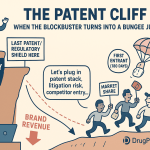

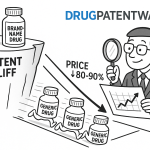

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceuticals, the transition from a branded drug monopoly to a competitive generic market is one of the most significant and disruptive events a company can face. For brand-name manufacturers, it represents a “patent cliff” that can wipe out 80-90% of a blockbuster drug’s revenue—often billions of dollars—within a year or two of generic entry . For generic companies, it’s a race to capture a piece of that market, a race where being first can mean the difference between a highly profitable launch and a fight for pennies in a commoditized space. For investors, insurers, and wholesalers, predicting the timing of this shift is critical for forecasting, risk management, and strategic planning.

Many view the prediction of generic drug launches as a dark art, a matter of guesswork and opaque industry intelligence. This is a profound misconception. The reality is that the U.S. regulatory and legal framework, architected primarily by the Hatch-Waxman Act, was designed to create a predictable, albeit complex, series of public signals. It doesn’t just allow for generic competition; it choreographs the entire conflict. Identifying a future generic entrant isn’t about gazing into a crystal ball; it’s about learning to read the sheet music.

The challenge lies not in a lack of information, but in its synthesis. The clues are scattered across FDA databases, federal court dockets, corporate SEC filings, and investor presentations. A PIV filing here, a Markman ruling there, a subtle shift in language on an earnings call—each is a breadcrumb. Individually, they are noise. When pieced together, they form a clear, actionable trail leading directly to a future generic launch.

This report is your guide to navigating that trail. We will deconstruct the intricate machinery of the Hatch-Waxman Act, transforming its legal and regulatory jargon into a clear set of predictive signals. We will move from the foundational concepts of patent certifications to the advanced, actionable strategies of tracking litigation, decoding settlement agreements, and integrating broad competitive intelligence. This is the pre-approval playbook, designed to empower you to anticipate market-shaping events, mitigate risk, and turn public data into a decisive competitive advantage. The stakes are immense, with generic medicines saving the U.S. healthcare system a staggering $408 billion in 2022 alone, a testament to the power of the competition we are about to predict .

Section 1: The Arena of Competition – Decoding the Hatch-Waxman Framework

To predict the moves in any game, you must first understand the rules of the board. In the world of generic pharmaceuticals, that board was designed in 1984 by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, more famously known as the Hatch-Waxman Act . This landmark legislation is the bedrock of modern pharmaceutical competition in the United States, and mastering its logic is the first and most critical step in identifying future generic entrants.

A Tale of Two Goals: Balancing Innovation and Affordability

Before 1984, the system was broken, serving neither innovation nor affordability well. Brand-name drug manufacturers saw their effective patent life eroded by the lengthy FDA approval process, disincentivizing risky R&D investment. At the same time, would-be generic competitors faced an insurmountable barrier: they had to conduct their own duplicative and costly clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, even for a molecule that had been on the market for years . The result? Generic drugs were a rarity, accounting for just 19% of prescriptions, and it could take years after a patent expired for a lower-cost alternative to reach patients .

The Hatch-Waxman Act was a grand bargain designed to fix both problems simultaneously . For innovators, it offered a vital concession: the ability to apply for Patent Term Extensions (PTEs) to restore a portion of the patent life lost during the FDA’s review period, ensuring they had a meaningful period of market exclusivity to recoup their investment . As Senator Orrin Hatch, one of the bill’s namesakes, intended, this was meant to shore up the incentive for groundbreaking research.

For generic manufacturers, the Act created a revolutionary new pathway: the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) . This pathway allowed a generic company to get its product approved without repeating clinical trials. Instead, it could rely on the FDA’s previous finding of safety and effectiveness for the brand-name drug (the “Reference Listed Drug” or RLD) and simply prove that its own version was bioequivalent—delivering the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream in the same amount of time .

This structure fundamentally altered the landscape. However, the true genius of the Act, from a predictive standpoint, lies in how it managed the inevitable conflict over patents. To conduct bioequivalence testing, a generic company needed to use the patented drug during its patent term, which was technically patent infringement. The Act created a “Safe Harbor,” exempting such pre-approval activities from infringement lawsuits . But this raised a new question: how to resolve patent disputes before a generic company made a massive, “at-risk” investment in a commercial launch?

The Act’s elegant and confrontational solution was to define the very act of filing an ANDA that challenges a patent as an “artificial act of infringement” . This allowed the brand-name company to sue the generic manufacturer for patent infringement immediately, long before the generic product ever reached a pharmacy shelf. This entire structure—the Safe Harbor, the ANDA pathway, and the artificial act of infringement—was deliberately constructed to force patent disputes out into the open and resolve them during a predictable, structured timeframe. The signals we track today—the lawsuits, the stays, the settlements—are not accidental byproducts of the system; they are its intended output. The Act is not merely a regulatory process; it is a structured conflict resolution system, and its every step is a potential predictive data point.

“Although it has been a tremendous success in promoting competition and innovation, there are clearly weaknesses in the Hatch-Waxman Act, and today, of the top 15 best-selling drugs potentially subject to generic competition, the basic patents on at least five of them have long expired. Their exclusive rights to market their drugs have long expired. Yet there is no generic competition. Clearly, the system needs to be repaired.” – **Statement from a 2002 Congressional Hearing on Competition in the Pharmaceutical Industry **

The Language of Entry: Understanding the ANDA and Patent Certifications

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must address every patent that the brand-name manufacturer has listed with the FDA as covering its drug. This list of patents is published in the FDA’s official publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, universally known as the “Orange Book” . For each and every patent listed in the Orange Book for the reference drug, the ANDA filer must make a formal declaration, known as a patent certification .

There are four types of certifications, and understanding them is like learning the fundamental vocabulary of generic entry. Each one is a clear statement of intent that signals a different strategy and a different timeline for market entry.

Table 1: The Four Paragraph Certifications and Their Strategic Implications

| Certification | Formal Meaning | Strategic Signal & Implied Timeline |

| Paragraph I | No patent information on the drug has been filed with the FDA. | Signal: No patent obstacles exist. Timeline: Approval is possible as soon as the ANDA review is complete. This is rare for new drugs. |

| Paragraph II | The patent listed in the Orange Book has already expired. | Signal: The patent barrier has been removed by time. Timeline: Approval is possible as soon as the ANDA review is complete. |

| Paragraph III | The listed patent has not yet expired, and the generic company will wait until the patent’s expiration date to launch. | Signal: A non-confrontational approach. The generic company is signaling it will not challenge the patent’s validity. Timeline: A predictable launch date. The ANDA can be approved, but the launch is deferred until the specific date of patent expiration. |

| Paragraph IV (PIV) | The listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the proposed generic product. | Signal: A direct challenge and a declaration of war. This is the most aggressive and information-rich signal. Timeline: Signals intent for a pre-patent-expiry launch. Triggers a potential 45-day window for a lawsuit and a 30-month stay of approval. The battle begins now. |

A Paragraph I or II certification is straightforward; it signals that the coast is clear from a patent perspective. A Paragraph III certification is essentially a public scheduling announcement; the generic company is placing a bet that the market will still be profitable when the patent expires, and it gives competitors a clear timeline of their intentions.

But the Paragraph IV (PIV) certification is where the real action lies. It is a bold claim that a brand’s government-granted monopoly is either illegitimate or irrelevant to the generic’s product. This is the “artificial act of infringement” that ignites the Hatch-Waxman process . The filing of an ANDA with a PIV certification is the single most important early signal that a competitive battle is about to begin, and it sets in motion a cascade of predictable events that a savvy analyst can track.

Section 2: The Shot Across the Bow – The Paragraph IV Certification as the Ultimate Early Signal

If the Hatch-Waxman framework is the arena, the Paragraph IV certification is the sound of the starting gun. It transforms a company’s private strategic decision into a public declaration of intent to enter a protected market before a patent’s natural expiration. For the competitive intelligence analyst, this is ground zero. All subsequent signals—litigation, regulatory stays, settlements—emanate from this initial act of defiance. Understanding the mechanics and implications of a PIV filing is therefore non-negotiable for anyone seeking to predict a generic launch.

The PIV Notice Letter: A Declaration of War

The filing of an ANDA with a PIV certification with the FDA is the first step, but it is the next step that officially starts the clock on the conflict. The generic applicant is legally required to notify the brand-name New Drug Application (NDA) holder and the owner of the patent(s) being challenged . This notification, known as a “PIV notice letter,” is a formal, detailed document that serves as a declaration of war.

The timing of this letter is strictly regulated and highly significant. A generic applicant cannot simply file its ANDA and send the notice letter on the same day. First, it must receive an acknowledgment letter from the FDA confirming that its ANDA has been received and is sufficiently complete to be accepted for substantive review . Once the generic company has this acknowledgment in hand, a new clock starts: it has just 20 days to send the PIV notice letter to the brand and patent holder . This precise, narrow window is a key predictive element.

The contents of the PIV notice letter are also prescribed by law and are a treasure trove of intelligence. The letter must include a detailed statement outlining the full factual and legal basis for the generic company’s opinion that the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed . This isn’t a casual claim; it’s the opening argument in a multi-million-dollar legal battle, and it must be scientifically and legally vetted. Furthermore, if the generic company is arguing non-infringement (i.e., that its product is designed around the patent claims), it must include an Offer of Confidential Access (OCA). This OCA provides a mechanism for the brand’s lawyers to review confidential sections of the ANDA to evaluate the non-infringement claim before deciding which patents to assert in a lawsuit .

While the PIV notice letter itself is confidential, its existence is often the first public signal of a challenge. Publicly traded brand-name companies have a duty to disclose material events to their investors. The receipt of a PIV notice on a blockbuster drug, representing a direct threat to a major revenue stream, is almost always considered a material event. Consequently, brand companies will typically disclose the receipt of such a notice in a Form 8-K filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or in their next quarterly (10-Q) or annual (10-K) report. Monitoring these filings is one of the most reliable methods for confirming that a PIV challenge has officially begun. The number of notices received is also telling. If a brand discloses that it has received PIV notices from multiple, established generic players like Teva, Viatris, and Sandoz , it signals a broad consensus among competitors that the drug’s patents are vulnerable, increasing the probability of a successful challenge and a highly competitive market once the first generic launches.

The 30-Month Stay: A Double-Edged Sword

Once the brand company and patent owner receive the PIV notice letter, they face a critical decision. The Hatch-Waxman Act gives them a 45-day window to file a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant . If they file suit within this window, a powerful and pivotal mechanism is triggered: an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic’s ANDA .

This 30-month stay is one of the most misunderstood elements of the Hatch-Waxman Act. On the surface, it appears to be a purely defensive tool for the brand, giving it two and a half years of continued monopoly protection while the patent case is litigated . And it certainly serves that purpose. However, for the predictive analyst, the stay’s true value is that it creates a predictable timeline for both sides.

Historically, the 30-month period was not an arbitrary number. It was chosen because it approximated the average time it took for the FDA to review an ANDA and for the district and appellate courts to resolve the ensuing patent litigation . This means the stay imposes a structured, if not entirely rigid, timeframe on the entire conflict. The FDA is barred from giving final approval to the ANDA until the earliest of three events: (1) the court rules in favor of the generic company, (2) the patent expires, or (3) the 30-month period runs out .

This creates a “quiet period” that is, paradoxically, teeming with predictive activity. While the generic’s application is formally stayed at the FDA, the company is anything but idle. This 30-month window is precisely when the generic manufacturer is making its most critical investments in preparation for launch. A company will not spend millions of dollars on scaling up API manufacturing, validating production lines, and building out its commercial infrastructure unless it is confident of a launch at the end of that period .

Therefore, any signals of such activity become intensely meaningful when viewed through the lens of the 30-month stay. An intelligence report that a specific API supplier in India has received a large order for atorvastatin calcium is interesting. An intelligence report that the order came from a generic company two years into a 30-month stay related to its challenge of Pfizer’s Lipitor patents is a powerful, corroborating signal of an impending launch. This transforms the stay from a simple regulatory delay into a defined, 30-month timeframe for focused, high-value intelligence gathering. For the generic company, the stay is not a passive waiting game; it is a predictable and critical window for strategic preparation, allowing it to finalize commercial plans and ensure supply chain readiness for a rapid market entry the moment the stay is lifted or expires.

Section 3: The Treasure Map – Leveraging the FDA’s Orange Book for Strategic Intelligence

Every quest needs a map, and for those hunting for future generic entrants, the map is bound in an orange cover. The FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations—the Orange Book—is far more than a simple regulatory list . It is a dynamic, data-rich resource that, when analyzed with a strategic eye, reveals the patent fortifications around every approved drug in the United States. Learning to read this map—to see the patterns, identify the weaknesses, and understand the strategic options it presents—is an essential skill for any pharmaceutical analyst .

Reading Between the Lines: Beyond Patent Numbers and Dates

At its most basic level, the Orange Book allows a user to search for a drug by its brand name (proprietary name) or active ingredient and retrieve a list of all associated patents and regulatory exclusivities, along with their expiration dates . This is the foundational data. An analyst can quickly see that the main patent for Drug X expires on June 15, 2028. But this is just scratching the surface. The real intelligence comes from analyzing the types and patterns of the patents listed.

Not all patents are created equal. In the pharmaceutical world, there is a clear hierarchy of strength and defensibility, and understanding this hierarchy is crucial for assessing a drug’s vulnerability to a generic challenge.

- Composition of Matter (or Compound) Patents: These are the crown jewels. They cover the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the core molecule . These patents are typically the first to be filed and are the most difficult to invalidate or design around. A drug protected by a strong, unexpired composition of matter patent is a formidable fortress.

- Formulation Patents: These patents do not cover the drug molecule itself, but rather the specific formulation or composition of the final drug product . This could include the specific mix of inactive ingredients (excipients), a particular extended-release mechanism, or a specific crystalline form (polymorph) of the API. These are strong patents but are more susceptible to being “designed around” by a generic company that develops a different formulation that achieves the same bioequivalence.

- Method of Use Patents: These patents cover a specific, approved use or indication for a drug . For example, a company might have a patent on using Drug Y to treat hypertension. These are generally considered the most vulnerable type of patent because they can often be circumvented entirely through a “skinny label” strategy, which we will discuss next.

An expert analyst doesn’t just see a list of patent numbers; they see a story. Is the drug protected by a single, aging composition of matter patent that expires in 18 months? If so, it is a prime target for multiple generic challengers who will likely launch on the day of expiry. Conversely, is the drug surrounded by what is known as a “patent thicket”—a dense, overlapping web of dozens of newer formulation, polymorph, and method of use patents that expire many years after the core compound patent ? This was the strategy famously employed by AbbVie for Humira and Celgene for Revlimid . A patent thicket signals a much more difficult and protracted battle for generics. It tells the analyst that a challenger’s strategy is less likely to be a straightforward court victory and more likely to be a long, costly litigation campaign designed to force a settlement. The pattern of patents in the Orange Book is a direct reflection of the brand’s defensive strategy and a powerful predictor of the type of generic challenge to expect.

The “Skinny Label” Gambit: Carving Out a Market

One of the most elegant and important strategies available to generic manufacturers is the “skinny label” launch. This maneuver allows a generic to enter the market even when a valid method of use patent is still in force. Instead of filing a PIV certification challenging that use patent, the generic applicant can submit a “Section viii statement” . This statement essentially tells the FDA, “We acknowledge that Patent #1234567 for the treatment of Condition A is still in force, and we are not seeking approval to market our drug for Condition A. We are only seeking approval for the drug’s other, non-patented indications.”

The FDA can then approve the generic drug with a “carved-out” or “skinny” label that omits the patented indication. This allows the generic to launch and compete for the portion of the market that uses the drug for its off-patent indications, without infringing the method of use patent. This is not a niche strategy; it is a mainstream pathway to market. A 2024 study found that between 2021 and 2023, of the 21 first generic entrants susceptible to skinny labeling, 9 of them (43%) used this pathway to secure an early launch .

This creates a powerful predictive filter for an analyst. When evaluating a target brand drug, the critical question becomes: “Is the commercial value of this drug tied to a single, patent-protected indication, or is it spread across multiple uses?”

Imagine a blockbuster drug with $2 billion in annual sales. The Orange Book shows its composition of matter patent has expired, but a method of use patent for its primary indication, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), doesn’t expire until 2035. If 95% of that drug’s sales are for RA, a skinny label launch for its other minor, off-patent indications is not commercially viable. The probability of an early generic launch is low.

Now, consider a different scenario. The same drug has a use patent for RA expiring in 2035, but 40% of its sales ($800 million) come from treating psoriasis, an indication for which there is no patent protection. Suddenly, the skinny label strategy becomes intensely attractive. An $800 million market is more than enough to entice multiple generic competitors.

By overlaying commercial data (prescription data, sales breakdowns by indication, brand marketing focus) onto the patent data in the Orange Book, an analyst can calculate the potential market size for a skinny-label generic. If that market is substantial, the probability of a Section viii filing and an early, carved-out launch increases dramatically. This turns a simple patent review into a sophisticated commercial forecast, allowing you to predict not just if a generic will launch, but how and for which segment of the market.

Section 4: Following the Paper Trail – Using Litigation Data to Predict Launch Timelines

When a generic company throws down the gauntlet with a Paragraph IV certification and the brand company responds with a lawsuit, the dispute moves from the regulatory realm of the FDA to the legal arena of the U.S. federal courts. This transition is a gift to the competitive intelligence analyst. The American legal system, for all its complexity, is remarkably public. The entire lifecycle of a patent infringement case is documented and tracked in public records, creating a rich, detailed paper trail. Following this trail provides a series of inflection points that can be used to dynamically update and refine predictions about a generic’s launch date .

From Filing to Finish: Key Milestones in Hatch-Waxman Litigation

A patent lawsuit is not a single, monolithic event that resolves overnight. It is a multi-year process with a series of distinct phases and milestones. An astute analyst doesn’t just wait for the final verdict; they monitor the case’s progress, understanding that each step can shift the probabilities of the outcome. This data is accessible through the federal court system’s Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) service, or more conveniently, through specialized commercial intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch that aggregate and analyze this litigation data .

Here are the key milestones to track in a typical Hatch-Waxman case and what they signal:

- Complaint Filing: This is the brand’s official response to the PIV notice. Its filing within the 45-day window confirms that the 30-month stay of approval has been triggered. The complaint itself will identify which patents the brand is asserting against the generic.

- Claim Construction (The Markman Hearing): This is arguably the most critical non-dispositive event in a patent case. Before a judge or jury can decide if a patent is infringed, the court must first legally define the scope and meaning of the patent’s claims. This process, known as claim construction, culminates in a Markman hearing, after which the judge issues a ruling interpreting the key terms . The outcome of the Markman hearing can decide the entire case. If the judge adopts a narrow interpretation of the patent’s claims, it may become clear that the generic’s product does not fall within that narrow scope, making a finding of non-infringement highly likely. Conversely, a broad interpretation favors the brand. A Markman ruling that is favorable to the generic company dramatically increases its odds of success and is a strong signal of a potential early launch.

- Summary Judgment Motions: After discovery, either side may file a motion for summary judgment, arguing that the facts are so overwhelmingly in their favor that there is no need for a full trial. The court’s decision to grant or deny these motions provides a strong indication of the judge’s view on the merits of the case and the relative strength of each party’s arguments.

- District Court Decision: This is the outcome of the trial itself, where the court rules on whether the patent is valid and/or infringed. This is a major trigger event. If the generic company wins, the 30-month stay is lifted, and the FDA can approve the ANDA (assuming all other regulatory requirements are met) . However, this is rarely the final word, as the losing party will almost certainly appeal.

- Federal Circuit Appeal: All patent appeals in the U.S. are heard by a single specialized court, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Its decision is typically the final, binding resolution of the patent dispute. The historical average time from the initial lawsuit filing to a Federal Circuit decision has been around 37 months, often extending just beyond the 30-month stay period .

By tracking these milestones, an analyst can move beyond a simple binary “win/loss” prediction. The process becomes a dynamic, probabilistic exercise. A model might start with a 50% chance of a generic win. After a favorable Markman ruling for the generic, that probability might be updated to 75%. This approach, which continuously incorporates new information from the legal battlefield, is the hallmark of expert analysis and provides a much more nuanced and accurate forecast of the ultimate outcome and timing.

The Rise of the PTAB: Inter Partes Review (IPR) as a Parallel Battlefield

The landscape of patent litigation was dramatically altered in 2011 with the passage of the America Invents Act, which created a new administrative venue for challenging patent validity: the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The primary mechanism for these challenges is the Inter Partes Review, or IPR.

An IPR allows anyone to petition the PTAB to review the validity of an issued patent based on arguments that it is not novel or is obvious in light of prior art (patents and printed publications). For generic companies, the IPR process offers several distinct advantages over traditional district court litigation. It is generally much faster, with a final decision typically rendered within 18 months of the petition filing. It is also significantly less expensive than a full-blown federal court case.

Most importantly, the PTAB has historically been a favorable venue for challengers. While the standards have evolved, the PTAB has shown a high rate of invalidating challenged patent claims, making the filing of an IPR a potent weapon in the generic arsenal.

Crucially, a generic company can pursue an IPR challenge in parallel with the ongoing district court litigation. This creates a two-front war for the brand-name patent holder. The filing of an IPR is, in itself, a strong signal of the generic’s confidence and aggressive posture. Because the PTAB uses a different, and some argue more challenger-friendly, standard for interpreting patent claims than most district courts, it can serve as a powerful early indicator of a patent’s underlying weakness.

An analyst who only tracks the district court case is missing half the story. The PTAB proceeding can move much more quickly. If the PTAB agrees to institute an IPR (a decision made within 6 months of the petition) and ultimately invalidates the patent, that decision can render the entire, slower-moving district court case moot. This means a PTAB decision can accelerate a generic launch timeline by a year or more compared to the expected resolution of the court case. Therefore, diligent monitoring of PTAB filings and decisions is not just an adjunct to tracking court litigation; it is a critical, and sometimes leading, source of predictive intelligence.

Section 5: The Art of the Deal – How Settlement Agreements Reveal Future Launch Dates

While the drama of courtroom battles and patent invalidations captures headlines, the reality of Hatch-Waxman litigation is that the vast majority of cases do not end with a judge’s verdict. They end with a handshake. It is estimated that over 75% of Paragraph IV challenges are ultimately resolved through a settlement agreement between the brand and generic manufacturers . For the predictive analyst, these settlements are not a sign that the trail has gone cold; they are a goldmine of definitive information. An announced settlement often transforms a probabilistic forecast based on litigation odds into a deterministic one based on a contractual launch date.

When Litigation Ends in a Handshake: Decoding Settlement Terms

Why do so many cases settle? Because high-stakes patent litigation is incredibly risky and expensive for both sides . The brand faces the catastrophic risk of having its patent invalidated, opening the floodgates to immediate and widespread generic competition. The generic faces the risk of losing the case and being blocked from the market until patent expiry, having spent millions on legal fees with nothing to show for it.

A settlement offers certainty. The brand gets to preserve its monopoly for a defined, and often extended, period, while the generic gets a guaranteed, risk-free market entry on a specific future date . This mutual desire to de-risk the situation is a powerful driver of negotiation.

The most common form of settlement involves the generic company agreeing to drop its patent challenge in exchange for a license from the brand to launch its generic product at an agreed-upon future date . When such a settlement is reached, the companies will issue a press release or disclose the agreement in an SEC filing. These announcements are one of the most direct and reliable pre-approval signals available. They effectively replace the uncertain timeline of litigation with a fixed date on the calendar. An analyst’s job then shifts from predicting the outcome of a court case to simply noting the date and updating their market models accordingly. Setting up automated alerts to monitor company press releases and SEC filings for keywords like “settlement,” “litigation,” “license agreement,” and the drug’s name is a highly effective and direct method for capturing this definitive launch information.

For years, a common but controversial feature of these deals was the “reverse payment” or “pay-for-delay” settlement. In these arrangements, the brand-name manufacturer would not only grant a future launch license but would also pay the generic company a substantial sum of money, ostensibly to avoid the costs of continued litigation . The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and other antitrust enforcers have long argued that these payments are anti-competitive, essentially a brand paying a generic to stay off the market longer than it otherwise might have . The Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in FTC v. Actavis, Inc. held that such agreements could, in fact, violate antitrust laws and are subject to legal scrutiny . This increased legal risk for brands has led to an evolution in settlement strategies, pushing them toward more creative structures to achieve the same goal of a managed, delayed generic entry.

The Revlimid Revolution: Understanding Volume-Limited Launches

The poster child for the modern, post-Actavis settlement strategy is Celgene’s (now Bristol Myers Squibb’s) defense of its blockbuster cancer drug, Revlimid (lenalidomide). Faced with numerous generic challenges and a formidable patent thicket of its own creation (over 100 granted patents), Celgene pioneered the widespread use of a new type of settlement: the “volume-limited license” .

Instead of simply agreeing on a future launch date, Celgene settled with multiple generic filers, including Natco Pharma, Cipla, and others, on a multi-tiered arrangement . The agreements allowed the generics to launch on a specific date (the first being in March 2022), but they severely restricted the quantity of generic Revlimid they were allowed to sell . For example, the initial volume cap for some entrants was a “mid-single-digit percentage” of the total Revlimid market volume in the first year . This volume cap would then gradually increase each year until a final, later date (January 31, 2026), at which point all volume restrictions would be lifted, and the generics could sell an unlimited quantity .

This strategy was a masterstroke of brand defense. It provided a legal settlement that was less likely to be viewed as a simple “pay-for-delay” scheme, yet it effectively accomplished the same goal: protecting the vast majority of Revlimid’s revenue stream for several years beyond the initial generic entry. It transformed the traditional “patent cliff”—a sharp, sudden drop in revenue—into a gentle, predictable, multi-year slope.

The Revlimid case represents a major evolution in competitive dynamics and complicates predictive analysis. An analyst can no longer just predict the date of first generic entry; they must now predict the impact of that entry. A launch that is contractually limited to 7% of the market volume will have a vastly different effect on the brand’s revenue, the overall market price, and the competitive landscape than an unrestricted launch . This requires a more sophisticated forecasting model that accounts not just for the “when” but also the “how much.”

When a settlement is announced today, the savvy analyst must look beyond the headline launch date and scrutinize the details for any mention of volume limitations. The key data points are now:

- The initial licensed launch date.

- The initial volume cap (if any).

- The schedule for how that volume cap increases over time.

- The final date for unrestricted entry.

Each of these data points, typically found in the company’s press release or SEC filing detailing the settlement, must be factored into revenue and pricing forecasts to create an accurate picture of the market’s future. The Revlimid playbook has become the new standard for high-value drugs, and understanding its mechanics is essential for modern predictive analysis.

Section 6: Beyond the Courtroom – Integrating Broader Competitive Intelligence

The regulatory and legal signals generated by the Hatch-Waxman process form the backbone of any generic launch prediction. They are the “hard” data points—the filings, the court dates, the patent numbers. However, a truly comprehensive analysis goes beyond these formal channels to incorporate a wider range of “soft” signals from the competitive landscape. By integrating intelligence from corporate communications, investor relations, and real-world manufacturing and supply chain activities, an analyst can build a richer, more robust, and more confident forecast. The goal is triangulation: using data from one domain to confirm or challenge a signal from another.

Listening to the Market: Analyzing Investor Relations and Corporate Communications

Publicly traded pharmaceutical companies are in constant communication with the financial community. Their quarterly earnings calls, investor conference presentations, and mandatory SEC filings are designed to convey their strategy, performance, and outlook . For the competitive intelligence analyst, these communications are a rich source of clues, provided you know how to listen .

- Earnings Calls and Investor Presentations: The scripted remarks and, more importantly, the unscripted Q&A sessions on these calls can be revealing. A brand company’s CEO might be asked directly about their defense strategy for a drug facing patent expiry. Their tone, confidence, and the level of detail they provide can be telling. On the generic side, a CEO might highlight progress in their pipeline, mentioning “manufacturing readiness for a key Q4 launch” or “advancing our complex respiratory generic”. While they won’t name the product, an analyst who knows that company is in the middle of a 30-month stay for a generic version of a major respiratory drug can connect the dots.

- SEC Filings (10-K, 10-Q): Beyond the initial disclosure of a PIV notice, these detailed reports provide ongoing updates. The “Legal Proceedings” section of a 10-K will often summarize the status of all material litigation, including Hatch-Waxman cases. A change in the description of a case from one quarter to the next can signal a shift in the company’s assessment of its chances.

- Company Press Releases: These are the most direct source for major announcements. Generic companies will issue press releases to announce that they have filed a significant ANDA. Both brand and generic companies will issue releases to announce the outcome of litigation or, most critically, the signing of a settlement agreement.

The key to leveraging this “soft” intelligence is to never view it in a vacuum. A standalone comment on an earnings call is just noise. But a comment about making “significant capital investments at our North Carolina facility” made by a generic CEO two years into a 30-month stay for a complex injectable drug becomes a powerful, corroborating signal when you know that the North Carolina facility is the company’s center of excellence for sterile injectable manufacturing. This synthesis—connecting the soft signals from corporate communications with the hard signals from regulatory and legal filings—is what elevates basic monitoring to the level of true intelligence. It moves an analyst from knowing a challenge exists to having high confidence that the company is on track and prepared to launch as soon as legally possible.

The Physical Trail: Supply Chain and Manufacturing Signals

Before a single pill can be sold, it must be manufactured. The journey from raw chemical inputs to a finished, packaged drug product leaves a physical trail that can be monitored for predictive signals. This is particularly true for the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), the core component of any drug.

A sudden, large order of a specific API by a known generic manufacturer from a major supplier is one of the strongest real-world indicators of an impending launch . This type of supply chain intelligence can be gathered through various means, including primary research and monitoring of import/export data. A generic company simply won’t commit to purchasing millions of dollars’ worth of a specific API unless they have a clear and confident path to using it in a commercial product in the near future.

Other manufacturing signals can be equally telling. A generic company might announce the acquisition of a new manufacturing plant or the expansion of an existing one. If that facility has specialized capabilities—for example, in producing sterile injectables, transdermal patches, or complex biologics—that happen to match the dosage form of a major brand-name drug nearing patent expiry, it’s a strong indicator of that company’s strategic intentions .

The value of these physical signals is amplified by the complexity of the drug product itself. For a simple, easy-to-manufacture oral solid tablet like Lipitor (atorvastatin), there are dozens of companies worldwide that can produce the API and the finished product . The barrier to entry is low. Therefore, a single manufacturing signal is less meaningful amidst all the noise.

However, for a complex product like Vivitrol (naltrexone for extended-release injectable suspension), which uses a sophisticated biodegradable polymer-microsphere technology, the manufacturing barriers are immense . Only a handful of companies in the world possess the technical expertise and specialized facilities to produce such a drug. For these complex products, manufacturing and supply chain signals are far more valuable and predictive. The signal-to-noise ratio is much higher. Identifying a generic company that has filed a PIV for a complex product is significant. Discovering that the same company has also recently validated a new production line for polymer microspheres is a powerful confirmation that they have likely overcome the primary technical hurdle and are serious contenders for market entry.

Section 7: The First-Mover’s Golden Ticket – The Economics of 180-Day Exclusivity

In the intense race to bring a generic drug to market, there is a prize so valuable that it shapes the strategies of every competitor: the 180-day marketing exclusivity period. This is the “brass ring” of the Hatch-Waxman Act, the single most powerful incentive designed to encourage generic companies to undertake the costly and risky endeavor of challenging brand-name patents . Understanding the mechanics of this exclusivity, its immense financial value, and the complex rules that govern who gets it and who can lose it, is fundamental to predicting not just the timing of the first generic launch, but the entire competitive structure of the market that follows.

The “Brass Ring”: Quantifying the Value of Being First

The law is straightforward: the “first applicant” to file a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification is eligible for a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity . During these six months, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug that also contain a PIV certification .

The commercial implication of this is profound. It effectively creates a temporary duopoly in the market, consisting only of the brand-name drug and the single “first-filer” generic . This limited competition allows the first generic entrant to price its product at only a moderate discount—typically 15-25% below the brand’s price—while still capturing a massive portion of the market share from price-sensitive patients and payers . This six-month period is often the most profitable phase of a generic drug’s entire lifecycle, frequently accounting for the majority of the manufacturer’s return on its development and litigation investment.

The value of this exclusivity becomes starkly clear when you examine what happens when it ends. Once the 180 days are up, the FDA can approve all other pending ANDAs, opening the floodgates to widespread competition. The market rapidly shifts from a duopoly to a multi-player, commodity-like environment, and the price plummets accordingly.

Table 2: The Financial Impact of Generic Entry on Price and Market Share

| Number of Generic Competitors | Average Price Reduction vs. Brand | Typical Brand Market Share Loss (within 1 year) |

| 1 (First Entrant/Exclusivity Period) | 39% | 50-60% |

| 2 | 54% | >80% |

| 3-5 | 70-80% | >90% |

| 6+ | 95% | >95% |

Note: Price reduction and market share figures are synthesized averages from multiple sources and can vary based on the specific drug and market dynamics.

As the table illustrates, the difference between being the first generic and the sixth is the difference between a strategic, high-margin launch and a low-margin commodity business. The first generic to market can expect to reduce the brand’s price by about 39%, but by the time six competitors are present, the price has fallen by 95% . This is why companies will devote substantial resources to preparing their ANDA filings and racing to be the first to submit them to the FDA . The 180-day exclusivity isn’t just an incentive; it’s the economic engine that drives the entire patent challenge ecosystem.

The Race to be First and the Risk of Forfeiture

Securing the coveted “first applicant” status is a primary strategic objective for any generic company targeting a major drug. This status is granted to the first company (or companies, in the case of a same-day filing) that submits an ANDA that the FDA deems “substantially complete” and which contains a PIV certification . This creates a frantic, behind-the-scenes race to prepare and file these complex applications on the earliest possible day.

However, winning the race to be first is not the end of the story. A first applicant can lose—or “forfeit”—its 180-day exclusivity if it fails to meet certain obligations . These complex forfeiture provisions were significantly amended by the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and are designed to prevent a first applicant from “parking” its exclusivity and indefinitely blocking other generics from entering the market.

Key events that can trigger forfeiture of the 180-day exclusivity include:

- Failure to Market: This is the most significant provision. A first applicant can lose its exclusivity if it fails to market its generic drug within a specific timeframe (typically 75 days) after its ANDA is approved or after a favorable court decision that clears the way for launch .

- Withdrawal of Application: If the first applicant withdraws its entire ANDA, it forfeits its exclusivity .

- Amendment of Certification: If the first applicant amends its PIV certification to a Paragraph III certification (for example, after losing a patent case and deciding to wait for patent expiry), it forfeits its exclusivity .

- Failure to Obtain Tentative Approval: If the FDA does not grant at least a “tentative approval” to the first applicant’s ANDA within 30 months of its submission, the exclusivity can be forfeited . A tentative approval is issued when an ANDA is ready for approval from a scientific and regulatory perspective but is blocked from final approval by unexpired patents or exclusivities .

These forfeiture rules create a fascinating and dynamic interplay between the first, second, and subsequent generic filers. A second-filer is not merely a passive bystander waiting in line. They can take active steps to force the issue. Specifically, under the “failure to market” provision, the 75-day clock for the first applicant to launch can be triggered by a court decision or by a later-filing generic applicant receiving tentative approval from the FDA .

This gives the second-filer significant agency. By diligently pursuing its own ANDA and getting it to the point of being ready for approval, the second-filer can effectively start the clock on the first-filer’s obligation to launch. If the first-filer then fails to launch within the prescribed time, it forfeits its exclusivity, and the FDA can then grant final approval to the second-filer and all other ready applicants.

For the predictive analyst, this means it is not enough to track only the first-filer. You must also monitor the regulatory progress of the second and third challengers for the same drug. The issuance of a tentative approval letter by the FDA to a subsequent filer is a major predictive signal. It indicates that the exclusivity landscape is about to be forcibly changed and that a more competitive, multi-player market may be on the horizon much sooner than expected.

Section 8: Case Studies in Foresight – Learning from Lipitor, Revlimid, and Humira

Theory and frameworks are essential, but the real lessons are learned by examining how these dynamics play out in the real world. By analyzing the history of some of the biggest patent battles in pharmaceutical history, we can see the principles of predictive analysis in action. The cases of Lipitor, Revlimid, and Humira serve as perfect archetypes for the classic, modern, and biologic-frontier playbooks for generic and biosimilar competition.

The Classic Battle: Lipitor (Atorvastatin)

Pfizer’s Lipitor was, for a time, the best-selling prescription drug in the world, a colossus of the pharmaceutical industry . Its journey to generic competition represents the “classic” Hatch-Waxman saga, a story of multiple challengers, protracted litigation, and strategic brand defense that ultimately ended in a carefully negotiated market entry.

The pre-approval signals began years before the first generic launch. As Lipitor’s core patents began to approach their expiration, multiple generic companies, including Ranbaxy Laboratories and Teva Pharmaceuticals, filed ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications. This triggered the expected wave of patent infringement lawsuits from Pfizer and the commencement of the 30-month stays .

Pfizer’s defense strategy was multifaceted. Legally, it engaged in vigorous litigation to defend its patent portfolio . Commercially, it launched a massive direct-to-consumer marketing campaign, famously featuring Dr. Robert Jarvik, to build immense brand loyalty and convince patients and physicians that there was “no substitute” for Lipitor, subtly questioning the equivalence of any future generic . This was a classic brand-defense tactic aimed at creating a “sticky” patient base that would be resistant to automatic generic substitution.

The litigation was complex, spanning multiple patents and years. The key turning point, as is often the case, was not a final court verdict but a series of settlement agreements. Pfizer settled with Ranbaxy, the first-filer, granting it a license to launch its generic version on November 30, 2011. This settlement provided the first definitive, public signal of the exact date generic competition would begin. Pfizer also struck a deal with Watson Pharmaceuticals (now part of Teva) to launch an authorized generic (AG) on the same day . An AG is the brand-name company’s own generic version, which allows the brand to participate in the generic market and capture a share of the revenue it would otherwise lose.

For an analyst tracking Lipitor, the signals were clear and followed the classic playbook:

- PIV Filings: Multiple generic players filed challenges, signaling strong interest and perceived patent vulnerability.

- Litigation: Pfizer initiated lawsuits, triggering the 30-month stays and a long period of legal maneuvering.

- Brand Defense: Pfizer employed aggressive marketing to fortify its brand equity ahead of the generic wave.

- Settlement: The settlement announcement with Ranbaxy provided the definitive launch date, replacing probabilistic forecasts with certainty.

- Authorized Generic: The deal with Watson signaled Pfizer’s intent to compete directly in the generic space, a factor that would need to be included in any forecast of the first-filer’s profitability.

The Modern Playbook: Revlimid (Lenalidomide)

If Lipitor was the classic battle, the case of Celgene/BMS’s Revlimid wrote the playbook for modern brand defense in the small-molecule space. It is the ultimate example of using a patent thicket and innovative settlement structures to manage the patent cliff and orchestrate a “soft” landing for a blockbuster drug.

Revlimid’s core active ingredient patent was set to expire in 2019 . However, Celgene had surrounded the drug with a massive patent thicket, filing over 200 patent applications and obtaining over 100 granted patents covering everything from methods of use to the drug’s specific crystalline form and even its mandatory safety and distribution program (REMS) . This created an almost insurmountable legal fortress. Challenging a single patent can cost a generic company over $1 million; challenging dozens was a non-starter .

Despite this, generic challengers like Natco Pharma filed ANDAs with PIV certifications, targeting the core patents . This initiated the expected litigation. But the endgame here was never likely to be a full court victory for the generics. The strategic goal was to litigate aggressively enough to force Celgene to the negotiating table.

And negotiate it did. Starting around 2020, Celgene/BMS announced a series of settlement agreements with its generic challengers, including Cipla, Dr. Reddy’s, and Natco . These settlements were masterpieces of modern brand defense. They did not involve direct “pay-for-delay” payments. Instead, they utilized the volume-limited license strategy.

The press releases were explicit and provided a clear roadmap for any analyst . They stated that the generics would be licensed to launch on a confidential date “some time after March 2022.” More importantly, they specified that for each year until January 31, 2026, the volume of generic lenalidomide sold by each company could not exceed “certain agreed-upon percentages” of the total market . Only after January 31, 2026, would they be licensed to sell an unlimited quantity.

The Revlimid case demonstrated a new set of signals for analysts to track:

- Patent Thicket Analysis: An early look at the Orange Book would reveal the dense patent estate, signaling that a settlement, rather than a court verdict, was the most likely outcome.

- Litigation as Leverage: The PIV filings and subsequent lawsuits were signals of the generics’ use of litigation as a tool to gain leverage for a settlement negotiation.

- Settlement Announcements: The press releases announcing the settlements were the key predictive documents.

- Volume-Limited Terms: The critical insight was to look beyond the initial launch date and identify the volume restrictions and the multi-year ramp-up schedule, which are essential for accurately forecasting the brand’s revenue erosion over time.

The Biologic Frontier: Humira (Adalimumab)

While biologics and their “biosimilar” competitors are governed by a different law—the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA)—the strategic principles of patent defense and competitive entry are identical to the Hatch-Waxman world, and the case of AbbVie’s Humira is the most instructive example to date. Humira’s defense strategy took the Revlimid playbook and scaled it to an unprecedented level.

Humira, the world’s best-selling drug for many years, was protected by a patent thicket even more formidable than Revlimid’s . AbbVie built a fortress of over 100 patents covering not just the molecule, but every conceivable aspect of its formulation, manufacturing, and use . As biosimilar developers like Amgen, Sandoz, and Boehringer Ingelheim began to secure FDA approval for their versions, AbbVie systematically sued each one for patent infringement .

The result was not a single, winner-take-all court case, but a wave of carefully orchestrated settlements. Starting with Amgen in 2017, AbbVie settled with virtually every major biosimilar player. Each settlement agreement contained a license for the biosimilar to launch in the United States, but not until 2023 . AbbVie effectively used its patent estate and the threat of endless, costly litigation to create a five-year delay between the first biosimilar approval (Amgen’s Amgevita in 2016) and the first launch.

Furthermore, the settlements created a staggered, predictable launch sequence for the entire market. Amgen was licensed to launch first in January 2023. Other companies were licensed to launch later in the year, often around July 2023 . AbbVie had single-handedly acted as the market’s air traffic controller, dictating the precise timing and sequence of its own competition years in advance.

For an analyst, the Humira case provided a masterclass in long-range forecasting:

- Early Signal of Strategy: The sheer size of Humira’s patent thicket was the first signal that AbbVie’s strategy would be one of litigation and managed settlement, not reliance on a single core patent.

- The First Settlement as the Template: The 2017 settlement with Amgen, which set the 2023 launch date, became the template for all subsequent deals. Once this first deal was announced, it was highly probable that other biosimilar entrants would be held to a similar timeline.

- A Cascade of Confirming Signals: Each subsequent settlement announcement with another biosimilar manufacturer was a confirming data point, reinforcing the 2023 launch timeline and adding new players to the predictable launch schedule.

- Long-Term Certainty: Years before the first biosimilar hit the U.S. market, analysts had a clear and highly reliable list of which competitors would be entering and on what schedule. This allowed for incredibly precise long-term forecasting of Humira’s revenue decline and the ramp-up of the U.S. biosimilar market.

Section 9: Building Your Predictive Arsenal – A Practical Toolkit and Workflow

We have explored the legal frameworks, regulatory processes, and strategic maneuvers that generate predictive signals for generic drug entry. Now, we must assemble these components into a cohesive, practical workflow. A successful predictive strategy is not about finding a single magic bullet; it is about the systematic collection and synthesis of disparate data points. It is about triangulation—the practice of confirming a signal from one domain with corroborating evidence from others to build a high-confidence forecast.

The Triangulation Method: Synthesizing Disparate Signals

The core of this workflow is moving from isolated data points to an integrated intelligence picture. A rumor of an API scale-up is just a rumor. A PIV filing is just a legal document. A CEO’s vague comment is just talk. But when all three point in the same direction, for the same drug, and on the same timeline, they become a powerful, actionable insight.

Here is a step-by-step process for implementing the triangulation method:

- Identify High-Value Targets: The process begins with portfolio analysis. Use commercial data on brand drug sales and FDA Orange Book data on patent status to create a prioritized list of targets. Focus on drugs with significant revenue and key patents (especially composition of matter patents) that are set to expire within the next 3-7 years. This is your watchlist.

- Monitor for the “Shot Across the Bow”: For each drug on your watchlist, the first critical event to monitor is the PIV filing. Set up automated alerts using SEC filing databases (EDGAR), news aggregators, or specialized services like DrugPatentWatch to immediately flag any disclosure by the brand company that it has received a PIV notice letter. Note the date and the identity of the challenger(s).

- Track the Legal and Regulatory Battlefronts: Once a challenge is confirmed, the dual-front tracking begins.

- District Court: Use PACER or an aggregated litigation database to track the case docket. Note the key milestones: complaint filing (confirming the 30-month stay), the Markman hearing and ruling, summary judgment motions, and the final district court decision.

- PTAB: Simultaneously, monitor the PTAB database for any IPR petitions filed against the drug’s patents. An IPR filing is a significant signal of aggression and confidence from the generic challenger.

- Listen to the Market’s “Soft Signals”: While tracking the legal process, tune into the corporate communications of both the brand and the generic challenger(s). Systematically review quarterly earnings call transcripts, investor conference presentations, and annual reports. Look for any language, however subtle, that relates to the challenged product, the company’s generic pipeline, manufacturing preparations, or legal expenses.

- Watch the Physical Trail: Activate supply chain and manufacturing intelligence gathering. This is especially critical for complex products (injectables, inhalers, biologics). Monitor for signals of API production scale-up, acquisition of specialized manufacturing equipment, or expansion of facilities with relevant capabilities by the generic challenger.

- Model and Update the Outcomes: Do not treat prediction as a one-time event. Build a simple, probability-weighted forecast model for each target. Start with a baseline probability of launch (e.g., based on historical success rates for PIV challenges). Then, continuously update the probabilities and timelines as new signals come in. A favorable Markman ruling for the generic might increase the probability of an early launch from 30% to 60%. A settlement announcement changes the probability to 100% and sets a firm date. This dynamic approach is what creates a truly valuable and timely forecast.

The Analyst’s Dashboard: Key Data Sources and Tools

An effective workflow requires the right tools. While much of this information is public, accessing it efficiently and synthesizing it requires a well-curated dashboard of resources.

Essential Public Sources:

- FDA Orange Book: The starting point for all patent and exclusivity analysis .

- PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records): The primary source for federal court documents, including patent litigation dockets .

- USPTO Databases: For detailed patent information and for tracking PTAB proceedings (IPRs).

- SEC EDGAR Database: The source for all public company filings (10-Ks, 10-Qs, 8-Ks), essential for finding disclosures of PIV notices and settlement terms.

- ClinicalTrials.gov: For monitoring clinical trial activity, which can sometimes provide clues about a company’s focus and development pipeline .

Commercial Competitive Intelligence Platforms:

While public sources are free, they are often disparate and difficult to search systematically. Commercial platforms are designed to aggregate, link, and analyze this data, providing a massive efficiency boost.

- DrugPatentWatch: This is a highly specialized platform designed for the exact workflow described in this report. It integrates patent, exclusivity, litigation, and regulatory data into a single, searchable database, providing alerts and analytics specifically tailored to predicting generic and biosimilar entry . It is an invaluable tool for any professional focused on this niche.

- Broader Platforms: Other platforms like Clarivate’s Cortellis and AlphaSense offer comprehensive competitive intelligence solutions that include much of this data, often integrated with news, conference presentations, and other market intelligence, allowing for the synthesis of hard and soft signals in one place.

To bring this all together, here is a practical checklist that summarizes the key signals an analyst should be tracking.

Table 3: The Generic Entry Predictive Signals Checklist

| Predictive Signal | Primary Data Source(s) | Predictive Value |

| Orange Book Patent Thicket | FDA Orange Book | Medium: Signals likely brand defense strategy (litigate to settle). |

| PIV Notice Received by Brand | Brand Co. SEC Filings, Press Releases | High: The official start of the conflict. |

| Lawsuit Filed by Brand | PACER, Litigation Databases | High: Confirms the 30-month stay has begun. |

| IPR Petition Filed at PTAB | USPTO PTAB Database | High: Signals aggressive generic strategy and a parallel, faster path to invalidation. |

| Favorable Markman Ruling | Court Dockets (PACER) | Medium-High: Significantly shifts the odds of the case in favor of one party. |

| Settlement Agreement Announced | Company Press Releases, SEC Filings | Definitive: Replaces a probabilistic forecast with a certain launch date/structure. |

| Tentative Approval for 2nd Filer | FDA Approval Database | High: Signals that the first-filer’s exclusivity may be at risk of forfeiture. |

| API Production Scale-Up | Supply Chain Intelligence, Primary Research | Medium-High: Strong real-world signal of launch preparation, especially for complex drugs. |

| CEO Mentions “Launch Readiness” | Earnings Call Transcripts, Investor Presentations | Low-Medium: A soft signal that requires corroboration but can confirm timing. |

Section 10: Conclusion and Forward-Looking Analysis

The ability to accurately anticipate the entry of generic competition is not a mystical art but a rigorous discipline. It is the practice of systematically decoding a series of deliberate, legally mandated signals that are publicly available to anyone with the diligence to look and the expertise to interpret them. The Hatch-Waxman Act, in its attempt to balance innovation and affordability, created a structured arena of conflict whose every move can be tracked, analyzed, and transformed into a powerful competitive advantage. From the initial shot across the bow of a Paragraph IV certification to the final, definitive announcement of a settlement agreement, a clear and predictable trail exists.

By mastering this playbook—by understanding the language of patent certifications, the strategic value of the Orange Book, the key milestones of litigation, and the art of synthesizing hard data with soft intelligence—business professionals can move from a reactive to a proactive posture. They can foresee market shifts, mitigate the financial shock of a patent cliff, identify lucrative first-to-file opportunities, and make smarter, more confident strategic decisions. The future of a multi-billion-dollar market is not written in the stars, but in the dockets, databases, and disclosures of the system itself.

Key Takeaways: Your Blueprint for Competitive Advantage

- The System is Designed to Signal: The Hatch-Waxman Act is a structured conflict resolution system. The signals we track (PIV filings, lawsuits, etc.) are the intended output of this system, designed to force patent disputes into the open before a generic launch.

- The PIV is Ground Zero: A Paragraph IV certification and the subsequent notice letter are the most critical early signals. Their disclosure in a brand’s SEC filings often provides the first public confirmation that a battle has begun.

- The 30-Month Stay is a Strategic Window: This is not just a delay. It’s a predictable 2.5-year period for focused intelligence gathering. Monitor for manufacturing and commercial readiness activities by the generic challenger during this specific timeframe.

- Analyze the Orange Book Strategically: Go beyond dates. Analyze the type and pattern of patents. A single, old compound patent signals a different fight than a dense “patent thicket.” Use commercial data to assess the viability of a “skinny label” launch to circumvent method-of-use patents.

- Litigation is a Series of Inflection Points: Don’t just wait for the final verdict. Track key milestones like the Markman hearing and IPR proceedings at the PTAB. Each event shifts the probabilities and allows for a more dynamic and accurate forecast.

- Settlements Provide Certainty: Most cases settle. The settlement announcement is often the most definitive signal, providing a contractual launch date. Scrutinize the terms for modern structures like the volume-limited licenses pioneered in the Revlimid case.

- Triangulate Your Intelligence: The most robust predictions come from confirming signals across different domains. Connect a legal signal (a lawsuit) with a commercial signal (an earnings call comment) and a physical signal (API manufacturing) to build a high-confidence picture.

- Track the “Second Filer”: The race for 180-day exclusivity is dynamic. The progress of the second generic filer can force the first-filer to launch or risk forfeiting their golden ticket. Monitor for tentative approvals issued to any challenger.

The Evolving Battlefield: Future Trends in Generic Competition

The landscape of pharmaceutical competition is in constant flux. As we look forward, several trends will continue to shape the strategies of both brand and generic players, requiring analysts to adapt their predictive models.

- Increasing Complexity: The era of easily replicated small-molecule tablets is waning. The future is in more complex products: biologics and their biosimilar competitors, long-acting injectables, transdermal patches, and drug-device combinations. For these products, manufacturing and technical barriers to entry are as significant as patent barriers. Predictive analysis will need to weigh technical feasibility and supply chain intelligence even more heavily.

- The Impact of New Legislation: Laws like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are set to reshape market incentives . The IRA’s drug price negotiation provisions could lower the price of certain brand-name drugs in Medicare, which may, in turn, reduce the potential profit margin and incentive for a generic company to challenge its patents. The long-term effects are still uncertain, but they will undoubtedly alter the calculus for generic entry on some products.

- The Continued Evolution of Litigation and Settlement: The “patent thicket” and “volume-limited settlement” strategies, perfected in the Revlimid and Humira cases, are now standard practice for high-value drugs. We can expect to see even more creative legal and commercial strategies designed to manage patent cliffs and orchestrate a “soft” entry for competitors. Antitrust scrutiny from the FTC will continue to shape what is permissible, forcing companies to innovate in their settlement structures.

The game is always changing, but the fundamental principles of signal detection remain the same. By staying attuned to these evolving trends and continuously refining their analytical toolkit, business professionals can maintain their edge and successfully navigate the ever-shifting currents of pharmaceutical competition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How do “at-risk” launches factor into my predictions, and what do they signal about a generic company’s confidence?

An “at-risk” launch is when a generic company decides to market its product before the final resolution of patent litigation. This is a high-stakes gamble. If the generic company ultimately loses the patent case, it can be liable for massive damages, potentially including up to triple the brand’s lost profits for willful infringement . Therefore, an at-risk launch is one of the most powerful signals of a generic company’s extreme confidence in its legal position. It tells you they believe their non-infringement or invalidity arguments are so strong that the risk of catastrophic damages is outweighed by the financial benefit of early market entry. When predicting launch timing, an at-risk launch should be considered a low-probability but high-impact event. Factors that increase its likelihood include a very strong district court win for the generic, a history of the challenging company making such launches, and patents that have been successfully invalidated in other jurisdictions .

2. My company is a brand manufacturer. How can I use this playbook defensively to better anticipate and counter generic challenges?

This playbook is just as valuable for brand defense as it is for generic prediction. By understanding the signals a generic challenger looks for, a brand company can proactively fortify its defenses.

- Strategic Patenting: Don’t just focus on the core compound. Build a strategic “patent thicket” with meaningful formulation and method-of-use patents to increase the cost and complexity of a challenge.

- Monitor the Landscape: Use the same tools to monitor potential challengers. Knowing which companies are building capabilities in your drug’s specific technology or filing ANDAs for similar products can provide an early warning.

- War-Game the “Skinny Label”: Analyze your own product’s sales by indication. If a significant portion of revenue comes from an unpatented use, anticipate a skinny label challenge and develop a commercial strategy to defend that segment of the market.

- Prepare for Litigation: When you receive a PIV notice, use the 30-month stay not just to litigate, but to execute a lifecycle management plan. This could include developing a next-generation product, preparing an authorized generic launch, or securing favorable formulary contracts with payers to make generic substitution more difficult.

3. With the rise of patent thickets, is the Paragraph IV challenge still a viable path for generics, or is settlement the only realistic outcome for major drugs?

The PIV challenge remains a viable and essential path, but its strategic purpose has evolved for major, heavily-patented drugs. While a decisive court victory that invalidates all patents is still possible, it has become a less common outcome for drugs protected by a dense thicket . Today, for these blockbuster products, the PIV challenge and the ensuing litigation often serve as the primary leverage to bring the brand company to the settlement table. The generic’s goal is not necessarily to burn the entire patent fortress to the ground, but to demonstrate a credible enough threat to a few key patents that the brand decides it is more prudent to negotiate a managed entry (via a licensed settlement) than to risk even a small chance of a catastrophic loss in court. So, the PIV challenge is still the key that unlocks the door, but the door it now opens more often leads to a negotiation room than a courtroom verdict.

4. How reliable is Orange Book data for predicting generic entry timing, and what are its primary limitations?

Orange Book data is highly reliable for what it contains, but its limitations are critical to understand . It is the definitive source for which patents a brand asserts cover its product and when those patents and regulatory exclusivities expire. Its primary limitation is that it is not a judgment on patent validity or infringement. The FDA does not vet the patents; it simply lists what the NDA holder submits . A brand can list a weak or irrelevant patent, and a generic must still certify against it. Therefore, Orange Book data alone cannot predict the outcome of litigation. Its true power comes when it is used as a foundational layer and combined with other intelligence sources. By integrating Orange Book data with litigation records, PTAB decisions, and settlement announcements, you can create a highly reliable forecast. On its own, it provides the “what” (which patents are at issue); it does not provide the “what happens next.”

5. How does the entry of an “authorized generic” (AG) by the brand company affect the 180-day exclusivity for the first-filer and my market forecasts?

The launch of an authorized generic is a major disruptive event for the first-filing generic and must be factored into any forecast. An AG is the brand’s own product, marketed as a generic, often through a subsidiary or partner . Because it is not approved under an ANDA, it is not blocked by the first-filer’s 180-day exclusivity. A brand can launch its AG on the same day the first-filer launches. This immediately shatters the profitable duopoly that the 180-day exclusivity is meant to create. Instead of a brand vs. one generic, the market becomes a brand vs. two generics. This has a dramatic impact on the first-filer’s profitability, with studies showing that an AG launch can reduce the first-filer’s revenue by 40-52% during the exclusivity period . When forecasting, you must always consider the possibility of an AG launch. Signals to watch for include a history of the brand company using AGs for other products or specific language in settlement agreements that carves out the right for the brand to launch an AG.

References

- DLA Piper. (2020). Hatch-Waxman litigation 101.

- Westlaw. (n.d.). Hatch-Waxman Act.

- Janicke, P. (n.d.). Hatch-Waxman ANDA procedure summary. University of Houston Law Center.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA).

- Finnegan. (2017). FDA Amends Regulations for 505(b)(2) Applications and ANDAs—Part II.

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025). What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV Challenges.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity.

- Association for Accessible Medicines. (n.d.). The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive Accelerates Patient Access to First Generics.

- AlphaSense. (n.d.). How to track FDA drug approvals using Smart Search technology.

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025). The Role of Litigation Data in Predicting Generic Drug Launches.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2025). Generic Drug Competition and Drug Prices.

- Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. (2025). Skinny Labeling and Generic Drug Competition.

- Patent PC. (n.d.). How Patent Litigation Influences Drug Approvals and Market Entry.

- Number Analytics. (n.d.). Navigating Patent Law for Generic Drugs.

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025). Generic Drug Entry Timeline: Predicting Market Dynamics After Patent Loss.

- Federal Trade Commission. (2002). Generic Drug Entry Prior to Patent Expiration: An FTC Study.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2021). Patents and Exclusivities for Generic Drug Products.

- Congressional Research Service. (2024). The FDA’s “Orange Book”: A Legal Overview.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Electronic Orange Book.

- Lifescience Dynamics. (n.d.). What is competitive intelligence in the pharma industry?

- Sedulo Group. (n.d.). Pharma Competitive Intelligence Companies.

- BioPharmaVantage. (n.d.). Competitive Intelligence in Pharma.

- Clarivate. (n.d.). Cortellis Competitive Intelligence & Analytics.

- Crozdesk. (n.d.). DrugPatentWatch Software.

- PitchBook. (n.d.). DrugPatentWatch Company Profile.

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025). Best Practices for Drug Patent Portfolio Management.

- DrugPatentWatch. (n.d.). Homepage.

- BMC Health Services Research. (2024). Impact of generic drug entry on market shares and prices.

- Association for Accessible Medicines. (n.d.). The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Small Business Assistance: 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity.

- Food and Drug Law Institute. (2016). The Law of 180-Day Exclusivity.

- BioPharm International. (2016). FDA Clarifies How It Handles 180-Day Exclusivity.