Introduction: Beyond the Molecule – Why Your Patent Portfolio is Your Most Valuable Asset

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical innovation, the journey from a promising molecule in a petri dish to a life-changing medicine on a pharmacy shelf is a marathon fraught with scientific, regulatory, and financial hurdles. It’s a multi-billion dollar gamble where failure is the norm and success is the rare, celebrated exception. But what truly underpins this entire ecosystem, allowing companies to recoup their staggering investments and fund the next wave of discovery? It isn’t just the science, the clinical trials, or the marketing prowess. It’s the invisible, yet unbreakably strong, framework of intellectual property (IP)—specifically, the patent portfolio.

For too long, many have viewed patents as dusty legal documents, a necessary but unglamorous cost of doing business, managed by a siloed legal department. This perspective is not just outdated; it’s dangerous. In the 21st-century biopharmaceutical landscape, your patent portfolio is not a static collection of certificates. It is a dynamic, strategic, and arguably your most valuable corporate asset. It is the very engine of value creation, the shield that protects your innovation, the sword that carves out market exclusivity, and the currency that fuels partnerships, mergers, and acquisitions.

This guide is designed for the business leaders, the R&D visionaries, and the IP strategists who understand this paradigm shift. We’re moving beyond the basics of “what is a patent?” to the sophisticated art and science of “how do we build and manage a portfolio that maximizes value and secures competitive dominance?” We will journey through the entire lifecycle of a drug’s IP, from the earliest strategic filings to the complex end-of-life strategies that navigate the treacherous patent cliff. We’ll explore how to forge an unbreakable link between your IP strategy and your corporate vision, turning your patent portfolio from a defensive necessity into a powerful offensive weapon. Welcome to the new era of drug patent portfolio management.

The Pharmaceutical Imperative: High Stakes, High Rewards

To truly grasp the central role of patent portfolios, we must first appreciate the unique economic environment of the pharmaceutical industry. It’s a world of extremes, defined by a challenging and often paradoxical set of financial realities. Understanding this context isn’t just background information; it’s the fundamental “why” behind every strategic IP decision you’ll ever make.

The R&D Cost Conundrum and the Role of Exclusivity

The process of bringing a new drug to market is one of the most expensive commercial endeavors on the planet. The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, a leading authority on the topic, has consistently pegged the cost at staggering figures. Their 2016 study estimated the pre-tax cost of developing a new prescription drug, including the costs of failed projects, to be an eye-watering $2.6 billion [1]. More recent analyses suggest this figure continues to climb, driven by increasingly complex diseases, more stringent regulatory requirements for clinical trials, and the high rate of attrition. For every one drug that successfully navigates the gauntlet of preclinical research, Phase I, II, and III trials, and finally gains regulatory approval, countless others fail along the way.

The cost of these failures isn’t just written off; it’s baked into the business model. The revenue from the one successful drug must cover its own development costs and the sunk costs of all its fallen comrades. How can any company possibly justify such a risky investment? The answer is a single, powerful concept: market exclusivity.

Patents provide a time-limited monopoly, typically 20 years from the filing date, during which the innovator can commercialize their drug without direct competition from generic manufacturers. This period of exclusivity is the sole window of opportunity to recoup the massive R&D outlay and generate the profits necessary to invest in future research. Without the promise of this protected market, the financial incentive to undertake such a risky venture would evaporate almost overnight. The entire pharmaceutical innovation ecosystem as we know it would collapse. Patents are not a bonus; they are the bedrock.

Patents as the Bedrock of Biopharmaceutical Business Models

Consider the business model of a typical innovative pharmaceutical company. It’s not like a consumer goods company that can rely on brand loyalty or a tech company that can iterate a product monthly. The core product—the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)—is a specific chemical entity. Once its patent expires, competitors can, with regulatory approval, produce a chemically identical version (a generic) or a highly similar version (a biosimilar) at a fraction of the cost, as they don’t bear the burden of discovery and development.

This event, known as the “patent cliff,” is a dreaded moment for any pharmaceutical company. It’s not uncommon for a blockbuster drug to lose 80-90% of its market share to generic competition within a year of patent expiry [2]. This precipitous drop in revenue can be catastrophic for a company, especially if a single drug accounts for a significant portion of its income.

This is where the concept of a portfolio becomes paramount. A single patent on a single molecule is a fragile thing. It can be challenged in court, designed around by a clever competitor, or simply expire. A robust patent portfolio, however, is a fortress. It’s a multi-layered defense system of interconnected patents covering not just the core molecule, but also its methods of use, its specific formulation, its manufacturing process, its various crystalline forms (polymorphs), and even its combination with other drugs. This portfolio approach transforms a single point of vulnerability into a deep, resilient web of protection that can extend a drug’s commercial life, deter competitors, and create a far more durable and valuable asset.

Defining the Modern Patent Portfolio: More Than Just a Collection of Documents

Having established the critical need for patents, we must now evolve our understanding of what a patent portfolio truly is in the modern business context. If you still envision it as a filing cabinet full of legal certificates, it’s time for an upgrade. A modern, high-performing portfolio is a living, breathing entity that should be as dynamic and responsive as your R&D pipeline or your commercial strategy.

From a Defensive Shield to an Offensive Sword

The traditional view of a patent portfolio is purely defensive. It’s a shield. You invent something, you patent it to stop others from copying you, and you hope that shield holds up if challenged. This is, of course, a crucial function. A strong core patent on a blockbuster drug is the ultimate shield, protecting billions in revenue.

However, the best-in-class companies have learned to wield their portfolios as an offensive sword. What does this mean in practice?

- Shaping Competitive Behavior: A strategically constructed portfolio can create a “patent thicket” around a particular therapeutic area. By patenting not only your lead compound but also related molecules, potential metabolites, and alternative mechanisms of action, you can make it incredibly difficult and risky for a competitor to operate in your space. This can force them to pivot to less promising areas or to abandon their program altogether.

- Creating Licensing Opportunities: Sometimes, your portfolio contains assets that are not core to your own commercial strategy but may be incredibly valuable to another company. These could be patents for a different therapeutic indication, a novel drug delivery technology, or a manufacturing process. Proactively out-licensing these assets can create new, non-dilutive revenue streams from R&D that would otherwise sit idle.

- Fueling Strategic Partnerships: In co-development or co-marketing deals, a strong and well-defined IP portfolio is your primary bargaining chip. It defines what you bring to the table and is the basis for valuing your contribution, influencing everything from milestone payments to royalty rates.

- Deterring Litigation: A powerful, multi-layered portfolio can act as a powerful deterrent to potential generic challengers. When a generic company analyzes the patent landscape of a target drug, a dense and well-prosecuted portfolio presents a far more formidable and expensive legal challenge than a single, easily targeted patent. They may choose to wait for expiry or focus on a less well-protected product.

The Portfolio as a Living, Breathing Strategic Tool

The most critical mindset shift is to see your portfolio not as a static archive but as a dynamic tool that requires constant attention, curation, and strategic management. A patent, once granted, isn’t “done.” It has a lifecycle, costs, and strategic value that can change dramatically over time.

Active portfolio management involves:

- Regular Audits: Continuously evaluating each patent and patent family against current business goals. Is this patent still relevant to our commercial products or our R&D pipeline? Is its geographic coverage aligned with our market priorities?

- Strategic Pruning: Making the tough but necessary decision to abandon patents that no longer serve a strategic purpose. Maintaining a patent, with its associated fees and administrative overhead, costs money. Culling low-value patents frees up resources that can be reinvested in protecting more promising innovations.

- Targeted Filing: Aligning new patent filings directly with the commercial and R&D strategy. Instead of patenting everything that seems novel, the focus shifts to patenting innovations that create tangible commercial value and strengthen the competitive position of key assets.

- Lifecycle Planning: Thinking about the IP strategy for a drug not just at the beginning, but throughout its entire lifecycle. This includes filing for patents on next-generation improvements, new uses, and new formulations long before the original patent is set to expire.

In essence, managing a drug patent portfolio today is akin to managing a high-value investment portfolio. It requires a clear strategy, a deep understanding of the market, a willingness to divest underperforming assets, and a constant search for new opportunities to maximize returns. It’s a discipline that lives at the intersection of law, science, and business, and mastering it is no longer optional—it’s essential for survival and success.

Laying the Foundation: Aligning Your IP Strategy with Corporate Vision

The most elegantly drafted patent is worthless if it protects an asset the company doesn’t care about. The most expensive global filing campaign is a waste of money if it covers markets the company has no intention of entering. The genesis of a powerful patent portfolio isn’t in the lab or the lawyer’s office; it’s in the boardroom. An IP strategy that is not deeply and inextricably linked with the overall corporate vision is a ship without a rudder, destined to drift aimlessly and likely run aground.

The Critical First Step: IP Strategy as a Core Business Function

For decades, in many organizations, the patent department was seen as a support service. The R&D team would invent something, “throw it over the wall” to the patent attorneys, who would file a patent, and the business leaders would only get involved if a lawsuit appeared. This siloed approach is a recipe for strategic misalignment and missed opportunities.

Moving IP from the Legal Basement to the Boardroom

Transforming IP into a core business function requires a fundamental cultural and organizational shift. The Chief Intellectual Property Officer (CIPO) or Head of IP should have a seat at the strategic planning table, alongside the heads of R&D, Commercial, Business Development, and Finance. Why is this so crucial?

- Informed Decision-Making: When the IP team understands the company’s long-term goals—which therapeutic areas are priorities, which markets are targeted for expansion, what the M&A appetite is—they can proactively shape the patent portfolio to support those goals. They can advise on the patentability of early-stage research, highlight potential IP risks in a proposed acquisition, and ensure that patent filing budgets are allocated to the projects that matter most to the company’s future.

- Reciprocal Information Flow: This isn’t a one-way street. The business leaders also need to understand the IP landscape. The IP team can provide competitive intelligence on what rivals are patenting, identify “white space” opportunities for innovation in crowded fields, and explain the strength and longevity of the company’s own exclusivity for forecasting purposes. A CEO who understands the patent term of their lead product is better equipped to communicate with investors and plan for the inevitable patent cliff.

- Resource Allocation: Patenting is expensive. Filing a single patent family in key jurisdictions can easily cost hundreds of thousands of dollars over its lifetime. Without strategic alignment, these resources can be squandered. By integrating IP into business planning, you ensure that your IP budget is treated as a strategic investment, not an unmanaged expense, and is directed toward creating the most commercial value.

As former USPTO Director Andrei Iancu stated, “Intellectual property is the foundation of our modern economy… It is the incentive for creation and the key to turning a brilliant idea into a real-world product or service that can change the world” [3]. For that to happen, the stewards of that IP must be integrated into the core of the business they are tasked to protect.

Case Study: How Strategic Alignment Drove Success for a Major Blockbuster

Consider the story of a (hypothetical, but representative) drug, “Innovire,” for a chronic autoimmune disease.

- Siloed Approach (The Counter-Example): In a company with poor alignment, the scientists developing Innovire would have isolated the lead molecule and sent it to the patent team. The lawyers, working in a vacuum, would have filed a strong but narrow composition of matter patent covering the molecule itself. The drug becomes a blockbuster. Years later, as the core patent expiry looms, the company scrambles to find ways to extend its life, but it’s too late. Competitors had already designed around the manufacturing process and developed alternative, extended-release formulations, as these were never protected by the innovator. The company faces a massive patent cliff.

- Integrated Approach (The Best Practice): In a company with strong strategic alignment, the process is different from day one.

- Early Stage: The IP team is embedded with the R&D team. They understand that the long-term corporate vision is to build a franchise in this disease area.

- Strategic Filing: They don’t just file on the lead molecule. They work with the commercial team to understand future market needs. The commercial team flags that a once-daily oral pill will be a key differentiator. In response, the R&D and IP teams work together to develop and patent a specific extended-release formulation. The manufacturing team develops a novel, cost-effective synthesis method, which is also immediately patented. The clinical team discovers it’s particularly effective in a specific sub-population of patients, leading to a new method-of-use patent.

- The Result: When the original composition of matter patent on Innovire is nearing expiry, the company has a fortress of secondary patents. A generic company can’t just copy the molecule; they have to develop their own formulation (which may be less effective or convenient), their own manufacturing process (which may be more expensive), and they can’t market it for the patented sub-population. This multi-layered portfolio extends the product’s value, smooths the revenue decline, and provides a much stronger, more durable market position, all because the IP strategy was aligned with the business vision from the very beginning.

Mapping Your Innovation to Market Needs: The IP-Commercial Nexus

Strategic alignment goes deeper than just having the right people in the right meetings. It requires concrete processes and frameworks to ensure that the innovation engine (R&D) is building things that the commercial engine can sell, and that the IP engine is protecting the value at every step. This is the IP-Commercial Nexus.

Identifying Core vs. Ancillary Technologies

Not all innovations are created equal. A portfolio management system that treats a revolutionary new drug molecule the same as a minor improvement to a manufacturing buffer solution is fundamentally flawed. A key practice is to classify your innovations and the corresponding IP.

- Core IP: This is the IP that protects the heart of your revenue-generating products. For a small molecule drug, the composition of matter patent is the quintessential core IP. For a biologic, it might be the patent on the specific antibody sequence. This IP must be protected at all costs, with the broadest possible claims, in every commercially relevant market. The budget for filing, prosecuting, and defending this IP should be virtually unlimited.

- Strategic IP: This layer of IP strengthens the position of the core product. It includes patents on key formulations, methods of medical use for specific patient populations, combination therapies, and novel dosing regimens. This IP is crucial for lifecycle management and creating a “patent thicket” to deter competitors. Its filing strategy should be broad but targeted to key markets.

- Ancillary IP: This category includes innovations that are potentially valuable but not directly linked to a core commercial product. Examples might include a new high-throughput screening platform, a novel purification technique, or a diagnostic marker discovered during a clinical trial. This is where strategic decisions become critical. Is this technology something that could be out-licensed to generate revenue? Could it be the basis of a new spin-out company? Or is it a trade secret that shouldn’t be patented at all? Ignoring ancillary IP is a mistake; it can be a hidden source of value if managed correctly.

By categorizing your portfolio, you can create a clear, tiered management strategy, ensuring that your most valuable resources are dedicated to protecting your most valuable assets.

The Role of Commercial Teams in Guiding Patent Filing

The commercial team possesses invaluable insights that must be fed back into the IP strategy. They are the front line, understanding the needs of patients, the prescribing habits of physicians, and the reimbursement landscape of payers.

How can their input guide patenting?

- Identifying Unmet Needs: Commercial teams can identify key unmet needs that, if solved, would create significant value. For example, they might report that physicians are hesitant to prescribe a drug because of a difficult dosing schedule. This information is a direct signal to the R&D and IP teams to prioritize the invention and patenting of a new, more convenient formulation (e.g., a once-weekly injection instead of a daily pill).

- Defining the Competitive Set: They have the clearest view of the competitive landscape, not just from a patent perspective but from a market perspective. Which competitor drugs are gaining traction and why? What are their weaknesses? This intelligence can guide the search for “white space” and inform the drafting of patent claims that explicitly differentiate your product from the competition.

- Geographic Prioritization: The commercial team’s global market strategy should directly dictate the patent filing strategy. There is no point in spending $50,000 to obtain and maintain a patent in a country where the company has no plans to launch the product and the market for infringement is negligible. Conversely, for key target markets like the US, Europe, China, and Japan, a comprehensive and aggressive filing strategy is non-negotiable.

This continuous dialogue between the commercial, R&D, and IP functions creates a virtuous cycle. Market needs inform R&D priorities, R&D innovation is captured by the IP team, and the resulting strong IP position enables the commercial team to successfully market the product. This integration is the foundational principle upon which every other best practice in portfolio management is built.

The Architecture of a Fortress: Building a Robust and Defensible Portfolio

Once the strategic foundation is laid, the work of construction begins. Building a drug patent portfolio is like designing and building a medieval fortress. A single, tall wall might seem imposing, but it has single points of failure. A true fortress has concentric walls, moats, gatehouses, and strategically placed towers. It’s a defense-in-depth system. Similarly, a world-class patent portfolio is not reliant on a single patent but is a carefully architected, multi-layered structure designed to be resilient, defensible, and intimidating to would-be attackers.

The Blueprint: Strategic Patent Drafting and Prosecution

The individual patents are the bricks and mortar of your fortress. The quality of their construction—the drafting of the application and the strategy for its prosecution—determines the ultimate strength of the entire portfolio. This is a process that blends deep scientific understanding with the nuanced craft of legal claimsmanship.

The Composition of Matter Patent: The Crown Jewel

In the world of small-molecule pharmaceuticals, the composition of matter (CoM) patent is the undisputed crown jewel. This patent claims the novel chemical structure of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. Its power lies in its breadth. A CoM patent protects the molecule regardless of how it’s made, how it’s formulated, or what disease it’s used to treat.

- Why it’s King: A generic competitor cannot, under any circumstances, sell a product containing that specific molecule in a jurisdiction where the CoM patent is in force. It’s a complete roadblock. Therefore, securing a valid and enforceable CoM patent is the absolute top priority for any new chemical entity (NCE).

- The Drafting Imperative: Given its importance, the drafting of the CoM patent application is a moment of maximum leverage. The claims must be crafted with exquisite care. They should be broad enough to cover not just the single lead compound but also a reasonable scope of related structures (a genus claim) to prevent competitors from making a trivial modification to circumvent the patent. However, the claims must also be narrow enough to be fully supported by the experimental data in the application, ensuring they can withstand challenges on grounds of lack of enablement or written description. This balancing act is a high-wire art performed by skilled patent attorneys.

For biologics, the equivalent of the CoM patent is often a patent claiming the specific amino acid sequence of an antibody or protein, or the nucleotide sequence of a gene therapy. The principle is the same: protecting the core therapeutic agent itself.

Layering Protection: Method of Use, Formulation, and Polymorph Patents

While the CoM patent is the crown jewel, a crown jewel alone does not make a fortress. The most sophisticated IP strategies rely on creating a “patent estate” through layers of secondary patents. These patents often have later filing and expiration dates than the CoM patent, serving to extend the product’s effective commercial life well beyond the expiry of the initial patent.

- Method of Use (MoU) Patents: These patents don’t claim the drug itself, but rather its use to treat a specific disease or patient population. For example, after a drug is approved for rheumatoid arthritis, further research might show it’s also effective for psoriasis. A new MoU patent can be filed for this new indication. This is incredibly powerful. Even after the CoM patent expires, a generic company could be blocked from marketing their version for the treatment of psoriasis if the MoU patent is still in force. This practice, known as “skinny labeling,” is a central feature of modern pharmaceutical competition [4].

- Formulation Patents: A drug’s formulation—the combination of the API with various inactive ingredients (excipients) to create a stable, effective, and convenient final product—is a hotbed of innovation. Is it a tablet, a capsule, an injectable liquid? Is it an extended-release version that only needs to be taken once a day? Each of these improved formulations can be patented. These patents can be incredibly valuable, as patients and doctors often prefer the convenience of an advanced formulation, making it difficult for a generic competitor with a more basic version to gain market share.

- Polymorph Patents: Many small-molecule drugs can exist in different solid-state crystalline forms, known as polymorphs. These polymorphs can have different physical properties, such as solubility and stability, which can significantly impact the drug’s performance. Discovering and patenting a novel, more stable, or more bioavailable polymorph can create another powerful layer of protection. A competitor might be able to make the original molecule, but if they can’t formulate it into a stable pill without infringing your polymorph patent, their path to market is much harder.

- Manufacturing Process Patents: While often harder to enforce (as infringement happens behind the closed doors of a competitor’s factory), patents on a novel, efficient, or high-purity manufacturing process can add yet another hurdle for competitors and can be a source of valuable trade secrets.

This layering strategy creates a complex web of IP that presents a daunting challenge to a generic or biosimilar developer. They can’t just invalidate one patent; they have to navigate or challenge an entire portfolio, a far more expensive and risky proposition.

The Art of the Claim: Balancing Breadth and Defensibility

At the heart of every patent is a set of numbered sentences called “claims.” These claims legally define the boundaries of the invention. Think of them as the legal deed to your intellectual property; they define the precise plot of land you own. The strategy behind drafting these claims is perhaps the most critical element of building a defensible patent.

- The Peril of Greed (Overly Broad Claims): There’s a temptation to write claims that are as broad as possible, to try and capture a vast technological territory. For example, claiming “any compound that inhibits enzyme X” without providing sufficient examples or a clear structural basis. The problem is that such broad claims are highly vulnerable to attack. A challenger can argue that the patent doesn’t actually teach someone how to make and use everything that is claimed (enablement) or that the inventor wasn’t in possession of the full scope of the invention when the patent was filed (written description). An invalidated claim protects nothing.

- The Peril of Timidity (Overly Narrow Claims): The opposite error is to write claims that are too narrow, cleaving too closely to the specific example developed in the lab. For instance, claiming only the single molecule you tested. The danger here is that a competitor can make a tiny, inconsequential modification—swapping a methyl group for an ethyl group, for example—and potentially design around the patent entirely, even if their molecule works in the exact same way.

- The Strategic Middle Ground: The art lies in finding the sweet spot. This often involves a “picture frame” or “cascading” claim strategy. You start with a broad “genus” claim that captures the core inventive concept, supported by a well-reasoned scientific hypothesis. Then, you include progressively narrower claims (sub-genera, specific species) that are more and more tightly linked to the experimental data. This creates fallback positions. If a court invalidates your broadest claim, you can still fall back on a narrower, more easily defended claim that still protects your commercial product.

This intricate work requires a deep, collaborative dialogue between the scientists who understand the technology and the patent attorneys who understand the law.

Global Prosecution Strategy: Thinking Globally, Acting Locally

A patent is a national right. A US patent provides no protection in Germany or Japan. Therefore, for any drug with global commercial potential, a strategic international filing strategy is essential. This is not a one-size-fits-all process; it requires a nuanced understanding of different legal systems, market priorities, and cost-benefit analyses.

Navigating the Patent Trinity: USPTO, EPO, and JPO

For most pharmaceutical companies, the “Patent Trinity” represents the three most important patent offices in the world:

- The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO): The largest and most commercially important market for pharmaceuticals. The US system has unique features like the Hatch-Waxman Act for small molecules and the BPCIA for biologics, which intertwine the patent and regulatory systems. The litigation environment is robust and well-developed. A strong US portfolio is non-negotiable.

- The European Patent Office (EPO): The EPO offers a centralized examination process that can lead to a “bundle” of national patents in up to 40+ European countries. This is a highly efficient way to secure broad European coverage. However, after grant, the patent must be validated and maintained in each individual country of interest. The EPO is known for its rigorous examination standards, particularly regarding inventive step and added matter.

- The Japan Patent Office (JPO): Japan is another critical pharmaceutical market with a sophisticated patent system. The JPO has its own unique examination practices, particularly concerning claim scope and data requirements. Navigating the Japanese system successfully almost always requires experienced local counsel.

A core global strategy will almost always involve filing in these three jurisdictions. The process is often streamlined by first filing a single international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which provides a 30 or 31-month window to decide in which specific countries to pursue patent protection [5].

Strategic Considerations for Emerging Markets (China, India, Brazil)

Beyond the Trinity, the strategic importance of key emerging markets has grown exponentially. However, these jurisdictions come with their own unique challenges and opportunities.

- China: Now the second-largest pharmaceutical market in the world, China is an essential filing destination. Its patent system has matured rapidly, and its specialized IP courts are becoming more effective at enforcement. However, understanding local practices and data requirements is key.

- India: Often called the “pharmacy of the world” due to its powerful generics industry, India presents a complex landscape. Its patent law includes unique provisions like Section 3(d), which is designed to prevent “evergreening” by restricting patents on new forms of known substances unless they demonstrate significantly enhanced efficacy [6]. This makes securing secondary patents (like polymorph or new formulation patents) much more challenging than in the US or Europe. Deciding whether and what to file in India requires careful strategic calculation.

- Brazil: Another major market, Brazil’s patent system has historically been plagued by long delays, partly due to a “double-check” system involving its health regulatory agency, ANVISA. While reforms are underway, securing patents in Brazil can be a slow and complex process.

For these and other markets (e.g., Canada, South Korea, Australia, Mexico), the decision to file must be based on a careful analysis of market size, commercial strategy, the strength of the patent system, the cost of prosecution, and the likelihood of enforcement. An effective global strategy is a tailored strategy, not a rubber stamp. It focuses resources where they will generate the most value and protection for the commercial ambitions of the company.

Active Management and Curation: Pruning the Garden for Optimal Growth

A patent portfolio is not a monument to be built and then admired from afar. It’s a garden. It requires constant tending, watering, and, most importantly, pruning. A garden choked with weeds and unproductive plants will yield a poor harvest. Similarly, a patent portfolio cluttered with low-value, high-cost assets will drain resources and obscure the true strategic gems. Active, disciplined management is the process of curating this garden to ensure it produces the most valuable fruit.

The Portfolio Audit: A Necessary Health Check

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. The cornerstone of active portfolio management is the regular, systematic audit. This is not simply an accounting of what patents you own. It’s a deep, strategic review that assesses the health, alignment, and performance of every asset in the portfolio against the company’s current and future business objectives. An audit should be conducted at least annually, and more frequently if the company is undergoing significant strategic shifts, such as a merger or a major R&D pivot.

Establishing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for Patents

To move from a subjective “gut feeling” to an objective assessment, it’s crucial to establish clear KPIs for your patents and patent families. These KPIs will vary by company and strategy, but they typically fall into several key categories:

- Strategic Alignment:

- Product Linkage: Does this patent protect a current commercial product, a product in late-stage clinical development, or a key pipeline candidate? (High score) Or does it relate to a discontinued project? (Low score)

- Geographic Alignment: Is the patent’s geographic coverage aligned with our key markets and commercial plans? Are we paying maintenance fees in countries we have no intention of entering?

- Technology Relevance: Does the patent cover a core, strategic, or ancillary technology (as defined in our earlier framework)? Does it align with our current R&D focus?

- Legal and Competitive Strength:

- Patent Type & Scope: Is it a foundational CoM patent or a narrower secondary patent? Are the claims broad and difficult to design around?

- Enforceability: How likely is this patent to survive a validity challenge (e.g., an Inter Partes Review or IPR in the US)? Have we identified all relevant prior art?

- Competitive Impact: Does this patent block key competitors? Have we seen evidence of competitors trying to design around it? Is it cited frequently by other patents in the field (a potential indicator of importance)?

- Financial & Commercial Value:

- Revenue Protection: What is the estimated revenue protected by this patent family? (For commercial products).

- Licensing Potential: Does this patent have potential for out-licensing to generate revenue? Have we received any unsolicited inquiries?

- Cost of Maintenance: What is the annual cost of annuities/maintenance fees for this patent family? Is the cost justified by its strategic value?

By scoring each patent family against these (and other customized) KPIs, you can create a data-driven map of your portfolio, moving it from a simple list to a strategic grid.

The “Keep, License, or Abandon” Decision Matrix

The output of this KPI-driven audit is a clear categorization of your assets, which feeds directly into a decision matrix. This is where the strategic action happens. Each patent family can be placed into one of several buckets:

- Core / Retain & Defend: These are the crown jewels. They score highly on almost all KPIs. They protect your key revenue streams and strategic pipeline assets. The strategy here is simple: maintain these patents at all costs, in all relevant jurisdictions, and be prepared to defend them vigorously against any challenge.

- Strategic / Maintain & Monitor: These patents are valuable but perhaps not central to a current blockbuster. They might protect a mid-stage pipeline candidate, offer important flank protection for a core product, or cover a key technology platform. The strategy is to maintain them but to periodically re-evaluate their importance as the business evolves.

- High Potential / License or Partner: This is a crucial category for value creation. These patents may be technically strong but are not aligned with the company’s core commercial focus. For example, a company focused on oncology might have a patent for a cardiovascular application discovered serendipitously. Rather than letting this asset wither, the strategy should be to proactively seek a licensee or partner who is focused on cardiovascular disease. This turns a non-strategic asset into a new revenue stream.

- Low Value / Prune & Abandon: This is the most difficult category for many organizations, yet it is one of the most critical for efficient management. These are the patents that score poorly across the board. They may relate to abandoned R&D projects, cover markets the company will never enter, or have been superseded by newer, stronger IP. The strategy here must be disciplined abandonment.

Strategic Pruning: When Letting Go is the Smartest Move

The idea of willingly abandoning a patent can feel counterintuitive, even sacrilegious, to a culture built on innovation and protection. It can feel like admitting defeat. In reality, it is one of the most strategically astute actions a portfolio manager can take.

Calculating the True Cost of Maintaining a Weak Patent

The decision to prune becomes much easier when you quantify the true cost of holding onto a low-value asset. This isn’t just about the direct fees.

- Direct Costs: These are the most obvious. Every country’s patent office charges escalating annual fees (annuities) to keep a patent in force. For a large portfolio with filings in dozens of countries, these fees can run into the millions of dollars annually [7].

- Indirect Costs (The Hidden Drain): The hidden costs are often more significant. These include the time and attention of your valuable in-house IP professionals and outside counsel who have to manage the patent, track deadlines, and respond to communications. This is time and cognitive bandwidth that could be spent on high-value activities, like drafting a crucial new application or analyzing a competitor’s portfolio.

- Opportunity Cost: This is the most important and most overlooked cost. Every dollar and every hour spent maintaining a “zombie” patent (one that protects nothing of commercial value) is a dollar and an hour that cannot be invested in filing a new patent on a promising discovery from your R&D pipeline. It’s a direct trade-off.

By systematically pruning the portfolio, you are not shrinking your protection; you are concentrating your resources. You are making your fortress stronger by tearing down the crumbling, useless outer sheds and using the reclaimed stone and manpower to reinforce the main keep.

Reallocating Resources to High-Value Innovation

The ultimate goal of pruning is reallocation. The savings generated from abandoning a portfolio of low-value patents in non-strategic jurisdictions can be substantial. This “found money” can then be reinvested directly into the IP strategy in ways that create real value:

- Funding New Filings: Support the patenting of new innovations coming out of R&D.

- Expanding Geographic Coverage: File in additional strategic markets for your most important assets.

- Conducting FTO Analyses: Proactively clear the path for new projects by funding more thorough freedom-to-operate searches.

- Strengthening Defenses: Build a war chest for potential litigation or file for post-grant proceedings against a competitor’s threatening patent.

A company that actively prunes its portfolio demonstrates a high level of strategic maturity. It shows that it understands that IP is not an emotional collection of past glories but a forward-looking tool for driving business success. It’s about cultivating the garden for the future harvest, not just preserving a historical record of what was once planted.

Lifecycle Management: Extending Value Beyond the Core Patent Cliff

For a pharmaceutical company, the patent cliff is the fiscal equivalent of the Grand Canyon—a sudden, terrifying drop-off. The expiration of the core composition of matter (CoM) patent on a blockbuster drug can trigger a rapid and massive loss of revenue to generic competition. However, the savviest companies don’t simply wait for this day to arrive. They engage in proactive “lifecycle management” (LCM), a sophisticated strategy aimed at maximizing a drug’s value throughout its entire commercial life and mitigating the steepness of the eventual decline. This involves a combination of scientific innovation, regulatory strategy, and, critically, a forward-thinking, layered patenting approach.

The Controversial Art of “Evergreening”: Strategies and Ethical Lines

Lifecycle management is often associated with the term “evergreening,” a pejorative label used by critics to describe strategies they claim are used by innovator companies to illegitimately extend their patent monopolies. While some practices have certainly pushed legal and ethical boundaries, at its core, legitimate LCM is about patenting genuine, subsequent innovations that provide real benefits to patients. It’s not about extending the same patent; it’s about creating new patents on new inventions related to the original drug.

“A study of 100 best-selling drugs found that 78% had new patents added after they were first marketed, which on average extended their patent protection by nearly 7 years. More than 50% of the drugs were associated with at least one new clinical trial initiated after the drug was already on the market, often for a new indication or formulation.” — Cited in research by C. S. Kesselheim, et al., The Milbank Quarterly [8]

This statistic highlights that LCM is not a niche tactic but a central and widespread strategy in the industry. The key is to ensure that the follow-on patents are for genuine improvements and not just trivial tweaks designed to obstruct competition.

New Formulations, Delivery Systems, and Dosing Regimens

This is perhaps the most common and valuable area of LCM innovation. The first-generation version of a drug may not be the most optimal from a patient’s perspective. Subsequent research can lead to significant improvements that are both patentable and highly valuable.

- Example: From Multiple Daily Doses to One. Imagine a drug that initially requires patients to take a pill three times a day. This can be a significant burden, leading to poor adherence. The company’s scientists invest in R&D to develop a new extended-release (ER) formulation that only needs to be taken once a day. This is a real clinical benefit—it improves compliance and patient quality of life. This new ER formulation is a non-obvious invention and can be protected by a new patent. Even when the original CoM patent expires, generic companies can only market the three-times-a-day version. Patients and doctors, having grown accustomed to the convenience of the once-daily pill, are likely to stick with the branded ER version, thus preserving a significant portion of the brand’s revenue stream.

- Delivery Systems: Moving from an injectable drug to an oral pill, a transdermal patch, or an inhaler represents a major improvement in convenience and is a prime target for LCM patenting. These are not trivial changes; they require significant innovation in formulation science and biopharmaceutics.

Chiral Switches and Enantiomer Patents

Many small-molecule drugs are “chiral,” meaning they can exist in two mirror-image forms (enantiomers), much like a person’s left and right hands. Often, a drug is first developed and sold as a “racemate,” a 50/50 mixture of both enantiomers. However, it’s frequently the case that one enantiomer is responsible for the therapeutic effect, while the other is inactive or, in some cases, contributes to side effects.

A “chiral switch” is the process of developing a new drug product that contains only the single, active enantiomer (the “eutomer”). This can lead to a better product with an improved side-effect profile or a lower required dose. The isolated, single enantiomer can often be patented separately from the original racemic mixture, provided it was not explicitly disclosed previously and its separation and superior properties were not obvious. This was a popular and successful LCM strategy for many drugs, such as omeprazole (Prilosec) and its single-enantiomer successor, esomeprazole (Nexium) [9].

Combination Therapies and Their IP Implications

Another powerful LCM strategy is to combine the original drug with one or more other active ingredients to create a new fixed-dose combination (FDC) product. This is particularly common in areas like hypertension, diabetes, and infectious diseases (e.g., HIV), where treating the condition often requires a multi-drug cocktail.

- Clinical and Commercial Value: An FDC can dramatically improve patient adherence by reducing the “pill burden.” Taking one pill is far easier than taking two, three, or more. This clinical benefit can translate into significant commercial value.

- Patenting Strategy: The new combination itself can be patented. The claims would cover a composition comprising Drug A and Drug B. Even after the patents on Drug A and Drug B individually expire, a generic company cannot simply combine them into a single pill without infringing the FDC patent. This can create a new period of exclusivity for the more convenient combination product, preserving brand loyalty and revenue.

Leveraging Regulatory Exclusivities: A Parallel Path to Protection

It’s crucial to remember that patents are not the only form of exclusivity available. Regulatory agencies, like the FDA in the United States, grant their own forms of market exclusivity as incentives for conducting certain types of research. These regulatory exclusivities run in parallel with patent protection and can sometimes provide protection even when patents have expired or are not available. A savvy LCM strategy integrates both.

Understanding Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE), New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity, and Pediatric Exclusivity

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: In the US, a drug approved containing an active ingredient that has never before been approved by the FDA is granted five years of data exclusivity [10]. During this period, the FDA cannot accept an application for a generic version. This provides a baseline level of protection, though it is shorter than a typical patent term.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): To incentivize the development of drugs for rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US), the Orphan Drug Act provides seven years of market exclusivity for a drug approved for an orphan indication [11]. This exclusivity attaches to the approved use, meaning no other company can get approval for the same drug for the same rare disease for seven years, regardless of the patent status. A key LCM strategy is to investigate if a company’s existing drug could be effective in a rare disease, thereby gaining a valuable period of ODE.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: The FDA can grant an additional six months of marketing exclusivity if the drug’s sponsor conducts pediatric studies as requested by the agency. This six-month extension is incredibly valuable because it attaches to all existing patent and regulatory exclusivities for that drug [12]. For a blockbuster drug earning billions per year, that extra six months of monopoly protection can be worth hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars. Proactively planning for and conducting these studies is a cornerstone of modern LCM.

By skillfully weaving together a strategy of follow-on patenting for genuine innovations and maximizing the acquisition of regulatory exclusivities, companies can create a far more durable and valuable asset. This isn’t about improperly gaming the system; it’s about continuously innovating around a successful product and being rewarded with additional, legally sanctioned periods of protection for that new investment and the added clinical value it brings. It transforms the patent cliff from a sheer drop into a more manageable, extended slope.

Competitive Intelligence: The Eyes and Ears of Your Portfolio Strategy

In the strategic chess game of pharmaceutical IP, you can’t win by only looking at your own pieces. A successful patent portfolio strategy is not developed in a vacuum; it is forged in the crucible of the competitive landscape. Understanding what your rivals are doing, where they are going, and what threats or opportunities their actions create is not just a “nice to have”—it is an absolute necessity. Competitive intelligence (CI) is the discipline of gathering, analyzing, and acting upon this information. It serves as the eyes and ears of your portfolio management, enabling you to play offense, not just defense.

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Navigating the Patent Minefield

Before you invest hundreds of millions of dollars in developing a new drug, you need to know if you can actually sell it without being sued for patent infringement. This is the fundamental question that a Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis seeks to answer. An FTO analysis is a detailed investigation of the “live” patent landscape to assess the risk that your planned commercial product, process, or service might infringe on a third party’s valid patent rights. It is one of the most critical due diligence activities in pharmaceutical R&D.

When and How to Conduct an FTO Search

The timing of an FTO analysis is crucial.

- Too Early: If conducted too early, before your own product is well-defined, the search may be too broad and unfocused. Furthermore, many relevant competitor patents may not have even been published yet (patent applications are typically kept secret for the first 18 months after filing).

- Too Late: If conducted too late—say, just before launching Phase III trials—you might uncover a “blocking patent” that completely derails your project. At this stage, redesigning the product or trying to license the patent from a position of weakness can be prohibitively expensive or impossible.

Therefore, FTO is not a single event but a process. A preliminary FTO search should be conducted early in development to get a sense of the landscape. This should then be updated at key milestones: before committing to expensive toxicology studies, before starting clinical trials, and certainly before commercial launch.

The process itself involves:

- Defining the Search: Clearly outlining the key features of your product—the molecule’s structure, the formulation, the method of use, the manufacturing process.

- Searching Patent Databases: Conducting comprehensive searches of patent databases in all relevant jurisdictions. This is a highly specialized skill requiring expertise in search syntax and database architecture.

- Analyzing the Results: Sifting through the search results to identify the most relevant and potentially problematic patents.

- Legal Analysis: A patent attorney then analyzes these key patents to determine if they are valid and if your product would likely be found to infringe their claims.

From Risk Assessment to Strategic Design-Arounds

The output of an FTO analysis is not a simple “yes” or “no.” It’s a risk assessment. The patents identified are categorized based on the level of risk they pose (high, medium, low). For high-risk patents, the strategic response can take several forms:

- Licensing: If the patent is strong and infringement is likely, you can approach the patent holder to negotiate a license. This gives you permission to use their invention in exchange for payments (e.g., royalties).

- Designing Around: This is where FTO analysis becomes a powerful R&D tool. Armed with the knowledge of a competitor’s patent claims, your scientists can try to “design around” it. For example, if a competitor has a patent on a specific formulation, your team can work to develop a different formulation that achieves the same goal but does not fall within the scope of their claims.

- Invalidation: You may determine that the competitor’s patent is weak and could be invalidated. You can challenge its validity in court or through post-grant proceedings like an IPR. This is an aggressive and expensive option, but it can clear the path completely if successful.

- Waiting it Out: If the patent is nearing the end of its term, the most prudent strategy may simply be to wait for it to expire before launching your product.

A proactive FTO process doesn’t just prevent lawsuits; it informs R&D, drives innovation, and is a cornerstone of sound investment decisions.

Monitoring the Competitive Landscape: Staying Ahead of the Curve

Beyond the specific risk assessment of an FTO, a broader, ongoing CI program is essential for maintaining a strategic edge. You need a panoramic view of your competitors’ activities to anticipate their moves, identify trends, and spot opportunities.

Tracking Competitor Filings, Prosecutions, and Litigation

What should you be monitoring?

- New Patent Filings: What new technologies and drug candidates are your competitors patenting? This is a direct window into their R&D pipeline, often revealing their strategic direction years before they announce it publicly. Tracking their international filing strategy can also reveal their market priorities.

- Patent Prosecution: Following the back-and-forth between a competitor and the patent office (the “file wrapper”) can reveal critical information. You can see what prior art the examiner has cited, what arguments the competitor is making to get their claims allowed, and what claim scope they are likely to end up with. This can help you assess the strength and breadth of their future patents.

- Litigation and Post-Grant Challenges: Are your competitors suing or being sued? Who is challenging their patents in IPRs? The outcomes of these legal battles can dramatically shift the competitive landscape, either strengthening or weakening a rival’s IP position. Monitoring these events is crucial. For example, if a competitor’s key patent is invalidated, it might open up a new opportunity for you.

Using Advanced Analytics and Tools like DrugPatentWatch for Actionable Insights

Manually tracking all this information across multiple jurisdictions for multiple competitors is a herculean task. Fortunately, the field of IP analytics has made huge strides, and specialized tools and services are available to automate and enhance this process.

These tools can provide:

- Alerting Services: Automated alerts that notify you whenever a specific competitor files a new application, a patent is granted, or a litigation event occurs.

- Patent Landscaping: Advanced visualization tools that can create “patent maps” of a technology area, showing you who the key players are, what technologies are crowded, and where there might be “white space” for your own innovation.

- Data Aggregation: Sophisticated platforms can pull together disparate data points—patents, clinical trials, regulatory approvals, litigation—to create a holistic picture of a drug or a company. Services like DrugPatentWatch are specifically designed for the pharmaceutical industry, providing curated data and analysis on drug patents, related exclusivities, and litigation. Such specialized resources are invaluable because they distill vast amounts of complex information into actionable intelligence, helping you to connect the dots between a patent filing and a future market threat.

By investing in a robust CI program, you change the game. You’re no longer just reacting to a competitor’s lawsuit or a surprise product launch. You are anticipating their moves, proactively managing your own risks, and identifying strategic opportunities to strengthen your own portfolio and market position. In the intelligence war of pharma IP, knowledge isn’t just power—it’s profit.

Monetization and Value Extraction: Making Your Portfolio Pay Dividends

A well-constructed and managed patent portfolio is an asset of immense potential value. But potential value is not realized value. The final, and arguably most important, phase of portfolio management is actively extracting that value and converting it into tangible returns, whether in the form of direct revenue, strategic market position, or enhanced corporate worth. This goes far beyond simply protecting your own product sales; it’s about making the portfolio itself a dynamic, revenue-generating engine.

Strategic Licensing: From Revenue Generation to Market Access

Licensing is the primary mechanism for monetizing IP that you do not intend to commercialize yourself. A license is a legal agreement in which a patent owner (the licensor) grants another party (the licensee) the right to make, use, or sell the patented invention in exchange for compensation, typically in the form of upfront payments, milestone payments, and/or royalties on sales.

In-Licensing vs. Out-Licensing Strategies

Licensing is a two-way street, and a comprehensive IP strategy must consider both sides of the transaction.

- Out-Licensing: Turning Idle Assets into Cash. Most R&D-intensive companies generate more innovations than they can possibly develop and commercialize. These “ancillary” or “non-core” assets, which we identified during the portfolio audit, are perfect candidates for out-licensing.

- Example: A company specializing in oncology discovers a compound with promising activity for a neurological disorder. Instead of letting the patent sit on the shelf or trying to enter a new therapeutic area from scratch, they can license the compound to a company that already has expertise and a commercial presence in neurology. This creates a win-win: the oncology company generates revenue from a non-core asset, and the neurology company gains a new pipeline candidate without the cost of early-stage discovery.

- Key to Success: A proactive out-licensing program requires a dedicated effort to identify potential licensees, market the technology, and negotiate favorable terms. It’s not a passive activity.

- In-Licensing: Filling Gaps and Accelerating Growth. No company can invent everything itself. In-licensing is a critical strategy for filling gaps in your own R&D pipeline, acquiring new technologies, or gaining access to a drug that is complementary to your existing portfolio.

- Example: A mid-sized pharma company has a strong sales force in cardiology but a weak early-stage pipeline. They can accelerate their growth by in-licensing a promising cardiovascular drug from a small biotech that has great science but lacks the capital and infrastructure for late-stage development and commercialization.

- Due Diligence is Key: The success of in-licensing hinges on rigorous due diligence. Before signing a deal, you must conduct a deep analysis of the licensor’s patent portfolio. Are the patents valid and enforceable? Is there clear freedom-to-operate? What is the remaining patent term? A failure in IP due diligence can lead to licensing an asset that is worth far less than you paid for it.

Crafting Win-Win Licensing Agreements

The license agreement itself is a complex legal document that requires careful negotiation. Key terms to consider include:

- Scope of the License: Is it exclusive (only this licensee can practice the invention) or non-exclusive? Which geographic territories are covered? Which fields of use (e.g., for which diseases)?

- Financial Terms: What is the structure of the compensation? This can include an upfront fee, milestone payments tied to development or regulatory success, and a royalty rate on net sales.

- Diligence Obligations: The licensor will often insist on terms that require the licensee to use “commercially reasonable efforts” to develop and launch the product, ensuring the patent doesn’t get licensed and then shelved.

- IP Enforcement: Who has the right and responsibility to sue for infringement? Who pays for the litigation, and who controls it?

A well-crafted agreement aligns the interests of both parties and paves the way for a successful partnership.

The Role of IP in Mergers, Acquisitions, and Strategic Alliances

In the biopharmaceutical industry, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are a constant feature of the landscape. Large companies acquire smaller ones to access their innovation, and companies of all sizes form strategic alliances to share risk and combine complementary capabilities. In nearly every one of these transactions, the intellectual property portfolio is not just an important component—it is often the central asset driving the deal and its valuation.

IP Due Diligence: Uncovering Risks and Opportunities

When one company considers acquiring another, the acquiring company’s legal and IP teams will perform exhaustive IP due diligence. This is an even more intense version of the FTO analysis and portfolio audit we discussed earlier. The goal is to verify the seller’s claims about their IP and to uncover any hidden risks.

The diligence team will ask critical questions:

- Ownership: Does the target company actually own the IP free and clear? Are there any co-owners? Are all inventors correctly listed and have they assigned their rights to the company? A flaw in the chain of title can be a fatal deal-killer.

- Validity and Enforceability: What is the likelihood that the key patents could be invalidated in a legal challenge? Are there any known prior art references that were not disclosed to the patent office?

- Scope and Coverage: Do the patent claims actually cover the commercial product? Is the geographic coverage sufficient?

- Third-Party Obligations: Are there any existing licenses, collaborations, or other agreements that encumber the IP? For example, does a university still have rights to the invention?

Uncovering a major IP problem during due diligence can lead to a significant reduction in the purchase price, or it can cause the acquirer to walk away from the deal entirely.

Valuing an IP Portfolio in an M&A Context

So, how much is a patent portfolio actually worth? This is one of the most complex questions in corporate finance. There is no single, simple formula. Valuation experts typically use a combination of three approaches:

- The Cost Approach: This method values the IP based on the cost to create it (e.g., R&D expenses) or the cost to replace it. This is often seen as a baseline or floor value, as it doesn’t capture the future economic potential.

- The Market Approach: This method looks for “comparable transactions.” What have other companies paid for similar IP portfolios in similar deals? The challenge is finding truly comparable transactions, as every IP portfolio and every deal is unique.

- The Income Approach: This is generally the most influential method for pharma IP. It seeks to calculate the present value of the future economic income that the IP is expected to generate. This involves complex financial modeling, including forecasting future sales of the protected product, estimating profit margins, and then “discounting” those future cash flows back to a present-day value. The patent term and the strength of the portfolio are critical inputs into this model, as they define the duration and security of those cash flows.

Ultimately, a strong, well-managed patent portfolio is a powerful driver of corporate value. It not only protects revenue streams but also creates new ones through licensing and serves as the primary currency in the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical M&A. Extracting this value requires a proactive, strategic, and commercially-minded approach to IP management.

Enforcement and Defense: Protecting Your Crown Jewels in the Arena

A patent grants you the right to exclude others from practicing your invention. However, this right is not self-enforcing. The patent office does not police the market for infringers. If a competitor chooses to ignore your patent and launch a competing product, your only recourse is to assert your rights in the legal arena. Patent litigation is the ultimate test of a portfolio’s strength. It is an incredibly expensive, complex, and high-stakes endeavor, but it is the necessary mechanism for defending your market exclusivity and the value it represents. A portfolio management strategy that does not prepare for the possibility of litigation is incomplete.

The High-Stakes World of Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation

Pharmaceutical patent litigation is a unique and specialized field of law, largely governed by landmark legislation that links the patent system directly to the drug regulatory approval process. This creates a highly structured and predictable, yet intensely adversarial, framework for resolving patent disputes.

The Hatch-Waxman Act and ANDA Litigation: A Specialized Battlefield

For small-molecule drugs, the landscape is dominated by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act [13]. This act brilliantly balanced two competing interests: it created the modern generic drug industry by streamlining the approval process for generic drugs, while also providing new incentives and protections for innovator companies.

The core of the system is the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). A generic company seeking to market a version of a branded drug doesn’t need to conduct its own costly clinical trials; it only needs to show that its product is bioequivalent to the innovator’s product.

However, as part of its ANDA, the generic filer must make a certification regarding each patent that the innovator has listed in the FDA’s “Orange Book” as covering the branded drug. The most common and consequential certification is a “Paragraph IV” (PIV) certification, in which the generic company declares that it believes the innovator’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product [14].

Filing a PIV certification is considered a technical act of patent infringement and is the starting gun for litigation. The innovator has 45 days to sue the ANDA filer for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA is automatically barred from approving the ANDA for up to 30 months, or until the court case is resolved, whichever comes first. This “30-month stay” provides a crucial window for the patent dispute to be litigated before a generic product can enter the market. The result is a highly focused, high-stakes form of litigation that is a defining feature of the pharmaceutical industry.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA): The “Patent Dance”

For biologics—large, complex molecules like antibodies produced in living systems—the framework is the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA) [15]. It created an abbreviated pathway for the approval of “biosimilars,” which are highly similar to, with no clinically meaningful differences from, an existing approved biologic.

The BPCIA has its own unique pre-litigation process for identifying and resolving patent disputes, which has been nicknamed the “patent dance.” It is a complex, multi-step exchange of information between the biosimilar applicant and the innovator company, designed to identify the relevant patents and narrow the scope of potential litigation before a lawsuit is even filed. The steps involve the applicant providing its regulatory application and manufacturing information to the innovator, followed by the parties exchanging lists of patents they believe could be infringed. While the process is intricate and has had its own legal battles over its interpretation, its goal is to create a more orderly framework for resolving the complex patent issues surrounding these highly valuable products.

Building an Ironclad Litigation Strategy

Facing the prospect of Hatch-Waxman or BPCIA litigation, an innovator company must have a clear and robust strategy. This isn’t just about hiring good lawyers; it’s about making shrewd business decisions under immense pressure.

Choosing Your Battles: When to Litigate, When to Settle

Not every PIV challenge needs to result in a full-blown trial. The decision to litigate or settle is a complex one, based on a cold, hard assessment of several factors:

- Strength of the Patent(s): How likely is your patent to be upheld as valid and infringed? A strong CoM patent with a clear line of sight to infringement warrants a vigorous defense. A weaker secondary patent (e.g., a method-of-use patent with ambiguous prior art) might be a better candidate for settlement.

- Cost of Litigation: Patent litigation is extraordinarily expensive, often running into the tens of millions of dollars. These costs must be weighed against the potential loss of revenue if the generic enters the market.

- Risk of Loss: Litigation is inherently uncertain. Even with a strong case, there is always a risk of losing in court. A loss can mean the immediate entry of multiple generics and the complete erosion of a brand’s revenue.

- Settlement Terms: A settlement can provide certainty. A common form of settlement is a “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” agreement, where the innovator pays the generic challenger to drop its patent challenge and agree not to launch its product until a certain date in the future. These agreements are under intense scrutiny from antitrust regulators like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) but can be a legal and pro-competitive way to resolve a dispute if structured properly [16].

The Role of Post-Grant Proceedings (IPR, PGR)

Since the passage of the America Invents Act (AIA) in 2011, another battlefield has emerged: post-grant proceedings at the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The most common of these is the Inter Partes Review (IPR). An IPR allows a third party (like a generic company) to challenge the validity of a granted patent directly within the patent office, on the grounds that it was not novel or was obvious in light of prior art patents and printed publications.

- A Faster, Cheaper Alternative: For challengers, an IPR is often much faster and less expensive than challenging a patent in federal court.

- A Parallel Threat: For patent owners, an IPR represents a significant parallel threat. A company can find itself fighting a patent’s validity in both district court and at the PTAB simultaneously.

- Strategic Implications: The availability of IPRs has changed litigation strategy. Innovators must now build portfolios that can withstand scrutiny not just from a judge and jury, but also from the technically sophisticated administrative patent judges at the PTAB. Conversely, an innovator can use or threaten to use an IPR to challenge a competitor’s blocking patent as part of its FTO strategy.

In conclusion, enforcement and defense are the sharp end of the IP spear. It is where the theoretical value of the portfolio is put to the ultimate test. A proactive portfolio management strategy anticipates these conflicts, builds patents that are “litigation-grade,” and integrates sophisticated legal and business judgment to navigate these high-stakes disputes, preserving the market exclusivity that is the lifeblood of pharmaceutical innovation.

The Human Element: Building a World-Class IP Management Team

We have discussed strategies, processes, and legal frameworks, but none of these can be executed effectively without the right people and the right organizational culture. A patent portfolio, for all its legal and technical complexity, is ultimately a human endeavor. The quality of your portfolio is a direct reflection of the quality of the team that builds and manages it, and the culture of IP awareness that permeates the entire organization. Building a world-class IP function is not just about hiring smart lawyers; it’s about fostering integration, collaboration, and a shared understanding of IP’s strategic value.

Cultivating an IP-Savvy Culture Across the Organization

The most effective IP strategy is one that is not confined to the IP department. It must be woven into the fabric of the company’s daily operations, from the scientist at the lab bench to the executive in the boardroom. This requires a conscious and sustained effort to build an “IP-savvy” culture.

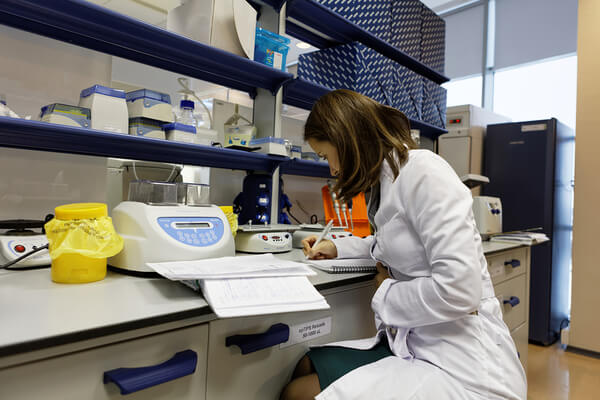

- Training and Education: Regular training sessions should be mandatory for all R&D personnel. Scientists don’t need to be patent lawyers, but they do need to understand the fundamentals: What is patentable? What is prior art? Why is keeping a detailed lab notebook so critical? How do you avoid inadvertently disclosing an invention publicly before a patent is filed (a mistake that can forfeit patent rights in many countries)? When they understand the “why” behind the rules, they become active partners in the invention capture process.

- Incentivizing Invention: Companies should have clear and motivating incentive programs that reward employees for inventions that lead to filed patent applications or granted patents. This can include financial bonuses, public recognition, or other awards. This signals that the company values innovation and the IP that protects it. It encourages scientists to think not just about scientific discovery, but about inventive problem-solving.

- Breaking Down Silos: The cultural goal is to eliminate the “us vs. them” mentality that can sometimes exist between R&D and legal. This is achieved by embedding IP professionals with R&D teams, creating invention review committees with cross-functional membership, and fostering open lines of communication. When the scientist sees the patent attorney as a collaborative partner helping to protect their work, the quality of invention disclosures skyrockets.

- Leadership Buy-in: Culture starts at the top. When the CEO, CSO, and other C-suite leaders consistently talk about the importance of IP in town halls, investor calls, and internal communications, it sends a powerful message throughout the organization. When IP metrics are included in corporate dashboards alongside sales and R&D milestones, it reinforces IP’s status as a core business asset.

The Modern IP Team: Integrating Legal, Scientific, and Business Acumen

The days of the patent attorney as a solitary legal technician are over. A modern, world-class pharmaceutical IP team is a multidisciplinary powerhouse, blending a unique combination of skills to navigate the complex intersection of science, law, and commerce.

The ideal team composition includes individuals with:

- Deep Scientific Expertise: Your patent professionals must be able to speak the language of your scientists. A patent attorney with a Ph.D. in organic chemistry will be far more effective at drafting claims for a new small molecule and discussing the invention with the chemists than a generalist lawyer. The team should have technical expertise that mirrors the company’s R&D focus areas (e.g., immunology, oncology, molecular biology).

- Sophisticated Legal Knowledge: This is the baseline requirement. The team must have a deep and current understanding of patent law and procedure in key jurisdictions around the world (US, EPO, China, etc.). They need expertise not just in patent prosecution but also in litigation, licensing, and transactional due diligence.

- Sharp Business Acumen: This is what separates a good IP team from a great one. The team members must understand the company’s business model, its commercial strategy, the competitive landscape, and the financial drivers of the industry. They need to be able to answer not just “Can we get a patent?” but “Should we get a patent? And if so, where, and why?” They must be able to translate legal risk into business risk and communicate it effectively to non-lawyers.

- Data and Analytics Skills: As we’ve discussed, modern portfolio management is increasingly data-driven. The team needs members who are comfortable with patent search databases, analytics software, and competitive intelligence tools. They need to be able to extract insights from data, not just collect it. This may involve dedicated patent analysts or informaticians working alongside the attorneys.

Building this team often involves a hybrid model, combining a strong in-house core of strategic leaders with a network of specialized outside counsel. The in-house team sets the strategy and manages the portfolio, while outside law firms can provide deep jurisdictional expertise (e.g., a top litigation firm for a major lawsuit) or handle the high-volume work of patent prosecution, all under the strategic direction of the internal team.

Ultimately, the human element is the engine of the entire system. A company can have the best technology in the world, but without a culture that values IP and a skilled, integrated team to manage it, that value will never be fully realized or protected.

The Future of Pharma IP: Navigating New Frontiers

The world of pharmaceutical innovation is in a constant state of flux, and the intellectual property strategies that protect it must evolve in lockstep. The best practices of today are the baseline for tomorrow. Looking ahead, several powerful trends are poised to reshape the landscape of drug patent portfolio management. Companies that anticipate and adapt to these changes will seize a significant competitive advantage, while those that cling to old models risk being left behind.

The Impact of AI and Machine Learning on Patent Strategy

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are no longer science fiction; they are rapidly becoming practical tools that can augment and accelerate nearly every aspect of patent portfolio management.