The term “generic drug” often conjures images of simple imitation—a straightforward process of copying a blockbuster medicine once its patent expires. This perception, however, could not be further from the truth. The reality is that generic drug formulation is a sophisticated, multi-billion-dollar gambit, a discipline that blends rigorous science, astute regulatory navigation, and aggressive legal strategy. It is less about copying and more about meticulous reverse engineering, innovating under constraint, and racing against a clock where every day can mean millions in revenue.

The global generic drug market is a behemoth, valued at approximately $450 billion in the mid-2020s and projected to surge past $700 billion by the early 2030s, driven by a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5% to 8%.1 This is not just a market; it is a fundamental pillar of modern healthcare. In the United States alone, generic drugs account for over 90% of all prescriptions filled, yet they represent only about 18% of total prescription drug spending. This incredible efficiency generated a staggering $408 billion in savings for the U.S. healthcare system in 2022 alone, making the accessibility of these medicines a matter of national economic and public health policy.

This massive economic footprint creates a powerful and inherent tension. On one hand, governments, insurers, and patients demand an ever-increasing supply of low-cost generics to contain spiraling healthcare costs. On the other hand, the scientific and regulatory complexity of developing these drugs is mounting. The low-hanging fruit of simple tablets has been picked, and the future lies in complex formulations, difficult-to-manufacture injectables, and the ultimate challenge: biosimilars. This creates a fundamental conflict between the market’s expectation of rock-bottom prices and the reality of rising development costs and risks.

For the business professionals steering their companies through this landscape—the portfolio managers, the business development executives, the legal strategists—understanding the nuances of formulation is no longer a technical concern to be siloed in the R&D department. It is a core strategic competency. The decisions made at the lab bench directly influence patent litigation outcomes, regulatory approval timelines, and ultimate market success.

This guide is designed for you. It is not a textbook for formulation scientists but a strategic playbook for business leaders. We will dissect the entire generic drug formulation lifecycle, from the initial deconstruction of a brand-name product to the high-stakes bioequivalence trials that determine its fate. We will explore the art of “designing around” a competitor’s patent fortress and navigate the divergent regulatory demands of the world’s largest markets. In a world of intense price erosion and mounting complexity, how does a company strategically formulate a generic drug to not just compete, but to win? This report provides the blueprint.

Part 1: The Foundations – Demystifying the Generic Drug

Before diving into the intricate science and strategy of formulation, it’s essential to establish a firm understanding of what a generic drug is—and what it isn’t. The regulatory definitions and economic principles that govern this sector are not mere formalities; they are the very rules of the game that shape every strategic decision a generic drug developer makes.

What is a Generic Drug, Really?

At its core, a generic drug is a pharmaceutical product that is designed to be a therapeutic equivalent to a brand-name drug that has already been approved and marketed.5 The brand-name product is known in regulatory parlance as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). For a generic to be approved by regulators like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA), it must prove that it is, for all clinical purposes, the same as the RLD.

This “sameness” is defined by a strict set of criteria 5:

- Same Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API): The generic must contain the exact same active ingredient—the chemical compound that produces the therapeutic effect—as the brand.

- Same Strength: If the brand-name tablet is 500 mg, the generic must also be 500 mg.

- Same Dosage Form: If the brand is a tablet, the generic must be a tablet. If it’s a capsule, the generic must be a capsule.

- Same Route of Administration: If the brand is taken orally, the generic must also be taken orally.

Crucially, the generic must also demonstrate bioequivalence. This is a scientific term meaning that the generic drug delivers the same amount of the active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream over the same period of time as the brand-name drug.5 This is the cornerstone of generic approval; it is the evidence that proves the generic will work in the same way and provide the same clinical benefit and risk profile as its reference product.

However, a generic drug is not an identical clone. U.S. trademark laws, for instance, prevent a generic drug from looking exactly like the brand-name product it copies. This means there are permissible differences:

- Inactive Ingredients (Excipients): The fillers, binders, colorings, and flavorings can be different, as long as they are proven to be safe and do not affect the drug’s performance.5

- Appearance: The shape, color, and markings on the pill will almost always be different from the brand.

This leads to the central strategic paradox of generic formulation: the final product must be scientifically the same in its therapeutic performance (bioequivalent) while being legally and compositionally different enough to avoid infringing on the innovator’s secondary patents, which often protect the specific combination of excipients or the manufacturing process. The entire art and science of generic formulation exists within this narrow, challenging space. The formulator’s job is not to simply copy a recipe but to achieve the exact same therapeutic outcome through a different, non-infringing scientific path.

The Economic Engine: Why Generics Matter

The primary reason for the existence and proliferation of generic drugs is cost. Brand-name drugs are notoriously expensive, a direct result of the enormous investment required to bring a new medicine to market. Innovator companies spend billions on research, discovery, extensive preclinical and clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, and massive marketing campaigns to launch their products.7 Patents provide a limited period of market exclusivity—typically 20 years from the filing date—to allow them to recoup these investments and turn a profit.5

Generic manufacturers, on the other hand, operate on a fundamentally different economic model. The landmark Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, created an abbreviated regulatory pathway for generic drugs in the United States.9 This legislation was a masterstroke of policy, balancing the need to incentivize innovation for brand companies with the need to foster competition and lower drug prices.

Under Hatch-Waxman, a generic company does not need to repeat the costly and lengthy clinical trials that the innovator conducted. Instead, they can submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) that relies on the FDA’s previous finding that the RLD is safe and effective. The generic firm’s primary burden of proof is to demonstrate through bioequivalence studies that their product is therapeutically equivalent to the RLD.3

By sidestepping the need for duplicative clinical trials, generic manufacturers can bring their products to market for a fraction of the cost. This allows them to sell their products for 70% to 90% less than the brand-name equivalent, passing enormous savings on to the healthcare system.7

This entire business model is a direct creation of regulatory policy. This makes the generic industry uniquely sensitive to shifts in the legal and regulatory landscape. Any action that complicates the ANDA pathway—whether it’s an innovator’s “patent thicket” strategy designed to bog down challengers in litigation, increased regulatory demands for more complex testing, or new legislation that alters the economic incentives—represents an existential threat to a generic company’s ability to operate. Consequently, for any successful generic firm, regulatory and legal intelligence are not ancillary support functions; they are core business competencies, as vital as the science of formulation itself.

Table: Brand-Name vs. Generic Drugs – A Head-to-Head Comparison

To crystallize these foundational concepts, the following table provides a direct comparison of the key attributes of brand-name and generic drugs.

| Feature | Brand-Name Drug | Generic Drug |

| Active Ingredient | The novel chemical entity discovered and developed by the innovator. | Must be identical to the brand-name drug’s active ingredient.5 |

| Inactive Ingredients | A specific, often patented, combination of excipients. | Can and usually do differ from the brand-name drug.5 |

| Bioequivalence | The benchmark for performance (the Reference Listed Drug). | Must be scientifically proven to be bioequivalent to the brand-name drug.6 |

| Clinical Trials | Requires extensive Phase I, II, and III trials to prove safety and efficacy. | Does not require new clinical trials; relies on the brand’s data.7 |

| Patent Status | Protected by a portfolio of patents (composition of matter, formulation, etc.). | Can only be marketed after the brand’s key patents and exclusivities expire.6 |

| Cost | High, reflecting R&D, clinical trial, and marketing investments. | Typically 70-90% lower than the brand-name drug.7 |

| Appearance | Unique shape, color, and markings protected by trademark. | Must have a different appearance to avoid trademark infringement. |

| Approval Pathway | New Drug Application (NDA) in the U.S.; Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA) in the E.U. | Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) in the U.S.; Generic Application in the E.U..5 |

Part 2: The Blueprint – Pre-Formulation and Reverse Engineering the Originator

The journey of generic formulation does not begin with an act of creation, but with an act of meticulous deconstruction. Before a single excipient is weighed or a tablet is pressed, the formulator must first become an expert on the product they aim to emulate: the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). This phase, encompassing pre-formulation studies and the reverse engineering of the originator product, is the most critical stage for mitigating risk and laying the foundation for a successful, first-cycle regulatory approval.

Starting with the End in Mind: Characterizing the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)

The first principle of generic development is to start with the end in mind. The “end” is a product that is bioequivalent to the RLD. Therefore, the logical first step is to deeply and comprehensively understand the RLD itself. This process, often called “reverse engineering” or “deformulation,” involves systematically taking apart the brand-name drug to understand its composition and performance characteristics. It is the scientific equivalent of a competitor disassembling an iPhone to understand how it works.

This characterization is far more than just a cursory look. It is a deep analytical dive aimed at establishing a precise blueprint of the target. The goal is to achieve what regulators refer to as Q1, Q2, and Q3 similarity:

- Q1 (Qualitative Sameness): Identifying every single inactive ingredient (excipient) present in the RLD formulation.

- Q2 (Quantitative Sameness): Accurately measuring the amount of each excipient in the formulation.

- Q3 (Physicochemical Similarity): Characterizing the physical and chemical properties of the final dosage form that are critical to its performance. This includes measuring its dissolution profile (how quickly it dissolves in different media), its particle size distribution, its polymorphic form (the crystal structure of the API), and other relevant attributes like viscosity or pH for non-solid dosage forms.15

This exhaustive analysis of the RLD is arguably the most important risk-mitigation step in the entire development process. The data gathered from this reverse engineering effort is used to define the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP). The QTPP is a formal document that outlines the desired quality characteristics of the generic drug product. It essentially serves as the “gold standard” or the technical blueprint for the entire formulation project. Every subsequent decision—from which API supplier to use, to which excipients to select, to the parameters for the manufacturing process—is made with the singular goal of creating a product that matches the QTPP.

An incomplete or inaccurate blueprint at this stage means the entire project is flying blind. It dramatically increases the probability of downstream failures, particularly in the pivotal bioequivalence (BE) studies. A failed BE study is a catastrophic event for a generic program, often costing millions of dollars and delaying a product launch by a year or more, by which time the market opportunity may have significantly eroded due to the entry of other competitors. A thorough and precise RLD characterization is the best insurance policy against such a failure.

The Heart of the Matter: Comprehensive API Characterization

Parallel to reverse engineering the final drug product, the formulator must conduct a battery of pre-formulation studies on the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) itself. The intrinsic physical and chemical properties of the API molecule are the primary determinants of the formulation strategy. These studies are designed to understand the API’s strengths, weaknesses, and potential liabilities, which in turn guides the selection of excipients and the manufacturing process needed to create a stable and bioavailable drug product.

Key objectives of API characterization include:

- Solubility Analysis: This is perhaps the most critical factor, as a drug must dissolve to be absorbed. Studies evaluate the API’s solubility in various solvents and across a range of pH values that mimic the journey through the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract.17 Poor aqueous solubility is a common challenge that directly threatens bioavailability and is a primary driver of formulation complexity.

- Polymorphism Screening: Many drug substances can exist in multiple different crystalline forms, a phenomenon known as polymorphism. Each polymorph can have dramatically different physical properties, including solubility, stability, and melting point. Even a minor variation in the crystal structure can significantly alter the drug’s performance. It is absolutely essential to identify the most stable polymorph of the API and ensure that the manufacturing process does not inadvertently convert it to a less stable or less soluble form. A failure to control polymorphism can lead to batch-to-batch inconsistency and disastrous BE study outcomes.

- Stability Studies: The API is subjected to a range of “stress” conditions—elevated temperature, high humidity, and intense light—to identify its potential degradation pathways.17 Does it hydrolyze in the presence of water? Is it sensitive to oxidation? Does it degrade when exposed to light? The answers to these questions are crucial for designing a robust formulation. If the API is prone to oxidation, for example, the formulator knows they must include an antioxidant in the formulation and perhaps use specialized packaging to protect the final product. These early tests help predict the drug’s shelf life and ensure it remains safe and potent over time.

- Particle Size Analysis: The size and shape of the API particles can have a profound impact on both the drug’s dissolution rate and its manufacturability. Smaller particles generally have a larger surface area and dissolve faster, which can be critical for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. However, very fine particles can also be difficult to handle during manufacturing, leading to poor powder flow and content uniformity issues. Optimizing the particle size distribution is a key balancing act between biopharmaceutical performance and manufacturing efficiency.

This wealth of pre-formulation data does more than just inform the scientific development; it is the primary input for the intellectual property strategy. The API’s inherent weaknesses are, paradoxically, the formulation’s greatest opportunities for innovation and for “designing around” the innovator’s patents. For example, if pre-formulation studies reveal that the API has extremely poor solubility, this immediately signals that a solubility-enhancing technology is required. The innovator’s formulation patent likely protects their specific solution to this problem (e.g., using a particular polymer to create an amorphous solid dispersion). Armed with the fundamental knowledge of the API’s core challenge, the generic formulator can then strategically explore a range of alternative, non-infringing technologies—such as using a different class of solubilizing excipients, employing a different particle size reduction technique like nano-milling, or forming a complex with cyclodextrins—to solve the same problem. The pre-formulation data transforms the patent challenge from a legal exercise into a focused, science-driven quest for a novel solution.

Part 3: The Building Blocks – A Practical Guide to APIs and Excipients

With the blueprint from the RLD characterization and a deep understanding of the API’s properties, the formulator can begin the process of constructing the generic product. This involves two critical sets of components: the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), which provides the therapeutic effect, and the excipients, the “inactive” ingredients that make the final dosage form possible. The strategic sourcing, selection, and control of these building blocks are fundamental to ensuring quality, consistency, and regulatory success.

The Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API): Sourcing and Control

The API is the heart of any drug product. It is the biologically active component specifically chosen for its ability to interact with biological targets in the body to produce a desired therapeutic effect, whether that’s relieving pain, lowering blood pressure, or fighting an infection.20 Without the API, a medicine would be nothing more than an inert placebo.

APIs can be derived from various sources. The most common are synthetic APIs, which are manufactured through multi-step chemical synthesis processes. A growing and increasingly important category is biological APIs, which are large, complex molecules like proteins or monoclonal antibodies derived from living organisms using biotechnology.22 The manufacturing of any API is a highly controlled and regulated process involving complex steps of synthesis or fermentation, followed by rigorous purification, isolation, and crystallization to ensure the final “drug substance” meets exacting standards of purity and potency.22

For a generic drug company, the API is more than just a chemical; it is a critical component of the supply chain and a major source of potential business and geopolitical risk. The global API manufacturing landscape is highly concentrated, with a significant over-reliance on a few key countries, particularly China and India, for the production of raw materials and finished APIs. This concentration creates significant supply chain vulnerabilities. Geopolitical tensions, trade disputes, natural disasters, or a quality crisis at a single major foreign supplier can lead to global drug shortages, disrupting a company’s ability to manufacture its products.

Furthermore, the quality of the API is paramount. A seemingly minor change in a supplier’s manufacturing process—a different solvent, a slight temperature variation, a new purification method—can alter the API’s fundamental properties. It could change the impurity profile, introducing new and potentially toxic compounds. It could alter the particle size distribution, affecting the drug’s dissolution rate. It could even change the crystalline form (polymorph), impacting both solubility and stability. Any of these changes could be enough to cause a carefully designed generic formulation to fail its bioequivalence study.

Therefore, a robust API sourcing strategy is a critical business function. It involves much more than simply finding the lowest-cost supplier. A best-in-class strategy includes:

- Dual or Multi-Sourcing: Qualifying and maintaining relationships with at least two independent suppliers from different geographic regions to mitigate supply disruption risk.

- Deep Supplier Audits: Going beyond a simple quality check to deeply understand the supplier’s manufacturing process, controls, and quality culture.

- Rigorous Incoming Testing: Conducting comprehensive analytical testing on every batch of API received to confirm that its physical and chemical properties match the established specifications precisely.

In the generic drug industry, the assumption that “API is API” is a dangerous one. The quality and consistency of this core building block must be obsessively managed to ensure the quality and consistency of the final drug product.

The Unsung Heroes: Understanding Pharmaceutical Excipients

If the API is the heart of the drug, then excipients are the skeleton, circulatory system, and skin that allow it to function. Excipients are pharmacologically inactive substances that are included in a drug formulation to serve a variety of essential purposes, from aiding the manufacturing process to ensuring the stability of the API and controlling its release in the body.25 While the API may constitute only a tiny fraction of a tablet’s total weight, excipients often make up the bulk of the dosage form.

The selection of excipients is a critical part of the formulation process. The formulator must choose a combination of ingredients that are not only compatible with the API (i.e., they don’t cause it to degrade) but that also work together to produce a final product with the desired performance characteristics. Understanding the function of the main categories of excipients is crucial for any professional involved in the generic drug space.

Key categories include 25:

- Fillers (or Diluents): These are used to add bulk or volume to a formulation, which is particularly important when the dose of the API is very small. It is much easier to manufacture a uniform 200 mg tablet than a 2 mg one. Common fillers include lactose, microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), and various starches.

- Binders: As the name suggests, binders are the glue that holds the tablet’s ingredients together after compression. They are critical for ensuring the tablet has adequate mechanical strength to withstand the rigors of manufacturing, packaging, and shipping without crumbling. Common binders include starch, gelatin, and synthetic polymers like povidone (PVP).

- Disintegrants: These excipients are essential for ensuring that a tablet breaks apart quickly when it comes into contact with fluids in the GI tract, allowing the API to be released and dissolved. They typically work by absorbing water and swelling rapidly, causing the tablet to burst. Common disintegrants include croscarmellose sodium, sodium starch glycolate, and crospovidone.

- Lubricants: In high-speed tablet manufacturing, lubricants are added in very small quantities to prevent the powder mixture from sticking to the surfaces of the tablet press punches and dies. This ensures smooth ejection of the tablet and prevents defects. The most common lubricant by far is magnesium stearate.

- Glidants: Glidants are used to improve the flow properties of the powder mixture, ensuring that it can flow evenly and consistently from the hopper into the die cavity of the tablet press. This is critical for maintaining a consistent tablet weight and, therefore, a consistent dose. Colloidal silicon dioxide is a common glidant.

- Coatings: Many tablets are coated for a variety of reasons: to mask an unpleasant taste or odor, to protect the API from light or moisture, to make the tablet easier to swallow, or to control the release of the drug (as in enteric-coated, delayed-release products).

- Other Categories: Depending on the dosage form, many other types of excipients may be used, including preservatives (for liquid formulations), coloring agents, and flavoring agents.

A key trend in modern formulation is the development and use of multifunctional excipients. These are advanced, co-processed ingredients that are engineered to perform several roles simultaneously. For example, a single multifunctional excipient might act as a filler, a binder, and a disintegrant all at once. From a business perspective, this is a significant innovation. Using a multifunctional excipient can lead to a simpler formulation with fewer raw materials to source, qualify, and manage in inventory. It can streamline the manufacturing process by reducing the number of processing steps (e.g., enabling direct compression instead of a more complex granulation process). This can result in significant cost savings, faster production times, and a higher-quality final product. It is a prime example of how formulation science directly impacts operational efficiency and a company’s competitive positioning.

Table: Key Excipient Categories and Their Functions in Formulation

The following table provides a functional summary of the most common excipient categories, translating their scientific roles into business-relevant considerations.

| Category | Function | Common Examples | Strategic Consideration |

| Fillers / Diluents | Increase the bulk of the formulation for ease of manufacturing and handling, especially for low-dose APIs.25 | Lactose, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC), Starch, Dicalcium Phosphate | The choice of filler can impact compressibility and compatibility. Lactose, for example, is cost-effective but can cause issues for lactose-intolerant patients. |

| Binders | Act as an adhesive to hold the tablet together after compression, providing mechanical strength.28 | Starch, Gelatin, Povidone (PVP), Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | Critical for tablet hardness and preventing breakage during shipping. Over-granulation with too much binder can slow down dissolution and negatively impact bioequivalence. |

| Disintegrants | Promote the rapid breakup of the tablet into smaller particles upon contact with GI fluids, facilitating drug release.27 | Croscarmellose Sodium, Sodium Starch Glycolate, Crospovidone | A key determinant of how quickly the drug is released. The choice and amount of disintegrant must be carefully optimized to match the RLD’s dissolution profile. |

| Lubricants | Reduce friction between the tablet and the die wall during the ejection phase of manufacturing.27 | Magnesium Stearate, Stearic Acid, Sodium Stearyl Fumarate | Essential for high-speed manufacturing. However, most lubricants are hydrophobic and can impede tablet dissolution if used in excess. |

| Glidants | Improve the flowability of the powder blend, ensuring uniform filling of the tablet press dies. | Colloidal Silicon Dioxide, Talc | Critical for ensuring consistent tablet weight and, therefore, dose uniformity. Poor flow can lead to batch rejection. |

| Coatings | Provide a protective layer, mask taste, improve appearance and swallowability, or modify drug release (e.g., enteric coating).27 | HPMC (for film coating), Eudragit® polymers (for enteric coating) | A key technology for creating modified-release products and a potential area for “designing around” formulation patents. |

| Solubilizers | Enhance the solubility of poorly water-soluble APIs to improve bioavailability. | Poloxamers, Vitamin E TPGS, Cyclodextrins | Often the most innovative and heavily patented part of a formulation for a challenging API. A primary focus for “design around” efforts. |

Part 4: Engineering the Delivery – A Strategic Look at Dosage Form Design

The combination of API and excipients is ultimately crafted into a final dosage form—the physical entity that the patient consumes. While there are many types of dosage forms (liquids, injectables, topicals), the vast majority of drugs are delivered as oral solids (tablets and capsules). The design of this dosage form is not arbitrary; it is a deliberate act of engineering that controls how, where, and when the drug is released into the body. From a strategic perspective, the choice of dosage form design, particularly between immediate-release and modified-release, is a critical decision that impacts patient compliance, market competition, and a product’s long-term profitability.

Immediate-Release (IR) Formulations: The Workhorse of the Industry

The most common type of oral dosage form is the immediate-release (IR) formulation. As the name implies, these products—conventional tablets and capsules—are designed to release the active drug substance immediately after administration. The goal is to have the tablet or capsule disintegrate quickly in the stomach, releasing the API for rapid dissolution and absorption into the bloodstream, which in turn leads to a relatively fast onset of the drug’s therapeutic effect.30

The manufacturing of IR tablets is a well-established science, typically involving one of three main processes:

- Direct Compression (DC): This is the simplest and most cost-effective method. It involves simply blending the API with the excipients and compressing the mixture directly into tablets. However, DC requires that both the API and the excipients have excellent physical properties, such as good flowability and compressibility, which is not always the case.

- Dry Granulation (or Slugging/Roller Compaction): This method is used for materials with poor flow or compression characteristics. The powder blend is first compressed into large slugs or ribbons, which are then milled down into granules. These granules, which have better flow properties, are then blended with a lubricant and compressed into the final tablets.

- Wet Granulation: This is often the most robust but also the most complex and expensive method. A liquid binder solution is added to the powder blend to form granules. These wet granules are then dried, milled to the desired size, blended with other excipients, and finally compressed into tablets. Wet granulation is very effective at improving the flow and compressibility of difficult materials and ensuring content uniformity.

Even for these seemingly “simple” IR products, the choice of manufacturing process is a strategic decision that involves a careful balancing of cost, speed, and risk. A company with deep expertise in material science might be able to develop a formulation that can be made via direct compression, giving them a significant cost advantage over a competitor who must use the more laborious wet granulation process. Similarly, the adoption of advanced technologies like continuous manufacturing—where raw materials are fed in one end and finished tablets emerge from the other in a seamless flow—can provide a major competitive edge in both cost and quality over companies still relying on older, less efficient batch-based processes.

Modified-Release (MR) Formulations: The Next Frontier of Value

While IR formulations are the industry’s workhorses, modified-release (MR) formulations represent a significant step up in complexity and strategic value. An MR product is one in which the drug-release characteristics—the timing, rate, or location of release—are deliberately altered to achieve a therapeutic objective not offered by a conventional IR form.30 This allows for more sophisticated control over the drug’s pharmacokinetic profile.

There are two main categories of MR oral dosage forms:

- Extended-Release (ER, XR, SR, etc.): These formulations are designed to release the drug slowly over a prolonged period, typically 8, 12, or 24 hours. The primary benefit is a reduction in dosing frequency. A drug that would need to be taken three times a day in an IR form might be taken only once a day in an ER form.30 This dramatically improves patient convenience and adherence to the therapy. It also provides more stable drug concentrations in the blood, avoiding the “peaks and troughs” seen with IR dosing, which can reduce side effects. The technologies to achieve this often involve either a

matrix system, where the API is dispersed within a matrix of a slow-eroding or non-eroding polymer, or a reservoir system, where a core of the drug is coated with a rate-controlling polymer membrane. - Delayed-Release (DR): These formulations release the drug at a time other than immediately after administration. The most common type is an enteric-coated product. The tablet is coated with a special polymer that is insoluble in the highly acidic environment of the stomach but dissolves readily in the more neutral pH of the small intestine. This is used for two main reasons: to protect an API that is unstable in stomach acid, or to protect the stomach lining from an irritating drug (like aspirin).

From a business strategy perspective, the development of MR formulations is a critical tool for both innovator and generic companies. For an innovator company approaching the end of its patent life on an IR product, developing a new, once-daily ER version is a classic “lifecycle management” strategy. The new ER version, with its improved convenience and potential for better tolerability, can be patented separately, allowing the innovator to switch patients to the new product and defend its franchise against the impending wave of generic IR competitors.

For a generic company, this presents both a threat and an opportunity. While the market for the simple IR generic may become rapidly commoditized, the market for a generic version of the more complex ER product will have far higher barriers to entry. Formulating an ER generic is significantly more challenging. It requires a deep understanding of polymer science and drug delivery, and proving bioequivalence is more complex. As a result, the market for a generic ER product will have far fewer competitors, leading to slower price erosion and higher, more sustainable profit margins.

Successfully developing complex MR products is therefore a key strategic pathway for a generic company to move up the value chain. It marks a transition from being a simple “copier” of IR tablets to becoming an innovator in formulation science and drug delivery. This is a crucial step on the path to competing in the lucrative and demanding world of “complex generics.”

Part 5: The Ultimate Test – Proving Bioequivalence (BE) on a Global Stage

After all the meticulous work of reverse engineering, API characterization, and formulation design, the generic drug product must face its ultimate test: the pivotal bioequivalence (BE) study. This is the decisive experiment that determines whether the formulation is a success or a failure. The goal is to generate irrefutable scientific data proving that the generic product performs identically to the brand-name RLD in the human body. Passing this test is the non-negotiable prerequisite for regulatory approval. For companies operating on a global scale, this challenge is magnified by the need to satisfy the often subtly different requirements of major regulatory agencies like the U.S. FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

The Language of Bioequivalence: Understanding Pharmacokinetic (PK) Parameters

Bioequivalence is assessed by comparing the pharmacokinetics (PK) of the generic product (the “Test” product) to the RLD (the “Reference” product). Pharmacokinetics is the study of how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes a drug. In a BE study, this is measured by taking a series of blood samples from study subjects over time after they have taken the drug and measuring the concentration of the drug in their blood plasma.

The resulting data is plotted on a plasma concentration-time curve, from which several key PK parameters are calculated 35:

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration): This is the highest concentration that the drug reaches in the blood. It is a primary indicator of the rate of drug absorption. A Cmax that is too high could indicate a risk of toxicity, while one that is too low might suggest a lack of efficacy.

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): This parameter represents the total exposure of the body to the drug over time. It is calculated from the area under the plasma concentration-time curve. AUC is the primary indicator of the extent of drug absorption.

- Tmax (Time to Maximum Concentration): This is the time at which the Cmax is observed. It provides another measure of the rate of absorption.

For a generic drug to be deemed bioequivalent and thus approved, the regulatory standard is remarkably precise and globally harmonized. The generic company must demonstrate, with 90% confidence, that the bioavailability of its product is within a specific range of the brand-name product. Statistically, this means that the 90% Confidence Interval (CI) for the ratio of the geometric means (Test product / Reference product) for both Cmax and AUC must fall entirely within the acceptance limits of 80.00% to 125.00%.3

This 80-125% window is not an arbitrary range. It is based on decades of clinical and statistical analysis and represents a range within which no clinically significant difference in performance between the two products is expected. If the 90% CI for either Cmax or AUC falls even slightly outside this range (e.g., 79.99% or 125.01%), the study fails, and the product cannot be approved.

Designing the Decisive Experiment: A Look at BE Study Designs

The standard BE study is a masterpiece of scientific control, designed to isolate the performance of the formulation as the only variable. The typical design has several key features 4:

- Study Population: BE studies are usually conducted in a small number of healthy adult volunteers, typically between 24 and 48 subjects. Using healthy subjects minimizes the variability that could be introduced by underlying disease states.

- Study Design: The gold standard is a randomized, single-dose, two-way crossover design. In this design, subjects are randomly assigned to one of two sequences. In the first period, one group receives the Test product, and the other receives the Reference product. After a “washout” period long enough for the drug to be completely eliminated from their bodies, the subjects “cross over” in the second period: the group that received the Test product now receives the Reference, and vice versa. The crossover design is powerful because each subject serves as their own control, which dramatically reduces the impact of inter-subject variability and increases the statistical power of the study to detect a true difference between the formulations if one exists.

- Fasting vs. Fed Conditions: Because the presence of food in the stomach can significantly affect the absorption of many drugs, BE studies are typically conducted under both fasting conditions (overnight fast) and fed conditions (after a standardized, high-fat, high-calorie breakfast). This is done to ensure that the generic product performs equivalently to the brand regardless of whether the patient takes it with or without a meal.

A significant recent development has been the finalization of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) M13A guideline, which has been adopted by the FDA. This new guidance upends the long-standing convention of requiring two separate BE studies (one fasting, one fed) for most immediate-release (IR) solid oral dosage forms. The guidance now recommends that for the majority of these products, bioequivalence can be demonstrated in a single study, typically conducted under fasting conditions, which are considered more sensitive for detecting formulation differences. For a drug that must be taken with food for safety or pharmacokinetic reasons, a single fed study is recommended.

From a business perspective, this is a seismic shift. For a large portfolio of products, this change can cut the clinical development cost and timeline nearly in half. It lowers the barrier to entry for developing certain generics and can accelerate the time to filing an ANDA. However, it also raises the stakes for that single study. With only one shot on goal, the pre-formulation and formulation development work must be even more robust to ensure a successful outcome.

A Tale of Two Agencies: Comparing FDA and EMA Requirements

For any generic company with global ambitions, simply meeting the requirements of one regulatory agency is not enough. The two largest and most influential markets are the United States, regulated by the FDA, and the European Union, regulated by the EMA. While their core principles of bioequivalence are aligned (e.g., the 80-125% acceptance criteria), there are subtle but critical differences in their specific requirements that can have major strategic implications for a global development program.

- Guidance and Product Specificity: The FDA issues a large number of Product-Specific Guidances (PSGs) that provide detailed recommendations for how to design a BE study for a particular drug product.42 The EMA provides a comprehensive overarching “Guideline on the Investigation of Bioequivalence” and is also developing an increasing number of its own product-specific guidances.44 A developer must consult and adhere to these specific guidances for the markets they intend to enter.

- Handling of Highly Variable Drugs: Some drugs naturally exhibit high intra-subject variability (a coefficient of variation >30%) in their pharmacokinetics, making it statistically difficult to meet the standard 80-125% acceptance range for Cmax even if the formulations are equivalent. Both agencies have pathways to address this, typically involving a replicate crossover study design and allowing for a scaled-average bioequivalence approach where the acceptance limits for Cmax can be widened. However, the exact statistical methodologies and the maximum allowable widening can differ between the FDA and EMA, requiring careful study design to satisfy both.

- Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS)-Based Biowaivers: The BCS is a scientific framework that classifies drugs based on their aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability. For certain drugs (typically highly soluble, highly permeable BCS Class 1 drugs), regulators may allow a biowaiver, where an in vivo BE study can be waived in favor of comparative in vitro dissolution testing. This can save enormous time and money. Both the FDA and EMA have guidelines for BCS-based biowaivers, but there have historically been differences in their willingness to grant biowaivers for BCS Class 3 drugs (high solubility, low permeability).40

- Requirements for Complex Dosage Forms: For modified-release products, long-acting injectables, and other complex generics, the BE study requirements are far more intricate than for simple IR tablets. They may involve steady-state studies (where subjects take the drug for several days to reach a stable concentration) in addition to single-dose studies, and the statistical analysis can be more complex. The specific expectations of the FDA and EMA for these complex products can diverge and are often evolving, necessitating early and frequent communication with the agencies.

These regulatory nuances present a critical strategic choice for a company developing a drug for both the U.S. and E.U. markets.

- Option 1: The Global Study. Design a single, comprehensive BE program that is robust enough to satisfy the strictest requirements of both agencies simultaneously. This can be efficient and cost-effective if successful. However, it carries the risk that if the study fails to meet a specific criterion for one agency (e.g., the EMA’s specific statistical approach for a highly variable drug), the entire global filing strategy could be jeopardized.

- Option 2: The Regional Approach. Conduct two separate, tailored BE programs, each optimized to meet the specific requirements of the FDA and EMA, respectively. This approach may be more expensive and time-consuming upfront, but it de-risks the program by isolating a potential failure to a single region, allowing the other filing to proceed on schedule.

The decision between these strategies depends on the company’s risk tolerance, its budget, the specific scientific challenges posed by the drug molecule, and its interpretation of the evolving regulatory landscape. This demonstrates how deep regulatory intelligence is not just a compliance function but a central pillar of global R&D and financial planning.

Table: A Comparative Overview of FDA and EMA Bioequivalence Requirements

This table provides a high-level comparison of key BE requirements, highlighting areas of alignment and divergence that are critical for global strategic planning.

| Parameter | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | European Medicines Agency (EMA) | Key Differences & Strategic Implications |

| Primary Acceptance Criteria | 90% CI for the ratio of geometric means for AUC and Cmax must be within 80.00% – 125.00%. | 90% CI for the ratio of geometric means for AUC and Cmax must be within 80.00% – 125.00%. | Alignment: The core statistical standard is harmonized, forming the basis of global generic development. |

| Highly Variable Drugs (HVDs) | Allows for reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE) for both AUC and Cmax. | Allows for scaled average bioequivalence for Cmax only, with a maximum widening to 70.00% – 143.00% if clinically justified. | Divergence: The EMA’s approach is more restrictive, particularly for AUC. A global study must be designed to meet the EMA’s stricter criteria for AUC while potentially using scaling for Cmax to satisfy both agencies. |

| Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) Drugs | Recommends tightening the acceptance criteria to 90.00% – 111.11% for both AUC and Cmax. Requires a replicate study design. | Recommends tightening the acceptance criteria to 90.00% – 111.11% for AUC. The limit for Cmax can remain 80.00% – 125.00% if justified. | Divergence: The FDA is generally stricter on Cmax for NTI drugs. A global program must target the tightened 90.00% – 111.11% range for both parameters to ensure acceptance in both regions. |

| BCS-Based Biowaivers | Biowaivers are readily considered for BCS Class 1 drugs. Waivers for BCS Class 3 drugs are possible but have stricter requirements regarding excipients. | Biowaivers are readily considered for both BCS Class 1 and Class 3 drugs, provided the formulations are qualitatively and quantitatively very similar. | Opportunity: The EMA’s more permissive stance on BCS Class 3 biowaivers can create a significant cost and time advantage for products targeting the E.U. market first. |

| Fed vs. Fasting Studies (for IR) | Now aligned with ICH M13A, recommending a single study (usually fasting) for most IR products. | Now aligned with ICH M13A, recommending a single study (usually fasting) for most IR products. | Harmonization: This recent alignment is a major win for the industry, streamlining development programs and reducing costs for a large number of products. |

| Reference Product Sourcing | The BE study must use the specific RLD listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. | The BE study must use the reference medicinal product sourced from a major E.U. market (e.g., Germany, UK). | Logistical Challenge: Sourcing the correct reference product for each region is a critical and sometimes complex logistical step that must be planned well in advance. |

Part 6: The Strategic Imperative – Patent Intelligence and the Art of “Designing Around”

In the world of generic pharmaceuticals, science and law are inextricably linked. A brilliant formulation that is perfectly bioequivalent is commercially worthless if it infringes a competitor’s patent. The modern intellectual property (IP) landscape is no longer a simple case of waiting for a single patent to expire. Instead, innovator companies have become masters at constructing complex, multi-layered “patent thickets” designed to delay and deter generic competition for as long as possible. For the generic formulator, navigating this legal minefield is not a task for the lawyers alone; it is a core part of the R&D process itself. The art of “designing around” patents, fueled by sophisticated patent intelligence, is the critical skill that separates market leaders from the litany of failed challengers.

Decoding the Fortress: Understanding the “Patent Thicket”

The patent strategy of a modern innovator pharmaceutical company can be visualized as a medieval fortress. The initial, foundational patent is the composition of matter patent, which claims the new molecular entity (NME) or Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) itself. This is the cornerstone of the fortress, the strongest and broadest form of protection. Its 20-year term establishes the initial period of market exclusivity.

However, a savvy innovator doesn’t stop there. They build a series of outer walls, moats, and gatehouses in the form of numerous secondary patents. This dense and overlapping network of IP is what is known as the “patent thicket”. Its purpose is to protect every conceivable aspect of the drug’s development, formulation, manufacturing, and use. The key types of secondary patents that form this thicket include:

- Formulation Patents: These are of paramount importance to the generic formulator. They do not claim the API itself, but rather the specific “recipe” of the final drug product. This could be a claim to a specific combination of excipients that enhances solubility, a particular coating that improves stability, or a novel extended-release matrix that allows for once-daily dosing.

- Method-of-Use Patents: These patents claim a specific method of using the drug to treat a particular disease. If a company discovers that a drug approved for hypertension is also effective for treating migraines, it can obtain a new method-of-use patent for the migraine indication.

- Process Patents: These protect a specific, novel method of manufacturing the API or the final drug product.

- Polymorph Patents: As discussed earlier, many APIs can exist in different crystalline forms. Innovators will often seek to patent specific, stable polymorphs of their drug, creating another hurdle for generic competitors.

The strategic value of the patent thicket lies not in the individual strength of any single secondary patent—many of which may be weak and vulnerable to legal challenge—but in its cumulative deterrent effect. A generic competitor doesn’t just have to navigate around or invalidate one patent; they may have to confront dozens. This dramatically increases the legal risk, the financial cost, and the time required to bring a generic to market. It transforms the generic launch from a purely scientific endeavor into a complex legal and financial risk assessment, a form of high-stakes economic warfare.

The Formulator’s Playbook: Strategies for “Designing Around” Patents

“Designing around” is the strategic process of developing a product that is bioequivalent to the RLD but does not literally infringe the claims of the innovator’s formulation patents. This is where formulation science becomes a legal tool. The intelligence gathered from a deep analysis of the innovator’s patent portfolio serves as the direct guide for this process.

The legal heart of any patent is its claims. The claims are the numbered sentences at the end of the patent document that define the precise legal boundaries of the invention. They are the “picket fence” that the generic formulator must navigate around. For example, if a patent claim reads: “A pharmaceutical composition comprising API X, excipient A, excipient B, and excipient C”, then a formulation containing API X, excipient A, excipient B, and excipient D would likely not literally infringe that claim.

This may sound simple, but the execution is highly complex. The key is to understand not just what the innovator patented, but why. A competitor’s patent is not just a legal barrier; it is a scientific roadmap in disguise. The “Detailed Description” and “Examples” sections of the patent document are a treasure trove of information that reveals the technical challenges the innovator faced and the specific solutions they chose to overcome them.

Consider this strategic workflow:

- Identify the Problem: The patent’s background and description sections will often explain the core technical problem the invention solves. For instance, it might state that the API is highly prone to degradation via oxidation and that the invention relates to a stabilized formulation.

- Analyze the Patented Solution: The claims and examples will then reveal the innovator’s specific solution. In our example, the patent might claim a formulation containing the API and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), a common antioxidant. The examples would show data demonstrating that the formulation with BHT is significantly more stable than one without it.

- Formulate an Alternative Solution: This intelligence provides the generic formulator with two invaluable pieces of information: first, that controlling oxidation is a critical quality attribute (CQA) for this product, and second, that using BHT is a patented approach. The R&D team’s mission is now clear and focused: find a different, non-infringing way to prevent oxidation. They can then systematically screen alternative, non-claimed antioxidants (such as ascorbic acid or Vitamin E) or explore other strategies like manufacturing under a nitrogen blanket to achieve the same goal of a stable, bioequivalent product.

In another example, if an innovator’s patent for a biologic drug claims a specific combination of sucrose and the amino acid arginine as stabilizers to prevent aggregation at high concentrations, a biosimilar developer’s mission is to find an alternative stabilization system. Their research, guided by the patent’s definition of the problem (high-concentration aggregation), would focus on exploring other classes of well-known protein stabilizers, such as alternative sugars like trehalose or sorbitol, or different amino acids like proline or glycine. This transforms the R&D process from a blind, trial-and-error search into a focused, efficient investigation for a non-infringing solution to a known and well-defined problem.

Leveraging Competitive Intelligence: The Role of Services like DrugPatentWatch

In the modern era of dense patent thickets and global litigation, attempting to manually track and analyze the IP landscape for even a single product is a Herculean task, akin to navigating a minefield blindfolded. The cost of missing a single relevant patent or a key court decision can be catastrophic, leading to a failed launch or a costly infringement lawsuit. This is where specialized competitive intelligence platforms have become indispensable strategic tools.

Services like DrugPatentWatch provide comprehensive, curated databases that are the lifeblood of a modern generic company’s business development and R&D strategy.50 These platforms aggregate and structure vast amounts of data, allowing companies to:

- Conduct Comprehensive Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analyses: An FTO analysis is a deep dive into the IP landscape to determine if a proposed product is at risk of infringing any active patents. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch map the entire portfolio of patents and regulatory exclusivities associated with a target drug, including international equivalents, transforming this complex task into a manageable process.52

- Identify and Track the “Patent Thicket”: These services make it possible to identify every patent associated with an RLD, including secondary patents on formulations, polymorphs, and methods of use, which are often the most critical for “design around” strategies.

- Monitor Patent Litigation: A key feature is the real-time tracking of patent litigation, particularly the Paragraph IV challenges filed by other generic companies under the Hatch-Waxman Act. By monitoring these cases, a company can gain insights into which patents are being challenged, the legal arguments being used, and the potential for early generic entry. This intelligence is vital for timing a market launch and assessing the competitive landscape.

- Extract Formulation Intelligence: Advanced platforms can even be programmed to automatically extract specific pieces of information from within patent documents, such as the excipients mentioned, their concentration ranges, and the stability or dissolution data presented in the examples.48 This accelerates the reverse engineering and “design around” process.

By leveraging these services, a company transforms its patent strategy from a reactive, manual data-gathering exercise into a proactive, data-driven competitive intelligence function. It allows a small, strategic team to perform the work of a large legal and research department, focusing precious R&D resources on opportunities with the highest probability of legal, regulatory, and commercial success. In today’s generic market, sophisticated patent intelligence is not a luxury; it is a non-negotiable requirement for survival and success.

Part 7: The Modern Battlefield – Navigating Today’s Challenges

The generic drug industry, while poised for significant growth, is a fiercely competitive battlefield. The traditional business model of simply being the lowest-cost producer is no longer a guarantee of success. Today’s market is defined by a series of interconnected challenges: relentless pricing pressure that can render products unprofitable overnight, a strategic pivot towards high-risk, high-reward complex generics, and an ever-shifting global regulatory and economic landscape. Successfully navigating this environment requires not only scientific excellence but also extreme operational efficiency and strategic agility.

The Price is (Not) Right: Surviving Intense Pricing Pressure

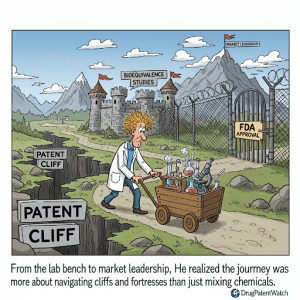

The most brutal economic reality of the generic drug market is the phenomenon of price erosion. The moment a brand-name drug loses its exclusivity, a countdown begins. The market dynamics are predictable and unforgiving 54:

- First Generic Entry: The first generic competitor to launch typically enters the market at a price 30% to 40% below the brand’s price.

- Increased Competition: With the arrival of a second or third competitor, the price war intensifies, and prices can plummet by 50% to 70% from the original brand price.

- Market Saturation: Once six or more generic competitors are in the market, the product becomes fully commoditized. Prices can fall by as much as 95%, compressing profit margins to razor-thin levels.

This steep and rapid price decline has profound strategic implications. It means that speed-to-market is the single most important determinant of profitability. The first generic company to launch, particularly if it has secured the 180 days of market exclusivity awarded to the first successful Paragraph IV patent challenger under the Hatch-Waxman Act, captures the vast majority of the economic value of that product’s lifecycle.3 This 180-day period is a government-sanctioned temporary monopoly that provides a crucial shield against the brutal economics of the commoditized market, allowing the first filer to capture significant market share at a relatively high price point.

Any company that launches 6 to 12 months after the first entrant is arriving at a party that is already over. They are entering a market where prices have already collapsed, and their potential return on investment is a tiny fraction of the first mover’s. This is why every stage of the generic development process—from RLD characterization and formulation to BE studies and regulatory filing—is executed with a relentless sense of urgency. In this environment, a three-month delay in a development program is not just a schedule slip; it is a direct and often devastating hit to the product’s bottom line. The intense pricing pressure also contributes to a more fragile supply chain, as razor-thin margins can lead companies to discontinue less profitable but medically necessary drugs, contributing to national drug shortages.54

The Rise of the Complex Generic: High Risk, High Reward

In response to the commoditization and brutal price erosion in the market for simple oral solid drugs, the strategic focus of the industry has shifted decisively towards complex generics. This is a deliberate move up the value chain, trading the relative simplicity of copying tablets for the higher risks and higher rewards of more scientifically and technically challenging products.54

The FDA defines a “complex generic” as a product that has one or more of the following features :

- Complex active ingredients (e.g., peptides, complex mixtures).

- Complex formulations (e.g., liposomes, long-acting injectables).

- Complex routes of delivery (e.g., topical creams, inhaled products, ophthalmic emulsions).

- Complex drug-device combinations (e.g., auto-injectors, metered-dose inhalers).

The strategic advantage of pursuing these products is clear: their inherent complexity creates much higher barriers to entry. Developing a generic version of an inhaled asthma medication, for instance, requires not only matching the drug’s pharmacokinetic profile but also proving that the delivery device performs identically and produces an aerosol with the same particle size distribution—a massive technical and regulatory hurdle. This difficulty naturally limits the number of competitors who can successfully enter the market, which in turn leads to much slower price erosion and more sustainable, higher profit margins. It is a strategic escape from the commoditization trap.

“The future of the generic drug industry will no longer be defined by simply being the cheapest alternative but by a company’s ability to master a new triad of competitive differentiators. First is the embrace of complexity, both in product development and regulatory navigation. The most significant growth is now concentrated in high-value segments like complex generics (e.g., injectables, inhalables) and biosimilars.”

Many of these complex and value-added medicines are approved via the FDA’s 505(b)(2) pathway. This is a “hybrid” application that sits between a full New Drug Application (NDA) for a novel molecule and an ANDA for a simple generic. It allows a developer to rely on the FDA’s previous findings of safety and efficacy for an approved drug but also requires them to submit new data (often clinical) to support their specific modification (e.g., a new dosage form, strength, or indication). Crucially, because it is an NDA, a product approved via the 505(b)(2) pathway can receive its own period of market exclusivity—typically three years—a benefit not available to traditional generics.

This strategic shift towards complexity represents a fundamental evolution of the generic business model. It is a move away from a model based primarily on manufacturing efficiency and legal aggression to one that is rooted in scientific innovation in formulation, drug delivery, and clinical development. The companies that will thrive in the coming decade are those that are transforming their R&D organizations to resemble nimble, science-driven specialty pharma companies rather than high-volume copiers.

Table: Global Generic Drug Market Size & Growth Forecasts (2025-2034)

Market forecasts from various research firms often differ based on their methodologies, such as the inclusion of biosimilars or different assumptions about price erosion. This table synthesizes multiple credible sources to provide a consolidated and robust view of the market’s economic landscape.

| Research Firm | Base Year & Value (USD B) | Forecast Year & Value (USD B) | CAGR (%) | Forecast Period |

| Precedence Research | 2024: $445.6 | 2034: $728.6 | 5.04% | 2025-2034 |

| Vision Research Reports | 2025: $515.1 | 2033: $775.6 | 5.25% | 2025-2033 |

| Stellar MR | 2024: $453.7 | 2032: $681.6 | 5.22% | 2025-2032 |

| IMARC Group | 2024: $389.0 | 2033: $674.9 | 5.66% | 2025-2033 |

| Mordor Intelligence | 2025: $431.1 | 2030: $530.3 | 4.23% | 2025-2030 |

| BCC Research | 2023: $435.3 | 2028: $655.8 | 8.5% | 2023-2028 |

| Grand View Research | 2022: $361.7 | 2030: $682.9 | 8.3% | 2023-2030 |

| Synthesized Consensus | ~ $450 – $500 B (mid-2020s) | ~ $700 – $800 B (early 2030s) | ~ 5% – 8% | ~ 2025-2034 |

Table: Key Blockbuster Drugs Facing Patent Expiry (2025-2030)

The “patent cliff” is the primary engine of opportunity for the generic drug industry. This table highlights some of the biggest blockbuster products, representing tens of billions of dollars in annual sales, that are expected to lose market exclusivity in the coming years, making the abstract concept of the patent cliff tangible and actionable.

| Brand Name | Active Ingredient | 2023/2024 Sales (USD B) | Primary Indication(s) | Expected Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) Year |

| Keytruda | Pembrolizumab | ~$25.0 | Oncology (various cancers) | 2028 |

| Eliquis | Apixaban | ~$12.9 | Anticoagulation | 2026-2028 |

| Opdivo | Nivolumab | ~$9.3 | Oncology (various cancers) | 2028 |

| Stelara | Ustekinumab | ~$10.9 | Psoriasis, Crohn’s Disease | 2025 |

| Darzalex | Daratumumab | ~$11.7 | Multiple Myeloma | 2029-2030 |

| Xarelto | Rivaroxaban | ~$4.5 | Anticoagulation | 2026 |

| Farxiga | Dapagliflozin | ~$6.0 | Type 2 Diabetes, Heart Failure | 2026 |

| Entresto | Sacubitril/Valsartan | ~$6.0 | Heart Failure | 2025 |

Note: Sales figures are approximate based on recent annual reports. Expected LOE dates are estimates and subject to change based on patent litigation, pediatric exclusivities, and other factors. 1

Part 8: The Horizon – The Future of Generic Formulation

The generic drug industry is in a state of profound transformation. The forces of commoditization, globalization, and technological disruption are reshaping the competitive landscape. The future will belong not to the companies that can simply make the cheapest copies, but to those that can master complexity, leverage cutting-edge technology, and innovate within the constraints of the generic framework. Two areas, in particular, will define the next decade of generic formulation: the biosimilar revolution and the rise of the digital formulator.

The Biosimilar Revolution: The Ultimate Formulation Challenge

If complex generics represent a move up the value chain, then biosimilars represent the ascent to the summit. Biosimilars are the “generic” versions of large-molecule biologic drugs—complex therapeutic proteins, such as monoclonal antibodies, that are manufactured in living cell systems.60 They are the ultimate formulation challenge and the single biggest growth engine for the industry, with the biosimilar segment projected to be a primary driver of the entire market’s expansion.1

Unlike small-molecule drugs, which have a precise, definable chemical structure, biologics are large, intricate, and inherently heterogeneous. Because they are produced by living organisms, it is impossible to create an exact, identical copy. Therefore, the regulatory standard is not “bioequivalence” but “biosimilarity.” The approval pathway, established in the U.S. by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), requires a developer to demonstrate through an extensive “totality of the evidence” approach that their product is “highly similar” to the reference biologic and has “no clinically meaningful differences” in terms of safety, purity, and potency.

This requires a monumental development effort, including:

- Extensive Analytical Characterization: Using a battery of dozens of sophisticated analytical techniques to compare the physicochemical structure and biological function of the biosimilar to the reference product.

- Nonclinical Studies: Comparing the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in animal models.

- Clinical Studies: Often requiring at least one comparative clinical trial in patients to confirm similar efficacy and safety, including an assessment of immunogenicity (the risk of the product provoking an unwanted immune response).

For biosimilars, the mantra is “the process is the product.” A minor, seemingly insignificant change in the manufacturing process—a shift in the pH of the cell culture media, a different purification resin—can alter the final protein’s complex three-dimensional structure or its pattern of post-translational modifications like glycosylation (the attachment of sugar chains). These changes can, in turn, affect the drug’s efficacy or make it more likely to be attacked by the patient’s immune system.

Consequently, “formulating” a biosimilar is not just about combining the final purified protein with excipients in a vial. It is about meticulously controlling every single step of the upstream (cell culture) and downstream (purification) bioprocessing to consistently produce a molecule that is analytically indistinguishable from the reference product. This requires a level of investment in process development, manufacturing infrastructure, and analytical science that is orders of magnitude greater than what is required for small-molecule generics. The barrier to entry is immense, but for the companies that can surmount it, the reward is access to some of the largest and most profitable markets in all of medicine.

The Digital Formulator: AI, Machine Learning, and Continuous Manufacturing

While biosimilars represent a revolution in the what of generic development, a parallel revolution is occurring in the how. A suite of disruptive digital and manufacturing technologies is poised to fundamentally change the way all generic drugs—from the simplest tablets to the most complex biologics—are developed and produced.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): These technologies are moving from the realm of science fiction to practical application in the formulation lab.60 AI algorithms can analyze vast datasets from past experiments, scientific literature, and patent databases to predict which combinations of excipients are most likely to result in a stable, bioequivalent formulation for a given API. This can dramatically reduce the amount of time-consuming and expensive trial-and-error laboratory work. ML models can be used to predict a formulation’s dissolution profile or its in vivo pharmacokinetic performance, allowing formulators to optimize their designs in silico before ever running a costly pilot BE study.

- Continuous Manufacturing (CM): This represents a paradigm shift from traditional batch-based pharmaceutical manufacturing. In a batch process, ingredients are loaded into a vessel, processed, and then unloaded before the next batch can begin. In CM, raw materials are fed continuously into an integrated production line, and finished product emerges in a constant stream. CM offers numerous advantages: a smaller manufacturing footprint, reduced waste, greater operational flexibility, and, most importantly, enhanced quality. The process is monitored in real-time with advanced sensors, allowing for immediate adjustments to be made to keep the process in a state of control. This results in a more consistent and higher-quality product.

These technologies are not just incremental improvements; they are disruptive forces that will create a new class of winners and losers in the generic industry. Companies that make the significant capital investments required to build capabilities in AI-driven formulation and continuous manufacturing will be able to develop higher-quality generic drugs faster and more cheaply than their competitors. They will be able to tackle more complex formulation challenges and increase their probability of first-cycle regulatory approval.

This will create a technological moat, separating the industry leaders from the laggards. Smaller players who cannot afford this investment may find themselves relegated to competing in only the most commoditized, low-margin segments of the market. In the future, a generic company’s competitive advantage will be defined not just by the size of its portfolio or its legal prowess, but by the sophistication of its technology stack.

Conclusion: Your Strategic Formulation Blueprint

The landscape of generic drug formulation has evolved from a relatively straightforward practice of chemical replication into a complex, multi-disciplinary arena of strategic competition. As this guide has detailed, success is no longer guaranteed by simply being the first to file or the cheapest to produce. The modern generic enterprise must operate on a higher plane, mastering a triad of core competencies that together form a blueprint for sustainable market leadership.

First is the imperative of deep scientific expertise. The future of profitable growth lies in embracing complexity—moving decisively up the value chain from simple, commoditized tablets to modified-release formulations, complex injectables, and the ultimate challenge of biosimilars. This requires an R&D organization that is not a mere copycat but a true innovator in formulation science, polymer chemistry, and drug delivery engineering. The meticulous reverse engineering of the Reference Listed Drug is the foundational act of this scientific process, a critical investment that de-risks the entire development program and maximizes the probability of first-cycle bioequivalence success.

Second is the necessity of astute regulatory navigation. The global regulatory environment is a complex mosaic of harmonized principles and critical local nuances. A successful global strategy depends on the ability to design development programs that can satisfy the often-divergent demands of agencies like the FDA and EMA. This requires not just a compliance mindset but a proactive, strategic approach to regulatory affairs, anticipating hurdles and optimizing pathways to accelerate time-to-market.

Third, and perhaps most critically in today’s environment, is the mastery of sophisticated patent intelligence. The innovator’s “patent thicket” is the primary battlefield. Victory belongs to those who can use a competitor’s patent portfolio not just as a set of legal barriers, but as a scientific roadmap to guide the “design around” process. This is a non-negotiable competency that requires leveraging advanced competitive intelligence platforms to transform raw patent data into actionable R&D strategy, turning a legal threat into a competitive advantage.

Ultimately, the journey from lab bench to market leadership in the generic drug industry is a race. It is a race against the unforgiving curve of price erosion, where speed-to-market dictates profitability. It is a race to master complexity, where scientific and technical barriers to entry create defensible, high-value market positions. And it is a race to innovate, where the adoption of new technologies like AI and continuous manufacturing will define the next generation of industry leaders. The companies that thrive will be those that understand that in this dynamic arena, formulation is not just a scientific function—it is the engine of their entire business strategy.

Key Takeaways

- Formulation is Strategy: Your choice of excipients and manufacturing process is a direct response to the innovator’s patent landscape and your primary tool for creating a non-infringing, bioequivalent product. It is a core business decision, not just a technical one.

- Reverse Engineering De-Risks Development: Meticulous characterization of the Reference Listed Drug (RLD) to define a Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) is the single most important investment to increase the probability of first-cycle bioequivalence success and accelerate time-to-market.

- Speed is Profit: In a market defined by rapid and severe price erosion, the first generic to market (especially one with 180-day exclusivity) captures the overwhelming majority of the economic value. Every stage of the development process must be optimized for speed.

- Embrace Complexity: The future of profitable and sustainable growth in the generic industry lies in complex products—modified-release formulations, injectables, drug-device combinations, and biosimilars—that have higher scientific and manufacturing barriers to entry, leading to less competition and slower price erosion.

- Patent Intelligence is Non-Negotiable: You cannot compete effectively in the modern pharmaceutical landscape without a sophisticated, platform-based approach (e.g., DrugPatentWatch) to analyzing patent thickets, identifying “design around” opportunities, and monitoring competitor litigation in real-time.

- Global is the Default, but Nuance is Key: While aiming for global development programs, be prepared for critical differences between major regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA. These nuances in requirements can significantly impact study design, cost, and timelines, demanding a flexible and informed global strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. For a “simple” immediate-release tablet, how much can the formulation really differ from the brand and still be bioequivalent?

This is a crucial question that gets to the heart of formulation science. While the active ingredient and the ultimate clinical performance (as measured by rate and extent of absorption) must be the same, the formulation itself can be quite different. A generic formulator can use different types and amounts of fillers, binders, and disintegrants, as long as these changes do not alter the drug’s pharmacokinetic profile. The key is understanding the “excipient sensitivity” of the drug. For some robust APIs, large changes in the excipient composition may have no effect on absorption. For others, a minor change in the grade of a single excipient could cause the product to fail bioequivalence. This is why pilot studies and a deep understanding of the API’s properties from pre-formulation work are so critical. The goal is to find the most efficient and cost-effective non-infringing formulation that still produces a bioequivalent product.

2. What is the single biggest mistake a company makes when challenging a brand-name drug’s patents with a Paragraph IV filing?