Executive Summary

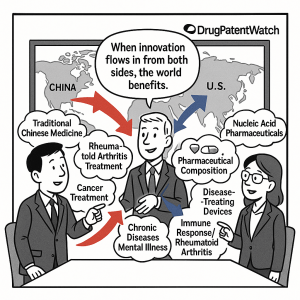

The global intellectual property landscape is increasingly defined by the strategic interplay and fundamental divergences between the patent systems of the United States and the People’s Republic of China. This report provides an exhaustive comparative analysis of these two systems, designed to equip corporate counsel, intellectual property (IP) strategists, and government policy advisors with the nuanced understanding required to navigate this complex terrain. The analysis reveals a core dichotomy: the U.S. system, a mature, constitutionally-rooted framework built on the protection of private property rights, is currently undergoing significant internal debate regarding the scope and certainty of those rights. In contrast, China’s system has rapidly evolved from a nascent framework to a sophisticated and dynamic instrument of national industrial policy, prioritizing technological advancement and economic development.

This study delves into the foundational philosophies that shape each system’s architecture, from the U.S. emphasis on incentivizing individual inventors to China’s focus on promoting the collective exploitation of “invention-creations.” It provides a comparative profile of the administrative bodies—the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA)—highlighting how their distinct mandates and funding structures influence examination priorities and patent quality.

A critical examination of the types of patents available reveals key strategic tools, most notably China’s utility model patent, a fast-track protection mechanism often underutilized by foreign entities but which forms a cornerstone of domestic IP strategy and presents significant challenges for freedom-to-operate analyses. The report meticulously compares the patent prosecution journey, from application timelines and costs to the nuanced differences between the U.S. “obviousness” standard and China’s “inventive step” analysis.

The enforcement and litigation frameworks are dissected, contrasting China’s bifurcated system—where validity and infringement are decided in separate forums—with the unified proceedings in U.S. district courts. This analysis uncovers a strategic paradox: despite historical perceptions, China has emerged as a premier venue for patent enforcement, offering foreign plaintiffs high success rates, faster timelines, and a near-certainty of injunctive relief, transforming it from a perceived infringement haven into a potent tool for protecting global supply chains.

Sector-specific deep dives into pharmaceuticals and artificial intelligence (AI) illustrate how these systems are being leveraged to achieve distinct national goals. China’s pharmaceutical IP regime is engineered to alter global drug launch strategies and accelerate domestic access to innovation. In AI, China’s pursuit of patent volume contrasts with the U.S. focus on high-impact, foundational patents, reflecting divergent national strategies for technological dominance.

Finally, the report assesses the dynamic future of both systems. The U.S. is at a crossroads, with proposed legislation aiming to restore certainty to patent eligibility and strengthen enforcement mechanisms. China, meanwhile, is executing a deliberate shift from patent quantity to “high-quality” development, refining its IP system into a more potent instrument of state-led industrial policy. In this era of heightened geopolitical competition, IP strategy has become inseparable from geopolitical strategy, and understanding the profound differences between these two titans is no longer an academic exercise but a critical necessity for global innovation leadership.

Section 1: Foundational Philosophies and Legal Architecture

The patent systems of the United States and China, while sharing common terminology and participating in the same international treaties, are built upon profoundly different philosophical and legal foundations. These foundational principles are not merely historical artifacts; they actively shape the structure, procedures, and strategic utility of each system. The U.S. framework is fundamentally a rights-based system designed to protect private property, whereas the Chinese framework is a state-directed system designed to achieve national strategic objectives.

1.1 The U.S. System: Constitutional Origins and the Four Pillars of Patentability

The U.S. patent system is one of the oldest and most influential in the world, with its origins embedded directly in the nation’s founding document. Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution grants Congress the power “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries”.1 This constitutional mandate establishes two core principles that define the system’s character. First, the primary purpose is utilitarian: to promote societal progress. Second, the mechanism for achieving this is the granting of a temporary, exclusive right—a property right—to the inventor.1

This framework establishes the patent as a “quid pro quo”: in exchange for the inventor’s full public disclosure of the invention, the government grants a limited monopoly.2 This philosophy is deeply rooted in a belief in the power of individual incentive. A strong patent system provides the assurance that an inventor who takes significant risks to create a successful product can protect that idea and be rewarded for it, thereby encouraging investment in breakthrough technologies and fostering a dynamic innovation economy.1 The writings of the nation’s founders, including James Madison and George Washington, explicitly underscored the need for such a system to protect risk-takers in the new republic.1

To ensure that this powerful right is granted only to deserving inventions, U.S. patent law has developed four stringent requirements, often referred to as the “four pillars of patentability”.6 An invention must satisfy all four criteria to be granted a patent:

- Novelty: Codified in 35 U.S.C. § 102, this pillar requires that an invention be genuinely new. It cannot have been previously patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the patent application.2 This ensures that patents are granted for true innovations, not for reiterations of existing knowledge.

- Non-Obviousness: Governed by 35 U.S.C. § 103, this is often the most difficult hurdle. An invention must not have been obvious to a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (a hypothetical expert in the relevant field) at the time the invention was made.2 This pillar prevents the patenting of predictable combinations of known elements or straightforward advancements, reserving protection for significant and not readily foreseeable leaps in technology.7

- Utility: This requirement, found in 35 U.S.C. § 101, mandates that the invention must be useful. Specifically, it must possess a “specific, substantial, and credible utility”.6 This pillar ensures that patents are tied to practical, real-world applications and are not granted for purely theoretical or fanciful ideas that have no functional purpose.6

- Eligible Subject Matter: Also rooted in 35 U.S.C. § 101, this pillar defines the categories of what can be patented. The statute identifies four broad categories: processes, machines, articles of manufacture, and compositions of matter.6 Over time, the courts have carved out judicial exceptions to these categories, deeming laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas as ineligible for patent protection.9 This doctrine prevents the monopolization of the basic tools of scientific and technological work.

1.2 The Chinese System: Statutory Evolution and the Concept of “Invention-Creations”

In stark contrast to the U.S. system’s deep historical roots, China’s modern patent system is a relatively recent development, a product of its strategic decision to engage with the global economy. After a period in which patent rights were viewed as incompatible with socialist principles, China enacted its first Patent Law in 1984, which came into force on April 1, 1985.12 This was not a response to domestic demand for individual property rights but a key component of the “reform and opening-up” policy, designed to align with international norms, encourage technology transfer, and attract foreign investment.12

The system’s evolution has been driven by external milestones and international treaty obligations. China’s accession to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property in 1985, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) in 1994, and, most consequentially, the TRIPS Agreement upon joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, have necessitated major revisions to its patent law in 1992, 2000, 2008, and 2020.12

This history informs the foundational philosophy articulated in Article 1 of the Chinese Patent Law. Its purpose is not solely to reward the inventor but to serve a broader set of national goals: “to protect the lawful rights and interests of patentees, to encourage invention-creation, to promote the exploitation of invention-creation, to enhance innovation capability, and to promote the advancement of science and technology and the development of economy and society”.18 This reflects a more community-based cultural tradition that emphasizes social value and collective benefit over the protection of purely individual rights.4

The central legal concept in Chinese patent law is “invention-creations” (发明创造), a broad term that statutorily encompasses three distinct types of patent rights: inventions, utility models, and designs.16 The requirements for the highest tier, an “invention,” are defined in Article 22 of the Patent Law. An invention is a “new technical solution proposed for a product, a process or the improvement thereof”.18 To be patentable, an invention must possess the “three natures” (三性):

- Novelty (新颖性): The invention is new and has not been publicly disclosed in publications, used publicly, or made known to the public anywhere in the world before the filing date.20

- Creativity / Inventiveness (创造性): This is analogous to the U.S. non-obviousness standard. The invention must have “prominent substantive features and represent notable progress” compared to the prior art.12

- Practical Applicability / Industrial Applicability (实用性): The invention can be made or used and can produce positive effects.12

1.3 Comparative Insight: Individual Rights vs. National Strategy as Core Drivers

The foundational philosophies of each system are not merely academic; they are the root cause of the most significant structural and procedural divergences that define the strategic landscape for innovators. The differing telos, or ultimate purpose, of each system dictates its behavior and the tools it provides.

The U.S. system’s constitutional framing of patents as a private property right 1 necessitates a robust, adversarial judicial process to adjudicate those rights. If a patent is a form of property, then disputes over its boundaries (infringement) and legitimacy (validity) must be resolved through a legal system with strong procedural safeguards, which logically leads to the complex and discovery-heavy litigation model examined in Section 5. The system is designed from the bottom up, empowering individuals and firms with rights and then providing the legal arenas to defend them, with the belief that this aggregate activity will “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”

Conversely, China’s statutory mandate for patents to serve national development goals 18 logically gives rise to a top-down system designed as an instrument of state policy. This goal is better served by a framework that can grant rights quickly to domestic innovators to build market share and protect incremental advancements, even if those rights are less rigorously examined at the outset. This rationale directly explains the existence and strategic importance of the utility model system, a tool that prioritizes speed and accessibility over the certainty that comes with full substantive examination.21 The heavy involvement of administrative bodies in enforcement further aligns with a state-led model of economic management.

Consequently, an innovator’s engagement with each system demands a fundamentally different mindset. Approaching the USPTO is primarily a legal and technical challenge, requiring a robust defense of an invention’s merits against rigorous, precedent-based examination standards. Approaching CNIPA, while also requiring technical merit, involves an additional strategic layer: understanding how an invention aligns with China’s current industrial policy goals (e.g., leadership in AI, biotechnology, or green technology 23) and effectively leveraging the specific tools, like the dual-filing system, that the framework provides to support those national goals. Simply transposing a U.S. filing strategy to China, without appreciating this difference in purpose, is a recipe for suboptimal protection and missed strategic opportunities.

Section 2: The Gatekeepers: A Comparative Profile of the USPTO and CNIPA

The administrative agencies that grant patent rights—the USPTO in the United States and CNIPA in China—are far more than passive examination bodies. Their institutional mandates, organizational structures, and funding mechanisms directly influence examination quality, pendency times, and the overall strategic environment for applicants. The USPTO functions largely as a fee-funded service agency, while CNIPA operates as a powerful executive arm of China’s national industrial policy.

2.1 Mandate and Structure: The USPTO as a Fee-Funded Service Agency

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce.3 Its core, legally mandated function is to grant U.S. patents and register trademarks.5 While it plays an important advisory role to the President and other federal agencies on domestic and international IP policy, its primary operational focus is on the examination of applications.25

A defining characteristic of the USPTO is its unique funding structure. It is “unique among federal agencies because it operates solely on fees collected by its users, and not on taxpayer dollars”.3 This self-sustaining model creates a business-like operational dynamic: the USPTO receives requests for services in the form of patent and trademark applications and charges fees that are projected to cover the cost of performing those services.3 This structure creates an inherent tension. On one hand, the agency must maintain a high standard of examination to ensure the value and validity of the patents it issues, which are the “product” its users are paying for. On the other hand, it faces constant pressure to manage its budget, control pendency times, and process a large volume of applications efficiently to satisfy its “customers” and avoid crippling backlogs.3

2.2 Mandate and Structure: The CNIPA as an Instrument of National Industrial Policy

The China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA), which was reorganized from the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) in 2018, operates under the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR).28 Its mandate extends far beyond the examination and registration functions of the USPTO. CNIPA is a central actor in China’s state-led innovation strategy.

Its major responsibilities explicitly include 30:

- Formulating and Implementing National IP Strategy: CNIPA is tasked with creating the master plans, policies, and development goals for building China into an “intellectual property strength” and a global innovation leader.

- Protecting and Enforcing IP Rights: The agency drafts relevant laws and regulations and, crucially, is responsible for the “operational guidance of trademark and patent law enforcement”.30 This gives it a direct role in the enforcement ecosystem, a function that is entirely separate from the USPTO in the U.S. system.

- Fostering IP Use and Commercialization: CNIPA formulates policies to promote the transfer, licensing, and commercialization of IP, standardizing the evaluation of intangible assets and overseeing compulsory licensing.30

- Coordinating Foreign-Related IP Affairs: The agency is a key player in international IP negotiations and cooperation, advancing China’s interests on the global stage.28

CNIPA’s stated “Functional Shifts” further reveal its policy-driven nature. The agency is actively working to shorten registration times, improve examination quality, and, significantly, strengthen “credit supervision” to crack down on behaviors like “trademark squatting and abnormal patent application”.30 This latter function demonstrates its role as a regulator of behavior within the IP system, not just a neutral processor of applications.

2.3 Strategic Implications: How Agency Priorities Shape Examination and Policy

The differing mandates of the USPTO and CNIPA have profound strategic implications for innovators. The USPTO’s user-fee model creates a constant pressure to balance examination quality with operational efficiency. This can lead to long pendency times but also a generally high perception of U.S. patent quality and validity.3 Its policy influence is primarily external, focused on advocating for strong IP protection for U.S. companies in foreign markets.25

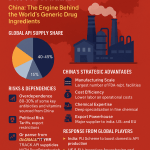

In contrast, CNIPA’s role as an executor of national strategy means its examination priorities can pivot rapidly to align with state directives. For years, Chinese industrial policy prioritized increasing the sheer quantity of patent filings to climb global rankings and demonstrate innovative capacity.32 This was supported by government subsidies for patent applications, leading to an explosion in filings, including many of low quality.33 More recently, as articulated in national strategies like the 14th Five-Year Plan, the focus has shifted decisively from quantity to “high-quality development”.35

This policy pivot is directly observable in CNIPA’s actions. The agency has instituted a vigorous crackdown on “abnormal” patent applications—defined as those not based on genuine inventive activity, such as fabricated or plagiarized applications filed merely to claim subsidies.38 This campaign, combined with the phasing out of subsidies, is the direct and predictable cause of the dramatic 29% drop in Chinese invention patent grants in the first half of 2025.40 This demonstrates that CNIPA operates not as a market-responsive service agency but as a powerful policy lever of the state.

Furthermore, the expansive role of CNIPA in post-grant activities creates a more integrated and state-controlled IP ecosystem in China. In the U.S., the USPTO’s role largely concludes upon the issuance of a patent, with enforcement falling to the separate judicial branch (federal courts and the ITC) and post-grant validity challenges handled by its quasi-judicial Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).27 This reflects a clear separation of executive and judicial powers. In China, CNIPA’s influence permeates the entire patent lifecycle. Its mandate to provide “operational guidance” for law enforcement means it oversees an administrative enforcement track that runs parallel to the judicial system.30 A patent holder in China can choose to file an infringement complaint with a local IP office (under CNIPA’s purview) rather than a court.43 This administrative route is typically much faster and cheaper than litigation and can result in an injunction to stop the infringing activity, although it generally does not award monetary damages.43 This offers a critical strategic option for patent holders that has no direct equivalent in the United States.

Section 3: The Anatomy of a Patent Right: A Typology of Protections

The types of patent protection available in the United States and China reflect their distinct economic histories and strategic priorities. While both countries offer protection for inventions and designs, China’s system includes a unique and strategically vital third category—the utility model patent—which has no direct counterpart in the U.S. and fundamentally alters the landscape for innovators and competitors.

3.1 U.S. Patent Types: Utility, Design, and Plant Patents

The U.S. patent system offers three distinct types of patents, each tailored to protect a specific form of innovation.8

- Utility Patents: Constituting approximately 90% of all patents issued by the USPTO, utility patents are the cornerstone of the U.S. system.46 They protect the functional aspects of an invention—how it works or is used. The scope of a utility patent covers “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof”.45 This broad definition encompasses everything from complex chemical compounds and manufacturing methods to computer software and mechanical devices.8 Utility patents provide a robust 20-year term of protection from the earliest effective filing date, but require the periodic payment of maintenance fees to remain in force.45

- Design Patents: In contrast to utility patents, design patents protect the aesthetic, non-functional aspects of an invention—how an article looks. They are granted for a “new, original, and ornamental design for an article of manufacture”.46 The design and the object must be inseparable, but protection extends only to the product’s appearance, such as the iconic shape of the Coca-Cola bottle.45 To protect an object’s functional features, a separate utility patent is required. The term for a design patent is 15 years from the date of grant, and notably, no maintenance fees are required.8

- Plant Patents: This specialized category protects new and distinct varieties of plants that are asexually reproduced (i.e., through methods like grafting or cutting, not from seeds).45 The plant must not be a tuber-propagated type (like a potato) and cannot have been found in an uncultivated state.45 Plant patents have a 20-year term from the filing date.47

3.2 Chinese Patent Types: Invention, Utility Model, and Design Patents

China’s patent law also defines three types of patent rights, collectively known as “invention-creations”.49

- Invention Patents (发明专利): This is the highest tier of patent protection in China and is analogous to the U.S. utility patent. It protects a “new technical solution relating to a product, a process or an improvement thereof”.16 To be granted, an invention patent application must undergo a rigorous substantive examination to ensure it meets the standards of novelty, inventiveness (“notable progress”), and practical applicability.13 The term of protection is 20 years from the filing date.16

- Utility Model Patents (实用新型专利): This is the most strategically distinct feature of the Chinese system. A utility model protects a “new technical solution relating to the shape, the structure, or their combination, of a product, which is fit for practical use”.16 Crucially, its scope is limited in two significant ways: it can only protect products with a definite physical shape or structure, and it

cannot be used to protect processes, methods, chemical compounds, or software algorithms.16 Its key advantage lies in the examination process. Utility model applications undergo only a formal examination to check for compliance with procedural requirements; there is no substantive examination for inventiveness.13 This results in a very fast grant time, typically 6 to 12 months, and a lower cost.16 The term of protection is 10 years from the filing date.13 - Design Patents (外观设计专利): Similar to its U.S. counterpart, a Chinese design patent protects the aesthetic features of a product, defined as a “new design of the whole or partial shape or pattern of a product…which creates an aesthetic feeling and is fit for industrial application”.16 Following the 2021 amendments to the Patent Law, the term of protection for a design patent was extended to 15 years from the filing date.16

The very structure of China’s patent typology reveals a strategic emphasis on protecting tangible, manufactured goods, which formed the core of its industrial economy for decades. The specific limitations of the utility model—being restricted to the “shape” and “structure” of products and excluding methods 16—create a “fast lane” for protecting physical products. This is highly advantageous for a manufacturing-centric economy where incremental improvements to existing products are a primary form of innovation. An invention patent, which takes years to grant, is often too slow to be commercially relevant for products with short life cycles, a strategic gap that the utility model is perfectly engineered to fill.

3.3 Critical Distinctions: The U.S. Utility Patent vs. the Chinese Invention Patent

While Chinese invention patents and U.S. utility patents are broadly analogous, they differ in key aspects of patentable subject matter. The U.S. system’s scope is defined by the broad statutory categories in §101, with limitations coming from judicially created exceptions for abstract ideas, laws of nature, and natural phenomena.9 This has led to significant uncertainty in fields like software and business methods under the Supreme Court’s

Alice/Mayo framework, which requires a claimed abstract idea to be integrated into a “practical application”.19

China’s system, by contrast, relies on the statutory requirement that an invention must be a “technical solution” containing “technical features”.19 In practice, Chinese examiners often focus on whether a claim, even for an algorithm, is tied to a technical application and produces a technical effect. This can sometimes result in a more straightforward path to patentability for software or computer-implemented inventions compared to the complex, multi-step analysis required in the U.S., provided the invention is framed as solving a technical problem.19 Furthermore, China’s law explicitly excludes certain categories by statute, such as animal and plant varieties (though their production methods can be patented), which are handled differently in the U.S..16

3.4 The Strategic Linchpin: Understanding and Leveraging China’s Utility Model Patent

The utility model patent is a powerful and unique tool that is extensively used by Chinese domestic entities but frequently overlooked or misunderstood by foreign applicants.21 In the first quarter of 2022, for instance, 99.7% of the 766,957 utility model patents granted by CNIPA were to Chinese applicants.21

The strategic advantages are significant:

- Speed and Cost: With grant times under a year and lower official fees, utility models provide a rapid and cost-effective way to obtain enforceable patent rights.21

- Lower Inventive Step: The standard for inventiveness is lower than for an invention patent. The law requires “substantive features and represents progress,” as opposed to the “prominent substantive features and represents notable progress” required for an invention patent.20 Although utility models are not substantively examined upon filing, this lower standard becomes relevant if the patent is later challenged in an invalidation proceeding.

- Early Enforcement: A granted utility model can be enforced immediately, providing a legal shield against infringers while a more comprehensive invention patent application is still pending for several years.20 This is particularly valuable for products with short commercial life cycles where waiting for an invention patent to grant would mean missing the market window entirely.21

However, the utility model also has notable disadvantages, including its shorter 10-year term and its inapplicability to methods or processes.52 Because it is granted without substantive examination, it is often considered less “stable” than an invention patent. In fact, before a court will enforce a utility model patent, it typically requires the patentee to obtain a “patentability evaluation report” from CNIPA, which includes a prior art search and serves as prima facie evidence of the patent’s validity.20

For foreign companies, the utility model system is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it is a potent strategic tool that they are demonstrably underutilizing.21 On the other hand, the sheer volume of utility models filed by domestic competitors creates a dense and difficult-to-navigate “patent thicket.” This dramatically complicates Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis, as a company planning to launch a product in China must contend with a massive number of quickly granted, presumptively valid patents whose ultimate scope and validity are uncertain, thereby increasing litigation risk.57

Table 3.1: Comparative Overview of U.S. and Chinese Patent Types

| Feature | U.S. Utility Patent | U.S. Design Patent | U.S. Plant Patent | Chinese Invention Patent | Chinese Utility Model Patent | Chinese Design Patent |

| Subject Matter | Processes, machines, manufactures, compositions of matter 45 | Ornamental design of a manufactured article 46 | Asexually reproduced new plant varieties 45 | New technical solutions for products or processes 16 | New technical solutions for a product’s shape or structure only 16 | Aesthetic design of a product 16 |

| Key Standard | Novelty, Utility, Non-Obviousness 6 | New, Original, Ornamental 47 | Distinct, New, Asexually Reproduced 47 | Novelty, Practical Applicability, Inventiveness (“notable progress”) 12 | Novelty, Practical Applicability, Inventiveness (“progress”) 20 | Novelty, Fit for Industrial Application 16 |

| Examination Level | Substantive 59 | Substantive 45 | Substantive 45 | Substantive 16 | Formal Only 13 | Formal Only 16 |

| Term of Protection | 20 years from filing 45 | 15 years from grant 47 | 20 years from filing 47 | 20 years from filing 16 | 10 years from filing 16 | 15 years from filing 16 |

| Maintenance Fees | Yes 45 | No 45 | Yes 45 | Yes (Annual) 51 | Yes (Annual) 51 | Yes (Annual) 51 |

| Avg. Time to Grant | ~25 months 60 | Varies | Varies | 2-4 years 16 | 6-12 months 16 | 6-9 months 16 |

| Primary Strategic Use | Broad protection for core technology and processes | Protecting product aesthetics and brand identity | Protecting new horticultural innovations | Strong, long-term protection for core inventions | Rapid enforcement for incremental product improvements; short life-cycle products | Protecting product appearance |

Section 4: From Filing to Grant: The Patent Prosecution Journey

Navigating the path from a patent application to a granted right involves a series of procedural, substantive, and financial hurdles that differ significantly between the United States and China. These differences in timelines, costs, examination standards, and maintenance requirements demand distinct strategic approaches to maximize the value and enforceability of a global patent portfolio.

4.1 Application Pathways, Timelines, and Costs

United States Process:

The journey to a U.S. patent typically begins with either a provisional or a non-provisional application. A provisional application provides a lower-cost way to establish an early filing date and gives the inventor up to 12 months to refine the invention, assess its market potential, and file a corresponding non-provisional application.46 The non-provisional application initiates the formal examination process.45 The average time from filing to final disposition (pendency) at the USPTO is approximately 24.6 months.60 For applicants seeking faster review, the Track One prioritized examination program can yield a final decision in about 8-12 months, albeit for a significant additional fee.63

The costs of obtaining a U.S. patent are substantial and highly variable. Government fees are tiered based on the applicant’s size (micro entity, small entity, or large entity), with basic filing fees for a small entity utility application around $800.59 However, the primary expense is attorney fees. Drafting a quality patent application typically costs between $8,000 and $15,000, with complex software or medical device applications potentially exceeding $20,000.59 Responding to office action rejections during prosecution can add several thousand dollars per response. Consequently, the total budget to get a U.S. utility patent from filing through to issuance often ranges from $15,000 to $25,000 or more.59

China Process:

The timeline for patent prosecution in China is bifurcated by patent type. An invention patent application, which undergoes substantive examination, typically takes 2 to 4 years from filing to grant.16 In stark contrast, a utility model or design patent, which only requires a formal examination, is usually granted much more quickly, within 6 to 12 months.16

Official fees in China are generally lower than in the U.S. For example, the filing fee for an invention patent is 900 RMB (~$120), and the substantive examination fee is 2,500 RMB (~$325).66 Historically, various local and national government bodies provided subsidies to encourage patent filings, though these are now being phased out as part of a national strategy to prioritize patent quality over quantity.34

Both the U.S. and China are contracting states of the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which allows an applicant to file a single “international” application and delay the expensive step of entering the “national phase” in individual countries for up to 30-32 months from the priority date.3

4.2 Examination Standards in Focus: U.S. “Obviousness” vs. Chinese “Inventive Step”

While both systems require an invention to be a non-trivial advance over the prior art, their methodologies for assessing this criterion diverge in ways that can lead to different outcomes for the same invention.

U.S. Obviousness (35 U.S.C. § 103):

The U.S. standard for non-obviousness is guided by the Supreme Court’s landmark case, Graham v. John Deere Co. The analysis centers on four factual inquiries, known as the Graham factors: (1) determining the scope and content of the prior art; (2) ascertaining the differences between the prior art and the claims at issue; (3) resolving the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art; and (4) evaluating secondary considerations of non-obviousness, such as commercial success, long-felt but unsolved needs, and the failure of others.2 The central question for a USPTO examiner is whether a person of ordinary skill in the art, viewing the prior art,

would have been motivated to combine the known elements to arrive at the claimed invention with a reasonable expectation of success.7 A critical tenet of this analysis is the strict prohibition against using “impermissible hindsight”—that is, using the applicant’s own disclosure as a roadmap to piece together the prior art.7

Chinese Inventive Step (Article 22.3):

China’s CNIPA employs a more structured and formulaic “three-step method” to assess inventiveness.7 The examiner must:

- Identify the closest single piece of prior art.

- Determine the “distinguishing features” of the invention compared to that closest prior art and, based on those features, determine the “technical problem actually solved” by the invention.

- Judge whether, for a person skilled in the art, the claimed invention is obvious in view of the closest prior art, the distinguishing features, and the technical problem solved.

This structured approach, particularly its focus on the “technical problem actually solved,” is the source of a key strategic difference. An invention that might appear obvious under the U.S. “motivation to combine” test could be found inventive in China if its distinguishing features provide a significant and unexpected technical effect or improvement. The Chinese examiner’s framing of the technical problem is crucial; if an invention provides an unforeseen advantage, it is more likely to be deemed to possess an inventive step, even if the structural modification itself seems minor.7 This standard also varies by patent type: an invention patent must demonstrate “notable progress,” whereas a utility model need only show “progress”.20

The subtle but critical differences in these examination standards mean that a “one-size-fits-all” patent application is a flawed strategy. A specification drafted for a U.S. audience might focus on arguing against a motivation to combine known elements. This same application may be vulnerable in China if it fails to explicitly articulate a compelling technical problem and demonstrate a corresponding unexpected technical effect. Conversely, an application drafted for China that heavily emphasizes an unexpected technical advantage can be repurposed in the U.S., where “unexpected results” serve as a powerful secondary consideration against a finding of obviousness.69 This demonstrates that the drafting strategy for one jurisdiction should be actively informed by the requirements of the other.

4.3 Procedural Nuances and Pitfalls

Several unique procedural rules can act as traps for the unwary. China’s concept of “conflicting applications” is one such example. An application filed earlier but published later by a different party can destroy the novelty of an invention, but it cannot be used in an inventive step analysis.70 In the U.S., under the America Invents Act, such a document is treated as prior art for all purposes, including both novelty and obviousness assessments.70

Another difference lies in how inventor admissions are treated. In the U.S., if an applicant describes a reference as “prior art” in their patent specification, that statement can be treated as a binding admission, even if the reference might not otherwise qualify as prior art.71 The CNIPA and Chinese courts, however, require independent evidence that the reference was publicly known before the filing date; the applicant’s statement alone is not sufficient to establish it as prior art.71

4.4 Maintaining the Right: Annuity and Maintenance Fee Regimes

The fee structures for keeping a patent in force also reflect the systems’ underlying philosophies. The U.S. requires maintenance fees for utility and plant patents at three specific intervals: 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after the patent is granted.59 The fees increase significantly at each stage, forcing the patentee to re-evaluate the long-term strategic value of the patent at these key milestones.65

China, in contrast, requires the payment of annual fees, or annuities, for all three patent types.51 These annuities escalate progressively over the life of the patent.67 This structure forces a more frequent, yearly cost-benefit analysis. As commentators have noted, the rising fee schedule encourages patent owners to abandon patents as soon as their maintenance is no longer a sensible commercial investment.74 This acts as an aggressive “pruning” mechanism, designed to clear the patent register of commercially dormant rights and reduce the density of the “patent thicket.” This approach aligns with the Chinese system’s broader goal of promoting the active

exploitation of technology, rather than the mere holding of rights as passive assets.

Table 4.1: Estimated Timelines and Costs for Patent Prosecution: U.S. vs. China

| Metric | U.S. Utility Patent | Chinese Invention Patent | Chinese Utility Model Patent |

| Avg. Time to Grant | 2-3 years 60 | 2-4 years 16 | 6-12 months 16 |

| Initial Filing & Search Fees (Official) | ~$800 (Small Entity) 59 | ~900 RMB (~$120) 66 | ~500 RMB (~$70) 66 |

| Typical Attorney Drafting Fees | $8,000 – $15,000+ 59 | Varies, typically lower than U.S. | Varies, typically lower than Invention |

| Examination Fees (Official) | ~$800 (Small Entity) 59 | ~2,500 RMB (~$325) 67 | N/A (Formal Exam Only) |

| Typical Prosecution Attorney Fees | $3,500 – $4,500 per response 59 | Varies, typically lower than U.S. | Minimal |

| Total Estimated Cost to Grant | $15,000 – $25,000+ 59 | Varies, generally < $10,000 | Varies, generally < $2,000 |

| Maintenance Fee Structure | 3 payments at 3.5, 7.5, 11.5 years 65 | Escalating annual payments 67 | Escalating annual payments 73 |

| Total Lifetime Maintenance Fees (Est.) | ~$6,300 (Small Entity) 59 | ~82,300 RMB (~$10,700) 67 | ~9,800 RMB (~$1,300) over 10 yrs 73 |

Section 5: The Gauntlet of Enforcement: Litigating Patent Rights

The true value of a patent lies in its enforceability. Here, the U.S. and Chinese systems present starkly different landscapes for litigants. The U.S. offers a unified but lengthy and costly judicial process with extensive discovery, while China provides a bifurcated, faster, and less expensive system where validity and infringement are decided separately. Contrary to widespread perception, China has evolved into a surprisingly favorable and strategically critical forum for foreign patent holders seeking swift and powerful remedies.

5.1 The Bifurcated System: Challenging Validity and Infringement in China

China employs a bifurcated patent litigation system, similar to that of Germany, which separates the questions of patent infringement and patent validity.13

- Infringement Proceedings: Patent infringement lawsuits are heard in China’s judicial system. Over the past decade, China has established a sophisticated network of specialized IP courts in major economic hubs like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, as well as numerous regional IP tribunals.77 These courts have exclusive jurisdiction over patent cases, a reform designed to combat the local protectionism that historically plagued enforcement.80 For highly technical cases, such as those involving invention patents, appeals from these courts are now heard directly by a national-level IP Tribunal within the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), which functions similarly to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC).76

- Validity Proceedings: The validity of a granted patent cannot be challenged as a defense within an infringement lawsuit.53 Instead, any party wishing to challenge a patent’s validity must file a separate administrative invalidation request with the CNIPA.13 The CNIPA’s Re-examination and Invalidation Department will then conduct a proceeding to determine if the patent should have been granted. It is common practice for a defendant in an infringement suit to simultaneously file an invalidation request, and courts will often stay the infringement case pending the CNIPA’s decision on validity.13 Decisions from the CNIPA can be appealed to the Beijing IP Court and subsequently to the SPC’s IP Tribunal.13

This bifurcated structure is a direct response to historical criticisms of local protectionism and a lack of judicial expertise in complex patent matters.14 By centralizing jurisdiction for both infringement appeals and validity appeals in specialized, high-level courts, the Chinese central government has systematically worked to dismantle the structural causes of inconsistent and biased enforcement. This reform is the primary engine behind the increased predictability, professionalism, and rising foreign confidence in the Chinese IP litigation system.

5.2 The Unified Front: Litigation in U.S. District Courts and the ITC

The U.S. system generally handles infringement and validity in a single, unified proceeding. There are two primary venues for patent enforcement:

- U.S. Federal District Courts: This is the traditional venue for patent litigation. A patent holder files a complaint in a district court, and the defendant can then raise invalidity as a defense in the same case.42 The case is overseen by a single judge, and parties have the right to a jury trial. The process is lengthy, with the average time to trial being around two and a half years, and costly, often running into millions of dollars.42

- U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC): The ITC is a quasi-judicial federal agency that provides a powerful alternative venue for cases involving the importation of infringing goods into the U.S..76 An ITC investigation under Section 337 is extremely fast-paced, typically concluding within 15 to 18 months.84 The primary remedy available is an exclusion order, which directs U.S. Customs and Border Protection to block the importation of the infringing products.85 The ITC cannot award monetary damages.85 To bring a case, the complainant must prove the existence of a “domestic industry” related to the patented technology.84

In addition to these venues, the validity of an issued U.S. patent can be challenged at the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) through Inter Partes Review (IPR) or Post-Grant Review (PGR). These administrative proceedings are faster and less expensive than district court litigation and have become a very common tool for accused infringers to challenge patent validity.41

5.3 The Discovery Divide: Evidence Gathering in the U.S. vs. China

The most profound procedural difference between the two systems lies in the gathering of evidence.

- U.S. Discovery: The U.S. legal system is characterized by its broad and extensive pre-trial discovery process. Litigants have the power to compel opposing parties to produce vast quantities of documents, emails, and internal records, and to compel individuals to testify under oath in depositions.88 This process is designed to uncover all relevant facts, both favorable and unfavorable, before trial. It is also the primary driver of the high cost and long duration of U.S. patent litigation.42 For Chinese companies involved in U.S. litigation, this process is often alien and presents immense challenges, frequently clashing with China’s strict data security and state secrets laws.88

- China Evidence Gathering: Chinese litigation has no equivalent to U.S.-style discovery.76 The burden of proof rests almost entirely on the plaintiff to collect and present sufficient evidence of infringement and damages

before filing the lawsuit.82 This may involve making notarized purchases of infringing products or petitioning the court for an evidence preservation order, though the latter is not granted lightly.92 This “plaintiff-bears-the-burden” model is a key reason why Chinese litigation is significantly faster and less expensive than its U.S. counterpart.

5.4 Remedies and Realities: A Comparative Analysis of Injunctions and Damages

Injunctions:

In China, injunctive relief is a powerful and readily available remedy. Once infringement is found, a permanent injunction is granted in over 90% of cases.93 These injunctions can be particularly potent as they can block the export of infringing articles from China, effectively shutting down a global supply chain at its source.93 Preliminary injunctions are also available to halt alleged infringement while a case is pending, and courts are mandated to rule on such requests within 48 hours.44

In the U.S., the landscape changed dramatically after the Supreme Court’s 2006 decision in eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C. A finding of infringement no longer leads to an automatic permanent injunction. Instead, a patent holder must satisfy a stringent four-factor test, which has made injunctions significantly harder to obtain, particularly for non-practicing entities (NPEs).97 Proposed legislation, the RESTORE Act, seeks to make injunctions easier to obtain again.98

Damages:

Historically, monetary damages in Chinese patent cases were notoriously low, often limited to statutory damages due to the difficulty of proving actual losses or an infringer’s profits without a discovery process.93 However, this is changing rapidly. The 2021 Patent Law amendments raised the cap on statutory damages to RMB 5 million (~$715,000) and, most importantly, introduced punitive damages of up to five times the calculated base amount for willful infringement.44 This, combined with a pro-patentee shift in the specialized courts, has led to a significant increase in average damage awards, with some reaching tens of millions of dollars.43

U.S. damage awards, by contrast, are routinely among the highest in the world. Calculated based on complex economic analyses of reasonable royalties or the patentee’s lost profits, median awards are in the millions of dollars, and blockbuster verdicts can reach hundreds of millions or even billions.83

5.5 Outcomes and Perceptions: Win Rates for Foreign vs. Domestic Litigants

Perhaps the most surprising trend to emerge from the Chinese system is the high success rate of foreign plaintiffs. Contrary to the persistent narrative of a biased system rigged in favor of domestic companies, empirical data consistently shows that foreign entities win patent infringement lawsuits in China at a rate equal to, or often higher than, their domestic counterparts. Multiple studies and reports place the win rate for foreign plaintiffs in Chinese patent courts between 77% and 87%.35 This is a clear indicator that the specialized IP courts are making a concerted effort to provide fair, predictable, and impartial adjudication, likely as part of a broader state strategy to enhance the credibility of China’s IP system and encourage foreign companies to use it for enforcement.

The combination of China’s bifurcated system, lack of discovery, high injunction rate, and high foreign plaintiff win rate creates a unique strategic calculus. For a foreign patent holder whose products are being manufactured in China by a competitor, Chinese litigation presents a faster, cheaper, and more predictable path to obtaining an injunction that can halt a competitor’s global supply chain at its source. This reality transforms China from a market to be feared for its infringement risk into a premier global forum for strategic patent enforcement.

Table 5.1: Key Differences in Patent Litigation Venues: U.S. vs. China

| Feature | U.S. District Court | U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) | Chinese IP Court |

| Primary Jurisdiction | All patent disputes 42 | Unfair practices in the importation of goods 84 | Patent infringement disputes 75 |

| Handles Validity Challenge? | Yes, as a defense 42 | Yes, as a defense 76 | No; validity decided separately by CNIPA 13 |

| Avg. Time to Decision | 2-3 years 42 | 15-18 months 84 | 6-12 months 43 |

| Discovery Process | Extensive, party-driven discovery 76 | Expedited and limited discovery 85 | No formal discovery; plaintiff bears burden of proof 76 |

| Primary Remedy | Monetary damages, injunctions 85 | Exclusion Order (import ban), Cease & Desist Order 85 | Injunctions, monetary damages 53 |

| Likelihood of Injunction (Post-Win) | Moderate; subject to eBay four-factor test 97 | N/A (Exclusion Order is the standard remedy) 85 | Very High (>90%) 93 |

| Monetary Damages? | Yes, can be substantial 83 | No 85 | Yes, historically low but rapidly increasing 93 |

| Key Requirement | Personal & subject matter jurisdiction 85 | Proof of a U.S. “domestic industry” 84 | Pre-suit collection of infringement evidence 92 |

Section 6: Advanced Strategies for Global Patent Portfolios

Effectively navigating the U.S. and Chinese patent systems requires more than just filing applications; it demands sophisticated strategies that leverage the unique features, procedures, and tools of each jurisdiction. For global innovators, understanding concepts like China’s “dual filing” system, the Patent Prosecution Highway, and the distinct challenges of Freedom-to-Operate analysis is critical for building a robust and defensible international IP portfolio.

6.1 The “Dual Filing” Advantage in China: Securing Early Rights

One of the most powerful and unique strategies available in China is the “dual filing” or “both-filing” system. Chinese patent law permits an applicant to file for both an invention patent and a utility model patent for the same invention on the same day.20 This strategy is designed to provide the best of both worlds: the speed of the utility model and the strength of the invention patent.

The mechanism is straightforward. Upon filing, the two applications proceed on parallel tracks.55 The utility model application, which only undergoes a formal examination, is typically granted within 6 to 12 months. This provides the applicant with a legally enforceable patent right almost immediately, allowing them to take action against infringers, secure licensing deals, or deter copycats.55 Meanwhile, the invention patent application continues through its much longer substantive examination process, which can take several years.107 If and when the CNIPA determines that the invention patent is allowable, it will notify the applicant. To avoid “double patenting” for the same invention, the applicant must then abandon the already-granted utility model patent to allow the invention patent to issue.106

This strategy effectively de-risks market entry and investment. By securing an enforceable utility model within a year, a company can launch a new product in the vast Chinese market with a legal shield in place, making the multi-year wait for the more robust 20-year invention patent commercially viable. It transforms the patent system from a slow, long-term asset into a timely, tactical tool that directly supports a business’s go-to-market strategy.22 It also provides a valuable fallback; if the invention patent is ultimately rejected on inventiveness grounds, the applicant may still retain protection through the utility model, which is subject to a lower inventive step standard.55 It is important to note that this strategy is available for direct national filings under the Paris Convention but is not an option for applications entering China’s national phase via the PCT, where an applicant must choose to proceed as either an invention or a utility model, but not both.20

6.2 Accelerating Prosecution: The Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH)

For companies filing patents in multiple jurisdictions, the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) is a vital tool for accelerating examination and reducing costs. The USPTO and CNIPA are both members of the Global PPH pilot program, which allows for work-sharing between offices.51 Under the PPH, an applicant who receives a final ruling from one patent office (the Office of Earlier Examination, OEE) that at least one claim is allowable can request that a second office (the Office of Later Examination, OLE) accelerate the examination of the corresponding application.

The OLE can then leverage the search and examination work already performed by the OEE, which often leads to a faster examination process and a higher likelihood of allowance.51 To be eligible to request PPH at CNIPA based on a U.S. allowance, for example, the Chinese application must have already been published and a request for substantive examination must have been filed.110 The claims in the Chinese application must also “sufficiently correspond” to the allowed claims in the U.S. patent. The PPH is a powerful efficiency tool, but it requires careful management of claims across jurisdictions to ensure correspondence and eligibility.

6.3 Navigating the Thicket: Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Challenges in a Patent-Dense China

Conducting a Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis—an assessment to determine if a proposed product or process infringes any valid third-party patents—is a standard part of risk management before a product launch. In China, however, this process is uniquely and profoundly challenging.57

The difficulties stem directly from the same government policies that fueled China’s patent boom. Years of subsidies and mandates created a “patent flood” of domestic applications, many of which are utility models.33 This creates several interlocking challenges for FTO searches:

- Sheer Volume: The number of potentially relevant patents is immense, making a comprehensive search a massive and costly undertaking. In 2018 alone, CNIPA received 1.6 million domestic invention patent applications, in addition to utility models and designs.57

- Language Barrier: The vast majority of these documents, particularly those from smaller domestic filers, are published only in Chinese. This necessitates significant investment in translation services and heavy reliance on local Chinese law firms to conduct effective searches and analysis.57

- The Utility Model Problem: The prevalence of utility models creates significant legal uncertainty. Because they are not substantively examined before grant, their claims are often broad and of questionable validity. However, they are legally presumed valid until successfully challenged and can be asserted in litigation.57 An FTO analysis must therefore account for a huge number of rapidly granted patents whose true scope and strength are unknown, creating a minefield of potential risk.57

The legacy of China’s “quantity over quality” era will persist for at least a decade as these patents live out their 10- or 20-year terms. Therefore, the heightened FTO risk in China is a long-term structural problem, not a temporary anomaly, and it requires a sustained, specialized risk mitigation strategy that goes beyond standard search protocols. This includes continuous monitoring and a deep understanding of the utility model landscape.

A complete strategy also involves leveraging customs enforcement. Both the U.S. and China have systems that allow IP rights holders to record their patents and trademarks with customs authorities (U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the General Administration of Customs of China, respectively). This enables customs officials to proactively identify and seize infringing goods at the border, providing a crucial, practical layer of enforcement that complements litigation.112

Section 7: High-Stakes Arenas: Sector-Specific Deep Dives

The general principles of patent law are applied with unique intensity and nuance in high-stakes technology sectors where innovation is rapid and the value of intellectual property is immense. A deep dive into the pharmaceutical and artificial intelligence sectors reveals how the U.S. and Chinese patent systems are not just passive frameworks but are actively being shaped and utilized to achieve specific national, economic, and public health objectives.

7.1 Pharmaceuticals and Life Sciences: Patent Term Extension, Data Exclusivity, and Linkage Systems

For the pharmaceutical industry, where the time from patent filing to market launch can exceed a decade and R&D costs are astronomical, the effective life of a patent is paramount. Both the U.S. and China have developed sophisticated legal frameworks to address the unique challenges of this sector.

Patent Term Extension (PTE):

To compensate for the erosion of a patent’s effective term due to lengthy clinical trials and regulatory review, both countries offer Patent Term Extension (PTE).

- In the United States, the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act established a PTE system that can restore a portion of the patent term lost during FDA review. The extension is capped at a maximum of five years, and the total effective patent term after a product’s approval cannot exceed 14 years.113

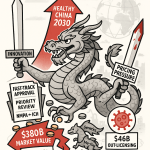

- China introduced a very similar PTE system in its 2021 Patent Law revision, also featuring a five-year maximum extension and a 14-year post-approval cap.114 The first “top extension” of five years was granted in June 2025 for the drug Telitacicept, demonstrating the system’s practical implementation.114 However, there is a critical, strategy-altering difference: China’s PTE is only available for patents covering a “new drug,” which is defined as a drug that has

not been marketed overseas or domestically before the Chinese marketing approval.116

Regulatory Data Exclusivity:

This is a separate form of protection that prevents generic drug manufacturers from relying on the innovator’s costly and time-consuming clinical trial data to gain their own marketing approval.

- In the U.S., the FDA provides set periods of data exclusivity, such as five years for a New Chemical Entity (NCE) and three years for a new clinical investigation.118

- China has been formalizing its data exclusivity framework. Draft rules published in 2022 propose a six-year exclusivity period for innovative new drugs.119 Similar to the PTE provisions, this protection is designed to incentivize China-first launches. The exclusivity term is reduced by the length of time between the drug’s first approval in a foreign country and the date the marketing application is accepted in China.119

Patent Linkage Systems:

These systems “link” the drug approval process to the patent system, creating a mechanism to resolve patent disputes before a generic drug enters the market.

- The U.S. Hatch-Waxman Act created the “Orange Book,” a registry of patents covering FDA-approved drugs. When a generic company files an application (an ANDA) challenging a listed patent, it triggers a process that can result in an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval while the patent dispute is litigated in court.122 The first generic filer to successfully challenge a patent is rewarded with 180 days of market exclusivity.123

- China’s 2021 law established a parallel system, creating the “China Patent Information Registration Platform for Marketed Drugs” (the Chinese “Orange Book”).124 When a generic applicant files a declaration challenging a listed patent (a “Type IV” declaration), the patent holder has 45 days to initiate a lawsuit or an administrative proceeding. This action triggers a nine-month stay on the generic’s marketing approval.123 The system also provides a 12-month market exclusivity period to the first generic applicant that successfully challenges a patent and obtains marketing approval.122

Taken together, China’s new pharmaceutical IP framework is more than an imitation of the U.S. system; it is a strategically engineered “incentive trap.” By making the most valuable IP protections—a full-term PTE and full-term data exclusivity—contingent on launching a new drug in China first, or at least simultaneously with other major markets, Beijing is using its patent system as a powerful policy tool. The framework is designed to fundamentally alter the global drug launch strategies of multinational pharmaceutical companies, forcing them to re-prioritize the Chinese market. The intended outcomes are to provide Chinese citizens with faster access to innovative medicines and to stimulate more clinical trial and R&D activity on Chinese soil, thereby directly supporting the state’s strategic goal of building a world-class domestic biotechnology industry.127

7.2 The Digital Frontier: Patenting AI and Software-Related Inventions

In the realm of artificial intelligence (AI) and software, the patenting trends and standards in the U.S. and China reflect two distinct national strategies for achieving dominance in the technologies that will define the 21st-century economy.

Filing Trends and National Strategies:

China has established a commanding lead in the sheer volume of AI-related patent filings, accounting for over 70% of all applications globally in recent years and an even more dominant share in the sub-field of generative AI.129 This surge is driven by massive government investment and a national strategy to lead in AI by 2030.130 However, the vast majority of these patents are filed only within China, suggesting a primary focus on domestic market control.129

The United States, while filing a smaller volume of AI patents, demonstrates a different strategic focus. U.S.-origin AI patents have a much higher citation impact and are filed more broadly across international jurisdictions.129 This divergence reveals two different approaches to technological competition. China’s strategy can be seen as one of “technological envelopment,” using a massive volume of domestic patents to create a dense protective thicket, securing its vast internal market and complicating entry for foreign firms. The U.S. strategy is one of “foundational control,” focusing on securing high-impact, internationally protected patents on core technologies that can be licensed globally and serve as the basis for worldwide technology standards.

Patentability Standards:

The legal standards for patenting AI and software inventions differ significantly, creating a paradox where the country historically criticized for weak IP may now be a more favorable jurisdiction for certain software-related inventions.

- In the United States, AI inventions face the significant hurdle of the patent eligibility doctrine under 35 U.S.C. § 101, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank and Mayo v. Prometheus. This two-step test often characterizes AI algorithms as “abstract ideas.” To be patentable, the claims must integrate the abstract idea into a “practical application” or add an “inventive concept” that amounts to “significantly more” than the abstract idea itself.9 The USPTO has issued detailed guidance for its examiners on applying this complex and often unpredictable framework to AI inventions.130

- In China, the analysis centers on the statutory requirement for a “technical solution” that utilizes “technical means” to achieve a “technical effect”.19 The 2024 CNIPA “Guidelines for Patent Applications for Artificial Intelligence” clarify that AI algorithms can be patentable subject matter if they are applied to a specific technical field and solve a technical problem.39 This approach can be more straightforward and permissive for AI inventions that are clearly tied to improving a technical process or the performance of a computer system, avoiding the “abstract idea” quagmire that often plagues U.S. applications.19

On the question of inventorship, both the USPTO and CNIPA are currently aligned: an inventor must be a natural person. An AI system itself cannot be named as an inventor on a patent application, though inventions created with the assistance of AI are patentable so long as a human made a “significant contribution”.137

Table 7.1: Comparison of Pharmaceutical Patent Exclusivity Mechanisms

| Feature | United States | China |

| Patent Term Extension (PTE) | ||

| Max Extension Duration | 5 years 113 | 5 years 114 |

| Max Post-Approval Term | 14 years 113 | 14 years 115 |

| Eligibility Requirement | Any drug delayed by FDA regulatory review 113 | “New Drug” not previously marketed anywhere in the world 117 |

| Regulatory Data Exclusivity | ||

| Term for New Chemical Entity | 5 years 118 | 6 years (term reduced by delay after first foreign approval) 119 |

| Term for New Indication | 3 years 118 | 3 years for certain “improved new drugs” 119 |

| Patent Linkage System | ||

| “Orange Book” Equivalent | FDA Orange Book 122 | China Patent Information Registration Platform (CPIRPMD) 124 |

| Stay on Generic Approval | 30 months 123 | 9 months 124 |

| Generic Exclusivity | 180 days for first-to-file a Paragraph IV certification 123 | 12 months for first to successfully challenge a patent and get approval 124 |

Section 8: The Shifting Landscape: Recent Reforms and Future Trajectories

The patent systems in both the United States and China are in a state of dynamic flux. The U.S. is grappling with fundamental questions about the scope and certainty of patent rights, with major legislative reforms under consideration. China, having achieved its goal of patent volume, is now executing a decisive pivot toward “high-quality” innovation and refining its IP framework into a more sophisticated tool of industrial policy. These developments are unfolding against a backdrop of intense geopolitical competition, where IP has become a central arena for the U.S.-China rivalry.

8.1 U.S. Legislative Outlook: The Potential Impact of PERA, PREVAIL, and RESTORE Acts

After more than a decade of judicial decisions that many stakeholders argue have weakened patent rights and created legal uncertainty, the U.S. Congress is now considering a trio of significant bipartisan bills aimed at recalibrating the system in favor of patent holders.97

- The Patent Eligibility Restoration Act (PERA): This is arguably the most consequential of the proposed reforms. PERA seeks to legislatively overrule the Supreme Court’s Alice/Mayo framework by eliminating the judicially created exceptions to patent eligibility (abstract ideas, laws of nature, natural phenomena).97 By doing so, it would dramatically clarify and broaden the scope of patentable subject matter, making it significantly easier to obtain patents for inventions in critical fields like diagnostic methods, artificial intelligence, and computer software, which have faced the greatest uncertainty under the current regime.1

- The PREVAIL Act: This bill targets the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), which critics have dubbed the “patent death squad” for its high rate of invalidating patents in IPR proceedings.97 The PREVAIL Act would make it more difficult to challenge patents at the PTAB by introducing a standing requirement (only parties sued or threatened with suit could file a challenge), raising the burden of proof for invalidation from a “preponderance of the evidence” to the higher “clear and convincing evidence” standard used in district courts, and limiting the ability of challengers to file serial petitions against the same patent.98

- The RESTORE Act: This act aims to reverse the effects of the Supreme Court’s eBay decision by establishing a rebuttable presumption that a permanent injunction should be granted upon a finding of patent infringement.97 This would make it much easier for patent holders to stop infringing activity, restoring a powerful remedy that has been more difficult to obtain for the past 15 years.

If enacted, these reforms would collectively represent the most significant strengthening of U.S. patent rights in a generation, potentially spurring investment in key technology sectors but also raising concerns among some industries about increased litigation and higher costs.97

8.2 China’s IP Evolution: The Drive for “High-Quality” Patents and Strengthened Enforcement

China’s recent and ongoing reforms are guided by a clear state directive: to transition its IP system from one focused on quantity to one that fosters “high-quality” development. The Implementing Regulations of the Patent Law, which took effect in January 2024, codify this new direction.141

Key elements of this evolution include:

- Improving Patent Quality: The central pillar of the new strategy is a crackdown on “abnormal patent applications”.38 By implementing a “good faith” principle in examination and eliminating the subsidies that encouraged low-quality filings, CNIPA is actively working to improve the overall quality of its patent grants. This policy shift is the primary reason for the nearly 29% decline in invention patent grants in the first half of 2025, a clear signal that the agency is prioritizing quality over raw numbers.40

- Strengthening Patentee Rights: China has introduced new mechanisms to enhance the value of patents, including a Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) system to compensate for unreasonable examination delays and the comprehensive Patent Term Extension (PTE) system for pharmaceuticals.142

- Future Plans: The “2025 Intellectual Property Nation Building Promotion Plan” indicates a continued focus on legislative refinement, including revisions to the Trademark Law and new guidelines for standard-essential patents (SEPs), an area of increasing global friction.39

This shift is not merely cosmetic. It reflects a strategic calculation that for China to achieve its goal of becoming a global technology leader, it needs an IP system that is not only large but also respected and effective at protecting genuine, high-value innovation.36

8.3 The Geopolitical Undercurrent: How Trade Relations Shape IP Policy

Intellectual property is not just a matter of commercial law; it is a central and contentious issue in U.S.-China geopolitical relations. For decades, the U.S. has accused China of systemic IP theft, forced technology transfer, and rampant counterfeiting, estimating the annual cost to the U.S. economy in the hundreds of billions of dollars.145 These grievances were a primary justification for the trade war initiated by the Trump administration, and IP protection was a core component of the subsequent Phase One trade agreement.150

However, the dynamic is more complex than one of a victim and a perpetrator. China’s own internal economic incentives are now driving its IP reforms. As Chinese companies like Huawei, Tencent, and Baidu have become major global innovators and massive patent holders themselves, their interests—and by extension, the interests of the Chinese state—have shifted dramatically toward favoring stronger and more reliable IP protection, both at home and abroad.17

This has created a paradoxical situation. While China is genuinely strengthening its IP laws and enforcement in ways that benefit foreign companies, it is also being accused of weaponizing its increasingly sophisticated legal system for strategic advantage. The issuance of “anti-suit injunctions” by Chinese courts, which prohibit companies from pursuing patent litigation in other countries, is a prime example of China using its judicial power to assert sovereignty in global IP disputes, often to the benefit of its national champions.152

8.4 Concluding Analysis: Future Trends and Long-Term Strategic Outlook

Looking ahead, the patent systems of the U.S. and China appear to be on paths of both convergence and divergence. Procedural convergence is evident as China adopts features like PTE and the U.S. has adopted a first-to-file system. However, their fundamental strategic purposes are diverging more sharply. The U.S. is engaged in a debate about returning to a system of stronger, more certain private patent rights. China is methodically refining its IP system into a more powerful and precise tool of statecraft and industrial policy.

This divergence is creating a potential reversal of historical norms. As China provides clearer and more permissive guidelines for patenting emerging technologies like AI 130, the U.S. remains mired in a decade-long struggle over patent eligibility that has created profound uncertainty in these same fields.10 If current trends persist, innovators could face a future where it is paradoxically easier and more predictable to patent cutting-edge software in China than in Silicon Valley.

Ultimately, the ongoing friction over IP is not a temporary trade dispute but the manifestation of a long-term “IP Cold War.” In this new era, both nations view intellectual property as a critical element of national security and a key lever in their geopolitical competition.35 We can expect to see an increasing use of IP systems for strategic, non-market purposes, from jurisdictional power plays like anti-suit injunctions to potential restrictions on foreign access to patent systems. For global corporations and policymakers, the inescapable conclusion is that in the 21st century, intellectual property strategy is geopolitical strategy.156 The future of innovation will be shaped not only by scientists and engineers, but by the strategic navigation of these two competing legal and political philosophies. The transformative impact of AI will only accelerate this trend, challenging core legal concepts of inventorship and obviousness and forcing both legal systems to adapt at an unprecedented pace.160

Works cited

- Our Principles – USIJ, accessed August 4, 2025, https://usij.org/principles/

- Patent Law: A Handbook for Congress, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46525

- United States Patent and Trademark Office – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Patent_and_Trademark_Office

- A Comparative Study of Patent Eligibility of Biological Subject Matters Between China and the United S, accessed August 4, 2025, https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1116&context=cybaris

- U.S. Patent and Trademark Office – (Intro to American Government) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed August 4, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/key-terms/fundamentals-american-government/us-patent-trademark-office

- The Four Pillars of Patentability: Ensuring Your Invention Qualifies, accessed August 4, 2025, https://boldip.com/blog/the-four-pillars-of-patentability-ensuring-your-invention-qualifies/

- Securing Global Patents: U.S. “Obviousness” vs. Chinese “Inventive Step” Standards, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.stites.com/resources/client-alerts/securing-global-patents-u-s-obiousness-vs-chinese-inventive-step-standards/

- Types of Patents Available Under Federal Law | Intellectual Property Law Center | Justia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.justia.com/intellectual-property/patents/types-of-patents/

- United States patent law – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_patent_law

- Patent-Eligible Subject Matter Reform: Background and Issues for Congress, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45918

- The Impact of Uncertainty Regarding Patent Eligible Subject Matter for Investment in U.S. Medical Diagnostic Technologies, accessed August 4, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4762&context=wlulr

- Latest Developments of Patent System in Mainland China, accessed August 4, 2025, https://english.cnipa.gov.cn/transfer/news/officialinformation/1121581.htm

- Patent law of China – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent_law_of_China

- Riding the Tiger: A Comparison of Intellectual Property Rights in the United States and the People’s Republic of China, accessed August 4, 2025, https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1064&context=ckjip

- Impact of Intellectual Property System on Economic Growth – WIPO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.wipo.int/about-ip/en/docs/studies/wipo_unu_07_china.pdf

- Guide to Patent Application in China 2025 – GBA IP LAWYER, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.gbaiplawyer.com/patent-application/

- Evolution of the Chinese Intellectual Property Rights System: IPR Law Revisions and Enforcement | Management and Organization Review – Cambridge University Press, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/management-and-organization-review/article/evolution-of-the-chinese-intellectual-property-rights-system-ipr-law-revisions-and-enforcement/ACEF8E7FC893123D6D95FF6245CC51D6