I. Executive Summary

The landscape of biopharmaceutical innovation is profoundly shaped by the foundational and ongoing investments made by governments worldwide, particularly in the United States. This report delves into the indispensable role of public funding, tracing its historical evolution from wartime imperatives to its current position as the bedrock of scientific discovery. It quantifies the substantial economic and public health benefits derived from this investment, demonstrating a significant return on taxpayer dollars in terms of job creation, economic activity, and improved societal well-being.

However, this critical partnership is not without its complexities. The report examines prevailing challenges, notably the intricate balance between intellectual property rights and equitable access to medicines, the phenomenon of international “free-riding” on U.S. innovation, and the imperative of sustainable funding amidst policy volatility. Finally, it provides strategic insights for business and pharmaceutical audiences on how to leverage publicly available patent data for competitive advantage, highlighting the future trajectory of government involvement in emerging fields like AI, gene therapy, and personalized medicine. Ultimately, sustained public investment, coupled with a supportive policy environment and strategic private sector engagement, remains crucial for driving future biopharmaceutical advancements and ensuring global health security.

II. The Foundational Role of Government in Biopharmaceutical Innovation

Historical Context: Catalyzing Scientific Progress

The genesis of federal funding in biopharmaceutical innovation is deeply rooted in historical imperatives, particularly those arising from periods of national crisis and strategic foresight. This trajectory reveals a deliberate and evolving partnership between government and scientific enterprise, laying the groundwork for the robust ecosystem observed today.

From Wartime Imperatives to “Science, The Endless Frontier”: The Genesis of Federal Funding

The strong partnership between academic institutions and the U.S. government in scientific research was significantly spurred by the exigencies of World War II.1 This era demonstrated the critical need for coordinated scientific effort to address national challenges. Following the war, Vannevar Bush’s seminal 1945 report, “Science, The Endless Frontier,” articulated a compelling vision for science, particularly basic research, as the “pacemaker of technological progress”.1 This report was not merely an academic exercise; it provided a strategic roadmap for the U.S. scientific enterprise, emphasizing the crucial role of foundational research for national advancement and economic recovery in the post-war era.1

Early wartime research, such as the large-scale manufacturing of penicillin and the development of therapies for malaria, provided compelling evidence that even projects initially targeted at military efforts yielded “many results that were useful for civilian purposes”.1 This characteristic of research, where discoveries driven by specific missions find broad applicability across different sectors, highlights the inherent efficiency and versatility of basic scientific investment. Public funding for foundational research in areas like biology and chemistry, even when focused on defense, can underpin advancements across diverse fields, including critical public health benefits. For instance, DARPA’s Biological Technologies Office (BTO), with its defense mandate, has directly contributed to breakthroughs like mRNA technology, which proved pivotal in the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines.2 This demonstrates that continued broad-based public investment, extending beyond immediate, targeted commercial applications, is a strategic imperative.

The Evolution of Key Agencies: NIH’s Transformative Growth and Early FDA Oversight

In the wake of Bush’s recommendations, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) underwent a profound transformation. It evolved from a relatively small institution primarily conducting internal research into a major grant-making agency.1 This shift enabled the NIH to provide substantial funding for research and training at universities nationwide, even reimbursing institutions for the physical and administrative infrastructure necessary to support scientific endeavors.1 This structural change empowered U.S. researchers to make fundamental breakthroughs, deepening the understanding of how health and disease arise at molecular, cellular, and population levels.1

Concurrently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had already been established much earlier, in 1906, through the Pure Food and Drug Act.4 Its initial mandate was to enforce quality and safety standards for food, medicine, and cosmetics, a direct response to widespread public health crises and egregious industry practices of the time, such as the knowing sale of tainted meat.4 The FDA’s regulatory authority was significantly expanded with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FDC) Act of 1938, which strengthened oversight and, critically, mandated drug safety testing before marketing.4

These two government functions, funding and regulation, are not merely parallel efforts but are deeply interdependent and causally linked. While NIH’s funding fuels discovery, robust regulatory oversight by the FDA is essential for building public trust and ensuring that innovations are safe and effective. A historical example underscores this critical need: the faulty polio vaccine batches in the mid-1950s, which caused paralytic polio instead of preventing it, directly led to the establishment of rigid production controls and highlighted the vital role of regulatory agencies in ensuring public safety.6 Without this regulatory assurance, even the most groundbreaking scientific discoveries would struggle to gain market acceptance or achieve commercial viability. This illustrates that effective government involvement in biopharma innovation is a multi-pronged approach, encompassing both the “push” of R&D funding and the “pull” of a credible regulatory environment. This holistic approach is crucial for translating scientific breakthroughs into tangible public health benefits and sustainable commercial products.

Landmark Legislation: The Bayh-Dole Act and Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act

The year 1980 marked a pivotal moment with the enactment of two landmark pieces of legislation: the Bayh-Dole Act and the Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act. The Bayh-Dole Act, a bipartisan effort, fundamentally reshaped the intellectual property landscape by granting universities, small businesses, and non-profit research institutions the rights to intellectual property (IP) generated from federally funded research.7 Prior to this act, fewer than 4 percent of federally funded patents were ever licensed, indicating a significant bottleneck in commercialization.8 The primary intent of Bayh-Dole was to stimulate innovation by enabling the patenting and subsequent licensing of these discoveries to private-sector entities for commercial development.7 This act played a “catalytic role” in the life sciences, leading to a significant increase in academic patenting and the formation of thousands of advanced-technology start-up companies.7 For example, in the first two decades following Bayh-Dole’s introduction, U.S. universities experienced a tenfold increase in their patents and were responsible for creating over 2,200 companies to exploit their technology.9

Concurrently, the Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980 was passed as the first major U.S. technology transfer law.10 It mandated federal laboratories to actively engage in and budget for technology transfer activities, thereby facilitating the transfer of federal technologies to non-federal entities.10 This act also established Offices of Research and Technology Applications (ORTAs) within large federal laboratories to coordinate these efforts, ensuring a structured approach to moving innovations from government labs to the public and private sectors.10

These legislative acts represent a critical policy innovation that extended beyond simply providing R&D funding. By establishing clear IP ownership and mandating mechanisms for technology transfer, they provided the necessary incentives and a robust framework for the private sector to invest the substantial capital and effort required to develop early-stage, publicly funded discoveries into marketable products. This transformed the U.S. innovation ecosystem, effectively turning universities into “globally envied engines of innovation”.9 This demonstrates that the effectiveness of government as an investor is not solely dependent on the magnitude of financial input, but equally on the accompanying policy environment that facilitates the translation of basic science into commercial and societal value. The legal and policy infrastructure surrounding intellectual property and technology transfer is a crucial, often overlooked, component of the government’s role as a “first investor.”

Economic Rationale: Addressing Market Failures

The economic justification for government intervention in biopharmaceutical innovation primarily stems from inherent market failures that private enterprise alone cannot efficiently address.

Biopharmaceutical R&D as a Public Good: The Imperative for Public Investment

Biopharmaceutical innovations exhibit characteristics of a “public good”.12 The knowledge generated through research is non-rivalrous, meaning that its use by one party does not diminish its availability to others. It is also imperfectly excludable, requiring mechanisms like patents to prevent unauthorized copying.12 This combination creates a market failure where the private value of developing certain drugs, such as new antibiotics primarily important for reserve use, or treatments for diseases prevalent in lower-income countries, may be insufficient to incentivize private investment, despite their high social value.12

Government investment directly addresses this market failure by funding basic research and R&D in areas where private returns are uncertain or insufficient, but societal benefits are substantial.12 This is particularly evident in the case of “insurance value” of biopharmaceutical innovation. For example, the commercial market for new antibiotics is often described as “dismal by design” because their primary value lies in their reserve use to combat emerging resistance, rather than widespread, profitable sales.12 This creates a classic public-goods problem, where the benefits extend beyond the direct users or even national borders. This is further complicated by the global dynamic of “free-riding,” where the U.S. disproportionately finances global biopharmaceutical R&D. Evidence suggests that U.S. patients and taxpayers largely finance the international returns to medical R&D, with over 70 percent of patented pharmaceutical profits in OECD countries reportedly stemming from U.S. sales, despite the U.S. representing only about one-third of the OECD’s GDP.14 Many developed nations, particularly those with single-payer healthcare systems, implement stringent price controls that result in drug prices significantly lower (17-43% of U.S. prices) than in the United States.14 This practice effectively shifts the burden of innovation funding onto the U.S. market. This “free-riding” phenomenon reveals a complex, interconnected global system, almost a zero-sum game for R&D funding. When other nations suppress prices below market value, it reduces the overall global returns that incentivize pharmaceutical innovation, making the U.S. market subsidize global R&D. This dynamic can lead to underinvestment in globally needed drugs (especially if their primary markets are price-controlled) and potentially higher prices in the U.S. due to reduced competition.14 This underscores the need for international policy discussions on equitable burden-sharing for global health security, as domestic policy decisions have significant international ripple effects.

Mitigating Risk and Incentivizing Early-Stage Research

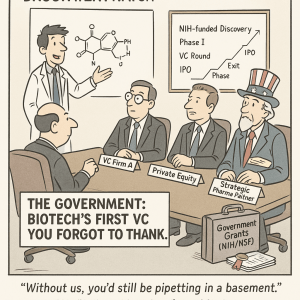

Biopharmaceutical research and development is characterized by extremely high costs, long development timelines (often exceeding a decade), and exceptionally high failure rates.5 Private companies are often unwilling to undertake the “extraordinary levels of risk” associated with developing novel platform technologies or products with uncertain commercial viability and profitability.16 This is where government funding plays a crucial role, acting as the “first investor” by absorbing the significant upfront risks associated with foundational and early-stage biomedical research.

This “de-risking” function is a critical economic incentive, making subsequent private sector investment (e.g., venture capital, pharmaceutical company R&D) more attractive and feasible. For example, NIH funding contributed to research associated with every new drug approved from 2010-2019, totaling $230 billion.17 This public investment effectively provides “cost savings to industry” of billions per approved drug, as demonstrated by studies showing NIH spending provided $2.9 billion in cost savings per approved drug, comparable to industry’s estimated $2.8 billion investment.18 By reducing the initial capital at risk, public funding enables private firms to pursue promising discoveries that might otherwise be deemed too speculative, thereby accelerating the translation of basic science into commercial products. This demonstrates a symbiotic relationship: public funds lay the scientific groundwork and de-risk the riskiest phases, while private capital then scales and commercializes the innovations. Any policy that makes federally funded inventions “toxic” for private investment, such as misapplying “march-in rights” for price control, could severely disrupt this crucial de-risking function and stifle the overall innovation pipeline.19

III. Economic Impact and Societal Returns of Public Investment

The government’s role as a primary investor in biopharmaceutical innovation extends far beyond mere financial allocation; it serves as a powerful engine for economic growth and a catalyst for profound public health improvements.

Key Government Funding Agencies and Mechanisms

A diverse array of federal agencies contributes to the biopharmaceutical innovation ecosystem, each with a distinct yet complementary mandate.

National Institutes of Health (NIH): Grant Mechanisms and Research Focus

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) stands as the largest public funder of biomedical and public health research in the U.S., allocating over $31 billion annually to more than 300,000 researchers across over 2,500 institutions.20 A significant portion, over 80%, of its budget supports extramural research through a variety of grant mechanisms.7 Key grant types include Research Grants (R series, such as the common R01 for discrete projects), Career Development Awards (K series), Research Training and Fellowships (T & F series), and Program Project/Center Grants (P series).20 The NIH also plays a vital role in developing the U.S. scientific and medical workforce through its training grants.7

A critical aspect of NIH’s contribution is its focus on foundational science. Approximately 90% of NIH-funded research related to drug discovery concentrates on the “discovery and characterization of pathways,” rather than direct drug development.20 This foundational research is remarkably impactful, having contributed to every new drug approved by the FDA from 2010-2019, with total NIH funding for this period reaching $230 billion.17 This demonstrates the “long tail” of basic research, where its impact is not immediately apparent but accumulates over decades, providing the fundamental scientific insights and targets that enable future drug discovery. This foundational knowledge is a non-depreciating asset that continues to yield benefits long after the initial investment. Furthermore, NIH’s investment in training grants directly cultivates the next generation of scientists and medical professionals 7, ensuring a continuous supply of human capital for the entire biopharmaceutical ecosystem. This illustrates that NIH’s role extends beyond funding specific drug projects; it builds the intellectual and human infrastructure that sustains the entire biopharmaceutical innovation pipeline. Consequently, cuts to basic research funding could have a delayed but profound negative impact on future innovation capacity.21

Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA): Countermeasure Development for Public Health Security

The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), operating under the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), adopts an integrated and systematic approach to the development and procurement of medical countermeasures (MCMs).22 These MCMs include essential vaccines, drugs, therapies, and diagnostic tools designed to address public health emergencies, encompassing chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats, pandemic influenza, and emerging infectious diseases.22

BARDA actively engages industry partners through various funding opportunities, such as Broad Agency Announcements (BAAs), Easy Broad Agency Announcements (EZ-BAAs), and Other Transaction Agreements.22 Notable BARDA-supported developments include therapeutics and vaccines for anthrax, botulism antitoxins, and significant funding contributions to the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccine candidates (e.g., AstraZeneca, Moderna) and the first Ebola vaccine, ERVEBO.24 BARDA’s role goes beyond traditional R&D funding; it actively “shapes” the market for products that private industry might otherwise underinvest in due to high development risk, uncertain demand, or low profitability.16 By providing funding, procurement mechanisms, and acting as a risk-sharing partner, BARDA creates a “pull” for innovation in areas vital for national security and public health preparedness. This demonstrates a strategic government intervention to address specific market failures related to public health emergencies. It highlights the importance of dedicated agencies that can bridge the gap between scientific possibility and commercial viability for products deemed essential for national resilience, even if they do not promise blockbuster returns.

Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and National Science Foundation (NSF): Pioneering Frontier Technologies

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), particularly its Biological Technologies Office (BTO), is renowned for funding “risky, visionary projects” that push the boundaries of current technologies.2 BTO leverages biological properties and processes, often integrating cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), to enhance warfighter protection and national security.2 A striking example of DARPA’s foresight is its funding of nucleic acid-based technologies

before the COVID-19 pandemic, which directly contributed to the rapid development of mRNA vaccines (e.g., Moderna’s mRNA-1273) and therapeutics (e.g., AbCellera/Eli Lilly’s bamlanivimab).2 BTO’s thrust areas, such as Data Factories (focused on simulating and predicting biological systems), Combat Casualty Care (developing medical countermeasures), and Logistics (creating resilient supply chains and point-of-need production capabilities), illustrate its broad impact.3

DARPA’s “extended pipeline” model of innovation, which focuses on outcomes and development beyond just early research, allows it to invest in foundational technologies with long lead times and uncertain applications.2 This “radical innovation” approach, even with a defense mandate, demonstrates a powerful mechanism for generating breakthroughs that can be rapidly repurposed for civilian health crises, as vividly seen with mRNA technology. The success of DARPA’s model has led to calls for an “ARPA-H” (Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health) 2, suggesting a future trend where this high-risk, mission-oriented funding approach could be more broadly applied to health challenges, potentially accelerating biomedical innovation and addressing gaps left by traditional market forces, while also raising questions about how to manage commercialization and profit-taking.2

The National Science Foundation (NSF) complements these efforts by providing hundreds of funding opportunities for fundamental research and education across a broad spectrum of science and engineering, including areas relevant to biomedical sciences.25 Collaborating with NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), NSF supports the “Science of Science Approach to Analyzing and Innovating the Biomedical Research Enterprise (SoS: BIO)” initiative.26 This program specifically examines policy impacts, collaboration mechanisms, and strategies for workforce diversity within biomedical research, highlighting the foundational role of interdisciplinary scientific inquiry.26

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Immunization and Public Health Infrastructure

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) plays a crucial and distinct role in the biopharmaceutical innovation pipeline, focusing on the implementation and public health impact of developed medical interventions. The CDC is fundamental to achieving national immunization goals and sustaining high vaccination coverage rates to prevent vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs).27 It provides non-competitive, formula-based funding to state, city, and territorial immunization programs, supporting essential operations such as ensuring vaccine access, promoting public awareness, and preparing for public health emergencies like pandemics or biological attacks.27

A cornerstone of the CDC’s efforts is the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, which, funded through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), offers no-cost vaccines to eligible children, thereby ensuring equitable access regardless of socioeconomic status.27 The CDC also funds public health departments and universities to strengthen the scientific basis for vaccine recommendations, enhance epidemiology and laboratory capacity for disease detection, and monitor vaccine safety and effectiveness.27 Its Partnering for Vaccine Equity (P4VE) program specifically targets improving vaccination coverage within disproportionately affected populations by engaging trusted messengers, holding vaccine clinics, and educating communities and healthcare providers.28

The CDC’s role is distinct and critical: it focuses on the “last mile” of biopharmaceutical innovation – ensuring that developed vaccines and public health interventions are effectively delivered, adopted, and monitored across the population, especially for vulnerable groups.28 This addresses market failures related to distribution, affordability, and health equity that are often not prioritized by profit-driven private ventures. This highlights that government investment spans the entire innovation lifecycle, from basic scientific discovery (NIH, DARPA) and countermeasure development (BARDA) to the crucial phase of public health implementation and equitable access (CDC). Without this “last-mile” investment, the full societal value of biopharmaceutical innovation cannot be realized, demonstrating the interconnectedness of different government roles.

Table 1: Key Government Agencies and Their Role in Biopharma R&D

| Agency Name | Primary Focus Area | Key Funding Mechanisms/Programs | Examples of Impact/Contribution |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | Basic Biomedical Research, Translational Science, Workforce Development | R01, K, T, F, P series grants, Research Program Projects, Training Grants, Cooperative Agreements | Foundational research for nearly all new drugs (2010-2019), discovery of fluoride, lithium for bipolar disorder, vaccines (Hepatitis, Hib, HPV), Alzheimer’s treatments, HIV prevention drugs, CRISPR discovery 7 |

| Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) | Medical Countermeasures for Public Health Emergencies | Broad Agency Announcements (BAAs), Easy BAAs (EZ-BAAs), Rapid Response Partnership Vehicle (RRPV), Other Transaction Agreements | Anthrax therapeutics/vaccines, Botulism antitoxins, significant funding for COVID-19 vaccine candidates (AstraZeneca, Moderna), first Ebola vaccine (ERVEBO) 22 |

| Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) / Biological Technologies Office (BTO) | High-Risk, Frontier Technologies, Warfighter Protection, Medical Countermeasures | BTO Thrust Areas (Data Factories, Combat Casualty Care, Logistics), specific programs (ABC, AWARE, AMPHORA) | Pre-pandemic funding of mRNA technology (Moderna, AbCellera/Eli Lilly), advanced anesthetics, alertness drugs, microbial preservation systems 2 |

| National Science Foundation (NSF) | Foundational Science and Engineering Research, Interdisciplinary Approaches | Smart Health and Biomedical Research in the Era of AI and Advanced Data Science (SCH), Science of Science Approach to Analyzing and Innovating the Biomedical Research Enterprise (SoS: BIO) | Supports basic research that underpins biomedical advancements, studies the innovation ecosystem, and fosters diverse talent pools 25 |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | Public Health Infrastructure, Immunization Programs, Disease Control & Prevention | Immunization Program funding for states, Vaccines for Children (VFC) Program, Partnering for Vaccine Equity (P4VE) | Polio eradication efforts, smallpox eradication, measles/Hib reduction, HIV interventions, vaccine equity initiatives, public health preparedness 6 |

Quantifying the Economic Multiplier Effect

The economic impact of government investment in biopharmaceutical research extends far beyond the direct allocation of funds, generating a substantial multiplier effect across the U.S. economy.

Job Creation and Contribution to U.S. GDP

NIH research funding serves as a significant economic catalyst, creating jobs and stimulating economic activity across the nation. In Fiscal Year 2024, the $36.94 billion awarded by NIH to researchers in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia supported 407,782 jobs and generated $94.58 billion in new economic activity nationwide.37 This translates to an impressive return of $2.56 for every $1 invested.37

Over the past decade, since Fiscal Year 2015, NIH funding has driven more than $787 billion in new economic activity and supported an average of over 370,000 jobs annually.37 This demonstrates that the economic impact of government investment in biopharma is not merely a direct return on expenditure but functions as a systemic economic engine. The multiplier effect illustrates that public funding generates a cascading series of economic benefits, from direct job creation and the purchase of research-related goods and services to indirect support for local businesses as income cycles through the economy.37 This ultimately contributes to the broader growth of the life sciences sector. The U.S. biomedical industry, significantly underpinned by NIH-funded research, contributes over $69 billion to the U.S. GDP each year and supports over 7 million jobs.40 This positions government investment in biopharma not just as a healthcare expenditure, but as a crucial component of national economic strategy and competitiveness. It suggests that sustained investment is vital for maintaining U.S. leadership in global life sciences and for fostering a robust innovation ecosystem that benefits all states.38

Return on Investment (ROI) in Biomedical Research

The long-term economic benefits of government biomedical research funding are substantial, yielding significant returns that compound over time. Early econometric studies conducted in 2000 estimated an annual rate of return of 25-40% from NIH research, primarily through reducing the economic cost of illness in the U.S..30 More recently, an analysis covering a 16-year period (2007-2022) revealed that $46 billion in U.S. public funding for global health R&D generated a projected six-fold return on investment for the American economy, ultimately contributing $255 billion.41 This public funding also spurred an additional $102 billion in industry investments, demonstrating its catalytic effect on private capital.41

The high return on investment demonstrated by these studies is a testament to the long-term, compounding nature of public investment in basic biomedical research. Unlike short-term commercial investments, foundational scientific discoveries continue to generate new knowledge, inspire further research, and attract subsequent private investment for decades. This enduring value, often described as a “gift that keeps on giving” 41, highlights the sustained benefits of early-stage public funding. This challenges a short-term, transactional view of R&D funding and underscores the critical need for sustained, predictable public investment.39 Erratic funding or deep cuts could jeopardize this compounding return, ultimately costing society more in lost innovation and health benefits in the long run.21

Table 2: Economic Impact of NIH Funding (FY2024 Data)

| Metric | Value (FY2024) | Source |

| NIH Funding Awarded | $36.94 billion | 37 |

| Jobs Supported | 407,782 jobs | 37 |

| New Economic Activity Generated | $94.58 billion | 37 |

| Return on Investment (per $1 invested) | $2.56 | 37 |

| Cumulative Economic Activity (since FY2015) | Over $787 billion | 37 |

| Cumulative Jobs Supported (average since FY2015) | Over 370,000 jobs/year | 37 |

| Contribution to U.S. GDP (Biomedical Industry) | Over $69 billion annually | 40 |

| Total Jobs Supported (Biomedical Industry) | Over 7 million jobs | 40 |

Public Health Benefits: Improving Lives and Reducing Disease Burden

The most direct and profound societal returns from government investment in biopharmaceutical innovation are observed in the dramatic improvements in public health, including disease eradication, control, and enhanced quality of life.

Impact on Disease Eradication and Control

Government-funded research has been central to monumental public health achievements, fundamentally altering the trajectory of numerous diseases. Smallpox, once a global scourge, has been eradicated entirely, and wild-type poliovirus has been eliminated from the Western Hemisphere.36 Other vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles and

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) invasive disease among children, have seen their case numbers reduced to record lows.36 The NIH, for instance, contributed to the development of vaccines against hepatitis, Hib, and human papillomavirus (HPV).30

Beyond vaccines, government-backed research has transformed the management of chronic and infectious diseases. NIH-funded research informed HIV testing and interventions, leading to over a 90% decrease in the number of U.S. children infected with HIV at birth.42 HIV has been transformed from a death sentence into a manageable chronic disease 42, with new prevention drugs like lenacapavir, developed using evidence from NIH-funded research, demonstrating 100% prevention in clinical trials.33 This illustrates the “preventative power” of government-funded biomedical research, a critical and often underestimated societal return. By preventing diseases, these investments not only save countless lives and improve quality of life but also significantly reduce the long-term economic burden on healthcare systems and increase societal productivity. For example, ending smallpox in the U.S. cost over $100 million but saved an estimated $1.35 billion annually.43 This shifts the paradigm from costly reactive treatment to cost-effective proactive prevention, reinforcing the argument for sustained government funding in public health and vaccine R&D as a strategic investment in national resilience and long-term economic well-being.

Reduction in Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and Gains in Life Expectancy

To quantify the comprehensive impact of disease, public health research often utilizes Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). DALYs combine years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs), providing a holistic measure of disease burden.44 The overarching goal of public health interventions is to minimize DALYs, reflecting a desire to maximize healthy life years.44

Significant reductions in DALYs have been observed for various diseases due to government-funded interventions. Global DALYs attributable to communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS and diarrheal diseases dropped by over 50% between 2000 and 2021.47 Furthermore, NIH-supported research is credited with many of the gains in U.S. health and longevity over the past century, with average life expectancy nearly doubling since 1900.42 Cancer deaths, for instance, have dropped by 29% over 30 years, partly due to NIH-funded improvements in treatment, detection, and prevention.42 This underscores that reducing DALYs and increasing life expectancy are not just humanitarian achievements but also direct economic benefits. Healthier populations are more productive, contribute more to the economy, and reduce the strain on healthcare systems.42 This is particularly crucial as populations age and the burden of chronic diseases increases.42 Quantifying health improvements via metrics like DALYs provides a powerful economic justification for continued public investment in biomedical research. It demonstrates that these investments yield significant returns in terms of avoided healthcare costs, increased workforce participation, and overall societal well-being, making it a strategic imperative for national prosperity.

Table 3: Examples of Government-Funded Drugs and Vaccines and Their Impact

| Drug/Vaccine Name | Disease/Condition Treated | Key Government Agency/Funding Source | Brief Description of Impact |

| Polio Vaccine | Polio | March of Dimes (public donations, later government support for implementation), CDC | Eliminated wild-type poliovirus from Western Hemisphere, reduced cases by 99% globally 6 |

| Smallpox Vaccine | Smallpox | CDC | Global eradication of smallpox 36 |

| Hepatitis Vaccines (various) | Hepatitis | NIH | Prevention of hepatitis infections 30 |

| Hib Vaccine | Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) invasive disease | NIH, CDC | Nearly eliminated Hib invasive disease among children 30 |

| HPV Vaccine | Human Papillomavirus (HPV) | NIH | Prevention of HPV-related cancers 30 |

| HIV Prevention Drugs (e.g., Lenacapavir, Truvada) | HIV | NIH | Transformed HIV from death sentence to manageable chronic disease; 100% prevention in trials for Lenacapavir, >90% decrease in pediatric HIV infections 33 |

| Taxol | Cancer (e.g., breast, ovarian, lung) | NIH (National Cancer Institute) | One of 34 federally funded cancer drugs marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb 51 |

| Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) | Hepatitis C | NIH | First-in-class product, improved lives of tens of thousands 34 |

| Xeljanz (tofacitinib) | Arthritis | NIH | First-in-class product, improved lives of tens of thousands 34 |

| Eylea (aflibercept) | Macular Degeneration | NIH | First-in-class product, improved lives of tens of thousands 34 |

| Kalydeco (ivacaftor) | Cystic Fibrosis | NIH | First-in-class product, improved lives of tens of thousands 34 |

| CRISPR-based therapies (e.g., for Sickle Cell Disease) | Sickle Cell Disease | NIH, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, CMS | Foundational research on CRISPR discovered via NIH funding; federal program expanding access to gene therapies for sickle cell 32 |

| Anthrax Therapeutics/Vaccines | Anthrax | BARDA | Supported development of antibiotics (XERAVA, ZEMDRI, Gepotidacin, SPR994), antitoxins (Anthrasil, Anthim), and vaccines (BioThrax, AV7909, Px563L, NasoShield) 24 |

| COVID-19 Vaccines (e.g., Moderna, AstraZeneca, Pfizer-BioNTech) | COVID-19 | BARDA (Operation Warp Speed), DARPA | Rapid development and deployment of vaccines; DARPA funded foundational mRNA technology pre-pandemic 2 |

| ERVEBO (Ebola vaccine) | Ebola | BARDA | First Ebola vaccine, successfully used in outbreaks 24 |

IV. Challenges and Policy Debates in Public-Private Partnerships

While government investment is undeniably critical to biopharmaceutical innovation, the public-private partnership model faces significant challenges and ongoing policy debates, particularly concerning intellectual property, global economic dynamics, and funding sustainability.

Intellectual Property (IP) and Access Concerns

The framework governing intellectual property, while designed to incentivize innovation, has become a focal point of contention, especially regarding drug pricing and equitable access.

The Bayh-Dole Act: Balancing Innovation Incentives with Public Access

The Bayh-Dole Act, instrumental in stimulating the commercialization of federally funded IP, has concurrently become a central point of debate concerning drug pricing and equitable access to medicines.7 The Act’s original intent was to encourage the practical application of inventions by granting IP rights to research institutions, not to control drug prices.7 However, critics argue that the IP protections granted under Bayh-Dole allow pharmaceutical companies to charge “excessive drug prices” for products developed with significant taxpayer funding.15 This creates a tension between its original goal of fostering commercialization and the societal demand for affordable access to medicines. While IP protection is crucial for incentivizing risky private investment, a system where publicly funded foundational research yields private monopolies with high prices, disproportionately benefiting wealthy nations, is perceived by some as unjust.15 This highlights a fundamental policy dilemma: how to design IP frameworks that effectively incentivize innovation while simultaneously ensuring broad and equitable access to life-saving medicines. This tension necessitates ongoing policy adjustments and exploration of alternative models, such as compulsory licensing, tiered pricing, or public-private partnerships, to achieve both goals.15

The “March-in Rights” Controversy and Drug Pricing Debates

A specific provision of the Bayh-Dole Act, “march-in rights,” allows federal agencies to require a patent holder to license an invention if it is not being “practically applied” or if public health needs are not being met.7 Advocates for lower drug prices frequently argue for using these march-in rights to compel licensing when drug prices are deemed too high, citing the substantial public funding that underpins the R&D.15 However, successive U.S. administrations, including the current one, have consistently rejected this interpretation, asserting that the Act was not intended for drug price control.7

Opponents of using march-in rights for price control warn that such an application would “undermine the U.S. life-sciences innovation ecosystem,” make federally funded inventions “toxic” for investors, and consequently reduce the pace of American biopharmaceutical innovation, leading to fewer new drugs.7 They also point out that most drugs are protected by multiple patents, with only a few typically linked to Bayh-Dole inventions, limiting the practical impact of such a measure on overall drug pricing.19 This illustrates a direct causal relationship: policy uncertainty or perceived overreach regarding intellectual property rights can create a “chilling effect” on private sector investment. While the government aims to ensure public benefit, an expansive interpretation of march-in rights to control prices could inadvertently deter the very private capital needed to bring early-stage, publicly funded discoveries through the costly and risky development phases to market. This highlights the delicate balance policymakers must strike between ensuring public access and maintaining incentives for private innovation. Misinterpreting or misapplying foundational legislation like Bayh-Dole could inadvertently undermine the successful public-private partnership model that has driven U.S. biopharmaceutical leadership.

Global Dynamics: Free-Riding and International Price Controls

The global nature of biopharmaceutical innovation introduces complex dynamics, particularly concerning the distribution of R&D costs and benefits. U.S. patients and taxpayers disproportionately finance global biopharmaceutical R&D. Data indicates that over 70% of patented pharmaceutical profits in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries reportedly stem from U.S. sales, even though the U.S. accounts for only about one-third of the OECD’s gross domestic product (GDP).14

Many developed nations, particularly those with single-payer healthcare systems, implement stringent price controls that result in drug prices significantly lower (ranging from 17% to 43% of U.S. prices) than those in the United States.14 This practice is often described as “free-riding” on U.S. investment in innovation.14 This “public-goods problem,” where domestic taxation funds international benefits, can lead to a slower pace of overall innovation and reduced competition from new entrants, indirectly contributing to higher prices in the U.S..14 This “free-riding” phenomenon reveals a complex, interconnected global system, almost a zero-sum game for R&D funding. When other nations suppress prices below market value, it reduces the overall global returns that incentivize pharmaceutical innovation, effectively making the U.S. market subsidize global R&D. This dynamic can lead to underinvestment in globally needed drugs (especially if their primary markets are price-controlled) and potentially higher prices in the U.S. due to reduced competition.14 This underscores the need for international policy coordination and a re-evaluation of how the costs and benefits of global biopharmaceutical innovation are equitably distributed among nations.

Funding Sustainability and Policy Volatility

Despite the proven benefits, the sustainability of government funding for biopharmaceutical research faces persistent challenges. Despite bipartisan support and significant budget growth (over $17 billion since FY2015), the NIH’s purchasing power remains below 2003 levels due to biomedical inflation, enabling it to fund only about one in five research proposals.42 Furthermore, federal funding of university research as a share of GDP declined by 18% from 2011 to 2021.9

Industry experts express significant concern that “deep cuts” to the budgets of NIH, FDA, and NSF, coupled with “rapid-fire policy and regulatory change” and general “policy turbulence,” are directly impacting basic research and early-stage clinical science.21 These foundational stages are considered the “bedrock of healthcare innovation”.21 Such factors create “significant challenges and uncertainties” for industry growth and innovation timelines.21 This presents a “paradox of success”: the very effectiveness of past government investment in biopharma has led to an expectation of continuous innovation, yet there is a discernible trend of underinvestment in the foundational research that makes future breakthroughs possible. This creates “policy volatility” where short-term budget considerations or political shifts can have long-term, detrimental effects on the innovation pipeline and U.S. global leadership. The long lead times inherent in biomedical R&D mean that the negative impacts of current underinvestment will only become apparent years or even decades later, potentially undermining national health security and economic competitiveness. This highlights the need for a long-term, stable, and inflation-adjusted funding commitment to maintain the momentum of biomedical innovation.

Ethical Considerations in Research and Development

Beyond economic and policy challenges, the government’s role in biopharmaceutical innovation also intersects with profound ethical considerations. The debate over prioritizing equitable access to pharmaceuticals versus protecting intellectual property rights is a complex and contentious ethical issue.15 At its core, this debate balances the humanitarian goal of ensuring affordable, widespread access to essential medicines against the economic incentives and legal protections that allow pharmaceutical companies to profit from their research and development investments.15

Arguments for prioritizing access emphasize it as a “moral imperative” and a fundamental human right, positing that expanded access yields significant public health and economic benefits from wider availability.15 Conversely, arguments for strong IP protections highlight their necessity for incentivizing the long, costly, and inherently risky process of drug development.15 This illustrates a fundamental tension between the “moral imperative” of equitable access to medicines and the “economic reality” of incentivizing innovation.

Ethical considerations also extend to specific research areas. For instance, the NIH maintains a strict policy against funding human embryo genome editing due to ethical concerns and existing legal prohibitions, such as the Dickey-Wicker amendment.32 This demonstrates the government’s role in navigating complex ethical landscapes while fostering scientific advancement.

V. Leveraging Patent Data for Competitive Advantage

For businesses and pharmaceutical companies, understanding and strategically leveraging patent data, particularly concerning government-funded research, is a critical component of competitive intelligence and market leadership.

Identifying Government-Funded Inventions

Patent databases offer a rich source of information for identifying inventions that have received government funding. Public data from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), a primary source for platforms like PatentsView, often contain “government interest statements”.56 These statements are required for any patent granted by the USPTO for inventions funded, at least in part, by a federal research grant, government contract, or other government support.56 These standardized clauses, typically placed at the beginning of the patent document, can be easily identified through text searches using USPTO databases.57 They often include federal contract and grant identifiers, allowing for direct tracing of federal contributions to biomedical innovation.57

Commercial databases, such as DrugPatentWatch, provide an integrated platform for accessing this and other critical information.58 These platforms incorporate data directly from the FDA, USPTO, and other U.S. and foreign government sources, offering comprehensive and regularly updated insights.58 Users can perform detailed searches using various criteria, including active ingredient, proprietary (trade) name, applicant (company name), patent number, therapeutic area, and even chemical structures (e.g., IUPAC names, CAS numbers, structural formulas).59 The ability to filter and sort search results, set up email alerts, and export data further enhances their utility for competitive intelligence.58

Strategic Competitive Intelligence Applications

Leveraging government-funded patent data provides a powerful lens for strategic competitive intelligence, offering insights into competitor activities, market opportunities, and risk mitigation.

Monitoring Competitor R&D Pipelines and Market Entries

Systematically monitoring and analyzing drug patent filings provides an “early warning system” for competitive threats.61 Patent applications typically become public 18 months after filing, creating a valuable intelligence opportunity to understand competitor activities years before products reach the market or enter clinical trials.61 By tracking new patent filings in specific therapeutic areas, companies can gain unprecedented insights into competitor research directions, technological innovations, and potential market entries.61 This intelligence allows organizations to make informed decisions about their own R&D investments, potentially redirecting resources to more promising or less crowded therapeutic areas. It also facilitates more accurate forecasting of market dynamics and competitive landscapes.61 This includes monitoring shifts in target selection, emerging modalities (e.g., transitions from small molecules to biologics), evolving approaches to mechanisms of action, and changes in formulation or manufacturing technologies.61

Identifying White Space Opportunities and Licensing

Patent analysis is not solely about identifying threats; it is also a powerful tool for discovering new opportunities. By mapping the patent landscape, companies can identify “white space” opportunities – therapeutic targets with limited patent coverage, delivery approaches not yet claimed for specific indications, or novel applications of existing technologies with minimal protection.60 This strategic analysis can reveal untapped markets or areas ripe for innovation. Furthermore, patent databases can help identify potential licensing opportunities, including expired patents that might open up new possibilities for generic entry or new product development.60

Informing IP Strategy and Risk Mitigation

A thorough understanding of patent claims, filing and expiration dates, and the legal status of patents is crucial for assessing patent strength, identifying potential infringement risks, and ensuring freedom-to-operate for pipeline products.59 Competitive intelligence derived from patent data informs strategic decisions that mitigate risks and enhance business outcomes.62 By proactively identifying potential threats, companies can develop defensive strategies, such as patent challenges or invalidation opportunities, and create contingency plans for market entry by competitive products.61 This proactive approach, grounded in detailed patent analysis, is fundamental to maintaining a competitive edge in the highly capital-intensive and innovation-driven biopharmaceutical sector.63

Future Trends and Policy Implications

The trajectory of government investment in biopharmaceutical innovation is continually evolving, driven by technological advancements and shifting global health priorities.

Government Initiatives in AI, Gene Therapy, and Personalized Medicine

Governments are increasingly recognizing and investing in transformative technologies that promise to reshape biopharmaceutical discovery and treatment. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acknowledges the growing use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) throughout the drug product lifecycle, from nonclinical and clinical phases to post-marketing and manufacturing.65 The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) has established an AI Council to coordinate activities, develop policy initiatives, and ensure consistency in evaluating AI’s role in drug safety, effectiveness, and quality.65 This indicates a proactive stance by regulators to build a risk-based framework that promotes innovation while protecting patient safety.65

Government funding is also significantly impacting the burgeoning field of gene therapy. NIH-funded basic research led to the discovery of CRISPR gene editing technology.32 NIH continues to support human gene therapy research for various diseases, including through targeted efforts like the Somatic Cell Genome Editing Program and the Cure Sickle Cell Initiative.32 Collaborations, such as that between NIH and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, are advancing gene-based approaches for diseases like sickle cell and HIV.32 Furthermore, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has launched initiatives, like the Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model, to help states pay for high-cost gene therapies, potentially broadening access for patients with conditions like sickle cell disease.53 This model, which includes outcomes-based agreements, shifts financial risk to manufacturers and could expand to other high-cost therapies.53

Personalized medicine initiatives, aimed at tailoring treatments to individual patients, are also receiving substantial government backing. The Personalized Medicine Coalition (PMC) advocates for robust and sustained funding increases for biomedical research at NIH and regulatory oversight programs at FDA to drive personalized medicine tests and treatments to market.66 NIH’s Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI) Cohort Program aims to collect extensive data from over a million U.S. volunteers to transform the understanding of health and disease, with a focus on individualized care.67 This initiative also emphasizes critical policy themes such as data sharing, privacy, and consent, with efforts to develop innovative technological solutions like advanced cryptography to protect health data.68

Beyond these, government initiatives in synthetic biology are also on the rise, with agencies like DARPA, the Department of Energy (DOE), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) investing in designing and adapting biological systems for various applications, including biomanufacturing and new naval capabilities.70 NIST, for example, focuses on developing measurement science, standards, and reference data to support the biopharmaceutical industry in delivering high-quality, low-cost protein drugs and biosimilars.71

Pandemic Preparedness and Global Health Security

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the critical importance of government investment in biopharmaceutical R&D for rapid response to global health threats. Organizations like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) are global partnerships working to accelerate the development of vaccines and other biologic countermeasures against epidemic and pandemic threats.73 CEPI is leading ambitious programs to reduce global epidemic and pandemic risk, focusing on research and development, manufacturing and supply chain bolstering, and equitable access.73

International organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), CEPI, and Gavi (the Vaccine Alliance) play key roles in pandemic preparedness, vaccine development, and distribution.74 Their synergistic collaboration, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 response, is crucial for improving accessibility to vaccines and strengthening the global response to infectious diseases.74 A key future trend is the push for a “100 Days Mission” to accelerate vaccine development and the need for balanced vaccine platform development, investing in both novel technologies like mRNA and traditional platforms to efficiently address emerging infectious diseases and increase manufacturing capabilities for future pandemics.73

Evolving Regulatory Landscape and International Collaboration

The regulatory landscape for biopharmaceuticals is continuously evolving, with governments adapting to new technologies and global challenges. The FDA’s posture is dynamic, with potential for new regulatory pathways and a willingness to “shake up the status quo”.21 There is also an increasing emphasis on international collaboration and the importance of feedback from regulatory bodies like the European Medicines Agency (EMA).21

Furthermore, there is a growing push for domestic manufacturing and supply chain resilience in the biopharmaceutical sector, driven by policy considerations and geopolitical tensions.21 This aims to mitigate dependencies on foreign inputs and products, particularly from rivals.75 Finally, the global nature of health threats and the “free-riding” phenomenon underscore the ongoing need for international policy coordination on R&D funding and intellectual property policies to ensure that the costs and benefits of biopharmaceutical innovation are equitably distributed among nations, thereby fostering a more robust and resilient global health security framework.

VI. Conclusion

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that government serves as the indispensable “first investor” in biopharmaceutical innovation, laying the foundational scientific and economic groundwork upon which the entire industry thrives. This role, born from wartime necessity and formalized through landmark legislation, addresses critical market failures by de-risking early-stage, high-uncertainty research that would otherwise not attract sufficient private capital. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collectively form a multifaceted ecosystem that drives discovery, develops countermeasures, pioneers frontier technologies, and ensures equitable public health implementation.

The returns on this public investment are profound and far-reaching. Economically, NIH funding alone generates a significant multiplier effect, supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs and billions in economic activity annually, with a return of $2.56 for every dollar invested. This positions government investment not merely as a healthcare expenditure but as a powerful engine for national economic growth and competitiveness. From a public health perspective, government-funded research has been instrumental in eradicating diseases like smallpox, controlling polio and HIV, and significantly reducing the overall burden of illness, translating directly into longer, healthier, and more productive lives for citizens.

However, this vital partnership faces persistent challenges. The ongoing debate surrounding intellectual property rights, particularly the “march-in rights” under the Bayh-Dole Act, highlights a fundamental tension between incentivizing innovation and ensuring equitable access to life-saving medicines. The phenomenon of international “free-riding” on U.S. investment further complicates the global landscape, underscoring the need for more equitable burden-sharing in funding global health R&D. Moreover, concerns about funding sustainability and policy volatility threaten the long-term health of the innovation pipeline, as underinvestment in foundational research today will inevitably manifest as a deficit in breakthroughs tomorrow.

For business and pharmaceutical leaders, a strategic understanding of this dynamic landscape is paramount. Leveraging publicly available patent data, particularly government interest statements, offers a powerful tool for competitive intelligence, enabling companies to monitor competitor R&D pipelines, identify white space opportunities, and inform their own IP strategies. Looking ahead, continued government investment in cutting-edge areas like AI, gene therapy, and personalized medicine, coupled with efforts in pandemic preparedness and supply chain resilience, will shape the future of the industry.

In conclusion, maintaining U.S. leadership in biopharmaceutical innovation and ensuring global health security necessitates a conscious and sustained commitment to public investment. This requires policymakers to strike a delicate balance between fostering robust private sector incentives and upholding the public interest in access and affordability. For industry, this means actively engaging with public research initiatives, strategically utilizing available data, and advocating for stable, long-term government funding that recognizes its indispensable role as the first, and often most critical, investor.

Works cited

- A Brief History of Federal Funding for Basic Science | Harvard Medicine Magazine, accessed July 25, 2025, https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/brief-history-federal-funding-basic-science

- Expanding DARPA’s model of innovation for biopharma: – UCL Discovery, accessed July 25, 2025, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/10196078/1/Mazzucato_mazzucato_m._and_whitfill_t._2022._expanding_darpas_model_of_innovation_for_biopharma_a_proposed_advanced_research_projects_agency_for_health.pdf

- Biological Technologies Office – DARPA, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.darpa.mil/about/offices/bto

- The Food and Drug Administration: the Continued History of Drug Advertising | Weill Cornell Medicine Samuel J. Wood Library, accessed July 25, 2025, https://library.weill.cornell.edu/about-us/snake%C2%A0oil%C2%A0-social%C2%A0media-drug-advertising-your-health/food-and-drug-administration-continued

- How Does Government Regulation Impact the Drug Sector? – Investopedia, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/032315/how-does-government-regulation-impact-drugs-sector.asp

- Polio and The Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) | David J. Sencer CDC Museum, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/museum/online/story-of-cdc/polio/index.html

- The Bayh-Dole Act’s Vital Importance to the U.S. Life-Sciences Innovation System | ITIF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2019/03/04/bayh-dole-acts-vital-importance-us-life-sciences-innovation-system/

- The Bayh-Dole Act and the Debate Over “Reasonable Price” March-In Rights, accessed July 25, 2025, https://fedsoc.org/commentary/fedsoc-blog/the-bayh-dole-act-and-the-debate-over-reasonable-price-march-in-rights

- The Bayh-Dole Act’s Role in Stimulating University-Led Regional Economic Growth | ITIF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/16/bayh-dole-acts-role-in-stimulating-university-led-regional-economic-growth/

- Stevenson–Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980 – Wikipedia, accessed July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stevenson%E2%80%93Wydler_Technology_Innovation_Act_of_1980

- From Lab to Liberty: How Tech Transfer Fuels America’s Innovation Economy | TechLink, accessed July 25, 2025, https://techlinkcenter.org/news/from-lab-to-liberty-how-tech-transfer-fuels-america-s-innovation-economy

- A Litany of Market Failures: Diagnosing and Solving the Economic Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance | Center For Global Development, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/litany-market-failures-diagnosing-and-solving-economic-drivers-antibiotic-resistance

- (PDF) Economic rationales of government involvement in innovation and the supply of innovation-related services – ResearchGate, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24133814_Economic_rationales_of_government_involvement_in_innovation_and_the_supply_of_innovation-related_services

- Funding the Global Benefits to Biopharmaceutical Innovation | Trump White House Archives, accessed July 25, 2025, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Funding-the-Global-Benefits-to-Biopharmaceutical-Innovation.pdf

- Equitable access to pharmaceuticals should be prioritized over protecting intellectual property rights (IPPF) – DebateUS, accessed July 25, 2025, https://debateus.org/equitable-access-to-pharmaceuticals-should-be-prioritized-over-protecting-intellectual-property-rights-ippf/

- Is it time for big biopharma companies to rethink the use of federal funding for R&D?, accessed July 25, 2025, https://blog.freshfields.us/post/102hh1q/is-it-time-for-big-biopharma-companies-to-rethink-the-use-of-federal-funding-for

- Government as the First Investor in Biopharmaceutical Innovation: Evidence From New Drug Approvals 2010-2019 – ResearchGate, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344045651_Government_as_the_First_Investor_in_Biopharmaceutical_Innovation_Evidence_From_New_Drug_Approvals_2010-2019

- New study shows NIH investment in new drug approvals is comparable to investment by pharmaceutical industry – Bentley University, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.bentley.edu/news/new-study-shows-nih-investment-new-drug-approvals-comparable-investment-pharmaceutical

- The March-In Drug Price Control Narrative Crumbles While Its Damage to American Innovation Grows – IPWatchdog.com, accessed July 25, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2024/01/29/march-drug-price-control-narrative-crumbles-damage-american-innovation-grows/id=172495/

- NIH grant – Wikipedia, accessed July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NIH_grant

- The Future of Healthcare Innovation 2025 – Cure, accessed July 25, 2025, https://wewillcure.com/insights/healthcare-innovation-report

- BARDA Funding – EverGlade Consulting, accessed July 25, 2025, https://everglade.com/funding-opportunity-areas/life-sciences/barda-funding/

- Center for the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development …, accessed July 25, 2025, https://aspr.hhs.gov/AboutASPR/ProgramOffices/BARDA/Pages/default.aspx

- Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority – Wikipedia, accessed July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biomedical_Advanced_Research_and_Development_Authority

- Funding at NSF | NSF – National Science Foundation, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.nsf.gov/funding

- Science of Science Approach to Analyzing and Innovating the Biomedical Research Enterprise (SoS:BIO) | NSF, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/dcl-science-science-approach-analyzing-innovating-biomedical

- State Immunization Profiles, accessed July 25, 2025, https://vaccines.cdc.gov/

- Partnering for Vaccine Equity (P4VE) Program – CDC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-equity/php/about/index.html

- Government as the First Investor in Biopharmaceutical Innovation – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/government-as-the-first-investor-in-biopharmaceutical-innovation/

- National Institutes of Health – Wikipedia, accessed July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Institutes_of_Health

- Comparison of Research Spending on New Drug Approvals by the National Institutes of Health vs the Pharmaceutical Industry, 2010-2019, accessed July 25, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10148199/

- Gene Editing – National Institutes of Health (NIH) |, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/digital-media-kits/gene-editing

- The Best Investment You Didn’t Know You Made: How NIH Funding Fuels Innovation and Economic Growth, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.amfar.org/nih-funding-infographic

- NIH funding provides the core foundation for new drugs – CommonWealth Beacon, accessed July 25, 2025, https://commonwealthbeacon.org/opinion/nih-funding-provides-the-core-foundation-for-new-drugs/

- Our Impact | Global Health – CDC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/global-health/about/our-impact.html

- Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999 Impact of Vaccines Universally Recommended for Children — United States, 1990-1998 – CDC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00056803.htm

- NIH research funding supported over 400000 jobs and $94B in U.S. economy, accessed July 25, 2025, https://harpercancer.nd.edu/news-events/news/nih-research-funding-supported-over-400-000-jobs-and-94b-in-u-s-economy/

- NIH funding delivers exponential economic returns – Harvard Gazette, accessed July 25, 2025, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2025/03/nih-funding-delivers-exponential-economic-returns/

- UMR Releases Annual NIH Economic Impact Report: 2025 Update, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.unitedformedicalresearch.org/statements/umr-releases-annual-nih-economic-impact-report-2025-update/

- www.nih.gov, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/impact-nih-research/serving-society/spurring-economic-growth#:~:text=Discoveries%20arising%20from%20NIH%2Dfunded,supports%20over%207%20million%20jobs.

- New Report Finds Public Spending on Global Health Innovation Delivers Blockbuster Returns, Saving Lives While Generating Billions of Dollars in Benefits Globally and Domestically, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.ghtcoalition.org/news/new-report-finds-public-spending-on-global-health-innovation-delivers-blockbuster-returns-saving-lives-while-generating-billions-of-dollars-in-benefits-globally-and-domestically

- Medical research saves lives – Act For NIH, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.actfornih.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ACT-for-NIH-Fact-Sheet_Apr23.pdf

- Most Important Vaccines in History | Online Masters in Public Health – University of Southern California, accessed July 25, 2025, https://mphdegree.usc.edu/blog/most-important-vaccines-in-history

- DALYs in Mortality and Public Health Research – Number Analytics, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/dalys-in-mortality-and-public-health-research

- Understanding Summary Measures Used to Estimate the Burden of Disease: All about HALYs, DALYs and QALYs, accessed July 25, 2025, https://nccid.ca/publications/understanding-summary-measures-used-to-estimate-the-burden-of-disease/

- Determinants of life-expectancy and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in European and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries: A longitudinal analysis (1990–2019), accessed July 25, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10480329/

- Global health estimates: Leading causes of DALYs, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/global-health-estimates-leading-causes-of-dalys

- Health care expenses impact on the disability-adjusted life years in non-communicable diseases in the European Union – Frontiers, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1384122/full

- GPEI-Historical Contributions – Polio Eradication Initiative, accessed July 25, 2025, https://polioeradication.org/donors-financing/historical-contributions/

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis | HIV.gov, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/hiv-prevention/using-hiv-medication-to-reduce-risk/pre-exposure-prophylaxis

- Federally Funded Pharmaceutical Inventions – CPTech, accessed July 25, 2025, http://www.cptech.org/pharm/pryor.html

- Treating rare diseases: the challenge of orphan drugs – POST Parliament, accessed July 25, 2025, https://post.parliament.uk/treating-rare-diseases-the-challenge-of-orphan-drugs/

- New Federal Program Expands Access to Gene Therapies for Sickle Cell and More – Cure, accessed July 25, 2025, https://wewillcure.com/insights/cell-and-gene-therapeutics/federal-gene-therapy-program-expands-access-sickle-cell

- CRISPR Therapeutics Receives Grant to Advance In Vivo CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing Therapies for HIV, accessed July 25, 2025, https://crisprtx.com/about-us/press-releases-and-presentations/crispr-therapeutics-receives-grant-to-advance-in-vivo-crispr-cas9-gene-editing-therapies-for-hiv

- 33 states pick up CMS program to pay for sickle cell gene therapies | Healthcare Dive, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/medicaid-sickle-cell-gene-therapy-payment-program/753251/

- Government Interest | Methods & Sources – PatentsView, accessed July 25, 2025, https://patentsview.org/government-interest

- Late disclosures of federal funding in US patents – PMC, accessed July 25, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12152413/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed July 25, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- Decode a Drug Patent Like a Wall Street Analyst – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-check-if-a-drug-is-patented/

- The basics of drug patent searching – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-basics-of-drug-patent-searching/

- How to Track Competitor R&D Pipelines Through Drug Patent Filings – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-track-competitor-rd-pipelines-through-drug-patent-filings/

- Role of Competitive Intelligence in Pharma and Healthcare Sector – DelveInsight, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.delveinsight.com/blog/competitive-intelligence-in-healthcare-sector

- 7 Ways to Collect Competitive Intelligence in Pharma – BiopharmaVantage, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.biopharmavantage.com/effectively-collecting-competitive-intelligence-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- Patent research as a tool for competitive intelligence in brand protection – RWS, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.rws.com/blog/patent-research-as-a-tool/

- Artificial Intelligence for Drug Development – FDA, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/artificial-intelligence-drug-development

- Government Funding & Appropriations – The Personalized Medicine Coalition, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org/policy_category/government-funding-appropriations/

- Precision Medicine Initiative | The White House, accessed July 25, 2025, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/precision-medicine

- Data Sharing For Precision Medicine: Policy Lessons And Future Directions – Health Affairs, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1558

- Changing the Culture on Data Management and Sharing: Overview and Highlights from a Workshop Held by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, accessed July 25, 2025, https://hdsr.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/p1xu0son

- Agencies – Interagency Synthetic Biology Working Group (SBWG) | NSF – National Science Foundation, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.nsf.gov/sbwg/agencies

- Biomanufacturing Initiative | NIST, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/biomanufacturing-initiative

- U.S. Government Funding Boosts Synthetic Biology Research – Innovations Report, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.innovations-report.com/health-life/life-sciences/government-funding-synthetic-biology-rise-155953/

- CEPI: Home page, accessed July 25, 2025, https://cepi.net/

- Exploring Future Pandemic Preparedness Through the Development of Preventive Vaccine Platforms and the Key Roles of International Organizations in a Global Health Crisis – MDPI, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/13/1/56

- Remarks by Director Kratsios at the Endless Frontiers Retreat – The White House, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/2025/04/remarks-by-director-kratsios-at-the-endless-frontiers-retreat/