Executive Summary

The generic pharmaceutical industry stands at a pivotal juncture, transitioning from a high-volume, cost-driven operational model to a sophisticated, value-centric ecosystem defined by strategic collaboration. This transformation is not a matter of choice but a strategic imperative, compelled by a confluence of relentless economic pressures, escalating product complexity, and disruptive technological innovation. The traditional paradigm—where success was predicated on rapid reverse-engineering and manufacturing scale—is proving increasingly unsustainable. Intense price erosion, driven by consolidated buyers and hyper-competition, has compressed margins to untenable levels for conventional products. Simultaneously, the next wave of major patent expiries is dominated by complex biologics and high-barrier generics, demanding scientific, manufacturing, and regulatory capabilities far beyond the scope of the traditional generic enterprise.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the forces reshaping the industry and details the future of partnerships as the central pillar of success in this new landscape. The analysis reveals that collaboration is no longer a tactical option for outsourcing non-core functions but has become the primary engine for accessing innovation, mitigating risk, and achieving sustainable growth. The roles of external partners, particularly Contract Research Organizations (CROs) and Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs), have evolved from transactional service providers to indispensable strategic allies, offering end-to-end development expertise that functions as an external R&D brain for generic firms.

For high-value opportunities like biosimilars, a multi-partner “alliance ecosystem” is now the requisite model for market entry, combining specialized expertise in cell-line development, clinical trial management, advanced manufacturing, and regional commercialization. Furthermore, technological catalysts such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and continuous manufacturing are creating a new competitive dimension based on information superiority and production efficiency, accessible to most only through collaborative consortia and technology partnerships.

Navigating this new terrain requires a fundamental shift in the capabilities of generic firms, demanding sophisticated skills in deal-making, alliance management, and the architecture of complex legal and financial frameworks. Success in the coming decade will be defined not by what a company owns, but by the ecosystem of partners it can effectively orchestrate. This report offers a strategic blueprint for this future, outlining the key attributes of the successful generic firm of 2030 and providing actionable recommendations for developers, their partners, and policymakers to build a resilient, innovative, and collaborative ecosystem that ensures continued patient access to affordable, high-quality medicines.

Section 1: The Imperative for Collaboration: Deconstructing the Modern Generics Landscape

The foundational logic of the generic drug industry—providing low-cost alternatives to branded medicines upon patent expiry—has created immense value for global healthcare systems. However, the very success of this model has engendered a series of profound structural challenges. A perfect storm of intense price competition, shifting market dynamics, and fragile global supply chains has eroded the profitability of traditional generic products, forcing a strategic re-evaluation across the sector. In this environment, the go-it-alone strategies of the past are no longer viable. Collaboration has emerged not as a choice, but as a necessary adaptation to survive and thrive. This section deconstructs the key economic, competitive, and logistical pressures that form the imperative for a partnership-centric future.

1.1 The Economics of Erosion: Analyzing the Unrelenting Pressure on Profitability

The economic model for traditional generic drugs is caught in a pernicious downward spiral.1 While demand for generics remains robust, representing nine out of every ten prescriptions in the United States, the profitability of supplying this demand is under severe and escalating pressure.2 The core of this challenge lies in the direct and predictable relationship between market competition and price decay.

The expedited generic drug approval process, streamlined by legislation like the Hatch-Waxman Act, is designed to accelerate the entry of multiple competitors into a market following the loss of exclusivity for a reference drug.1 While beneficial for payers and patients, this influx of suppliers often outstrips demand, triggering aggressive price competition.1 The resulting price erosion is both rapid and severe. Empirical data consistently shows that generic drug prices fall precipitously as more manufacturers enter the market. The entry of approximately three competitors can lead to a price decline of 20% relative to the pre-entry price. In markets with ten or more competitors, prices can plummet by as much as 70% to 80% within three years of the first generic launch.4 This price decay follows a predictable scalloped curve, eventually flattening out at a level that can be as low as 20% of the original brand price.5

This “race to the bottom” dynamic is further intensified by the consolidated purchasing power of a few large drug buyers, which will be discussed in greater detail later in this section.6 The consequence of these unrelenting pricing pressures is a significant decrease in manufacturer profitability. As margins become wafer-thin, many companies find it financially unviable to continue producing certain drugs, leading them to exit markets entirely.1 This market consolidation, paradoxically, can then lead to supply disruptions and drug shortages, particularly for smaller-market oral solids and complex injectable products, where the economic incentives for maintaining a multi-source supply are weakest.7 From 2004 to 2016, a striking 40% of generic drug markets were supplied by a single manufacturer, highlighting that the image of generics as a simple, hyper-competitive commodity is a significant oversimplification.7 This cycle of intense competition leading to market exits and subsequent supply instability underscores a fundamental vulnerability in the traditional generic business model.

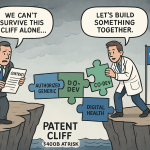

1.2 Beyond the Cliff: How Patent Expiries Create Both Opportunity and Volatility

The pharmaceutical industry is currently facing one of the most significant “patent cliffs” in its history, a period characterized by the expiration of patents on numerous blockbuster drugs. This phenomenon is set to put over $200 billion in annual revenue at risk for originator companies through 2030, creating a substantial and unprecedented opportunity for the generic and biosimilar sector.9 Major drugs with multibillion-dollar annual sales, including AbbVie’s Humira, Merck’s Keytruda, and Bristol Myers Squibb’s Opdivo, are among those losing market exclusivity.9 Historically, a blockbuster drug can lose up to 80% of its revenue within the first year of facing generic competition, underscoring the scale of the market share available for capture.9

However, the nature of this opportunity is fundamentally different from that of previous patent cliffs. The wave of expirations in the early 2010s primarily involved small-molecule, chemically synthesized drugs that were relatively straightforward to replicate as generics.9 The current and upcoming cliff is dominated by biologics—large, complex molecules derived from living cells.9 This distinction is critical. Competition for these products will come not from traditional generics, but from biosimilars. The development and manufacturing of biosimilars are vastly more complex, expensive, and time-consuming. Furthermore, because they are “highly similar” but not identical to the originator biologic, they are not always directly interchangeable at the pharmacy level, which can slow market adoption.9

This shift has profound strategic implications for both innovator and generic companies. Originator companies are deploying sophisticated lifecycle management strategies, including the creation of “patent thickets” and the development of next-generation formulations, to defend their franchises and slow revenue erosion.3 For generic manufacturers, the landscape has transformed. The barrier to entry for these high-value biosimilar opportunities is immense, requiring deep scientific expertise, significant capital investment in advanced manufacturing, and the capacity to conduct extensive clinical trials.11 The traditional generic model of simple reverse-engineering is inadequate for this new reality. To successfully capitalize on the biologic patent cliff, generic companies must evolve, developing or acquiring a host of new capabilities. This imperative to tackle greater complexity in pursuit of higher-value products is a primary driver compelling them to seek strategic partnerships to share the formidable risks and costs involved.

1.3 The Buyer’s Gambit: The Impact of GPO and Payer Consolidation

The downward pressure on generic drug prices is not solely a function of supply-side competition; it is powerfully amplified by the highly concentrated structure of the demand side. A small number of Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) act as dominant wholesale buyers, representing the interests of large retail pharmacy chains, hospital systems, and insurance plans.8 These entities wield enormous bargaining power, which they use to exert relentless downward pressure on wholesale prices and manufacturer profits.8

This buy-side concentration fundamentally alters the market dynamics. It transforms the market from a simple competitive landscape into a complex oligopsony, where a few powerful buyers dictate terms to many sellers.7 This power imbalance exacerbates the price erosion described earlier and further squeezes the already thin profit margins of generic manufacturers.1 When profits are persistently low, manufacturers have little incentive to invest in maintaining or expanding production capacity, particularly for older, less profitable drugs. They are also discouraged from holding buffer inventories, which could mitigate the impact of demand spikes or temporary production interruptions.8

The result is a market structure that is inherently fragile. The combination of intense price competition among a small number of suppliers and the immense pricing power of a few large buyers creates a precarious economic environment.7 This dynamic is a significant contributor to the increasing frequency of drug shortages. Studies have found that shortages are most common in markets that are highly concentrated (four or fewer manufacturers) and have low revenue (less than $5 million annually).8 In this context, partnerships can offer a strategic response. By forming alliances or merging, generic manufacturers can increase their scale, potentially enhancing their negotiating leverage with these powerful consolidated buyers and creating a more stable and sustainable business model.1

1.4 The Fragile Chain: Exposing Systemic Vulnerabilities in the Global Generic Supply Network

The generic drug supply chain, optimized over decades for maximum cost efficiency, has become a model of global interdependence, but also one of profound fragility. A key vulnerability stems from the extreme geographic concentration of manufacturing for critical pharmaceutical inputs. The production of both Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and the Key Starting Materials (KSMs) from which they are derived is heavily reliant on a small number of countries, most notably China and India.7

India stands as one of the largest suppliers of finished generic medicines to the world, including providing approximately 50% of the generics used in the United States.16 However, India itself is highly dependent on external sources for its raw materials, importing around 70% of its APIs, predominantly from China.17 This creates a multi-layered dependency where a disruption in China can have cascading effects, impacting Indian manufacturing and, subsequently, the supply of finished drugs to the U.S. and other global markets. This concentration creates significant geopolitical and logistical risks, as demonstrated by the manufacturing shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, which highlighted the dangers of relying on a single region for critical medicines.14

The relentless economic pressure on the industry has also discouraged investment in supply chain redundancy. Over-reliance on single-source suppliers for specific APIs or KSMs is a common practice driven by cost-cutting, but it leaves the supply chain highly susceptible to disruption.15 Quality-related breakdowns at a single manufacturing facility have been a primary and recurring cause of drug shortages, as there are often no alternative suppliers available to fill the gap quickly.8

In response to these systemic risks, a strategic shift is underway. Governments and policymakers are increasingly focused on bolstering supply chain resilience. This has led to a growing push for “onshoring” (bringing manufacturing back to domestic soil) and “friendshoring” (relocating supply chains to allied nations).20 Initiatives such as India’s

Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-Reliant India) program aim to boost domestic API production, while U.S. policymakers are exploring incentives to strengthen the domestic manufacturing base.17 For generic companies, this new focus on supply security creates both challenges and opportunities. Building resilient, diversified, and geographically distributed supply chains is a capital-intensive endeavor that is difficult to undertake alone. This necessity is becoming a powerful catalyst for new types of partnerships, including collaborations to establish dual-sourcing capabilities, joint ventures for domestic manufacturing, and alliances to improve end-to-end supply chain visibility and coordination.

Section 2: The New Development Engine: The Strategic Role of CROs and CDMOs

As the generic drug industry confronts the dual pressures of economic erosion and rising product complexity, its historical reliance on in-house capabilities is giving way to a more networked and collaborative development model. At the heart of this transformation are Contract Research Organizations (CROs) and Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs). Once viewed as tactical vendors for outsourcing discrete tasks, these entities have evolved into indispensable strategic partners. They now provide the critical expertise, advanced technologies, and integrated services that are essential for navigating the modern development landscape. This section examines the evolution of the outsourcing model and analyzes how CROs and CDMOs have become the new engine of development and innovation for the generic pharmaceutical sector.

2.1 From Transaction to Transformation: The Evolution of the Outsourcing Model

The relationship between pharmaceutical companies and their external service providers has undergone a profound transformation. The traditional model was largely transactional, focused on outsourcing specific, often repetitive, tasks to manage costs or capacity constraints. Today, the dynamic is increasingly strategic, characterized by deep integration and shared objectives. This shift is driven by the escalating complexity of drug development, the intense pressure to accelerate timelines, and the need to access specialized expertise that is often not available in-house.23

CROs and CDMOs serve distinct but complementary functions within this ecosystem. CROs specialize in the research and clinical development phases, offering a suite of services that includes clinical trial planning and management, regulatory affairs, patient recruitment, biostatistics, and data management.23 CDMOs, by contrast, focus on the later stages of development and manufacturing. Their expertise lies in formulation development, analytical testing, scaling up production from clinical to commercial quantities, and ensuring compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP).23

The market for these services is experiencing robust growth, a clear indicator of the industry’s increasing reliance on outsourcing. The global CRO market is projected to reach $127.3 billion by 2028, while the broader pharmaceutical outsourcing market is anticipated to hit $121.3 billion by 2034.23 This escalating demand is fundamentally altering the nature of the relationship. CROs and CDMOs are no longer just hired hands; they are now integral partners involved in collaborative planning, joint problem-solving, and even risk-sharing arrangements.23 Consequently, the selection of an outsourcing partner has become a critical strategic decision. A misaligned partnership can lead to significant setbacks, including missed deadlines, budget overruns, and critical quality or regulatory failures, underscoring the importance of vetting partners not just on price, but on their capabilities, experience, and cultural fit.23

2.2 Integrated Solutions: How CDMOs are Becoming End-to-End Development Partners

A key trend within the outsourcing landscape is the rise of the integrated CDMO. This model represents a significant evolution from the traditional Contract Manufacturing Organization (CMO), which historically focused solely on large-scale production of an already-developed drug.24 The modern CDMO offers a comprehensive, end-to-end suite of services that spans the entire development lifecycle, from initial formulation and analytical method development through to clinical trial supply, regulatory submission support, and full-scale commercial manufacturing.25

This “one-stop-shop” approach offers substantial strategic advantages. By consolidating development and manufacturing activities under a single partner, companies can significantly reduce the risks, costs, and delays associated with technology transfer between separate vendors.23 The seamless transition from development to manufacturing streamlines the overall process, accelerating the product’s journey to market—a critical competitive factor in the generic industry.26

Generic drug manufacturers are identified as a primary client base that stands to benefit immensely from these integrated CDMO partnerships.26 As they venture into more complex formulations and delivery systems, generic companies often lack the specialized in-house expertise required for development. A strategic CDMO partner can fill this capability gap, providing not just manufacturing capacity but also crucial intellectual capital in areas like advanced formulation science, complex analytical characterization, and navigating intricate regulatory requirements.26 This shift in function is profound: the CDMO is no longer simply executing a pre-defined manufacturing process but is actively co-developing the product alongside the generic firm. This deep integration transforms the CDMO from a simple supplier into a vital extension of the generic company’s own R&D and technical operations functions, making the partnership a cornerstone of the entire development strategy.

Section 3: Conquering Complexity: Partnership Models for Biosimilars and High-Barrier Generics

The most significant growth opportunities in the off-patent market lie in complex generics and biosimilars. These products target lucrative revenue streams from expiring blockbuster drugs but present scientific, financial, and regulatory hurdles that are orders of magnitude greater than those for traditional small-molecule generics. The sheer scale of these challenges makes the traditional, largely self-contained development model untenable for all but the largest and most specialized firms. For the vast majority of players, market entry is only feasible through a web of strategic partnerships designed to distribute risk, pool capital, and aggregate the diverse expertise required. This section examines the unique difficulties posed by these high-barrier products and explores the collaborative models that have become essential for conquering this complexity.

3.1 The Biosimilar Challenge: Navigating Higher Costs, Timelines, and Regulatory Scrutiny

It is a fundamental error to view biosimilars as merely complex generics. They represent a distinct and far more challenging development paradigm.27 A generic drug is a chemically synthesized small molecule, identical to its reference product. A biosimilar, in contrast, is a large, complex biologic medicine produced in living cells. Due to the inherent variability of biological processes, a biosimilar can only ever be “highly similar,” not an exact replica, of its reference product.12 This foundational difference gives rise to an exponentially higher barrier to entry.

The development pathway for a biosimilar is a long, expensive, and high-risk endeavor, starkly different from that of a typical generic:

- Cost: The investment required to develop and market a biosimilar is estimated to be over $100 million, compared to just $1-2 million for a conventional generic drug.12

- Timeline: Bringing a biosimilar to market can take between 5 and 9 years, a significant increase from the approximately 2-year timeline for a generic.12

- Regulatory Demands: While a generic requires a relatively straightforward bioequivalence study to demonstrate that it delivers the same amount of active ingredient to the bloodstream over time, a biosimilar must undergo a far more rigorous regulatory process. This involves a comprehensive “comparability exercise” to demonstrate high similarity to the reference product through extensive and sophisticated analytical characterization, non-clinical studies, and often, large-scale clinical trials to confirm safety and efficacy for each intended indication.12

Beyond these development hurdles, biosimilars face significant market adoption challenges that do not exist for generics. Because they are not identical copies, gaining the trust and acceptance of physicians, payers, and patients requires substantial educational efforts and robust post-marketing data to build confidence in their clinical interchangeability.27 The immense capital costs, prolonged timelines, and multifaceted risks inherent in biosimilar development make alliances and co-development partnerships not just advantageous, but a near-necessity for most companies seeking to enter this lucrative market.29

3.2 Beyond Bioequivalence: The Scientific and Manufacturing Hurdles of Complex Generics

While not as demanding as biosimilars, complex generics represent a significant step up in difficulty from traditional oral solid dosage forms. These products are defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as having complex active ingredients (e.g., peptides, complex mixtures), complex formulations (e.g., liposomes, colloids), complex routes of delivery (e.g., locally acting dermatological products, metered-dose inhalers), or being complex drug-device combination products (e.g., auto-injectors).31

The primary challenge with these products is that the well-established regulatory pathway for demonstrating bioequivalence for simple generics is often inadequate or inapplicable.32 Proving that a generic topical cream or a nasal spray performs identically to its reference product cannot be accomplished with a simple blood test. Instead, developers must often employ a battery of more sophisticated and less certain methodologies, which can include:

- In vitro studies, such as in vitro release testing (IVRT) and in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) for topical products.34

- Pharmacodynamic (PD) studies that measure a drug’s effect on the body, rather than its concentration in the blood.35

- Large-scale clinical trials with clinical endpoints, which are more akin to the studies required for new drugs.33

- Specialized studies for drug-device combinations, such as adhesion studies and skin irritation and sensitization studies for transdermal patches.35

This scientific and regulatory uncertainty makes the development of complex generics inherently riskier and more costly than their simpler counterparts.32 Recognizing that these hurdles can stifle competition, the FDA has prioritized efforts to clarify the approval pathways. Through its Drug Competition Action Plan (DCAP), the agency actively issues Product-Specific Guidances (PSGs) that provide detailed recommendations on the most appropriate methods for demonstrating equivalence for specific complex products.31 The FDA also fosters collaboration between the agency, industry, and academia through initiatives like the Center for Research on Complex Generics (CRCG) to address shared scientific challenges.37 Despite these efforts, the specialized scientific and manufacturing expertise required means that partnerships with specialized CDMOs and CROs are often essential for successfully navigating the development and approval process.

| Metric | Traditional Small Molecule Generic | Complex Generic (e.g., Topical/Inhaler) | Biosimilar |

| Estimated Development Timeline | ~2 years 12 | 3-5+ years | 5-9 years 12 |

| Estimated Development Cost | $1-2 million 12 | $5-20 million+ | $100 million+ 12 |

| Key Scientific Challenge | Replicating formulation and demonstrating pharmacokinetic (PK) equivalence. | Matching complex formulation (e.g., particle size, viscosity) and drug release characteristics. | Matching complex protein structure, including post-translational modifications like glycosylation.12 |

| Primary Regulatory Hurdle | In vivo bioequivalence (BE) study measuring drug concentration in blood (PK endpoints).35 | Alternative BE approaches: in vitro studies (IVRT/IVPT), pharmacodynamic studies, or clinical endpoint studies.33 | Comprehensive “comparability exercise” including extensive analytical, non-clinical, and clinical data to prove no clinically meaningful differences.12 |

| Typical Partnership Need | Standard CDMO for formulation scale-up and manufacturing. | Specialized CDMO with expertise in specific delivery systems and advanced analytical capabilities.32 | Multi-partner ecosystem: cell-line developer, manufacturing CDMO, clinical CRO, commercialization partner.38 |

3.3 Risk-Sharing and Co-Development: Structuring Partnerships to Mitigate High-Stakes Investment

The formidable financial and technical risks associated with developing complex generics and, especially, biosimilars necessitate partnership models that go far beyond simple fee-for-service outsourcing. To manage these high-stakes investments, companies are increasingly turning to structures that allow for the sharing of both risks and potential rewards, such as co-development agreements and formal joint ventures (JVs).

The logic is straightforward: the high capital costs and significant probability of failure make solo development a prohibitive gamble for many firms.29 By partnering, companies can pool their resources, effectively distributing the financial burden and mitigating the impact of a potential setback. These collaborations are not just about capital; they are about combining complementary capabilities. A successful partnership might bring together one company’s strength in early-stage development and manufacturing with another’s expertise in late-stage clinical trials, regulatory affairs, and commercial market access.39

This collaborative approach is now the dominant model in the biosimilar space. Case studies of successful biosimilar launches frequently reveal a co-development or commercialization partnership at their core. For example, the U.S. launch of Truxima (a biosimilar to Rituxan) was facilitated by a strategic partnership between its developer, Celltrion, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, which leveraged Teva’s established distribution network and commercial presence to drive market penetration.38 Similarly, Samsung Bioepis, a major player in the biosimilar market, was established as a joint venture between Samsung Biologics and Biogen, combining Samsung’s manufacturing prowess with Biogen’s development and commercial expertise.39 These examples illustrate a clear trend: for the most complex and valuable products, creating a bespoke alliance ecosystem is no longer an alternative strategy, but the primary pathway to market.

Section 4: The Technology Catalyst: How Digital Innovation is Forging New Alliances

The generic pharmaceutical industry, long characterized by its focus on replicating existing science, is now being reshaped by a wave of technological disruption. Advanced digital tools and novel manufacturing paradigms are introducing new levels of efficiency, precision, and predictive power across the development lifecycle. Technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), continuous manufacturing (CM), and advanced data analytics are no longer futuristic concepts but are becoming practical tools for gaining a competitive edge. However, the high cost and specialized expertise required to implement these innovations create a significant barrier for many generic companies. This technology gap is acting as a powerful catalyst for a new category of partnerships, forcing traditional drugmakers to collaborate with technology firms, specialized engineering companies, and data science experts to access the capabilities needed to compete in the future.

4.1 AI-Accelerated Development: Partnerships in Predictive Formulation, Process Optimization, and Quality Control

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (ML) are rapidly moving from the periphery to the core of pharmaceutical development, offering the potential to dramatically accelerate timelines and reduce costs. The application of AI spans the entire development process, from early-stage research to post-market surveillance.40

In the context of generic development, AI is proving particularly valuable in several key areas:

- Formulation Development: AI/ML algorithms can analyze vast datasets on the physicochemical properties of drug molecules and excipients to build predictive models. These models can estimate critical formulation parameters such as solubility, stability, and bioavailability, allowing scientists to optimize formulations more efficiently and with fewer physical experiments. This approach aligns with the FDA’s Quality by Design (QbD) initiative by establishing robust correlations between formulation variables and product performance.42

- Manufacturing and Process Optimization: In the manufacturing environment, AI can analyze real-time data from production lines and sensors to identify patterns, detect process deviations, and suggest adjustments to improve efficiency and ensure consistent quality. AI-powered systems can also enable predictive maintenance, forecasting equipment failures before they occur to prevent costly downtime.42

- Quality Control (QC): AI-driven image recognition algorithms can be used to automate QC inspections, identifying subtle defects in tablets or packaging that might be missed by human inspectors. This enhances product quality and consistency while freeing up personnel for more complex tasks.42

The highly specialized nature of these AI tools means that their development and implementation almost always occur through partnerships. Generic and branded pharmaceutical companies alike are forming strategic alliances with specialized AI drug discovery firms and major technology companies to build these capabilities. Notable collaborations include Sanofi’s partnership with OpenAI and Formation Bio to accelerate therapeutic design, Pfizer’s work with AWS on manufacturing analytics and with XtalPi on molecular modeling, and Teva’s collaborations with firms like Immunai and Insilico Medicine for target discovery and clinical trial optimization.43 Recognizing this trend, regulatory bodies are also adapting; the FDA has established an internal AI Council and is developing a regulatory framework to guide the use of AI in submissions, signaling its growing importance in the industry.53

4.2 The Continuous Manufacturing Consortium: Collaborative Models for Modernizing Production

Pharmaceutical Continuous Manufacturing (CM) represents a paradigm shift from the industry’s traditional, century-old method of batch production. Instead of a stepwise process with lengthy pauses for testing and material transfer, CM utilizes an integrated, uninterrupted flow where raw materials are continuously fed into a closed system and emerge as finished products.54 This advanced manufacturing technology (AMT) offers transformative benefits, including significantly smaller manufacturing footprints (up to 70% smaller), reduced operational costs, improved process efficiency, and enhanced product quality and consistency through real-time monitoring and control.57

Despite these clear advantages, the adoption of CM has been slow, particularly within the generic sector.57 The primary barriers are threefold:

- Economic: The upfront capital investment required to build new CM facilities or retrofit existing ones is substantial. For generic manufacturers operating on thin margins, the uncertain return on this investment presents a significant financial risk.57

- Regulatory: While the FDA strongly encourages the adoption of CM and has issued draft guidance, there remains a degree of regulatory uncertainty for manufacturers, as the pathways and data requirements are still evolving.54

- Workforce: There is a significant shortage of scientists and engineers with the specialized skills and experience needed to design, implement, and operate CM systems.57

Given these formidable barriers, collaboration has emerged as the primary vehicle for advancing CM. Rather than shouldering the entire burden alone, companies are forming consortia and multi-partner alliances that pool resources, share risks, and combine complementary expertise. These ecosystems often bring together pharmaceutical manufacturers, specialized equipment providers (like GEA), automation and process control experts (like Siemens), and academic research centers.60 A prominent example is the strategic partnership between Sandoz and Just-Evotec Biologics, which leverages an advanced, AI-driven platform and continuous manufacturing technology to develop and produce Sandoz’s pipeline of biosimilars. This collaboration recently evolved, with Sandoz moving to acquire the dedicated manufacturing facility, demonstrating a long-term commitment to the technology enabled by the initial partnership.39 Such collaborative models are proving essential to de-risk the investment and accelerate the adoption of this transformative manufacturing technology.

4.3 Data-Driven Decisions: Leveraging Advanced Analytics and Joint Ventures for Supply Chain Visibility and Prediction

The modern generic drug supply chain is a vastly complex global network, yet it is often plagued by operational inefficiencies and a critical lack of end-to-end visibility.15 This opacity makes it difficult for companies to anticipate demand fluctuations, manage inventory effectively, and respond proactively to potential disruptions, contributing to the persistent problem of drug shortages.15

Advanced data analytics and digital technologies offer a powerful solution to these challenges. By harnessing tools like AI, machine learning, and blockchain, companies can transform their supply chains from reactive to predictive systems.15 Key applications include:

- Demand Forecasting: AI algorithms can analyze historical sales data, seasonal trends, and external factors to generate more accurate demand forecasts, reducing the risk of both stockouts and costly excess inventory.43

- Real-Time Traceability: Technologies like blockchain can create a secure, transparent, and immutable ledger of a drug’s journey from API manufacturing to the pharmacy shelf, enhancing security and enabling rapid identification of issues.66

- Predictive Risk Management: Advanced analytics can monitor a wide range of variables—from geopolitical events to weather patterns and shipping lane congestion—to identify potential supply chain disruptions before they occur, allowing companies to take preemptive action.43

However, realizing the full potential of a data-driven supply chain requires access to vast and diverse datasets that often reside with different stakeholders across the network (e.g., manufacturers, distributors, healthcare providers). No single company possesses all the necessary data or analytical capabilities. This reality is driving the formation of data-centric partnerships and joint ventures designed to pool data and expertise. An example of this trend is the joint venture between TriNetX, a global real-world data provider, and Fujitsu, a leading electronic health record (EHR) vendor in Japan. Their collaboration aims to create a platform that leverages anonymized patient EHR data to optimize clinical trials and accelerate drug development, demonstrating how partnerships can unlock the value of previously siloed data.68 For many mid-tier and smaller generic firms, which may lack the resources to build sophisticated in-house analytics teams, partnering with or fully outsourcing this function to specialized analytics providers will be essential to remain competitive.67

Section 5: Architecting the Alliance: Legal, Financial, and IP Frameworks for Success

The strategic decision to pursue a partnership is only the first step. The long-term success or failure of a collaboration hinges on the robustness of its underlying architecture—the legal structures, financial models, and intellectual property (IP) frameworks that govern the relationship. As generic drug development moves into more complex products and multifaceted alliances, the sophistication required to design and manage these frameworks has increased dramatically. A one-size-fits-all approach is no longer sufficient. Instead, companies must become adept at tailoring partnership structures to specific strategic objectives, managing the intricate dynamics of multi-partner ecosystems, and proactively safeguarding their most valuable assets. This section provides a practical analysis of the operational “how,” detailing the key components for building successful and sustainable partnerships.

5.1 Structuring for Success: A Comparative Analysis of Joint Ventures, Licensing, and Strategic Alliances

Collaborations in the pharmaceutical industry exist along a spectrum of integration and complexity, ranging from straightforward contractual agreements to fully integrated joint ventures.69 The optimal structure depends entirely on the strategic goals of the partnership, the nature of the assets being shared, and the level of risk involved.

- Contractual Agreements (e.g., Distribution, Fee-for-Service): These represent the simplest form of collaboration. A generic company might engage a CDMO on a fee-for-service basis for manufacturing or sign a distribution agreement with a local partner to access a new market. These arrangements are transactional, involve minimal shared control, and are suitable for low-risk, well-defined tasks.69

- Licensing Agreements: In this model, one party grants another the right to use its intellectual property (e.g., a patent, trademark, or proprietary know-how) in exchange for fees, milestones, and/or royalties. This is a common structure for commercialization, where a developer licenses out marketing rights to a partner with an established sales infrastructure in a specific region.69

- Strategic Alliances and Co-Development: These are more integrated partnerships where two or more companies agree to collaborate on a specific project, such as the co-development of a complex generic or biosimilar. While they may not form a new legal entity, these alliances involve shared decision-making, joint steering committees, and often complex risk-sharing arrangements where costs and future revenues are divided according to a pre-agreed formula.72

- Joint Ventures (JVs): This is the most integrated form of collaboration, involving the creation of a new, separate legal entity jointly owned and operated by the parent companies.69 JVs are often used for high-risk, high-investment projects like building a new manufacturing facility or entering a challenging market like China. They require a comprehensive legal framework, including a shareholders’ agreement that meticulously defines the venture’s purpose, governance structure, capital contributions, profit distribution mechanisms, IP rights, and provisions for dispute resolution and eventual exit.69

The financial modeling underpinning these more complex structures is critical. While standard Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) or Net Present Value (NPV) models are suitable for valuing established assets, they are inadequate for development-stage projects with high uncertainty.76 For these, a

risk-adjusted NPV (rNPV) methodology is the industry standard. This approach explicitly incorporates the probability of success at each stage of development (e.g., Phase I, Phase III, regulatory approval), providing a more realistic valuation of high-risk assets.76 More advanced models, such as Real Options Analysis, can also be used to quantify the value of strategic flexibility—such as the option to expand, delay, or abandon a project based on interim results.78 The choice of partnership structure and its supporting financial model must be directly proportional to the complexity and risk of the underlying project, requiring generic firms to develop sophisticated deal-making capabilities.

| Partnership Model | Typical Application/Goal | Key Strategic Benefit | Primary Risk/Challenge | Illustrative Example |

| CRO/CDMO Outsourcing (Fee-for-Service) | Routine tasks: API synthesis, batch manufacturing, standard BE studies. | Cost efficiency, access to capacity without capital investment. | Quality control failures, lack of strategic alignment, vendor dependency. | A generic firm contracts a CDMO to manufacture batches of a simple oral solid drug.71 |

| Strategic CDMO Alliance | Development and manufacturing of complex generics or biosimilars. | Access to specialized technology and expertise, accelerated timelines. | High cost, technology transfer risks, potential for misalignment on long-term goals. | Sandoz’s partnership with Just-Evotec for continuous manufacturing of biosimilars.65 |

| Joint Venture (JV) | Market entry into new regions (e.g., China), co-investment in high-cost assets (e.g., new factory). | Shared risk and capital investment, access to local market knowledge and distribution. | Complex governance, potential for cultural clashes, difficult exit strategy.69 | Samsung Bioepis, a JV between Samsung Biologics and Biogen to develop biosimilars.39 |

| Co-Development / Risk-Sharing Agreement | High-risk development of a novel or complex product like a biosimilar. | Mitigates high R&D costs and failure risk by sharing them among partners. | Defining fair value for contributions, aligning on development strategy, IP ownership. | A biotech and a pharma company co-fund clinical trials, splitting future profits.72 |

| Academic Collaboration | Early-stage research, access to novel targets or platform technologies. | Low-cost access to cutting-edge science and talent, potential for novel IP. | “Culture clash” between academic and commercial timelines, IP ownership ambiguity. | A pharma company funds a university lab to explore a new disease pathway.80 |

| Technology Licensing (e.g., AI) | Accessing specialized platforms for formulation, drug discovery, or process optimization. | Rapidly acquire advanced capabilities without building them in-house. | High licensing fees, dependency on a third-party platform, data integration challenges. | A pharma company licenses an AI platform to screen compounds for new targets.45 |

5.2 Managing Multi-Partner Ecosystems: Governance, Communication, and Conflict Resolution

The technical and financial success of a partnership is often predicated on the strength of the relationship itself. Research consistently shows that a majority of alliance failures are not due to scientific or market-related issues, but to breakdowns in the partnership dynamic. Common culprits include cultural clashes between organizations, poor or infrequent communication, the emergence of conflicting strategic priorities over time, and a general lack of trust.79 Therefore, managing this “relationship risk” is as critical as managing the technical and commercial risks of the project.82

Effective management of a partnership, particularly a complex multi-partner ecosystem, requires a deliberate and proactive approach to governance. This begins during the negotiation phase with the establishment of a clear and robust governance structure. This structure should be formally codified in the partnership agreement and typically includes:

- Joint Steering Committees (JSCs): Composed of senior leaders from each partner organization, the JSC is responsible for overall strategic oversight, major decision-making, and budget approval.

- Joint Project Teams: Comprised of operational staff from each partner, these teams are responsible for the day-to-day execution of the project.

- Decision-Making Protocols: The agreement must clearly define how decisions are made. This includes specifying which decisions require unanimous consent, which can be made by a majority vote, and which fall under the authority of the project leader. It should also include a clear escalation pathway for resolving disagreements that cannot be settled at the project team level.83

- Communication Plans: A formal communication plan should outline the frequency and format of meetings, reporting requirements, and key points of contact to ensure a consistent and transparent flow of information.81

For complex or high-stakes alliances, the appointment of a dedicated Alliance Manager is a critical success factor.84 This role serves as the central hub for the partnership, responsible for overseeing contractual obligations, facilitating governance meetings, monitoring the overall health of the relationship, and acting as a neutral intermediary to resolve conflicts. An effective Alliance Manager possesses a unique blend of project management skills, interpersonal acumen, and the ability to influence outcomes without direct authority, ensuring that the partnership remains aligned and focused on its shared goals.84

5.3 Protecting and Leveraging Value: Intellectual Property (IP) Management in Collaborative Development

In the pharmaceutical industry, intellectual property is a core asset and a primary driver of value. While collaboration is essential for innovation, it also introduces significant complexity to the management and protection of IP. When multiple parties contribute their knowledge and resources to a project, the lines of ownership for newly created inventions can become blurred, creating a high potential for disputes that can jeopardize the entire venture.85

Proactive and meticulous IP management is therefore a foundational requirement for any successful partnership. This must be addressed from the very beginning of the relationship and enshrined in a comprehensive, legally binding agreement. A robust IP framework within a partnership agreement should clearly delineate several key areas:

- Background IP: The agreement must identify and list the pre-existing IP that each partner is bringing into the collaboration. It should also specify the rights that each partner grants to the others to use this background IP for the purposes of the joint project.85

- Foreground IP: This refers to any new IP that is generated during the course of the collaboration. The agreement must establish clear rules for determining ownership of this foreground IP. This can be structured in various ways: one party may own all foreground IP, or ownership may be allocated based on inventorship or the specific domain of the invention.74

- Joint Inventions: It is common for inventions to be created jointly by individuals from multiple partner organizations. The agreement must outline a clear process for handling these joint inventions, including how inventorship will be determined and how the rights and responsibilities associated with joint ownership (such as patent filing, maintenance costs, and commercialization rights) will be managed.85

- Confidentiality: Strong confidentiality clauses are essential to protect sensitive research data, trade secrets, and other proprietary information shared during the collaboration.85

Beyond the initial agreement, effective IP management is an ongoing process. It requires meticulous record-keeping throughout the research and development process to document contributions and establish a clear record of inventorship. Conducting regular IP audits during the partnership allows the parties to formally review the IP that has been generated, assess its strategic value, and ensure that its management and protection align with the goals of the collaboration.85

Section 6: A Global Chessboard: Navigating International Regulatory and Market Dynamics

The generic drug industry operates on a global stage, but the rules of the game vary dramatically from one region to another. A product approval in the United States does not guarantee market access in Europe, and a pricing strategy that works in India would be unviable in China. This fragmented landscape of divergent regulatory pathways, pricing mechanisms, and market access challenges makes a single, monolithic global strategy ineffective. Success in the future requires a nuanced, region-specific approach, leveraging a portfolio of partnerships tailored to the unique strengths and complexities of each key market. This section analyzes the critical differences between major global markets and explores how international dynamics are shaping the future of partnerships.

6.1 Divergent Pathways: A Comparative Analysis of Regulatory and Pricing Frameworks

While there are efforts toward global harmonization, significant differences persist in how major markets regulate and reimburse generic drugs, necessitating distinct strategies for each.

- United States: The U.S. market is governed by the FDA and the principles of the Hatch-Waxman Act. The pathway for simple generics is well-defined, centered on demonstrating bioequivalence.86 For biosimilars, the U.S. has a distinct regulatory designation of “interchangeability,” which, if achieved, allows for pharmacy-level substitution without physician intervention—a high bar that can impact market uptake.87 Pricing is largely market-driven, but heavily influenced by the negotiating power of PBMs and GPOs, leading to intense price competition.8

- European Union: The EU presents a more complex, two-tiered system. A marketing authorization can be obtained centrally through the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which is valid across all member states.89 However, this centralized approval does not guarantee market access. Pricing and reimbursement decisions are made at the national level by individual member states, each with its own health technology assessment (HTA) bodies and pricing policies.90 This creates a fragmented landscape where a company must navigate dozens of unique reimbursement systems after securing EMA approval. For biosimilars, the EMA does not have an interchangeability designation, deferring substitution policies to national authorities.87

- China: China’s regulatory body, the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA), has undergone significant reforms to align with international standards.91 The generic approval pathway is defined by registration classes based on whether the reference drug is already marketed in China.92 The most impactful market feature is the National Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) policy. Under VBP, manufacturers bid for the right to supply a guaranteed, large volume of a specific drug to public hospitals, often at drastically reduced prices. This “winner-takes-most” system has fundamentally reshaped the competitive landscape, squeezing margins, driving market consolidation, and forcing both domestic and multinational companies to radically rethink their pricing and commercial strategies.93

- India: Overseen by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), India’s regulatory framework has historically fostered a world-leading domestic generic industry.96 The government actively promotes the use of generic medicines through public health initiatives like the Pradhan Mantri Bharatiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP), which aims to ensure the availability of affordable, quality generics through a network of dedicated pharmacies.96

| Region | Regulatory Body | Key Approval Pathway | Primary Pricing Pressure | Key Market Access Challenge |

| United States | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) based on bioequivalence.86 | Intense competition and negotiating power of consolidated PBMs/GPOs.8 | Securing favorable formulary placement with major payers; achieving “interchangeability” for biosimilars.88 |

| European Union | European Medicines Agency (EMA) & National Authorities | Centralized Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA) via EMA, or national procedures.89 | National-level price controls, reference pricing, and competitive tenders.97 | Navigating dozens of individual country-level pricing and reimbursement negotiations after EMA approval.90 |

| India | Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) | Domestic approval process governed by Drugs and Cosmetics Act.96 | Government price controls on essential medicines; high domestic competition.17 | Navigating price controls; perception issues and physician preference for branded drugs.96 |

| China | National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) | Domestic registration process with distinct classes for generics.92 | National Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) leading to extreme price reductions.93 | Winning VBP tenders, which requires aggressive pricing and guaranteed supply capacity.98 |

6.2 The India-China Axis: The Evolving Role of Asian Partners in the Global Supply and Development Chain

India and China form the central axis of the global generic pharmaceutical supply chain, but their roles are evolving, presenting both opportunities and challenges for international partners.

India has long earned the title of “pharmacy of the world,” serving as a dominant manufacturer and exporter of affordable generic medicines.17 The country is a critical supplier to the U.S. market, accounting for a substantial portion of its generic drug needs.16 This position is built on a foundation of cost-effective manufacturing and a large pool of skilled scientific talent. However, the Indian industry faces significant headwinds. It remains heavily dependent on China for the import of APIs and KSMs, creating a key supply chain vulnerability.18 Furthermore, Indian manufacturers exporting to Western markets face the high cost of maintaining facilities compliant with stringent US FDA and EMA standards, as well as the persistent threat of geopolitical risks like trade tariffs, which could render the low-margin export model financially unviable.16

China, traditionally viewed as the primary global source for APIs and chemical intermediates, is undergoing a strategic transformation. While it remains a cornerstone of the upstream supply chain, the government’s aggressive VBP policy is acting as a powerful catalyst for change within its domestic industry.93 The intense price pressure of VBP is driving rapid market consolidation and forcing Chinese pharmaceutical companies to move up the value chain. To survive, they must shift their focus from high-volume, low-margin generics toward innovation, including the development of complex generics and novel drugs.94 This shift means that Chinese firms are increasingly poised to become not just suppliers, but also sophisticated development and commercialization partners. For Western firms, the immense complexity and unique dynamics of the Chinese market make local partnerships an essential prerequisite for market access and success.100

6.3 Harmonization and Headwinds: The Future of Global Regulatory Collaboration and Geopolitical Risk

Amid the fragmented global landscape, there are encouraging signs of increasing collaboration and harmonization among the world’s leading regulatory agencies. Initiatives like the FDA’s Generic Drug Cluster provide a formal forum for regulators from the U.S., Europe, and other regions to discuss scientific standards, share information on review issues, and work toward greater alignment on the requirements for generic drug approval.102 This collaboration is bearing fruit. A recent analysis found a 95% concordance rate in the final approval decisions between the FDA and the EMA for generic drug applications that were submitted to both agencies by the same applicant.103 This growing alignment is beneficial for the industry, as it reduces the need for duplicative studies and makes it more feasible to use a single data package to support submissions in multiple regions, thereby lowering development costs and accelerating global access to medicines.

However, these positive trends in regulatory cooperation are contrasted by growing geopolitical headwinds. The strategic importance of pharmaceutical supply chains has brought them into the forefront of international trade disputes and national security considerations. The potential imposition of significant U.S. tariffs on goods from India and China, for example, poses a serious threat to the global generic drug model, which relies on cross-border trade and operates on very low profit margins.16 Such tariffs could disrupt the supply of affordable medicines, increase costs for healthcare systems, and force a costly and time-consuming reconfiguration of global supply chains.18 Navigating this volatile intersection of regulatory harmonization and geopolitical risk will be a key strategic challenge for all players in the generic drug ecosystem, further emphasizing the need for flexible and geographically diversified partnership strategies.

Section 7: Future Outlook and Strategic Recommendations

The forces of economic pressure, product complexity, technological disruption, and global fragmentation are irrevocably reshaping the generic drug industry. The era of standalone success based on manufacturing prowess alone is drawing to a close. The future belongs to companies that can master the art and science of collaboration, building and managing a sophisticated ecosystem of partnerships to drive innovation, mitigate risk, and ensure sustainable growth. This concluding section synthesizes the key trends analyzed throughout this report to construct a vision of the successful generic firm of 2030 and provides a set of actionable recommendations for developers, their partners, and policymakers to navigate this new strategic landscape.

7.1 The Partnership-Centric Model: Key Attributes of the Successful Generic Firm of 2030

The successful generic pharmaceutical company of the next decade will bear little resemblance to its predecessors. The winning model will not be defined by the scale of its physical assets, but by the strength, diversity, and agility of its partnership network. The analysis presented in this report points to a future where leading firms are characterized by several key attributes:

- A Lean, Strategically-Focused Core: Rather than attempting to excel at every stage of the value chain, future leaders will maintain a lean internal organization focused on core competencies. These will include astute portfolio selection, sophisticated deal-making, and, most importantly, world-class alliance management. The primary function of the firm will shift from “making” to “orchestrating”—identifying and integrating the best external capabilities to bring a product to market.

- A Diversified Portfolio of Risk and Value: The most resilient companies will manage a balanced portfolio that includes not only traditional, high-volume generics but also a strategic allocation to higher-value, higher-risk products like complex generics and biosimilars. This diversification will be enabled by a portfolio of partnerships, using low-risk fee-for-service models for simple products and more integrated risk-sharing JVs for complex ones. This approach aligns with strategic frameworks that call for firms to either achieve massive scale, vertically integrate, or innovate into higher-value products to escape the commoditization trap.1

- A Resilient and Technology-Enabled Supply Chain: Competitive advantage will increasingly be defined by the ability to guarantee a reliable supply of medicine. The successful firm will have moved beyond a purely cost-optimized supply chain to one designed for resilience. This will be achieved through a network of manufacturing partners that provides geographic diversification, dual-sourcing for critical inputs, and end-to-end visibility powered by advanced data analytics.

- Excellence in Alliance Management: As the number and complexity of partnerships grow, the ability to effectively manage these relationships will become a critical organizational capability. This involves more than just contract management; it requires the cultural and procedural infrastructure to foster trust, ensure strategic alignment, and proactively resolve conflicts with a diverse set of partners, from academic labs to multinational CDMOs and AI technology startups.

7.2 Actionable Blueprint: Recommendations for Building a Resilient and Innovative Partnership Ecosystem

Achieving the vision of a partnership-centric future requires a concerted effort from all stakeholders. The following recommendations provide a blueprint for action:

For Generic Developers:

- Elevate Alliance Management to a Core Strategic Function: Invest in building a dedicated alliance management team with the authority and expertise to evaluate potential partners, structure complex deals, and govern ongoing relationships. This function should be seen as a central driver of value, not a support service.

- Adopt a Portfolio Approach to Partnerships: Do not rely on a single partnership model. Develop a flexible framework for collaboration, using transactional outsourcing for low-risk activities and reserving more integrated models like JVs and risk-sharing for high-stakes, complex development programs.

- Invest in a Digital Collaboration Infrastructure: The efficiency of a networked model depends on the seamless flow of information. Invest in secure, cloud-based platforms that enable real-time data sharing, joint project management, and transparent communication with external partners across the globe.

For CDMOs and CROs:

- Transition from Service Provider to Strategic Partner: Move beyond a transactional, fee-for-service mindset. Proactively offer integrated, end-to-end solutions that address the client’s strategic challenges, from early-stage development through to regulatory approval and commercial supply.

- Invest in Differentiating Technologies: To become indispensable, invest in niche, high-value capabilities that generic firms are unlikely to build in-house. This includes expertise in specific complex delivery systems, advanced analytical characterization, and emerging technologies like continuous manufacturing and AI-driven process controls.

- Develop Flexible and Aligned Business Models: Recognize the financial pressures on generic clients. Develop and offer flexible engagement models, such as performance-based payments, milestone-driven contracts, or even co-investment structures, that align the CDMO/CRO’s success with the client’s commercial outcomes.

For Policymakers and Regulators:

- Continue to Drive Global Regulatory Harmonization: Build on the success of initiatives like the FDA’s Generic Drug Cluster to further align scientific and technical requirements for generic and biosimilar approval. Reducing the need for duplicative studies lowers development costs and accelerates patient access to affordable medicines globally.102

- Incentivize Supply Chain Resilience: Implement policies that reward investment in a secure and resilient pharmaceutical supply chain. This could include tax incentives for domestic manufacturing, the use of multi-year, guaranteed-volume government contracts for critical medicines, and the development of rating systems that allow payers to value and reward supply chain reliability in their procurement decisions.22

- Balance Cost-Containment with Market Sustainability: While pursuing affordability is a primary goal, pricing and reimbursement policies must be designed to ensure a healthy and competitive multi-source market. Policies that drive prices below the sustainable cost of production can lead to market exits and, ultimately, harmful drug shortages. A balanced approach that ensures both affordability and a stable supply is essential for long-term public health.6

7.3 Concluding Analysis: Sustaining Growth and Ensuring Patient Access Through Strategic Collaboration

The generic drug industry is navigating a period of profound and irreversible change. The economic foundations of its traditional business model are cracking under the weight of intense competition and pricing pressure, while the path forward leads directly into the scientifically and financially challenging terrain of complex medicines. In this new era, the strategies that defined success in the past are no longer sufficient.

The central thesis of this report is that strategic collaboration has become the single most critical determinant of future success. The future of the generic drug industry is inextricably linked to the future of its partnerships. The challenges of developing biosimilars, mastering advanced manufacturing technologies, and building resilient global supply chains are too great for most companies to bear alone. The path to navigating these complexities and capitalizing on the opportunities of tomorrow is through the creation of dynamic, multifaceted, and deeply integrated partnership ecosystems.

The companies that thrive will be those that transform themselves from vertically integrated manufacturers into agile orchestrators of a global network of specialized expertise. They will win not by being the biggest, but by being the best connected and the most adept at leveraging the capabilities of their partners. By embracing this new paradigm of strategic convergence, the generic industry can successfully navigate the pressures of today, sustain its growth for the future, and continue to fulfill its vital mission of providing affordable, accessible, and high-quality medicines to patients worldwide.

Works cited

- Generics 2030: Three strategies to curb the downward spiral – KPMG International, accessed August 1, 2025, https://kpmg.com/us/en/articles/2023/generics-2030-curb-downward-spiral.html

- Generic Drug Development – MRIGlobal, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.mriglobal.org/blog-generic-drug-development/

- Journal of Chemical Health Risks Patent Cliffs: What Happens When a Drug Patent Expires?, accessed August 1, 2025, https://jchr.org/index.php/JCHR/article/download/8398/4800/15877

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed August 1, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- Generic pharmaceutical price decay – Wikipedia, accessed August 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generic_pharmaceutical_price_decay

- Cheaper is not always better: Drug shortages in the United States and a value-based solution to alleviate them, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11217858/

- The Evolution of Supply and Demand in Markets for Generic Drugs …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8452364/

- Industrial Policy To Reduce Prescription Generic Drug Shortages, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/industrial-policy-to-reduce-prescription-generic-drug-shortages/

- The Impact of Patent Cliff on the Pharmaceutical Industry, accessed August 1, 2025, https://bailey-walsh.com/news/patent-cliff-impact-on-pharmaceutical-industry/

- The Patent Cliff: From Threat to Competitive Advantage – Esko, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.esko.com/en/blog/patent-cliff-from-threat-to-competitive-advantage

- Big Pharma Prepares for ‘Patent Cliff’ as Blockbuster Drug Revenue Losses Loom, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.tradeandindustrydev.com/industry/bio-pharmaceuticals/big-pharma-prepares-patent-cliff-blockbuster-drug-34694

- Why are biosimilars much more complex than generics? – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6388725/

- The Economics of Generic Drug Shortages: The Limits of Competition, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.20241420

- US drug supply chain exposure to China – Brookings Institution, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/us-drug-supply-chain-exposure-to-china/

- Streamlining the Generic Drug Supply Chain: Best Practices …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/streamlining-the-generic-drug-supply-chain-best-practices/

- Domestic pharma industry may face setback if US imposes tariffs, accessed August 1, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/domestic-pharma-industry-may-face-setback-if-us-imposes-tariffs/articleshow/123002989.cms

- Consumers are now actively seeking generic substitutes for branded medicines: Sujit Paul, Zota Healthcare, accessed August 1, 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/entrepreneurship/consumers-are-now-actively-seeking-generic-substitutes-for-branded-medicines-sujit-paul-zota-healthcare/articleshow/122987675.cms

- How India took over the global medicine market | TBIJ, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2025-04-16/indias-drugs-industry-global-medicine-market

- Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Vulnerabilities: Third-party Risk Lessons Applicable Across Industries | Censinet, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.censinet.com/perspectives/pharmaceutical-supply-chain-vulnerabilities-third-party-risk-lessons-applicable-across-industries

- The Future of Generics – UW School of Pharmacy, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pharmacy.wisc.edu/2025/06/11/the-future-of-generics/

- Five Trends Reshaping Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Partnerships | Insights & Resources, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/04/insights-lifesciences-hltc-five-trends-reshaping-pharmaceutical

- Identifying and addressing vulnerabilities in the upstream medicines …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.usp.org/supply-chain/build-resilience-and-reduce-drug-shortages

- A Primer on Sourcing CROs and CDMOs in the Life Sciences Industry, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.outboundpharma.com/post/sourcing-cros-and-cdmos-in-the-life-science-industry

- CROs vs. CMOs vs. CDMOs: Understanding the Differences in Outsourcing Partners, accessed August 1, 2025, https://cellcarta.com/science-hub/cro-vs-cmo-vs-cdmo/

- CROs vs CMOs, and CDMOs: What’s the difference between the three? – Patheon, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.patheon.com/us/en/insights-resources/blog/cdmo-vs-cmo-vs-cro.html

- What is a CDMO & How Do They Help Pharma Companies? – Medical Packaging Inc, accessed August 1, 2025, https://medpak.com/cdmo-pharma/

- Challenges of Integrating Biosimilars Into Clinical Practice – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7857316/

- The impact of biosimilars on biologic drug distribution models, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-biosimilars-on-biologic-drug-distribution-models/

- The Economics of Biosimilars – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4031732/

- Top 5 Challenges Faced By Biosimilars: Navigating the Complex …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/top-5-challenges-faced-biosimilars/

- FDA Drug Competition Action Plan, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/fda-drug-competition-action-plan

- Addressing Barriers to the Development of Complex Generics: | USP, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/ea83b_complex-generics_wp_2023-07_v3.pdf

- Complex Generics News – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/complex-generics-news

- FDA Drug Competition Action Plan | Maximizing scientific and regulatory clarity with respect to complex generic drugs, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/fda-drug-competition-action-plan-maximizing-scientific-and-regulatory-clarity-respect-complex

- Understanding the Lifecycle of Generic Drugs: From Patent Cliffs to …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/understanding-the-lifecycle-of-generic-drugs-from-development-to-market-impact/

- Product-Specific Guidances for Generic Drug Development – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidances-drugs/product-specific-guidances-generic-drug-development

- The Center for Research on Complex Generics – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/center-research-complex-generics

- Case Studies on Successful Biosimilar Launches | Genefic, accessed August 1, 2025, https://genefic.com/case-studies-on-successful-biosimilar-launches-transforming-healthcare/

- Why collaboration is important in the biosimilars market, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/why-collaboration-important-biosimilars-market

- Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Technology and Drug Delivery Design – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10385763/

- The Potential of Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical Innovation: From Drug Discovery to Clinical Trials – MDPI, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/18/6/788

- How Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) Concepts …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://witii.us/how-artificial-intelligence-ai-and-machine-learning-ml-concepts-are-transforming-generic-pharmaceuticals/

- 8 Use Cases For Data Analytics In Pharmaceutical Industry – Polestar Solutions, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.polestarllp.com/blog/analytics-in-pharmaceutical-companies

- 7 Emerging Generative AI Use Cases in Pharma – Edvantis, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.edvantis.com/blog/generative-ai-in-pharma/

- Collaborative intelligence: How AI partnerships are shaping the future of drug development, accessed August 1, 2025, https://sanogenetics.com/resources/blog/collaborative-intelligence-how-ai-partnerships-are-shaping-the-future-of-drug-development

- How pharma can benefit from using GenAI in drug discovery | EY – US, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/life-sciences/how-pharma-can-benefit-from-using-genai-in-drug-discovery

- 12 AI drug discovery companies you should know about in 2025 – Labiotech.eu, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.labiotech.eu/best-biotech/ai-drug-discovery-companies/

- Immunai Collaborates with Teva to Enhance Clinical Decision Making in Clinical Trials in Immunology & Immuno-oncology – FirstWord Pharma, accessed August 1, 2025, https://firstwordpharma.com/story/5912600

- Insilico collaborates with Teva on AI system for target discovery – EurekAlert!, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/777014

- The Future of Medicine is Now: 8 Ways Teva is Accelerating Healthcare Innovation Through AI, Advanced Devices, and Global Collaboration, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.tevapharm.com/news-and-media/feature-stories/the-future-of-medicine-is-now-8-ways-teva-is-accelerating-healthcare-innovation-through-ai-advanced-devices-and-global-collaboration/

- Teva and Immunai partner to improve clinical decision making – PharmaTimes, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pharmatimes.com/news/teva-and-immunai-partner-to-improve-clinical-decision-making/

- AI Innovation in Life Sciences: Teva’s Use Cases – Veeva Systems, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.veeva.com/customer-stories/ai-innovation-in-life-sciences-teva-use-cases/

- Artificial Intelligence for Drug Development – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder/artificial-intelligence-drug-development

- Continuous Manufacturing in Pharma: FDA Perspective – Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI), accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/2019/09/continuous-manufacturing-in-pharma-fda-perspective/

- Integrated Continuous Pharmaceutical Technologies—A Review | Organic Process Research & Development – ACS Publications, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00504

- Review: Continuous Manufacturing of Small Molecule Solid Oral Dosage Forms – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8400279/

- Accelerating adoption of pharmaceutical continuous … – USP, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/supply-chain/accelerating-continuous-manufacturing-white-paper.pdf

- Continuous Manufacturing in Pharmaceuticals: Implications for the Generics Market, accessed August 1, 2025, https://drug-dev.com/continuous-manufacturing-continuous-manufacturing-in-pharmaceuticals-implications-for-the-generics-market/

- Flow state: The evolving shape of continuous manufacturing, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.pharmamanufacturing.com/all-articles/article/55295669/flow-state-the-evolving-shape-of-continuous-manufacturing

- Taking a collaborative approach to continuous pharmaceutical …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/article/80580/collaborative-continuous-manufacturing/

- Evotec and Sandoz evolve their strategic partnership and agree on potential sale of Just – Evotec Biologics Toulouse site, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.evotec.com/en/news/evotec-and-sandoz-evolve-their-strategic-partnership-and-agree-on-potential-sale-of-just-evotec-biologics-toulouse-site