Introduction: The High-Stakes Chess Match of Biologics and Biosimilars

In the world of pharmaceuticals, there is no arena more fiercely contested, more intellectually demanding, or more financially significant than the battlefield of biologics and their biosimilar challengers. This isn’t a simple game of checkers; it’s a multi-dimensional chess match played over decades, with billions of dollars in revenue and the future of patient access hanging in the balance. Every move, from the earliest stages of research and development to the final days of market exclusivity, is governed by a complex and ever-evolving web of intellectual property (IP) law. For both the pioneering originator companies and the ambitious biosimilar developers, mastering this game isn’t just an advantage—it’s a prerequisite for survival.

Welcome to the intricate world of biosimilar IP strategy. This is a realm where science, law, and business strategy converge, creating a landscape of immense opportunity and perilous risk. On one side, you have innovator companies that have invested fortunes and decades of research into creating life-changing biologic medicines. Their goal is to build a fortress of patents so robust and so intricate that it can withstand any assault for as long as legally possible. On the other side, you have biosimilar developers, armed with sophisticated science and legal acumen, attempting to find the chinks in that armor. Their mission is to navigate a labyrinth of patents, regulatory hurdles, and litigation risks to bring more affordable versions of these critical medicines to market.

The Dawn of the Biosimilar Era: More Than Just Generics

It’s tempting to think of biosimilars as simply the large-molecule equivalent of traditional small-molecule generics. This, however, would be a profound oversimplification. Small-molecule drugs, like aspirin or Lipitor, are chemically synthesized and have relatively simple, well-defined structures. Creating a generic version is a matter of proving chemical equivalence. Biologics, in contrast, are massive, complex molecules—often proteins—produced in living cell systems. Think of a bicycle versus a Boeing 787 Dreamliner. You can replicate the bicycle perfectly down to the last screw. The Dreamliner, with its millions of interacting parts and complex manufacturing, can only be replicated to be “highly similar,” not identical.

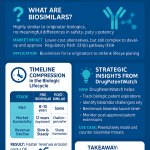

This inherent variability is the crux of the issue. The manufacturing process for a biologic is so integral to the final product that the mantra in the industry is “the process is the product.” A minor change in the cell line, the growth media, or the purification technique can result in a different final molecule. Consequently, a biosimilar is not a generic; it is a biological product demonstrated to be “highly similar” to an approved biologic (the reference product) with no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency [1]. This fundamental scientific difference underpins the entire legal and regulatory framework governing their development and approval, making the IP strategy infinitely more complex than for traditional generics.

Why IP is the Linchpin in the Biosimilar Value Chain

For originator companies, the return on their staggering investment—often exceeding $2.6 billion per new drug—is realized during the period of market exclusivity granted by patents and regulatory data protection [2]. Their IP strategy is not just a legal function; it’s the central pillar of their business model. It involves creating a dense, multi-layered “patent thicket” that covers not just the core molecule but also its formulation, its manufacturing process, methods of use, and even the device used to deliver it. The strength of this fortress directly determines the product’s commercial lifespan and profitability.

For biosimilar developers, IP is the primary obstacle. Before a single dollar is spent on clinical development, a massive amount of resources must be dedicated to intellectual property due diligence. They must meticulously map the patent landscape, identify which patents are valid and which might be weak, strategize on how to “design around” others, and prepare for the inevitable, and often ruinously expensive, litigation. A flawed IP assessment can lead to a blocked launch, crippling damages, or the abandonment of a promising program after hundreds of millions of dollars have already been invested. In this high-stakes environment, your legal and IP teams are just as critical as your scientists and clinicians.

Navigating the Labyrinth: A Roadmap for This Article

This article will serve as your comprehensive guide to cracking the biosimilar code. We will embark on a deep dive into the multifaceted world of biosimilar IP, equipping you with the knowledge and strategic insights needed to navigate this complex terrain. We’ll start by laying the foundational concepts, ensuring a firm grasp of the science and economics at play. We will then dissect the landmark legislation that created the US biosimilar pathway—the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA)—and its intricate “patent dance.”

From there, we will step into the shoes of both players in this strategic game. We’ll explore the “Originator’s Playbook,” detailing the methods used to construct and defend a patent fortress, using the legendary case of Humira® as our guide. Then, we’ll pivot to the “Biosimilar Developer’s Gambit,” outlining the strategies used to clear a path to market, from freedom-to-operate analysis to patent challenges and at-risk launches. We’ll broaden our perspective to the global stage, comparing the US and European systems, and finally, we’ll look to the future, examining the trends and technologies that are set to redefine the biosimilar landscape.

Whether you are a business executive at an innovator company seeking to protect your flagship product or a strategist at a biosimilar firm planning your next launch, this in-depth analysis will provide you with the framework to turn complex IP data into a decisive competitive advantage. Let’s begin.

Foundational Concepts: Understanding the Biologic and Biosimilar Landscape

To devise an effective IP strategy, one must first speak the language of biologics. It is impossible to appreciate the nuances of a patent claim on a monoclonal antibody formulation without understanding why that formulation is critical, or to grasp the significance of a manufacturing process patent without knowing why “the process is the product.” This section builds that essential foundation.

What Makes a Biologic Unique? The Complexity of Large-Molecule Drugs

At its core, the difference between a small-molecule drug and a biologic is a matter of scale and complexity. A small-molecule drug like aspirin has a molecular weight of about 180 daltons. A monoclonal antibody, a common type of biologic, can have a molecular weight of approximately 150,000 daltons—nearly 1,000 times larger [3]. But it’s not just about size; it’s about structure.

Small molecules are simple, stable chemical structures that can be precisely replicated through chemical synthesis. Biologics are vast, three-dimensional proteins with intricate folding patterns (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures) that are essential for their function. They are produced through a complex process of recombinant DNA technology, where genetic material is inserted into a living host cell system (like Chinese hamster ovary, or CHO, cells), which then churns out the desired protein.

From Monoclonal Antibodies to Fusion Proteins: A Spectrum of Complexity

The term “biologic” encompasses a wide range of products. Early biologics included hormones like insulin and human growth hormone. Today, the landscape is dominated by far more complex molecules:

- Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs): These are the workhorses of modern biologic therapy, forming the basis for blockbuster drugs in oncology and immunology like Keytruda® (pembrolizumab) and Humira® (adalimumab). They are Y-shaped proteins designed to target specific antigens in the body.

- Fusion Proteins: These molecules combine different protein domains to create a novel therapeutic effect. A classic example is Enbrel® (etanercept), which fuses a portion of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor to a part of a human antibody.

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): These are highly targeted therapies that link a potent cytotoxic small-molecule drug to a monoclonal antibody, which then acts as a guided missile to deliver the payload directly to cancer cells.

- Cell and Gene Therapies: Representing the cutting edge, these therapies involve modifying a patient’s own cells (like CAR-T therapy) or delivering genetic material to treat disease at its source. While biosimilars to these are still a future concept, they represent the ultimate in biologic complexity.

This complexity means that you can’t characterize a biologic with a single chemical formula. It must be described by its amino acid sequence, its intricate 3D structure, and a host of post-translational modifications (like glycosylation, where sugar chains are attached to the protein) that occur during production and profoundly affect its stability, efficacy, and immunogenicity. Each of these features can, and often does, become the subject of a patent.

The Manufacturing Conundrum: “The Process is the Product”

This phrase is arguably the most important concept in the world of biologics. Because the final product is produced by living cells, the precise conditions of manufacturing are paramount. Everything matters: the specific cell line clone used, the composition of the nutrient-rich media it grows in, the temperature and pH of the bioreactor, the multi-step purification process used to isolate the protein, and the final formulation that keeps it stable.

An originator company will spend years and hundreds of millions of dollars optimizing this process. A biosimilar developer cannot simply copy it, for two reasons. First, the originator’s exact process is almost always a closely guarded trade secret. Second, even if they could replicate it, they would be infringing on numerous process patents that the originator has likely filed. Therefore, the biosimilar developer must independently develop their own manufacturing process that leads to a product that is highly similar to the originator’s.

This is the scientific and regulatory challenge at the heart of biosimilar development. It is also a massive IP opportunity for originators. By patenting every conceivable improvement and variation of their manufacturing process—from cell culture conditions to chromatography steps—they can create a formidable minefield for any potential competitor.

Defining Biosimilarity: A Scientific and Regulatory Tightrope

Because a biosimilar can’t be an identical copy, regulatory agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have developed specialized pathways for their approval. These pathways are designed to be more streamlined than a full, standalone application for a new drug, but they are far more rigorous than for a simple generic.

The FDA’s Totality-of-the-Evidence Approach

In the U.S., the FDA uses what it calls a “totality-of-the-evidence” approach to approve a biosimilar via an Abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA) [1]. This isn’t a single checkbox; it’s a comprehensive evaluation built on a pyramid of data.

- Analytical Studies (The Foundation): This is the most critical part. The biosimilar developer must use a battery of state-of-the-art analytical techniques to demonstrate that their product is structurally and functionally highly similar to the reference product. This involves comparing everything from the amino acid sequence and protein folding to post-translational modifications and biological activity. Any differences must be identified, explained, and justified as not being clinically meaningful.

- Animal Studies: Pre-clinical studies in animals may be required to assess toxicity and pharmacokinetics.

- Clinical Pharmacology Studies: Human studies are conducted to compare the pharmacokinetics (what the body does to the drug) and pharmacodynamics (what the drug does to the body) of the biosimilar and the reference product.

- Clinical Immunogenicity Assessment: A critical study to ensure the biosimilar does not provoke a greater immune response than the originator biologic.

- Additional Clinical Studies (If Necessary): If any uncertainty remains after the preceding steps, the FDA may require a larger comparative clinical trial to confirm safety and efficacy.

The goal is to demonstrate biosimilarity with the minimum necessary amount of clinical data, leveraging the extensive clinical record of the originator product. This reliance on the originator’s data is what makes the pathway “abbreviated,” but the analytical burden is immense.

Interchangeability: The Holy Grail for Biosimilar Developers

In the United States, there is a higher designation a biosimilar can achieve: interchangeability. An interchangeable biosimilar is one that can be substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy level without the intervention of the prescribing healthcare provider (subject to state pharmacy laws) [4].

To achieve this coveted status, a developer must meet all the requirements for biosimilarity plus provide additional data from a “switching study.” This study must show that the risk in terms of safety and reduced efficacy of alternating or switching between the biosimilar and the reference product is no greater than the risk of using the reference product without switching.

Interchangeability is a powerful commercial differentiator. It can significantly boost market uptake, as it simplifies the process for payers and pharmacists. As of mid-2025, only a handful of biosimilars have achieved this status, making it a key strategic goal for many developers. From an IP perspective, the clinical trial design for a switching study could itself become the subject of patents, adding yet another layer to the strategic game.

The Economic Imperative: Market Dynamics and the Push for Biosimilars

The stakes in the biosimilar chess match are astronomical. Biologics are among the most expensive drugs on the market, often costing patients and healthcare systems tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars per year. They represent a disproportionately large share of pharmaceutical spending.

“Although biologics accounted for only 2% of all U.S. prescriptions by volume in 2017, they were responsible for 37% of net drug spending. Projections show that by 2026, the U.S. biologics market could reach approximately $300 billion in sales.” — IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science [5]

This immense spending creates a powerful incentive for the development of biosimilars, which are typically introduced at a discount of 15% to 35% compared to the reference product [6]. These savings can be enormous for healthcare systems, payers, and patients. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that biosimilars could reduce U.S. drug spending by $54 billion over a decade [7].

This economic reality fuels the fire for both sides. For originators, every additional day of market exclusivity for a blockbuster biologic can be worth tens of millions of dollars in revenue. This justifies spending vast sums on legal fees to defend their patent portfolios. For biosimilar developers, the potential to capture even a fraction of a multi-billion-dollar market provides the necessary return on investment to undertake the arduous development process and navigate the inevitable legal challenges. The entire IP battle is fought against this backdrop of immense financial pressure.

The Regulatory Framework: The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA)

To understand the modern biosimilar IP landscape in the United States, you must understand the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA). Passed as part of the Affordable Care Act, the BPCIA was a landmark piece of legislation that attempted to strike a delicate balance: encouraging innovation by providing originators with substantial exclusivities while simultaneously creating a viable pathway for biosimilar competition to lower healthcare costs [8]. The result is a complex, highly procedural framework that dictates the rules of engagement for the IP battle.

Before the BPCIA: The Uncharted Territory

Prior to the BPCIA’s enactment in 2010, there was no legal pathway for the FDA to approve a “biosimilar” version of a biologic. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, which created the modern generic drug industry for small molecules, did not apply to biologics [9]. This meant that any company wanting to create a competitive version of an existing biologic had to file a full Biologics License Application (BLA), complete with a full suite of expensive and time-consuming preclinical and clinical trials, as if it were a brand-new drug.

This created an insurmountable barrier to entry. Without an abbreviated pathway that could rely on the originator’s safety and efficacy data, the economic case for developing a competitive biologic was virtually non-existent. The market was left with branded biologics facing little to no competition, even long after their primary patents had expired. The BPCIA was designed to break this logjam.

The Architecture of the BPCIA: Creating a Pathway for Biosimilars

The BPCIA created two key mechanisms to achieve its dual goals of promoting innovation and competition.

The Abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA)

As discussed previously, the BPCIA created the 351(k) pathway, allowing for the filing of an aBLA. This is the regulatory heart of the Act. By allowing a biosimilar applicant to rely on the safety and effectiveness findings of the originator’s product (the “reference product”), it dramatically reduces the cost and time of development. Instead of proving the drug works from scratch, the applicant’s job is to prove their product is biosimilar to one that is already known to work.

Data and Market Exclusivities for Originators (12 Years)

To balance the creation of this new competitive pathway, the BPCIA granted originator biologics a generous period of statutory exclusivity, completely independent of their patent portfolio. A new biologic reference product receives:

- 4 Years of Data Exclusivity: During this period, a biosimilar developer cannot even submit an aBLA to the FDA for review.

- 12 Years of Market Exclusivity: During this period, the FDA cannot approve an aBLA for a biosimilar version of the reference product.

This 12-year exclusivity is one of the longest in the world and provides a powerful, patent-independent shield for originators [8]. It ensures a substantial period of market monopoly to recoup R&D investment, regardless of what happens in the patent arena. However, this exclusivity runs from the date of the originator’s first licensure. For many biologics, their most valuable patents extend well beyond this 12-year window, making the patent battle still the most critical long-term fight.

The “Patent Dance”: A Choreographed Exchange of IP Information

The most novel and controversial part of the BPCIA is its unique mechanism for handling patent disputes. Rather than letting patent issues fester until a biosimilar is on the verge of launching, the BPCIA created a highly structured, timeline-driven process for exchanging patent information and defining the scope of potential litigation before the biosimilar is even approved. This complex process is colloquially known as the “patent dance” [10].

It’s a delicate, strategic ballet where both the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor (RPS, or originator) have specific steps to perform. Engaging in this dance is largely optional for the biosimilar applicant, but the decision of whether “to dance” or “not to dance” has profound strategic consequences.

Step-by-Step Breakdown of the BPCIA’s Information Exchange

Let’s walk through the key steps of this intricate choreography, assuming the biosimilar applicant chooses to participate:

- The Applicant Provides its aBLA (The Opening Move): Within 20 days of the FDA accepting its aBLA for review, the biosimilar applicant may provide its application and information about its manufacturing process to the RPS. This is the crucial first step and the entry ticket to the dance. It tips the originator off to the biosimilar’s existence and gives them a deep look into the competitor’s product and process.

- The RPS Provides a List of Patents (The First Counter-Move): Within 60 days of receiving the aBLA, the RPS must provide the applicant with a list of all patents it believes could be infringed by the biosimilar. This can include patents the RPS owns or exclusively licenses.

- The Applicant Responds with Its Contentions (The Rebuttal): Within 60 days of receiving the RPS’s patent list, the applicant must provide a detailed statement explaining, on a claim-by-claim basis, why it believes the patents are invalid, unenforceable, or would not be infringed by its product. Alternatively, it can state that it will not market the biosimilar until the patent expires.

- The RPS Responds to the Rebuttal (The Sur-Rebuttal): Within 60 days of receiving the applicant’s contentions, the RPS must provide its own detailed, claim-by-claim rebuttal, explaining why it believes the patents are valid and would be infringed.

- Negotiations for the First Wave of Litigation: After this exchange of contentions, the parties have 15 days to negotiate in good faith to agree on a list of patents that will be the subject of an immediate patent infringement lawsuit.

- Simultaneous Exchange of “First Wave” Patent Lists (If Negotiations Fail): If the parties cannot agree, they simultaneously exchange lists of patents they believe should be litigated. The number of patents the RPS can list is limited by the number the applicant lists.

- The Lawsuit Begins: The RPS then has 30 days to file a patent infringement suit based on the patents identified in the previous steps. This “first wave” of litigation can thus begin long before the biosimilar is approved, giving both sides some early clarity on key patents.

- Notice of Commercial Marketing (A Crucial Late-Stage Step): This step occurs much later. The biosimilar applicant must provide the RPS with at least 180 days’ notice before the date of its first commercial marketing. This notice gives the RPS a second opportunity to seek a preliminary injunction and sue on any patents that were included in the initial lists but not selected for the “first wave” of litigation [11].

Strategic Considerations: To Dance or Not to Dance?

The Supreme Court, in Sandoz v. Amgen (2017), clarified that the biosimilar applicant is not required by federal law to provide its aBLA to the originator and initiate the patent dance [12]. However, refusing to dance has significant consequences.

If the applicant chooses to dance, it gains a degree of control over the timing and scope of the initial litigation. It gets to see the originator’s full list of asserted patents early on and can shape the first wave of litigation. The downside is that it reveals its hand—its product and manufacturing process—to its biggest competitor.

If the applicant chooses not to dance, it keeps its application confidential. The originator is left in the dark. However, the BPCIA allows the originator, in this scenario, to immediately bring a declaratory judgment action for patent infringement on any patent it believes might be infringed. This can lead to a broader, less controlled, and potentially more chaotic litigation. The originator essentially gets to choose the time and place of the battle without the structured confines of the dance.

The decision is a calculated risk. Some biosimilar developers prefer the secrecy of not dancing, believing it gives them a tactical advantage. Others prefer the structure and predictability of the dance, even if it means early disclosure.

The Role of Notice of Commercial Marketing

The 180-day notice of commercial marketing is another critical strategic flashpoint. It acts as a final trigger for litigation before launch. For years, there was debate about whether this notice could be given before FDA approval. The Supreme Court in Sandoz v. Amgen also resolved this, ruling that the notice can be given before or after the biosimilar is licensed by the FDA [12].

This allows biosimilar developers to provide notice while their application is still under review, potentially clearing the way for a launch immediately upon approval without a further 180-day delay. This ruling was a significant victory for biosimilar developers, accelerating their potential timeline to market.

The BPCIA and its patent dance are a uniquely American invention. They create a formal, pre-launch framework for litigation that has no direct equivalent in other parts of the world. Mastering its intricate steps, deadlines, and strategic forks in the road is absolutely essential for any company operating in the U.S. biologics market.

The Originator’s Playbook: Building an Impenetrable Patent Fortress

For an originator company that has successfully brought a blockbuster biologic to market, the game shifts from discovery to defense. The primary objective becomes maximizing the commercial life of the asset by protecting it from biosimilar competition for as long as possible. This is achieved by constructing a dense, overlapping, and multi-generational portfolio of intellectual property known as a “patent thicket.” This is not merely a defensive posture; it is an active, aggressive, and continuous strategy of IP creation and assertion that begins long before the product is approved and continues well past its peak sales.

The “Patent Thicket” Strategy: More Than Just a Numbers Game

A patent thicket is an overlapping set of patent rights that a single entity owns, which can make it difficult for competitors to innovate or enter a market without infringing. It’s a strategy of layering protection so that even if a challenger manages to invalidate or circumvent one patent, dozens or even hundreds more stand in their way. It’s like defending a medieval castle: you have the main keep (the primary patent), but you also surround it with an outer wall, a moat, guard towers, and hidden traps (the secondary patents).

Simply filing a large number of patents is not, in itself, a sophisticated strategy. A true patent thicket is a carefully woven tapestry of different types of patents, each protecting a distinct aspect of the product and its use, creating a web of legal obstacles that is far greater than the sum of its parts.

Primary Patents: The Core Composition of Matter

The foundation of any biologic’s IP portfolio is the primary patent, typically covering the composition of matter. This patent claims the core molecular entity itself—the specific amino acid sequence of the monoclonal antibody or fusion protein. These patents are usually filed very early in the discovery process and provide the broadest and strongest form of protection. They are the “crown jewels” of the portfolio.

However, these primary patents are also the first to expire, typically 20 years from their filing date. For a drug that takes 10-12 years to develop and approve, this may leave only 8-10 years of market life under the protection of this core patent. Therefore, while essential, the primary patent is just the beginning of the story.

Secondary and Tertiary Patents: Layering the Defense

This is where the true artistry of the patent thicket strategy lies. The goal is to obtain patents on every conceivable innovation related to the biologic product after the initial discovery of the molecule. These patents create overlapping layers of protection that can extend market exclusivity for many years, sometimes decades, beyond the expiration of the core composition of matter patent.

H5: Formulation Patents (e.g., excipients, stability)

A biologic is not just the active protein; it’s a complex liquid formulation designed to keep that protein stable, soluble, and safe for injection. Originators invest heavily in developing optimal formulations, and each element can be patented. This includes:

- Specific excipients: The buffers (e.g., citrate, phosphate), surfactants (e.g., polysorbate 80), and tonicity agents used.

- Concentrations: Patenting a high-concentration, low-volume formulation can be a massive commercial advantage, as it allows for less painful subcutaneous injection instead of intravenous infusion.

- Purity levels: Claims directed to a specific level of purity or the absence of certain aggregates can create a high bar for biosimilar developers to meet without infringement.

A biosimilar developer might be able to create a molecule that is highly similar to the originator’s, but if they cannot formulate it for stable, long-term storage and delivery without infringing a dozen formulation patents, they cannot bring a commercially viable product to market.

H5: Delivery Device Patents (e.g., auto-injectors)

Many biologics are self-administered by patients at home using auto-injectors or pre-filled syringes. These devices are complex pieces of engineering, and originators patent every aspect of them: the spring mechanism, the needle guard, the ergonomic design, the safety features, and even the “click” sound the device makes upon successful injection. A biosimilar developer must either develop their own non-infringing device—a significant engineering and regulatory challenge—or wait for the device patents to expire, even if the drug patent is already gone.

H5: Dosing Regimen Patents

As a product is used in the clinic, new and improved ways of administering it are often discovered. Originators will promptly patent these new methods. For example:

- Switching from a bi-weekly injection to a monthly injection.

- A specific loading dose followed by a maintenance dose.

- A weight-based dosing scheme.

If these new regimens become the standard of care, it becomes very difficult for a biosimilar to compete if its label is restricted to an older, less convenient dosing schedule.

H5: Method of Treatment Patents for New Indications

Blockbuster biologics are often approved for an initial indication (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) and then later found to be effective for other diseases (e.g., Crohn’s disease, psoriasis). Each new method of treating a new disease with the same drug is a separate, patentable invention. This “indication stacking” creates a staggered wall of patent expirations. A biosimilar might be able to launch for an indication where the patent has expired, but it would be blocked from being marketed for the other, more lucrative indications until those patents also expire, creating a “skinny label” launch with limited market potential.

H5: Manufacturing and Purification Process Patents

As we’ve established, “the process is the product.” Originators continuously refine and improve their manufacturing processes for efficiency, yield, and purity. Each of these improvements is a patentable invention. This can include:

- The specific host cell line used to produce the protein.

- The composition of the cell culture media.

- Specific steps in the purification process (e.g., a novel chromatography resin or filtration method).

- Analytical methods used to test the quality of the product.

These patents are particularly powerful because a biosimilar developer’s process, while different, must pass through similar steps, creating a high risk of infringement. They force the biosimilar developer to invest heavily in developing novel, non-infringing manufacturing methods.

The Strategic Filing of Continuations and Divisionals

A key tactic in building and maintaining a patent thicket is the sophisticated use of the patent prosecution process itself. By filing “continuation” or “divisional” applications, an originator can keep an application “pending” at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for years. This allows them to:

- Delay patent issuance: This can be used to time the grant of a patent to coincide with a competitor’s expected launch.

- Modify claims: While a patent application is pending, the claims can be amended. This allows the originator to see what a biosimilar developer is doing (for example, through information revealed in the BPCIA patent dance) and then tailor the claims of their pending application to precisely target the competitor’s product or process. This is a powerful and proactive defensive weapon.

Life Cycle Management (LCM): Extending Market Dominance Beyond the Primary Patent

The patent thicket strategy is the core component of a broader business strategy known as Life Cycle Management (LCM). The goal of LCM is to maximize the value of a drug throughout its entire life, and IP is the key enabler.

Case Study: The Humira® (Adalimumab) Fortress

No discussion of patent thickets is complete without mentioning AbbVie’s masterpiece of IP strategy for its drug, Humira® (adalimumab). Humira® was, for many years, the world’s best-selling drug, with annual sales exceeding $20 billion [13]. Its primary composition of matter patent in the U.S. expired in 2016. Yet, through a masterful and aggressive IP and legal strategy, AbbVie prevented any biosimilar competition in the U.S. market until 2023.

How did they do it? AbbVie built a patent fortress of staggering proportions. By the time biosimilars were ready to launch, AbbVie had amassed over 250 patents related to Humira in the US alone, with more than 130 being granted patents [14]. These patents covered everything:

- Dozens of method-of-treatment patents for the 10+ indications for which Humira was approved.

- Multiple patents on high-concentration, citrate-free formulations that reduced injection pain—a major competitive advantage.

- Patents on manufacturing and purification processes.

When biosimilar developers like Amgen, Sandoz, and Boehringer Ingelheim sought to enter the market, they were faced with the prospect of litigating over a hundred patents simultaneously—a financially and logistically daunting task. Ultimately, AbbVie was able to use the strength and density of its patent fortress to negotiate settlement agreements with nearly all potential biosimilar entrants. In these agreements, the biosimilar developers acknowledged the validity of AbbVie’s patents and agreed to delay their U.S. launch until a specified date in 2023, in exchange for AbbVie dropping its lawsuits [15]. This strategy secured AbbVie nearly seven extra years of U.S. market exclusivity after its main patent expired, generating an estimated $100 billion in additional revenue. The Humira story is the quintessential example of a patent thicket used as a powerful commercial tool.

Ethical and Antitrust Considerations: Pay-for-Delay and Product Hopping

The aggressive use of patent thickets and settlement agreements has not gone unnoticed by regulators and critics. These strategies often venture into a legal and ethical gray area, attracting scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and raising antitrust concerns.

- “Pay-for-Delay” or Reverse Payment Settlements: In some settlement agreements, an originator may pay a competitor to stay off the market. The Humira settlements were structured more as royalty-free licenses to enter at a future date, but they have still been the subject of intense antitrust litigation. The central question is whether these agreements are a legitimate outcome of a strong patent portfolio or an illegal scheme to suppress competition [16].

- “Product Hopping”: This is another LCM tactic where an originator makes a minor change to its product (e.g., a new formulation or delivery device) and pulls the old version from the market just before generic or biosimilar competition is set to begin. This “hop” forces patients to switch to the new, patent-protected version, effectively destroying the market for the biosimilar, which can only be substituted for the original version that no longer exists. This practice is also under heavy antitrust scrutiny.

For originator companies, the challenge is to push their IP strategy to the legal limit without crossing the line into anti-competitive behavior that could result in massive fines and damages. It is a constant balancing act between maximizing shareholder value and adhering to the spirit of competition law.

Leveraging Trade Secrets: The Unseen Shield

Finally, no originator’s defensive playbook is complete without a robust trade secret strategy. While patents are public disclosures, trade secrets protect valuable confidential information that is not public. In the world of biologics, the most valuable trade secret is often the exact, optimized manufacturing process.

The specific cell line clone, the precise recipe for the cell culture media, and the subtle tweaks in the purification protocol are all things that a biosimilar developer cannot easily reverse engineer. They are the “secret sauce.” By protecting this information vigorously through strong internal controls, employee agreements, and physical security, an originator adds another powerful, non-patent-based barrier to entry. A competitor might navigate the patent thicket, but they still have to independently develop a process that works, which is a monumental task in itself. Trade secrets, therefore, work in concert with patents to form a complete defensive system.

The Biosimilar Developer’s Gambit: Navigating the Thicket to Reach the Market

If the originator’s game is to build a fortress, the biosimilar developer’s game is to lay siege to it. This requires a completely different mindset and toolset. It is a campaign of meticulous intelligence gathering, strategic probing, and calculated aggression. The goal is to find or create a clear, legally defensible path through the originator’s patent thicket to launch a product and capture a share of a multi-billion-dollar market. This is a high-risk, high-reward endeavor where success hinges on a flawless IP strategy from day one.

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: The Critical First Step

Before any significant investment is made in process development or clinical trials, the biosimilar journey must begin with a comprehensive freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis. An FTO is an exhaustive investigation to determine whether a proposed commercial product or process infringes on the valid, in-force patent rights of any third party. For a biosimilar developer, this means mapping and analyzing every single patent in the originator’s thicket. It is the single most important piece of due diligence in the entire development program.

The Scope and Timing of an FTO Search

An FTO analysis is not a one-time event; it’s a living process. It should begin at the earliest stages of project consideration and be updated regularly as new patents are issued and the development program evolves.

- Initial Landscaping: The process starts with a broad search to identify all patents and published patent applications related to the target biologic. This includes patents covering the molecule, formulations, methods of use for all indications, manufacturing processes, and delivery devices.

- Detailed Analysis: Each identified patent is then meticulously analyzed. A team of patent attorneys and scientists will dissect the patent’s claims—the legally operative sentences that define the scope of the invention—and compare them to the biosimilar developer’s planned product and processes.

- Status Monitoring: The FTO process must be dynamic. The developer must constantly monitor for newly issued patents from the originator’s pending applications, as these can be specifically tailored to target the biosimilar’s activities.

This process creates a detailed “risk map,” color-coding patents based on their expiration date and the perceived risk of infringement (e.g., high risk, medium risk, low risk). This map guides the entire development strategy.

Leveraging Databases and Tools: The Role of Services like DrugPatentWatch

Conducting such a comprehensive FTO analysis manually would be an almost impossible task. The sheer volume of data is immense. This is where specialized databases and intelligence platforms become indispensable tools. Services like DrugPatentWatch provide curated, highly structured data on pharmaceutical patents, patent expirations, litigation, and regulatory exclusivities.

For a biosimilar developer, a platform like this is invaluable. Instead of starting from scratch, they can access a pre-compiled dossier on the target biologic. This can include:

- A comprehensive list of all patents associated with the reference product, including those listed in the FDA’s Orange Book (for drugs) and those asserted in litigation.

- Detailed information on patent status, estimated expiration dates (including any patent term extensions), and legal challenges like Inter Partes Reviews (IPRs).

- Historical data on litigation outcomes and settlement agreements involving the originator, which provides crucial intelligence on their past strategies and behavior.

Using such a service dramatically accelerates the FTO process, reduces the risk of missing a critical patent, and allows the IP team to focus their energy on the more nuanced work of analysis and strategy rather than just data collection. It provides the foundational intelligence upon which the entire biosimilar gambit is built.

From Search to Opinion: Assessing Risk and Making Go/No-Go Decisions

The ultimate output of the FTO process is a formal legal opinion, typically a “non-infringement” or “invalidity” opinion. This document, prepared by patent counsel, provides a detailed legal rationale for why the proposed biosimilar product does not infringe the originator’s patents or why those patents are invalid and unenforceable.

This opinion is crucial for several reasons:

- Internal Decision-Making: It provides the company’s leadership with the risk assessment needed to make a “go/no-go” decision on the project and to justify the massive investment required.

- Investor Confidence: For smaller biotech firms, a strong FTO opinion is essential for securing funding from investors, who will demand to see a clear IP strategy.

- Defense Against Willful Infringement: In the event of litigation, having a well-reasoned FTO opinion from a competent patent attorney can be a powerful defense against a charge of “willful infringement,” which can lead to triple damages [17].

“Clearing the Path”: Strategies for Overcoming Blocking Patents

The FTO analysis will inevitably identify a number of “blocking patents”—those that appear to directly cover the planned biosimilar product or process and will not expire before the desired launch date. The developer’s strategy must then shift to actively clearing these patents out of the way. There are three primary methods for doing this.

Designing Around: The Art of Scientific and Legal Circumvention

The most elegant, though often most difficult, strategy is to “design around” the patent claims. This involves modifying the biosimilar product or manufacturing process in a way that takes it outside the literal scope of the originator’s patent claims, without altering the final product’s biosimilarity.

- Formulation Design-Around: If the originator has a patent on a formulation containing a specific buffer like citrate, the biosimilar developer can invest in developing a new, stable formulation using a different, non-patented buffer like histidine. This requires significant R&D but can completely avoid infringement.

- Process Design-Around: If the originator has patented a specific three-step chromatography purification process, the biosimilar developer can engineer a four-step process or a process that uses different types of chromatography resins, achieving the same level of purity through a different technical route.

Designing around is a delicate dance between science and law. The changes must be significant enough to avoid infringement but not so significant that they destroy biosimilarity to the reference product. It is a high-wire act that requires seamless collaboration between the R&D and IP teams.

Challenging Patent Validity: The Inter Partes Review (IPR) Weapon

If a blocking patent cannot be designed around, the next option is to attack its validity head-on. The America Invents Act of 2011 created a powerful and efficient mechanism for doing this: the Inter Partes Review (IPR) [18]. An IPR is a trial-like proceeding conducted before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the USPTO, where a petitioner can challenge the validity of an issued patent on the grounds that it was not novel or was obvious in light of prior art (e.g., earlier patents and scientific publications).

H5: The PTAB and Its Impact on Biologic Patents

IPRs have become a favored tool for biosimilar and generic developers for several reasons:

- Speed and Cost: An IPR is much faster (typically 12-18 months to a final decision) and less expensive than full-blown district court litigation.

- Lower Burden of Proof: To invalidate a patent claim in an IPR, the petitioner must prove it is unpatentable by a “preponderance of the evidence,” a lower standard than the “clear and convincing evidence” standard used in district court.

- Technical Expertise: The PTAB judges are administrative patent judges with technical backgrounds, who may have a deeper understanding of complex scientific arguments than a lay jury in a district court.

For these reasons, the PTAB has been a challenging venue for patent owners, and biosimilar developers have used IPRs with great success to invalidate key secondary patents in an originator’s thicket, particularly weaker formulation or method-of-use patents.

H5: Strategic Timing of IPR Filings

The timing of an IPR filing is a key strategic decision. It can be filed before BPCIA litigation begins to try and “clear the brush” early. Or, it can be filed in parallel with district court litigation, creating a two-front war for the originator. A successful IPR can knock out a key patent, forcing the originator to drop it from the district court case and potentially leading to a more favorable settlement for the biosimilar developer.

Litigation Strategy: Declaratory Judgment Actions and BPCIA Litigation

Ultimately, clearing the path often requires litigation in federal court. This can be initiated through the formal BPCIA patent dance, or, if the developer chooses not to dance, it may face a declaratory judgment action from the originator. The biosimilar developer’s goal in litigation is to prove to a judge or jury that their product does not infringe the originator’s patents and/or that the patents themselves are invalid.

This is a massive undertaking, involving years of discovery, depositions, expert witnesses, and motions, culminating in a high-stakes trial. The legal costs can easily run into the tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. The biosimilar developer must have the financial resources and the corporate will to see these battles through to the end.

The “At-Risk” Launch: A High-Stakes Bet

Even after all the FTO analysis, design-arounds, and patent challenges, there may still be some patents that remain in dispute as the FDA approval date nears. At this point, the biosimilar developer faces a monumental business decision: should they wait for all litigation to be resolved, which could take years, or should they launch their product “at risk”?

An at-risk launch means proceeding with commercial marketing while patent litigation is still pending. It is one of the biggest gambles in the pharmaceutical industry.

Calculating the Potential Damages vs. First-Mover Advantage

The upside of an at-risk launch is the potential to be the first (or one of the first) biosimilars on the market. This first-mover advantage can be enormous, allowing the developer to secure favorable contracts with payers and establish a strong market share before other competitors arrive. The revenue generated can be in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

The downside is catastrophic risk. If the developer launches at risk and subsequently loses the patent litigation—meaning a court finds their product infringes a valid patent—they could be liable for massive damages, including the originator’s lost profits. This could easily wipe out any revenue gained from the launch and potentially bankrupt the company. Furthermore, the court would issue a permanent injunction, forcing the biosimilar off the market.

The Role of Preliminary Injunctions

An originator’s first line of defense against an at-risk launch is to seek a preliminary injunction (PI) from the court. A PI is a court order that would block the biosimilar launch while the litigation proceeds. To win a PI, the originator must convince a judge that they are likely to succeed on the merits of their infringement case, that they will suffer irreparable harm if the launch proceeds, and that the balance of hardships and the public interest weigh in their favor [19].

The battle over a preliminary injunction is often a “mini-trial” in itself and a critical early test of each side’s case. If the biosimilar developer can defeat the PI motion, it significantly de-risks the at-risk launch strategy, though the ultimate threat of damages remains.

The biosimilar developer’s gambit is a masterclass in calculated risk-taking. It requires deep scientific expertise, razor-sharp legal analysis, a cast-iron will for litigation, and a bold business strategy, all working in perfect harmony.

Global IP Harmonization and Divergence: A World of Challenges

The biosimilar IP battle is not confined to the United States. It is a global affair, played out in major markets across the world. While the fundamental principles of patent law are broadly similar, the specific procedures, timelines, and strategic considerations can vary dramatically from one jurisdiction to another. A successful global biosimilar strategy requires a deep understanding of these differences, particularly between the two largest pharmaceutical markets: the U.S. and Europe.

The US vs. Europe: Contrasting Approaches

While both the U.S. and Europe have robust systems for approving biosimilars and resolving patent disputes, their philosophies and procedures are markedly different.

The European Patent Office (EPO) and Opposition Proceedings

In Europe, patents are typically granted by the European Patent Office (EPO), which provides a single patent application and examination process for up to 44 member and extension states. Once an EP patent is granted, it becomes a bundle of national patents that must be enforced in the courts of each individual country.

A key feature of the European system is the post-grant opposition proceeding [20]. Within nine months of a patent being granted by the EPO, any third party can file an opposition, challenging its validity. This is a centralized, cost-effective, and powerful tool for biosimilar developers. A successful opposition can revoke or limit the patent across all EPO member states in a single action. This is a significant advantage compared to the U.S. system, where a patent must be challenged either through an IPR at the PTAB or in more expensive, slower district court litigation.

Many biosimilar developers proactively monitor for newly granted originator patents at the EPO and use the opposition system as a primary tool for clearing the path in Europe. The grounds for opposition are also broader than for an IPR in the US, allowing challenges based on lack of novelty, inventive step (obviousness), and added subject matter.

The Unified Patent Court (UPC): A New Battlefield

The European patent landscape underwent its most significant change in 50 years with the launch of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) in June 2023 [21]. The UPC is a new, international court system for patent litigation covering, initially, 17 EU member states. It offers two major innovations:

- The Unitary Patent (UP): A single patent that provides uniform protection across all participating EU member states.

- The Unified Patent Court (UPC): A single court system with the power to issue rulings, including pan-European injunctions, that are effective across all participating member states.

The UPC changes the game for both originators and biosimilar developers. For originators, it offers the “dream” of a single lawsuit to stop an infringing biosimilar across most of the EU. The risk of a pan-European injunction makes an at-risk launch in Europe far more dangerous for a biosimilar developer.

Conversely, for a biosimilar developer, the UPC presents the opportunity to achieve a “central revocation” of a problematic patent in a single court action, clearing the path across the entire territory. This high-stakes, “winner-take-all” dynamic is making the UPC the new central battlefield for high-value biosimilar disputes in Europe. Strategic decisions about whether to use the UPC or traditional national courts are now a critical part of any European IP strategy.

The contrast with the U.S. is stark. The BPCIA’s “patent dance” has no equivalent in Europe. Patent litigation in Europe has historically been fragmented across national courts, though the UPC is changing that. There is no 12-year market exclusivity for biologics in Europe; instead, originators receive an “8+2+1” formula: 8 years of data exclusivity, plus 2 years of market exclusivity, plus a potential 1-year extension if the product is approved for a significant new indication [22]. This shorter exclusivity period often makes patent strategy even more critical for originators in Europe.

Key Considerations in Emerging Markets (e.g., China, India, Brazil)

Beyond the U.S. and Europe, emerging markets present their own unique set of opportunities and challenges for biosimilar IP strategy.

Differing Patentability Standards

Countries like China, India, and Brazil are becoming increasingly important pharmaceutical markets. However, their patent laws can have specific nuances.

- India: India is famously strict regarding “secondary” patents. Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act prohibits the patenting of new forms of a known substance unless they demonstrate a significant enhancement in efficacy [23]. This makes it very difficult for originators to build the kind of patent thicket seen in the U.S. and has made India a hub for biosimilar development.

- China: China has been rapidly strengthening its IP system to be more in line with Western standards. It has created specialized IP courts and is working to streamline enforcement. However, challenges in proving infringement and securing significant damages can remain.

- Brazil: Brazil’s patent office (INPI) has historically had a significant backlog, leading to long delays in patent examination. Furthermore, ANVISA, Brazil’s health regulatory agency, plays a role in reviewing pharmaceutical patent applications for patentability, adding another layer of complexity.

A “one-size-fits-all” global IP filing strategy will not work. Originators must tailor their patent claims to meet the specific requirements of each key market, while biosimilar developers must understand the local laws to identify unique opportunities for challenging patents that might be strong elsewhere.

Regulatory Data Protection and Enforcement Challenges

Beyond patents, the strength of regulatory data protection (the equivalent of the BPCIA’s exclusivity periods) varies widely. In some markets, this protection may be weak or non-existent, allowing biosimilar—or “biomimic”—developers to enter the market more quickly.

Enforcement is another critical issue. Even with a strong patent, the ability to get a timely injunction or collect damages in court can be a challenge in some jurisdictions. This practical reality must be factored into any FTO analysis or enforcement strategy. For example, a blocking patent in a country with notoriously slow or unpredictable courts might be considered a lower risk than the same patent in Germany or the U.S., where enforcement is swift and powerful.

Navigating the global IP landscape requires a sophisticated, localized approach. Companies must rely on a network of local counsel and IP experts who understand the specific laws, procedures, and, just as importantly, the practical realities of enforcement in each key market.

The Future of Biosimilar IP: Trends and Predictions

The cat-and-mouse game of biosimilar IP is constantly evolving. Driven by technological advancements, landmark court rulings, and shifting regulatory landscapes, the strategies of today may be obsolete tomorrow. Staying ahead of the curve requires a keen eye on the trends that are shaping the future of this high-stakes field.

The Rise of “Bio-Betters” and Second-Generation Products

One of the most significant trends is the move beyond simple biosimilars to “bio-betters.” A bio-better is a novel biologic that is based on an existing, successful biologic but has been engineered to have superior properties. This could include:

- Improved Efficacy: A more potent molecule that requires a lower dose.

- Enhanced Safety Profile: A molecule designed to be less immunogenic.

- More Convenient Dosing: A molecule with a longer half-life that allows for less frequent injections (e.g., moving from weekly to monthly or quarterly).

For companies with deep biologic expertise, developing a bio-better can be a more attractive strategy than developing a true biosimilar. A bio-better is a new, innovative product that is eligible for its own full suite of patents and the BPCIA’s 12-year exclusivity period. It allows a company to leapfrog the competition rather than just follow it.

From an IP perspective, this creates a new layer of complexity. We are now seeing a landscape with an originator product, multiple biosimilars, and one or more bio-betters all competing in the same therapeutic class. This will lead to even more complex patent litigation, not just between originators and biosimilars, but between competing bio-better developers as well.

AI and Machine Learning in Patent Landscaping and FTO Analysis

The sheer scale of a modern patent thicket, like the one surrounding Humira®, is pushing the limits of human analysis. The FTO process for a major biologic can involve sifting through hundreds of patents and thousands of claims. This is an area ripe for disruption by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML).

AI-powered platforms are emerging that can:

- Automate Patent Searching and Landscaping: AI can analyze vast datasets of patents, scientific literature, and clinical trial data far more quickly and comprehensively than human researchers, identifying relevant prior art and mapping competitive landscapes in minutes rather than weeks.

- Predict Litigation Outcomes: Some advanced tools are being developed to analyze past court decisions and PTAB rulings to predict the likelihood that a specific patent claim will be found valid or invalid, or that a particular judge will rule in a certain way.

- Assist in “Designing Around”: AI can be used to analyze the “white space” in a patent landscape, identifying novel, non-infringing formulations or process variations that human scientists might have missed.

While AI will not replace the strategic judgment of experienced patent attorneys, it will become an indispensable tool for augmenting their capabilities. Companies that embrace these technologies will be able to conduct faster, more thorough, and more predictive IP analysis, giving them a significant competitive edge.

The Evolving Legal Landscape: Key Court Decisions and Legislative Watch-Points

The legal rules of the biosimilar game are constantly being refined by the courts. Key decisions can dramatically alter strategy overnight. For example, the Supreme Court’s decisions in Sandoz v. Amgen fundamentally changed how the BPCIA patent dance and notice of commercial marketing are handled [12].

Areas to watch closely in the coming years include:

- The Written Description and Enablement Doctrines: Recent court decisions, such as Amgen v. Sanofi (which went to the Supreme Court), are raising the bar for what is required to patent a whole class of antibodies based on their function [24]. This could make it harder for originators to obtain very broad “genus” claims, potentially making it easier for biosimilars to design around them.

- Antitrust Scrutiny of Patent Thickets and Settlements: As noted earlier, there is growing pressure from regulators and legislators to curb what are perceived as abuses of the patent system. We can expect continued antitrust litigation and potentially new legislation aimed at limiting the size of patent thickets or the nature of settlement agreements.

- The BPCIA Itself: The BPCIA is now over a decade old. There are ongoing debates in Congress about whether its balance is right. Proposals to reduce the 12-year exclusivity period for originators surface regularly, and any change would have a seismic impact on the industry’s economics.

The Interchangeability Conundrum and its IP Implications

As more biosimilars come to market, the designation of “interchangeability” will become an increasingly important commercial battleground. The first biosimilar to achieve interchangeable status for a major biologic could gain a significant market advantage.

This has IP implications. As we’ve seen, achieving interchangeability requires an additional, complex “switching study.” The design of these studies, the statistical analysis methods used, and the patient-reported outcomes measured could all become the subject of new patent applications. We may see originators or even other biosimilar developers attempting to use patents to block or complicate a competitor’s path to interchangeability. This adds another chessboard to the already complex multi-level game.

The future of biosimilar IP will be defined by greater complexity, more sophisticated technology, and an ever-shifting legal framework. The winners will be those organizations that are not just reactive but are agile, forward-looking, and able to integrate their IP strategy seamlessly into their scientific and commercial decision-making.

Conclusion: IP Strategy as a Core Business Competency

We have journeyed through the labyrinth of biosimilar intellectual property, from the foundational science of large-molecule drugs to the intricate choreography of the BPCIA patent dance, the fortress-building of originators, and the siege tactics of their challengers. What becomes abundantly clear is that in this domain, intellectual property is not a secondary legal function; it is a primary driver of business success and a core competency for any serious player.

The “code” to be cracked is not a single secret but a dynamic, multi-faceted understanding of the interplay between science, law, regulation, and commerce. It requires a dual perspective—the ability to think like both a defender and an attacker, to understand the motivations and strategies of the other side as well as your own.

Synthesizing the Dual Perspectives: Offense and Defense

For the originator, the strategy is one of proactive, continuous, and multi-layered defense. It is about foresight—patenting not just the product of today, but all conceivable improvements, uses, and variations of the product of tomorrow. It is about building a patent thicket so dense and well-constructed that it deters challengers before they even begin, and forces those who dare to enter into settlements on favorable terms. It is a long-term strategy of life cycle management where IP is the central tool for maximizing the value of a breakthrough innovation.

For the biosimilar developer, the strategy is one of surgical precision, calculated risk, and relentless execution. It begins with deep intelligence—a masterful command of the patent landscape provided by thorough FTO analysis. It proceeds with a multi-pronged attack: cleverly designing around patents where possible, challenging their validity through mechanisms like IPRs where necessary, and demonstrating the courage to litigate and, when the calculation is right, to launch at risk. It is a strategy of finding the weakest link in the fortress wall and exploiting it with maximum efficiency.

The End Game: Balancing Innovation, Access, and Competition

Ultimately, this high-stakes game of IP chess serves a broader societal purpose. The system, for all its complexity and controversy, is designed to strike a delicate balance. The powerful protections afforded to originators are intended to provide the incentive for companies to undertake the monumental risk and expense of developing new, life-saving biologic medicines. Without the promise of a profitable period of exclusivity, that innovation pipeline would dry up.

At the same time, the pathways and legal mechanisms available to biosimilar developers are designed to ensure that this period of exclusivity is not infinite. They introduce competition that drives down prices, expands patient access, and forces originators to continue innovating rather than resting on their laurels.

Cracking the biosimilar code is about more than just winning a legal battle or securing a market. It’s about mastering the system that fuels the engine of biopharmaceutical progress. The companies that succeed—whether they are originators defending their creations or biosimilars bringing competition to the market—will be the ones who treat IP not as a static legal obstacle, but as a dynamic, strategic asset to be cultivated, wielded, and respected. They understand that in the world of biologics, the strength of your IP is the strength of your business.

Key Takeaways

- IP is Central, Not Ancillary: For both originator and biosimilar companies, IP strategy is a core business function that must be integrated with R&D, regulatory, and commercial strategy from the very beginning.

- The “Patent Thicket” is a Multi-Layered Defense: Originator success relies on building a dense and diverse portfolio of patents covering not just the core molecule, but also formulations, manufacturing processes, methods of use, and delivery devices to extend market exclusivity well beyond the life of the primary patent.

- FTO Analysis is Non-Negotiable for Biosimilars: A comprehensive and dynamic Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is the most critical due diligence for any biosimilar program. Leveraging tools like DrugPatentWatch is essential for efficiently mapping the complex patent landscape.

- The BPCIA “Patent Dance” is a Strategic Choice: The BPCIA’s unique pre-litigation information exchange is a complex process with significant strategic implications. The decision of whether “to dance” or not shapes the entire litigation landscape.

- Clearing the Path Requires a Multi-Pronged Attack: Biosimilar developers must use a combination of strategies to overcome blocking patents, including designing around claims, challenging patent validity via Inter Partes Reviews (IPRs), and preparing for full-scale litigation.

- Global Strategies Must Be Localized: The IP and regulatory landscapes for biosimilars vary significantly between the US, Europe (with its new UPC system), and key emerging markets. A one-size-fits-all approach is doomed to fail.

- The Future is More Complex: Trends like the rise of “bio-betters,” the use of AI in patent analysis, and evolving legal standards will continue to make the biosimilar IP field more dynamic and demanding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the single biggest mistake a biosimilar developer can make in their IP strategy?

The single biggest mistake is performing an inadequate or static Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis. Many companies treat FTO as a one-time checkbox at the start of a project. However, the patent landscape is dynamic; originators constantly file and are granted new patents from pending applications, often with claims strategically drafted to ensnare competitors. A biosimilar developer who fails to continuously monitor for new patents and update their FTO analysis can find themselves blindsided late in development by a “submarine” patent that completely blocks their launch, rendering years of work and hundreds of millions of dollars of investment worthless.

2. How can an originator company’s “patent thicket” strategy backfire?

While powerful, a patent thicket strategy can backfire in two main ways. First, it can attract significant antitrust scrutiny. If a court or regulator like the FTC determines that the thicket was created and asserted not to protect legitimate innovation but to unlawfully block competition, the originator can face massive fines and treble damages in civil suits. Second, it can be a costly distraction. Defending hundreds of patents in multiple jurisdictions is astronomically expensive. If many of those patents are ultimately found to be weak or invalid, the company may have wasted enormous resources that could have been invested in R&D for the next generation of innovative products. It can also damage a company’s public reputation, painting them as a firm that prioritizes litigation over innovation.

3. What is the practical difference between “biosimilar” and “interchangeable” status from an IP and market perspective?

From a market perspective, the difference is significant. A “biosimilar” can be prescribed by a doctor, but it cannot be automatically substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy without the prescriber’s explicit permission. An “interchangeable” biosimilar can be automatically substituted by a pharmacist (subject to state law), making it a much more seamless competitor. This can lead to faster and deeper market penetration. From an IP perspective, the difference lies in the data required. To get interchangeability, a developer must conduct a complex “switching study,” which itself can become an IP battleground. For example, an originator might try to patent certain clinical trial designs or patient-reported outcome metrics to make it harder for a competitor to successfully design and execute a switching study.

4. How is the Unified Patent Court (UPC) in Europe changing the game for biosimilar litigation?

The UPC fundamentally centralizes and raises the stakes of biosimilar patent litigation in Europe. Before the UPC, a patent battle had to be fought country by country, which was slow and expensive. Now, an originator can potentially obtain a single injunction that blocks a biosimilar across 17+ countries in one fell swoop, making an “at-risk” launch far more perilous for biosimilars. Conversely, a biosimilar can use the UPC to revoke a problematic patent across that entire territory in a single action. This “winner-take-all” system accelerates timelines and concentrates risk, forcing both sides to be extremely confident in their legal positions before engaging in litigation. It makes Europe feel much more like the high-stakes US litigation environment.

5. With the rise of AI, how will patent analysis for biologics change in the next 5-10 years?

AI will transform patent analysis from a largely manual, labor-intensive process into a more predictive, data-driven strategic function. In 5-10 years, we can expect AI platforms to not just conduct comprehensive prior art searches in seconds, but to also analyze the entire “thicket” of a product, identifying the most critical patents, assessing their likely validity based on historical PTAB and court data, and even suggesting specific “design-around” strategies for formulations or processes by identifying unpatented “white space.” For attorneys and IP strategists, this means the focus will shift from data gathering and manual analysis to higher-level interpretation and strategic decision-making based on AI-generated insights. The speed and depth of AI analysis will become a standard tool and a major competitive differentiator.

References

[1] U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2019). Biosimilar and Interchangeable Biologics: More Treatment Choices. [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-biologics-more-treatment-choices

[2] DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20-33.

[3] Roger, S. D., & Mikhail, A. (2007). Biosimilars: opportunity or cause for concern?. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences, 10(3), 405-410.

[4] U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2017). Considerations in Demonstrating Interchangeability With a Reference Product: Guidance for Industry. [Online]. Available: https://www.fda.gov/media/124907/download

[5] IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. (2018). Biosimilars in the United States: Providing more patients with access to biological medicines. [Online]. Available: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/biosimilars-in-the-united-states-2018

[6] Association for Accessible Medicines. (2022). 2022 Generic and Biosimilar Drugs Access & Savings in the U.S. Report. [Online]. Available: https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2022-generic-and-biosimilar-drugs-access-savings-report

[7] Congressional Budget Office. (2019). Biologic Drugs, Biosimilars, and the BPCIA. [Online]. Available: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/54949

[8] Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009, 42 U.S.C. § 262.

[9] Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch-Waxman Act), Pub. L. No. 98-417, 98 Stat. 1585.

[10] Hakim, A. & Welch, A. R. (2017). The BPCIA “Patent Dance”: What Is It And Can You Avoid It?. Life Sciences Intellectual Property Review.

[11] Amgen Inc. v. Sandoz Inc., 794 F.3d 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

[12] Sandoz Inc. v. Amgen Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1664 (2017).

[13] Fierce Pharma. (2021). The top 20 drugs by worldwide sales in 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.fiercepharma.com/special-report/top-20-drugs-by-2020-sales

[14] I-MAK (Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge). (2021). Overpatented, Overpriced: How Just One Drug Company Gamed the System to Create a Monopoly and Keep Prices High. [Online]. Available: https://www.i-mak.org/humira-report-2021/

[15] Cedrone, L. (2022). Humira Biosimilars: The Unprecedented Launch. The Center for Biosimilars.

[16] Federal Trade Commission. Pay-for-Delay. [Online]. Available: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

[17] Halo Electronics, Inc. v. Pulse Electronics, Inc., 136 S. Ct. 1923 (2016).

[18] Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Pub. L. 112–29, 125 Stat. 284 (2011).

[19] Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7 (2008).

[20] European Patent Office. (n.d.). Opposition. [Online]. Available: https://www.epo.org/applying/european/opposition.html

[21] Unified Patent Court. (n.d.). The Unified Patent Court. [Online]. Available: https://www.unified-patent-court.org/

[22] European Medicines Agency. (n.d.). Marketing authorisation. [Online]. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation

[23] The Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005, No. 15 of 2005, § 3(d) (India).

[24] Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, 598 U.S. ___ (2023).