Executive Summary

The expiration of a drug’s patent is one of the most predictable and disruptive events in the pharmaceutical industry, triggering a precipitous decline in revenue for the innovator company known as the “patent cliff.” While this event is often viewed as an endpoint to a drug’s premium commercial life, this report posits that it is, in fact, a powerful beginning—a strategic inflection point that creates a unique and underexploited opportunity for academic research institutions to drive medical innovation. This “post-patent dividend” unlocks a wealth of established therapeutic compounds for systematic investigation into new medical uses, a process known as drug repositioning or repurposing. The expiration of market exclusivity acts as a powerful catalyst through three primary mechanisms: economic, by dramatically reducing drug acquisition costs for research; scientific, by providing access to decades of invaluable human safety and pharmacokinetic data; and legal, by lowering intellectual property barriers to investigation.

This report provides a comprehensive strategic framework for academic, governmental, and non-profit stakeholders to harness this opportunity. It begins by deconstructing the post-exclusivity pharmaceutical landscape, detailing the market dynamics of patent cliffs, generic entry, and the complex web of regulatory exclusivities that define a drug’s true availability. It then establishes the strategic imperative of drug repositioning, contrasting its de-risked, cost-effective, and accelerated development timeline with the formidable challenges of de novo drug discovery. The analysis demonstrates that the core competencies of academic research—deep expertise in disease biology, a focus on fundamental mechanisms, and a mission to address unmet needs in rare and neglected diseases—are uniquely aligned with the knowledge-intensive demands of drug repositioning.

A practical framework is presented for academic institutions to systematically identify and pursue these opportunities, integrating the use of critical public databases such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Orange Book, ClinicalTrials.gov, and PubMed. This is supported by in-depth case studies of iconic repurposed drugs—sildenafil, thalidomide, metformin, and raloxifene—that illustrate distinct and repeatable archetypes of academic-led discovery. Finally, the report examines the ecosystem required to support these initiatives, including the roles of government funding bodies like the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), philanthropic organizations, and university technology transfer offices. It concludes with a set of actionable recommendations for stakeholders to build a more robust and efficient pipeline for academic drug repositioning, positioning universities not merely as sources of basic science but as central engines in a new paradigm of translational research powered by the untapped potential of existing medicines.

I. The Post-Exclusivity Pharmaceutical Landscape: An Opportunity for Innovation

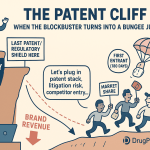

The lifecycle of a pharmaceutical product is defined by a period of legally protected market monopoly, followed by an abrupt transition into a competitive commodity market. This transition, triggered by the expiration of patents and other regulatory exclusivities, is not a gradual decline but a seismic shift with profound economic and strategic implications. Understanding the mechanics of this “patent cliff” is the first step in recognizing it not as a threat to be managed by industry, but as a predictable, recurring opportunity that can be systematically leveraged by the academic research community to advance public health.

1.1 Deconstructing the Patent Cliff: Market Dynamics After Loss of Exclusivity

The foundation of pharmaceutical innovation is the patent system, which grants an inventor a temporary monopoly to recoup the immense costs of research and development (R&D).1 A drug patent in the United States typically provides 20 years of protection from the date the application is filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).3 However, this 20-year term is profoundly misleading in practice. Patents are generally filed early in the development process, often years before a drug completes the rigorous preclinical and clinical trials required for regulatory approval.3 This protracted development timeline, which can span 10 to 15 years, significantly erodes the effective commercial life of a patent.6 Consequently, the actual period of market exclusivity—the time from FDA approval to the first generic competition—is typically much shorter, averaging between 7 and 12 years.2

This finite period of exclusivity culminates in the “patent cliff,” a term used across the industry to describe the sudden and dramatic loss of revenue that occurs when a blockbuster drug’s patents expire, opening the market to generic competitors.3 This is not a gentle slope but a sheer drop; innovator companies often see revenue from their flagship products decline by 80-90% within the first year of generic entry.3 The scale of this disruption is immense. Between 2023 and 2028, an estimated $356 billion in worldwide branded drug sales are at risk from patent expiration.7 High-profile medications such as Merck’s cancer immunotherapy Keytruda, with over $29 billion in 2023 sales, face patent loss in 2028, setting the stage for one of the largest patent cliffs in history.3

For innovator pharmaceutical companies, an impending patent cliff is a primary driver of corporate strategy. Executive decisions regarding R&D investment, licensing of external assets, and mergers and acquisitions are often dictated by the need to restock the product pipeline before a major revenue source evaporates.3 This creates a powerful and continuous demand for new, de-risked therapeutic assets that can offset these predictable losses.

The predictability of this cycle is a crucial, yet often overlooked, strategic element. Patent expiration dates are public information, cataloged years in advance. This allows for long-range planning, not just for the innovator company and its generic competitors, but for any stakeholder capable of capitalizing on the market transformation that follows. For academic institutions, whose research programs often operate on multi-year grant cycles, this predictability is a significant asset. It allows for the proactive identification of high-potential molecules years before their patents expire, enabling the strategic planning of grant applications, the formation of collaborative research teams, and the development of preclinical models. This transforms the process from one of reactive opportunism to proactive, strategic research planning, timed to coincide with the moment a drug becomes economically and legally accessible for large-scale investigation.

1.2 The Economics of Generic Entry: Price Erosion and Market Transformation

The mechanism driving the patent cliff is the entry of generic drugs. Under the framework established by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, generic manufacturers can gain FDA approval through an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA).5 This pathway streamlines the approval process by allowing the generic manufacturer to reference the safety and efficacy data of the original innovator drug, known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). The primary requirement is to demonstrate bioequivalence, meaning the generic drug is absorbed into the body at a similar rate and to a similar extent as the brand-name product.5 By avoiding the need to repeat costly and time-consuming preclinical and clinical trials, generic manufacturers can enter the market at a fraction of the original R&D cost.6

This dramatically lower cost basis enables intense price competition upon market entry. The first generic manufacturer to file an ANDA with a patent challenge is often granted a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity, during which it can capture significant market share with a modest price discount.4 However, as additional generic competitors enter the market, prices collapse rapidly. Research demonstrates that drug prices decline substantially after patent expiration, with reductions ranging from 30% to 80% globally within a few years.1 In the highly competitive U.S. market, price drops of 80-90% are common.3 The speed and depth of this price erosion are directly correlated with the number of generic manufacturers entering the market; the entry of three to five competitors for a physician-administered drug can lead to price declines of 38-48%.9

A fascinating paradox often emerges in the post-patent market. While the price per unit plummets, the total volume of the drug prescribed and sold often increases substantially.11 This surge in utilization, driven by lower costs and improved access for patients, can be so significant that the total revenue generated from the molecule (combining both the declining brand-name sales and the growing generic sales) can actually increase in the years following patent expiration.11 This phenomenon underscores a critical point for academic research: patent expiration significantly expands patient access to a given therapy. This expansion creates a much larger and more diverse population of users, which in turn generates a richer environment for conducting real-world evidence (RWE) studies. The increased statistical power available in large electronic health record (EHR) and insurance claims databases after a drug goes generic provides a fertile ground for academic epidemiologists and data scientists to identify novel therapeutic signals or long-term safety trends that were not apparent when the drug was used by a smaller, on-patent population.

1.3 Beyond Patents: Navigating the Complex Web of Regulatory Exclusivities

To accurately determine when a drug becomes available for generic competition and academic repurposing, one must look beyond the patent portfolio alone. The FDA grants various forms of regulatory exclusivity that are entirely separate from patents issued by the USPTO.4 While patents protect the invention itself (e.g., the molecule, its formulation, or its use), regulatory exclusivities protect the market by preventing the FDA from approving a competing generic application for a specified period.6 These two systems of protection can run concurrently or separately, creating a complex, overlapping timeline of barriers.

The most significant types of FDA exclusivity include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: Provides five years of market exclusivity from the date of a drug’s first approval for a new active moiety. During the first four years of this period, the FDA cannot even accept an ANDA from a generic manufacturer.3

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): Grants seven years of market exclusivity for a drug approved to treat a rare disease or condition (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.).3

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: Provides three years of exclusivity for the approval of a new indication, formulation, or dosage form of a previously approved drug, provided that new clinical studies were essential to the approval.4

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): Adds an additional six months of exclusivity to all existing patents and exclusivities held by the sponsor for a given active moiety if the company conducts pediatric studies requested by the FDA.3

Innovator companies also employ sophisticated intellectual property strategies to extend market protection, often creating what is known as a “patent thicket”.10 This involves filing multiple, overlapping patents that cover not just the core active ingredient (a “composition-of-matter” patent) but also specific formulations, manufacturing processes, methods of use for different diseases, and even drug delivery devices.2 Each of these patents has its own 20-year term, creating a layered defense that can delay generic entry long after the original molecule’s patent has expired.

For an academic researcher or a generic manufacturer, the strategic planning for a project is dictated by a critical rule: the first legal opportunity for market entry is determined by whichever barrier—the last-to-expire relevant patent or the last-to-expire applicable exclusivity—falls last.6 Therefore, a thorough analysis requires meticulously mapping both the patent landscape and the regulatory exclusivity timeline to identify the true date when a compound becomes unencumbered and available for broad research and development.

II. The Strategic Imperative of Drug Repositioning

As the pharmaceutical industry grapples with declining R&D productivity and the immense costs of bringing a new molecule to market, drug repositioning has evolved from a series of fortunate accidents into a systematic and strategic discipline. Also known as drug repurposing or reprofiling, this approach involves identifying new therapeutic uses for existing drugs that are outside the scope of their original, approved indication.14 By leveraging compounds with established safety and manufacturing profiles, drug repositioning offers a powerful method to de-risk the development process, dramatically reducing the time, cost, and failure rates that plague traditional drug discovery. This strategy is particularly well-suited to the strengths and mission of academic research institutions.

2.1 From Serendipity to Systematic Science: The Evolution of Drug Repurposing

The history of drug repurposing is rich with examples of serendipity. Perhaps the most famous case is sildenafil (Viagra), which was originally developed by Pfizer to treat angina but was repurposed for erectile dysfunction after male participants in early clinical trials reported an unexpected side effect.14 Another landmark example is thalidomide; after being withdrawn from the market in the 1960s for causing severe birth defects, it was later discovered, through astute clinical observation, to be a highly effective treatment for a painful complication of leprosy and, decades later, for multiple myeloma.19

While these early successes were often the result of chance clinical observations, the modern paradigm of drug repurposing is intentional, rational, and increasingly driven by data and technology.16 The explosion of biomedical data from genomics, proteomics, and large-scale clinical records, combined with advances in computational biology and artificial intelligence, has enabled a shift toward systematic hypothesis generation.15 Researchers can now computationally screen thousands of compounds against molecular profiles of diseases, build complex network models to predict novel drug-target interactions, and mine electronic health records for therapeutic signals.23 This evolution from accidental discovery to a deliberate scientific strategy is what makes drug repurposing a scalable and integral component of modern therapeutic development.

2.2 The Repurposing Advantage: De-Risking Development by Reducing Time, Cost, and Failure

The strategic value of drug repurposing lies in its profound efficiency advantages over de novo drug discovery. The traditional path from a new chemical entity to an approved medicine is a long, expensive, and perilous journey. In contrast, by starting with a compound that has already been tested in humans, the repurposing pathway can bypass several of the most resource-intensive and failure-prone stages of development.

The core of this advantage is the leveraging of pre-existing data. For an approved drug, or even a compound that failed in late-stage trials for lack of efficacy, a substantial body of information on its pharmacology, formulation, potential toxicity, and human safety profile is already available.14 This allows researchers to often skip extensive preclinical toxicology studies and Phase I clinical trials, which are designed primarily to establish safety in humans.19 This acceleration is significant, as safety concerns account for approximately 30% of all failures in clinical trials.29 The primary development hurdle for a repurposed drug shifts from establishing safety to demonstrating efficacy for the new indication, typically starting with Phase II proof-of-concept studies.19

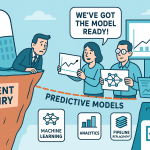

This de-risking translates into dramatic improvements in key development metrics, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of De Novo vs. Repurposed Drug Development

| Metric | De Novo Discovery | Drug Repositioning | Advantage Multiplier |

| Average Development Time | 10–17 years 29 | 3–12 years 29 | ~2-3x Faster |

| Average Development Cost | ~$2.6 billion (incl. failures) 29 | ~$300 million 30 | ~85% Cost Reduction |

| Probability of Success (from Phase I) | ~10-11% 19 | ~30% 29 | ~3x Higher Success Rate |

| Key Failure Point | Efficacy & Safety 29 | Primarily Efficacy 32 | De-risked for Safety |

| Primary IP Protection | Composition of Matter & Method of Use 19 | Primarily Method of Use 19 | Weaker IP Protection |

This stark contrast highlights why drug repurposing is not merely an alternative but a strategically superior approach for resource-constrained environments like academia. It allows researchers to translate biological insights into clinical hypotheses with a much higher probability of success and within a timeframe and budget that are more compatible with academic grant cycles.

2.3 A Modern Toolkit: Computational, Experimental, and AI-Driven Methodologies

The systematic nature of modern drug repurposing is enabled by a diverse and powerful toolkit of scientific methodologies that can be broadly categorized into computational and experimental approaches, increasingly unified by artificial intelligence.

Computational Approaches (In Silico): These methods leverage the vast and growing repositories of public biomedical data to predict new drug-disease connections without initial lab work. Key techniques include:

- Signature-Based Methods: Comparing the gene expression “signature” of a disease state with the signatures produced by various drugs to find a compound that can reverse the disease signature.19

- Network-Based Methods: Constructing complex “knowledge graphs” that map the relationships between drugs, genes, proteins, and diseases. By analyzing the topology of these networks, algorithms can infer novel connections, a concept often described as “guilt-by-association”.15

- Molecular Docking: Using 3D structural information of a protein target implicated in a disease to computationally screen libraries of known drugs to see which ones might physically bind to and modulate the target.24

Experimental Approaches (In Vitro/In Vivo): These methods involve direct testing of compounds in laboratory models of a disease.

- Target-Based Screening: If a specific molecular target is known to be critical for a disease, libraries of existing drugs can be screened directly against that target to find inhibitors or activators.19

- Phenotypic Screening: This is an agnostic approach where compounds are tested in a biologically relevant system (e.g., patient-derived cells, organoids, or small animal models) to see if they produce a desired phenotypic change (e.g., killing cancer cells, restoring normal neuronal function), without pre-supposing the molecular target.19

The Rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): AI and ML are acting as a powerful integrating force, supercharging both computational and experimental approaches. ML algorithms, particularly deep learning, can analyze vast, multi-modal datasets—including genomic data, scientific literature, clinical trial data, and EHRs—to identify complex, non-obvious patterns that can predict novel drug-indication pairs with increasing accuracy.14 AI is transforming drug repurposing from a data-mining exercise into a predictive science.

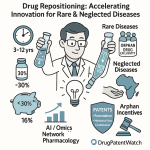

The very nature of this work aligns fundamentally with the core mission and capabilities of academic research. De novo drug discovery is a highly industrialized process requiring capital-intensive infrastructure for medicinal chemistry, large-scale screening, and manufacturing—resources typically found in large pharmaceutical companies.38 In contrast, the initial stages of drug repurposing are knowledge-intensive. Success hinges on deep biological insight into disease mechanisms, clever computational analysis, and innovative experimental design, which are the hallmarks of the academic research environment.39 Furthermore, academia’s public service mission makes it the natural home for pursuing repurposing opportunities for rare and neglected diseases, which are often deemed commercially unviable by industry and represent areas of profound unmet medical need.16 Thus, drug repurposing is not simply one of many research options for academia; it is a strategically aligned endeavor that leverages its greatest assets while mitigating its primary institutional limitations.

III. The Catalyst Effect: How Patent Expiration Unlocks Repurposing Potential

While drug repurposing is a powerful strategy in its own right, the expiration of a drug’s patent and associated exclusivities acts as a potent catalyst, creating a uniquely fertile environment for academic-led research. This “catalyst effect” operates through three interconnected mechanisms—economic, scientific, and legal—that converge to dramatically lower the barriers to entry for translational science. The simultaneous reduction of these hurdles creates a powerful synergy, making the investigation of off-patent drugs one of the most efficient and impactful pathways for academic researchers to translate basic science into clinical application.

3.1 Economic Liberation: The Impact of Reduced Drug Acquisition Costs on Research Feasibility

The single most significant practical barrier to large-scale academic research on a patented drug is its cost. The price of an on-patent, brand-name medication can make ambitious clinical studies financially prohibitive for academic investigators, whose work is typically funded by government or non-profit grants that are not designed to cover multi-million-dollar drug acquisition budgets. A research team might have a brilliant hypothesis for a new use of an existing drug, but the cost of simply acquiring the necessary supply for a moderately sized Phase II trial can exceed the entire grant award.

Patent expiration fundamentally alters this equation. The entry of multiple generic manufacturers into the market triggers intense price competition, leading to price reductions of 80-90% or more.3 This massive drop in acquisition cost is an economic liberation for the research community. Suddenly, studies that were once financially impossible become feasible. Academic researchers can design and conduct larger, more statistically robust clinical trials. They can explore preventative strategies, which often require treating large numbers of healthy individuals over long periods, a model that is untenable with expensive, on-patent drugs.43 Furthermore, the affordability of generic drugs enables the investigation of novel combination therapies, where multiple off-patent agents can be tested together without the astronomical cost of combining on-patent products.31 This economic shift is the primary catalyst that moves repurposing ideas for established drugs from theoretical hypotheses to testable clinical research projects.

3.2 The Value of Known Unknowns: Leveraging Decades of Pre-existing Safety and Pharmacokinetic Data

By the time a blockbuster drug’s patent expires, it has typically been on the market for a decade or more and has been used by millions of patients worldwide.7 This extensive clinical use generates an invaluable legacy of data—a deep and broad understanding of the drug’s safety profile, its pharmacokinetics (how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes it), its pharmacodynamics (its effect on the body), common side effects, and appropriate dosing regimens.14

For academic researchers, this repository of human data is a priceless asset that profoundly de-risks the development process for a new indication.14 The traditional drug development pipeline is fraught with failure, with many promising compounds abandoned due to unforeseen toxicity in early human trials.29 With a repurposed off-patent drug, the fundamental safety questions in humans have largely been answered. This allows researchers to often bypass the lengthy and expensive preclinical toxicology studies and Phase I safety trials, and proceed directly to Phase II proof-of-concept studies designed to test for efficacy in the new disease.19 This can shorten the clinical development timeline by several years and save millions of dollars.29

Moreover, this existing knowledge base allows for more rational and efficient clinical trial design. Researchers are not starting from scratch; they have established data on safe dosage ranges, how the drug is metabolized, and what side effects to monitor for.22 This allows for the design of more targeted, biomarker-driven trials that can yield a clear efficacy signal more quickly and with fewer patients. The availability of this rich safety and pharmacokinetic data provides a solid foundation upon which new clinical investigations can be built, significantly increasing the probability of success compared to a novel, untested compound.

3.3 Navigating the IP Landscape: Reduced Legal Barriers for Off-Patent Compound Investigation

Intellectual property is the bedrock of the pharmaceutical industry, and the robust patent protection surrounding an on-patent drug can create significant legal barriers to independent research. While certain research exemptions exist, the prospect of inadvertently infringing on a company’s core patents can create a chilling effect, discouraging academic institutions from investing significant resources into a project that could be halted by litigation.

The expiration of the core composition-of-matter patent and its associated regulatory exclusivities removes this primary legal obstacle.16 Once a drug is available as a generic, academic labs have the “freedom to operate”—they can legally purchase the active pharmaceutical ingredient or the generic formulation and use it for research purposes without fear of infringing the innovator’s foundational patent on the molecule itself.45 This clears the way for a broad range of preclinical and clinical investigations.

While the freedom to research is greatly enhanced, the path to commercializing a new use for an off-patent drug presents a different set of IP challenges. Since the molecule itself is in the public domain, new IP protection cannot be based on the compound. Instead, the strategy must shift to protecting the new discovery. This typically involves filing for new “method-of-use” patents, which cover the use of the drug for the new, specific disease.19 Additional layers of protection can be built by developing and patenting novel formulations, delivery mechanisms, or combination therapies that are optimized for the new indication.33 While these secondary patents are generally considered weaker and more difficult to enforce than a composition-of-matter patent, they represent a critical area where academic innovation can create new, protectable value that is essential for attracting a commercial partner to bring the new treatment to patients.

The convergence of these three factors—drastically lower costs, a wealth of pre-existing human safety data, and freedom from core IP constraints—creates a powerful synergistic effect. In the language of chemistry, it dramatically lowers the “activation energy” required to initiate a translational research project. The financial, scientific, and legal barriers that constitute the “valleys of death” in traditional drug development are all significantly reduced simultaneously. This makes the repurposing of off-patent drugs one of the most capital-efficient and de-risked forms of translational science available, creating a unique and powerful opportunity for academic institutions to make a direct and rapid impact on clinical practice.

IV. The Academic Research Engine: Capabilities, Models, and Challenges

Academic institutions are uniquely positioned to serve as the primary engine for post-patent drug repositioning. Their fundamental structure, which integrates basic science research with clinical medicine, and their public service mission create an environment ripe for the kind of knowledge-driven discovery that underpins successful repurposing. However, realizing this potential requires navigating significant institutional challenges related to funding, expertise, and the inherent conflicts between academic and commercial incentives.

4.1 The Unique Strengths of Academic-Led Discovery

The academic medical center is a powerful ecosystem for translational research. It fosters a unique proximity and collaborative culture between basic scientists, who elucidate the fundamental mechanisms of disease, and clinicians, who see the real-world manifestations of those diseases in patients. This environment gives rise to three key strengths in the context of drug repurposing:

- Translational and Disease Focus: The constant interaction between the lab and the clinic is a potent catalyst for generating novel, clinically relevant hypotheses. Clinicians may observe unexpected off-label effects of a drug in their patients, which can spark a basic science investigation into the underlying mechanism. Conversely, a basic scientist’s discovery of a new disease pathway can lead a clinical collaborator to recognize that an existing drug targets that very pathway.39 This bidirectional flow of information is a powerful engine for discovery that is difficult to replicate in more siloed industrial settings.

- Basic Science Expertise: Academia is the world’s primary source of foundational knowledge about biology and disease. University researchers excel at the deep, mechanistic work—elucidating signaling pathways, identifying novel molecular targets, and developing sophisticated disease models—that provides the rational basis for hypothesis-driven repurposing.38 Much of the industrial R&D pipeline is built upon decades of this publicly funded foundational research.49

- Public Mission and Rare Diseases: A core mission of many academic institutions is to serve the public good and address unmet medical needs, regardless of commercial potential. This aligns perfectly with the opportunity to repurpose off-patent drugs for rare and neglected diseases. With small patient populations, these conditions often fail to offer the return on investment necessary to justify a high-risk, de novo drug development program by a pharmaceutical company.41 Academic researchers, supported by government grants and philanthropic funding, are therefore the primary drivers of therapeutic innovation in these areas, and drug repurposing is their most efficient tool.16

4.2 Bridging the “Valley of Death”: The Role of University Technology Transfer

A scientific discovery, no matter how profound, has no impact on patients until it is translated into an approved therapy. This requires navigating the “valley of death”—the gap between an academic discovery and a commercially viable product. The university’s Technology Transfer Office (TTO) is the critical bridge across this gap.53

The TTO’s primary functions in a repurposing project are to evaluate the discovery for its commercial potential, develop and manage a robust intellectual property strategy, and identify and negotiate with external partners (biotechnology or pharmaceutical companies) to license the technology for further development.55 This involves a process of “technology triage,” where the TTO must assess the strength of the scientific data, the defensibility of potential new patents (e.g., method-of-use), and the size of the potential market to prioritize the university’s limited resources for patent prosecution and business development.55 The TTO acts as the crucial interface between the academic culture of discovery and the commercial culture of development, translating academic research into an asset that can attract the private investment needed for late-stage clinical trials and regulatory approval.53

4.3 Inherent Hurdles: Overcoming Gaps in Funding, Regulatory Expertise, and IP Strategy

Despite their strengths, academic institutions face significant internal hurdles in advancing repurposing projects. These challenges often stem from the fact that universities are structured to support basic research, not industrial drug development.

- Funding Gaps: While repurposing is significantly cheaper than de novo discovery, the cost of conducting rigorous Phase II and III clinical trials can still run into the tens of millions of dollars, far exceeding the budget of a typical NIH R01 grant.14 Securing this level of translational funding is a major barrier for academic investigators.16

- Lack of Internal Expertise: Most universities lack the dedicated, in-house expertise required for late-stage drug development. This includes specialists in regulatory affairs who can navigate the complex process of filing an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the FDA, experts in pharmaceutical sciences who can oversee Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) production of clinical trial materials, and experienced toxicologists to design and interpret required safety studies.39

- The IP Conundrum for Off-Patent Drugs: The most significant commercial challenge is securing strong, defensible intellectual property for a new use of a known compound. Method-of-use patents, the primary tool available, are notoriously weaker than composition-of-matter patents. Their enforcement can be difficult, as physicians can prescribe the generic version of the drug “off-label” for the new indication, potentially circumventing the patent.19 This perceived weakness in the IP can make potential commercial partners hesitant to invest the substantial sums required for late-stage trials and commercialization.32

A fundamental misalignment often exists between the incentive structures of academia and the practical requirements of drug development. The academic career path is built on a “publish or perish” model, which rewards novel discoveries and rapid publication in high-impact journals.60 However, the work required to de-risk a repurposing project for a commercial partner—such as conducting rigorous, protocol-driven GLP toxicology studies or overseeing GMP manufacturing campaigns—is meticulous and essential, but it is not typically considered novel or groundbreaking research that leads to high-profile publications.60 Furthermore, the pressure to publish quickly can be in direct conflict with the need to file for patent protection

before any public disclosure, a critical step for preserving commercial value.32 To truly succeed in this space, universities must evolve to create institutional structures and career pathways that recognize and reward the rigorous work of translational science on par with basic discovery.

4.4 Comparing Motivations and Methodologies: Academic vs. Industry-Led Repurposing

The goals, strategies, and cultures surrounding drug repurposing differ significantly between academic and industrial settings. Understanding these differences is key to fostering effective collaborations.

- Goals and Outcomes: Industry-led repurposing is often a component of a “life-cycle management” strategy for a drug that is still on-patent. The goal is to find a new indication to generate additional revenue and extend the drug’s commercial life, with decisions driven primarily by return on investment (ROI) and the potential for market exclusivity.32 In contrast, academic repurposing is more frequently driven by scientific curiosity, a desire to understand disease, and a public health mission. This often leads academic researchers to focus on off-patent, generic drugs and their application to rare or neglected diseases that lack commercial appeal.39

- Methodological Focus: While both sectors use the same fundamental toolkit, their focus differs. Academic labs are often at the forefront of developing novel computational methods and conducting deep, mechanistic studies to understand why a drug works in a new context.63 Industry, on the other hand, excels at applying these methods at scale, with a focus on high-throughput screening, process optimization, and a clear, milestone-driven path toward regulatory submission and commercialization.61

- Data Sharing and Publication: The cultural divide is perhaps most apparent in the handling of data. The academic world thrives on the rapid and open dissemination of knowledge through publications and conferences.60 In the highly competitive pharmaceutical industry, data from clinical trials and development programs are often treated as valuable trade secrets, protected to maintain a commercial advantage.32 This fundamental difference in culture regarding transparency and data sharing is a primary source of friction in academic-industry partnerships and must be carefully navigated through well-structured collaboration agreements.

V. A Practical Framework for Academic-Led Repurposing Initiatives

To move from opportunistic discovery to a systematic program, academic institutions require a structured framework for identifying, validating, and advancing repurposing candidates. This framework should be an iterative, integrated process that synthesizes information from patent, scientific, and clinical databases to overcome the “cold start” problem—the challenge of knowing where to begin among thousands of potential drug-disease combinations. A successful program involves three key phases: opportunity identification, preclinical validation, and translational strategy.

5.1 Phase 1: Opportunity Identification

The initial phase involves systematically scanning the landscape to generate a prioritized list of off-patent or soon-to-be off-patent drugs that hold promise for a new indication.

Systematic Patent Cliff Analysis

The foundation of this strategy is the proactive monitoring of patent and exclusivity expirations. Researchers can use a suite of public and commercial databases to build a calendar of opportunities.

- Using the FDA Orange Book: The Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, commonly known as the Orange Book, is the definitive resource for FDA-approved drugs and their associated patents and exclusivities in the U.S..67 A researcher can search the Orange Book by active ingredient to find all approved products, the corresponding New Drug Application (NDA) holder, and a list of all relevant patents and their expiration dates.69 The database also lists regulatory exclusivity codes (e.g., NCE, ODE) and their expiration dates.69 By cross-referencing all listed patents and exclusivities, one can determine the latest date of protection and thus the earliest possible date for generic entry.12

- Leveraging Global and Specialized Databases: To gain a more comprehensive view, researchers should consult additional databases. WIPO’s Pat-INFORMED and the Medicines Patent Pool’s MedsPaL provide patent status information for key medicines in numerous countries, which is essential for global health research.71 The Evergreen Drug Patent Database specifically tracks patent extensions and “evergreening” strategies, helping to identify drugs with complex IP landscapes.13 Commercial platforms like DrugPatentWatch offer sophisticated tools and alerts for monitoring patent expirations and litigation that may lead to earlier generic entry.73 A summary of these key resources is provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Key Public Databases for Patent Expiration and Repurposing Research

| Database Name | Primary Function | Key Information Provided | Strategic Use in Repurposing Workflow |

| FDA Orange Book | Official U.S. registry of approved drugs, patents, and exclusivities. | Patent numbers, expiration dates, exclusivity codes and dates, therapeutic equivalence ratings. | Identify initial LOE date to set project timeline; determine all patents and exclusivities that must expire. 67 |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | Global registry of clinical trials. | Study protocols, interventions, status (recruiting, completed), outcome measures, results. | Assess current research landscape; avoid redundant studies; identify potential collaborators and competing efforts. 74 |

| PubMed | Database of biomedical literature. | Scientific publications on mechanism of action, preclinical studies, case reports, clinical observations. | Generate biological hypotheses for identified candidates; find evidence of off-label use or novel mechanistic insights. 24 |

| WIPO Pat-INFORMED | Global medicine patent information gateway. | Patent status for specific drugs in various countries, provided directly by companies. | Determine global freedom to operate for diseases prevalent outside the U.S.; facilitate procurement for international trials. 71 |

| MedsPaL | Medicines Patents & Licenses Database. | IP status of key health products in low- and middle-income countries, including patent and licensing data. | Support global health initiatives by clarifying IP landscape in resource-limited settings. 72 |

| Evergreen Drug Patent Search | Database of patent extensions and evergreening tactics. | Data on additional protections, delays in generic entry, and number of patents per drug. | Identify complex IP “thickets” that may complicate freedom to operate even after primary patent expires. 13 |

Literature and Clinical Data Mining

Once a list of candidate drugs is generated based on upcoming patent expirations, the next step is to build a scientific case for their potential in a new disease area.

- PubMed for Hypothesis Generation: PubMed is an indispensable tool for understanding a drug’s known biological activities. Text-mining algorithms can be applied to its vast corpus of over 30 million citations to systematically identify papers that link a drug to a new disease, pathway, or molecular target.24 Manual searches can uncover case reports of off-label use, preclinical studies that suggest a novel mechanism of action, or review articles that synthesize disparate findings into a new hypothesis.22

- ClinicalTrials.gov for Ongoing Research: Before launching a new project, it is critical to understand the existing research landscape. A thorough search of ClinicalTrials.gov using keywords such as the drug name, the target disease, and terms like “repurposing” or “repositioning” can reveal all registered trials involving that drug.74 This search can identify whether a similar idea is already being tested, reveal the design of ongoing studies, and uncover results from completed trials that may inform the new project’s design.79

5.2 Phase 2: Preclinical Validation

With a prioritized list of drug-disease hypotheses, the project moves into the laboratory for experimental validation.

- Computational Modeling and In Silico Screening: This step often precedes wet-lab work. The computational tools described in Section II—such as knowledge graphs, graph convolutional networks (GCNs), and deep learning models—can be used to further refine and rank the hypotheses.36 These models integrate multiple data types (e.g., drug structure, gene expression, protein interactions) to predict the likelihood of a therapeutic effect, allowing researchers to focus their limited lab resources on the most promising candidates.34

- Target-Based and Phenotypic Screening: The top candidates from the in silico analysis are then subjected to experimental validation. In a target-based approach, the drug is tested for its ability to modulate a specific protein known to be involved in the disease. In a phenotypic approach, the drug is tested in a more complex biological model of the disease—such as patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), organoids, or animal models—to see if it can reverse the disease phenotype.19 Positive results from these preclinical studies provide the essential proof-of-concept needed to advance to the next stage.

5.3 Phase 3: Translational Strategy

With a validated preclinical candidate, the focus shifts to designing a path to human trials and building a viable commercialization strategy.

- Designing Proof-of-Concept Clinical Studies: The goal is to design an efficient Phase II clinical trial that can provide a clear signal of efficacy. Leveraging the drug’s known safety and pharmacokinetic profile, these trials can often be smaller, shorter, and more focused on biomarker endpoints that demonstrate the drug is hitting its target and having the desired biological effect in patients.

- Building a Defensible Intellectual Property Portfolio: This is a critical step managed by the TTO in collaboration with the researchers. Since the drug itself cannot be patented, the strategy must focus on creating new, patentable inventions around its new use. A multi-layered IP strategy is the most robust approach, as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3: Intellectual Property Strategies for Repurposed Off-Patent Drugs

| IP Strategy | Description | Strength of Protection | Key Challenge for Academia | Example |

| Method-of-Use Patent | Claims a new method of using the existing drug to treat a specific disease. | Moderate | Difficult to enforce against off-label prescribing by physicians. 33 | A patent on the use of metformin to treat a specific type of cancer. |

| New Formulation Patent | Claims a novel formulation of the drug (e.g., extended-release, topical, injectable) optimized for the new indication. | Strong | Requires significant formulation development expertise and resources, often beyond typical academic labs. 33 | Developing a long-acting injectable version of an oral drug for a chronic neurological condition. |

| Combination Therapy Patent | Claims the use of the repurposed drug in combination with one or more other agents to achieve a synergistic therapeutic effect. | Strong | Requires demonstrating that the combination is novel, non-obvious, and provides a benefit beyond the individual drugs. 33 | A patent covering the co-administration of an old chemotherapy agent with a repurposed drug that sensitizes tumors to its effects. |

| New Dosage/Regimen Patent | Claims a specific, novel dosing schedule or regimen that is shown to be uniquely effective for the new indication. | Moderate to Weak | Requires extensive clinical data to prove the specific regimen is novel and superior to standard dosing. | A patent on a low-dose, daily regimen of a drug previously used at high doses for acute conditions. |

By successfully navigating these three phases, an academic institution can transform the opportunity presented by a patent expiration into a validated therapeutic candidate with a clear path toward clinical impact and potential commercialization.

VI. Case Studies in Academic-Driven Repurposing

The history of drug repurposing is replete with success stories that underscore the pivotal role of academic research in identifying and validating new uses for existing medicines. These cases are not merely historical anecdotes; they represent distinct, repeatable archetypes of discovery that can serve as strategic models for future academic initiatives. By analyzing these patterns—from rational, mechanism-driven hypotheses to astute clinical observations—institutions can better identify and support the types of projects that align with their unique strengths.

6.1 Sildenafil: From Angina Pectoris to Pulmonary Hypertension – Uncovering Novel Mechanisms

Sildenafil’s journey is the quintessential story of industrial serendipity followed by academic ingenuity. Developed by Pfizer in the 1990s as a potential treatment for angina, its modest effects on chest pain were overshadowed by a consistently reported side effect in male clinical trial participants: penile erections.14 This led to its highly successful repurposing as Viagra for erectile dysfunction.

However, the story did not end there. Academic researchers, understanding the drug’s fundamental mechanism of action as a phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor, recognized that its effects were not limited to one part of the body. PDE5 is an enzyme that breaks down cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), a key signaling molecule in the nitric oxide (NO) pathway that causes vasodilation (the relaxation and widening of blood vessels).85 Researchers in academic medical centers hypothesized that by inhibiting PDE5 in the vasculature of the lungs, sildenafil could be an effective treatment for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a devastating disease characterized by dangerously high blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries.87

This hypothesis was tested and validated through a series of academic-led investigations and small-scale clinical trials. These early studies demonstrated that sildenafil could indeed produce a favorable hemodynamic response in PAH patients, lowering pulmonary artery pressure and improving cardiac function.89 This crucial proof-of-concept work, generated within academia, provided the biological plausibility and clinical evidence necessary to justify larger, industry-sponsored pivotal trials, such as the SUPER (Sildenafil Use in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension) trial, which ultimately led to the FDA’s approval of sildenafil (marketed as Revatio) for the treatment of PAH.88 The sildenafil story continues to expand within academia, with ongoing research exploring its potential in cancer therapy, neurodegenerative diseases, and other conditions, demonstrating how a single repurposed drug can become a rich platform for further academic discovery.90 This case exemplifies the

“Mechanism-Driven” archetype, where academic scientists rationally apply a deep understanding of a drug’s molecular mechanism to a new disease that shares the same biological pathway.

6.2 Thalidomide: A Renaissance Fueled by Academic Inquiry into Immunology and Oncology

The story of thalidomide is one of tragedy and redemption, with academic research playing the central role in its revival. Originally marketed in the late 1950s as a safe, non-addictive sedative, it was widely used by pregnant women for morning sickness before being catastrophically linked to severe congenital malformations, leading to its global withdrawal in 1961.21

The drug’s first repurposing was a product of pure, serendipitous clinical observation. In 1964, Dr. Jacob Sheskin, a physician at Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem, administered thalidomide as a last-resort sedative to a patient suffering from the extreme pain of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), a severe inflammatory complication of leprosy. To his astonishment, the patient’s painful skin lesions dramatically improved overnight.20 This single, astute observation by an academic clinician, later confirmed in larger studies, led to thalidomide becoming the standard of care for ENL.20

Thalidomide’s second, and more commercially significant, renaissance was driven by academic basic science. In the 1990s, research teams, notably one led by Dr. Gilla Kaplan at Rockefeller University, began to dissect the drug’s mysterious biological effects. They discovered that thalidomide possessed powerful immunomodulatory and anti-angiogenic (inhibiting the formation of new blood vessels) properties.21 This new mechanistic understanding, born from academic inquiry, led to the hypothesis that thalidomide could be effective against cancers, like multiple myeloma, that depend on angiogenesis and are sensitive to immune modulation.95 Subsequent clinical trials, many led by academic investigators, confirmed its efficacy, and in 2006, thalidomide was approved by the FDA for the treatment of multiple myeloma, completing its remarkable journey from pariah to pillar of oncology.93 This case is a prime example of the

“Clinical Observation” archetype, where an unexpected therapeutic effect observed in a clinical setting by an academic researcher triggers fundamental basic science investigations that uncover a new mechanism and unlock a host of new therapeutic applications.

6.3 Metformin: The Journey from Diabetes Management to Widespread Cancer Clinical Trials

Metformin, an inexpensive, off-patent generic drug, is the most widely prescribed oral medication for type 2 diabetes. Its potential as a repurposed cancer agent did not emerge from a pharmaceutical company’s R&D program but from the work of academic epidemiologists.97 In the mid-2000s, researchers analyzing large patient databases and medical records began to notice a compelling statistical signal: diabetic patients taking metformin appeared to have a significantly lower incidence of various cancers and lower cancer-related mortality compared to patients on other diabetes medications.98

This epidemiological finding, a correlation observed in real-world patient populations, sparked a massive wave of academic basic science research to determine a causal link. Laboratories around the world began investigating metformin’s molecular mechanisms, uncovering a dual mode of action: a direct effect on cancer cells by inhibiting the mTOR pathway via AMPK activation, and an indirect, systemic effect by lowering circulating insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) levels, which are known tumor growth promoters.98

The combination of a strong epidemiological signal, a plausible biological mechanism, and the drug’s off-patent status—making it cheap and readily available—led to an explosion of academic- and government-funded clinical trials. Hundreds of trials have been initiated to test metformin for the prevention and treatment of a wide array of cancers, including breast, prostate, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer.100 While the results of these trials have been mixed, with some failing to show a benefit in advanced disease, the sheer scale of the investigation is a testament to the power of academic-led research when a promising, affordable drug is available. This case study perfectly illustrates the

“Epidemiological Signal” archetype, where the analysis of large-scale population data by academic researchers generates a powerful hypothesis that drives years of subsequent mechanistic and clinical investigation.

6.4 Raloxifene: Large-Scale Academic and Government-Led Trials for Breast Cancer Prevention

Raloxifene was originally developed and approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. The first clue to its potential as a breast cancer preventive agent emerged as a secondary finding from large, industry-sponsored osteoporosis trials, such as the MORE (Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation) trial.106 In these studies, researchers observed that women taking raloxifene had a significantly lower incidence of estrogen receptor (ER)-positive invasive breast cancer compared to those on placebo.106

This promising signal from an industry trial was then rigorously pursued through a massive, publicly funded, academic-led clinical trial: the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR). Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and run by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), a cooperative academic research group, the STAR trial enrolled nearly 20,000 high-risk postmenopausal women and directly compared the efficacy and side effects of raloxifene to tamoxifen, the existing standard for breast cancer prevention.107 The trial found that raloxifene was nearly as effective as tamoxifen in reducing the risk of invasive breast cancer but with a lower risk of serious side effects like uterine cancer and blood clots.107 These definitive results, generated through a large-scale academic and governmental collaboration, led to the FDA’s approval of raloxifene for breast cancer risk reduction.108 This case represents the

“Secondary Endpoint” archetype, where a therapeutic signal observed as a secondary outcome in a trial for one indication is validated and expanded upon in a large, dedicated trial led by the academic and public research community.

VII. Forging the Future: Policy, Funding, and Collaborative Models

To fully realize the potential of the post-patent dividend, a robust and supportive ecosystem is required. This ecosystem must bridge the gaps between academic discovery, industrial development, and patient access. It requires proactive strategies from government funding bodies, innovative models from philanthropic organizations, and a fundamental evolution in how universities approach translational research and collaboration. The future of academic repurposing will be defined by the ability to build these supportive structures and to harness the transformative power of artificial intelligence to systematically validate new therapeutic opportunities at an unprecedented scale.

7.1 The Role of Government: Lessons from NCATS and the Medical Research Council (MRC)

Government agencies are uniquely positioned to de-risk early-stage translational science and facilitate the pre-competitive research that benefits the entire biomedical ecosystem. Two leading examples are the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) in the United States and the Medical Research Council (MRC) in the United Kingdom.

- NCATS (USA): Established to overcome bottlenecks in the translational research pipeline, NCATS has several programs that directly support and enable academic drug repurposing.112 The Discovering New Therapeutic Uses for Existing Molecules (New Therapeutic Uses) program, for example, facilitates collaborations between academic researchers and pharmaceutical companies.113 Companies provide proprietary compounds that have cleared early-stage development, and NCATS provides funding and, crucially, template legal agreements (e.g., collaborative research agreements, confidential disclosure agreements) that dramatically shorten the time required to establish these complex partnerships.113 Other programs like the Bridging Interventional Development Gaps (BrIDGs) and Therapeutics for Rare and Neglected Diseases (TRND) provide direct, in-kind support, where NCATS scientists partner with academic investigators to conduct the late-stage preclinical work (e.g., toxicology, formulation) necessary to file an IND application with the FDA.112

- MRC (UK): The MRC has pioneered a model of industry-academia collaboration, notably through its partnership with AstraZeneca.66 In this initiative, AstraZeneca made a portfolio of well-characterized but deprioritized compounds available to UK academic researchers. The MRC managed the peer-review process and provided funding for the selected projects, which were focused on using the compounds as tools to investigate disease mechanisms and validate new targets.66 This model leverages industry’s assets (compounds and data) and academia’s strengths (deep disease biology expertise) to advance fundamental science and generate new therapeutic hypotheses in a pre-competitive space.66

7.2 The Rise of Philanthropy: How Non-Profits are Catalyzing University Research

Philanthropic organizations are playing an increasingly vital role in funding academic drug repurposing, often stepping in to support projects that fall outside the scope of traditional government grants or lack the commercial appeal for industry investment. These mission-driven funders are agile and can target specific areas of high unmet need.

Organizations like Cures Within Reach and Every Cure are dedicated exclusively to funding drug repurposing research.119 They provide grants to academic researchers for proof-of-concept clinical trials, often focusing on rare diseases or underserved patient populations.121 Disease-specific foundations, such as the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF) or the MEPAN Foundation, also actively fund repurposing projects relevant to their specific missions.123 A key trend in this space is the growing focus on validating hypotheses generated by artificial intelligence. Cures Within Reach, for example, has launched funding opportunities specifically for clinical trials designed to test AI-driven drug-disease predictions, directly bridging the gap between computational discovery and human clinical evidence.119

7.3 Structuring Success: Intellectual Property Models for University-Industry Collaborations

Effective collaboration between universities and industry is essential for translating academic discoveries into approved therapies, and the cornerstone of these partnerships is a well-defined intellectual property model. The inherent tension between academia’s need to publish and industry’s need to protect confidential information and secure market exclusivity must be addressed upfront.32

A common and effective model for repurposing collaborations involves a clear delineation of ownership. The industry partner retains the background IP on the original compound and its associated data. The academic institution, in turn, owns the new foreground IP generated during the collaboration, typically in the form of a method-of-use patent for the new indication.66 The collaboration agreement then grants the industry partner an exclusive first option to license this new IP from the university. This structure provides a clear incentive for both parties: the university can leverage the company’s assets to make a discovery and create a new patentable invention, while the company gains access to novel, de-risked opportunities to expand its pipeline. The template agreements developed by organizations like NCATS are invaluable tools for standardizing these arrangements and accelerating the negotiation process, which can otherwise take a year or more.66

7.4 The Next Frontier: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are set to revolutionize drug repurposing, transforming it from a targeted, hypothesis-driven process into a comprehensive, predictive science. AI algorithms can integrate and analyze biomedical data at a scale and complexity far beyond human capability, sifting through genomics, proteomics, EHRs, chemical structures, and the entire body of scientific literature to identify novel drug-disease relationships.127 These tools are moving beyond simple pattern recognition to predictive modeling of drug efficacy, toxicity, and patient response, allowing for the

in silico prioritization of thousands of potential repurposing candidates.37

However, the adoption of AI is not without challenges. The performance of these models is highly dependent on the quality, scale, and integration of the input data; biases or gaps in the data can lead to flawed predictions.127 Furthermore, the “black box” nature of some complex deep learning models can make it difficult to understand the biological rationale behind a prediction, creating a hurdle for both scientific validation and regulatory acceptance.127 Ultimately, every AI-generated hypothesis must be rigorously tested and validated through traditional experimental and clinical research.

The future of academic repurposing is therefore inextricably linked to AI, but not as a replacement for scientific inquiry. Instead, the strategic challenge for academic institutions is shifting. It is moving from “how do we find a new use for a single drug?” to “how do we build an efficient, scalable platform to experimentally validate the top 100 predictions generated by our AI model this year?”. This represents a fundamental evolution from individual, investigator-led projects to institutional “validation engines.” Success in this new era will require a paradigm shift in infrastructure, funding, and mindset, focusing on high-throughput validation and rapid “fail-fast” clinical signals to efficiently process the vast number of opportunities that AI will present. This is the frontier where academia is best positioned to lead, translating computational predictions into tangible clinical progress.

7.5 Strategic Recommendations for Stakeholders

To build a more effective and sustainable ecosystem for academic drug repurposing, stakeholders across academia, funding bodies, and government must adopt new strategies and models.

For Academic Institutions:

- Establish Dedicated, Multi-disciplinary “Repurposing Hubs”: Create integrated centers that bring together experts in pharmacology, clinical medicine, computational biology, data science, regulatory affairs, and technology transfer. These hubs would serve as institutional focal points for identifying opportunities, securing funding, and managing projects.

- Create Translational Career Tracks: Develop academic career pathways that explicitly recognize and reward achievements in translational science, including patent filings, IND applications, and successful clinical trial execution, on par with traditional metrics like publications and basic research grants.

- Utilize Patent Expiration Data for Strategic Planning: TTOs and research leadership should proactively monitor the patent landscape, using the predictable timeline of patent cliffs to inform long-range research priorities, faculty recruitment, and infrastructure investments.

For Funding Bodies (Government & Non-Profit):

- Develop Targeted Funding Mechanisms: Create grant programs specifically designed to fund the critical “middle ground” of repurposing research: late-stage preclinical development (e.g., GLP toxicology, GMP manufacturing) and early-phase (Phase I/II) clinical trials, which are often too expensive for basic research grants but too early for venture capital.

- Invest in Data Infrastructure: Fund the creation, curation, and integration of high-quality, standardized, and publicly accessible biomedical databases. High-quality data is the essential fuel for the next generation of AI-driven repurposing models.

- Incentivize Pre-Competitive Data Sharing: Encourage and fund collaborations that involve the sharing of data and deprioritized compounds from industry with academic researchers, following the models established by NCATS and the MRC.

For Policymakers:

- Explore New Regulatory Incentives: Consider creating new forms of market exclusivity (e.g., a period of “repurposing exclusivity”) for off-patent drugs that successfully gain FDA approval for new indications, particularly for rare diseases or areas of high public health need. This would create a powerful commercial incentive for companies to partner with and invest in academic discoveries.

- Streamline Regulatory Pathways for Academic-Sponsored Trials: Develop clearer guidance and support mechanisms within the FDA to assist academic investigators in navigating the IND process for repurposed compounds, reducing the regulatory burden on non-commercial sponsors.

Works cited

- The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: A Systematic Literature Review – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6132437/

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- What Happens When a Drug Patent Expires? Understanding Drug …, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-happens-when-a-drug-patent-expires/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Generic Drug Entry Timeline: Predicting Market Dynamics After Patent Loss, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/generic-drug-entry-timeline-predicting-market-dynamics-after-patent-loss/

- The Multi-Billion Dollar Countdown: Decoding the Patent Cliff and Seizing the Generic Opportunity – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patent-expirations-seizing-opportunities-in-the-generic-drug-market/

- Navigating pharma loss of exclusivity | EY – US, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/life-sciences/navigating-pharma-loss-of-exclusivity

- Drug Patents: Essential Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Protection – UpCounsel, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.upcounsel.com/how-long-does-a-drug-patent-last

- Learning from the Pharmaceutical Industry: How to Avoid a Patent Cliff – Caldwell Law, accessed August 8, 2025, https://caldwelllaw.com/news/learning-from-the-pharmaceutical-industry-how-to-avoid-a-patent-cliff/

- The Impact of Patent Cliff on the Pharmaceutical Industry – Bailey Walsh, accessed August 8, 2025, https://bailey-walsh.com/news/patent-cliff-impact-on-pharmaceutical-industry/

- Patent Expiration and Pharmaceutical Prices | NBER, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.nber.org/digest/sep14/patent-expiration-and-pharmaceutical-prices

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- Evergreen Drug Patent Database – UC College of the Law, accessed August 8, 2025, https://sites.uclawsf.edu/evergreensearch/

- Drug repurposing: Clinical practices and regulatory pathways – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12048090/

- Drug repurposing: approaches, methods and considerations – Elsevier, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.elsevier.com/industry/drug-repurposing

- Drug repositioning – Wikipedia, accessed August 8, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_repositioning

- Genomics-Enabled Drug Repurposing and Repositioning A Workshop | National Academies, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/genomics-enabled-drug-repurposing-and-repositioning-a-workshop

- Repurposing Viagra: the ‘little blue pill’ for all ills? – The Pharmaceutical Journal, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/feature/repurposing-viagra-the-little-blue-pill-for-all-ills

- Drug Repurposing Strategies, Challenges and Successes | Technology Networks, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.technologynetworks.com/drug-discovery/articles/drug-repurposing-strategies-challenges-and-successes-384263

- Part One: An Overview of Drug Repurposing – InVivo Biosystems, accessed August 8, 2025, https://invivobiosystems.com/drug-discovery/part-one-an-overview-of-drug-repurposing/

- Thalidomide: Poster Child for Drug Repurposing – CDD Vault, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.collaborativedrug.com/cdd-blog/thalidomide-poster-child-for-drug-repurposing

- A review of computational drug repurposing – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6989243/

- Drug Repurposing: Strategies and Study Design for Bringing Back Old Drugs to the Mainline, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374338651_Drug_Repurposing_Strategies_and_Study_Design_for_Bringing_Back_Old_Drugs_to_the_Mainline

- Drug Repurposing: An Effective Tool in Modern Drug Discovery – PubMed, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36852389/

- Drug repositioning what, why and how – Open Access Journals, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.openaccessjournals.com/articles/drug-repositioning-what-why-and-how-13583.html

- What Is Drug Repurposing? | Drug Repositioning – Oakwood Labs, accessed August 8, 2025, https://oakwoodlabs.com/what-is-drug-repurposing/

- Validation approaches for computational drug repurposing: a review – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10785886/

- Drug Repurposing: Engineering New Uses for Existing Medications – ResearchGate, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390389929_Drug_Repurposing_Engineering_New_Uses_for_Existing_Medications

- The Repositioning Revolution: Transforming Patent Data into Pharmaceutical Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/review-of-drug-repositioning-approaches-and-resources/

- How drug repurposing can advance drug discovery: challenges and opportunities – Frontiers, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/drug-discovery/articles/10.3389/fddsv.2024.1460100/full

- The Benefits and Pitfalls of Repurposing Drugs – PHETAIROS, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.phetairos.com/insights/integrated-product-development/the-benefits-and-pitfalls-of-repurposing-drugs/

- Drug repurposing: a systematic review on root causes, barriers and facilitators – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9336118/

- Turning Old Gold into New Revenue: Intellectual Property and Regulatory Considerations for Drug Repurposing – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/intellectual-property-rights-and-regulatory-considerations-for-drug-repurposing/

- Drug Repositioning via Graph Neural Networks: Identifying Novel JAK2 Inhibitors from FDA-Approved Drugs through Molecular Docking and Biological Validation – MDPI, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/29/6/1363

- AI in Drug Repurposing: Finding New Uses for Existing Medications – Astrix, accessed August 8, 2025, https://astrixinc.com/blog/ai-in-drug-repurposing-finding-new-uses-for-existing-medications/

- (PDF) Drug repositioning model based on knowledge graph embedding – ResearchGate, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390178218_Drug_repositioning_model_based_on_knowledge_graph_embedding

- Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in drug repurposing – challenges and perspectives, accessed August 8, 2025, https://drugrepocentral.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.58647/DRUGARXIV.PR000007.v1

- The Role of Academic Research in Generic Drug Development – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-role-of-academic-research-in-generic-drug-development/

- Drug Repurposing from an Academic Perspective – ResearchGate, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221864945_Drug_Repurposing_from_an_Academic_Perspective

- Drug Repurposing from an Academic Perspective – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3285382/

- Drug repositioning for orphan diseases | Briefings in Bioinformatics – Oxford Academic, accessed August 8, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/bib/article/12/4/346/241233

- Repurposing medicines: the opportunity and the challenges – LifeArc, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.lifearc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/LifeArc-Repurposing-digital_FINAL.pdf

- Q&A: How can drug repurposing lower drug costs and improve care? | Penn State University, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/qa-how-can-drug-repurposing-lower-drug-costs-and-improve-care

- Reviving Dormant Assets: A Strategic Blueprint for Drug Repurposing and Commercial Success – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/reviving-a-discontinued-drug/

- As good as new: why IP is central to repurposed drugs | Managing Intellectual Property, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.managingip.com/article/2a5bqo2drurt0bxl7aaus/as-good-as-new-why-ip-is-central-to-repurposed-drugs

- Intellectual Property in the Academic Setting | University of Michigan Medical School, accessed August 8, 2025, https://medresearch.umich.edu/office-research/about-office-research/our-units/fast-forward-medical-innovation/commercialization-education/intellectual-property-academic-setting

- Drug repurposing from an academic perspective – Scholars @ UT Health San Antonio, accessed August 8, 2025, https://scholars.uthscsa.edu/en/publications/drug-repurposing-from-an-academic-perspective

- The Roles Of Academia, Rare Diseases, And Repurposing In The Development Of The Most Transformative Drugs | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272083438_The_Roles_Of_Academia_Rare_Diseases_And_Repurposing_In_The_Development_Of_The_Most_Transformative_Drugs

- How much of new drug research is funded by the government compared to charities as well as pharmaceutical companies themselves? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 8, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/how-much-of-new-drug-research-is-funded-by-the-government-compared-to-charities-as-well-as-pharmaceutical-companies-themselves

- Introduction to Drug Repurposing for Rare Diseases – Saint John’s Cancer Institute, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.saintjohnscancer.org/translational-research-departments/current-research-topics/introduction-to-drug-repurposing-for-rare-diseases/

- Repositioning Drugs for Rare Diseases Based on Biological Features and Computational Approaches – MDPI, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/9/1784

- Drug Repurposing for Rare Diseases: A Role for Academia – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8564285/

- Increasing the Efficiency and Success of Repurposing – NCBI, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235866/

- Office of Technology Transfer – The Rockefeller University, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.rockefeller.edu/office-technology-transfer/

- Biotech & Pharma Program Prioritization | Tech Transfer – Alacrita, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/biotech-pharma-consulting-tech-transfer-offices

- Academic Commercialization | Pharma & Biotech Tech Transfer – Alacrita, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/academic-commercialization

- Enabling Tools and Technology – Drug Repurposing and Repositioning – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235869/

- The Drug Repurposing Ecosystem: Intellectual Property Incentives, Market Exclusivity, and the Future of “New” Medicines | Yale Journal of Law & Technology, accessed August 8, 2025, https://yjolt.org/drug-repurposing-ecosystem-intellectual-property-incentives-market-exclusivity-and-future-new

- Drug Repurposing from an Academic Perspective – PubMed, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22368688/

- Connecting academia and industry for innovative drug repurposing in rare diseases: it is worth a try – OAE Publishing Inc., accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.oaepublish.com/articles/rdodj.2023.06

- Drug repurposing from the perspective of pharmaceutical companies – PMC, accessed August 8, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5758385/

- Evaluating Performance of Drug Repurposing Technologies – bioRxiv, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.03.410274v1.full-text