A new and disruptive force has emerged American pharmaceutical industry, operating at the dynamic intersection of manufacturing, pharmacy practice, and intellectual property law. These entities, known as 503B outsourcing facilities, were born from a public health crisis and codified into existence by the Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013.1 They represent a fundamental shift in the drug supply chain, a hybrid model designed to bridge the gap between traditional, patient-specific compounding and large-scale pharmaceutical manufacturing.2 While they provide critical solutions to challenges like drug shortages and the need for specialized sterile preparations, they also operate within a complex legal gray zone, constantly navigating the formidable fortress of U.S. drug patent law.

The traditional paradigm of pharmaceutical competition is well-defined, governed by the intricate dance between innovator drug companies and generic manufacturers under the Hatch-Waxman Act.4 This framework, however, is largely inapplicable to 503B facilities, which are exempt from the standard new drug approval process that triggers this established system of patent litigation.1 This exemption creates a unique and often perilous environment. It opens specific, high-stakes opportunities for market entry and innovation but also exposes these facilities to novel legal threats from patent holders seeking to protect their market exclusivity.

This report provides a definitive, expert-level analysis of this new frontier. It moves beyond a simple recitation of regulations to deliver a nuanced examination of the legal loopholes, innovative business models, litigation risks, and market opportunities that define the 503B sector. We will dissect the statutory provisions that both empower and constrain these facilities, explore the strategic pathways they are forging to create value, and analyze the real-world legal battles that are shaping the boundaries of this evolving industry. For pharmaceutical and biotech executives, intellectual property strategists, legal counsel, and investors, this report serves as a comprehensive playbook for understanding and capitalizing on the opportunities presented by 503B outsourcing facilities, while strategically mitigating the profound risks inherent in breaking the barriers of drug patent law.

The New Frontier: Understanding the 503B Outsourcing Facility Landscape

To grasp the innovative and often contentious role 503B outsourcing facilities play in the context of drug patents, one must first understand their unique regulatory and operational foundation. They are not simply large-scale pharmacies, nor are they conventional drug manufacturers; they are a distinct category of entity created by Congress for a specific purpose, with a unique set of rules that dictates their every action. This foundation explains why traditional models of patent analysis and litigation are insufficient and why new strategies are required for both the 503B facilities and the innovator companies they challenge.

From Crisis to Creation: The DQSA and the Birth of the 503B Model

The genesis of the 503B outsourcing facility is not a story of market innovation but of regulatory necessity born from a tragic public health failure. In 2012, the United States was rocked by a nationwide fungal meningitis outbreak traced back to contaminated steroid injections prepared by the New England Compounding Center (NECC) in Massachusetts.7 The NECC was operating in a regulatory gray area, functioning not as a traditional pharmacy compounding medications for individual patients, but as a large-scale, unregistered manufacturer shipping thousands of vials of sterile products across state lines with little oversight. The resulting outbreak led to over 60 deaths and hundreds of illnesses, starkly exposing the dangers of unregulated, large-scale compounding.7

This crisis served as a powerful catalyst for legislative action. Congress recognized an urgent need to close the regulatory gap between small, state-regulated compounding pharmacies and federally regulated drug manufacturers. The result was the Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA), signed into law on November 27, 2013.1 The DQSA was a landmark piece of legislation that fundamentally reshaped the landscape of drug compounding in the U.S..2

At its core, Title I of the DQSA, known as the Compounding Quality Act, created a new, voluntary designation for compounders under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act.1 This new section defined an “outsourcing facility” as a facility at a single geographic location that is engaged in the compounding of sterile drugs, has voluntarily elected to register with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and complies with all of the requirements of Section 503B.1

By registering with the FDA, these facilities could legally compound and ship large batches of sterile drugs to hospitals, clinics, and physician offices without first receiving patient-specific prescriptions—a practice that was at the heart of the NECC’s illicit operations.8 However, this authority came with significant new responsibilities. In exchange for these exemptions from new drug approval and certain labeling requirements, outsourcing facilities were required to adhere to a stringent set of federal rules, bringing them directly under the oversight of the FDA.1 These rules include mandatory compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), regular risk-based inspections by the FDA, and mandatory reporting of the products they compound and any adverse events associated with them.1 The DQSA effectively created a new tier in the pharmaceutical ecosystem, one intended to provide a reliable source of high-quality compounded medications while ensuring a level of safety and oversight that was previously absent.

A Tale of Two Compounders: The Critical Distinctions Between 503B and 503A

The DQSA created a clear bifurcation in the world of compounding, drawing a bright line between the newly established 503B outsourcing facilities and the traditional compounding pharmacies, which are now governed by Section 503A of the FD&C Act.8 Understanding the profound differences between these two models is essential, as their distinct regulatory frameworks dictate their operational capabilities, market roles, and legal risks, particularly concerning intellectual property.

The most fundamental distinction lies in regulatory oversight and quality standards. 503A pharmacies are the familiar, often local, compounding pharmacies. They are primarily regulated by state boards of pharmacy and are required to comply with the standards set forth by the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), specifically USP General Chapters for non-sterile compounding and for sterile compounding.13 While the FDA retains some authority to inspect 503A facilities, particularly for insanitary conditions, the day-to-day oversight rests with the states.11 Crucially, 503A facilities are explicitly exempt from the FDA’s cGMP requirements.12

In stark contrast, 503B outsourcing facilities are primarily regulated by the FDA.11 Upon voluntary registration, they subject themselves to a much higher and more rigorous quality standard: they must fully comply with cGMP, as detailed in 21 CFR Parts 210 and 211.13 This is the very same quality standard that large pharmaceutical manufacturers like Pfizer and Merck must follow, placing 503B facilities in a different operational universe from their 503A counterparts.13

This difference in quality standards directly enables a difference in the scale of operations. A 503A pharmacy is strictly limited to compounding medications pursuant to a valid, patient-specific prescription.8 While they are permitted to engage in “anticipatory compounding” of limited quantities before receiving a prescription, the final product can only be dispensed to an identified individual patient.11 They are generally prohibited from compounding large batches for “office use” by healthcare providers. Furthermore, their ability to distribute products across state lines is restricted; under Section 503A, a pharmacy cannot distribute more than 5% of its total prescription orders interstate unless its state has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the FDA.8

503B facilities operate under a completely different model. They are not required to obtain patient-specific prescriptions before compounding.8 This exemption allows them to produce large, homogenous batches of sterile drugs in anticipation of orders from hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, and clinics for office stock.2 Because they are federally registered and regulated, there are no federal limits on their ability to ship these products across state lines, enabling a national distribution model.11 The following table summarizes these critical distinctions.

| Feature | Section 503A Compounding Pharmacy | Section 503B Outsourcing Facility |

| Primary Regulatory Authority | State Boards of Pharmacy 11 | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 11 |

| Governing Quality Standard | USP & 13 | Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) 13 |

| Prescription Requirement | Required for an identified individual patient 8 | Not required; can compound for “office use” 8 |

| Scale of Production | Small-scale, patient-specific batches 13 | Large-scale, bulk batch production 13 |

| Interstate Distribution Limits | Limited to 5% of total prescriptions absent an MOU 8 | No federal limit on interstate distribution 11 |

| FDA Registration | Not required (state-licensed) 16 | Voluntary, but required to operate as an outsourcing facility 1 |

| Adverse Event Reporting | Not federally mandated to report to FDA | Mandatory reporting to FDA 1 |

| Labeling Requirements | State-specific prescription labeling | Specific federal labeling requirements, including “This is a compounded drug” and “Not for resale” 17 |

| Exemption from New Drug Approval | Yes, if compliant with 503A conditions 18 | Yes, if compliant with 503B conditions 1 |

The cGMP Imperative: Operating at the Nexus of Pharmacy and Manufacturing

The single most consequential requirement separating 503B facilities from all other pharmacies is the mandate to comply with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP).1 This is not merely a suggestion or a best practice; it is a legally enforceable, comprehensive quality system that fundamentally defines the nature, cost, and value of a 503B outsourcing facility. The cGMP regulations, outlined in 21 CFR Parts 210 and 211, are designed to ensure that drug products are manufactured with the proper identity, strength, quality, and purity.13 For a 503B facility, this means operating less like a pharmacy and more like a scaled-down pharmaceutical manufacturing plant.2

Adherence to cGMP necessitates a profound investment in infrastructure, processes, and personnel. Operationally, it requires the design and construction of purpose-built, validated cleanrooms that meet stringent ISO air quality standards.19 These environments must be supported by sophisticated, qualified systems for air handling (HVAC), water purification, and environmental monitoring that continuously track particle counts, temperature, humidity, and pressure differentials.2 All surfaces—walls, floors, and ceilings—must be smooth, non-shedding, and resistant to frequent sanitization.19

The cGMP framework extends far beyond the physical facility. It demands rigorous process validation for every aspect of production.13 Before a new product can be brought to market, a 503B facility must produce multiple validation batches and subject them to extensive testing to prove the process is controlled, repeatable, and consistently yields a product that meets pre-defined specifications.13 This includes robust stability testing to scientifically justify the Beyond-Use Dates (BUDs) assigned to products, which are often significantly longer than those possible for 503A-compounded preparations.14

Furthermore, cGMP mandates the establishment of an independent Quality Control Unit (QCU) that has the authority and responsibility to approve or reject all components, in-process materials, and finished drug products.2 This unit operates independently from production and sales, ensuring that quality decisions are not compromised by commercial pressures.13 Every step, from the vetting of raw material suppliers to the final release of a product batch, must be governed by written procedures and meticulously documented, creating an exhaustive audit trail ready for FDA inspection at any time.2

This cGMP imperative functions as both the primary economic barrier to entry into the 503B market and the ultimate source of a facility’s competitive advantage. The substantial capital investment required to build and maintain a cGMP-compliant facility, which can run into the tens of millions of dollars, naturally limits the number of market participants.20 However, this very investment is what creates the value proposition that healthcare systems are willing to pay for. In the post-NECC era, hospitals and clinics are acutely aware of the risks of contaminated compounded drugs. The assurance of cGMP-level quality, validated processes, extended BUDs that reduce waste, and reliable large-batch production provides a level of safety and operational efficiency that traditional 503A pharmacies cannot match.2 Therefore, the cGMP requirement is the central pillar of the 503B business model; it is the cost of doing business, but it is also the product being sold. This high standard of quality is what allows 503B facilities to function as a trusted and integral part of the national drug supply chain.

The Patent Fortress: A Primer on Intellectual Property in Pharmaceuticals

To navigate the complex relationship between 503B outsourcing facilities and drug patents, it is essential to first understand the formidable structure of intellectual property (IP) protection that surrounds pharmaceuticals in the United States. This “patent fortress” is not a single wall but a multi-layered defense system designed to provide innovators with a period of market exclusivity to recoup the immense costs of drug development, which can range from hundreds of millions to billions of dollars and take over a decade to complete.21 This system is built upon two distinct but complementary pillars: patents granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and regulatory exclusivities granted by the FDA.

The Twin Pillars of Protection: Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities

The first and most fundamental pillar of protection is the patent. A patent is a legal property right granted by the USPTO to an inventor, giving them the exclusive right to make, use, sell, or import their invention for a limited time.21 In exchange for this temporary monopoly, the inventor must publicly disclose the details of the invention, which fuels further innovation by allowing other researchers to build upon that knowledge.24 For a pharmaceutical invention to be patentable, it must meet three core criteria: it must be useful, novel (not previously known), and non-obvious to an expert in the field.24 The standard term for a new patent is 20 years from the date the application is filed.23

Pharmaceutical products are often protected by a “patent estate” consisting of multiple patents covering different aspects of the drug. Key types of patents include 21:

- Composition of Matter Patents: These are the most powerful patents, covering the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. They are the crown jewels of a drug’s IP portfolio.

- Method of Use Patents: These patents protect a specific method of using a drug to treat a particular disease or condition.

- Formulation Patents: These cover the specific combination of the API with other inactive ingredients (excipients) to create the final drug product, such as an extended-release tablet or a stabilized injectable solution.

- Process Patents: These protect a specific, novel method of manufacturing the drug.

The second pillar of protection is regulatory exclusivity. Unlike patents, which are granted by the USPTO based on the novelty of an invention, regulatory exclusivities are marketing rights granted by the FDA upon the approval of a new drug.23 These exclusivities are defined by statute and are designed to incentivize research in specific areas or for specific populations. They run independently of a drug’s patent status; a drug can have both patent protection and exclusivity, one, or neither.24 During a period of exclusivity, the FDA is barred from approving certain types of competitor applications, most notably generic drugs.

Key types of regulatory exclusivity include 23:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: Provides 5 years of market exclusivity for a drug containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): Grants 7 years of exclusivity to incentivize the development of drugs for rare diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: Provides 3 years of exclusivity for a new use or formulation of a previously approved drug, provided that new clinical studies were essential to the approval.

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): Adds an extra 6 months of exclusivity to any existing patents and other exclusivities a drug may have, as a reward for conducting pediatric studies requested by the FDA.

These two pillars work in concert to create a robust and overlapping period of market protection for innovator drugs, forming the legal and economic landscape that any potential competitor, including a 503B facility, must carefully navigate.

The Gatekeepers: The Hatch-Waxman Act and the FDA’s Orange Book

The modern system governing the interplay between branded and generic drugs was established by the landmark 1984 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.4 This legislation masterfully balanced two competing interests: it preserved the incentives for pharmaceutical innovation while simultaneously creating a streamlined pathway for lower-cost generic drugs to enter the market once patents and exclusivities expired.5

The Act’s central innovation was the creation of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway.4 Under this pathway, a generic drug manufacturer does not need to conduct its own costly and time-consuming clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy. Instead, it can rely on the FDA’s previous findings for the innovator (or “reference”) drug, and need only demonstrate that its product is bioequivalent to the original.24

To manage the patent disputes inherent in this system, the Hatch-Waxman Act created a formal, highly structured process centered on the FDA’s publication, “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” universally known as the Orange Book.23 The Orange Book is the official register of all FDA-approved drugs, their therapeutic equivalence ratings, and, most importantly, the patents and regulatory exclusivities that protect them.25 When an innovator company receives approval for a new drug, it must submit a list of all patents that claim the drug substance, drug product, or method of use for listing in the Orange Book.26

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug. The most significant of these is the “Paragraph IV” certification, in which the generic applicant asserts that the innovator’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.23 The filing of a Paragraph IV certification is considered a technical act of patent infringement, which provides the brand manufacturer with a 45-day window to sue the generic applicant.27 If a lawsuit is filed, the FDA is automatically barred from approving the ANDA for up to 30 months, allowing time for the patent litigation to be resolved in court.27 To incentivize these patent challenges, the Act grants 180 days of market exclusivity to the first generic applicant to successfully file a Paragraph IV certification.23

This entire, carefully constructed framework of patent listings, certifications, and litigation stays is the bedrock of brand-generic competition in the United States. However, its relevance is predicated entirely on the filing of an ANDA. As established, Section 503B of the FD&C Act explicitly exempts outsourcing facilities from the new drug approval requirements, meaning they do not file NDAs or ANDAs.1 This critical distinction places 503B facilities entirely outside the established Hatch-Waxman system. They do not make Paragraph IV certifications, they are not subject to the 30-month stay, and they are not eligible for 180-day exclusivity. This creates a legal vacuum, forcing brand manufacturers who feel their market is being encroached upon by a 503B facility to abandon the familiar Hatch-Waxman playbook and seek alternative, often more creative, legal strategies to defend their intellectual property. This unique legal status is the source of both the greatest opportunities and the most significant risks for the 503B industry.

The Legal Gray Zone: Where 503B Compounding and Patent Law Collide

The 503B outsourcing facility model exists in a precarious legal space, defined by a fundamental tension. On one hand, the DQSA grants these facilities an exemption from the new drug approval process, placing them outside the traditional patent litigation framework. On the other hand, the Act imposes strict limitations designed to prevent them from becoming unregulated generic manufacturers. This collision of regulatory exemptions and statutory prohibitions creates a complex legal gray zone where the lines between permissible compounding and patent infringement are constantly being tested and redrawn in courtrooms and through FDA guidance. Navigating this gray zone is the single greatest challenge and strategic imperative for any 503B facility.

The “Essentially a Copy” Conundrum

At the very heart of the legal framework governing 503B facilities is a single, powerful prohibition: a compounded drug product cannot be “essentially a copy of one or more approved drugs” to qualify for the exemptions under Section 503B.10 This clause is the primary statutory guardrail intended to protect the integrity of the FDA’s drug approval process and, by extension, the value of drug patents.10 It ensures that 503B facilities fulfill their intended purpose—meeting patient needs that cannot be met by an FDA-approved drug—rather than simply producing cheaper, unapproved versions of commercially available products.10

The FDA defines “essentially a copy” as a drug that is “identical or nearly identical” to an approved drug product.10 The agency’s evaluation of whether a compounded product is “nearly identical” is a multi-factor analysis that considers key characteristics of the drug, including:

- The active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)

- The route of administration

- The dosage form

- The dosage strength

- The excipients (in some cases)

If a compounded drug has the same API, is intended for the same route of administration, and has a similar dosage form and strength as a commercially available, FDA-approved drug, it will almost certainly be deemed “essentially a copy”.31 The legal and commercial significance of this prohibition cannot be overstated. It is the bright line that separates a 503B facility’s lawful operations from those of an unregistered drug manufacturer, and violating it carries the risk of FDA enforcement action and, as will be discussed, aggressive litigation from innovator companies.31

The Drug Shortage Safe Harbor: The Primary Pathway to On-Patent Compounding

While the “essentially a copy” prohibition is formidable, Congress and the FDA carved out a critical exception rooted in public health needs: a 503B outsourcing facility is permitted to compound a drug that is essentially a copy of an approved drug if that approved drug appears on the FDA’s official drug shortage list, maintained under Section 506E of the FD&C Act.17 This “drug shortage safe harbor” is the most significant and widely used legal pathway for 503B facilities to produce and sell products that are otherwise protected by active patents.

When a drug is in shortage, the FDA considers it to be not “commercially available,” thereby temporarily suspending the “essentially a copy” prohibition.35 This provision is a direct acknowledgment of the vital role 503B facilities can play in stabilizing the nation’s fragile drug supply chain.36 During a shortage, these facilities can leverage their cGMP-compliant infrastructure and bulk production capabilities to fill critical supply gaps, ensuring that hospitals and patients have access to essential medicines that would otherwise be unavailable.20

This safe harbor has given rise to a distinct and lucrative business model for many 503B facilities. However, it is a model fraught with volatility and operational challenges. The primary hurdle is the unpredictable nature of the FDA’s shortage list.37 A drug can be added to the list with little warning and, just as importantly, can be removed once the original manufacturer resolves its supply issues. This creates significant business risk for a 503B facility. It typically takes five to six weeks to source the necessary API, validate the compounding process, and ramp up production to meet demand.38 A facility might make a substantial investment to begin compounding a shortage drug, only for the shortage to be resolved shortly thereafter, leaving them with unsellable inventory and stranded costs.38

“The often short-term, unpredictable nature of FDA-declared drug shortages can disincentivize compounding of office stock to help health systems manage these situations.” 37

Furthermore, the FDA has made it clear that a manufacturer’s patent does not prohibit a 503B from compounding a drug on the shortage list, as the public interest in supplying the medication is paramount.33 However, once the drug is removed from the list, the safe harbor vanishes. The FDA has generally provided a 60-day grace period for 503B facilities to wind down production and distribute in-process batches, but after that period, any further compounding of the “copy” becomes unlawful.33 This dynamic creates a high-risk, high-reward environment where success depends on manufacturing agility, sophisticated supply chain management, and keen regulatory intelligence.

Litigation as a Business Strategy: How Brand-Name Pharma is Fighting Back

The unique legal status of 503B facilities has forced innovator drug companies to rewrite their IP defense playbook. Unable to rely on the automatic triggers and structured procedures of the Hatch-Waxman Act, brand manufacturers have pioneered new litigation strategies that leverage commercial law—specifically, claims of false advertising and unfair competition—to protect their market share. These lawsuits often use a 503B’s alleged non-compliance with FDA regulations as the very basis for the commercial tort claim. This strategic pivot has transformed the legal battlefield, making a 503B’s regulatory compliance program its most critical line of defense against IP-related challenges.

Case Study 1: Azurity Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Edge Pharma, LLC

A seminal case that established this new litigation model was Azurity Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Edge Pharma, LLC.31 Azurity markets FIRVANQ®, an FDA-approved oral solution of vancomycin. Edge Pharma, a registered 503B outsourcing facility, began compounding and selling its own oral vancomycin solution that was, by Azurity’s account, nearly identical to FIRVANQ®. Critically, FIRVANQ® was not on the FDA’s drug shortage list at the time.31

Azurity’s legal strategy was novel and instructive. It did not sue Edge for patent infringement, even though FIRVANQ® was protected by an Orange Book-listed patent.31 Instead, Azurity filed a lawsuit under the Lanham Act, the federal statute governing trademark and unfair competition, as well as a state consumer protection act.31 The core of Azurity’s argument was that by compounding a drug that was “essentially a copy” of an approved product not in shortage, Edge was in direct violation of Section 503B of the FD&C Act.

Azurity alleged that this regulatory violation formed the basis of a false advertising claim. By selling its product, Edge was implicitly—and, Azurity argued, explicitly—representing to its customers (hospitals and healthcare providers) that its product was lawfully compounded under federal law.31 Since the product was an unlawful “copy,” Azurity contended this representation was false and misleading, and that it constituted unfair competition by allowing Edge to improperly circumvent the rigorous and costly FDA approval process that Azurity had completed for FIRVANQ®.31

This case served as a roadmap for other innovator companies. It demonstrated that a 503B’s failure to adhere strictly to the conditions of the FDCA could be weaponized by a competitor in civil court, transforming a regulatory compliance issue into a commercial liability. The lawsuit highlighted that the fight was not just about patents, but about the fundamental legality of the 503B’s very presence in the market for a specific drug.

Case Study 2: The GLP-1 Battles (Semaglutide & Tirzepatide)

The strategic principles pioneered in the Azurity case have been deployed on a massive scale in the recent, high-profile conflicts over compounded GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide (the API in Ozempic® and Wegovy®) and tirzepatide (the API in Mounjaro® and Zepbound®). Due to unprecedented demand for their weight-loss indications, these drugs were placed on the FDA’s shortage list in 2022, opening the floodgates for 503B facilities to legally compound and sell their own versions.40 A booming market for compounded GLP-1s quickly emerged.41

The legal battles began in earnest when the manufacturers, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk, ramped up production and the FDA began removing the drugs from the shortage list in late 2024 and early 2025.42 This action dissolved the “safe harbor” for 503B compounders. The response from the industry and the manufacturers illustrates the modern legal landscape:

- Challenging the FDA: The Outsourcing Facilities Association (OFA), a trade group representing 503B facilities, took the extraordinary step of suing the FDA directly. The lawsuit argued that the FDA’s decision to remove tirzepatide from the shortage list was “arbitrary and capricious” and did not adequately consider ongoing regional supply disruptions, seeking to keep the compounding safe harbor open.40 While the courts ultimately denied the OFA’s motions for preliminary injunctions, the litigation itself represents a new front in the battle, where 503Bs are now proactively using administrative law to defend their market access.43

- Trademark and Unfair Competition Lawsuits: Concurrently, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk launched a wave of lawsuits against compounding pharmacies, medical spas, and wellness clinics. Crucially, like Azurity, these lawsuits did not primarily focus on patent infringement. Instead, they alleged trademark infringement, false advertising, and unfair competition.30 The complaints focused on defendants who used the well-known brand names “Mounjaro®” or “Ozempic®” in their advertising, creating what the manufacturers argued was a “likelihood of confusion” and misleading patients into believing they were receiving the genuine, FDA-approved products.30

These cases demonstrate a profound evolution in legal strategy. The central battleground for competition between brand manufacturers and 503B facilities is no longer patent law in isolation. The fight is now waged through the lens of commercial and administrative law, where a 503B’s adherence to the nuances of the FD&C Act is paramount. The logical chain is clear: if a 503B facility violates a provision of Section 503B—by, for example, compounding an “essential copy” of a drug not in shortage—a competitor can argue that the facility is making a false claim of legitimacy to the market. This transforms regulatory compliance from an internal operational matter into the primary shield against litigation from powerful, well-funded brand manufacturers. For executives and investors in the 503B space, this reality elevates the chief compliance officer and regulatory counsel to central roles in risk mitigation. An investment in a state-of-the-art cGMP quality system is simultaneously an investment in a robust legal defense strategy, yielding a return not only in product quality but in litigation avoidance.

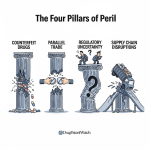

Strategic Pathways to Market: Innovative Models for 503B Success

The complex interplay of FDA regulations and intellectual property law creates a unique set of opportunities and challenges for 503B outsourcing facilities. Success in this sector requires more than just cGMP compliance; it demands a sophisticated and deliberate business strategy tailored to the specific legal pathways available. There are three primary strategic models that 503B facilities can pursue, each with a distinct risk profile, market opportunity, and potential return on investment (ROI).

Pathway 1: Mastering the Drug Shortage Market

The most direct and legally sanctioned pathway for a 503B facility to produce an on-patent drug is by capitalizing on the drug shortage safe harbor. This business model is centered on agility and regulatory intelligence, positioning the facility as a crucial partner to healthcare systems during supply chain crises.

Strategy: The core strategy involves developing the operational capacity to rapidly pivot and begin production of drugs as soon as they appear on the FDA’s 506E shortage list.34 Success requires a proactive approach. Facilities must maintain a “watch list” of critical sterile drugs prone to shortages, such as IV antibiotics, emergency syringes, and parenteral nutrition products.39 For these high-risk candidates, the 503B should pre-emptively establish relationships with API suppliers, develop and validate compounding and testing protocols, and prepare the necessary documentation. This preparation allows them to slash the typical five-to-six-week ramp-up time and be among the first to market when a shortage is declared.36 Furthermore, building deep relationships with hospital systems and Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) allows a 503B to secure volume commitments, mitigating the risk of a sudden resolution to the shortage.36

ROI Analysis:

- Investment (-): The primary costs include sourcing often-expensive API, dedicating cGMP-compliant manufacturing capacity, and the significant expense of batch validation, including sterility, potency, and endotoxin testing for every lot. There is also a substantial investment in regulatory monitoring and intelligence.

- Return (+): The return is driven by the ability to command premium pricing for a product that is otherwise unavailable. By providing a stable supply, 503Bs enable hospitals to maintain standards of care and avoid the high labor costs associated with managing shortages, which were estimated at $360 million annually in a 2019 report.45 This value capture can lead to very high margins during the shortage period.

- Risk Factors (x): The ROI is heavily discounted by significant risks. The primary risk is the unpredictable duration of the shortage.37 A manufacturer could resolve its production issues at any time, leading the FDA to remove the drug from the 506E list and stranding the 503B’s investment. Competition is also a factor, as multiple 503B facilities may target the same high-value shortage drug, compressing margins.

Pathway 2: The “Clinically Different” Formulation Strategy

This pathway represents the frontier of 503B innovation, but it is also the most legally perilous. It involves creating a product that is intentionally similar to a patented, approved drug but is modified in a way that is argued to be “clinically different” for certain patients, thereby avoiding the “essentially a copy” prohibition.

Strategy: This strategy hinges on the narrow exception in the FD&C Act which states that a compounded drug is not considered a “copy” if a change is made that a prescriber determines will produce a “significant difference” for an individual patient.17 503B facilities pursuing this model focus on identifying and validating unmet clinical needs that the commercial product does not address. Common strategies include:

- Preservative-Free Formulations: Developing versions of injectable drugs without preservatives for patients with known allergies or sensitivities to excipients like benzyl alcohol.

- Alternative Concentrations: Compounding a drug at a higher or lower concentration than is commercially available to meet the needs of specific patient populations (e.g., pediatric or geriatric patients).

- Novel Combinations: Combining two or more compatible, off-patent APIs into a single sterile preparation (e.g., a multi-drug cardioplegia solution) to simplify administration in a surgical setting.

Legal & Regulatory Hurdles: This is an exceptionally high-risk path that attracts intense scrutiny. The FDA’s position is that the determination of a “clinical difference” must be made by a prescribing practitioner for an individual patient.46 This creates a high documentation burden for the 503B, which must be able to demonstrate that its bulk production is in anticipation of prescriptions where this specific clinical need is documented. Brand manufacturers are highly likely to challenge such products in court, arguing that the alleged “clinical difference” is pretextual and that the product is, in fact, an infringing “essential copy” designed to erode their market share. Success requires not only sophisticated formulation science but also an ironclad legal and regulatory strategy.

ROI Analysis:

- Investment (-): Significant R&D investment is required to develop and validate the new formulation, including extensive stability and compatibility testing. Legal costs for a thorough Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis and potential litigation defense are also substantial.

- Return (+): If successful, the return can be enormous. A “clinically different” product can carve out a durable, high-margin niche in a market otherwise dominated by a patented drug. It creates a proprietary product that other 503Bs cannot easily replicate, leading to a strong competitive advantage.

- Risk Factors (x): The risk of failure is extremely high. The product could be deemed an “essential copy” by the FDA, leading to enforcement action. More likely, it will trigger an aggressive and costly unfair competition lawsuit from the brand manufacturer, as seen in the Azurity case. The potential for a court-ordered injunction that halts all sales represents an existential threat.

Pathway 3: Dominating the Off-Patent Space

The most stable, lowest-risk, and arguably largest long-term business model for 503B facilities is to focus on the production of off-patent sterile drugs.18 This strategy avoids direct patent conflicts and instead leverages the 503B’s core value proposition—cGMP quality—to compete in the established market for generic injectables.

Strategy: The goal is to become the preferred cGMP-compliant supplier of high-quality, ready-to-use sterile preparations for hospital and clinic office stock. These are typically older, generic drugs that are nonetheless critical for patient care (e.g., vasopressors, local anesthetics, electrolytes). The 503B competes not against patented innovator drugs, but against other 503Bs and traditional generic manufacturers. The competitive advantages a 503B can offer include superior quality assurance, longer BUDs than hospital-compounded preparations (reducing waste), and convenient, ready-to-administer dosage forms (e.g., pre-filled syringes) that improve workflow efficiency and patient safety in clinical settings.47

The 503B-to-503A Channel: A New Frontier in Distribution

A significant new opportunity within this pathway emerged with the FDA’s June 2023 draft guidance, which sanctions a 503B-to-503A distribution model.33 This guidance permits 503B facilities to compound medications and sell them as “office stock” to 503A community pharmacies, which can then dispense them to individual patients pursuant to a valid prescription.33 This opens a vast new channel to the retail market, allowing 503A pharmacies to offer high-quality, cGMP-produced sterile compounds without needing to build and maintain their own expensive sterile compounding facilities. However, this model is not without complexity, as some states, such as New Jersey and Idaho, currently prohibit this sales channel, requiring 503Bs to navigate a patchwork of state-level regulations.48

ROI Analysis:

- Investment (-): The primary investment is in manufacturing efficiency, quality systems, and sales and marketing to build relationships with healthcare systems and 503A pharmacies.

- Return (+): The return is generated through high-volume sales in a large, stable market. While per-unit margins may be lower than for shortage or “clinically different” drugs, revenue is more predictable and sustainable. The 503B-to-503A model dramatically expands the potential customer base.

- Risk Factors (x): The primary risk is market competition. This space is highly fragmented, with numerous 503B facilities competing for contracts from GPOs and large health systems.49 Success depends on achieving economies of scale and differentiating on quality, customer service, and reliability.

The strategic choice between these pathways will define a 503B facility’s future. The following table provides a high-level comparison to aid in this critical decision-making process.

| Strategic Pathway | Description | Primary IP/Regulatory Risk | Market Opportunity | ROI Profile |

| Drug Shortage Compounding | Rapidly producing copies of patented drugs that appear on the FDA’s 506E shortage list. | High risk of the shortage ending abruptly, stranding investment. Low direct litigation risk while on the list. | High-margin but volatile and unpredictable. Opportunity is tied to supply chain failures. | High-Risk / High-Reward |

| “Clinically Different” Formulation | Developing modified versions of patented drugs to meet specific, documented clinical needs not addressed by the commercial product. | Extremely high risk of “essential copy” determination by FDA and unfair competition litigation from brand manufacturers. | Potential to create a durable, proprietary, high-margin niche within a protected market. | Very High-Risk / Very High-Reward |

| Off-Patent Dominance | Focusing on high-volume, cGMP-quality production of off-patent sterile drugs for hospital and clinic office use. | Low patent risk. Primary risk is intense market competition from other 503Bs and generic manufacturers. | Large, stable, and growing market driven by demand for quality and efficiency. Includes the emerging 503B-to-503A channel. | Lower-Risk / Stable, Long-Term Return |

The Modern Arsenal: Tools for Strategic Decision-Making

Executing any of the strategic pathways outlined requires more than just capital and manufacturing capability. In the high-stakes environment of pharmaceutical compounding, where regulatory and intellectual property risks are immense, success depends on a sophisticated arsenal of analytical tools and processes. Two of the most critical components of this arsenal are a rigorous Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis process and the strategic use of competitive intelligence platforms. These tools are not optional expenses; they are essential investments for de-risking innovation and making informed, data-driven decisions.

De-Risking Innovation: The Critical Role of Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis

A Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is a formal legal assessment conducted to determine whether a proposed commercial product or process can be developed and marketed without infringing on the valid intellectual property rights of others.50 For a 503B facility, particularly one considering the high-risk “clinically different” formulation strategy, conducting a thorough FTO analysis is a non-negotiable prerequisite. While not legally required, obtaining a formal FTO opinion from qualified IP counsel serves two vital business functions: it minimizes the risk of costly patent litigation, and it can shield the company from findings of “willful infringement,” which can lead to treble damages in a lawsuit.50

The FTO process for a 503B facility is a systematic, multi-step investigation:

- Product Definition: The process begins with a precise and detailed definition of the proposed compounded product. This includes the specific API(s), all excipients and their concentrations, the final dosage form and strength, the method of manufacturing, and the intended clinical use. Every element must be clearly defined, as any could be the subject of a patent claim.

- Comprehensive Patent Searching: Legal counsel and patent specialists conduct exhaustive searches of issued patents and published patent applications in relevant jurisdictions (primarily the U.S.). This search is not limited to patents listed in the Orange Book; it must include all patents that could potentially cover any aspect of the product, including formulation, manufacturing processes, or methods of use.50

- Risk Assessment and Legal Analysis: Each identified patent is meticulously analyzed. The legal team construes the patent’s claims—the legally binding sentences that define the scope of the invention—and compares them to the proposed 503B product. This analysis assesses the likelihood that the proposed product would be found to infringe on the patent’s claims. Patents are categorized by risk level (e.g., low, medium, high) to prioritize strategic focus.50 For high-risk patents, the analysis may extend to evaluating the patent’s validity, searching for prior art that could potentially invalidate it.

- Strategic Decision-Making: The results of the FTO analysis inform a critical business decision.

- Green Light: If the analysis concludes that the risk of infringement is low, the company can proceed with development and commercialization with a higher degree of confidence.

- “Design Around”: If the analysis identifies specific blocking patents, the R&D team can use this information to modify the product’s formulation or manufacturing process to avoid the patented claims. For example, if a patent claims a formulation stabilized with excipient A, the team can innovate to create a stable formulation using non-infringing excipient B.50

- Licensing or Abandonment: If a high-risk patent cannot be designed around or invalidated, the company may choose to approach the patent holder to negotiate a license. If that is not feasible, the most prudent decision may be to abandon the project to avoid a high probability of litigation.

By integrating FTO analysis early in the product development lifecycle, a 503B facility can proactively manage IP risk, allocate R&D resources more effectively, and provide crucial assurance to investors and partners that it has a clear and legally defensible path to market.

Competitive Intelligence with DrugPatentWatch

In today’s data-driven pharmaceutical market, strategic decision-making cannot be based on intuition alone. It requires robust, timely, and accurate competitive intelligence. For 503B outsourcing facilities, a specialized platform like DrugPatentWatch is an indispensable tool for identifying opportunities, assessing risks, and formulating strategy across all business models.51 This platform aggregates and synthesizes vast amounts of data from primary sources—including the FDA and global patent offices—into an actionable intelligence dashboard.51

The utility of DrugPatentWatch can be mapped directly to the strategic pathways available to 503B facilities:

- For the Off-Patent Dominance Model: The platform is a powerful engine for pipeline development. A 503B can use it to build a comprehensive timeline of patent and exclusivity expirations for high-value sterile drugs.25 By setting up automated alerts for Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) events, the business development team can precisely time their R&D and market entry strategies to launch a compounded version as soon as the last relevant patent expires, maximizing their first-mover advantage in the off-patent space.51 The platform also helps identify API suppliers, a critical step in securing the supply chain for a new product launch.51

- For the “Clinically Different” Formulation Model: This is where the deep analytical capabilities of a patent intelligence platform become crucial. To “design around” a patented product, a 503B’s R&D team must first understand exactly what is protected. DrugPatentWatch allows users to “crack the code” of competitor formulation patents.52 By analyzing the detailed descriptions and, most importantly, the legal claims of formulation patents, scientists can identify the specific excipients, concentrations, or manufacturing processes that are protected. This reveals the “white space”—the unprotected territory where a novel, non-infringing formulation can be developed. Studying prior claims and litigation history related to a patent can further strengthen the development of a legally resilient new formulation.51

- For the Drug Shortage Model and General Market Intelligence: The platform serves as a vital tool for risk management and opportunity spotting. Users can monitor FDA drug shortage lists, a key service for a business model that relies on these declarations.53 Furthermore, tracking litigation across the industry can provide early warnings of new legal strategies being deployed by brand manufacturers or reveal vulnerabilities in a competitor’s patent portfolio.51 The platform’s AI Research Assistant can be leveraged to quickly synthesize information from disparate sources—such as clinical trial data, regulatory filings, and patent documents—to build a comprehensive picture of the competitive landscape for a potential product.51

By integrating a powerful competitive intelligence tool like DrugPatentWatch into their strategic planning process, 503B facilities can move from a reactive to a proactive posture. They can make data-driven decisions about which products to pursue, how to design them to minimize legal risk, and when to enter the market for maximum impact, turning information into a tangible competitive advantage.

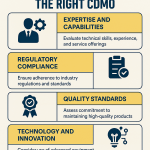

The Future of 503B Compounding: Trends, Challenges, and Predictions

The 503B outsourcing facility sector, born just over a decade ago, is rapidly evolving from a niche solution into an integral and increasingly scrutinized component of the U.S. healthcare system. The future of this industry will be shaped by the convergence of three powerful forces: a tightening regulatory environment, dynamic market pressures driving consolidation and technological adoption, and the enduring tension between the need for compounded drugs and the protection of intellectual property. Stakeholders must anticipate these trends to navigate the challenges and capitalize on the opportunities that lie ahead.

The Regulatory Horizon: Increased FDA Scrutiny and Evolving Guidance

The era of regulatory ambiguity in large-scale compounding is over. The clear and consistent trend is toward increased and more stringent FDA oversight of 503B facilities. This reflects the agency’s mandate to protect public health and ensure that compounded drugs are used appropriately, serving as a supplement to, not a substitute for, the FDA-approved drug supply.

A key development signaling this trend is the FDA’s March 2024 proposed rule to establish “Demonstrably Difficult to Compound” (DDC) lists.54 This proposal would create lists of drug products or entire categories of drugs that the FDA deems too complex to be compounded safely and effectively outside of a traditional manufacturing environment. The initial proposal includes categories such as liposome drug products and oral solid modified-release drugs that use coated systems.54 If finalized, this rule would prohibit 503B facilities from compounding any drug on the DDC list, regardless of its shortage status.55 This represents a significant potential limitation on the scope of 503B operations and signals the FDA’s willingness to draw firm lines around what it considers appropriate for compounding.

Simultaneously, the regulatory landscape is being actively shaped by legal challenges from the industry itself. The recent lawsuits filed by the Outsourcing Facilities Association (OFA) against the FDA concerning the removal of GLP-1 drugs from the shortage list are indicative of a new, more confrontational dynamic.42 These cases, while unsuccessful in obtaining injunctions, demonstrate the industry’s readiness to use administrative law to contest FDA decisions that impact its commercial interests. The future will likely see continued legal battles over the interpretation of Section 503B, the criteria for the drug shortage list, and the scope of the FDA’s enforcement discretion. For 503B facilities, this means that staying compliant is no longer enough; they must also stay abreast of a legal and regulatory environment that is in a constant state of flux.

Market Dynamics: Consolidation, Technology, and Economic Pressures

The 503B market is entering a new phase of maturity, characterized by strong growth, increasing consolidation, and the adoption of advanced technologies. These market dynamics will reshape the competitive landscape and raise the bar for success.

Market Growth: The demand for high-quality compounded sterile preparations remains robust. Market research projects that the U.S. 503B compounding pharmacies market will grow from approximately $1.16 billion in 2024 to over $2.25 billion by 2033, expanding at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 7.6%.47 This growth is fueled by several factors, including the persistent problem of drug shortages, the rising demand for personalized medicine, and the increasing reliance of hospitals and outpatient clinics on outsourcing to ensure a reliable supply of ready-to-administer medications.49

Consolidation: As the market grows, it is also consolidating. The industry, once highly fragmented, is seeing a wave of mergers and acquisitions as larger players seek to expand their geographic footprint and product portfolios.49 For example, Revelation Pharma, a national network of compounding pharmacies, has been actively acquiring both 503A and 503B facilities to build a national presence.58 This trend is expected to continue, as the high capital costs of cGMP compliance and the increasing complexity of regulation create significant advantages for larger, well-capitalized organizations. Smaller, independent 503B facilities may find it increasingly difficult to compete, leading to further acquisitions or market exits.

Technology Adoption: To meet the demands of cGMP compliance and improve efficiency, leading 503B facilities are increasingly investing in advanced technology. Automation and robotic systems are being deployed in cleanrooms to perform repetitive tasks like filling and capping vials and syringes, which reduces the risk of human error and microbial contamination.47 Digital quality management systems and AI-powered analytics are being used to streamline documentation, monitor environmental conditions in real-time, and predict potential quality deviations before they occur.47 This technological arms race will further separate the market leaders from the laggards, making investment in innovation a prerequisite for long-term viability.

The Enduring Tension: Balancing Access, Safety, and Intellectual Property

Looking ahead, the 503B outsourcing facility sector will continue to be defined by the inherent tension between three critical imperatives: the public health need for access to essential medications, the FDA’s mandate to ensure safety and quality, and the legal and economic importance of protecting the intellectual property that fuels pharmaceutical innovation. 503B facilities are positioned directly at the center of this complex triad.

They have proven themselves to be an indispensable part of the healthcare ecosystem. As Shawn Hodges, CEO of Revelation Pharma, has noted, during periods of supply chain disruption, “There are opportunities in certain instances where compounding pharmacies can fill the void until the manufacturers are able to produce the products”.60 This role in mitigating drug shortages is no longer theoretical; it is a proven capability that hospitals and regulators now rely upon.

However, this vital function must be balanced against the fact that compounded drugs do not undergo the same rigorous premarket review for safety and efficacy as FDA-approved drugs.63 As Shaun Noorian, CEO of Empower Pharmacy, acknowledges, the industry must constantly work to overcome misconceptions about safety by adhering to the strictest quality standards and regulations imposed by the FDA and state boards.64 The future will bring even greater pressure to demonstrate quality and compliance, as the FDA continues to tighten its oversight.

Finally, the industry must navigate the legitimate intellectual property rights of innovator companies. While the drug shortage safe harbor provides a clear, albeit temporary, pathway, the pursuit of “clinically different” formulations will remain a legal battleground. As Kurt Lunkwitz, COO of ProRx Pharma, suggests, the industry must “innovate with purpose” and redefine its role, not as a shortcut around the patent system, but as a strategic partner in the healthcare supply chain that can mitigate gaps and meet specialized needs.66

The future of 503B compounding will be forged in the crucible of these competing interests. The most successful facilities will be those that can master this delicate balancing act: demonstrating an unwavering commitment to cGMP quality and patient safety, operating with the agility to respond to public health needs like drug shortages, and pursuing innovation with a sophisticated and respectful understanding of the intellectual property landscape.

Key Takeaways

- 503B Facilities Are a Unique, Federally Regulated Entity: Created by the DQSA in response to a public health crisis, 503B outsourcing facilities operate under direct FDA oversight and must comply with the same cGMP quality standards as major pharmaceutical manufacturers. This distinguishes them from state-regulated 503A pharmacies and enables their role in bulk sterile compounding.

- The Legal Battleground Has Shifted from Patent to Commercial Law: Because 503Bs operate outside the traditional Hatch-Waxman framework, brand manufacturers have pivoted their legal strategy. The primary threat to a 503B is not a direct patent infringement lawsuit, but rather an unfair competition or false advertising claim under the Lanham Act, which uses alleged non-compliance with FDA regulations (like the “essentially a copy” rule) as its foundation.

- Regulatory Compliance is the Ultimate Legal Shield: In this new legal paradigm, a 503B’s most effective defense against IP-related litigation is a robust and meticulously documented regulatory compliance program. Investment in cGMP quality systems provides a return not only in product safety and market access but also in litigation avoidance.

- Three Distinct Strategic Pathways Exist, Each with a Unique Risk/Reward Profile:

- Drug Shortages: A high-risk, high-reward model based on manufacturing agility and regulatory intelligence.

- “Clinically Different” Formulations: A very high-risk, very high-reward innovation strategy that invites intense legal and regulatory scrutiny.

- Off-Patent Dominance: A lower-risk, stable model focused on becoming a high-quality supplier of generic sterile drugs, representing the largest and most sustainable long-term market.

- Competitive Intelligence and FTO Analysis Are Non-Negotiable: Success in the 503B space requires data-driven decision-making. A thorough Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is essential before launching any new product that could face IP challenges. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are critical tools for identifying off-patent opportunities, analyzing competitor patents for “design around” strategies, and monitoring the litigation and regulatory landscape.

- The Future is Defined by Stricter Regulation and Market Consolidation: The FDA is signaling a move toward tighter control, with proposals like the “Demonstrably Difficult to Compound” lists potentially narrowing the scope of 503B operations. Concurrently, the market is maturing, leading to consolidation as larger, well-capitalized players with advanced technology acquire smaller competitors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is it legal for a 503B facility to compound a patented drug?

It can be, but only under specific, legally defined circumstances. The general rule under Section 503B is that a facility cannot produce a drug that is “essentially a copy” of an FDA-approved product. However, there are two major exceptions. First, if the FDA-approved drug is on the official drug shortage list (Section 506E), a 503B facility is legally permitted to compound a copy to alleviate the shortage. Second, a 503B may be able to compound a modified version of a patented drug if a prescriber determines the change produces a “clinical difference” for a specific patient. This second pathway is legally complex and carries a very high risk of litigation from the patent holder.

2. What is the biggest legal risk for a 503B facility today: patent infringement or FDA non-compliance?

The biggest legal risk is FDA non-compliance, precisely because it has become the primary basis for intellectual property challenges. Recent litigation trends show that brand manufacturers are increasingly successful in suing 503B facilities for unfair competition and false advertising. Their argument is that by failing to comply with FDA regulations (e.g., by making an “essential copy” of a drug not in shortage), the 503B is falsely representing its product as lawful, thereby misleading customers and unfairly competing. This makes a robust compliance program the best defense against what are effectively IP-driven lawsuits.

3. How can our company identify viable product opportunities for our 503B pipeline?

Identifying opportunities requires a strategy aligned with one of the three primary business models. For the most stable, long-term growth, focus on the off-patent market. Use tools like DrugPatentWatch to build a pipeline of high-value sterile drugs with upcoming patent expirations. For the higher-risk, higher-reward drug shortage model, use market intelligence to identify drugs with fragile supply chains that are likely candidates for future shortages. For the highest-risk “clinically different” model, use patent databases to analyze the formulation claims of existing products to identify potential “design around” opportunities that could offer a genuine clinical benefit.

4. What is the ROI on building a cGMP-compliant 503B facility?

The return on investment for a 503B facility is driven by its unique market position. While the upfront capital costs for building and validating a cGMP-compliant facility are substantial, this investment unlocks access to the lucrative hospital and clinic “office use” market, which is inaccessible to 503A pharmacies. The ROI comes from the ability to produce in bulk, command premium pricing for high-quality, reliable sterile products with extended beyond-use dates, and capitalize on high-margin opportunities during drug shortages. In essence, cGMP compliance is not just a cost center; it is the competitive advantage and legal shield that generates the return.

5. How is the FDA’s increasing scrutiny likely to change the 503B market in the next five years?

The FDA’s increasing scrutiny will likely lead to two major shifts. First, the regulatory bar will get higher. Proposals like the “Demonstrably Difficult to Compound” (DDC) lists could remove entire categories of complex drugs from the scope of 503B compounding, narrowing the market for some. Second, the rising cost and complexity of compliance will accelerate market consolidation. Smaller facilities that cannot afford the continuous investment in technology and quality systems may be acquired by larger, multi-state operators or be forced to exit the market. The result will be a more mature, albeit smaller, group of highly sophisticated 503B players.

Works cited

- Information for Outsourcing Facilities | FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/information-outsourcing-facilities

- Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) in 503B Outsourcing – Fagron Sterile Services, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fagronsterile.com/newsroom/cgmp-503b-outsourcing

- History of 503B Outsourcing Facilities – Fagron Sterile Services, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fagronsterile.com/newsroom/history-of-503b-outsourcing-facilities

- www.fda.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters#:~:text=The%20%22Drug%20Price%20Competition%20and,Drug%2C%20and%20Cosmetic%20Act%20(FD%26C

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Facility Definition Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act Guidance for Industry – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/97359/download

- IP & FDA Challenges Related to Pharmaceutical Compounding of Human and Animal Drugs, accessed August 18, 2025, https://ipfdalaw.com/ip-fda-challenges-related-to-pharmaceutical-compounding-of-human-and-animal-drugs/

- Drug Quality & Security Act Webinar Handout – ASHP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-centers/sterile-compounding/drug-quality-security-act-webinar-handout.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Outsourcing Facility Licensing – Harbor Compliance, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.harborcompliance.com/pharmaceutical-outsourcing-facility-license

- Compounded Drug Products That Are Essentially Copies of Approved Drug Products Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/98964/download

- ASHP Guidelines on Outsourcing Sterile Compounding Services, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/Outsourcing-Compounding-Services

- Compounding Inspections and Oversight Frequently Asked Questions – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/compounding-inspections-and-oversight-frequently-asked-questions

- 503A vs. 503B: A Quick-Guide to Compounding Pharmacy Designations & Regulations, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/503a-vs-503b-compounding-pharmacies

- 503A or 503B—Knowing When to Order from Each One – Epicur Pharma®, accessed August 18, 2025, https://epicurpharma.com/2021/09/24/503a-or-503b-knowing-when-to-order-from-each-one/

- 503A vs. 503B Pharmacies – Olympia Pharmaceuticals, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.olympiapharmacy.com/compounding-503a-vs-503b/

- 503A Vs. 503B Compounding Pharmacies: Similarities & Differences, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fagronsterile.com/newsroom/503a-vs-503b-compounding-pharmacies

- Regulatory Framework for Compounded Preparations – The Clinical Utility of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy – NCBI, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562888/

- The Viability of a Compounding Pharmacy Patent Exception in the United States, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/health_law/resources/esource/archive/viability-compounding-pharmacy-patent-exception-united-states/

- 503B Compounding Pharmacy Cleanrooms | USP 797/800 & FDA Compliance, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.gconbio.com/503b-compounding-pharmacy/

- How Does 503B Compliance Benefit the Public? – Premier Inc., accessed August 18, 2025, https://premierinc.com/newsroom/premier-in-the-news/how-does-503b-compliance-benefit-the-public

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Drug Patents: How Pharmaceutical IP Incentivizes Innovation and Affects Pricing, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.als.net/news/drug-patents/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary Magazine, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- Patent Listing in FDA’s Orange Book – Congress.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12644

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 18, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- The Listing of Patent Information in the Orange Book – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/155200/download

- Intellectual Property Challenges for 503A Pharmacy Compounding – Frier Levitt, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.frierlevitt.com/articles/intellectual-property-challenges-for-503a-pharmacy-compounding/

- Pioneer Drug Maker Throws First Punch at Pharmacy Outsourcing Facilities (503Bs), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.troutman.com/insights/pioneer-drug-maker-throws-first-punch-at-pharmacy-outsourcing-facilities-503bs.html

- An Exploration of Compounding Practices – Pharmaceutical Commerce, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/an-exploration-of-compounding-practices

- Regulatory Considerations Regarding the 503B to 503A Compounding Model For Community Pharmacies, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/regulatory-considerations-regarding-the-503b-to-503a-compounding-model-for-community-pharmacies

- Pharmacy Attorneys For Outsourcing Facilities (503b) – Frier Levitt, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.frierlevitt.com/who-we-serve/life-sciences/outsourcing-facilities-503b/

- Allowing Compounding Pharmacies to Address Drug Shortages – Mercatus Center, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/broughel_-_policy_brief_-_drug_shortages_and_compounding_pharmacies_-_v1.pdf

- 503B Facilities Help Address Drug Shortages – Premier Inc., accessed August 18, 2025, https://premierinc.com/newsroom/premier-in-the-news/503b-facilities-help-address-drug-shortages

- Market for Compounded Drugs Needs Greater Transparency and Regulatory Certainty, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/06/market-for-compounded-drugs-needs-greater-transparency-and-regulatory-certainty

- 001: Drug Shortages: A Conversation with Erin R. Fox, Pharm.D., BCPS, FASHP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/Professional-Development/ASHP-Podcasts/Advocacy-Updates/Drug-Shortages

- ASHP Drug Shortages Roundtable Report, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/shortage-resources/roundtable-report

- Compounding and GLP-1s: What To Expect When GLP-1 Drugs Are Removed From FDA’s Drug Shortage List | Insights | Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2024/12/compounding-and-glp1s-what-to-expect

- FDA Regulatory Failures in Enforcing Limits on GLP-1 Compounding Puts Patients at Risk, accessed August 18, 2025, https://publichealth.realclearjournals.org/research-articles/2025/08/fda-regulatory-failures-in-enforcing-limits-on-glp-1-compounding-puts-patients-at-risk/

- Compounding Problems: Recent Decisions on Tirzepatide Highlight Interplay Between FDA Anti-Compounding Enforcement and Private Intellectual Property Rights | Axinn, Veltrop & Harkrider LLP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.axinn.com/en/insights/axinn-viewpoints/compounding-problems-recent-decisions-on-tirzepatide-highlight-interplay-between

- FDA clarifies policies for compounders as national GLP-1 supply begins to stabilize, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-clarifies-policies-compounders-national-glp-1-supply-begins-stabilize

- Navigating Litigation and Intellectual Property in 503A Compounding – Frier Levitt, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.frierlevitt.com/articles/navigating-litigation-and-intellectual-property-in-503a-compounding/

- How Should We Draw on Pharmacists’ Expertise to Manage Drug Shortages in Hospitals?, accessed August 18, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/how-should-we-draw-pharmacists-expertise-manage-drug-shortages-hospitals/2024-04

- Transcript of Conference Call on the Legal Landscape for GLP-1 Compounding with Shweta Kumar – The Capitol Forum, accessed August 18, 2025, https://thecapitolforum.com/resources/transcript-legal-landscape-glp-1-compounding-shweta-kumar/

- 503B Compounding Pharmacies Market Size | 7.63% CAGR By 2033 – Towards Healthcare, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.towardshealthcare.com/insights/503b-compounding-pharmacies-market-sizing

- Considerations for the 503B-to-503A-to-Patient Compounding Model, accessed August 18, 2025, https://restorehealthconsulting.squarespace.com/news/considerations-for-the-503b-to-503a-to-patient-compounding-model

- 503B Compounding Pharmacies Market Trends and Insights, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.datainsightsmarket.com/reports/503b-compounding-pharmacies-333795

- Freedom to Operate Opinions: What Are They, and Why Are They Important? | Intellectual Property Law Client Alert – Dickinson Wright, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.dickinson-wright.com/news-alerts/arndt-freedom-to-operate-opinions

- DrugPatentWatch has been a game-changer for our business, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- Cracking the Code: Using Drug Patents to Reveal Competitor …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/cracking-the-code-using-drug-patents-to-reveal-competitor-formulation-strategies/

- Navigating Complex Regulatory Environments in … – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/navigating-complex-regulatory-environments-in-drug-portfolio-management/

- FDA Publishes Proposed Rule on 503A and 503B Compounding – McDermott Will & Emery, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mwe.com/insights/fda-publishes-proposed-rule-on-sections-503a-and-503b-compounding/

- FDA announces proposed rule for drug products deemed difficult to compound under sections 503A and 503B of the FDCA | Perspectives | Reed Smith LLP, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.reedsmith.com/en/perspectives/2024/03/fda-announces-proposed-rule-for-drug-products-deemed-difficult-to-compound

- Navigating the Evolving World of Drug Compounding – Avalere Health Advisory, accessed August 18, 2025, https://advisory.avalerehealth.com/insights/navigating-the-evolving-world-of-drug-compounding

- FDA’s Removal of Semaglutide and the Evolving Tirzepatide Decisions: What Compounders Need to Know | Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney PC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.bipc.com/fdas-removal-of-semaglutide-and-the-evolving-tirzepatide-decisions-what-compounders-need-to-know

- U.S. 503B Compounding Pharmacies Market Size to Capture $2.25 Billion by 2033, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/press-releases/u-s-503b-compounding-pharmacies-market-size-to-capture-2-25-billion-by-2033

- U.S. 503B Compounding Pharmacies Market Grows at 7.63% CAGR by 2034, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.towardshealthcare.com/insights/us-503b-compounding-pharmacies-market-sizing

- Revelation Pharma – Lee Silsby Compounding Pharmacy, accessed August 18, 2025, https://leesilsby.com/blog/category/revelation-pharma

- U.S. 503B Compounding Pharmacy Packaging Market Insights for 2034, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.towardspackaging.com/insights/us-503b-compounding-pharmacy-packaging-market-sizing

- 2024 Top Trends for 503B Compounding Pharmacies | Pioneering Diagnostics – bioMerieux, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.biomerieux.com/us/en/education/resource-hub/scientific-library/pharma-microorganisms-library/2024-top-trends-for-503b-compounding-pharmacies.html

- Drug Compounding: FDA Authority and Possible Issues for Congress, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45069

- Compounding Personalized Healthcare: Shaun Noorian Interviews with Mark Bishop, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.empowerpharmacy.com/compound-medication/news/empower-pharmacy-compounding-personalized-healthcare/

- Dr. Mark Hyman and Shaun Noorian Talk Compounding – Empower Pharmacy, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.empowerpharmacy.com/compound-medication/empower-news/dr-mark-hyman-and-shaun-noorian-talk-compounding/

- Q&A with Kurt Lunkwitz, Chief Operating Officer of ProRx Pharma | citybiz, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.citybiz.co/article/675486/qa-with-kurt-lunkwitz-chief-operating-officer-of-prorx-pharma/