Section 1: The Strategic Foundations of Pharmaceutical Pricing

The process by which a pharmaceutical company determines the price of a new drug is a complex calculus, blending economic theory, market analysis, and strategic positioning. It is an exercise that begins long before a product reaches the market and continues throughout its lifecycle. This section deconstructs the core inputs and models that form the basis of this strategy, examining the theoretical frameworks, the economic justifications put forth by the industry, and the significant role of marketing in creating and sustaining price points.

1.1. The Core Pricing Models: A Strategic Toolkit

Pharmaceutical manufacturers employ a range of pricing strategies to balance the dual objectives of profitability and market access.1 While several models exist in theory, their application in the high-stakes pharmaceutical market is nuanced and strategic. The final list price of a new drug is rarely the result of a single, isolated model. Instead, it emerges from a sophisticated blending of approaches, where one model provides the public-facing justification, another sets the competitive boundaries, and a third optimizes revenue across diverse global markets.

Value-Based Pricing (VBP): The Dominant Paradigm for Innovation

Value-based pricing is the predominant framework used to justify the high cost of novel, innovative medicines. This model sets a drug’s price based on its perceived value to patients, providers, and the healthcare system as a whole.1 This value is a function of multiple factors, including the drug’s efficacy, its safety profile, and its impact on a patient’s quality of life (QoL).1 The conceptual formula can be expressed as:

Price=f(Efficacy,Safety,QoL)

The industry champions this approach as a mechanism that rewards and encourages true innovation, arguing that breakthrough therapies that save lives, extend life expectancy, or reduce other healthcare expenditures—such as hospital visits or surgeries—warrant premium prices.3

However, the implementation of VBP is fraught with challenges. A primary obstacle is the difficulty in quantifying “value” and the frequent lack of robust, long-term data at the time of a drug’s launch.1 There is often a lack of methodological guidance on how to incorporate all relevant value elements into a single price point.3 This ambiguity leads to significant discrepancies between the value claimed by a manufacturer and the value perceived by payers and independent assessment bodies.

In many developed countries, such as Germany, Australia, and the United Kingdom, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) bodies are tasked with formally assessing a new drug’s value.6 These organizations, and increasingly U.S.-based entities like the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), use rigorous methodologies, often centered on the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, to determine a fair, value-based price.8 The gap between these assessments and manufacturer launch prices can be vast. One cross-sectional study estimated that applying ICER’s value-based price benchmarks to 73 high-spend drugs in the U.S. would have reduced annual spending on those products from $110.4 billion to just $55.1 billion at the $150,000 per QALY threshold.8 The growing influence of these HTA bodies is undeniable; in a notable case, Sanofi and Regeneron lowered the price of their cholesterol drug, Praluent, following a critical analysis by ICER.2

In the U.S., regulatory frameworks like the Medicaid Best Price rule add another layer of complexity. This rule effectively creates a price floor, making it difficult for manufacturers to offer the deep discounts or refunds required for certain outcomes-based VBP arrangements without triggering significant rebate liabilities across the entire Medicaid program.5

Competitor-Based Pricing: Positioning in the Therapeutic Landscape

While VBP provides the overarching narrative for innovative drugs, competitor-based pricing grounds the strategy in market reality. This approach involves setting a price in relation to existing treatments for the same condition.4 A new drug that demonstrates superior efficacy or an improved safety profile over the current standard of care can command a premium price.12 Conversely, in a therapeutically crowded market with multiple similar options, a new entrant will face intense pressure to price competitively, often at a discount, to gain market share.13

This strategy is particularly critical for “me-too” drugs, which offer incremental improvements rather than breakthrough advances. The pricing decision is a delicate balancing act. If a drug is priced too high relative to its perceived benefit over competitors, payers may refuse to cover it, and physicians may be reluctant to prescribe it.12 If priced too low, it may be perceived as a “discounted form of therapy,” less effective than more expensive, established alternatives.12

The most potent force in competitor-based pricing is the arrival of generic and biosimilar drugs upon patent expiration. This influx of competition is the single greatest driver of price reduction, with studies showing that prices can plummet by 80% to 95% when six or more generic competitors enter a market.14

Cost-Plus Pricing: The Exception, Not the Rule

Cost-plus pricing is the most straightforward model, involving the summation of all costs incurred to produce a drug, plus a predetermined profit markup.11 The formula is simple:

Price=Cost of Production+(Cost of Production×Markup)

Despite its simplicity, this model is almost never used for innovative, branded pharmaceuticals.1 The primary reason is that the direct costs of manufacturing, packaging, and distribution for most drugs, even complex biologics, represent a very small fraction of their final price.11 The largest expense, R&D, is considered a sunk cost that is difficult to allocate on a per-pill basis and, according to some analyses, is often not high enough to justify the astronomical prices of many specialty drugs.11

Recently, however, this model has been thrust into the spotlight by a disruptive market entrant: the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC). By focusing on generic drugs, negotiating directly with manufacturers, and applying a transparent 15% markup plus fixed fees for pharmacy services and shipping, MCCPDC has exposed the vast price discrepancies in the traditional generic market.18 For example, a 30-day supply of the generic cancer drug imatinib costs just $13.40 through MCCPDC, compared to a list price of around $2,500 at other pharmacies.20 Research suggests that if Medicare had purchased generic drugs through this model, it could have saved billions of dollars.21

Differential Pricing: A Global Strategy

Differential pricing involves charging different prices for the same product in different countries or markets.1 This strategy allows manufacturers to maximize global revenue by tailoring prices to local economic conditions, healthcare system structures, and regulatory environments.14 This is the primary reason why drug prices in the United States, with its largely private, fragmented payer system, are consistently two to three times higher than in countries with single-payer systems or government-led price negotiations.6 While profitable, this approach is complex to manage and creates the risk of parallel trade, where intermediaries buy drugs in low-price countries to resell them in high-price markets, undermining the price structure.1

The following table provides a comparative overview of these core pricing models.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Pharmaceutical Pricing Models

| Pricing Model | Core Mechanic | Strategic Application | Key Advantages & Disadvantages |

| Value-Based | Price linked to clinical outcomes (e.g., efficacy, QoL, cost-offsets) | Innovative, first-in-class, or highly differentiated drugs | Adv: Rewards and incentivizes true innovation. Dis: Complex to implement, requires robust data, “value” is subjective and contested. |

| Competitor-Based | Price benchmarked against existing therapies in the same class | “Me-too” drugs, products entering crowded therapeutic areas | Adv: Simple, market-oriented, responsive to competitive landscape. Dis: Can lead to “price-following” and inflation, may not reflect true value. |

| Cost-Plus | Cost of goods sold plus a fixed percentage markup | Primarily generics; used by disruptive, transparent models | Adv: Simple, ensures profitability, highly transparent. Dis: Ignores clinical value and R&D investment, not viable for innovative drugs. |

| Differential | Different prices set for the same drug in different global markets | Global product launches, balancing access and profitability | Adv: Maximizes global revenue, allows for affordability in lower-income markets. Dis: Complex to manage, can lead to parallel trade and arbitrage. |

Sources: 1

1.2. The R&D Investment Calculus: Narrative vs. Reality

The pharmaceutical industry’s primary public justification for high drug prices is the monumental cost and risk associated with research and development.12 This narrative frames high prices not as a matter of profit maximization, but as a necessary condition for the continued discovery of life-saving medicines.

The High-Cost Narrative

According to the industry, bringing a new drug to market is a decade-long, high-risk endeavor.14 The most commonly cited figure for the average cost to develop a new drug is approximately $2.6 billion.11 This figure is an all-inclusive or “fully loaded” cost, which accounts not only for the direct out-of-pocket spending on a successful drug but also capitalizes these costs (i.e., accounts for the return on investment that money could have earned elsewhere) and, crucially, incorporates the massive expenditures on the many drug candidates that fail during development.23 Only about 12% of drugs that enter clinical trials are ultimately approved by the FDA, meaning the revenue from one successful drug must cover the costs of numerous failures.23 In 2019, the industry’s total R&D expenditure was $83 billion 23, and a 2024 analysis by Deloitte calculated the average capitalized cost per asset at $2.23 billion.24

The Counter-Narrative and Conflicting Data

This high-cost narrative is not universally accepted and has been challenged by numerous independent analyses that arrive at significantly lower figures. These studies often criticize the industry-backed estimates for their reliance on confidential, self-reported data and for methodologies that may inflate the final number. For example, one economic evaluation using a model of public and proprietary data estimated the mean expected capitalized cost at $879.3 million.22 An even more recent RAND study, which used publicly available financial data from SEC filings, estimated a median capitalized R&D cost of $708 million.26 The RAND researchers argued that the industry’s high average is heavily skewed by a few “ultra-costly” outliers and that the median cost is a more representative figure for the typical new drug.26 Some critics go further, asserting that the true per-product R&D cost is often much lower and cannot be used to justify the prices of most specialty products.11 This view is bolstered by research that has found no significant association between the R&D investment for a particular drug and the price it is ultimately sold for in the U.S..22

The wide, persistent, and highly contested range of these R&D cost figures suggests that the number itself functions less as a precise accounting metric and more as a powerful strategic tool in the political and public relations arena. The industry’s consistent promotion of the highest possible figures serves to frame the entire policy debate around a stark, binary choice: either accept high prices to fund innovation or impose lower prices and sacrifice the development of future cures. This narrative transforms a specific debate about the price of a given drug into a much broader, more abstract debate about the future of medicine itself, creating a formidable defense against regulatory intervention. The $2.6 billion figure, therefore, is not merely a cost to be recouped; it is a strategic asset deployed to protect the industry’s fundamental pricing freedom.

The following table highlights the significant divergence in R&D cost estimates from various sources.

Table 2: The R&D Cost Spectrum: A Contested Narrative

| Source/Study | Estimated Cost per New Drug (Capitalized) | Methodology Highlights |

| Deloitte (2024) | $2.23 billion | Analysis of R&D budgets from 20 top pharmaceutical companies 24 |

| DiMasi et al. | ~$2.6 billion | Widely cited industry-backed figure using confidential company data; includes cost of failures 11 |

| CBO (2021) | <$1 billion to >$2 billion | Review of existing academic studies and literature 23 |

| Wouters et al. (2018) | $879.3 million | Analytical model using public and proprietary data, including actual clinical trial contracts 22 |

| RAND (2025) | $708 million (median) | Novel method using publicly disclosed R&D spending from SEC filings 26 |

Innovation Elasticity: The Link Between Revenue and R&D

While the absolute cost of R&D is debatable, there is a clear economic relationship between a company’s expected future revenues and its willingness to invest in R&D. This concept, known as the “elasticity of innovation,” measures how responsive R&D activity is to changes in expected market returns.28 Pharmaceutical firms adjust their R&D programs in response to policy changes that may impact future revenues.28 For example, the creation of Medicare Part D expanded the prescription drug market, boosting expected revenues and encouraging investment. Conversely, the IRA’s price negotiation program is expected to shrink the market for certain drugs, thereby reducing R&D incentives.28 Research from the USC Schaeffer Center estimates that a 10% reduction in expected U.S. revenues leads to a 2.5% to 15% decline in pharmaceutical innovation over the long run.28 This linkage is a cornerstone of the industry’s argument against price controls, positing that such measures will inevitably lead to fewer new drugs coming to market.26

1.3. The Marketing Multiplier: Driving Demand and Justifying Price

Alongside R&D, marketing and promotion represent another colossal expenditure for the pharmaceutical industry, one that plays a critical and often underestimated role in the pricing ecosystem. This spending is not merely about informing doctors and patients; it is a strategic investment designed to build brand value, drive demand, and defend high price points against competitive threats.

Quantifying the Spend

The scale of pharmaceutical marketing is immense. In the United States, the industry’s advertising spending has grown so rapidly that it has overtaken the tech sector to become the second-largest ad-spending industry, with an annual investment of around $18 billion.29 Globally, the figure reached approximately $54 billion in 2022.29 Critically, a significant portion of this budget is dedicated to sales and marketing activities that, for many major companies, exceed their total spending on R&D.30 An analysis by the Campaign for Sustainable Rx Pricing (CSRxP) found that just 10 of the largest pharmaceutical companies spent a combined $13.8 billion on advertising and promotion in the U.S. in 2023 alone.30

Strategic Channels of Influence

This marketing budget is deployed through two primary channels:

- Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Advertising: The U.S. and New Zealand are the only developed nations that permit DTC advertising for prescription drugs. This form of marketing has proven highly effective at creating patient-driven demand.30 Patients, influenced by persuasive television, digital, and print ads, often arrive at their physician’s office requesting specific brand-name drugs.31 This puts pressure on physicians to prescribe these often-expensive medications, even when cheaper or equally effective alternatives are available.

- Marketing to Healthcare Professionals (HCPs): A substantial portion of the marketing budget is aimed directly at prescribers. This includes funding armies of pharmaceutical sales representatives who visit doctors’ offices, providing drug samples, and sponsoring educational events.32 Research has established a clear correlation between these promotional activities and physician behavior, linking them to increased prescribing of the promoted drugs, a preference for branded products over generics, and physician requests to add new, expensive drugs to hospital formularies.32

This massive marketing expenditure functions as a powerful competitive moat, protecting the high prices of blockbuster drugs. By building strong brand loyalty and name recognition among both patients and prescribers, a company creates a significant barrier to entry for any competitor. When a new, potentially lower-priced drug enters the market, it must overcome years of sustained marketing investment that has entrenched the incumbent brand in the minds of consumers and the prescribing habits of physicians. This “stickiness” of the established brand slows market share erosion and allows the original product to maintain a significant revenue stream long after its clinical novelty has faded. Consequently, marketing is not just a tool for driving initial sales; it is a long-term defensive strategy that insulates high price points from the full force of market competition.

Section 2: The Architecture of Monopoly: Patents, Exclusivity, and the Patent Cliff

The ability of pharmaceutical companies to command high prices for their products is not an inherent feature of a free market; it is a direct result of a carefully constructed legal and regulatory framework that grants temporary monopolies on new medicines. This architecture of exclusivity, centered on patents and supplemented by regulatory protections, is designed to incentivize the high-risk, high-cost process of drug innovation. This section explores the legal foundations of this monopoly power, examines how these protections are strategically extended, and analyzes the profound economic consequences that occur when they ultimately expire.

2.1. Building the Fortress: The Legal Foundation of Pricing Power

At the core of pharmaceutical pricing power lies a set of government-sanctioned intellectual property (IP) rights that shield a new drug from competition for a defined period.33 This exclusivity allows manufacturers to set prices far above the marginal cost of production, enabling them to recoup their R&D investments and generate profits.35

- Patents as the Cornerstone: The primary instrument of monopoly power is the patent, granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). A patent gives its holder the exclusive right to make, use, sell, and import the patented invention for a term that is typically 20 years from the date of the patent application filing.16 This temporary monopoly is the foundational legal mechanism that prevents generic manufacturers from immediately producing cheaper copies of a new drug.33

- Regulatory Exclusivities: In addition to patents, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) grants separate periods of market exclusivity as a further incentive for innovation, particularly in areas of unmet medical need. These protections are distinct from patents and can run concurrently, offering additional layers of defense against competition.37 Key types of regulatory exclusivity include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A five-year period of data exclusivity for drugs containing a new active moiety, during which the FDA cannot approve a generic version.35

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): A seven-year period of market exclusivity for drugs developed to treat rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.), designed to encourage R&D in commercially less attractive areas.35

- Biologics Exclusivity: A twelve-year period of market exclusivity for novel biologic products, reflecting their complexity and higher development costs.35

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: Enacted in 1984, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, created the modern framework for generic drug competition in the U.S..39 It established a careful balance: on one hand, it created an abbreviated approval pathway for generic drugs (the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA), allowing them to enter the market more quickly after patents expire.43 On the other hand, it compensated brand-name manufacturers for the patent life lost during the lengthy FDA review process by allowing for patent term extensions.38 The Act also established a structured process for patent litigation, which includes a provision that triggers an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for a generic drug if the brand-name company files a patent infringement lawsuit.43

- “Patent Thickets” and “Evergreening”: While the patent system was designed to provide a limited period of monopoly, brand-name drug manufacturers have developed sophisticated strategies to extend this period well beyond the initial 20-year term of the primary patent. This practice, known as “evergreening,” involves filing dozens or even hundreds of secondary patents covering minor modifications to an existing drug.16 These secondary patents can cover new formulations (e.g., an extended-release version), new methods of use (i.e., treating a different disease), or new manufacturing processes.36 This dense, overlapping web of patents creates a “patent thicket” that is legally and financially daunting for a potential generic or biosimilar competitor to challenge, effectively delaying their market entry and prolonging the brand’s monopoly pricing power.16

2.2. Case Study: AbbVie’s Humira and the Art of the Patent Thicket

The case of AbbVie’s blockbuster anti-inflammatory drug, Humira (adalimumab), serves as a quintessential example of the patent thicket strategy in action and its profound impact on competition and healthcare costs.

- Constructing the Thicket: AbbVie meticulously constructed a fortress of intellectual property around Humira. The company filed more than 247 patent applications in the U.S. alone, a figure more than three times the number filed in Europe.50 Critically, a staggering 89% of these U.S. patent applications were filed

after Humira had already received its initial FDA approval in 2002.50 This strategy of layering on secondary patents long after the core invention was developed suggests a primary goal of impeding future competition rather than protecting novel innovation.51 - Impact on Competition: The strategy was remarkably successful. Humira’s primary patent expired in 2016, but the dense patent thicket enabled AbbVie to use litigation and settlement agreements to fend off biosimilar competitors in the U.S. until January 2023—a full seven years later.51 This stands in stark contrast to the European market, where a less permissive patent environment allowed biosimilars to launch in 2018, leading to rapid price competition.50

- Impact on Price and Spending: This extended period of U.S. monopoly power allowed AbbVie to implement a series of aggressive price increases. From its launch in 2003, the list price of Humira was raised 27 times, resulting in a cumulative increase of 470%.51 Between 2012 and 2016 alone, Medicare’s average spending per patient on Humira more than doubled, from $16,000 to nearly $33,000 annually.50 The delay in U.S. biosimilar competition, made possible by the patent thicket, is estimated to have cost the American healthcare system an additional $19 billion.51

2.3. Life After Exclusivity: Navigating the “Patent Cliff”

The very monopoly power that enables blockbuster profits also creates a company’s greatest vulnerability: the “patent cliff.” This term describes the dramatic and often precipitous decline in revenue that occurs when a high-revenue drug loses its patent protection and faces an onslaught of low-cost generic or biosimilar competition.53

- The Economics of the Cliff: The entry of the first generic competitor can capture a significant portion of the market, but the most dramatic price drops occur as more competitors enter. With multiple generic options available, prices can fall by as much as 80-90% within the first year of loss of exclusivity.53 For a blockbuster drug that generates billions in annual sales, this represents a catastrophic loss of revenue that can impact the entire company’s financial health.56

- Historical Precedents and the Modern Cliff: The most iconic example of the patent cliff is Pfizer’s cholesterol drug Lipitor. Once the world’s best-selling medication with peak annual sales of nearly $13 billion, its revenue collapsed to under $3 billion within a few years of its patent expiration in 2011, as generic atorvastatin entered the market at a 90-95% discount.53 The pharmaceutical industry is currently facing what has been described as a patent cliff of “tectonic magnitude,” with an estimated $200 billion to $300 billion in annual revenue at risk between now and 2030.53 Major drugs facing this cliff include some of the best-selling products in the world, such as Merck’s cancer therapy Keytruda, and Bristol Myers Squibb’s and Pfizer’s anticoagulant Eliquis.59

- Corporate Mitigation Strategies: Pharmaceutical companies facing an impending patent cliff deploy a range of defensive strategies to mitigate the financial damage:

- Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A): One of the most common strategies is to acquire other companies, particularly smaller biotechs with promising drugs in their pipelines. This allows the larger company to “buy” new revenue streams to replace the ones it is about to lose.57 AbbVie’s $63 billion acquisition of Allergan was widely seen as a move to diversify its revenue ahead of Humira’s patent cliff.58

- Pipeline Investment and Lifecycle Management: Companies also invest heavily in their internal R&D pipelines to develop the next generation of blockbuster drugs.55 Additionally, they engage in lifecycle management for the expiring drug, such as developing new formulations (e.g., a long-acting injectable to replace a daily pill) or seeking approval for new indications, in an attempt to retain a portion of the market share.57

- Cost-Cutting and Restructuring: In some cases, companies resort to significant cost-cutting measures, including layoffs and operational restructuring, to prepare for the anticipated revenue decline.60

The patent cliff is more than just a series of isolated financial events for individual companies; it is the primary cyclical force that shapes the strategic behavior of the entire biopharmaceutical industry. The existential threat posed by the expiry of a blockbuster drug’s patent compels companies to engage in massive, industry-consolidating M&A deals. This is because replacing billions of dollars in lost revenue through internal R&D alone is often too slow and uncertain. The most direct path to plugging the revenue gap is to acquire it. This creates a predictable cycle where companies with a major patent cliff on the horizon become the dominant buyers in the M&A market, leading to waves of industry consolidation. Simultaneously, to de-risk their future pipelines, these companies are driven to invest heavily in therapeutic areas with the perceived highest potential for future blockbuster success. This results in a “herd investing” phenomenon, where multiple large companies pour billions into the same “hot” areas, such as oncology, immunology, or GLP-1 agonists for obesity, further concentrating market power and R&D focus.63 Thus, the patent cliff acts as a recurring, powerful catalyst that dictates the industry’s strategic direction, driving consolidation and focusing innovation on a narrow band of high-reward targets.

The table below details the patent cliff’s impact on several major blockbuster drugs.

Table 3: Navigating the Patent Cliff: Blockbuster Case Studies

| Drug (Manufacturer) | Peak Annual Sales | U.S. Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) Date | Post-LOE Impact | Key Mitigation Strategy |

| Humira (AbbVie) | $21.2B (2022) | 2023 | Sales fell to $14.0B in 2023 and $9.0B in 2024 | M&A (Allergan); development of next-gen immunology drugs (Skyrizi, Rinvoq) |

| Lipitor (Pfizer) | ~$13B (2006) | 2011 | Sales plummeted by ~71% in one quarter; revenue fell to <$3B | Precedent-setting cliff; led to industry-wide focus on pipeline diversification |

| Keytruda (Merck) | >$29B (2024) | 2028 | Major revenue at risk | Development of subcutaneous formulation; pipeline investment (e.g., Winrevair) |

| Eliquis (BMS/Pfizer) | >$13B (BMS, 2024) | 2026-2028 | Top revenue generator for both companies at risk | Aggressive legal delays; significant cost-cutting and restructuring (BMS) |

Sources: 53

Section 3: The Middle Market Maze: PBMs, Rebates, and the Gross-to-Net Bubble

The final price of a prescription drug is not determined in a simple two-party transaction between the manufacturer and the patient. Instead, it is shaped by a complex and often opaque supply chain populated by powerful intermediaries. Chief among these are Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), whose business practices have come under intense scrutiny for their role in inflating drug costs and creating a vast chasm between a drug’s publicly stated list price and the actual net price received by the manufacturer.

3.1. The Role of the Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM): Gatekeepers of Access

PBMs originated in the 1960s as third-party administrators to help insurers process prescription drug claims.64 Today, they are central players in the pharmaceutical ecosystem, hired by health insurance plans, large employers, and government programs to manage all aspects of their prescription drug benefits.65 Their primary functions include:

- Negotiating Rebates: PBMs negotiate with drug manufacturers to secure discounts, known as rebates, in exchange for favorable placement on their formularies.64

- Formulary Management: They create and maintain formularies, which are tiered lists of covered drugs. A drug’s tier determines the level of patient cost-sharing, thereby incentivizing the use of “preferred” drugs.65

- Pharmacy Network Management: PBMs contract with pharmacies to create a network for plan members and are responsible for reimbursing those pharmacies for dispensed medications.64

The PBM market is defined by immense concentration. The three largest PBMs—CVS Caremark, Express Scripts (owned by Cigna), and OptumRx (owned by UnitedHealth Group)—control approximately 80% of all prescription claims in the U.S..65 This market dominance grants them extraordinary leverage in negotiations with both drug manufacturers, who need access to their millions of covered lives, and pharmacies, who must accept their contract terms to serve insured patients.68

A defining feature of the modern PBM landscape is vertical integration. Each of the “big three” PBMs is now part of a larger healthcare conglomerate that also owns a major health insurer and, in some cases, large specialty and mail-order pharmacies.69 This structure creates significant conflicts of interest, as these integrated entities can design formularies and pharmacy networks that steer patients toward their own affiliated businesses and favor drugs that maximize profit for the parent corporation, rather than minimizing costs for the client and patient.67

3.2. The Rebate System: A System of Perverse Incentives

The rebate system is the primary mechanism through which PBMs exert influence over drug pricing. By controlling formulary access for millions of patients, PBMs can demand substantial rebates from manufacturers.74 A manufacturer’s willingness to provide a large rebate is often the deciding factor in whether its drug is placed on a preferred formulary tier with low patient co-pays, which is essential for driving market share.74

This system, however, contains a perverse incentive that contributes to the inflation of drug prices. Rebates are almost always calculated as a percentage of a drug’s list price, also known as the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC).65 This structure means that a higher list price generates a larger dollar value for the rebate. Consequently, PBMs may be financially incentivized to favor a drug with a high list price and a large rebate over a competitor drug with a lower list price and a smaller rebate, even if the net cost of the latter is lower.65 Manufacturers, in turn, face pressure to set high list prices precisely so they can offer the large rebates demanded by PBMs to secure market access.64

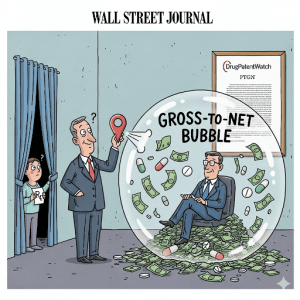

3.3. The Gross-to-Net (GTN) Bubble: The Widening Chasm

The dynamic created by the rebate system has led to a phenomenon known as the “gross-to-net (GTN) bubble”—the vast and growing difference between a drug’s gross revenue (calculated using its high list price) and its net revenue (the actual amount the manufacturer receives after all rebates, fees, and discounts are paid).79

The scale of this bubble is staggering. The Drug Channels Institute estimated that the total value of these gross-to-net reductions for brand-name drugs reached a record $356 billion in 2024.80 This means that, on average, more than half of every dollar of brand-name drug spending at list price is given back in the form of rebates and discounts.

This system has a direct and detrimental impact on patients. A patient’s out-of-pocket costs, particularly co-insurance, are often calculated based on the drug’s inflated list price, not the much lower net price that their insurer ultimately pays after receiving the rebate.78 In effect, patients with high deductibles or co-insurance are paying costs based on an artificially high price, and their payments do not benefit from the substantial discounts negotiated on their behalf. The savings from these rebates are typically retained by the health plan and used to lower overall premiums for all members, rather than being passed on to the sickest patients at the pharmacy counter.83

3.4. Criticisms and Proposed Reforms

The PBM-managed rebate system is subject to widespread criticism for its lack of transparency and its potential for anti-competitive behavior. The precise terms of rebate agreements are considered proprietary trade secrets, making it impossible for clients and policymakers to know how much of a rebate is kept by the PBM versus how much is passed on to the health plan.67 Furthermore, PBMs have been accused of engaging in practices like “spread pricing,” where they charge a health plan a higher price for a drug than they reimburse the pharmacy, and keep the difference as profit.64

In response to these issues, policymakers at both the state and federal levels are considering a range of reforms, including:

- Mandating Transparency: Requiring PBMs to disclose the full value of rebates and the portion they retain.

- Banning Spread Pricing: Prohibiting PBMs from profiting on the spread between what they charge plans and what they pay pharmacies.

- Delinking Compensation: Shifting PBM compensation away from a model based on the percentage of a rebate and toward a flat, fee-for-service model that removes the incentive to favor high-priced drugs.64

The existence of the GTN bubble represents more than just a pricing anomaly; it is a fundamental systemic dysfunction that actively obstructs the transition to a healthcare system based on true value. The core objective of value-based pricing is to align a drug’s cost with its clinical benefit. However, the current rebate system aligns financial incentives with the maximization of rebate volume, which is directly tied to high list prices, not clinical outcomes. This creates a marketplace where the most profitable drug for an intermediary is not necessarily the most cost-effective or clinically superior option for the patient. A manufacturer of a highly innovative drug with a moderate list price may be unable to offer a rebate in absolute dollar terms that is large enough to compete for preferred formulary status against an older, less innovative drug with an inflated list price and a correspondingly massive rebate. In this scenario, the PBM and insurer are financially incentivized to favor the high-list-price drug because the transaction generates more revenue for them. As long as these misaligned incentives persist, any systemic attempt to implement genuine value-based pricing will be fundamentally undermined by the distorted economics of the middle market.

Section 4: The Regulatory Gauntlet: Government Intervention and Price Controls

The regulatory environment is a paramount factor in shaping pharmaceutical pricing strategies. Government policies can range from a hands-off, market-based approach to direct price controls and negotiations. This section contrasts the traditional U.S. system with international models and provides an in-depth analysis of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, a landmark piece of legislation that is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of drug pricing in the United States.

4.1. A Tale of Two Systems: U.S. vs. International Approaches

The global pharmaceutical market is characterized by a stark divide in pricing and reimbursement philosophies, primarily between the United States and other developed nations.

- The U.S. Model: Historically, the U.S. has been unique among developed nations in its reluctance to directly regulate drug prices.6 Manufacturers have had the freedom to set launch prices at whatever level they believe the market will tolerate, a price that is then subject to negotiation with a fragmented network of hundreds of private insurance plans, employers, and their PBMs. This market-based system is often credited by the industry as a key driver of biopharmaceutical innovation, arguing that the potential for high returns is necessary to attract investment in high-risk R&D.85 The consequence of this approach is that U.S. drug prices are, on average, 2.78 times higher than in 33 other high-income countries.13

- European Models (Price Controls & HTA): In contrast, most European countries and other developed nations employ a variety of mechanisms to actively control drug prices.13 These include:

- Health Technology Assessment (HTA): Government-affiliated bodies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom and the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) in Germany, conduct formal evaluations of a new drug’s clinical and economic value.6 These HTA bodies often use metrics like the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) to determine a fair price, which then serves as the basis for national reimbursement negotiations. NICE, for instance, generally considers drugs costing between £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY gained to represent good value for the National Health Service (NHS).9

- External Reference Pricing (ERP): A common practice where a country sets the price for a drug by referencing the prices paid for the same drug in a “basket” of other countries.14 This creates an interconnected global pricing system and is a key driver of manufacturers’ differential pricing strategies.

- Direct Negotiation: Centralized government agencies or single-payer national health systems negotiate prices directly with manufacturers, leveraging their immense purchasing power as the sole buyer for an entire country.7

4.2. The Tectonic Shift: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

Signed into law in August 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) represents the most significant reform of U.S. drug pricing policy in decades. It fundamentally alters the long-standing prohibition on direct government price negotiation for Medicare, the nation’s largest drug purchaser.

The IRA introduced three core provisions aimed at lowering prescription drug costs:

- Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program: For the first time, the law authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to negotiate prices directly with manufacturers for a select number of high-expenditure, single-source drugs that are covered under Medicare Parts B and D and lack generic or biosimilar competition.13 The program is being phased in, starting with 10 Part D drugs for which negotiated prices will take effect in 2026, followed by an additional 15 drugs for 2027, and expanding to include Part B drugs in subsequent years.97 The first 10 drugs selected for negotiation include widely used blockbusters such as Eliquis, Jardiance, Xarelto, and Enbrel, while the second round of 15 drugs includes the popular GLP-1 agonists Ozempic and Wegovy.98

- Inflation Rebates: To curb the common practice of annual price hikes, the IRA requires drug manufacturers to pay a rebate to Medicare if they increase the prices of their drugs faster than the rate of general inflation (CPI-U).96 This provision became effective in 2023.

- Medicare Part D Benefit Redesign: The law significantly redesigns the Medicare Part D benefit to provide greater financial protection for beneficiaries. Most notably, it establishes a $2,000 annual cap on out-of-pocket prescription drug spending for Medicare enrollees, which will take effect in 2025.97 This change shifts a substantial portion of the financial risk for very high-cost drugs from patients to health plans and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

The table below summarizes these key provisions.

Table 4: Key Drug Pricing Provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

| Provision | Core Mechanic | Effective Date(s) |

| Medicare Drug Price Negotiation | HHS negotiates a “Maximum Fair Price” (MFP) for a select number of high-spend, single-source drugs covered by Medicare. | Negotiations began in 2023; first negotiated prices take effect in 2026. |

| Inflation Rebates | Manufacturers must pay a rebate to Medicare if their price increases for a drug outpace the rate of inflation. | Effective for price increases starting in 2023. |

| Part D Out-of-Pocket (OOP) Cap | Annual out-of-pocket prescription drug costs for Medicare Part D beneficiaries are capped at $2,000. | The $2,000 cap takes effect in 2025. |

Sources: 13

4.3. The Ripple Effect: Long-Term Consequences of the IRA

The IRA’s provisions are poised to have profound and far-reaching consequences that extend beyond the Medicare program, reshaping R&D incentives, commercial strategies, and the broader market dynamics of the pharmaceutical industry.

- Impact on R&D Strategy (The “Pill Penalty”): The law creates a disparity in the timeline for negotiation eligibility: 7 years post-approval for small-molecule drugs (typically pills) versus 11 years for biologics.98 This shorter revenue window for small molecules, dubbed the “pill penalty,” creates a strong financial disincentive for investment in their development. As a result, companies are expected to shift their R&D portfolios toward biologics to maximize their period of unconstrained pricing.95

- Impact on Launch and Lifecycle Strategy: The IRA’s negotiation “countdown clock” begins with a drug’s first FDA approval. This may lead to strategic delays in market entry. For instance, a company might hold off on launching a drug for a small, initial indication until it has gathered data for a larger, more lucrative indication to ensure the maximum pre-negotiation revenue period covers the period of highest sales.101

- Spillover to Commercial Markets: Although the IRA’s negotiation authority is legally confined to Medicare, the resulting Maximum Fair Prices will be made public. These government-negotiated prices are expected to become a powerful new reference point for commercial payers, providing them with unprecedented leverage to demand steeper discounts and rebates in their own negotiations.84

- Projected Savings and Innovation Impact: The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the IRA’s drug pricing reforms will reduce the federal deficit by $237 billion over ten years.97 The law’s impact on future innovation remains a subject of intense debate. The CBO offered a modest forecast of a 1% reduction in the number of new drugs coming to market over 30 years.97 A more focused analysis by the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP) on the first 10 negotiated drugs estimated a loss of only 0.62 new drugs from the affected companies, concluding the threat to innovation was minimal.104 In contrast, the pharmaceutical industry and its advocates argue that the reduction in expected revenues will have a much more significant and detrimental effect on R&D investment.28

The complex rules and timelines established by the IRA have triggered a new, high-stakes arms race in competitive intelligence within the pharmaceutical industry. Strategic planning is no longer solely about forecasting clinical success and market share; it now must incorporate sophisticated modeling of “IRA risk.” Companies are compelled to predict which of their pipeline assets—and those of their competitors—are most likely to be selected for negotiation years down the line. This requires a multi-variable analysis of projected Medicare spending, potential timelines for competing generics or biosimilars, and the strategic sequencing of indication launches. This new reality is driving significant investment in advanced data analytics and forecasting capabilities, as companies must now strategically alter their entire development, regulatory, and lifecycle plans to navigate and mitigate the financial impact of this new regulatory paradigm.105

Section 5: The Ecosystem of Influence: Payers, Providers, and Patients

While pharmaceutical manufacturers set the initial list price for a drug, the final price paid and a patient’s access to that medication are determined by a complex interplay among a diverse set of stakeholders. Payers, healthcare providers, and increasingly, organized patient groups all exert significant influence, creating a dynamic ecosystem where pricing is constantly being negotiated, contested, and reshaped.

5.1. The Payer Perspective: The Power of the Purse

Payers are the ultimate purchasers of prescription drugs, and their willingness to cover a product is the final determinant of its commercial success.

- Health Insurers and Employers: These private entities, which provide coverage for the majority of Americans, are the primary clients of PBMs. Their main objective is to manage their overall pharmaceutical spending to control premium costs for their members and employees.66 They exert their power by controlling formulary access. By designating a drug as “preferred” with low patient cost-sharing, they can drive market share to that product. Conversely, by placing a drug on a “non-preferred” tier with high cost-sharing or requiring prior authorization, they can severely limit its use.108

- Government Payers (Medicare/Medicaid): As the largest single purchasers of prescription drugs in the U.S., government programs wield immense market power. Historically, Medicare Part D was legally prohibited from directly negotiating prices, relying instead on private plans and their PBMs. However, programs like Medicaid have always had statutory rebate requirements, such as the “Best Price” rule, which ensures they receive the lowest price offered to any commercial payer.5 With the passage of the IRA, Medicare is now transitioning from a passive price-taker to an active price-setter for a growing list of high-cost drugs, fundamentally altering the balance of power in the market.95

5.2. The Provider Role: Influencers and Purchasers

Healthcare providers are the crucial link between the drug and the patient. While they do not typically bear the direct cost of medications, their decisions and purchasing behaviors are critical drivers of the market.

- Physicians and Prescribers: Physicians are the ultimate arbiters of demand. Their decision to write a prescription is influenced by a complex mix of factors: clinical evidence of a drug’s efficacy and safety, their own clinical experience, a patient’s insurance coverage and formulary status, the anticipated out-of-pocket cost for the patient, and the persuasive efforts of pharmaceutical marketing.13

- Hospitals and Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs): Large health systems and hospitals purchase vast quantities of drugs directly from manufacturers or wholesalers. By consolidating the purchasing volume of many hospitals, GPOs are able to negotiate substantial discounts that are unavailable to smaller purchasers like independent retail pharmacies.108 Their ability to create and enforce their own internal formularies, dictating which drugs are used within their extensive networks, gives them significant leverage in price negotiations.108

5.3. The Rise of the Patient Voice: A New Force in Policy

For decades, the patient’s role in the pricing debate was largely passive. However, a new wave of patient advocacy has emerged, transforming patients from subjects of the healthcare system into powerful political actors.

- The Evolution of Patient Advocacy: The history of patient advocacy is marked by transformative successes, from the HIV/AIDS activism of the 1980s and 1990s that pressured the FDA to accelerate drug approvals, to the rare disease community’s successful lobbying for the Orphan Drug Act.109 These movements established patients as essential partners in the drug development and regulatory process.

- A New Focus on Affordability: In recent years, a new type of patient advocacy group has gained prominence, one focused exclusively on the issue of prescription drug affordability. Organizations like Patients For Affordable Drugs (P4AD) have mobilized a national movement of patients and their families to demand systemic policy changes to lower drug prices.110 A key feature that distinguishes these new groups from many traditional, disease-specific organizations is their policy of refusing all funding from the pharmaceutical industry, thereby ensuring their independence and avoiding conflicts of interest.110

- Impact on Policy: By centering the public debate on the personal stories of individuals and families struggling to afford life-saving medications, these groups have effectively countered the industry’s dominant narrative, which focuses on innovation and R&D costs. They have become a potent political force, successfully lobbying lawmakers and building the public support that was crucial for the passage of the drug pricing reforms in the Inflation Reduction Act.110

The concept of the “patient voice” has become increasingly complex and fragmented. A strategic divergence is now apparent between traditional, disease-specific advocacy groups and the newer, cross-disease organizations focused solely on affordability. The former often receive funding from pharmaceutical companies and may align with industry goals to secure broad access and coverage for a specific high-cost therapy for their condition. The latter, explicitly rejecting industry funding, lobby for systemic price controls that would lower the cost of that same therapy. This creates a complex political dynamic where policymakers are confronted with two distinct and often conflicting “patient voices.” A pharmaceutical company might partner with a specific cancer patient group to advocate for generous coverage of its new, expensive oncology drug. At the same time, an affordability-focused group will be advocating for policies like Medicare negotiation that would directly reduce that drug’s price. This forces a more nuanced policy debate, shifting the question from a simple “should patients have access?” to the more challenging “access at what price?”

Section 6: The Future of Pharmaceutical Pricing: Emerging Models and Strategic Imperatives

The pharmaceutical pricing landscape is in a state of profound flux. The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, coupled with rapid scientific advancements in areas like cell and gene therapy, is challenging traditional pricing models and forcing all stakeholders—manufacturers, payers, and policymakers—to adapt. The future of drug pricing will be defined by a move toward greater granularity, risk-sharing, and an ever-increasing reliance on data to define and defend a product’s value.

6.1. Pricing the Unprecedented: New Models for Curative Therapies

The emergence of potentially curative, one-time treatments, such as cell and gene therapies, presents a unique and acute pricing challenge. These therapies carry unprecedented price tags, with some costing over $3 million for a single administration.112 This creates an immense affordability and budget impact problem for payers, who are asked to pay the full, substantial cost upfront for a therapeutic benefit that is expected to last a lifetime.115 The risk of treatment failure, combined with patient turnover in insurance plans, makes this a financially untenable proposition for many.

In response, innovative contracting models are being developed to better align payment with long-term value. The most prominent of these are Outcomes-Based Agreements (OBAs), also known as value-based contracts.10 Under an OBA, reimbursement for a therapy is directly linked to the achievement of pre-defined clinical outcomes. For example, a manufacturer of a gene therapy for a blood disorder might agree to refund a significant portion of the treatment cost to the payer if the patient fails to remain transfusion-independent for a specified period, such as two years.112 These risk-sharing arrangements help to mitigate the financial uncertainty for payers and ensure they are paying for demonstrated value. The implementation of such agreements in the U.S. has been historically complicated by the Medicaid Best Price rule, but recent regulatory reforms have created more flexibility, making OBAs an increasingly viable option, especially for high-cost therapies.112

6.2. The Push for Granularity: Indication-Specific Pricing (ISP)

A single drug is often approved to treat multiple different diseases, or “indications.” However, the clinical benefit—and thus the value—it provides can vary dramatically from one indication to another. For example, a cancer drug might offer a significant extension of life for patients with lung cancer but only a marginal benefit for those with pancreatic cancer. Indication-Specific Pricing (ISP) is a model that seeks to address this discrepancy by setting different prices for the same drug depending on the indication for which it is used.10

Under an ISP model, the price of the drug would be higher when used for the high-value lung cancer indication and lower when used for the lower-value pancreatic cancer indication, thereby aligning price more closely with value.118 While conceptually appealing, ISP is operationally complex. It requires a sophisticated data infrastructure capable of tracking a drug’s use by indication at the point of dispensing or administration, which is a significant challenge for the current U.S. healthcare system.117 Despite these hurdles, some large PBMs, including Express Scripts and CVS Caremark, have already begun to pilot ISP programs for certain oncology and autoimmune drugs, signaling a clear trend toward more granular, value-aligned pricing.118

6.3. The Data Revolution: HEOR and RWE in Value Assessment

Underpinning the shift toward more sophisticated pricing models is a revolution in the use of data to define and demonstrate value. As payers and HTA bodies demand increasingly rigorous evidence to justify high prices, the role of Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR) has become central to a drug’s commercial strategy.120 HEOR teams are responsible for generating the clinical and economic evidence that forms the basis of a drug’s value proposition.

A critical component of modern HEOR is the growing use of Real-World Evidence (RWE).124 RWE is derived from the analysis of Real-World Data (RWD)—health information collected outside the context of traditional randomized controlled trials, such as from electronic health records, insurance claims databases, patient registries, and wearable devices.124 While clinical trials remain the gold standard for establishing a drug’s safety and efficacy for regulatory approval, RWE provides crucial insights into how a drug performs in a broader, more diverse patient population under real-world conditions.4 This evidence is increasingly vital for convincing payers of a drug’s long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and it is a cornerstone of the data required to support innovative contracts like OBAs.

6.4. Strategic Outlook and Concluding Analysis

The pharmaceutical pricing landscape is undergoing its most significant transformation in decades, driven by the twin forces of legislative reform and scientific innovation. The era of unchecked pricing power in the United States, which has long made it the world’s most profitable market, is drawing to a close. The Inflation Reduction Act has fundamentally altered the strategic calculus for manufacturers, introducing a new and powerful government negotiator into the market and creating a predictable, if unwelcome, endpoint to a blockbuster drug’s period of peak profitability.

In this new post-IRA world, pharmaceutical companies face a set of critical strategic imperatives. They must integrate sophisticated “IRA risk” modeling into every stage of the product lifecycle, from early-stage R&D decisions to post-launch commercial strategy. The ability to generate compelling, data-driven value narratives will be more crucial than ever, requiring substantial and early investment in HEOR and RWE capabilities. Lifecycle management and patenting strategies must now be designed to navigate not only the traditional patent cliff but also the new IRA negotiation clock.

For payers, the IRA provides new leverage. The publicly available Maximum Fair Prices will serve as a powerful new benchmark, likely creating downward price pressure even in the commercial market. For policymakers, the central challenge remains the delicate balancing act between fostering innovation and ensuring affordability. The long-term impacts of the IRA on R&D investment will need to be closely monitored, and further reforms may be necessary to address the persistent, misaligned incentives within the PBM-driven rebate system and the anti-competitive use of patent thickets. Ultimately, the fundamental tension between the price of innovation and the value of access will continue to define the pharmaceutical market for the foreseeable future.

Works cited

- Pharmaceutical Pricing Strategies – Number Analytics, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ultimate-guide-pharmaceutical-pricing

- Short Guide to Value-Based Pricing for Pharmaceuticals – Platforce, accessed July 29, 2025, https://platforce.com/value-based-pricing-for-pharmaceuticals/

- A value-based approach to pricing An EFPIA position paper, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.efpia.eu/media/677284/a-value-based-approach-to-pricing-2.pdf

- 8 Factors Affecting Drug Prices and How to Get Them Right – Unimrkt Healthcare, accessed July 29, 2025, https://unimrkthealth.com/blog/8-factors-affecting-drug-prices-and-how-to-get-them-right/

- Value-based pricing in pharmaceuticals – KPMG International, accessed July 29, 2025, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2016/10/value-based-pricing-in-pharmaceuticals.pdf

- Value-Based Pricing of Prescription Drugs Benefits Patients and Promotes Innovation – Center for American Progress, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/09/ValueDrugPricing-report-1.pdf

- Drug Price Moderation in Germany: Lessons for U.S. Reform Efforts …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/drug-price-moderation-germany-lessons-us-reform-efforts

- Value-Based Pricing of US Prescription Drugs: Estimated Savings Using Reports From the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9856524/

- 4 Economic evaluation | NICE health technology evaluations: the …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/chapter/economic-evaluation-2

- Case Study: Pharmaceutical Pricing and Innovation – July 18, 2018 …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://schaeffer.usc.edu/research/case-study-pharmaceutical-pricing-and-innovation/

- Is the Price Right? An Overview of US Pricing Strategies, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.pharmexec.com/view/price-right-overview-us-pricing-strategies

- How Pharmaceutical Companies Price Their Drugs in the U.S., accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/020316/how-pharmaceutical-companies-price-their-drugs.asp

- Decoding Drug Pricing Models: A Strategic Guide to Market Domination – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/decoding-drug-pricing-models-a-strategic-guide-to-market-domination/

- Global Drug Pricing: Key Factors and Regional Differences – Chemxpert Database, accessed July 29, 2025, https://chemxpert.com/blog/global-drug-pricing-key-factors-and-regional-differences?

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed July 29, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- Increasing Competition To Lower Drug Prices – Patients For Affordable Drugs, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.patientsforaffordabledrugs.org/strategy/increasing-competition/

- Generic Competition and Drug Prices | FDA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/generic-competition-and-drug-prices

- Homepage of Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.costplusdrugs.com/

- Pharm Exec Exclusive: Mark Cuban Talks Drug Pricing – Pharmaceutical Executive, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.pharmexec.com/view/pharm-exec-exclusive-mark-cuban-talks-drug-pricing

- Mark Cuban is making medication costs an easier pill to swallow | Graduate Studies | MUSC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://gradstudies.musc.edu/about/blog/2024/09/easier-pill-to-swallow

- Generic cardiology drug prices: the potential benefits of the Marc Cuban cost plus drug company model – Frontiers, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1179253/full

- Costs of Drug Development and Research and Development Intensity in the US, 2000-2018, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11214120/

- Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126

- Drug development cost pharma $2.2B per asset in … – Fierce Biotech, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/drug-development-cost-pharma-22b-asset-2024-plus-how-glp-1s-impact-roi-deloitte

- Drug Development – HHS ASPE, accessed July 29, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/drug-development

- Typical Cost of Developing a New Drug Is Skewed by Few High-Cost Outliers | RAND, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.rand.org/news/press/2025/01/07.html

- Spending on Phased Clinical Development of Approved Drugs by the US National Institutes of Health Compared With Industry – PMC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10349341/

- Analysis Finds Meaningful Impact on Pharmaceutical Innovation From Reduced Revenues, accessed July 29, 2025, https://schaeffer.usc.edu/research/pharmaceutical-innovation-revenues-drug-prices/

- Great pharmaceutical advertising: It ain’t easy – Kantar, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.kantar.com/uki/inspiration/advertising-media/great-pharmaceutical-advertising-aint-easy

- CSRxP ANALYSIS FINDS BIG PHARMA’S DIRECT-TO … – CSRxP.org, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/csrxp-analysis-finds-big-pharmas-direct-to-consumer-dtc-advertising-costs-u-s-taxpayers-billions-of-dollars/

- Causes and Cures: Stakeholder Perspectives on Rising Prescription Drug Costs in California, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-CausesandCures.pdf

- What influences healthcare providers’ prescribing decisions? Results from a national survey – FDA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/151256/download

- It’s the Monopolies, Stupid – Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/its-monopolies-stupid

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- The Patent Playbook Your Lawyers Won’t Write: Patent strategy development framework for pharmaceutical companies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-patent-playbook-your-lawyers-wont-write-patent-strategy-development-framework-for-pharmaceutical-companies/

- The Power of Patience: Delaying Patents to Enhance Pharma Market Exclusivity, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-power-of-patience-delaying-patents-to-enhance-pharma-market-exclusivity/

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed July 29, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- Hatch-Waxman Letters – FDA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- Hatch-Waxman Litigation 101: The Orange Book and the Paragraph IV Notice Letter, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/insights/publications/2020/06/ipt-news-q2-2020/hatch-waxman-litigation-101

- Hatch-Waxman and Medical Devices – Mitchell Hamline Open Access, accessed July 29, 2025, https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1589&context=wmlr

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Westlaw, accessed July 29, 2025, https://content.next.westlaw.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Pharmaceutical Patent Disputes: Generic Entry for Small-Molecule Drugs Under the Hatch-Waxman Act | Congress.gov, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF13028

- Opinion: Lessons From Humira on How to Tackle Unjust Extensions of Drug Monopolies With Policy – BioSpace, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/policy/opinion-lessons-from-humira-on-how-to-tackle-unjust-extensions-of-drug-monopolies-with-policy

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an American problem | Journal of Law and the Biosciences | Oxford Academic, accessed July 29, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jlb/article/9/2/lsac022/6680093

- COMPETING WITH PATENT THICKETS: ANTITRUST LAW’S ROLE IN PROMOTING BIOSIMILARS – Boston University, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2022/03/HUSTAD.pdf

- Humira – I-MAK, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/i-mak.humira.report.3.final-REVISED-2020-10-06.pdf

- Drug Pricing Investigation – Document Repository, accessed July 29, 2025, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/GO/GO00/20210518/112631/HHRG-117-GO00-20210518-SD007.pdf

- Two decades and $200 billion: AbbVie’s Humira monopoly nears its end | BioPharma Dive, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/humira-abbvie-biosimilar-competition-monopoly/620516/

- The Patent Cliff’s Shadow: Impact on Branded Competitor Drug …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-effect-of-patent-expiration-on-sales-of-branded-competitor-drugs-in-a-therapeutic-class/

- The Patent Cliff: From Threat to Competitive Advantage – Esko, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.esko.com/en/blog/patent-cliff-from-threat-to-competitive-advantage

- The Impact of Patent Cliffs on Biopharmaceutical Companies – PatentPC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/the-impact-patent-cliffs-biopharmaceutical-companies

- The Impact of Drug Patent Expiration: Financial Implications, Lifecycle Strategies, and Market Transformations – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-drug-patent-expiration-financial-implications-lifecycle-strategies-and-market-transformations/

- Big Pharma Prepares for ‘Patent Cliff’ as Blockbuster Drug Revenue Losses Loom, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.tradeandindustrydev.com/industry/bio-pharmaceuticals/big-pharma-prepares-patent-cliff-blockbuster-drug-34694

- Big pharma’s looming threat: a patent cliff of ‘tectonic magnitude’ | BioPharma Dive, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/pharma-patent-cliff-biologic-drugs-humira-keytruda/642660/

- Blockbuster Drugs on Patent Cliffs Research Report 2025 | – GlobeNewswire, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/07/28/3122199/28124/en/Blockbuster-Drugs-on-Patent-Cliffs-Research-Report-2025-2030-Patent-Cliff-to-Be-Largest-Since-2010-Hitting-Blockbusters-Like-Keytruda-Eliquis-and-Darzalex.html

- 5 Pharma Powerhouses Facing Massive Patent Cliffs—And What They’re Doing About It, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/business/5-pharma-powerhouses-facing-massive-patent-cliffs-and-what-theyre-doing-about-it

- 5 Pharma Powerhouses Facing Massive Patent Cliffs—And What …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/business/5-pharma-powerhouses-facing-massive-patent-cliffs-and-what-theyre-doing-about-it/

- Key Business Strategy Tools to Survive a Patent Cliff in the Biopharmaceutical Industry – DASH (Harvard), accessed July 29, 2025, https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstreams/7312037e-7285-6bd4-e053-0100007fdf3b/download

- Biopharma’s Patent Cliff Puts Costs Front and Center – Boston Consulting Group, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/patent-cliff-threatens-biopharmaceutical-revenue

- PBM Regulations on Drug Spending | Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/mar/what-pharmacy-benefit-managers-do-how-they-contribute-drug-spending

- 5 Things To Know About Pharmacy Benefit Managers – Center for American Progress, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/5-things-to-know-about-pharmacy-benefit-managers/

- Learn the Facts About Today’s Drug Pricing System – TruthinRx, accessed July 29, 2025, https://truthinrx.org/learn-facts

- PBM Basics – Pharmacists Society of the State of New York, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.pssny.org/page/PBMBasics

- The Truth About Pharmacy Benefit Managers: They Increase Costs and Restrict Patient Choice and Access – The National Community Pharmacists Association | NCPA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://ncpa.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/ncpa-response-to-pcma-ads.pdf

- A closer look at how health care consolidation drives up patient costs, creates barriers to care | PhRMA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/a-closer-look-at-how-health-care-consolidation-drives-up-patient-costs-creates-barriers-to-care

- PBMs Are Driving Up Drug Costs: The Hidden Dangers of Vertical Integration | Wellyfe, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.wellyferx.com/pbm-vertical-integration/

- How Pharma Can Navigate Ups And Downs Of Vertical Integration In US – executive insight, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.executiveinsight.ch/application/files/9416/1166/3249/In_Vivo_article_nice_layout_for_pdf_download.pdf

- Disadvantaging Rivals: Vertical Integration in the Pharmaceutical Market – National Bureau of Economic Research, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31536/w31536.pdf

- How Vertical Integration and Pricing Manipulation Are Shaping the Biosimilars Market, accessed July 29, 2025, https://smithrx.com/blog/how-vertical-integration-and-pricing-manipulation-are-shaping-the-biosimilars-market

- PBM Rebates Explained: How They Work and What to Know – Xevant, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.xevant.com/blog/pbm-rebates-explained/

- Plaintalk Blog: What is a Drug Rebate? – CIVHC.org, accessed July 29, 2025, https://civhc.org/2022/05/15/plaintalk-blog-what-is-a-drug-rebate/

- Exploring Drug Rebates – Realities and Benefits – Evernorth Health Services, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.evernorth.com/articles/drug-rebates-explained

- The impact of pharmacy benefit managers on community pharmacy: A scoping review – PMC, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10276176/

- Pharmacy Benefit Managers Practices Controversies What Lies Ahead, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/mar/pharmacy-benefit-managers-practices-controversies-what-lies-ahead

- Going Inside the Gross-to-Net Bubble and Its Nuances – Pharmaceutical Commerce, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/going-inside-the-gross-to-net-bubble-and-its-nuances

- Gross-to-Net Bubble Hits $356B in 2024—But … – Drug Channels, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.drugchannels.net/2025/07/gross-to-net-bubble-hits-356b-in.html

- The $250 Billion Gross-to-Net Bubble: What It Is and Why It Exists | Blog | Buy And Bill – BuyandBill.com, accessed July 29, 2025, https://buyandbill.com/the-250-billion-gross-to-net-bubble-what-it-is-and-why-it-exists/

- Shrink the Gross-to-Net Bubble with Trusted Data – Model N, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.modeln.com/blog/shrink-the-gross-to-net-bubble-with-trusted-data/

- The Path of a Rebate: From Drug Companies, through Pharmacy Benefit Companies, to the Employer – and All the Way to Patients – Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.pcmanet.org/rx-research-corner/the-path-of-a-rebate-from-drug-companies-through-pharmacy-benefit-companies-to-the-employer-and-all-the-way-to-patients/12/04/2023/

- Ask an Expert: Drug Pricing in the United States with Courtney Yarbrough | Emory University, accessed July 29, 2025, https://sph.emory.edu/news/ask-an-expert-drug-pricing-courtney-yarbrough

- Don’t Copy European Drug Pricing Policies that Reduced R&D Innovation – Tax Foundation, accessed July 29, 2025, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/drug-pricing-policies/

- International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Estimates Using 2022 Data – HHS ASPE, accessed July 29, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/277371265a705c356c968977e87446ae/international-price-comparisons.pdf

- Health technology evaluation – NHS Innovation Service, accessed July 29, 2025, https://innovation.nhs.uk/innovation-guides/commissioning-and-adoption/health-technology-assessment/

- Technology appraisal guidance – NICE, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-technology-appraisal-guidance

- How does NICE make cost effectiveness decisions on medicines and what are modifiers?, accessed July 29, 2025, https://remapconsulting.com/funding/how-does-nice-make-cost-effectiveness-decisions-on-medicines-and-what-are-modifiers/

- Should NICE’s cost-effectiveness thresholds change?, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.nice.org.uk/news/blogs/should-nice-s-cost-effectiveness-thresholds-change-

- More health lost than gained from NHS spending on new medicines, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.lse.ac.uk/News/Latest-news-from-LSE/2024/l-December-2024/More-health-lost-than-gained-from-NHS-new-medicine-spending

- Impact of European pharmaceutical price regulation on generic price competition: a review, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20515079/

- International reference pricing for prescription drugs | Brookings, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/international-reference-pricing-for-prescription-drugs/

- External Reference Pricing: The Drug-Pricing Reform America Needs? | Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/may/external-reference-pricing-drug-pricing-reform-america-needs

- Medicare Drug Price Negotiations: All You Need to Know | Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2025/may/medicare-drug-price-negotiations-all-you-need-know

- Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Initial Implementation of Medicare Drug Pricing Provisions, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-106996

- Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act – KFF, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/

- FAQs about the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program | KFF, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/faqs-about-the-inflation-reduction-acts-medicare-drug-price-negotiation-program/

- Inflation Reduction Act Research Series: Understanding Development and Trends in Utilization and Spending for Drugs Selected Under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program – HHS ASPE, accessed July 29, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/ira-research-series-medicare-drug-price-negotiation-program

- Effects of the IRA on the pharmaceutical industry – KPMG International, accessed July 29, 2025, https://kpmg.com/us/en/media/news/ira-pharmaceutical-2023.html

- The Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on the Economic Lifecycle of a Pharmaceutical Brand – IQVIA, accessed July 29, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/blogs/2024/09/impact-of-the-inflation-reduction-act

- US drug pricing overhaul: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the …, accessed July 29, 2025, https://pharmaphorum.com/sales-marketing/us-drug-pricing-overhaul-inflation-reduction-act-ira-and-executive-order-eo-most