Part I: The Foundation of Pharmaceutical Patent Protection

Section 1: The Symbiotic Relationship Between Patents and Pharmaceutical Innovation

The modern pharmaceutical industry is built upon a foundation of intellectual property (IP) rights, with the patent system serving as the principal mechanism for incentivizing the monumental investment required to bring a new therapeutic to market. This relationship, however, is not merely a legal formality; it is a complex economic and social contract that balances the need for innovation with the imperative of public access. Understanding the nuances of this “patent bargain” is the first step in mastering the art and science of drafting effective pharmaceutical patent claims.

1.1 The Economic Imperative: Justifying Monopoly in the Face of High R&D Costs and Risk

Pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) is an endeavor characterized by extraordinary financial risk, protracted timelines, and a high probability of failure. The journey from initial discovery to an approved drug that can be prescribed to patients is a decade-long odyssey, with estimates for the average capitalized cost of development reaching as high as $2.23 billion in 2024.1 Some analyses show a wide range, from $161 million to over $4.5 billion per drug, reflecting the immense variability in development complexity.3 This process is not only expensive but also inefficient; for every 10,000 substances synthesized, only one or two may ultimately meet the high hurdles of safety and efficacy to gain regulatory approval.4

This economic reality creates a classic market failure. While the cost to the innovator is immense, the cost for a competitor to reverse-engineer and replicate a small-molecule drug is comparatively trivial.5 Without a mechanism to protect the initial investment, there would be little to no financial incentive for companies to undertake the perilous journey of drug discovery.3 The patent system addresses this failure by granting the inventor a limited-term monopoly—typically 20 years from the filing date—in exchange for a full public disclosure of the invention.10 This period of market exclusivity allows the innovator company to set prices that can recoup R&D expenditures and, critically, fund the next generation of research into new medicines.3

However, this model is not without its critics. Some legal scholars argue that the current patent system is misaligned with the actual sources of cost and risk in drug development. The majority of R&D costs—often cited as 70% or more—are incurred during human clinical trials (the “data information good”), not during the initial discovery of the compound (the “compound information good”).5 Yet, patent law primarily protects the compound itself, providing only indirect and often inefficient incentives for the costly clinical work required for regulatory approval. This has led to proposals that a revised system of regulatory exclusivity, which directly protects clinical trial data, might be a more efficient and better-tailored mechanism to foster innovation while reducing the societal costs associated with the current patent regime.5

1.2 The Dual Pillars of Exclusivity: Distinguishing Patent Rights from FDA Regulatory Exclusivity

A frequent point of confusion in the pharmaceutical IP landscape is the distinction between patents and regulatory exclusivity. While both provide periods of market protection, they are separate legal instruments granted by different government bodies for different reasons.6

Patents are granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) at any point during a drug’s development lifecycle. They are based on an assessment that the invention is new, useful, and non-obvious. A patent’s scope is defined by its claims and can cover a wide range of inventions, including the active ingredient, a specific formulation, a method of manufacturing, or a new method of use.6

Regulatory Exclusivity, in contrast, is granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) upon approval of a new drug. It is a statutory protection that prevents the FDA from approving a competing generic or biosimilar application for a set period, irrespective of patent status.6 The duration and type of exclusivity depend on the nature of the drug and the patient population it serves. Key types include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years for a drug containing an active moiety not previously approved by the FDA.14

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): 7 years for a drug designated to treat a rare disease or condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S..6

- Biologics Exclusivity: 12 years of data exclusivity for a new biologic product, preventing the FDA from approving a biosimilar application during that time.16

- Other Exclusivities: Shorter periods, such as 3 years for new clinical investigations that are essential to approval, and a 6-month pediatric exclusivity that can be added to existing patents and exclusivities.14

These two forms of protection can run concurrently, overlap, or exist independently.6 A drug’s effective market life—the actual period of monopoly before generic competition—is determined by the complex interplay of all applicable patents and exclusivities.16 While regulatory exclusivity provides a baseline of protection for new products, strategic concerns about extending market protection, often termed “evergreening,” typically focus on patenting strategies. This is because patent terms are longer and can be layered through the filing of secondary patents on improvements, whereas regulatory exclusivity is generally a one-time grant for the initial approval of a new product.6

1.3 The Global Patent Bargain: Disclosure in Exchange for Limited Monopoly

At its core, the patent system operates on a foundational principle: a quid pro quo between the inventor and the public.10 The

quo is the grant of a limited monopoly—the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the patented invention for a term of 20 years from the filing date. The quid is the inventor’s obligation to provide a full and clear disclosure of the invention in the patent application.10

This disclosure serves two vital public purposes. First, it teaches the public how the invention works, adding to the collective store of technical knowledge and allowing others to build upon it, thereby fostering further innovation.6 Second, upon the expiration of the patent term, the disclosure must be sufficient to enable a person skilled in the relevant technical field to practice the invention, ensuring that it enters the public domain and can be freely used by all.10 This “patent bargain” is central to the legitimacy of the patent system. The stringency of the disclosure requirements—specifically, the doctrines of written description, enablement, and definiteness—has become a primary battleground in modern pharmaceutical patent litigation, as courts increasingly scrutinize whether the breadth of the monopoly sought is truly justified by the quality and completeness of the technical information provided to the public.

Section 2: The Core Tenets of Patentability: A Global Perspective

Before a single claim can be drafted, the underlying invention must be assessed against a rigorous set of legal standards known as the requirements for patentability. These criteria serve as the gatekeepers of the patent system, ensuring that only genuine, substantive innovations are granted the powerful right of market exclusivity. While the fundamental principles are shared globally, their specific application varies between major jurisdictions, most notably the United States and Europe, creating a complex landscape for international patent strategy.

2.1 The U.S. Framework: Navigating Title 35 of the U.S. Code

In the United States, an invention must satisfy five primary requirements, codified in Title 35 of the U.S. Code, to be deemed patentable.10

Patentable Subject Matter (§ 101): The first threshold is to determine if the invention falls into one of the four statutory categories: any new and useful “process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof”.10 While the Supreme Court in

Diamond v. Chakrabarty famously interpreted this to “include anything under the sun that is made by man,” it also established crucial judicial exceptions.10 Laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.22 This has had a profound impact on the life sciences. In

Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., the Court held that a method for determining a drug dose based on a natural correlation was an unpatentable law of nature.24 Similarly, in

Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., the Court found that isolated human genes were unpatentable products of nature, though synthetic complementary DNA (cDNA) was deemed eligible.24

Utility (§ 101): The invention must be useful. The USPTO applies a three-pronged test, requiring the asserted utility to be “specific, substantial, and credible”.10 This means the invention must have a defined, real-world purpose and not be a mere research curiosity.10 While this is a relatively low bar for most therapeutic inventions, it can pose a challenge for early-stage discoveries where the practical application is not yet fully established.26

Novelty (§ 102): The invention must be new. This is a strict requirement: an invention is not novel if every single element of the claimed invention is disclosed in a single prior art reference (e.g., a previously published patent, journal article, or public use).6 This is also known as “anticipation.”

Non-Obviousness (§ 103): This is often the most difficult and litigated requirement for patentability.28 An invention, even if novel, cannot be patented if the differences between it and the prior art are such that the invention as a whole would have been obvious at the time it was made to a “Person Having Ordinary Skill in The Art” (PHOSITA).6 This standard prevents the patenting of trivial advancements that are merely predictable combinations of known elements.27 The Supreme Court’s 2007 decision in

KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc. significantly reshaped this analysis, replacing the Federal Circuit’s rigid “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” (TSM) test with a more flexible and expansive inquiry that considers factors like market pressures and common sense.10

The Disclosure Requirements (§ 112): This section embodies the quid pro quo of the patent bargain and has become the central focus of recent landmark litigation. It comprises three distinct but interrelated requirements:

- Written Description: The patent’s specification must contain a description of the invention that reasonably conveys to a PHOSITA that the inventor was “in possession” of the full scope of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date.10

- Enablement: The specification must teach a PHOSITA how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without requiring “undue experimentation”.10

- Definiteness: The claims themselves must “particularly point out and distinctly claim” the invention, providing clear notice to the public of the boundaries of the patented territory.32

2.2 The European Standard: The European Patent Convention (EPC)

The European Patent Office (EPO) applies a framework that, while conceptually similar to that of the U.S., has important structural and procedural differences that demand a tailored strategic approach. The core requirements are laid out in the European Patent Convention (EPC).33

Novelty (Art. 54 EPC): The EPC employs an “absolute novelty” standard. Any disclosure made available to the public anywhere in the world, in any form, before the effective filing date of the patent application can destroy novelty.33 Unlike the U.S., which has a limited one-year grace period for an inventor’s own disclosures, Europe has no such provision, making early filing before any public disclosure absolutely critical.

Inventive Step (Art. 56 EPC): This is the European counterpart to non-obviousness. An invention is considered to involve an inventive step if, having regard to the state of the art, it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art.21 The EPO formally assesses this using the “problem-solution approach,” a structured, three-step analysis:

- Determine the “closest prior art.”

- Identify the objective technical problem to be solved over that prior art.

- Consider whether or not the claimed invention, starting from the closest prior art and the objective technical problem, would have been obvious to the skilled person.33

Industrial Applicability (Art. 57 EPC): This requirement is analogous to the U.S. utility standard, mandating that the invention can be made or used in any kind of industry, including agriculture.21 It ensures that the invention has a practical, technical purpose and is not purely abstract.33

Exclusions from Patentability: The EPC explicitly excludes certain categories of subject matter from patentability. Most relevant to the pharmaceutical sector is the exclusion of “methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy and diagnostic methods practised on the human or animal body” (Art. 53(c) EPC).35 However, this prohibition does not apply to products, such as substances or compositions, for use in any of these methods. This carve-out allows for the patenting of new drugs and, critically, for “second medical use” claims that protect new therapeutic applications of known substances. The EPC also excludes inventions whose commercial exploitation would be contrary to

“ordre public” or morality, such as processes for cloning human beings.35

The procedural differences between the U.S. assessment of non-obviousness and the EPO’s assessment of inventive step create distinct strategic pathways. The flexible, holistic inquiry established by KSR in the U.S. can lead to arguments based on a wide range of factors, including secondary considerations like commercial success or the failure of others. In contrast, the EPO’s structured “problem-solution approach” necessitates a more formulaic line of reasoning. Success at the EPO often depends on skillfully defining the objective technical problem in a way that the prior art does not suggest the claimed solution. An invention that might be vulnerable to an “obvious to try” rejection in the U.S. could be successfully defended at the EPO by framing it as a non-obvious solution to a narrowly defined technical problem. This divergence mandates that a global patent application cannot simply be a translation; the core arguments and potentially even the claim structure must be adapted to the unique legal tests of each jurisdiction.

Part II: The Anatomy of a Drug Patent Claim

Patent claims are the heart of the patent document; they are the legally operative sentences that define the precise boundaries of the inventor’s exclusive rights.37 Much like the legal description in a property deed defines the borders of a parcel of land, the claims of a patent delineate the exact scope of the technology that others are barred from making, using, or selling without permission.37 Every word in a claim is scrutinized during patent examination and, if the patent is ever litigated, by the courts. Therefore, mastering the technical grammar of claim drafting is an essential prerequisite to developing any effective IP strategy.

Section 3: Deconstructing the Claim: Language as a Legal Boundary

A patent claim is a single sentence, often long and complex, that is meticulously structured into three distinct parts: the preamble, the transitional phrase, and the body.37

3.1 The Preamble: Defining the Invention’s Class

The preamble is the introductory statement that sets the stage for the invention by identifying its general category or class.37 It typically begins with “A…” or “An…” and should be consistent with the invention’s title. Examples in the pharmaceutical context include:

- “A compound of formula I…”

- “A pharmaceutical composition…”

- “A method for treating cancer…”

While often viewed as simply a descriptive introduction, the preamble can, under certain circumstances, be interpreted as a substantive limitation on the scope of the claim. This typically occurs when the preamble provides essential context for the invention or is necessary to give life, meaning, and vitality to the claim. Drafters must be cautious to ensure the preamble is broad enough to capture the full essence of the invention without inadvertently narrowing its scope.

3.2 The Transitional Phrase: The Art of Open and Closed Language

Connecting the preamble to the body of the claim is the transitional phrase, a short but powerful term that dictates the breadth of the claim.37 The choice of this phrase is one of the most critical decisions in claim drafting.

- “Comprising” (Open-ended): This is the most frequently used and preferred transitional phrase in U.S. patent practice. It is interpreted to mean “including” or “containing” and signifies that the claim is “open” to the inclusion of additional, unrecited elements or steps.37 For example, a claim for a pharmaceutical composition “comprising an active ingredient A and an excipient B” would be infringed by a product that contains A, B, and an additional excipient C. This open-ended language provides the broadest possible scope of protection, making it more difficult for competitors to design around the patent by simply adding an extra component.

- “Consisting of” (Closed-ended): This is the most restrictive transitional phrase. It creates a “closed” claim, meaning that the invention includes only the elements or steps that are explicitly recited, and nothing more (apart from naturally occurring impurities).37 A claim for a composition “consisting of an active ingredient A and an excipient B” would

not be infringed by a product containing A, B, and C. This phrase is used strategically, particularly in chemical and pharmaceutical inventions, when the exclusion of other components is essential to the novelty or function of the invention. For instance, it might be used to claim a highly purified substance or a specific formulation where the presence of any other ingredient would undermine its efficacy or stability.

3.3 The Body: Positively Reciting the Elements of the Invention

The body of the claim follows the transitional phrase and enumerates the essential elements, steps, and limitations that define the invention.37 In the U.S., patent law requires that the elements of the invention be “positively recited.” This means the claim should describe what the invention

is, rather than what it is not (a practice known as negative limitation, which is disfavored and only allowed in specific circumstances).

The fundamental principle in drafting the body of an independent claim is to include the absolute minimum number of elements required to distinguish the invention from the prior art.39 Every additional element or limitation added to a claim narrows its scope, creating another potential avenue for a competitor to design around it. For example, if a novel compound is patentable on its own, a claim to “A compound of formula I” is far broader and more valuable than a claim to “A pharmaceutical composition comprising a compound of formula I and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier,” because the latter requires the presence of a carrier for infringement to occur. The art of claim drafting lies in this delicate balance: reciting enough detail to secure allowance over the prior art while maintaining the broadest possible scope of protection.

Section 4: A Lexicon of Pharmaceutical Claims: Types and Applications

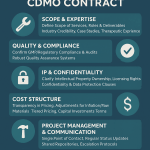

A robust pharmaceutical patent portfolio is not a single document but a carefully constructed fortress built from various types of claims, each designed to protect a different aspect of the invention. This multi-layered approach is essential for comprehensive lifecycle management and for creating a formidable barrier to generic and biosimilar competition.

4.1 Composition of Matter Claims: The Gold Standard

Composition of matter claims are widely regarded as the most valuable and powerful form of protection in the pharmaceutical industry.41 They protect the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the core chemical or biological entity responsible for the therapeutic effect. Their strength lies in their breadth: they cover the molecule regardless of how it is made, formulated, or used.43

- Species Claims: These are the most specific type of composition claim, directed to a single, precisely defined chemical compound.42 For example: “A compound which is 4-(5-pyridin-4-yl-1H-triazol-3-yl)pyridine-2-carbonitrile.” While narrow, a species claim covering a marketed drug is an extremely valuable asset.

- Genus Claims and Markush Structures: To protect not just a single compound but an entire family of related, inventive molecules, drafters use genus claims.42 These claims define a common chemical scaffold and use variables (e.g.,

R1, R2) to represent various possible chemical groups at different positions on the scaffold. A specialized form of this is the Markush claim, which recites a group of functionally equivalent members in the alternative, for example, “…wherein R1 is selected from the group consisting of halogen, alkyl, and aryl”.37 Genus and Markush claims are powerful tools for capturing a wide swath of chemical space, but their breadth makes them highly susceptible to invalidity challenges based on the stringent disclosure requirements of enablement and written description, a vulnerability starkly highlighted in recent landmark court decisions.46

4.2 Method of Use & Method of Treatment Claims

These claims protect a new application for a compound, which can be either a new or a previously known substance. They are the cornerstone of drug repurposing strategies and a key tool in patent lifecycle management, allowing companies to find new value in existing assets.44

- U.S. Practice: In the United States, methods of treating a medical condition are patentable subject matter.36 The standard format is direct and functional:

“A method of treating, comprising administering to a subject in need thereof a therapeutically effective amount of [compound X].” - European Practice (Second Medical Use): The EPC explicitly prohibits the patenting of methods for treatment of the human body.35 To overcome this, European practice has evolved specific claim formats to protect new therapeutic uses.

- Swiss-Type Claim (Historical Format): The older format, no longer accepted for new applications but still found in existing patents, is the “Swiss-type” claim: “Use of compound X in the manufacture of a medicament for treating disease Y.”.24 This format frames the invention as a manufacturing process with a specific therapeutic purpose.

- EPC 2000 Claim (Current Format): The modern format, established under the revised EPC 2000, is a purpose-limited product claim: “Compound X for use in treating disease Y.”.52 While appearing similar to a composition claim, its scope is strictly limited to the specified therapeutic use.

4.3 Formulation & Dosage Regimen Claims

These claims are critical secondary patents that protect specific features of the final, marketed drug product, often extending market exclusivity beyond the life of the initial composition of matter patent.

- Formulation Claims: These protect the specific combination of the API with various inactive ingredients (excipients) or a particular drug delivery system.24 Examples include claims directed to an extended-release tablet, a transdermal patch, a stabilized liquid formulation, or a nanoparticle delivery system.24 These inventions can be highly valuable, as they can improve a drug’s safety, efficacy, stability, or patient compliance.43

- Dosage Regimen Claims: These claims protect a specific method of administration, such as a particular dose, frequency, or timing (e.g., “a 40 mg dose administered subcutaneously once every two weeks”).53 Such regimens are often discovered and optimized during lengthy and expensive clinical trials.53 However, they face significant patentability hurdles, as patent examiners frequently argue that dose-ranging studies are a routine and obvious part of drug development.53 To overcome this, the patent applicant must typically demonstrate that the claimed regimen provides an unexpected technical effect, such as a surprising improvement in efficacy or a significant reduction in side effects compared to other known or predictable regimens.56

4.4 Process & Product-by-Process Claims

These claims focus on the manufacturing aspect of a pharmaceutical product.

- Process Claims: Also known as method-of-manufacture claims, these protect a novel and non-obvious process for synthesizing a compound.24 They are particularly valuable when the manufacturing process is more efficient, results in a higher purity product, or is the only known method to produce the desired compound or a specific polymorph.57

- Product-by-Process Claims: These claims define a product by the method used to create it, for example, “A compound of formula I, when produced by the process of claim 10.”.24 This format is typically used only when the product cannot be adequately described by its chemical structure or physical properties alone.57 A critical legal principle governs these claims: for purposes of patentability (novelty and non-obviousness), the claim is judged based on the

product itself, not the process. If the final product is identical to a product in the prior art, the claim is unpatentable even if it was made by a novel and inventive process.24

The following table provides a consolidated overview of these primary claim types, their strategic purpose, and key drafting considerations.

Table 1: Taxonomy of Pharmaceutical Patent Claims

| Claim Type | Primary Purpose | Key Drafting Considerations | Example Claim Snippet |

| Composition of Matter (Species) | Protect a specific active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). | The “gold standard” of protection; provides the broadest coverage for a single marketed drug. | “A compound which is [specific chemical name].” |

| Composition of Matter (Genus/Markush) | Protect a class of structurally related compounds. | Powerful for broad market control but highly vulnerable to enablement and written description challenges post-Amgen. | “A compound of formula I:… wherein R1 is selected from the group consisting of H, Cl, and CH3.” |

| Method of Treatment (U.S.) | Protect a new therapeutic use for a new or known compound (drug repurposing). | Must recite active, concrete treatment steps. Diagnostic-only steps are generally not patentable. | “A method of treating Alzheimer’s disease, comprising administering to a subject in need thereof a therapeutically effective amount of compound X.” |

| Second Medical Use (EPO) | Protect a new therapeutic use in jurisdictions that bar method of treatment claims. | Must use the “Compound X for use in…” format (EPC 2000). Avoids direct method of treatment prohibition. | “Compound X for use in a method of treating Alzheimer’s disease.” |

| Formulation | Protect the specific combination of API and excipients or a novel delivery system. | Essential for lifecycle management. Must often demonstrate an unexpected advantage over prior art formulations (e.g., improved stability, bioavailability). | “A pharmaceutical composition comprising compound X and a sustained-release polymer.” |

| Dosage Regimen | Protect a specific dosing schedule (e.g., dose, frequency, route of administration). | High obviousness/inventive step hurdle. Requires strong evidence of an unexpected technical effect (e.g., superior efficacy, reduced toxicity). | “Compound X for use in treating cancer, wherein the compound is administered at a dose of 100 mg once daily.” |

| Process (Method of Manufacture) | Protect a novel method of synthesizing the API or a key intermediate. | Provides an additional layer of protection. Can block competitors even if the composition patent has expired, if they must use the patented process. | “A process for preparing compound X, comprising the steps of…” |

| Product-by-Process | Define a product by its method of manufacture when it cannot be defined by structure. | Patentability is based on the novelty and non-obviousness of the product itself, not the process. | “The crystalline form of compound X produced by the process of claim 1.” |

Part III: Advanced Strategies in Pharmaceutical Claim Drafting

Beyond understanding the fundamental types of claims, effective patent strategy requires a sophisticated approach to their deployment. This involves navigating the inherent tension between claim breadth and legal validity, strategically extending a drug’s commercial life through follow-on patenting, and adapting to the unique scientific and legal challenges presented by the new frontier of biologic therapies.

Section 5: The Strategist’s Dilemma: Balancing Claim Breadth and Validity

The scope of a patent claim is its most critical attribute, defining the extent of the market monopoly. The central dilemma for any patent strategist is to draft claims that are broad enough to provide meaningful commercial protection but not so broad that they become invalid under the strict requirements of patent law.

5.1 The Pursuit of Broad Scope: Preventing Design-Arounds and Securing Market Dominance

The primary motivation for drafting broad claims is to prevent competitors from making minor, insubstantial modifications to an invention to avoid infringement—a practice known as “designing around”.46 A broad independent claim, which recites only the essential features of the invention, creates a wide protective perimeter.39 For example, a claim to a genus of chemical compounds protects not only the specific examples tested by the inventor but also potentially millions of other related compounds that fall within the claim’s structural definition.46

From a procedural standpoint, starting the patent examination process with broad claims is a sound strategy. Patent prosecution is often a negotiation between the applicant and the patent examiner.59 By initially proposing a broad scope, the applicant creates room to amend the claims to a narrower, but still commercially valuable, position in response to prior art rejections, ultimately arriving at an allowable scope of protection.32

5.2 The Necessity of Narrow Claims: Creating Fallback Positions and Expediting Prosecution

While broad claims are the ultimate prize, narrow claims serve critical strategic functions. A narrow claim, often called a “picture claim,” is tailored to a specific commercial product or a preferred embodiment of the invention.60 These claims offer several advantages:

- Ease of Allowance: Because they are highly specific, narrow claims are less likely to read on the prior art and are therefore easier and faster to get allowed by the patent office.59

- Resilience to Validity Challenges: The specificity of a narrow claim makes it more difficult to invalidate in litigation. To prove a claim is anticipated or obvious, a challenger must typically find every single element of the claim in the prior art. The more elements a claim has, the harder this becomes.60

- Value for Early-Stage Companies: For a startup or emerging biotech company, securing an issued patent—even a narrow one—that covers its lead product candidate can be crucial for attracting venture capital and establishing credibility with investors and potential partners.60

5.3 A Tiered Approach: Using Dependent Claims to Build a Resilient Protective Fortress

The most robust and effective patent applications employ a tiered or “picture-frame” strategy that combines the strengths of both broad and narrow claims.59 This involves drafting one or more broad independent claims that define the core invention, followed by a series of dependent claims that progressively narrow the scope by adding specific features, limitations, or preferred embodiments.38

Dependent claims serve as indispensable fallback positions.39 If, during litigation, a broad independent claim is found to be invalid (for example, for being obvious over the prior art or for lacking sufficient enablement), a narrower dependent claim that recites an additional, non-obvious feature may still be held valid. If that dependent claim covers the commercial product, the patent owner can still enforce their rights and protect their market position. This layered approach creates a resilient patent that is much more difficult for a challenger to completely invalidate, thereby building a formidable protective fortress around the invention.

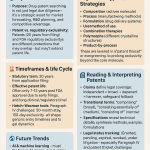

Section 6: Patent Lifecycle Management: The Science of “Evergreening”

The term of a patent is finite, and for blockbuster drugs, its expiration can lead to a catastrophic loss of revenue. This phenomenon, known as the “patent cliff,” is a central strategic challenge for the entire pharmaceutical industry. The strategic response is a set of practices known as patent lifecycle management or, more pejoratively, “evergreening.”

6.1 The “Patent Cliff” and the Commercial Rationale for Lifecycle Management

A blockbuster drug can generate billions of dollars in annual revenue during its period of market exclusivity. However, upon patent expiry and the entry of generic competitors, this revenue can plummet by as much as 80% or more within the first year.9 The scale of this threat is immense; projections indicate that drugs with over $300 billion in annual sales are at risk of losing exclusivity between 2023 and 2028.9 For example, Merck’s cancer immunotherapy Keytruda, which generated over $29 billion in sales in 2024, faces patent expiration in 2028, creating enormous financial exposure.9

In response, innovator companies engage in “lifecycle management,” a strategy of filing for secondary patents on new inventions related to the original drug to extend its commercial life.13 While critics label this “evergreening” and argue that it involves patenting trivial modifications to unfairly block competition, proponents contend that it protects genuine follow-on innovation that can provide real benefits to patients, such as improved dosing convenience or reduced side effects.61

6.2 The Toolkit of Secondary Patenting: Polymorphs, Metabolites, and More

The practice of lifecycle management relies on the full spectrum of claim types to protect innovations discovered after the original API. The most common strategies include:

- Polymorphs: Patenting new and distinct crystalline structures of the same API. Different polymorphs can have different physical properties, such as improved stability or solubility, which can be critical for drug formulation and bioavailability.8 A famous example is Pfizer’s atorvastatin (Lipitor), where a patent on a specific crystalline form extended market exclusivity by an additional six years.73

- Metabolites, Salts, and Isomers: Filing patents on the active metabolites produced by the body after the drug is ingested, or on different salt forms or stereoisomers (enantiomers) of the original compound that may offer a better therapeutic profile.8

- New Formulations and Delivery Systems: Developing and patenting improved formulations, such as extended-release versions that allow for once-daily dosing, or new delivery devices like auto-injectors or inhalers.13

- New Methods of Use and Indications: Securing method-of-use patents for new diseases or patient populations that the drug is found to be effective in treating, a classic drug repurposing strategy.13

6.3 Building the “Patent Thicket”: A Defensive and Offensive Strategy

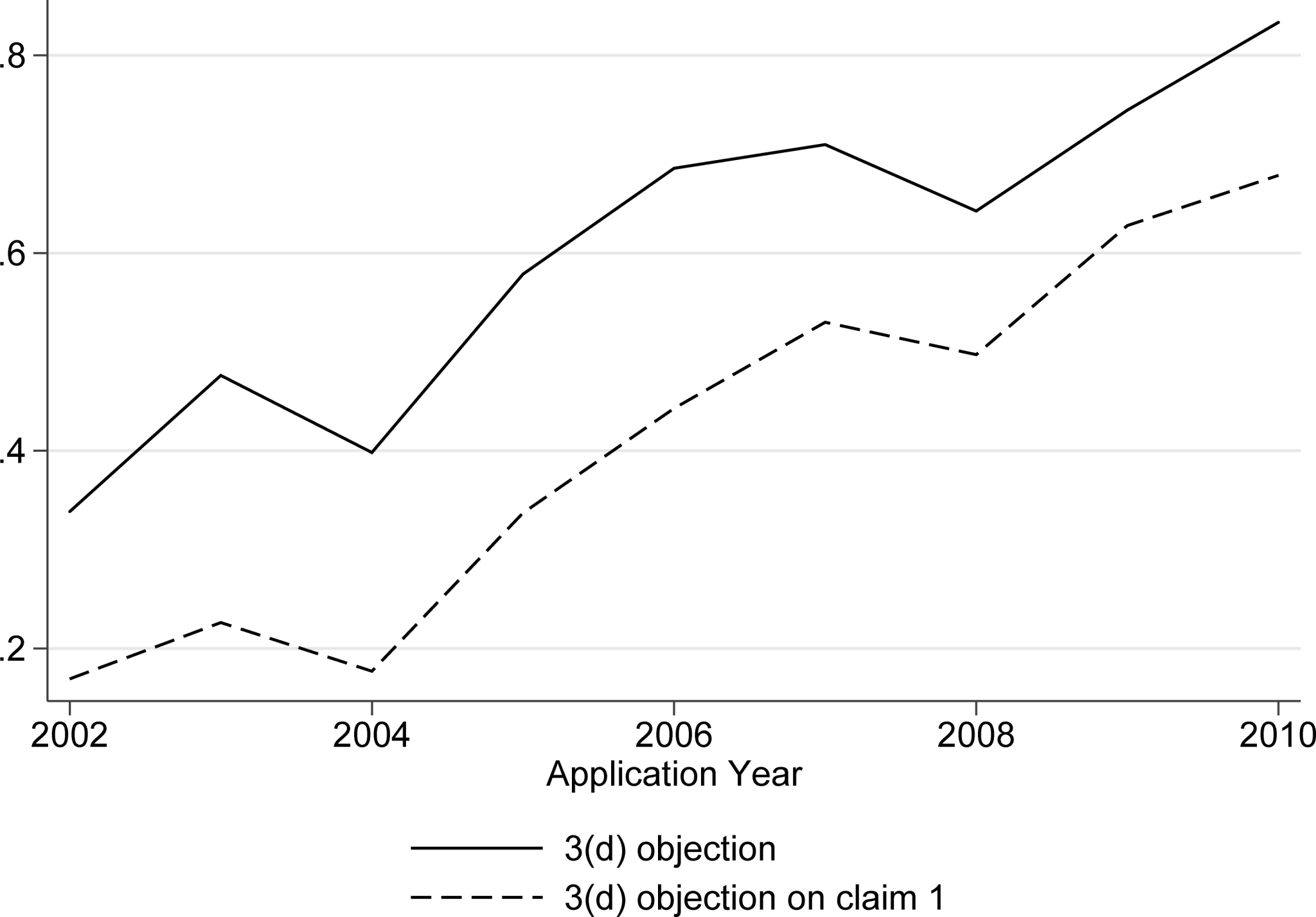

The cumulative result of aggressive lifecycle management is the creation of a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of dozens or even hundreds of patents covering a single drug product.8 AbbVie’s blockbuster biologic Humira is the canonical example, protected by a portfolio of over 100 patents that successfully delayed biosimilar competition in the U.S. for years after the expiration of its primary patent.61

The strategic power of the patent thicket extends beyond the legal force of any individual patent. The sheer volume of patents creates an almost insurmountable barrier for a would-be generic or biosimilar competitor. To launch its product, the competitor must either “design around” every single patent or challenge their validity in court—a process that is prohibitively expensive, time-consuming, and fraught with uncertainty.79 Data shows that this strategy is pervasive, with an average of 66% of patent applications on top-selling drugs being filed

after the drug has already received FDA approval.78 A key tool in building these thickets is the use of terminal disclaimers, which allow companies to obtain patents on obvious variants of an earlier invention, provided they expire on the same date. While these patents do not extend the overall patent term, they add to the number of patents a competitor must litigate, increasing the cost and complexity of a challenge.82

This dynamic reveals a deeper strategic layer: the patent thicket is designed to leverage the litigation process itself as the primary barrier to market entry. The goal is to create an economic and legal obstacle course so daunting that it forces potential competitors into settlement agreements that delay their launch, thereby preserving the brand’s monopoly revenue stream for additional years.79 The thicket transforms patents from mere tools of exclusion into strategic weapons of attrition.

Section 7: The Biologics Frontier: Unique Challenges in Patenting Large Molecules

The rise of biologics—large, complex molecules such as monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and cell therapies—has revolutionized medicine. However, their inherent complexity presents unique and formidable challenges for the patent system, requiring strategies that differ significantly from those used for traditional small-molecule drugs.

7.1 Defining the Undefinable: Claiming Antibodies and Complex Proteins

Unlike small-molecule drugs that can be precisely defined by a chemical formula, biologics are large, heterogeneous mixtures produced in living cell systems.17 An antibody, for example, is a massive protein whose final structure and function can be influenced by subtle variations in the manufacturing process, such as post-translational modifications like glycosylation.85

This structural complexity makes it difficult, if not impossible, to define a biologic solely by its structure in a patent claim. Consequently, patent drafters have historically relied heavily on a combination of structural and functional limitations. For instance, an antibody is often claimed by defining its target antigen, the specific epitope (binding site) on that antigen, and its functional ability to bind to that epitope and elicit a biological response (e.g., “An isolated monoclonal antibody that binds to amino acid residues 15-25 of protein X and inhibits the activity of protein X”).84 This reliance on functional claiming, which defines an invention by what it

does rather than what it is, became the central issue in the landmark Amgen v. Sanofi case.

7.2 Navigating the BPCIA and the Rise of Biosimilars

In the United States, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009 created an abbreviated regulatory pathway for the approval of biosimilars—the biologic equivalent of generic drugs.80 However, because biologics cannot be perfectly replicated, a biosimilar is defined as being “highly similar” to the reference product with “no clinically meaningful differences,” a standard that requires a much more extensive and costly development program than for a small-molecule generic.85

The BPCIA also established a complex and often-criticized patent dispute resolution process known as the “patent dance”.80 This series of information exchanges is intended to identify and streamline litigation over the patents covering the reference biologic. In practice, however, the process is often seen as cumbersome and ineffective, allowing brand manufacturers to leverage their extensive patent thickets to create significant delays and uncertainty for biosimilar developers, thereby deterring or postponing market entry.80

7.3 The Impact of AI on Inventorship and Obviousness in Biopharma

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into drug discovery is rapidly transforming the innovation landscape, presenting new challenges and questions for patent law.89 AI algorithms can now analyze vast biological datasets to identify novel drug targets, design new molecules

de novo, and predict their therapeutic properties, dramatically accelerating a process that traditionally took years.89 This technological shift has significant implications for patenting:

- Inventorship: Current U.S. patent law requires that an inventor be a human being; an AI system cannot be named as an inventor.89 This creates a critical need for companies using AI to meticulously document the “significant contribution” of their human scientists. This contribution could involve designing the AI model, curating the training data, defining the problem for the AI to solve, or experimentally validating and refining the AI’s output.89 Failure to demonstrate a sufficient human inventive contribution could render a patent invalid.

- Obviousness: The non-obviousness standard is measured from the perspective of a PHOSITA. As AI tools become more widespread and powerful, the capabilities of this hypothetical skilled person will evolve.89 A molecule or a discovery that would have been considered a brilliant, non-obvious leap for a human scientist might be deemed an obvious output for a skilled artisan equipped with a state-of-the-art AI platform. This will likely raise the bar for what is considered a patentable invention, requiring a greater degree of human ingenuity or the solution of a problem that was not amenable to standard AI approaches.

- Disclosure Requirements: The “black box” nature of many advanced AI models, where the internal logic is not easily interpretable, poses a significant challenge for satisfying the enablement and written description requirements of § 112.89 A patent application must teach a skilled person how to make and use the invention. If the invention was generated by an AI, the applicant must find a way to describe the process with sufficient detail to be enabling, without necessarily disclosing proprietary algorithms, a difficult line to walk.

Part IV: Navigating the Gauntlet of Litigation and Enforcement

A patent’s true value is only realized when it can withstand the crucible of litigation. The most artfully drafted claims are worthless if they are invalidated by a court. In recent years, the U.S. judiciary, led by the Supreme Court, has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of pharmaceutical patent law, imposing stricter standards for what must be disclosed in a patent and how clearly its boundaries must be defined. Understanding the doctrines shaped by these landmark cases is no longer optional; it is essential for drafting defensible, “bulletproof” claims.

Section 8: The Specter of Invalidation: Key Doctrines Shaped by Landmark Cases

The validity of a pharmaceutical patent in litigation most often hinges on the disclosure requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112 and the definiteness of the claims. A trio of recent Federal Circuit and Supreme Court decisions has dramatically raised the bar for patentees, particularly in the unpredictable arts of biotechnology and antibody engineering.

8.1 Enablement and Written Description Post-Amgen, Ariad, and Juno

The doctrines of written description and enablement, while distinct, are deeply intertwined and collectively ensure that the scope of the patent monopoly is justified by the inventor’s contribution to the art.

- Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co. (Fed. Cir. 2010): This seminal en banc Federal Circuit decision firmly established that the written description requirement is a separate and distinct legal standard from enablement.92 To satisfy the requirement, the patent specification must demonstrate that the inventor was in “possession” of the claimed invention as of the filing date.93 The court invalidated Ariad’s broad claims to methods of inhibiting the NF-κB pathway, reasoning that the patent described a scientific problem and hypothesized potential solutions but did not disclose any specific molecules that could achieve the claimed result. The ruling stands for the critical principle that a patent cannot simply claim a desired outcome and preempt all future solutions; it must describe an actual, invented solution.92

- Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021): The Federal Circuit applied the Ariad “possession” test with devastating effect in this case, which involved a foundational patent for CAR-T cancer therapy. The court invalidated claims that were directed to a genus of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) defined by a functional limitation—a binding element (scFv) capable of binding to a selected target.30 Although the patent disclosed two working examples of scFvs, the court held this was insufficient to demonstrate possession of the vast, potentially limitless genus of all possible scFvs that could perform the claimed function, particularly in the unpredictable field of antibody engineering.97 The decision reversed a jury verdict and wiped out a staggering $1.2 billion damages award, sending shockwaves through the biotech industry.30

- Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi (U.S. 2023): The Supreme Court provided the capstone to this line of jurisprudence in a unanimous decision that has reshaped the strategy for patenting biologics. The case involved Amgen’s patents claiming a whole genus of antibodies defined by their function: binding to a specific site on the PCSK9 protein and blocking its action.101 Amgen’s patent disclosed the structures of 26 exemplary antibodies and provided a “roadmap” for scientists to generate and test other antibodies to see if they fell within the claim.103 The Court held this was not enough. Affirming the lower courts, it ruled that the enablement requirement of § 112 demands that the specification must teach a PHOSITA how to make and use the

full scope of the claimed invention without “undue experimentation”.31 The Court characterized Amgen’s roadmap as little more than a “research assignment” or a “hunting license” that required “painstaking experimentation” to practice.101 The decision’s central, and now frequently quoted, holding is a simple but powerful directive:

“The more one claims, the more one must enable.”.31

These cases, taken together, represent a significant judicial recalibration of the patent bargain. The courts have signaled a clear skepticism towards broad, functionally-defined genus claims, especially in unpredictable fields like immunology. The era of securing a vast monopoly based on an initial breakthrough discovery, without providing a detailed and representative disclosure of how to achieve the full scope of that claim, is over. This “new quid pro quo” demands that the inventor’s disclosure (quid) be truly commensurate with the scope of the monopoly being sought (quo), effectively invalidating patents that are perceived as speculative attempts to “preempt the future before it has arrived”.96 The commercial impact is profound: it raises the bar for patentability for early-stage platform technologies, potentially shifting investment towards innovations that are more fully characterized, and creates new opportunities for competitors to design around patents with narrower, structurally defined claims.108

8.2 Definiteness After Nautilus and Teva

The definiteness requirement ensures that the public receives clear notice of the patent’s boundaries. Two Supreme Court cases have clarified the standard for this requirement and how it is reviewed on appeal.

- Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc. (U.S. 2014): In this case, the Supreme Court addressed the standard for determining whether a claim is unpatentably indefinite under § 112. It rejected the Federal Circuit’s previously lenient standard, which held a claim indefinite only if it was “insolubly ambiguous”.111 The Court established a stricter test: a patent is invalid for indefiniteness if its claims, when “read in light of the specification delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention”.111 This “reasonable certainty” standard compels patent drafters to be more precise and to avoid ambiguous terms, especially terms of degree like “about” or “substantially,” unless the specification provides objective boundaries to guide their interpretation.116

- Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc. (U.S. 2015): This case concerned the definiteness of the term “molecular weight” in patents covering the blockbuster multiple sclerosis drug, Copaxone.118 The core legal issue, however, was the standard of appellate review for claim construction rulings. The Supreme Court held that while the ultimate interpretation of a patent claim is a question of law that is reviewed

de novo (without deference), any underlying factual findings made by the district court to resolve ambiguity—such as those based on conflicting expert testimony about how a PHOSITA would understand a technical term—must be reviewed with deference under the “clear error” standard.118 This decision elevated the importance of the trial court record, particularly the evidence and expert testimony presented during

Markman (claim construction) hearings, making them a more critical battleground in patent litigation.

The following table summarizes these landmark decisions and their direct impact on the practice of drafting and litigating pharmaceutical patent claims.

Table 2: Landmark U.S. Patent Cases and Their Impact on Pharmaceutical Claim Drafting

| Case | Key Legal Doctrine | Core Holding | Practical Impact on Claim Drafting |

| Ariad v. Eli Lilly (2010) | Written Description (§ 112) | Confirmed written description is a separate “possession” test. A patent cannot merely describe a problem and claim all solutions. | Requires disclosure of representative species or common structural features for a genus. Functional claiming without structural support is highly vulnerable. |

| Nautilus v. Biosig (2014) | Definiteness (§ 112) | A claim is indefinite if it fails to inform a PHOSITA of its scope with “reasonable certainty.” | Heightened need for clarity. Avoid ambiguous terms of degree unless objectively defined in the specification. |

| Teva v. Sandoz (2015) | Claim Construction (Standard of Review) | Appellate courts must defer to a district court’s factual findings underlying claim construction, reviewing them only for “clear error.” | Increases the importance of expert testimony and evidence presented at the district court level during Markman hearings. |

| Juno v. Kite (2021) | Written Description (§ 112) | Invalidated broad functional genus claims for a CAR-T therapy for failing to show possession of the vast number of scFvs claimed. | Reinforces the high bar for written description in unpredictable arts. Two examples are insufficient to support a vast functional genus. |

| Amgen v. Sanofi (2023) | Enablement (§ 112) | The specification must enable the full scope of a genus claim without undue experimentation. “The more you claim, the more you must enable.” | Severely curtails the viability of broad, functionally-defined genus claims for antibodies and other biologics. Increases the need for extensive data and working examples prior to filing. |

Section 9: From Theory to Practice: Recommendations for Drafting Bulletproof Claims

The ultimate goal of a patent strategist is to draft claims that not only secure a patent grant but also survive the rigors of litigation and provide durable market exclusivity. This requires a proactive approach that begins long before the application is filed and integrates legal, scientific, and commercial considerations at every step.

9.1 Pre-Filing Diligence: The Critical Role of FTO and Landscape Analysis

A successful patent strategy does not begin with drafting; it begins with intelligence gathering. Two types of analysis are indispensable:

- Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: An FTO analysis (also known as a clearance search) is a focused inquiry to determine whether a planned commercial product or process is likely to infringe the in-force patent claims of others in a specific jurisdiction.122 Conducting an FTO analysis before committing significant resources to clinical development and commercial launch is a critical risk-mitigation step. It can identify potential “blocking patents” that may require a license, a design-around, or a validity challenge, thereby preventing costly infringement litigation down the road.122

- Patent Landscape Analysis: This is a broader, more strategic analysis of the patent activity within a particular technology sector.127 By mapping who is patenting what, where, and when, a landscape analysis can reveal:

- Key Players and Competitors: Identifying the dominant patent holders in a field.87

- Technology Trends: Understanding the direction of R&D and identifying emerging technologies.127

- “White Space” Opportunities: Discovering areas with limited patent activity that may represent untapped opportunities for innovation.127

This intelligence is invaluable for guiding R&D strategy, identifying potential collaborators or acquisition targets, and informing the direction of a company’s own patenting efforts.87

9.2 Drafting with Foresight: Anticipating Examiner Rejections and Litigant Attacks

The specification and claims should be drafted not just for the patent examiner, but with an eye toward a hypothetical future courtroom battle against a well-funded and motivated adversary.

- Provide a Rich and Detailed Disclosure: In the post-Amgen world, the specification is paramount. It must be a comprehensive repository of scientific data, including working examples, comparative data, and detailed descriptions of alternative embodiments.13 This rich disclosure provides the necessary support to satisfy the heightened standards for enablement and written description, and it creates a foundation for a tiered claiming strategy with multiple fallback positions.131

- Act as Your Own Lexicographer: Do not leave the meaning of critical claim terms to chance or the interpretation of a future judge. Use the specification as a glossary to provide clear, explicit definitions for any potentially ambiguous terms.19 This allows the patentee to control the narrative during claim construction and ensure the claims are interpreted as intended.

- Avoid “Patent Profanity”: The specification should be scrubbed of any language that could be used to unnecessarily limit the scope of the claims. Words like “essential,” “critical,” “necessary,” “must,” or “only” can be seized upon by a litigant to argue that a feature described with such emphasis is a mandatory element of all claims, even if not explicitly recited.132

- Draft for Literal Infringement: While the doctrine of equivalents exists to capture non-literal infringements, its application has been significantly narrowed by the courts. A patent drafter should never rely on it.132 Claims should be crafted to be clearly and literally infringed by a competitor’s most likely product configuration. This requires a deep understanding of the competitive landscape and anticipating how a competitor might attempt to design around the core invention.

9.3 Harmonizing Global Portfolios: Tailoring Claim Strategies for Key Jurisdictions

Pharmaceuticals is a global industry, and an effective patent strategy must be global in scope. A “one-size-fits-all” approach to claim drafting is destined for failure, as the legal standards and procedural nuances vary significantly between key jurisdictions like the U.S., Europe, and Asia.133

A harmonized global strategy requires careful coordination and adaptation. For example, a single priority application must contain sufficient disclosure to support a U.S.-style method of treatment claim, an EPO-style second medical use claim, and potentially different claim structures for markets like China or Japan.36 It requires an understanding of the different approaches to assessing inventive step, the absolute novelty bar in Europe, and varying standards for the sufficiency of data required at the time of filing.34 This demands a sophisticated, forward-looking approach that builds flexibility into the initial patent application to accommodate the unique requirements of each major market.

Conclusion

The art and science of drafting pharmaceutical patent claims represent a discipline of immense complexity and consequence. It is a practice situated at the dynamic intersection of cutting-edge science, arcane legal doctrine, and high-stakes commercial strategy. The “science” lies in the meticulous, data-rich disclosure required to meet the stringent statutory requirements of patentability—a standard that has been significantly elevated by recent judicial scrutiny. The “art” lies in the strategic crafting of language to define a legal boundary that is broad enough to provide meaningful market exclusivity, yet precise enough to withstand invalidity attacks and clear enough to provide notice to the public.

The foundational “patent bargain”—a limited monopoly in exchange for public disclosure—remains the economic engine of the pharmaceutical industry. However, the judiciary, particularly in the United States, has recalibrated the terms of this bargain. Landmark decisions like Ariad, Juno, and Amgen v. Sanofi have imposed a “new quid pro quo,” demanding a far more robust and comprehensive disclosure from inventors who seek broad patent protection, especially in the unpredictable realm of biologics. The era of claiming a “research assignment” is over; the courts now demand proof of possession and a clear roadmap to practice the full scope of the invention.

In this challenging environment, success requires a multi-layered and forward-thinking IP strategy. It begins with rigorous pre-filing intelligence to map the competitive and technical landscape. It proceeds with the drafting of a rich specification that can support a tiered claim structure, combining broad independent claims with a cascade of narrower, dependent fallbacks. It evolves throughout the drug’s lifecycle, employing secondary patents on formulations, new uses, and other follow-on innovations to manage the patent cliff and maximize the return on investment. Finally, it must be global in its outlook, tailoring claim strategies to the unique legal requirements of key international markets.

Ultimately, a well-drafted patent claim is more than a legal instrument; it is the culmination of scientific discovery and strategic foresight, forged into a durable commercial asset that can secure the investment necessary to transform a molecule in a lab into a medicine that saves lives. Mastering this discipline is, and will remain, essential to the continued success and innovation of the global pharmaceutical enterprise.

Works cited

- Pharma forum 2022: three hot IP issues for the pharmaceutical industry – Taylor Wessing, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.taylorwessing.com/en/insights-and-events/insights/2022/08/pharma-forum-2022-three-hot-ip-issues-for-pharmaceutical-industry

- Drug development cost pharma $2.2B per asset in 2024 as GLP-1s drive financial return, accessed July 30, 2025, https://tentelemed.com/drug-development-cost-pharma-2-2b-per-asset-in-2024-as-glp-1s-drive-financial-return/

- Measuring the return from pharmaceutical innovation 2024 | Deloitte US, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/articles/measuring-return-from-pharmaceutical-innovation.html

- The Economics of Drug Discovery and the Impact of Patents – R Street Institute, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-economics-of-drug-discovery-and-the-impact-of-patents/

- Pharmaceutical Life Cycle Management | Torrey Pines Law Group®, accessed July 30, 2025, https://torreypineslaw.com/pharmaceutical-lifecycle-management.html

- Does Pharma Need Patents? – Yale Law Journal, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/feature/does-pharma-need-patents

- Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in the United States – The Actuary …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.theactuarymagazine.org/pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-the-united-states/

- What is the difference between a product claim and a use claim in pharmaceutical patents?, accessed July 30, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-product-claim-and-a-use-claim-in-pharmaceutical-patents

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Strategies to Maximize Product Value Amid Loss of Exclusivity in the …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/strategies-to-maximize-product-value-amid-loss-of-exclusivity-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry/

- patent | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/patent

- Teva Canada Ltd. V. Pfizer Canada Inc., 2012 SCC 60 (2012) Supreme Court of Canada Prepared by UNCTAD’s Intellectual Property, accessed July 30, 2025, https://unctad.org/ippcaselaw/sites/default/files/ippcaselaw/2020-12/Teva%20Canada%20Ltd.%20v%20Pfizer%20Supreme%20Court%20of%20Cananda%202012.pdf

- Who Cares What Thomas Jefferson Thought about Patents – Reevaluating the Patent Privilege in Historical Context – Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository, accessed July 30, 2025, https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3067&context=clr

- Filing Strategies for Maximizing Pharma Patents: A Comprehensive Guide for Business Professionals – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/filing-strategies-for-maximizing-pharma-patents/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Patents vs. Market Exclusivity: Why Does it Take so Long to Bring Generics to Market?, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2016/8/patents-vs-market-exclusivity-why-does-it-take-s

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Duration and Market Exclusivity – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- How Long Does Patent Protection Last for Biologics? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 30, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/how-long-does-patent-protection-last-for-biologics

- Drug Patent and Exclusivity Study available – USPTO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration/drug-patent-and-exclusivity-study-available

- WIPO Patent Drafting Manual_Second Edition, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo-pub-867-23-en-wipo-patent-drafting-manual.pdf

- USPTO Community College Pilot: Conditions for Patentability – YouTube, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i7oZ_QFt4SM

- Specific Requirements of p q Patentability – WIPO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/aspac/en/wipo_ip_kul_11/wipo_ip_kul_11_ref_t22.pdf

- What are the five requirements for patentability? – Christensen Fonder Dardi Herbert PLLC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.cfd-ip.com/blog/2021/04/what-are-the-five-requirements-for-patentability/

- Patent Requirements – BitLaw, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.bitlaw.com/patent/requirements.html

- A Quick Guide to Pharmaceutical Patents and Their Types – PatSeer, accessed July 30, 2025, https://patseer.com/a-quick-guide-to-pharmaceutical-patents-and-their-types/

- Patents Supreme Court Cases, accessed July 30, 2025, https://supreme.justia.com/cases-by-topic/patents/

- What is Patentable? Everything You Need To Know About USPTO Patentability Requirements – The Rapacke Law Group, accessed July 30, 2025, https://arapackelaw.com/patents/what-is-patentable/

- How “Novel” or “Non-Obvious” Must an Invention Be To Be Eligible for Patent Protection?, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.mololamken.com/knowledge-how-novel-or-non-obvious-must-an

- Understanding Non Obvious Examples for Patent Protection – UpCounsel, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.upcounsel.com/non-obvious

- Non-Obviousness – Duke Law School, accessed July 30, 2025, https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/papers/pdf/ipcasebook_chap-21.pdf

- Written Description Remains Critical to Patents – Weintraub Tobin, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.weintraub.com/2021/10/written-description-remains-critical-to-patents/

- 2164-The Enablement Requirement – USPTO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2164.html

- 2173-Claims Must Particularly Point Out and Distinctly Claim the …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2173.html

- Is it patentable? | epo.org, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/new-to-patents/is-it-patentable

- A Guide to European Patent Applications | Intellectual Property – Murgitroyd, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.murgitroyd.com/us/insights/patents/european-patent-applications

- What is patentable? | epo.org, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/news-events/in-focus/biotechnology-patents/what-is-patentable

- Primer for Patenting Methods of Treatment – Workman Nydegger, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.wnlaw.com/blog/primer-for-patenting-methods-of-treatment/

- Everything to Know about Patent Claims: Functions, Parts, and Types, accessed July 30, 2025, https://sagaciousresearch.com/blog/everything-to-know-about-patent-claims-functions-parts-and-types/

- What is a Patent Claim? …It Defines Your Patent Rights, accessed July 30, 2025, https://sierraiplaw.com/what-is-a-patent-claim/

- Understanding the Different Types of Patent Claims – PatentPC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/understanding-the-different-types-of-patent-claims-2

- PATENT CLAIM FORMAT AND TYPES OF CLAIMS – WIPO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/aspac/en/wipo_ip_phl_16/wipo_ip_phl_16_t5.pdf

- Composition of Matter Patents – (Intro to Pharmacology) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations, accessed July 30, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-pharmacology/composition-of-matter-patents

- Using Solid Form Patents to Protect Pharmaceutical Products — Part I, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.ebarashlaw.com/insights/part1

- Types of Pharmaceutical Patents – O’Brien Patents, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.obrienpatents.com/types-pharmaceutical-patents/

- How to Draft Patent Claims for Chemical Inventions – PatentPC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-to-draft-patent-claims-for-chemical-inventions

- What is the difference between a composition claim and a method of use claim?, accessed July 30, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-composition-claim-and-a-method-of-use-claim

- Patent claims’ scope – is bigger always better? Trends in the pharmaceuticals industry., accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pearlcohen.com/patent-claims-scope-is-bigger-always-better-trends-in-the-pharmaceuticals-industry/

- List of patent claim types – Wikipedia, accessed July 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_patent_claim_types

- The value of method of use patent claims in protecting your …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-value-of-method-of-use-patent-claims-in-protecting-your-therapeutic-assets/

- What are the types of pharmaceutical patents? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 30, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/blog/what-are-the-types-of-pharmaceutical-patents

- Method of Treatment Claims Are Patent Eligible and Are Not Simply …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/insights-news/method-of-treatment-claims-are-patent-eligible-and-are-not-simply-directed-to-a-natural-law

- Is a method of treatment patentable in the US? – Patent Trademark Blog | IP Q&A, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.patenttrademarkblog.com/method-of-treatment-patentable/

- Warner Lambert v Actavis: Supreme Court considers medical use …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.jakemp.com/knowledge-hub/warner-lambert-v-actavis-supreme-court-considers-medical-use-claims/

- Dosage regimen patents at the EPO part (II): Recent case law …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.kilburnstrode.com/knowledge/european-ip/dosage-regimen-patents-epo-part-ii-recent-case-law

- Key Considerations for Dosage Regimen Patents – A Comparative Analysis of EPO, UK, and US Case Law – Michalski · Hüttermann, accessed July 30, 2025, https://mhpatent.de/en/blog/wichtige-erwgungen-fr-patente-auf-dosierungsschemata-eine-vergleichende-analyse-der-rechtsprechung-des-epa-des/

- Extending the market exclusivity of therapeutic antibodies through dosage patents – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4968089/

- Patentability of dosage regimen claims – Regimbeau, accessed July 30, 2025, https://regimbeau.eu/en/insight/patentability-of-dosage-regimen-claims/

- 2113-Product-by-Process Claims – USPTO, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2113.html

- Drafting Effective Patent Claims: Techniques and Pitfalls to Avoid – Gearhart Law, accessed July 30, 2025, https://gearhartlaw.com/drafting-effective-patent-claims-techniques-and-pitfalls-to-avoid/

- Claim Strategies for Patent Applications: Can Your Patent Claims …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://henry.law/blog/can-your-patent-claims-ever-be-too-narrow/

- Picture Claims as an Effective Patent Strategy: Top 10 Reasons to Precisely Tailor Your Patent Claim | Mintz, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2231/2023-09-06-picture-claims-effective-patent-strategy-top-10-reasons

- The Economics of the Pharmaceutical Sector: Innovation, Competition, and Patent Policy, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-economics-of-the-pharmaceutical-sector-innovation-competition-and-patent-policy/

- Top 10 pharma R&D budgets in 2024 – Fierce Biotech, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/special-reports/top-10-pharma-rd-budgets-2024

- Evolving Pharmaceutical Strategies in a Post-Blockbuster World: Navigating Innovation, Access, and Market Dynamics – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/evolving-pharmaceutical-strategies-in-a-post-blockbuster-world/

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/

- Does Drug Patent Evergreening Prevent Generic Entry – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/does-drug-patent-evergreening-prevent-generic-entry/

- EXPLOITATION OF PATENTS: A STUDY OF EVERGREENING IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL DOMAIN, accessed July 30, 2025, https://nluassam.ac.in/docs/Journals/IPR/vol1-issue-2/10.pdf

- ‘Evergreenwashing’ the Pharmaceutical Patents Review – patentology, accessed July 30, 2025, https://blog.patentology.com.au/2013/06/evergreenwashing-pharmaceutical-patents.html

- Journal of Chemical Health Risks Understanding Evergreening of Patents in the Pharmaceutical Industry, accessed July 30, 2025, https://jchr.org/index.php/JCHR/article/download/8397/4799/15875

- Unmasking Evergreening: Navigating the Pharmaceutical Labyrinth, accessed July 30, 2025, https://cipit.strathmore.edu/unmasking-evergreening-navigating-the-pharmaceutical-labyrinth/

- Unmasking Evergreening: Navigating the Pharmaceutical Labyrinth, accessed July 30, 2025, https://cipit.org/unmasking-evergreening-navigating-the-pharmaceutical-labyrinth/

- Is Patent “Evergreening” Restricting Access to Medicine/Device Combination Products?, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/is-patent-evergreening-restricting-access-to-medicine-device-combination-products/

- Patent Database Exposes Pharma’s Pricey “Evergreen” Strategy, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.uclawsf.edu/2020/09/24/patent-drug-database/

- Patenting of Polymorphs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.4155/ppa-2017-0039

- (PDF) Patenting of polymorphs – ResearchGate, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323865500_Patenting_of_polymorphs

- Crystallized Control: Unlocking the Secrets to Polymorph Patents – Kan and Krishme, accessed July 30, 2025, https://kankrishme.com/crystallized-control-unlocking-thesecrets-to-polymorph-patents/

- Patent Protection of Pharmacologically Active Metabolites: Theoretical and Technological Analysis on the Jurisprudence of Four R, accessed July 30, 2025, https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1565&context=chtlj

- Intellectual Property Rights and the Evergreening of Pharmaceuticals – Intereconomics, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2015/number/4/article/intellectual-property-rights-and-the-evergreening-of-pharmaceuticals.html

- Addressing Patent Thickets To Improve Competition and … – I-MAK, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Addressing-Patent-Thickets-Blueprint_2023.pdf

- COMPETING WITH PATENT THICKETS … – Boston University, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2022/03/HUSTAD.pdf

- The Patent Trap: The Struggle for Competition and Affordability in the Field of Biologic Drugs – Columbia Journal of Law & Social Problems, accessed July 30, 2025, https://jlsp.law.columbia.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/213/files/2021/11/Vol.-54-Geaghan-Breiner.pdf

- Untangling Patent Thickets: The Hidden Barriers Stifling Innovation – TT CONSULTANTS, accessed July 30, 2025, https://ttconsultants.com/untangling-patent-thickets-the-hidden-barriers-stifling-innovation/

- Biologic Patent Thickets and Terminal Disclaimers – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10722383/

- The Debate Over Patent Thickets – Applied Policy, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.appliedpolicy.com/the-debate-over-patent-thickets/

- Addressing Patent Challenges in Biologics and Biosimilars – PatentPC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/addressing-patent-challenges-biologics-and-biosimilars

- Exploring Biosimilars as a Drug Patent Strategy: Navigating the Complexities of Biologic Innovation and Market Access – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/exploring-biosimilars-as-a-drug-patent-strategy-navigating-the-complexities-of-biologic-innovation-and-market-access/

- Amgen v. Sanofi: Critical Impact on the Value of Innovative Science in Antibody Discovery, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10809895/

- Strategies for Patenting Biotechnology in Drug Development – PatentPC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/strategies-for-patenting-biotechnology-drug-development

- Biosimilars: Patent challenges and competitive effects – Morgan Lewis, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.morganlewis.com/-/media/files/publication/outside-publication/article/lmg_mann-mahinka-biosimilarspatentcallenges_sept2014.pdf

- Patenting Drugs Developed with Artificial Intelligence: Navigating the Legal Landscape, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/patenting-drugs-developed-with-artificial-intelligence-navigating-the-legal-landscape/

- The Implications of AI-Assisted Drug Development on Patent Challenges – Perspectives, accessed July 30, 2025, https://perspectives.bipc.com/post/102k8yy/the-implications-of-ai-assisted-drug-development-on-patent-challenges

- AI is flooding the zone with patents. How can they be more reliable? – Duke Law School, accessed July 30, 2025, https://law.duke.edu/news/ai-flooding-zone-patents-how-can-they-be-more-reliable

- Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co. | Case Brief for Law Students | Casebriefs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.casebriefs.com/blog/law/intellectual-property-law/intellectual-property-keyed-to-merges/patent-law-intellectual-property-keyed-to-merges/ariad-pharmaceuticals-inc-v-eli-lilly-co/

- Ariad v. Lilly: Written Description Requirement Separate from …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/ariad-v-lilly-written-description-requirement-separate-from.html

- Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co. Case Brief Summary – YouTube, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u0OWlj5sYjI

- Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co. – Wikipedia, accessed July 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ariad_Pharmaceuticals,_Inc._v._Eli_Lilly_%26_Co.

- Case Update: Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly and Company – Finnegan, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/ip-updates/case-update-ariad-pharmaceuticals-inc-v-eli-lilly-and-company.html

- Juno v. Kite: Written Description and Claiming Antibodies and Chimeric Antigen Receptors—Lessons for Patent Prosecutors – Insights – Proskauer Rose LLP, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.proskauer.com/blog/juno-v-kite-written-description-and-claiming-antibodies-and-chimeric-antigen-receptorslessons-for-patent-prosecutors

- Juno v Kite Case Implications For Functionally Claimed Biological Compositions, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.outsourcedpharma.com/doc/juno-v-kite-case-implications-for-functionally-claimed-biological-compositions-0001

- Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021) – Patent Docs, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.patentdocs.org/2021/08/juno-therapeutics-inc-v-kite-pharma-inc-fed-cir-2021.html

- JUNO THERAPEUTICS, INC. v. KITE PHARMA, INC. – U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/opinions-orders/20-1758.opinion.8-26-2021_1825257.pdf