Executive Summary: The Transatlantic Bifurcation

The global life sciences industry stands at a critical juncture, navigating a bipolar regulatory order that has fundamentally shifted the calculus of innovation, investment, and market entry. For decades, the strategic narrative for pharmaceutical and medical device companies was relatively balanced: the United States offered the promise of high pricing and rapid uptake, while Europe offered a predictable, albeit fragmented, path to approval—particularly for medical devices, where the CE Mark was often faster to obtain than the FDA’s Premarket Approval. As we traverse 2024 and look toward 2025, that equilibrium has shattered. A profound inversion is reshaping the industry, driven by divergent policy choices that have widened the Atlantic into a regulatory chasm.

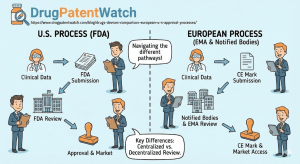

On one shore, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) operates as a monolithic federal agency, wielding centralized authority and a dual mandate that increasingly favors speed and innovation, particularly in oncology and rare diseases. Supported by robust user fees and a legislative framework designed to accelerate access, the U.S. has cemented its status as the premier “first-launch” market. However, this accessibility is now paired with the looming specter of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which fundamentally alters the long-term profitability horizon through mandatory price negotiations.

On the opposing shore, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) functions not as a unitary regulator but as the conductor of a complex orchestra of 27 National Competent Authorities (NCAs). While scientifically rigorous, the European system is currently besieged by structural transformations. The implementation of the Clinical Trials Regulation (CTR) has introduced transitional friction, while the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) has precipitated a full-blown crisis in the medtech sector, driving innovation offshore. Furthermore, the upcoming Joint Clinical Assessment (JCA) under the new Health Technology Assessment (HTA) regulation threatens to add a fourth hurdle to market access, potentially delaying patient availability even after regulatory approval.

This report provides an exhaustive, forensic analysis of these two distinct ecosystems. It is designed for the business professional who views regulatory affairs not merely as compliance, but as a lever for competitive advantage. We dissect the structural nuances, the widening gap in approval timelines, the labyrinthine differences in patent linkage and exclusivity, and the emerging battlegrounds of reimbursement. By understanding these dynamics, organizations can engage in strategic regulatory arbitrage—optimizing their capital allocation to exploit the strengths and mitigate the risks of each jurisdiction.

How Do the Structural DNA and Legal Mandates of the FDA and EMA Fundamentally Diverge?

To navigate the regulatory landscape effectively, one must first understand the architectural differences between the two agencies. While both the FDA and EMA share a primary mission of protecting public health, their operational mechanics, funding models, and legal authorities act as distinct gears turning at different speeds.

The FDA: A Unitary Federal Monolith

The FDA acts as a singular, centralized federal agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Its authority is derived from the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), giving it direct jurisdiction over the entire United States market.1

- Centralized Command: When a sponsor submits a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA), the review is conducted entirely by federal employees within the FDA’s specialized centers: the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), or the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH).1

- Decision-Making Power: The FDA possesses the ultimate authority to approve or deny a product. Once the agency issues an approval letter, the product is immediately legal to market across all 50 states. There is no political ratification step required.

- Funding and Speed: The FDA is heavily supported by industry user fees (PDUFA for drugs, MDUFA for devices), which mandate strict performance goals. This financial structure has created a culture of “clock-watching,” where review deadlines are statutorily defined and rigorously tracked.3

The EMA: A Networked Coordinator

In stark contrast, the EMA is a decentralized body established to coordinate the scientific resources of the European Union’s Member States. It does not employ the thousands of scientists who conduct the primary reviews. Instead, it relies on a network of over 4,500 experts drawn from national agencies such as Germany’s BfArM, France’s ANSM, and Sweden’s MPA.1

- The Committee System: The core of the EMA is its committees, most notably the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). For any given application, the CHMP appoints a “Rapporteur” and a “Co-Rapporteur” from different countries to lead the assessment. This ensures geographical balance but requires intense coordination and consensus-building among 27 nations.4

- The Political Gap: Crucially, the EMA does not approve drugs. It issues a “positive opinion.” This scientific recommendation is then forwarded to the European Commission (EC), the political executive of the EU. The EC typically takes 67 days to convert this opinion into a legally binding Marketing Authorization valid throughout the EU and EEA (European Economic Area).5 This built-in administrative lag is a structural disadvantage in the race for speed.

- Jurisdictional Limits: While the Centralized Procedure allows for a single authorization valid across the EU, the EMA has no authority over pricing or reimbursement. A drug may be “approved” in Europe but effectively unavailable in many countries until national pricing negotiations are concluded—a process that can take years.6

Table 1: Structural Comparison of Regulatory Authorities

| Feature | FDA (United States) | EMA (European Union) |

| Legal Basis | Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) | Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 & Directive 2001/83/EC |

| Jurisdiction | Single Market (USA) | 27 Member States + EEA (Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein) 1 |

| Review Workforce | Federal Employees (Centralized) | Network of National Experts (Decentralized) |

| Final Authority | FDA Commissioner (Delegated to Centers) | European Commission (Political Body) following Scientific Opinion |

| Scope | Drugs, Biologics, Devices, Food, Tobacco, Cosmetics | Human & Veterinary Medicines (Device role is limited to consultation) 3 |

| Language | English (Single) | English for assessment; Labeling/Packaging in 24+ languages 1 |

| Review Clock | Continuous (User Fee goals) | Active time + “Clock Stops” for questions (can last months) 1 |

The Implications of Scope

The difference in scope is also profound. The FDA regulates everything from lasagna to lasers, creating a holistic, albeit massive, bureaucracy. The EMA’s remit is strictly medicines. Medical devices in Europe are regulated not by the EMA, but by a decentralized system of Notified Bodies overseen by Competent Authorities, a distinction that has led to significant divergence in the medtech sector, which we will explore in depth later.3

Why Has the United States Become the Undisputed “First-Launch” Market for Novel Therapeutics?

Time is the most valuable currency in the pharmaceutical industry. The “patent clock” begins ticking the moment a molecule is patented, often years before clinical trials commence. Every day spent in regulatory review is a day of lost exclusivity revenue. In 2024, the data is unequivocal: the United States is the primary destination for innovation.

The Quantitative Lead: 2024 Scorecard

The gap in novel drug approvals highlights the U.S. dominance. In 2024, the FDA’s CDER approved 50 novel drugs (New Molecular Entities and novel biologics), while the EMA authorized 46 new active substances.8 While the raw counts appear comparable, the timing tells the true story.

Industry Insight: “68% of FDA’s novel drugs in 2024 were approved in the U.S. before any other country. When EU approval came first, it beat the FDA by a median of 11 months, but when U.S. approval came first, it was often by a wider strategic margin in key therapeutic areas.” — Pharmaceutical Technology & Pink Sheet Analysis.8

This “U.S. First” phenomenon is driven by several factors:

- Market Economics: The U.S. remains the world’s largest pharmaceutical market by value, offering free pricing (historically) and rapid uptake, incentivizing companies to prioritize the NDA/BLA submission over the MAA.

- Review Efficiency: The median approval time for the FDA is typically around 10 months for standard review and 6 months for priority review. The EMA’s standard timeline is 210 active days, but when administrative pauses (clock stops) and the EC decision phase are added, the “time to market” frequently stretches to 12-15 months.2

The Oncology Gap: A Case Study in Speed

Nowhere is the disparity more visible than in oncology, the largest and most competitive therapeutic area.

A longitudinal study published in JCO Global Oncology analyzed approvals from 2010 to 2024. The findings reveal a persistent lag in European access to cancer therapies.

- From 2019 to 2024, the FDA approved 199 new solid tumor indications.

- The EMA approved the same indications a median of 181 days later—a six-month delay that translates to thousands of patients waiting for life-extending treatments.11

This gap is exacerbated by the FDA’s aggressive use of Accelerated Approval, which allows drugs to enter the market based on surrogate endpoints (e.g., tumor shrinkage or progression-free survival) rather than overall survival data. The EMA has a similar mechanism, Conditional Marketing Authorization (CMA), but applies it more conservatively, often requiring more mature data packages before granting the green light.12

The Neuroscience Divide

The divergence was starkly illustrated in 2024 with the approval of new Alzheimer’s treatments.

- Kisunla (donanemab): Approved by the FDA in July 2024. As of late 2024, the EMA was still reviewing the file.8

- Leqembi (lecanemab): Approved by the FDA well in advance of the EMA, which approved it in late 2024, more than a year later.

For companies developing therapies in complex, high-risk indications like neurology, the FDA’s willingness to engage in nuance regarding risk-benefit profiles makes it the preferred initial jurisdiction.

How Do Clinical Trial Regulations Impact the Speed of R&D Innovation?

Before a drug can be approved, it must be tested. The regulatory environment for clinical trials is the upstream determinant of downstream success. Here, Europe is currently struggling through a painful transition.

The EU Clinical Trials Regulation (CTR) Implementation

Historically, clinical trials in Europe were governed by the Clinical Trials Directive (CTD), which required sponsors to apply separately to the NCA and Ethics Committee of each country where they wished to run a site. This fragmentation was a logistical nightmare for multinational trials.

To fix this, the EU introduced the Clinical Trials Regulation (CTR), fully applicable since January 2022. The centerpiece is the Clinical Trials Information System (CTIS), a single portal for submitting applications across all Member States.1

The Transition Crisis (2024-2025):

- The Deadline: A mandatory deadline was set for January 31, 2025, requiring all ongoing trials approved under the old Directive to be transitioned to the new CTR/CTIS system.14

- The Bottleneck: The transition has been fraught with technical glitches and administrative burdens. Sponsors, particularly smaller biotechs and academic institutions, found the new system complex. By late 2024, a rush of transition applications clogged the system, raising fears that some ongoing trials might be forced to halt if they missed the cut-off.15

- Innovation Impact: During this chaotic period, the number of clinical trial starts in Europe, particularly for early-phase (Phase I) studies, has declined relative to the U.S. and Asia. The uncertainty and administrative “teething pains” of the CTR have driven some sponsors to initiate trials in the U.S. or Australia to avoid the European bureaucratic flux.16

The U.S. IND System: Stability and Speed

In contrast, the U.S. system operates on the Investigational New Drug (IND) application.

- The 30-Day Rule: Once a sponsor submits an IND, the FDA has 30 days to object. If they do not object, the trial can proceed. This “passive approval” mechanism is incredibly fast and efficient compared to the active authorization required in Europe.1

- Centralized Oversight: While the U.S. uses local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), the regulatory oversight is unified under the FDA, providing a stable and predictable environment for trial initiation.

Table 2: Clinical Trial Regulatory Frameworks

| Feature | U.S. (IND) | EU (CTR/CTIS) |

| Application Mechanism | Investigational New Drug (IND) | Clinical Trial Authorization (via CTIS portal) |

| Approval Process | Passive: Proceed if no objection within 30 days | Active: Requires coordinated assessment and authorization |

| Jurisdiction | Federal (one application) | Unified EU assessment (one application, but member state involvement) |

| Transparency | ClinicalTrials.gov (results required) | CTIS public database (high transparency requirements) |

| Current Status | Stable, mature system | Transition phase; administrative hurdles high until 2025 |

What Are the Nuances of Expedited Pathways: Breaking Down the Speed of Access?

Both the FDA and EMA recognize that standard review timelines are too slow for life-threatening conditions. They have developed “expedited pathways” to speed effective drugs to patients. While the goals are aligned, the mechanisms differ significantly in eligibility and execution.

FDA: A Toolkit of Speed

The FDA offers four distinct pathways, which can often be used in combination:

- Fast Track: Facilitates the development and speeds the review of drugs for serious conditions with unmet needs. It allows for “rolling review,” where sections of the application are submitted as they are completed.

- Breakthrough Therapy Designation (BTD): The “gold standard.” Requires preliminary clinical evidence indicating the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy. It grants intensive FDA guidance and organizational commitment from senior managers.12

- Priority Review: Shortens the review clock target from 10 months to 6 months.

- Accelerated Approval: Allows approval based on a surrogate endpoint (e.g., biomarkers) that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. This is the primary engine of oncology innovation in the U.S.

EMA: Rigor Over Speed?

The EMA has streamlined its options but remains more selective:

- PRIME (Priority Medicines): Launched in 2016 to mirror the FDA’s Breakthrough Designation. It offers enhanced support and early dialogue for medicines targeting unmet medical needs. Eligibility is strict, and acceptance rates are lower than for FDA Breakthrough status.12

- Accelerated Assessment: Reduces the active review time from 210 days to 150 days. However, this is difficult to maintain; if the sponsor encounters significant questions during the review, the timeline often reverts to the standard timeframe.

- Conditional Marketing Authorization (CMA): The EU equivalent of Accelerated Approval. It is valid for one year and renewable. The key difference is that the EU often requires a more comprehensive data package upfront than the FDA does for Accelerated Approval.

The “Clock Stop” Factor:

A critical nuance in European timelines is the “clock stop.” The 210-day review cycle refers only to the days the EMA is actively reviewing. It does not include the time the clock is paused while the sponsor answers the “Day 120 List of Questions.” These stops can last for months, meaning a “210-day” procedure often takes 12 to 15 calendar months. The FDA’s PDUFA dates are calendar deadlines that are rarely missed or extended without major cause, providing greater predictability for investors.1

Is the European Medical Device Sector Facing an Existential Crisis Under MDR?

If the drug gap is a divide, the medical device gap is a chasm. The implementation of the European Medical Device Regulation (MDR) and In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) has triggered a crisis of availability and innovation in Europe, fundamentally reversing the historical flow of medtech market entry.

The Great Migration: From EU-First to US-First

For decades, the “CE Mark” was the first goal for medtech companies. It focused on safety and performance, whereas the FDA required efficacy. Companies would launch in Europe, generate revenue and real-world data, and then use that to fund the more expensive FDA approval.

The MDR, fully applicable since May 2021, has obliterated this advantage.

- Recertification Mandate: The MDR required not just new devices, but all legacy devices previously approved under the old Directives (MDD), to be recertified with new clinical evidence.

- The Notified Body Bottleneck: The infrastructure to support this—the Notified Bodies (independent auditing organizations designated by Member States)—was largely unprepared. Many Notified Bodies closed down rather than face the new stringent requirements, shrinking capacity just as the workload tripled.

- Clinical Evidence Bar: The MDR raised the bar for clinical data to near-pharma levels. “Equivalence” (claiming your device is safe because it’s like an existing one) became nearly impossible to prove without access to the competitor’s proprietary technical files.17

The FDA’s Competitive Edge: 510(k) Stability

While Europe churned, the FDA maintained its predictable 510(k) pathway.

- 510(k) Pathway: For moderate-risk (Class II) devices, manufacturers can obtain clearance by demonstrating “substantial equivalence” to a predicate device. This process typically takes 3-6 months and costs roughly $20,000 in user fees (for small businesses).

- MDR Reality: In contrast, obtaining CE marking under MDR for a similar device can now take 18-24 months and cost upwards of $500,000 to $2 million due to Notified Body fees and clinical data generation.17

Statistical Reality: “Since the application of the Regulations, fewer respondents are choosing Europe as the place to first-launch their devices… In the MD sector, choice of the EU as the first launch geography has dropped by 33% for large manufacturers.” — MedTech Europe Survey 2024.18

The Orphan Device Crisis

The crisis is most acute for “orphan devices”—those treating rare conditions or pediatric populations. The high cost of MDR compliance makes these low-volume products economically unviable in Europe. We are seeing a wave of “legacy device” withdrawals, where manufacturers simply stop selling established products in the EU because the cost of recertification exceeds the potential revenue. The FDA’s Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE) offers a safety valve for these products in the U.S. that Europe currently lacks.7

Table 3: Medical Device Approval Comparison

| Feature | FDA (United States) | EU (MDR/IVDR) |

| Primary Pathway | 510(k) (Substantial Equivalence) | Conformity Assessment (CE Mark) |

| Reviewer | FDA (CDRH) | Notified Bodies (Private entities) |

| Timeline (Class II) | 3-6 months (Average) | 12-18+ months |

| Cost | Low ($20k fee + testing) | High ($100k-$1M+ in fees & trials) |

| Clinical Data | Not required for most 510(k)s | Required for almost all Class III & implants |

| Database | MAUDE (Adverse Events) | EUDAMED (Registration, Vigilance – rolling out) |

| Market Trend | Inflow (First Launch Market) | Outflow (Innovation moving to US) |

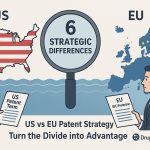

How Do Intellectual Property Frameworks and Patent Linkage Define Market Exclusivity?

For business development teams and investors, the “freedom to operate” is as critical as regulatory approval. The mechanisms for protecting intellectual property (IP) and the barriers to generic entry differ radically between the jurisdictions. This is where strategic intelligence becomes paramount.

The U.S. System: The Orange Book and Patent Linkage

The U.S. system is defined by Patent Linkage. This creates a hard legal connection between the regulatory approval of a generic drug and the patent status of the originator.

- The Orange Book: The FDA maintains this publication (formally Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations). Originators must list patents covering the drug substance, product, or method of use.19

- Hatch-Waxman & Paragraph IV: If a generic manufacturer files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) and challenges a listed patent (a “Paragraph IV certification”), the originator can sue.

- The 30-Month Stay: This lawsuit triggers an automatic 30-month stay on the FDA’s approval of the generic. This buys the originator valuable monopoly time regardless of the patent’s ultimate validity strength.20

Competitive Intelligence Tool: In this high-stakes environment, platforms like DrugPatentWatch are indispensable. By aggregating Orange Book data, litigation histories, and patent expiry timelines, DrugPatentWatch allows competitive intelligence teams to predict “Loss of Exclusivity” (LOE) events with precision, identifying when the “patent thicket” might actually be penetrable.21

The EU System: SPCs and No Automatic Linkage

Europe does not have an Orange Book, nor does it have automatic patent linkage.

- Regulatory Independence: A generic company can obtain Marketing Authorization from the EMA even if a valid patent exists. The regulator does not police IP. Launching the product, however, puts the generic “at risk” of patent infringement lawsuits in national courts.23

- SPCs (Supplementary Protection Certificates): Since European patents have a 20-year term that often erodes during clinical trials, the SPC extends protection by up to 5 years (plus 6 months for pediatric studies). This is roughly equivalent to the U.S. Patent Term Extension (PTE) but is granted nationally, meaning a drug might lose protection in France while remaining protected in Germany.19

- Data Exclusivity (8+2+1): The EU relies heavily on regulatory exclusivity:

- 8 Years: Data Exclusivity (Generic cannot reference originator data).

- +2 Years: Market Exclusivity (Generic can file but cannot sell).

- +1 Year: Additional year for a new indication with significant clinical benefit.

- Note: The proposed revision to EU Pharmaceutical Legislation threatens to modulate this, potentially reducing the baseline protection to 6 years to force wider launch access, a move heavily criticized by industry.24

The SPC Manufacturing Waiver

A unique feature of the EU system is the SPC Manufacturing Waiver, introduced in 2019. This allows EU-based generic and biosimilar manufacturers to produce medicines during the SPC protection period, provided the production is solely for export to non-EU countries where protection has expired, or for stockpiling during the final 6 months of the SPC to prepare for “Day 1” launch in the EU. The U.S. has no direct equivalent, relying instead on the Bolar exemption which covers R&D but not commercial stockpiling.26

How Are Reimbursement Gatekeepers Rewriting the Rules of Profitability?

Regulatory approval is merely the ticket to the dance; reimbursement is the invitation to the floor. The dynamics here are shifting tectonically due to the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the EU’s incoming Joint Clinical Assessment (JCA).

United States: The End of Free Pricing?

Historically, the U.S. was a free-pricing market. CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) was statutorily barred from negotiating drug prices.

- The Shift: The IRA now mandates price negotiations for high-spend drugs in Medicare. The first 10 negotiated prices (e.g., Eliquis, Jardiance) were published in 2024, to take effect in 2026. Negotiated prices are significantly lower (minimum 38% off list).28

- Impact: While still the most lucrative market, the “unlimited upside” of the U.S. is being capped. However, U.S. launch prices remain 3x-9x higher than in Europe.29

Europe: The HTA Gauntlet and the JCA

In Europe, approval is followed by a grueling country-by-country HTA process.

- Germany (AMNOG): Historically the “first launch” market because companies could launch freely for 12 months before the negotiated price kicked in. This “free period” has been slashed to 6 months, tightening the revenue window.30

- EU HTA Regulation (JCA): Starting January 2025, the EU will implement Joint Clinical Assessments for oncology drugs and ATMPs (Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products).

- The Fear: Instead of replacing national HTAs, the JCA might become an additional bureaucratic layer. Member States must consider the JCA report but retain the right to demand extra data for their specific national context (e.g., specific comparators).31

- The PICO Problem: The JCA requires defining “Populations, Interventions, Comparators, and Outcomes” (PICO). If the EU consensus PICO differs from the clinical trial design (e.g., wrong comparator), the JCA report could be negative, poisoning access across all 27 countries.32

Comparative Time to Access:

- U.S.: Average time from approval to reimbursement (insurance coverage) is ~9 months.

- Germany: ~7.4 months (fastest in EU).

- France: ~12.9 months.

- England: ~17.7 months.33

What Are the Critical Differences in Post-Market Surveillance and Lifecycle Management?

The responsibility of a manufacturer does not end at approval. Post-market requirements are becoming increasingly stringent in both regions, though the tools differ.

Risk Management: REMS vs. RMP

- FDA REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies): The FDA can mandate a REMS for drugs with serious safety concerns. This might include a Medication Guide, a communication plan to doctors, or “Elements to Assure Safe Use” (ETASU), such as requiring doctors to be certified to prescribe the drug or registries for patients. REMS are product-specific and legally enforceable.35

- EMA RMP (Risk Management Plan): The EMA requires an RMP for every new medicine, not just high-risk ones. The RMP details the safety profile, how risks will be minimized, and plans for further studies (Post-Authorization Safety Studies – PASS). While broad, the RMP is a living document updated throughout the product’s life.35

Device Vigilance: MAUDE vs. EUDAMED

- U.S. MAUDE: The Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database is the FDA’s repository for adverse event reports. It is publicly searchable and has been the gold standard for device vigilance.

- EU EUDAMED: The European Databank on Medical Devices (EUDAMED) is the new backbone of the MDR. It is designed to be a comprehensive portal for registration, UDI (Unique Device Identification), clinical investigations, and vigilance. However, its rollout has been delayed for years. While some modules are active, full mandatory use has been pushed back, forcing manufacturers to operate in a hybrid state of old and new reporting systems.36

Post-Market Clinical Follow-up (PMCF)

Under the EU MDR, “Post-Market Clinical Follow-up” is not optional. Manufacturers must proactively collect clinical data on their devices for the lifetime of the device. This is a massive shift from the “passive vigilance” (waiting for complaints) that characterized the old MDD era and still largely characterizes lower-risk device regulation in the U.S..38

How Do Biosimilars and Generics Navigate the Competitive Landscape?

The battle for market share after the “patent cliff” is fierce. Here, Europe has historically led, but the U.S. is catching up.

Interchangeability: The U.S. Gold Standard

In the U.S., the FDA distinguishes between a “Biosimilar” (no clinically meaningful difference) and an “Interchangeable Biosimilar.” An interchangeable product can be substituted by a pharmacist without the prescriber’s intervention (subject to state law). Achieving this designation often requires additional “switching studies,” raising the development bar. In 2024, the FDA approved a record number of biosimilars, and the “interchangeable” distinction is becoming a major commercial weapon.39

The European Approach: Default Substitution

The EMA does not use the “interchangeable” regulatory designation in the same way. Instead, the EMA and the Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA) issued a joint statement confirming that biosimilars approved in the EU are essentially interchangeable. However, the actual decision to allow pharmacy-level substitution lies with the individual Member States. This creates a patchwork of substitution laws across Europe, unlike the more uniform (though legally complex) U.S. system.3

Market Uptake

Europe generally sees faster and deeper uptake of biosimilars due to national tenders and quotas. In the U.S., the “Rebate Wall”—where originator companies offer massive rebates to insurers to keep biosimilars off formularies—has historically slowed uptake. However, the IRA and recent competitive shifts are beginning to erode these walls.40

What Role Does International Collaboration Play in Bridging the Transatlantic Gap?

In a fragmented world, regulators are attempting to stitch together alliances to speed up global access, though success is uneven and heavily skewed toward the FDA’s orbit.

Project Orbis: The Oncology Fast Lane

Initiated by the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE), Project Orbis allows for the concurrent submission and review of oncology products among international partners.

- The Coalition: The alliance includes the FDA, Australia (TGA), Canada (Health Canada), the UK (MHRA), Switzerland (Swissmedic), Brazil (ANVISA), Singapore (HSA), and Israel (MOH).

- The Notable Absence: The EMA is not a partner in Project Orbis; it participates only as an observer. This highlights the structural rigidity of the EU system. The EMA’s centralized procedure, bound by treaty timelines and the need for 27-state consensus, cannot legally flex to match the real-time, fluid data exchange of the FDA and its Orbis partners.

- The Result: Patients in Orbis countries often receive access to new cancer therapies months before patients in the EU, creating a “two-speed” Western world for oncology care.41

Harmonization in Devices (IMDRF)

The International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) attempts to harmonize device regulation globally.

- MDSAP: The Medical Device Single Audit Program allows a single quality audit to satisfy the requirements of the U.S., Canada, Japan, Brazil, and Australia.

- EU Isolation: The EU is not a full participant in MDSAP for regulatory purposes. The MDR’s unique requirements for Notified Bodies and clinical data mean that a European audit cannot easily be substituted for an MDSAP audit, and vice versa. This leaves Europe as an outlier, increasing the duplicate burden for manufacturers.43

Conclusion & Key Takeaways

The regulatory landscape of 2024/2025 is defined by divergence. The transatlantic partnership, while rooted in shared scientific values, has split into two distinct operational realities.

For the pharmaceutical executive, investor, or legal counsel, the implications are clear:

- The “US First” Strategy is Dominant: For both drugs and devices, the United States has cemented its position as the primary launch market. The FDA’s speed, combined with the paralysis of EU Notified Bodies (MDR) and slower oncology reviews (EMA), makes the U.S. the logical first step for revenue generation.

- Regulatory Divergence is Widening: Despite rhetoric about harmonization, the gap is growing. Project Orbis proves the FDA can move faster with agile partners than the EMA can with its treaty-bound consensus model. The EU MDR has created a separate, heavy-burden ecosystem for devices that is driving innovation away.

- Patent Strategy Requires Local Nuance: There is no “global” patent strategy. The U.S. requires aggressive Orange Book listing and litigation readiness (Hatch-Waxman). The EU requires a focus on SPC management and maneuvering around the lack of patent linkage. Tools like DrugPatentWatch are essential for bridging these distinct intelligence gaps.

- Reimbursement is the New Regulator: In both regions, the payer now holds the ultimate veto. In the U.S., it’s the IRA negotiation list; in the EU, it’s the looming Joint Clinical Assessment (JCA). Success requires generating evidence that satisfies both the regulator (Safety/Efficacy) and the payer (Value/PICO)—often a conflicting demand.

- Europe’s “Innovation Flight” is Real: The data confirms a decline in EU clinical trial starts and device launches. Unless the EU simplifies the CTR/MDR implementation and ensures the JCA does not become a “fourth hurdle,” this investment drain toward the U.S. will accelerate.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Can we use FDA clinical data to satisfy EU MDR requirements for medical devices?

A: Not easily. While the FDA accepts “predicate device” data (claiming equivalence to a predecessor) for 510(k) clearance, the EU MDR imposes strict equivalence criteria. You must have access to the technical documentation of the equivalent device to claim equivalence in Europe. Since competitors rarely share this proprietary data, most manufacturers cannot use FDA predicate logic for MDR compliance. They are forced to conduct new, specific clinical investigations (PMCF studies) for the EU, significantly driving up costs and timelines.17

Q2: How will the EU Joint Clinical Assessment (JCA) starting in 2025 affect my launch timeline?

A: It creates a parallel workstream that adds risk to market access. You must submit your JCA dossier at the same time as your EMA Marketing Authorization Application. The risk is not necessarily a delay in regulatory approval, but a delay in reimbursement. If the JCA report (published 30 days after the EC approval) concludes that your clinical trial comparator was invalid based on the EU’s PICO scoping, national payers (like in France or Germany) may use this negative assessment to delay or deny reimbursement negotiations, effectively stalling your commercial launch despite having a license.31

Q3: Why doesn’t the EMA join Project Orbis to speed up cancer drug approvals?

A: It is a structural and legal issue. The EMA’s Centralized Procedure has rigid, treaty-defined timelines (210 active days) and requires consensus among 27 national representatives. It lacks the legal flexibility to engage in the real-time, fluid data exchange and concurrent decision-making that Project Orbis requires. The EMA participates as an observer to stay informed but cannot legally synchronize its decision with the FDA, Australia, or Canada.45

Q4: Does the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) mean the end of orphan drug profitability?

A: No, but it complicates lifecycle management. Orphan drugs designated for only one rare disease are currently exempt from IRA price negotiations. However, if a drug is approved for a second orphan indication, it generally loses that exemption and becomes eligible for negotiation (and price cuts) once it has been on the market for 7 years (small molecules) or 11 years (biologics). This disincentivizes developing multiple indications for the same orphan molecule.29

Q5: What is the most effective way to monitor generic entry threats in the U.S. vs. Europe?

A: In the U.S., you must monitor the Orange Book for “Paragraph IV” certifications, which signal a generic challenge and trigger litigation. In Europe, because there is no patent linkage, there is no public “trigger” notification. You must diligently monitor SPC expiry dates and national patent litigation dockets in key countries (Germany, UK, France). Intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch are critical here, as they aggregate these disparate data sources (Orange Book, SPC filings, litigation records) into a single dashboard to forecast “Loss of Exclusivity” events globally.21

Works cited

- FDA vs. EMA: Key Differences in Drug Approval You Need to Know …, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.ecinnovations.com/blog/fda-vs-ema/

- FDA vs EMA: Key Regulatory Differences for Pharmaceuticals – LS Academy, accessed November 26, 2025, https://lsacademy.com/en/fda-vs-ema-key-regulatory-differences-for-pharmaceuticals/

- In-Depth Look at the Differences Between EMA and FDA – Mabion, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.mabion.eu/science-hub/articles/similar-but-not-the-same-an-in-depth-look-at-the-differences-between-ema-and-fda/

- Centralized, Decentralized, Mutual Recognition, and National Procedures Explained: Choosing the Right EU Authorization Route – Pharma Regulatory, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.pharmaregulatory.in/centralized-decentralized-mutual-recognition-and-national-procedures-explained-choosing-the-right-eu-authorization-route/

- 2023 New Drug Approvals: Review of New FDA and EMA Marketing Authorisations, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.tribecaknowledge.com/blog/2023-new-drug-approvals-review-of-new-fda-and-ema-marketing-authorisations

- FDA vs EMA: what are the differences for market authorization? – Alhena Consult, accessed November 26, 2025, https://alhena-consult.com/differences-between-fda-and-ema-market-access/

- Medical devices | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/medical-devices

- FDA beats EMA to most approved new drugs in 2024 – Pharmaceutical Technology, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/fda-beats-ema-to-most-approved-new-drugs-in-2024/

- 2024 New Drug Therapy Approvals Annual Report – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/new-drug-therapy-2025-annual-report.pdf

- Pharma Looks To America First: US FDA Holds Overwhelming Lead Over EMA In Novel Approvals, accessed November 26, 2025, https://insights.citeline.com/PS154948/Pharma-Looks-To-America-First-US-FDA-Holds-Overwhelming-Lead-Over-EMA-In-Novel-Approvals/

- Review of All Solid Tumor Drug Approvals From 2019 to 2024 by US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, and Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency – ASCO Publications, accessed November 26, 2025, https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/GO-25-00326

- Accelerated Approval: A Comparative Analysis of EU and US Regulatory Pathways, accessed November 26, 2025, https://odelletechnology.com/accelerated-approval-a-comparative-analysis-of-eu-and-us-regulatory-pathways/

- EU’s Clinical Trials Regulation comes into full force, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/news/eus-clinical-trials-regulation-comes-into-full-force/

- Navigating Changes to EU Clinical Trial Management – QPS, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.qps.com/2024/03/13/navigating-changes-to-eu-clinical-trial-management-what-you-need-to-know/

- The intricacies of effectively transitioning active clinical trials to the EU Clinical Trial Regulation | pharmaphorum, accessed November 26, 2025, https://pharmaphorum.com/rd/intricacies-effectively-transitioning-active-clinical-trials-eu-clinical-trial-regulation

- Europe’s Clinical Trials are at a Crossroads (2026): How to Reverse the 12% Share, accessed November 26, 2025, https://odelletechnology.com/europes-clinical-trials-landscape-a-critical-juncture-amidst-u-s-retrenchment/

- EU MDR vs FDA: 2025 US-EU Medical Device Regulatory …, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.complizen.ai/post/eu-mdr-vs-fda-complete-regulatory-comparison-guide-2025

- MedTech Europe IVDR & MDR Survey Results 2024, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.medtecheurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/mte-ivdr-mdr-survey-report-highlights-march.2025.pdf

- The Atlantic Divide: 6 Strategic Differences in Pharmaceutical Patents Between the US and EU and How to Turn Them into Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-atlantic-divide-6-strategic-differences-in-pharmaceutical-patents-between-the-us-and-eu-and-how-to-turn-them-into-competitive-advantage/

- EU unlikely to follow US with ‘patent linkage’ system, says expert – Pinsent Masons, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/analysis/eu-unlikely-to-follow-us-with-patent-linkage-system-says-expert

- Competitive Intelligence in Excipients: How to Know Your Market Share in Every Drug, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/competitive-intelligence-in-excipients-how-to-know-your-market-share-in-every-drug/

- DrugPatentWatch has revolutionized our approach to identifying and seizing business opportunities, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/

- A Diverse Landscape of Patent Issues Seen in the US, UK, and the EU, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.biopharminternational.com/view/diverse-landscape-patent-issues-seen-us-uk-and-eu

- Note for the rapporteurs/shadow rapporteurs of the EU Pharmaceutical legislation: Impact of extending the duration of regulatory data protection in – Medicines for Europe, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.medicinesforeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/MEMO-_-Impact-of-the-prolonged-exclusivites-.pdf

- Revision of the General Pharmaceutical Legislation: Impact Assessment of European Commission and EFPIA proposals, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.efpia.eu/media/msadqxbf/revision-of-the-general-pharmaceutical-legislation-gpl-impact-assessment.pdf

- European SPC Manufacturing Waiver Goes into Force – McDermott Will & Schulte, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.mwe.com/insights/european-spc-manufacturing-waiver-goes-into-force/

- Supplementary protection certificates for pharmaceutical and plant protection products – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, accessed November 26, 2025, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/strategy/intellectual-property/patent-protection-eu/supplementary-protection-certificates-pharmaceutical-and-plant-protection-products_en

- Negotiated Prices Take Effect for Ten Drugs in 2026 – Medicare Rights Center, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.medicarerights.org/medicare-watch/2025/10/09/negotiated-prices-take-effect-for-ten-drugs-in-2026

- How IRA Negotiations Are Shaping US-EU Drug Price Differentials – Inbeeo, accessed November 26, 2025, https://inbeeo.com/2025/03/26/ira-us-eu-drug-pricing-impact/

- Benefit-driven pricing: How AMNOG strikes a balance between the financial burden on statutory health insurance and reimbursement of innovative medications in Germany | Cencora, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.cencora.com/resources/pharma/htaq-summer-2024-how-amnog-strikes-a-balance

- EU Joint Clinical Assessment: Key Steps for Pharma in 2025 – Trinity Life Sciences, accessed November 26, 2025, https://trinitylifesciences.com/blog/eu-jca-companies-need-to-know/

- EU HTA Regulation Joint Clinical Assessments: Ready for January 2025?, accessed November 26, 2025, https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue/august-2024/eu-hta-regulation-are-you-ready-for-2025-joint-clinical-assessment/

- Study: Approval-to-reimbursement times in the US vs. Europe – Lyfegen, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.lyfegen.com/post/study-approval-to-reimbursement-times-in-the-us-vs-europe

- Timeframe of Drug Approval to Reimbursement Lags in US Compared With Europe | AJMC, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/timeframe-of-drug-approval-to-reimbursement-lags-in-us-compared-with-europe

- EMA & FDA: What Are the Similarities & Differences in Risk Management Procedures?, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.biomapas.com/ema-and-fda-risk-management/

- The EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR): What changes? – VDE, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.vde.com/topics-en/health/consulting/the-eu-medical-device-regulation-mdr-what-changes

- Implementation of the Regulation on health technology assessment, accessed November 26, 2025, https://health.ec.europa.eu/health-technology-assessment/implementation-regulation-health-technology-assessment_en

- (PDF) Comparative Study of EU MDR vs. FDA Requirements for Post-Market Surveillance in Class III Medical Devices – ResearchGate, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/395770323_Comparative_Study_of_EU_MDR_vs_FDA_Requirements_for_Post-Market_Surveillance_in_Class_III_Medical_Devices

- CDER Brings Many Safe and Effective Therapies to Patients and Consumers in 2024 | FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/cder-brings-many-safe-and-effective-therapies-patients-and-consumers-2024

- (PDF) The Dual Barriers to Biosimilar Competition: A Comparative Analysis of US Patent Thickets and EU Supplementary Protection Certificates – ResearchGate, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397367075_The_Dual_Barriers_to_Biosimilar_Competition_A_Comparative_Analysis_of_US_Patent_Thickets_and_EU_Supplementary_Protection_Certificates

- Project Orbis – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-orbis

- Project Orbis | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.tga.gov.au/about-us/international-engagements/project-orbis

- IMDRF Strategic Plan 2021-2025 – Progress Report Card, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.imdrf.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/IMDRF%20Strategic%20Plan%202021-2025%20Progress%20Report%20Card%20%28N78%29.pdf

- CDRH International Affairs – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/cdrh-international-affairs

- International Regulatory Collaboration: Project Orbis Update – FDA, accessed November 26, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/174242/download

- Medicare drug price negotiation: The complexities of selecting therapeutic alternatives for estimating comparative effectiveness – PubMed Central, accessed November 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10909583/