Introduction: Two Classes of Drugs, Two Worlds of Protection

In biopharmaceutical innovation not all molecules are created equal. On one side, we have the elegant simplicity of small-molecule drugs—the chemically synthesized workhorses like aspirin or Lipitor that have formed the bedrock of modern medicine. On the other, we have the breathtaking complexity of biologics—vast, intricate proteins like Humira or Keytruda, coaxed from living cells to wage war on disease with unparalleled precision. These two classes of drugs are not merely different in scale; they represent two fundamentally distinct scientific paradigms. And from this scientific chasm, two divergent, high-stakes worlds of intellectual property and market protection have emerged.

Understanding this great divide is not an academic exercise. For the IP attorneys, R&D leaders, and business development executives reading this report, it is the critical strategic variable that dictates the flow of billions of dollars in investment, shapes the landscape of litigation risk, and ultimately determines the commercial longevity of your most valuable assets. The path a small molecule travels from patent filing to facing a generic “price cliff” is a well-trodden road, governed by a four-decade-old legislative pact. The journey of a biologic, however, is a newer, more treacherous expedition through a bespoke labyrinth of regulations, culminating not in a cliff, but in a prolonged war of attrition against “biosimilar” competitors.

At the heart of these two worlds lies a core conflict, a delicate and often contentious balancing act that defines modern healthcare policy. On one hand, there is the undeniable need to incentivize the monumental, high-risk investment required to bring a new therapy to market. This is the argument for robust, long-lasting periods of exclusivity, the temporary monopoly that allows innovators to recoup costs that can run into the billions.1 On the other hand, there is the powerful societal and political imperative to control spiraling healthcare costs and broaden patient access to life-saving medicines. This is the argument for competition, for the streamlined entry of lower-cost generics and biosimilars that can save healthcare systems hundreds of billions of dollars annually.3

The legislative frameworks that have evolved to manage this tension—the Hatch-Waxman Act for small molecules and the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) in the United States, and the unified regulatory system in Europe—are the direct result of this push and pull. They are not just sets of rules; they are the codified philosophies of how to reward innovation while eventually democratizing access.

This report is your strategic roadmap through this complex terrain. We will begin at the molecular level, establishing the scientific bedrock upon which all subsequent legal and commercial distinctions are built. From there, we will embark on a deep dive into the parallel regulatory universes of the United States, dissecting the machinery of Hatch-Waxman and the BPCIA. We will then cross the Atlantic to analyze the European Union’s harmonized approach, before putting these systems head-to-head to reveal the critical differences that drive global strategy. Finally, we will enter the commercial battlefield, using hard data and real-world case studies to contrast the market impact of generics and biosimilars. Our journey will culminate in an actionable playbook designed to help you turn this intelligence into a tangible competitive advantage. Welcome to the great divide.

The Molecular Blueprint: Why Biologics and Small Molecules Are Fundamentally Different

Before we can possibly decipher the intricate legal codes that govern pharmaceutical exclusivity, we must first appreciate the profound scientific realities that necessitated their creation. The distinction between a small molecule and a biologic is not a minor regulatory classification; it is a fundamental difference in identity that echoes through every stage of a drug’s life, from its creation and manufacturing to its administration and its very definition in the eyes of the law. For anyone making strategic decisions in this space, understanding these differences is non-negotiable. They are the first principles from which all else follows.

The Architect’s Sketch vs. The Living Organism: A Deep Dive into Size, Complexity, and Structure

The most immediate and striking difference between these two therapeutic modalities is one of sheer scale. Imagine comparing a simple bicycle to a sprawling, self-sustaining ecosystem. That is the level of difference in complexity we are discussing.

Small-molecule drugs are the bicycles. They are, as their name implies, small. Typically possessing a molecular weight under 900 Daltons, they are composed of a relatively small number of atoms—often just 20 to 100.6 Think of aspirin, with its mere 21 atoms.7 Their chemical structure is well-defined, stable, and can be precisely characterized and reproduced. They are, in essence, an architect’s sketch brought to life through chemistry—a known quantity that can be replicated with perfect fidelity.10

Biologics, in contrast, are the living ecosystems. They are therapeutic giants, often 200 to 1,000 times larger than their small-molecule counterparts.1 A biologic like a monoclonal antibody can be composed of over 25,000 atoms and possess an incredibly complex, three-dimensional structure that is absolutely integral to its function.7 These are not simple chemical keys; they are intricate biological machines. This complexity means they can never be fully characterized down to the last atom. There is an inherent micro-heterogeneity, a natural variability from one batch to the next, much like how no two bottles of wine from the same vineyard are ever truly identical.7 This distinction is the conceptual lynchpin for the entire regulatory framework. It is why a follow-on small molecule can be a “generic”—an

identical copy—while a follow-on biologic can only ever be a “biosimilar”—a highly similar but not identical version.7

Chemical Synthesis vs. Biomanufacturing: The Profound Impact on Regulation and Replication

The differences in size and complexity lead directly to vastly different methods of creation, which in turn have profound regulatory consequences. The mantra for biologics is “the process is the product,” a concept that has no real equivalent in the world of small molecules.

Small molecules are products of pure chemistry. They are manufactured through a series of predictable, controllable, and repeatable chemical synthesis steps in a laboratory.6 Once the recipe is known, any competent manufacturer can follow it to produce a final active ingredient that is chemically identical to the original. This is what makes the generic drug industry possible. The regulatory focus for a generic is simply to prove that its identical active ingredient behaves the same way in the human body—a concept known as bioequivalence.7

Biologics are products of biology. They are not synthesized; they are coaxed into existence. They are manufactured or extracted from living systems—genetically engineered bacteria, yeast, or mammalian cell cultures—in a highly sensitive and complex process known as biomanufacturing.6 This process can take weeks and requires constant, meticulous monitoring.7 Because the living cells are the factory, the final product is inextricably linked to the precise conditions of its creation. Even minute, undetectable changes to the manufacturing process—a slight shift in the temperature of a bioreactor or a change in the cell culture media—can alter the final protein’s structure, potentially impacting its safety or efficacy.10

This “product-by-process” reality is why regulators like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) place such an intense focus on the manufacturing controls for biologics.10 It is also why a biosimilar manufacturer cannot simply copy a recipe. They must reverse-engineer the product and then develop their own unique, proprietary manufacturing process to produce a molecule that is demonstrably “highly similar” to the original. This requires an exhaustive head-to-head “comparability exercise,” a battery of analytical and functional tests to prove that despite being made through a different process, the end product has no clinically meaningful differences from the innovator’s drug.16

Pill vs. Infusion: How Administration, Stability, and Delivery Shape Commercial Strategy

The physical characteristics of these molecules also dictate how they are delivered to patients, a factor with enormous consequences for patient convenience, the cost of care, and overall commercial strategy.

Small molecules are generally robust and stable. Most can withstand room temperature for long periods, often lasting for years with basic storage conditions.1 This stability, combined with their small size, allows them to be formulated into convenient oral dosage forms like tablets and capsules. Once ingested, they are easily absorbed through the digestive system into the bloodstream and can readily pass into cells to interact with their targets.6 This ease of administration is a massive commercial advantage.

Biologics are far more delicate. Their complex, folded structures are fragile and highly sensitive to their environment. They typically demand precise temperature control, requiring refrigeration or even deep freezing to maintain their integrity.1 Their large size and protein-based nature mean they cannot survive the harsh environment of the digestive system; they would simply be broken down and digested like any other protein. Consequently, biologics must be administered via injection or intravenous (IV) infusion, bypassing the digestive tract entirely.1 This requirement often means a trip to a clinic or hospital for an infusion, or at-home injections that can be daunting for patients, adding layers of cost and complexity to the treatment regimen.

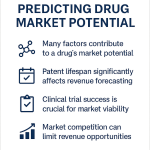

The Economic Equation: Deconstructing the Data on Development Costs, Timelines, and Success Rates

For decades, the conventional wisdom underpinning the entire regulatory and exclusivity framework has been that biologics are a fundamentally different beast from an economic perspective. The long-held justification for granting biologics longer periods of market monopoly is that they are significantly more expensive, more time-consuming, and riskier to develop than small molecules.1 Industry estimates frequently cite development costs of $2-4 billion over 10-12 years for a new biologic, compared to $1-2 billion over 8-10 years for a small molecule.1 This narrative has been incredibly effective in shaping legislation, most notably the 12-year exclusivity period granted under the BPCIA in the U.S.

However, a critical and data-driven counter-narrative is emerging, one that directly challenges this long-standing orthodoxy and has profound implications for the future of pharmaceutical policy and strategy. A recent, comprehensive analysis of all new therapeutic agents approved by the FDA between 2009 and 2023 paints a startlingly different picture.

“Median development times were 12.6 years (IQR, 10.6-15.3 years) for biologics vs 12.7 years (IQR, 10.2-15.5 years) for small-molecule drugs (P =.76). Biologics had higher clinical trial success rates at every phase of development. Median development costs were estimated to be $3.0 billion (IQR, $1.3 billion-$5.5 billion) for biologics and $2.1 billion (IQR, $1.3 billion-$3.7 billion) for small-molecule drugs (P =.39).” 22

Let’s unpack the seismic implications of these findings. The argument that biologics require a longer development runway is effectively neutralized; the data show their median development times are statistically identical to those of small molecules.22 The argument that they are vastly more expensive is also weakened. While the median cost for biologics is higher, the ranges are enormous and overlap significantly, and the difference is

not statistically significant.22 This suggests that while some biologics are incredibly expensive to develop, it is not a systematically proven rule when compared to the cost of developing complex small molecules.

Perhaps most stunningly, the data completely upends the argument that biologics are a riskier investment. The analysis found that biologics actually have higher clinical trial success rates at every single phase of development.22 This means that once a biologic candidate is identified, it is statistically more likely to make it to market than a small-molecule candidate.

The foundational economic arguments that have been used for over a decade to justify the vast difference in U.S. exclusivity periods—12 years for biologics versus 5 for small molecules—are being systematically dismantled by robust, empirical data. If the development time is the same, the cost is not statistically different, and the risk of failure is actually lower, the rationale for granting biologics an extra seven years of government-sanctioned market monopoly begins to look exceedingly thin. This suggests the current legal framework may be, as the study’s authors conclude, “over-rewarding” the development of biologics relative to small molecules, a powerful and disruptive conclusion that will undoubtedly fuel policy debates for years to come.22

The U.S. Framework Part I: Hatch-Waxman and the Dawn of the Generic Drug Market

To understand the intricate world of pharmaceutical exclusivity in the United States, one must begin in 1984. The passage of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, known universally as the Hatch-Waxman Act, was a watershed moment. It didn’t just tweak a few regulations; it fundamentally re-engineered the economic landscape of the small-molecule drug industry. It was a masterfully crafted piece of legislation that created the modern generic drug market out of whole cloth, establishing a legal and commercial playbook that has dictated strategy for both innovator and generic firms for four decades.

The Grand Bargain of 1984: The Dual Aims of the Hatch-Waxman Act

Before 1984, the path to market for a generic drug was a minefield. Generic manufacturers were often required to conduct their own expensive and duplicative clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness, even for drugs whose patents had long expired.24 The system was inefficient and stifled competition, keeping drug prices high.

The Hatch-Waxman Act, named for its sponsors Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, was designed as a “grand bargain” to solve this problem by balancing two competing interests: fostering price-lowering competition from generics while preserving the financial incentives for innovator companies to continue pouring billions into risky R&D.3

For the generic industry, the bargain offered a streamlined, expedited approval pathway that would dramatically lower the barrier to market entry. For the innovator industry, it offered a mechanism to restore some of the patent life lost during the lengthy FDA approval process and, for the first time, created periods of FDA-administered regulatory exclusivity that operated independently of patents. This dual-pronged approach was designed to be a win-win: cheaper drugs for consumers and continued innovation from pharmaceutical pioneers. In large part, it succeeded. When the Act was passed in 1984, generics accounted for only 19% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. Today, that number is over 90%.24

The ANDA Pathway: How the Abbreviated New Drug Application Revolutionized Competition

The engine of the Hatch-Waxman revolution is the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. This pathway, codified under section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act, was the key that unlocked the generic market.24

The core principle of the ANDA is brilliantly simple: a generic applicant does not need to repeat the innovator’s costly and time-consuming clinical trials. Instead, it can rely on the FDA’s previous finding that the innovator’s drug is safe and effective.24 The generic firm’s primary burden is to demonstrate that its product is “bioequivalent” to the innovator’s drug, meaning it contains the same active ingredient, in the same dosage form and strength, and is absorbed into the body at the same rate and to the same extent.3 By eliminating the need for de novo clinical trials, the ANDA process slashed the cost and time required to bring a generic to market from hundreds of millions of dollars and many years to just a few million dollars and a couple of years.28

Just as importantly, the Act created a statutory “safe harbor.” This provision shields generic companies from patent infringement lawsuits for activities reasonably related to preparing their FDA submission.3 This crucial protection means a generic company can begin its development work and bioequivalence studies long before the innovator’s patents expire, ensuring it is ready to launch the moment that protection ends.

Decoding the Orange Book: The Role of Patent Listings and the Pivotal Paragraph IV Challenge

If the ANDA is the engine of Hatch-Waxman, the “Orange Book” is its navigation system. Officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, this FDA publication is the central, public repository of all approved small-molecule drugs and, critically, the patents that innovator companies claim cover their products.3

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must consult the Orange Book and make a certification for each patent listed for the innovator drug it seeks to copy. There are four possible certifications, but one stands above all others in strategic importance: the Paragraph IV certification.3

- Paragraph I: No patent information has been filed.

- Paragraph II: The patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III: The generic will wait to launch until the patent expires.

- Paragraph IV: The patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.

A Paragraph IV certification is a direct challenge to the innovator’s intellectual property. It is an audacious claim that the generic company has the right to enter the market before the listed patent expires. Under the law, filing a Paragraph IV certification is considered an “artificial” act of patent infringement, giving the innovator an immediate basis to sue the generic applicant.3

This mechanism is the primary legal pathway for challenging the validity of drug patents. When an innovator receives notice of a Paragraph IV filing, it has 45 days to file a lawsuit. If it does, the FDA is automatically barred from approving the generic’s ANDA for a period of up to 30 months.3 This “30-month stay” provides a critical window for the parties to litigate the patent dispute in federal court before the generic product can launch and potentially cause irreparable financial harm to the innovator.

The Arsenal of Exclusivity for Small Molecules

Beyond patent protection, Hatch-Waxman created a new system of regulatory exclusivities—periods during which the FDA is prohibited from approving a competing generic application, regardless of the patent status. These exclusivities are the innovator’s reward in the grand bargain.

- Five-Year New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: This is the most significant exclusivity for a truly novel drug. Any drug containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA is granted five years of data exclusivity. During this period, the FDA cannot even accept an ANDA submission for the first four years (unless it contains a Paragraph IV challenge).3 This provides a guaranteed five-year monopoly from the date of approval.

- Three-Year New Clinical Study Exclusivity: This exclusivity is granted for new applications or supplemental applications that required new clinical studies for approval. This could be for a new indication, a new dosage form, or a switch from prescription to over-the-counter status. This three-year period protects only the specific change or use supported by the new data, not the entire drug.3

- 180-Day Generic Exclusivity: To incentivize the risky and expensive process of challenging patents, Hatch-Waxman offers a powerful prize. The very first generic company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is rewarded with 180 days of marketing exclusivity.3 During this six-month period, the FDA cannot approve any other generic versions of the same drug. This head start can be immensely profitable and is the primary driver for generic companies to engage in patent litigation.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: To encourage drug testing in children, an additional six months of exclusivity can be tacked on to any existing patent or regulatory exclusivities if the company conducts requested pediatric studies.3

This intricate system of abbreviated applications, public patent listings, litigation triggers, and layered exclusivities created a predictable, albeit contentious, framework that has successfully balanced competition and innovation in the small-molecule space for a generation. But as science evolved, it became clear that this framework was utterly unsuited for the new world of biologics.

The U.S. Framework Part II: The BPCIA and the Bespoke World of Biologics

As the 21st century dawned, the pharmaceutical landscape was undergoing a seismic shift. The rise of biotechnology meant that a growing number of blockbuster therapies were not simple chemicals from a lab, but massive, complex proteins from living cells. The Hatch-Waxman framework, built for a world of identical chemical copies, was fundamentally incompatible with the scientific reality of biologics. There was no pathway for a “generic” biologic because a true generic was impossible to make. This regulatory vacuum created de facto permanent monopolies for innovator biologics, and by the late 2000s, the pressure to create a competitive pathway became immense. The result was the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act in 2010.4 It was an attempt to create a parallel universe for biologics, inspired by Hatch-Waxman but bespoke to the unique challenges of biotechnology.

A Pathway of Its Own: Why Biologics Needed a Different Approach

The BPCIA’s very existence is a testament to the scientific principles we discussed earlier. Because biologics are large, complex, and manufactured in living systems, it is impossible to prove that a follow-on version is identical to the original.14 The concept of “bioequivalence,” the cornerstone of the ANDA pathway, simply did not apply.

Therefore, Congress had to invent a new standard: “biosimilarity.” The BPCIA created an abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products, but it was, by necessity, far more rigorous and data-intensive than the ANDA pathway for small molecules. The goal was the same as Hatch-Waxman’s—to foster competition and lower prices—but the scientific hurdles were orders of magnitude higher, requiring a completely new regulatory architecture.16

Biosimilar vs. Interchangeable: Deconstructing the Two-Tier System

A key feature of the BPCIA, and a significant point of departure from regulatory systems elsewhere in the world, is its creation of a two-tier system for follow-on biologics.

The first tier is the “biosimilar.” To be approved as a biosimilar, a manufacturer must demonstrate through an extensive data package that its product is “highly similar” to an already-approved innovator biologic (the “reference product”). Crucially, they must also show that there are “no clinically meaningful differences” between their product and the reference product in terms of safety, purity, and potency.14 This is not a simple lab test; it is a comprehensive “comparability exercise” that involves a mountain of analytical data, animal studies, and often, at least one human clinical trial to confirm that the product behaves the same way in patients.16

The second, higher tier is the “interchangeable biosimilar.” To earn this designation, a product must first meet the rigorous standard for biosimilarity. Then, it must clear an additional hurdle: it must be “expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient”.37 For products administered more than once, the manufacturer must also demonstrate that switching back and forth between the reference product and the interchangeable product poses no greater risk than using the reference product alone.37 This often requires dedicated “switching studies,” which add significant time and cost to development.39

The prize for clearing this higher bar is significant. An interchangeable product can be automatically substituted for the reference product at the pharmacy level, much like a generic drug, without the intervention of the prescribing physician (subject to individual state laws).7 This is a powerful commercial advantage, as it dramatically accelerates market uptake. However, the high bar for achieving this status means that, even more than a decade after the BPCIA’s passage, very few biosimilars have been approved with the interchangeable designation.4

The 12-Year Fortress: Analyzing the Landmark Reference Product Exclusivity

If the BPCIA has one single, defining feature, it is the remarkable period of market exclusivity it grants to innovator biologics. This is the heart of the “grand bargain” for the biotech industry and the most contentious part of the law.

An innovator biologic receives a total of 12 years of market exclusivity from the date of its first licensure by the FDA.16 This is a formidable fortress of protection, more than double the 5-year NCE exclusivity for small molecules.

This 12-year period is actually broken into two parts:

- 4-Year Data Exclusivity: For the first four years after the innovator biologic is licensed, the FDA cannot even accept a biosimilar application for review.34

- 12-Year Market Exclusivity: The full 12 years must elapse before the FDA can grant final approval to a biosimilar application.16

This lengthy, guaranteed monopoly was the result of intense lobbying and was justified by the industry and legislators on the grounds of the supposedly higher costs, longer timelines, and greater risks of biologic development—the very assumptions that, as we have seen, are now being challenged by hard data.

The “Patent Dance”: A Labyrinth of Private Information Exchange

Perhaps the most complex and strategically bewildering aspect of the BPCIA is its unique mechanism for handling patent disputes. Where Hatch-Waxman created the transparent, public forum of the Orange Book, the BPCIA established an intricate, multi-step process of private information exchange between the innovator and the biosimilar applicant, known colloquially as the “patent dance”.31

The dance is intended to identify and narrow down the patents that will be litigated before the biosimilar launches. In theory, it works like this:

- Within 20 days of the FDA accepting its application, the biosimilar applicant can provide a copy of its application and manufacturing information to the innovator.

- The innovator then has 60 days to provide a list of all patents it believes could reasonably be asserted.

- The biosimilar applicant responds with its own list and provides its arguments for why the innovator’s patents are invalid or not infringed.

- The innovator then responds to those arguments.

- The parties then negotiate in good faith to agree on a final list of patents to be litigated in an initial wave of lawsuits.

This convoluted process was intended to bring order to potentially massive and complex patent disputes. However, a landmark Supreme Court decision (Sandoz v. Amgen) ruled that a biosimilar applicant is not actually required by law to engage in the patent dance. It can opt out, choosing instead to wait and provide a 180-day notice of commercial marketing before it launches, at which point the innovator can sue.34 This has turned the dance from a mandatory procedure into a complex strategic choice, adding yet another layer of uncertainty for both sides.

Head-to-Head: A Strategic Comparison of Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA Litigation

The differences between the two U.S. frameworks are not just academic; they create two fundamentally different strategic battlefields for patent litigation.

- Transparency (Public vs. Private): Hatch-Waxman operates in the open. The Orange Book provides a clear, public, and finite list of patents that a generic company must address.31 This creates a defined playing field. The BPCIA, by contrast, operates in the shadows. The “patent dance” is a private exchange, and a biosimilar applicant often has no certainty about which of an innovator’s potentially hundreds of patents will be asserted against it until the process begins.31

- Litigation Trigger (Certain vs. Uncertain): Under Hatch-Waxman, the Paragraph IV certification is a clear, unambiguous trigger for litigation.3 Under the BPCIA, the triggers are more complex and strategically variable, depending on whether the parties engage in the dance or rely on the notice of commercial marketing.

- FDA Stay (Automatic vs. None): This is perhaps the most critical difference. A Hatch-Waxman lawsuit automatically triggers a 30-month stay of FDA approval, giving the innovator a powerful tool to delay generic entry and providing time for the courts to resolve the dispute.30 The BPCIA has

no automatic stay.31 A biosimilar can theoretically be approved by the FDA and launch “at risk” while patent litigation is still ongoing, a high-stakes gamble for the biosimilar company. - Scope of Patents (Narrow vs. Broad): Hatch-Waxman litigation is confined to the patents listed in the Orange Book, which explicitly excludes patents covering manufacturing processes.31 BPCIA litigation, however, heavily features manufacturing process patents. Given that a biologic is defined by its process, this opens up a vast and fertile new territory for innovators to build their patent defenses.42

These structural differences have a profound consequence. The BPCIA’s design—with its lack of a transparent patent list, its inclusion of a vast array of manufacturing patents, and its complex, optional litigation dance—creates an environment that is perfectly suited for the deployment of a “patent thicket” defense strategy. An innovator biologic company is incentivized to file dozens, or even hundreds, of patents covering every conceivable tweak to its manufacturing process, formulation, and delivery device. When a biosimilar challenger appears, the innovator can threaten litigation on a massive number of these patents, creating a legal and financial minefield. Faced with the prospect of a multi-front war with staggering costs and immense uncertainty, the biosimilar company is far more likely to settle for a delayed market entry date than to fight its way through the entire thicket. The very design of the BPCIA, intended to mirror Hatch-Waxman’s success, has instead created a system where overwhelming litigation risk has become one of the most formidable barriers to competition.

The European Approach: Harmonization and the “8+2+1” Rule

As we shift our focus across the Atlantic, we enter a regulatory landscape built on a different philosophy. While the U.S. created two distinct, parallel legal frameworks for small molecules and biologics, the European Union, through the European Medicines Agency (EMA), has opted for a more unified and harmonized approach. The EU’s system applies a single, predictable set of rules for data and market protection to all new medicines, regardless of their molecular size or origin. This approach, while still complex, offers a fascinating contrast to the bifurcated American system and has made Europe a crucial battleground and learning lab for the global biosimilar market.

The EMA’s Unified Framework: One Rule for Two Drug Classes

The most striking feature of the European system is the absence of separate, sweeping legislative acts for small molecules and biologics akin to Hatch-Waxman and the BPCIA. Instead, the EMA operates under a unified framework established by EU directives and regulations, applying the same core principles of exclusivity to both classes of drugs.33

This is not to say the EMA treats them identically in all respects. As we will see, the scientific and data requirements for approving a generic small molecule versus a biosimilar are vastly different, reflecting the underlying molecular realities. However, the overarching commercial protections—the periods of data and market exclusivity that dictate when a competitor can enter the market—are the same for both.

It is also worth noting that the EU has been a global pioneer in this space. The EMA established the world’s first formal regulatory pathway for biosimilars back in 2005 and approved its first biosimilar in 2006, a full four years before the BPCIA was even signed into law in the U.S..12 This long history has given European regulators, physicians, and payers over 15 years of real-world experience with biosimilars, a depth of experience the U.S. is only now beginning to accumulate.

Dissecting “8+2+1”: A Granular Analysis of EU Exclusivity

The heart of the EU’s exclusivity system for all new medicines is the elegantly named “8+2+1” rule. This formula provides a clear and predictable timeline for innovator protection and competitor entry.41 Let’s break it down step-by-step:

- 8 Years of Data Exclusivity: From the moment an innovator drug (either small molecule or biologic) receives its initial marketing authorization from the EMA, a clock starts ticking. For the next eight years, no generic or biosimilar company can use or reference the innovator’s preclinical and clinical trial data to support its own application.41 In effect, this means a follow-on application cannot even be submitted to the EMA until this eight-year period has elapsed. This is the “data protection” period.

- +2 Years of Market Protection: The eight years of data exclusivity are immediately followed by an additional two years of market protection. During this two-year window (years 9 and 10 of the drug’s life), a generic or biosimilar version can be submitted to and approved by the EMA. However, the approved follow-on product cannot be launched or placed on the market until the full 10-year period is over.41 This provision guarantees the innovator a minimum of a decade-long monopoly on the market, even if its patents have expired sooner.

- +1 Year Extension: The framework offers one potential extension. An innovator can earn one additional year of market protection (bringing the total to 11 years) if, within the first eight years of its initial authorization, it secures approval for a significant new therapeutic indication that is deemed to provide a “significant clinical benefit” compared to existing therapies.33 This incentivizes companies to continue researching new uses for their approved medicines.

This “8+2+1” structure provides a clear, transparent, and uniform timeline of protection that stands in stark contrast to the variable and often longer periods of exclusivity seen in the U.S., particularly for biologics.

Generics vs. Biosimilars in the EU: Comparing Approval Standards

While the commercial exclusivity rules are harmonized, the scientific and regulatory standards for approving follow-on products are, rightly, very different, mirroring the underlying science.

For a generic small-molecule drug, the approval pathway is relatively straightforward. The applicant must demonstrate that its product contains the same active substance, in the same quantity and pharmaceutical form, as the reference medicine. The key hurdle is to prove “bioequivalence” through pharmacokinetic studies, showing that the generic drug produces the same levels of the active substance in the body over time as the original.49

For a biosimilar, the pathway is far more demanding. The EMA does not consider a biosimilar to be a generic of a biological medicine.12 The goal is not to prove identity, but to demonstrate high similarity through a comprehensive “comparability exercise”.12 This is a step-wise process that begins with extensive, head-to-head analytical and functional studies to compare the physicochemical and biological properties of the biosimilar and the reference product. Based on the results of this foundational analysis, the EMA then determines the extent of non-clinical (animal) and clinical (human) studies required to confirm that there are no clinically meaningful differences in terms of quality, safety, and efficacy.17 This rigorous, science-driven approach ensures that while a biosimilar is not an identical copy, it can be used as safely and effectively as the original.

The European View on Interchangeability

Here we find another crucial point of divergence with the United States. The U.S. created the distinct, high-bar regulatory category of “interchangeable,” which allows for pharmacy-level substitution. The EU has taken a different, more pragmatic approach.

The EMA and the Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA), which represents the national regulatory bodies of the EU member states, have issued a clear scientific position: any biosimilar approved through the EMA’s centralized procedure is considered interchangeable with its reference product from a scientific viewpoint.12 This means a physician can confidently switch a patient from an innovator biologic to its biosimilar (or vice versa) with the expectation of the same clinical outcome.

However, the EMA’s authority stops there. The practical decision of whether a pharmacist can perform an automatic substitution without consulting the prescriber is not made at the EU level. Instead, this authority is delegated to the individual member states, each of which has its own healthcare system and policies.12 This creates a patchwork of substitution policies across Europe, but it strategically avoids the creation of a second, more costly regulatory hurdle for biosimilar developers, a key difference that can impact the speed and cost of market access.

Global Strategy: A Comparative Analysis of U.S. and EU Exclusivity Regimes

Having dissected the individual frameworks of the world’s two largest pharmaceutical markets, it is time to place them side-by-side. For any company with global ambitions—whether an innovator planning a blockbuster launch or a follow-on manufacturer eyeing a market entry—understanding the strategic trade-offs between the U.S. and EU systems is paramount. The differences in exclusivity periods, patent linkage, and litigation procedures are not mere technicalities; they are powerful forces that shape investment decisions, revenue forecasts, and the very timeline of competition.

The Exclusivity Showdown: A Comparative Table

To distill this complex information into an actionable format, we can construct a direct, at-a-glance comparison of the key provisions. This table serves as a strategic dashboard, highlighting the critical variables that define the commercial landscape in each jurisdiction.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of U.S. and EU Exclusivity Frameworks

| Feature | U.S. Small Molecule (Hatch-Waxman) | U.S. Biologic (BPCIA) | EU Small Molecule & Biologic (EMA) |

| Governing Act | Hatch-Waxman Act (1984) | BPCIA (2010) | Directive 2001/83/EC & Regulation 726/2004 |

| Base Exclusivity Period | 5 years (New Chemical Entity) | 12 years (Reference Product) | 8 years (Data) + 2 years (Market) = 10 years total |

| Application Filing Bar | 4 years (for Para. IV challenge) | 4 years | 8 years |

| Follow-on Approval Bar | 5 years | 12 years | 10 years |

| Potential Exclusivity Extension | +3 years (new study), +6 months (pediatric) | +6 months (pediatric) | +1 year (new indication with significant clinical benefit) |

| Total Max Potential Exclusivity | ~8.5 years | ~12.5 years | 11 years |

| Follow-on Product Name | Generic | Biosimilar / Interchangeable | Generic / Biosimilar |

| Approval Standard | Bioequivalence | Biosimilarity / Interchangeability | Bioequivalence / Biosimilarity |

| Patent Linkage System | Public: Orange Book | Private: “Patent Dance” | None (patent litigation is separate) |

| Automatic Litigation Stay | 30 months | None | N/A |

This consolidated view is essential for your teams. It transforms a vast amount of disparate legislative detail into a single, digestible tool. A business development executive can immediately see from the “Total Max Potential Exclusivity” row that a new biologic has a longer potential monopoly in the U.S. (12.5 years) than in the EU (11 years), a critical input for global revenue forecasting. A legal strategist looking at the “Automatic Litigation Stay” row understands that the risk-reward calculus for challenging a small-molecule patent in the U.S. is fundamentally different from that of a biologic, where no such stay exists. This table turns abstract knowledge into a practical framework for strategic decision-making.

Why the Durations Differ: Policy Debates and Economic Arguments

The stark differences in the table, particularly the 12-year U.S. biologic exclusivity versus the EU’s 10-year standard, are the product of different legislative histories and policy priorities.

The U.S. rationale for its extended 12-year “fortress” for biologics was built on the arguments of higher R&D costs, greater manufacturing complexity, and the perceived weakness of patent protection for such complex molecules.21 It was a policy choice to heavily incentivize investment in the burgeoning biotech sector. However, as we have established, recent empirical data directly challenges many of these foundational assumptions, showing similar development times and no statistically significant difference in costs compared to small molecules, while also revealing higher clinical success rates for biologics.22 This has fueled a persistent policy debate in Washington, with numerous legislative proposals introduced over the years to shorten the 12-year period, though none have succeeded to date.50

The EU’s harmonized “8+2+1” approach, on the other hand, represents a different philosophy. It implicitly argues that a guaranteed 10-year monopoly, with the potential for an 11th year, provides a sufficient and balanced incentive for innovation across the board, for both small molecules and biologics.41 The European system prioritizes predictability and uniformity over the bespoke, and arguably more generous, protection offered to biologics in the U.S. This is not a static landscape, however. The EU is currently in the midst of a major overhaul of its pharmaceutical legislation, with proposals from the European Commission and Parliament that could modify the baseline exclusivity periods, potentially shortening them while offering new conditional extensions to incentivize addressing unmet medical needs or launching products across all EU member states.46 This demonstrates that the “correct” length of exclusivity is a dynamic and hotly contested issue on both sides of the Atlantic.

Strategic Implications for Global Launch and Portfolio Management

These divergent frameworks have concrete, real-world consequences for how companies manage their portfolios and plan their global launches.

For an innovator company, the longer and more robust exclusivity period for biologics in the U.S. makes it the single most important market for recouping R&D investment and maximizing profitability. The strategic focus is often on securing the U.S. market for as long as possible, using the full 12-year exclusivity period and a formidable patent strategy to delay competition.

For a follow-on manufacturer of biosimilars, the calculus is reversed. The EU’s shorter 10-year exclusivity period means the market opens up sooner. This, combined with a more streamlined regulatory process that lacks the “interchangeable” hurdle and a patent litigation system that is separate from the regulatory timeline, often makes Europe a more attractive initial launch market for biosimilars. Companies can gain valuable real-world market experience and begin generating revenue in the EU while navigating the longer exclusivity period and more complex “patent dance” in the U.S.

Ultimately, a one-size-fits-all global strategy is doomed to fail. Success requires a deeply nuanced and tailored approach, with distinct patent filing strategies, regulatory roadmaps, and commercial launch plans optimized for the unique rules of engagement in each major market.

The Market Battlefield: Generic Price Cliffs vs. Biosimilar Erosion

The true test of these complex regulatory frameworks lies not in the text of the laws, but in their real-world commercial impact. When the walls of exclusivity finally crumble, what happens next? The market dynamics for a small-molecule drug facing generic competition are a world apart from those of a biologic facing biosimilars. One is a sudden, dramatic plunge off a cliff; the other is a slow, grinding erosion. Understanding the forces that drive these different outcomes is essential for forecasting revenue, managing lifecycle transitions, and developing effective competitive strategies.

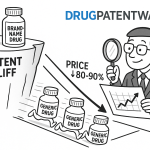

The Generic Paradigm: The Price Cliff

The entry of the first generic competitor for a small-molecule drug is one of the most predictable and dramatic events in the pharmaceutical industry. The term “patent cliff” is no exaggeration.

Once an ANDA is approved and launched, the market shift is swift and brutal for the innovator. Because generics are identical copies, pharmacists can automatically substitute them for the brand-name product, and payers (insurers and PBMs) aggressively push their use to control costs. The result is a rapid and massive loss of market share for the innovator, often exceeding 90% within the first year.52

This rapid uptake is accompanied by precipitous price drops. The first generic may launch at a modest discount, but as more competitors enter the market—often facilitated by the relatively low cost of generic development—intense price competition ensues. It is not uncommon for generic prices to plummet by 80-90% or more compared to the brand-name drug’s price just before exclusivity loss.54 For the innovator company, this means that a multi-billion-dollar revenue stream can evaporate almost overnight.

The Biosimilar Reality: A Gradual Erosion

The arrival of a biosimilar is a far more nuanced and protracted affair. There is no cliff, but rather the beginning of a long, slow erosion of the innovator’s market dominance.

The price discounts offered by the first biosimilars are typically much more modest, often in the range of 15-30% off the innovator’s price, not 80%.4 Market penetration is also significantly slower. It can take years for biosimilars to capture a majority share of the market, and in many cases, the innovator biologic retains a significant portion of sales long after competition begins.52

Several factors contribute to this slower, grinding dynamic:

- High Barriers to Entry: Developing a biosimilar is a massive undertaking. It can cost between $100 million and $250 million and take 7 to 8 years, compared to just $1-4 million and a couple of years for a typical generic.28 This immense investment means fewer companies can compete, leading to less aggressive price competition.

- Manufacturing Complexity: The “process is the product” nature of biologics creates a steep learning curve and a significant technical barrier. Companies with deep experience in biomanufacturing have a major advantage, further limiting the pool of potential competitors.58

- Lack of Automatic Substitution: In the U.S., unless a biosimilar has achieved the rare “interchangeable” designation, it cannot be automatically substituted at the pharmacy. Prescribers must actively choose to write a prescription for the biosimilar, and payers must be convinced to favor it on their formularies. This creates significant friction in market uptake.59

- Physician and Patient Hesitancy: Because biosimilars are “similar” but not “identical,” there can be a degree of hesitancy among physicians and patients to switch from a trusted innovator product, particularly for patients who are stable on their current therapy. Overcoming this inertia requires significant education and marketing efforts.39

This combination of factors means that while biosimilars do introduce competition and create significant healthcare savings, they do not trigger the same kind of immediate market disruption as generics. This gives innovator companies a much longer runway to manage the lifecycle of their biologic products.

Innovator Counter-Strategy: The Rise of the “Patent Thicket”

Given the immense revenue at stake, innovator companies do not passively wait for their exclusivity to expire. They have developed sophisticated and aggressive legal strategies to extend their monopolies for as long as possible. The most powerful of these strategies, particularly in the biologics space, is the creation of a “patent thicket.”

A patent thicket is a dense, overlapping web of secondary patents filed long after the initial patent on the core molecule. These patents are not designed to protect the fundamental invention, but rather to create a formidable legal fortress around it, covering every conceivable aspect of the product: new formulations, specific dosing regimens, manufacturing process improvements, delivery devices, and new methods of use.60

This strategy is especially potent for biologics due to the unique features of the BPCIA litigation system. The lack of a public Orange Book and the inclusion of process patents allow an innovator to build a massive, opaque portfolio and then threaten to assert dozens or even hundreds of patents against any potential biosimilar challenger. The goal is not necessarily to win every single lawsuit, but to make the prospect of litigation so complex, time-consuming, and astronomically expensive that the challenger is forced to the negotiating table to accept a settlement that delays their market entry.63

Case Study: AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab)

The quintessential example of this strategy is AbbVie’s defense of Humira, the best-selling drug in history. The primary patent on the adalimumab molecule expired in the U.S. in 2016. However, AbbVie was able to prevent any biosimilar competition in the U.S. until 2023. How? By constructing an unprecedented patent fortress. AbbVie filed over 247 patent applications related to Humira, with the vast majority filed after the drug was already on the market.61 When biosimilar companies sought to enter, AbbVie sued them, asserting over 100 patents in some cases. Faced with this legal onslaught, every single biosimilar competitor settled, agreeing to delay their U.S. launch by years. This strategy secured AbbVie billions of dollars in additional revenue and stands as a masterclass in leveraging a patent thicket to extend a drug’s commercial life far beyond its core patent.61

Case Study: Amgen’s Enbrel (etanercept)

Amgen’s strategy for its blockbuster biologic Enbrel demonstrates that it’s not always about the sheer number of patents. Enbrel was approved in 1998, and its primary patents have long since expired. Yet, no biosimilar has launched in the U.S., and none are expected until 2029—a staggering 31 years after its initial approval. This extraordinary longevity was achieved by acquiring and aggressively defending two key, late-expiring patents from another company. These patents, filed in the early 1990s just before a change in U.S. patent law, were not granted until 2011 and 2012, giving them expiration dates in the late 2020s. Amgen successfully defended the validity of these patents in court against a challenge from Novartis, effectively blocking all biosimilar entry for another decade.61 This case highlights the immense strategic value of a few well-placed, resilient patents.

These cases reveal a critical truth about the modern pharmaceutical landscape. The statutory, or de jure, exclusivity periods granted by law are merely the starting point of the conversation. The real-world, or de facto, period of market monopoly is often far longer, particularly for biologics. Recent data shows that the median time from FDA approval to the first biosimilar competition is a staggering 20.3 years—a full eight years longer than the already generous 12-year statutory exclusivity period.22 For small molecules, the median time to generic entry is 12.6 years, also well beyond their 5-year NCE exclusivity, but the gap is smaller.22 This gap between the law on the books and the reality on the ground is where the strategic battle is fought and won, through the meticulous construction of patent portfolios, complex litigation, and the high scientific and financial barriers to entry that define the biosimilar market. For any company planning to compete in this space, focusing only on the statutory clock is a grave strategic error. The real timeline is written in the patents.

Turning Intelligence into Advantage: Strategic Application for Business Leaders

Understanding the divergent worlds of small-molecule and biologic exclusivity is not merely an intellectual exercise; it is the foundation of effective strategy in the biopharmaceutical industry. For the leaders in R&D, intellectual property, and business development, the ability to translate this complex intelligence into a concrete, actionable playbook is what separates market leaders from the rest of the pack. This final section distills the preceding analysis into a strategic framework for building resilient patent portfolios, leveraging competitive intelligence, and navigating the future of pharmaceutical innovation.

Building a Resilient Patent Portfolio: A Dual-Track Approach

A one-size-fits-all approach to patent strategy is obsolete. The nature of the molecule dictates the architecture of its defense.

For small molecules, the strategy is one of precision and targeted reinforcement. The primary goal is to secure a strong, defensible composition of matter patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient itself. This is the base patent that will be listed in the Orange Book and will be the primary target of a Paragraph IV challenge. However, the strategy cannot end there. To defend against these challenges and extend the product’s lifecycle, a layered approach of secondary patents is essential. This includes patents on specific formulations (e.g., an extended-release version), novel methods of use for new indications, and different crystalline forms (polymorphs) of the molecule.61 Each of these secondary patents can be listed in the Orange Book, creating additional hurdles for a generic challenger to overcome.

For biologics, the strategy is one of overwhelming fortification. It is about building an impenetrable fortress. While a patent on the core biologic molecule is still important, its value is often diminished because it is typically filed very early in development and may expire before or shortly after the 12-year BPCIA exclusivity period ends.42 Therefore, the strategic emphasis must shift to creating a dense and daunting “patent thicket.” This requires a relentless focus on patenting every conceivable aspect of the product beyond the molecule itself. The most critical areas are the manufacturing processes—the proprietary cell lines, the unique purification methods, the specific bioreactor conditions—as these are central to a biologic’s identity and are fair game in BPCIA litigation.42 This must be supplemented with patents covering all formulations, delivery devices (e.g., auto-injectors), and specific dosing regimens for every approved indication. The goal is to create a legal minefield so dense and complex that the cost and risk of challenging it become prohibitive for a potential biosimilar competitor.

Competitive Intelligence and Freedom-to-Operate in the Modern Era

In this dynamic environment, a patent portfolio is not just a defensive shield; it is one of the richest available sources of competitive intelligence.68 Every patent application filed by a competitor is a public declaration of their strategic intent. It reveals their R&D priorities, the specific scientific problems they are trying to solve, the technologies they consider valuable, and the commercial markets they are targeting. Systematically analyzing this data allows a company to move from a reactive posture to a proactive, data-driven offense.

Conducting thorough patent landscape and freedom-to-operate (FTO) analyses is no longer optional; it is a fundamental part of risk management and strategic planning. Before investing hundreds of millions of dollars into a new clinical program, you must know if you are sailing into a competitor’s patent-protected waters. This analysis can identify potential infringement risks early, allowing for “design-around” strategies, and can also uncover “white space”—areas of untapped innovation where your company can establish a dominant IP position.

The Role of Platforms like DrugPatentWatch

Navigating this deluge of data manually is an impossible task. This is where specialized business intelligence platforms become indispensable. These tools are no longer a luxury for the largest players but a necessity for any serious contender in the pharmaceutical space.

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are designed to aggregate and synthesize the disparate data streams required for high-level strategic planning. They provide integrated, up-to-date information on patent expiration dates, regulatory exclusivities, ongoing litigation across both Hatch-Waxman and BPCIA frameworks, and the development pipelines of generic and biosimilar competitors.60 Critically, they can also provide intelligence on the terms of out-of-court settlements, which are often the true determinants of market entry dates but are not typically public knowledge.70 By leveraging such a platform, your teams can move beyond simple data collection to true intelligence analysis, making more informed, data-driven decisions on everything from R&D pipeline prioritization and M&A targeting to market entry timing and risk assessment.

Navigating the Future: New Technologies and Legislative Headwinds

The rules of the game are not static. The ground is constantly shifting under our feet, driven by breathtaking technological advancements and a volatile legislative environment. A forward-looking strategy must account for these future trends.

The Impact of AI and New Modalities

The biopharmaceutical landscape is being revolutionized by new technologies. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are dramatically accelerating the pace of drug discovery, identifying novel targets and designing new molecules in silico.71 Gene-editing technologies like CRISPR are opening the door to curative therapies that were once the stuff of science fiction.71 And personalized medicine is moving from concept to reality, with treatments tailored to an individual’s unique genetic profile.

These advancements are creating novel and complex IP challenges. How do you patent an invention when the “inventor” is an AI algorithm? How do you define the scope of a patent for a personalized therapy that may only be applicable to a tiny subset of the population? How do you navigate the crowded and contested patent landscape around a foundational technology like CRISPR? These are the next-generation questions that IP strategists must begin to answer today to protect the innovations of tomorrow.

The Shifting Sands of Legislation

Simultaneously, the legal frameworks that govern exclusivity are under constant scrutiny and are subject to change. In the U.S., there is a persistent political appetite for patent reform aimed at curbing perceived abuses and lowering drug prices. Ongoing initiatives include efforts by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to challenge what it deems improper Orange Book listings, legislative proposals like the PREVAIL Act and the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act (PERA) that could reshape the landscape for patent litigation and eligibility, and calls to exercise “march-in rights” on federally funded inventions.74

In the EU, the comprehensive revision of the pharmaceutical legislation is actively debating the future of the “8+2+1” rule, with various proposals to shorten or modify the baseline periods of exclusivity while adding new incentives.46 The only certainty is that the rules of engagement will continue to evolve. Success in this environment demands not just a robust strategy for today, but the vigilance and adaptability to anticipate and respond to the changes of tomorrow.

Key Takeaways

For the busy executive, attorney, or investor, the complex world of biologic and small-molecule exclusivity can be distilled into several core strategic truths that should guide decision-making:

- Science Is Destiny: The fundamental scientific chasm between small, chemically synthesized molecules and large, biologically derived proteins is the root cause of their divergent regulatory, legal, and commercial pathways. Every strategic decision must be grounded in this core reality.

- The U.S. Exclusivity Justification Is Under Fire: The long-standing arguments used to justify the 12-year market exclusivity period for biologics in the U.S.—that they take longer, cost more, and are riskier to develop—are being systematically challenged by emerging empirical data. This creates significant political and legislative risk for the status quo and opportunities for those advocating for change.

- De Facto Exclusivity Trumps De Jure Exclusivity: The statutory exclusivity period written into law is only the beginning. The effective market monopoly, particularly for biologics, is often far longer, driven by sophisticated patent thicket strategies. Data shows the median time to biosimilar competition in the U.S. is over 20 years, far exceeding the 12 years granted by law. Strategic focus must be on the patent portfolio, not just the regulatory clock.

- The BPCIA Is a Double-Edged Sword: The structure of the U.S. biosimilar pathway (the BPCIA)—with its lack of a public patent list and its inclusion of manufacturing process patents—inadvertently creates a perfect environment for the patent thicket defense. This makes it a more litigation-heavy and uncertain pathway than the Hatch-Waxman system for small molecules.

- The EU Is the Biosimilar Bellwether: With its harmonized exclusivity rules and over 15 years of experience, the European market serves as a crucial testing ground and leading indicator for global biosimilar competition, uptake, and pricing dynamics.

- Intelligence Is a Strategic Imperative: Navigating this complex, high-stakes environment is impossible without a deep and continuous integration of competitive intelligence. Leveraging specialized platforms like DrugPatentWatch to monitor patent landscapes, track litigation, and analyze competitor pipelines is no longer a luxury but a core component of modern biopharmaceutical strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why do biologics still get 12 years of exclusivity in the U.S. if recent data shows their development isn’t necessarily longer or riskier than small molecules?

This is the central policy debate in the U.S. right now. The 12-year period was established by the BPCIA in 2010 based on the prevailing arguments at the time that biologics required significantly more time, investment, and risk to develop. While recent comprehensive studies challenge these assumptions, changing the law is a complex political process. Innovator biotech companies argue that the 12-year period is still essential to incentivize investment in next-generation, high-risk therapies, while payers, policymakers, and biosimilar manufacturers argue the data supports shortening this period to increase competition and lower healthcare costs. For now, the 12-year exclusivity remains the law of the land, but it is under intense scrutiny.

2. What is the single biggest strategic difference between the “Patent Dance” under the BPCIA and the Orange Book litigation process under Hatch-Waxman?

The single biggest strategic difference is the presence of an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval in the Hatch-Waxman process, which is completely absent in the BPCIA. When an innovator sues a generic challenger under Hatch-Waxman, it automatically freezes the generic’s potential approval for up to 30 months, providing a clear and predictable timeline for litigation. For biologics, there is no such automatic stay. This means a biosimilar could theoretically receive FDA approval and decide to launch “at risk” while patent litigation is ongoing, a high-stakes gamble that exposes the biosimilar company to potentially massive damages if the patents are later found to be valid and infringed. This fundamental difference dramatically alters the risk calculus and strategic dynamics for both innovators and challengers.

3. From a strategic perspective, is it better to launch a biosimilar first in the U.S. or the EU?

For most biosimilar developers, the European Union is the preferred initial launch market. There are several key reasons for this: 1) The exclusivity period is shorter (10 years base vs. 12 in the U.S.), meaning the market opens up earlier. 2) The regulatory pathway is more established and arguably more streamlined, as it does not have the additional, costly hurdle of seeking an “interchangeable” designation. 3) The patent litigation system is separate from the regulatory approval process and is often seen as less complex than the U.S. “patent dance.” Launching first in the EU allows a company to start generating revenue and gain valuable real-world market and manufacturing experience while it navigates the longer and more complex path to the U.S. market.

4. What is a “patent thicket,” and why is it a more effective strategy for biologics than for small molecules?

A “patent thicket” is a dense, overlapping web of secondary patents that an innovator company builds around a successful drug to deter competition. These patents cover aspects like formulations, manufacturing processes, and methods of use, rather than the core drug molecule itself. This strategy is particularly effective for biologics for two main reasons rooted in the BPCIA. First, unlike the Hatch-Waxman Act, the BPCIA allows litigation over manufacturing process patents. Since biologics are defined by their complex manufacturing processes, this opens a vast area for patenting. Second, the BPCIA lacks a public, curated list of relevant patents like the Orange Book. This uncertainty forces a biosimilar challenger to contend with a potentially huge and unknown number of patents, dramatically increasing the cost, time, and risk of litigation, which often pressures them into settling for a delayed launch.

5. How are new technologies like AI and CRISPR expected to change the patent and exclusivity landscape for pharmaceuticals in the next decade?

These technologies are poised to create significant disruption. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is accelerating drug discovery, but it raises fundamental questions about inventorship—can an AI be an inventor? Patent offices globally are grappling with this, but the current consensus is that a human must be the inventor. This will lead to new strategies for documenting the “inventive step” provided by human researchers who are using AI tools. CRISPR and other gene-editing tools are creating a new class of potentially curative therapies. The patent landscape here is already incredibly complex and litigious, with foundational patents being fiercely contested. For these new modalities, patent strategy will focus not just on the therapy itself, but on the delivery systems, diagnostic methods used to select patients, and the gene-editing tools themselves, creating new and even more complex types of patent thickets.

Works cited

- Biologics vs Small Molecules: A New Era in Drug Development – SYNER-G, accessed August 18, 2025, https://synergbiopharma.com/biologics-vs-small-molecules/

- Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry | Congressional Budget Office, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – Congress.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R44643/R44643.3.pdf

- “The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act 10–A Stocktaking” by Yaniv Heled – Texas A&M Law Scholarship, accessed August 18, 2025, https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/journal-of-property-law/vol7/iss1/3/

- The Evidence Is Clear: Biosimilar Competition Will Achieve More Savings for Patients Than Build Back Better’s Negotiations, accessed August 18, 2025, https://biosimilarscouncil.org/resource/the-evidence-is-clear-biosimilar-competition-will-achieve-more-savings-for-patients-than-build-back-betters-negotiations/

- Difference Between Small Molecule and Large Molecule Drugs – Caris Life Sciences, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.carislifesciences.com/difference-between-small-molecule-and-large-molecule-drugs/

- Understanding Biologic and Biosimilar Drugs, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/understanding-biologic-and-biosimilar-drugs

- Regulatory Knowledge Guide for Small Molecules | NIH’s Seed, accessed August 18, 2025, https://seed.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2024-03/Regulatory-Knowledge-Guide-for-Small-Molecules.pdf

- Small Molecules vs. Biologics: Key Drug Differences – Allucent, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/points-consider-drug-development-biologics-and-small-molecules

- Frequently Asked Questions About Therapeutic Biological Products …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/therapeutic-biologics-applications-bla/frequently-asked-questions-about-therapeutic-biological-products

- Foundational Concepts Generics and Biosimilars – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/154912/download

- Biosimilar medicines: Overview | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview

- An Overview of Biosimilar Regulatory Approvals by the EMA and …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-biosimilar-landscape-an-overview-of-regulatory-approvals-by-the-ema-and-fda/

- How Similar Are Biosimilars? What Do Clinicians Need to Know About Biosimilar and Follow-On Insulins?, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5669137/

- Differences between Biologics and Small Molecules | UCL …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/therapeutic-innovation-networks/differences-between-biologics-and-small-molecules

- Commemorating the 15th Anniversary of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/commemorating-15th-anniversary-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act

- Biosimilar medicines: marketing authorisation | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/biosimilar-medicines-marketing-authorisation

- www.fightcancer.org, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/understanding-biologic-and-biosimilar-drugs#:~:text=Like%20all%20drugs%2C%20biologics%20are,administered%20via%20injection%20or%20infusion.

- What Are Biologic and Small Molecule Drugs Used For? – GoodRx, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.goodrx.com/drugs/biologics/vs-small-molecule-drugs

- Defining the difference: What Makes Biologics Unique – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3564302/

- Pre-market development times for biologic versus small- molecule drugs – Geneva Graduate Institute, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.graduateinstitute.ch/sites/internet/files/2019-10/GHC-webinar-data-drugs.pdf

- Differential Legal Protections for Biologics vs Small-Molecule Drugs …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39585667/

- 1 Differential Legal Protections for Biologics vs. Small-Molecule …, accessed August 18, 2025, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/126180/1/2024.08.03_manuscript.pdf

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 18, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- www.fda.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters#:~:text=The%20%22Drug%20Price%20Competition%20and,Drug%2C%20and%20Cosmetic%20Act%20(FD%26C

- Biosimilar vs Generic Drugs: Key Differences in Healthcare – Medical Packaging Inc, accessed August 18, 2025, https://medpak.com/biosimilar-vs-generic-drugs/

- Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 18, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- What Are the Patent Litigation Differences Between the BPCIA and …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.winston.com/en/legal-glossary/BPCIA-Hatch-Waxman-Act-differences

- Data & Market Exclusivity As Incentives in Drug Development – Scendea, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.scendea.com/articles/blog-post-title-one-25srn-58l3m-hef63

- The Benefits From Giving Makers Of Conventional `Small Molecule’ Drugs Longer Exclusivity Over Clinical Trial Data – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3804334/

- Comparison of the Hatch-Waxman Act and the BPCIA – Fish …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fr.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Comparison-of-Hatch-Waxman-Act-and-BPCIA-Chart.pdf

- Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 – Wikipedia, accessed August 18, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biologics_Price_Competition_and_Innovation_Act_of_2009

- Biologics Price Competition & Innovation Act (BPCIA): Litigation …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://ktslaw.com/-/media/2022/Biologics-Price-Competition-And-Innovation-Act-BPCIA-Litigation-Considerations-w0344767.pdf

- Biosimilarity and Interchangeability in the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 and FDA’s 2012 Draft Guidance for Industry – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3827854/

- Interchangeability for Biologics is a Legal Distinction in the USA, Not a Clinical One – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9190447/

- Switching Between Biosimilars and Their Reference Counterparts with Dr. Sarah Yim | FDA, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/switching-between-biosimilars-and-their-reference-counterparts-dr-sarah-yim

- The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act 10–A Stocktaking – Texas A&M Law Scholarship, accessed August 18, 2025, https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1151&context=journal-of-property-law

- How Long Is Data Exclusivity for Biologics in the US and EU? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed August 18, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/how-long-is-data-exclusivity-for-biologics-in-the-us-and-eu

- Implications of the BPCIA on the IP Strategies of Brand Companies and Biosimilar Developers | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/implications-bpcia-ip-strategies-brand-companies-and-biosimilar/

- Understanding data exclusivity and market protection – SPS …, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/understanding-data-exclusivity-and-market-protection/

- Biosimilars in the EU – Information guide for healthcare professionals – European Medicines Agency, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf

- Biosimilars markets: US and EU compared – GaBIJ, accessed August 18, 2025, https://gabi-journal.net/biosimilars-markets-us-and-eu-compared.html

- Proposed new legislation on regulatory data exclusivity and market protection for new medicines in Europe – Kilburn & Strode, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.kilburnstrode.com/knowledge/european-ip/proposed-new-legislation-on-regulatory-data-exclus

- Data exclusivity, market protection, orphan and paediatric rewards – European Medicines Agency, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/presentation/presentation-data-exclusivity-market-protection-orphan-and-paediatric-rewards-s-ribeiro_en.pdf

- Data exclusivity | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/glossary-terms/data-exclusivity

- Generic and hybrid medicines | European Medicines Agency (EMA) – European Union, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/marketing-authorisation/generic-hybrid-medicines

- USMCA Compromise Drops Key Biologics Exclusivity Provisions | Avalere Health Advisory, accessed August 18, 2025, https://advisory.avalerehealth.com/insights/usmca-compromise-drops-key-biologics-exclusivity-provisions

- EU Pharma Law Package: Council Position on Reduction of Regulatory Exclusivity Rights, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.hoganlovells.com/en/publications/eu-pharma-law-package-council-position-on-reduction-of-regulatory-exclusivity-rights-

- ISSUE BRIEF – HHS ASPE – HHS.gov, accessed August 18, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3a05af053eeeaa4c7c95457dcafefa68/ASPE-Competition-in-the-Biologics-Market.pdf

- Strategic Patenting by Pharmaceutical Companies – Should Competition Law Intervene? – PMC, accessed August 18, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7592140/