRIPS-compliant world, Indian firms had to evolve their business models. They aggressively turned their focus to the global generics market, particularly the United States, where the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act had created a streamlined pathway for generic drug approval (the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA process).13 Indian companies became experts at navigating this complex regulatory landscape, challenging innovator patents, and competing on a global scale.

The 2005 amendment also catalyzed a new focus on research and development. With the “copycat” model no longer viable for new drugs, companies began to invest in their own R&D, aiming to develop complex generics, create novel drug delivery systems, and, for the most ambitious, embark on the long journey of new drug discovery.19 This period also saw a surge in foreign acquisitions and international partnerships as Indian firms sought to gain market access, acquire technology, and build global scale.21 The modern Indian pharmaceutical giant—a globally integrated, export-focused, and increasingly R&D-aware entity—is a direct product of the strategic pivot forced by the 2005 amendment. It was this legislation that set the industry on its current path, competing not just on cost, but increasingly on quality, complexity, and innovation.

The Tightrope Walk – Navigating India’s Complex Patent and Pricing Regime

While the 2005 amendment brought India’s patent laws into alignment with global standards, it did not signal a complete abandonment of the nation’s long-standing commitment to public health. Instead, Indian policymakers skillfully embedded a series of unique provisions within the legal framework, creating a multi-layered system designed to balance the encouragement of innovation with the imperative of ensuring access to affordable medicines. These provisions, often referred to as “TRIPS flexibilities,” represent a coherent strategy to manage the transition to a product patent regime. They are not isolated rules but an interconnected system of checks and balances. Navigating this intricate and often contentious landscape—comprising Section 3(d), the Drug Price Control Order, and Compulsory Licensing—is a constant tightrope walk for every pharmaceutical company operating in India.

Section 3(d) – The Bulwark Against “Evergreening”

At the heart of India’s unique patent regime lies Section 3(d) of the Patents Act. This provision is the country’s primary legislative tool to combat a practice known as “evergreening”—a strategy used by some innovator companies to extend their patent monopolies by making minor, often non-innovative, modifications to an existing drug and filing for new patents.24 Section 3(d) explicitly states that a “mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance” is not a patentable invention.23

This clause acts as a crucial pre-grant filter, raising the bar for what constitutes a genuine invention in the pharmaceutical space. It creates a legal presumption that new forms of a known drug—such as salts, esters, or different crystalline structures (polymorphs)—are not patentable. The burden of proof then shifts to the patent applicant to demonstrate that the new form exhibits a significant enhancement in “therapeutic efficacy” over the original substance.25

The definitive interpretation of this provision was cemented in the landmark 2013 Supreme Court case, Novartis AG v. Union of India & Others, popularly known as the Gleevec case. Novartis sought a patent for Gleevec (Imatinib Mesylate), the beta-crystalline salt form of its anti-cancer drug Imatinib, arguing that this new form had significantly improved bioavailability compared to the original free base form.28 The Indian Patent Office, and subsequently the courts, rejected the patent application, a decision that was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court. The court’s ruling was pivotal, as it provided a clear and stringent definition of “efficacy” in the context of pharmaceuticals.

The Supreme Court of India, in its judgment, clarified that for a new form of a known substance to be patentable under Section 3(d), the enhancement in properties must translate into a tangible improvement in its performance as a medicine. The court established that “in the case of a medicine that has a therapeutic effect, the test of efficacy can only be ‘therapeutic efficacy’.” Minor improvements in physicochemical properties like bioavailability, which did not demonstrate a clear advantage in treating the disease, were deemed insufficient to overcome the bar set by Section 3(d).28

This judgment has had a profound and lasting impact. It forces innovator companies to provide robust clinical data demonstrating genuine therapeutic advancement for any secondary patents. This not only prevents the extension of monopolies on trivial modifications but also creates earlier market entry points for generic competition, thereby promoting affordability.24 The very existence of this high standard compels companies to self-censor, altering their global R&D and patent filing strategies to focus on truly innovative products when considering the Indian market.

The Price Ceiling – The Drug Price Control Order (DPCO)

While Section 3(d) acts as a gatekeeper for new patents, the Drug Price Control Order (DPCO) serves as a post-grant price regulation mechanism for medicines already on the market. Issued under the Essential Commodities Act of 1955, the DPCO empowers the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) to fix ceiling prices for drugs included in the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM).30 The primary objective is to ensure that crucial, life-saving drugs remain affordable and accessible to all strata of society.30

The impact of the DPCO on the industry is distinctly dual-edged, creating different outcomes for different types of players. For large pharmaceutical companies and MNCs, price controls can significantly slash profitability on some of their key products. This can act as a disincentive to invest in the manufacturing and marketing of essential medicines, and in some cases, has led to companies discontinuing certain brands or even being deterred from launching new, innovative drugs in the Indian market.31 The reduced profitability from price-controlled drugs is also frequently cited as a factor that can stifle R&D investment, with some firms reportedly shutting down or relocating their research centers.31

Conversely, for small and medium-sized domestic companies focused on generic manufacturing, the DPCO can be a boon. By capping the prices of branded medicines, the order levels the competitive playing field. It allows smaller firms producing low-cost generics to compete effectively on price with established, larger brands. This has, in some instances, led to an increase in sales and market share for these smaller players, as the price differential between their products and the branded alternatives narrows or disappears.31 The DPCO thus acts as a powerful market-shaping force, directly influencing corporate strategy, profitability, and investment decisions across the sector.

A Tool of Last Resort – Compulsory Licensing in Practice

The third pillar of India’s access-to-medicines framework is compulsory licensing (CL). This provision in the Indian Patent Act serves as a critical safety valve, allowing the government to authorize a third party (typically a generic manufacturer) to produce a patented drug without the consent of the patent holder under specific circumstances.19 The grounds for granting a CL are clearly defined: if the reasonable requirements of the public for the patented invention have not been met, if it is not available to the public at a reasonably affordable price, or if the patent is not “worked” in the territory of India.26

This provision was put to the test in 2012 in the landmark case of Natco Pharma vs. Bayer Corporation. The Indian Patent Office granted the country’s first and, to date, only compulsory license to the domestic firm Natco Pharma for Bayer’s patented kidney and liver cancer drug, Nexavar.26 The decision was based on compelling evidence that Bayer had failed to meet the needs of the Indian public. The company was supplying the drug to only a tiny fraction of the patient population and was pricing it at an exorbitant ₹280,000 (approximately USD 5,500 at the time) for a month’s course, rendering it inaccessible to the vast majority of patients.26 Under the terms of the CL, Natco was permitted to manufacture and sell a generic version for just ₹8,800 per month, while being obligated to pay a 6% royalty on its sales to Bayer.26

The Nexavar case ignited a fierce global debate, pitting the principles of intellectual property rights and innovation incentives against the urgent needs of public health.35 While celebrated by access-to-medicines advocates worldwide as a victory for patients, the decision drew heavy criticism from innovator pharmaceutical companies and the governments of developed nations, who argued that it would undermine the patent system and stifle future R&D.36

Despite the controversy, the true power of India’s compulsory licensing provision may lie less in its application and more in its potential. With only one CL granted in over a decade, its primary impact has been as a deterrent.39 The credible threat that a CL could be issued for a high-priced, undersupplied drug has subtly but significantly influenced the behavior of some multinational corporations. This has prompted some to adopt more flexible pricing strategies, engage in early-dialogue with the government, or enter into voluntary licensing agreements with Indian generic manufacturers to ensure broader access and avoid triggering the CL provisions.35

Together, Section 3(d), the DPCO, and compulsory licensing form a sophisticated and interlinked regulatory system. They represent India’s strategic effort to navigate the complexities of a globalized IP world while holding firm to its foundational commitment to the health and well-being of its people.

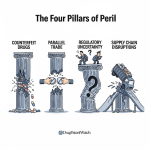

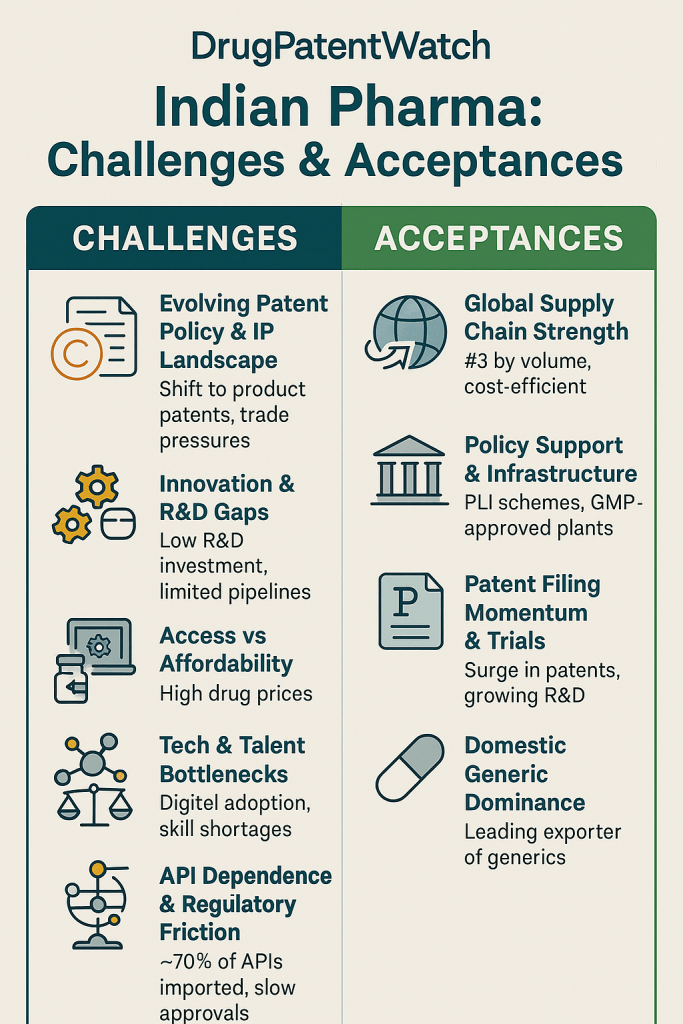

Confronting the Headwinds – Key Strategic Challenges

While the Indian pharmaceutical industry is poised for significant growth, its path forward is not without formidable obstacles. The sector is currently grappling with a series of deep-seated strategic challenges that test its resilience, operational excellence, and adaptability. These headwinds—ranging from critical supply chain vulnerabilities and intense regulatory scrutiny to the competitive pressures of a shifting global market—must be navigated successfully to secure the industry’s future and realize its ambitious vision. Addressing these issues is not merely a matter of operational improvement; it is fundamental to the industry’s transition from a cost-driven manufacturer to a quality- and innovation-led global powerhouse.

The Dragon in the Supply Chain: De-risking API Dependence on China

One of the most significant vulnerabilities of the Indian pharmaceutical industry is its profound dependence on China for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)—the core chemical compounds that provide a drug’s therapeutic effect—and Key Starting Materials (KSMs), the building blocks for APIs. Despite its status as a finished-formulation giant, India imports approximately 70% of its total API requirements from China.40 This reliance is even more acute for certain essential, life-saving drugs. For common antibiotics like penicillin and analgesics like paracetamol, the dependency on Chinese imports can be as high as 90-100%.42

This situation is a relatively recent development. Before the economic liberalization of the 1990s, India was largely self-sufficient in API manufacturing.42 The shift occurred as Chinese manufacturers, benefiting from economies of scale, state subsidies, and less stringent environmental regulations, began to offer APIs at prices that were often 20% lower than those of Indian producers.40 Faced with this cost differential, many Indian companies found it more economical to import APIs rather than manufacture them, leading to the gradual erosion of the domestic API production base.

This over-reliance creates a precarious situation, exposing the Indian healthcare system to significant geopolitical risks, supply chain disruptions, and price volatility. This vulnerability was starkly highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic and amid geopolitical tensions, when lockdowns in China threatened to halt the supply of essential raw materials, jeopardizing India’s drug security.43

In response, the Indian government has launched a major policy push toward self-reliance, or “Atmanirbhar Bharat,” in the pharmaceutical sector. The cornerstone of this strategy is the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes:

- PLI Scheme for Bulk Drugs: With a financial outlay of ₹6,940 crore, this scheme is designed to incentivize the domestic manufacturing of 41 critical APIs, KSMs, and drug intermediates where import dependence is particularly high.16

- PLI Scheme for Pharmaceuticals: This is a broader scheme with an outlay of ₹15,000 crore, aimed at boosting domestic manufacturing of a range of high-value products, including biopharmaceuticals, complex generics, and other advanced APIs.2

These schemes are beginning to show results. By late 2023, manufacturing had commenced for 35 APIs under the PLI initiative, with projections suggesting that India could reduce its reliance on Chinese imports by up to 35% by the end of the decade.43 However, significant challenges remain. Overcoming the entrenched cost advantages of Chinese suppliers and the long gestation periods required to build new, large-scale, and environmentally compliant manufacturing facilities is a long-term endeavor that will require sustained policy support and capital investment.46

The Quality Imperative: Under the Lens of the US FDA

Maintaining impeccable quality and compliance with stringent international regulatory standards is a perpetual and paramount challenge for an industry that exports to over 200 countries. India holds the distinction of having the highest number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved manufacturing plants outside of the United States, with over 650 facilities.8 This extensive footprint is a testament to the industry’s capability. However, it also means that the sector is under constant and intense scrutiny.

Consequently, Indian firms frequently receive FDA Form 483s (inspectional observations) and, in more serious cases, Warning Letters. In the fiscal year 2023, for instance, Indian companies received 7 of the 16 inspection-based warning letters issued to foreign pharmaceutical firms, highlighting the persistent nature of compliance issues.48 A systematic analysis of these warning letters reveals a pattern of recurring deficiencies that point to systemic challenges in quality management.

| CFR Citation | Deficiency Description | Example from Warning Letters | Sources |

| 21 CFR 211.100(a) | Failure to establish adequate written procedures for production and process control. | Lack of process validation for OTC products; inconsistent manufacturing workflows. | 48 |

| 21 CFR 211.22 | Failure of the quality control unit to exercise its responsibility and ensure cGMP compliance. | Inadequate oversight of manufacturing and laboratory operations; failure to review batch records. | 48 |

| 21 CFR 211.192 | Failure to thoroughly investigate any unexplained discrepancy or out-of-specification (OOS) result. | Releasing product batches despite failing test results; inadequate root cause analysis. | 48 |

| 21 CFR 211.67/58 | Failure to properly clean and maintain equipment and facilities (Insanitary conditions). | Visible contamination in manufacturing equipment; facilities in a state of disrepair. | 49 |

| Data Integrity Issues | Lack of reliable laboratory controls and documentation practices. | Deletion of failing test data; backdating of records; inadequate audit trails on electronic systems. | 49 |

These compliance failures have severe consequences, including import alerts that block products from entering the US market, significant financial costs for remediation, and lasting damage to a company’s reputation. The post-COVID increase in the pace and intensity of USFDA inspections has further amplified the pressure on Indian companies to move beyond a mindset of mere compliance to embedding a deep culture of quality-first throughout their organizations.52 The drive for low costs that led to API dependency is intrinsically linked to these quality pressures; a business model built on cost-competitiveness can sometimes lead to underinvestment in the robust quality management systems, advanced equipment, and continuous training that are essential for meeting global standards. Solving the quality problem, therefore, requires a fundamental strategic shift towards prioritizing quality and data integrity above all else.

Navigating the Patent Cliff: A Multi-Billion Dollar Opportunity

Amid these challenges lies one of the single greatest opportunities for the Indian pharmaceutical industry: the “patent cliff.” This term describes the phenomenon where blockbuster drugs, often with annual sales in the billions of dollars, lose their patent protection, leading to a sharp decline in revenue for the innovator company as lower-priced generic and biosimilar versions flood the market.53

The scale of the impending patent cliff is staggering. Between 2022 and 2030, drugs with combined global sales of over USD 250 billion are set to go off-patent.52 This represents a massive transfer of market value and a golden opportunity for the Indian generics and biosimilars industry to capture significant market share.

| Drug Name (Brand) | Active Ingredient | Innovator Company | Therapeutic Area | Peak Global Sales (Approx.) | Expected US Patent Expiry | Opportunity for India |

| Keytruda | Pembrolizumab | Merck | Oncology | > USD 29 Billion | ~2029 | Biosimilar |

| Eliquis | Apixaban | Bristol Myers Squibb / Pfizer | Cardiology | > USD 12 Billion | ~2028 | Complex Generic |

| Opdivo | Nivolumab | Bristol Myers Squibb | Oncology | > USD 9 Billion | ~2028 | Biosimilar |

| Darzalex | Daratumumab | Johnson & Johnson | Oncology | > USD 10 Billion | ~2029 | Biosimilar |

Note: Sales figures and expiry dates are estimates and subject to change based on market conditions and patent litigation. 53

Capitalizing on this opportunity, however, is a complex strategic endeavor that requires more than just manufacturing capacity. Success hinges on several key imperatives:

- Sophisticated Competitive Intelligence: Identifying the most promising targets requires meticulous tracking of patent expiration dates, ongoing patent litigation, and regulatory filings. This is where specialized competitive intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable. Such services provide the critical, real-time data that allows companies to monitor the patent landscape, identify vulnerable patents, anticipate market entry timelines, and make informed decisions about which products to add to their R&D pipelines.25

- First-to-File (FTF) Strategy: In the lucrative US market, the first company to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with a patent challenge can be granted a 180-day period of generic market exclusivity. Securing this “first-to-file” status is a highly sought-after and profitable strategy.

- Speed-to-Market and Regulatory Agility: In an increasingly crowded generic market, being one of the first companies to launch a product immediately following patent expiry is crucial for capturing initial market share before prices erode due to intense competition.52

- Focus on Complexity: The most significant opportunities no longer lie in simple, small-molecule generics. The biggest blockbuster drugs going off-patent are increasingly complex biologics. To compete, Indian firms must develop capabilities in producing biosimilars and other complex generics, which have higher barriers to entry, require more significant investment, and offer better profit margins.8

The patent cliff is therefore more than just a market opportunity; it is a powerful forcing function for capability building. To seize the most valuable prizes, Indian firms are compelled to invest in the advanced R&D, sophisticated manufacturing processes, and complex clinical trial expertise required for biologics. This process is accelerating the industry’s evolution up the value chain, building the very competencies it needs to transition from “Make in India” to “Discover in India.”

The Dawn of a New Era – Charting the Future Growth Trajectory

As the Indian pharmaceutical industry navigates the complex challenges of the present, it is simultaneously laying the groundwork for a future defined by innovation, technological sophistication, and a strategic move up the global value chain. The narrative is shifting from a focus on volume to an emphasis on value. This transformation is being powered by three interconnected growth engines: the rapid expansion into high-value biologics and biosimilars, the catalytic adoption of digital technologies and artificial intelligence, and a concerted national effort to transition from a manufacturing hub to an innovation powerhouse. These trends are not merely incremental changes; they represent a fundamental reshaping of the industry’s capabilities, ambitions, and global role.

Beyond Generics: The Rise of Biosimilars and Specialty Drugs

The most significant and immediate growth vector for the Indian pharmaceutical industry is its burgeoning leadership in the biosimilars market. Biosimilars are highly similar, approved versions of original biologic medicines, and they represent a critical pathway to providing more affordable access to complex, life-saving therapies. India has emerged as a global frontrunner in this segment. As of early 2025, the country had approved over 135 biosimilar products for its domestic market, a number that surpasses that of any other nation, including the highly regulated markets of the US and Europe.1

The market projections for this segment are staggering. The Indian biosimilars market, valued at approximately USD 866 million in 2024, is forecast to experience explosive growth, with estimates projecting it to reach over USD 12 billion by 2025-2030. This represents a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of between 17% and 22%, making it one of the fastest-growing segments in the entire pharmaceutical landscape.1

This growth is being driven by a perfect storm of factors:

- The Biologic Patent Cliff: As detailed previously, a wave of blockbuster biologic drugs is losing patent protection, creating an immense market opportunity for more affordable biosimilar alternatives.60

- Rising Disease Burden: The increasing prevalence of chronic and complex diseases, particularly in oncology, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders, is fueling demand for biologic therapies, and consequently, their cost-effective biosimilar counterparts.59

- Domestic Expertise: A cadre of leading Indian companies, including Biocon, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Zydus Lifesciences, and Lupin, have invested heavily in building the complex R&D and manufacturing capabilities required for biologics, establishing a robust pipeline of products for both domestic and international markets.8

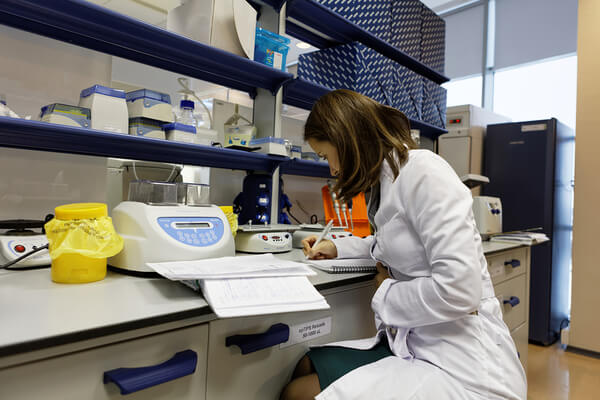

This push into biosimilars is more than just a commercial strategy; it is a crucial stepping stone. The development of biosimilars requires deep expertise in complex biological processes, such as protein engineering and large-scale cell culture manufacturing, as well as the ability to navigate sophisticated regulatory pathways. These are the exact foundational capabilities necessary for the far more challenging and rewarding endeavor of discovering and developing novel biologic drugs. By mastering the biosimilars space today, the Indian industry is building the scientific and operational infrastructure to become a hub for novel biologics innovation tomorrow.

The Digital Catalyst: AI and Data Analytics in Indian Pharma

Parallel to the shift in product focus is a technological revolution transforming how drugs are discovered, developed, and manufactured. The Indian pharmaceutical industry is progressively moving from traditionally manual operations to embracing the principles of Industry 4.0, integrating automation, the Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data, and, most significantly, Artificial Intelligence (AI).61 This digital transformation is no longer a choice but a prerequisite for maintaining competitiveness and meeting stringent global quality standards.

The applications of AI and Machine Learning (AI/ML) are being felt across the entire pharmaceutical value chain:

- R&D and Drug Discovery: AI is being deployed to dramatically accelerate the traditionally slow and costly process of drug discovery. AI algorithms can analyze vast biological and chemical datasets to identify promising drug targets, predict molecular interactions, and screen potential drug candidates with unprecedented speed and accuracy. Projections suggest that AI can reduce drug discovery timelines by 30-40% and cut early-stage development costs by as much as 25-50%.8

- Manufacturing and Quality Control: In the manufacturing plant, AI is a powerful tool for enhancing compliance and efficiency. AI-driven predictive maintenance algorithms can anticipate equipment failures, minimizing costly downtime. Real-time monitoring of production lines using IoT sensors and AI analytics helps ensure consistent quality, reduce human error, and maintain the impeccable data integrity demanded by regulators like the US FDA.61

- Clinical Trials: AI is also optimizing the clinical trial process by helping to design more efficient trial protocols, identifying and recruiting suitable patient populations more quickly, and analyzing trial data to generate faster, more reliable insights.66

Leading Indian companies are already well on this path. Firms like Sun Pharma, Dr. Reddy’s, and Lupin are actively investing in digital initiatives, implementing data-driven manufacturing processes, and transitioning from paper-based records to electronic batch manufacturing records (eBMRs) to meet global compliance standards.61 On the commercial front, companies are leveraging digital engagement platforms to connect with healthcare professionals in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities, breaking down geographical barriers and improving market access.68 This digital adoption is directly addressing the core quality and data integrity challenges that have historically led to regulatory actions, making it a fundamental strategy for survival and success in regulated markets.

From ‘Make in India’ to ‘Discover in India’

The culmination of these trends—the move into high-value biologics and the deep integration of digital technology—is fueling a larger, national ambition: to transition the Indian pharmaceutical industry from being primarily a contract manufacturer to becoming a hub of genuine innovation. This strategic vision, encapsulated in the mantra “From ‘Make in India’ to ‘Discover in India’,” is shared by both industry leaders and government policymakers.8

This is not just rhetoric; it is backed by concrete policy and investment. The government’s “National Policy on R&D and Innovation” and the PRIP scheme, with its ₹5,000 crore outlay, are explicitly designed to create a vibrant ecosystem that supports everything from basic research to late-stage clinical development.4 In parallel, Indian companies are significantly increasing their R&D expenditures, with a growing focus on developing novel therapies, including next-generation modalities like cell and gene therapies, in addition to complex generics and biosimilars.61 This growing commitment to innovation is reflected in a surge in patent filings by Indian firms, signaling the development of a stronger domestic R&D base and a move towards creating, rather than just replicating, intellectual property.61

As Amitabh Kant, former CEO of NITI Aayog, aptly stated, for the industry to achieve its potential of reaching USD 500 billion by 2047, “it needs to shift gears from ‘Make in India’ to ‘Discover in India for the world'”.8 This represents the ultimate goal of the current transformation—to leverage India’s existing strengths in manufacturing and its emerging capabilities in science and technology to become a source of novel, life-saving medicines for the world.

Titans of the Industry – Profiles in Strategy and Success

The story of the Indian pharmaceutical industry’s global rise is best understood through the strategic decisions and relentless execution of its leading companies. These firms have not only shaped the domestic market but have also become formidable players on the world stage. While the industry is home to thousands of companies, the journeys of its largest players offer a masterclass in navigating the sector’s unique challenges and opportunities. An analysis of the top companies by market capitalization reveals a landscape dominated by a few powerful, strategically diverse titans.

| Rank | Company Name | Market Cap (INR Lakh Crore) | Key Business Focus | Sources |

| 1 | Sun Pharmaceutical Industries | 3.4 | Specialty & Generics | 70 |

| 2 | Divi’s Laboratories | 1.72 | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) | 70 |

| 3 | Cipla | 1.19 | Respiratory, Generics, APIs | 70 |

| 4 | Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories | 1.10 | Generics, APIs, R&D, Specialty | 70 |

| 5 | Torrent Pharmaceuticals | 1.07 | Branded Generics (Cardiovascular, CNS) | 70 |

| 6 | Mankind Pharma | 0.95 | Branded Generics (Domestic Focus) | 70 |

| 7 | Zydus Lifesciences | 0.95 | Generics, Biologics, Vaccines | 70 |

| 8 | Lupin | 0.88 | Generics, APIs, Respiratory | 70 |

| 9 | Aurobindo Pharma | 0.62 | Generics, APIs | 70 |

| 10 | Alkem Laboratories | 0.57 | Generics (Anti-infectives) | 70 |

Note: Market capitalization figures are as of early 2025 and are approximate.

Among these leaders, the strategic paths of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries and Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories offer a compelling contrast, illustrating two distinct yet highly successful models for building a global pharmaceutical giant from India: one built on aggressive acquisition and scale, the other on a pioneering commitment to research and innovation.

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries: The Architect of Scale

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, India’s largest pharmaceutical company, is a story of audacious ambition and masterful execution. Founded in 1983 by Dilip Shanghvi with a modest capital of just ₹10,000, the company’s initial strategy was remarkably focused. Instead of competing in the crowded general medicine space, Sun Pharma targeted the underserved niche of psychiatric drugs, starting with just five products.72 This sharp focus on specific therapeutic areas where competition was lower and specialization could create a defensible moat became a hallmark of its early success.

However, the defining feature of Sun Pharma’s journey to the top has been its relentless and strategic use of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) to build scale, enter new markets, and acquire new capabilities. Key milestones in its acquisition-led growth story include:

- Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories (1997): Sun Pharma’s acquisition of a controlling stake in this struggling Detroit-based generics company was its gateway into the highly regulated and lucrative US market. It was a bold move that provided a crucial foothold and understanding of the world’s largest pharmaceutical market.72

- Taro Pharmaceuticals (2007-2013): In a protracted and often hostile takeover battle, Sun Pharma eventually acquired control of this Israeli-based company. The strategic prize was Taro’s strong portfolio and expertise in dermatology, a high-value specialty segment that Sun Pharma was determined to enter.72

- Ranbaxy Laboratories (2014): The capstone of Sun Pharma’s M&A strategy was the landmark USD 4 billion all-stock acquisition of Ranbaxy Laboratories. Despite Ranbaxy’s ongoing regulatory issues with the US FDA, the deal was transformative. It instantly catapulted Sun Pharma to become the largest pharmaceutical company in India, the largest Indian pharma company in the US, and the fifth-largest specialty generic company in the world.73

Sun Pharma’s strategy exemplifies the “acquisitive consolidator” model. Its growth has been fueled by an unparalleled ability to identify undervalued assets, integrate them effectively, and leverage the combined scale to dominate the global generics market. While it has also invested in R&D and is building a specialty product portfolio, its DNA is rooted in operational excellence and inorganic growth. As founder Dilip Shanghvi has noted, this approach requires a disciplined focus on creating shareholder value:

“Whenever you look at any potential merger or acquisition, you look at the potential to create value for your shareholders.” — Dilip Shanghvi 77

Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories: The Pioneer of R&D

In contrast to Sun Pharma’s acquisition-driven path, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories represents the “aspirational innovator” model. Founded in 1984 by the visionary scientist Dr. Kallam Anji Reddy, the company began as a manufacturer of APIs for the Indian market. However, from its inception, Dr. Reddy’s harbored a far more ambitious vision: to become a discovery-led global pharmaceutical company, often described as aspiring to be the “Merck or Pfizer of India”.78

This vision translated into a pioneering commitment to research and development, long before it became a strategic necessity for the broader Indian industry. Key elements of its innovation-first approach include:

- Early Investment in R&D: Dr. Reddy’s established a dedicated, non-profit research arm, the Dr. Reddy’s Research Foundation, as early as 1992. This was a clear signal of its intent to move beyond generics and into the high-risk, high-reward world of novel drug discovery.78

- First Indian NCE Out-Licensing: The company achieved a major milestone for the entire Indian industry when it became the first to discover and then out-license a New Chemical Entity (NCE), an anti-diabetic drug named balaglitazone, to Novo Nordisk for further development and commercialization.78

- A Balanced Business Model: Dr. Reddy’s has successfully managed a dual strategy. It has built a formidable and profitable global generics business, particularly in the US, which provides the financial foundation to fund its long-term R&D ambitions. This is complemented by a growing focus on specialty products, particularly in dermatology, and innovative projects like the “polypill,” which combines multiple generics into a single pill for chronic diseases.79

- Global Integration: Recognizing that a global business requires a global mindset, the company has actively invested in building a cohesive international organization, including cross-cultural training programs designed to effectively integrate its teams in India, the US, and Europe.80

The contrasting journeys of Sun Pharma and Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories highlight the two dominant strategic pathways that have defined success in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. One path prioritizes scale, operational efficiency, and market consolidation through acquisition. The other prioritizes a long-term, organic investment in R&D and a gradual climb up the innovation ladder. While both companies are now converging—with Sun Pharma investing more in specialty R&D and Dr. Reddy’s continuing to grow its generics base—their foundational strategies offer a clear illustration of the choices facing the next generation of Indian pharma companies as they chart their own courses toward global leadership.

Conclusion – India’s Prescription for the Future

The Indian pharmaceutical industry has unequivocally earned its title as the “Pharmacy of the World.” Through a unique combination of strategic government policy, scientific ingenuity in process chemistry, and an unwavering entrepreneurial spirit, it has built a global manufacturing powerhouse that serves as a lifeline for affordable medicines across the globe. The analysis presented in this report, however, makes it clear that the industry is at a pivotal moment of transition. The policy environment that catalyzed its initial rise has been replaced by a globally integrated patent regime, and the business model that guaranteed past success is no longer sufficient to secure future leadership. The industry’s next chapter will be defined by its ability to navigate profound structural challenges and execute a fundamental shift from a high-volume manufacturer to a high-value innovator.

The journey ahead requires a clear-eyed acknowledgment of the imperatives for future success. The path from a USD 50 billion industry today to a projected USD 130 billion by 2030 and a visionary USD 450 billion by 2047 is not a linear extension of past growth. It demands a new prescription for the future, built on four critical pillars:

- Embrace Quality as a Culture: The persistent challenge of meeting and exceeding global regulatory standards, particularly from the US FDA, must be the industry’s foremost priority. This requires a cultural shift that moves beyond mere compliance to embedding a “quality-first” mindset into every aspect of operations. Investment in digital quality management systems, automation to reduce human error, and continuous workforce training are no longer optional but are the price of entry for leadership in regulated markets.

- Foster a True Innovation Ecosystem: The ambition to move from “Make in India” to “Discover in India” requires a sustained, collaborative effort. While government policies like the PRIP scheme provide crucial support, companies must commit to the long-term, high-risk, and capital-intensive journey of novel drug discovery. This involves not only increasing R&D spending but also forging deeper partnerships between industry, academia, and a growing ecosystem of biotech startups to translate scientific research into clinical breakthroughs. The capabilities being built in the biosimilars space serve as an essential bridge, creating the technical and regulatory expertise needed for this leap.

- Build Strategic Resilience in the Supply Chain: The critical dependence on China for APIs and KSMs remains the industry’s most significant vulnerability. While the PLI schemes are a vital step towards de-risking the supply chain, achieving true self-reliance is a long-term goal. This requires a concerted strategy involving continued government support, private investment in large-scale, environmentally sustainable manufacturing, and a focus on developing cost-competitive production technologies, particularly in fermentation-based APIs. Securing the pharmaceutical supply chain is not just an economic objective; it is a matter of national health security.

- Invest in Future-Ready Talent: The strategic pivot towards biologics, specialty drugs, and digital transformation necessitates a new generation of talent. The industry faces a growing need for skilled professionals in areas such as biotechnology, data science, artificial intelligence, and global regulatory affairs. Proactive investment in skill development programs, partnerships with academic institutions, and creating an environment that attracts and retains top global talent will be crucial for executing the industry’s value-driven strategy.

The Indian pharmaceutical industry’s legacy is one of remarkable achievement. Its future will be determined by its ability to transform. By strategically addressing its vulnerabilities in quality and supply chain resilience, while simultaneously doubling down on the immense opportunities presented by the patent cliff, biosimilars, and digital innovation, the industry is well-positioned to write its next chapter. The journey from the “Pharmacy of the World” to the world’s “Laboratory and Innovation Hub” is ambitious but achievable. It is this transformation that will not only fuel the industry’s economic growth but also solidify India’s role as an indispensable and leading partner in advancing global health for decades to come.

Key Takeaways

- Dominant Market Position with a Strategic Challenge: The Indian pharmaceutical industry is a global powerhouse, ranking 3rd by volume and valued at approximately USD 50-65 billion in 2024. However, its 13th/14th rank by value highlights the core strategic challenge: transitioning from a high-volume, low-cost generics producer to a high-value, innovation-driven leader to meet its ambitious growth target of USD 130 billion by 2030.

- Policy-Driven Historical Growth: The industry’s rise was not accidental but a direct result of the 1970 Patents Act, which abolished product patents and enabled a thriving reverse-engineering model for generics. The subsequent 2005 TRIPS-compliant amendment forced a crucial pivot towards global competition, R&D, and export-led growth.

- A Unique and Protective Regulatory Framework: India balances global IP norms with public health needs through a multi-layered system. Section 3(d) prevents “evergreening” of patents, the DPCO controls essential medicine prices, and Compulsory Licensing acts as a final safety net against inaccessible drugs. The mere threat of these provisions shapes corporate strategy in the region.

- Critical Supply Chain Vulnerability: A heavy dependence on China for approximately 70% of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) poses a significant geopolitical and supply chain risk. Government Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes are a major strategic initiative to bolster domestic manufacturing and achieve self-reliance.

- Persistent Quality and Compliance Hurdles: Despite having the most US FDA-approved plants outside the US, the industry faces persistent scrutiny. Recurring warning letters related to data integrity, quality control failures, and inadequate process controls remain a significant challenge to its global reputation and operational stability.

- The Impending Patent Cliff is a Massive Opportunity: The expiration of patents on drugs worth over USD 250 billion by 2030 represents the single largest growth driver for Indian generic and biosimilar manufacturers. Capitalizing on this requires sophisticated competitive intelligence, regulatory agility, and a focus on complex, high-barrier-to-entry products.

- Biosimilars and Digitalization are the Future Growth Engines: The industry’s future growth is increasingly tied to high-value segments like biosimilars, where India is already a global leader in approvals. Simultaneously, the adoption of AI and digital technologies is becoming essential to accelerate R&D, enhance manufacturing quality, and maintain a competitive edge.

- The Ultimate Strategic Imperative: The core mission for the next decade is the transformation from “Make in India” to “Discover in India.” This involves moving up the value chain from being the world’s manufacturer of affordable medicines to becoming a source of novel, innovative therapies for global health challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What was the single most important factor in the rise of the Indian pharmaceutical industry?

The single most important factor was the Indian Patents Act of 1970. This landmark legislation fundamentally altered the country’s intellectual property landscape for pharmaceuticals by abolishing product patents and recognizing only process patents for a shorter duration. This policy intentionally and legally enabled Indian companies to “reverse engineer” patented drugs, developing alternative manufacturing processes to produce affordable generic versions without paying royalties. This act catalyzed the growth of a robust domestic generics industry, transforming India from a net importer of high-cost medicines into a self-sufficient and eventually a world-leading exporter of affordable drugs.

2. Why is India so dependent on China for pharmaceutical raw materials (APIs)?

India’s dependence on China for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) is a phenomenon that developed primarily after the economic liberalization of the 1990s. Chinese API manufacturers, benefiting from significant government support, economies of scale, and lower operational and environmental compliance costs, were able to produce and export APIs at prices that were substantially cheaper than domestic Indian production. As Indian pharmaceutical companies focused on the high-volume, low-cost production of finished drug formulations, it became more economically viable for them to import these cheaper raw materials from China rather than manufacture them in-house. Over time, this led to the erosion of India’s domestic API manufacturing base and created the current state of high dependency, with around 70% of APIs being imported from China.

3. What is Section 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act, and why is it so controversial?

Section 3(d) is a unique provision in India’s patent law designed to prevent the “evergreening” of patents on medicines. It states that a new form of a known substance is not patentable unless it demonstrates a significant “enhancement of the known efficacy.” The Indian Supreme Court has interpreted this to mean enhanced therapeutic efficacy—a tangible improvement in how the drug treats a disease. The provision is controversial because it sets a higher bar for patentability for incremental innovations than in many Western countries. Innovator pharmaceutical companies argue that it stifles legitimate, incremental R&D and discourages investment. Conversely, public health advocates and generic manufacturers champion it as a crucial safeguard that prevents weak patents from extending monopolies, thereby ensuring timely access to more affordable generic medicines.

4. How are Indian pharma companies preparing for the upcoming “patent cliff”?

Indian pharmaceutical companies are employing a multi-pronged strategy to capitalize on the “patent cliff,” where blockbuster drugs worth over USD 250 billion will lose patent protection by 2030. Key strategies include:

- Competitive Intelligence: Using specialized services and platforms like DrugPatentWatch to meticulously track patent expiration dates and litigation outcomes to identify the most lucrative opportunities early.

- Focus on Complexity: Shifting R&D focus from simple generics to more complex products like biosimilars, specialty generics, and novel drug delivery systems, which have higher barriers to entry and better profit margins.

- First-to-File (FTF) Strategy: Aggressively pursuing the 180-day market exclusivity in the US by being the first to file a generic drug application with a patent challenge.

- Regulatory and Manufacturing Agility: Streamlining regulatory processes and ensuring manufacturing readiness to enable a rapid “speed-to-market” launch as soon as a patent expires, which is crucial for capturing market share before prices decline.

5. What does the future look like for the Indian pharma industry? Is it moving beyond generics?

The future of the Indian pharmaceutical industry is one of strategic evolution from a volume-based to a value-based model. While the production of generics will remain a strong and essential foundation, the primary drivers of future growth are shifting. The industry is aggressively moving “beyond generics” into higher-value segments. This includes becoming a global leader in biosimilars, expanding into complex specialty drugs, and increasing investment in original R&D with the long-term goal of discovering novel drugs. This transition is being accelerated by the widespread adoption of digital technologies and AI to enhance R&D productivity and manufacturing quality. The ultimate vision is for India to transform from being just the “Pharmacy of the World” to also being a key “Laboratory and Innovation Hub for the World.”

Works cited

- Drugs & Pharmaceuticals Industry – India Market – Brickwork Ratings, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.brickworkratings.com/Research/Drugsand%20Pharmaceuticals%20Industry-India-Nov2024.pdf

- India: The World’s Pharmacy – PIB, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressNoteDetails.aspx?NoteId=152038&ModuleId=3

- Indian Pharmaceutical Industry: Creating Global Impact, accessed August 28, 2025, https://ispe.org/pharmaceutical-engineering/march-april-2025/indian-pharmaceutical-industry-creating-global-impact

- India’s pharmaceutical market for FY 2023-24 is valued at USD 50 billion with domestic consumption valued at USD 23.5 billion and export valued at USD 26.5 billion – Press Release: Press Information Bureau, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2085345

- Indian pharma sector third largest globally, valued at $50 billion in FY 2023-24: Centre, accessed August 28, 2025, https://ddnews.gov.in/en/indian-pharma-sector-third-largest-globally-valued-at-50-billion-in-fy-2023-24-centre/

- Pharmaceutical industry in India – Wikipedia, accessed August 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmaceutical_industry_in_India

- Why India’s Pharmaceutical Industry Remains Poised for Growth in 2025 – Invest UP, accessed August 28, 2025, https://invest.up.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/go/pressnews31012025-3.pdf

- Pharma Industry in India: An Outlook for 2025-2030, accessed August 28, 2025, https://indiaemployerforum.org/world-of-work/pharma-industry-in-india-2025-2030/

- India Pharmaceutical Market Size, Share and Growth, 2033, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.imarcgroup.com/india-pharmaceutical-market

- India Pharmaceutical Market Size & Outlook, 2024-2030, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/horizon/outlook/pharmaceutical-market/india

- Pharma Industry – Department of Pharmaceuticals, accessed August 28, 2025, https://pharma-dept.gov.in/pharma-industry-promotion

- BOOSTING INDIA’S PHARMACEUTICAL EXPORTS – CII, accessed August 28, 2025, https://cii.in/International_ResearchPDF/CII%20Report%20Boosting%20Pharma%20Exports%20Feb%202022.pdf

- The Indian Pharmaceutical Industry: A Remarkable Journey …, accessed August 28, 2025, https://health.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/pharma/the-indian-pharmaceutical-industry-a-remarkable-journey/103303320

- A short history of Indian pharma – dandc.eu, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.dandc.eu/en/article/how-government-action-helped-indias-pharma-sector-grow

- India’s Way to Pharma Powerhouse by 2047 – EY, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.ey.com/en_in/insights/health/what-will-it-take-for-india-to-become-a-global-pharma-powerhouse-by-2047

- Pharmaceutical Exports from India – IBEF, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.ibef.org/exports/pharmaceutical-exports-from-india

- The Bazaar and the Indigenous Pharmaceuticals Industry – Disparate Remedies – NCBI, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592786/

- Evolution of Indian Pharmaceutical Industry – Overview – IPS Academy, Indore, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.ipsacademy.org/unnayan/splvsep2019/Chapter13.pdf

- The new patent regime: Implications for patients in India – PMC, accessed August 28, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2900001/

- Five Years into the Product Patent Regime: India’s Response, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.undp.org/india/publications/five-years-product-patent-regime-indias-response

- A “Calibrated Approach”: Pharmaceutical FDI and the Evolution of Indian Patent Law – United States International Trade Commission, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/journals/pharm_fdi_indian_patent_law.pdf

- The Emergence of India’s Pharmaceutical Industry and Implications for the U.S. Generic Drug Market – USITC, accessed August 28, 2025, http://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/EC200705A.pdf

- The Global Significance of India’s Pharmaceutical Patent Laws, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.aipla.org/list/innovate-articles/the-global-significance-of-india-s-pharmaceutical-patent-laws

- Indian Patent Law Section 3d: Preventing Evergreening & True Innovation, accessed August 28, 2025, https://thelegalschool.in/blog/indian-patent-law-section-3d

- Indian Pharmaceutical Patent Prosecution: The Evolving Role of Section 3(d), accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/indian-pharmaceutical-patent-prosecution-the-changing-role-of-section-3d/

- Compulsory Licensing – does it affect the pharma companies? – IndiaBioscience, accessed August 28, 2025, https://indiabioscience.org/columns/opinion/compulsory-licensing-does-it-affect-the-pharma-companies

- How to overcome Section 3(d) Objections ? – Stratjuris Law Partners, accessed August 28, 2025, https://stratjuris.com/how-to-overcome-section-3d-objections/

- Indian pharmaceutical patent prosecution: The changing role of Section 3(d) – PMC, accessed August 28, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5880378/

- Relooking at the reach of Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970 – asialaw, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.asialaw.com/NewsAndAnalysis/relooking-at-the-reach-of-section-3d-of-the-indian-patents-act-1970-after-nov/Index/1854

- Impact of price control on pharmaceutical sector with reference to India – ResearchGate, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339351822_Impact_of_price_control_on_pharmaceutical_sector_with_reference_to_India

- Impact of the Drug Price Control Order on the pharma industry, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.projectguru.in/impact-of-the-drug-price-control-order-on-the-pharma-industry/

- a review article on drug price control order implementations, impacts and flaws, accessed August 28, 2025, https://ijbpas.com/pdf/2023/July/MS_IJBPAS_2023_7288.pdf

- Evaluating the impact of price regulation (Drug Price Control Order 2013) on antibiotic sales in India: a quasi-experimental analysis, 2008–2018, accessed August 28, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9587621/

- Does Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Result in Greater Access to Essential Medicines? – IIM Ahmedabad, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.iima.ac.in/sites/default/files/rnpfiles/2217512512016-02-01.pdf

- The Indian Case Study of Compulsory Licensing – ResearchGate, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355124197_The_Indian_Case_Study_of_Compulsory_Licensing

- Compulsory Licenses: The Dangers Behind the Current Practice – Scholarship @ Hofstra Law, accessed August 28, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1107&context=jibl&httpsredir=1&referer=

- First compulsory license – Nishith Desai Associates, accessed August 28, 2025, http://www.nishithdesai.com/fileadmin/user_upload/pdfs/First_Compulsory_License_Likely_to_impact_the_pharmaceutical_industry_in_India.pdf

- India’s First Compulsory License: Its Impact on the Indian Pharmaceutical Market as well as the World Market – PICMET, accessed August 28, 2025, http://www.picmet.org/db/member/proceedings/2014/data/papers/14R0187.pdf

- Compulsory Licensing of Pharmaceutical Patents in India: Issues and Challenges – National Law University, Nagpur, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.nlunagpur.ac.in/PDF/Publications/5-Current-Issue/1.%20COMPULSORY%20LICENSING%20OF%20PHARMACEUTICAL%20PATENTS%20IN%20INDIA.pdf

- Can India Reclaim API Throne from China? – BioSpectrum India, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.biospectrumindia.com/features/73/25074/can-india-reclaim-api-throne-from-china.html

- India’s Reliance On China For Pharmaceutical Ingredients | PDF – Scribd, accessed August 28, 2025, https://de.scribd.com/document/694897844/INDIA-S-RELIANCE-ON-CHINA-FOR-PHARMACEUTICAL-INGREDIENTS

- India’s Import Dependence on China in Pharmaceuticals: Status …, accessed August 28, 2025, https://ris.org.in/sites/default/files/Publication/DP%20268%20Prof%20Sudip%20Chaudhuri.pdf

- India as the world’s pharmacy: Becoming self-reliant – ET Edge Insights, accessed August 28, 2025, https://etedge-insights.com/industry/healthcare/india-to-reduce-china-dependency-to-consolidate-worlds-pharmacy-title/

- Review: Government body calls for self-reliance in Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), accessed August 28, 2025, https://factly.in/review-government-body-calls-for-self-reliance-in-active-pharmaceutical-ingredients-apis/

- Pharmaceutical Sector Spotlight: Driving Innovation in India – Invest India, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.investindia.gov.in/blogs/pharmaceutical-sector-spotlight-driving-innovation-india

- India struggling to free pharma industry from dependence on Chinese APIs | Policy Circle, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.policycircle.org/industry/apis-import-depencence-on-china/

- Investing in India’s Pharmaceutical Industry: Key Growth Prospects – India Briefing, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.india-briefing.com/news/why-indias-pharmaceutical-industry-remains-poised-for-growth-in-2025-35988.html/

- Trends In FDA FY2023 Inspection-Based Warning Letters, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.outsourcedpharma.com/doc/trends-in-fda-fy2023-inspection-based-warning-letters-0001

- Granules India Limited MARCS-CMS 697115 — February 26, 2025 – FDA, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/granules-india-limited-697115-02262025

- Kilitch Healthcare India Limited – 672956 – 03/28/2024 – FDA, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/kilitch-healthcare-india-limited-672956-03282024

- Indoco Remedies Limited – 691594 – 12/16/2024 – FDA, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/indoco-remedies-limited-691594-12162024

- As patent cliff nears, Indian pharma must prioritize speed towards market & regulatory agility: Akash Kedia – Pharmabiz.com, accessed August 28, 2025, https://pharmabiz.com/PrintArticle.aspx?aid=180807&sid=1

- What are Patent Cliffs and How Pharma Giants Face Them in 2024 – PatentRenewal.com, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.patentrenewal.com/post/patent-cliffs-explained-pharmas-strategies-for-2024-losses

- Big Pharma prepare for next patent cliff as blockbuster drugs revenue losses loom: GlobalData, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.expresspharma.in/big-pharma-prepare-for-next-patent-cliff-as-blockbuster-drugs-revenue-losses-loom-globaldata/

- An Analysis on leveraging the patent cliff with drug sales worth USD 251 billion going off-patent and analysis of different drug – Department of Pharmaceuticals, accessed August 28, 2025, https://pharma-dept.gov.in/sites/default/files/FINAL-An%20analysis%20on%20leveraging%20the%20patent%20cliff.pdf

- AI-Powered Business Intelligence Applications in Pharma | IntuitionLabs, accessed August 28, 2025, https://intuitionlabs.ai/articles/ai-bi-pharmaceutical-applications

- 25 Transformative Years of Biosimilars – BioSpectrum India, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.biospectrumindia.com/features/18/26042/25-transformative-years-of-biosimilars.html

- India: The emerging hub for biologics and biosimilars – BIRAC, accessed August 28, 2025, https://birac.nic.in/webcontent/Knowledge_Paper_Clarivate_ABLE_BIO_2019.pdf

- India Biosimilar Market Size, Companies and Growth, 2033 – IMARC Group, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.imarcgroup.com/india-biosimilar-market

- Why India must turn Biosimilar Powerhouse by 2030, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.biospectrumindia.com/features/73/24947/why-india-must-turn-biosimilar-powerhouse-by-2030.html

- AI-driven drug discovery, precision medicine, and sustainable manufacturing can redefine the pharma industry, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.expresspharma.in/ai-driven-drug-discovery-precision-medicine-and-sustainable-manufacturing-can-redefine-the-pharma-industry/

- India Pharmaceutical Adopting Automation Technologies – ARC Advisory Group, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.arcweb.com/industry-best-practices/india-pharmaceutical-adopting-automation-technologies

- From volume to value: Indian pharma’s transformation with data and AI | EY, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.ey.com/content/dam/ey-unified-site/ey-com/en-in/insights/health/ey-from-volume-to-value-indian-pharma-s-transformation-with-data-and-ai.pdf

- How GenAI is revolutionizing the pharmaceutical industry | EY – India, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.ey.com/en_in/insights/health/how-gen-ai-is-revolutionizing-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- Digital tools are helping Indian pharma companies but some are lagging, accessed August 28, 2025, https://pharma.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/pharmatech/digital-transformation-in-indian-pharma-the-race-between-progress-and-resistance/123252842

- How AI Will Impact the Indian Pharmaceutical Industry. Everything You Need to Know, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.equitymaster.com/timeless-reading/how-ai-will-impact-the-indian-pharmaceutical-industry-everything-you-need-to-know

- Digital transformation in pharma manufacturing, accessed August 28, 2025, https://manufacturing.economictimes.indiatimes.com/videos/digital-transformation-in-pharma-manufacturing/122875563

- Driving Digital Engagement for a Chronic Care Program with Tech-Led Pharma Marketing, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.valuebound.com/case-study/driving-digital-engagement-chronic-care-program-tech-led-pharma-marketing

- A Case Study on Pharmaceutical Sector: Indian Context – Applied Science and Biotechnology Journal for Advanced Research, accessed August 28, 2025, https://abjar.vandanapublications.com/index.php/ojs/article/download/83/212/209

- Top 10 pharma companies in India by market cap [2025], accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.forbesindia.com/article/explainers/top-10-pharma-companies-market-cap/92817/1

- Top 10 Pharma Companies in India by Market Capitalization – GlobalData, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.globaldata.com/companies/top-companies-by-sector/healthcare/india-companies-by-market-cap/

- The Rise Of Sun Pharma – Dilip Shanghvi, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.pharmanow.live/pharma-untold-stories/the-rise-of-sun-pharma-ft-dilip-shanghavi

- From Modest Beginnings to Pharma Giant: The Inspiring Journey of Dilip Shanghvi and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries – Sovrenn, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.sovrenn.com/knowledge/from-modest-beginnings-to-pharma-giant-the-inspiring-journey-of-dilip-shanghvi-and-sun-pharmaceutical-industries

- View of A Story of Sun Pharmaceuticals Laboratories: Going Global, accessed August 28, 2025, https://socialscienceresearch.org/index.php/GJHSS/article/view/2513/1-A-Story-of-Sun-Pharmaceuticals_html

- Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd| Founder, History, and Mergers – Shoonya Blogs, accessed August 28, 2025, https://blog.shoonya.com/sun-pharmaceutical-industries-ltd/

- Dilip Shanghvi – Wikipedia, accessed August 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dilip_Shanghvi

- 15 inspiring quotes by Dilip Shanghvi, the man who built India’s most valuable pharma company | YourStory, accessed August 28, 2025, https://yourstory.com/2020/03/inspiring-quotes-dilip-shanghvi-sun-pharmaceuticals

- Innovating India’s Pharmaceutical Industry – WIPO, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/ip-advantage/w/stories/innovating-india-s-pharmaceutical-industry

- Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories: Realizing an ambitious vision – IMD business school for management and leadership courses, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.imd.org/research-knowledge/strategy/case-studies/dr-reddy-s-laboratories-realizing-an-ambitious-vision/

- Case Study | Learnlight, accessed August 28, 2025, https://learnlight.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/DrReddys_CaseStudy_EN.pdf