I. Executive Summary

Follow-on pharmaceutical innovations represent a critical, often underestimated, dimension of medical progress. These advancements, which build upon existing medicines by enhancing safety, efficacy, patient convenience, or expanding therapeutic applications, are far from trivial modifications. They are the result of significant research and development investments and deliver profound benefits to patients and healthcare systems. Robust patent protection for these innovations is indispensable, serving as a vital incentive for the continued investment required to transform promising drug candidates into optimized, accessible treatments. While concerns about market exclusivity and affordability, often encapsulated in the “evergreening” debate, are valid and warrant careful consideration, the existing patent framework, when rigorously applied and complemented by competition laws, is designed to balance innovation with public access. This report will demonstrate that denying patent eligibility for valuable follow-on innovations would ultimately stifle medical progress, reduce patient access to improved therapies, and undermine the very goals of public health.

II. Introduction: Defining Follow-On Pharmaceutical Innovation

Follow-on pharmaceutical innovation, frequently termed incremental or continued innovation, constitutes a diverse and crucial category of advancements aimed at refining and improving existing medicinal products. These innovations are not mere extensions of prior art but represent distinct efforts to develop safer, more effective, or more patient-friendly variations of original therapies.1 The nature of these improvements often involves substantial research and development (R&D) and clinical validation, leading to tangible benefits for patients and healthcare systems.

The scope of follow-on innovation is broad, encompassing a variety of technological enhancements:

- Improved Formulations and Dosage Forms: This category includes the development of extended-release formulations that enable less frequent administration and maintain more consistent drug levels, thereby enhancing patient adherence and therapeutic consistency.2 Examples also include the conversion of injectable drugs to orally administrable forms, which significantly improves patient convenience and compliance, or the creation of specialized formulations like pediatric chewable tablets or transdermal patches to simplify medication regimens for specific patient demographics.3 For instance, the pulmonary arterial hypertension treatment treprostinil evolved from an intravenous infusion to an inhaled formulation and then an oral tablet, offering more convenient administration routes for patients.6

- Expanded Therapeutic Applications (New Indications): This involves identifying and validating new uses for existing drugs, broadening their application to new therapeutic areas or previously unaddressed patient populations. A notable example is the expansion of adult-approved cancer therapies to pediatric patients through rigorous clinical trials.2 Data indicates that between 2008 and 2018, 65% of oncology drugs gained at least one subsequent indication for another type of cancer post-approval, highlighting the prevalence and value of this form of innovation.2

- Enhanced Safety Profiles and Reduced Side Effects: A significant focus of follow-on innovation is the improvement of a drug’s safety profile or the reduction of its adverse effects. Such advancements can lead to new, patentable drugs, even when the core active compound is not novel, as enhanced safety contributes directly to a drug’s unique value proposition and patentability.2 Designing drugs with inherent safety features, such as reduced toxicity or improved selectivity for target cells, can significantly increase the novelty aspect of patent applications.7

- Novel Drug Delivery Methods: This area sees the development of sophisticated systems, including nanoparticles, liposomes, and microcapsules, designed to enhance drug targeting, improve bioavailability, and minimize systemic side effects.8 Innovations like long-acting injectable formulations have revolutionized treatments for conditions such as psychotic disorders and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by reducing dosing frequency and improving patient adherence.11

- Variations in Chemical Form: Minor alterations to the original drug molecule, such as isomerization, or the development of new salt forms, polymorphs, or enantiomers, can yield patentable improvements. These modifications often offer advantages in drug stability, solubility, or bioavailability, even if the therapeutic benefits are not dramatically different.3 For example, a particular salt formation of bupropion was found patentable due to improved stability, allowing for a more stable once-a-day dosage.12

- New Methods of Synthesis or Manufacturing Processes: Innovations in the processes used to produce drug substances can lead to more efficient, cost-effective, and scalable manufacturing, which can also be eligible for patent protection.3

- New Dosage Regimens: Optimizing the frequency or amount of drug administration can significantly improve therapeutic outcomes or reduce side effects. This involves careful clinical study to determine the most effective and tolerable dosing schedules.3

Biopharmaceutical innovation is fundamentally a cumulative process, where each new discovery and improvement builds upon prior knowledge and existing therapies.2 Follow-on innovations are essential to this continuum, serving to refine, optimize, and add value to first-in-class breakthroughs.2 These incremental advancements are far from minor; they are crucial in transforming promising, but often imperfect, drug candidates into safe, effective, and broadly accessible treatment options that genuinely address patient needs in the real world.2 They also play a central role in the ongoing maintenance and adaptation of essential medicines, enabling the personalization of treatment approaches to suit diverse patient profiles.17 Historical analysis across various industries consistently demonstrates that incremental innovation represents a critical stage of technological evolution. It significantly enhances the commercial value and societal impact of scientifically novel inventions, thereby expanding their adoption and often laying the groundwork for future breakthrough discoveries.18

The consistent characterization of follow-on innovation across various sources as genuine improvements—in terms of safety, efficacy, and patient-friendliness—underscores their intrinsic value and directly supports the argument for their patent eligibility. This understanding refutes the notion that these are merely trivial modifications. Instead, it highlights that these advancements often entail significant R&D investment and deliver tangible benefits to patients. Consequently, denying patent protection for such innovations would inevitably diminish the incentive for crucial research that directly enhances patient well-being and improves the efficiency of healthcare systems.

Furthermore, the emphasis on “patient-centric improvements” and the “personalization of medicine” as core elements of follow-on innovation signals a notable evolution in the pharmaceutical R&D landscape. This shift indicates that the value of a drug is increasingly defined not solely by its initial chemical discovery, but by how effectively it meets the diverse and evolving needs of patients in clinical practice. This evolving focus necessitates that patent systems adapt to incentivize these types of innovations. Such an adaptation is crucial because these advancements directly translate into better real-world health outcomes, even when they involve optimizing existing active compounds rather than discovering entirely new ones.

III. The Profound Value of Follow-On Innovations

The benefits derived from follow-on pharmaceutical innovations extend far beyond incremental enhancements, profoundly impacting patient outcomes, improving quality of life, and driving significant efficiencies within healthcare systems. These advancements are instrumental in transforming the utility and accessibility of existing therapies.

Enhancing Patient Outcomes and Quality of Life

Follow-on biopharmaceutical innovations deliver substantial health benefits by improving the safety and efficacy of existing therapies, addressing previously unmet patient needs, expanding therapeutic applications, and significantly enhancing treatment adherence.2 These advancements frequently result in treatments that are not only more effective but also more applicable and user-friendly, directly leading to improved patient compliance and an elevated quality of life.2 For example, simplifying complex medication regimens from multiple daily doses to a single daily dose can dramatically boost patient adherence, with reported increases from 59% to 83.6%.5 This simplification reduces the burden on patients, ensuring they receive the full therapeutic benefit of their medications.

Innovations in drug delivery systems, such as the development of oral formulations to replace more invasive injections or the introduction of transdermal patches, significantly increase patient comfort, reduce dosing frequency, and can minimize systemic side effects by bypassing the digestive system.3 Advanced delivery technologies, including liposomes and lipid nanoparticles, are engineered to target specific tissues, maximizing local drug concentration while minimizing systemic toxicity, which is particularly beneficial for treating persistent or complex infections.10 From a patient’s perspective, improvements that make a drug more tolerable or easier to administer can be as transformative as the original drug discovery itself, directly influencing adherence and overall quality of life.2

Driving Health System Efficiencies and Economic Benefits

Beyond individual patient gains, follow-on innovations yield substantial economic and health-system advantages.2 By fostering improved adherence and expanding treatment options, these innovations contribute significantly to reducing work absenteeism and hospitalizations, thereby boosting overall societal productivity, enhancing healthcare quality, and ultimately lowering aggregate healthcare costs.2

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate a strong positive correlation between pharmaceutical innovation and improved population-level health outcomes, alongside substantial societal net economic benefits.19 For instance, research indicates that a $1 increase in pharmaceutical expenditure attributable to innovation has been associated with a $3.65 reduction in hospital-care expenditure, highlighting the significant cost savings generated by effective new therapies.19 Furthermore, the adoption of newer prescription drugs has been shown to reduce lost workdays and contribute to a net reduction in the total cost of treating specific medical conditions.19 Incremental improvements can also stimulate increased price competition among drug manufacturers, leading to further cost savings within the healthcare sector.18

Table 1: Types and Benefits of Follow-On Pharmaceutical Innovations

| Type of Innovation | Description | Key Patient/Health System Benefits | Illustrative Examples |

| Improved Formulations & Dosage Forms | Modifying the physical form or composition of a drug. | Enhanced patient compliance, reduced dosing frequency, improved stability, better bioavailability, easier administration for specific populations. | Extended-release tablets (e.g., once-daily regimens) 3; Oral formulations replacing injections (e.g., Treprostinil from IV to oral) 3; Pediatric chewable tablets.3 |

| Expanded Therapeutic Applications (New Indications) | Discovering new diseases or patient populations for an existing drug. | Broader treatment options, addressing unmet needs in new patient groups, leveraging existing safety data. | Expanding adult cancer therapies to pediatric patients 2; Oncology drugs gaining multiple subsequent indications.2 |

| Enhanced Safety Profiles & Reduced Side Effects | Modifying a drug to lessen adverse reactions or improve tolerability. | Improved patient experience, increased adherence, reduced treatment discontinuation, better quality of life. | Repurposing or reformulating existing drugs to reduce side effects 7; Designing drugs with inherent safety features.7 |

| Novel Drug Delivery Methods | Developing new systems to deliver drugs to specific targets or in controlled ways. | Targeted drug delivery, reduced systemic toxicity, improved bioavailability, enhanced efficacy, greater patient comfort. | Nanoparticles, liposomes, dendrimers 8; Transdermal patches 3; Long-acting injectables (e.g., cabotegravir for HIV PrEP).11 |

| Variations in Chemical Form | Altering the chemical structure (e.g., salt, polymorph, enantiomer). | Improved drug stability, enhanced solubility, better bioavailability, optimized manufacturing processes. | New salt forms (e.g., bupropion salt for stability) 3; Polymorphs with unexpected properties.3 |

| New Methods of Synthesis or Manufacturing Processes | Developing more efficient or scalable ways to produce drug substances. | Reduced production costs, increased supply, improved drug purity. | Innovations leading to more efficient and scalable production.3 |

| New Dosage Regimens | Optimizing the frequency or amount of drug administration. | Improved therapeutic outcomes, reduced side effects, enhanced patient adherence. | Once-daily administration 3; Specific loading and maintenance doses.13 |

The extensive range of patient and economic benefits, supported by numerous examples, clearly demonstrates that follow-on innovations are not merely “me-too” drugs, as some critics contend.18 Instead, they represent genuine advancements that significantly improve health outcomes and contribute to the economic efficiency of healthcare systems. A policy framework that discourages the patenting of these valuable innovations would, by extension, actively undermine public health and economic well-being by removing a crucial incentive for their development. This perspective highlights that the value proposition of follow-on innovation is not theoretical but is underpinned by substantial empirical evidence of positive impact.

A closer examination of pharmaceutical R&D spending reveals a critical, often overlooked, aspect of innovation: a substantial portion of R&D costs, sometimes as high as 61% for certain drugs, are incurred after a drug’s initial FDA approval.2 Furthermore, a majority of clinical trials (ranging from 54% to 84% for some drugs) commence post-approval.2 This pattern indicates that pharmaceutical innovation is not a singular event culminating in the first drug approval but an ongoing, resource-intensive process of refinement, optimization, and expansion throughout a drug’s lifecycle. This suggests that the initial patent on the active ingredient alone is insufficient to incentivize the full spectrum of R&D that brings about these vital follow-on improvements. Therefore, patent protection for these subsequent innovations is not simply an “extension” of an old patent; it is a necessary incentive for

new and costly R&D that contributes substantially to a drug’s overall health impact.

IV. The Indispensable Role of Patent Protection

Patent protection is a cornerstone of the biopharmaceutical industry, providing the necessary framework to incentivize the immense investments required for medical innovation, ensure product quality, and attract essential capital. Its role extends critically to follow-on pharmaceutical innovations, which, despite their cumulative nature, demand substantial resources for development and validation.

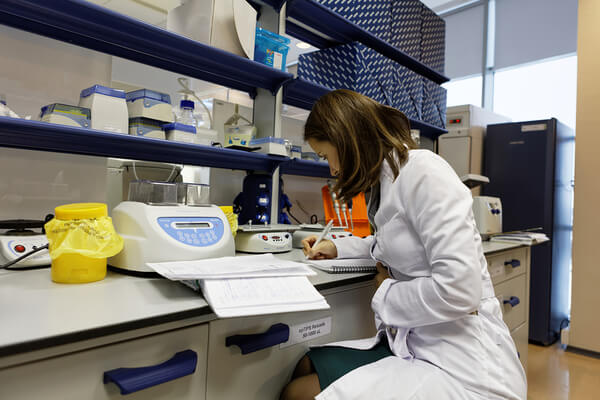

Incentivizing Research and Development

Pharmaceutical development is characterized by exceptionally high costs, lengthy timelines, and significant inherent risks. Bringing a new drug to market typically spans over a decade and can cost billions of dollars, with a high rate of attrition at various stages.4 Patents address this formidable challenge by granting a period of market exclusivity, generally 20 years from the filing date, during which the innovator can recoup these substantial investments.4 This exclusivity is paramount because, without robust patent protection, generic manufacturers could rapidly enter the market, significantly undercutting prices and eroding the innovator’s market share, thereby stifling future innovation and the willingness to undertake such risky ventures.21

The availability of patents for follow-on innovations is particularly vital. As previously noted, a substantial portion of R&D costs—up to 61% for some drugs and 54-84% of clinical trials—are incurred after the drug’s initial FDA approval.2 This post-approval investment is critical for developing new formulations, expanding indications, and enhancing safety. Without the incentive of “secondary” patents, many important drugs, such as AZT, might have remained promising but unfulfilled candidates, lacking the necessary investment to bridge the gap between initial discovery and a safe, effective, and FDA-approved pharmaceutical.16 Patents serve as a key motivator, providing a clear path to profitability that fuels the industry’s willingness to invest in new and risky ventures, encouraging continuous product refinement and pushing the boundaries of medical possibilities.21

The immense cost and inherent risk associated with pharmaceutical R&D, particularly for follow-on innovations, directly necessitate robust patent protection. The fact that a significant portion of R&D expenses are incurred after a drug’s initial approval indicates that patents on these subsequent innovations are not merely extending a monopoly. Instead, they are vital for recouping new investments in new research that delivers new patient benefits. Without this financial incentive, much beneficial post-approval R&D, crucial for optimizing therapies and expanding their utility, would likely not occur, ultimately depriving patients of improved treatment options.

Ensuring Quality and Safety Standards

Beyond their role in incentivizing R&D, patents play an indirect yet critical role in maintaining high safety and quality standards for pharmaceutical products.27 By granting exclusive rights, patents help control the market entry of potentially unsafe imitations, as unauthorized versions may not adhere to the stringent safety and manufacturing requirements established by the innovator.27 Patented drugs are typically produced under controlled, standardized conditions, ensuring consistent quality, which is fundamental for drug safety.27 The extensive scrutiny by regulatory agencies like the FDA during the approval process for patented drugs further ensures that only products meeting rigorous safety and efficacy standards reach the market.27

The exclusivity provided by patents also incentivizes companies to maintain vigilant post-market surveillance. This ongoing monitoring involves continuously tracking drug effectiveness, identifying and monitoring adverse reactions, and promptly addressing any safety concerns, thereby supporting comprehensive pharmacovigilance efforts.27 Furthermore, integrating safety considerations into the initial drug design process, such as developing drugs with inherent features like reduced toxicity or minimized side effects, can enhance a drug’s novelty and patentability. This encourages a proactive approach to safety from the very outset of drug development.7

The contribution of patents to ensuring drug safety and quality is a significant, though often less highlighted, benefit. This goes beyond mere economic incentive, directly linking patent protection to public health standards. This relationship implies that any weakening of patent protection for follow-on innovations could inadvertently compromise drug quality and reduce the incentive for rigorous post-market safety surveillance. Companies would have less motivation to invest in these crucial areas if their improvements and ongoing monitoring efforts could not be adequately protected, potentially leading to a less safe and reliable pharmaceutical supply.

Strategic Asset and Investment Attraction

In the highly competitive biopharmaceutical industry, intellectual property, particularly patents, transcends simple legal protection; it functions as a strategic business asset.8 A robust patent portfolio is essential for establishing and maintaining a competitive market position, effectively deterring competitors from developing and marketing similar products during the patent term.23 This competitive edge is paramount in an industry where a unique, patented product can secure significant market share and revenue.23

Patents serve as tangible evidence of an invention’s uniqueness and potential market value, which is crucial for attracting and securing investment, including venture capital, especially for early-stage development.3 They provide investors with the necessary assurance of market exclusivity and a clear pathway to profitability, making a company a more attractive investment opportunity.23 Patents can even be leveraged as collateral in financing arrangements, providing a tangible asset against which companies can borrow.23 Strategic patent filing and continuous monitoring of competitor patent activities are critical practices for anticipating market shifts, identifying potential threats, and optimizing R&D investments to maintain a competitive advantage.8

V. Navigating Patentability Criteria for Follow-On Innovations

The eligibility of follow-on pharmaceutical innovations for patent protection hinges on their ability to satisfy stringent patentability criteria, which are designed to ensure that only genuine advancements are granted exclusive rights. While the fundamental principles are broadly consistent across major jurisdictions, their application to incremental drug improvements presents nuanced interpretations and challenges.

Core Patentability Requirements

For any invention to be patentable, it must generally meet three fundamental criteria: Novelty, Inventive Step (Non-Obviousness), and Utility/Industrial Application.1 These requirements are applied to “secondary” inventions—such as follow-on pharmaceutical innovations—in the same rigorous manner as they are to their “primary” counterparts, ensuring that only true improvements receive protection.1

The inventive step criterion, in particular, is crucial. It is designed to ensure that patent rights are granted solely to creations that genuinely advance technology or provide significant economic benefits, demonstrating a creative leap that would not be obvious to a person with ordinary skill in the relevant technical field.32 This criterion prevents the monopolization of obvious ideas and actively promotes genuine innovation by demanding a measurable technical advancement, economic significance, and a non-obvious solution to a technical problem.32

Application in the United States

The United States patent system, governed by Title 35 of the U.S. Code, outlines specific requirements for patentability.

- Legal Framework:

- Patentable Subject Matter (35 U.S.C. 101): This statute permits patents for “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof”.29 It also includes provisions to prohibit statutory double patenting, preventing two patents from issuing on identical subject matter to the same inventive entity.29

- Novelty (35 U.S.C. 102): An invention is considered novel unless it was patented, described in a printed publication, in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date.33 Importantly for pharmaceuticals, a new use for an old invention does not render the old invention patentable

per se, but the new use itself might be patentable, particularly for repurposing existing drugs.34 Demonstrating this often requires elucidating and disclosing mechanistic information to prove the new use is truly novel.34 - Non-Obviousness (35 U.S.C. 103): An invention must not have been obvious at the time it was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art (PSITA).36 The assessment considers the scope and content of prior art, the differences between the invention and prior art, the level of ordinary skill, and secondary considerations such as commercial success or long-felt needs.36 The Supreme Court’s

KSR decision broadened the inquiry into obviousness, moving away from a rigid “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” (TSM) test.37 - Utility (35 U.S.C. 101): The invention must be “useful”.38 For inventions claiming pharmacological or therapeutic utility, federal courts have consistently reversed rejections where an applicant provides evidence that reasonably supports such utility.39 This evidence can include statistically relevant data, logical arguments, documentary evidence (e.g., scientific articles), or a combination thereof. It is generally not required to provide actual human clinical data; data from

in vitro assays or animal testing is typically sufficient if it demonstrates a reasonable correlation to the asserted utility.39 - Key Court Decisions and Interpretations for Follow-On Innovations:

- New Formulations (e.g., Salt Forms, Polymorphs): In Valeant Pharmaceuticals International v. Watson Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the Federal Circuit affirmed the validity of patents covering a specific salt formation of the antidepressant bupropion, finding it non-obvious. The court emphasized the “general rule” that salt selection is an unpredictable art, distinguishing the case from situations where prior art clearly taught the modification. It also rejected arguments based on “after-the-fact testing” as a basis for obviousness.12 Similarly, in

Grunenthal GmbH v. Alkem Laboratories Ltd., the Federal Circuit upheld the non-obviousness of a specific polymorph (Form A) of tapentadol hydrochloride. The court determined there was no “reasonable expectation of success” in producing Form A, as the prior art, though providing general guidance on polymorph screening, lacked specific instructions for achieving particular polymorphs. The discovery was not considered “obvious to try” given the multitude of variables without specific enabling methodology.20 - New Indications and Methods of Use: New-use patents constitute a significant portion of pharmaceutical patents, allowing companies to repurpose existing drugs.35 The challenge lies in proving the new use is genuinely novel, often requiring detailed mechanistic information.34 The Hatch-Waxman Act allows generic manufacturers to “carve out” indications covered by method-of-use patents from their labels (“section viii carveouts”) to facilitate generic entry for non-patented uses.40 However, recent Federal Circuit decisions, such as those involving

GSK v. Teva and Amarin v. Hikma, have held generics liable for inducing infringement of method-of-use patents even with carved-out indications, if other marketing activities actively encourage the patented use. This creates a complex landscape for generic entry.40 Patents can also be infringed when a known substance is used for a new application that is objectively recognizable, for instance, through labeling, and can be based on the discovery of previously unknown properties, such as a superior therapeutic effect in a specific patient group.41 - New Dosage Forms and Regimens: In Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., the Federal Circuit upheld the non-obviousness of a specific dosing regimen for paliperidone palmitate. The court rejected the presumption of obviousness for overlapping prior art ranges, determining that the claimed invention included a unique combination of intertwined elements—such as specific timing of doses, the nature of loading doses, and decreasing amounts from the first to second dose—that distinguished it from the prior art. The court emphasized the importance of expert testimony in demonstrating a lack of motivation to combine prior art elements and no reasonable expectation of success.13 A non-precedential decision in

Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Mylan Laboratories similarly upheld the non-obviousness of a dosing regimen for treating a missed dose, reinforcing the requirement for challengers to demonstrate both motivation and a reasonable expectation of success.14

Application in the European Union

The European Patent Office (EPO) applies the European Patent Convention (EPC) to assess patentability.

- EPO Guidelines (Problem-and-Solution Approach for Inventive Step): The EPO employs the “problem-and-solution approach” to assess inventive step (Article 56 EPC).42 This structured method involves three steps: 1) identifying the closest prior art, which is the most promising starting point for the invention; 2) defining the objective technical problem, which is the technical effect achieved by the distinguishing features of the claimed invention; and 3) examining whether the claimed solution to this problem would have been obvious to a person skilled in the art in view of the general state of the art.42 For

pharmaceutical formulations, a “surprising technical advantage” is often a prerequisite for demonstrating inventive step. This advantage can manifest as improved pharmacokinetics, enablement of a different administration route, enhanced patient compliance, reduced side effects, or decreased dosage frequency.44 Evidence of overcoming specific technical challenges during development or the use of unusual excipients can also support inventiveness.44 The submission of comparative data demonstrating the benefit over known formulations is highly advisable and significantly improves the chances of securing protection.44 - Novelty (Article 54(2) EPC): The “state of the art” is broadly defined as “everything made available to the public by means of a written or oral description, by use, or in any other way” before the patent’s filing date.45 Public prior use, such as information disclosed during clinical trials, can constitute prior art if it is clearly and convincingly proven to have been accessible to the public.45

- Relevant Case Law for Follow-On Innovations:

- Pharmaceutical Formulations: In EPO case T 1617/28 concerning a ritonavir solid dispersion, the Board of Appeal found claims to a solid pharmaceutical dosage form comprising ritonavir and specific excipients to meet EPC requirements. The inclusion of a surfactant with a particular HLB value, combined with other preferred features, was considered by the skilled person to lead to enhanced bioavailability, thereby supporting inventiveness.46 A general principle in Europe is that if a new formulation yields an unexpected benefit, it can create opportunities for additional patent protection, even if the active ingredient is already known.44

- Dosage Regimens: In the appeal proceedings on EP 3199172 concerning a glatiramer acetate dosage regimen, the EPO Board found that the claimed regimen (three 40mg injections per week) lacked inventive step. The Board considered the difference from prior art to be “minor” and “obvious to try” because it offered a desirable patient benefit (e.g., weekends without injections) and there was an overlap in patient groups. Crucially, no comparative data was provided to demonstrate an unexpected effect of this specific difference.15 This case underscores the necessity of demonstrating a clear technical effect and providing supporting data for dosage regimen claims. Conversely, claims to a once-daily combination therapy of umeclidinium and vilanterol for COPD/asthma were upheld, as the application as filed provided a “strong presumption” of effectiveness and feasibility for once-daily administration, corroborated by a post-published document.15

- Second Medical Use Claims: These claims protect the use of a known substance or composition for a new and specific medical purpose.47 They are patentable under Article 54(5) EPC, provided the new use is both novel and inventive.47 The claimed use must clearly demonstrate a departure from the first-use invention, not merely be lexically different, and must reflect a distinct and inventive effect.47 Experimental data provided in the application as filed is crucial for proving the claimed therapeutic effect.47

International Perspectives

Patent laws exhibit significant variations across different countries, making global intellectual property protection a complex undertaking.30 While the TRIPS Agreement mandates certain minimum levels of patent protection, it explicitly prohibits subject matter-specific heightened patentability requirements, emphasizing a non-discriminatory approach.16

- India: The Indian Patents Act, particularly Section 3(d), takes a stricter stance on “evergreening.” It generally disallows patents for new forms of known substances unless they demonstrate a significant enhancement in therapeutic efficacy.4 Furthermore, the Act explicitly states that fresh patents will typically not be granted for new indications for drug use.50 This reflects a deliberate policy choice to prioritize public access to affordable medicines, often leading to a more challenging environment for patenting incremental innovations compared to some other jurisdictions.

- Canada: In Canada, methods of medical treatment are generally not patentable. However, “Swiss-style” and “German-use” claims, which focus on the use of a known substance for a new medical purpose, are permitted.51 Additionally, Canada offers data exclusivity and Certificates for Supplemental Protection (CSPs) which can extend the effective patent life for new drug submissions or supplements involving changes in formulation, dosage form, or use of the medicinal ingredient.51

- Australia: Australian patent law requires inventions to be new, useful, inventive, and a suitable subject matter.31 While standard patents have a term of 20 years, pharmaceutical patents can extend up to 25 years.31 Patent term extensions of up to 5 years are available for pharmaceutical substances

per se and formulations, but notably not for second medical use claims.54 This distinction highlights a jurisdictional difference in how extensions are applied to different types of follow-on innovation.

Table 2: Comparative Patentability Criteria for Follow-On Innovations (US vs. EU)

| Criterion | United States Approach | European Union Approach | Key Differences/Nuances |

| Novelty | 35 U.S.C. 102: Invention must not be publicly known, used, or patented prior to filing. New use for old invention can be patentable if the use itself is novel and mechanistic information is provided.33 | Art. 54 EPC: “Everything made available to the public” before filing. Public prior use (e.g., clinical trials) can destroy novelty if clearly proven.45 | Both require absolute novelty. US allows new-use patents on old compounds if the use is novel; EU has specific “first/further medical use” claims. |

| Inventive Step (Non-Obviousness) | 35 U.S.C. 103: Not obvious to a Person of Ordinary Skill in the Art (PSITA) at time of invention. Considers prior art, differences, PSITA level, secondary considerations. KSR broadened inquiry beyond rigid TSM test.36 “Obvious to try” is considered if there’s a finite number of predictable solutions. | Art. 56 EPC: “Problem-and-Solution Approach.” Requires a “surprising technical advantage” for formulations. Emphasis on objective technical problem and non-obvious solution.42 “Obvious to try” is applied more strictly, requiring a clear expectation of success, not just motivation.56 | US has a more flexible “obvious to try” standard post-KSR. EU often requires “surprising technical advantage” or overcoming technical challenges for incremental improvements, with strong emphasis on supporting data in the application.15 |

| Utility/Industrial Application | 35 U.S.C. 101: Invention must be “useful.” For therapeutic utility, “reasonable correlation” between evidence (in vitro, animal data, arguments) and asserted utility is sufficient; human clinical data not always required.38 | Art. 57 EPC: Invention must be capable of industrial application. Generally, a therapeutic effect is considered industrially applicable. | Similar broad requirements. US case law provides more specific guidance on evidence for therapeutic utility.39 |

| Specific Types of Follow-on Innovation | |||

| Formulations | Patentable if novel, non-obvious (e.g., Valeant on bupropion salt for stability).12 | Patentable if “surprising technical advantage” (e.g., improved pharmacokinetics, patient compliance, reduced side effects).44 Requires strong data. | Both require more than trivial changes. EU explicitly looks for “surprising technical advantage.” |

| New Uses/Indications | New-use patents common (e.g., repurposing old drugs). “Skinny labels” and induced infringement litigation are complex areas.34 | “First/further medical use” claims (Art. 54(4)/(5) EPC) are patentable if novel and inventive. Requires experimental data in application.47 | US allows method-of-use claims broadly. EU has specific “purpose-limited product claims” for medical uses, requiring clear therapeutic effect. |

| Dosage Regimens | Patentable if non-obvious, often requiring unique combination of elements and expert testimony (e.g., Janssen cases).13 | Challenging to obtain. Require credible efficacy at filing date and often comparative data to show unexpected effect (e.g., EP 3199172 showing lack of inventive step without comparative data).15 | US focuses on non-obviousness of the regimen as a whole. EU has strict requirements for supporting data and demonstrating unexpected effects for inventive step. |

| Polymorphs/Salt Forms | Patentable if non-obvious, especially if unpredictable (e.g., Grunenthal on tapentadol polymorph due to unpredictability).12 | Patentable if “unexpected properties” (e.g., improved hygroscopicity or chemical stability).56 Routine screening for polymorphs typically not inventive without unexpected property.56 | Both jurisdictions require unexpected properties or unpredictability to overcome obviousness. |

While the core patentability requirements (novelty, non-obviousness, and utility) are universally applied, their practical application to follow-on pharmaceutical innovations varies significantly across jurisdictions. For example, India’s Section 3(d) explicitly targets evergreening by demanding a “significant enhancement in therapeutic efficacy” for new forms of known substances to be patentable.4 In contrast, US courts have demonstrated a more limited resistance to such secondary patents, unless a clear lack of novelty or obviousness is proven.57 This divergence creates a complex global landscape for pharmaceutical companies, influencing where certain types of follow-on R&D might be prioritized. This suggests that a one-size-fits-all policy approach to follow-on patents is impractical, necessitating a tailored intellectual property strategy in different markets.

Furthermore, court decisions and patent office guidelines consistently emphasize the need for unexpected properties or technical advantages and often require comparative data to establish inventive step or non-obviousness for follow-on innovations.12 This trend indicates a rigorous judicial and regulatory scrutiny of the

substantive benefit of follow-on innovations, moving beyond mere structural changes. This approach directly addresses common criticisms that these innovations are “trivial” modifications. This judicial and regulatory emphasis on demonstrable benefit compels innovators to pursue genuinely valuable follow-on R&D to secure patents, thereby enhancing the overall quality of innovations that ultimately reach the market.

VI. Addressing Criticisms: Evergreening and Access Concerns

The debate surrounding patent protection for follow-on pharmaceutical innovations is often intertwined with concerns about “evergreening” and its perceived impact on drug affordability and patient access. A balanced understanding requires examining these criticisms alongside the inherent complexities of pharmaceutical innovation and market dynamics.

The “Evergreening” Debate

“Evergreening” refers to a contentious strategy employed by pharmaceutical companies to extend the commercial exclusivity of their products beyond the original patent term.4 This is typically achieved by securing new patents on minor modifications, such as novel formulations, new uses, adjusted dosages, or alternative delivery methods.4

Critics argue that evergreening exploits legal loopholes, primarily to delay the entry of generic alternatives, inflate drug prices, and undermine access to affordable medicines, particularly in developing countries where affordability is a critical determinant of access.57 This often involves the creation of “patent thickets”—multiple patents surrounding a single drug—which can complicate and delay generic approvals, leading to prolonged and expensive legal battles for generic manufacturers.57 Some academic perspectives suggest that firms sometimes modify existing drugs primarily to maintain market power through “product hopping” rather than to demonstrably improve health outcomes, which is seen as running counter to the legislative goal of incentivizing discoveries that elevate patient care.61

Conversely, proponents of evergreening contend that these practices represent legitimate incremental innovation deserving of protection. They argue that these modifications can offer real benefits, such as reduced side effects, improved efficacy, or enhanced patient convenience, and that the profits generated from extended patents fund further drug research and development.57 The distinction between genuine innovation and strategic patenting, therefore, often remains a blurred line.57

Balancing Innovation with Public Health and Affordability

The patent system is fundamentally designed to strike a delicate balance between incentivizing innovation through temporary monopolies and ensuring public access to affordable medicines once patent protection expires.4

- Regulatory Exclusivity: In addition to patent protection, regulatory exclusivities granted by bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Union (EU) also provide periods of market protection. In the U.S., these include 5-year New Chemical Exclusivity, 3-year “Other” exclusivity for certain changes, and 6-month Pediatric Exclusivity.62 In the EU, a new medicinal product typically enjoys 8 years of data protection followed by 2 years of market exclusivity, with potential additional years for new therapeutic indications or unmet medical needs.44 These exclusivities can run concurrently with or independently of patents and are specifically designed to promote a balance between new drug innovation and generic drug competition.62

- Policy Adjustments: Legislative bodies continually review and adjust these frameworks. Recent EU proposals, for instance, aim to revise the regulatory exclusivity framework, potentially reducing the overall duration of exclusivity for innovator companies to encourage earlier generic/biosimilar entry.44 This ongoing legislative effort highlights a dynamic process of recalibrating the balance between incentivizing innovation and promoting access.

- Addressing Misuse: Instances of patent misuse that result in restricted access to unprotected medicines are intended to be addressed directly through existing legal mechanisms. These include competition laws and antitrust doctrines.1 “Pay-for-delay” agreements, where originator companies compensate generic manufacturers to delay market entry, have been legally challenged as anti-competitive practices.57 Furthermore, the “Bolar” exemption, present in patent laws in jurisdictions like the EU and US, allows generic manufacturers to use patented inventions for studies and trials necessary to obtain market authorization

before patent expiration, thereby facilitating earlier generic entry immediately upon patent expiry.25 - Alternative Perspectives: Some academic arguments propose that pharmaceutical innovation could, and in some cases should, proceed without patents, suggesting regulatory exclusivity as a more tailored replacement.64 This perspective often points out that clinical trial expenditures comprise the lion’s share of drug development costs (around 70%), implying that incentives for data generation are paramount, regardless of whether they are provided by patents or regulatory exclusivities.64

The “evergreening” debate encapsulates a fundamental tension: what some stakeholders view as legitimate incremental innovation, others perceive as strategic market manipulation. However, the presence of robust judicial and regulatory mechanisms—such as India’s Section 3(d) requiring “significant therapeutic improvement,” rigorous US court scrutiny on obviousness, antitrust challenges to anti-competitive agreements like “pay-for-delay,” and evolving EU regulatory exclusivity frameworks—demonstrates that the system is actively attempting to address potential abuses, rather than being entirely permissive. This suggests that the appropriate response is not to abolish patent protection for follow-on innovations, but rather to strengthen the application of existing patentability criteria and competition laws to ensure that only truly inventive and beneficial advancements are rewarded with exclusivity.

The ongoing discussion concerning regulatory exclusivity versus patent protection reveals a deeper policy challenge: how to effectively balance the imperative for innovation incentives with the critical need for affordable access to medicines. The argument that the pharmaceutical industry might not need patents, as presented in some analyses, raises a crucial counterpoint that must be thoughtfully considered. However, even if one argues against the specific mechanism of patent protection, the substantial cost of clinical trials, which constitutes the “lion’s share” of pharmaceutical R&D, necessitates some form of market exclusivity to recoup these significant data-generation costs.64 This reframes the debate from a simple “patents or no patents” dichotomy to a more nuanced question of “what

type of exclusivity is best suited to incentivize costly, beneficial innovation, including follow-on advancements, while simultaneously managing issues of affordability and access?” This understanding leads to a more comprehensive approach, acknowledging that the core problem is incentivizing high-cost R&D, and patents, despite their imperfections, remain a proven mechanism for achieving this.

VII. Conclusion: The Imperative for Robust Patent Protection

Follow-on pharmaceutical innovations are not merely peripheral enhancements; they are integral to the continuous advancement of patient care, public health, and the efficiency of healthcare systems. As detailed throughout this report, these innovations encompass a wide spectrum of improvements—from enhanced formulations and novel delivery methods to expanded therapeutic applications and improved safety profiles—each demanding significant investment and ingenuity. They transform existing therapies into more effective, safer, and patient-friendly options, leading to improved adherence, reduced healthcare costs, and better overall health outcomes. The notion that these are trivial modifications is contradicted by the extensive R&D investments, particularly post-initial approval, and the rigorous patentability standards they must meet.

Robust patent protection is therefore indispensable for sustaining this vital stream of innovation. It provides the critical incentive for pharmaceutical companies to undertake the immense financial risks and lengthy timelines associated with R&D, ensuring that investments in new and improved therapies are recouped. Furthermore, patents play a crucial role in maintaining high standards of quality and safety by controlling market entry and incentivizing ongoing post-market surveillance. They also serve as a strategic asset, attracting the necessary investment for early-stage development and fostering a competitive environment driven by continuous improvement.

While the practice of “evergreening” and its implications for drug affordability and generic competition are legitimate concerns, the solution does not lie in undermining the fundamental principle of patent eligibility for follow-on innovations. Instead, the focus must be on strengthening the existing intellectual property framework and its complementary regulatory and competition laws.

To foster a balanced and effective intellectual property system that supports both innovation and access, the following recommendations are put forth:

- Maintain Rigorous Application of Patentability Criteria: Patent offices and courts must continue to apply stringent standards of novelty, inventive step (non-obviousness), and utility. This ensures that only genuinely inventive follow-on innovations that demonstrate a substantive technical advantage or unexpected property are granted patent protection, thereby filtering out trivial modifications.

- Strengthen Competition Laws and Regulatory Oversight: Proactive measures and enforcement of antitrust laws are essential to address patent misuse and anti-competitive practices, such as “pay-for-delay” agreements. Regulatory bodies should continue to leverage mechanisms like the “Bolar” exemption to facilitate timely generic entry where appropriate, balancing innovator incentives with public access.

- Foster Transparency in Patent Information and Clinical Trial Data: Increased transparency regarding patent filings, their scope, and the clinical data supporting new indications or formulations can empower regulators, payers, and patients to make more informed decisions about drug value and market dynamics.

- Encourage Global Harmonization of Patent Standards (where appropriate): While respecting national public health priorities and unique legal frameworks, international cooperation can help streamline patent processes and reduce complexities for innovators seeking global protection, potentially leading to more efficient R&D and broader access.

- Recognize and Value the Cumulative Nature of Pharmaceutical R&D: Policy discussions should acknowledge that innovation is an ongoing process throughout a drug’s lifecycle. Follow-on innovations are not merely an afterthought but are integral to realizing a drug’s full therapeutic potential and addressing evolving patient needs. An intellectual property system that incentivizes these continuous improvements is essential for advancing global health.

By upholding robust patent protection for valuable follow-on pharmaceutical innovations, while simultaneously enhancing oversight and promoting transparency, society can continue to benefit from a dynamic and responsive pharmaceutical industry that delivers increasingly effective, safer, and more accessible treatments to patients worldwide.

Works cited

- Medicines – In Support of Follow-On Innovation | Van Bael & Bellis, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.vbb.com/insights/corporate-commercial-regulatory/medicines-in-support-of-follow-on-innovation

- The Value of Follow-On Biopharma Innovation for Health Outcomes and Economic Growth, accessed July 23, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/03/17/the-value-of-follow-on-biopharma-innovation/

- Why Follow-On Pharmaceutical Innovations Should Be Eligible For Patent Protection, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/why-follow-on-pharmaceutical-innovations-should-be-eligible-for-patent-protection-2/

- What is the process of expanding a drug patent by changing the molecule (or formulation etc.) called again? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 23, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-the-process-of-expanding-a-drug-patent-by-changing-the-molecule-or-formulation-etc-called-again

- 7 Ways Value-Added Medicines Are Improving Patient Outcomes – Laboratorios Rubió, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.laboratoriosrubio.com/en/value-added-medicines/

- New Drug Formulations and Their Respective Generic Entry Dates – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 23, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10398232/

- Safety first: Patenting with drug safety and side effects in mind – PatentPC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patenting-with-drug-safety-side-effects

- Patent Considerations for Novel Drug Delivery Systems – PatentPC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-consideration-for-novel-drug-delivery-system

- Pharmacology & Drug Delivery System Patents, accessed July 23, 2025, https://hpgww.com/pharmacology-drug-delivery-system-patents/

- Drug Delivery Research Aims to Improve Treatment Outcomes, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.pcom.edu/academics/programs-and-degrees/doctor-of-pharmacy/school-of-pharmacy/school-of-pharmacy-news/drug-delivery-research-aims-to-improve-treatment-outcomes.html

- The Future of Drug Delivery | Chemistry of Materials – ACS Publications, accessed July 23, 2025, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c03003

- Validity affirmed for patents related to salt formation – – Carlson Caspers, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.carlsoncaspers.com/validity-affirmed-for-patents-related-to-salt-formation/

- Janssen v. Teva: Federal Circuit Upholds Claims to Pharmaceutical …, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.cooley.com/news/insight/2025/2025-07-11-janssen-v-teva-federal-circuit-upholds-claims-to-pharmaceutical

- The Federal Circuit upholds drug dosing regimen as valid and nonobvious | DLA Piper, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.dlapiper.com/insights/publications/synthesis/2025/the-federal-circuit-upholds-drug-dosing-regimen-as-valid-and-nonobvious

- Dosage regimen patents at the EPO part (II): Recent case law …, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.kilburnstrode.com/knowledge/european-ip/dosage-regimen-patents-epo-part-ii-recent-case-law

- Inside Views: Why Follow-On Pharmaceutical Innovations Should Be Eligible For Patent Protection, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.vbb.com/media/Insights_Articles/Why_Follow-On_Pharmaceutical_Innovations_Should_Be_Eligible_For_Patent_Protection_-_Intellectual_Property_Watch.pdf

- Incremental drug innovation means more therapeutic options with “great impact” on patients’ lives and on the healthcare system, accessed July 23, 2025, https://distefar.com/incremental-drug-innovation-means-more-therapeutic-options-with-great-impact-on-patients-lives-and-on-the-healthcare-system/

- The Benefits of Incremental Innovation: Focus on the Pharmaceutical Industry – Fraser Institute, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/benefits-of-incremental-innovation.pdf

- Evidence that innovative medicines improve health and economic outcomes, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.canadianhealthpolicy.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/download_87.pdf

- Are polymorph patents necessarily obvious? A recent CAFC …, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.markmanadvisors.com/blog/2019/3/29/are-polymorph-patents-necessarily-obvious-a-recent-cafc-decision-may-read-through-to-revlimids-polymorph-patents

- The Influence of Patent Law on Biopharmaceutical Innovation – PatentPC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/the-influence-patent-law-biopharmaceutical-innovation

- The Economics of Pharmaceutical Innovation, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/economics-pharmaceutical-innovation

- Managing Patent Portfolios in the Pharmaceutical Industry – PatentPC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/managing-patent-portfolios-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- Drug Pricing and the Law: Pharmaceutical Patent Disputes – Congress.gov, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF11214

- Filing Strategies for Maximizing Pharma Patents: A Comprehensive Guide for Business Professionals – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/filing-strategies-for-maximizing-pharma-patents/

- The Role of Patents in Biopharmaceutical Drug Safety – PatentPC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/role-of-patents-in-drug-safety

- How to Track Competitor R&D Pipelines Through Drug Patent Filings, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-track-competitor-rd-pipelines-through-drug-patent-filings/

- 2104-Requirements of 35 U.S.C. 101 – USPTO, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2104.html

- How International Patent Laws Differ: A Comparative Study – PatentPC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/how-international-patent-laws-differ-a-comparative-study

- What are patents? | IP Australia, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/patents/what-are-patents

- Unlocking the Inventive Step: The Heart of Patentable Innovation, accessed July 23, 2025, https://thelaw.institute/patents/inventive-step-patentable-innovation-heart/

- MPEP 1504.02: Novelty, November 2024 (BitLaw), accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.bitlaw.com/source/mpep/1504-02.html

- Patenting New Uses for Old Inventions – Vanderbilt University, accessed July 23, 2025, https://cdn.vanderbilt.edu/vu-wordpress-0/wp-content/uploads/sites/278/2020/03/19115836/Patenting-New-Uses-for-Old-Inventions.pdf

- Patenting New Uses for Old Inventions – Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law, accessed July 23, 2025, https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2919&context=vlr

- Non-obviousness: Exploring a Patent, the MPEP, and the Patent Bar, accessed July 23, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/non-obviousness-exploring-a-patent-the-mpep-and-the-patent-bar

- Nonobviousness in the U.S. Post-KSR for Innovative Drug Companies | Articles | Finnegan, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/nonobviousness-in-the-u-s-post-ksr-for-innovative-drug-companies.html

- What’s the Use of the Patent Strict Utility Requirement – University of Alabama School of Law, accessed July 23, 2025, https://law.ua.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Whats-the-Use-of-the-Patent-Strict-Utility-Requirement.pdf

- MPEP 2107.03 Special Considerations for Asserted Therapeutic or Pharmacological Utilities, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.bitlaw.com/source/mpep/2107-03.html

- Will the Supreme Court save lower-cost medications from inducement by skinny labels?, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.markmanadvisors.com/blog/2025/6/26/will-the-supreme-court-save-lower-cost-medications-from-inducement-by-skinny-labels

- Recent Court Decision on (i) Scope of Medicinal Use Invention and (ii) Patent Linkage, accessed July 23, 2025, https://chambers.com/articles/recent-court-decision-on-i-scope-of-medicinal-use-invention-and-ii-patent-linkage

- Inventive step under the European Patent Convention – Wikipedia, accessed July 23, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inventive_step_under_the_European_Patent_Convention

- Part 1: Inventive step at the EPO – Abel + Imray, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.abelimray.com/resources/newsletters/part-1-inventive-step-at-the-epo

- EU regulatory exclusivity changes: The increasing importance of …, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.kilburnstrode.com/Knowledge/European-IP/EU-regulatory-exclusivity-changes

- How the EPO addresses public prior use in clinical trials and patentability obstacles for pharmaceutical inventions – COHAUSZ & FLORACK, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.cohausz-florack.de/en/blog/article/how-the-epo-addresses-public-prior-use-in-clinical-trials-and-patentability-obstacles-for-pharmaceutical-inventions/

- T 1728/16 (Solid pharmaceutical dosage form comprising ritonavir / ABBOTT) 15-11-2019 | epo.org, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/boards-of-appeal/decisions/t161728eu1

- The continuing debate over second medical use patents | Dennemeyer.com, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.dennemeyer.com/ip-blog/news/the-continuing-debate-over-second-medical-use-patents/

- 6.1 First or further medical use of known products – European Patent Office, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/legal/guidelines-epc/2025/g_vi_6_1.html

- Pharmaceutical Patenting in India | candcip, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.candcip.com/pharmaceutical-patenting-in-india

- The new patent regime: Implications for patients in India – PMC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2900001/

- Patenting Chemical Inventions in Canada: Advantages and Special Considerations, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.marks-clerk.com/insights/latest-insights/102jvzs-patenting-chemical-inventions-in-canada-advantages-and-special-considerations/

- Prohibiting Medical Method Patents: A Criticism of the Status Quo – Schulich Law Scholars, accessed July 23, 2025, https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/cjlt/vol9/iss1/9/

- Guidance Document: Patented Medicines (Notice of Compliance) Regulations – Canada.ca, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/patented-medicines/notice-compliance-regulations.html

- Substance over form(ulations)? An update on patent term extensions – KWM Pulse Blog, accessed July 23, 2025, https://pulse.kwm.com/ip-whiteboard/substance-over-formulations-an-update-on-patent-term-extensions/

- Pharmaceutical Patent Term Extensions | Not available for second medical use claims, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.gestalt.law/insights/pharmaceutical-patent-term-extensions-not-available-for-second-medical-use-claims

- 9.9.5 Predictable improvements resulting from amorphous forms as compared to crystalline forms – European Patent Office, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/legal/case-law/2022/clr_i_d_9_9_5.html

- Patent Evergreening In The Pharmaceutical Industry: Legal Loophole Or Strategic Innovation? – IJLSSS, accessed July 23, 2025, https://ijlsss.com/patent-evergreening-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-legal-loophole-or-strategic-innovation/

- Biopharmaceutical Patenting: The Controversy Over Evergreening | PatentPC, accessed July 23, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patenting-the-controversy-over-evergreening

- Evergreen Drug Patent Database – UC College of the Law, accessed July 23, 2025, https://sites.uclawsf.edu/evergreensearch/

- The impact of an ‘evergreening’ strategy nearing patent expiration on the uptake of biosimilars and public healthcare costs: a case study on the introduction of a second administration form of trastuzumab in The Netherlands, accessed July 23, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11377641/

- The More Things Change: Improvement Patents, Drug Modifications, and the FDA – Iowa Law Review, accessed July 23, 2025, https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/sites/ilr.law.uiowa.edu/files/2023-02/Karshtedt.pdf

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- EU pharma law reform moves closer – Pinsent Masons, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/eu-pharma-law-reform-moves-closer

- Does Pharma Need Patents? – The Yale Law Journal, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/feature/does-pharma-need-patents