The Anatomy of a “Broken” Market: Unpacking U.S. Drug Pricing

The United States healthcare system is a global outlier, particularly in the realm of pharmaceuticals. It is a well-documented fact that Americans pay the highest prices for prescription drugs in the world, a reality that forms the essential backdrop to any discussion of market disruption.1 Studies consistently find that U.S. drug prices are substantially higher than those in other developed nations, with one 2021 analysis finding prices to be 2.5 times higher than in 32 other countries, and a 2022 report noting prices were nearly 2.78 times as high.1 This price disparity is not an incidental outcome but the result of a deliberately complex, multi-layered, and opaque system of distribution and reimbursement. Understanding the mechanics of this system is critical to appreciating the nature of the problem that entrepreneurs like Mark Cuban have set out to solve.

The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain: A Labyrinth of Intermediaries

The journey of a prescription drug from the laboratory to the patient is a convoluted path involving multiple powerful entities, each adding cost and complexity along the way. The structure of this supply chain is the primary reason that only a fraction of the final price paid for a medication reflects its direct production cost.3

Manufacturers: At the apex of the supply chain are the pharmaceutical manufacturers. These companies, ranging from global giants developing patented brand-name drugs to firms specializing in generics, perform the foundational work of research, development, and production.4 Critically, they establish the initial list price for a drug, known as the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). The WAC is not based on the cost of production but is instead a strategic calculation based on anticipated demand, market competition, and the perceived value of the therapy.4 This list price serves as the starting point for all subsequent negotiations, discounts, and rebates within the supply chain, giving manufacturers immense influence over the ultimate cost structure.4

Wholesalers: Once a drug is manufactured, it typically enters the distribution network through a wholesaler. A small number of large firms—notably Cardinal Health, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen—dominate this segment, acting as the logistical backbone of the industry.4 They purchase medications in bulk from hundreds of manufacturers and efficiently distribute them to tens of thousands of individual pharmacies and healthcare facilities.4 Their business model is predicated on achieving economies of scale, operating on thin margins from drug sales but on an enormous volume, supplemented by fees for their distribution and data management services.4

Pharmacies: As the final point of contact with the patient, pharmacies dispense medications and provide clinical services. This category includes large national chains, independent “mom-and-pop” drugstores, supermarket pharmacies, and mail-order services.4 Pharmacies purchase drugs from wholesalers and are reimbursed through a combination of the patient’s out-of-pocket payment (co-pay) and a payment from the patient’s insurance plan, which is adjudicated by a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM).4 A critical and growing challenge for pharmacies, particularly independents, is that PBM reimbursement rates are often set below the pharmacy’s actual cost to acquire the drug, forcing them to dispense certain medications at a loss and threatening their financial viability.6

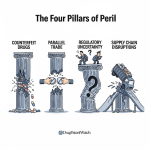

The Global Dimension: The U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain is not a closed domestic loop. It is deeply intertwined with and dependent on a global network of suppliers, a vulnerability that has become a significant public health and national security concern.9 The U.S. has offshored much of its manufacturing capacity and now relies heavily on foreign sources, particularly India and China, for both finished drugs and, more critically, the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) required to produce them.9 This dependence makes the nation’s drug supply susceptible to geopolitical tensions, trade disputes, and disruptions from global events, as starkly illustrated by the plant closures during the COVID-19 pandemic.11 This fragility leads to frequent drug shortages, which can have devastating consequences for patients who rely on these essential medicines.9

The Central Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

While each player in the supply chain contributes to the final cost, no entity is more central to the modern drug pricing debate than the Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM). Originally created in the 1960s to serve as simple claims administrators for insurance companies, PBMs have evolved into powerful and complex organizations that manage the prescription drug benefits for the vast majority of Americans.4 The industry is highly concentrated, with three colossal firms—CVS Caremark (owned by CVS Health), Express Scripts (owned by Cigna), and OptumRx (owned by UnitedHealth Group)—controlling an estimated 79% to 90% of the market, processing the prescriptions for over 289 million people.15

PBMs perform several core functions that place them at the nexus of the pharmaceutical ecosystem 14:

- Formulary Management: They create and maintain formularies, which are lists of prescription medications covered by a health plan. Their decisions on which drugs to include, and on which “tier” with varying levels of patient cost-sharing, effectively determine patient access to medications.

- Rebate Negotiation: They use their immense purchasing power, representing millions of patients, to negotiate rebates from drug manufacturers. In theory, these rebates are discounts paid by the manufacturer in exchange for having their drug placed in a favorable position on the PBM’s formulary.

- Pharmacy Network Contracting: They contract with pharmacies to create networks for health plans, setting the reimbursement rates that pharmacies will be paid for dispensing medications.

The business practices of PBMs have drawn intense scrutiny and are at the heart of the drug pricing controversy. The rebate system is particularly contentious. It is a system shrouded in secrecy, with the exact size of the rebates and the portion retained by the PBM rarely disclosed publicly.1 Critics, including drug manufacturers, argue that the demand for ever-larger rebates forces them to continuously raise their list prices.14 Furthermore, because PBM revenue is often tied to a percentage of the rebate, a perverse incentive is created: a PBM may be financially motivated to favor a drug with a higher list price that offers a larger rebate over a clinically equivalent drug with a lower list price and a smaller rebate.5

PBMs also generate significant revenue through a practice known as “spread pricing.” This occurs when a PBM charges a health plan a certain amount for a drug but reimburses the dispensing pharmacy a lower amount, keeping the difference—or “spread”—as profit.7 This practice is particularly common with low-cost generic drugs and allows PBMs to capture profits that are not transparent to their clients.

Compounding these issues is the trend of vertical integration. The largest PBMs are no longer standalone entities; they are owned by or merged with some of the nation’s largest health insurance companies and also own their own mail-order and specialty pharmacies.5 This creates clear conflicts of interest. These integrated giants can design benefits that steer patients toward their own affiliated pharmacies, often at the expense of independent competitors. Independent pharmacies argue that this self-dealing leads to their being under-reimbursed to the point of closure, creating “pharmacy deserts” in underserved communities while enriching the PBM’s parent corporation.7

The entire system is structured in a way that prioritizes opacity. The complexity of the supply chain, combined with the confidential nature of the contracts and rebate negotiations between PBMs, manufacturers, and payers, results in a market where the true net price of a drug is obscured. This lack of transparency is not an accidental flaw; it is a fundamental feature of the market that enables intermediaries to extract significant value. This information asymmetry prevents the ultimate payers—employers, government programs, and patients—from understanding the actual flow of money and verifying whether they are receiving the full benefit of negotiated discounts. The financial incentives of the most powerful players are thus misaligned with the goal of achieving the lowest possible net cost for the healthcare system. It is this fundamental misalignment and opacity that forms the central target of Mark Cuban’s critique and his disruptive business model.

| Player | Primary Role in Supply Chain | Key Revenue/Profit Drivers | Primary Criticisms / Systemic Issues |

| Manufacturer | Researches, develops, and produces drugs; Sets the initial Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) or “list price.” | Sales of drugs to wholesalers at the WAC; Profit margin on patented, brand-name drugs. | High initial list prices for brand-name drugs; “Patent thickets” to delay generic competition. |

| Wholesaler | Purchases drugs in bulk from manufacturers; Manages logistics and distributes to pharmacies and hospitals. | Small margin on high-volume drug sales; Fees for distribution, data, and financial services. | Industry consolidation limits competition; Can contribute to price inflation on generics. |

| Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) | Negotiates rebates with manufacturers; Creates drug formularies; Processes claims; Contracts with pharmacy networks. | Share of manufacturer rebates; “Spread pricing” on generic drugs; Administrative fees from clients (insurers/employers). | Opaque contracts and pricing; Perverse incentives favoring high-list-price drugs; Drives independent pharmacies out of business. |

| Pharmacy | Dispenses medications to patients; Provides clinical counseling and services. | Dispensing fees; Margin on drug sales (if any); Reimbursement from PBMs and patient co-pays. | Under-reimbursement by PBMs, often below acquisition cost; Negative margins on many brand-name drugs; Administrative burden. |

| Table 1: The U.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain: Key Players and Financial Flows |

The Cuban Doctrine: A Diagnosis and a Prescription for Disruption

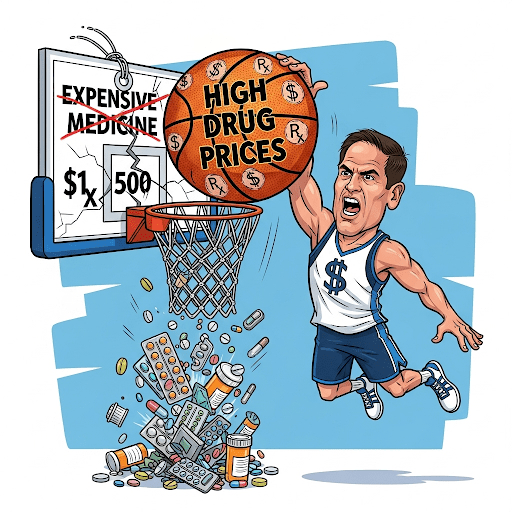

In the face of the labyrinthine and widely criticized U.S. drug pricing system, billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban has emerged as one of its most vocal and visible antagonists. His commentary is not merely a collection of grievances but constitutes a coherent “doctrine” for reform—a specific diagnosis of the system’s ills coupled with a clear prescription for disruption. This doctrine, which underpins the strategy of his business ventures, targets the opaque and powerful middlemen he sees as the root of the problem and champions a return to transparent, market-based principles.

The Primary Target: Exposing and Eliminating the PBM “Problem”

At the core of the Cuban doctrine is an unwavering focus on Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) as the primary architects of the dysfunctional market. In his analysis, nearly all the system’s pathologies can be traced back to their business practices. He has stated this view unequivocally: “All of the issues lead back to how big PBMs do business”.16 Cuban frames PBMs not as value-adding negotiators but as parasitic intermediaries whose complex and secretive operations serve only to distort prices and siphon billions of dollars from the healthcare system.5

He argues that their practices actively suppress the cost-saving potential of affordable medications like generics and biosimilars, which should be the foundation of a cost-effective system.16 His assessment is blunt, asserting that there is “no reason for the big ones that control 90% of the prescriptions that are filled… to exist”.17 This is not a call for incremental reform of PBMs but for their effective elimination and replacement.

Cuban’s Six-Point Plan for Reform

Cuban’s critique is not limited to broadsides; he has articulated a specific and detailed policy agenda for dismantling the PBM-controlled system. In a notable moment of crossover with the political sphere, he publicly endorsed a healthcare executive order from the Trump administration, using the opportunity to outline a six-point plan that he believes could save hundreds of billions of dollars. This plan serves as a concrete blueprint for his vision of a reformed market 22:

- Divorce Formularies from PBMs: He calls for formularies to be developed by independent groups that have no economic stake in the outcome. This would sever the link between formulary placement and rebates, ending the “rebate game” and allowing for true net pricing.

- Mandate Data Transparency: PBMs should be required to provide complete claims data to their clients (employers, states). This would eliminate the need for manufacturers to pay PBMs for this data, a cost saving that could then be passed on in the form of lower retail prices.

- Eliminate “Specialty” Tiers: He argues that the “specialty drug” designation is an artificial construct used primarily to “jack up the price” and lock patients into using the PBM’s own high-cost specialty pharmacies.

- Ensure Fair Pharmacy Reimbursement: He advocates for policies that would require PBMs to fully reimburse pharmacies for the cost of brand-name drugs and to eliminate the “generic cost ratio,” a mechanism he claims allows distributors to inflate prices on generics.

- Remove Confidentiality Clauses: He calls for an end to the “gag clauses” in PBM contracts that prevent payers and pharmacies from speaking directly with drug manufacturers. He believes direct communication would foster competition and lead to better pricing.

- End Biosimilar Substitution Games: He proposes stopping PBMs from using their formulary power to block the use of the lowest-cost biosimilar drugs, ensuring patients and payers benefit from this emerging competition.

The Philosophy: Radical Transparency and Market-Based Disruption

Underpinning Cuban’s specific policy proposals is a core philosophy of radical transparency as the ultimate market disinfectant. His stated mission is “to introduce transparency to the pricing of drugs so that patients know they are getting a fair price”.23 He believes that the current system thrives on complexity and opacity, and that simply shining a light on the true costs and hidden markups will cause the entire edifice to crumble.

This belief informs his preference for market-based solutions over government intervention. He has argued that the path to reform is “less legislation and more companies understanding how all of this works and how it works against them”.16 His strategy is to empower the market’s customers—namely, self-insured companies and states—with the knowledge and tools to bypass the incumbent PBMs and contract instead with smaller, transparent “pass-through” PBMs that provide full data access and control.16

This philosophy extends to a broader, almost moralistic, view of the healthcare system. He frames the issue as a “David-and-Goliath fight” between “good actors” and “bad actors.” In his telling, physicians are the “good guys,” dedicated to patient care, while insurers, PBMs, and private equity firms are the “bad guys” who profit by deliberately complicating the system and extracting arbitrage from its inefficiencies.24

This approach represents a unique blend of populist anger and libertarian, free-market principles. The rhetoric—vowing to “dunk on the pharma industry” and “f— up the drug industry in every way possible”—is populist, casting the conflict as a battle between the public and a corrupt corporate oligarchy.25 Yet, the proposed solutions are not rooted in government price controls or a single-payer system. Instead, they are fundamentally about empowering market participants. By demanding data transparency, ending gag clauses, and encouraging employers to switch providers, his goal is to create a more perfect market where informed consumers can make rational choices. This is a classic free-market belief that a system corrected by transparency and competition will regulate itself more efficiently than any government body could. This positions his reform efforts as distinct from policy-driven initiatives like the Inflation Reduction Act, which relies on direct government negotiation power.12 Cuban’s is a strategy to disrupt the market from within.

However, this diagnosis, while powerful, has its limitations. Cuban’s intense focus is on the value extracted by intermediaries after the manufacturer sets the WAC. His model is designed to surgically remove these intermediary costs. While PBMs and their rebate demands certainly contribute to high list prices, this view arguably understates the immense pricing power held by manufacturers of novel, patent-protected brand-name drugs.3 For a unique, life-saving therapy with no competition, a manufacturer can command an exceptionally high price regardless of the PBM system. Therefore, while Cuban’s doctrine and the business model it spawned are exceptionally effective at tackling the inflated prices of generic drugs, their ability to solve the brand-name drug problem—the primary driver of overall spending—is a far greater and more complex challenge.

The Cost Plus Model: A Radical Approach to Transparency

To translate his doctrine of disruption into action, Mark Cuban, along with founder and CEO Dr. Alexander Oshmyansky, launched the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC). This venture is not merely another discount pharmacy; it is the operational embodiment of Cuban’s critique, designed from the ground up to be a transparent, vertically integrated alternative to the incumbent pharmaceutical supply chain. Its business model is a direct assault on the opacity and misaligned incentives that define the traditional system.

The “Cost + 15%” Formula: The Core of the Model

The foundational principle of MCCPDC is its radically simple and transparent pricing formula. Every drug it sells is priced according to a clear, publicly stated calculation: the actual manufacturer acquisition cost, plus a flat 15% markup, a $5 pharmacy labor fee, and a $5 shipping fee.1 On the company’s website, the product page for each medication explicitly breaks down this math, showing the customer exactly how the final price is derived.23 For example, the company explains that for the drug Albendazole, its cost is $26.08. A 15% markup ($3.85) is added to run the company, plus a $5 pharmacy fee, resulting in a final price of less than $35 before shipping—a stark contrast to the potential $500 price tag in the traditional market.23

This approach stands in diametric opposition to the convoluted and secret pricing of the legacy system. The 15% markup is designed to be sufficient to cover all operational expenses and fund the company’s continued growth and investment in disrupting the industry.1 Cuban has been clear that while the mission is paramount, the business is designed to be profitable and sustainable, not purely altruistic.29

Vertical Integration: Controlling the Supply Chain

A key strategic element of the MCCPDC model is its aggressive pursuit of vertical integration. The company’s goal is to control as much of the pharmaceutical value chain as possible, thereby collapsing the multi-stage, opaque supply chain into a single, streamlined, and transparent entity.26 This integration manifests across several business lines:

- Wholesale Operations: MCCPDC is a licensed drug wholesaler, which allows it to bypass traditional wholesale distributors and negotiate directly with drug manufacturers. This direct relationship is crucial for securing the lowest possible acquisition cost, which is the foundation of its pricing model.26

- Direct-to-Consumer Pharmacy: The most visible part of the company is its online pharmacy, which ships medications directly to patients across the country. This direct-to-consumer (DTC) model eliminates the need for physical retail storefronts and their associated overhead.26 The complex tasks of prescription fulfillment and pharmacist consultation are managed through partnerships with accredited digital pharmacy providers like Truepill and HealthDyne.31

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: In its most ambitious and strategically significant move, MCCPDC has become a drug manufacturer itself. In early 2024, the company opened a 22,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art sterile fill-finish facility in Dallas, Texas.1 The explicit purpose of this facility is to produce its own high-quality generic medications, with a focus on products that are in critical shortage or have been subject to exorbitant price hikes.23 This manufacturing capability provides the ultimate level of cost control and insulates the company from supply chain disruptions. This initiative has garnered national attention, with the facility being included in a federal partnership with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to advance domestic drug manufacturing using cutting-edge technologies like AI and machine learning.34

The “UnPBM” and B2B Strategy: Expanding the Disruption

Recognizing the limitations of a purely DTC cash-pay model, MCCPDC is actively targeting the much larger business-to-business (B2B) market of employers and health plans. It does this through what it calls an “UnPBM” or reimagined pharmacy benefit.26 This service allows self-insured employers, Managed Care Organizations (MCOs), and other payers to access MCCPDC’s transparent, pass-through pricing for their members.

Clients have the flexibility to either add Cost Plus Drugs as an in-network pharmacy option within their existing benefit structure or to use MCCPDC and its partners to create a “bolt-on” prescription drug program that overlays their current plan.26 The company boasts that this model can generate savings of 50% to 90% on a client’s existing spending on generic drugs.26 This B2B strategy is critical for scaling the company’s impact beyond individual consumers to entire populations of employees and health plan members.

A Public-Benefit Corporation (PBC): Mission-Driven Capitalism

Further reinforcing its disruptive brand, MCCPDC is legally structured as a Public-Benefit Corporation (PBC). This corporate structure legally obligates the company to balance the financial interests of its shareholders with a stated social mission—in this case, improving public health.26 This is not merely a marketing posture; it is a legal commitment that differentiates MCCPDC from purely profit-driven competitors. This mission-driven identity resonates with a growing segment of consumers and partners who prioritize corporate responsibility and may be a key factor in building trust and loyalty.35 For Cuban, this has personal significance; he has stated that MCCPDC is the only company he has ever put his name on, because he wants it to be a legacy his children can be proud of.29

The strategic choices made by MCCPDC reveal an ambition that goes far beyond simply offering lower prices. The company is attempting to fundamentally rebuild the pharmaceutical value network. The traditional, fragmented chain—Manufacturer to Wholesaler to PBM to Pharmacy to Patient—is characterized by multiple handoffs, each providing an opportunity for opaque markups and fees. MCCPDC’s vertically integrated model, as depicted in its own “Before and After” diagrams, collapses this chain into a single entity responsible for the entire process, from manufacturing to patient delivery.26 This structural change is what makes its promise of transparency credible; the price is based on a known internal cost structure, not a black box of negotiated deals with external parties.

Furthermore, the decision to enter manufacturing is a critical long-term play. It directly addresses the systemic problem of drug shortages, a major vulnerability in the U.S. healthcare system stemming from over-reliance on fragile global supply chains.9 By building a domestic facility designed to produce drugs on the FDA’s shortage list, MCCPDC positions itself not only as a cost-cutter but also as a provider of supply chain resilience and reliability.17 This dual value proposition—cost and reliability—has made it an attractive partner for patient advocacy groups like Angels for Change, which is collaborating with MCCPDC to proactively manufacture at-risk oncology drugs, as well as for large health systems and even the federal government.13 This strategic move is a hedge against the very supply chain vulnerabilities that plague the incumbent system, providing a durable competitive advantage that transcends price alone.

Quantifying the Disruption: An Evidence-Based Impact Assessment

The claims of disruption made by the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company are not merely rhetorical. A growing body of evidence, from direct price comparisons to peer-reviewed academic research, allows for a quantitative assessment of the model’s financial impact. This data demonstrates that while the scale of savings varies by drug and patient profile, the potential for significant cost reduction at both the individual and systemic levels is undeniable.

Direct Price Comparisons: MCCPDC vs. The Market

The most immediate and dramatic evidence of MCCPDC’s impact can be seen in direct price comparisons for specific medications, which often reveal staggering disparities.

- Against Retail/List Prices: For certain high-cost generic drugs, the savings offered by MCCPDC are transformative. One of the most frequently cited examples is imatinib, a life-saving oral chemotherapy drug used to treat leukemia. The list price for a one-month supply can be as high as $2,500 or even over $9,600 at traditional pharmacies.1 At MCCPDC, the same medication costs as little as $13.40 to $17.10.1 Another example is dimethyl fumarate, a generic medication for multiple sclerosis, which MCCPDC offers for $54.75 compared to a traditional pharmacy channel price of $4,965.52.37 For the anti-parasitic drug albendazole, the price plummets from as much as $500 per course to just $35 through MCCPDC.23

- Against Discount Cards (GoodRx): Even when compared to other discount platforms like GoodRx, which also aim to lower cash prices for patients, MCCPDC often emerges as the more affordable option. A 2023 observational cost-analysis focused on dermatology medications found that the average cost for a selection of common drugs was $17 at MCCPDC versus $31.21 using GoodRx coupons.38 The study concluded that even after accounting for MCCPDC’s shipping fees, its prices remained significantly lower.38 This is corroborated by extensive anecdotal reports from consumers. On social media platforms, users frequently share experiences of being quoted a high price with a GoodRx coupon, only to find the drug for a fraction of that cost at MCCPDC. One user reported a 90-day supply of a medication was quoted at $80 with GoodRx but cost only $12 at Cuban’s pharmacy.39

- Against Insurance Co-pays: For a significant and growing number of Americans, particularly those enrolled in high-deductible health plans, MCCPDC’s transparent cash price is often lower than their insurance-negotiated co-payment.21 This has led to the counterintuitive phenomenon of insured patients choosing to bypass their own insurance benefits to purchase medications from MCCPDC, as it saves them money out-of-pocket.21

System-Level Savings: The Medicare Case Studies

While individual price comparisons are compelling, the most powerful evidence of MCCPDC’s disruptive potential comes from a series of academic studies that have estimated the potential savings for the Medicare program. These studies provide a third-party, data-driven validation of the model’s efficiency at a systemic level.

- Overall Generics: A landmark study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2022 analyzed 89 generic drugs offered by MCCPDC and compared their prices to what Medicare Part D paid in 2020. The researchers concluded that Medicare could have saved $3.6 billion in that one year alone on this small subset of drugs by purchasing them at MCCPDC’s prices.41 The study identified massive inefficiencies in the existing generic drug reimbursement system as the cause of the overpayment.3

- Oncology Drugs: The savings are particularly pronounced in oncology, where generic drug prices can be artificially inflated. A 2023 study presented to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) examined just nine cancer-directed drugs available through MCCPDC. It estimated that Medicare Parts B and D could achieve potential annual savings of $1.06 billion by using the MCCPDC 90-day pricing model. The percentage savings on individual drugs were immense: 96% on abiraterone, 98% on imatinib, and 70% on methotrexate.43

- Men’s Health Drugs: A study published in the Journal of Men’s Health analyzed 15 drugs in the men’s health category and found that if Medicare had adopted MCCPDC’s pricing for 90-count prescriptions, it could have saved a total of $1.3 billion.44

- Diabetes Drugs: Not every therapeutic area shows such uniform savings. A study on 13 diabetes medications found a more mixed picture. For 30-day supplies, Medicare’s prices were often lower. However, for 90-day supplies (excluding the widely used metformin), MCCPDC’s pricing was more favorable, with potential savings of $158 million.46 This highlights that the model’s cost-effectiveness can vary depending on the specific drug, quantity, and existing negotiated rates within Medicare.

Patient-Level Savings: Out-of-Pocket Costs

While systemic savings are substantial, the direct impact on patients’ wallets is also a key metric. An economic evaluation using the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) sought to quantify these out-of-pocket savings. The study found that potential savings for patients existed in approximately 11.8% of all generic prescription fills analyzed.47

For those prescriptions where savings were possible, the median saving per fill was a relatively modest $4.96. However, the benefit was not distributed evenly. The savings were highest for uninsured individuals, with a median of $6.08 per fill, demonstrating that the model provides the most significant relief to those with the least coverage.47 Conversely, the study found no potential cost savings for patients with Medicaid, which is logical given that Medicaid beneficiaries typically have very low or zero out-of-pocket costs for their medications.47

The evidence points toward a two-tiered impact. For a specific subset of generic drugs, particularly those in oncology and other specialty areas where legacy pricing has been egregiously inflated, the MCCPDC model is a revolutionary force, capable of generating savings exceeding 90% and altering the financial landscape for payers like Medicare. For the broader basket of common, low-cost generics, the impact is more incremental on a per-prescription basis. The median out-of-pocket saving of around $5 is not life-altering for every patient, but it represents a meaningful competitive pressure on the market and provides a crucial safety valve for the uninsured.

The academic studies quantifying potential Medicare savings are perhaps the most potent tool in MCCPDC’s arsenal. They elevate the company’s narrative beyond that of a simple discount pharmacy competing with the likes of GoodRx. By providing objective, peer-reviewed evidence of billions of dollars in potential savings for the U.S. government, these studies transform MCCPDC into a credible, data-backed policy solution. This third-party validation lends significant weight to Cuban’s claims of systemic inefficiency and provides a powerful, data-driven rationale for large payers and policymakers to engage with his model, viewing it not just as a consumer-facing app but as a viable strategy for systemic fiscal reform.

| Drug Name & Dosage | Condition Treated | Typical Retail Price | Typical GoodRx Price | MCCPDC Price (incl. fees) | % Savings (MCCPDC vs. Retail) |

| Imatinib 400mg (30 ct) | Leukemia (Cancer) | $2,500 – $9,657 1 | $120 27 | $13.40 – $17.10 1 | >99% |

| Dimethyl Fumarate 120mg (60 ct) | Multiple Sclerosis | $4,965 37 | N/A | $54.75 37 | ~99% |

| Albendazole 200mg (2 tablets) | Parasitic Infection | $500 23 | N/A | $35.00 23 | 93% |

| Atorvastatin 40mg (30 ct) | High Cholesterol | ~$60 | ~$15 | ~$3.90 | ~94% |

| Acyclovir 400mg (30 ct) | Viral Infection | ~$30 | ~$12 | ~$4.20 | ~86% |

| Table 2: Comparative Price Analysis: MCCPDC vs. Average Retail vs. GoodRx for Common Generic Drugs |

| Study Source & Date | Therapeutic Area | Number of Drugs Analyzed | Key Finding: Estimated Annual Savings for Medicare | Source(s) |

| Annals of Internal Medicine, 2022 | General Generics | 77-89 | $3.3 – $3.6 Billion | 3 |

| JCO Oncology Practice, 2023 | Oncology | 9 | $1.06 Billion | 43 |

| Journal of Men’s Health, 2024 | Men’s Health | 15 | $1.3 Billion (for 90-day supply) | 44 |

| OSU Center for Health Sciences, 2023 | Diabetes | 13 | $158 Million (for 90-day supply, ex-Metformin) | 46 |

| Table 3: Summary of Academic Research on Potential MCCPDC Savings for Medicare |

The Empire Strikes Back: Industry Reactions and Strategic Responses

The emergence of the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company has not gone unnoticed by the titans of the pharmaceutical industry. Its transparent pricing model and direct challenge to the status quo have provoked a range of strategic responses from incumbent PBMs, payers, and pharmacies. These reactions, a mixture of defensive maneuvering, competitive adaptation, and strategic alliance-building, paint a vivid picture of a market in flux, forced to reckon with a new and potent disruptive force.

PBMs: The “Cost-Plus” Counter-Offensive

The most direct and revealing reaction has come from the “Big Three” PBMs, which have all launched their own “transparent” or “cost-plus” pricing models in a clear effort to counter the narrative and competitive threat posed by MCCPDC.16

- CVS Caremark, the nation’s largest PBM, unveiled CVS CostVantage. This program claims to establish a more transparent reimbursement model for pharmacies, with pricing based on the drug’s acquisition cost, a defined markup, and a service fee.16

- Express Scripts, Cigna’s PBM, launched its ClearNetwork. This model uses a cost benchmark—the lowest of the Predictive Acquisition Cost (a proprietary figure), National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), or Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC)—to which it adds a flat pharmacy fee and a second fee of up to 15%.48

- OptumRx, the PBM arm of UnitedHealth Group, has introduced programs like Cost Made Clear and the Clear Trend Guarantee, which similarly incorporate elements of cost-plus and pass-through pricing to offer clients more predictable costs.52

However, these initiatives have been met with considerable skepticism. Mark Cuban himself has dismissed them as superficial, stating, “The similarity ends at the name. They haven’t published their costs or pricing”.16 Industry analysts concur, pointing out that these PBM models are not truly analogous to MCCPDC’s. They often rely on ambiguous or inflated cost benchmarks. Using the WAC, which is the manufacturer’s high list price, or even NADAC, which does not account for all off-invoice rebates and discounts, is fundamentally different from using the true, auditable acquisition cost that MCCPDC discloses.54 This allows the PBMs to maintain hidden margins and control over the pricing structure, co-opting the language of transparency without adopting its substance.

Payers and Health Systems: Forging Alliances

While PBMs have mounted a defensive response, a growing number of payers and health systems have chosen to partner with MCCPDC, viewing it as a strategic opportunity to lower costs and increase transparency. These partnerships represent the most significant validation of the Cost Plus model.

The watershed moment came in August 2023, when Blue Shield of California, one of the state’s largest insurers, announced it was dropping CVS Caremark as its primary PBM. It instead moved to an “unbundled” model, partnering with several companies for different functions, including Amazon Pharmacy for delivery and, crucially, MCCPDC to provide a simple, transparent, and more affordable pricing model.17 This move, which the insurer expects will save its members up to $500 million annually, was widely seen as a “warning shot” to the incumbent PBM industry.16

Following Blue Shield’s lead, other major payers have signed on, including Pennsylvania-based Capital Blue Cross and Select Health, the insurance arm of Intermountain Health.16 Furthermore, MCCPDC has expanded its reach into the provider space.

Community Health Systems (CHS), a major national hospital operator, became the first health system to partner with MCCPDC, purchasing drugs like epinephrine and norepinephrine directly to combat high costs and persistent shortages.17

Independent Pharmacies & Patient Advocacy Groups: A Complex Relationship

The relationship between MCCPDC and the nation’s independent pharmacies is nuanced. Initially, a mail-order cash pharmacy could be seen as a direct competitor threatening their already precarious existence.31 However, many independent pharmacists view Cuban as a powerful ally in their existential struggle against the predatory practices of PBMs.31

Recognizing this, MCCPDC has made a concerted effort to turn potential adversaries into partners. It launched the Cost Plus Drugs Affiliate Pharmacy Network and the associated Team Cuban Card.35 This program allows local, independent pharmacies to join the network and offer MCCPDC’s transparent pricing to their own customers. In return, the pharmacies receive a fair and, most importantly, guaranteed dispensing fee—typically $12 per prescription, with higher rates for more complex medications.58 This model directly addresses the independent pharmacies’ biggest grievance: unpredictable and often below-cost reimbursement from PBMs. It effectively levels the playing field, allowing them to compete on price while retaining their local patient relationships.

Patient advocacy groups, meanwhile, have been strong and unequivocal allies. Groups like Angels for Change, a nonprofit dedicated to ending drug shortages, have actively partnered with MCCPDC. In a powerful endorsement of the company’s manufacturing strategy, Angels for Change awarded MCCPDC a grant to proactively produce at-risk oncology drugs, viewing the company as a key partner in building a more resilient domestic supply chain.13

The industry’s multifaceted reaction reveals a battle being fought on two fronts: narrative and network. The PBMs’ launch of “transparent” models is an exercise in narrative co-option, an attempt to blur the lines between their opaque offerings and MCCPDC’s genuinely transparent one. It is a classic defensive strategy by incumbents to confuse the market and slow the disruptor’s momentum. Simultaneously, the decision by Blue Shield of California to “unbundle” its pharmacy benefit services signifies a battle over network structure. It challenges the entire value proposition of the vertically integrated PBMs, which is to sell a single, bundled solution. The market is now being presented with a choice: the all-in-one incumbent network or a new, disaggregated network built from best-in-class partners.

In this context, MCCPDC’s alliance with independent pharmacies appears to be a masterstroke of strategy. It neutralizes a potential source of grassroots opposition and transforms it into a powerful asset. This partnership provides MCCPDC with a physical retail footprint, solving the logistical problem that not all medications are suitable for a mail-order model, without the capital expenditure of building its own stores.58 Politically, it aligns the company with a highly sympathetic group—the local “mom-and-pop” pharmacy—that carries significant weight in policy debates, strengthening Cuban’s hand in the broader fight for reform.

| Feature | Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs (MCCPDC) | Express Scripts ClearNetwork | CVS CostVantage |

| Cost Basis | True, auditable manufacturer acquisition cost. | Lowest of WAC, NADAC, or PAC (proprietary benchmarks, not true cost). | “CVS acquisition cost” (internally determined, not publicly disclosed). |

| Markup Transparency | Flat, public 15% markup. | “Up to 15%” fee with an unspecified split between PBM and pharmacy. | “Set markup” that is not publicly disclosed. |

| Fee Structure | Publicly stated fees ($5 pharmacy labor, $5 shipping). | A flat pharmacy fee (amount not specified). | A service fee (amount not specified). |

| Pharmacy Reimbursement | Guaranteed, transparent dispensing fee for network affiliates ($12-$25). | Unspecified portion of the markup fee; not subject to MAC pricing. | Based on internal cost-plus formula; aims to be more predictable. |

| Data Access for Payers | Full pass-through of data and pricing to B2B clients. | Claims greater transparency, but details are limited. | Claims greater transparency, but details are limited. |

| Table 4: Feature Comparison: MCCPDC vs. PBM “Transparent” Pricing Models |

A Critical Lens: Limitations, Challenges, and the Long-Term Outlook

While the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company has achieved remarkable success in exposing market inefficiencies and providing tangible savings, a comprehensive analysis requires a critical examination of its limitations, the challenges it faces, and its long-term viability. The model, though powerful, is not a panacea for all that ails the U.S. pharmaceutical system.

The Generic Drug Limitation

The most significant and frequently cited limitation of the MCCPDC model is its overwhelming focus on generic drugs.1 While generics constitute the vast majority of prescriptions filled in the United States (approximately 88%), they account for a disproportionately small share of total pharmaceutical spending—less than 20%.3 The primary driver of the nation’s high drug costs is the exorbitant price of patent-protected, brand-name medications.3

MCCPDC has made very limited inroads into this crucial market segment. The reason is structural: the business models of major brand-name manufacturers are deeply enmeshed with the PBM-controlled rebate system. These manufacturers have complex, high-volume contracts with the “Big Three” PBMs that involve paying billions of dollars in rebates to ensure preferential placement on formularies. Engaging with MCCPDC’s transparent, no-rebate model would risk jeopardizing these lucrative arrangements.5 Until MCCPDC can find a way to break this impasse and offer significant savings on high-cost brand-name drugs, its impact on the largest source of patient and systemic financial burden will remain constrained.

The Insurance Paradox

MCCPDC’s initial success was built on a simple cash-pay, direct-to-consumer model that operates largely outside the traditional health insurance system.3 This approach provides radical simplicity and transparency, but it also creates a significant paradox for patients.

When patients pay cash for medications through MCCPDC, these expenditures typically do not count toward their annual insurance deductibles or out-of-pocket maximums.1 For a healthy individual who takes one or two cheap generics, this is a non-issue. But for a patient with chronic conditions who takes multiple medications, including expensive brand-name drugs, this is a major drawback. They might save money on their generics through MCCPDC, but they will still face the full, undiscounted cost of their brand-name drugs until they meet their deductible through other means.

This can also lead to fragmented care. When a patient uses multiple pharmacies—a traditional one for their insurance-covered drugs and MCCPDC for their cash-pay generics—it becomes difficult for any single pharmacist or health plan to maintain a complete and accurate medication history. This fragmentation can increase the risk of dangerous drug interactions and complicates medication reconciliation efforts by providers.31 MCCPDC is attempting to address this by forging partnerships with a growing list of transparent PBMs and health plans, but full integration with the dominant insurance-based system remains a major challenge to its widespread adoption.30

Economic Critiques and Long-Term Viability

The MCCPDC model is not without its economic critics. Some have characterized the venture as a “Band-Aid on a gaping wound”.3 They argue that while it provides a valuable service, it does not address the fundamental drivers of high drug prices, namely the government-granted monopolies via the patent system and the legal prohibition on Medicare negotiating prices for most brand-name drugs. From this perspective, MCCPDC is an elegant workaround for a broken system, but one whose success is predicated on the extreme wealth and public profile of its benefactor, making it an exception that is difficult for others to replicate rather than a scalable solution for the entire market.3

A more cynical economic critique targets the cost-plus model itself. Some economists argue that cost-plus pricing, historically, has not been a mechanism for reducing costs but can instead be “extraordinarily profitable” and may even encourage higher spending by removing incentives for efficiency.48 The concern is that if a cost-plus model were adopted industry-wide without rigorous, independent verification of the “cost” basis, it could simply become a new way to justify high prices. There is also a broader concern that by making long-term drug therapies more affordable, such models could accelerate the shift away from curative, one-time procedures toward “lifetime prescription subscriptions,” potentially increasing total healthcare costs over a patient’s lifetime.48

The Future Trajectory: Evolution and Expansion

Despite these challenges, MCCPDC is not a static entity. Its future trajectory and ability to evolve will be key to its long-term impact. The company is actively pursuing several avenues for growth:

- Brand-Name Drugs: The company has publicly stated its goal is to expand its offerings of brand-name drugs, which is the single most important step it can take to address the core of the drug cost problem.1

- Manufacturing: The investment in the Dallas manufacturing facility is a long-term strategic play. As it ramps up production, it will give MCCPDC greater control over its supply chain, insulate it from price hikes by other generic manufacturers, and position it as a key player in ensuring domestic drug availability.23

- Network Growth: The continued expansion of the Affiliate Pharmacy Network is crucial for creating a hybrid online-and-retail ecosystem. A robust national network of independent pharmacies offering MCCPDC pricing would represent a formidable competitive alternative to the major PBM-owned chains.58

The company faces a version of the classic disruptor’s dilemma. Its initial model was successful precisely because of its simplicity and its decision to operate outside the legacy system. However, to achieve true, system-wide impact, it must integrate with that very system—partnering with employers, health plans, and claims processors. This process of integration inevitably introduces layers of administrative complexity that risk diluting the radical simplicity of its original cash-pay model. The challenge for MCCPDC is to scale its reach and impact without becoming a slightly more transparent version of the entities it set out to destroy.

Ultimately, the long-term success and legacy of the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company may depend less on its ability to sell cheap generics and more on its transformation into a reliable, domestic manufacturer of critical medicines. While the generic drug market is a competitive commodity space where price advantages can be fleeting, the need for a resilient domestic manufacturing base is a pressing and enduring national priority. By building its own facilities and partnering with the government and advocacy groups to combat drug shortages, MCCPDC is constructing a durable competitive advantage built on reliability and quality, not just on price. This could be its most lasting contribution and the true foundation of its long-term viability, making it an indispensable partner for hospitals, government agencies, and the entire U.S. healthcare system.

Conclusion: A Band-Aid or a Catalyst for Systemic Change?

The venture launched by Mark Cuban into the pharmaceutical space has been called many things: a “game changer,” a “disruptor,” and, more skeptically, a “Band-Aid” on a deeply wounded system.3 After a comprehensive analysis of its model, its quantifiable impact, and the industry’s reaction, a nuanced verdict emerges. The Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company is far more than a simple Band-Aid, yet it falls short of being a complete cure. Its most profound legacy may be its role as a powerful catalyst, fundamentally altering the debate and the strategic landscape of U.S. drug pricing.

Synthesizing the Evidence: A Powerful but Incomplete Revolution

The evidence is clear that MCCPDC has been unequivocally successful on several key fronts. First, it has succeeded in dragging the arcane and opaque business practices of Pharmacy Benefit Managers into the public spotlight with unprecedented effectiveness. Through its simple, transparent model, it has provided a stark and easily understandable contrast to the incumbent system, forcing powerful PBMs onto the defensive and compelling them to at least adopt the language of transparency. Second, it has delivered real, often dramatic, savings on a wide range of generic drugs. For uninsured and underinsured patients, it has been a crucial lifeline. For large payers like Medicare, it has demonstrated a potential for billions of dollars in annual savings, providing objective proof of the profound inefficiencies in the current system.

However, the revolution remains incomplete. The company’s impact on the brand-name drug market—the primary engine of high pharmaceutical spending—has been minimal. Its business model, built on bypassing the insurance system, creates practical challenges for patients with comprehensive coverage, whose out-of-pocket payments do not apply to their deductibles. These are not trivial limitations; they define the current boundaries of the company’s disruptive reach.

The Catalyst Effect: Forcing a Market Reckoning

To judge MCCPDC solely on its direct market share would be to miss its most significant contribution. Its greatest impact lies in its role as a catalyst. By building a viable, real-world alternative, it has shattered the industry’s long-held narrative that the current complex system is the only possible way. It has provided a proof-of-concept that has empowered payers like Blue Shield of California to challenge the PBM oligopoly and has given employers and policymakers a tangible model to which they can point. The company has moved the conversation about reform from the theoretical to the practical, forcing a market-wide reckoning that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago.

Final Verdict: More Than a Band-Aid, Less Than a Cure

In the final analysis, the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company is substantially more than a Band-Aid. A Band-Aid merely covers a wound. MCCPDC has performed invasive surgery on a key part of the system—the distribution and reimbursement of generic drugs—while simultaneously running a public diagnostic that has exposed the pathologies afflicting the entire pharmaceutical supply chain.

Yet, it is not a cure. It does not, and cannot, single-handedly solve the problem of government-granted monopoly pricing for brand-name drugs. That requires a different set of tools—the legislative and regulatory power of the state, as embodied in policies like the patent reforms and direct price negotiation authority found in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Mark Cuban’s venture is best understood as a powerful market-based complement to, not a replacement for, broader policy reform. It brilliantly demonstrates both the immense potential and the inherent limits of private sector disruption in a heavily regulated and fundamentally broken market. The future of American drug pricing will not be determined by a single solution, but by the dynamic interplay between innovative business models like the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, which force transparency and competition from the inside, and bold policy interventions that address the structural flaws that private enterprise alone cannot fix.

Works cited

- Mark Cuban is making medication costs an easier pill to swallow | Graduate Studies | MUSC, accessed July 31, 2025, https://gradstudies.musc.edu/about/blog/2024/09/easier-pill-to-swallow

- Comparing Prescription Drugs in the U.S. and Other Countries …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/comparing-prescription-drugs

- Mark Cuban’s Innovative Pharmacy: A Band-Aid on Drug Prices – The Hastings Center for Bioethics, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.thehastingscenter.org/mark-cubans-innovative-pharmacy-a-band-aid-on-drug-prices/

- Datex Blog | How Does The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Work?, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.datexcorp.com/pharmaceutical-supply-chain-2/

- Mark Cuban, Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, on bringing transparency to pharmacy | by Alex Wess | The Pulse by Wharton Digital Health | Medium, accessed July 31, 2025, https://medium.com/wharton-pulse-podcast/mark-cuban-mark-cuban-cost-plus-drug-company-on-bringing-transparency-to-pharmacy-e8aa5d8d7e86

- An Examination of Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Intermediary Margins in the U.S. Retail Channel – HHS ASPE, accessed July 31, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/db1adf86053b1fda8ae9efd01c10ddc8/Pharma%20Supply%20Chains%20Margins%20Report_Final_2024.09.27_Clean_508.pdf

- PBM Basics – Pharmacists Society of the State of New York, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.pssny.org/page/PBMBasics

- Rethinking Community Pharmacy: A Path To A Sustainable Model | Health Affairs Forefront, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/rethinking-community-pharmacy-path-sustainable-model

- The U.S. medicine chest: Understanding the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain and the role of the pharmacist – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7434313/

- Building a resilient medicines supply chain – USP, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.usp.org/supply-chain

- US drug supply chain exposure to China – Brookings Institution, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-drug-supply-chain-exposure-to-china/

- Following the Money: Untangling U.S. Prescription Drug Financing, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/following-the-money-untangling-u-s-prescription-drug-financing/

- Project PROTECT Grant Awarded to Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.angelsforchange.org/news-updates/mark-cuban-cost-plus-drugs-awarded-project-protect-grant

- PBM Regulations on Drug Spending | Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending

- Insurance Topics | Pharmacy Benefit Managers – NAIC, accessed July 31, 2025, https://content.naic.org/insurance-topics/pharmacy-benefit-managers

- Pharm Exec Exclusive: Mark Cuban Talks Drug Pricing – Pharmaceutical Executive, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.pharmexec.com/view/pharm-exec-exclusive-mark-cuban-talks-drug-pricing

- Mark Cuban wants to keep shaking up healthcare. Here’s Cost Plus Drug’s next move, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/health-tech/mark-cuban-wants-keep-shaking-healthcare-heres-cost-plus-drugs-next-move

- Value of PBMs | PCMA – Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.pcmanet.org/value-of-pbms/

- www.commonwealthfund.org, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending#:~:text=PBMs%20negotiate%20with%20drug%20manufacturers,PBMs%20for%20performing%20these%20functions.

- How PBMs Are Driving Up Prescription Drug Costs – The New York Times, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.nacds.org/pdfs/PBMarticle-6-21-24.pdf

- Cutting out the middleman, how Mark Cuban’s online pharmacy saves you money, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/texas/news/mark-cubans-online-pharmacy-saves-you-money-by-cutting-out-middlemen/

- ‘Shark Tank’s’ Mark Cuban backs Trump’s prescription drug …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/mark-cuban-backs-trumps-health-care-executive-order-prescription-drugs

- Mission of Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.costplusdrugs.com/mission/

- Mark Cuban: Health care is a battle of good against bad, and …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/mark-cuban-health-care-is-a-battle-of-good-against-bad-and-doctors-are-the-good-guys

- Mark Cuban: Drug Price Disrupter Explains How It Works – – Conversations on Health Care, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.chcradio.com/episode/Mark-Cuban/744

- Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.markcubancostplusdrugcompany.com/

- Mark Cuban’s New Pharmacy Business and the Future of Drug Pricing, accessed July 31, 2025, https://undark.org/2022/02/21/mark-cubans-new-pharmacy-business-and-the-future-of-drug-pricing/

- Brand-Name Drug Prices: Key Driver of High Rx Spending in US …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/nov/brand-name-drug-prices-key-driver-high-pharmaceutical-spending-in-us

- How Billionaire Mark Cuban Is Trying To Revolutionize Drug Prices In America – YouTube, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDfIObddYKs

- Homepage of Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.costplusdrugs.com/

- Comparing Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC) and Independent Pharmacies – Digital Pharmacist, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.digitalpharmacist.com/blog/mark-cuban-cost-plus-drug-company/

- Blog: Mark Cuban’s Impact on the Pharma Industry – Pharmaoffer.com, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pharmaoffer.com/blog/how-billionaire-mark-cuban-might-turn-the-pharmaceutical-industry-upside-down/

- Questions Frequently Asked and Answers | Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs Company, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.costplusdrugs.com/faq/

- HHS, DARPA link up with Rutgers, Cost Plus Drugs and others in initiative to rethink US drug production – Fierce Pharma, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/hhs-darpa-link-rutgers-cost-plus-drugs-and-others-under-initiative-overhaul-us-drug

- How Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company Is Approaching Drug Pricing Transparency, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugtopics.com/view/how-mark-cuban-cost-plus-drug-company-is-approaching-drug-pricing-transparency

- Community Health Systems to buy drugs from Mark Cuban Cost Plus | Healthcare Dive, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/community-health-systems-mark-cuban-cost-plus-deal/709712/

- Amazon RxPass and Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs vs. Your Health Insurance, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.phpni.com/blog/amazon-rxpass-and-mark-cuban-cost-plus-drugs-vs.-your-health-insurance

- Improving Affordability in Dermatology: Cost Savings in Mark Cuban …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11661688/

- Thoughts on GoodRx and CostPlus Drug Company (Mark Cuban’s Pharmacy )? – Reddit, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Residency/comments/1eulhjw/thoughts_on_goodrx_and_costplus_drug_company_mark/

- Is Cost Plus Drugs Really the Big Bad Wolf? – Retail Management Solutions, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.rm-solutions.com/blog/is-cost-plus-drugs-really-the-big-bad-wolf

- How Mark Cuban’s pharmacy can change how payers handle prescription coverage, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.christenseninstitute.org/blog/how-mark-cubans-pharmacy-can-change-how-payers-handle-prescription-coverage/

- Study Cites Mark Cuban’s Online Pharmacy Model for Price Reform | PYMNTS.com, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.pymnts.com/prescriptions/2022/study-cites-mark-cubans-online-pharmacy-model-for-price-reform/

- Prescription savings across oncology: A cost comparison of Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs pharmacy against 2021 Medicare Part B and Part D claims. – ASCO Publications, accessed July 31, 2025, https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP.2023.19.11_suppl.18

- exploring the impact of the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company model on Medicare savings – Journal of Men’s Health, accessed July 31, 2025, https://oss.jomh.org/files/article/20241230-446/pdf/JOMH2024092701.pdf

- Reducing men’s health drug costs: exploring the impact of the Mark …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.jomh.org/articles/10.22514/jomh.2024.200

- Assessing the Cost-Saving Potential of the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company for Diabetes Medications: A Comparative Study with Medicare Part D Pricing, accessed July 31, 2025, https://scholars.okstate.edu/en/publications/assessing-the-cost-saving-potential-of-the-mark-cuban-cost-plus-d

- Patient-Level Savings on Generic Drugs Through the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, accessed July 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11179122/

- Why the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company Is a Boon for the Pharmaceutical Industry, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.trillianthealth.com/strategy/counterpoint/why-the-mark-cuban-cost-plus-drug-company-is-a-boon-for-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- CVS Caremark leader jabs Cost Plus Drugs; Mark Cuban responds …, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/pharmacy/cvs-caremark-leader-jabs-cost-plus-drugs-mark-cuban-responds/

- Express Scripts’ New Option Models Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/express-scripts-new-option-models-mark-cuban-s-cost-plus-drugs

- Express Scripts follows Mark Cuban’s lead on drug pricing – Becker’s Hospital Review, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/pharmacy/express-scripts-follows-mark-cubans-lead-on-drug-pricing/

- NCPA Reacts to OptumRx Cost-Plus Announcement: Actions Will Speak Louder Than Words, accessed July 31, 2025, https://ncpa.org/newsroom/news-releases/2025/03/20/ncpa-reacts-optumrx-cost-plus-announcement-actions-will-speak

- UnitedHealth’s Optum Rx unveils new drug pricing model | Healthcare Dive, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/optum-rx-drug-pricing-model-guarantee-unitedhealth/716693/

- Drug Channels News Roundup, November 2023 … – Drug Channels, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/11/drug-channels-news-roundup-november.html

- Blue Shield California ditches CVS for Amazon and Mark Cuban’s drug company, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/sacramento/news/blue-shield-california-ditches-cvs-for-amazon-and-mark-cubans-drug-company/

- Express Scripts’ Mark Cuban-Inspired Pricing Model Stokes Skepticism, Intrigue – AIS Health, accessed July 31, 2025, https://aishealth.mmitnetwork.com/blogs/radar-on-drug-benefits/express-scripts-mark-cuban-inspired-pricing-model-stokes-skepticism-intrigue

- Mark Cuban shakes up pharmacy pricing – YouTube, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BK-YE8LMAQ8

- Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs Affiliate Pharmacy Network Aims to Support Independent Pharmacies – Drug Topics, accessed July 31, 2025, https://www.drugtopics.com/view/mark-cuban-cost-plus-drugs-affiliate-pharmacy-network-aims-to-support-independent-pharmacies