Introduction: The High-Stakes World of Pharmaceutical Contracting

In the sprawling, high-stakes ecosystem of pharmaceutical development, Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs) have become the indispensable backbone of innovation. They are the silent partners, the expert hands, the state-of-the-art facilities that transform a brilliant scientific concept into a life-saving reality for millions. From small, venture-backed biotechs with a single promising molecule to Big Pharma giants looking to optimize their supply chains, the industry increasingly relies on the specialized expertise of CDMOs. This reliance, however, places these organizations at a unique and precarious intersection of immense opportunity and profound risk. The currency of this realm isn’t just scientific acumen or manufacturing prowess; it’s intellectual property (IP).

For a CDMO, every project is a deep dive into a client’s most valuable assets: their patented compounds, proprietary formulations, and confidential manufacturing processes. You are entrusted with the crown jewels. This position of trust is a double-edged sword. On one side, it offers a privileged view into the cutting edge of pharmaceutical science, providing unparalleled opportunities to build expertise and grow your business. On the other, it exposes you to a labyrinth of legal and financial risks, where a single misstep can lead to catastrophic infringement litigation, reputational damage, and the loss of key partnerships. How do you navigate this complex terrain? How do you handle the IP of dozens of clients without inadvertently cross-contaminating projects or infringing on a third-party patent you never even knew existed?

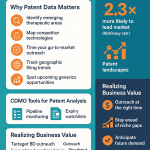

The answer lies in transforming your perspective on intellectual property. Too often, IP is viewed as a purely defensive concern—a legal minefield to be navigated by lawyers, a cost center, a box to be ticked. But this view is dangerously incomplete. For the forward-thinking CDMO, patent data is not just a shield; it is a powerful sword. It is a treasure map that can reveal untapped markets, a crystal ball that can predict future manufacturing needs, and a strategic weapon that can give you a decisive edge in winning new business. This article is your comprehensive guide to mastering this duality. We will move beyond the basics, providing you with the in-depth strategies and actionable insights needed to not only mitigate IP risk but also to proactively leverage patent intelligence for sustainable, strategic growth.

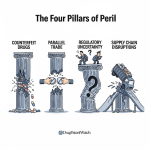

Why CDMOs are at the Epicenter of Pharma Innovation and Risk

The modern pharmaceutical industry model is built on outsourcing. The days when a single company would handle every step of a drug’s journey—from discovery and preclinical research to scaled-up manufacturing and commercial distribution—are largely gone. The economic pressures, the need for specialized technological capabilities (especially in areas like biologics, cell and gene therapies), and the desire for flexibility have fueled the meteoric rise of the CDMO sector. A report by Grand View Research valued the global pharmaceutical CDMO market at USD 178.65 billion in 2023 and projected it to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.2% from 2024 to 2030 [1]. This growth is a testament to the critical role CDMOs play.

You are not just contract manufacturers; you are partners in development. You optimize synthesis routes, develop novel formulations, create analytical methods, and navigate the complex regulatory pathways. This deep involvement means you are often creating your own intellectual property, or at least know-how that is intrinsically linked to your client’s IP. This very integration is what creates the risk. Are the process improvements you developed for Client A, which are now part of your team’s institutional knowledge, patentably distinct from the process you’re about to use for Client B? Could a novel excipient you propose for a formulation infringe on a broad patent held by a company that isn’t even your client? These are not hypothetical questions; they are daily realities for project managers and scientists on the front lines of CDMO operations. The sheer volume and diversity of projects managed by a typical CDMO create a “perfect storm” for IP-related conflicts if not managed with extreme diligence.

The Duality of Patents: Shield and Sword for the Modern CDMO

Let’s reframe the patent document itself. It’s easy to see it as a legalistic, impenetrable text—a warning sign that says “Keep Out.” And in a sense, it is. A patent grants its owner the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the claimed invention for a limited time. For a CDMO, ignoring these exclusion rights is like sailing a ship through a naval minefield with the navigation system turned off. A freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis is your sonar, your radar, your essential tool for detecting and avoiding these explosive legal threats. This is the defensive shield, and it is absolutely non-negotiable.

But that’s only half the story. The very nature of the patent system requires an inventor to disclose their invention to the public in exchange for that limited monopoly. This public disclosure is a goldmine of strategic information. Every patent is a detailed blueprint of a competitor’s technology, a pharma company’s R&D focus, and the direction of the market. For a CDMO, this publicly available data is a powerful offensive weapon.

Imagine being able to predict which types of manufacturing capabilities will be in high demand two years from now. Imagine identifying a small biotech that just received a patent on a complex molecule but likely lacks the internal capacity to scale it up. Imagine being able to walk into a sales meeting with a potential client and not just presenting your standard capabilities, but showing them you’ve analyzed their patent portfolio and have already conceptualized a manufacturing solution tailored to their specific technology. This is the power of using patent data offensively. It allows you to move from being a reactive service provider to a proactive, strategic partner, securing high-value contracts before your competitors even know they exist.

A Roadmap for This Article: From Defensive Plays to Offensive Strategies

This article is structured to build your expertise from the ground up. We will begin by laying the foundational knowledge of the IP landscape specific to CDMOs. We will then dive deep into the defensive game, providing a masterclass in freedom-to-operate analysis, patent deconstruction, and building a proactive monitoring system to keep you out of legal trouble. We’ll illustrate these concepts with cautionary tales and case studies of what can go wrong.

From there, we will pivot to the exciting offensive strategies. You will learn how to read the market tea leaves by analyzing patent expiry data (the “patent cliff”), how to conduct “white space” analysis to discover unmet technological needs, and how to use competitive patent intelligence to sharpen your business development efforts. We will then turn inward, discussing how to build an IP-centric culture within your organization, from the C-suite to the lab bench, and how to fortify your legal agreements.

Finally, we’ll look to the horizon, exploring emerging trends in complex biologics, AI, and global patent law that will shape the future of the CDMO industry. By the end of this journey, you will be equipped with a holistic framework for transforming intellectual property from a source of anxiety and risk into your organization’s most potent engine for growth and competitive advantage.

The Bedrock of CDMO Operations: Understanding the IP Landscape

Before we can devise strategies for managing risk and seizing opportunities, we must first establish a common language and a clear understanding of the intellectual property assets at play. For a CDMO, this landscape is more varied and complex than for a traditional manufacturing company. You operate in a world where intangible assets—patents, trade secrets, and proprietary know-how—are often more valuable than the physical reactors and filling lines. A failure to appreciate the nuances of these assets is the first step toward unintentional infringement or a missed business opportunity.

What is Intellectual Property in the Pharma Context?

While the term “IP” is often used as a catch-all, it encompasses several distinct types of legal protections, each with its own rules, scope, and strategic implications. In the pharmaceutical world, the most critical of these are patents and trade secrets.

H4: Patents: The Core Asset (Composition of Matter, Method of Use, Formulation, Process)

Patents are the undisputed kings of pharmaceutical IP. They provide a powerful, legally enforceable monopoly for a period of, typically, 20 years from the filing date. This exclusivity is what allows drug developers to recoup the massive R&D investments required to bring a new therapy to market. For a CDMO, understanding the different types of patents is crucial, as your work may touch upon any or all of them.

- Composition of Matter Patents: This is the holy grail of pharma patents. It covers the new chemical entity (NCE) or biologic molecule itself—the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API). This is typically the strongest and broadest form of protection. When a client comes to you with a new drug, their core protection is almost always a composition of matter patent on the API. Your primary concern here is ensuring you are not manufacturing a patented molecule without a license from the owner.

- Method of Use Patents: These patents do not cover the drug itself, but rather a specific method of using it to treat a particular disease or condition. For example, a company might discover that an old, off-patent drug is effective for a new indication. They can then patent this new use. While seemingly less of a direct risk for a CDMO, it can become relevant if your work involves developing specific dosage forms or instructions for use that are tied to the patented method.

- Formulation Patents: This is a critically important area for CDMOs. These patents cover the specific recipe of the final drug product—the API plus all the inactive ingredients (excipients), such as binders, fillers, coatings, and stabilizers. They can also cover specific drug delivery systems, like extended-release tablets, transdermal patches, or nanoparticle-based carriers. Since CDMOs are often deeply involved in formulation development, this is a major potential minefield. The formulation you develop for Client A could inadvertently infringe on a broad formulation patent held by Company C.

- Process Patents (or Method of Manufacture Patents): This is perhaps the most dangerous and overlooked patent risk for CDMOs. These patents cover a specific method of making a substance. For example, a patent could claim a novel, more efficient multi-step synthesis for an API, or a specific method for purifying a monoclonal antibody. As a CDMO, your core business is process. The synthesis routes, purification techniques, and manufacturing conditions you use are all potential sources of infringement. A pharma company might have a patent on a specific crystallization method that yields a purer product. If you, independently, develop and use a substantially similar method for a different client, you could be infringing. This is where a robust FTO is not just recommended; it’s essential.

H4: Trade Secrets: The Unseen Competitive Edge

Not all valuable information is patented. A trade secret is any confidential business information which provides an enterprise a competitive edge. This can include manufacturing processes, analytical testing methods, supplier lists, and even specific equipment configurations. The classic example is the formula for Coca-Cola. In the CDMO world, trade secrets are everywhere.

The key difference from patents is that trade secrets are protected only as long as they are kept secret. There is no formal registration process. Their protection comes from internal security measures and legal agreements like Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs). For a CDMO, the primary challenge is twofold:

- Protecting Client Trade Secrets: You have a legal and ethical obligation to safeguard the confidential information your clients entrust to you. This requires robust data security, physical access controls, and strict employee confidentiality agreements. A breach can destroy a client relationship and your reputation.

- Protecting Your Own Trade Secrets: Your organization develops its own proprietary know-how over time. This might be a particularly efficient way to run a certain type of reaction, a unique analytical technique, or a deep understanding of how to work with a difficult-to-handle class of compounds. This “secret sauce” is a valuable asset that differentiates you from competitors. The risk is that this knowledge, held by your employees, could “walk out the door” or be inadvertently disclosed. It’s crucial to identify what your key trade secrets are and take active steps to protect them.

H4: Trademarks and Copyrights: Branding and Documentation

While less central to the core infringement risk, trademarks and copyrights are still relevant. Trademarks protect brand names and logos—think of the brand name of a drug, like Lipitor®. CDMOs typically don’t face direct trademark risk unless they are involved in packaging and branding activities. Copyright protects original works of authorship, such as written documents. In the CDMO context, this could apply to your Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), batch records, or training manuals. It’s important not to plagiarize copyrighted material from other sources when creating your internal documentation.

The Unique IP Challenges Faced by CDMOs

A standalone pharmaceutical company primarily worries about its own IP portfolio and its freedom to operate against competitors. A CDMO’s position is exponentially more complex. You are a nexus point, constantly juggling the IP of multiple, often competing, clients.

H4: The “Agent” Dilemma: Working on Someone Else’s IP

Your fundamental business model is to work as an agent or contractor for your clients. They bring you their IP, and you provide the service of developing or manufacturing it. A critical, and often misunderstood, legal principle here is that of induced infringement. Even if your client has assured you they have the rights to a product, if that product is later found to infringe on a third-party patent, the CDMO can also be held liable. The patent holder can sue not only the client (the direct infringer) but also the CDMO for “contributory infringement” (for supplying a key component) or “induced infringement” (for actively enabling the infringement). Simply saying “my client told me it was okay” is not a valid legal defense. This is why a CDMO must conduct its own independent IP due diligence. You must protect your own business, as you cannot fully delegate that responsibility to your client.

H4: Cross-Contamination of Know-How: The Silent Risk

Imagine this scenario: Your team spends a year working on a challenging project for Biotech A, developing a clever new purification technique for their complex biologic. The project ends. Six months later, a new client, Pharma B, comes to you with a molecule that has a similar purification challenge. Your scientists, drawing on their recent experience, naturally apply the technique they developed for Biotech A’s project. Have you done anything wrong?

The answer is a complicated “it depends.” Did the Master Service Agreement (MSA) with Biotech A specify that all process improvements developed during the project belong exclusively to them? If so, you have just breached your contract and potentially misappropriated their trade secrets or even infringed on a process patent they may have subsequently filed. This “cross-contamination” of confidential information and know-how is one of the most insidious risks CDMOs face. It’s not malicious; it’s the natural result of skilled scientists solving problems. Mitigating this requires a combination of clear contractual terms about ownership of “background” and “foreground” IP, strong internal firewalls between project teams, and continuous training for your staff on their confidentiality obligations.

H4: Navigating Multiple Client Portfolios Simultaneously

A successful CDMO may have dozens of active projects at any given time. Client A may be developing a drug for oncology, while Client B is working on a cardiovascular therapy, and Client C is in the orphan disease space. While their therapeutic goals are different, the underlying technologies might be surprisingly similar. They might both be using a lipid nanoparticle delivery system, or a specific type of controlled-release polymer, or a similar synthetic chemistry pathway.

Your organization is in the unique position of having a bird’s-eye view of these overlapping technologies, but this view comes with a heavy burden. You must have systems in place to ensure that the confidential work you do for Client A does not inform or influence the work you do for Client B, and that neither project infringes on the patents of Company Z, a third party you have no relationship with. This requires sophisticated project management and a robust, centralized approach to IP risk assessment that can analyze projects not in isolation, but as part of a dynamic and interconnected portfolio.

The Defensive Game: Using Patent Data to Mitigate Infringement Risk

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical manufacturing, playing defense is not optional; it’s the foundation upon which your entire business rests. A single patent infringement lawsuit can be devastating, resulting in multi-million dollar damages, injunctions that halt your operations, and irreparable harm to your reputation. The key to a strong defense is not simply reacting to legal threats as they arise but proactively identifying and neutralizing them before they ever materialize. Your most powerful tool in this endeavor is the Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis, fueled by comprehensive patent data. Think of it as preventative medicine for your business.

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Your Non-Negotiable First Step

At its core, an FTO analysis is an investigation to determine whether a specific action, such as manufacturing and selling a product, can be done without infringing on the valid intellectual property rights of others. It is not an analysis of whether your process is patentable; it’s an analysis of whether your process infringes on someone else’s existing patents. For a CDMO, initiating any new project without a clear FTO strategy is an act of corporate malpractice.

H4: What is an FTO and Why is it Critical for CDMOs?

An FTO analysis involves systematically searching and analyzing the patent landscape for any granted or pending patents whose claims could arguably “read on” or cover the product, formulation, or manufacturing process you intend to use. It’s a risk assessment tool. The goal is to identify any “blocking” patents that could prevent you from proceeding.

Why is this so critical for a CDMO?

- Direct Liability: As we’ve discussed, you can be sued directly for patent infringement, even if you are only acting on a client’s instructions. An FTO is your own due diligence to protect your own assets.

- Protecting Your Client (and Your Relationship): Bringing a potential FTO issue to your client’s attention early on is a value-added service. It demonstrates your expertise and diligence. It allows for a collaborative effort to design around the blocking patent, license the technology, or challenge the patent’s validity, long before significant capital has been invested in a potentially infringing process. Uncovering an FTO problem late in the development cycle can destroy a project and the client relationship along with it.

- Informed Decision-Making: The results of an FTO analysis inform critical business decisions. It can influence the project’s timeline, budget, and even its technical direction. If a preferred manufacturing route is blocked, you need to know this at the outset so you can allocate resources to develop an alternative, non-infringing route.

As stated by patent attorney David L. Reamer, “The question an FTO analysis answers is not ‘can we get a patent?’ but rather, ‘can we practice our invention without being sued?’ For a CDMO, this is arguably the more important question to answer on a day-to-day basis.” [2]

H4: The Scope of an FTO: Beyond the API

A common and dangerous mistake is to limit the FTO analysis to the client’s core composition of matter patent for the API. This is a hopelessly narrow view. A thorough FTO for a CDMO project must be a multi-layered investigation covering every aspect of the project. This includes:

- The API Synthesis Route: Every step, reagent, catalyst, and set of reaction conditions must be scrutinized. Are you using a patented method for a key intermediate step? Is the crystallization process you’ve chosen covered by someone’s process patent?

- The Formulation: The combination of excipients is a fertile ground for patents. Your FTO must search for patents claiming specific combinations of polymers, solubilizers, stabilizers, or other inactive ingredients that perform a certain function (e.g., improve bioavailability, create a stable suspension).

- The Drug Delivery System: If the product is anything other than a simple immediate-release tablet, the delivery mechanism needs its own FTO. This includes extended-release technologies, transdermal patches, inhalers, liposomal formulations, and drug-eluting stents.

- Analytical Methods: While less common, it is possible for novel and non-obvious analytical methods to be patented. If you are using a highly specialized method to test for purity or stability, it’s wise to include it in the FTO scope.

- Polymorphs and Salt Forms: The specific crystalline form (polymorph) or salt form of an API can have its own patent protection, separate from the basic composition of matter. Manufacturing the “wrong” polymorph, even unintentionally, can constitute infringement. The FTO must search for patents claiming specific polymorphic forms that might be produced under your planned manufacturing conditions.

H4: The Perils of a Superficial FTO: A Cautionary Tale

Consider the hypothetical case of “CDMO-Pro,” a mid-sized CDMO known for its chemical synthesis capabilities. They take on a project for “BioVenture,” a small biotech with a promising new cancer drug. BioVenture provides a composition of matter patent for their API and assures CDMO-Pro that “the IP is all clear.” CDMO-Pro’s internal team confirms the API patent is valid and proceeds.

They assign their best chemists, who develop a highly efficient, 5-step synthesis route that significantly improves the yield compared to the route used in academic labs. The project is a technical success. They manufacture the clinical trial materials, and the drug shows great promise. BioVenture is thrilled.

A year later, just as they are preparing to scale up for Phase III manufacturing, both BioVenture and CDMO-Pro receive a cease-and-desist letter from a Big Pharma company. It turns out that Step 3 of CDMO-Pro’s “novel” synthesis route—a specific palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction using a particular phosphine ligand—is covered by a broad process patent owned by the pharma giant. This patent didn’t cover the final API, so it wasn’t on BioVenture’s radar. But it covered a crucial intermediate step.

The result is a disaster. Manufacturing is halted. The clinical trial timeline is thrown into chaos. CDMO-Pro and BioVenture are now facing a costly infringement lawsuit. They are forced into a terrible choice: spend millions on litigation, attempt to negotiate an exorbitant license from the Big Pharma company, or go back to the drawing board to develop a completely new, non-infringing synthesis route, setting the project back by 18-24 months. CDMO-Pro’s reputation is damaged, and their relationship with BioVenture is shattered. This entire catastrophe could have been avoided with a proper, comprehensive FTO analysis at the project’s outset that examined not just the final product, but the process of making it.

Deconstructing the Patent: A Practical Guide for CDMOs

To conduct or even intelligently review an FTO, you don’t need to be a patent attorney, but you do need a working knowledge of a patent’s structure and, most importantly, how to interpret its claims. A patent is a legal document, but it’s also a technical one. Learning to read it effectively is a critical skill for any science or business professional in the pharmaceutical industry.

H4: Anatomy of a Patent: Claims, Specification, and Drawings

A typical patent document has several key sections, but for FTO purposes, you need to focus on two: the Specification and the Claims.

- The Specification (or Description): This is the main body of the patent. It’s a detailed written description of the invention, providing enough information that a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (a legal term for a typical practitioner in that technical field) could reproduce it. The specification includes background information, a summary of the invention, and detailed examples (often called “prophetic” if they haven’t actually been performed, or “working” examples if they have). The specification provides the context for interpreting the claims.

- The Claims: This is the most important part of the patent from a legal perspective. The claims are a series of numbered sentences at the end of the patent that define the precise legal boundaries of the invention. They are the “property lines” of the patent. Infringement is determined by comparing your product or process to the language of the claims, and only the claims. The detailed examples in the specification might describe one specific way of doing something, but the claims might be written much more broadly to cover many other ways as well.

H4: Claim Interpretation: The Literal vs. Doctrine of Equivalents

Infringement analysis generally happens in two stages: literal infringement and infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.

- Literal Infringement: This is the most straightforward type of infringement. It occurs if your product or process includes every single element listed in a patent claim. For example, if a claim recites “A pharmaceutical formulation comprising component A, component B, and component C,” and your formulation contains A, B, and C (plus maybe D and E), you have literally infringed that claim. If your formulation only contains A and B, you have not. It’s a very precise matching game.

- The Doctrine of Equivalents: This is where things get much trickier. The Doctrine of Equivalents is a legal rule that prevents an infringer from avoiding liability by making minor, insubstantial changes to a patented invention. Under this doctrine, infringement can be found if an element in your product or process is not literally the same as what is recited in the claim, but performs substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, to achieve substantially the same result. For example, if a process patent claims “heating to 90°C,” and you heat to 89°C to achieve the exact same outcome, a court would likely find that to be an equivalent and therefore infringing. This doctrine introduces a “gray area” around the literal claim language and is a frequent point of contention in litigation. For a CDMO, it means you can’t be too clever in trying to “design around” a patent by making trivial changes.

H4: Reading Between the Lines: What the Patent Doesn’t Say

Equally important to what a patent says is what it doesn’t say. The scope of a patent is defined by its claims. Anything not claimed is, in theory, dedicated to the public. This is the basis of “designing around” a patent. If a process patent claims a synthesis using a palladium catalyst, developing a process that uses a nickel catalyst might be a valid, non-infringing alternative.

Furthermore, you must look at the “file history” or “prosecution history” of the patent. This is the public record of the back-and-forth between the inventor and the patent office. Often, an inventor will start with very broad claims, and the patent examiner will reject them as being too broad or not novel. The inventor will then amend the claims, narrowing them down to get the patent allowed. The arguments and amendments made during this process can be used to limit the interpretation of the claims later on. For instance, if an inventor explicitly stated to the patent office that their invention only works with palladium catalysts to distinguish it from prior art using other metals, they would be “estopped” from later arguing that a nickel catalyst is an equivalent. This is a nuanced area that often requires the help of a patent agent or attorney, but being aware of its existence is crucial for a sophisticated risk assessment.

Building a Proactive Patent Monitoring System

An FTO analysis is a snapshot in time. It tells you about the patent landscape on the day you conduct the search. But the landscape is constantly changing. New patents are granted every week, and new patent applications are published 18 months after they are filed. A project that is “all clear” today could be blocked by a newly granted patent six months from now. Relying on a single, one-off FTO at the beginning of a multi-year project is insufficient. You need a dynamic, ongoing monitoring system.

H4: The Limitations of One-Off Searches

A one-off FTO is better than nothing, but its value decays over time. Consider a typical drug development timeline. From project initiation to commercial launch can be 5-10 years. In that time, hundreds of thousands of new patents will have been granted worldwide. A competitor might have filed a patent application on a relevant process two years ago, before you even started your project. That application, which was secret at the time of your initial FTO, will publish 18 months after its filing date and could issue as a granted patent a few years later, right when you are preparing to scale up. This is often called the “submarine patent” problem. A proactive monitoring system is the only way to detect these emerging threats.

H4: Leveraging Technology: Patent Databases and Alerting Services

Manually monitoring the world’s patent offices is impossible. This is where technology becomes your indispensable ally. Specialized patent databases and alerting services are designed for this exact purpose. Platforms like Google Patents, the USPTO’s Patent Public Search, and Espacenet from the European Patent Office are powerful free tools for conducting initial searches.

However, for a commercial enterprise like a CDMO, professional-grade platforms offer significant advantages in terms of efficiency, comprehensiveness, and analytical power. This is where services like DrugPatentWatch become particularly valuable. These platforms are specifically tailored to the pharmaceutical industry. They not only provide robust patent search capabilities but also integrate this data with other critical information, such as regulatory filings, clinical trial data, and drug approval status.

A state-of-the-art monitoring system using such a service would involve:

- Defining Search Strategies: For each key project, you would work with an information specialist or patent attorney to create a set of targeted keyword, assignee, and classification code searches that cover the relevant technology areas (e.g., specific synthesis routes, formulation platforms, analytical methods).

- Setting Up Automated Alerts: These search strategies are then saved as automated alerts. The system will run these searches periodically (e.g., weekly) against newly published patent applications and newly granted patents.

- Receiving Curated Reports: You would then receive a curated report of any new “hits” directly to your inbox. This allows you to review a manageable list of potentially relevant new documents rather than boiling the ocean every month.

This proactive approach transforms patent monitoring from a massive, periodic chore into a manageable, ongoing business process. It provides the early warning system you need to detect and react to emerging IP threats in near real-time.

H4: Creating an Internal IP Review Process: Who, What, and When?

Technology provides the data, but humans must provide the analysis and make the decisions. A successful patent monitoring system requires a clear internal process and a dedicated team.

- Who: The review team should be cross-functional. It should include the project manager, the lead scientist(s) for the project, and an in-house or external IP counsel. The scientists understand the technology and can quickly assess whether a new patent is technically relevant. The project manager understands the business implications. The IP counsel provides the legal interpretation and risk assessment.

- What: The team’s task is to review the alert reports. For each new patent or application that seems relevant, they must conduct a preliminary analysis: Does this document appear to claim something we are currently doing or plan to do? The vast majority of hits can often be dismissed quickly as not relevant. For the small number that are potentially problematic, a deeper analysis is triggered.

- When: The review meetings should happen at a regular cadence—monthly or quarterly, depending on the risk profile of the project. This ensures that potential issues are addressed systematically and don’t fall through the cracks. The findings and decisions from these meetings must be documented to create a record of the company’s IP diligence.

By combining powerful technology with a rigorous internal process, a CDMO can build a formidable defensive wall, turning the chaotic and threatening patent landscape into a known and manageable business variable. This defensive strength is the essential prerequisite for confidently playing offense.

Case Studies in Caution: When IP Risk Management Fails

Theory and strategy are valuable, but the true impact of IP risk is best understood through tangible examples. The following hypothetical, yet realistic, case studies illustrate some of the most common and damaging IP pitfalls that can ensnare a CDMO. They serve as cautionary tales, highlighting the specific points of failure and reinforcing the importance of the defensive strategies we’ve just discussed.

The Process Patent Pitfall: Infringing on a Method of Manufacturing

The Scenario:

“SyntheSys CDMO” is a respected organization specializing in complex small-molecule API manufacturing. They are contracted by “InnovatePharma,” a mid-sized drug company, to manufacture the API for a new cardiovascular drug, “CardioClear.” InnovatePharma has a solid composition of matter patent on CardioClear. SyntheSys performs its standard FTO, which confirms that no one else has a patent on the CardioClear molecule itself. Feeling secure, they proceed.

The challenge is that the final step of the synthesis involves a tricky chiral separation to isolate the desired stereoisomer. SyntheSys’s brilliant R&D team develops a novel method using supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) with a specific co-solvent system that provides excellent purity and yield. They are proud of this internal innovation. The project moves smoothly through clinical manufacturing.

The Failure Point:

Two years into the project, as they are preparing for commercial scale-up, InnovatePharma is acquired by a Big Pharma conglomerate, “GlobalHealth Inc.” GlobalHealth’s massive patent department conducts a deep-dive audit of all of InnovatePharma’s pipeline products. They discover a broad process patent that GlobalHealth themselves had filed five years prior. The patent claims “A method for separating chiral isomers of a pyridine derivative class of compounds using SFC with a C1-C4 alcohol as a co-solvent.”

It turns out that CardioClear is a pyridine derivative, and SyntheSys’s “innovative” process used methanol (a C1 alcohol) as the co-solvent. Their process literally infringes on Claim 1 of GlobalHealth’s patent.

The Fallout:

The consequences are immediate and severe.

- Internal Conflict: GlobalHealth, now the parent company of the client, effectively sues its own contractor, SyntheSys, for patent infringement. The relationship, once a partnership, becomes adversarial overnight.

- Manufacturing Halt: GlobalHealth demands that SyntheSys immediately cease and desist from using the infringing process. All manufacturing for CardioClear comes to a grinding halt, jeopardizing the drug’s launch timeline.

- Financial Loss: SyntheSys is forced to invest heavily in a crash program to develop a new, non-infringing separation method. This “design-around” work is costly, time-consuming, and not billable to the client. They also have to negotiate a settlement with GlobalHealth for past infringement, which includes a significant damages payment.

- Reputational Damage: Word of the dispute gets out. Other potential clients become wary of working with SyntheSys, questioning the rigor of their IP management processes.

The Lesson: The FTO was too narrow. It focused only on the final product (the composition of matter) and neglected the manufacturing process. A proper FTO would have included searches for methods of making or purifying compounds of that class, not just the specific molecule. This case underscores that a CDMO’s most significant IP risk often lies in its own core competency: the process.

The Formulation Fiasco: Overlapping Excipients and Delivery Systems

The Scenario:

“FormuFast CDMO” specializes in developing advanced drug formulations, particularly long-acting injectables. They win a contract with “NeuroGen,” a biotech startup, to develop a 3-month depot injection for a new schizophrenia drug. The API is notoriously unstable and has poor solubility.

FormuFast’s formulation team rises to the challenge. After extensive experimentation, they develop a successful formulation using a specific PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) polymer with a precise molecular weight, combined with two specific solubilizing agents, Polysorbate 80 and a cyclodextrin derivative. The combination works perfectly, achieving the desired release profile and stability.

The Failure Point:

The team’s FTO search was decent but flawed. They searched for patents covering the API in combination with PLGA. They found nothing. They also searched for patents covering their specific three-part combination (PLGA + Polysorbate 80 + cyclodextrin). Again, they found nothing. They concluded they were in the clear.

However, they missed a very broad patent held by “DeliveryTech,” a specialty formulation company. The patent didn’t mention NeuroGen’s API at all. Instead, its broadest claim read: “A long-acting injectable formulation comprising: (a) a PLGA polymer with a molecular weight between 50,000 and 70,000 Da; and (b) a non-ionic surfactant; for the purpose of solubilizing a poorly water-soluble active agent.”

FormuFast’s formulation used a PLGA of 65,000 Da and Polysorbate 80 (a non-ionic surfactant) to solubilize NeuroGen’s poorly soluble API. It fell squarely within the scope of DeliveryTech’s patent.

The Fallout:

- Blocked at Launch: NeuroGen files its New Drug Application (NDA). DeliveryTech sees the filing and the disclosed formulation and immediately sues both NeuroGen and FormuFast for patent infringement. The lawsuit triggers a 30-month stay of regulatory approval under the Hatch-Waxman Act.

- Project De-railed: The entire commercial launch is put on ice for at least two and a half years while the litigation plays out. NeuroGen, a small startup, lacks the funds for a protracted legal battle and its valuation plummets.

- Loss of Credibility: FormuFast’s reputation as formulation experts is tarnished. They were hired for their specific expertise in this area, and their failure to identify such a fundamental blocking patent is seen as a major lapse in diligence. They lose the NeuroGen project and find it harder to attract new clients in the lucrative long-acting injectable space.

The Lesson: FTO searches must be conceptual, not just literal. The team searched for their exact formulation but failed to search for the broader concepts and functions involved (e.g., “PLGA for long-acting release,” “surfactants for solubilizing APIs”). The most dangerous patents are often the broad, functional ones that don’t name your specific ingredients but cover the underlying principle of what you are trying to achieve.

The “Inducement to Infringe” Trap: A CDMO’s Vicarious Liability

The Scenario:

“BioPro CDMO” is a leading manufacturer of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). They are approached by a new company, “TargetedThera,” who wants BioPro to manufacture a biosimilar version of a blockbuster cancer drug whose main patent has just expired. TargetedThera provides BioPro with a detailed legal opinion from their law firm stating that the composition of matter patent has expired and they are free to enter the market.

BioPro, relying on their client’s legal opinion and the fact that the primary patent is gone, agrees to manufacture the biosimilar. They don’t conduct a separate, in-depth FTO of their own, viewing it as a redundant expense.

The Failure Point:

The original drug developer (“BigBio”) had built a formidable “patent thicket” around their blockbuster mAb. While the main composition of matter patent had indeed expired, several secondary patents remained in force. One of these was a highly specific patent claiming “A method of treating HER2-positive breast cancer by administering [the mAb] on a three-week cycle.” Another was a formulation patent on a specific lyophilized (freeze-dried) version of the drug that included a particular stabilizer.

TargetedThera’s plan was to launch their biosimilar for the exact same indication, using the same dosing schedule. And the manufacturing process they hired BioPro to perform was designed to produce the lyophilized version covered by the formulation patent.

The Fallout:

As soon as TargetedThera launched its biosimilar, BigBio sued them for infringement of the method-of-use and formulation patents. Crucially, they also named BioPro as a co-defendant in the lawsuit. The legal complaint accused BioPro of induced infringement—by manufacturing and supplying the biosimilar with the knowledge that it would be used in an infringing manner (i.e., for the patented indication and dosing schedule), BioPro was actively inducing its client’s infringement. They were also accused of contributory infringement for supplying a product specifically designed for use in an infringing way (the patented formulation).

The Aftermath:

- Dragged into Litigation: BioPro is now embroiled in a massive, expensive lawsuit that has nothing to do with their own technology. Their defense “we were just following the client’s orders” holds no legal water.

- Indemnification Clause Tested: BioPro turns to their Master Service Agreement with TargetedThera, which contains an indemnification clause stating the client will cover the CDMO’s legal costs if the project infringes a third-party patent. However, TargetedThera is a small, under-capitalized company. They are quickly overwhelmed by the legal fees and declare bankruptcy, leaving BioPro to foot its own massive legal bill.

- Operational Disruption: BioPro is forced by court order to halt all manufacturing of the biosimilar. The capital they invested in setting up the manufacturing line now sits idle.

The Lesson: Never rely solely on a client’s IP assessment. A CDMO must perform its own independent due diligence. The MSA’s indemnification clause is only as strong as the client’s ability to pay. This case also highlights the danger of patent thickets and the need for FTOs to look beyond the primary patent to the entire web of secondary patents that often surround a successful drug. A CDMO must ask not only “Can I make this molecule?” but also “How will this molecule be formulated, packaged, and used by patients?”

These case studies paint a stark picture, but they are not meant to paralyze with fear. They are meant to instill a healthy and necessary respect for the complexities of the IP landscape. Each failure point could have been prevented with a more rigorous, comprehensive, and independent approach to IP risk management. They are the “why” behind the strategies we have discussed, proving that an ounce of prevention is worth a ton of cure.

The Offensive Strategy: Leveraging Patent Data for Business Development

For too long, the conversation about patents in the CDMO space has been dominated by risk and defense. While avoiding legal pitfalls is paramount, this focus misses the other half of the equation: the immense, proactive potential of patent data as a tool for strategic growth. When you shift your mindset from viewing patents as threats to viewing them as a rich source of business intelligence, you unlock a powerful new engine for business development. This is about moving from a reactive “we can build what you bring us” model to a proactive “we know what you’ll need, and we’re ready” approach. This offensive strategy is what separates market leaders from the rest of the pack.

The Patent Cliff as a Goldmine of Opportunity

The term “patent cliff” often strikes fear into the hearts of innovative pharmaceutical companies. It refers to the period when a blockbuster drug’s core patents expire, opening the floodgates to generic and biosimilar competition and causing a precipitous drop in revenue. For a CDMO, however, this cliff is not a precipice to be feared, but a goldmine of opportunity to be excavated.

H4: Identifying Drugs Nearing Patent Expiry

The first step is systematic intelligence gathering. Every patent has a publicly listed expiration date. By monitoring this data, a CDMO can build a clear roadmap of future market opportunities. You can, with a high degree of certainty, predict which multi-billion dollar drugs will be going off-patent in the next 3, 5, or even 10 years.

This isn’t about casual observation; it’s about building a structured, data-driven process. Using platforms that specialize in tracking pharmaceutical patents, such as the aforementioned DrugPatentWatch, a CDMO’s business development team can create a pipeline of future targets. They can filter by therapeutic area, dosage form (e.g., solid oral, injectable, topical), and molecule type (small molecule vs. biologic) to align opportunities with their specific technical capabilities. For example, a CDMO specializing in sterile manufacturing can create a target list of all injectable biologics with patents expiring between 2028 and 2030. This is no longer guesswork; it’s strategic foresight.

H4: Targeting Generic and Biosimilar Manufacturers as Future Clients

Once you have your list of upcoming patent expiries, the next step is to identify the players who will be looking to enter those markets. The generic and biosimilar industry is your future client base. These companies often operate on a different model than innovators. They are highly focused on speed to market, cost-efficiency, and reliable supply chains. They are less likely to have extensive in-house manufacturing capacity, especially for more complex products, making them ideal partners for CDMOs.

Your offensive strategy would look like this:

- Identify the Target Drug: Let’s say “CardiaBlock,” a blockbuster hypertension drug, is losing patent protection in 2029.

- Analyze the Product: Is it a simple tablet or a complex controlled-release formulation? What is the API synthesis route? What are the specific challenges in manufacturing it at scale? You gather this technical intelligence from the expired (or soon-to-be-expired) patents and other public sources.

- Identify Potential Clients: You research which generic companies have a history of producing cardiovascular drugs or have publicly stated an interest in that area. You can also monitor for new Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) or biosimilar filings, which often become public knowledge.

- Proactive Outreach: Your business development team doesn’t wait for an RFP. They reach out to the target generic companies 18-24 months before the patent expiry. The pitch is not a generic “we are a CDMO.” It’s a highly specific, value-laden proposal: “We know CardiaBlock is coming off patent. We have analyzed the manufacturing process and have already developed a non-infringing synthesis route and identified a reliable source for the key starting materials. We have available capacity in our FDA-inspected facility and can help you be one of the first to market.”

This proactive, data-driven approach is infinitely more powerful than passively waiting for inquiries. It positions your CDMO as a strategic enabler, not just a pair of hands.

H4: Using Patent Expiry Data to Forecast Manufacturing Demand

Patent expiry data is also a powerful tool for long-term capital planning and strategic investment. If your analysis shows that a wave of complex monoclonal antibodies is set to lose patent protection in the next 5-7 years, it’s a strong signal that there will be a surge in demand for mammalian cell culture capacity. This intelligence can justify a multi-million dollar investment in new bioreactors or a new sterile filling line.

By aligning your capital expenditure strategy with future, predictable market events, you can ensure your capabilities match the demand when it arrives. This prevents you from investing in the wrong technologies or having expensive equipment sit idle. It allows you to build capacity ahead of the curve, giving you a significant first-mover advantage when the wave of biosimilar development begins.

“White Space” Analysis: Finding Unmet Needs and Niche Markets

While the patent cliff focuses on exploiting existing markets, “white space” analysis is about discovering new ones. A patent white space is a technology area where there is little to no patent activity. It represents a potential gap in the market, an unmet need, or an area that is ripe for innovation. For a CDMO, identifying these white spaces can be a pathway to developing proprietary technologies that attract high-value clients and create a durable competitive advantage.

H4: What is Patent White Space?

Imagine creating a map of a specific technology domain, for example, “oral film formulations.” You would plot all the existing patents on this map. You might find dense clusters of patents around certain polymers or taste-masking technologies—these are “hot” areas with many players. But you might also find empty areas on the map—the “white space.” Perhaps there are very few patents related to using oral films for delivering biologic drugs, or for achieving a specific biphasic release profile.

These gaps can exist for several reasons: the technology might not be feasible, there may be no perceived market need, or—most interestingly—it might be an area that established players have simply overlooked. It is in this last category that opportunity lies.

H4: How CDMOs Can Identify Gaps in Formulation and Manufacturing Technology

Conducting a white space analysis requires specialized patent analytics tools that can create visual landscapes and heat maps of patent data. The process for a CDMO might look like this:

- Define the Domain: Choose a technology area that is core to your business or is an adjacent area you are considering entering. For instance, a CDMO specializing in lyophilization might analyze the white space around “novel excipients for improving the stability of lyophilized biologics.”

- Map the Landscape: Using patent analytics software, you would pull all the patents in this domain and categorize them based on technical features (e.g., type of excipient, type of biologic, specific stability problem being solved).

- Visualize and Analyze: The software can then generate a topographical map. The “peaks” and “hot zones” are crowded areas. The “valleys” and “blue oceans” are the white spaces.

- Validate the Opportunity: Once a white space is identified (e.g., a lack of patents on stabilizers for mRNA-based vaccines), the next step is to validate it. Is this a real technical challenge the industry is facing? Would developing a solution create significant value for potential clients? This involves talking to industry experts, attending conferences, and reading scientific literature.

H4: Developing Proprietary Technologies to Attract High-Value Clients

If the white space represents a genuine, valuable opportunity, the CDMO can then dedicate R&D resources to “fill” that space by developing its own proprietary technology. For example, the CDMO could develop and patent a new platform of excipients that dramatically improves the shelf life of lyophilized mRNA products.

This changes the entire business dynamic. You are no longer just a service provider. You are now the owner of a valuable, patent-protected technology platform. When a biotech company developing an mRNA vaccine comes to you, you are not just offering manufacturing capacity; you are offering an elegant solution to one of their most critical challenges. This allows you to:

- Command Higher Margins: You can license your proprietary technology as part of the manufacturing agreement, leading to higher-value contracts.

- Create “Sticky” Client Relationships: Once a client’s product is formulated with your proprietary technology, it is very difficult and expensive for them to switch to another CDMO. You become an integral part of their product’s success.

- Build a Reputation for Innovation: You are seen not just as a reliable manufacturer, but as a scientific leader and problem-solver, which attracts more cutting-edge clients.

Competitive Intelligence: Mapping the Landscape to Your Advantage

Patent filings are one of the most reliable and timely indicators of a company’s strategic direction and R&D activities. Because patent applications are typically published 18 months after filing, they provide a window into a company’s pipeline long before that information appears in a press release or clinical trial registry. For a CDMO, this is an invaluable source of competitive intelligence.

H4: Analyzing Competitors’ Patent Filings

First, you can monitor the patent activity of your direct CDMO competitors. What new manufacturing processes are they trying to patent? Are they developing expertise in a new area like continuous manufacturing or cell therapy production? This intelligence can inform your own strategic planning and help you avoid being technologically outmaneuvered. If your main competitor is filing a flurry of patents related to antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), it’s a clear sign that you need to assess your own capabilities in that hot market.

H4: Understanding the R&D Trajectories of Potential Pharma Partners

Even more powerfully, you can track the patent filings of your potential clients—the innovative pharma and biotech companies. By setting up alerts for the companies on your target list, you can see exactly what they are working on.

- Are they moving into a new therapeutic area?

- Are they filing patents on complex molecules that will be difficult to manufacture?

- Are their patents focused on a specific delivery technology, like oral biologics or microneedle patches?

This information allows you to anticipate their future needs. If you see a promising small biotech company filing its first key patents on a novel class of compounds, you can predict that in 12-18 months, they will be looking for a CDMO to help them with process development and clinical trial material manufacturing. You can get on their radar early, building a relationship long before they issue a formal RFP.

H4: Using Patent Data to Tailor Your Business Pitch

This intelligence culminates in the ability to craft highly customized and compelling business proposals. When you walk into a meeting with a potential client, you can move beyond the standard capabilities presentation.

Imagine this pitch:

“We’ve been following your recent patent filings, including application number WO2025/12345 on your new family of bicyclic peptides. We were impressed by the chemistry, and we noticed that the synthesis involves a solid-phase peptide synthesis followed by a challenging on-resin cyclization step. Our team has extensive experience with exactly this type of chemistry. In fact, we recently scaled up a similar process for another client, and we’ve already modeled a potential manufacturing route for your compounds that we believe can optimize yield by 15%. We have capacity available in our peptide synthesis suite starting in Q3 of next year, which aligns perfectly with your likely preclinical timeline.”

A pitch like this demonstrates a level of preparation, expertise, and genuine partnership that is impossible to achieve without leveraging patent intelligence. It shows you’ve done your homework, you understand their science, and you are already thinking about how to solve their problems. This is how you win the high-value contracts that define a market-leading CDMO. It transforms the sales process from a service offering into a strategic consultation.

Building an IP-Centric Culture within Your CDMO

Mastering the defensive and offensive use of patent data is not merely a task for the legal department or a small business development team. To truly transform intellectual property from a liability into a strategic asset, its principles must be woven into the very fabric of your organization. It requires building an “IP-centric culture,” where every employee, from the CEO to the lab technician, understands their role in protecting the company and its clients and in identifying new opportunities. This cultural shift requires a conscious, top-down effort in leadership, training, and robust internal processes.

From the C-Suite to the Lab Bench: Fostering IP Awareness

An IP-centric culture starts at the top but must be cultivated at every level. It’s a shared responsibility that, when embraced, creates a powerful human firewall against risk and a company-wide radar for innovation.

H4: The Role of Leadership in Championing IP Strategy

The C-suite, and particularly the CEO, must be the primary champion of the IP strategy. This goes far beyond simply allocating a budget for patent attorneys. It means:

- Integrating IP into Business Strategy: IP considerations should be a standard agenda item in all strategic planning meetings. When discussing market expansion, capital investments, or potential acquisitions, the question “What are the IP implications?” must be asked.

- Articulating a Clear Vision: Leadership must clearly and repeatedly communicate the dual role of IP—as both a shield and a sword—to the entire organization. Employees need to understand why their attention to IP matters to the company’s bottom line and long-term success.

- Allocating Resources: Building an IP-centric culture requires investment in the right tools (e.g., patent search platforms), the right people (e.g., in-house IP managers or strong relationships with expert outside counsel), and, most importantly, the time for training and due diligence.

- Setting the Tone: When leadership actively discusses patent landscapes, celebrates the development of proprietary know-how, and rewards employees for identifying IP-related risks or opportunities, it sends a powerful message that this is a core value of the company.

“IP strategy cannot be a silo,” notes Irina Shulga, a partner at a life sciences venture capital firm. “When we evaluate a CDMO for a potential partnership, we look for an executive team that can speak as fluently about their IP management approach as they can about their manufacturing capacity. It’s a key indicator of sophistication and a well-run business.” [3]

H4: Training Programs for Scientists, Engineers, and Project Managers

Your scientists, engineers, and project managers are on the front lines of IP creation and risk. They are the ones developing the new processes, solving the technical problems, and interacting with clients daily. They do not need to be lawyers, but they need foundational IP literacy.

A continuous training program is essential and should be tailored to their specific roles:

- For Scientists and Engineers:

- Lab Notebook Best Practices: How to properly document experiments to prove date of invention and create a clear record of what was done. This is critical for both patent applications and defending against infringement claims.

- Understanding Confidentiality: The difference between public information and a client’s or the company’s confidential information/trade secrets. Real-world scenarios can be used to illustrate the risks of casual conversation or “cross-pollination” of ideas between projects.

- Recognizing Potential Inventions: Training them to spot when they’ve created something potentially patentable—a new process, an improved formulation, a novel analytical method—and know who to report it to. This creates an internal pipeline of innovation.

- For Project Managers:

- The Basics of FTO: What an FTO is, why it’s important, and what its scope should be. They need to be able to have intelligent conversations with clients and legal counsel about FTO results.

- Understanding MSAs: A deep dive into the key IP clauses of the Master Service Agreement (MSA), so they can understand the contractual obligations they are managing.

- Client Communication: How to discuss IP issues with clients professionally and collaboratively, framing due diligence not as a hurdle, but as a mutual best practice.

These training sessions should be practical, engaging, and recurring. An annual refresher is a good start, but IP awareness should be a constant theme in project meetings and team updates.

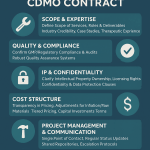

The Master Service Agreement (MSA): Your Legal Fortress

If culture is the human firewall, the Master Service Agreement (MSA) is your legal fortress. This contract governs the entire relationship with your client and is the single most important document for defining IP rights, responsibilities, and liabilities. A poorly drafted MSA can leave you dangerously exposed, while a well-crafted one can be your ultimate shield. Never treat the MSA as boilerplate; it is a critical strategic document that deserves intense scrutiny.

H4: Key IP Clauses to Include: Indemnification, IP Ownership, and Confidentiality

Every MSA is negotiable, but there are several cornerstone IP clauses that a CDMO should consider non-negotiable in principle, even if the exact wording is debated.

- Confidentiality: This clause must be robust and clear. It should define what constitutes “Confidential Information,” the obligations of the receiving party (you) to protect it, and the duration of those obligations (which should ideally survive the termination of the agreement).

- Ownership of Intellectual Property: This is often the most heavily negotiated section. It needs to clearly delineate between:

- Background IP: The IP that each party brings to the project. The clause should state that each party retains ownership of its own Background IP.

- Foreground IP (or Arising IP): The IP that is created during the project. This is where it gets complex. Will the client own all arising IP? Will the CDMO own its process improvements? A common and fair approach is for the client to own inventions directly related to their molecule or product, while the CDMO retains ownership of any new, generally applicable improvements to its own manufacturing processes or technologies. This allows the CDMO to build its own proprietary asset base.

- Indemnification: This clause is your safety net. In its ideal form for the CDMO, it should state that the client will indemnify (i.e., defend and cover the costs of) the CDMO against any third-party infringement claims arising from the work performed, provided the CDMO was acting on the client’s instructions and information. As we saw in the case studies, this is only as good as the client’s financial stability, but it is an essential legal protection to have. You may also be asked to provide a reciprocal indemnification for any infringement caused by your own background IP or gross negligence.

- Patent Prosecution and Maintenance: If the CDMO is creating patentable inventions that it will own, the MSA should specify who is responsible for the cost and effort of filing and maintaining those patents.

H4: Negotiating IP Terms with Clients: Balancing Protection and Partnership

Negotiating MSAs is a delicate art. You want to protect your company, but you don’t want to be so rigid that you scare away clients. The key is to approach it as a partnership-building exercise.

- Educate the Client: Especially with smaller biotech companies who may be less experienced, take the time to explain why you are asking for certain clauses. Frame it as a way to prevent future misunderstandings and ensure a smooth, successful project for both parties.

- Know Your BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement): Before entering negotiations, know your walk-away points. For example, you might be flexible on some IP ownership points, but an MSA with no client indemnification for third-party infringement might be a red line you will not cross.

- Seek Win-Win Solutions: Often, there are creative ways to structure IP ownership. For example, if you develop a valuable process improvement, you might grant the client an exclusive, royalty-free license for their specific product, while you retain ownership and the right to use the improvement for other clients in different fields. This gives the client what they need while allowing you to leverage your innovation.

- Involve Legal Counsel Early: Don’t wait until the last minute to have your lawyers review the MSA. They should be involved early in the process to help you craft a negotiating strategy that aligns with your overall business and IP goals.

Document Everything: The Critical Role of Lab Notebooks and Batch Records

In the world of intellectual property, an un-documented discovery is, for all legal purposes, a discovery that never happened. Meticulous, contemporaneous documentation is the bedrock of any strong IP position. It is your evidence, your proof, your primary defense in a dispute, and your foundation for a patent application.

H4: Creating an “Inventive Step” Paper Trail

To obtain a patent, an invention must be novel and non-obvious (it must involve an “inventive step”). To defend your work, you often need to prove when you invented something. This is where the humble lab notebook (whether physical or electronic) becomes a hero.

Your scientists must be trained to document not just their successes, but their thought processes, their hypotheses, their failures, and their observations. A notebook entry that reads “Experiment 7 failed, yield was low” is of little value. A great notebook entry reads: “Hypothesis: Increasing the reaction temperature to 80°C will drive the reaction to completion. Result: Temperature increase to 80°C resulted in significant byproduct formation (see chromatogram #123). New Hypothesis: The reaction may be catalyzed by trace metals. Will try again with a metal scavenger. This detailed record creates a paper trail of the inventive process. It can be used by a patent attorney to draft a stronger patent application and can be invaluable in proving that your team, not someone else, was the true inventor.

H4: Proving Prior Use and Defending Against Infringement Claims

Good documentation is also a powerful defensive tool. In the United States, there are “prior use” rights that can, in some cases, provide a defense against patent infringement if you can prove you were commercially using a secret process before the patent holder filed their application. This defense is entirely dependent on your ability to produce clear, dated, and verifiable records—like signed and witnessed batch records, SOPs, and development reports—that prove you were using the process at that earlier date.

Without meticulous records, you are left with nothing but personal testimony, which carries far less weight in a courtroom. In essence, building an IP-centric culture means instilling a discipline of documentation that is as rigorous and ingrained as your cGMP compliance. It’s not just red tape; it’s the ammunition you need to defend your fortress and prove ownership of the treasures you find.

The Future of CDMOs and IP: Emerging Trends and Predictions

The pharmaceutical landscape is in a constant state of flux, and the world of intellectual property is evolving right along with it. For a CDMO to maintain its competitive edge, it’s not enough to master the IP challenges of today; you must also anticipate the trends that will define the market of tomorrow. The rise of complex biologics, the transformative power of artificial intelligence, and the shifting sands of global patent law are three key areas that will profoundly shape the future of IP management for CDMOs.

The Rise of Biologics and Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs)

The era of the small-molecule blockbuster, while far from over, is now sharing the stage with a new class of incredibly complex and powerful therapies. Biologics like monoclonal antibodies have been joined by even more sophisticated Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), which include cell therapies (like CAR-T), gene therapies, and tissue-engineered products. The global cell and gene therapy market size was valued at USD 22.9 billion in 2023 and is expected to expand at a CAGR of 22.4% from 2024 to 2030 [4]. This explosive growth presents a monumental opportunity for CDMOs, but also an IP landscape of unprecedented complexity.

H4: The Complex IP Landscape of Cell and Gene Therapies

Unlike a small molecule that might be covered by a handful of patents (composition of matter, process, formulation), a single cell or gene therapy product can be a nexus of dozens, if not hundreds, of distinct IP rights held by numerous different entities. Consider a CAR-T therapy:

- The Target Antigen: The protein on the cancer cell that the therapy targets may be patented.

- The Antibody Fragment (scFv): The part of the CAR that recognizes the antigen is typically covered by its own patent.

- The CAR Construct: The specific genetic design of the chimeric antigen receptor, including its hinge and signaling domains, is a hotbed of patenting activity.

- The Vector: The viral vector (often a lentivirus) used to deliver the CAR gene into the T-cells is likely covered by a web of patents owned by universities and specialized biotech companies.

- Cell Culture Media and Reagents: The specific “cocktail” used to grow and activate the T-cells may contain patented growth factors or small molecules.

- The Manufacturing Process: The methods for transducing the cells, expanding them in a bioreactor, and cryopreserving the final product are all patentable.

For a CDMO entering this space, the FTO analysis is an order of magnitude more complex than for a traditional API. You must “de-stack” the entire technology platform and investigate the IP status of every single component and process step. A failure to secure the necessary licenses for even one small part of this stack—like the viral vector—can bring the entire project to a halt.

H4: How CDMOs Can Specialize and Differentiate in These Areas

This complexity, however, creates opportunity. CDMOs can differentiate themselves by becoming specialists not just in manufacturing, but in navigating the IP of these complex modalities. A CDMO that can offer a “pre-cleared” manufacturing platform—where they have already taken licenses to key underlying technologies like a specific viral vector or cell culture system—provides immense value to a small biotech. This saves the client time, money, and significant legal headaches, making the CDMO an incredibly attractive partner.

Furthermore, there is significant white space for innovation in the manufacturing of ATMPs. Improving the efficiency of vector production, developing closed and automated cell processing systems, and creating better cryopreservation techniques are all areas where a CDMO can develop its own valuable, patent-protected IP, creating a powerful competitive moat in this rapidly growing market.

The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Patent Analysis and R&D

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are no longer science fiction; they are rapidly becoming practical tools that are reshaping R&D and IP management. For CDMOs, AI presents a dual opportunity: to supercharge their patent analysis capabilities and to enhance their own development processes.

- AI-Powered Patent Search and Analysis: Traditional patent searching relies on keywords and classification codes. This can be a blunt instrument, often returning thousands of irrelevant results while missing key patents that use different terminology. AI-powered search engines can understand context and concepts. They can perform semantic searches that find patents based on the meaning of the technology described, not just the words used. This allows for faster, more accurate, and more comprehensive FTO and white space analyses. AI tools can also automate the process of categorizing patents, generating landscape maps, and even providing a first-pass assessment of a patent’s relevance, freeing up human experts to focus on the most critical documents.

- AI in Process Development: CDMOs can use AI to accelerate their own R&D. Machine learning models can analyze data from past experiments to predict the optimal reaction conditions, select the best formulation excipients, or identify the most efficient purification methods. This can dramatically reduce the number of experiments needed, saving time and resources.

- The IP of AI-generated Inventions: An emerging and fascinating legal question is: who owns an invention created by an AI? Can an AI be listed as an inventor on a patent? Patent offices around the world are grappling with this issue. For now, the consensus is that a human inventor is required. However, as AI becomes more integral to the inventive process, CDMOs will need clear policies and documentation practices to identify and protect the human contributions that guide and direct these powerful tools, ensuring that AI-generated innovations can be protected as the company’s own IP.

Globalization and the Harmonization (or lack thereof) of Patent Law

A CDMO’s business is inherently global. You may have a client in Europe, source raw materials from India, manufacture in the United States, and ship the final product to Japan. This global footprint means you must navigate a patchwork of national and regional patent laws. While there have been efforts toward harmonization, significant differences remain.

- Varying Patentability Standards: What is patentable in the U.S. might not be patentable in Europe or China. For example, the European Patent Office has stricter standards for the patentability of software and business methods than the USPTO. Methods of medical treatment are patentable in the U.S., but generally not in Europe (where they are protected by a different “purpose-limited” claim format).

- Different Enforcement Mechanisms: The process for litigating a patent, the remedies available (e.g., injunctions), and the cost of enforcement vary dramatically from country to country. The recent introduction of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) in Europe is a major development, creating a single forum for patent litigation across many EU member states, which could streamline enforcement but also increase the stakes of a single lawsuit.

- The Rise of China as an IP Powerhouse: China has rapidly transformed from a nation known for IP infringement to one of the most prolific patent-filing and aggressive patent-enforcing jurisdictions in the world. Any CDMO with operations, suppliers, or clients in China must have a sophisticated China-specific IP strategy.

For a CDMO, this means that a single FTO for the United States is not sufficient. A proper global FTO must be conducted, considering the patent laws and databases of every key market where the product will be developed, manufactured, or sold. This requires global expertise and access to international patent databases. Ignoring the patent landscape of even one key country can create a “back door” for a competitor or a legal blind spot that could have global repercussions for your business and your client. The future belongs to those CDMOs who can think and act with a truly global IP perspective.

Conclusion: Transforming IP from a Liability to a Strategic Asset

We have journeyed through the intricate and often intimidating world of intellectual property from the unique vantage point of a Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization. We began by acknowledging the precarious position CDMOs occupy—at the very heart of pharmaceutical innovation, yet perpetually exposed to the complex IP of their clients and the broader market. The initial instinct is one of defense, of seeing the patent landscape as a minefield to be navigated with caution, and this instinct is correct. A robust, proactive defensive strategy, anchored by comprehensive Freedom-to-Operate analyses, meticulous documentation, and strong contractual protections, is the non-negotiable price of entry for operating successfully in this space. As we’ve seen through cautionary tales, ignoring this foundation is a recipe for disaster.

But the central thesis of this guide is that a purely defensive posture is a missed opportunity. It’s like owning a powerful sailing ship and only ever using it to stay safe in the harbor. The true art of seamanship—and of modern CDMO leadership—lies in understanding how to harness the winds of the open ocean to reach new and valuable destinations. The vast, public database of patents is not just a collection of legal threats; it is the most comprehensive and timely source of business intelligence the pharmaceutical industry has to offer.