Part I: The Foundation and Framework of the PTAB

Section 1: The Genesis of the Modern Patent Challenge System

1.1 The Pre-AIA Landscape and the Call for Reform

Prior to 2011, the United States patent system faced a growing crisis of efficiency and confidence. While administrative pathways to challenge an issued patent existed—namely ex parte and inter partes reexamination—they were widely seen as inadequate to handle the complexities and volume of modern patent disputes. The primary forum for resolving validity challenges was U.S. district court litigation, a process notorious for its high costs, protracted timelines, and uncertain outcomes.1 Litigating a patent case to a final judgment could take several years and incur legal costs often exceeding a million dollars.1

This environment created significant barriers to innovation. For entities accused of infringement, the sheer expense of a court battle often made challenging a weak or “improperly granted” patent economically unfeasible. This situation was particularly exploited by a rising number of Non-Practicing Entities (NPEs), often pejoratively labeled “patent trolls”.1 These entities, which do not produce goods or services, amass patent portfolios primarily for litigation and licensing purposes. They were accused of leveraging low-quality patents to file or threaten lawsuits against operating companies, knowing that the high cost of defense would compel many to agree to nuisance-value settlements, regardless of the patent’s merits.2 By the time Congress acted, NPEs were reportedly responsible for over 60% of all U.S. patent lawsuits, imposing a direct cost of $29 billion annually on legitimate businesses.2

This confluence of factors—inefficient administrative reviews, prohibitive litigation costs, and the strategic use of questionable patents—led to a broad consensus that reform was necessary. Congress identified a clear need for a centralized, lower-cost, and more efficient administrative system to adjudicate patent validity, with the express goals of improving overall patent quality and reducing unwarranted litigation.1

1.2 The America Invents Act (AIA): A Landmark Legislative Overhaul

The legislative response to this crisis was the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) of 2011, widely regarded as the most significant overhaul of U.S. patent law in more than half a century.1 The AIA’s passage was a rare moment of overwhelming bipartisan consensus, sailing through both chambers of Congress before being swiftly signed into law.2 This indicated a shared understanding across the political spectrum that the existing system was hindering, rather than promoting, technological and economic progress.

The AIA enacted several fundamental changes. Most famously, it transitioned the U.S. from a “first-to-invent” patent system to a “first-inventor-to-file” system, aligning it with the rest of the world and simplifying priority disputes.1 However, its most practically significant change was the creation of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).1

Established on September 16, 2012, the PTAB is an administrative tribunal within the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) that replaced the former Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI).6 The AIA endowed the PTAB with the authority to conduct new, trial-like administrative proceedings designed specifically to be faster and more cost-effective alternatives to district court litigation for challenging the validity of issued patents.1

1.3 Core Objectives of the PTAB Framework

The creation of the PTAB was driven by three core objectives that directly addressed the perceived failings of the prior system:

- Improving Patent Quality: The primary legislative goal was to enhance the quality and reliability of U.S. patents.1 The underlying premise was that the USPTO, despite its best efforts, sometimes issued “bad patents” that did not meet the statutory requirements of novelty and non-obviousness. The PTAB was designed to serve as a powerful post-grant corrective mechanism to review and invalidate these patents, thereby strengthening the integrity of the patent system as a whole.2

- Reducing Litigation Costs and Inefficiency: The PTAB was explicitly intended to be a faster and more affordable venue for validity disputes.1 The new trial proceedings, such as

Inter Partes Review (IPR), are statutorily required to reach a final determination within one year of institution (with a possible six-month extension for good cause), a stark contrast to the multi-year timeline of federal court cases.1 Legal costs for a PTAB trial are typically in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, a fraction of the millions often required for district court litigation.1 - Providing an Expert Forum: A key feature of the PTAB is that its cases are decided by panels of Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) who possess both legal and technical expertise.9 This contrasts sharply with district court litigation, where complex technical arguments are often presented to generalist judges and lay juries. The belief was that a tribunal of experts would be better equipped to make accurate and consistent decisions on the complex technical questions inherent in patent validity challenges.9

The establishment of the PTAB represented more than a mere procedural adjustment; it signaled a fundamental philosophical shift in the nature of a U.S. patent. Historically, a patent granted by the USPTO was treated as a robust property right, enjoying a strong presumption of validity in court that could only be overcome by “clear and convincing evidence”.1 This framework treated the patent grant as a nearly final government act. The AIA disrupted this model by creating a powerful administrative body that operates without a presumption of validity and uses a lower “preponderance of the evidence” standard to invalidate patents.13 This change implicitly reframed the patent grant not as a final property right, but as a “public franchise” subject to ongoing administrative scrutiny. The Supreme Court later made this explicit in its

Oil States decision, ruling that an IPR is simply a “reconsideration of that grant” of a public right.23 This ideological transformation from a “private property” to a “public franchise” model lies at the heart of the intense and persistent controversy surrounding the PTAB, pitting the interests of patent holders who rely on the certainty of their granted rights against the interests of those who see a need for a powerful administrative check on the patent office’s initial work.

Section 2: The Architecture of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board

2.1 Organizational Structure within the USPTO

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board is an adjudicative body established by statute within the administrative framework of the USPTO.6 It is not an independent judicial court but an administrative law body governed by the rules and oversight of the agency.7 Its statutory foundation is laid out in Title 35, Section 6 of the U.S. Code, which defines its membership, duties, and paneling requirements.6

The Board’s personnel includes four statutory members designated by law: the Director of the USPTO, the Deputy Director, the Commissioner for Patents, and the Commissioner for Trademarks.6 The bulk of its adjudicative work, however, is carried out by a large corps of Administrative Patent Judges (APJs). This judicial body is supported by a significant operational infrastructure, including patent attorneys, paralegals, law clerks, and a dedicated Board Operations Division responsible for critical functions like case management, IT systems, hearing coordination, and other administrative support services.6

2.2 Leadership and Judicial Composition

The PTAB is managed by a Chief APJ and a Deputy Chief APJ, who are responsible for the overall administration and operation of the Board.7 Below this top-level leadership, Vice Chief APJs manage distinct divisions, which are further organized into sections based on technology areas, each headed by a Lead APJ.24 This structure is designed to foster specialization, allowing judges to develop deep expertise in specific technical fields such as biotechnology, computer architecture, or mechanical engineering.24

A defining characteristic of the PTAB is the qualification of its judges. APJs are appointed by the Secretary of Commerce and are statutorily required to possess both legal credentials and technical expertise.7 Before their appointment, most APJs have amassed extensive experience in patent law through roles in private practice, as in-house counsel for technology companies, or in other government bodies like the Department of Justice or the International Trade Commission.6 This reservoir of specialized knowledge is a cornerstone of the PTAB’s mission and a key differentiator from the generalist nature of federal district courts.9

2.3 The Dual Functions: Appeals and Trials

The PTAB’s responsibilities are bifurcated into two main functions, which are handled by distinct divisions within the Board:

- Appeals Division: This division carries on the traditional role of the PTAB’s predecessor, the BPAI. It adjudicates ex parte appeals filed by patent applicants whose claims have been rejected by a patent examiner.6 If an examiner issues a final rejection or rejects claims twice, the applicant has the right to appeal that decision to a panel of PTAB judges for review.29 This function represents a very high volume of the Board’s work and involves over 100 APJs organized by technology.7

- Trial Division: This division handles the newer and more contentious adversarial proceedings created by the AIA.7 These proceedings, known as AIA trials, pit a third-party challenger (the petitioner) against a patent owner in a trial-like setting. The primary AIA trials include

Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR).6 Decisions in these cases are typically rendered by a three-judge panel of APJs following briefing, limited discovery, and an oral hearing.16

2.4 The Constitutional Status of APJs and the Advent of Director Review

The structure and authority of the PTAB came under intense constitutional scrutiny, culminating in a landmark Supreme Court decision that reshaped its internal power dynamics. The central legal question was whether APJs, as appointed by the Secretary of Commerce, were “Inferior Officers” or “Principal Officers” under the Constitution’s Appointments Clause.7 Principal Officers must be appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, a more stringent requirement.7

In the 2021 case United States v. Arthrex, Inc., the Supreme Court held that the statutory scheme was unconstitutional.1 The Court reasoned that because APJs could issue final, binding decisions on behalf of the Executive Branch without any review by a superior, presidentially appointed officer, they wielded the power of Principal Officers.7 Their appointment by the Secretary of Commerce was therefore constitutionally deficient.7

Rather than invalidate the entire PTAB system, the Court fashioned a narrow remedy. It severed the statutory provision that insulated APJ decisions from review and held that the Director of the USPTO—a properly appointed Principal Officer—must have the authority to review and, if necessary, overturn any final written decision of the PTAB.1 This ruling gave birth to the “Director Review” process, a new and powerful mechanism of executive oversight within the USPTO.31

The Arthrex decision, while resolving a constitutional dilemma, had the profound effect of altering the PTAB’s character. By vesting final review authority in a political appointee, the Court inadvertently introduced a potential channel for policy considerations to influence what were previously considered purely adjudicative matters. Before Arthrex, the PTAB functioned as a largely independent tribunal whose decisions were appealable only to the federal courts.32 The remedy of Director Review, however, places the ultimate authority in the hands of the USPTO Director, who serves the presidential administration. This creates the possibility that high-level policy goals, such as those concerning pharmaceutical drug prices or competition in the tech sector, could shape the outcome of specific, high-stakes patent challenges through the Director’s intervention.34 This risk was not lost on the Court’s dissenters, who warned that the new structure could make patent rights less free from political influence.34 The Director’s recent and direct role in establishing new rules for discretionary denials of PTAB petitions serves as a clear example of this new dynamic in action, transforming the PTAB from a purely technocratic body into one with an undeniable political dimension.35

Part II: The Mechanics of PTAB Proceedings

Section 3: Ex Parte Appeals: The Traditional Review Function

A substantial portion of the PTAB’s docket is dedicated to its traditional function: hearing ex parte appeals from patent applicants dissatisfied with an examiner’s decision. This process, managed by the Board’s Appeals Division, serves as an internal check on the patent examination process.

An applicant is entitled to file an appeal after a patent examiner has rejected any of the application’s claims twice or has issued a “final” rejection.6 The appeal process is initiated by filing a Notice of Appeal along with the requisite fee within the statutory period for responding to the examiner’s action.30 Following the notice, the applicant must submit a detailed Appeal Brief that lays out the specific arguments against each of the examiner’s rejections.7

Upon receipt of the brief, the patent examiner prepares an Examiner’s Answer, defending the rejections. The applicant then has an opportunity to file a Reply Brief to respond to the examiner’s answer.30 Either party may request an oral hearing to present their case directly to a three-judge panel of APJs.27 After considering the written record and any oral arguments, the panel issues a decision that can affirm the examiner’s rejections, reverse them, or remand the application back to the examiner for further consideration with specific instructions.30 A final decision from the Appeals Division is not the end of the road; the applicant may further appeal the PTAB’s decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) or, as an alternative, file a civil action against the USPTO Director in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.7

Section 4: Inter Partes Review (IPR): The Dominant Trial Proceeding

4.1 Overview and Purpose

Inter Partes Review (IPR) is the cornerstone of the AIA’s trial system and the most frequently utilized post-grant proceeding.12 It was created to provide a focused, streamlined, and cost-effective mechanism for third parties to challenge the validity of issued patent claims on a limited set of grounds.13 It replaced the cumbersome and less effective

inter partes reexamination process that existed before the AIA.10

Any person who is not the owner of a patent may file a petition to institute an IPR.12 However, this right is subject to several important statutory bars. The most significant of these is the one-year time bar under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b): an IPR petition may not be instituted if it is filed more than one year after the date on which the petitioner, its real party in interest, or a privy of the petitioner was served with a complaint alleging infringement of that patent.5 This provision forces an accused infringer to make a swift strategic decision about whether to challenge a patent at the PTAB.

4.2 The IPR Lifecycle: A Step-by-Step Timeline

An IPR proceeding unfolds in two distinct phases, governed by a strict statutory timeline designed to ensure a rapid resolution. The entire process, from petition to final decision, is typically completed within 18 months.13

Phase 1: Pre-Institution (Approximately 6 months)

- Petition Filing: A challenger, known as the Petitioner, initiates the process by filing a comprehensive petition with the PTAB. This document is the foundation of the entire case. It must identify with particularity every patent claim being challenged, the specific grounds for unpatentability for each claim, and provide supporting evidence, which almost always includes a declaration from a technical expert.37 Arguments and evidence not included in the petition are generally considered waived.38

- Patent Owner’s Preliminary Response (POPR): After the petition is filed, the Patent Owner has approximately three months to file an optional POPR.13 The goal of the POPR is to persuade the PTAB panel that the petition fails to meet the standard for institution and that a trial should not be initiated.38 This is a critical strategic juncture for the patent owner, representing their only chance to defeat the IPR before a full trial begins.

- Institution Decision: Within about three months of the POPR filing (or its due date), the three-judge PTAB panel assigned to the case issues an Institution Decision.12 This decision determines whether the petitioner has met the legal standard to proceed to trial. The decision to institute (or not institute) is final and cannot be appealed.10 If the trial is instituted, the PTAB also issues a detailed Scheduling Order that sets firm deadlines for all subsequent events in the proceeding.13

Phase 2: The Trial (12 months post-institution)

- Patent Owner Response and Motion to Amend (MTA): Approximately three months after institution, the Patent Owner files its full Patent Owner Response. This is a detailed rebuttal to the arguments made in the petition, supported by its own evidence and expert declarations.42 The Patent Owner may also file one MTA, proposing to cancel challenged claims and/or substitute them with new, narrower claims designed to overcome the prior art.13

- Discovery: Discovery in IPRs is far more limited than in district court litigation. It routinely includes the cross-examination of each party’s expert declarants via deposition and the mandatory production of documents and evidence cited in filings.13 Additional discovery is rare and granted only when “necessary in the interest of justice”.46

- Petitioner’s Reply: The Petitioner then files a Reply brief, responding directly to the arguments and evidence presented in the Patent Owner Response.42

- Patent Owner’s Sur-Reply: In some cases, the Patent Owner may file a Sur-Reply to address arguments raised in the Petitioner’s Reply.42

- Oral Hearing: Towards the end of the trial period, the parties present their cases live before the three-judge panel in an oral hearing.42

- Final Written Decision (FWD): By law, the PTAB must issue its Final Written Decision within one year of the institution date (a deadline that can be extended by up to six months for good cause).12 The FWD addresses the patentability of every claim for which trial was instituted, resulting in a finding that each claim is either patentable or unpatentable.42

The fast-paced and highly structured nature of an IPR demands meticulous preparation and adherence to strict deadlines from both parties. The following table provides a clear, at-a-glance guide to these critical milestones.

Table 1: Timeline of a Typical IPR Proceeding

| Phase | Timeline (Approximate) | Key Event |

| Pre-Institution | T-6 Months | Petitioner files a detailed petition with supporting evidence. |

| T-3 Months | Patent Owner’s optional Preliminary Response is due. | |

| T=0 | PTAB issues Institution Decision and Scheduling Order. | |

| Post-Institution | T+3 Months | Patent Owner’s full Response and optional Motion to Amend are due. |

| T+6 Months | Petitioner’s Reply to the Patent Owner’s Response is due. | |

| T+7 Months | Patent Owner’s Sur-Reply is due. | |

| T+10 Months | Parties conduct the Oral Hearing before the PTAB panel. | |

| T+12 Months | PTAB issues its Final Written Decision. |

Source: Compiled from 12

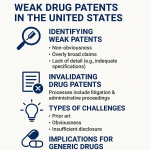

4.3 Grounds for Challenge and Legal Standards

The IPR process is defined by its specific and limited legal framework:

- Grounds for Challenge: IPRs are restricted to challenges based on anticipation (under 35 U.S.C. § 102) and obviousness (under 35 U.S.C. § 103). Furthermore, the evidence used to support these challenges, known as prior art, is limited to patents and printed publications.13 Challenges based on other invalidity theories, such as lack of patentable subject matter or indefiniteness, are not permitted in an IPR.

- Standard for Institution: To convince the PTAB to start a trial, a petitioner must demonstrate in its petition a “reasonable likelihood” that it will prevail in proving at least one of the challenged claims is unpatentable.13

- Burden of Proof for Final Decision: If a trial is instituted, the petitioner carries the burden of proving unpatentability by a “preponderance of the evidence”.13 This standard, which essentially means “more likely than not” (i.e., >50% certainty), is significantly lower and easier for a challenger to meet than the “clear and convincing evidence” standard required to invalidate a patent in district court.21

4.4 IPR Estoppel: The Consequences of a Final Decision

A crucial element of the IPR framework is its powerful estoppel provision, which creates a high-stakes, one-shot opportunity for challengers. If an IPR proceeding concludes with a Final Written Decision, the petitioner, its real parties in interest, and their privies are legally barred (estopped) from later asserting in any other forum—including the USPTO, a district court, or the International Trade Commission (ITC)—that a challenged claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner “raised or reasonably could have raised” during that IPR.13

Because IPRs are limited to grounds based on patents and printed publications, this estoppel provision effectively forces a petitioner to conduct a thorough prior art search and present its best anticipation and obviousness arguments in the IPR petition. Failure to do so, or losing on the merits, means those arguments are likely lost forever. This potent consequence is a key strategic consideration for any party contemplating an IPR.

Section 5: Post-Grant Review (PGR) and Other AIA Proceedings

5.1 The PGR Framework: A Broader, Earlier Challenge

While IPR is the most common AIA trial, Post-Grant Review (PGR) offers a more powerful, albeit time-limited, tool for challenging newly issued patents.51

- Timing: The filing window for a PGR is extremely narrow. A petition must be filed within the first nine months after a patent is granted or reissued.51 This proceeding is only available for patents that fall under the AIA’s first-inventor-to-file regime, meaning those with an effective filing date on or after March 16, 2013.45

- Grounds for Challenge: Unlike the circumscribed grounds of an IPR, a PGR allows a petitioner to challenge a patent on nearly any statutory basis for invalidity.51 This includes not only anticipation (§ 102) and obviousness (§ 103), but also potent challenges related to patentable subject matter (§ 101), written description, enablement, and indefiniteness (§ 112).45 The only significant statutory ground for invalidity that cannot be raised in a PGR is the failure to disclose the “best mode” of practicing the invention.45

- Standard for Institution: Reflecting its broader scope, the PGR has a higher threshold for institution than an IPR. A petitioner must demonstrate that it is “more likely than not” that at least one of the challenged claims is unpatentable. Alternatively, institution can be granted if the petition raises a novel or unsettled legal question that is important to other patents or applications.45

- Estoppel: The estoppel provision for PGR is similar to that for IPR. A petitioner who receives a Final Written Decision is barred from re-litigating in another forum any invalidity ground that was “raised or reasonably could have been raised” during the PGR.45 Given the wide range of grounds available in PGR, this estoppel is significantly broader and carries greater risk for the petitioner.

5.2 A Note on Covered Business Method (CBM) and Derivation Proceedings

The AIA also created two other, more specialized trial proceedings:

- Covered Business Method (CBM) Review: This was a transitional program, similar in scope to a PGR, but specifically designed for challenging the validity of patents related to financial products or services.47 It was a popular tool for challenging software and e-commerce patents on § 101 (abstract idea) grounds. The authority to file new CBM petitions expired on September 16, 2020.8

- Derivation Proceedings: This proceeding replaced the old patent “interference” practice for patents governed by the first-inventor-to-file system. A derivation proceeding is used to determine whether the inventor named in an earlier-filed patent application “derived” the invention from the inventor of a later-filed application, meaning they did not invent it themselves but learned of it from the true inventor.6

The choice between IPR and PGR is a critical strategic decision for any potential challenger, dictated by the age of the target patent and the nature of the available invalidity arguments. The following table highlights the key distinctions.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Post-Grant Proceedings (IPR vs. PGR)

| Feature | Inter Partes Review (IPR) | Post-Grant Review (PGR) |

| Filing Window | After 9 months post-grant (or after a PGR terminates) 47 | 0-9 months post-grant 53 |

| Eligible Patents | All issued patents 47 | Only patents filed under the post-AIA system (on/after March 16, 2013) 54 |

| Grounds for Challenge | Narrow: Anticipation (§ 102) and Obviousness (§ 103) based on patents and printed publications only 13 | Broad: Any statutory ground of invalidity (e.g., §§ 101, 102, 103, 112), except for “best mode” 51 |

| Standard for Institution | “Reasonable likelihood” of success on at least one claim 13 | “More likely than not” that at least one claim is unpatentable, OR a novel/unsettled legal question is raised 47 |

| Estoppel Scope | Petitioner is estopped from raising grounds that were or “reasonably could have been raised” based on patents/publications 13 | Petitioner is estopped from raising grounds that were or “reasonably could have been raised” on any available ground 51 |

Source: Compiled from 13

The AIA’s creation of this dual-track system establishes a critical nine-month “red zone” immediately following a patent’s issuance. During this period, the patent is at its most vulnerable, susceptible to the full arsenal of invalidity challenges available in a PGR, including potent attacks on subject-matter eligibility (§ 101) and written description/enablement (§ 112) that are unavailable in an IPR.51 For a potential challenger, this represents a crucial, time-sensitive opportunity; missing this nine-month window means forfeiting the chance to make these broader arguments and being restricted to the narrower prior-art-based attacks of an IPR.40 Conversely, for a patent owner, successfully navigating this initial nine-month period without a PGR challenge significantly de-risks the patent asset. The relatively low number of PGR filings compared to IPRs suggests that many challengers either miss this window or strategically choose to wait for litigation to commence before filing an IPR, despite its narrower scope.58 This complex dynamic of risk and opportunity is a direct and intended consequence of the AIA’s bifurcated design.

Part III: The PTAB in the Broader Litigation Ecosystem

Section 6: A Tale of Two Forums: PTAB vs. U.S. District Court

The creation of the PTAB established a parallel track for litigating patent validity, forcing patent holders and accused infringers to make critical strategic decisions about the best forum for their dispute. The differences between the PTAB and U.S. district courts are stark, influencing everything from cost and speed to the ultimate likelihood of success.

- Decision-Makers: PTAB trials are adjudicated by a panel of three Administrative Patent Judges who possess deep technical and patent law expertise.9 In contrast, district court cases are typically overseen by a single generalist judge, and the ultimate questions of fact are often decided by a lay jury with no technical background.18 This difference is fundamental; challengers often prefer the expert tribunal, believing APJs are more likely to understand complex prior art arguments, while patent owners may prefer to present their story of invention to a jury.

- Burdens and Presumptions: This is arguably the most significant distinction. In district court, an issued patent is statutorily presumed to be valid. A challenger must overcome this presumption by proving invalidity with “clear and convincing evidence,” the highest standard of proof in U.S. civil law.1 At the PTAB, there is no presumption of validity. The petitioner must prove a claim is unpatentable by a much lower

“preponderance of the evidence” standard.13 This lower hurdle dramatically improves a challenger’s odds of success at the PTAB. - Claim Construction: The standard for interpreting the meaning of patent claims has been a major point of evolution and contention. Historically, the PTAB used the “Broadest Reasonable Interpretation” (BRI) standard, which tended to be broader than the Phillips standard used by district courts, making it easier to find invalidating prior art.7 In a major shift in 2018, the USPTO aligned the PTAB with the courts by adopting the

Phillips standard for AIA trials, with the stated goal of promoting consistency.62 While the standards are now nominally the same, the application by expert APJs can still differ from that of a district court judge, and the preclusive effect of a PTAB construction on a parallel court case remains a complex and evolving area of law.18 - Scope of Issues: The forums differ dramatically in the scope of issues they can address. IPRs are strictly limited to invalidity challenges based on §§ 102 (anticipation) and 103 (obviousness) using only patents and printed publications as prior art.40 District courts, on the other hand, are a full-service venue. They can adjudicate all invalidity theories (including those based on prior public use or sale, patentable subject matter under § 101, and written description/enablement under § 112), as well as patent infringement, monetary damages, injunctions, and equitable defenses like inequitable conduct.22

- Discovery, Cost, and Speed: The procedural differences lead to vast disparities in cost and speed. PTAB proceedings feature tightly limited discovery, typically confined to cross-examining expert declarants.13 District courts permit broad discovery under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a process that can be enormously expensive and time-consuming.46 Consequently, a PTAB trial is significantly cheaper (often costing in the hundreds of thousands of dollars) and faster (concluding in 18 months) than a district court case, which can last for years and cost millions.1

- Standing and Procedural Differences: To file a lawsuit in district court, a party must have Article III standing, meaning it must have suffered a concrete injury.22 The PTAB has no such requirement; any person other than the patent owner can file a petition to challenge a patent.1 This opens the door for challenges by public interest groups or competitors who have not yet been sued. However, a party

must demonstrate Article III standing to appeal an adverse PTAB decision to the Federal Circuit.13 Another key procedural difference is the ability to amend claims; patent owners can file a motion to amend their claims during a PTAB trial, an option that is unavailable in district court.22

The following table provides a comprehensive summary of these critical distinctions, which form the basis of modern patent litigation strategy.

Table 3: PTAB vs. District Court Litigation: A Head-to-Head Comparison

| Attribute | PTAB (IPR/PGR) | U.S. District Court |

| Decision-Maker | Panel of 3 technically expert Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) 9 | Single generalist judge and a lay jury 18 |

| Presumption of Validity | None 21 | Yes, patent is presumed valid 1 |

| Burden of Proof | Preponderance of the Evidence 13 | Clear and Convincing Evidence 19 |

| Claim Construction Standard | Phillips standard (since 2018) 62 | Phillips standard 22 |

| Available Invalidity Grounds | IPR: §§ 102/103 (patents/publications only). PGR: All grounds but best mode 40 | All statutory and equitable grounds for invalidity and unenforceability 46 |

| Other Issues Adjudicated | None (validity only) | Infringement, damages, willfulness, injunctions, equitable defenses 22 |

| Discovery Scope | Very limited; mainly depositions of declarants and cited documents 43 | Broad discovery under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 46 |

| Typical Cost | $350,000 – $700,000+ 1 | $1.5 Million – $5.5 Million+ 1 |

| Typical Time to Final Decision | 18 months from petition filing 13 | 2.5 – 5 years 1 |

| Standing Requirement to Initiate | None (any person other than owner) 1 | Article III standing required (case or controversy) 1 |

| Ability to Amend Claims | Yes, via Motion to Amend 22 | No 22 |

Source: Compiled from 1

Section 7: The Supreme Court and the PTAB: Defining the Boundaries of Power

Since its creation, the PTAB has been the subject of numerous legal challenges that have reached the U.S. Supreme Court. These landmark cases have been instrumental in defining the Board’s authority, procedures, and constitutional standing, fundamentally shaping it into the institution it is today.

- Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee (2016): In its first examination of the PTAB, the Supreme Court delivered two key holdings. First, it affirmed the PTAB’s authority at the time to use the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) standard for claim construction, even though it differed from the standard used in district courts. Second, and more enduringly, the Court ruled that the PTAB’s decision on whether to institute an AIA trial is “final and nonappealable,” insulating this critical gatekeeping function from judicial review.7

- Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC (2018): This case addressed the most fundamental challenge to the PTAB’s existence: whether it was constitutional for an administrative agency, rather than an Article III court, to revoke a patent. The Court upheld the IPR process, reasoning that the grant of a patent is not a private right but a “public right” or “public franchise.” Therefore, Congress was within its constitutional power to authorize an administrative body to reconsider and cancel that grant without violating Article III or the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial. This decision cemented the PTAB’s legal legitimacy.1

- SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu (2018): In a major procedural ruling, the Court held that the AIA requires the PTAB to address every claim a petitioner challenges in its petition. The Board’s prior practice of “partial institution”—instituting trial on only a subset of the challenged claims it found most promising—was deemed unlawful. The ruling mandated an all-or-nothing approach: if an IPR is instituted, the PTAB must issue a final written decision on the patentability of all challenged claims.10

- Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Technologies, LP (2020): Expanding on its Cuozzo precedent, the Court determined that the statutory bar on appealing institution decisions also covers the PTAB’s determination of whether an IPR petition was filed within the one-year time limit after being served with an infringement complaint. This decision further shielded the PTAB’s threshold gatekeeping decisions from judicial oversight.10

- United States v. Arthrex, Inc. (2021): As detailed previously, this case addressed an Appointments Clause challenge to the status of APJs. The Court found their appointment unconstitutional because they wielded the power of Principal Officers. The remedy was to make their decisions subject to review by the USPTO Director, a constitutionally appointed Principal Officer. This decision fundamentally restructured the PTAB by creating the Director Review process and placing the Board’s adjudicative outcomes under the discretionary control of the agency’s political leadership.1

Collectively, these decisions paint a clear picture of the Supreme Court’s approach. The Court has consistently affirmed the core administrative scheme Congress created, deferring to the legislative choice to establish a powerful post-grant review system. At the same time, it has intervened to ensure that this system conforms to constitutional principles of separation of powers and proper executive branch oversight, culminating in the placement of the PTAB firmly under the authority of the USPTO Director.

Table 4: Landmark Supreme Court Decisions Affecting the PTAB

| Case Name | Year | Key Holding | Impact on PTAB |

| Cuozzo v. Lee | 2016 | PTAB’s decision to institute a trial is “final and nonappealable.” Affirmed use of BRI claim construction standard (at the time). | Shielded the PTAB’s critical gatekeeping function from judicial review. Solidified a key procedural difference from district courts. 23 |

| Oil States v. Greene’s Energy | 2018 | Inter partes review is constitutional. Patents are “public rights” subject to administrative revocation. | Cemented the fundamental legitimacy of the PTAB and its authority to invalidate issued patents. 1 |

| SAS Institute v. Iancu | 2018 | If the PTAB institutes a trial, it must issue a final decision on all claims challenged in the petition, not just a subset. | Eliminated the practice of “partial institution,” forcing an all-or-nothing approach to trial and final decisions. 23 |

| Thryv v. Click-To-Call | 2020 | The nonappealable institution decision includes the PTAB’s determination of whether a petition was timely filed. | Broadened the scope of PTAB decisions that are insulated from judicial appeal, reinforcing the finality of its threshold determinations. 23 |

| U.S. v. Arthrex | 2021 | The appointment of APJs was unconstitutional as they acted as Principal Officers. The remedy is to grant the USPTO Director discretion to review PTAB final decisions. | Fundamentally restructured the PTAB by creating the Director Review process, placing the Board under the authority of a political appointee. 7 |

Source: Compiled from 1

Part IV: Controversy, Strategy, and the Future of the PTAB

Section 8: The “Patent Death Squad” Debate: A Critical Analysis

8.1 The Core Criticism: High Invalidation Rates and Perceived Bias

From its earliest days, the PTAB has been shadowed by controversy, encapsulated by the provocative label “patent death squad”—a term first publicly used by former Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit, Randall Rader.10 This criticism is rooted primarily in the Board’s historically high rates of claim cancellation. In the initial years of AIA trials, data showed that once a trial was instituted, the vast majority of challenged patent claims—in some analyses, over 80% or even 90%—were ultimately found unpatentable.67 While rates have fluctuated, more recent statistics continue to show that a high percentage of claims that proceed to a final written decision are invalidated, often in the range of 70-80%.50

Critics seize on these statistics as prima facie evidence of a systemic bias against patent owners. They argue that the PTAB’s structure—particularly its lower “preponderance of the evidence” burden of proof and lack of a validity presumption—is inherently skewed in favor of challengers.73 The narrative advanced by these critics is that the PTAB is invalidating not just “bad” patents, but also legitimate, high-quality patents, thereby creating profound uncertainty in vested property rights. This uncertainty, they contend, chills innovation and discourages the long-term investment necessary for technological breakthroughs, particularly in capital-intensive industries like pharmaceuticals and biotechnology.1

8.2 The Rebuttal: Culling “Bad Patents” and the Self-Selection Effect

Proponents of the PTAB offer a starkly different interpretation of the high invalidation rates. They argue that these figures do not reflect bias, but rather demonstrate that the system is functioning exactly as Congress intended: efficiently identifying and eliminating the large number of low-quality patents that were improperly granted by the USPTO in the first place.1 From this perspective, the PTAB is a vital quality-control mechanism that strengthens the patent system by ensuring that only deserving inventions receive the powerful monopoly of a patent.

Furthermore, defenders of the Board point to a powerful self-selection effect that skews the pool of patents challenged at the PTAB. Filing an IPR petition is a complex and expensive undertaking. Rational economic actors, therefore, will not waste resources challenging strong patents. Instead, they will selectively target patents they are highly confident are vulnerable to invalidation.76 The patents that reach a final written decision at the PTAB are thus not a random sample of all issued patents but are instead the “low-hanging fruit”—those most likely to be invalid from the outset. Proponents also note that the Federal Circuit affirms the vast majority of PTAB decisions on appeal, suggesting that the Board is, by and large, applying the law correctly to the facts before it.50

8.3 Impact on Specific Sectors: Case Studies in Technology and Pharmaceuticals

The debate over the PTAB’s role is not abstract; it has tangible and divergent impacts across different industries.

- Technology: Large technology companies have been among the most frequent and sophisticated users of the PTAB.10 For them, AIA trials are an indispensable tool for defending against infringement lawsuits, particularly from NPEs. The ability to challenge a patent’s validity in a faster, cheaper, and more favorable forum has fundamentally altered the strategic landscape of tech patent litigation. However, critics highlight cases like

Centripetal v. Cisco, where a large company filed numerous IPRs against a smaller innovator’s patents even after a district court had found willful infringement and awarded billions in damages. Such cases are used as evidence that the PTAB can be “weaponized” by large entities to exhaust smaller competitors through parallel, duplicative litigation.74 - Pharmaceuticals: The biopharmaceutical industry has been one of the most vocal critics of the PTAB.10 These companies argue that their business model relies on the certainty of a few key patents that protect blockbuster drugs, which represent billions of dollars in research and development investment. The threat of having these foundational patents invalidated in a PTAB proceeding, they claim, creates unacceptable risk and deters future innovation.73 On the other side of the issue, consumer advocates and generic drug manufacturers view the PTAB as a critical tool for challenging weak “secondary” patents that brand-name companies use to extend their monopolies beyond the life of the core invention. They point to cases involving drugs like Copaxone and rivastigmine, where successful PTAB challenges invalidated patents, enabled earlier generic competition, and led to dramatic reductions in drug prices.79

Ultimately, the “death squad” narrative, while a powerful rhetorical device, obscures a more nuanced reality. The PTAB’s high invalidation rate is a predictable outcome of a system designed with a lower legal standard, staffed by technical experts, and fed by a pool of patents that have been pre-selected by challengers as the weakest targets. The core of the debate is not truly about judicial “bias,” but rather a fundamental policy disagreement over where the balance should be struck between providing certainty for granted patent rights and providing an efficient mechanism to correct the agency’s own errors.

Section 9: Strategic Implications for Patent Holders and Challengers

9.1 The PTAB’s Effect on Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs)

One of the explicit goals of the AIA was to curb perceived abuses by Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs), and the PTAB has proven to be a potent tool in this regard.1 The business model of many PAEs relies on the high cost of district court litigation to extract settlements.3 The PTAB disrupts this model by offering accused infringers a credible, faster, and more cost-effective path to invalidate the asserted patent.2 The mere threat of filing an IPR, with its high probability of success for the challenger, can dramatically decrease the settlement value of a patent held by a PAE and give the defendant significant leverage in negotiations.66

However, the impact has not been confined to PAEs. Critics argue that the very features that make the PTAB effective against “trolls” have been turned against legitimate patent holders, especially individual inventors and small startups. These smaller entities often lack the financial resources to withstand a protracted and expensive IPR battle initiated by a large, well-funded corporate competitor, regardless of the merits of their invention.73 Thus, what was intended as a shield against PAEs is sometimes perceived as a sword used by large incumbents against innovative upstarts.

9.2 Integrating PTAB Strategy with Parallel Litigation

In the post-AIA world, patent litigation is rarely a single-forum affair. For a company sued for patent infringement in district court or the ITC, the decision of whether and when to file a parallel PTAB petition is one of the first and most critical strategic questions.17

- Staying Litigation: A primary objective for a defendant who files an IPR is to convince the district court to grant a stay, pausing the more expensive and time-consuming court proceedings pending the outcome of the PTAB trial.13 A stay conserves resources and allows the validity issue to be decided first in the more favorable PTAB forum.

- Crafting a Consistent Narrative: With the harmonization of the claim construction standard, it is imperative for parties to maintain a consistent legal and technical story across both forums.82 Taking contradictory positions on the meaning of a claim term before the PTAB and a district court is a recipe for losing credibility with both tribunals.83

- Exploiting Asymmetries: The dual-forum system creates opportunities to exploit strategic asymmetries. A challenger can use the PTAB to get an early, favorable claim construction that may influence the district court’s later ruling.66 The significant cost differential can also be used as leverage; a well-funded party can use the threat of a parallel PTAB proceeding to pressure a less-resourced opponent into a more favorable settlement.66

9.3 The PTAB’s Influence on Patent Valuation and Investment Certainty

The existence of a robust and efficient administrative pathway for patent invalidation has inevitably impacted the perceived value and certainty of U.S. patents.1 A patent’s value is derived from its owner’s ability to exclude others, a right that depends on the patent’s strength and enforceability. By creating a lower-cost, higher-success-rate venue for invalidation, the PTAB has introduced a new layer of risk into the valuation equation.73

This increased uncertainty can have a chilling effect on investment, particularly for early-stage companies in the technology and life sciences sectors, whose entire enterprise value may be tied to a small number of core patents.75 Venture capitalists and other investors must now factor the risk of a PTAB challenge into their due diligence and valuation models, which can make it more difficult for patent-reliant startups to secure funding.75 While proponents argue that the PTAB ultimately enhances certainty by weeding out weak patents more quickly 11, the prevailing view among many patent-centric stakeholders is that the Board has made patent rights a less predictable and therefore less valuable asset class.

Section 10: The Evolving Landscape: Recent Trends and Future Outlook

10.1 Analysis of Recent PTAB Statistics (FY 2024-2025)

Recent data from the PTAB reveals a dynamic and shifting landscape, particularly in the wake of new procedural rules.

- Institution Rates: The most dramatic recent trend is a sharp decline in the overall institution rate. Data from April 2025 showed the rate plunging to below 45%, a significant drop from the 68% rate observed in the first six months of the fiscal year.85 This trend is most pronounced in the Electrical/Computer and Mechanical/Business Method technology centers, where institution rates have fallen to 38% and 33%, respectively. In contrast, the rate for Bio/Pharma patents remains high.85 This divergence strongly suggests that the USPTO’s new discretionary denial policies are having a substantial and immediate impact, making it significantly harder for many petitioners to get a trial instituted.

- Invalidation Rates (Final Written Decisions): While the door to the PTAB may be narrowing, the outcomes for those who get inside remain largely the same. Data from late 2024 and early 2025 indicates that once a trial is instituted, the rate of claim cancellation in Final Written Decisions remains very high, hovering around 77-80%.72 The overall all-claims invalidation rate (where every challenged claim is cancelled) for FY2024 was 70%, with a slight decrease to 64% in early FY2025.50

- Motions to Amend (MTA): The ability for a patent owner to amend claims to save them from invalidation remains a difficult path. The grant rate for MTAs continues to be low, in the range of 15-20%.50 This low success rate is a significant contributor to the high all-claims invalidation rate; if a patent owner cannot successfully amend their claims to distinguish them from the prior art, the original claims are often cancelled in their entirety.

Table 5: Recent PTAB Institution and Final Written Decision Statistics (FY 2024-2025)

| Metric | Time Period | Value/Rate | Trend/Commentary |

| Overall Institution Rate | April 2025 | 44% | Significant decrease from 68% in prior 6 months.85 |

| Institution Rate (Bio/Pharma) | April 2025 | 100% (8 of 8) | Remains very high, largely unaffected by new denial policies.85 |

| Institution Rate (Elec./Comp.) | April 2025 | 38% | Substantial decrease, showing impact of discretionary denials.85 |

| Claim Cancellation Rate (in FWDs) | Dec 2024 – Jan 2025 | ~78-80% | Remains consistently high for instituted trials.72 |

| All-Claims Invalidation Rate (in FWDs) | FY2024 / Early FY2025 | 70% / 64% | Consistently high, though showing a slight recent dip.50 |

| Motion to Amend Grant Rate | Cumulative to Jan 2025 | ~16% | Remains very low, contributing to high all-claims invalidation rate.50 |

Source: Compiled from 50

10.2 The New Era of Discretionary Denials: Fintiv and the 2025 Bifurcated Review

The most significant development in recent PTAB practice is the dramatic shift in the handling of discretionary denials. In early 2025, the USPTO rescinded prior guidance that had limited the PTAB’s ability to deny petitions based on parallel district court litigation. This move reinstated the full authority of the framework established in the Board’s precedential Apple Inc. v. Fintiv decision.86 The

Fintiv factors direct the Board to consider issues like the proximity of a court’s trial date, the investment already made in the court case, and the overlap of issues when deciding whether to conserve resources and defer to the district court.87

More radically, the USPTO then introduced a new, bifurcated institution process.35 Under this interim procedure, before a petition is even considered on its substantive merits, the USPTO Director, in consultation with a panel of APJs, first decides whether to deny the petition on discretionary grounds.35 This new discretionary review incorporates the

Fintiv factors but also introduces several new considerations, including:

- The “settled expectations” of the patent owner, which may weigh against institution if a patent has been in force for many years.36

- The workload and resource constraints of the PTAB itself.35

- Compelling economic, public health, or national security interests.36

This new framework represents a monumental shift. It creates a significant new procedural hurdle for petitioners, who must now survive a discretionary review before their arguments are even heard on the merits. It is widely expected to lead to a substantial increase in discretionary denials, making the PTAB a much more difficult forum for challengers to access.85

10.3 The Growing Role of Director Review

The Arthrex decision and the subsequent creation of the Director Review process have empowered the USPTO Director to an unprecedented degree. The Director is no longer just the administrative head of the agency but is now the final arbiter of PTAB decisions, able to intervene to ensure consistency, correct perceived errors, and implement the policy objectives of the current administration.31 The new discretionary denial framework is the most prominent example of the Director wielding this authority to directly shape the day-to-day operation and strategic direction of the PTAB.

10.4 Conclusions and Future Outlook

The PTAB is in a state of significant flux. The strategic calculus for both patent challengers and owners has been upended by the new discretionary denial regime.

For petitioners, the path to a PTAB trial has become more perilous. Filing a petition early in a dispute, before significant progress has been made in a parallel court case, is now more critical than ever to avoid a Fintiv denial. Petitions must now be drafted with an eye toward not only the technical merits but also the discretionary factors, making a compelling case for why the Board should expend its resources on the challenge.

For patent owners, the new rules offer a powerful defensive tool. The first and perhaps strongest line of defense against an IPR is no longer a rebuttal on the merits but a request for discretionary denial based on the age of the patent or the status of parallel litigation.

Looking forward, the PTAB appears to be entering a new phase of its existence. Its role is evolving from that of a forum focused primarily on merits-based adjudication to one characterized by significant discretionary gatekeeping, managed directly by the USPTO’s leadership. This trend suggests a rebalancing of the patent system, potentially shifting power back toward patent owners by making validity challenges harder to bring. However, it also introduces a new layer of unpredictability, as access to the PTAB may now depend less on the strength of a case and more on the shifting procedural rules and policy priorities of the USPTO Director. The fundamental tension that defined the PTAB’s first decade—the conflict between its role as an efficient check on patent quality and its perception as a source of uncertainty for patent rights—is not only unresolved but is now being played out at the highest levels of the agency.

Works cited

- The Patent Trial and Appeal Board and Inter Partes Review – Congress.gov, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48016

- The Case for the Patent Trial and Appeal Board That Congress Envisioned, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/2025-spring/case-patent-trial-appeal-board-congress-envisioned/

- Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs) and Their Impact on Antitrust Laws – PatentPC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-assertion-entities-paes-and-their-impact-on-antitrust-laws

- www.congress.gov, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48016#:~:text=PTAB%20is%20a%20tribunal%20within,patents%20previously%20granted%20by%20USPTO.

- The USPTO Acting Director Uses “Settled Expectations” to Violate the Rule of Law, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentprogress.org/2025/06/the-uspto-acting-director-uses-settled-expectations-to-violate-the-rule-of-law/

- About PTAB | USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/about-ptab

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_Trial_and_Appeal_Board

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) – Practical Law, accessed August 4, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/0-508-3165?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- Advantages of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board | Services & Industries – Ropes & Gray LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ropesgray.com/en/services/practices/advantages-of-the-patent-trial-and-appeal-board

- Inter partes review – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inter_partes_review

- Understanding the Role of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) in Intellectual Property Protection – Patentskart, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentskart.com/role-of-ptab-in-ip-protection/

- What is an inter partes review (IPR)? | Winston & Strawn Law Glossary, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/inter-partes-review

- Inter Partes Review (IPR) – Publications – Morgan Lewis, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2021/04/inter-partes-review-ipr-2020

- Understanding PTAB Trials: Key Milestones in IPR, PGR, and CBM Proceedings – Amster Rothstein & Ebenstein, LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://arelaw.com/images/file/Practical%20Law/20190321_Understanding_PTAB_Trials_Key_Milestones_in_IPR_PGR_and_CBM_Proceedings__3-578-8846_.pdf

- Three Reasons PTAB Litigation Costs More than We Thought – Robins Kaplan, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.robinskaplan.com/newsroom/insights/three-reasons-ptab-litigation-costs-more-than-we-thought

- Practice Area: Patent Trial and Appeal Board – FisherBroyles, accessed August 4, 2025, https://fisherbroyles.com/areas-of-practice/patent-trial-and-appeal-board/

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) – Latham & Watkins LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.lw.com/en/weve-got-washington-covered/patent-trial-appeal-board

- Expert Discovery Protections: Comparing District Courts with the PTAB – Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, accessed August 4, 2025, https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1281&context=ckjip

- Presumptions And Burdens – Klarquist Patent Defenses, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patentdefenses.com/presumptions-and-burdens/

- Proving A Patent Invalid: The Burden is on the Challenger – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2017/11/18/proving-patent-invalid/id=89780/

- The Impact of Prosecution Length on Invalidity Outcomes in Patent Litigation – Baker Botts, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.bakerbotts.com/thought-leadership/publications/2025/march/impact-of-prosecution-length-on-invalidity-outcomes-in-patent-litigation

- 5 Distinctions Between IPRs and District Court Patent Litigation …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/5-distinctions-between-iprs-and-district-court-patent-litigation.html

- The Supreme Court PTAB Cases That Came Before Arthrex | Sterne …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/news/supreme-court-ptab-cases-came-arthrex/

- Organizational Structure and Administration of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Organizational%20Structure%20of%20the%20Board%20May%2012%202015.pdf

- Organizational offices – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/organizational-offices

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/organizational-offices/patent-trial-and-appeal-board

- United States Patent and Trademark Office Patent Trial and Appeal Board Hearings Guide – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/PTAB%20Hearings%20Guide.pdf

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_Trial_and_Appeal_Board#:~:text=The%20PTAB%20is%20primarily%20made,sections%20adjudicating%20different%20technology%20areas.

- New to PTAB? – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/new-to-ptab

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) FAQs – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/faqs

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab

- The Supreme Court continues to reshape patent law – State Bar of Michigan, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.michbar.org/journal/Details/The-Supreme-Court-continues-to-reshape-patent-law?ArticleID=5009

- 2024 PTAB Year in Review: Analysis & Trends – Sterne Kessler, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/2024-ptab-year-in-review-analysis-trends/

- Unconstitutional Appointment of Patent Death Squad -, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.gwlr.org/unconstitutional-appointment-of-patent-death-squad/

- USPTO Procedure Adds New Hurdle to PTAB Trial Institution | Alerts and Articles | Insights, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ballardspahr.com/insights/alerts-and-articles/2025/03/uspto-procedure-adds-new-hurdle-to-ptab-trial-institution

- What to Know About the PTAB’s Discretionary Denial Shakeups – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/what-to-know-about-the-ptabs-discretionary-denial-shakeups/

- PTAB Basics: Key Features of Trials Before the USPTO | Articles …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/ptab-basics-key-features-of-trials-before-the-uspto.html

- Patent Basics: Practice Tips for Achieving Success in Inter Partes Reviews, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2023/10/25/patent-basics-practice-tips-achieving-success-inter-partes-reviews/id=168632/

- IPRs and PGRs – What Patent Owners Need to Know, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.panitchlaw.com/app/uploads/2022/01/IPR-PGR-PTAB-Guide-Patent-Owner-Version-TECH-COVER1987778.1.pdf

- Post-Grant Proceedings | Perkins Coie, accessed August 4, 2025, https://perkinscoie.com/services/post-grant-proceedings

- Post-Grant Patent Proceedings – Marshall, Gerstein & Borun LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.marshallip.com/post-grant-patent-proceedings/post-grant-proceedings/

- Untitled – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Boardside%20Chat%20AIA%20Trials%2011.20.19.pdf

- Inter Partes Review (IPR) – Maier & Maier – Patent Attorneys, accessed August 4, 2025, https://maierandmaier.com/practice-areas/post-grant-practice/inter-partes-review-ipr/

- Federal Circuit Standards of Review for Decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipo.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/CAFC_Rev_of_PTAB.pdf

- BSKB Post Grant Proceedings, accessed August 4, 2025, https://postgrantproceedings.com/patent_modification/post-grant-review/

- District Court or the PTO: Choosing Where to Litigate Patent …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/district-court-or-the-pto-choosing-where-to-litigate-patent.html

- Inter Partes Disputes – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/laws/america-invents-act-aia/inter-partes-disputes

- Trial Phase – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/What%20are%20AIA%20trials%20for%20website%2010.24.19.pdf

- 37 CFR Part 42 — Trial Practice Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board – eCFR, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-37/chapter-I/subchapter-A/part-42

- Perspectives on the PTAB’s 70% All Claims Invalidation Rate – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/07/02/perspectives-ptabs-70-claims-invalidation-rate/id=189971/

- To Do List: Filing a PGR | Finnegan | Leading IP+ Law Firm, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/at-the-ptab-blog/to-do-list-filing-a-pgr-2.html

- How IPR Estoppel Ruling May Clash With PTAB Landscape | Troutman Pepper Locke, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.troutman.com/insights/how-ipr-estoppel-ruling-may-clash-with-ptab-landscape.html

- What is Post-Grant Review? | Winston & Strawn Legal Glossary, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/post-grant-review

- Post-Grant Review – Maier & Maier – Patent Attorneys, accessed August 4, 2025, https://maierandmaier.com/practice-areas/post-grant-practice/post-grant-review/

- USPTO Post-Grant Proceedings: An Overview – Fox Rothschild LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.foxrothschild.com/publications/uspto-post-grant-proceedings-an-overview

- Major Differences between IPR, PGR, and CBM – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/ip/boards/bpai/aia_trial_comparison_chart.pptx

- PGR vs. IPR: Key Differences and Considerations for Patent Challenges, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patexia.com/feed/pgr-vs-ipr-key-differences-and-considerations-for-patent-challenges-20230910

- PTAB Filings Drop Alongside Declining Patent Litigation – Sterne Kessler, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/news/ptab-filings-drop-alongside-declining-patent-litigation/

- Pros and Cons: PTAB vs. District Courts – Patexia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://patexia.com/ptab_court.html

- Patent Invalidity – How Strong Are Your Patent Rights? – Sierra IP Law, PC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://sierraiplaw.com/patent-invalidity/

- WilmerHale – Claim Constructions In PTAB Vs. District Court, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.wilmerhale.com/-/media/files/shared_content/editorial/publications/documents/reprint-law360-claim-constructions-in-ptab-vs-distct-2014-oyloe-dowd-cavanaugh.pdf

- The Impact of Prior Claim Constructions Since the PTAB Adopted the Same Claim Construction Standard as Other Courts – Perkins Coie, accessed August 4, 2025, https://perkinscoie.com/sites/default/files/2025-02/2021_IPR_Impact_of_Prior_Claim_Whitepaper_v5.pdf

- PTAB issues claim construction final rule – USPTO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/procedures/ptab-issues-claim-construction

- PTAB Claim Construction May Be Binding In Later Litigation, PTAB Litigation Blog | Insights, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2024/09/ptab-claim-construction-may-be-binding-in-later-litigation

- PTAB’s Claim Construction Not Binding on District Court Despite Affirmance by Federal Circuit of PTAB’s Unpatentability Determination – Akin Gump, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.akingump.com/en/insights/blogs/ip-newsflash/ptabs-claim-construction-not-binding-on-district-court-despite-affirmance-by-federal-circuit-of-ptabs-unpatentability-determination

- Benefits Of Parallel District Court Litigation and Patent Office Review, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.retailpatentlitigation.com/2014/06/benefits-of-parallel-district-court-litigation-and-patent-office-review/

- The Patent Death Squad – Facts Speak Loudly – US Inventor, accessed August 4, 2025, https://usinventor.org/the-patent-death-squad-facts-speak-loudly/

- For PDF Hot Topics in IP: Navigating the PTAB, accessed August 4, 2025, https://michelsonip.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/For-PDF-Hot-Topics-in-IP_-Navigating-the-PTAB.pdf

- observations on Inter Partes reviews and district Court litigation Settlements – WilmerHale, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.wilmerhale.com/-/media/files/shared_content/editorial/publications/documents/2015-01-ip-today-observations-ipr-district-court-litigation-settlements.pdf

- Patents Supreme Court Cases, accessed August 4, 2025, https://supreme.justia.com/cases-by-topic/patents/

- PTAB Death Squads: Are All Commercially Viable Patents Invalid? – IPWatchdog.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2014/03/24/ptab-death-squads-are-all-commercially-viable-patents-invalid/id=48642/

- PTAB Statistics for Final Written Decisions Issued in December 2024 …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/blogs/at-the-ptab-blog/ptab-statistics-for-final-written-decisions-issued-in-december-2024-and-january-2025.html

- The PTAB Case – DebateUS, accessed August 4, 2025, https://debateus.org/the-ptab-case/

- BIG TECH ABUSES THE PATENT TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD – Congress.gov, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/118/meeting/house/115813/documents/HHRG-118-JU03-20230427-SD002.pdf

- How the Patent Trial and Appeal Board Disproportionately Harms Practicing Small Entities, accessed August 4, 2025, https://usinventor.org/how-the-patent-trial-and-appeal-board-disproportionately-harms-practicing-small-entities/

- Inter Partes Review Initial Filings of Paramount Importance: What Is Clear After Two Years of Inter Partes Review Under the AIA | Mintz, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2014-10-21-inter-partes-review-initial-filings-paramount-importance-what

- Death to All Patents? Really? Why Inter Partes Review Shouldn’t Be Controversial, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2015/11/06/death-to-all-patents-inter-partes-review/id=62935/

- POST-GRANT ADJUDICATION OF DRUG PATENTS: AGENCY AND/OR COURT? – Berkeley Technology Law Journal, accessed August 4, 2025, https://btlj.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/0003-37-1-Rai.pdf

- Policy Brief: How the Supreme Court Patent Case Could Raise Drug Prices – I-MAK, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Policy-Brief_SCOTUS-Patent-Case_-FINAL-TO-PDF.pdf

- Case Studies Confirm: Drug Prices Fall When Patent Challenges Succeed, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.piplius.org/news/case-studies-confirm-drug-prices-fall-when-patent-challenges-succeed

- Mastering PTAB and Patent Litigation: A Complete Guide to Winning Your Case, accessed August 4, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/ptab-and-patent-litigation

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board Proceedings – Sidley Austin LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.sidley.com/en/services/intellectual-property-litigation/patent-trial-and-appeal-board-proceedings

- Strategic Implications of Recent Changes in PTAB Proceedings – Latham & Watkins LLP, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.lw.com/en/insights/2019/09/strategic-implications-of-recent-changes-in-PTAB-proceedings

- Purported Plan to Charge Patent Owners a Percentage of Patent Value is Fraught with Peril, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/07/28/purported-plan-charge-patent-owners-percentage-patent-value-fraught-peril/id=190705/

- April 2025 Institution Rate Slips Below 45 Percent – PTAB Litigation Blog, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ptablitigationblog.com/april-2025-institution-rate-slips-below-45-percent/

- PTAB Unveils Updated Practices for Proceedings – Polsinelli, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.polsinelli.com/publications/ptab-unveils-updated-practices-for-proceedings

- Impact of New USPTO Interim Procedures on Discretionary Denial of AIA Proceedings | Thought Leadership | Baker Botts, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.bakerbotts.com/thought-leadership/publications/2025/may/impact-of-new-uspto-interim-procedures-on-discretionary-denial-of-aia-proceedings

- The PTAB Radically Changes its Approach to Discretionary Denials, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.oblon.com/the-ptab-radically-changes-its-approach-to-discretionary-denials

- Examining New Guidance from the USPTO on Discretionary Denials in AIA Post-Grant Proceedings | Insights | Mayer Brown, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/insights/publications/2025/04/examining-new-guidance-from-the-uspto-on-discretionary-denials-in-aia-post-grant-proceedings

- Discretionary Denials at the PTAB: Strategic Insights for Petitioners and Patent Owners in a Shifting Landscape | Thought Leadership | Baker Botts, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.bakerbotts.com/thought-leadership/publications/2025/july/discretionary-denials-at-the-ptab

- Settled Expectations: How the PTAB’s New Discretionary Denial Framework Is Reshaping IPR Strategy | Haug Partners LLP – JD Supra, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/settled-expectations-how-the-ptab-s-new-3101225/