The High-Stakes Chess Match: A Strategic Guide to Handling Drug Patent Invalidity Claims

In the world of pharmaceuticals, a patent is more than just a legal document; it’s the foundational asset upon which entire companies are built. It represents the culmination of billions of dollars in research and development, years of painstaking clinical trials, and the promise of market exclusivity that makes such staggering investment possible. But what happens when that foundation develops a crack? What happens when a competitor, a government body, or a public interest group claims that your crown-jewel patent is, in fact, invalid?

This is not a peripheral risk; it is a central, unavoidable feature of the pharmaceutical landscape. Handling drug patent invalidity claims is one of the highest-stakes games of corporate chess you will ever play. A successful challenge can evaporate a blockbuster drug’s market protection overnight, wiping out billions in revenue and opening the floodgates to generic competition. Conversely, for a generic or biosimilar manufacturer, a successful invalidity claim is the key that unlocks a lucrative market, delivering affordable medicines to patients and generating substantial returns.

This report is not a legal textbook. It is a strategic guide for you, the business professional, the C-suite executive, the portfolio manager, and the in-house counsel. Our goal is to move beyond the dense legalese and provide a clear, actionable framework for understanding and leveraging patent invalidity. We will explore this topic not as a reactive legal problem to be managed, but as a proactive strategic tool for shaping markets, mitigating risk, and securing a decisive competitive advantage.

The entire patent system is built on a delicate “patent bargain”. In exchange for an inventor teaching the public how to make and use their new and useful invention, the government grants a temporary monopoly. Invalidity proceedings are the ultimate check on this bargain. They are the system’s built-in quality control mechanism, ensuring that the immense power of a patent monopoly is granted only to inventions that are truly novel, non-obvious, and adequately disclosed.5 This process prevents the system from being stifled by weak patents or “rent-seeking behavior” where companies extend monopolies without providing genuine innovation.

Therefore, your ability to navigate these proceedings—whether you are on the offense, seeking to clear a path to market, or on the defense, protecting your most valuable assets—is a core business competency. Over the course of this report, we will dissect the grounds for invalidity, map the complex procedural battlefields in the U.S. and Europe, and lay out a strategic playbook for both challengers and patent holders. We will arm you with the insights needed to turn the complex, often intimidating world of patent law into a powerful engine for your company’s success. Let the match begin.

The Anatomy of a Drug Patent Challenge: Core Grounds for Invalidity

Before you can devise a winning strategy, you must first understand the weapons at your disposal—or those being aimed at you. A patent invalidity claim is not a vague accusation; it is a precision strike targeted at a specific, legally defined vulnerability in the patent. These vulnerabilities, or “grounds for invalidity,” are the fundamental rules of the patent game. While the specific language may differ between jurisdictions like the United States and Europe, the core principles are universal. They all boil down to a few critical questions: Was the invention truly new? Was it a genuine inventive leap? And did the inventor teach the public enough in return for the monopoly they received? Let’s dissect the legal toolkit used to dismantle a drug patent.

Lack of Novelty (Anticipation): The “Is It Truly New?” Test

The most fundamental requirement for any patent is novelty. An invention simply cannot be patented if it already exists in the public domain.1 This concept, known in U.S. law as “anticipation” under 35 U.S.C. § 102 and in European law under Article 54 of the European Patent Convention (EPC), is the first and most direct line of attack against a patent’s validity.8

At its core, the novelty test is straightforward: a patent claim is invalid if a single piece of “prior art” discloses each and every element of the claimed invention.4 This prior art can be a previously issued patent, a scientific journal article, a conference presentation, a product that was publicly used or sold, or any other information made available to the public before the patent’s effective filing date. Under the America Invents Act (AIA) in the U.S., this is a global standard; a disclosure anywhere in the world can be used to invalidate a U.S. patent.

For a challenger, finding such a “silver bullet” reference that explicitly lays out the entire invention is the dream scenario. It’s a clean, powerful argument. However, the battleground for novelty in the pharmaceutical space is often more nuanced, centering on what is implicitly disclosed.

The Doctrine of Inherent Anticipation

This is where things get interesting, and strategically vital. The doctrine of inherent anticipation holds that even if a specific property or outcome of a claimed invention is not explicitly mentioned in a prior art reference, the patent can still be invalid for lack of novelty if that property is the natural and inevitable result of something that is described in the prior art.

Imagine an innovator patents the use of Compound X to treat Alzheimer’s disease. A generic challenger may not need to find a scientific paper that says, “Compound X is effective for Alzheimer’s.” Instead, they might find an older publication that fully describes the chemical structure and synthesis of Compound X, but for a different purpose, or for no specific purpose at all. If the challenger can then prove, through expert testimony and new experimental data, that administering Compound X as described in that old paper inherently and necessarily results in the treatment of Alzheimer’s, the new patent can be invalidated. The Federal Circuit has repeatedly affirmed that the discovery of a “previously unappreciated property of a prior art composition” does not make that old composition new again.

This doctrine is a potent weapon against “evergreening” strategies, where companies seek to extend patent life by patenting new uses, formulations, or polymorphs of existing drugs.7 For example, demonstrating the novelty of a new crystalline form (polymorph) of a known drug can be exceptionally difficult if that polymorph was likely, even if unknowingly, created in prior art experiments. For challengers, this dramatically expands the universe of searchable prior art and provides a powerful avenue to attack patents that may appear novel on the surface.

Obviousness (Lack of Inventive Step): The “Would a Skilled Person Have Thought of That?” Test

If lack of novelty is a sniper’s shot, obviousness is an artillery barrage. It is, by far, the most common, most complex, and most frequently successful ground for invalidating a drug patent.1 While an invention might be technically new—meaning no single prior art reference discloses it entirely—it may still be unpatentable if the differences between the invention and the prior art are so trivial that they would have been “obvious” to a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (a POSITA) at the time the invention was made.9 In Europe, this is known as the “inventive step” requirement.10

The POSITA is a legal fiction, a hypothetical person who is presumed to know all of the relevant prior art in a specific field. They are a typical scientist or engineer in that domain—not a genius, but someone with standard knowledge and creativity.4 The core question is whether this hypothetical skilled person, faced with a problem, would have been motivated to combine existing pieces of prior art to arrive at the claimed invention with a reasonable expectation of success.

In the U.S., this analysis is guided by a set of factual inquiries established in the landmark Supreme Court case Graham v. John Deere Co. :

- Determining the scope and content of the prior art: What was already known in the field?

- Ascertaining the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art: What is actually new?

- Resolving the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art: How much knowledge and skill should our hypothetical POSITA have?

The Impact of KSR v. Teleflex

For decades, the test for obviousness was quite rigid. Courts required a specific “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” (TSM) in the prior art to combine references. A challenger had to find something in the literature that explicitly suggested putting Piece A together with Piece B.

That all changed with the 2007 Supreme Court decision in KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc.. The Court rejected the rigid TSM test in favor of a more flexible, expansive, and common-sense approach. It recognized that innovation is not always a flash of genius; it can also be the product of ordinary skill, predictable variations, and common sense. If a technique is known to improve one device, using it to improve a similar device in the same way is likely obvious.

This decision had a seismic impact on the pharmaceutical industry. The field is rife with structurally similar compounds, where small molecular modifications are a routine part of drug discovery. Post-KSR, it became much easier for a challenger to argue that modifying a known compound in a predictable way (e.g., swapping one halogen for another) would have been obvious to a medicinal chemist, even without an explicit suggestion in the prior art to do so.

The “Obvious to Try” Doctrine

This leads directly to the “obvious to try” doctrine, a frequent battleground in pharma patent litigation. A challenger might argue that even if the success of a particular experiment wasn’t guaranteed, it was “obvious to try” a limited number of predictable solutions with a reasonable expectation of success.4 For example, if the prior art identified a lead compound and a known problem (like poor bioavailability), and there were only a few well-known methods to address that problem, a court might find it obvious to try those methods. The key is not whether the path was long or expensive, but whether it required a true inventive leap or was simply a matter of routine, albeit laborious, experimentation.

Secondary Considerations of Non-Obviousness: The Patent Holder’s Shield

Faced with a formidable obviousness attack, what is a patent holder to do? Their most powerful defense lies in “secondary considerations,” also known as objective indicia of non-obviousness. This is real-world evidence that the invention was, in fact, not so obvious. As the Supreme Court noted in Graham, these factors can be crucial in guarding against the use of hindsight to stitch together an obviousness argument.

Common secondary considerations include 13:

- Commercial Success: The invention is embodied in a product that has achieved significant success in the market.

- Long-Felt But Unsolved Need: The invention solved a problem that had vexed the industry for a long time.

- Failure of Others: Other skilled researchers tried and failed to solve the same problem.

- Unexpected Results: The invention produced a surprising or superior result that would not have been predicted from the prior art.

- Industry Praise and Copying: The invention was lauded by experts in the field, or competitors quickly moved to copy it.

However, simply presenting this evidence is not enough. The patent holder must establish a clear nexus between the evidence and the novel features of the claimed invention.16 This is a critical and often difficult hurdle. For example, to prove commercial success, it’s not enough to show that your drug sold well. You must prove that it sold well

because of the patented inventive feature, and not because of other factors like superior marketing, brand loyalty, or features that were already known in the prior art. If a product’s success is due to an unclaimed feature, or a feature that was already old, that success is irrelevant to the non-obviousness inquiry. Establishing this nexus requires specific, compelling evidence, often in the form of sales and market data, paired with expert testimony.

The flexibility of the post-KSR obviousness standard, which allows challengers to weave together multiple prior art references into a compelling narrative, has made it the most successful ground for invalidating patents at trial. This reality dictates strategy for both sides. For a challenger, an obviousness claim is the primary weapon. For a patent holder, a robust defense built around strong, nexus-proven secondary considerations is not just an option; it is an absolute necessity.

Insufficient Disclosure: The “Did You Teach the Public Enough?” Test

The patent bargain requires the inventor to provide a full and clear disclosure of the invention in exchange for their temporary monopoly. If the patent fails to uphold its end of this bargain, it can be invalidated for insufficient disclosure. This ground for invalidity has two main prongs in the U.S. under 35 U.S.C. § 112, with a similar concept of “sufficiency of disclosure” existing in Europe under Article 83 EPC.9

- Written Description: The patent specification must describe the invention in enough detail to demonstrate that the inventor was in “possession” of the full scope of what they are claiming at the time they filed the application.8 This requirement prevents inventors from filing a patent early with a narrow discovery and then later trying to claim a much broader invention that they hadn’t actually conceived of yet. Challenges often arise when the claims are broader than the supporting text, or when key features are claimed but not adequately described.

- Enablement: This is the heart of the patent bargain. The specification must teach a POSITA how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without “undue experimentation”.1 If the disclosure is too vague or incomplete for a skilled person to replicate the invention, the patent is invalid. The amount of experimentation that is considered “undue” is a sliding scale, depending on factors like the complexity of the art, the amount of guidance in the patent, and the breadth of the claims.

For years, these requirements were a standard part of patent litigation, but they were thrust into the spotlight by a recent Supreme Court decision that has shaken the foundations of biologic patenting.

The Amgen v. Sanofi Earthquake

The 2023 Supreme Court case Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi has fundamentally reshaped the enablement landscape, particularly for patents on antibodies and other biologics that are often claimed by their function rather than their specific structure.19

The case involved Amgen’s patents for a class of antibodies that lower cholesterol by binding to the PCSK9 protein. Rather than claiming only the specific antibody sequences they had discovered, Amgen’s patents claimed the entire genus of antibodies that perform a specific function: (1) binding to a particular spot on the PCSK9 protein, and (2) blocking it from doing its job.20 This could potentially cover millions of different antibody sequences.22

Amgen argued that even though it had only disclosed the structures of 26 specific antibodies, its patent provided a “roadmap” for skilled scientists to discover other antibodies that would also work.22 Sanofi, a competitor with its own PCSK9 antibody, argued that this was not enough. Finding other working antibodies still required extensive, trial-and-error experimentation, making Amgen’s “roadmap” more of a “hunting license”.

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court sided with Sanofi.19 Justice Gorsuch, writing for the Court, articulated a simple but powerful principle: “

The more you claim, the more you must enable“.20 The Court held that if you claim an entire functional class of molecules, you must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the

full scope of that class. Providing a few examples and a method for trial-and-error discovery is not sufficient.

The impact of this decision cannot be overstated. The very nature of modern biologic drug discovery—which often focuses on identifying a biological target and a desired function—is now in direct tension with this heightened enablement standard. For biosimilar challengers, Amgen has opened up a powerful new line of attack against the broad genus patents that protect many blockbuster biologic drugs. For innovators, it has created a strategic crisis, forcing a rethink of patent filing strategy. The old approach of filing early with broad functional claims is now fraught with peril. The new imperative is to provide more concrete examples, file narrower “species” claims, and potentially delay filing until more data is available to support a broader claim scope.

Other Fatal Flaws: The Procedural and Technical Knockouts

Beyond the “big three” of novelty, obviousness, and disclosure, several other grounds can be used to invalidate or render a patent unenforceable. While less common, these can be just as fatal to a patent’s life.

- Patent Ineligible Subject Matter (35 U.S.C. § 101): U.S. law prohibits patenting “laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas”.9 This has become a major battleground for patents related to diagnostic methods and personalized medicine. A claim that simply correlates a genetic marker with a disease risk, for example, may be challenged as an unpatentable natural phenomenon.

- Incorrect Inventorship: A patent must correctly name all of the true inventors. Intentionally adding a non-inventor (perhaps a department head as a courtesy) or omitting a true contributor can be grounds for invalidation.2 While honest mistakes can often be corrected, deliberate misrepresentation is a serious flaw.

- Inequitable Conduct: This is a defense that accuses the patent applicant of acting in bad faith during prosecution. If it can be proven that the applicant intentionally withheld material information (like a crucial piece of prior art) from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) or deliberately misled the examiner with an intent to deceive, a court can declare the patent permanently unenforceable.2 The bar for proving inequitable conduct is very high, requiring clear evidence of both materiality and intent to deceive. However, when successful, it is a devastating blow to the patent holder, as we will see in the

Gilead v. Merck case study. - Indefiniteness: The patent’s claims must “particularly point out and distinctly claim” the invention. If the language of the claims is so ambiguous that a person skilled in the art cannot determine their scope, the patent can be invalidated for indefiniteness.

- Double Patenting: An inventor is prohibited from obtaining more than one patent for the same invention.1 This prevents an inventor from improperly extending their monopoly period.

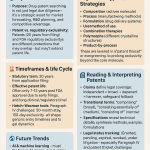

To help you navigate these complex grounds, the table below provides a high-level comparison of the primary invalidity standards in the United States and Europe.

Table 1: Key Grounds for Patent Invalidity (U.S. vs. EU)

| Feature | United States | Europe (European Patent Convention) |

| Novelty | 35 U.S.C. § 102 (Anticipation) | EPC Article 54 (Novelty) |

| Inventiveness | 35 U.S.C. § 103 (Obviousness) | EPC Article 56 (Inventive Step) |

| Disclosure | 35 U.S.C. § 112 (Written Description & Enablement) | EPC Article 83 (Sufficiency of Disclosure) |

| Subject Matter | 35 U.S.C. § 101 (Patentable Subject Matter) | EPC Articles 52 & 53 (Patentable Inventions) |

| Claim Scope | Indefiniteness (35 U.S.C. § 112(b)) | Added Subject Matter (EPC Article 123(2)) |

This table serves as a quick reference, highlighting that while the core principles are aligned, the specific statutes and legal tests differ. For any company operating globally, understanding these nuances is the first step in building a coherent, cross-jurisdictional invalidity strategy.

The U.S. Battlefield: Navigating Invalidity Claims in the World’s Largest Market

The United States is not just the largest pharmaceutical market in the world; it is also home to the most complex and high-stakes patent litigation system. For generic and biosimilar manufacturers, it is a landscape of immense opportunity, governed by a unique set of rules designed to incentivize patent challenges. For innovator companies, it is a perilous gauntlet where a single misstep can cost billions. Successfully navigating this battlefield requires a deep understanding of two parallel, and often intersecting, pathways for challenging patent validity: the highly structured dance of district court litigation under the Hatch-Waxman Act, and the streamlined, high-velocity proceedings of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

The Hatch-Waxman Gauntlet: A Dance of Litigation and Regulation

Enacted in 1984, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, is the landmark legislation that orchestrates the competitive dynamics between brand-name and generic drugs in the U.S..28 It created a brilliant, if complex, compromise: it gave generics an abbreviated pathway to market approval while offering innovators a way to restore some of the patent term lost during lengthy FDA reviews. More importantly for our purposes, it established a highly structured framework for litigating patent disputes

before a generic drug launches.

The process begins with the FDA’s “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” affectionately known as the Orange Book. When an innovator gets a new drug approved, it must list any patents that cover the drug product or its method of use in the Orange Book.

When a generic company wants to market a copy of that drug, it files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA. Instead of conducting its own costly clinical trials, the generic company need only prove its product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. As part of its ANDA, the generic must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book for the brand drug. The most critical of these is the “Paragraph IV” certification. By filing a Paragraph IV certification, the generic company attests that, in its opinion, the innovator’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.30

This certification is the starting pistol for the litigation race. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, the very act of filing an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is considered an “artificial” act of patent infringement.1 This clever legal mechanism allows the patent dispute to be resolved in court before the generic product ever hits the shelves.

Once the generic company notifies the innovator of its Paragraph IV filing, a critical clock starts ticking. The innovator (the patent holder) has 45 days to file a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant.1 If a suit is filed within this window, it triggers one of the most powerful tools in the innovator’s arsenal: an

automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic drug.1 This 30-month period provides a crucial window for the patent dispute to be litigated, all while the innovator’s market exclusivity remains intact.

So, what motivates a generic company to take this risk and invite a lawsuit? The answer is the grand prize at the end of the gauntlet: 180 days of market exclusivity.29 The

first generic company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is rewarded with a six-month period where it is the only generic version of that drug on the market. This 180-day head start can be immensely profitable, especially for a blockbuster drug, and it is the primary engine driving the entire system of patent challenges in the U.S.

This gamified system has led to a dramatic increase in patent litigation over time. The fraction of drugs subjected to Paragraph IV challenges has steadily risen, and these challenges are being filed sooner and sooner after the brand-name drug’s approval. Unsurprisingly, the data shows a strong correlation between a drug’s market value and the likelihood of it being challenged. Drugs in the highest deciles of market value face a 70-90% chance of being challenged, as the potential reward for a successful challenge is simply too large to ignore. This intense, incentive-driven environment has concentrated much of this litigation in the district courts of Delaware and New Jersey, where many pharmaceutical companies are incorporated or headquartered, creating a cadre of experienced judges who are well-versed in the unique complexities of Hatch-Waxman cases.12

The PTAB Arena: Inter Partes Review (IPR) as a Strategic Weapon

For nearly three decades, the Hatch-Waxman framework was the primary battlefield for pharmaceutical patent disputes. But in 2011, the America Invents Act (AIA) created a new, parallel arena that has fundamentally shifted the balance of power: the Inter Partes Review (IPR) proceeding before the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).35

An IPR is a trial-like proceeding designed to be a faster, cheaper, and more efficient alternative to district court litigation for resolving patent validity questions.36 However, its scope is limited. An IPR can only challenge a patent’s validity on grounds of

novelty (§ 102) and obviousness (§ 103), and only based on prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.9 Crucially, other key invalidity grounds—such as lack of enablement, insufficient written description, patent-ineligible subject matter, or inequitable conduct—cannot be raised in an IPR.9

Despite these limitations, IPRs have become a weapon of choice for patent challengers, particularly in the pharmaceutical space, for several key reasons that stack the deck in their favor:

- Lower Burden of Proof: In district court, a patent is presumed valid, and a challenger must prove invalidity by “clear and convincing evidence,” a high legal standard. In an IPR, there is no presumption of validity, and the challenger only needs to prove unpatentability by a “preponderance of the evidence”—a much lower, “more likely than not” standard.39

- Technical Expertise: An IPR is decided by a panel of three Administrative Patent Judges (APJs), who are experienced patent attorneys, often with advanced technical degrees in relevant fields like chemistry or biology. This is a stark contrast to a district court, where a case may be decided by a generalist judge and a lay jury who may struggle with complex scientific concepts.

- Speed and Cost: IPRs are designed to be swift. By statute, they must be completed within 18 months from the petition filing (6 months for the PTAB to decide whether to institute the review, and 12 months from institution to a final written decision).36 This is significantly faster than the typical 2-3 year timeline for district court litigation. The cost is also substantially lower, typically running in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, compared to the millions required for a full-blown court case.35

The result of this challenger-friendly forum has been nothing short of staggering. The invalidation rates at the PTAB are breathtakingly high.

The invalidation rate of patents in America Invents Act (AIA) proceedings, particularly inter partes reviews (IPRs), has been extremely high since the inception of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Currently, a patent reaching a final written decision in an IPR will on average have 78% of its claims found invalid. Perhaps more surprising, when there is a final written decision, 70% of the time all challenged claims in the patent are found invalid.

These statistics, which have seen the “all-claims invalidation rate” climb from 55% in 2019 to over 70% in recent years, have led to fierce debate.43 Innovator groups like PhRMA argue that IPRs disrupt the careful balance of Hatch-Waxman, create massive uncertainty for patent holders, and give challengers an unfair “second bite at the apple” by forcing innovators to defend their patents in two different forums with different rules simultaneously. Former Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit, Randall Rader, famously criticized the PTAB, suggesting its judges were acting as “death squads, killing property rights”.

On the other side, generic industry advocates and groups like the Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) argue that IPRs are working exactly as Congress intended. They contend that the process efficiently “weeds out” low-quality, improvidently granted patents that stifle competition and keep drug prices artificially high. They point to case studies showing that successful IPRs lead to dramatic and immediate price reductions for essential medicines, benefiting patients and the healthcare system as a whole.3

Regardless of where one stands in this debate, the strategic implication is undeniable. The existence of the PTAB as a high-velocity, high-probability-of-success forum has fundamentally altered the strategic calculus of pharmaceutical patent litigation.

Choosing Your Arena: A Strategic Comparison of District Court vs. IPR

For a generic manufacturer planning a Paragraph IV challenge, the question is no longer whether to litigate in district court or the PTAB, but how to strategically coordinate challenges in both forums. The decision of where, when, and how to attack is a complex one, involving a trade-off between the unique advantages and disadvantages of each venue.

- Discovery and Evidence: District court litigation involves broad, extensive, and expensive discovery, where parties can demand documents, emails, and depositions on a wide range of topics. IPRs, in contrast, have extremely limited discovery, typically confined to the cross-examination of expert declarants and the production of documents that are explicitly cited in filings. This makes IPRs less suited for challenges that rely on internal company documents, like inequitable conduct, but highly efficient for cases that turn purely on published prior art.

- Claim Construction: For years, the forums used different standards to interpret the meaning of patent claims. District courts use the “ordinary and customary meaning” standard from the Phillips case, while the PTAB used a broader “broadest reasonable interpretation” (BRI) standard, which often made it easier to find that the prior art fell within the claim’s scope. While the PTAB has now largely aligned with the Phillips standard for IPRs, its judges’ technical backgrounds can still lead to different interpretations than a generalist district court judge.

- Timeline and the Fintiv Problem: This is perhaps the most critical strategic hurdle in coordinating parallel proceedings. The 30-month Hatch-Waxman stay often sets a faster clock than the 18-month IPR process plus any appeals. This temporal mismatch created a major problem for challengers due to the PTAB’s controversial Fintiv precedent. Under Fintiv, the PTAB can use its discretion to deny institution of an IPR if a parallel district court case is scheduled to go to trial before the PTAB’s final decision would be due. This created a strategic race where innovators would push for fast trial dates in district court specifically to block a potential IPR. To mitigate this risk, challengers must now file their IPR petitions very early, often within a year of the Paragraph IV notice, and may need to make strategic stipulations, promising the court that they will not raise the same specific invalidity arguments in the court case that they are raising in the IPR, thereby reducing the overlap that is a key Fintiv factor.

- Estoppel: The stakes of an IPR are incredibly high because of its powerful estoppel provision. If a challenger loses an IPR, they are barred (or “estopped”) from raising any invalidity ground in any other forum that they raised or reasonably could have raised during the IPR.9 This means a failed IPR can cripple a challenger’s invalidity defense in the parallel district court case. This high-risk, high-reward dynamic forces challengers to put their absolute best arguments forward in the IPR petition, as they may not get a second chance.

The following table provides a clear, at-a-glance comparison of these two critical forums, distilling the key strategic factors that must be weighed when planning a U.S. patent invalidity challenge.

Table 2: Comparison of U.S. Patent Challenge Forums: District Court vs. IPR

| Feature | District Court Litigation (Hatch-Waxman) | Inter Partes Review (PTAB) |

| Available Grounds | All invalidity grounds (Novelty, Obviousness, Enablement, §101, Inequitable Conduct, etc.) | Novelty (§ 102) & Obviousness (§ 103) only, based on patents and printed publications |

| Standard of Proof | Clear and Convincing Evidence | Preponderance of the Evidence |

| Presumption of Validity | Yes, patent is presumed valid | No presumption of validity |

| Decision-Maker | Generalist Judge and/or Lay Jury | Panel of 3 technically-qualified Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) |

| Discovery | Extensive and broad (documents, depositions, etc.) | Very limited (cross-examination of declarants, cited exhibits) |

| Timeline | Typically 24-36 months to trial | 12-18 months from petition to final decision |

| Cost | High (typically $4M+ for complex pharma cases) | Lower (typically $300k – $900k) |

| Estoppel Effect | Narrow (res judicata on decided issues) | Broad (estopped from raising grounds that were or reasonably could have been raised) |

| Key Strategic Consideration | The only forum for challenges based on enablement, inequitable conduct, or non-printed prior art. | Faster, cheaper, and statistically much higher chance of success, but carries the risk of Fintiv denial and powerful estoppel if unsuccessful. |

Ultimately, the modern U.S. patent invalidity strategy is a multi-front war. The high invalidation rate and lower cost of IPRs make them an almost irresistible offensive tool for challengers, acting as a powerful lever to invalidate a patent outright or force a favorable settlement. The district court remains the essential venue for resolving issues beyond the scope of IPR and for the final determination of infringement and damages. Mastering the interplay between these two arenas is the key to victory on the U.S. battlefield.

The European Frontier: EPO Oppositions and the Unified Patent Court (UPC)

While the U.S. presents a complex dual-track system, the European patent litigation landscape has recently undergone its most significant transformation in a generation. For decades, challenging a European patent meant navigating a fragmented system of national court actions, supplemented by a highly effective but time-limited central opposition procedure at the European Patent Office (EPO). Now, the arrival of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) has introduced a powerful new venue for pan-European disputes, creating both unprecedented opportunities and existential risks for patent holders and challengers alike. Understanding the strategic interplay between the classic EPO opposition route and the new UPC is now paramount for any company with a footprint in Europe.

The Classic Route: European Patent Office (EPO) Opposition Proceedings

The EPO opposition proceeding is a long-established and highly regarded administrative process that allows any third party (except the patent owner themselves) to centrally challenge the validity of a newly granted European patent.18 It is a streamlined, cost-effective mechanism that has long been a cornerstone of European patent strategy.

The most critical feature of the EPO opposition is its timing. An opposition must be filed within a strict, non-extensible nine-month window that begins on the date the grant of the European patent is published.18 Missing this deadline is a fatal error; once the window closes, the only way to challenge the patent is through more expensive and fragmented litigation in the national courts of individual European countries (or now, in the UPC).

The grounds for an EPO opposition are precisely defined and limited by Article 100 of the EPC to three core areas 5:

- Lack of Patentability (Articles 52-57 EPC): This encompasses the familiar concepts of lack of novelty and, most commonly, lack of inventive step (the European equivalent of obviousness).

- Insufficient Disclosure (Article 83 EPC): The patent does not disclose the invention in a manner sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by a person skilled in the art. This is analogous to the U.S. enablement requirement.

- Added Subject Matter (Article 123(2) EPC): The subject matter of the granted patent extends beyond the content of the application as it was originally filed. This is a strict prohibition against applicants adding new information or broadening their invention during prosecution.

The procedure itself is handled by a three-member Opposition Division at the EPO, composed of technically qualified examiners. It begins with the opponent’s written notice of opposition, which must lay out the grounds and supporting evidence. The patentee then files a response, and the process may involve further rounds of written submissions before often culminating in oral proceedings, which are now frequently held by video conference.

The potential outcomes of an opposition are threefold 18:

- The patent is revoked entirely.

- The patent is maintained in an amended form, with the patentee narrowing the claims to overcome the opponent’s arguments.

- The opposition is rejected, and the patent is maintained as granted.

The statistics demonstrate the effectiveness of this system for challengers. In 2023, of the patents that faced opposition, 38% were revoked and another 32% were forced to be amended, meaning 70% of challenges resulted in a favorable outcome for the opponent. Given the relatively low cost—the official fee is only around €880—the EPO opposition provides an exceptionally high return on investment for challengers.

Strategically, the EPO opposition has always been a critical “first strike” weapon. The nine-month deadline creates an urgent decision point for any company monitoring a competitor’s portfolio. A robust patent monitoring service, such as that offered by DrugPatentWatch, is essential to ensure that threatening patents are identified immediately upon grant, allowing a company to make a timely and informed decision about whether to file an opposition. For decades, the choice was simple: file an opposition within the nine-month window or face a much more difficult and costly fight down the road. But now, the UPC has added a new layer of strategic complexity to this decision.

The New Game-Changer: The Unified Patent Court (UPC)

Launched on June 1, 2023, the Unified Patent Court (UPC) is a revolutionary development in European IP law.52 It is a single, international court common to (currently) 18 EU member states, created to provide a unified forum for patent litigation across a huge swath of the European market.52 Its decisions on infringement and validity have effect across all participating countries, replacing the old, patchwork system of parallel national lawsuits.

The UPC’s structure includes a Court of First Instance with a central division (split between Paris, Milan, and Munich) and several local and regional divisions spread across the member states. Cases are heard by multinational panels of legally and, crucially, technically qualified judges, bringing a high level of expertise to the proceedings.53 The system is designed for speed, with an ambitious target of delivering first-instance decisions within 12 to 14 months of a case being filed.

The strategic implications of the UPC are profound and double-edged:

- For Patent Holders (Innovators): The UPC offers an unprecedented offensive weapon. A patentee can now file a single infringement action and obtain a pan-European injunction that can halt a competitor’s product across 18 countries at once.53 Preliminary injunctions, which are often difficult to obtain in the U.S., are a very real and accessible remedy in the UPC, making it a highly attractive forum for enforcing patent rights.54

- For Challengers (Generics/Biosimilars): The UPC centralizes risk to a terrifying degree. A challenger can file a central revocation action that, if successful, can invalidate a European patent across all participating member states in a single blow. This “all or nothing” aspect makes defending a patent in the UPC a high-wire act for innovators.

Early statistics show the UPC is already a popular venue, with significant activity from both the life sciences and tech sectors.53 The German local divisions, particularly Munich and Düsseldorf, have emerged as early hotspots, leveraging their long-standing reputation for patent expertise.

The Critical Interplay Between the UPC and EPO Oppositions

The advent of the UPC has transformed the strategic meaning of an EPO opposition. What was once primarily a long-term tool for invalidating a patent has now become an immediate tactical asset in UPC litigation. This is most evident in the context of preliminary injunctions (PIs).

To grant a PI, the UPC must be satisfied that the patent in question is likely valid. A pending EPO opposition can be used by a defendant to cast doubt on that validity. Early UPC decisions, such as in Alexion v. Amgen and 10x Genomics v. NanoString, have shown that while the court will not automatically stay its own proceedings because of a parallel EPO case, it absolutely will consider the existence and strength of an opposition when weighing a PI request.

This creates a new strategic imperative. For a generic or biosimilar company, filing a strong, well-reasoned EPO opposition as soon as a competitor’s patent grants is no longer just about the eventual outcome of the opposition itself. It is a crucial defensive maneuver that can be deployed immediately in the UPC. The very existence of a credible challenge at the EPO can persuade a UPC judge that there is sufficient doubt about the patent’s validity to deny the innovator’s request for a swift, market-clearing injunction.55

This transforms European patent litigation from a series of disconnected local skirmishes into a single, integrated chess board. The move you make at the EPO today directly affects your position in a potential UPC battle tomorrow. A patent that has survived an EPO opposition will be viewed with much greater deference by a UPC judge, strengthening the patentee’s hand. Conversely, a patent facing a robust opposition is immediately on the back foot. Therefore, a modern European patent strategy requires a unified approach, where the actions taken in the EPO and the UPC are carefully coordinated to achieve a single strategic objective.

The Strategic Playbook: Turning Invalidity into Competitive Advantage

Understanding the legal grounds and procedural forums is only half the battle. The true art lies in translating that knowledge into a coherent, actionable strategy. Whether you are a challenger looking to dismantle a competitor’s monopoly or a patent holder determined to defend your fortress, success depends on a proactive, multi-faceted approach. This is not a game of passive reaction; it’s a game of deliberate, calculated maneuvers. Here, we lay out the strategic playbook for both sides of the fight.

Offensive Maneuvers: A Challenger’s Guide to Invalidating Patents

For a generic or biosimilar company, or any entity seeking freedom to operate, an invalidity challenge is the ultimate offensive weapon. It’s the key to breaking down market barriers and unlocking new revenue streams. A successful offensive campaign is built on a foundation of diligent intelligence gathering, meticulous analysis, and decisive action.

Step 1: Proactive Patent Monitoring and Target Selection

You cannot attack what you cannot see. The cornerstone of any offensive strategy is a robust and continuous patent intelligence operation. This means going far beyond passively waiting for a cease-and-desist letter. It requires actively monitoring the patent landscape to identify threats and opportunities as they emerge.

This is where comprehensive databases and intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable. These tools allow you to track competitor patent filings in real-time, monitor the prosecution history of pending applications, and, most importantly, receive alerts on patent grant dates and upcoming expirations.58 The goal is to build a strategic map of the competitive terrain, identifying which patents protect which products and when they are set to expire.

With this map, you can begin to prioritize targets. Not all patents are created equal. As research has shown, patent challenges are not random; they are highly correlated with market value. Drugs with annual sales in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars are far more likely to be challenged because the potential return on a successful invalidation is massive. Your first strategic filter should be commercial potential. Where can a successful challenge deliver the most significant market opportunity?

Step 2: The Nullity Search – Digging for Gold

Once a target patent is identified, the real work begins. The heart of any invalidity claim is the nullity search (also known as an invalidity search), a deep and exhaustive hunt for prior art that can be used to prove the patent was granted in error.60 The primary objective is to find what the patent examiner missed.

A world-class nullity search is a multi-pronged investigation that goes far beyond simple keyword searches in patent databases like the USPTO’s Patent Public Search or WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE. It must include:

- Deep Patent Database Searching: Using advanced search strategies, classification codes (like CPC or IPC), and citation analysis to uncover related patents.9

- Non-Patent Literature (NPL) Exploration: Scouring scientific journals, academic theses, conference proceedings, technical manuals, and even old product catalogs.1 The answer may lie in an obscure university dissertation from a decade ago.

- Leveraging AI-Powered Tools: The modern nullity search is increasingly supercharged by artificial intelligence. AI tools can analyze vast datasets in multiple languages, identify semantic relationships, and uncover non-obvious connections between disparate pieces of prior art that a human researcher might miss.60 They can transform the search from a linear process into a dynamic exploration of the entire knowledge landscape.

- Crowdsourcing: In some high-profile cases, organizations have successfully “crowdsourced” prior art searches, inviting communities of experts to help find invalidating references.

Step 3: Building the Case and Choosing the Battlefield

With prior art in hand, the next step is to construct the legal argument. This involves meticulously mapping the elements of the patent’s claims to the disclosures found in the prior art references, often visualized in detailed “claim charts”.61 This chart becomes the blueprint for your invalidity contention, clearly demonstrating how the prior art anticipates or renders the invention obvious.

Finally, you must make the critical strategic decision of where and when to launch your attack. As we’ve discussed, this is a complex choice with significant consequences:

- In Europe: Do you file an EPO opposition within the nine-month window? This is a low-cost, high-impact first strike that can also serve as a defensive shield against a future UPC preliminary injunction. If the window has closed, do you launch a central revocation action at the UPC or pursue national litigation?

- In the United States: The standard strategy is a parallel attack. You file a Paragraph IV certification to trigger the Hatch-Waxman litigation process, and you simultaneously prepare and file an IPR petition at the PTAB. You must carefully manage the timing to mitigate the Fintiv risk and decide which arguments to deploy in which forum to avoid estoppel issues.

An offensive strategy is a campaign, not a single battle. It requires foresight, diligence, and a willingness to invest in the intelligence and analysis needed to strike with precision and force.

Defensive Fortifications: A Patent Holder’s Guide to Withstanding the Siege

For an innovator company, patent defense is not a reactive exercise that begins when a lawsuit is filed. It is a continuous, lifecycle approach to intellectual property management. In an era of aggressive IPRs and heightened enablement standards, building a patent portfolio that can withstand a determined siege requires a proactive and strategic mindset from the very beginning.

Step 1: Robust Patent Prosecution – Building the Fortress Walls

The strongest defense is a well-built fortress. This starts during patent prosecution, long before any challenge materializes.

- Drafting a Bulletproof Specification: Your patent application is your first and best line of defense. In the wake of Amgen v. Sanofi, a detailed and comprehensive specification is more critical than ever. To defend against enablement and written description challenges, the application must include a wealth of data and examples.8 For biologic drugs, this means providing as many specific working examples (“species”) as possible to support any broader “genus” claims. A thin disclosure with only a few examples and broad functional claims is an open invitation to an invalidity challenge.

- Layered Claiming Strategy: A well-drafted patent includes a variety of claims, ranging from broad to narrow. While the broad claims provide the widest scope of protection, the narrower, more specific claims act as fallback positions. If the broad claims are invalidated, these narrower claims may survive, preserving a portion of your market exclusivity.

- Filing Continuation Applications: This is a crucial and often underutilized defensive strategy. By filing a “continuation” application before the parent patent issues, you keep the prosecution process open with the patent office. This gives you the flexibility to pursue new claims in the future, tailored to counter a competitor’s product or respond to developments in the law. It’s a strategic reserve that can be deployed years later to strengthen your defensive position.

Step 2: Arming Yourself with Evidence – The Power of Secondary Considerations

As discussed, an obviousness challenge is the most common form of attack. Your most potent shield is evidence of secondary considerations. However, this evidence cannot be gathered at the last minute. A strong defense requires a long-term, systematic approach to documenting objective indicia of non-obviousness.

- Documenting the “Nexus”: From the moment you launch a product, you should be building the case for nexus. Track sales data and market share, and be prepared to link that commercial success directly to the novel features of your patented invention.15 This may involve market research, customer surveys, and expert analysis to rule out other factors like marketing spend.

- Gathering Real-World Proof: Collect evidence of industry praise, awards, and positive reviews. Document any instances of competitors attempting to copy your invention. Keep records of the “long-felt need” your invention solved and any documented failures of others who tried to solve the same problem. This evidence, gathered over years, can be far more persuasive to a judge or jury than a purely technical argument about the prior art.

Step 3: Strategic Maneuvering in Litigation

When a challenge does arrive, you still have defensive maneuvers available.

- Strategic Claim Amendments: In many proceedings, including EPO oppositions and U.S. reexaminations, you have the option to amend your claims.18 By strategically narrowing the scope of your claims, you can sometimes carve out the prior art cited by the challenger, preserving a narrower but still valuable patent.

- Vigorous Parallel Defense: If a challenger attacks you on multiple fronts (e.g., district court and IPR), you must defend vigorously in both. A win in one forum can create persuasive precedent in the other. For example, successfully defending your patent in an EPO opposition can be used as powerful evidence of validity in a UPC preliminary injunction hearing.

Defending a patent is not about hunkering down and waiting for the storm to pass. It’s about having built a strong fortress from the outset, armed it with a stockpile of evidence, and having a flexible strategy to adapt and counter-attack when the siege begins.

To crystallize these concepts, the following checklist provides a practical tool for both challengers and patent holders to guide their strategic planning.

Table 3: Strategic Checklist for Invalidity Challenges

| For the Challenger (Offensive Plays) | For the Patent Holder (Defensive Plays) |

| [ ] Monitor Competitor Patents: Use tools like DrugPatentWatch to track grants and key dates. | [ ] Draft Robustly: Create a detailed specification with numerous examples and data. |

| [ ] Prioritize High-Value Targets: Assess market size to focus resources effectively. | [ ] File Continuations: Keep prosecution open to allow for future claim adjustments. |

| [ ] Conduct Exhaustive Nullity Search: Go beyond patents to NPL, using AI-powered tools. | [ ] Gather Secondary Consideration Evidence: Systematically collect data on commercial success, industry praise, etc. |

| [ ] Prepare Detailed Claim Charts: Meticulously map prior art to every claim element. | [ ] Document the “Nexus”: Proactively build the case linking success to the patented invention. |

| [ ] In Europe: File EPO Opposition? Act within the 9-month window for a cost-effective first strike. | [ ] In Litigation: Consider Claim Amendments: Be prepared to narrow claims to preserve validity. |

| [ ] In the U.S.: File Parallel IPR? Leverage the PTAB’s high invalidation rate, but manage Fintiv risk and estoppel. | [ ] In Litigation: Defend All Fronts: A win in an EPO opposition or IPR can bolster your case elsewhere. |

This playbook is not a guarantee of victory, but it provides a framework for thinking strategically about patent invalidity. By adopting these offensive and defensive postures, you can move from being a pawn in the game to being a master of the board.

Lessons from the Trenches: High-Profile Case Studies

Legal principles and strategic frameworks are essential, but their true meaning is forged in the crucible of high-stakes litigation. The outcomes of major court battles send shockwaves through the industry, reshaping legal doctrine and forcing companies to adapt their strategies. By dissecting these landmark cases, we can glean invaluable lessons about the real-world application of invalidity principles and the factors that drive victory and defeat. Let’s step into the trenches and examine three disputes that have redefined the pharmaceutical patent landscape.

Enablement Under the Microscope: Amgen v. Sanofi

Few patent cases in recent memory have had as immediate and profound an impact as the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi. This case did not create new law, but it powerfully reaffirmed and clarified the enablement requirement, sending a clear message to the biotechnology industry: if you claim a vast territory, you must provide a map to all of it, not just a few points of interest.

Case Summary

The dispute centered on Amgen’s revolutionary cholesterol-lowering drug, Repatha. The drug is a monoclonal antibody that works by inhibiting a protein called PCSK9.19 Amgen’s patents were a masterclass in strategic claiming. They didn’t just claim the specific 26 antibody sequences they had developed; they claimed the entire functional

genus of antibodies that could do two things: 1) bind to a specific region of the PCSK9 protein, and 2) block PCSK9 from interacting with LDL receptors.20 This broad claim scope was designed to give Amgen a monopoly over any antibody that worked through this mechanism, potentially covering millions of yet-undiscovered antibody structures.

Sanofi, which had developed its own competing PCSK9 inhibitor, Praluent, was sued for infringement. Sanofi’s defense was a direct assault on the validity of Amgen’s patents, arguing that they were not enabled. Sanofi contended that while Amgen had taught the world how to make its 26 specific antibodies, it had not taught anyone how to make and use the full, vast scope of the claimed genus. Discovering other functional antibodies, Sanofi argued, still required a long, unpredictable process of trial-and-error experimentation.20 Amgen’s patent, they claimed, offered only a “research assignment” or a “hunting license” to find more working antibodies, which falls short of the enablement requirement.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling and Rationale

The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which issued a unanimous 9-0 decision in favor of Sanofi.19 The Court’s reasoning was clear and direct, reaffirming a long-standing principle of patent law:

“the more one claims, the more one must enable”.20

The Court found that Amgen’s patents had failed to satisfy their end of the patent bargain. By claiming every antibody that could perform a certain function, Amgen was trying to monopolize a vast and largely unexplored territory. Yet, its disclosure only provided a few specific examples and a general “roadmap” for further discovery. This, the Court concluded, was not enough. To enable a genus claim, the patent must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the full scope of that genus without “undue experimentation”.23 Amgen’s approach, which required scientists to generate and test countless antibody candidates to see which ones worked, was the very definition of undue experimentation.

Strategic Impact

The Amgen decision was an earthquake for the biotech and pharmaceutical industries.

- For Challengers: It has elevated enablement from a standard invalidity argument to a primary weapon against patents for biologics, particularly those with broad functional claims. Any biosimilar company looking to challenge a patent on a class of antibodies now has a clear and powerful precedent to follow. The first question they will ask is: does the patent teach how to make everything it claims?

- For Innovators: The decision necessitates a fundamental shift in patenting strategy. The old model of filing early with broad, functional genus claims is now highly vulnerable. The new playbook requires:

- More Data, More Examples: Patent applications must be supported by a much more robust set of working examples (“species”) to justify the scope of the claims.

- Narrower, Layered Claims: Relying on a single, broad genus claim is risky. Portfolios must be built with layers of narrower species and sub-genus claims that can survive even if the broadest claim falls.

- Reconsidering Filing Timing: Companies now face a difficult strategic choice between filing early to secure a priority date and waiting until later in development when they have more data to fully enable a broader set of claims.

Amgen v. Sanofi serves as a powerful lesson: ambition in claim drafting must be matched by ambition in disclosure. The patent bargain is not to be taken lightly, and the courts will not hesitate to invalidate patents that claim more than they teach.

When Conduct Becomes a Weapon: Gilead v. Merck

If Amgen was a lesson in technical patent law, the epic battle between Gilead Sciences and Merck & Co. over Hepatitis C treatments was a masterclass in legal ethics and the devastating consequences of misconduct. This case is a cautionary tale that proves that even a patent that a jury finds valid and infringed can be rendered worthless if the patent holder’s hands are not clean.

Case Summary

The dispute involved patents held by Merck related to methods for treating the Hepatitis C virus (HCV). Gilead developed its own revolutionary HCV drugs, Sovaldi and Harvoni, which became multi-billion dollar blockbusters. Merck sued Gilead for infringement, and in March 2016, a jury sided with Merck, finding its patents were not invalid and awarding a staggering $200 million in damages.67

For Merck, it was a massive victory. But it was short-lived. Following the jury verdict, the judge held a separate bench trial on Gilead’s equitable defenses. Gilead argued that even if the patents were valid, Merck should be barred from enforcing them because of its own egregious misconduct. The judge agreed, and in a stunning reversal, vacated the entire $200 million verdict based on the doctrine of “unclean hands”.69

The “Unclean Hands” Finding

The “unclean hands” doctrine is an equitable principle that essentially states that a party seeking justice from a court must come to the court without having engaged in serious misconduct related to the matter at hand. It is broader than the more common defense of “inequitable conduct,” which is limited to misconduct before the USPTO.

The judge found a “pervasive pattern of misconduct” by Merck that was so severe it “infected the entire lawsuit”.68 The core of the misconduct stemmed from a 2003 confidential due diligence call between Merck and Pharmasset (a company Gilead later acquired). The call was governed by a strict “firewall” agreement, ensuring that any Merck personnel involved in its own HCV patent prosecution were excluded from the call.69

The court found that Merck had blatantly violated this agreement. A key Merck in-house patent attorney, who was actively prosecuting Merck’s own HCV patent applications, participated in the firewalled call and learned confidential information about Pharmasset’s lead compound (which would become sofosbuvir).73 He then used this improperly obtained information to amend Merck’s pending patent claims to better cover the compound.

To make matters worse, this same attorney then gave “inconsistent, contradictory, and untruthful” testimony about these events, first in a deposition and then at trial, in an attempt to cover up the misconduct.69 The court found this combination of unethical business conduct (breaching the firewall) and litigation misconduct (lying under oath) to be so reprehensible that it tainted Merck’s entire case.

Legal and Strategic Implications

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision, and the Supreme Court declined to hear the case, cementing the outcome.70 The

Gilead v. Merck saga provides several critical takeaways:

- Revival of a Potent Defense: The case breathed new life into the “unclean hands” doctrine as a powerful defense in patent litigation. It demonstrated that misconduct outside of the patent office—including unethical business dealings and lying in court—can have the same patent-killing effect as traditional inequitable conduct.

- Conduct Matters: It serves as a stark warning to all companies and their legal teams. The pursuit of a competitive edge cannot cross ethical and legal lines. A pattern of deceit can unravel even a successful jury verdict, turning a $200 million win into a total loss plus an order to pay the other side’s attorney’s fees.

- Internal Firewalls are Not Just Paperwork: For companies engaging in due diligence or collaborations, this case underscores the absolute necessity of respecting confidentiality and firewall agreements. A breach is not just a contractual issue; it can poison future patent enforcement efforts.

This case is a dramatic reminder that patent litigation is not just a technical dispute; it is also a test of character. The courts will not reward parties who seek to win through deceit.

Cross-Jurisdictional Chaos: The Battle Over Xarelto

Our final case study illustrates a crucial reality of the global pharmaceutical market: a patent’s strength is not universal. A patent that is a fortress in one country can be a house of cards in another. The sprawling, multi-front war over Bayer’s blockbuster anticoagulant, Xarelto (rivaroxaban), is a perfect example of this jurisdictional fragmentation.

Case Summary

Bayer’s Xarelto is a multi-billion dollar drug protected by a portfolio of patents. One of the key patents, EP 1 845 961, covered the use of rivaroxaban to manufacture a medication for treating thromboembolic disorders. As this patent neared the end of its life, generic manufacturers across Europe geared up to launch their own versions, leading to a cascade of litigation in numerous countries.

Divergent Outcomes

The results were a study in contradiction. The same patent, facing similar challenges from companies like Sandoz, Stada, and Teva, received wildly different judgments depending on the court hearing the case :

- Victories for Bayer: In the Netherlands, the District Court of The Hague dismissed nullity suits from Sandoz and Teva. Courts in Austria, Sweden, Lithuania, Belgium, and several other jurisdictions also upheld the patent’s validity, granting injunctions against generic entry.

- Defeats for Bayer: In stark contrast, the German Federal Patent Court revoked the patent for lack of inventive step, a decision that likely led to the lifting of preliminary injunctions in Europe’s largest market. The patent was also found invalid in the UK, France, Norway, Switzerland, Australia, and South Africa.

Even within the EPO, the patent’s fate was tumultuous. The Opposition Division initially revoked the patent, but the Boards of Appeal later overturned that decision and reinstated it, only for it to be invalidated again in multiple national proceedings.

Strategic Takeaway

The Xarelto saga underscores a critical lesson for any company with a global product: you cannot rely on a single patent or a single legal theory to protect a global blockbuster. National courts, with their own precedents, procedures, and judicial philosophies, can and do arrive at completely different conclusions on the same set of facts.

This jurisdictional chaos is precisely what the Unified Patent Court was designed to mitigate. The goal of the UPC is to provide a single, consistent ruling on validity and infringement across most of the EU. However, until the UPC’s jurisprudence is fully developed and its reach is complete, and for disputes in non-UPC countries like the UK and Switzerland, this fragmentation remains a central strategic reality. A global patent litigation strategy must be tailored, flexible, and jurisdiction-specific, recognizing that a victory in one capital is no guarantee of victory in another.

The Future of the Fight: AI, Biologics, and the Evolving Landscape

The battlefield of patent invalidity is not static. It is constantly evolving, shaped by technological advancements, new legal precedents, and shifting regulatory frameworks. As we look to the horizon, two forces in particular are set to redefine the rules of engagement: the rise of artificial intelligence in drug discovery and the enduring complexity of patenting biologics and personalized medicines. For any company hoping to compete in the coming decade, understanding these future-facing challenges is not just a matter of intellectual curiosity; it is a matter of survival.

The AI Disruption: A Double-Edged Sword for Patent Validity

Artificial intelligence is no longer science fiction; it is a rapidly integrating tool in the pharmaceutical R&D pipeline. AI platforms can now sift through vast biological and chemical datasets, predict molecular interactions, identify novel drug targets, and even design new drug candidates, all at a speed and scale that dwarfs human capability.59 This AI revolution promises to slash drug development timelines and costs, but it also introduces a host of new and complex challenges for the patent system.78 For patent validity, AI is a true double-edged sword, simultaneously creating new ways to fortify patents and new ways to tear them down.

AI as an Offensive Weapon for Challengers

For those on the offense, AI is a powerful new form of artillery.

- Supercharged Prior Art Searches: The nullity search, the cornerstone of an invalidity attack, is being transformed by AI. AI-powered search tools can scour global databases, including non-patent literature in multiple languages, and identify semantic connections and obscure references that would have been virtually impossible for human researchers to find.60 This dramatically increases the likelihood of a challenger finding a novelty-destroying or obviousness-creating piece of prior art.

- Raising the Bar for Non-Obviousness: The legal standard for obviousness is judged from the perspective of a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (POSITA). As AI tools become standard equipment for scientists in the field, the capabilities of this hypothetical POSITA are effectively being augmented by machine intelligence. What might have been an inventive leap for a human scientist five years ago may now be considered an “obvious” permutation that an AI could generate in minutes. This rising tide of AI capability will make it progressively harder for innovators to prove their inventions are truly non-obvious.81

- The Flood of AI-Generated Prior Art: A more radical challenge comes from AI systems designed explicitly to create prior art. Services like “All Prior Art” use AI to generate millions of technical disclosures with the sole purpose of preemptively blocking future patents.64 This raises complex legal questions: Is a computer-generated disclosure that no human has reviewed or validated truly “publicly accessible” and “enabling” enough to qualify as prior art? The legal system is still grappling with this, but the sheer volume of this AI-generated content could create a “prior art minefield” for future innovators.

AI as a Defensive Vulnerability for Innovators

For patent holders, the integration of AI into their own R&D processes creates novel vulnerabilities.

- The Inventorship Dilemma: This is the most immediate and critical risk. U.S. patent law is unequivocal: an inventor must be a human being. An AI system cannot be named as an inventor.59 This principle, affirmed in the

Thaler v. Vidal case, means that for an AI-assisted discovery to be patentable, a human must have made a “significant contribution” to the conception of the invention.77 Merely owning the AI, funding the research, or recognizing the value of the AI’s output is not enough. This creates a new line of attack for challengers: if they can prove that an invention was conceived primarily by an AI, with insufficient human ingenuity guiding the process, the resulting patent could be invalidated for improper inventorship. - The Documentation Burden: This inventorship requirement places a massive new documentation burden on innovators. To defend against such a challenge, companies must now keep meticulous records that prove significant human contribution at every stage of the discovery process.81 This includes documenting the specific prompts given to the AI, the rationale for selecting certain AI outputs for further study, and the human-led experimental work that validated or modified the AI’s suggestions. The era of the detailed lab notebook, once thought to be less critical after the U.S. moved to a “first-to-file” system, is back with a vengeance.

- The “Black Box” Enablement Problem: The opaque nature of some AI models—the so-called “black box” problem—can create disclosure challenges. If an inventor cannot fully explain how their AI model arrived at a particular solution, it may be difficult to write a patent specification that is sufficiently enabling to teach a skilled person how to replicate the process.59

Paradoxically, AI can also be a defensive tool. Innovators are now using AI to generate hundreds or even thousands of examples (“species”) of a claimed invention to include in a patent application, specifically to bolster their disclosure and satisfy the heightened enablement requirements of the post-Amgen world.

The strategic implication is clear: AI is not just another research tool; it is a new player on the patent battlefield. Companies must embrace AI to remain competitive in R&D, but they must simultaneously develop new legal, ethical, and documentation strategies to manage the profound patent risks it creates. Failure to do so will leave their most valuable future assets dangerously exposed.

The Unique Challenges of Biologics and Personalized Medicine

Even without the added complexity of AI, the nature of modern biological science presents inherent challenges to the traditional patent system. The principles of patent law, largely developed for mechanical devices and predictable chemistry, are often an awkward fit for the complex and unpredictable world of biology.

The Enduring Complexity of Biologics

As we saw in the Amgen case, biologic drugs are fundamentally different from traditional small-molecule drugs. They are large, complex molecules—proteins, antibodies, nucleic acids—produced in living systems, not through straightforward chemical synthesis. This complexity creates persistent patenting challenges:

- Describing the Indescribable: Fully characterizing a complex biologic in a patent application can be a monumental task. This difficulty in description makes biologic patents inherently susceptible to written description and enablement challenges.

- The Post-Amgen Landscape: The Amgen decision has amplified this vulnerability. For the many biologics that are defined by their function (e.g., “an antibody that binds to target Y”), the requirement to enable the full scope of that function has become a formidable barrier, demanding a level of disclosure that may be impractical early in the development process.

The Controversy of Personalized Medicine and Gene Patents

The field of personalized medicine, which aims to tailor treatments based on a patient’s genetic makeup, pushes the boundaries of patentable subject matter. Patents in this space often seek to claim not a new drug, but a relationship—a correlation between a specific genetic variant (genotype) and a clinical outcome (phenotype).

This has sparked intense controversy and legal challenges. Critics argue that such patents are attempts to claim “products of nature” or “laws of nature,” which are explicitly excluded from patentability. A gene sequence itself is a product of nature, and the relationship between that gene and a disease is a natural phenomenon. While patents on new biologics derived from genetic information have been seen as stimulating innovation, patents on the diagnostic correlations themselves have been criticized for stifling research, increasing the cost of genetic testing, and reducing patient access to vital medical information.

Landmark cases like Mayo v. Prometheus and Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics have led the Supreme Court to take a restrictive view, making it very difficult to patent diagnostic methods that do not add a sufficiently “inventive concept” beyond the natural correlation itself. This legal uncertainty creates significant strategic challenges for companies investing heavily in the development of companion diagnostics and other personalized medicine technologies. They must navigate a fine line, seeking to protect their genuine innovations without overstepping the murky boundaries of patentable subject matter.

The future of patent invalidity will be fought on these new frontiers. Success will belong to those who not only master the traditional rules of the game but also anticipate and adapt to the disruptive forces of technology and the evolving definition of what is, and is not, a patentable invention.

Conclusion: Mastering the Art of Patent Validity in the Modern Pharmaceutical Era

We have journeyed through the intricate and high-stakes world of drug patent invalidity, from the foundational legal principles that govern a patent’s life to the complex procedural battlefields of the United States and Europe. We have dissected the strategic playbooks of both challengers and defenders and explored the emerging forces of AI and biotechnology that are reshaping the competitive landscape.

The central, undeniable conclusion is this: handling patent invalidity claims is no longer a reactive, siloed legal function. It is a dynamic, proactive, and deeply strategic discipline that must be woven into the very fabric of a pharmaceutical company’s business strategy. The immense financial stakes—where market exclusivity for a single blockbuster drug can be worth tens of billions of dollars—demand nothing less.

For challengers, particularly generic and biosimilar manufacturers, the modern legal landscape offers an arsenal of powerful offensive weapons. The challenger-friendly rules and high invalidation rates of the U.S. Inter Partes Review process, the heightened enablement standards for biologics following Amgen v. Sanofi, and the cost-effective, centralized nature of EPO oppositions and UPC revocation actions provide unprecedented opportunities to clear the path for competition and bring affordable medicines to patients. Success, however, requires diligent intelligence, meticulous preparation, and the strategic coordination of multi-front attacks across different forums and jurisdictions.

For innovators, the message is equally stark. The days of “file it and forget it” patenting are over. The defensive posture must be one of constant vigilance and proactive fortification. It begins with building a robust patent fortress from the ground up through sophisticated prosecution strategies—drafting detailed specifications, providing numerous examples, and using layered claims and continuation applications to maintain flexibility. It continues with the systematic, long-term gathering of real-world evidence to support non-obviousness. And when the inevitable challenge arrives, it requires a nimble and aggressive defense across all parallel proceedings.

As we look to the future, the pace of change will only accelerate. The rise of artificial intelligence is a paradigm-shifting force, simultaneously empowering innovators to create and defend their patents while arming challengers with more potent tools to find and exploit their weaknesses. The ongoing complexities of patenting biologics and personalized medicine will continue to test the very boundaries of patent law.