In the high-stakes world of pharmaceuticals, the rules of the game seem straightforward. A company invests billions of dollars and over a decade of research to bring a new drug to market. In return, it is granted a period of market monopoly, protected by patents and regulatory exclusivities, to recoup its investment and turn a profit.2 When these protections expire, the floodgates are meant to open. Generic competitors, having reverse-engineered the drug and proven it works the same way, enter the market. Competition ignites, prices plummet, and access to medicine expands. This is the bedrock principle of the modern pharmaceutical ecosystem, a cycle that has saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $2.4 trillion over the last decade and now sees generics account for over 90% of all prescriptions filled.4

But what happens when the floodgates remain shut? What if, long after the last patent has expired and the final exclusivity has lapsed, a drug faces no competition at all? This is not a hypothetical scenario. It is a peculiar and increasingly consequential paradox of the pharmaceutical landscape: the existence of drugs with no patents and no competition. These are often older, essential medicines that exist in a kind of commercial limbo—a state of perpetual, uncontested monopoly. This isn’t just a market anomaly; it’s a predictable outcome driven by a powerful confluence of economic, technical, and strategic forces.

The scale of this issue is significant enough that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now maintains and regularly publishes a formal list of off-patent, off-exclusivity drugs that have no approved generic competitor.8 The very existence of this list transforms the phenomenon from an anecdotal curiosity for industry analysts into a recognized, systemic market failure. It is a direct acknowledgment from the primary regulatory body that the blueprint for competition has broken down for hundreds of products. This is not a story about a few outliers; it is about a distinct category of medicines for which the market has failed to produce the affordable alternatives that patients and payers depend on.

Understanding why this happens is more than an academic exercise. For pharmaceutical executives, business development teams, and healthcare policymakers, it is a critical strategic imperative. It reveals deep truths about the real-world economics of drug development, the hidden complexities of manufacturing, and the sophisticated strategies used to manipulate the system. It explains why the price of a 60-year-old drug can suddenly skyrocket by 5,000% and why essential medicines can vanish from pharmacy shelves without warning.

This report will deconstruct this paradox from the ground up. We will begin by laying out the blueprint for how competition is supposed to work, from the first patent filing to the launch of multiple generics. Next, we will systematically dismantle the reasons why this blueprint so often fails, exploring the economic walls, manufacturing gauntlets, and strategic obstacles that prevent competition from taking root. We will then examine the severe consequences of these uncontested markets, using the infamous case of Daraprim as a lens and exploring the broader impacts of price gouging and drug shortages. Finally, we will turn to the future, analyzing the innovative policy solutions and data-driven business strategies being deployed to fix this broken market and unlock new opportunities. For those looking to navigate and win in the complex pharmaceutical landscape, understanding the uncontested market is no longer optional—it is essential.

Part I: The Blueprint for Competition – How the System Is Supposed to Work

To grasp why the competitive model fails for some drugs, we must first appreciate the intricate machinery designed to make it succeed. The U.S. pharmaceutical market operates on a carefully calibrated balance between rewarding innovation and fostering competition. This balance is maintained by two primary pillars: intellectual property rights, which create a temporary monopoly for new drugs, and a streamlined regulatory pathway that facilitates the entry of affordable alternatives once that monopoly ends.

The Foundation: Understanding Patents and Market Exclusivity

At its core, bringing a new drug from a laboratory concept to a patient’s bedside is an act of profound financial risk. The journey is long, arduous, and astronomically expensive, with development timelines often spanning 10 to 15 years and costs reaching into the billions. To incentivize companies to undertake this gamble, the system provides powerful, temporary monopolies through patents and FDA-granted exclusivities. These are distinct but complementary tools designed to allow innovators to recoup their R&D investments.3

A patent is a form of intellectual property granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) that gives an inventor the exclusive right to prevent others from making, using, or selling their invention for a limited time.2 For pharmaceuticals, this protection is paramount. A patent can cover the drug’s core chemical compound (a “composition-of-matter” patent), the method of using the drug to treat a specific disease, its formulation, or the process used to manufacture it.13 Under the World Trade Organization’s TRIPS agreement, the standard patent term is 20 years from the date the application is filed.1

However, a critical distinction exists between this nominal 20-year term and the drug’s effective patent life—the actual period of market exclusivity the drug enjoys post-launch. Because a company typically files for a patent very early in the development process, a substantial portion of that 20-year clock—often 10 to 15 years—is consumed by preclinical research, extensive clinical trials, and the rigorous FDA review process.1 Consequently, by the time a drug is finally approved for sale, its remaining patent life is often much shorter, typically in the range of 7 to 12 years.3 This “lost time” is the central justification for the second layer of protection: FDA exclusivity.

FDA exclusivities are exclusive marketing rights granted by the FDA upon a drug’s approval, operating independently of its patent status. They are a creation of statute, designed to promote a balance between innovation and generic competition. Several key types of exclusivity exist, each with a different purpose and duration:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: This provides a 5-year period of market protection for a drug containing an active moiety (the key therapeutic part of the molecule) that the FDA has never previously approved.1 During this time, the FDA is barred from even accepting a generic application for the first four years if it contains a patent challenge.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): To stimulate R&D for treatments of rare diseases (defined in the U.S. as affecting fewer than 200,000 people), the Orphan Drug Act grants a 7-year period of market exclusivity for the approved orphan indication.17

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: Often called “3-year” or “other” exclusivity, this is granted for applications seeking approval for a change to a previously approved drug, such as a new indication, dosage form, or strength. The key requirement is that the application must be supported by new, essential clinical investigations. This exclusivity bars the FDA from approving a generic version for that specific change for three years.

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): As a powerful incentive for manufacturers to study their drugs in children, the FDA can offer an additional 6 months of market protection. This 6-month period is added to any existing patents and exclusivities on all of the manufacturer’s drug products that contain the same active moiety.

- Biologics Exclusivity: Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), novel biologic products are granted a 12-year period of exclusivity from the date of first licensure, reflecting their greater complexity and development cost.

The system is intentionally designed with these overlapping, sometimes redundant, layers of protection. A single drug can simultaneously hold multiple patents and be eligible for various exclusivities. For example, a new cancer drug might launch with a composition-of-matter patent, 5 years of NCE exclusivity, and later gain a 6-month pediatric extension. If it is subsequently approved for a new use, it could gain an additional 3 years of exclusivity for that indication. This complexity is not a flaw but a feature, intended to create a robust and multi-faceted incentive structure that rewards innovation at every stage of a drug’s lifecycle.

However, this very complexity creates a double-edged sword. While the layered protections are designed to be a shield for innovators, they can also be wielded as a sword to delay competition. The intricate web of patents and exclusivities creates a formidable legal and regulatory minefield for any potential generic competitor to navigate. This sets the stage for strategic “evergreening,” where companies file for new patents on minor tweaks to a product, or “stacking” exclusivities to prolong a monopoly well beyond the period initially envisioned by lawmakers. The system designed to foster the birth of new medicines contains the very seeds of the competition problem that can leave older medicines stranded without rivals.

The Game-Changer: The Hatch-Waxman Act and the Dawn of Generics

For decades, the end of a drug’s patent life did not automatically lead to affordable alternatives. Generic manufacturers faced the same monumental hurdle as innovators: they had to conduct their own expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to prove their copycat drug was safe and effective, even though the original had already cleared that bar. This created a powerful, de facto extension of the brand’s monopoly. The landscape was irrevocably transformed in 1984 with the passage of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act.19

This landmark legislation struck a grand bargain that created the modern generic drug industry as we know it today.21 It was a masterful piece of political compromise, balancing the interests of two powerful, opposing forces. For innovator companies, it offered a way to reclaim some of the patent life they lost during the lengthy FDA review process through Patent Term Extension (PTE). But for the public and the burgeoning generic industry, it delivered something far more revolutionary: a streamlined, abbreviated pathway to market.

The cornerstone of Hatch-Waxman is the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. This allows a generic manufacturer to gain FDA approval without repeating costly clinical trials. Instead of proving safety and efficacy from scratch, the ANDA applicant’s primary task is to demonstrate that its product is a pharmaceutical and therapeutic equivalent to the innovator’s product, which is known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD).23 This involves proving two key things:

- Pharmaceutical Equivalence: The generic drug must contain the same active ingredient, have the same strength, use the same dosage form (e.g., tablet, capsule), and be administered by the same route (e.g., oral, injectable) as the RLD.23

- Bioequivalence (BE): The generic must deliver the same amount of the active ingredient into a patient’s bloodstream over the same period of time as the brand-name drug. This is typically demonstrated through BE studies in healthy volunteers, where blood levels are measured after taking both the generic and the brand drug. The results must fall within a statistically acceptable range to ensure the generic will produce the same clinical effect.24

Beyond creating this efficient pathway, Hatch-Waxman also introduced a powerful mechanism to challenge weak or invalid patents, igniting the competitive fire that defines the industry. A generic company filing an ANDA must make a certification regarding the patents listed for the RLD in the FDA’s “Orange Book.” The most aggressive of these is the “Paragraph IV” (PIV) certification, in which the generic applicant declares that it believes the brand’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.

Filing a PIV certification is an act of “permissible patent infringement” and typically triggers a lawsuit from the brand manufacturer. The filing of that lawsuit, in turn, automatically imposes a 30-month stay on the FDA’s ability to grant final approval to the generic, giving the parties time to litigate the patent dispute. To reward generic companies for taking on the immense financial risk and legal burden of this litigation, Hatch-Waxman created one of the most valuable prizes in the pharmaceutical industry: 180-day exclusivity. The first generic applicant to submit a substantially complete ANDA with a PIV certification is granted an exclusive 180-day period to market its generic drug.17 During this six-month window, the FDA cannot approve any other generic versions of the same drug, allowing the first-filer to capture a significant market share, often at a price only modestly discounted from the brand.

The impact of Hatch-Waxman cannot be overstated. Before its passage in 1984, generics accounted for just 19% of prescriptions. Today, that number is over 90%. The Act successfully built a robust pipeline for competition. However, the very incentives it created have had profound, and perhaps unintended, consequences. The allure of the 180-day exclusivity prize—a potential windfall worth hundreds of millions of dollars—has fundamentally shaped the strategic calculus of the entire generic industry. It created a “winner-take-all” race to be the first-to-file a PIV challenge against the next blockbuster drug.

This intense focus on high-stakes patent litigation for high-value targets has, in turn, diverted resources, attention, and R&D investment away from less glamorous opportunities. Generic companies, as rational economic actors, will naturally allocate their limited legal and development budgets toward the activities with the highest potential return. The pursuit of 180-day exclusivity on a multi-billion-dollar drug is a far higher priority than developing a generic for an old, off-patent, small-market drug that offers no such prize. Thus, the very mechanism that makes the generic market so ferociously competitive for some drugs is a direct, if unintentional, cause of the profound lack of interest and competition for others. It has created a system of pharmaceutical “haves” and “have-nots,” leaving a whole class of older medicines stranded in the non-competitive wilderness.

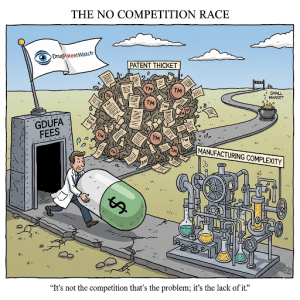

Part II: When the Blueprint Fails – Deconstructing the Barriers to Entry

The Hatch-Waxman framework provides a clear blueprint for how competition should emerge. Yet, as the FDA’s own list of uncontested drugs demonstrates, this blueprint frequently fails. The reasons are not singular but multifaceted, forming a series of formidable walls that can deter or prevent generic entry. These barriers are not always legal or regulatory in nature; they are often rooted in cold economic calculations, daunting technical challenges, and sophisticated corporate strategies. To understand the paradox of the uncontested market, we must deconstruct each of these barriers in detail.

The Economic Wall: When the Numbers Don’t Add Up

For many off-patent drugs languishing without a generic rival, the primary barrier is not a patent or a legal strategy, but a simple, brutal economic reality: the potential return on investment is too low to justify the costs and risks of entering the market. Generic drug manufacturing, despite its reputation for producing low-cost medicines, is a capital-intensive business, and if the numbers don’t add up, no company will take the plunge.

The most significant economic deterrent is the small market trap. Many of the drugs on the FDA’s uncontested list are older therapies for niche conditions or rare diseases, meaning they have a limited patient population and, consequently, low sales volume.7 An analysis by the IQVIA Institute found that the median annual spending in 2017 on expired orphan drugs that faced no competition was a mere $8.6 million. For a generic manufacturer accustomed to operating on the scale of blockbuster drugs with billions in annual sales, such a small prize is often economically unattractive. The case of Daraprim, a drug for the rare parasitic infection toxoplasmosis, is a prime example. For decades, it saw no generic competition in the U.S. largely because it was prescribed only about 2,000 times per year, making it an unappealing target for development.

This problem of low potential revenue is compounded by substantial and inflexible upfront costs. The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), while successful in speeding up review times, introduced significant, non-refundable fees that must be paid to the FDA. For fiscal year 2025, the fee for filing a single ANDA is $321,920, with additional annual fees for facilities and program participation that can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. These fees represent a major capital investment that must be made long before a single dollar of revenue is generated. They act as a powerful barrier to entry, particularly for smaller companies or for those considering a niche product with modest profit potential.

Even if a company is willing to stomach the upfront costs, it must contend with the harsh reality of intense price erosion. The very success of the generic market has created a hyper-competitive environment that has been described as a “race to the bottom”. Data shows that while the first generic entrant might capture a price around 30-40% below the brand, the entry of a second or third competitor causes the price to plummet dramatically, often falling by 70% or more.5 This dynamic forces generic manufacturers to be incredibly selective in their portfolio choices. They must prioritize products where they can either secure a period of exclusivity (like the 180-day prize) or where the market is large enough to remain profitable even at a fraction of the original price. For a small-market drug, the entry of just one other competitor can instantly erase any potential for profit. This leads to a perverse equilibrium: knowing that the market can’t support more than one or two players, many companies will independently conclude that the risk of being the second or third entrant is too high. The “rational” decision for everyone is to not enter at all, leading to a “market of one” by default. This isn’t a result of collusion; it’s the outcome of multiple companies making the same logical assessment of poor market fundamentals. It’s a market failure born from the system’s success.

The Manufacturing Gauntlet: More Than Just Copying a Recipe

A common misconception is that creating a generic drug is a simple act of chemical mimicry. In reality, it is a complex scientific and technical endeavor, a gauntlet that requires reverse-engineering a product and its performance profile, often without the innovator’s proprietary blueprints, and then manufacturing it consistently to meet today’s ever-more-stringent quality standards. For many older, off-patent drugs, these technical hurdles are insurmountable.

The challenge is most acute for what the FDA terms “complex generics.” These are not your standard oral tablets. They include products like sterile injectables, biologics (which lead to “biosimilars,” not generics), drug-device combinations like asthma inhalers, and drugs with complex formulations or delivery systems.29 Developing a generic version of these products requires specialized technology, advanced analytical capabilities, and deep institutional expertise that many manufacturers simply do not possess. The capital investment required to build or retool a manufacturing line for a complex injectable, for instance, can be prohibitive, especially when the target market is small.

Even for seemingly simpler drugs, the supply chain for the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) can be a major bottleneck. Some older drugs are synthesized through complex chemical processes, or their key starting materials may be difficult to source. In some cases, there may be only one or two qualified suppliers of the API in the world. If a would-be generic competitor cannot secure a reliable, high-quality, and cost-effective source of the API, its development program is dead on arrival. This dependency creates a powerful barrier to entry, as the sole API supplier can effectively control who is able to enter the market.34

Furthermore, the scientific cornerstone of the ANDA process—proving bioequivalence (BE)—can be a minefield. While a standard BE study in healthy volunteers is routine for many drugs, it is not always sufficient. For “highly variable drugs,” whose absorption can differ greatly from person to person, proving equivalence may require studies with a very large number of subjects, driving up costs significantly. For locally acting drugs, such as topical creams or inhaled products that act directly on the skin or lungs, measuring blood levels is often meaningless. In these cases, the FDA may require full-blown clinical endpoint studies—essentially, comparative efficacy trials against the brand product—to demonstrate equivalence. Such studies can add millions of dollars and several years to the development timeline, turning a seemingly straightforward generic project into a high-risk R&D program.

Overlaying all of these challenges is the rising bar for quality and regulatory compliance. A watershed moment for the industry was the “Nitrosamine Crisis” that began in 2018, when probable human carcinogens called nitrosamines were discovered as impurities in widely used blood pressure and heartburn medications. These impurities were not added intentionally; they were byproducts of specific manufacturing processes. The regulatory response has been swift and sweeping, with the FDA and other global agencies now requiring all manufacturers to conduct comprehensive risk assessments, perform advanced analytical testing, and, if necessary, re-validate or reformulate their processes to eliminate these impurities.

This has created a “legacy product trap” for older drugs. A drug approved decades ago was reviewed under a different set of quality standards. A new generic entrant today, however, must meet the much higher bar of 21st-century standards. This may require a complete overhaul of the original manufacturing process, significant investment in advanced analytical technology, and a level of scientific rigor that the innovator never had to apply. When this inflated cost of modernization is weighed against the small market potential of an old, niche drug, the business case often collapses. The rising tide of quality standards, while absolutely essential for protecting public health, has the unintended consequence of making it economically impossible to launch generics for a specific class of older drugs, effectively stranding them in an uncontested, and potentially lower-quality, state.

Strategic Obstacles: Gaming the System to Delay Competition

Beyond the formidable economic and technical barriers, a third wall often stands in the way of generic competition: the deliberate and sophisticated strategies employed by brand-name manufacturers to actively obstruct and delay the entry of rivals. These tactics exploit the legitimate, and often complex, pathways of the patent and regulatory systems, weaponizing them for a purpose they were never intended for—to create artificial barriers to competition and prolong a lucrative monopoly.

One of the most well-known and effective strategies is the creation of “patent thickets.” This involves filing dozens, sometimes hundreds, of patents around a single blockbuster drug. While the initial composition-of-matter patent on the core molecule is the most important, brand companies will strategically build a dense web of secondary patents covering every conceivable aspect of the product: different formulations (e.g., extended-release versions), new methods of use for different diseases, specific dosage regimens, metabolites the body produces after taking the drug, and even the devices used to administer it, like inhalers or injectors.2

This thicket of patents creates a legal minefield for a generic competitor. To launch its product, the generic company must challenge not just one patent, but potentially dozens, in court. The cost of such sprawling litigation is astronomical, and the risk is immense. The brand company only needs to win on a single patent to block the generic’s entry. As legal expert Professor Jacob Sherkow has noted, while regulators are attempting to curb this practice, clever companies may still find ways around the rules. The patent thicket shifts the battleground from the laboratory, where scientific innovation is paramount, to the courtroom, where victory often goes to the party with the deepest pockets and the highest tolerance for legal warfare.

When litigation does occur, it can sometimes end not with a court verdict, but with a controversial settlement known as a “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” agreement. In a typical patent settlement, the party accused of infringing pays the patent holder. In a reverse payment, the flow of money is reversed: the brand-name patent holder pays the generic challenger to settle the lawsuit. In exchange for this payment, the generic company agrees to delay the launch of its competing product for a specified period. According to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which actively litigates against these deals, such agreements are anticompetitive and cost consumers and taxpayers an estimated $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year. They allow the brand to maintain its monopoly price without risking the invalidation of its patents in court, while the generic company gets a guaranteed, risk-free payday.

Another tactic involves the weaponization of a regulatory process intended to protect public health: the citizen petition. The FDA allows any “interested person,” including a company, to file a citizen petition requesting that the agency take or refrain from taking an administrative action. Brand companies have used this process to raise last-minute questions about the safety, quality, or equivalence of a pending generic application, often just as the generic is on the cusp of approval. The goal is not always to raise a legitimate scientific issue, but to trigger a procedural delay while the FDA investigates the claims. Recognizing this “gaming” of the system, the FDA has issued firm guidance stating that it will not delay an ANDA approval based on a petition unless it is “necessary to protect public health” and that it may refer petitions submitted with the primary purpose of delay to the FTC for antitrust review.

Other strategies abound, from “product hopping,” where a brand company makes a minor, often non-superior, change to its drug (e.g., switching from a capsule to a tablet) and heavily markets the “new” version to switch patients just before the original version’s patent expires, to implementing restrictive distribution systems. Some specialty drugs are distributed through controlled networks that make it difficult or impossible for generic developers to obtain the samples of the brand product they are legally required to have to conduct their bioequivalence studies.40

These strategies, summarized in the table below, represent a fundamental subversion of the competitive process. They exploit legitimate pathways—patenting, litigation, regulatory petitions—to create artificial, procedural barriers that raise the cost and uncertainty of generic entry to an untenable level. For a company considering a generic version of a smaller-market drug, the prospect of not only navigating the economic and technical hurdles but also fighting a multi-front war against a well-funded incumbent is often the final nail in the coffin of the business case.

Table 1: A Taxonomy of Barriers to Generic Competition

| Barrier Category | Specific Barrier | Description & Example | Key Sources |

| Economic | Small Market Size | The potential patient population and sales revenue are too low to justify the investment in development and manufacturing. Ex: Orphan drugs with median annual spending of only $8.6M. | , \ |

| GDUFA Fees | High, non-refundable fees required by the FDA for application submission and facility maintenance act as a significant upfront cost barrier, especially for low-margin products. | \ | |

| Price Erosion | Intense competition in the generic market leads to a rapid and steep decline in price, making profitability unsustainable for drugs with low sales volume. | , \ | |

| Manufacturing/Technical | Complex Formulations | Products like sterile injectables, biologics, or drug-device combinations require specialized expertise and equipment that not all manufacturers possess. | , \ |

| API Supply Chain Bottlenecks | The active pharmaceutical ingredient may be difficult to synthesize or available only from a single, controlled source, preventing new entrants from securing supply. | , \ | |

| Stringent Quality Standards | Meeting modern quality standards (e.g., for nitrosamine impurities) for older drugs can require costly process overhauls and advanced testing, making entry economically unviable. | , \ | |

| Regulatory | Difficult Bioequivalence Studies | Proving bioequivalence for some drugs (e.g., locally acting or highly variable) can require expensive and lengthy clinical endpoint trials instead of standard blood-level studies. | \ |

| Strategic/Legal | Patent Thickets | Brand companies file numerous, overlapping patents on minor aspects of a drug, creating a dense and costly legal minefield for generics to challenge. | , \ |

| Pay-for-Delay Settlements | Brand firms pay generic challengers to settle patent litigation and delay the launch of their competing product, eliminating competition for a set period. | , \ | |

| Abusive Citizen Petitions | Brand firms file petitions with the FDA raising last-minute, often spurious, safety concerns about a pending generic to trigger procedural delays in its approval. | , \ | |

| Restrictive Distribution | Brand firms limit the distribution of their product, making it impossible for generic companies to obtain the samples legally required for bioequivalence testing. | , \ |

Part III: The Consequences of an Uncontested Market

When the blueprint for competition fails and these barriers converge, the consequences are not merely theoretical. They manifest in the real world as tangible harms to patients, payers, and the entire healthcare system. The absence of competition grants a sole-source manufacturer nearly unchecked pricing power, creates vulnerabilities in the drug supply chain, and can stifle the very innovation the patent system was designed to foster. To truly understand the stakes, we must examine these consequences, starting with the case that brought this issue into the global spotlight.

Case Study in Focus: The Story of Daraprim

No case better illustrates the anatomy of an uncontested market and its potential for exploitation than that of Daraprim. It is the quintessential story of what happens when a confluence of barriers—a small market, a controlled distribution system, and a new owner with an aggressive pricing strategy—creates a perfect storm.

The drug at the center of the controversy is pyrimethamine, branded as Daraprim. It is a 62-year-old medication, first developed in the 1950s, used to treat toxoplasmosis, a parasitic infection that can be particularly dangerous for individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or certain cancer patients.43 For decades, Daraprim was an effective, well-tolerated, and affordable treatment.

In August 2015, a startup pharmaceutical company called Turing Pharmaceuticals, founded and led by a former hedge fund manager named Martin Shkreli, acquired the U.S. marketing rights to Daraprim. Almost immediately, Turing executed a shocking business decision: it raised the price of a single tablet by more than 5,000%, from $13.50 to $750.45 This single move transformed the annual cost of treatment for some patients from a manageable expense to hundreds of thousands of dollars.44

This audacious price hike was possible for one simple reason: Daraprim, despite being long off-patent, existed in a competition-free zone. The market was small, deterring large generic houses, and Turing had implemented a closed distribution and specialty pharmacy model that made it exceedingly difficult for any would-be generic competitor to obtain the drug samples needed to conduct bioequivalence testing.7 It was a classic, and now infamous, uncontested market.

The public and political backlash was swift and ferocious. Medical societies like the Infectious Diseases Society of America condemned the price hike as “unjustifiable” and “unsustainable”. Presidential candidates and members of Congress held hearings, and Shkreli himself became a global symbol of pharmaceutical greed. His defense was that the massive profits were necessary to fund research and development for a new, better treatment for toxoplasmosis. This justification was widely dismissed by the medical community, which pointed out that Daraprim was already a highly effective drug and that no one had been clamoring for a new one. An internal email from Shkreli revealed a more direct motivation: “Should be a very handsome investment for all of us. Let’s all cross our fingers that the estimates are accurate”.

The aftermath of the Daraprim saga is as instructive as the event itself. While a compounding pharmacy eventually began offering a $1-per-capsule alternative, this is not the same as an FDA-approved, bioequivalent generic and does not represent a systemic solution to the problem. Martin Shkreli was later convicted and sentenced to prison, but for unrelated securities fraud from his hedge fund days; the Daraprim price hike, while widely viewed as unethical, was entirely legal.

The Daraprim case is critically important because it moved the issue of uncontested markets from the pages of industry journals to the front pages of newspapers. It provided a stark, undeniable demonstration that a drug’s price is not necessarily tied to its R&D cost, its manufacturing expense, or its clinical value. In the absence of competition, a drug’s price is determined by a single factor: what the market will bear. It laid bare the economic vulnerability created by this market failure and served as a powerful catalyst for the policy discussions and regulatory reforms, such as the FDA’s Competitive Generic Therapy pathway, that would follow. It proved that the perpetual monopoly is not a theoretical risk but a real-world vulnerability that can be, and has been, systematically exploited.

Beyond Price Hikes: The Ripple Effects of No Competition

While a 5,000% price increase is the most dramatic and headline-grabbing consequence of an uncontested market, the ripple effects of a lack of competition are far broader and, in some ways, more insidious. They create systemic fragilities that threaten patient access, strain healthcare budgets, and undermine the long-term health of the pharmaceutical ecosystem.

The most immediate threat beyond pricing is the creation of chronic drug shortages. When only one manufacturer produces a given drug, the entire supply chain for that medicine becomes extraordinarily fragile.7 Any disruption at that single manufacturing site—a quality control failure leading to a plant shutdown, a fire, a natural disaster affecting the facility, or even a simple business decision to discontinue the product line—can trigger a nationwide shortage of an essential medicine. The FDA has identified manufacturing quality issues as the leading cause of drug shortages, a problem that disproportionately affects older, sterile injectable generic drugs that are complex to produce. These shortages are not minor inconveniences. They lead to delayed treatments for cancer patients, force hospitals to use less-effective or less-safe alternative therapies, increase the risk of medication errors as clinicians work with unfamiliar products, and impose significant financial and logistical burdens on health systems trying to manage the scarcity.31

Furthermore, the absence of competitive pressure leads to stagnation in quality and manufacturing innovation. In a competitive market, manufacturers are incentivized to improve their processes, increase efficiency, and enhance product quality to gain an edge. A sole-source manufacturer of an old, off-patent drug faces no such pressure. There is little to no financial incentive to invest millions of dollars in upgrading an outdated manufacturing facility to incorporate Advanced Manufacturing Technologies (AMTs) like continuous manufacturing, which can improve quality and reduce the risk of shortages. The focus shifts from innovation and improvement to simply maintaining the status quo, which can perpetuate latent quality risks and leave the supply chain vulnerable.

Finally, the burden on patients and the healthcare system is immense. Patients are faced with a double-bind of affordability and access issues. Even when a drug is available, its high price can place it out of reach, leading to patients rationing or forgoing essential treatment. The healthcare system, in turn, bears the financial brunt. Studies have shown that government programs like Medicare are massively overpaying for some generic drugs. One analysis found that Medicare Part D spent $2.6 billion more for 184 common generics in 2018 than cash-paying members at a retail chain like Costco would have. Another report found that Medicare could have saved $3 billion if generic versions had been dispensed instead of available brand-name drugs. These are not just numbers on a spreadsheet; they represent wasted resources that could be used to fund other aspects of patient care, and they underscore the profound financial cost of a market that fails to compete.

The Special Case: How Orphan Drug Exclusivity Creates Extended Monopolies

The conversation about extended monopolies often turns to the complex and controversial role of the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 (ODA). Enacted with the noble goal of incentivizing the development of drugs for rare diseases, the Act has been a remarkable success in bringing treatments to patients who were previously neglected. However, its powerful exclusivity provisions can also be leveraged strategically to delay competition for drugs that ultimately achieve blockbuster sales, creating protected monopolies that last far longer than patents alone would allow.

The core incentive of the ODA is a seven-year period of market exclusivity (ODE) granted to a drug upon its approval for a specific designated orphan indication.17 During this period, the FDA is barred from approving any other application—brand or generic—for the same drug for the same rare disease. The critical nuance, and the source of the controversy, lies in how this exclusivity can be applied. A single drug can be approved for multiple different orphan indications over time, and each new approval can come with its own fresh seven-year grant of exclusivity for that specific use. This creates the potential for a “stacking” strategy, where a company can build a fortress of sequential exclusivities that shields its product from competition for decades.

The financial implications of this are staggering. A 2020 study published in Health Affairs analyzed drugs with multiple orphan approvals and found a dramatic impact on their effective monopoly periods. While a single orphan approval grants seven years of protection, the study found that securing a second orphan approval extended a drug’s total market exclusivity by an average of 4.7 additional years. For drugs with five separate orphan approvals, the average extension was 13.4 years beyond the initial period. The study identified 16 drugs that had managed to secure exclusivity for at least a decade longer than their original seven-year term. The potential budget impact of this additional, competition-free time on the market was estimated to be a breathtaking $591 billion over a seven-year period following the end of the first approval.

However, the story of orphan drugs is not one of simple exploitation. A more nuanced analysis from the IQVIA Institute provides an important counterpoint. Their 2018 report found that for the majority of drugs with orphan designations, it is their underlying patents, not the seven-year ODE, that provide the longest period of protection. More importantly, the report looked at 217 orphan-designated drugs whose patents and exclusivities had all expired. Of these, a remarkable 101—nearly half—still faced no generic competition. The reason was not a lingering legal barrier, but simple economics. The median annual spending on these uncontested orphan drugs was just $8.6 million, a market size far too small to attract generic investment.

These two findings are not contradictory; they describe a bifurcated reality for the Orphan Drug Act. On one hand, it is successfully fulfilling its original mission: encouraging development for truly rare diseases with small, unprofitable markets where competition would never naturally arise. On the other hand, its provisions are being strategically used by some manufacturers in a “salami-slicing” approach—seeking sequential orphan approvals for a single product to create a long-lasting and highly lucrative monopoly for what ultimately becomes a blockbuster drug.

This dual legacy makes policy reform exceptionally difficult. A blunt change to the ODA, such as limiting the number of exclusivities a drug can receive, could have a chilling effect on investment for genuinely rare diseases. Yet, inaction allows for the continued strategic use of the Act to extend the monopolies of some of the industry’s highest-revenue products. It highlights the immense challenge of crafting “one-size-fits-all” pharmaceutical policy in a world where the same regulatory tool can be used for vastly different ends.

Part IV: Forging a Path Forward – Solutions and Strategies

The emergence of a persistent class of uncontested, off-patent drugs has not gone unnoticed by regulators, policymakers, or savvy industry players. In response to the market failures and anticompetitive gaming that lead to price hikes and shortages, a multi-pronged effort is underway to forge a path toward a more competitive and sustainable market. This effort spans proactive FDA policies to incentivize entry, sophisticated business strategies to identify hidden opportunities, and broader legislative reforms aimed at tackling the systemic root causes of the problem.

Policy in Action: The FDA’s Push for Competition

Faced with mounting evidence of market dysfunction, the FDA has shifted from being a passive gatekeeper to an active proponent of competition. In 2017, the agency launched its Drug Competition Action Plan (DCAP), a comprehensive initiative aimed squarely at encouraging the robust and timely entry of generic drugs. The plan is built on three key pillars: improving the efficiency of the ANDA review process, closing regulatory loopholes that allow brand companies to “game” the system, and, most importantly, streamlining the standards and lowering the barriers for complex generic products.

The flagship program born from this new philosophy is the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway. Created by the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (FDARA), the CGT pathway is a landmark policy designed specifically to address the paradox at the heart of this report.51 Its purpose is to create a viable business case for developing generics of drugs where one does not currently exist.

The program works by targeting drugs with “inadequate generic competition,” which the FDA defines as a market with not more than one approved drug (either the brand or a single generic) available.52 For a drug that meets this criterion, a generic applicant can request a CGT designation. If granted, this designation unlocks two powerful incentives:

- Expedited Review: The FDA may expedite the development and review of the ANDA, potentially engaging in more frequent meetings with the applicant to resolve scientific issues and shorten the time to approval.

- 180-Day Exclusivity: This is the game-changer. For a CGT-designated drug that had no unexpired patents or exclusivities listed in the Orange Book at the time of submission, the first approved applicant is eligible for a 180-day period of marketing exclusivity.52

This exclusivity provision is a brilliant piece of policy engineering. It directly confronts the economic wall that prevents competition for so many older drugs. As we’ve seen, the traditional 180-day exclusivity under Hatch-Waxman is only available for challenging patents, leaving a gaping hole for off-patent products. The CGT pathway fills this exact gap. It artificially creates a lucrative financial prize—a temporary, protected monopoly—in markets where the underlying economics are otherwise too poor to attract investment. It is a targeted economic intervention designed by the government to act as a market-maker, attempting to correct a systemic failure by creating a new incentive structure.

The uptake of the program demonstrates that it is addressing a real need. As of August 2020, the FDA had received hundreds of CGT requests and granted over 320 designations. By early 2021, it had approved 63 unique generic products that were eligible for the coveted CGT exclusivity. However, the program is not a panacea. More recent data from 2024 suggests a potential slowdown in the number of products successfully securing and launching with the exclusivity. This could indicate that the lowest-hanging fruit—the most commercially viable CGT targets—have already been picked. It also highlights another hurdle: to retain the exclusivity, a company must launch its product within 75 days of approval, a timeline that can be challenging due to manufacturing scale-up and supply chain logistics. The CGT pathway is a powerful tool, but its success is a direct reflection of the immense power of the underlying economic and technical barriers it seeks to overcome.

Strategic Opportunity: Turning Data into Competitive Advantage

For astute pharmaceutical companies, the landscape of uncontested markets is not just a policy problem to be observed; it is a field of strategic opportunity waiting to be cultivated. While the blockbuster drugs attract a swarm of competitors leading to a brutal price war, the quiet corners of the market—the niche, low-competition products—can offer a rare chance for sustainable profitability and a strong market foothold. The key is to move beyond a reactive, manufacturing-led approach (“What can we copy cheaply?”) and adopt a proactive, intelligence-driven strategy (“Where is there a durable, low-competition market that we are uniquely positioned to win?”).

Executing this strategy requires a sophisticated understanding of the barriers to entry and a clear-eyed assessment of one’s own corporate capabilities. The goal is to identify a drug where the specific barriers that have kept others out are ones that your company is equipped to overcome. This could be deep in-house expertise in a complex manufacturing process like sterile injectables, a secure and proprietary API supply chain, or the financial resources and legal appetite to cut through a dense patent thicket.

This level of strategic analysis is impossible without robust, integrated data. Information on patent status, exclusivity dates, ongoing litigation, market size, and regulatory hurdles is fragmented across disparate sources like the USPTO, the FDA’s Orange Book, court dockets, and financial filings. This is where analytical platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable tools for the modern pharmaceutical strategist. By aggregating, structuring, and analyzing this vast sea of data, these platforms turn raw information into actionable competitive intelligence.

A company can leverage such a platform to execute a multi-step analytical process:

- Monitor the Landscape: Use patent expiration and litigation data to build a comprehensive map of the entire market, identifying which drugs are nearing the end of their lifecycle and which are entangled in legal battles that might create an unexpected opening.

- Analyze the Competitive Environment: For a given off-patent drug, determine the number of existing competitors. A market with fewer than three manufacturers often signals a low-competition opportunity with the potential for more stable pricing.

- Assess Market Viability: Analyze prescription volume and sales data to ensure the market is large enough to be profitable but not so large that it will attract a flood of rivals.

- Identify First-to-File Opportunities: By tracking Paragraph IV certifications and the status of brand-name patents, a platform like DrugPatentWatch can help a company pinpoint drugs where a risky but highly lucrative 180-day exclusivity play under Hatch-Waxman might be possible.

- Target CGT Candidates: Systematically screen the FDA’s list of off-patent, off-exclusivity drugs to identify prime candidates for the CGT pathway, cross-referencing them with internal manufacturing capabilities and market forecasts.

This data-driven approach represents a fundamental evolution in generic strategy. Success is no longer just about being the fastest or the cheapest. It’s about being the smartest—picking the right market to enter in the first place. The ability to effectively leverage data analytics to uncover these hidden pockets of opportunity is rapidly becoming a core competency and a key differentiator for the most successful generic and specialty pharmaceutical companies.

The Broader Horizon: Legislative and Systemic Reforms

While the FDA’s initiatives are a critical step forward, there is a growing recognition that the problem of “no competition” is a systemic issue that cannot be solved by one agency alone. The root causes are woven into the very fabric of intellectual property law, antitrust enforcement, and healthcare reimbursement policy. As a result, a broader, multi-agency effort is underway to address the problem holistically.

Antitrust enforcement has become a key front in this battle. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) are taking an increasingly aggressive stance against anticompetitive behavior in the pharmaceutical sector. They are actively scrutinizing and litigating against “pay-for-delay” settlements, investigating practices like “product hopping” and the use of restrictive distribution networks, and challenging potentially anticompetitive mergers.37 In a clear sign of this coordinated approach, the FTC and DOJ, along with the Departments of Health and Human Services and Commerce, have recently held a series of public listening sessions to solicit stakeholder input on identifying and dismantling barriers to drug price competition.41

There is also a growing movement for U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) reform. Critics argue that the PTO has historically been too lenient in granting weak, incremental patents that contribute little to innovation but add significantly to the “patent thickets” that deter generic entry. Proposed reforms aim to empower the PTO to more rigorously examine patent applications, raising the bar for what constitutes a truly novel and non-obvious invention worthy of a 20-year monopoly.

Perhaps the most complex and impactful area of reform focuses on the role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and the design of drug formularies. PBMs, the powerful intermediaries that manage prescription drug benefits for health plans, negotiate rebates with brand-name manufacturers. These rebates, while ostensibly meant to lower costs, can create perverse incentives. A PBM may choose to give preferential formulary placement to a high-price, high-rebate brand drug over a lower-cost generic or biosimilar, because the PBM’s own revenue is often tied to the size of the rebate.32 This can create a formidable commercial barrier to entry, where a newly approved generic finds itself effectively blocked from the market because patients cannot get it covered by their insurance. The intense scrutiny now being placed on PBM business practices by Congress and federal agencies could lead to significant changes in how drug prices are negotiated and how formularies are designed, potentially leveling the playing field for new generic entrants.

This multi-front approach demonstrates a crucial realization among policymakers: a generic drug’s journey to market does not end with FDA approval. A company can successfully navigate the scientific and regulatory hurdles to get its ANDA approved, only to be blocked from launching by a patent thicket (a PTO/legal issue), kept off the market by a pay-for-delay deal (an FTC/DOJ issue), or shut out of patient access by a PBM’s formulary (a reimbursement/commercial issue). The joint inter-agency listening sessions are explicit proof that the government now understands this interconnected reality. The ultimate solution to the paradox of the uncontested market will require a holistic, systemic reform that aligns incentives and closes loopholes across all of these interdependent systems.

Conclusion: Balancing Innovation, Access, and a Sustainable Market

The phenomenon of drugs existing without patents and without competition is far from a minor market quirk. It is the logical, and troubling, outcome of a complex system where powerful economic, technical, regulatory, and strategic barriers converge to stifle the very competition that our healthcare system relies on to ensure affordability and access. It reveals a fundamental tension at the heart of the pharmaceutical industry: the delicate and often precarious balance between incentivizing groundbreaking innovation and ensuring the long-term sustainability of a competitive market for all medicines, not just the blockbusters.

We have seen that the journey from a brand-name monopoly to a competitive generic market, while elegantly designed in theory by the Hatch-Waxman Act, is fraught with potential points of failure. The economic calculus for many older, niche drugs simply does not support the high costs and risks of entry in a world of GDUFA fees and precipitous price erosion. The manufacturing gauntlet has become more challenging than ever, as rising quality standards create a “legacy product trap” that makes it economically unviable to modernize the production of old drugs. And the system itself, with its intricate layers of patents and regulations, has been weaponized by some incumbents to create artificial barriers that deter even the most determined challengers.

The consequences of this market failure are severe and undeniable. The Daraprim case provided a shocking, high-profile lesson in the near-limitless pricing power that a sole-source monopoly confers. But beyond the headlines, the lack of competition quietly fuels chronic drug shortages, creates disincentives for quality improvement, and places an immense financial burden on patients and the healthcare system.

Yet, the story is not one of intractable failure. It is one of adaptation and response. The FDA’s Drug Competition Action Plan, and particularly the innovative Competitive Generic Therapy pathway, represents a direct and targeted intervention to mend the broken economics of these uncontested markets. The heightened scrutiny from antitrust enforcers at the FTC and DOJ signals a new era of accountability for anticompetitive gaming. And for the strategic-minded pharmaceutical company, this challenging landscape presents a clear opportunity. By leveraging sophisticated data analytics from platforms like DrugPatentWatch and aligning corporate capabilities with the right niche markets, firms can navigate these barriers and uncover pockets of sustainable profitability.

Ultimately, solving the paradox of the perpetual monopoly requires a continued, holistic effort. It demands that we refine our policies to reward true, substantive innovation while penalizing procedural gamesmanship. It requires us to think creatively about new manufacturing technologies and business models that can make producing low-volume drugs viable. And it compels us to ensure that the incentives across the entire healthcare chain—from patent law to PBM contracts—are aligned with the ultimate goal of getting safe, effective, and affordable medicines to the patients who need them. The challenge is immense, but the path forward, illuminated by a deeper understanding of why the system fails, is becoming clearer every day.

Industry Insight:

According to a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) study, anticompetitive “pay-for-delay” patent settlements, where branded drug manufacturers pay generic companies not to bring lower-cost alternatives to market, cost consumers and taxpayers an estimated $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year.

Key Takeaways

- The Paradox is Systemic, Not Anecdotal: A significant number of drugs that are long off-patent and off-exclusivity face no generic competition. This is a recognized market failure, evidenced by the FDA’s official list of such products, and it is driven by a convergence of powerful barriers.

- Economics is the Primary Barrier: For many uncontested drugs, the lack of competition stems from a rational economic calculation. The combination of a small market size, high upfront regulatory costs (GDUFA fees), and the risk of rapid price erosion upon entry of a second competitor makes the potential return on investment too low to be attractive.

- Manufacturing and Quality Standards Create a “Legacy Trap”: It is often technically and financially challenging to manufacture older drugs to meet modern, stringent FDA quality standards (e.g., for nitrosamine impurities). This “legacy product trap” can make the cost of entry prohibitively high relative to the small market potential.

- Strategic “Gaming” Weaponizes the System: Brand-name companies can employ a range of strategies—such as creating “patent thickets,” engaging in “pay-for-delay” settlements, and filing abusive citizen petitions—to create artificial legal and regulatory barriers that deter and delay generic entry.

- Consequences Extend Beyond Price Hikes: While extreme price increases (like the Daraprim case) are the most visible outcome, the lack of competition also leads to chronic drug shortages, stagnation in manufacturing quality, and a significant financial burden on patients and the healthcare system.

- Policy and Strategy are Adapting: In response, the FDA has created the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway to provide new incentives (expedited review and 180-day exclusivity) for developing generics in these markets. For companies, success now requires a data-driven strategy to identify and capitalize on these low-competition niches, using tools like DrugPatentWatch to navigate the complex landscape.

- A Holistic Solution is Required: Solving this problem requires a coordinated effort across multiple government agencies, including the FDA, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO), and antitrust enforcers like the FTC and DOJ, to close loopholes and align incentives across the entire pharmaceutical ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why can’t the government just force companies to make generics for these essential but uncontested drugs?

In a market-based economy like the United States, the government does not typically compel private companies to manufacture specific products. Pharmaceutical companies, including generic manufacturers, are for-profit entities that make business decisions based on potential return on investment. If a drug has a very small market, is complex and expensive to produce, and has a high risk of unprofitability, companies will choose not to make it. Instead of forcing production, the government’s approach, exemplified by the FDA’s CGT pathway, is to create financial incentives (like market exclusivity) to make these unattractive markets more appealing, encouraging companies to enter voluntarily.52

2. If a drug is off-patent, isn’t it illegal for a single company to have a monopoly on it?

Having a monopoly is not, in itself, illegal under U.S. antitrust law. What can be illegal is the anticompetitive conduct used to acquire or maintain that monopoly. A company can be the sole manufacturer of an off-patent drug simply because no other company has found it economically viable to enter the market—this is a “natural monopoly” and is perfectly legal.7 However, if that company actively takes steps to unlawfully exclude potential competitors—for example, by paying them not to enter the market (“pay-for-delay”) or by using sham litigation to tie them up in court—that conduct could be challenged by antitrust enforcers like the FTC. The key distinction is between a monopoly that exists due to market conditions versus one maintained through illegal, exclusionary acts.

3. How can a drug be both a high-revenue “blockbuster” and a niche “orphan drug” at the same time?

This seemingly paradoxical situation arises from the way the Orphan Drug Act is structured. A drug receives an “orphan” designation for a specific rare disease indication. A company can develop a drug that is initially approved for a single, small orphan population. Later, that same drug might be found effective for several other rare diseases, and the company can seek and receive separate orphan approvals (and separate 7-year exclusivities) for each one. Over time, the combined revenue from all these “niche” indications can add up to blockbuster-level sales (typically defined as over $1 billion annually). Furthermore, the drug might also be approved for a much more common, non-orphan condition. This “salami-slicing” strategy allows a drug to benefit from the powerful incentives of the Orphan Drug Act while ultimately serving a large and highly profitable patient population.

4. With new programs like the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway, is this problem of uncontested markets now solved?

The CGT pathway is a significant and innovative step toward solving the problem, but it is not a complete solution. The program has successfully incentivized the development of dozens of generics for previously uncontested drugs by offering a new 180-day exclusivity prize. However, it does not address all the underlying barriers. A company might still face insurmountable technical challenges in manufacturing a complex drug, or the market may be so small that even a 180-day exclusivity period isn’t enough to justify the investment. Furthermore, recent data suggests that the number of companies successfully launching with CGT exclusivity may be slowing, perhaps because the most viable targets have been addressed. The CGT program is a powerful tool, but it is one part of a much larger, ongoing effort to address a deeply complex issue.

5. As a smaller pharma company, what is the single most important factor to consider when looking for a low-competition opportunity?

The single most important factor is strategic alignment between the market’s barriers and your company’s core competencies. It’s not enough to find a drug with no competition; you must understand precisely why there is no competition and determine if your company has a unique advantage to overcome that specific barrier. For example, if the primary barrier is the complexity of sterile injectable manufacturing, the opportunity is only real if your company has best-in-class expertise and infrastructure in that area. If the barrier is a dense patent thicket, the opportunity is only viable if you have the capital and legal risk tolerance for protracted litigation. A successful strategy is not about finding the easiest target, but about finding the target where your specific strengths turn a barrier for others into a competitive moat for you.

References

- Drug Patent Life: The Complete Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- Drug Patents and Exclusivity – National CooperativeRx, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.nationalcooperativerx.com/educational-materials/drug-patents-exclusivity/

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- Generic but Expensive: Why Prices Can Remain High for Off-Patent Drugs – UC Law SF Scholarship Repository, accessed August 1, 2025, https://repository.uclawsf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3898&context=hastings_law_journal

- U.S. Consumers Overpay for Generic Drugs – May 31, 2022 – USC …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://schaeffer.usc.edu/research/u-s-consumers-overpay-for-generic-drugs/

- Drugs With No Patents And No Competition: Here’s Why – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drugs-with-no-patents-and-no-competition-heres-why/

- GENERIC DRUGS IN THE UNITED STATES: POLICIES TO ADDRESS PRICING AND COMPETITION, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6355356/

- List of Off-Patent, Off-Exclusivity Drugs without an Approved Generic …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/list-patent-exclusivity-drugs-without-approved-generic

- The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing | Congress.gov, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46679

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- Patents – WIPO, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/patents

- Pharmaceutical Lifecycle Management – Torrey Pines Law Group, accessed August 1, 2025, https://torreypineslaw.com/pharmaceutical-lifecycle-management.html

- How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/a636-article

- www.drugpatentwatch.com, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-long-do-drug-patents-last/#:~:text=They%20are%20a%20form%20of,date%20of%20patent%20application%20filing.

- Drug Patents Explained: Protecting Ideas, Promoting R&D – Am Badar, accessed August 1, 2025, https://ambadar.com/insights/patent/drug-patents-explained-protecting-ideas-promoting-rnd/

- Patents and Exclusivity | FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/92548/download

- Patents and Exclusivities for Generic Drug Products – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/patents-and-exclusivities-generic-drug-products

- www.fda.gov, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters#:~:text=The%20%22Drug%20Price%20Competition%20and,Drug%2C%20and%20Cosmetic%20Act%20(FD%26C

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- The Hatch-Waxman Act (Simply Explained) – Biotech Patent Law, accessed August 1, 2025, https://berksiplaw.com/2019/06/the-hatch-waxman-act-simply-explained/

- Generic Drugs, Overview & Basics – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/overview-basics

- The Generic Drug Approval Process – FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/generic-drug-approval-process

- What Is the Approval Process for Generic Drugs? | FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/what-approval-process-generic-drugs

- Obtaining Generic Drug Approval in the United States – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/obtaining-generic-drug-approval-in-the-united-states/

- The Generic Drug Approval Process – YouTube, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aIFSjUL6KFU

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed August 1, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- Uncovering Lucrative Low-Competition Generic Drug Opportunities …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/uncovering-lucrative-low-competition-generic-drug-opportunities/

- Orphan Drugs in the United States – IQVIA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/orphan-drugs-in-the-united-states-exclusivity-pricing-and-treated-populations.pdf

- Top 10 Challenges in Generic Drug Development …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/top-10-challenges-in-generic-drug-development/

- The Generic Industry Faces External Challenges – Lachman Consultants, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.lachmanconsultants.com/2024/02/the-generic-industry-faces-external-challenges/

- Addressing Barriers to the Development of Complex Generics: | USP, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/ea83b_complex-generics_wp_2023-07_v3.pdf

- Consumers are now actively seeking generic substitutes for branded medicines: Sujit Paul, Zota Healthcare, accessed August 1, 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/entrepreneurship/consumers-are-now-actively-seeking-generic-substitutes-for-branded-medicines-sujit-paul-zota-healthcare/articleshow/122987675.cms

- The Patent End Game: Evaluating Generic Entry into a Blockbuster Pharmaceutical Market in the Absence of FDA Incentives, accessed August 1, 2025, https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1083&context=mttlr

- STAT quotes Sherkow on pharmaceutical patents – College of Law, accessed August 1, 2025, https://law.illinois.edu/stat-quotes-sherkow-on-pharmaceutical-patents/

- Pay for Delay | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

- FDA citizen petition – Wikipedia, accessed August 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FDA_citizen_petition

- FDA In Brief: FDA issues final guidance to address ‘gaming’ by the …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-brief/fda-brief-fda-issues-final-guidance-address-gaming-use-citizen-petitions

- Addressing the Lack of Competition in Generic Drugs to Improve …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6206353/

- Listening Session: Formulary and Benefit Practices and Regulatory Abuse Impacting Drug Competition | Federal Trade Commission, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/events/2025/07/listening-session-formulary-benefit-practices-regulatory-abuse-impacting-drug-competition

- Considerations for FDA’s New Advanced Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Programs, accessed August 1, 2025, https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/publications/considerations-fdas-new-advanced-pharmaceutical-manufacturing-programs

- Economics Behind a 5,000 Percent Price hike | PolicyMatters, accessed August 1, 2025, https://policymatters.illinois.edu/economics-behind-a-5000-percent-price-hike/

- Daraprim and Predatory Pricing: Martin Shkreli’s 5000% Hike – Stanford Law School, accessed August 1, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/2015/10/05/daraprim-and-drug-pricing/

- (PDF) From Daraprim to Ethical Drug Price – ResearchGate, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377572656_From_Daraprim_to_Ethical_Drug_Price

- Daraprim Price Hike – Ethics Unwrapped, accessed August 1, 2025, https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/video/daraprim-price-hike

- Get Rich Quick With Old Generic Drugs! The Pyrimethamine Pricing Scandal – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4685150/

- Market Exclusivity for Drugs with Multiple Orphan Approvals (1983 …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32533523/

- FDA Drug Competition Action Plan, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/fda-drug-competition-action-plan

- Generic Drugs Help Hold Down Costs, But Slowdowns in …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/generic-drugs-help-hold-down-costs-slowdowns-development-and-review-present-challenges

- Competitive Generic Therapies | FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/competitive-generic-therapies

- Competitive Generic Therapies: FDA Issues Final Guidance | News & Insights, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.agg.com/news-insights/publications/competitive-generic-therapies-fda-issues-final-guidance/

- Encouraging Competition Through Generic Drugs | The Regulatory Review, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.theregreview.org/2020/04/22/fritz-encouraging-competition-generic-drugs/

- Characteristics and Outcomes of Products Seeking Competitive Generic Therapy Designation and Exclusivity – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8579229/

- FDA Updated Its Competitive Generic Therapy List – Lachman Consultants, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.lachmanconsultants.com/2024/07/fda-updated-its-competitive-generic-therapy-list/

- FTC Holds Its First Listening Session on Practices and Regulations Impacting Pharmaceutical Generic or Biosimilar Competition | Troutman Pepper Locke, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.troutman.com/insights/ftc-holds-its-first-listening-session-on-practices-and-regulations-impacting-pharmaceutical-generic-or-biosimilar-competition.html

- DOJ and FTC Host Second Session on Structural and Regulatory Impediments to Drug Competition – The National Law Review, accessed August 1, 2025, https://natlawreview.com/article/doj-and-ftc-host-second-session-structural-and-regulatory-impediments-drug

- FTC and DOJ Host Listening Session on Lowering Americans’ Drug Prices Through Competition, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/06/ftc-doj-host-listening-session-lowering-americans-drug-prices-through-competition

- Pharmaceutical Market Size, Share & Growth Report, 2032, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/impact-of-covid-19-on-pharmaceuticals-market-102685

- Generic Drugs: A Treatment for High-Cost Health Care – PMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7023936/

- Big Pharma uses effective strategies to battle generic competitors, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.drugtopics.com/view/big-pharma-uses-effective-strategies-battle-generic-competitors

- Generic Drug Development | FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/generic-drug-development

- Patents – World Health Organization (WHO), accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and-development/resources/databases/databases-on-processes-for-r-d/patents

- Pat-INFORMED – The Gateway to Medicine Patent Information – WIPO, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/pat-informed/en/

- PATENTSCOPE – WIPO, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/en/web/patentscope

- Pharmaceutical industry – Wikipedia, accessed August 1, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmaceutical_industry

- U.S. Pharmaceutical Market Size | Industry Report, 2030 – Grand View Research, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-pharmaceuticals-market-report

- A Unifying Theory of the Generic Competition Paradox: Dynamic limit pricing with advertisement – University of Guelph, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.uoguelph.ca/economics/sites/uoguelph.ca.economics/files/public/home/apapanas/documents/Papanastasiou_GCP_Job_Market_Paper.pdf

- HOW INCREASED COMPETITION FROM GENERIC DRUGS HAS AFFECTED PRICES AND RETURNS IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY JULY 1998 – Congressional Budget Office, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/6xx/doc655/pharm.pdf

- The Economics of Generic Drug Shortages: The Limits of Competition, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.20241420

- Navigating pharma loss of exclusivity | EY – US, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/life-sciences/navigating-pharma-loss-of-exclusivity

- Improving Medication Adherence and Patient Experience by Researching Patient Perceptions of Generic Drugs | FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/improving-medication-adherence-and-patient-experience-researching-patient-perceptions-generic-drugs

- FYs 2013 – 2017 Regulatory Science Report: Analysis of Generic Drug Utilization and Substitution | FDA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/fys-2013-2017-regulatory-science-report-analysis-generic-drug-utilization-and-substitution

- Generics 2030: Three strategies to curb the downward spiral – KPMG International, accessed August 1, 2025, https://kpmg.com/us/en/articles/2023/generics-2030-curb-downward-spiral.html

- Generic Competition for Drugs Treating Rare Diseases | Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-law-medicine-and-ethics/article/generic-competition-for-drugs-treating-rare-diseases/41C8B4B54624B2477E3258AD9EA8AA71

- Off-Patent Generic Medicines vs. Off-Patent Brand Medicines for Six Reference Drugs: A Retrospective Claims Data Study from Five Local Healthcare Units in the Lombardy Region of Italy – PubMed Central, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3867455/

- Off-Patent Drugs That Lack Generic Competition Can Be Costly – Pharmacy Times, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/off-patent-drugs-that-lack-generic-competition-can-be-costly

- Why do some drugs not have generics? – WiseRxcard, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.wiserxcard.com/why-do-some-drugs-not-have-generics/