Introduction: Beyond the Hype – Unpacking the True Value of Biosimilars

Welcome to the forefront of a seismic shift in the pharmaceutical landscape. For decades, the industry has been dominated by the blockbuster model, where innovative, patent-protected drugs generate billions in revenue. At the apex of this model sit biologic medicines—complex, large-molecule drugs derived from living organisms that have revolutionized the treatment of diseases from cancer to rheumatoid arthritis. But the very exclusivity that fueled their development also created a crisis of affordability and access. Now, the patent cliffs for these titans of therapy are crumbling, and a new class of contender has entered the ring: the biosimilar.

But what does this new era truly mean for global health? The promise is tantalizing: near-identical therapeutic efficacy at a significantly lower cost, potentially saving healthcare systems billions and expanding patient access to life-changing treatments. However, the reality is far more nuanced, a complex tapestry woven from threads of regulatory science, market economics, physician psychology, and national healthcare policy. The cost-effectiveness of biosimilars is not a universal constant; it’s a variable, dramatically influenced by the ecosystem in which it is introduced.

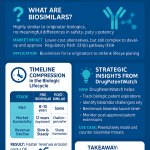

The Promise and the Premise: What Are Biosimilars, Really?

Before we dive into the economic labyrinth, let’s be crystal clear about what we’re discussing. A biosimilar is not a generic drug. While a generic is a perfect, identical chemical copy of a small-molecule drug (like aspirin or atorvastatin), a biosimilar is a highly similar, but not identical, version of a large, complex biologic medicine.

Think of it this way: a small-molecule drug is like a bicycle. It’s relatively simple to manufacture, and building an identical copy is straightforward. A biologic, on the other hand, is like a state-of-the-art jet engine. It’s produced in living cells, a process with inherent, microscopic variability. You can build another jet engine using the same blueprints and materials, and it will perform identically, but it will never be the exact same physical object down to the last molecule. Regulators, therefore, demand a far more rigorous “totality-of-the-evidence” approach for biosimilar approval, requiring extensive analytical, non-clinical, and clinical data to demonstrate that there are no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety, purity, and potency compared to the reference originator biologic [1]. This scientific rigor is the bedrock upon which the entire biosimilar value proposition is built.

The Economic Imperative: Why Cost-Effectiveness is the Ultimate Benchmark

With healthcare budgets strained to their breaking point worldwide, the arrival of biosimilars feels like a godsend. The potential for savings is staggering. Yet, simply having a lower-priced alternative on the market does not automatically translate to system-wide cost-effectiveness. True cost-effectiveness is a measure of health outcomes achieved per dollar spent. It’s the synthesis of price reduction, market uptake, patient outcomes, and the broader economic impact on the healthcare system.

Are the savings generated by a 30% discount on a biosimilar offset by low physician adoption? Does a “winner-takes-all” tender system that achieves an 80% discount create supply chain vulnerabilities that could ultimately harm patients and increase costs? How do we account for the value of increased access—the patients who can now receive treatment who previously could not? These are the questions that define the real-world value of biosimilars. Answering them requires us to look beyond the sticker price and analyze the intricate machinery of different healthcare systems.

A Global Patchwork: Setting the Stage for Diverse Healthcare Systems

The journey of a biosimilar from regulatory approval to a patient’s treatment plan is a vastly different experience in London, Los Angeles, or Seoul. We will explore this global patchwork in detail, examining how distinct healthcare models—from the centralized, single-payer systems of Europe to the fragmented, multi-payer labyrinth of the United States—create unique incentives and barriers.

We will dissect the policies, analyze the market dynamics, and unpack the case studies that reveal why one country might achieve near-total conversion to a biosimilar within months, while another struggles to reach double-digit market share after years. This deep dive is more than an academic exercise; for pharmaceutical executives, market access strategists, and healthcare payers, understanding these differences is the key to unlocking the full potential of the biosimilar revolution and turning data into a decisive competitive advantage.

The Foundation: Understanding Biologics, Patents, and the Birth of Biosimilars

To fully grasp the economic and strategic implications of biosimilars, we must first appreciate the world they are disrupting. This is a story of scientific breakthroughs, intellectual property, and the regulatory pathways forged to balance innovation with access.

The Age of Biologics: A Paradigm Shift in Medicine

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed a transformation in drug development. We moved beyond synthesizing simple chemicals in a lab to harnessing the power of biotechnology. The first recombinant human insulin, approved in 1982, was a landmark achievement, heralding the age of biologics [2]. These therapies—including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), fusion proteins, and therapeutic enzymes—are incredibly powerful and specific. They can target precise cellular pathways implicated in complex diseases like cancer, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn’s disease, offering hope where little existed before.

This specificity and complexity, however, come at a staggering cost. The research and development process for a new biologic can easily exceed $2 billion and take over a decade [3]. The manufacturing process is equally daunting, requiring sophisticated bioreactors, living cell lines, and meticulous purification processes. This high barrier to entry and immense upfront investment is the primary justification for the high prices of originator biologics, which can often run into tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient per year.

The Patent Cliff as a Springboard: How Exclusivity Expiration Fuels Innovation

The pharmaceutical business model hinges on intellectual property, primarily patents, which grant a period of market exclusivity to the innovator. During this period, the originator company can recoup its R&D investment and generate profit without direct competition. However, this exclusivity is finite. The moment it expires is known as the “patent cliff,” a term that strikes fear into the hearts of originator brand managers but represents a massive opportunity for others.

For biosimilar developers, the patent cliff is not an end but a beginning. It’s the starting gun for a race to market. However, navigating this landscape is fraught with complexity. An originator biologic is often protected not by a single patent, but by a “patent thicket”—a dense web of dozens or even hundreds of patents covering the molecule, manufacturing processes, formulations, and methods of use [4]. Untangling this thicket to find a clear path to market is a monumental legal and scientific challenge.

The Role of Services like DrugPatentWatch in Strategic Planning

This is where strategic intelligence becomes paramount. For a company planning to invest hundreds of millions in developing a biosimilar, knowing the precise expiration dates of key patents is not just helpful; it’s fundamental to the entire business case. They can’t afford to guess. This critical need has given rise to specialized business intelligence services. For instance, platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide comprehensive databases and analytics on drug patents, regulatory exclusivities, and litigation.

A biosimilar developer uses such a service to identify the most commercially attractive biologic targets nearing the end of their lifecycle. They analyze the patent thicket to devise a “design-around” strategy or to prepare for “at-risk” launches, where they challenge the validity of existing patents. For these companies, data on patent expiration is the foundational layer upon which market entry strategies, R&D timelines, and financial projections are built. It transforms the patent cliff from a simple date on a calendar into a strategic, data-driven springboard for competition.

The Intricacies of “Similarity”: The Scientific and Regulatory Hurdles

The pathway to biosimilar approval was a major regulatory challenge. How could regulators be sure a “similar” product was safe and effective without demanding a full suite of duplicative clinical trials, which would drive up costs and defeat the purpose?

The solution, pioneered by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2005 and later adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, is the concept of “totality of the evidence” [5]. This principle places immense emphasis on analytical and structural characterization.

Developers use a battery of advanced techniques—like mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance—to create a detailed fingerprint of the originator biologic. They must then demonstrate, with exhaustive data, that their biosimilar has a matching fingerprint. This analytical foundation is so crucial that if a high degree of similarity is proven here, the need for extensive clinical trials is reduced. The goal is not to re-prove the drug works, but to demonstrate that the biosimilar is so structurally and functionally similar to the well-understood originator that it will behave in the same way in patients. This elegant, science-led approach is what makes lower-cost biosimilars possible, but it is also a formidable scientific and financial barrier, ensuring only serious, well-capitalized players can enter the market.

Frameworks for Analysis: How Do We Measure Cost-Effectiveness?

When a health system decides whether to adopt and promote a new biosimilar, it isn’t just asking, “Is it cheaper?” It’s asking a much more sophisticated question: “Does this product deliver value for money?” To answer this, payers and health technology assessment (HTA) bodies around the world rely on a specialized set of economic tools. Understanding these frameworks is essential to seeing the world through a payer’s eyes.

The Health Economist’s Toolkit: ICERs, QALYs, and Beyond

The gold standard in many health systems for evaluating a new therapy is cost-utility analysis, which seeks to measure the cost of achieving a better quality and quantity of life. Two key concepts underpin this entire field: the ICER and the QALY.

Defining the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER)

The Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) is the central metric. It’s calculated as the difference in cost between two interventions (e.g., an originator biologic and its new biosimilar) divided by the difference in their health effects [6].

ICER=EffectivenessNew−EffectivenessStandardCostNew−CostStandard

For biosimilars, this formula gets interesting. Because regulatory approval requires that there be “no clinically meaningful differences” in effectiveness, the denominator of this equation (Effectiveness_New – Effectiveness_Standard) is theoretically zero. When this happens, the analysis shifts from cost-effectiveness to cost-minimization. The assumption is that the outcomes are the same, so the decision should be based purely on which option costs less. This simplifies the HTA review process for biosimilars in many countries, making price the primary lever of competition.

The Quality-Adjusted Life-Year (QALY) as a Universal Currency

But what is that “effectiveness” measured in? Often, it’s the Quality-Adjusted Life-Year (QALY). The QALY is a brilliant but controversial attempt to create a universal currency for health outcomes. It combines quantity of life (how many years a treatment adds) with quality of life (a score from 0, for death, to 1, for perfect health) [7]. For example, a treatment that adds four years of life at a quality score of 0.5 (e.g., living with a debilitating chronic condition) would generate 2 QALYs (4 years x 0.5 quality).

Health systems often have an implicit or explicit “willingness-to-pay” threshold for a QALY. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) generally considers interventions that cost £20,000-£30,000 per QALY gained to be cost-effective [8]. For biosimilars, since the QALYs gained are assumed to be identical to the originator, any price reduction immediately improves the cost-per-QALY calculation for the entire drug class, making the treatment more affordable for the system and freeing up resources.

Budget Impact Analysis (BIA): The Payer’s Perspective

While QALYs and ICERs tell a story about value, finance ministers and hospital CFOs need to know something much more pragmatic: “How will this affect my budget next year?” This is where the Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) comes in.

A BIA is a financial forecast. It doesn’t assess value, but rather affordability [9]. It takes the HTA’s recommendations and models their real-world financial consequences. A BIA for a new biosimilar would estimate:

- The size of the eligible patient population.

- The current cost of treating them with the originator biologic.

- The expected list price and negotiated price of the new biosimilar.

- The projected market uptake rate of the biosimilar over a 3-5 year period.

- The total potential savings for the healthcare budget.

For a payer, a compelling BIA is often more persuasive than a complex cost-effectiveness model. It translates the abstract concept of “value” into the concrete language of dollars, pounds, or euros saved. Successful biosimilar launches are almost always supported by a BIA that demonstrates substantial, tangible savings for the health system.

The Limitations of Traditional Models in the Biosimilar Context

While these tools are powerful, they have limitations when applied to the dynamic biosimilar market. Traditional HTA is often a static, one-time assessment of a single product. The biosimilar market, however, is about competition and system dynamics.

- Multi-competitor markets: A classic ICER calculation compares one new drug to the standard of care. But what happens when a second, third, and fourth biosimilar enter the market, each with a different price? The cost-effectiveness landscape becomes a moving target.

- The value of competition: Traditional models struggle to capture the broader, long-term value of a competitive market. The entry of the first biosimilar doesn’t just offer savings from that one product; it puts downward price pressure on the originator and all future entrants, creating a ripple effect of savings. This “price erosion” effect is a core benefit but is hard to quantify in a standard QALY model.

- Expanding access: A BIA might calculate savings based on the current patient population. But a major benefit of biosimilars is that their lower cost can expand the market, allowing patients who were previously denied treatment due to cost constraints to gain access. This expansion increases budget impact but also generates significant societal and health value, a trade-off that simple models can miss.

Recognizing these limitations is key. The true cost-effectiveness of biosimilars is not just about the savings on a per-patient basis, but about how their introduction reshapes the entire market and enables health systems to treat more patients more sustainably.

A Tale of Two Systems: Single-Payer vs. Multi-Payer Healthcare Models

Nowhere are the divergent fortunes of biosimilars more apparent than when comparing single-payer and multi-payer healthcare systems. The fundamental structure of how healthcare is financed and delivered creates profoundly different incentives for every stakeholder, from the manufacturer to the physician to the patient.

The Single-Payer Advantage: Centralized Negotiation and Rapid Uptake (e.g., UK’s NHS, Canada)

In a single-payer system, the government (or a government-affiliated body) is the dominant, and often sole, purchaser of healthcare services and products for the entire population. This concentration of purchasing power gives it immense leverage in price negotiations and the ability to implement national policies with sweeping effect.

This structure is, in theory, the ideal breeding ground for biosimilar success. The single payer has a direct, unassailable incentive to reduce costs, as every dollar saved on medicines can be reallocated to other healthcare priorities, like hiring more nurses or reducing surgical wait times. They can act decisively to drive biosimilar adoption.

Case Study: The NHS’s Aggressive Biosimilar Strategy for Adalimumab

Perhaps the most famous biosimilar success story comes from the UK’s National Health Service (NHS). Adalimumab (brand name Humira), an anti-inflammatory biologic, was the world’s best-selling drug for years, with UK expenditures reaching over £400 million annually [10]. When its patent expired in Europe in late 2018, NHS England executed a masterclass in procurement and implementation.

- Centralized Procurement: Instead of letting individual hospitals negotiate, NHS England ran a nationwide, online reverse auction. Multiple biosimilar manufacturers and the originator company bid against each other, driving the price down in real-time.

- Massive Savings: The result was breathtaking. The NHS secured the drug—from four different biosimilar manufacturers and the originator, ensuring supply diversity—at a discount of roughly 75% off the original list price [11].

- Mandated Uptake: Critically, the NHS didn’t just hope for uptake; it drove it. The “Best Value Biologic” program provided clear guidance to regional trusts. Physicians were strongly encouraged to switch existing patients and start all new patients on the most cost-effective biosimilar. Within just one year, biosimilar versions of adalimumab had captured over 80% of the market volume.

The adalimumab story illustrates the power of a single-payer system when it acts with strategic intent. The savings were not just theoretical; they were immediate and massive, estimated at over £100 million in the first year alone, freeing up funds to treat thousands of additional patients [10].

Challenges in Single-Payer Systems: Formulary Restrictions and Physician Autonomy

However, the single-payer model is not without its own challenges. The same centralized power that can drive rapid uptake can also lead to rigidity.

- Formulary Lock-out: In some “winner-takes-all” tender systems, only the lowest-bidding biosimilar is placed on the national formulary. While this maximizes immediate savings, it can create a monopoly for the winning bidder, stifle long-term price competition, and raise concerns about supply chain security if that single manufacturer encounters problems.

- Physician Pushback: While the NHS model was largely collaborative, top-down mandates can sometimes clash with the principle of physician autonomy. If doctors feel forced to switch patients for purely financial reasons without adequate clinical support or communication, it can breed resentment and undermine confidence in biosimilars.

The Multi-Payer Maze: Fragmentation and Market Dynamics in the U.S.

If the UK’s NHS is a battleship, capable of turning decisively, the U.S. healthcare system is a vast, chaotic flotilla of thousands of individual boats, all navigating with different maps and motivations. The U.S. has a multi-payer system, a patchwork of private insurance companies, government programs (Medicare, Medicaid), and employers, all making their own coverage and reimbursement decisions.

This fragmentation creates a vastly more complex and challenging environment for biosimilar adoption. There is no single entity to negotiate prices or mandate uptake for the entire population. Instead, a biosimilar’s success depends on navigating a convoluted web of intermediaries and overcoming perverse financial incentives.

The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and Rebate Walls

Central to the U.S. puzzle are Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). PBMs are third-party administrators who manage prescription drug benefits on behalf of insurance plans. They negotiate with drug manufacturers to secure rebates—essentially, after-the-fact discounts—on drugs in exchange for preferential placement on their formularies (the list of covered drugs).

This system creates a significant obstacle for biosimilars known as the “rebate wall” [12]. Here’s how it works:

- An originator company offers a large rebate to a PBM on its high-priced biologic.

- This rebate might be “bundled” across the manufacturer’s entire portfolio of drugs, or contingent on the PBM giving the originator biologic a high market share (e.g., 90%).

- A new biosimilar enters with a lower list price (say, 30% less). However, the net price of the originator, after the large rebate, might be very close to, or even lower than, the biosimilar’s price.

- The PBM is now disincentivized to favor the biosimilar. If it promotes the biosimilar and the originator’s market share drops, it could lose the massive rebate not just on that drug, but potentially across other drugs from that manufacturer, leading to a net financial loss for the PBM.

This dynamic means a lower-priced biosimilar can be effectively locked out of the market. The PBM, the insurer, and even the physician (whose prescribing choices are guided by the formulary) have a financial incentive to stick with the higher-list-price originator product.

“The U.S. has left billions of dollars in potential savings on the table due to sluggish biosimilar uptake. A 2022 analysis estimated that from 2015 to 2020, if biosimilar prices and market shares in the U.S. had matched those in Europe, the U.S. healthcare system could have saved an additional $20 billion on just seven key biologics.”— Adapted from findings by the Association for Accessible Medicines [13]

Case Study: The Slow Burn of Infliximab Biosimilars in the United States

The story of infliximab (brand name Remicade) is the U.S. counterpoint to the UK’s adalimumab success. The first infliximab biosimilar, Inflectra, launched in the U.S. in late 2016 at a 15% discount to Remicade’s list price [14]. In a single-payer system, this would have triggered a rapid shift.

In the U.S., however, uptake was glacial. The originator company, Johnson & Johnson, aggressively used its contracting and rebating strategies to protect Remicade’s market share. Many PBMs and insurers kept Remicade as the preferred agent because the post-rebate net price was competitive, and the financial incentives were aligned to maintain the status quo. Years after launch, multiple infliximab biosimilars were on the market, yet the originator still commanded a majority of the market share [15].

The result? The U.S. healthcare system—and the patients and employers who fund it—missed out on billions in potential savings. This case study starkly illustrates how market structure and intermediary incentives can completely override the simple logic of “a cheaper product should win.”

European Perspectives: A Continent of Contrasts

While we often speak of a “European model,” the reality is a fascinating mosaic of different national and regional approaches to biosimilar policy. Europe, as the first major region to establish a biosimilar pathway, has become a living laboratory for cost-effectiveness strategies. Examining the different approaches within the EU provides invaluable lessons for the rest of the world.

The Nordic Model: Tenders, Tenders, Tenders (e.g., Norway, Denmark)

The Nordic countries, particularly Norway and Denmark, have adopted one of the most aggressive and economically potent approaches to biosimilar adoption: the national tender. It’s a high-stakes game that produces dramatic results.

In this model, the national health authority invites all suppliers—both originator and biosimilar manufacturers—to submit a confidential bid to supply the market for a specific biologic for a set period (usually one year). The company that offers the lowest price wins the tender and becomes the exclusive or highly preferred supplier for the entire country [16].

The effects are twofold:

- Massive Price Reductions: The “winner-takes-all” nature of the tender creates ferocious price competition. It’s not uncommon to see discounts of 80-90% or even more compared to the pre-tender originator price. Norway became famous for this, achieving some of the lowest biologic drug prices in the world.

- Forced, Rapid Uptake: Once the tender is awarded, physicians are expected to prescribe the winning product to all new patients and, in many cases, to systematically switch stable existing patients from the originator. This leads to near-instantaneous uptake, with the winning biosimilar often capturing over 95% of the market volume within months.

From a pure cost-minimization perspective, this model is spectacularly effective. However, it’s not without its critics and risks. The focus on a single supplier can lead to supply chain vulnerabilities. If the winning manufacturer faces production issues, an entire nation’s supply of a critical medicine could be jeopardized. Furthermore, it can be a brutal market for manufacturers; companies invest millions to develop a biosimilar only to lose the tender and get zero market access for a year, creating significant commercial uncertainty.

Germany’s Prescribing Quotas and Physician Incentives

Germany, Europe’s largest pharmaceutical market, takes a different, more decentralized approach. Instead of a single national tender, Germany uses a system of regional prescribing quotas and financial incentives to steer physician behavior [17].

Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) funds, which cover the vast majority of the population, negotiate with regional physician associations to set biosimilar prescription targets. For example, a region might be tasked with ensuring that at least 50% of all adalimumab prescriptions are for a biosimilar version.

To encourage compliance, the system uses a combination of “carrots and sticks”:

- Information and Education: Physicians receive regular feedback on their prescribing patterns compared to their peers.

- Financial Incentives: While direct payments for prescribing biosimilars are generally frowned upon, the overall pharmaceutical budget for a physician’s practice is monitored. Consistently prescribing expensive originators when cost-effective biosimilars are available can lead to budget audits and, in some cases, financial penalties.

- “Aut Idem” (Or the Same): German pharmacists are often allowed and encouraged to substitute a prescribed originator biologic with a cost-effective biosimilar, provided it’s on a pre-approved interchangeability list, further driving uptake at the point of dispensing.

This “soft power” approach respects physician autonomy more than a hard mandate but has also proven highly effective. Germany has consistently achieved high biosimilar uptake rates across multiple therapeutic areas, demonstrating that a combination of clear targets, peer-to-peer feedback, and budgetary responsibility can be a powerful driver of cost-effective prescribing.

France and Italy: Balancing Regional Autonomy with National Goals

France and Italy represent a hybrid model, characterized by a tension between centralized national HTA decisions and decentralized, regional purchasing and implementation.

In both countries, a national body assesses the clinical and economic value of a new biosimilar. However, the actual procurement often happens at the regional or even hospital level. This creates significant geographic variation in uptake [18]. A region with a proactive health authority and a tight budget might run its own tenders and drive high biosimilar adoption, while a neighboring region might be much slower to act.

- France: Has historically seen slower uptake, partly due to a strong tradition of physician autonomy and initial reluctance to support switching of stable patients. However, policy has been evolving, with the introduction of financial incentives for physicians and pharmacists who meet biosimilar prescribing targets, mirroring some aspects of the German model.

- Italy: Is highly regionalized. Some northern regions, like Lombardy and Veneto, have been very aggressive in using tenders to drive down prices and mandate uptake, achieving results similar to the Nordic countries. In contrast, some southern regions have lagged behind. This creates an internal patchwork market that can be challenging for manufacturers to navigate.

The experience in these countries highlights a crucial lesson: a positive national HTA recommendation is necessary, but not sufficient. Cost-effectiveness is ultimately realized at the local level, and without aligned incentives and clear implementation plans for regional payers and hospitals, national savings goals can remain elusive.

The North American Conundrum: The U.S. and Canada

While geographically close, the United States and Canada offer a study in contrasts when it comes to biosimilar policy and cost-effectiveness. Canada, with its single-payer provincial systems, has increasingly moved towards European-style mandates, while the U.S. continues to wrestle with the structural barriers of its commercial market, though recent legislation offers a glimmer of hope for change.

The United States: Overcoming Structural Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption

As we’ve established, the U.S. market has been the toughest nut for biosimilars to crack. The combination of rebate walls, formulary complexities, and a fragmented payer landscape has led to frustratingly slow uptake and unrealized savings. However, the ground is starting to shift, driven by legislative action and evolving market understanding.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and its Potential to Reshape the Landscape

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), signed into law in 2022, represents the most significant pharmaceutical policy reform in the U.S. in decades. While not exclusively focused on biosimilars, several of its provisions could profoundly alter their cost-effectiveness and uptake [19].

- Medicare Price Negotiation: The IRA empowers Medicare to directly negotiate prices for a selection of high-cost drugs, including many biologics. The threat of a negotiated price, which could be substantially lower, may push originator companies to compete more aggressively on price with biosimilars before their drug becomes negotiation-eligible.

- Redesigned Medicare Part D Benefit: The IRA redesigns the senior prescription drug benefit, capping out-of-pocket costs for patients and increasing insurers’ liability. This makes plans much more sensitive to high list prices. A biosimilar with a lower list price becomes more attractive to plans than a high-list-price originator with a large rebate, as it reduces the plan’s financial exposure. This could begin to dismantle the rebate wall.

- Biosimilar Add-On Payment: To incentivize physicians, the IRA temporarily increases the add-on payment for administering biosimilars in Medicare Part B from 6% of the biosimilar’s price to 8% of the originator’s price. This makes prescribing the biosimilar significantly more profitable for a physician’s practice, directly countering the financial inertia that favored originators.

The full impact of the IRA will unfold over several years, but it signals a clear policy shift towards favoring lower list-price drugs, a change that could finally unlock the competitive potential of the U.S. biosimilar market.

The Ongoing Debate: Interchangeability and its Market Impact

Another unique feature of the U.S. system is the FDA designation of “interchangeability.” An interchangeable biosimilar has undergone additional studies (typically a switching study) to prove that a patient can be switched back and forth between it and the originator without any increased risk or diminished efficacy [20].

This designation is crucial because, subject to state pharmacy laws, it allows a pharmacist to substitute the interchangeable biosimilar for the prescribed originator without consulting the prescribing physician—much like how generic drugs are dispensed. For a long time, it was believed that achieving interchangeability would be the “golden ticket” to market success in the U.S.

The launch of the first adalimumab biosimilars in 2023 is testing this theory. Some products have launched with the interchangeability designation, while others have not. The early data is complex, but it suggests that while interchangeability is a valuable differentiator, payer coverage and net price remain the most powerful drivers of uptake. A non-interchangeable biosimilar with exclusive formulary access from a major PBM may achieve higher market share than an interchangeable competitor that is not on the formulary. The story of interchangeability underscores that in the U.S., market access is king, and no single regulatory designation can overcome fundamental formulary and rebate challenges.

Canada: Provincial Policies and the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA)

Canada’s healthcare system is best described as a collection of single-payer systems. Each of the 10 provinces and 3 territories manages its own public drug plan. This created a fragmented negotiating landscape until the formation of the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) in 2010 [21]. The pCPA brings together the provinces and territories to conduct joint negotiations with drug manufacturers, leveraging their collective purchasing power to achieve lower prices.

For biosimilars, the pCPA negotiates a national floor price, and then individual provinces implement policies to drive uptake.

The Rise of Mandatory Switching Policies

Initially, Canadian provinces were hesitant to force patients to switch from an originator to a biosimilar. They relied on “initiation” policies, where new patients would be started on the lower-cost biosimilar, but existing patients could remain on the originator. This led to slower-than-expected savings.

Inspired by European successes, this began to change dramatically in 2019 when British Columbia became the first province to announce a “mandatory switching” (or “non-medical switching”) policy [22]. Under this policy, patients on certain originator biologics were given a six-month transition period to switch to a government-funded biosimilar version. After this period, the public drug plan would no longer cover the originator product.

The move was a resounding success. It was met with high compliance from physicians and patients, achieved over 90% conversion rates, and generated substantial savings for the province. The success in B.C. created a domino effect. One by one, other provinces, including Alberta, Quebec, and Ontario, have followed suit, implementing their own mandatory switching policies.

This bold policy shift has transformed Canada from a relatively slow adopter into a global leader in biosimilar uptake. It demonstrates how single-payer systems, even within a federated structure, can act decisively to realize the cost-effectiveness potential of biosimilars once a successful policy precedent has been set.

Emerging Markets and Asia-Pacific: A New Frontier for Biosimilars

While much of the focus has been on Europe and North America, the landscape of cost-effectiveness for biosimilars is rapidly evolving across Asia and other emerging markets. These regions present a unique combination of opportunities—huge patient populations, growing healthcare expenditure—and challenges, including diverse regulatory systems and varied economic conditions.

Japan’s Pro-Biosimilar Stance: A Model of Price Regulation and Uptake

Japan, the world’s third-largest pharmaceutical market, has embraced biosimilars with a clear and effective policy framework. The Japanese system is characterized by a strong central government role in healthcare pricing [23]. When a biosimilar is launched, its initial price is typically set at 70% of the originator’s price. If multiple biosimilars are available, the price can be set even lower.

Furthermore, every two years, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) conducts a comprehensive drug price revision, which further reduces the prices of both the originator and the biosimilars based on their market performance. This creates a continuous downward price pressure.

To encourage uptake, the government has set ambitious biosimilar volume share targets (aiming for 80% share for many products) and has implemented measures to foster physician and patient confidence, including extensive educational campaigns. The result is a market with predictable pricing, strong government support, and steadily increasing biosimilar adoption, making Japan a model for how a well-regulated, fee-for-service system can achieve significant cost-effectiveness.

South Korea: A Global Biosimilar Powerhouse

South Korea is unique in that it is not just a major market for biosimilars but a global leader in their development and manufacturing. Companies like Celltrion and Samsung Bioepis are at the vanguard of the industry, securing approvals and launching products across the globe [24].

This strong domestic industry has created a pro-biosimilar environment at home. The Korean government is keen to support its homegrown champions. While the domestic uptake of biosimilars has been solid, the primary focus of these Korean giants is on the lucrative export markets of Europe and the U.S. Their cost-effectiveness strategy is global. By leveraging South Korea’s advanced manufacturing capabilities and lower development costs, they can compete aggressively on price in Western markets, playing a key role in driving down global biologic prices. The success of Korean firms demonstrates how national industrial policy can intersect with healthcare policy to create a globally competitive biosimilar ecosystem.

The Complexities of China and India: Manufacturing Hubs with Evolving Regulation

China and India represent the next frontier, both as massive potential markets and as manufacturing powerhouses.

- India: Long known as the “pharmacy of the developing world,” India has a well-established generic drug industry and a burgeoning biosimilar sector. Historically, its regulatory pathway for “similar biologics” was less stringent than those of the EMA or FDA, leading to a large number of domestically approved products that couldn’t be sold in highly regulated markets. However, India is rapidly upgrading its regulatory standards to align more closely with global norms, aiming to become a major exporter of biosimilars to the West [25]. The cost-effectiveness driver here is sheer manufacturing scale and low production costs, which could lead to hyper-competitive pricing in the future.

- China: China’s regulatory landscape for biosimilars has undergone a massive overhaul. The National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) has implemented a new, rigorous technical guidance aligned with international standards, moving away from its previous “copycat” approach [26]. With its vast patient population and a government focused on controlling healthcare costs through volume-based procurement (VBP) programs—similar to national tenders—China is poised to become the single largest biosimilar market in the world. The cost-effectiveness dynamics will be driven by intense domestic competition and government-mandated price cuts.

For global pharmaceutical companies, these markets are a double-edged sword: they offer enormous growth potential but also threaten to unleash a new wave of low-cost competitors onto the world stage.

Beyond Price: The Hidden Drivers of Cost-Effectiveness

A myopic focus on the percentage discount of a biosimilar misses a huge part of the value equation. Long-term, sustainable cost-effectiveness is built on more than just a low price. It depends on a healthy market, stakeholder trust, and reliable execution.

The Value of Competition: Market Dynamics and Sustainable Savings

The true economic magic of biosimilars is not the price of the first entrant, but the competitive dynamic that multiple entrants create.

- Price Erosion: The first biosimilar might launch with a 15-30% discount. The second and third, however, must compete with both the originator and the first biosimilar, leading to further price erosion. In mature European markets with 4-5 competitors, it is this multi-player competition that drives prices down by 50% or more over time. A healthy market with multiple suppliers is more valuable to a health system in the long run than a single biosimilar that offers a steep initial discount but then faces no further competition.

- Originator Response: Biosimilar competition forces the originator company to respond. They may lower their own price, offer larger rebates, or compete in tenders. This price response from the market leader is a major source of savings for the health system, a benefit that is entirely attributable to the presence of biosimilar competitors.

- Sustainability: A market with several successful biosimilar suppliers is more stable. It prevents the single-supplier dependency seen in some “winner-takes-all” tender systems and ensures a resilient supply chain, which is a critical component of long-term cost-effectiveness.

Physician and Patient Confidence: Overcoming the “Nocebo” Effect

A biosimilar can’t be cost-effective if doctors won’t prescribe it and patients won’t take it. Building trust is a critical, and often underestimated, component of successful uptake.

Initial physician hesitancy is common, revolving around concerns about immunogenicity (the risk of a patient’s immune system reacting to the new product) and the validity of extrapolating data from one approved indication to others. Overcoming this requires:

- Robust Education: Manufacturers and health authorities must proactively provide clear, science-based education to clinicians, explaining the “totality of the evidence” concept and presenting the rigorous data supporting biosimilarity.

- Real-World Evidence (RWE): As biosimilars are used by thousands of patients, post-market surveillance data and RWE studies become invaluable. Data showing that switching policies in Europe have not led to negative patient outcomes are powerful tools for reassuring skeptical physicians in other parts of the world.

- Managing the “Nocebo” Effect: The nocebo effect is the negative psychological counterpart to the placebo effect, where a patient’s negative expectations about a treatment can cause them to experience adverse effects. If a patient is told they are being switched to a “cheaper” drug, they may become anxious and attribute any minor ailment to the new medication. Successful switching programs require careful, positive communication from physicians and nurses, framing the switch as a positive step that helps the healthcare system treat more people, without compromising their individual care.

Supply Chain Reliability and Manufacturer Reputation

In the treatment of chronic diseases, continuity of supply is paramount. A stock-out of a critical biologic is not an inconvenience; it’s a medical crisis. Therefore, a payer or hospital’s assessment of a biosimilar’s cost-effectiveness must include an evaluation of the manufacturer’s ability to reliably supply the market.

A biosimilar manufacturer with a slightly higher price but a flawless supply track record and a strong reputation for quality may be seen as providing better overall value than an unknown competitor with a rock-bottom price but an unproven supply chain. For biosimilar companies, investing in robust manufacturing, redundant capacity, and transparent supply chain management is not just a cost center; it’s a key competitive differentiator and a pillar of their value proposition.

Strategic Implications for Pharmaceutical Companies

The rise of the global biosimilar market is not just a phenomenon to be analyzed; it’s a strategic reality that demands a response from every player in the industry. The implications are profound, both for the incumbent originator companies and for the biosimilar developers seeking to challenge them.

For Originator Companies: Life Cycle Management in the Biosimilar Era

For an originator company facing the loss of exclusivity on a multi-billion dollar biologic, the goal is to maximize the value of the franchise for as long as possible. This is no longer about simply defending a patent; it’s about sophisticated life cycle management.

- Building a Moat: Before the patent cliff, companies work to build a moat around their product. This includes creating the “patent thickets” discussed earlier, but also generating vast amounts of real-world evidence to solidify the brand’s reputation, and developing improved delivery devices (e.g., auto-injectors with better ergonomics) that create patient and physician loyalty.

- Competing with Yourself: Some originators are launching their own “authorized biologic” or “branded biosimilar” to compete in the market they once dominated. This allows them to participate in the lower-priced segment and retain some market share rather than ceding it all to third-party competitors.

- Value-Based Contracting: In markets like the U.S., originators can use sophisticated contracting and rebating strategies to maintain preferred formulary status, as seen in the infliximab case. However, with policy changes like the IRA, this strategy may become less effective over time.

- Innovating Beyond: The ultimate defense is to innovate. By developing next-generation “bio-betters” (biologics with improved efficacy, safety, or dosing schedules) or entirely new therapeutic approaches, originators aim to move the market to a new standard of care before biosimilar competition for their older product fully matures.

For Biosimilar Developers: Market Entry and Differentiation Strategies

For biosimilar developers, the challenge is to carve out a profitable share of a highly competitive market. Success requires more than just a low price; it demands strategic acumen.

- Portfolio and Target Selection: The first strategic choice is which biologics to pursue. This involves a complex analysis of market size, the strength of the originator’s patent thicket (using intelligence from services like DrugPatentWatch), the number of expected competitors, and the specific market access dynamics in key geographic regions.

- Global-to-Local Launch Sequencing: Companies must decide where and when to launch. Often, they will prioritize Europe to gain early experience and generate real-world evidence before tackling the more complex U.S. market.

- Timing is Everything: Being the first biosimilar to market can confer a significant advantage in securing early formulary wins and establishing a market presence. However, later entrants can sometimes succeed by offering even deeper discounts or by learning from the market access challenges faced by the pioneers.

Beyond Price: Value-Added Services and Device Innovation

As biosimilar markets become more crowded and prices converge, competing on price alone becomes a race to the bottom. The smartest companies are differentiating themselves through value-added propositions.

- Device Parity and Superiority: At a minimum, a biosimilar must offer a delivery device (like an auto-injector pen) that is as good as the originator’s. Some companies are going a step further, investing in developing devices that are demonstrably better—easier to use, less painful, or with features that help patient adherence.

- Patient Support Programs: Offering robust patient support services, such as nurse hotlines, co-pay assistance programs, and educational materials, can be a major differentiator, particularly in markets where patients and physicians have a choice between multiple biosimilars.

- Payer Partnerships: Instead of just offering a low price, successful biosimilar companies work as partners with payers. They provide sophisticated BIA models, share data from other markets, and offer flexible contracting solutions to help the payer achieve its savings and uptake goals.

Leveraging Data for Competitive Intelligence

In this incredibly complex and fast-moving environment, data is the ultimate weapon. Both originator and biosimilar companies are investing heavily in competitive intelligence. They track:

- Pipeline Data: Who is developing which biosimilar? When are their clinical trials expected to read out?

- Regulatory Filings: When has a competitor filed for approval with the EMA or FDA?

- Pricing and Tender Results: What prices are being achieved in Norwegian tenders or German regional contracts?

- Uptake Data: What is the market share of each competitor in every key market, month by month?

This granular, real-time data allows companies to model competitor behavior, anticipate market shifts, and fine-tune their own pricing and access strategies. The ability to effectively gather, analyze, and act on this data is what separates the winners from the losers in the global biosimilar market.

The Future of Biosimilars: What’s Next on the Horizon?

The biosimilar story is far from over; in many ways, it’s just beginning. The first wave targeted major anti-inflammatory drugs and supportive care products. The next waves will be even more complex and commercially significant, and new technologies will continue to reshape the competitive landscape.

Second-Wave Biosimilars and More Complex Biologics

The next major patent cliffs are for some of the most complex and high-cost biologics on the market, particularly in oncology and ophthalmology.

- Oncology mAbs: Biosimilars for blockbuster cancer therapies like pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) are already in late-stage development. Their arrival will have a monumental impact on cancer care budgets, potentially freeing up billions to be spent on new, innovative combination therapies. However, oncologists can be a cautious group, and demonstrating the value of switching stable cancer patients will require significant educational effort and compelling data.

- Ophthalmology: Biologics like aflibercept (Eylea) for age-related macular degeneration represent another huge market opportunity. The introduction of biosimilars here could dramatically increase access to sight-saving treatments for aging populations worldwide.

- Orphan Drugs: Biologics for rare diseases, which often come with exceptionally high price tags, are also becoming targets. Biosimilars in this space could offer a lifeline to health systems struggling to afford these ultra-expensive therapies.

The Rise of Biobetters: A Competitive Threat or a Different Game?

While biosimilar developers aim for similarity, another group of companies is pursuing a different strategy: creating “biobetters.” A biobetter is a new biologic that uses the same mechanism of action as an existing originator biologic but is intentionally modified to offer a clinical advantage—for example, a longer half-life allowing for less frequent dosing, a better side-effect profile, or higher efficacy [27].

Biobetters are not biosimilars; they are new, innovative drugs that require a full R&D program and are patent-protected. They represent a competitive threat to both originators and biosimilars. An originator might develop a biobetter of its own product as a life cycle management strategy, aiming to switch the market to the new-and-improved version before biosimilars for the original product arrive. For a biosimilar company, the launch of a successful biobetter can shrink the potential market for their product. The interplay between originators, biosimilars, and biobetters will create an even more complex and dynamic competitive environment in the years to come.

The Impact of AI and Big Data on Biosimilar Development and Market Analysis

Technology will continue to be a disruptive force. Artificial intelligence and big data are already beginning to impact the biosimilar landscape in several ways:

- Accelerating Development: AI algorithms can analyze complex protein structures and predict which modifications are least likely to affect function, potentially speeding up the early stages of biosimilar development and manufacturing process design.

- Optimizing Clinical Trials: AI can help in designing more efficient clinical trials by identifying the most responsive patient populations and optimizing trial site selection.

- Predictive Market Analytics: For commercial teams, AI-powered platforms can analyze vast datasets—including claims data, pricing data, and formulary information—to build predictive models of biosimilar uptake, forecast price erosion with greater accuracy, and identify market access opportunities at a granular level.

As these technologies mature, they will give a significant edge to the companies that can integrate them most effectively into their R&D and commercial strategies, further raising the bar for competition.

Conclusion: Weaving a Global Tapestry of Value and Access

The journey through the world’s healthcare systems reveals a clear and compelling truth: the cost-effectiveness of biosimilars is not an inherent property of the drug itself, but a potential that is either unlocked or constrained by the system around it. We have seen how the concentrated power of single-payer systems like the UK’s NHS can execute textbook-perfect strategies, delivering massive savings and rapid uptake through centralized procurement. We have contrasted this with the fragmented U.S. market, where perverse incentives created by rebate walls have historically stifled competition, leaving billions in savings unrealized—a challenge that new legislation is only now beginning to address.

We’ve explored the varied and inventive models across Europe—from the fierce “winner-takes-all” tenders in Norway to the sophisticated physician quotas in Germany—each offering a unique lesson in market dynamics. And we’ve looked to the East, where Japan’s regulatory precision, South Korea’s industrial might, and the colossal potential of China and India are reshaping the global supply and demand for these critical medicines.

The ultimate lesson is that price is only the beginning of the story. True, sustainable cost-effectiveness is woven from a tapestry of factors: the long-term value of a competitive, multi-supplier market; the critical importance of building physician and patient trust to drive adoption; and the foundational need for a reliable supply chain.

For the business and pharmaceutical professionals navigating this landscape, the path forward is clear. Success is no longer just about science or sales; it’s about deep, systemic understanding. It’s about leveraging granular data on patents, pricing, and policy to build robust strategies. Whether you are defending an originator franchise or launching a new biosimilar challenger, your success will be defined by your ability to understand and adapt to the unique rules of the game in each and every market. The biosimilar revolution is here, and it promises not just to lower costs, but to reshape our very concept of value in medicine, pushing us toward a more sustainable and accessible future for all.

Key Takeaways

- Cost-Effectiveness is Context-Dependent: A biosimilar’s value is not universal. It is profoundly shaped by the structure of the local healthcare system, including whether it is a single-payer or multi-payer model.

- Single-Payer Systems Excel at Uptake: Centralized systems like the UK’s NHS or province-led systems in Canada can use their purchasing power and policy mandates (like tenders and mandatory switching) to achieve rapid, high-level biosimilar adoption and maximize savings.

- U.S. Market Faces Structural Hurdles: The fragmented U.S. multi-payer system, with its PBMs and “rebate walls,” has historically slowed biosimilar uptake. Policy changes like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are aimed at correcting these misaligned incentives.

- Europe is a Laboratory of Policies: There is no single “European model.” The continent offers a range of effective strategies, from aggressive Nordic tenders and German physician quotas to the more complex regional dynamics in France and Italy.

- Price is Not the Only Factor: Sustainable cost-effectiveness also depends on non-price factors like fostering a competitive market with multiple suppliers, building physician and patient confidence to overcome hesitancy, and ensuring supply chain reliability.

- Strategic Data is Crucial: For both originator and biosimilar companies, success hinges on leveraging detailed competitive intelligence. Services that track patent expirations, like DrugPatentWatch, pricing data, and regulatory timelines are essential tools for strategic planning.

- The Future is More Complex: The next wave of biosimilars will target more complex diseases like cancer. The competitive landscape will be further shaped by the emergence of “biobetters” and the impact of technologies like AI in both development and commercial analytics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. If a biosimilar is proven to be just as effective, why wouldn’t a physician always prescribe the cheaper option?

This is a central paradox, especially in markets like the U.S. The decision is often not left entirely to the physician. Their prescribing choices are heavily influenced by the patient’s insurance formulary, which is determined by PBMs. Due to “rebate walls,” the high-list-price originator may actually have a lower net cost to the PBM/insurer than the biosimilar, leading them to give the originator preferential formulary status. Additionally, physicians in fee-for-service models may have financial incentives tied to the percentage-based reimbursement of a higher-priced drug. Finally, simple human factors like inertia (“if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it”) and a lack of time to research the data for every new biosimilar can also contribute to slower-than-expected uptake without strong systemic incentives.

2. Is a “winner-takes-all” tender system, like Norway’s, the best model for cost-effectiveness?

It depends on your definition of “best.” If the sole objective is to achieve the absolute lowest price in a given year, then yes, it is spectacularly effective. The intense competition drives prices down dramatically. However, this model carries significant risks that can impact long-term cost-effectiveness. It can create supply chain vulnerability by relying on a single supplier. It can also deter market entry for some manufacturers who fear getting zero revenue after a massive R&D investment, potentially leading to less competition and higher prices in the long run. Many systems now prefer awarding tenders to 2-3 suppliers to balance aggressive pricing with market sustainability and supply security.

3. What is “non-medical switching,” and why is it so controversial?

Non-medical switching refers to a policy where a health plan requires a patient who is stable on an originator biologic to switch to a biosimilar for purely economic reasons. It’s controversial because physician and patient advocacy groups argue it can disrupt a patient’s stable treatment regimen, potentially cause patient anxiety (the nocebo effect), and interfere with the physician-patient relationship. Proponents, including payers and health systems, argue that given the rigorous “totality-of-the-evidence” standard for biosimilar approval, there is no scientific basis to expect different outcomes. The widespread success and lack of negative safety signals from mandatory switching programs in Canada and parts of Europe have provided strong real-world evidence supporting the practice as a safe and highly effective cost-containment tool.

4. How will the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) specifically help a biosimilar compete against an originator with a massive rebate in the U.S.?

The IRA helps in two key ways. First, the redesign of the Medicare Part D benefit makes insurers more responsible for a drug’s total cost. This shifts their focus from the size of the rebate (which they share) to the actual net cost of the drug. A biosimilar with a lower list price, even with a smaller rebate, can result in a lower total cost and less financial liability for the insurer, making it more attractive. Second, the IRA’s drug price negotiation program creates a new threat for originators. A high-list-price biologic is a prime target for negotiation, which could result in a steep, government-mandated price cut. This may incentivize originators to lower their price voluntarily or compete more fairly with biosimilars to avoid the negotiation process, effectively weakening the power of the rebate wall.

5. As a biosimilar developer, is it better to be the first to market or to launch later with a lower price and a better device?

This is a classic “first-mover vs. fast-follower” strategic dilemma. Being first to market carries a significant advantage. You can establish relationships with payers, lock in early formulary contracts, and build brand recognition before competitors arrive. The first biosimilar often retains a durable market share advantage. However, being a “fast follower” also has its merits. You can learn from the first mover’s market access successes and failures. You can potentially enter with an even lower price to steal share, and importantly, you may have had more time to develop a superior delivery device or gather more comprehensive data. The optimal strategy depends on the specific biologic, the number of expected competitors, and the company’s risk tolerance and manufacturing capabilities. There is no single right answer, and both strategies have led to commercial success.

References

[1] U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). (2019). Biosimilar and Interchangeable Products. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-products

[2] Gotz, B. S. (2002). The history of insulin. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 42(5), S2-S4.

[3] Wouters, O. J., McKee, M., & Luyten, J. (2020). Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009-2018. JAMA, 323(9), 844–853.

[4] Feldman, R. (2018). May Your Drug Price Be Ever Green. Journal of Law and the Biosciences, 5(3), 590-623.

[5] European Medicines Agency (EMA). (2014). Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: quality issues (revision 1). EMA/CHMP/BWP/247713/2012.

[6] Weinstein, M. C., & Stason, W. B. (1977). Foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. New England Journal of Medicine, 296(13), 716-721.

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2013). Measuring and valuing health. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/chapter/measuring-and-valuing-health

[8] McCabe, C., Claxton, K., & Culyer, A. J. (2008). The NICE cost-effectiveness threshold: what it is and what that means. Pharmacoeconomics, 26(9), 733-744.

[9] Mauskopf, J. A., Sullivan, S. D., Annemans, L., Caro, J., Mullins, C. D., Nuijten, M., … & Trueman, P. (2007). Principles of good practice for budget impact analysis: report of the ISPOR Task Force on good research practices—budget impact analysis. Value in Health, 10(5), 336-347.

[10] NHS England. (2019). NHS saves hundreds of millions of pounds as new figures reveal success of cutting-edge deals for best value medicines. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/2019/10/nhs-saves-hundreds-of-millions/

[11] Aris, E. (2019). Adalimumab biosimilars: the NHS’s masterclass in procurement. Pharmaceutical Technology.

[12] Socal, M. P., & Bai, G. (2020). The problem with the US pharmaceutical rebate system and how to fix it. The American Journal of Managed Care, 26(8), 329-331.

[13] Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM). (2022). 2022 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report.

[14] Sarpatwari, A., Barenie, R. E., Curfman, G. D., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2019). The US biosimilar market is not working as intended. The BMJ, 365, l2334.

[15] IQVIA. (2021). Biosimilars in the United States: The Evolving Landscape.

[16] Kanavos, P., & Johnston, E. (2015). Scoping study on the impact of biosimilars on the national health service. LSE Health, London School of Economics and Political Science.

[17] Verband Forschender Arzneimittelhersteller (vfa). (2021). The German healthcare system: An overview.

[18] Rémuzat, C., Toumi, M., & Vataire, A. L. (2017). Overview of the biosimilar landscape in Europe. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 17(10), 1279-1286.

[19] Cubanski, J., & Neuman, T. (2022). Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

[20] U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). (2019). Guidance for Industry: Considerations in Demonstrating Interchangeability With a Reference Product.

[21] Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA). About the pCPA. Retrieved from https://www.pcpa-apc.ca/about-pcpa

[22] Government of British Columbia. (2019). B.C. leads the way with biosimilars initiative. Retrieved from https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2019HLTH0080-001083

[23] Tsumura, H. (2020). Japan’s biosimilar market: Present status and future perspective. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal (GaBI Journal), 9(2), 65-68.

[24] Lee, J. Y. (2019). The rise of South Korea’s biosimilar industry. Nature Biotechnology, 37(7), 717-719.

[25] Nag, S. (2021). The Evolving Regulatory Landscape for Biosimilars in India. Journal of Clinical Research & Bioethics, 12(S11), 001.

[26] National Medical Products Administration (NMPA). (2021). Technical Guideline for the Development and Evaluation of Biosimilars.

[27] Storz, U. (2016). Biobetters: A new-generation of biologics. Bio-Drugs, 30(5), 295-300.