For decades, the pharmaceutical world revolved around a predictable axis: the triad of North America, Europe, and Japan. These regions were the undisputed arenas of innovation, the primary sources of revenue, and the focal points of corporate strategy. But the ground beneath our feet is moving. A new world order is taking shape, and the once-peripheral markets—the sprawling, dynamic, and complex economies of Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East—are no longer a secondary consideration or a mere footnote in an annual report. They have become the new epicenter of growth, a powerful engine driving the future of global health.

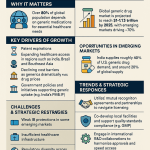

This is not a cyclical trend; it is a “structural, irreversible transformation”. Projections indicate that emerging markets will be the primary engine of global pharmaceutical sales growth in the coming decade, potentially contributing as much as 90% of the world’s pharmaceutical growth, with a significant proportion (75%) stemming from branded generics. For business leaders and strategists in the pharmaceutical and life sciences sectors, understanding, adapting to, and ultimately capitalizing on this revolution is not just an opportunity for growth—it is a prerequisite for survival.

At the heart of this transformation lies the generic drug. More than just a low-cost copy, the generic medicine is the single most powerful tool for expanding healthcare access, bending the cost curve for strained health systems, and meeting the needs of billions of new healthcare consumers. Yet, its path is anything but simple. The journey of a generic drug into an emerging market is a gauntlet of complex regulatory mazes, fierce intellectual property battles, and deep-seated logistical challenges. Perhaps most profoundly, it is a battle for trust in markets where the line between a life-saving medicine and a dangerous counterfeit can be perilously thin.

This report will dissect the multifaceted role of generic medicines in these critical markets. We will move beyond the headlines to explore the intricate machinery of the generic industry, from the rigors of the regulatory approval process to the high-stakes chess match of patent litigation. We will unpack the complex barriers that still prevent medicines from reaching those who need them most and analyze the staggering economic and public health dividends that generics deliver when those barriers are overcome. Through in-depth case studies—from the triumph over HIV/AIDS in Africa to the rise of India as the “pharmacy of the world”—we will illuminate the on-the-ground realities of this global shift.

As one industry observer noted, “The era of relying solely on blockbuster sales in developed nations is fading, eclipsed by a more complex, multipolar world where the next wave of growth will be captured by those who can master the art and science of succeeding in emerging markets”. This report is your guide to mastering that art and science. For those looking to turn data into a competitive advantage, the message is clear: the future of pharmaceuticals is being written in the emerging world, and generics hold the pen.

Section 1: The Bedrock of Global Health: Deconstructing Generics and Emerging Markets

To grasp the strategic imperatives of the global pharmaceutical landscape, we must first establish a common understanding of its foundational elements. What exactly is a generic drug, and what defines the diverse, dynamic, and often paradoxical healthcare systems of emerging markets? Answering these questions reveals a world of nuance far beyond simple definitions, exposing the regulatory rigors, economic pressures, and unique opportunities that shape this new frontier.

What is a Generic Drug? More Than Just a Copy

It’s easy to dismiss a generic drug as a mere “copy” of a brand-name medicine, but this simplification dangerously understates the scientific and regulatory rigor involved in its creation. A generic drug is a pharmaceutical product that is clinically equivalent to an innovator, or brand-name, drug that has already been proven safe and effective. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), whose standards often serve as a global benchmark, defines a generic as being identical or bioequivalent to a brand-name drug in dosage form, safety, strength, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use.

The cornerstone of this equivalence is a concept known as bioequivalence. This is the scientific proof that the generic medicine delivers the same amount of its active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream over the same period as the reference listed drug (RLD), or brand-name version.3 To gain approval, a generic manufacturer must conduct studies, typically in a small group of 24 to 36 healthy volunteers, who take both the generic and brand-name products. Blood samples are then analyzed to compare key pharmacokinetic parameters, ensuring that a patient can be switched from the brand to the generic without any change in therapeutic effect.5

The FDA mandates that a generic drug must meet several stringent criteria to be considered substitutable :

- Same Active Ingredient: The core component that provides the therapeutic effect must be identical to that of the brand-name drug.

- Same Strength and Dosage Form: If the brand is a 500 mg tablet, the generic must be a 500 mg tablet.

- Same Route of Administration: An oral brand-name drug must have an oral generic counterpart.

- Same Use Indications: It must be approved to treat the same conditions.

- Same Batch Quality Standards: It must be manufactured under the same strict standards of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) required for brand products.

Where generics can differ is in their inactive ingredients, such as fillers, binders, flavors, and colors. However, these differences are not arbitrary. The generic manufacturer must prove that these inactive ingredients are safe and do not affect how the drug works in the body.6 U.S. trademark laws often prevent a generic drug from looking exactly like its brand-name counterpart, which accounts for these variations in appearance. This very difference, however, can become a source of patient and physician skepticism—a psychological barrier that we will explore as a critical challenge to generic adoption in many markets.

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): A Streamlined but Rigorous Pathway

The regulatory pathway for generic drugs is designed to be more efficient than the one for innovator drugs, but the term “abbreviated” should not be mistaken for “easy” or “less rigorous.” Innovator companies must conduct extensive and costly preclinical (animal) and clinical (human) trials over many years to prove a new drug is both safe and effective, submitting a New Drug Application (NDA) for approval.

Generic manufacturers, by contrast, submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). The ANDA is “abbreviated” because it doesn’t require the generic company to repeat the large-scale clinical trials already conducted for the brand-name drug. Instead, it leverages the FDA’s prior finding that the innovator product is safe and effective.3 This streamlined process is the primary reason generics can be offered at a much lower cost.

However, the ANDA process is still a meticulous and data-intensive undertaking. The FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) conducts a thorough review to ensure the generic is a true therapeutic equivalent. The ANDA dossier must contain comprehensive evidence demonstrating 6:

- Manufacturing and Controls: Detailed data on how the drug will be made, proving the manufacturer can reliably produce a high-quality product batch after batch.

- Bioequivalence (BE): The results of the BE studies proving the generic is substitutable with the brand-name drug.

- Stability: Data from months-long “stability tests” to show the generic will not deteriorate over time and lasts at least as long as the brand product.

- Labeling: The drug’s label must be the same as the brand-name medicine’s label, though it can omit uses that are still protected by patents.

FDA scientists review this mountain of data, and FDA inspectors visit the manufacturing facilities to verify that the company is capable of making the drug correctly and consistently. Only after this rigorous process is a generic drug approved. This system ensures that when patients in the U.S. fill a prescription—an event that involves a generic drug about 9 out of 10 times—they can be confident in its quality and efficacy.

Defining the Landscape: What Are “Emerging Markets” in Healthcare?

Just as “generic” is a term with a precise definition, “emerging market” is a concept that requires careful unpacking, especially in the context of healthcare. There is no single, official definition. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) identifies them based on a combination of attributes like sustained market access, progress toward middle-income levels, and growing global economic relevance. The BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) are the quintessential examples, but the list also includes countries like Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey, Thailand, and Saudi Arabia.9

For the pharmaceutical strategist, however, an economic definition is insufficient. We must look at the specific characteristics of their healthcare systems, which are often a landscape of paradoxes:

- The Demand Dichotomy: Many emerging countries face a split personality in healthcare demand. On one hand, a rapidly growing, affluent middle class is demanding Western-style, high-quality care in upscale private facilities. On the other, the vast majority of the population relies on rudimentary, often under-resourced public healthcare systems.

- The Dual Disease Burden: These nations are simultaneously battling the infectious diseases of the developing world (like tuberculosis and malaria) and the chronic, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) of the developed world (like diabetes, hypertension, and cancer). This places an enormous and complex strain on their health systems.

- The Funding Gap: While health spending is growing much faster in emerging economies than in developed ones, it is often growing from a very low base. A significant portion of healthcare expenses is paid directly by patients. In many of these countries, medicines account for a staggering 20% to 60% of total health expenditures, and it’s estimated that nearly 90% of people in developing nations buy their medication out-of-pocket. This heavy reliance on OOP payments can lead to catastrophic financial consequences for families, pushing an estimated 100 million people into extreme poverty each year.

This complex environment—marked by rapid growth, deep inequality, and constrained resources—is the crucible in which the role of generic medicines is being forged.

The Paradox of Potential: Strengths and Weaknesses of Emerging Healthcare Systems

It would be a strategic error to view the healthcare systems of emerging markets as simply lagging behind their developed counterparts. In fact, their lack of established infrastructure creates a unique opportunity. As the World Economic Forum notes, emulating the development paths of mature health systems is “neither feasible nor desirable” because it is too expensive, too slow, and leads to the same pitfalls of inefficiency and sustainability challenges that plague systems in the West today.

Instead, emerging economies are positioned to “leapfrog” over these arduous stages. They possess several key advantages :

- They can learn from the past mistakes of more developed economies.

- They are less burdened by “path dependencies, sunk costs and vested interests,” giving them more freedom to reform and innovate.

- They have access to a host of technological and organizational innovations that can help them build better, more efficient systems from the ground up.

This “leapfrogging” potential is most evident in the rapid adoption of technology. While physical infrastructure like roads and reliable electricity may be lacking, mobile penetration is often high. This has led to a greater openness to information and communication technology (ICT)-based services to bridge access gaps. Mobile health platforms, telemedicine consultations, and big data analytics are not just novelties; they are becoming essential tools for healthcare delivery. A survey of healthcare organizations across emerging markets found that a remarkable 76% were planning heavy investment in big data and analytics capacity.

This creates a fascinating dynamic. The very weakness of a market—its poor physical infrastructure—becomes a catalyst for strength in digital innovation. For a pharmaceutical company, this means a traditional go-to-market strategy focused on brick-and-mortar hospitals and pharmacies is dangerously incomplete. The real opportunity lies in understanding how to integrate a product into these new, tech-enabled delivery channels. It requires a shift in thinking from pure product sales to channel innovation, exploring partnerships with mHealth platforms, logistics-tech startups, and government digital health initiatives. This approach turns a market liability into a powerful competitive advantage, allowing a company to reach patients where traditional distribution networks fail.

The following table provides a snapshot of the diverse healthcare landscapes across several key emerging markets, highlighting the data points a strategist must consider when evaluating market potential and crafting a localized entry strategy.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Healthcare Systems in Key Emerging Markets

| Indicator | India | Brazil | China | South Africa | Indonesia |

| Population (2023 est.) | ~1.43 Billion | ~216 Million | ~1.43 Billion | ~60 Million | ~278 Million |

| GDP per capita (USD, 2023 est.) | ~$2,600 | ~$8,900 | ~$13,000 | ~$6,700 | ~$5,000 |

| Health Expenditure (% of GDP) | ~3.0% | ~9.6% | ~5.4% | ~8.4% | ~3.1% |

| Out-of-Pocket Expenditure (% of health spending) | ~48% | ~28% | ~27% | ~14% | ~35% |

| Physician Density (per 10,000 pop.) | ~9.3 | ~23 | ~24 | ~9.1 | ~7 |

| Hospital Bed Density (per 10,000 pop.) | ~15 | ~22 | ~43 | ~23 | ~12 |

| Health Insurance Coverage (%) | <20% (private/govt schemes) | ~75% (public), ~25% (private) | >95% (public) | ~16% (private), public access for all | ~91% (public) |

Sources: Data compiled from World Bank, WHO, IMF, and cited research. Figures are approximate and intended for comparative purposes.

This table immediately reveals the strategic trade-offs. A market like China or Indonesia, with high insurance coverage, demands a strategy focused on government tenders and payer negotiations. In contrast, a market like India, with high out-of-pocket spending, requires a direct-to-consumer approach centered on affordability and brand trust. A low bed density, as seen in India and Indonesia, underscores the infrastructure gaps and reinforces the need for innovative, non-facility-based delivery models. This data-driven, comparative view is the essential first step in moving from a generic “emerging market strategy” to a specific, actionable, and ultimately successful plan.

Section 2: The Great Divide: Unpacking the Barriers to Medicine Access

The promise of modern medicine is immense, yet its reach remains tragically limited. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a staggering one-third of the global population lacks regular access to essential medicines. In the poorest regions of Africa and Asia, this figure climbs to over 50%. For any pharmaceutical company aiming to operate in these markets, understanding the obstacles that create this great divide is not just a matter of corporate social responsibility; it is a core business imperative. Ignoring these barriers leads to failed market entries, wasted investment, and missed opportunities.

Beyond the Price Tag: A Multi-Layered Problem

It is tempting to view the problem of access through a single lens: price. While the affordability of medicines is undoubtedly a critical barrier, focusing on it exclusively is a strategic mistake. The reality is a complex, multi-layered puzzle. As Novartis aptly puts it, the issues of price and intellectual property are just two “pieces of the puzzle.” Expanding access requires a holistic view that considers the broader societal context, including poverty, inadequate public health services, and a lack of healthcare personnel and infrastructure.

A comprehensive framework for understanding these barriers must look at the entire system. The challenges can be broadly categorized into five interconnected domains: economic, regulatory, infrastructure and supply chain, quality and trust, and socio-political factors. Success in emerging markets hinges on developing strategies that address each of these layers, not just the one that appears most obvious.

The Economic Chasm: Affordability and Financing

At the most fundamental level, economics remains a formidable barrier. In countries where a large portion of the population lives in poverty, even low-cost generic medicines can be prohibitively expensive. This is compounded by the structure of healthcare financing in many emerging markets. Unlike developed nations with robust insurance systems, many of these countries have a high reliance on out-of-pocket (OOP) payments. This means the financial burden of illness falls directly on individuals and their families.

The scale of this problem is immense. The Geneva Association estimates a cumulative “health protection gap” of around $310 billion annually for all emerging markets, equivalent to 1% of their combined GDP. This gap represents the OOP spending that pushes families into financial hardship. The WHO estimates that about 100 million people are driven into extreme poverty each year because they have to pay for healthcare themselves.

This economic reality is exacerbated by chronic underfunding of the public health sector by national governments. In 2001, African Union countries signed the Abuja Declaration, pledging to allocate at least 15% of their annual budgets to health. More than two decades later, many countries have yet to meet this target. This lack of public investment perpetuates the cycle of weak infrastructure and high OOP spending, making the affordability proposition of generic drugs more critical than ever.

The Regulatory Labyrinth: A Barrier to Entry and Supply

Even when a generic drug is affordable, it cannot reach patients if it cannot get into the country. The regulatory systems in many emerging markets present a significant labyrinth of challenges that can stifle competition and disrupt supply.

One of the most common and frustrating hurdles for generic manufacturers is the “reference product” dilemma. To approve a generic, a national regulatory authority (NRA) typically requires the generic company to prove its product is bioequivalent to the innovator drug that is registered and sold in that country. However, in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the originator company may have never bothered to register or market its product, leaving no local reference for comparison. This creates a catch-22. For example, in South Africa, the lack of registration for the originator Hepatitis C drug daclatasvir has hindered the approval of its affordable generic versions, even though WHO-prequalified generics exist. While mechanisms like the WHO’s Collaborative Registration Procedure exist to bypass this issue, they are not always utilized by under-resourced or inflexible NRAs.

Other regulatory and administrative hurdles include:

- Inefficient Registration Processes: Many NRAs are understaffed and lack the capacity to review dossiers in a timely manner, leading to long delays in market entry.

- Lack of Harmonization: Different countries have different data requirements and dossier formats, forcing manufacturers to prepare unique submissions for each market, which is costly and time-consuming.

- Procurement and Payment Issues: For companies selling to public health systems, the risk of delayed or incomplete payments from government agencies is a major concern. This can disrupt the continuous supply of medicines and make companies reluctant to bid on new tenders or introduce new products into high-risk countries.

The Crisis of Trust: Quality Perceptions and the Scourge of Falsified Medicines

Perhaps the most insidious and underestimated barrier to generic adoption is the crisis of trust. In many emerging markets, there is a deep-seated perception among both patients and healthcare providers that generic medicines are inferior in quality to their branded counterparts. A common belief is that “the more you pay, the better the quality”. This perception leads to a preference for more expensive branded drugs, even when high-quality, affordable generics are available.

This mistrust is not entirely unfounded. It is fueled by the very real and dangerous problem of substandard and falsified (SF) medicines. A landmark systematic review published in JAMA Network Open found that the median prevalence of SF medicines in LMICs was a shocking 13.6%. For critical drugs like antimalarials, the rate was even higher at 19.1%. These poor-quality products can be ineffective at best and deadly at worst, containing the wrong ingredients, no active ingredient, or toxic contaminants. The circulation of these products not only harms patients directly but also erodes public trust in the entire healthcare system, including legitimate manufacturers and healthcare professionals.

This creates a vicious cycle: the presence of fake drugs fuels mistrust in all low-cost medicines, which in turn drives patients who can afford it toward expensive brands, further fragmenting the market and making it harder for legitimate generic companies to gain traction.

For a generic manufacturer, this reality transforms the nature of competition. The fight is no longer just about price. It becomes a fight to establish and defend trust. This requires a strategic shift and investment in activities that go far beyond traditional marketing. A successful market entry strategy must include a robust “trust-building” component. This might involve:

- Proactive Quality Signaling: Prominently featuring approvals from Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRAs) like the U.S. FDA or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) on packaging and in marketing materials to signal a global standard of quality.

- Local Stakeholder Engagement: Partnering with local medical associations, key opinion leaders (KOLs), and pharmacist groups to provide education on the science of bioequivalence and the specific quality control measures used for their products.

- Supply Chain Integrity: Investing in secure, modern supply chains with technologies like serialization and track-and-trace to prevent counterfeits from infiltrating their distribution channels and to visibly demonstrate a commitment to product security.

This reframes the competitive landscape. A company that successfully builds a brand synonymous with quality and reliability can command greater market share and potentially a price premium over less-trusted competitors. In these markets, trust is not a soft metric; it is a hard asset and a critical pillar of any sustainable business model.

The following table provides a structured overview of these key barriers and outlines potential strategic solutions, offering a framework for risk assessment and planning.

Table 2: Key Barriers to Medicine Access and Potential Solutions

| Barrier Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Access | Potential Solution / Strategic Response |

| Economic | High out-of-pocket (OOP) spending; Low public health budgets. | Patients cannot afford medicines, leading to non-adherence or forgoing treatment. Health systems cannot procure enough medicine for the population. | Implement tiered/differentiated pricing strategies based on country income levels. Advocate for increased government health spending. Explore public-private financing models. |

| Regulatory | Inefficient registration; Lack of a local reference product; Non-harmonized standards. | High-quality, affordable generics are delayed or blocked from entering the market. Increased cost and complexity for manufacturers. | Invest in local regulatory affairs expertise. Utilize WHO collaborative registration pathways. Advocate for regional regulatory harmonization. |

| Quality & Trust | Prevalence of substandard and falsified (SF) medicines; Negative perceptions of generics. | Patients and prescribers prefer expensive brands, undermining generic uptake. Poor health outcomes from SF drugs erode trust in the entire system. | Market SRA approvals (FDA/EMA). Invest in secure supply chains (track-and-trace). Engage in education campaigns with local healthcare professionals. |

| Infrastructure & Supply Chain | Weak logistics; Poor storage facilities (cold chain); “Last-mile” delivery challenges. | Medicines are damaged or fail to reach remote and rural populations. Increased risk of stockouts and supply disruptions. | Partner with specialized logistics providers. Invest in modern warehousing and cold chain solutions. Explore innovative delivery models (e.g., drones, mobile clinics). |

| Socio-Political | Lack of political will; Corruption; Cultural beliefs and preference for traditional medicine. | Health is not prioritized in national budgets. Procurement processes are compromised. Patients may not seek modern medical care. | Engage in transparent public-private partnerships. Adhere to strict anti-corruption policies. Partner with community leaders and NGOs for health education. |

Section 3: The Economic and Public Health Calculus of Generic Medicines

The introduction of generic medicines into a healthcare system is not merely an act of providing a cheaper alternative; it is a powerful economic and public health intervention. The ripple effects of generic competition extend far beyond the pharmacy counter, creating a virtuous cycle of savings, expanded access, and improved health outcomes. However, this engine of value is not without its own complexities and pressures. Understanding both the profound benefits and the potential instabilities of generic markets is crucial for any stakeholder seeking to harness their power.

The Economic Multiplier: How Generics Drive Savings and Sustainability

The most direct and quantifiable impact of generics is their ability to generate massive cost savings. By forgoing the immense research and development costs borne by innovator companies, generic manufacturers can offer their products at prices that are typically 80% to 85% lower than their brand-name equivalents. When this price reduction is applied across millions of prescriptions, the aggregate savings are staggering.

While comprehensive data from many emerging markets is scarce, the mature markets of the United States and Europe provide a clear illustration of the economic power of generics.

- In the U.S., the generic and biosimilar industry saved the healthcare system a record $373 billion in a single year (2021).

- In Europe, generics account for 70% of the volume of medicines dispensed but represent only 19% of the total pharmaceutical expenditure.

- The savings from a single blockbuster drug going generic can be immense. When generic versions of the cholesterol-lowering drug atorvastatin (Lipitor) entered the U.S. market, the price per pill dropped from $4 to 20 cents, leading to an estimated annual savings of $2.9 billion on that one drug alone.

This dramatic price reduction is a direct function of market competition. Economic studies consistently show that prices fall as more generic competitors enter a market. The entry of the first few generics typically leads to a modest price drop, but as the number of competitors grows, the price plummets. Research from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services shows that prices decline by approximately 20% with about three competitors, but can fall by 70% to 80% relative to the pre-generic price in markets with ten or more competitors.

In 2022, it was estimated that 91% of all prescriptions in the United States were filled as generic drugs. However, those prescriptions accounted for only 18.2% of the country’s spending on prescription drugs. This stark contrast highlights the immense economic leverage of generics in containing healthcare costs, a model with profound implications for budget-constrained emerging markets.

Citation: Association for Accessible Medicines, “2022 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report” ; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Generic Drug Competition and Price”.

For emerging markets, where healthcare budgets are severely constrained and out-of-pocket spending is high, these savings are not just an economic benefit—they are a lifeline. The cost containment provided by generics allows governments to stretch their limited resources further, making their entire healthcare system more sustainable.

The Public Health Dividend: Expanding Treatment and Improving Outcomes

The economic savings generated by generics translate directly into a powerful public health dividend. Lower costs break down the primary barrier to access for millions of people, leading to tangible improvements in health outcomes.

The most significant impact is the expansion of treatment. When the cost of a drug drops by 80% or more, health systems can afford to treat many more patients with the same budget. This has been most dramatically demonstrated in the fight against major infectious diseases in developing nations. The WHO has highlighted how the availability of affordable generics was instrumental in scaling up access to treatments for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.

Furthermore, affordability has a direct impact on medication adherence. For patients with chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension who require lifelong treatment, high costs can lead to rationing medication or stopping treatment altogether, resulting in poor disease control and costly complications. The lower out-of-pocket expenses associated with generics make it easier for patients to stick to their prescribed regimens, leading to better health outcomes and a reduction in long-term healthcare costs. In India, for example, the widespread availability of low-cost generics for chronic diseases has been credited with significantly improving public health outcomes.

Ultimately, the savings from generics free up resources that can be reallocated to other critical areas of the health system, such as preventative care, diagnostics, health worker training, or infrastructure improvements. In this way, generics act as an economic engine that fuels broader public health progress.

A Double-Edged Sword: Market Instability and Supply Chain Pressures

While the benefits of generic competition are clear, it is crucial to recognize that the generic market is not a perfectly stable commodity landscape. The very force that drives down prices—intense competition—can also create a “race to the bottom” that leads to market instability, drug shortages, and, in some cases, quality concerns.

The idea of the generic market as a simple, competitive space is an “oversimplification”. The economic realities of generic manufacturing can be harsh. Companies incur significant one-time costs to develop a product and get it approved, and ongoing fixed costs to maintain manufacturing facilities. In markets for high-volume oral solids, there are often enough competitors to ensure robust price competition. However, in smaller markets or for more complex products like sterile injectables, the profit margins can become so thin that they deter entry or force existing manufacturers to exit the market.

This can lead to dangerous market concentration. An analysis in the U.S. found that between 2004 and 2016, a staggering 40% of generic drug markets were supplied by a single manufacturer. When a market has only one or two suppliers, it becomes highly vulnerable. Any manufacturing problem, quality issue, or business decision to cease production at a single facility can trigger a nationwide shortage.

These supply chain pressures are magnified by the globalized nature of pharmaceutical production. The heavy reliance on a few countries, particularly India and China, for both active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and finished drugs creates systemic risk. Any disruption in these key regions—be it from natural disasters, geopolitical tensions, or new regulatory actions—can have immediate and severe consequences for drug supply around the world, disproportionately affecting critical medicines like antibiotics and cancer therapies. This dynamic presents a double-edged sword: while globalization has enabled low-cost production, it has also created a more fragile and less resilient supply chain. For health systems and companies alike, managing the risk of shortages has become as important as managing price.

Section 4: The Strategic Gauntlet: Navigating Market Entry and Intellectual Property

For a generic drug company, the path to market is a strategic gauntlet. It is a high-stakes journey that requires not only scientific expertise in formulation and manufacturing but also a deep understanding of the complex and often contentious world of intellectual property (IP) law. The global IP framework, the defensive strategies of innovator companies, and the aggressive counter-moves of generic challengers create a dynamic battlefield where fortunes are won and lost. Navigating this landscape successfully is the difference between a profitable market entry and a costly failure.

The Global IP Framework: Understanding TRIPS and Its Flexibilities

The foundation of modern pharmaceutical IP law is the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). Enacted in 1995, the TRIPS Agreement requires all WTO member countries, including developing nations, to provide a minimum standard of IP protection. For the pharmaceutical industry, the most critical provision is the mandate for 20 years of patent protection for all inventions, including new medicines and the processes to make them.30

This 20-year period of market exclusivity allows innovator companies to recoup their substantial R&D investments by selling their products without direct competition, often at high prices. For many developing countries, the implementation of TRIPS was a seismic shift. India, for example, had operated under a “process patent” system since 1970, which allowed local companies to legally produce a patented drug as long as they used a different manufacturing process. The shift to “product patents” under TRIPS, which protects the molecule itself regardless of how it’s made, was a fundamental change to the business model that had made India the “pharmacy of the world”.32

However, the TRIPS agreement is not an ironclad monolith. Recognizing the potential for patent monopolies to conflict with public health needs, the agreement includes several crucial “flexibilities.” The most important of these, affirmed in the 2001 Doha Declaration on Public Health, is the right of countries to grant compulsory licenses. A compulsory license allows a government to authorize the production of a patented drug by a third party (such as a generic company) without the consent of the patent holder, typically in cases of national emergency or to ensure access to essential medicines. A landmark 2003 WTO decision further clarified that countries with insufficient manufacturing capacity could import generics made under a compulsory license in another country, addressing a key gap for the poorest nations. These flexibilities represent a critical tool for governments to balance IP protection with their duty to protect public health.

The Innovator’s Playbook: Brand Defense and “Patent Evergreening”

Innovator companies do not passively wait for their 20-year patents to expire. They employ a range of sophisticated and often controversial strategies to defend their monopolies and extend their profitability for as long as possible. This practice, known as “lifecycle management,” often involves a strategy called “patent evergreening”.

Evergreening is the practice of obtaining numerous secondary patents on minor modifications of an existing drug to create a “patent thicket” that delays or blocks generic competition long after the original patent on the active molecule has expired. These secondary patents can cover a wide range of incremental changes, such as 37:

- New Formulations: Changing a drug from a tablet to a capsule, or developing a new extended-release version.

- New Methods of Use: Patenting the use of the drug for a new medical indication.

- New Dosages: Patenting a different strength of the drug.

- Combinations: Combining the drug with another existing active ingredient.

While supporters argue that evergreening encourages continuous innovation and product improvement, critics contend that it stifles meaningful competition, keeps drug prices artificially high, and shifts the industry’s focus from risky, breakthrough R&D to low-risk, highly profitable tweaking of existing products.36

The real-world impact of evergreening is stark:

- Prilosec and Nexium: AstraZeneca famously engaged in “product hopping” by introducing Nexium, a slightly modified version of its blockbuster heartburn drug Prilosec, just as Prilosec’s patent was expiring. They then heavily marketed Nexium to physicians and patients, effectively migrating the market to a new, patent-protected product and extending its monopoly.

- Imatinib (Gleevec): In a landmark 2013 decision, India’s Supreme Court denied a secondary patent to Novartis for a new crystalline form of its cancer drug imatinib. The court ruled that the new form did not demonstrate enhanced efficacy and therefore was not a sufficient invention to warrant a new patent. This decision was a major victory for access to medicines, preserving the availability of much cheaper generic versions in India and other developing countries.

- HIV and Opioid Addiction Drugs: Many widely prescribed medicines have been heavily evergreened. Johnson & Johnson’s HIV drug Prezista and Gilead’s Truvada have been protected by over 100 patents and other exclusivities each, extending their market dominance by more than 16 years. Indivior’s Suboxone, used to treat opioid addiction, gained over 16 years of additional market protection through just 11 protections.

The Generic’s Counter-Move: Patent Intelligence and Strategic Market Entry

Faced with these formidable defensive strategies, a generic company cannot simply wait for a patent to expire. It must proactively engage in a strategic counter-offensive, and the most critical weapon in its arsenal is patent intelligence.

The journey to a successful generic launch begins long before an ANDA is filed. The first and most crucial step is strategic drug selection. This involves a multifaceted analysis of a potential target drug, including its market size, its regulatory history, and, most importantly, its complete patent and exclusivity landscape.

This is where specialized patent intelligence platforms become indispensable. To navigate the dense “patent thickets” created by evergreening, a generic firm must meticulously dissect every patent associated with a brand-name drug. Services like DrugPatentWatch provide the critical data needed for this analysis. They consolidate information from sources like the FDA’s Orange Book, patent office databases, and court records, allowing a company to :

- Identify all relevant patents and their expiration dates.

- Assess the strength and validity of secondary, “evergreening” patents.

- Monitor ongoing patent litigation involving other generic challengers.

- Pinpoint the optimal timing for a market launch to minimize legal risk and maximize commercial opportunity.

This intelligence forms the bedrock of the Paragraph IV (PIV) certification strategy. Under the U.S. Hatch-Waxman Act, when a generic company files an ANDA, it must make a certification for each patent listed for the brand-name drug. A PIV certification is a bold declaration that the generic company believes its product does not infringe the innovator’s patent or that the patent itself is invalid or unenforceable.

Filing a PIV certification is a high-risk, high-reward move. It almost always triggers a patent infringement lawsuit from the brand company, which in turn initiates an automatic 30-month stay on the FDA’s approval of the generic, giving the parties time to litigate. If the generic company wins the lawsuit or the patent expires during the litigation, it can launch its product. Crucially, the first generic company to successfully file a PIV certification is rewarded with 180 days of market exclusivity, a lucrative period during which it is the only generic competitor to the brand. This potential prize makes sophisticated patent intelligence and a well-planned PIV strategy essential for any serious generic player.

The Shadow of Trade Policy: “TRIPS-Plus” and Market Access

The final layer of complexity in the IP landscape comes from international trade policy. In the years since TRIPS was enacted, the United States and the European Union have consistently pushed for even stronger IP protections in their bilateral and regional Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). These provisions, often referred to as “TRIPS-Plus,” impose IP standards that go far beyond the minimums required by the WTO.

Health activists have long argued that these agreements are designed to benefit multinational pharmaceutical companies at the expense of public health in developing countries, raising drug prices and restricting access to affordable generics. One of the most damaging TRIPS-Plus provisions is data exclusivity (or test data protection). This rule prevents a country’s drug regulatory authority from relying on the innovator’s clinical trial data (which was submitted to prove the drug’s safety and efficacy) to approve a generic version for a set period, typically five years or more. This creates a new form of monopoly that can block generic entry even when there are no patents on the drug.

The U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement provides a stark case study of the real-world impact of these provisions. After the agreement was implemented, Jordan was required to enact data exclusivity. An analysis by Oxfam and other researchers found that this single provision had a devastating effect 42:

- It delayed generic competition for 79% of new medicines launched in Jordan between 2002 and mid-2006.

- It contributed to a 20% increase in medicine prices during that period.

- It did not lead to any significant increase in R&D or foreign direct investment by pharmaceutical companies in Jordan.

More recent research confirms this trend on a broader scale. A 2021 study analyzing 42 countries found that the implementation of data exclusivity, often required by U.S. FTAs, was associated with an average increase in imported drug prices of 2.4 to 4.5 percentage points each year. This evidence strongly suggests that TRIPS-Plus provisions in trade agreements serve as a powerful tool to delay generic competition and maintain high prices, placing an additional burden on the already strained health systems of emerging markets.

Section 5: On-the-Ground Realities: Case Studies from the Front Lines

Theoretical frameworks and global statistics are essential, but to truly understand the dynamics of the generic medicines landscape, we must examine the on-the-ground realities. The experiences of specific countries, diseases, and regulatory bodies provide invaluable lessons in what works, what doesn’t, and why. These case studies illustrate the profound impact of policy choices, the life-and-death consequences of access, and the critical need for localized, adaptable strategies.

India: The “Pharmacy of the World”

No country is more central to the story of generic medicines than India. Its journey from an import-dependent nation to a global pharmaceutical powerhouse is a masterclass in the power of strategic industrial and intellectual property policy.

The pivotal moment in India’s pharmaceutical history was the passage of the Indian Patents Act of 1970. This landmark legislation, enacted under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, abolished “product patents” for medicines and food, replacing them with a “process patent” regime.32 This seemingly technical change had revolutionary consequences. It meant that Indian companies were legally free to reverse-engineer and manufacture any patented drug, as long as they developed their own novel and unpatented manufacturing process.

This policy unleashed a wave of domestic innovation in process chemistry and created a fiercely competitive local market. Indian scientists became masters at developing low-cost, efficient methods for producing complex active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Companies like Cipla, Ranbaxy (later acquired by Sun Pharma), and Dr. Reddy’s Labs, which had been minor players, grew into industrial giants. By the time India rejoined the global product patent system under the TRIPS agreement in 2005, it had built a formidable and self-reliant pharmaceutical industry.

Today, India’s position is undisputed. It is the world’s largest supplier of generic drugs by volume, earning it the moniker “pharmacy of the world.”

- It supplies nearly 47% of the pharmaceutical needs of the United States, its largest export market.

- It manufactures an estimated 85% of the generic antiretroviral (ARV) drugs procured for HIV treatment programs in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Its leading companies, such as Sun Pharma (the world’s fourth-largest specialty generics company), Cipla, and Lupin, are major global players.

However, this success story is not without its challenges and controversies. The intense price competition that defines the Indian market has raised persistent concerns about quality assurance. In recent years, Indian manufacturing facilities have faced heightened scrutiny and an increase in audits from the U.S. FDA. This came to a head with a 2025 study published in Production and Operations Management, which found that generic drugs made in India were associated with 54% more severe adverse events (including hospitalization and death) compared to their U.S.-made equivalents. The findings were largely driven by “mature generics”—older, off-patent drugs where intense cost pressure may lead to compromises in operations and supply chain integrity. This study powerfully reinforces the “Crisis of Trust” theme, demonstrating that the perception of quality issues is, at times, rooted in verifiable data, and presents a major strategic challenge for the Indian industry’s global reputation.

The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Africa: A Landmark Success for Generics

There is no more powerful testament to the life-saving impact of affordable generic medicines than the global response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic in Africa. This case is not just a historical example; it is the foundational proof-of-concept for large-scale access programs.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the situation was catastrophic. While effective combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) had turned HIV into a manageable chronic condition in wealthy countries, it remained a death sentence in Africa. The primary reason was cost. The annual price of a first-line treatment regimen was over $10,000 per patient, a price utterly beyond the reach of individuals and governments in the developing world.

The turning point came with the entry of Indian generic manufacturers. Empowered by India’s process patent laws, companies like Cipla began producing generic versions of the essential ARV drugs at a fraction of the cost. This created a competitive market that drove prices down dramatically. The impact, as documented in numerous studies and reports, was transformative:

- An analysis of procurement data from 2004-2006 showed that generic companies supplied 63% of the ARVs to Sub-Saharan Africa, at prices that were, on average, one-third of those charged by brand companies.47

- The average price of a first-line generic regimen fell from thousands of dollars to an average of $114 per patient per year during that period.

- By 2020, thanks to continued competition and scaled-up production, the annual cost of a first-line regimen had dropped to as low as $65.

This radical price reduction, fiercely championed by advocacy groups like Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), made the previously unthinkable possible. It enabled the creation and massive scale-up of global health initiatives like the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. These programs could now purchase medicine for millions of people instead of thousands. Today, an estimated 25 million people are alive and on treatment, a public health achievement that would have been impossible without the advent of affordable generic ARVs. The HIV/AIDS story proved a fundamental principle: when the price barrier is decisively broken, health systems and the global community can mobilize to overcome other infrastructural and logistical challenges to deliver care at scale.

The Hepatitis C Revolution: The Power of Voluntary Licensing

While the HIV story was largely one of confrontation and competition, the more recent effort to expand access to cures for Hepatitis C (HCV) showcases a different, more collaborative model: voluntary licensing (VL).

In 2013, a new class of drugs called Direct-Acting Antivirals (DAAs) was introduced, offering a cure for HCV with over 95% efficacy in just three months. The problem was their price. The initial cost in the U.S. was an astronomical $85,000 per course of treatment, sparking global outrage and fears that this cure would be inaccessible to the vast majority of the 71 million people living with HCV, most of whom were in LMICs.53

In response to this access crisis, the primary innovator, Gilead Sciences, took a proactive and unprecedented step. It established voluntary licensing agreements with 11 leading Indian generic pharmaceutical manufacturers. These agreements were not just a simple permission to sell; they were a comprehensive partnership :

- Broad Access: The licenses granted the generic companies the right to manufacture and sell generic versions of Gilead’s key HCV medicines (sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, etc.) in 105 developing countries.

- Full Technology Transfer: Gilead provided its licensees with a complete transfer of its manufacturing process and know-how, enabling them to scale up high-quality production quickly.

- Pricing Freedom: The generic licensees were free to set their own prices, fostering competition among them to drive costs down.

The impact was immediate and profound. Competition among the Indian licensees, coupled with direct price negotiations in some countries, caused prices to plummet. In Egypt, a country with one of the world’s highest burdens of HCV, the price of a three-month cure dropped from $900 in 2014 to less than $200 in 2016. Within the first two years of this model being implemented, over one million people in LMICs were treated with these revolutionary cures. The HCV case study demonstrates that proactive, collaborative models between innovator and generic companies, structured correctly, can be a powerful and rapid mechanism for expanding access to breakthrough medicines.

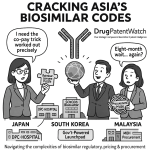

A Tale of Three Regulators: Navigating BRICS Markets

A critical strategic error is to view “emerging markets” as a monolith. The reality is a patchwork of unique regulatory environments, each with its own rules, timelines, and challenges. A successful multi-country strategy requires a deep, localized understanding of each NRA. A comparison of Brazil, South Africa, and China illustrates this diversity.

- Brazil (ANVISA): The Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) has overseen a well-defined generic medicines policy since the passage of Law 9.787 in 1999. The process is rigorous, requiring generic applicants to demonstrate both pharmaceutical equivalence and bioequivalence against a locally registered reference product. ANVISA is known for its thoroughness, which can translate into lengthy review timelines (120 days or more for standard review) and a requirement for its own GMP inspections of foreign manufacturing sites, adding a layer of complexity and cost for importers.

- South Africa (SAHPRA): The South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA), which replaced the Medicines Control Council (MCC), presides over a market dominated by generics, which account for roughly 90% of all new drug applications. The submission process is highly structured, requiring a specific dossier format (the MRF1) and proof of bioequivalence. A significant historical challenge for SAHPRA has been a massive backlog of applications, with some dossiers waiting years for review. While a backlog clearance program was initiated, this history of delays creates significant uncertainty for applicants regarding time-to-market.

- China (NMPA): China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) has undergone a radical transformation since 2015, moving to harmonize its regulatory standards with those of the U.S. and Europe. The centerpiece of its new generic policy is the “Quality and Efficacy Consistency Evaluation” (GQEC). This policy requires generic drugs—even those already on the market—to undergo new studies to prove they are fully equivalent in quality and efficacy to the originator drug or a designated reference product.59 The GQEC has dramatically raised the quality bar for generics in China, weeding out lower-quality producers. However, it has also significantly increased the cost, time, and complexity of gaining and maintaining market access, forcing a strategic recalculation for all players in the Chinese market.

The following table provides a high-level comparative snapshot of the regulatory requirements in these key markets, along with India, to aid in strategic planning.

Table 3: Regulatory Snapshot for Generic Approval in Key Emerging Markets

| Feature | India (CDSCO) | Brazil (ANVISA) | South Africa (SAHPRA) | China (NMPA) |

| Regulatory Body | Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation | Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária | South African Health Products Regulatory Authority | National Medical Products Administration |

| Key Legislation/Policy | Drugs & Cosmetics Act, 1940; New Drugs & Clinical Trials Rules, 2019 | Law 9.787/1999; RDC 753/2022 | Medicines and Related Substances Act, 1965 | Drug Administration Law (2019); Provisions for Drug Registration (2020) |

| Reference Product | Requires reference product, often one marketed in India. | Must use a specific reference medicine registered and marketed in Brazil. | Requires a reference product registered with SAHPRA. | Must use an originator or designated Reference Listed Drug (RLD). |

| Bioequivalence (BE) Study | BE studies are mandatory for most oral solid dosage forms. | BE studies are a core requirement for demonstrating interchangeability. | Comparative BE studies are required as proof of efficacy for most generics. | BE studies are a central part of the mandatory Quality and Efficacy Consistency Evaluation (GQEC). |

| Local Inspection | CDSCO may inspect foreign sites, especially for registration of new sites. | ANVISA conducts its own GMP inspections of foreign manufacturing sites. | SAHPRA may inspect overseas manufacturers if other SRA evidence is not sufficient. | NMPA conducts site inspections as part of the registration process. |

| Key Challenge | Complex, multi-layered bureaucracy; Evolving standards. | Lengthy review timelines; Strict local reference product requirements. | Historical application backlogs; Bureaucratic delays. | High cost and complexity of meeting GQEC requirements; Rapidly changing regulations. |

Sources: Data compiled from official regulatory websites and cited research.61

Section 6: The Next Frontier: Innovation and the Future of Accessible Medicines

The landscape of accessible medicine is not static. As the era of small-molecule blockbusters gives way to more complex therapies, the generic and pharmaceutical industries are on the cusp of a new wave of innovation. The rise of biosimilars presents a new frontier of off-patent opportunities, while revolutionary advancements in manufacturing technology hold the promise of fundamentally reshaping how medicines are produced and delivered. For strategists looking to the future, understanding these trends is essential for positioning their organizations for the next decade of growth.

Beyond Small Molecules: The Rise of Biosimilars

For the past several decades, the generic industry has been built on replicating small-molecule chemical drugs. The next great wave of opportunity—and challenge—lies in the world of biologics. These are large, complex molecules, such as monoclonal antibodies and therapeutic proteins, derived from living organisms. As the patents on many of the world’s best-selling biologics expire, the market for their follow-on versions, known as biosimilars, is poised for explosive growth. The global biosimilars market, valued at around $25 billion in 2023, is projected to surge to nearly $67 billion by 2028.

However, developing a biosimilar is a far more complex and costly endeavor than developing a traditional generic.

- Manufacturing Complexity: Unlike small molecules that can be precisely replicated through chemical synthesis, biologics are produced in living cell lines. It is impossible to create an identical copy of the originator product. The manufacturing process is incredibly sensitive; even minor changes in temperature, pH, or cell culture conditions can alter the final molecule’s structure and function. This complexity is why they are called “biosimilars,” not “bioidenticals”.63

- Higher Development Costs: The complexity of manufacturing, coupled with the need for more extensive clinical testing to demonstrate similarity, means that developing a biosimilar can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, compared to just a few million for a small-molecule generic. This creates a high barrier to entry, favoring large, well-capitalized companies with deep expertise in bioprocessing.

- Complex Regulatory Pathway: The approval process for biosimilars is significantly more involved than the ANDA pathway for generics. It requires a comprehensive “totality of the evidence” approach, including analytical studies, animal studies, and often, comparative clinical trials in patients to demonstrate that there are no clinically meaningful differences from the reference product. Achieving “interchangeability” status, which allows a pharmacist to substitute the biosimilar for the brand without physician intervention, is an even higher regulatory bar requiring additional switching studies.

- Logistical Hurdles: Many biologics are sensitive to temperature and require a robust cold chain for transportation and storage. Monoclonal antibodies, for instance, may require ultra-cold storage at temperatures as low as -80°C. Maintaining this cold chain from the factory to the patient is a major logistical and financial challenge, especially in emerging markets with weak infrastructure.

Despite these challenges, biosimilars represent a critical opportunity to bring down the cost of some of the world’s most expensive and life-changing therapies for diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders, making them more accessible to patients globally.

Advanced Manufacturing: A Paradigm Shift in Production

Beyond the products themselves, innovation in the manufacturing process itself holds the potential to revolutionize the pharmaceutical industry. Two key technologies are leading this charge: continuous manufacturing and 3D printing.

Continuous Manufacturing (CM)

For over a century, pharmaceuticals have been produced using batch manufacturing—a slow, stepwise process where ingredients are mixed in large vats, processed, and then moved to the next step. This can involve 10-20 separate steps and take months to produce a final product, with quality testing performed on the finished batch.

Continuous Manufacturing (CM) represents a fundamental paradigm shift. In a CM process, raw materials are continuously fed into an integrated, automated production line, and the finished drug product is continuously removed at the other end.66 The benefits are transformative:

- Efficiency and Speed: CM can dramatically reduce production time from months to days or even hours.

- Quality Assurance: Quality is monitored in real-time throughout the process, rather than just at the end, leading to a higher and more consistent level of quality assurance.

- Flexibility and Reduced Footprint: CM facilities are much smaller than traditional batch plants, reducing capital costs and making it more feasible to build decentralized or localized manufacturing sites.

For emerging markets, CM is a potential game-changer. Africa, for example, currently imports over 90% of its APIs. The lower cost and smaller footprint of CM technology could make it economically viable for African nations to establish their own state-of-the-art, competitive local API manufacturing industries, reducing import dependency and enhancing health security.

3D Printing (Additive Manufacturing)

An even more futuristic technology, 3D printing, is moving from the realm of science fiction to pharmaceutical reality. Also known as additive manufacturing, this technology builds a solid object layer by layer from a digital model. The FDA approved the first 3D-printed drug in 2015, and research is rapidly accelerating.

The primary advantage of 3D printing in pharmaceuticals is its potential to enable true personalized medicine.70

- Tailored Dosing: 3D printers can produce tablets with highly precise and customized dosages, tailored to an individual patient’s weight, metabolism, or condition. This is particularly valuable for special populations like children and the elderly, for whom standard adult doses are often inappropriate.

- Complex Formulations: The technology allows for the creation of “polypills” that combine multiple drugs into a single tablet, each with its own specific release profile (e.g., one drug released immediately, another over 12 hours). This can simplify complex drug regimens and improve patient adherence.

- On-Demand Production: In the future, 3D printers could be located in hospital pharmacies or even local clinics, allowing for the on-demand printing of customized medications. This could revolutionize the supply chain, mitigate drug shortages, and make it possible to provide tailored therapies in remote or underserved areas.

While significant technical and regulatory hurdles remain, particularly in emerging markets, these advanced manufacturing technologies represent the next frontier. They hold the promise of making drug production faster, cheaper, higher quality, and more personalized, with profound implications for expanding access to medicine across the globe.

Section 7: Voices from the Ecosystem: Advocacy, Policy, and Corporate Strategy

The journey of a medicine from the factory to the patient is shaped by a complex ecosystem of actors, each with a distinct perspective, motivation, and voice. Understanding the arguments of advocacy groups, the experiences of patients, and the strategic calculus of corporate leaders is essential to painting a complete picture of the challenges and opportunities in expanding global access to medicines.

The Moral Imperative: Perspectives from Advocacy Groups

On the front lines of the access to medicines debate are non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that serve as both service providers and powerful advocates. Their work is grounded in a moral imperative to ensure that public health needs are not sacrificed for commercial interests.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been one of the most influential voices in this arena for decades. Their perspective is forged in the crucible of humanitarian crises, where their doctors and nurses are often unable to treat patients because essential medicines are too expensive, no longer produced, or simply ineffective for the diseases they face.

MSF’s core message is simple and powerful: “Medicines Are Not a Luxury”. They consider it “fundamentally unacceptable” that one-third of the world’s population lacks access to the medicines they need. Through their Access Campaign, launched in 1999, MSF works to :

- Push for price cuts by stimulating the production of affordable generics.

- Act as a watchdog to ensure corporate interests don’t win out over public health.

- Steer R&D toward neglected diseases that disproportionately affect the poor.

- Support new models of innovation that do not rely on high prices to recoup costs.

Their advocacy is often distilled into pointed, challenging questions that cut to the heart of the issue. As the MSF Access Campaign asks, “What good is a breakthrough medicine if the people who need it cannot afford it?”. This question encapsulates their belief that the value of a medicine is not just in its invention, but in its delivery to the patient.

Oxfam

Oxfam brings a different but equally critical lens to the debate, focusing on the economic structures that perpetuate inequality and hinder access. Their research has shone a harsh light on the financial practices of the pharmaceutical industry. A major 2018 report, “Prescription for Poverty,” accused four of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies—Abbott, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer—of systematically using a complex web of subsidiaries in overseas tax havens to avoid paying their fair share of taxes in both developed and developing countries.75

Oxfam’s key arguments include :

- Tax avoidance deprives governments of critical revenue that could be used to fund healthcare. They estimated that the four companies studied may have deprived developing countries of over $100 million annually in tax revenue.

- High drug prices are driven by government-granted monopolies (patents), not R&D costs. Oxfam’s research found that major drug companies often spend more on marketing and shareholder payouts than on R&D.

- Public funding is the engine of innovation. The report highlights that all 210 drugs approved by the FDA between 2010 and 2016 benefited from publicly funded research, challenging the industry’s narrative that high profits are the sole driver of new cures.

Oxfam’s work reframes the access debate, arguing that the business model of the pharmaceutical industry—built on maximizing profits through monopoly pricing and minimizing taxes through accounting maneuvers—is itself a fundamental barrier to global health equity.

The Patient Voice: The Human Cost of High Prices

Beyond the policy debates and corporate boardrooms, the issue of access to medicines is a daily reality for millions of individuals. Patient advocacy groups like Patients For Affordable Drugs work to bring these personal stories to the forefront of policy discussions, grounding the debate in the human cost of high prices.

Their central argument is a simple, undeniable truth: “drugs don’t work if people can’t afford them”. The stories they share illustrate the impossible choices that patients are forced to make:

- Steven Hadfield, a patient from North Carolina managing both diabetes and blood cancer, described how the high cost of his medicine, Januvia, forced him to make “tough choices to afford it”.

- Jacquie Persson from Iowa, who relies on the drug Stelara (with a list price of $25,000 a month) to manage her Crohn’s disease, lives with the constant fear that a change in her insurance coverage would make her life-sustaining medicine completely unaffordable, a reality she calls a “shadow over my life”.

These stories are not just anecdotes; they are the lived experience of a system where financial considerations can override medical needs. The advocacy of these groups focuses on tangible policy solutions aimed at increasing competition and lowering prices, such as ending patent system abuses that delay generic entry and ensuring the successful implementation of laws that allow for government price negotiation.

The C-Suite Perspective: A World of Differentiated Strategy

For the pharmaceutical executive, the emerging market landscape is not a single problem to be solved but a complex mosaic of distinct opportunities and challenges. The C-suite perspective, articulated by industry leaders and consultants, has evolved from a simplistic view of “emerging markets” to a highly nuanced and differentiated strategic approach.

The consensus among seasoned strategists is clear: there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach. A strategy that works in Brazil will likely fail in China; what succeeds in the private market of urban Mexico is irrelevant to the public health system of rural Indonesia. Success requires a deep, localized understanding of each market’s unique health system, regulatory environment, and patient needs.

Several key themes emerge from the executive perspective:

- Long-Term Commitment: Companies that succeed are those that invest for the long haul, prioritizing sustainable growth and market presence over short-term, one-off profits. They must be willing to weather economic downturns and political instability.

- Local Talent and Empowerment: Building a strong local team and empowering them with the authority to make decisions is critical. HQ’s role is not to dictate strategy from afar but to transfer skills and support the local leadership who understand the market best.

- Portfolio Alignment: A company must critically assess its product portfolio and align it with the specific public health priorities and economic realities of each market. A portfolio of high-priced, niche specialty drugs may require a completely different market access strategy than one focused on high-volume primary care medicines.

- Ecosystem Shaping: The most advanced thinking moves beyond simply selling a product to actively shaping the entire access ecosystem. This involves engaging with governments on policy, partnering with providers on education, and working with logistics firms to solve last-mile delivery challenges. It is about becoming an integrated healthcare partner, not just a supplier.

Ultimately, the future of the pharmaceutical industry in emerging markets is not about selling cheap drugs. It is about mastering a new and far more complex set of capabilities. The winning companies will be those that can master not only the science of bioequivalence and the law of patents but also the art of building trust, the logistics of complex supply chains, and the politics of public-private partnerships. The challenge is immense, but for those who can solve this multifaceted puzzle, the reward is not just market share, but a central role in shaping the future of global health.

Key Takeaways

- Emerging Markets are the New Growth Engine: The pharmaceutical industry’s future growth is overwhelmingly concentrated in emerging markets. Understanding and successfully navigating these diverse environments is no longer optional; it is a core strategic imperative for survival and success.

- Generics are More Than Just Price: While affordability is their primary benefit, high-quality generic medicines are the result of a rigorous scientific and regulatory process (ANDA) that ensures they are bioequivalent to innovator drugs. Their introduction generates massive economic savings and a direct public health dividend by expanding access and improving adherence.

- Access is a Multifaceted Challenge: The price of a medicine is only one barrier to access. A successful market entry strategy must address a complex web of obstacles, including inefficient regulatory systems, weak infrastructure, supply chain vulnerabilities, and a profound “crisis of trust” fueled by the prevalence of substandard and falsified medicines.

- Intellectual Property is a Strategic Battlefield: The global IP landscape is a dynamic chess match. Innovator companies use strategies like “patent evergreening” to extend monopolies, while generic companies use sophisticated patent intelligence (from services like DrugPatentWatch) and legal challenges (like Paragraph IV filings) to open markets. “TRIPS-Plus” provisions in trade agreements add another layer of complexity that often favors innovators.

- There is No “One-Size-Fits-All” Strategy: Emerging markets are not a monolith. Each country has a unique healthcare system, regulatory framework, and economic reality. Success requires a localized, long-term strategy that moves beyond simple product sales to focus on building trust, shaping the access ecosystem, and aligning with local health priorities.

- Landmark Cases Prove the Model: The transformative impact of generic antiretrovirals in the fight against HIV/AIDS in Africa proves that breaking the price barrier can enable massive public health achievements. Similarly, the use of voluntary licensing for Hepatitis C cures demonstrates a viable collaborative model for expanding access to breakthrough innovations.

- Innovation is Reshaping the Future: The next frontier of accessible medicine lies in biosimilars and advanced manufacturing technologies. While presenting significant technical and financial challenges, biosimilars offer the potential to lower the cost of complex biologic therapies. Technologies like continuous manufacturing and 3D printing could revolutionize production, making it faster, cheaper, and more localized, with profound implications for supply chain resilience in emerging markets.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. If generic drugs are truly equivalent, why is there so much mistrust of them in emerging markets?

This is a critical and complex issue. The mistrust stems from two primary sources: perception and reality. The reality is the documented prevalence of substandard and falsified (SF) medicines in many low- and middle-income countries. These dangerous products, which may contain no active ingredient or even harmful substances, have eroded public confidence in any low-cost medicine. The perception is that “you get what you pay for.” Because generics look different (due to trademark laws) and cost significantly less, patients and even some healthcare professionals may incorrectly assume they are of lower quality. Overcoming this requires legitimate generic manufacturers to invest heavily in “trust-building” activities: marketing their approvals from stringent regulators like the FDA, ensuring supply chain integrity to prevent counterfeiting, and educating local medical communities on the science of bioequivalence.

2. What is “patent evergreening,” and how does it specifically impact emerging markets?

“Patent evergreening” is a strategy used by innovator pharmaceutical companies to extend their market monopoly beyond the initial 20-year patent term. They do this by filing numerous secondary patents on minor modifications of an existing drug, such as a new dosage form, a new method of use, or a new combination with another drug. This “patent thicket” makes it legally difficult and risky for generic companies to enter the market. For emerging markets, the impact is particularly severe. It directly delays the availability of affordable generic alternatives, forcing patients and under-resourced public health systems to pay high monopoly prices for longer. This can mean the difference between a government being able to treat thousands of patients versus tens of thousands, directly limiting access to essential medicines for diseases like cancer, HIV, and diabetes.

3. What is the single biggest non-price barrier that a generic company faces when trying to enter an emerging market?

While many barriers exist, one of the most significant and often overlooked is the regulatory barrier of the “missing reference product.” To gain approval, a generic must be compared to the original, innovator drug. However, in many smaller or poorer emerging markets, the innovator company may have never registered or launched its product in the first place. This creates a regulatory paradox: the generic cannot be approved because there is no local reference drug to prove equivalence against. This forces the generic company and the local regulatory authority into a more complex, costly, and time-consuming process, such as relying on data from other countries or using the WHO’s collaborative registration pathways, which can significantly delay or even block market entry.

4. How can advanced manufacturing technologies like 3D printing and continuous manufacturing specifically benefit healthcare in emerging markets?

These technologies are not just about making production more efficient; they offer solutions to some of the most persistent challenges in emerging markets. Continuous Manufacturing (CM) facilities have a much smaller physical footprint and lower capital cost than traditional batch plants. This makes it more economically feasible to build local API and drug product manufacturing facilities in regions like Africa, reducing their heavy dependence on imports from India and China and enhancing their health security. 3D Printing offers the potential for decentralized, on-demand production. A 3D printer in a remote clinic could produce a precise, personalized dose of a drug for a child, overcoming both “last-mile” supply chain problems and the issue of inappropriate dosing that is common when only adult-strength tablets are available.

5. Beyond providing cheaper drugs, what is the most important strategic shift a pharmaceutical company needs to make to be successful in emerging markets in the long term?