The life sciences industry operates under a unique intellectual property (IP) paradigm where the nominal period of protection granted by statute is routinely eroded by the mandatory demands of regulatory review. For business development (BD) teams, IP counsel, and investors, the accurate determination of a drug’s effective market exclusivity—the time between commercial launch and the loss of exclusivity (LOE)—is arguably the most critical variable in valuation and strategic planning. This report provides an exhaustive, mechanistic analysis of the instruments available to innovators under U.S. and international law to compensate for this lost time, alongside strategic case studies demonstrating how market leaders successfully built multi-billion dollar patent fortresses.

I. The Foundational Framework: Defining Nominal and Effective Patent Life

Understanding how long a drug patent lasts requires differentiating between the statutory baseline and the commercial reality. The pharmaceutical lifecycle inherently compromises the theoretical maximum term, necessitating the complex corrective measures detailed within the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch-Waxman Act).

A. The 20-Year Baseline: Filing Date, Terminology, and Initial Deterrence

Under U.S. patent law, the nominal patent term is 20 years, beginning from the earliest effective filing date of the application (35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2)). This 20-year clock starts running long before the drug molecule completes clinical trials or receives marketing approval. For novel therapeutic candidates, the R&D and clinical phases typically consume five to ten years of this term. The precise moment of commercial jeopardy is the “Patent Cliff,” defined as the expiration of the last enforceable intellectual property right—either a patent or a regulatory exclusivity—that prevents generic or biosimilar entry.

The initial function of the patent grant is deterrence, creating a legal right to exclude others. However, a review of real-world outcomes suggests that the simplistic metric of patent volume can be misleading when assessing market longevity. Data tracking the time to generic entry for over one hundred top-selling drugs revealed that the number of patents protecting a brand-name drug has no statistically significant correlation with the effective patent life.1 For investors and BD professionals performing due diligence, this is a critical observation: focusing solely on a high patent count, outside of a deliberately complex patent thicket strategy, may offer a false sense of security. The true measure of longevity rests upon the quality and strategic timing of a few key patents, coupled with regulatory exclusivities.

The analysis confirms that proactive IP diligence must prioritize the strength of core claims (composition of matter, key polymorphic forms, or critical methods of use) and the integration of regulatory data exclusivity timelines, rather than simply totaling the volume of patents in the Orange Book. If a high patent count does not reliably predict the effective life of the product, R&D and IP teams must concentrate their competitive intelligence efforts not on mere quantity but on the quality of claims and the timing of regulatory exclusivities, as these barriers often dictate the actual Loss of Exclusivity (LOE) date.

B. Statutory Adjustment: Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)

Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) is a mechanism established by the American Inventors Protection Act of 1999 (AIPA) to compensate patent holders for time lost due to administrative delays caused by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) during the patent prosecution process.2 The total PTA is added day-for-day to the end of the patent’s 20-year nominal lifespan.2

Deconstructing A-Delay, B-Delay, and C-Delay: Mechanics and Pitfalls

The calculation of PTA involves three distinct components designed to ensure the patent term is not unduly shortened by the agency’s internal processes.3 Understanding the interplay of these components is essential for forecasting the precise expiration date.

- A-Delay (14-Month Delay): This compensates for the USPTO’s failure to provide an initial Office Action or Notice of Allowance within 14 months of the application filing date.2

- B-Delay (3-Year Delay): This compensates for the failure to issue the patent within three years of the actual filing date, provided that periods of delay attributable to the applicant are excluded from this calculation.3

- C-Delay (Administrative Delays): This addresses specific administrative delays, such as those caused by secrecy orders or interference proceedings.3

The total adjustment is calculated by totaling the B and C delays and then subtracting any overlapping delays caused by the applicant (Applicant-Related Delays or A-Delays).3 Applicant-related delays, such as late responses or requests for extensions, reduce the overall PTA granted.

The PTA determination indicated on the issued patent constitutes the official notification of the USPTO’s calculation under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b).4 Given the complexities, patent holders are advised to await the formal grant of the patent before determining whether a request for reconsideration of the calculation is warranted.4 While critical for maintaining the nominal 20-year guarantee, PTA is fundamentally reactive, aiming to offset internal agency delays. In contrast, Patent Term Extension (PTE), discussed in the following section, is a far more strategically significant mechanism for pharmaceutical companies, as it aims to restore time lost due to external, statutory requirements—namely, the lengthy FDA regulatory review process.

C. Reality Check: Nominal vs. Effective Patent Life Metrics

For pharmaceuticals, the effective patent life (EPL) is the commercially viable period during which the drug holds market exclusivity, typically beginning at FDA approval and ending at the onset of generic competition. Industry analysis consistently shows that the nominal 20-year term is rarely realized. A review of time to generic entry for leading drugs shows that the average effective patent life stands at approximately 13.35 years.1

This widely accepted statistic confirms that five to seven years of the 20-year nominal term are routinely consumed by necessary R&D, pre-clinical testing, and extensive clinical development followed by regulatory review. Furthermore, data suggest that patents and exclusivities added to the Orange Book after a drug’s market entry offer limited utility in genuinely extending the effective patent life.1 This highlights a crucial requirement for successful lifecycle management: a robust and encompassing IP strategy must be formulated and executed proactively during the early clinical phases, long before the molecule reaches the approval stage, and certainly not as a reactive measure post-launch. Failure to file preemptively means that any subsequent patents may be too narrow or too late to effectively deter sophisticated generic competitors targeting the earliest possible LOE date.

II. Regulatory Compensation: Patent Term Extension (PTE) under the Hatch-Waxman Act

The core mechanism for restoring the market exclusivity lost during mandatory clinical trials and regulatory review is the Patent Term Extension (PTE), authorized by the Hatch-Waxman Act. This compensatory measure can potentially add up to five years back onto the patent term, significantly impacting the drug’s commercial value.

A. The Rationale: Restoring Lost Time Due to FDA Review

The Hatch-Waxman Act, officially the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, served a dual purpose: facilitating generic competition through the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) process and compensating innovators for regulatory delays through PTE.5 PTE is specifically granted to offset the period during which a drug could not be commercially worked due to the statutory requirements for clinical trials and subsequent review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5

PTE can extend patent protection for a maximum of five years.6 However, there is a key limitation: the PTE cannot extend the patent term such that the effective term remaining after the FDA approval date exceeds 14 years.6 This restriction balances the public interest in timely generic access against the innovator’s need to recover development costs. The 14-year effective term rule often dictates the strategic importance of the timing of patent issuance relative to the IND effective date.

B. The PTE Calculation Engine: Deconstructing the Formula

The calculation of the PTE period is mechanistic and strictly governed by statute, involving four primary variables. The formula dictates the maximum allowable extension:

PTE=RRP–PGRRP–DD–21(TP–PGTP)

7

Detailed Component Analysis

- Regulatory Review Period (RRP): This is the foundation of the calculation, representing the total number of days lost to the regulatory process. It is measured from the Investigational New Drug (IND) effective date to the New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) approval date.7

- Pre-Grant Regulatory Review Period (PGRRP): This variable accounts for the number of days within the RRP that occurred before the patent was actually issued.7 This period is subtracted from the total RRP because the nominal 20-year patent clock was already running, meaning the time was not truly “lost” from the patent’s perspective.

- Testing Phase (TP) Factor: The formula generally aims to restore only half of the time spent in the testing phase. TP is the total number of days from the IND effective date to the NDA/BLA submission date.7 The term 1/2(TP–PGTP) represents the non-compensable portion of the testing time.

- Due Diligence (DD): This variable represents the number of days during the RRP when the applicant failed to act with due diligence.7 While typically zero in the initial calculation, the existence of this variable forms the basis of critical strategic risk via third-party challenges.

Strategic Insight: The Weight of Diligence and Third-Party Risk

The PTE process is not purely administrative. Once a PTE application is filed with the USPTO and forwarded to the FDA, the FDA calculates the RRP and publishes its determination in the Federal Register.7 This publication is the critical trigger for competitive intelligence and litigation teams. It initiates a 180-day window during which “any person” may file a “due diligence petition” with the FDA.7

This statutory window transforms the PTE calculation into a high-stakes litigation risk. Competitors—specifically generic or biosimilar applicants—actively monitor these filings, seeking any evidence that the originator failed to pursue the clinical development or regulatory approval process with sufficient diligence. The petition must allege that the applicant failed to act with due diligence during a specific part of the RRP and must include sufficient facts to warrant an investigation.7 A successful challenge, resulting in the reduction of the PTE period by even a few months, can translate into hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars in accelerated generic sales. This necessitates meticulous, auditable record-keeping of all R&D and clinical milestones to successfully defend against such challenges.

The following table summarizes the mechanistic complexity of the PTE calculation for IP counsel.

Patent Term Extension (PTE) Calculation Summary

| PTE Component | Formula Element | Description | Strategic Implication |

| Regulatory Review Period | RRP | Total time from IND effective date to NDA/BLA approval date. | Defines the total regulatory time lost.7 |

| Pre-Grant RRP | PGRRP | RRP period occurring before the patent was granted. | Time already counted against the 20-year term; subtracted from RRP.7 |

| Testing Phase Factor | 21(TP–PGTP) | Half of the period spent testing the product (IND to NDA/BLA submission). | Highlights that regulatory testing time is only partially restored.7 |

| Due Diligence Delay | DD | Time applicant failed to act diligently during RRP. | Subject to the 180-day third-party challenge window; critical due diligence risk.7 |

| Statutory Maximum | N/A | Total PTE cannot exceed five years. | Forces strategic prioritization if RRP exceeds the maximum restorative period.6 |

C. Interplay with Terminal Disclaimers: Legal Precedent

A common strategy in IP lifecycle management involves filing secondary patents that claim obvious variations of the core molecule or method. To overcome obviousness rejections from the USPTO, innovators frequently employ terminal disclaimers (TDs), agreeing that the secondary patent will expire concurrently with the primary, original patent.8 A significant legal question arose concerning whether a patent subject to a TD was still eligible to receive a Hatch-Waxman PTE.

The Federal Circuit addressed this interplay in the case of Merck & Co., Inc. v. Hi-Tech Laboratories, Inc. The court affirmed that PTEs could, and indeed should, be applied to terminally disclaimed patents.9 This ruling preserved Merck’s Hatch-Waxman extension for its patent covering Trusopt®.

This precedent is strategically vital for innovators. It confirms that a company can utilize TDs to build a robust, immediate patent barrier—a tactic critical to strategies like the Humira patent thicket, where hundreds of TDs were used 8—without sacrificing the potential to maximize the overall term longevity via the PTE mechanism. The ruling ensures that the tactical use of TDs to accelerate patent grant and secure a broader portfolio does not automatically foreclose the valuable compensatory relief offered by PTE.

III. The Regulatory Safety Net: FDA Data and Market Exclusivities

Beyond patent rights, the FDA grants various periods of regulatory market exclusivity that often serve as the earliest, and sometimes the most robust, statutory barrier to generic entry. These exclusivities run concurrently with any patent term but frequently dictate the commercial LOE date.

A. New Chemical Entity Exclusivity (NCE): The 5-Year Block

New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity grants five years of market protection to a drug that contains no active moiety that has been previously approved by the FDA.10 This is a powerful form of exclusivity under the Hatch-Waxman framework.5

Defining New Active Moiety and Scope

NCE eligibility hinges on whether the active moiety is genuinely new—meaning it was not previously approved in any other application under section 505(b) of the Act.11 It is important to note that a simple salt of an approved drug is generally not considered a new active moiety and thus would not qualify for NCE.11 The exclusivity applies broadly to all dosage forms containing the active moiety, regardless of the application owner.11 For example, when Farxiga (Dapagliflozin Tablets) was approved, it received NCE exclusivity. A later fixed-combination product (Xigduo XR), which contained Dapagliflozin, also benefited from this exclusivity, which ran concurrently and expired on the same date as the original NCE term.11

The NCE-1 Submission Window: A Critical CI Trigger

The 5-year NCE exclusivity generally blocks the FDA’s acceptance of an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) or a 505(b)(2) application seeking approval of a drug product containing the same active moiety.11 However, there is a crucial strategic exception: if the NDA holder has listed patents in the Orange Book, an ANDA or 505(b)(2) applicant can submit their application with a Paragraph IV certification one year early, at the “NCE – 1” date (Year 4).11

This NCE-1 date is the primary trigger point for generic R&D and competitive planning. It allows generic manufacturers to file their applications and begin the lengthy FDA review and patent litigation (Paragraph IV challenges) process a full year ahead of the NCE expiration. If their patent challenge is successful, this year of preparation enables them to launch immediately upon the NCE expiration date, maximizing the speed of market entry and return on investment.

B. Targeted Incentives: 3-Year, 7-Year, and GAIN Exclusivities

Beyond NCE, the FDA provides specific exclusivities designed to incentivize certain types of research or address particular public health needs.10

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity (3 Years): This is granted for new clinical studies, not tied to an NCE, that are deemed essential for the approval of a new use of an existing drug (e.g., a new indication, a novel dosage form, or a refined dosing regimen).10 This exclusivity is narrower than NCE, only prohibiting subsequent applicants from relying on the specific clinical data used for the approval, rather than blocking the molecule entirely.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) (7 Years): This is a powerful incentive granted under the Orphan Drug Act for drugs intended to treat rare diseases or conditions.10 As detailed later, this exclusivity is particularly relevant for advanced therapies like Cell and Gene Therapies (CGTs).

- Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Exclusivity: This provides an additional five years added to certain existing exclusivities for Qualified Infectious Disease Products (QIDPs).10

C. The Financial Leverage of Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) (6 Months)

Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) is one of the most financially impactful IP rights granted by the FDA. It provides an additional six months added to all existing patents and exclusivities (NCE, ODE, 3-year exclusivity) if the sponsor successfully completes required pediatric studies as mandated by the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA).10

Quantification of Return on Investment (ROI)

The six-month extension often provides a disproportionately high financial return because it is applied when the drug is already a mature, high-revenue blockbuster operating at peak profitability. The calculation for financial impact is straightforward:

Financial Impact of Pediatric Exclusivity=(Estimated Monthly Revenue)×6

12

For example, if a major blockbuster drug generates $50 million per month in revenue, the six-month pediatric extension provides an estimated financial benefit of $300 million.12 This substantial, guaranteed period of monopoly revenue makes the investment in pediatric studies, despite their cost and complexity, a non-negotiable component of late-stage lifecycle management for any drug projected to reach blockbuster status. It represents a vital, high-ROI mechanism for maximizing the commercial lifespan immediately prior to the patent cliff.

The following table summarizes the primary U.S. regulatory exclusivity mechanisms.

U.S. Regulatory Exclusivity Mechanisms Summary

| Type | Statutory Duration | Qualifying Criteria | Scope of Protection (Blocking Action) |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) | 5 Years | Drug contains no previously approved active moiety | Blocks submission of ANDA/505(b)(2) for 5 years (unless PIV filed at Year 4) 10 |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) | 7 Years | Drug for a rare disease/condition (prevalent in CGT) | Blocks approval of subsequent application for the same drug/same use 10 |

| New Clinical Investigation | 3 Years | New clinical studies essential for approval (e.g., new indication/dosage) | Blocks approval of ANDA/505(b)(2) relying on those studies 10 |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) | 6 Months (Add-on) | Completion of required pediatric studies (PREA) | Adds 6 months to existing patents and exclusivities 10 |

IV. Global Longevity: International Term Extension Mechanisms

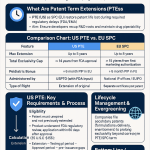

Pharmaceutical products are global assets, requiring IP strategies tailored to the specific mechanisms and limitations of major international markets. The systems in the European Union (EU), Canada, and Japan offer analogous compensatory relief but with crucial differences in scope and duration compared to the U.S. PTE.

A. The European Union (EU) Model: Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs)

In the EU, innovators utilize Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) to extend protection beyond the patent expiration date, compensating for time lost during regulatory approval.6 SPCs provide a maximum extension of five years, depending directly on the duration of the regulatory approval process.6

Critical Distinction in Scope

A fundamental difference exists between the U.S. PTE and the EU SPC regarding the breadth of protection. The U.S. PTE generally applies broadly to all aspects of the patented invention.6 In contrast, an SPC is specific to the pharmaceutical and plant protection products and covers only the active ingredient or combination of active ingredients specified in the corresponding marketing authorization.6

This distinction has significant ramifications for global IP strategy. Secondary patents covering manufacturing processes, purification methods, or novel formulations, which are critical components of a lifecycle management strategy, are more easily extended via the broad U.S. PTE mechanism. In the EU, however, these process or formulation patents may require independent enforcement, as they might not be covered by the product-specific SPC. Global IP layering must therefore account for these distinct regional scopes of protection.

B. North American Comparison: Canada’s Certificate of Supplementary Protection (CSP)

Canada introduced the Certificate of Supplementary Protection (CSP) regulations to provide a limited form of patent term extension for new pharmaceutical products protected by an eligible patent.14 A CSP offers a maximum of 24 months (two years) of additional protection after the expiration of the patent for a drug containing a new medicinal ingredient or combination thereof.14

The CSP regime requires that the application be filed promptly: before the end of the 120-day period beginning on the day the Notice of Compliance (NOC) is issued (or the day the patent is granted, if later).14 Furthermore, the CSP Regulations impose a global harmonization requirement, demanding that to obtain the benefit of a CSP, the marketing application must have been filed within a specific time limit (12 or 24 months) if an application for marketing was also filed in key jurisdictions, including the EU, the United States, or Japan.14

C. Asian Powerhouse: Japan’s Patent Term Extension System

Japan also operates a system for Patent Term Extension (PTE) designed to compensate patent holders for market time lost while awaiting government approval.15 The patent term can be extended by a maximum of five years.15

The length of the extension corresponds to the period during which the patented invention “could not be worked” due to the requirement for regulatory approval.15 This period starts on the later of the day the clinical trial (IND) is filed or the day the patent is registered (granted), and it ends the day before the regulatory approval is mailed to the applicant.15 Japan’s system includes a complex calculation methodology that uses a “reference date”—the later of five years after filing or three years after the request for examination—to determine the maximum permissible extension.16 This demonstrates a structured approach to balancing the 20-year term against the mandatory regulatory timeline.

The table below provides a comparative summary of the major global IP restoration mechanisms.

Global IP Restoration Comparison

| Jurisdiction | Mechanism | Maximum Extension Duration | Scope of Protection |

| United States | Patent Term Extension (PTE) | 5 Years | Broadly applies to all aspects of the patented invention.6 |

| European Union | Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) | 5 Years | Specific to the active ingredient/combination in the marketing authorization.6 |

| Canada | Certificate of Supplementary Protection (CSP) | 24 Months | Limited extension for new medicinal ingredients.14 |

| Japan | Patent Term Extension (PTE) | 5 Years | Compensates for period invention could not be worked due to regulation.15 |

V. Strategic IP Lifecycle Management (LCM): Building the Patent Fortress

The implementation of term extension mechanisms and regulatory exclusivities must be viewed within the broader context of strategic IP lifecycle management (LCM). The goal of LCM is to maximize the commercial lifespan of a blockbuster drug by creating a robust, multi-layered IP defense—a “patent fortress”—that utilizes both scientific distinction and procedural barriers.8

A. Economic Drivers of Extension: The Multi-Billion Dollar Cliff

LCM strategies are fundamentally driven by the enormous economic value concentrated in the final years of a monopoly. Pharmaceutical companies deploy extensive legal and scientific resources to maximize commercial longevity because the consequences of the patent cliff are financially catastrophic. The anticipated loss of exclusivity (LOE) for Pfizer’s Lipitor, for example, was predicted by analysts to result in an 87% reduction in U.S. sales in the year immediately following the expiration of its core patents.8

This financial exposure compels innovators to develop complex, aggressive, and legally sophisticated tactics designed to maintain exclusivity for as long as possible.8 The strategies deployed by market leaders illustrate two distinct but equally potent models for achieving maximum commercial duration.

B. Case Study Deep Dive: Pfizer’s Lipitor (Atorvastatin)—Layered Secondary Defense (LCM 1.0)

Pfizer’s strategy for Lipitor (atorvastatin) is considered the foundational case study in modern pharmaceutical LCM. It exemplifies a layered secondary patents approach, combining preemptive scientific patenting, a broad portfolio of subsequent IP, and aggressive litigation to defend a generational asset.8

Preemptive Scientific Patenting: The Enantiomer Play

The critical success factor in Lipitor’s defense was the strategic use of scientific distinction. The initial composition of matter patent covered a broad class of compounds, including the racemic mixture of atorvastatin (a 50:50 combination of its two enantiomers).8 The pivotally important move was the later filing, well in advance of FDA approval, of a subsequent patent that specifically claimed the single, biologically active enantiomer—the calcium salt form—which is the precise molecule utilized in the marketed drug.8 This created a scientific justification for a second, later-expiring patent wall.

Secondary Patent Layering and Litigation

The Lipitor playbook involved the systematic layering of distinct secondary patents covering elements beyond the initial molecule, such as the specific crystalline form, formulations, and manufacturing processes.8 This qualitative layering ensures that even if one patent is invalidated, others remain. The strategy also relied heavily on litigation and settlement. For instance, a high-profile settlement with Ranbaxy in 2008 resulted in a delayed generic launch date until November 30, 2011, effectively purchasing several critical years of monopoly sales.8

The cumulative sales generated by Lipitor exceeded $130 billion over its lifetime, with the layered strategy successfully extending its exclusivity by several critical years beyond the original term of the core patent.8

C. Case Study Deep Dive: AbbVie’s Humira (Adalimumab)—The High-Volume Patent Thicket (LCM 2.0)

If Lipitor set the standard for qualitative defense, AbbVie’s approach for Humira (adalimumab) represents the archetype of the modern patent fortress: the “patent thicket”.8 This strategy moved beyond a portfolio of distinct patents to the construction of a vast, dense, and overlapping web of intellectual property rights.8 The core objective was economic attrition, making the cost and complexity of market entry prohibitively high for biosimilar competitors.

Massive Portfolio Scale and Creation Mechanism

Humira’s foundational composition of matter patent expired at the end of 2016. However, AbbVie amassed a staggering portfolio of at least 132 to 136 granted U.S. patents related to the drug.8 This represented a “brute force” methodology for building a barrier.8

The volume was achieved primarily through the aggressive filing of Continuation Applications, deriving the over 130 subsequent patents from only about 20 original “root” applications.8 A critical tactical detail is the timing: a remarkable 90% of these patents were issued in 2014 or later, demonstrating a calculated, late-stage effort to build the wall just as the expiration of the primary patent loomed.8 Furthermore, estimates suggest that as much as 80% of this patent estate was duplicative in nature, covering incremental aspects such as new, citrate-free formulations, methods of treatment for new conditions, and manufacturing nuances.8

Strategic Use of Terminal Disclaimers and Economic Attrition

To facilitate the rapid prosecution of these incremental claims and overcome potential obviousness rejections, AbbVie extensively utilized terminal disclaimers (TDs)—436 TDs were employed.8 As established in Section II.C, TDs ensure the later-filed patent expires with the parent, but they are crucial because they still create a legal hurdle that must be overcome by competitors.

The sheer number of patents created a massive economic barrier for biosimilar companies. The average cost to challenge a single patent via a proceeding like an inter partes review (IPR) is estimated at $774,000.8 Challenging 130+ patents, therefore, imposes a prohibitively expensive litigation cost that few companies can absorb simultaneously. This financial burden forced biosimilar developers into lengthy, confidential settlements designed to stagger their market entry over several years, effectively buying AbbVie sustained revenue.

Humira achieved peak annual sales exceeding $20.7 billion in 2021 alone.8 The thicket strategy successfully resulted in delayed U.S. biosimilar entry by several years past the core patent expiration date, preserving billions in revenue.

Volume vs. Effective Life: Reconciling the Data

The Humira case provides a powerful counter-example to the general statistical finding that patent count has no correlation with effective life.1 While a simple, uncoordinated collection of many patents does not extend longevity, the Humira experience demonstrates that when patent volume is deployed strategically—through timed continuation filings, use of TDs, and creating deliberately overlapping claims—it creates a procedural barrier that dictates commercial outcomes by delaying market access, thereby effectively prolonging market exclusivity. This approach converts legal procedure into economic reality.

The comparison of these two models illustrates the evolving nature of pharmaceutical IP defense.

Comparison of Strategic IP Fortification Methods

| Strategy | Primary Case Study | Mechanism of Extension | Goal & Metric | Key Tactical Tool |

| Layered Secondary Defense (LCM 1.0) | Lipitor (Atorvastatin) | Scientifically distinct follow-up patents (enantiomer, crystalline form, methods). | Maximize qualitative strength and legal defensibility. Resulted in cumulative sales > $130B.8 | Preemptive patenting of the active enantiomer; aggressive litigation.8 |

| High-Volume Patent Thicket (LCM 2.0) | Humira (Adalimumab) | Over 130 overlapping, incremental patents via continuation applications. | Create overwhelming economic and litigation cost barriers (attrition). Resulted in $20.7B peak annual sales.8 | Extensive use of Continuation Applications and Terminal Disclaimers (436 utilized).8 |

VI. Biologics and the Future: IP Duration in the BPCIA Era

The IP landscape for large-molecule biologics and advanced therapies (Cell and Gene Therapies, or CGT) presents unique challenges that shift the balance of protection away from traditional small-molecule patents and toward data exclusivity and process trade secrets.

A. The BPCIA Pathway: Data Exclusivity as the Primary Barrier

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), signed into law in 2010, established an abbreviated pathway for the FDA approval of biosimilar products.17 Much like the Hatch-Waxman Act, the BPCIA seeks to balance innovation incentives with market competition.

The 12-Year Biologic Data Exclusivity

For biologics, the most robust and immediate regulatory barrier is the 12-year biologic data exclusivity.13 This provision prohibits biosimilar applicants from relying on the originator’s clinical data for a full 12 years following the date of initial approval.13 Given the extremely high cost and complexity of independently replicating the clinical trials for a biologic, this 12-year window often provides a more stable and predictable period of market protection than the patent portfolio alone.

The BPCIA also established a detailed, highly formalized process for patent litigation between the innovator and the biosimilar applicant, commonly referred to as the “Patent Dance,” which governs the exchange of patent lists and the initiation of infringement suits.17

B. The Unique IP Challenges of Biologics and Advanced Therapies

Biologics are fundamentally different from small-molecule drugs. They are massive, complex molecules, typically consisting of proteins produced by living human, animal, or microorganism cells, often containing up to 50,000 atoms.17 They must be characterized not just by a simple chemical formula but by their amino acid sequence, intricate 3D structure, and post-translational modifications, such as glycosylation.18

IP Shift to Process and Know-How

This inherent complexity makes securing broad, definitive composition-of-matter patent claims challenging because replication, even if intended to be biosimilar, may involve slightly different manufacturing processes leading to variations in the final product. As a result, IP strategy for biologics shifts focus:

- Process Patents: Protection heavily relies on patents covering manufacturing processes, cell lines, purification methods, and specific formulations.18

- Trade Secrets: For advanced therapeutic products, particularly Cell and Gene Therapies (CGT), trade secrets covering the proprietary process and essential know-how are critical.13 Producing a consistent, clinical-grade therapeutic product requires complex, proprietary knowledge that cannot always be claimed effectively through patents alone. Even if competitors can design around existing patents, they may still find the IP environment extremely difficult to navigate due to the volume of trade secrets involved.13

C. Cell and Gene Therapy (CGT): IP Concentration in Orphan Diseases

Cell and Gene Therapies represent the cutting edge of medicine, involving modifying a patient’s cells or delivering genetic material to treat disease.18 Successful development of CGT products necessitates enormous financial resources, requiring multiple rounds of fundraising, collaboration, or acquisition by large pharmaceutical companies.19 The ability to attract this investment relies entirely on securing the best possible IP protection.19

An observation about the current CGT landscape is the dominance of Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE). All approved gene therapies thus far address diseases or conditions that meet the definition of rare diseases.13 This means that the 7-year Orphan Drug Exclusivity often serves as a primary regulatory shield for these cutting-edge assets, running alongside the 12-year biologic data exclusivity.13 Given the challenges in securing broad patent claims that can block all potential design-arounds for these complex systems, regulatory exclusivity proves to be a critical component of CGT longevity protection.13

VII. Competitive Intelligence and Financial Modeling: Predicting the Cliff

For IP, R&D, and BD teams, simply understanding the legal statutes is insufficient; actionable intelligence requires integrating technical patent data with clinical and commercial timelines to accurately predict the effective date of Loss of Exclusivity (LOE). This predictive capability is non-negotiable for investment decisions, pipeline prioritization, and generic/biosimilar launch planning.

A. Leveraging Integrated Data Platforms for Predictive Analysis

Analyzing a competitor’s strategic posture—including their global patent estate, prosecution history, and regulatory milestones—demands advanced tools. Integrated data platforms are designed to aggregate, clean, and connect information from hundreds of global sources, transforming raw data into user-friendly, searchable formats.20

The specialized nature of pharmaceutical competitive intelligence (CI) platforms, such as DrugPatentWatch, provides the most direct path to actionable insights for the industry.20 These platforms bridge the gap between complex legal documents and strategic business decisions by offering curated, high-value information:

- Comprehensive Drug-to-Patent Linkage: They meticulously map patents to specific approved drugs and pipeline candidates, solving the labor-intensive problem of determining which patents among a competitor’s hundreds actually protect their core asset.20

- Consolidated Exclusivity and Expiration Timelines: They provide unified timelines that integrate patent expirations (including PTA and PTE), regulatory exclusivities (NCE, ODE), and pediatric extensions.20 This consolidated data forms the core information required for accurate LOE prediction.

Speed to insight is widely recognized as a critical competitive advantage in the pharmaceutical sector.20 Integrated data platforms convert what would otherwise be a months-long manual effort into a dynamic, ongoing strategic function, allowing teams to quickly parse complex IP details, assess litigation risk, and inform M&A valuation.20

B. Benchmarking and Risk Assessment

Competitive intelligence is future-focused, providing a predictive approach to analyzing a competitor’s future moves, including their R&D strategy, specific product development pathways, and business development priorities.21

By actively benchmarking competitor portfolios and strategies—including examining prosecution histories and comparing claims—companies can optimize their own development paths. Furthermore, CI helps in tracking industry failures, which prevents pharma companies from duplicating errors in drug development and consequently saves precious resources.21 This dynamic analysis is crucial for both innovators seeking to reinforce their fortresses and generic companies seeking the precise coordinates of the patent cliff.

C. Calculating Real-World ROI and Valuation

For financial and business development teams, IP analysis translates directly into valuation. The critical metric to employ is the Effective Patent Life, which, as demonstrated, averages around 13.35 years for top-selling molecules.1 Any strategy aimed at pushing that EPL beyond the mean represents significant value creation.

The financial leverage of extensions, such as the six-month pediatric exclusivity generating hundreds of millions in revenue 12, underscores the importance of accurately modeling the value of every additional day of exclusivity. This granular financial modeling must integrate all variables—PTA, PTE, NCE, ODE, and PED—to provide a reliable forecast for investor relations and internal prioritization of R&D investments.

VIII. Conclusions and Actionable Recommendations

The effective duration of a pharmaceutical patent is a sophisticated calculation governed by the confluence of patent prosecution dynamics (PTA), regulatory compensation mechanisms (PTE), and application-specific exclusivities (NCE, ODE). The statistical reality that the effective life averages only 13.35 years demands a proactive, multi-layered defense strategy.

For innovators seeking to maximize exclusivity, the following strategies are evidenced as effective:

- Proactive and Precise Patenting: Adopt the layered defense model of Lipitor by securing strong, scientifically distinct secondary patents (e.g., enantiomers, crystalline forms, or specific formulations) early in development, ensuring these claims can withstand litigation and potentially qualify for term extension. Subsequent patents filed after market entry offer limited real-world extension benefits.1

- Meticulous Due Diligence Record-Keeping: Recognize that the PTE process is vulnerable to third-party challenges regarding diligence during regulatory review.7 Maintain exhaustive, verifiable records of every R&D and regulatory milestone to successfully defend against petitions that seek to reduce the compensatory PTE period.

- Strategic Deployment of Volume (The Thicket): If warranted by the asset’s commercial projection (Humira model), employ high-volume continuation applications and terminal disclaimers to create a dense, overlapping portfolio. The goal here is economic deterrence, forcing competitors into costly, multi-patent challenges that delay market entry, even if the patents themselves are incremental.8

- Prioritize Pediatric Studies: Treat the Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) as a high-ROI investment. The six-month extension guarantees a critical final period of monopoly revenue, potentially generating hundreds of millions of dollars in highly profitable sales.12

- Utilize Integrated Competitive Intelligence: Invest in specialized platforms that consolidate global patent, exclusivity, and clinical data. This enables R&D, IP, and BD teams to quickly identify the true LOE date, map competitor thicket strategies, and optimize the timing of their own lifecycle management interventions, recognizing that speed to insight is a primary competitive advantage.20

The longevity of a pharmaceutical asset is not determined by its initial 20-year grant, but by the strategic defense, meticulous documentation, and sophisticated interplay between patent law and regulatory exclusivity rules. Mastery of these mechanisms is essential for maintaining valuation and securing long-term market dominance.

Works cited

- Pharmaceutical “Nominal Patent Life” Versus “Effective Patent Life,” Revisited, accessed October 9, 2025, https://cip2.gmu.edu/2024/05/20/pharmaceutical-nominal-patent-life-versus-effective-patent-life-revisited/

- Patent Term Adjustment Data August 2025 – USPTO, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/dashboard/patents/patent-term-adjustment-new.html

- PTA Calculation: How to Calculate Patent Term Adjustment – Patent Paralegal Force, accessed October 9, 2025, https://patentparalegalforce.com/pta-calculation-how-to-calculate-patent-term-adjustment/

- 2733-Patent Term Adjustment Determination – USPTO, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2733.html

- The Hatch-Waxman Act | Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle LLP, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.curtis.com/glossary/intellectual-property/hatch-waxman-act

- What is the difference between a supplementary protection certificate (SPC) and a patent term extension (PTE)?, accessed October 9, 2025, https://wysebridge.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-supplementary-protection-certificate-spc-and-a-patent-term-extension-pte

- The Billion-Dollar Equation: Mastering Patent Term Extension to …, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/calculating-the-regulatory-review-period-for-patent-term-extension/

- Deconstructing Lifecycle Management and Filing Strategies of …, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/deconstructing-lifecycle-management-and-filing-strategies-of-pharmaceutical-blockbusters/

- Merck & Co., Inc. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co., Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2007) – Patent Docs, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.patentdocs.org/2007/03/merck_co_inc_v_.html

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- Exclusivity–Which one is for me? | FDA, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/135234/download

- Pediatric Exclusivity and Extensions – Umbrex, accessed October 9, 2025, https://umbrex.com/resources/industry-analyses/how-to-analyze-a-pharmaceutical-company/pediatric-exclusivity-and-extensions/

- Introducing biosimilar competition for cell and gene therapy products – PMC, accessed October 9, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11247524/

- Patent Linkage and Term Extension in Canada – Smart & Biggar, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.smartbiggar.ca/patent-linkage-and-term-extension-in-canada

- Overview of the Patent Term Extension in Japan – KAWAGUTI & PARTNERS, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.kawaguti.gr.jp/aboutlaw/jp_practices/01_1.html

- Part IX Extension of Patent Term, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.jpo.go.jp/e/system/laws/rule/guideline/patent/handbook_shinsa/document/index/09_e.pdf

- Biologics, Biosimilars and Patents: – I-MAK, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Biologics-Biosimilars-Guide_IMAK.pdf

- Cracking the Biosimilar Code: A Deep Dive into Effective IP Strategies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/cracking-the-biosimilar-code-a-deep-dive-into-effective-ip-strategies/

- IP priorities for forward-looking cell and gene therapy businesses – Mewburn Ellis, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.mewburn.com/news-insights/ip-priorities-for-forward-looking-cell-and-gene-therapy-businesses

- The High-Stakes Game of Pharma IP: Why Benchmarking Your Pipeline is Non-Negotiable, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-high-stakes-game-of-pharma-ip-why-benchmarking-your-pipeline-is-non-negotiable/

- Role of Competitive Intelligence in Pharma and Healthcare Sector – DelveInsight, accessed October 9, 2025, https://www.delveinsight.com/blog/competitive-intelligence-in-healthcare-sector