For decades, patients, policymakers, and industry leaders have been locked in a complex struggle, searching for a balance between rewarding groundbreaking innovation and ensuring affordable access to life-saving medicines. At the very heart of this debate lies a powerful, yet historically untouched, legal provision known as march-in rights.

Born from the landmark Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, these rights grant the U.S. government the authority to effectively break patent exclusivity on inventions developed with federal funding under specific circumstances. For over 40 years, march-in rights have been the “nuclear option” of intellectual property law—a tool so potent that its mere existence was meant to shape behavior, yet one that no federal agency has ever dared to fully deploy.

But the ground is shifting. Faced with relentless public pressure over drug prices and a new administrative push to re-evaluate the government’s authority, the long-dormant specter of march-in rights is awakening. The central question, once a purely academic exercise, is now a pressing reality for every pharmaceutical executive, investor, and university tech transfer office: Can the government use march-in rights to lower prescription drug costs? And if it does, what will that mean for the future of American innovation?

This article will provide an exhaustive exploration of march-in rights, from their legislative origins and legal framework to the historical petitions that have tested their limits. We will dissect the arguments for and against their use as a price control mechanism, analyze the profound economic implications for the pharmaceutical industry, and examine how companies can leverage competitive intelligence to navigate this evolving landscape. This is not just a legal analysis; it’s a strategic guide to understanding one of the most significant potential disruptors to the biopharmaceutical ecosystem in a generation.

A Deep Dive into the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980

To truly grasp the significance of march-in rights, we must first travel back to the era that created them. The late 1970s in the United States were a period of economic anxiety and a growing fear that the nation was losing its innovative edge to global competitors like Japan and Germany. A significant part of the problem, lawmakers believed, was lurking within the federal government’s own policies.

The Pre-Bayh-Dole Landscape: A Patent Quagmire

Before 1980, when a private entity—be it a university, a non-profit research institution, or a small business—used federal funds to make an invention, the patent rights typically belonged to the U.S. government. The government’s policy, often referred to as the “title policy,” was to take title to these inventions and then, in theory, license them out to companies for development and commercialization.

The reality, however, was a bureaucratic nightmare. The federal government held a staggering portfolio of approximately 28,000 patents, but the system for licensing them was inefficient, inconsistent, and deeply unattractive to private industry. Companies were hesitant to invest the millions, or even billions, of dollars required to turn a raw scientific discovery into a marketable product if they could only get a non-exclusive license. Why, they reasoned, should we take all the financial risk of development only to have a competitor swoop in and sell the same product once we’ve proven it works?

The result was a catastrophic failure to translate taxpayer-funded research into public benefit. A 1978 report from the General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office) revealed the shocking truth: of the 28,000 patents owned by the federal government, fewer than 5% had ever been licensed for commercial development [1]. Groundbreaking discoveries made in university labs were languishing on shelves, a phenomenon often described as a “valley of death” between basic research and commercial application. Taxpayer dollars were funding discovery, but not delivery.

The Birth of Bayh-Dole: A Bipartisan Solution

It was against this backdrop of stalled innovation that two senators, Birch Bayh (a Democrat from Indiana) and Bob Dole (a Republican from Kansas), forged an unlikely and powerful partnership. They recognized that the government’s “title policy” was the problem. Their solution, radical at the time, was to flip the model on its head.

The University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act, universally known as the Bayh-Dole Act, proposed a simple yet profound change: allow universities, non-profits, and small businesses to retain ownership (to “elect title”) of the patents on inventions made with federal funding. The guiding philosophy was that these institutions, being closer to the science and more nimble than the federal bureaucracy, would be far more effective at finding commercial partners to develop their inventions.

By giving universities control over their own IP, the Act incentivized them to actively seek out private sector licensees. In turn, these private companies, able to secure the exclusive licenses necessary to justify massive R&D investments, would be more willing to take the risk of product development. It was a market-based solution designed to bridge the valley of death, transforming government-funded research from a sterile asset into a dynamic engine of economic growth and public benefit. The Act passed with overwhelming bipartisan support and was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on December 12, 1980.

The Genesis of March-In Rights: Section 203

While the primary goal of Bayh-Dole was to empower patent holders and spur commercialization, its architects were not naive. They understood that this new system, which granted private entities control over taxpayer-funded inventions, needed a critical safeguard. What if a university licensed a patent to a company that then failed to develop the product? What if a company holding an exclusive license for a crucial public health drug couldn’t produce enough of it during a crisis?

This is where Section 203 of the Act, the “march-in” provision, comes into play. It was designed as the ultimate safety net, a mechanism to ensure that the public’s interest remained paramount. It gives the funding federal agency the right to “march in” and demand that the original patent holder grant a license to another “responsible applicant” under “reasonable terms.” If the patent holder refuses, the government can grant the license itself.

This power is not unlimited. It is a tool of last resort, tethered to four specific circumstances, or “triggers,” which represent a failure by the patent holder or their licensee to fulfill their end of the Bayh-Dole bargain. Understanding these four triggers is the key to understanding the entire march-in debate.

The Four Triggers of March-In Rights: A Legal and Practical Dissection

The authority of a federal agency to exercise its march-in rights is strictly defined by 35 U.S. Code § 203(a). The agency must determine that one of four specific conditions has been met. Let’s dissect each of these triggers, as their precise wording and inherent ambiguities are the battlegrounds upon which all march-in petitions are fought.

Trigger 1: Failure to Achieve “Practical Application”

The first and perhaps most debated trigger allows the government to march in if it determines that action is necessary because the contractor or assignee has not taken, or is not expected to take within a reasonable time, effective steps to achieve “practical application” of the subject invention in its field of use.

What exactly is “practical application”? The Bayh-Dole Act itself provides a definition in Section 201(f):

“The term ‘practical application’ means to manufacture in the case of a composition or product, to practice in the case of a process or method, or to operate in the case of a machine or system; and, in each case, under such conditions as to establish that the invention is being utilized and that its benefits are… available to the public on reasonable terms.” [2]

This definition is a hornet’s nest of legal interpretation. While the first part seems straightforward—the product must be manufactured and used—the final clause, “available to the public on reasonable terms,” is the crux of the entire drug pricing controversy.

- The Argument: Proponents of using march-in for price control argue that a drug sold at an exorbitant price is, by definition, not “available to the public on reasonable terms.” They contend that if a medication is financially inaccessible to the patients who need it, its benefits are not being delivered, and thus, “practical application” has not been achieved.

- The Counterargument: The pharmaceutical industry and many legal scholars argue that “reasonable terms” was never intended to refer to price. They claim it refers to the logistical and contractual terms of making the product available on the market, such as through standard distribution channels. They insist that Congress deliberately chose not to include language about price controls in the Bayh-Dole Act and that interpreting it this way would fundamentally rewrite the law.

The Xtandi Case: A Modern Test Case

The prostate cancer drug Xtandi (enzalutamide) is the poster child for this debate. Developed with funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the U.S. Army at UCLA, Xtandi is sold in the U.S. for a price significantly higher than in other developed countries. Patient advocacy groups, led by Knowledge Ecology International (KEI), have filed multiple petitions with the NIH arguing that this price disparity proves the drug is not available on “reasonable terms,” thus triggering the march-in right [3]. To date, the NIH has rejected these petitions, stating that price alone is not a basis for marching in. However, the persistence of the Xtandi case continues to fuel the fire.

Trigger 2: Alleviating Health or Safety Needs

The second trigger allows the government to march in if action is necessary to alleviate health or safety needs which are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or their licensees.

This trigger is generally understood to be aimed at public health emergencies or severe supply chain disruptions. Imagine a bioterrorism event where a specific antidote is needed, or a pandemic where a licensed manufacturer cannot produce enough vaccine to meet urgent national demand. In such a scenario, the government could march in to license additional manufacturers to ramp up production quickly.

The Fabrazyme Case: A Glimpse into Supply Shortages

In 2010, the NIH faced a petition concerning Fabrazyme, a treatment for the rare Fabry disease. The manufacturer, Genzyme, was experiencing severe production problems due to viral contamination at its manufacturing plant, leading to a critical shortage of the drug for patients. A group of patients and researchers petitioned the NIH to use its march-in rights to license another company, Shire, which produced a similar drug, to help meet the demand [4].

The NIH ultimately denied the petition. It reasoned that Genzyme was already taking all possible steps to resolve the shortage, including rationing the existing supply and working with regulators to bring a new facility online. The NIH concluded that marching in would not have alleviated the shortage any faster than the measures Genzyme was already taking. While the petition was denied, the Fabrazyme case clearly illustrates the intended purpose of this second trigger: to address tangible shortages and access issues, not necessarily price.

Trigger 3: Public Use Requirements Not Met

The third trigger is closely related to the second. It permits a march-in if action is necessary to meet requirements for public use specified by Federal regulations and such requirements are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or licensees.

This trigger is more specific than the general “health or safety needs” clause. It applies when a particular federal regulation imposes a specific public use mandate on an invention. For example, if a regulation required that a government-funded diagnostic tool be made available to all federal hospitals, and the licensee refused to sell it to them, this could be grounds for marching in.

This trigger has been invoked less frequently in petitions because it requires a pre-existing, specific federal regulation that is being violated. However, like the first trigger, its language—”not reasonably satisfied”—leaves room for interpretation. Could a government agency pass a new regulation defining affordability as a “requirement for public use”? It’s a legal gray area that remains largely untested.

Trigger 4: Failure to Meet U.S. Manufacturing Requirements

The final trigger is a protectionist measure tied to another section of the Bayh-Dole Act. Section 204 stipulates that any exclusive license for a Bayh-Dole invention in the United States must contain a clause ensuring that the product will be “substantially manufactured in the United States.”

The fourth march-in trigger allows the government to act if a licensee has breached this U.S. manufacturing clause. However, this provision has a significant loophole: the funding federal agency can grant a waiver to this requirement if it determines that reasonable but unsuccessful efforts have been made to license to a U.S. manufacturer or that domestic manufacturing is not commercially feasible.

In our modern, globalized pharmaceutical supply chain, these waivers are common. It is often more cost-effective or practical to manufacture active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) or finished drug products overseas. As a result, this trigger has rarely been a central point of contention in march-in petitions. An analysis by KEI found that between 1995 and 2020, the NIH granted 98% of the waivers requested for this provision, making it a weak enforcement mechanism in practice [5].

The History of March-In Petitions: A Tale of Consistent Rejection

For a legal tool that generates so much discussion, the practical history of march-in rights is remarkably one-sided. Since the Bayh-Dole Act was passed, numerous petitions have been filed with various federal agencies—most notably the NIH—requesting the use of march-in rights. To date, not a single one has ever been granted.

Examining the most prominent cases reveals a consistent pattern in the government’s reasoning and provides critical insight into the high bar that petitioners must clear.

The CellPro Case (1997): The First Test

The very first march-in petition involved a company called CellPro, which had developed a technology for stem cell separation. The technology was exclusively licensed to them by Johns Hopkins University, but a competing company, Baxter Healthcare, alleged that CellPro was not making the technology widely available and was infringing on their own patents. Baxter, along with some researchers, petitioned the NIH to march in and grant them a license.

The NIH, in a 1997 letter, denied the petition [6]. The director at the time, Dr. Harold Varmus, established a key precedent. He argued that march-in rights should not be used as a tool to settle patent infringement disputes or to punish a licensee for business practices that a competitor dislikes. The core issue, Varmus stated, was whether the licensee was taking effective steps to bring the invention to the public. Since CellPro was commercializing the technology, the NIH found no grounds to march in, even if there were other legal disputes surrounding it.

The Norvir (Ritonavir) Case (2004): The Price Debate Ignites

If CellPro was the first test, the case of Norvir was the one that first brought the issue of pricing to the forefront. Norvir (ritonavir) is an HIV/AIDS medication developed with NIH funding. Initially used as a standalone antiretroviral, it was later discovered to be a powerful “booster,” increasing the effectiveness of other HIV drugs. In 2003, the manufacturer, Abbott Laboratories (now AbbVie), raised the price of Norvir by 400%, from $1.71 per day to $8.57 per day.

The price hike was not aimed at patients using Norvir as a standalone treatment but was strategically designed to make it more expensive for competing pharmaceutical companies to use Norvir in their own combination pills. This move was widely seen as anti-competitive and sparked outrage among AIDS activists and patient groups. They filed a petition with the NIH, arguing for the first time that a drug’s high price meant it failed the “reasonable terms” clause of the “practical application” definition.

In a landmark decision in 2004, the NIH once again denied the petition [7]. The agency’s reasoning was explicit and has formed the bedrock of its policy ever since:

“Because the legislative history of the Bayh-Dole Act is silent on the issue of product pricing and because the NIH finds no other compelling justification for the use of this extraordinary remedy, the NIH concludes that… a march-in proceeding is not warranted.”

The NIH argued that the government should not use march-in rights to control prices because other government agencies and market forces were better suited to address such issues. This decision firmly established the NIH’s long-standing position that “price alone is not a basis for march-in.”

The Fabrazyme (Agalsidase Beta) Case (2010): The Supply Chain Argument

As discussed earlier, the 2010 petition regarding Fabrazyme focused on the second trigger: alleviating health needs due to a supply shortage. While the petition was ultimately denied, it was significant because it moved the debate away from the contentious issue of price and onto the more tangible problem of physical access. The NIH’s denial was pragmatic; they determined that marching in would be a slow, bureaucratic process that would not solve the immediate shortage faster than the manufacturer’s own remediation efforts. This case underscored that even when a petition aligns with the clearer, non-price-related triggers, the government will still weigh the practical outcomes before taking such a drastic step.

The Xtandi (Enzalutamide) Case (2016-Present): The Most Persistent Challenge

No drug has become more synonymous with the march-in debate than the prostate cancer treatment Xtandi. The case against Xtandi, spearheaded by KEI and other patient advocates, is built on a simple and powerful comparison: the drug’s price in the United States is multiples higher than its price in other wealthy nations like Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

- The Petitioners’ Argument: Petitioners argue that this price disparity is prima facie evidence that the drug is not being offered to the American public “on reasonable terms.” They contend that American taxpayers, who funded the initial research through NIH and Army grants, are being forced to pay more than anyone else in the world for the resulting product. This, they claim, is a clear failure to meet the requirements of the Bayh-Dole Act.

- The NIH’s Rationale for Denial: The NIH has denied multiple petitions concerning Xtandi, first in 2016 and again more recently. Each time, the agency has reiterated its long-held position that drug pricing is not within the scope of the Bayh-Dole Act’s march-in provisions. In its 2023 denial, the NIH stated that the price of Xtandi, while high, had not been shown to be the cause of a broad lack of availability for patients who were prescribed the drug, citing manufacturer patient assistance programs [8]. They argued that the petitioners failed to demonstrate that marching in would be an effective remedy that wouldn’t cause more harm than good by disrupting the existing supply chain.

The Xtandi case refuses to fade away because it perfectly encapsulates the emotional and political core of the issue. It forces a direct confrontation with the question: Is it acceptable for American taxpayers to fund research and then pay the highest prices in the world for the resulting medicine? The NIH’s consistent “no” has, until recently, seemed like the final word.

The Core Controversy: Can March-In Rights Be Used to Control Drug Prices?

After four decades of consistent rejections, why is the debate over using march-in for price control more intense now than ever before? The answer lies in a confluence of mounting public anger, shifting political winds, and a new willingness by the current administration to challenge long-standing norms. The central controversy is a clash of two fundamentally different interpretations of the Bayh-Dole Act’s purpose and language.

The Argument FOR Using March-In Rights on Price

Advocates for using march-in as a price lever build their case on legal interpretation, legislative intent, and simple fairness.

“Reasonable Terms” and the Public Interest

The cornerstone of their argument is the phrase “available to the public on reasonable terms” within the definition of “practical application.” They argue that the word “reasonable” is meaningless if it doesn’t encompass price. As a legal term of art, “reasonable” almost always implies a consideration of cost and fairness. They point out that a product could be fully stocked in every pharmacy in the country, but if it costs a million dollars per dose, it is not meaningfully “available” to the public. Thus, an unreasonable price is a failure to achieve practical application, directly satisfying the first march-in trigger.

A Contested Legacy: What Did Bayh and Dole Intend?

The historical record on what the Act’s authors, Senators Bayh and Dole, intended regarding price is complex and contested. In a 2002 Washington Post op-ed, the two senators wrote an article that seemed to argue against using march-in for price controls, stating the Act “did not intend that government set prices on resulting products.” [9] This quote is frequently cited by the pharmaceutical industry.

However, proponents of price-based march-in point to other evidence. For example, they highlight a passage from the senators’ op-ed that states march-in rights are available if a company “has not taken steps to commercialize the invention or is not making it available to the public.” They argue an unaffordable price falls under the latter. Furthermore, they note that the original draft of the Bayh-Dole Act contained a “recoupment” provision, which would have required companies to pay back the government’s research investment. This provision was removed in favor of the march-in rights, suggesting that march-in was intended to be the primary mechanism for protecting the public’s financial interest.

Economic Justice and Taxpayer ROI

Beyond the legal arguments, there is a powerful moral and economic case to be made. Taxpayers are the initial investors in a huge proportion of biomedical research. The NIH alone has an annual budget of over $47 billion [10]. When that investment leads to a blockbuster drug, advocates argue, the public deserves a return on that investment, not in the form of direct payments, but in the form of affordable access. Allowing a company to charge American consumers multiples of what they charge consumers elsewhere is seen as a betrayal of the public trust and a perversion of the Bayh-Dole Act’s goals.

The Argument AGAINST Using March-In Rights on Price

The opposition, led by the pharmaceutical industry, university tech transfer associations, and venture capitalists, presents an equally forceful case centered on the catastrophic consequences they believe would follow the use of march-in for price control.

The “Chilling Effect” on Innovation and Investment

This is the single most powerful argument against price-based march-in. The entire biomedical innovation ecosystem is built on a high-risk, high-reward model. A company or investor might pour hundreds of millions of dollars into developing a university’s discovery, knowing that the vast majority of drugs fail in clinical trials. The sole reason they take this enormous risk is the promise of market exclusivity granted by a patent if the drug succeeds. This period of exclusivity allows them to recoup their investment and fund the next generation of research.

If the government can arbitrarily march in and set a “reasonable” price after the fact, this entire model collapses.

<blockquote>”The uncertainty created by the potential for the government to step in and seize intellectual property based on price would have a significant chilling effect on the willingness of private-sector partners to engage with federally supported research institutions. This would dismantle the very public-private partnerships that Bayh-Dole was designed to create, ultimately harming the pipeline of new medicines for patients.” — Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) [11]</blockquote>

The “chill” would be felt at every level:

- Venture Capitalists: Would be far less likely to fund early-stage biotech startups spun out of universities if the potential for future profits is capped by government intervention.

- Large Pharmaceutical Companies: Would be hesitant to license promising compounds from universities, fearing that their multi-billion dollar investment in Phase III trials and marketing could be undermined.

- Universities: Would find it much harder to find commercial partners for their inventions, potentially sending them back to the pre-Bayh-Dole era of discoveries languishing on the shelf.

Practical Hurdles: Who Sets the “Reasonable” Price?

Opponents also raise a critical practical question: if the government marches in, who decides what a “reasonable” price is? The NIH is an agency of scientists and grant administrators, not economists or pricing experts. The process of setting a price would be fraught with political pressure and legal challenges. Would the “reasonable” price be based on manufacturing cost? R&D investment? The value it provides to patients? International reference pricing? There is no clear standard, and the resulting uncertainty would be paralyzing for industry.

The NIH’s Consistent Stance

For over 20 years, the NIH—the agency with the most experience in this area—has consistently and explicitly rejected the idea that price is a trigger for march-in. They have done so under both Republican and Democratic administrations. They argue that Congress had ample opportunity to include language about price controls in the Bayh-Dole Act and chose not to. To reinterpret the law now, they contend, would be an overreach of executive authority and contrary to legislative intent.

The Biden Administration’s Shift: A New Framework

For decades, the debate was largely static, with the NIH’s position acting as an impenetrable wall. That all changed in late 2023. In December, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), under the Department of Commerce, released a “Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights.” [12]

This draft guidance represents the most significant potential shift in policy in the history of the Bayh-Dole Act. While it does not explicitly state “high prices will trigger march-in,” it cracks the door open in a way no previous policy has.

Key Changes in the Draft Framework:

- Price as a Factor: The framework explicitly lists the price of a product as a potential factor in determining whether the “practical application” trigger has been met. It asks agencies to consider whether the “price or other terms… are unreasonable,” leading to a situation where the benefits of the invention are not “available to the public.” This directly contradicts the NIH’s long-held position.

- Focus on the Entire Market: It suggests that agencies should not just look at whether a drug is available to those with good insurance but should also consider whether the price is creating a broader public health problem by, for example, straining hospital or state Medicaid budgets.

- Broadening “Health and Safety Needs”: The framework suggests that a high price could, in itself, create a “health or safety need” if it prevents patients from accessing a necessary medicine. This would link the pricing issue to the second trigger as well as the first.

The release of this framework sent shockwaves through the pharmaceutical industry and the university community. It signals that the executive branch is, for the first time, seriously considering using the threat of march-in as leverage in the fight against high drug prices. While the framework is still a draft and has not been finalized, it fundamentally changes the risk calculation for any company developing a product with federal funding.

Economic and Industry Impact: A Balancing Act

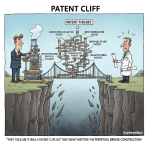

The theoretical and legal debate over march-in rights is fascinating, but for professionals in the pharmaceutical, biotech, and investment sectors, the practical economic consequences are what truly matter. The potential activation of march-in as a price control tool would not be a minor policy tweak; it would be an earthquake that reshapes the foundations of the industry’s business model.

The Pharmaceutical Industry’s Perspective

For research-based pharmaceutical companies, the current system, for all its public criticism, is built on a clear logic of risk and reward.

R&D Investment and Risk Mitigation

The journey of a drug from lab bench to pharmacy shelf is incredibly long, expensive, and fraught with failure. Estimates from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development place the pre-tax cost of developing a new prescription medicine at $2.6 billion, including the cost of the many failed candidates along the way [13]. Companies and their investors absorb these costs. The primary reward that justifies this staggering risk is the period of market exclusivity granted by a patent, which allows them to set a price that can recoup R&D costs, cover the costs of the failures, and generate a profit to fund future research.

From this perspective, march-in rights used for price control are an existential threat. It’s akin to changing the rules of a game after it has already been played. A company might spend a decade and billions of dollars on a drug, only to have the government declare its price “unreasonable” and effectively nullify its patent exclusivity. This introduces a level of sovereign risk that is nearly impossible to price into an investment model. The predictable result, industry leaders argue, would be a dramatic pullback in R&D investment, especially in high-risk areas like rare diseases or Alzheimer’s.

The Role of Universities and Tech Transfer Offices

Universities are the unsung heroes of the Bayh-Dole system. Their research provides the seeds of innovation, and their Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) are the matchmakers that connect academic discovery with commercial capital. They are caught squarely in the middle of the march-in debate.

On one hand, universities are mission-driven institutions dedicated to the public good. They are sensitive to the criticism that their research, funded by taxpayers, is leading to unaffordable products. On the other hand, the licensing revenue they receive from their patents is a vital source of funding that they reinvest into more research, creating a virtuous cycle. In FY 2022 alone, university tech transfer activities supported over 1,500 new startups and the creation of over 850 new commercial products [14].

The fear within the academic community is that the “chilling effect” would hit them first. If pharmaceutical companies and venture capitalists become wary of licensing university patents due to march-in risk, TTOs will find it impossible to commercialize their inventions. The flow of private capital that Bayh-Dole unlocked would slow to a trickle, and the “valley of death” that existed before 1980 could re-emerge. This would not only harm the universities’ finances but would also mean that fewer life-saving discoveries ever make it to patients—the exact opposite of the march-in proponents’ goals.

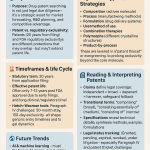

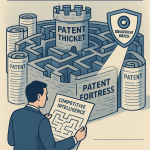

Competitive Intelligence and Patent Strategy: Navigating the New Risk

For business professionals operating in this new environment, waiting to see what happens is not a viable strategy. The heightened risk of march-in must be integrated into strategic planning, due diligence, and competitive intelligence efforts. This is where understanding the patent landscape becomes a critical defensive and offensive tool.

The first step in any risk mitigation strategy is identification. A company needs to know which patents in its own portfolio—or in the portfolio of a competitor or potential acquisition target—are encumbered by the Bayh-Dole Act. Any patent that arose from research funded, even in part, by a federal agency like the NIH, NSF, or Department of Defense carries this latent march-in risk.

This requires meticulous due diligence that goes beyond a simple patent search. It involves scrutinizing the “Government Interest Statement” or “Statement of Federally Sponsored Research” section of a patent filing, which discloses any federal funding. This process can be complex, as funding can be several steps removed from the final patent holder.

This is where specialized patent intelligence platforms become indispensable. For instance, a service like DrugPatentWatch provides comprehensive data on pharmaceuticals, including detailed patent information. Savvy strategists can use such a database to screen their own products, monitor competitors, and evaluate M&A targets specifically for the presence of government funding in their patent history. Identifying a competitor’s reliance on a key, federally-funded patent could become a new vector for competitive strategy, while discovering such a patent in a potential acquisition target’s portfolio would necessitate a significant adjustment to its valuation.

Armed with this knowledge, companies can develop proactive strategies:

- Risk-Adjusted Valuation: The valuation of a drug candidate with Bayh-Dole strings attached must be adjusted downward to account for potential price controls.

- Strategic Licensing: When licensing technology from a university, companies may seek more favorable terms or specific clauses that address the potential for a march-in action.

- Pricing Strategy: For products with federally-funded patents, companies may need to adopt more moderate pricing strategies from the outset to avoid attracting the attention of patient advocates and government agencies. Documenting the value proposition and cost-effectiveness of a drug becomes even more critical.

- Advocacy and Communication: Proactively communicating the value of a product and the company’s commitment to patient access through assistance programs can help build a defensive narrative against future march-in petitions.

In this new era, ignoring the federal funding history of a patent is no longer an option. It has become a key data point for assessing risk and opportunity across the entire biopharmaceutical landscape.

Global Implications and International Comparisons

The debate over march-in rights does not occur in a vacuum. It is deeply intertwined with global pharmaceutical markets, international trade law, and the ongoing competition between nations to be leaders in biopharmaceutical innovation.

Compulsory Licensing: The International Parallel

Many other countries have legal mechanisms similar in effect to march-in rights, most often referred to as compulsory licensing. A compulsory license is an authorization given by a government to a third party to make, use, or sell a patented product without the consent of the patent owner.

The World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) permits compulsory licensing under certain conditions, such as national emergencies, public health crises, or to remedy anti-competitive practices [15]. This tool has been used, or threatened to be used, by various countries, particularly developing nations, to gain access to essential medicines, most notably for HIV/AIDS and, more recently, for COVID-19 treatments.

While similar in outcome (breaking patent exclusivity), there is a key difference. Compulsory licensing is typically a broader power that a government can apply to any patent deemed essential, regardless of its funding source. March-in rights are narrower, applying only to the specific subset of inventions created with U.S. federal funding.

The international experience with compulsory licensing offers a potential preview of what could happen if the U.S. begins to use march-in for price control. Pharmaceutical companies often react to the threat of compulsory licensing by engaging in price negotiations or offering voluntary licenses on more favorable terms. However, they also argue that the widespread use of such tools erodes the intellectual property protections that are essential for global R&D.

Impact on U.S. Competitiveness

For decades, the United States has positioned itself as the gold standard for intellectual property protection and the world’s undisputed leader in biomedical innovation. The Bayh-Dole Act itself is often credited with creating this leadership position and has been copied by many other countries seeking to emulate America’s success in commercializing academic research.

Opponents of price-based march-in argue that activating this provision would tarnish the U.S.’s reputation and undermine its competitiveness. If the U.S. government begins to effectively set prices on its most innovative drugs, they contend, the global flow of investment capital for biotech could shift. Investors and multinational pharmaceutical companies might see more stable and predictable returns in other markets, like Europe or parts of Asia, that also have strong research bases but may offer a more consistent policy environment.

The irony, they argue, is that in an attempt to lower domestic drug prices, the U.S. could inadvertently drive the next generation of pharmaceutical innovation—and the high-paying jobs and economic growth that come with it—overseas.

The Future of March-In Rights: What’s Next?

The pharmaceutical world is holding its breath. The release of the NIST draft framework was a starting gun, and the race is now on to see how this new policy landscape will take shape. Several key developments will determine the future of march-in rights.

Finalization of the NIST Framework

The most immediate question is what the final version of the interagency guidance will look like. The draft was open for public comment, and it drew a torrent of feedback from all sides—patient advocates, industry groups, universities, and legal experts. The Biden administration will have to weigh these competing interests as it finalizes the framework.

- Scenario 1: The Framework is Finalized As-Is. If the final guidance largely resembles the draft, it will codify the administration’s new, more aggressive stance. This would send a clear signal to federal agencies that they have the green light to consider price as a factor in march-in petitions. We would likely see a new wave of petitions against high-priced drugs.

- Scenario 2: The Framework is Watered Down. Intense lobbying from the pharmaceutical industry and the academic community could lead to a final version that walks back some of the more controversial elements, perhaps re-emphasizing that price should only be a factor in extreme circumstances. This would be seen as a victory for the status quo.

- Scenario 3: The Framework is Withdrawn or Delayed. A change in administration or successful legal challenges could lead to the framework being shelved indefinitely, returning the policy environment to its pre-2023 state.

Potential for the First Successful March-In Petition

Regardless of the framework’s final form, the pressure to act will remain. It is highly probable that we will see new petitions filed, likely again targeting Xtandi or other high-profile, high-cost drugs with clear federal funding origins.

The key question is whether a federal agency—most likely the NIH or the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—will finally grant a petition. If this happens, it will be a watershed moment. The immediate result would be a massive legal battle, as the affected company would undoubtedly sue the government, arguing that the agency overstepped its statutory authority.

Legislative and Judicial Paths Forward

The fight over march-in rights may ultimately be decided not by agencies, but by courts or by Congress.

- The Judicial Path: A court case resulting from a granted march-in petition would eventually force the judiciary to rule on the core legal question: does the phrase “on reasonable terms” in the Bayh-Dole Act include price? A Supreme Court ruling on this issue would provide a definitive answer that has eluded policymakers for 40 years.

- The Legislative Path: Congress could intervene at any time. It could pass a new law to explicitly clarify the meaning of the Bayh-Dole Act. A law could either expressly forbid the use of march-in for price control, appeasing industry, or it could explicitly authorize it, siding with reformers. Given the current political polarization, such a clear legislative solution seems unlikely, but it remains a possibility.

Conclusion: A Tool of Last Resort or a Lever for Change?

The story of march-in rights is the story of a powerful idea lying dormant. For four decades, it has been a theoretical safeguard, a constitutional check on the power granted to private entities over taxpayer-funded science. It was intended to ensure that the ultimate goal of the Bayh-Dole Act—public benefit—was always served.

Today, the definition of “public benefit” is being fiercely debated in the arena of prescription drug prices. One side sees march-in rights as a dangerous weapon that, if used, would shatter the fragile ecosystem of innovation, leading to fewer new cures and treatments for everyone. They see it as a misguided attempt to apply a legal tool to a complex economic problem it was never designed to solve.

The other side sees march-in rights as a moral and legal obligation—a long-overlooked lever that can finally be pulled to restore balance to a system they believe has become tilted too far in favor of corporate profits at the expense of public health. They argue that a cure that is unaffordable is not a cure at all.

The truth is that march-in rights were likely never intended to be a primary, first-line mechanism for setting drug prices across the industry. They are, by design, a tool of last resort. However, the persistent refusal by every administration to even consider price as a relevant factor has led to the current moment of reckoning. The new draft framework from the Biden administration does not propose making march-in a common tool. Instead, it seeks to restore it as a credible threat, hoping that the mere possibility of its use will encourage manufacturers to self-regulate and moderate their pricing on taxpayer-funded drugs.

Can march-in rights really lower prescription drug costs? The answer is a qualified and complex “yes.” Directly, granting a march-in petition on a single drug could lower its price by introducing generic competition. Indirectly, and perhaps more powerfully, the credible threat of using march-in could create a new dynamic in the pharmaceutical market, forcing companies to factor this risk into their pricing strategies for any product touched by federal dollars.

The path forward is fraught with risk. A heavy-handed approach could indeed trigger the “chilling effect” that industry fears, harming the very innovation we seek to foster. But a complete refusal to consider the affordability of taxpayer-funded inventions risks further eroding public trust and leaving a powerful tool for public protection locked away forever. The challenge for policymakers, industry leaders, and advocates is to find a narrow path forward—one that uses the leverage of march-in rights to encourage fairness without destroying the engine of discovery. The stakes—for our health and our economy—could not be higher.

Key Takeaways

- Origin and Purpose: March-in rights were created by the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 as a safeguard to ensure that inventions developed with federal funding are properly developed and made available to the public.

- The Four Triggers: The government can only “march in” if one of four conditions is met: (1) failure to achieve practical application, (2) to alleviate health/safety needs, (3) to meet public use requirements, or (4) a breach of U.S. manufacturing rules.

- The Core Controversy: The central debate is whether a high price can be considered a failure to make a drug “available to the public on reasonable terms” (part of the “practical application” definition). Historically, the NIH has said no.

- Historical Precedent: No federal agency has ever granted a march-in petition. Major cases involving Norvir and Xtandi, which focused on price, were all denied on the grounds that Bayh-Dole was not intended as a price control tool.

- The “Chilling Effect”: The primary argument against using march-in for price is that it would deter private investment in developing university inventions, thus “chilling” innovation and harming the pipeline for new drugs.

- A Major Policy Shift: The Biden administration’s 2023 draft NIST framework proposes, for the first time, that an agency should consider a product’s price when evaluating a march-in petition, representing a significant departure from past policy.

- Strategic Imperative: Companies must now treat the federal funding history of a patent as a key risk factor. Using competitive intelligence tools like DrugPatentWatch to identify these patents is crucial for due diligence, valuation, and strategic planning.

- The Future is Uncertain: The final form of the NIST framework, coupled with potential legal challenges and new petitions, will determine whether march-in rights remain a dormant provision or become an active lever for influencing drug prices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is “marching in” the same as the government seizing a patent?

Not exactly. It’s more nuanced. Marching in doesn’t involve the government taking ownership of the patent (which is sometimes called “eminent domain for patents”). Instead, the government forces the patent holder to grant a license to a third party (like a generic drug maker). If the patent holder refuses, the government can grant the license itself. The original company still owns its patent, but it loses its exclusivity, which is the patent’s primary source of value.

2. Why has the government, specifically the NIH, been so reluctant to use march-in rights even for non-price reasons, like the Fabrazyme supply shortage?

The NIH’s reluctance stems from a combination of pragmatism and policy. In the Fabrazyme case, their analysis concluded that the march-in process would be too slow and bureaucratic to solve the immediate problem; the manufacturer was already taking faster steps to fix the supply chain. More broadly, agencies view march-in as a truly extraordinary remedy. They recognize that any use of this power, even for a seemingly clear-cut reason, sets a precedent that could destabilize the public-private partnerships fostered by the Bayh-Dole Act. They prefer to work collaboratively with licensees to solve problems before resorting to such a confrontational measure.

3. If the government marches in, does the original company get any compensation?

Yes, but the terms might not be favorable. The Bayh-Dole Act requires that the new license be granted on “reasonable terms.” This includes a “reasonable royalty” being paid to the original patent holder. However, the government and the courts would have significant say in determining what “reasonable” means in this context. It would almost certainly be far less than the profits the company would have made from its exclusive sales, reflecting the fact that the company failed to meet its obligations under the Act.

4. How does the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) drug price negotiation power interact with march-in rights?

This is a key area of evolving policy. The IRA gives Medicare the power to directly negotiate the price of certain high-cost drugs, but this power is limited to specific drugs that are many years past their initial FDA approval. March-in rights are different. They could theoretically be used much earlier in a drug’s life cycle and apply to any drug developed with federal funding, not just those selected for Medicare negotiation. The two tools could be seen as complementary: the IRA provides a structured, predictable process for older drugs, while march-in rights remain a potential “wild card” to address pricing issues on newer, taxpayer-funded drugs that fall outside the IRA’s scope. An administration could potentially use the threat of march-in to bring a company to the negotiation table even before it becomes eligible under the IRA.

5. If a company’s drug is based on 10 different patents, but only one minor, early-stage patent was from federally funded research, is the entire drug still subject to march-in?

This is a complex legal question that has not been fully tested. The march-in right applies to the “subject invention”—the specific invention created with federal funds. If that patent is essential to the final product (i.e., the product could not be made without infringing that patent), then the entire product is likely subject to march-in. However, if the federally funded patent covers something minor or easily engineered around, the case would be weaker. Companies often build a “patent thicket” around a product, and petitioners would have to prove that the specific government-funded patent is a necessary component whose unavailability is blocking public access on reasonable terms. This complexity is one reason why a successful march-in is so challenging.

References

[1] U.S. General Accounting Office. (1978). The Federal Government’s Role in Fostering University-Industry Cooperation.

[2] 35 U.S. Code § 201(f) – Definitions. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School.

[3] Knowledge Ecology International. (2021). Petition to the NIH to Exercise March-In Rights for the Prostate Cancer Drug Xtandi.

[4] NIH Office of Science Policy. (2010). Analysis of a Request for the U.S. Government to Exercise its “March-in” Rights under the Bayh-Dole Act for Fabrazyme®.

[5] Knowledge Ecology International. (2021). Analysis of NIH Waivers of the Domestic Manufacturing Requirement for Drugs.

[6] Varmus, H. (1997). Letter from NIH Director Harold Varmus to Johns Hopkins University and CellPro regarding the march-in petition.

[7] NIH Office of the Director. (2004). In the Case of National Institutes of Health, Determination on the Public Health Service’s Role in the Matter of Norvir.

[8] Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). HHS and Commerce Department Lay Out Path to Lower Drug Costs for Americans.

[9] Bayh, B., & Dole, B. (2002, April 11). Our Law Helps Patients Get New Cures. The Washington Post.

[10] National Institutes of Health. (2023). Budget of the National Institutes of Health.

[11] Biotechnology Innovation Organization. (2023). BIO Statement on NIST’s Draft March-In Framework.

[12] National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2023). Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights.

[13] DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20-33.

[14] Association of University Technology Managers. (2023). AUTM 2022 Licensing Activity Survey Highlights.

[15] World Trade Organization. (n.d.). TRIPS and pharmaceutical patents: Compulsory licensing.