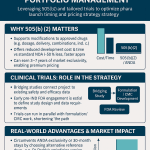

The Strategic Arbitrage of Innovation: A Definitive Legal, Commercial, and Regulatory Review of the 505(b)(2) Pathway

Executive Summary

In the modern pharmaceutical landscape, the binary distinction between “innovator” and “generic” has fractured. For decades, the industry operated on a simple cadence: spend billions on a New Chemical Entity (NCE), enjoy a monopoly, and then yield the market to commodity generics. Today, however, that model is under siege. The “patent cliff” is no longer a singular event but a continuous erosion of value. R&D returns are compressing, and the cost of bringing a novel drug to market has ballooned to an estimated $2.6 billion.1 Enter the 505(b)(2) pathway—a regulatory mechanism that has evolved from an obscure provision of the Hatch-Waxman Act into the primary engine of lifecycle management and specialty pharmaceutical strategy in the United States.

This report serves as an exhaustive operational dossier on the 505(b)(2) New Drug Application (NDA). It is written for the skeptic—the investor who has seen “de-risked” assets fail in Phase III, the General Counsel navigating the treacherous waters of induced infringement, and the commercial strategist fighting for formulary access against vertically integrated Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs).

Our analysis suggests that while the 505(b)(2) pathway offers a compelling arbitrage opportunity—leveraging existing safety data to slash development costs by over 90% 2—it creates a paradox of risk. The clinical risk is indeed lower, but the commercial and legal risks are exponentially higher than in traditional drug development. The recent collapse of “skinny labeling” defenses in federal courts, combined with the “small molecule penalty” embedded in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), suggests that the “golden era” of simple reformulations is ending. The future belongs to complex hybrids, drug-device combinations, and assets that can withstand the dual pressures of price negotiation and patent litigation.

We will dissect the successes of franchises like Treanda and the catastrophic failures of assets like Yosprala and Linhaliq, proving that in the 505(b)(2) world, regulatory approval is merely the starting line, not the victory lap.

Part I: The Regulatory Architecture of Hybrid Innovation

What is the Scientific and Legal “Bridge”?

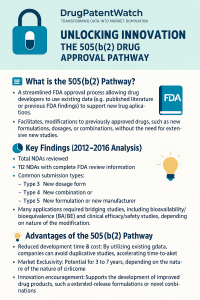

At its core, the 505(b)(2) pathway is a creature of efficiency, designed to prevent the ethical and financial waste of repeating clinical trials for known substances. However, definitions often fail to capture the operational complexity of the pathway. It is not simply a “super-generic” route; it is a full NDA that permits the applicant to rely on data they do not own and have no right to reference.3

The central concept governing this pathway is the “Bridge.” This is the scientific link that justifies relying on the FDA’s prior finding of safety for a Reference Listed Drug (RLD) or on published literature. The bridge is not a metaphor; it is a data set.

- The Bridge as a Firewall: The FDA requires the sponsor to establish a bridge—typically through comparative bioavailability (BA) or bioequivalence (BE) studies—to demonstrate that the proposed product behaves sufficiently like the RLD to render the RLD’s safety data relevant. If the bridge is solid, the sponsor can “borrow” the toxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductive safety data of the RLD, skipping years of preclinical work.3

- The Bridge as a Trap: If the new formulation alters the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile too drastically—for example, if a new extended-release mechanism creates a “dose dumping” effect or significantly higher peak plasma concentrations (Cmax)—the bridge collapses. The FDA may then demand new toxicology studies to assess the safety of these higher exposures, eroding the cost and time advantages of the pathway.3

Industry Insight

“The 505(b)(2) pathway has become increasingly popular, with 60% of all approved NDAs in recent years being 505(b)(2) applications… allows the applicant to rely, at least in part, on investigations that were not conducted by or for them and for which they do not have a right of reference.”

— DrugPatentWatch 5

How Does the 505(b)(2) Differ from 505(b)(1) and 505(j)?

To navigate the regulatory landscape, one must understand the precise triangulation between the three primary approval pathways. The 505(b)(2) sits in the “uncanny valley” between true innovation and commodity replication.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of FDA Approval Pathways

| Feature | 505(b)(1) Stand-Alone NDA | 505(b)(2) Hybrid NDA | 505(j) ANDA (Generic) |

| Primary Candidate | New Chemical Entities (NCEs), novel biologics (via BLA). | Reformulations, new indications, Rx-to-OTC, new combos. | Exact copies of approved drugs. |

| Data Ownership | Sponsor owns 100% of data. | Relies on RLD findings + new “bridging” data. | Relies 100% on RLD; proves “sameness.” |

| Clinical Burden | Full Phase I, II, III (Safety & Efficacy). | Phase I (Bridge) + Phase III (sometimes required). | Bioequivalence (BE) studies only. |

| Development Cost | >$1 Billion – $2.6 Billion.1 | $15 Million – $100 Million.6 | $1 Million – $5 Million. |

| Timeline | 10–15 Years. | 3–5 Years.6 | 2–3 Years. |

| Exclusivity | 5 Years (NCE), 7 Years (Orphan). | 3 Years (Hatch-Waxman), 5/7 Years possible. | 180 Days (First-to-File only). |

| Orange Book | Patents listed by sponsor. | Must certify against RLD patents (Para IV). | Must certify against RLD patents (Para IV). |

| Commercial Model | Brand pricing; high sales/marketing spend. | Brand pricing; targeted sales force. | Commodity pricing; volume-driven. |

1

Why Is the “Right of Reference” Critical?

The defining legal characteristic of the 505(b)(2) is the lack of “Right of Reference.” In a 505(b)(1) NDA, the sponsor owns the data or has licensed it (e.g., Big Pharma licensing a molecule from a biotech). In a 505(b)(2), the applicant is effectively appropriating the FDA’s intellectual property—the finding that the active ingredient is safe—without the permission of the innovator.1

This appropriation is the trigger for the patent dance. Because the applicant is using the innovator’s work to shortcut development, the Hatch-Waxman Act mandates a tradeoff: the applicant must challenge the innovator’s patents or wait for them to expire. This dynamic creates the litigation minefield we will explore in Part III.

Part II: The Economic Engine – Development Economics and ROI

Is the “10x ROI” Real? Examining the Cost Structure

The seductive promise of the 505(b)(2) pathway is the potential to achieve pharmaceutical-grade returns with consumer-goods-grade capital investment. By bypassing the discovery and preclinical phases, which account for roughly 30-40% of total NCE development costs, the 505(b)(2) sponsor radically shifts the break-even point.1

Detailed Cost Breakdown by Phase (505(b)(2) vs. NCE)

- Discovery & Preclinical:

- NCE: $200M – $400M. Involves screening thousands of compounds, wet lab failures, and extensive animal toxicology.

- 505(b)(2): $2M – $5M. The molecule is already discovered. Costs are limited to formulation development and perhaps a short-term toxicology bridge if the excipients are novel.8

- Phase I (Safety/PK):

- NCE: $25M – $50M. First-in-human dose escalation, safety, tolerability.

- 505(b)(2): $2M – $5M. Typically a single-dose crossover study in healthy volunteers to prove the PK profile matches expectations (the bridge).9

- Phase II (Proof of Concept):

- NCE: $100M – $200M. The “Valley of Death” where most drugs fail.

- 505(b)(2): $0 – $10M. Often skipped entirely. If the efficacy of the active moiety is known, and the PK bridge is established, the FDA often accepts that efficacy is preserved. This is the single largest source of savings.9

- Phase III (Pivotal Efficacy):

- NCE: $200M – $500M+. Two large, randomized, placebo-controlled trials required.

- 505(b)(2): $10M – $50M. If a Phase III is required (e.g., for a new indication or route of administration), it is usually a single study with a smaller sample size, sometimes using a surrogate endpoint or non-inferiority design.6

The “Hidden” CMC Costs:

While clinical costs are lower, Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) costs can be disproportionately high for 505(b)(2) programs. Sponsors are often taking an insoluble drug and forcing it into a liquid, or putting a volatile drug into a patch. These “formulation gymnastics” lead to stability failures. In fact, 73% of second-cycle review delays for 505(b)(2)s are due to CMC deficiencies, not clinical safety.10 The failure of Linhaliq (discussed in Part IV) was partly driven by product quality and in vitro release method failures, proving that “known drug” does not mean “easy formulation”.11

The “Exclusivity Stack”: How to Build a Monopoly

Investors often mistake 505(b)(2) products for generics with no protection. In reality, a savvy regulatory strategy can stack multiple layers of exclusivity to create a fortress around the asset.

- Three-Year Exclusivity (The Hatch-Waxman Prize): This is the bread and butter of the pathway. It is granted if the application contains reports of “new clinical investigations” (other than bioavailability studies) essential to approval. It blocks the FDA from approving a 505(b)(2) or ANDA for the same change for three years. It does not block a competitor who generates their own data for a different change.5

- Five-Year NCE Exclusivity (The Loophole): Surprisingly, a 505(b)(2) can receive 5-year NCE exclusivity. This occurs if the active moiety has never been approved by the FDA before. Examples include prodrugs, certain esterifications, or new salts that the FDA determines are distinct chemical entities. This is the “holy grail” as it blocks the submission of any generic application for five years.5

- Seven-Year Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): If a developer repurposes an old drug for a rare disease (prevalence <200,000 in the US), they receive 7 years of market exclusivity. This is arguably the strongest protection available, as it blocks all competitors from marketing the same drug for the same disease, regardless of their data. This was the strategy behind Emflaza.13

Part III: The Litigation Minefield – Paragraph IV and Induced Infringement

The “Patent Dance” of Paragraph IV

For the General Counsel and IP strategist, the 505(b)(2) pathway is synonymous with Paragraph IV (P-IV) litigation. Because the applicant relies on the RLD’s safety data, they are statistically and legally tethered to the RLD’s patents listed in the Orange Book.7

The Mechanism of the Challenge:

- Certification: The applicant certifies that the RLD’s patents are invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the new product.

- Notice: The applicant sends a “Notice Letter” to the brand holder, detailing the factual and legal basis for the certification.

- The 45-Day Trigger: The brand holder has 45 days to sue for patent infringement.

- The 30-Month Stay: If the brand sues, the FDA is statutorily barred from approving the 505(b)(2) NDA for 30 months (or until the court rules). This stay is the primary weapon brand companies use to delay competition.14

Strategic Divergence from Generics:

Unlike a 505(j) generic filer, a 505(b)(2) applicant does not receive 180-day exclusivity for being the “first to file.” This fundamentally alters the risk/reward profile. A generic company fights to invalidate the patent to win the 180-day duopoly. A 505(b)(2) company often fights simply to clear the path to market. Consequently, 505(b)(2) litigation is often less about “scorched earth” invalidation and more about “design-around” non-infringement strategies.16

The Collapse of “Skinny Labeling” Defenses

One of the most sophisticated IP strategies—Section viii “Skinny Labeling”—is currently under existential threat due to recent Federal Circuit decisions.

What is Skinny Labeling?

It allows a generic or 505(b)(2) applicant to seek approval for a drug while “carving out” (omitting) specific indications or methods of use that are still protected by patents. For example, if Drug X is off-patent for hypertension but has a patent for heart failure, the applicant labels the drug only for hypertension.17

The Judicial Earthquake:

Two cases have shattered the reliability of this defense: GSK v. Teva and Amarin v. Hikma.

- The GSK v. Teva (Coreg) Precedent:

In a controversial decision, the Federal Circuit found Teva liable for induced infringement despite having a skinny label. The court looked beyond the label to Teva’s press releases and marketing materials, which described the product as “AB-rated” and a “generic equivalent” to the brand. The court reasoned that these communications, combined with the market reality of automatic substitution, “induced” doctors to prescribe the drug for the patented indication.18

- The Implication: The label is no longer a shield. If a 505(b)(2) company markets its product as “equivalent” to the RLD, it may be liable for inducing infringement of patents it explicitly carved out.

- The Amarin v. Hikma (Vascepa) Shockwave (2024):

Hikma launched a generic version of Vascepa with a skinny label carving out the cardiovascular risk reduction indication. Amarin sued. In June 2024, the Federal Circuit reversed a dismissal, ruling that Hikma’s website—which touted the drug as a “generic equivalent”—could plausibly induce infringement. The court signaled that even “standard” generic marketing language can trigger liability if it encourages the off-label (patented) use.20

- Key Insight: For 505(b)(2) developers, this is a crisis. The commercial value often relies on physicians using the drug broadly (including for the RLD’s indications). However, the legal strategy requires strict separation. Commercial and Legal teams must now be in lockstep; a single press release calling the drug an “equivalent” could trigger hundreds of millions in damages.

Leveraging Data Intelligence: The Role of DrugPatentWatch

In this litigious environment, data visibility is the primary defense. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch have become essential for 505(b)(2) RLD selection and timing.1

How Experts Use DrugPatentWatch:

- Beyond the Orange Book: The FDA’s Orange Book lists patents but doesn’t tell you if they are vulnerable. DrugPatentWatch tracks litigation outcomes, showing which patents have been invalidated in other courts or are subject to Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the USPTO.

- Identifying the “Silent” Competitors: A major risk in 505(b)(2) is that another company might be developing the same modification. If they file first and get 3-year exclusivity, you are blocked. DrugPatentWatch helps identify these stealth competitors by tracking global clinical trial registries and early patent filings.1

- Patent Cliff Visualization: Strategists use the platform to visualize the expiration of the entire patent family (substance, formulation, method of use) to find the “white space” where a 505(b)(2) can launch without a P-IV challenge.1

Part IV: Commercial Reality Checks – Case Studies in Success and Failure

The 505(b)(2) pathway is a graveyard of “technically successful” drugs that failed commercially. We analyze the disparate fates of three high-profile assets to understand the determinants of success.

1. The Lifecycle Masterpiece: Treanda to Bendeka (Teva/Eagle)

- The Problem: Teva’s blockbuster chemotherapy Treanda (bendamustine) was approaching a patent cliff. Generics were poised to decimate its market share.

- The Solution: Teva partnered with Eagle Pharmaceuticals to develop Bendeka, a rapid-infusion formulation of bendamustine approved via 505(b)(2). While Treanda required a 30-60 minute infusion, Bendeka could be administered in 10 minutes.22

- The Execution: Teva filed the 505(b)(2) NDA referencing Treanda’s safety data. They secured Orphan Drug Exclusivity. Crucially, they launched Bendeka and aggressively converted the market before generics hit.

- The Outcome: By the time Treanda generics launched, the market had moved. Hospitals preferred Bendeka because the shorter infusion time allowed them to treat more patients per day (increasing chair turnover revenue).

- Lesson: Innovation must align with the provider’s economic incentive. The 505(b)(2) was not just a new drug; it was a productivity tool for infusion centers.1

2. The Reimbursement Disaster: Yosprala (Aralez)

- The Product: A fixed-dose combination of aspirin (antiplatelet) and omeprazole (PPI) designed to prevent aspirin-associated gastric ulcers in cardiac patients.

- The Logic: Clinical adherence to aspirin is poor due to stomach pain. A single pill solves this. The clinical rationale was sound, and the FDA approved it easily.

- The Failure: Payers (PBMs) revolted. They viewed Yosprala as a “convenience pack” of two generic drugs that cost pennies when bought separately. Major PBMs like CVS Caremark and Express Scripts blocked the drug or placed it on exclusion lists, demanding high rebates that destroyed the margin.24

- The Result: Despite securing some coverage later, the launch never recovered. Aralez eventually filed for bankruptcy.

- Lesson: Clinical utility $\neq$ Reimbursement utility. In the US market, “convenience” is rarely a reimbursable value proposition unless it saves the payer money elsewhere. If the components are generic, the “sum of the parts” pricing ceiling is brutal.25

3. The Pricing Scandal: Emflaza (Marathon/PTC)

- The Asset: Deflazacort, a corticosteroid used for decades in Europe but never approved in the US.

- The Strategy: Marathon Pharmaceuticals used the 505(b)(2) pathway to gain US approval for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). They acquired old efficacy data, conducted bridging studies, and secured 7-year Orphan Drug Exclusivity.

- The Controversy: Marathon set the list price at $89,000 per year. The drug was available from UK pharmacies for roughly $1,000.28

- The Fallout: The backlash was immediate and nuclear. Senators Bernie Sanders and Elijah Cummings launched investigations into “abuse” of the orphan drug program. The public outcry forced Marathon to “pause” the launch and eventually sell the asset to PTC Therapeutics.

- Lesson: Reputational risk is a commercial risk. The 505(b)(2) pathway is vulnerable to political scrutiny when it looks like arbitrage without innovation. In the current climate, “price gouging” on repurposed assets invites legislative intervention.29

4. The Regulatory Stumble: Linhaliq (Aradigm)

- The Asset: Inhaled ciprofloxacin for non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFBE).

- The Failure: Aradigm received a Complete Response Letter (CRL). The FDA demanded an additional two-year Phase III trial to prove durability of efficacy and raised extensive CMC concerns regarding product quality and in vitro release methods.11

- Lesson: The “Bridge” is not guaranteed. Just because ciprofloxacin is a known antibiotic does not mean an inhaled version is “de-risked.” The change in route of administration fundamentally altered the safety/efficacy profile, prompting the FDA to treat it almost like an NCE.

Part V: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – An Existential Threat to Small Molecules

The “Small Molecule Penalty”

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 introduced the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, which allows the government to set “Maximum Fair Prices” (MFP) for top-spending drugs. The legislation draws a sharp distinction between small molecules and biologics that disproportionately threatens the 505(b)(2) model.

The Negotiation Timelines:

- Small Molecules: Eligible for negotiation 9 years after approval.

- Biologics: Eligible for negotiation 13 years after approval.31

The 505(b)(2) Trap:

Most 505(b)(2) drugs are small molecules. The critical danger lies in how the “approval date” is calculated. If the 505(b)(2) product is considered to share the same “active moiety” as an older drug, it may not reset the negotiation clock. However, even if it is considered a distinct single-source drug, the 9-year window is dangerously short for a product that often has a slower launch trajectory than a blockbuster.

Impact on Investment:

The “small molecule penalty” has triggered a capital flight. Investors are pivoting toward biologics (13 years protection) or complex gene therapies. Data indicates a drop of nearly 70% in small molecule funding in certain sectors post-IRA.33 For a 505(b)(2) developer, this means raising capital for a small molecule reformulation is now significantly harder than it was five years ago.

The “Orphan” Loophole Limit:

While orphan drugs are exempt from negotiation, the exemption is fragile. It applies only if the drug is approved for only one rare disease. If a 505(b)(2) developer takes an orphan drug and successfully repurposes it for a second indication—a classic lifecycle strategy—the drug loses its IRA exemption and becomes eligible for price controls. This creates a perverse incentive to avoid developing additional indications for rare disease drugs.34

Part VI: Future Frontiers – AI and Complex Generics

AI-Driven Reformulation

The next generation of 505(b)(2) assets is being designed in silico. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are revolutionizing the formulation process.

- Predictive Bridging: AI models can now predict with high accuracy whether a new salt form or excipient combination will achieve bioequivalence to the RLD, reducing the risk of failure in Phase I bridging studies.36

- Stability Optimization: AI algorithms can model degradation pathways, helping developers solve the CMC hurdles that kill 73% of applications (as noted in Part II) before they reach the lab.37

The Rise of “Complex Generics”

As the market for simple oral solids becomes saturated, the 505(b)(2) pathway is shifting toward Complex Generics. These are products that are technically hybrids but function as generics for complex delivery systems like:

- Long-Acting Injectables (LAIs): Reformulating daily pills into monthly injections (e.g., antipsychotics, HIV prep).

- Inhalation Products: Developing new dry powder inhalers (DPIs) that reference old metered-dose inhalers (MDIs).

- Topical/Transdermal: Patches and gels where bioequivalence is difficult to prove via standard 505(j) methods.

These products face high barriers to entry (CMC complexity) and less competition, allowing them to maintain pricing power even without patent exclusivity.37

Part VII: Conclusion & Key Takeaways

The 505(b)(2) pathway is no longer a “secret weapon”; it is a crowded, mature, and highly regulated marketplace. The days of simple “convenience” reformulations like Yosprala are over, killed by PBM consolidation and the demand for demonstrated economic value. The days of “skinny labeling” arbitrage are waning, suffocated by the GSK and Amarin precedents.

However, for the sophisticated developer, the pathway remains the most capital-efficient route to market in the industry. The winners of the next decade will be those who use the pathway not just to “tweak” old drugs, but to solve fundamental delivery challenges—using AI to stabilize the unstable, and using complex manufacturing to build moats that patents alone can no longer provide.

Key Takeaways

- Arbitrage with a Catch: The 505(b)(2) pathway offers a ~90% reduction in development costs ($20M vs $1B+) compared to NCEs, but it trades clinical risk for outsized commercial and legal risk.

- The Label is Not a Shield: Post-GSK v. Teva and Amarin v. Hikma, reliance on “skinny labels” is treacherous. Marketing a 505(b)(2) product as an “equivalent” to the brand while relying on a carve-out is a direct path to induced infringement liability.

- Reimbursement is the New Efficacy: Clinical superiority (e.g., better compliance) does not guarantee payment. Developers must generate Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR) data to prove to PBMs that the “convenience” saves actual dollars.

- The IRA Changes the Calculus: The 9-year negotiation timeline for small molecules discourages investment in repurposing older assets. Smart money is moving toward biologics or products with airtight, single-indication orphan status.

- CMC is the Silent Killer: With 73% of delays caused by manufacturing deficiencies, developers must prioritize formulation stability and impurity controls as highly as clinical data.

- Data is Strategic Defense: Utilizing tools like DrugPatentWatch to map patent cliffs and litigation history is essential to avoid the “silent” 3-year exclusivity blocks from stealth competitors.

FAQ: Navigating the Nuances

Q1: Can a 505(b)(2) product receive an “AB” rating (substitutable generic status) in the Orange Book?

A: Yes, but it is the exception, not the rule. Typically, 505(b)(2) products are designed to be different (e.g., new dosage form, strength), which makes them pharmaceutically inequivalent to the RLD. If they are inequivalent, they cannot be AB-rated. They usually receive a “BX” rating or no rating, meaning pharmacists cannot automatically substitute them. This requires the sponsor to field a sales force to drive prescriptions, fundamentally changing the commercial model from “generic” to “brand”.38

Q2: How does the “30-month stay” in Paragraph IV litigation differ between 505(b)(2) and 505(j)?

A: Mechanistically, they are identical: a suit within 45 days triggers the stay. Strategically, they are worlds apart. A 505(j) generic filer is incentivized to fight to invalidate the patent to win the 180-day exclusivity. A 505(b)(2) filer has no such statutory reward. Therefore, 505(b)(2) litigation often focuses on “designing around” the patent to avoid the suit entirely, or settling for a launch date that clears the patent cliff, rather than “scorched earth” invalidation.14

Q3: Does the IRA’s price negotiation apply to 505(b)(2) drugs that are essentially “new” brands?

A: It depends on the “active moiety.” The IRA targets the active ingredient. If the 505(b)(2) product is deemed to contain the same active moiety as an older selected drug, it may be swept into the price negotiation. However, if the FDA designates it as a distinct single-source drug (e.g., a complex new formulation that is not cross-substitutable), it may have its own 9-year clock. This is a complex, evolving area of CMS guidance.34

Q4: What is the biggest misconception about the “Bridge” in 505(b)(2) submissions?

A: That it is purely a paperwork exercise. Many sponsors believe citing the RLD is enough. The FDA requires a scientifically rigorous demonstration that the reliance is justified. If your new formulation changes the Tmax (time to peak) or Cmax, the FDA may reject the bridge, arguing that the RLD’s safety data is no longer applicable to your product’s profile. This forces the sponsor to conduct new, expensive toxicology studies.3

Q5: Why did Yosprala fail if the clinical logic (aspirin + gastroprotection) was sound?

A: It failed the “Payer Test.” In the US, PBMs control access. They saw Yosprala as a combination of two cheap generics (aspirin and omeprazole) that cost pennies. Even though Yosprala offered convenience and better compliance, the PBMs refused to pay a brand premium for it. They blocked it from formularies, and without coverage, patients refused to pay out-of-pocket. It proved that in the 505(b)(2) space, economic logic trumps clinical logic.24

Works cited

- The Art of the Nudge: Timing Your 505(b)(2) NDA with Precision …, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-art-of-the-nudge-timing-your-505b2-nda-with-precision-using-drug-patent-data/

- 505(b)(1) versus 505(b)(2): They Are Not the Same – Premier Research, accessed November 26, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/505b1-versus-505b2-they-are-not-the-same/

- Optimized 505(b)(1) and 505(b)(2) Clinical Pharmacology Programs to Accelerate Drug Development – Premier Research, accessed November 26, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/optimized-505b1-and-505b2-clinical-pharmacology-programs-to-accelerate-drug-development/

- overview of the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway for new drug applications – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/156350/download

- Leveraging 505(b)(2) to Innovate Beyond Existing Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-505b2-to-innovate-beyond-existing-drug-patents/

- The 505(b)(2) Pathway: Unlocking a Hybrid Strategy for Drug Innovation – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-505b2-drug-patent-approval-process-uses-and-potential-advantages/

- Draft Guidance for Industry: Determining Whether to Submit an ANDA or 505(b)(2) Application – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/108475/download

- 505B2 Drug Approval Requirements, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.pharmacy.umaryland.edu/media/SOP/wwwpharmacyumarylandedu/centers/cersievents/SehgalNotes.pdf

- What Is a 505(b)(1) — And Why It’s Slowing Down Drug Innovation – SyneticX, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.syneticx.com/blog/505b1.html

- 505(b)(2) Approval Times: The Real Scoop | Premier Consulting, accessed November 26, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/505b2-approval-times-the-real-scoop/

- Aradigm Receives Complete Response Letter from the FDA for Linhaliq NDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://firstwordpharma.com/story/4526393

- Potential Market Exclusivity Granted During U.S. Regulatory Approval Process, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.ipdanalytics.com/post/potential-exclusivity-granted-during-us-regulatory-approval-process

- 2024 New Drug Therapy Approvals Annual Report – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/new-drug-therapy-2025-annual-report.pdf

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- FDA Issues Final Hatch-Waxman Regulations – Duane Morris LLP, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.duanemorris.com/alerts/fda_issues_final_hatch-waxman_regulations_1016.html

- Hatch-Waxman Litigation 101: The Orange Book and the Paragraph IV Notice Letter, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/en-us/insights/publications/2020/06/ipt-news-q2-2020/hatch-waxman-litigation-101

- GlaxoSmithKline LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. – Food and Drug Law Institute, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2021/06/glaxosmithkline-llc-v-teva-pharmaceuticals-usa-inc/

- GSK v. Teva: The End of Generic Skinny Labels? | UC Davis Law Review, accessed November 26, 2025, https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/archives/56/online/gsk-v-teva-end-generic-skinny-labels

- GSK v. Teva – Induced Infringement Liability Despite Skinny Label – Cooley, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.cooley.com/news/insight/2020/2020-10-06-gsk-v-teva-induced-infringement-liability-despite-skinny-label

- U.S. Supreme Court Invites Solicitor General to Submit Briefing on “Skinny Labels” | Insights, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2025/06/us-supreme-court-invites-solicitor-general-to-submit-briefing-on-skinny-labels

- AMARIN PHARMA, INC. v. HIKMA PHARMACEUTICALS USA INC. – U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/opinions-orders/23-1169.OPINION.6-25-2024_2339226.pdf

- Navigating the 505(b)(2) Pathway: No Two Drugs Are Alike – Premier Research, accessed November 26, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/navigating-the-505b2-pathway-no-two-drugs-are-alike/

- Case Study: Achieving a 505(b)(2) Regulatory Approval for Multiple NDA-Enabling Studies, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.altasciences.com/resource-center/blog/505b2-submission-approval-case-study

- Aralez Provides Update On PBM Formulary Status For Yosprala – PR Newswire, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/aralez-provides-update-on-pbm-formulary-status-for-yosprala-300387444.html

- YOSPRALA (aspirin and omeprazole) – This label may not be the latest approved by FDA. For current labeling information, please visit https://www.fda.gov/drugsatfda, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/205103s004lbl.pdf

- This presentation includes certain statements that constitute “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of applicable securities laws. Forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, statements regarding the successful execution of our commercialization strategy with respect to Fibricor® and YOSPRALATM, including our plans to continue financially disciplined build up of the Company, the PDUFA goal date for a decision in respect of YOSPRALA, the targeted YOSPRALA launch in 4Q 2016, pending FDA approval, YOSPRALA having the ability to achieve mid-single digit market share in the secondary prevention patient population, our plan to submit YOSPRALA in Europe in 4Q 2016, targeting new drug submissions in Canada in 1H 2017 with respect to each of MT400 (Treximet®) and YOSPRALA, our goal to be profitable on an adjusted EBITDA basis by 2018, opportunistic business development and potential acquisitions that will accelerate profitability, near-term EBITDA, accretive and revenue generating products and business opportunities, and other statements that are not historical facts, and such statements are typically identified by use of terms such as “may,” “will,” – SEC.gov, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1660719/000110465916126254/a16-12998_1ex99d1.htm

- Modeling the Effects of Formulary Exclusions: How Many Patients Could Be Affected by a Specific Exclusion?, accessed November 26, 2025, https://jheor.org/article/94544-modeling-the-effects-of-formulary-exclusions-how-many-patients-could-be-affected-by-a-specific-exclusion

- Marathon presses pause on Emflaza launch after pricing pushback …, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/marathon-deflazacort-sanders-cummings-price-letter/436080/

- Eight senators pile on to Marathon’s Emflaza—and its $89000 pricing blunder, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/eight-senators-pile-to-marathon-s-emflaza-pricing-blunder

- FDA demands 2-year phase 3 from Aradigm in hard-hitting approval rejection, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/fda-demands-2-year-phase-3-from-aradigm-hard-hitting-approval-rejection

- Early impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on small molecule vs biologic post-approval oncology trials – PMC – NIH, accessed November 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12392883/

- The Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on the Economic Lifecycle of a Pharmaceutical Brand – IQVIA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/blogs/2024/09/impact-of-the-inflation-reduction-act

- The Inflation Reduction Act Is Negotiating the United States Out of Drug Innovation | ITIF, accessed November 26, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/02/25/the-inflation-reduction-act-is-negotiating-the-united-states-out-of-drug-innovation/

- FAQs about the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program – KFF, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicare/faqs-about-the-inflation-reduction-acts-medicare-drug-price-negotiation-program/

- The Inflation Reduction Act: The Devil is in the Details for Patients with Rare Diseases, accessed November 26, 2025, https://arci.org/ira-details-for-rare-diseases/

- Artificial Intelligence for Drug Development – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/artificial-intelligence-drug-development

- FDA 505(b)(2) Pathway Drives 69 Drug Reformulations in 2024-2025, Focusing on Stability and Patient Experience – MedPath, accessed November 26, 2025, https://trial.medpath.com/news/2c86f6856832466d/fda-505-b-2-pathway-drives-69-drug-reformulations-in-2024-2025-focusing-on-stability-and-patient-experience

- Return On Investment For 505(b)(2) Products: Is An “AB” Rating Possible?, accessed November 26, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/return-investment-505b2-products-ab-rating-possible/

- 2024 Guide to the IRA and Other Drug Pricing Initiatives: Impact on Life Sciences Investments – Akin Gump, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.akingump.com/a/web/qqPAiuKYm4vBRaAhptAMEs/8Z8Ua4/akin_guide-to-ira-digital-version-final-v2.pdf