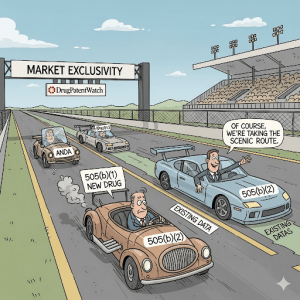

In the relentless and high-stakes world of pharmaceutical development, the path from molecule to market is fraught with peril. On one side lies the monumental undertaking of the traditional New Drug Application (NDA) under section 505(b)(1) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act—a decadelong, multi-billion-dollar odyssey to bring a new chemical entity (NCE) to patients.1 On the other side is the hyper-competitive, low-margin arena of generic drugs, governed by the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) under section 505(j), where innovation is constrained by the rigid requirement of “sameness” to a reference product. For decades, these two paths defined the strategic options for drug developers: either embark on a high-risk, high-reward quest for novelty or enter the crowded fray of commoditized copies.

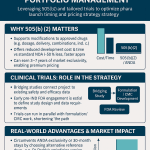

But what if there were a third way? A strategic middle ground that combines the speed and cost-efficiency of leveraging existing knowledge with the potential for meaningful innovation and market protection? This is the promise of the 505(b)(2) pathway.

Born from the landmark Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, the 505(b)(2) pathway was ingeniously designed to foster innovation without forcing the redundant and ethically questionable repetition of clinical studies on drugs whose safety and efficacy were already well-understood.4 It is, in essence, a hybrid NDA. It allows a sponsor to seek approval for a new drug product by submitting a complete dossier of safety and effectiveness, but with a critical twist: some of the necessary data can come from studies the applicant did not conduct and for which they do not have a right of reference.6 This could be the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) own previous findings of safety and effectiveness for an approved drug or data from published scientific literature.

This seemingly simple provision has ignited a strategic revolution. The 505(b)(2) pathway has evolved from a little-used regulatory footnote into a mainstream corporate strategy, now accounting for more than half of all NDA approvals in recent years.8 Its rise is a direct response to the dual pressures squeezing the industry: the astronomical cost of de novo drug development and the punishing price erosion of the “patent cliff.” It offers a lifeline for small and mid-sized companies, a powerful tool for life cycle management for established players, and a vital engine for the kind of incremental innovation that delivers tangible benefits to patients—safer formulations, more convenient dosing, and new uses for established therapies.

This report is designed as an exhaustive guide for business leaders, regulatory professionals, and portfolio managers seeking to harness the power of this pathway. We will deconstruct the regulatory framework, dissect the profound strategic advantages, explore the playbook of successful applications, and navigate the treacherous waters of development, intellectual property, and market access. For those looking to turn patent data into a competitive advantage, understanding the nuances of the 505(b)(2) process is no longer optional; it is the cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical strategy.

Deconstructing the Regulatory Trinity: 505(b)(1) vs. 505(b)(2) vs. 505(j)

To truly grasp the strategic value of the 505(b)(2) pathway, one must first understand its place within the FDA’s regulatory ecosystem. The FD&C Act provides three primary routes for the approval of small-molecule drugs, each with a distinct philosophy, set of requirements, and risk-reward profile. Think of it like constructing a building: you can design and build a completely new skyscraper from the ground up, you can manufacture a perfect prefabricated replica of an existing building, or you can perform a custom, high-value renovation on an existing structure. These are the worlds of 505(b)(1), 505(j), and 505(b)(2), respectively.

The Gold Standard: The 505(b)(1) New Drug Application (NDA)

The 505(b)(1) pathway is the traditional, comprehensive route for approving a drug containing a New Chemical Entity (NCE)—a molecule never before approved by the FDA.10 This is the pathway for true de novo innovation. A 505(b)(1) application is a “stand-alone” dossier, meaning the sponsor must generate and submit a complete package of data from its own investigations or from studies for which it has secured a right of reference.6

This is a monumental task. The data package must include:

- Full Nonclinical (Preclinical) Reports: Extensive studies in animals to establish the drug’s basic pharmacology and toxicology profile, including its potential for carcinogenicity.

- Full Clinical Reports: A complete sequence of human trials, typically progressing through three phases:

- Phase 1: Small studies in healthy volunteers to assess safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (PK).

- Phase 2: Studies in patients with the target disease to evaluate preliminary efficacy and determine the optimal dose.

- Phase 3: Large-scale, pivotal, “adequate and well-controlled” trials in thousands of patients to definitively demonstrate the drug’s safety and effectiveness for its intended use.

- Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC): Detailed information on the drug’s composition, manufacturing process, and quality control measures.

The 505(b)(1) pathway is the bedrock of pharmaceutical innovation, but it comes at a staggering price. The average cost to bring a new drug to market through this route is estimated to be approximately $2.6 billion, with timelines frequently stretching from 10 to 15 years.1 It is the highest-risk, highest-reward path, establishing the scientific and regulatory benchmark against which all other pathways are measured.

The Generic Pathway: The 505(j) Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA)

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the 505(j) pathway, created by the Hatch-Waxman Amendments to facilitate the approval of generic drugs. An ANDA is an “abbreviated” application because it does not require the sponsor to conduct new preclinical or clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy. Instead, it relies on the FDA’s prior finding that the original, innovator product—known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)—is safe and effective.6

The core philosophy of the 505(j) pathway is “sameness.” To be approved, a generic drug must be a pharmaceutical equivalent and bioequivalent duplicate of the RLD. This means it must have 7:

- The same active ingredient(s).

- The same route of administration.

- The same dosage form.

- The same strength.

- The same labeling (with certain permissible differences).

The key scientific hurdle for an ANDA is not to re-prove efficacy, but to demonstrate bioequivalence (BE) to the RLD. A BE study is typically a small clinical trial that shows the generic drug is absorbed into the bloodstream at a similar rate and to a similar extent as the brand-name drug.10 If BE is established, the FDA considers the generic to be therapeutically equivalent to the RLD, meaning it can be substituted by a pharmacist.

This pathway is highly efficient and low-cost, enabling the rapid entry of affordable medicines after the innovator’s patents and exclusivities expire. However, the stringent “sameness” requirement severely limits innovation. A proposed drug that differs from the RLD in its dosage form, strength, or formulation, or that requires new clinical studies to establish its safety or efficacy, generally cannot be approved as an ANDA.6

The Hybrid Innovator: The 505(b)(2) “Paper” NDA

The 505(b)(2) pathway masterfully occupies the space between the 505(b)(1) and 505(j) routes. It is legally classified as a New Drug Application, submitted under section 505(b)(1) and approved under 505(c), just like a traditional NDA. It requires the same high standard of evidence: full reports demonstrating safety and effectiveness.4 The revolutionary difference lies in the

source of that evidence. A 505(b)(2) application allows the sponsor to rely on data that they did not generate themselves and do not own—most commonly, the FDA’s previous findings for an approved RLD.4

This is why it’s often called a “Paper NDA”; it allows a sponsor to build their application, in part, on a foundation of existing scientific literature and regulatory precedent. This creates a pathway for approving drugs that are not exact generic copies but are also not entirely novel entities. Ideal candidates for the 505(b)(2) pathway are modified versions of existing drugs, such as those with 4:

- A new dosage form (e.g., changing a tablet to a liquid).

- A new strength.

- A new formulation (e.g., using different inactive ingredients or creating an extended-release version).

- A new route of administration (e.g., oral to injectable).

- A new indication (i.e., repurposing a drug for a new disease).

- A new combination of previously approved drugs.

However, this reliance on external data is not automatic. The defining feature—and the core strategic challenge—of a 505(b)(2) application is the requirement to establish a “scientific bridge” between the proposed new product and the existing data.7 The applicant must provide sufficient new data to scientifically justify the relevance of the RLD’s information to their modified product. This bridge must demonstrate that the changes made do not compromise the safety or effectiveness established for the original drug.

The nature of this bridge varies depending on the modification. For a minor formulation change, a comparative bioavailability study might be sufficient. For a change in the route of administration, more extensive PK studies and potentially some nonclinical toxicology studies might be needed.17 For a new indication, the sponsor will likely need to conduct pivotal clinical trials for that new use, but can still rely on the RLD’s extensive nonclinical and safety database, saving immense time and resources.

The success of a 505(b)(2) application, therefore, hinges not just on data collection, but on data integration and scientific argumentation. The sponsor must construct a compelling narrative that convinces the FDA that what is known about the reference drug is applicable to their modified product, and that any differences are well-characterized, justified, and safe. It is a sophisticated exercise in regulatory science that, when executed correctly, unlocks tremendous strategic value.

Table 1: FDA Drug Approval Pathways at a Glance

To crystallize these distinctions, the following table provides a side-by-side comparison of the key features of each pathway, offering a quick reference for strategic decision-making.

| Feature | 505(b)(1) NDA | 505(b)(2) NDA | 505(j) ANDA |

| Purpose | Approval of a New Chemical Entity (NCE) or major new use. | Approval of a modified or repurposed drug that differs from an approved product. | Approval of a generic copy of an approved drug. |

| Data Source | All studies conducted by or for the sponsor, or with right of reference. | Hybrid: a mix of sponsor-conducted studies and reliance on public data or FDA’s findings for a listed drug. | Full reliance on the FDA’s prior finding of safety and efficacy for the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). |

| Key Study Req. | Full nonclinical program and full Phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials. | “Bridging studies” to link to existing data (e.g., PK/BE, toxicology, smaller clinical trials). | Bioequivalence (BE) study to demonstrate sameness to the RLD. |

| Typical Dev. Cost | >$1 billion, with some estimates at $2.6 billion.1 | $15 million – $100 million, depending on the extent of new studies required.1 | Significantly lower than NDA pathways, focused on formulation and BE studies. |

| Typical Dev. Time | 10-15 years. | 3-5 years. | Shorter than NDA pathways, focused on post-patent expiry entry. |

| Market Exclusivity | • 5-year NCE Exclusivity • 3-year New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity • 7-year Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) | • Can qualify for 3-year, 5-year (if NCE), or 7-year (if orphan) exclusivity.4 | • 180-day generic drug exclusivity for the first applicant to file a Paragraph IV challenge. |

| Innovation Scope | High (Novel molecule, new mechanism of action). | Moderate (Incremental but often clinically meaningful improvements). | Low (Replication of an existing product). |

The Strategic Imperative: Why the 505(b)(2) Pathway is Gaining Momentum

The dramatic surge in 505(b)(2) applications is no accident; it is a calculated response to the powerful economic and competitive forces reshaping the pharmaceutical industry. For companies seeking to innovate without betting the farm on a high-risk NCE, the pathway offers a compelling business case built on three pillars: drastically reduced development costs and timelines, a lower risk profile, and the potential for valuable market exclusivity.

The Economic Advantage: Drastically Reduced Development Costs and Timelines

The most immediate and quantifiable benefit of the 505(b)(2) pathway is the profound savings in time and money. By allowing developers to leverage a vast repository of existing safety and efficacy data, the FDA effectively eliminates the need to “reinvent the wheel” with duplicative, expensive, and time-consuming studies.4

The numbers are stark. As noted, a traditional 505(b)(1) program can cost upwards of $2.6 billion and take 10 to 15 years to complete.1 In sharp contrast, a 505(b)(2) development program can often be executed for a fraction of that cost, with estimates ranging from as low as $3 million for programs requiring no new clinical trials to $50-100 million for those that do.1 This can represent a cost reduction of up to 50% or more compared to the traditional route. The timeline is similarly compressed, with development often completed in 3 to 5 years. A well-defined 505(b)(2) program can potentially save one to two years of preclinical research and five to ten years of clinical research.

It is crucial, however, to understand where these savings originate. A common misconception is that the FDA’s review time for a 505(b)(2) application is significantly shorter than for a 505(b)(1). While some 505(b)(2)s may receive priority review, analyses have shown that the median approval times for 505(b)(2) and 505(b)(1) applications can be quite similar. The real advantage lies in the vastly reduced scope of the development program. The time and cost are saved by conducting smaller, fewer, or sometimes no new nonclinical and pivotal clinical trials, not by an abbreviated regulatory review clock.

This economic transformation does more than just improve the ROI for large corporations. It fundamentally alters the competitive landscape by lowering the barrier to entry for innovation. The prohibitive cost of 505(b)(1) development has historically concentrated novel drug creation in the hands of a few large, well-capitalized companies. The 505(b)(2) pathway, with its more manageable financial and risk profile, acts as a democratizing force. It empowers smaller, mid-sized, and even virtual pharmaceutical companies to develop and commercialize proprietary, value-added medicines. In fact, data has shown that for many smaller companies, the 505(b)(2) pathway provides their first-ever FDA-approved product, demonstrating its role in fostering a more diverse and dynamic innovation ecosystem.

The Shield of Exclusivity: Securing a Defensible Market Position

While cost and time savings are compelling, they would be of little strategic value without a mechanism to protect the resulting innovation from immediate competition. This is where the 505(b)(2) pathway’s second major advantage comes into play: the potential to secure valuable periods of market exclusivity. Unlike the 505(j) pathway, which typically offers only a 180-day exclusivity period for the first generic challenger, a 505(b)(2) approval can come with the same powerful exclusivities available to a 505(b)(1) NDA.3

Market exclusivity is a statutory provision granted by the FDA upon approval of a drug that meets certain criteria. It is distinct from patent protection and runs concurrently with it. During a period of exclusivity, the FDA is prohibited from approving certain other applications, providing a crucial window for the sponsor to establish their product in the market and recoup their R&D investment. For a 505(b)(2) applicant, this is a “major windfall” that creates a significant competitive advantage.3

The key exclusivity periods available to 505(b)(2) products are detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Market Exclusivity Opportunities for 505(b)(2) Products

| Exclusivity Type | Duration | Qualifying Criteria | Strategic Implication |

| New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity | 3 Years | The application must contain reports of new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability or bioequivalence studies) that were essential to the approval of the application. | This is the most common type of exclusivity for 505(b)(2) products. It protects the specific change or new indication that was supported by the new clinical data. It prevents the FDA from approving a subsequent 505(b)(2) or ANDA for the same change. |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity | 5 Years | The application is for a drug that contains an active moiety that has never been approved by the FDA in any other application. | While less common, it is possible for a 505(b)(2) product (e.g., a new salt or ester of a previously unapproved active moiety) to qualify as an NCE. This is a powerful exclusivity that blocks the submission of any ANDA or 505(b)(2) referencing the drug for four years, and approval for five years.3 |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) | 7 Years | The drug has been granted orphan designation by the FDA and is approved to treat a rare disease or condition (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.). | This is the longest period of exclusivity and provides very strong market protection for the approved orphan indication. The 505(b)(2) pathway is an excellent tool for developing treatments for rare diseases. |

| Pediatric Exclusivity | 6 Months | Granted to a sponsor who conducts and submits pediatric studies on the drug in response to a Written Request from the FDA. | This is not a stand-alone exclusivity. Instead, it acts as an extension, adding six months to all existing patent and exclusivity periods for the drug’s active moiety, making it a highly valuable incentive. |

Strategically designing a development program with these exclusivities in mind is paramount. The decision to conduct a particular clinical study may be driven not only by the need to satisfy a regulatory requirement for approval but also by the desire to trigger a valuable 3-year exclusivity period. This transforms the clinical development plan from a mere scientific checklist into a sophisticated commercial strategy designed to maximize the product’s protected market life.

The Innovator’s Playbook: Key Applications of the 505(b)(2) Pathway

The true power and versatility of the 505(b)(2) pathway are best understood through its diverse applications. It is a flexible toolkit that allows developers to make targeted, clinically meaningful improvements to existing medicines. From our analysis of hundreds of 505(b)(2) approvals, several key “plays” have emerged as the most common and commercially successful strategies. In fact, from 2010 to 2020, the vast majority of the 570 drugs approved via this pathway fell into categories like new formulations (42.4%), new dosage forms (26.4%), and new combinations (13.1%). Let’s explore the innovator’s playbook.

New Formulations: Enhancing Performance and Patient Experience

One of the most frequent uses of the 505(b)(2) pathway is to develop a new formulation of an existing drug.9 This isn’t just about changing the color or flavor; it involves sophisticated pharmaceutical science to alter a drug’s composition to achieve a specific clinical goal. This could mean changing or removing an excipient (an inactive ingredient) to improve safety, creating a ready-to-dilute or ready-to-use solution to simplify administration for healthcare providers, or engineering advanced drug delivery systems.6

These modifications are often designed to solve a known problem with the original product. For example, a drug with a narrow therapeutic window (where the effective dose is close to the toxic dose) or high pharmacokinetic variability can be reformulated to provide more consistent drug levels, enhancing its safety profile.

A stellar example of this strategy is Bendeka® (bendamustine HCl). The original reference drug, Treanda®, was an effective anti-cancer agent but was supplied as a lyophilized powder that had to be reconstituted in a specific diluent before intravenous (IV) administration. This process was time-consuming for pharmacy staff and came with a warning against use with certain plastic components found in closed-system transfer devices. The developers of Bendeka used the 505(b)(2) pathway to create a new liquid formulation that was ready-to-use, contained different excipients (including a different solubilizing agent), and was compatible with those plastic components. This seemingly simple change addressed a significant unmet need in the clinical setting, providing a clear point of differentiation and commercial value.

Advanced formulation technologies, such as coated multiparticulate (MP) systems, are also well-suited for the 505(b)(2) pathway. These technologies can be used to create sprinkle capsules or oral powders that are easier for pediatric, geriatric, or dysphagic (difficulty swallowing) patients to take, improving compliance. They can also be designed to modify drug release, for instance, to bypass the stomach and release in the intestine, or to eliminate food-effect variability, simplifying dosing instructions for patients.

New Dosage Forms: Reimagining Drug Delivery

Closely related to new formulations is the development of a new dosage form. This involves changing the physical form in which the drug is delivered to the patient. The goal is often to improve patient convenience, adherence, or to enable a different clinical use case. Examples include 4:

- Transforming a solid oral tablet into a liquid formulation for patients who cannot swallow pills.

- Developing a controlled-release or extended-release (ER) version of an immediate-release drug to allow for less frequent dosing (e.g., once-daily instead of twice-daily).

- Creating a transdermal patch for continuous drug delivery through the skin.

The fictional case study of GT123 provides a clear illustration. The reference drug, AB456, was an effective analgesic but had to be administered as a subcutaneous (SQ) injection four times a day. The developer of GT123 used the 505(b)(2) pathway to create an oral extended-release capsule that only needed to be taken once daily. This change from an inconvenient, frequent injection to a simple, once-daily pill represented a massive improvement in patient convenience and quality of life, creating a strong rationale for its use.

These changes are not merely for marketing. A switch to an extended-release dosage form can smooth out the peaks and troughs in drug concentration, potentially reducing side effects associated with high peak levels and improving efficacy by maintaining therapeutic levels for longer. This is a powerful life cycle management strategy, allowing a company to launch a “next-generation” version of their product with improved features and its own period of market protection.

New Routes of Administration (RoA): Finding a Better Way In

Changing the route of administration (RoA) is another powerful application of the 505(b)(2) pathway. This involves developing a way to get the drug into the body that is different from the original product, for example, moving from an oral drug to an injectable, a topical cream, or an inhaled product.14 The strategic driver is often to overcome a limitation of the original RoA or to enable faster or more targeted drug delivery.

A landmark public health success story enabled by this strategy is Narcan® Nasal Spray. The active ingredient, naloxone, is a life-saving opioid antagonist used to reverse overdoses. For decades, it was available primarily as an injectable product, which was difficult for untrained bystanders or first responders to administer in a high-stress emergency. The developer used the 505(b)(2) pathway, cross-referencing the safety and efficacy data from its own approved injectable naloxone product, to gain approval for an easy-to-use intranasal spray. This change in RoA made the drug accessible to a much wider range of individuals, undoubtedly saving countless lives.

Another example is Sustol® (granisetron), an anti-nausea medication for chemotherapy patients. The reference drug, Kytril®, was an IV injection. The makers of Sustol developed a new extended-release subcutaneous injection using a novel polymer. This new RoA and formulation provided sustained release of the drug over several days, offering a more convenient option for patients than daily IV infusions. However, this case also highlights the complexities: the significant changes in RoA, formulation (using a novel polymer), and pharmacokinetics necessitated a much larger and more complicated development program, closer to a 505(b)(1) in scope, to support approval.

New Indications: Teaching an Old Drug New Tricks

Perhaps one of the most scientifically exciting and commercially valuable uses of the 505(b)(2) pathway is for drug repurposing, also known as repositioning. This is the process of taking a drug that is already approved for one disease and getting it approved for a completely new therapeutic indication.4 The scientific rationale is that many drugs have biological effects beyond their original intended target, which can be harnessed to treat other conditions.

The 505(b)(2) pathway is tailor-made for this. A developer seeking a new indication can rely heavily on the comprehensive nonclinical toxicology and safety database of the original approved drug, since this information is generally applicable regardless of the disease being treated. This allows them to focus their own development program on the essential new clinical trials needed to prove the drug’s efficacy in the new patient population.19 This dramatically reduces the risk, cost, and time compared to developing a new drug from scratch for that indication.

A well-known example is Contrave, a weight-loss medication. It is a fixed-dose combination of two older drugs: naltrexone (approved for opioid and alcohol dependence) and bupropion (approved for depression and smoking cessation). The developer, Orexigen Therapeutics, used the 505(b)(2) pathway, relying on the extensive existing data for the individual components and conducting new clinical trials specifically to demonstrate the combination’s effectiveness for weight management.

Combination Products: The Power of Synergy

The 505(b)(2) pathway is the primary route for approving two major types of combination products, a category that now accounts for nearly 30% of all 505(b)(2) approvals.

- Fixed-Dose Combinations (FDCs): These products combine two or more active ingredients into a single dosage form (e.g., one pill). FDCs are common in therapeutic areas like HIV, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, where patients often need to take multiple medications. Combining them into a single pill can dramatically improve patient adherence by reducing the “pill burden,” which in turn can lead to better clinical outcomes. The aforementioned Contrave is an example of an FDC.

- Drug-Device Combinations: These products consist of a drug constituent part and a device constituent part that are physically or chemically combined to create a single entity. Examples are ubiquitous and include 16:

- Prefilled syringes and auto-injectors (e.g., EpiPen®).

- Insulin injector pens.

- Metered-dose inhalers for asthma.

- Transdermal patches.

For these products, the FDA assigns a lead review center based on the product’s Primary Mode of Action (PMOA)—the primary mechanism by which it achieves its therapeutic effect.16 If the PMOA is determined to be the drug, the application is reviewed by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and is often eligible for the 505(b)(2) pathway. The developer can leverage existing data on the drug component while providing new data on the performance and safety of the combined product.17

Prodrugs: A Smarter Molecule

A more scientifically sophisticated strategy involves the creation of a prodrug. A prodrug is a pharmacologically inactive compound that, after administration, is converted within the body (metabolized) into a pharmacologically active drug. This approach is used to overcome undesirable properties of the parent drug.

The benefits of a prodrug strategy are numerous and can lead to significant clinical improvements :

- Improved Absorption/Bioavailability: If a parent drug is poorly soluble in water, it may not be well-absorbed when taken orally. A prodrug can be designed with a more soluble chemical group attached, which is then cleaved off after absorption to release the active drug.

- Enhanced Lipophilicity: Conversely, to cross certain biological barriers like the blood-brain barrier, a drug needs to be more fat-soluble (lipophilic). A prodrug can be designed to be more lipophilic to improve delivery to specific sites.

- Site-Specific Targeting: Prodrugs can be engineered to be activated only by specific enzymes that are present in a target tissue (e.g., a tumor), concentrating the drug’s effect where it’s needed most and reducing toxicity elsewhere.

- Prolonged Duration of Action: If a parent drug is metabolized and eliminated too quickly, a prodrug can be designed to be more resistant to this rapid breakdown, extending its half-life and allowing for less frequent dosing.

A prime example is aripiprazole lauroxil (Aristada™), an extended-release injectable suspension for schizophrenia. It is a prodrug of aripiprazole (the active ingredient in the blockbuster oral drug Abilify®). This prodrug formulation allows for very infrequent dosing (monthly or every six weeks), which is a major advantage for improving adherence in patients with schizophrenia. Because it was a modification of a well-known molecule, it was approved via the 505(b)(2) pathway, leveraging the vast safety and efficacy data of oral aripiprazole.

Each of these “plays” demonstrates how the 505(b)(2) pathway serves as a flexible framework for value creation. These are not minor tweaks; they are targeted innovations that can improve safety, enhance efficacy, boost patient compliance, and ultimately extend and improve lives, all while providing a commercially viable path to market.

From Concept to Submission: Navigating the 505(b)(2) Development Program

While the 505(b)(2) pathway offers a streamlined route to market, it is by no means an easy one. Success requires a bespoke, meticulously planned strategy that is different for every product. Unlike the more prescriptive 505(b)(1) or 505(j) pathways, there is no preset playbook. Navigating this path successfully requires deep regulatory expertise, a proactive approach to engaging with the FDA, and a sharp focus on three critical areas: candidate selection, bridging strategy, and CMC.

The First Step: Candidate Identification and Strategic Assessment

The journey begins long before any studies are conducted. The selection of a 505(b)(2) candidate is a critical strategic decision that must balance scientific feasibility, medical need, and commercial opportunity. Rushing into development with a poorly chosen candidate is a recipe for failure. A thorough initial assessment should address several key questions 4:

- Unmet Medical Need: Does the proposed modification solve a real-world problem? Does it offer a meaningful clinical benefit over existing therapies? Payers and physicians will not embrace a “me-too” product with a trivial change.4

- Market Opportunity: Is there a clear and commercially viable patient population for the new product? What is the competitive landscape? Will the product be able to command a price that justifies the development investment?

- Feasibility: Is the proposed change technically achievable? Can the new formulation or delivery system be manufactured consistently at scale?

- Data Landscape: What existing data is available for the reference drug? Is there high-quality published literature that can be leveraged? The strength and completeness of the existing data will directly impact the scope of the new studies required.

- Regulatory & IP Assessment: What is the most likely regulatory path? What will the bridging requirements be? What is the patent situation for the reference drug, and is there a clear path to establish new, defensible intellectual property for the modified product?

This initial assessment phase is also the time to begin mapping out the regulatory strategy, including identifying the most appropriate RLD(s) to reference and assessing eligibility for any of the FDA’s expedited review programs, such as Fast Track or Breakthrough Therapy designation, which can further accelerate timelines.

The Linchpin of the Application: Designing the Right Bridging Strategy

If candidate selection is the foundation, the bridging strategy is the architectural blueprint of the entire 505(b)(2) program. As previously discussed, the “bridge” is the collection of new data that scientifically connects your modified product to the safety and efficacy data of the reference drug or published literature. An elegantly designed, scientifically sound bridging strategy is the single most important factor in realizing the time and cost savings of the pathway. A flawed or inadequate bridge can cause the entire program to collapse, forcing the sponsor to conduct the very large-scale clinical trials they sought to avoid.

The design of the bridge is highly dependent on the nature of the modification. The central players in this process are often the clinical pharmacologists, who are experts in evaluating the body’s absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of drugs.17 Their role is to:

- Evaluate the adequacy of the existing data.

- Identify any gaps that must be filled with new studies.

- Design the most efficient studies possible to fill those gaps.

For many 505(b)(2) products, the core of the bridging strategy is a comparative bioavailability (BA) or bioequivalence (BE) study.17 These studies compare the pharmacokinetic profile of the new product to that of the RLD. If the new product can be shown to deliver the active ingredient to the bloodstream in a comparable way, the sponsor can often successfully argue that the extensive efficacy and safety findings of the RLD are relevant, thereby “bridging” to that data. The Bendeka® case study is a perfect example, where a successful comparative BA study was the key that unlocked reliance on Treanda’s data.

However, not all changes can be bridged by PK alone. A new indication will always require new efficacy trials. A change in RoA or the use of novel excipients may require new nonclinical toxicology studies to ensure the safety of the new route or ingredient. The key is to do no more work than is absolutely necessary. This is where advanced tools like PK modeling and simulation can play a critical role, sometimes replacing the need for an actual clinical study or optimizing the design of a study to reduce the number of patients or samples required.

Given the critical nature of the bridging strategy, the pre-Investigational New Drug (pre-IND) meeting with the FDA is arguably the most important milestone in the entire development program.16 This is the sponsor’s opportunity to present their overall development plan and, most importantly, their proposed bridging strategy to the agency for feedback. Gaining the FDA’s agreement on the plan at this early stage provides a clear roadmap and dramatically de-risks the program. Proceeding without this alignment is a high-stakes gamble that can lead to costly delays, clinical holds, or additional review cycles down the line.24 In fact, analysis of approval delays shows that issues with 505(b)(2) strategy and problems with bridging studies are among the most common and preventable reasons for applications requiring more than one review cycle.

Navigating Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC)

While much of the strategic focus in a 505(b)(2) program is on the abbreviated clinical plan, it is a fatal mistake to underestimate the importance of Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC). The CMC section of an NDA is where the sponsor provides the blueprint for producing a consistent, high-quality drug product. For a 505(b)(2), where the differentiation from the RLD often lies in the formulation or delivery system, the CMC package is not just a regulatory requirement; it is central to the product’s value proposition and a major source of potential risk.

The FDA’s standards for CMC are just as rigorous for a 505(b)(2) as for a 505(b)(1). The sponsor must demonstrate complete control over the manufacturing process, from the quality of the starting materials to the stability of the final drug product. This can be particularly challenging in the compressed timelines of a 505(b)(2) program.

One analysis of 505(b)(2) approval delays revealed a shocking outlier: a product that was deemed approvable on clinical grounds in its first review cycle was ultimately delayed for nearly eight years and required four additional review cycles due to major, unresolved CMC deficiencies. This serves as a stark warning: clinical success means nothing if you cannot reliably manufacture the product to the FDA’s standards.

Supply chain management is another critical CMC-related challenge. Sponsors must secure a reliable supply of high-quality Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and excipients. Even minor, seemingly insignificant differences in the physical properties of an API from a new supplier—such as its particle size distribution or bulk density—can dramatically alter the performance of the final dosage form, potentially invalidating bridging studies and forcing a costly redevelopment of the product. Furthermore, as companies race to meet accelerated timelines, they may hastily select manufacturing partners who are not a good fit, for example, choosing a large-scale manufacturer for a product with small volume needs, leading to poor service and prioritization.

In short, a successful 505(b)(2) program requires a holistic approach where the CMC and supply chain strategy is developed in parallel with the clinical and regulatory strategy, not as an afterthought.

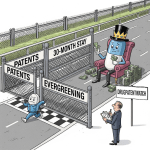

The Patent Tightrope: Intellectual Property, Litigation, and Competitive Intelligence

Successfully navigating the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway is only one part of the equation. The other, equally critical part is managing the complex and often contentious landscape of intellectual property (IP). A 505(b)(2) product, by its nature, exists in close proximity to an innovator product, which is almost always protected by a thicket of patents. This creates a high-wire act where the developer must simultaneously avoid infringing existing patents while creating and defending their own new IP.

The Certification Game: Paragraph IV and the Risk of Litigation

When a 505(b)(2) application relies on the FDA’s findings for an RLD, the applicant must address the patents listed for that RLD in the FDA’s “Orange Book.” For each relevant patent, the applicant must make one of several certifications. The most consequential of these is the Paragraph IV (PIV) certification. A PIV certification is a declaration by the applicant that a listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by their proposed product.

Filing a PIV certification is not a step to be taken lightly. It is an act that initiates a formal, high-stakes legal process. The 505(b)(2) applicant must notify the patent holder of their filing. The patent holder then has 45 days to sue the applicant for patent infringement. If a lawsuit is filed, it automatically triggers a 30-month stay of the FDA’s approval of the 505(b)(2) application (or until the court case is resolved, whichever comes first). This effectively puts the product’s launch on hold while the parties battle it out in court.

This PIV process creates a fundamental tension at the heart of many 505(b)(2) strategies. To secure approval from the FDA, the applicant often argues that their product is similar enough to the RLD to justify bridging to its data. However, to win a patent lawsuit (or to secure their own new patent from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, or PTO), the same applicant must argue that their product is different enough from the prior art (which includes the RLD) to be considered novel and non-obvious.

Managing these two, often contradictory, narratives is a delicate balancing act that, if mismanaged, can have catastrophic consequences. The case of Belcher Pharmaceuticals v. Hospira serves as a cautionary tale. Belcher had obtained approval for an injectable epinephrine formulation via the 505(b)(2) pathway, referencing a prior product from a company called Sintetica. Belcher also obtained a patent on its formulation. In the subsequent patent litigation against Hospira, the court found that Belcher’s Chief Science Officer, who was deeply involved in the FDA submission, knew that the Sintetica product was highly relevant prior art but had failed to disclose it to the PTO during the patent prosecution process. The court concluded this was “inequitable conduct” with an intent to deceive the patent office. As a result, Belcher’s patent was rendered completely unenforceable, wiping out its primary tool for protecting its product from competition.

This case underscores a critical principle: a successful 505(b)(2) strategy demands a deeply integrated regulatory and IP team from the earliest stages of development. The arguments made to the FDA and the PTO must be consistent and transparent. Information that is material to patentability that is discovered during the regulatory process must be shared with the patent prosecution team. Failure to maintain this “duty of candor” to the PTO can destroy the very IP that the company is counting on to protect its investment.

Some companies may use the 505(b)(2) pathway to cleverly navigate around IP hurdles. For example, if a first-to-file generic has 180-day exclusivity that is blocking other ANDA filers, a company could potentially launch a slightly modified product via the 505(b)(2) pathway to enter the market sooner, as Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories did with its version of amlodipine.

The Role of Business Intelligence: Using DrugPatentWatch to Navigate the Landscape

In this complex and high-stakes environment, “going in blind” is not a viable strategy. Before investing millions of dollars in a 505(b)(2) program, a company must have a comprehensive understanding of the competitive and intellectual property landscape. This is where specialized business intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable tools.

These platforms are not a luxury; they are a critical component of strategic planning and due diligence. They provide the actionable intelligence needed to make informed decisions at every stage of the process.36 For a company considering a 505(b)(2) project, services like

DrugPatentWatch can help to 1:

- Identify Opportunities: By providing detailed data on drug patent expiration dates, companies can identify molecules that are becoming vulnerable to competition, creating windows of opportunity for value-added 505(b)(2) products.

- Assess Risk: A thorough analysis of the RLD’s patent portfolio is essential. Companies can study the claims of existing patents to design around them, minimizing the risk of infringement litigation. Understanding past litigation history involving the RLD’s patents can also provide valuable insights into how those patents have held up in court.

- Monitor Competitors: The 505(b)(2) space is increasingly active. It is crucial to monitor the activities of other companies, including tracking their 505(b)(2) filings and anticipating their approvals. This intelligence helps a company understand the competitive dynamics and adjust its own strategy accordingly.

- Strengthen New IP: By providing access to databases of expired and existing patents, these platforms allow companies to research the prior art thoroughly. This helps in drafting stronger, more defensible patent applications for their own new formulations, combinations, or uses, and in developing robust arguments for their novelty and non-obviousness.

- Inform Portfolio Management: For both generic and specialty pharmaceutical companies, this intelligence is vital for managing their development pipeline. It helps them decide which 505(b)(2) projects to pursue, which to prioritize, and which to avoid based on a clear-eyed assessment of the market potential and IP risks.

In essence, leveraging a comprehensive business intelligence platform transforms the 505(b)(2) strategy from a series of isolated decisions into a data-driven, integrated process. It allows companies to connect the dots between regulatory pathways, patent landscapes, and market dynamics, ultimately increasing the probability of both regulatory and commercial success.

Beyond Approval: The Gauntlet of Market Access and Reimbursement

For many development teams, securing FDA approval feels like crossing the finish line. In reality, it is only the halfway point. In today’s healthcare environment, regulatory approval does not guarantee commercial success. A 505(b)(2) product, once approved, faces a second, equally challenging gauntlet: convincing payers—the insurance companies, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and government bodies like the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)—to provide favorable coverage and reimbursement. Failure at this stage can render an innovative, FDA-approved product a commercial non-starter.

The Payer’s Perspective: “Is This Meaningful Innovation or Just a Tweak?”

Payers are the gatekeepers to the market, and they evaluate new drugs through a lens of cold, hard value. Their primary question is not simply “Is this drug safe and effective?” (the FDA’s question), but rather, “Does this new drug provide a benefit that is worth its cost compared to the available alternatives?”. For 505(b)(2) products, which are often priced higher than the generic versions of their reference drugs, this scrutiny is particularly intense.

When a 505(b)(2) product comes up for formulary review, payers will ask a series of tough questions to determine its place in therapy :

- Clinical Value: Is the claimed improvement clinically meaningful? Does a new formulation that reduces a minor side effect justify a major price increase? Is the change from twice-daily to once-daily dosing a true clinical necessity or just a convenience?

- Differentiation: How unique is the product? Is it a true step-change in care, or is it entering a market that is already heavily genericized?

- Target Population: Does the product benefit all patients, or only a small, specific sub-population?

- Cost-Effectiveness: What is the total cost of care with the new product compared to the old one?

If a developer cannot provide compelling answers to these questions, backed by solid clinical and economic data, the consequences can be severe. The payer may relegate the product to a non-preferred tier on their formulary, requiring high patient co-pays that suppress uptake. They might impose restrictive prior authorization criteria. Or, in the worst-case scenario, they may simply refuse to cover the drug at all. This is why it is critical for 505(b)(2) developers to think like a payer from the very beginning of the development process and to design their product and their clinical trials to generate the evidence needed to demonstrate clear value.

The J-Code Revolution: How a CMS Policy Shift Changed the Game

Nowhere is the collision of regulatory and reimbursement strategy more apparent than in the recent, dramatic shift in CMS policy regarding Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) J-codes. This change has fundamentally altered the commercial calculus for many 505(b)(2) products, especially those administered in a physician’s office or hospital outpatient setting (i.e., “buy-and-bill” drugs).

Historically, CMS had a practice of “bundling” most 505(b)(2) products under the same J-code as their reference drug and its generic equivalents.13 This meant they were all reimbursed based on a single, blended Average Sales Price (ASP), effectively forcing the 505(b)(2) product to compete on price with low-cost generics.

This all changed in 2022. Following a complaint from a pharmaceutical company, CMS re-examined its policy and issued a landmark ruling: a 505(b)(2) drug that is not deemed therapeutically equivalent (TE) to its reference product by the FDA should be considered a “sole-source” drug.13 As a sole-source drug, it is entitled to its

own unique J-code.13

This seemingly bureaucratic change had explosive commercial implications. A unique J-code means the product has its own, distinct ASP. This uncouples its reimbursement from the price of the RLD and its generics, allowing the manufacturer to set a price that reflects the product’s unique, branded value proposition. It transformed the potential ROI for many 505(b)(2) projects overnight.

However, this created a profound new strategic dilemma for developers. The FDA does not automatically grant a TE rating to a 505(b)(2) product; the manufacturer must typically request it.13 This has bifurcated the 505(b)(2) commercialization strategy into two distinct paths:

- Path A: The “Branded Generic” Strategy (Seek Therapeutic Equivalence). A manufacturer can request and obtain a TE rating from the FDA. This would make their product automatically substitutable for the RLD at the pharmacy level. They would likely be bundled under the generic J-code. This is a volume-based strategy, competing for market share against other generics.

- Path B: The “Differentiated Brand” Strategy (Forgo Therapeutic Equivalence). A manufacturer can choose not to seek a TE rating. Their product would then be considered non-therapeutically equivalent, qualifying it for a unique J-code and its own ASP. This allows for premium, brand-like pricing. However, it is a value-based strategy. Without a TE rating, the product cannot be automatically substituted. The manufacturer must deploy a sales force and invest in marketing to convince physicians and payers of the product’s superior clinical benefits to justify its higher cost.

This J-code revolution means the decision of whether or not to seek a TE determination is now one of the most critical commercial decisions a 505(b)(2) developer will make. It must be made based on a deep understanding of the product’s clinical differentiation, the competitive landscape, and the priorities of payers and providers. The operational impact on healthcare providers has also been significant, creating new challenges in procurement, electronic health record management, and billing as they struggle to keep track of a growing number of unique 505(b)(2) products that are similar, but not interchangeable, with their reference drugs.15

The Future of Incremental Innovation: Emerging Trends and the Enduring Value of 505(b)(2)

The 505(b)(2) pathway is not a static regulatory curiosity; it is a dynamic and evolving reflection of the broader shifts in the pharmaceutical industry. As we look to the future, it is clear that its strategic importance will only continue to grow. Several key trends are shaping its trajectory and cementing its role as the primary engine of applied innovation in medicine.

The most dominant trend is the pathway’s sheer momentum. Having been little-used for the first two decades of its existence, the number of 505(b)(2) approvals began to surge in the early 2000s. In 2004, for the first time, the number of 505(b)(2) approvals surpassed the number of NME approvals, and it has not looked back since. With 505(b)(2)s consistently making up over half of all NDAs approved by CDER, and with some experts predicting they could eventually account for over 80% of new drug approvals, it is clear that this is now the mainstream path for non-NME development.8

This growth is fueled by its adoption across the industry spectrum. It is no longer just a tool for generic companies to create “branded generics.” Both large, innovator companies and smaller, specialty pharma players are aggressively using the pathway to manage product life cycles, enter new therapeutic areas, and build diversified portfolios.3 The focus of this activity is increasingly on high-value, complex therapeutic areas like central nervous system (CNS) disorders, oncology, and infectious diseases, where even small improvements can have a major impact on patient outcomes.8

Looking ahead, the flexibility of the 505(b)(2) framework makes it uniquely suited to incorporate emerging sources of data and evidence. The FDA has shown increasing openness to the use of Real-World Evidence (RWE)—data derived from electronic health records, claims data, and patient registries—in its regulatory decision-making. The 505(b)(2) pathway, with its inherent reliance on data from outside the applicant’s own controlled trials, provides a natural framework for integrating RWE to support an application, potentially further streamlining development for new indications or long-term safety assessments.

Ultimately, the enduring value of the 505(b)(2) pathway lies in its unique position as the nexus of science, regulation, and commerce. In a world where the low-hanging fruit of de novo discovery has largely been picked and the cost of reaching for the higher branches is becoming prohibitive, the most sustainable path to progress often lies in making better use of what we already have. The 505(b)(2) pathway provides the essential framework for this “applied innovation.” It is the process by which we take established scientific knowledge and translate it into tangible, real-world improvements: drugs that are safer, more effective, easier for patients to take, and available to treat a wider range of debilitating diseases.

For the forward-thinking pharmaceutical company, therefore, mastering the 505(b)(2) pathway is not an alternative strategy; it is the core strategy. It is the key to achieving sustainable growth, building a resilient and diversified portfolio, and, most importantly, delivering a continuous stream of meaningful advancements to the patients who depend on them.

Key Takeaways

- A Strategic Hybrid, Not a Shortcut: The 505(b)(2) pathway is a full New Drug Application (NDA) that strategically blends new, sponsor-conducted studies with reliance on existing data (e.g., the FDA’s findings for a Reference Listed Drug). It offers a middle ground between the high-cost, high-risk 505(b)(1) route for new molecules and the low-innovation 505(j) route for generics.

- Profound Economic Advantages: The primary benefit is a dramatic reduction in development time (often 3-5 years vs. 10-15) and cost (often $15-100M vs. >$1B). This saving comes from a reduced development program (fewer/smaller trials), not necessarily a shorter FDA review time.

- Innovation with Protection: The pathway is a vehicle for meaningful, incremental innovation, including new formulations, dosage forms, routes of administration, indications, and combinations. Crucially, these innovations can be protected by new patents and may qualify for valuable 3, 5, or 7-year periods of market exclusivity.

- The Bridge is Everything: The success of a 505(b)(2) application hinges on the “scientific bridge”—the new data (often pharmacokinetic studies) that justifies reliance on the reference drug’s data. Getting FDA buy-in on the bridging strategy at a pre-IND meeting is the most critical de-risking step of the entire program.

- Integrated IP and Regulatory Strategy is Non-Negotiable: There is an inherent tension between arguing a product is “similar enough” for the FDA and “different enough” for the Patent Office. These narratives must be consistent and managed by an integrated team from day one to avoid the risk of having patents invalidated for inequitable conduct.

- Market Access is the Final Hurdle: FDA approval is not enough. Payers will demand clear evidence of clinical and economic value over existing, cheaper alternatives.

- The J-Code Revolution Changes Everything: A 2022 CMS policy shift means 505(b)(2) drugs not deemed “therapeutically equivalent” can receive their own unique J-code and brand-like pricing. This has created a critical strategic choice: seek therapeutic equivalence and compete on volume, or forgo it and compete on differentiated value.

- Business Intelligence is Essential: Navigating the patent landscape, tracking competitors, and identifying opportunities requires specialized tools. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are critical for the due diligence and strategic planning necessary for success in the 505(b)(2) space.

Conclusion

The 505(b)(2) pathway has firmly established itself as a central pillar of modern drug development. It is far more than a regulatory workaround; it is a sophisticated strategic instrument that enables companies to navigate the immense economic pressures of the pharmaceutical industry while delivering tangible, patient-focused innovation. By providing a framework to build upon the vast foundation of existing scientific knowledge, it lowers the barriers to entry, reduces risk, and accelerates the delivery of improved medicines to the public. However, its advantages are not easily won. Success demands a holistic strategy that seamlessly integrates regulatory science, clinical development, CMC, intellectual property law, and market access planning from the earliest stages. For the companies that master this complex interplay, the 505(b)(2) pathway offers a powerful and sustainable model for creating value for their shareholders, for the healthcare system, and, most importantly, for patients.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can a 505(b)(2) application be submitted if the reference drug’s patents have not yet expired?

Yes, absolutely. A 505(b)(2) application can be submitted at any time, regardless of the patent status of the reference listed drug (RLD). However, the applicant must make a certification to the patents listed in the Orange Book for the RLD. If the applicant files a Paragraph IV certification, claiming that the patents are invalid or not infringed, it will likely trigger a patent infringement lawsuit from the patent holder and a 30-month stay of FDA approval. The 5-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity is different; it creates a bar on even submitting a 505(b)(2) that references the NCE until four years after the NCE’s approval (known as a Paragraph IV carve-out).

2. Is it possible for a 505(b)(2) product to be considered a “new molecular entity” and receive 5-year exclusivity?

Yes, though it is less common than receiving 3-year exclusivity. A 505(b)(2) product can qualify for 5-year NCE exclusivity if its active moiety has never been previously approved by the FDA.3 This typically occurs when the new drug is a new salt, ester, or other non-covalent derivative of a previously unapproved active ingredient. For example, if Drug X is an approved active ingredient, a new salt form like “Drug X hydrochloride” would not be an NCE. But if a company develops a new ester prodrug where the active therapeutic portion has never been approved on its own, it could potentially qualify as an NCE, granting it the highly valuable 5-year exclusivity period.

3. What is the difference between relying on the “FDA’s finding of safety and effectiveness” versus relying on “published literature”?

Both are permissible sources of data for a 505(b)(2) application, but they have different implications. Relying on the “FDA’s finding of safety and effectiveness” means the applicant is referencing a specific approved drug (the RLD) listed in the Orange Book. This is the most common approach and requires the applicant to make patent certifications for the RLD. Relying on “published literature” means the application is supported by data from scientific journal articles or other public sources. This approach might be used if there is no single, ideal RLD, or for very old drugs approved before modern standards (“pre-DESI” drugs). An application can rely on one or both sources. Relying solely on literature may avoid the need for patent certifications if no specific RLD is formally referenced.

4. Can biologics, like monoclonal antibodies, be approved through the 505(b)(2) pathway?

No. The 505(b)(2) pathway is exclusively for drugs regulated by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) under the FD&C Act. Biologics are regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) under the Public Health Service Act.34 The analogous pathway for “follow-on” biologics is the 351(k) pathway for biosimilars. However, a drug-biologic

combination product, where the primary mode of action is determined to be the drug component, can be reviewed by CDER and may utilize the 505(b)(2) pathway to leverage data on the approved drug component.16

5. My company has developed a new formulation that we believe is superior. Is it better to seek therapeutic equivalence (TE) to capture generic volume or to avoid it to get a unique J-code and higher price?

This is the central commercial dilemma for 505(b)(2) developers today, and there is no single right answer. The decision depends on a careful analysis of several factors:

- Degree of Differentiation: How significant and demonstrable is the clinical benefit of your new formulation? If the improvement is marginal, payers will likely refuse to cover a higher price, making the volume-based TE strategy more viable. If the benefit is substantial (e.g., a major reduction in a serious toxicity), the higher-priced, unique J-code strategy is more attractive.

- Competitive Landscape: Is the market for the RLD already heavily genericized with multiple players? If so, competing on price might be very difficult, pushing you toward the differentiated brand strategy.

- Payer and Provider Dynamics: Will payers in this therapeutic area accept a higher price for an incremental improvement? Are providers willing to go through the extra steps of ordering a specific non-substitutable product?

- Corporate Capabilities: Does your company have the sales force and marketing infrastructure to support a branded launch, or is it better suited to a “branded generic” model?

Ultimately, the choice requires a sophisticated market access assessment and a clear-eyed view of the product’s true value proposition.32

References

- The 505(b)(2) Drug Patent Approval Process: Uses and Potential Advantages, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-505b2-drug-patent-approval-process-uses-and-potential-advantages/

- Old Drugs, New Tricks: Repurposing Through 505(b)(2) Submissions | Sterne Kessler, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/old-drugs-new-tricks-repurposing-through-505b2-submissions/

- The 505(b)(2) Drug Approval Pathway: A Potential Solution for the Distressed Generic Pharma Industry in an Increasingly Diluted ANDA Marketplace? | Sterne Kessler, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/505b2-drug-approval-pathway-potential-solution-distressed-generic-pharma/

- FDA’s 505(b)(2) Explained: A Guide to New Drug Applications, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/505b2

- www.pharmacytimes.com, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/understanding-recent-changes-to-505-b-2-drugs-and-reimbursement#:~:text=In%20the%20original%20Hatch%2DWaxman,together%2C%20and%20make%20combination%20products.

- Abbreviated Approval Pathways for Drug Product: 505(b)(2) or … – FDA, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/abbreviated-approval-pathways-drug-product-505b2-or-anda

- overview of the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway for new drug applications – FDA, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/156350/download

- 505(b)(2): A Pathway to Competitiveness Through Innovation for …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.pharmexec.com/view/505b2-pathway-competitiveness-through-innovation-specialty-and-generic-companies

- Review of Drugs Approved via the 505(b)(2) Pathway: Uncovering Drug Development Trends and Regulatory Requirements – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/review-of-drugs-approved-via-the-505b2-pathway-uncovering-drug-development-trends-and-regulatory-requirements-2/

- Understand the difference between 505(j), 505(b)(1) and 505(b)(2) – Veeprho, accessed July 28, 2025, https://veeprho.com/understanding-difference-between-505j-505b1-and-505b2/

- Understanding 505(b)(2) Drug Development & API Supply Issues – LGM Pharma, accessed July 28, 2025, https://lgmpharma.com/blog/understanding-505b2-drug-development-api-supply-issues/

- Part 1: 505(b)(2) NDA – Navigating the Regulatory Pathway – MMS …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://mmsholdings.com/perspectives/part-1-505b2-nda-navigating-the-regulatory-pathway/

- Understanding Recent Changes to 505(b)(2) Drugs and …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/understanding-recent-changes-to-505-b-2-drugs-and-reimbursement

- 505(b)(2) Drugs | Buy And Bill – BuyandBill.com, accessed July 28, 2025, https://buyandbill.com/505b2-drugs/

- 505(b)(2) Drugs: Creating New Chaos for Infusion Centers, accessed July 28, 2025, https://ahdbonline.com/online-first-articles/505-b-2-drugs-creating-new-chaos-for-infusion-centers

- Using the 505(b)(2) Pathway to Streamline Regulatory Approval for Combination Products, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/505b2-pathway-regulatory-combination-products/

- 505(b)(2) Pathway | CRO Services | Consulting – Premier Research, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premier-research.com/expertise/505b2-development-pathway/

- Navigating the 505(b)(2) Pathway: No Two … – Premier Research, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/navigating-the-505b2-pathway-no-two-drugs-are-alike/

- NCE Potential with 505(b)(2) Program – BioPharma Services, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.biopharmaservices.com/blog/leveraging-the-505b2-program-to-prolong-the-life-of-a-new-chemical-entity-nce/

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- The Rise of 505(b)(2) Filings: Benefits and Opportunities for Pharma …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.aizant.com/knowledge-hub/blog/the-rise-of-505b2-filings-benefits-and-opportunities-for-pharma-companies/

- Why Generic Drug Makers May Benefit from 505(b)(2) Approval – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/why-generic-drug-makers-may-benefit-from-505b2-approval/

- Benefits of The 505(b)(2) Pathway For Prodrugs | Allucent, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/benefits-utilizing-505b2-pathway-prodrugs

- 505(b)(2) Approval Times: The Real Scoop | Premier Consulting, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/505b2-approval-times-the-real-scoop/

- 505(b)(2) for A New Drug Application? – BioPharma Services, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.biopharmaservices.com/blog/phase-1-when-is-505b2-a-good-choice-for-your-new-drug-application/

- www.fda.gov, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/small-business-assistance-frequently-asked-questions-new-drug-product-exclusivity#:~:text=No%20505(b)(2,of%20patent%20invalidity%20or%20noninfringement.

- Review on 505(b)(2) Drug Products Approved by USFDA from 2010 …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37040834/

- Exploring New Potential Through 505(b)(2) – Drug Development and Delivery, accessed July 28, 2025, https://drug-dev.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Exploring-New-Potential-Through-505-1.pdf

- Unveiling the 505(b)(2) Pathway: Navigating Pharmaceutical Innovation – Novumgen, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.novumgen.com/unveiling-the-505-b-2-pathway-navigating-pharmaceutical-innovation.html

- Faster Approval Of Combination Drug Products Via The 505(b)(2) Pathway, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/faster-approval-combination-drug-products-via-505b2-pathway/

- Using The 505(B)(2) Pathway To Streamline Approval Of Combination Products, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/using-the-b-pathway-to-streamline-approval-of-combination-products-0001

- Market Access for 505(b)(2) Drugs: Interview with US Payers Reveals a Better Approach, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/market-access-for-505b2-drugs-interview-with-us-payers-reveals-a-better-approach/

- Addressing 505(B)(2) Product Development Challenges Before …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.cellandgene.com/doc/addressing-b-product-development-challenges-before-they-become-problems-0001

- Leveraging 505(b)(2) to Innovate Beyond Existing Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/leveraging-505b2-to-innovate-beyond-existing-drug-patents/

- Inequitable Conduct Defense During Patent Litigation in a 505(b)(2) NDA Context, accessed July 28, 2025, https://ipfdalaw.com/inequitable-conduct-defense-during-patent-litigationin-a-505b2-nda-context/

- DrugPatentWatch Pricing, Features, and Reviews (Jul 2025) – Software Suggest, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.softwaresuggest.com/drugpatentwatch

- Find Your Next Blockbuster – Biotech & Pharmaceutical patents …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/about.php

- DrugPatentWatch: 505(b)(2) Applications and Patent Extensions Offer Strategies for Post-ANDA Market Exclusivity. – GeneOnline, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/drugpatentwatch-505b2-applications-and-patent-extensions-offer-strategies-for-post-anda-market-exclusivity/

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed July 28, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- 505(b)(2) Drugs: New Chaos for Infusion Centers, accessed July 28, 2025, https://jhoponline.com/web-exclusives/505-b-2-drugs

- 505(b)(2) Changes That Generic Manufacturers Should Know | Avalere Health Advisory, accessed July 28, 2025, https://advisory.avalerehealth.com/insights/505b2-changes-that-generic-manufacturers-should-know

- The 505(b)(2) Drug Approval Pathway – JONATHAN J. DARROW …, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fdli.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Darrow.pdf

- Generic Company CEOs: 505(b)(2) – Contract Pharma, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.contractpharma.com/generic-company-ceos-505b2/

- Analysis of Review Times for Recent 505(b)(2) Applications – ResearchGate, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316168331_Analysis_of_Review_Times_for_Recent_505b2_Applications

- The 505(b)(2) NDA Leveraging Other People’s Data – Applied Clinical Trials, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/505b2-nda-leveraging-other-peoples-data

- Back To Basics: 505(b)(2) FAQs Part 1 | Premier Consulting, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/back-basics-505b2-faqs-part-1/

- Exploring 505b2 Value-Added Medicines: A Complete Overview – Adragos Pharma, accessed July 28, 2025, https://adragos-pharma.com/exploring-505b2-value-added-medicines-a-complete-overview/

- www.pharmagrowthhub.com, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.pharmagrowthhub.com/post/understanding-the-differences-between-505-j-505-b-1-and-505-b-2-drug-approval-pathways#:~:text=While%20505(j)%20is%20ideal,cost%20and%20time%20to%20market.

- 505(b)(2) Development Articles And Insights | Premier Consulting, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/505b2-development/

- FDA Amends Regulations for 505(b)(2) Applications and ANDAs—Part II – Finnegan, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/articles/fda-amends-regulations-for-505b2-applications-and-andaspart-ii.html

- Abbreviated New Drug Applications and 505(b)(2) Applications (Final Rule) Regulatory Impact Analysis – FDA, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/about%20fda/published/Abbreviated-New-Drug-Applications-and-505(b)(2)-Applications-(Final-Rule)-Regulatory-Impact-Analysis.pdf

- US FDA 505(b)(2) NDA clinical, CMC and regulatory strategy concepts to expedite drug development – PubMed, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37196760/

- US FDA 505(b)(2) NDA clinical, CMC and regulatory strategy concepts to expedite drug development – ResearchGate, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/370862814_US_FDA_505b2_NDA_clinical_CMC_and_regulatory_strategy_concepts_to_expedite_drug_development

- Review of Drugs Approved via the 505(b)(2) Pathway: Uncovering Drug Development Trends and Regulatory Requirements – PubMed, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008242/

- DrugPatentWatch 2025 Company Profile: Valuation, Funding & Investors | PitchBook, accessed July 28, 2025, https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/519079-87

- DrugPatentWatch – 2025 Company Profile & Competitors – Tracxn, accessed July 28, 2025, https://tracxn.com/d/companies/drugpatentwatch/__J3fvnNbRBdONp_-p-gLex5dxrrF6shPqUenXhHlGHHM

- What Is 505(b)(2)? | Premier Consulting, accessed July 28, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/what-is-505b2/

- Applications Covered by Section 505(b)(2) December 1999 – FDA, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/applications-covered-section-505b2

- List of 505(b)(2) products approved under each category* | Download Table – ResearchGate, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/List-of-505b2-products-approved-under-each-category_tbl1_264835794

- (PDF) Is 505(b)(2) filing a safer strategy: Avoiding a known risk?, accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264835794_Is_505b2_filing_a_safer_strategy_Avoiding_a_known_risk

- Practices Face Challenges When Manufacturers Turn to Code 505(b)(2), accessed July 28, 2025, https://www.targetedonc.com/view/practices-face-challenges-when-manufacturers-turn-to-code-505-b-2-