In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical development, information is the most valuable currency. Companies pour billions into research and development, seeking the next blockbuster drug that will change lives and shareholder fortunes. But what if I told you that one of the most powerful sources of competitive intelligence isn’t locked away in a competitor’s lab but is, in fact, publicly available? It’s a resource that many see only as a legal hurdle or a future expiration date, but which, when viewed through the right lens, becomes a detailed roadmap of a competitor’s thinking, their challenges, and their strategic vision. I’m talking about drug patents.

We often think of a patent as a simple “Do Not Enter” sign, a legal fence erected around a new molecule. While this is its primary function, a patent document is so much more. It’s a mandatory disclosure, a quid pro quo where the inventor, in exchange for a limited monopoly, must teach the public how their invention works. Within the dense, legalistic language of these documents lies a treasure trove of scientific data, a narrative of trial and error, and a blueprint of the formulation strategies that turn a promising Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) into a safe, stable, and effective drug product.

For business leaders, R&D scientists, and intellectual property strategists, learning to read between the lines of a patent is not just an academic exercise; it’s a critical business competency. It’s about transforming a defensive document into an offensive tool. Are you a generic manufacturer looking for the chink in the armor of a branded drug’s patent protection? The clues are in the formulation patents. Are you an innovator company trying to anticipate a rival’s next move or find “white space” for your own pipeline? Their patent filings can reveal their direction of travel long before a product hits the market.

This article is your guide to becoming a patent decoder. We will move beyond the patent abstract and expiration date to explore the rich, technical details hidden within. We’ll dissect the anatomy of a patent, learn how to identify the subtle hints about solubility challenges, stability issues, and bioavailability enhancement, and ultimately, show you how to translate this technical intelligence into a tangible competitive advantage. Prepare to look at patents in a whole new light—not as barriers, but as blueprints.

The Pharmaceutical Patent Landscape: More Than Just an Expiration Date

Before we can extract strategic insights, we must first understand the terrain. The pharmaceutical patent landscape is a complex ecosystem of different types of intellectual property (IP), each serving a unique purpose and offering different clues. Viewing every patent as a monolithic entity is a common mistake that obscures valuable detail. A company’s patenting strategy around a single drug is often a multi-layered fortress, designed not only to protect the core invention but also to extend its commercial life and defend against competition from every possible angle.

Think of it like securing a medieval castle. The first and strongest wall is the patent on the castle itself—the new molecule, the API. But a smart ruler doesn’t stop there. They build outer walls (formulation patents), fortify the gatehouses (delivery device patents), and even patent the unique ways the castle can be used (method-of-use patents). Each layer provides additional protection and tells you something about the perceived threats and strategic priorities of the castle’s owner.

Understanding the Anatomy of a Drug Patent

At first glance, a patent document can be intimidating. It’s a hybrid of dense legal prose and highly technical scientific explanation. However, once you understand its structure, you can navigate it efficiently to find the information you need. Every patent generally follows a standardized format, and knowing what to look for in each section is the first step in your intelligence-gathering mission.

The Abstract and Background: Setting the Scene

The Abstract is a brief summary of the invention, typically a few hundred words. It’s designed to give patent examiners and researchers a quick overview of the patent’s subject matter. While useful for an initial screening, it rarely contains the granular detail needed for a deep formulation analysis.

The Background of the Invention section is where the story begins. Here, the inventors lay out the “state of the art” before their invention. This is a goldmine for understanding the context. The patent will describe the problem they were trying to solve. For formulation patents, this section often explicitly details the shortcomings of existing formulations. For example, it might state that the API has poor water solubility, is unstable in the presence of certain excipients, or has a bitter taste that needs masking. This section is a direct admission of the technical hurdles the formulators faced, giving you a clear picture of the challenges your own team might encounter with the same or a similar API. It essentially hands you the “problem” part of the “problem-solution” equation.

The Detailed Description: The Scientific Goldmine

This is the heart of the patent and where you’ll spend most of your time. The “Detailed Description of the Invention,” or “Summary of the Invention,” is where the inventors must, by law, describe their invention in enough detail for a “person having ordinary skill in the art” (a PHOSITA) to replicate it. This obligation to teach is the trade-off for the monopoly rights a patent grants.

Within this section, you’ll find comprehensive discussions of:

- The API: Its chemical structure, polymorphs, and key physicochemical properties.

- The Excipients: Lists of potential fillers, binders, lubricants, glidants, disintegrants, surfactants, antioxidants, preservatives, and coating agents. The inventors often provide not just a single combination but a range of possibilities.

- Concentrations and Ratios: The patent will specify preferred ranges for the API and key excipients. For instance, it might state “the surfactant is present in an amount from 1% to 10% by weight, preferably 2% to 5%.” This data is invaluable for understanding the delicate balance required for the formulation to work.

- Manufacturing Processes: It may describe the steps taken to create the final dosage form—wet granulation, dry granulation, direct compression, spray drying, lyophilization, etc. This can reveal crucial information about the properties of the formulation blend and potential manufacturing challenges.

This section is your primary source for deconstructing the formulation. It’s a window into the months, or even years, of benchtop experimentation that led to the final product.

The Claims: The Legal Fortress

If the Detailed Description is the scientific textbook, the Claims are the legal contract. This section, located at the end of the patent, defines the precise scope of what the inventor is protecting. Each claim is a single sentence that meticulously sets out the boundaries of the invention. Anything that falls within the scope of a claim is considered infringing.

For formulation analysis, the claims are critical for two reasons:

- Defining the Core Protected Technology: They tell you exactly what the innovator considers novel and non-obvious about their formulation. Is it the use of a specific solubility-enhancing polymer? A particular ratio of a stabilizer to the API? A unique combination of coatings for controlled release? The claims pinpoint the inventive step.

- Identifying Design-Around Opportunities: For generic or 505(b)(2) developers, the claims define the “picket fence” you need to navigate around. If a patent claims a formulation containing excipient A, B, and C, could you develop a successful formulation using excipients A, B, and D? The claims provide the legal blueprint for your non-infringing design strategy.

Interpreting claims is a specialized skill, often requiring the expertise of a patent attorney. However, a business or R&D professional can still glean immense strategic value by understanding what is—and just as importantly, what is not—being claimed.

Examples and Embodiments: Where Theory Meets Practice

This is arguably the most valuable section for a formulator. The “Examples” or “Embodiments” section provides concrete, real-world illustrations of the invention. These are not theoretical; they are write-ups of actual experiments performed by the inventors.

You will find specific recipes, including the exact weights and percentages of each ingredient used to make a batch of tablets, a solution for injection, or a cream. You will often find comparative data, where the inventors show that their new formulation (Example 1) performs better than an old formulation or a placebo (Comparative Example A). This data might include dissolution profiles, stability results under accelerated conditions (high temperature and humidity), or bioavailability data from animal or human studies.

These examples are the closest you can get to having the innovator’s lab notebook. They allow you to:

- Validate the general statements made in the Detailed Description.

- Identify the most successful or “preferred” embodiment, which is often the one that most closely resembles the final marketed product.

- Understand the testing methodologies used to evaluate the formulation’s performance.

By carefully analyzing the examples, you can reconstruct the innovator’s development process and understand why they made the formulation choices they did, backed by the data they themselves provide.

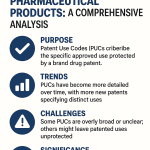

Differentiating Between Patent Types

A successful drug is rarely protected by a single patent. Innovator companies employ a strategy called “lifecycle management” or “evergreening,” where they build a portfolio of patents to protect their product for as long as possible. Understanding the different types of patents in this portfolio is key to seeing the full strategic picture.

Composition of Matter Patents: The Core Invention

This is the crown jewel. A composition of matter patent protects the new chemical entity (NCE) itself—the API. It’s the first patent filed and provides the broadest and strongest protection. For a period, typically 20 years from the filing date, no one else can make, use, or sell that molecule without a license. These patents are less focused on the formulation and more on the discovery of the API. However, the initial patent application may contain early formulation work, providing a first glimpse into the API’s properties and challenges.

Formulation Patents: The Delivery System

These patents are our primary focus. Filed after the initial composition of matter patent, they don’t protect the API itself but rather the specific combination of the API with various excipients to create the final drug product. A company might have multiple formulation patents for a single drug.

Why? Perhaps the first-generation formulation was a simple immediate-release tablet. Years later, to improve patient compliance or extend the product’s life, they might develop and patent a new once-daily, extended-release version. This new patent creates a fresh 20-year term of protection for that specific formulation, even after the original API patent has expired.

Examples of what a formulation patent might cover include:

- A solid dispersion to improve the solubility of a poorly soluble drug.

- A specific buffer system to maintain the pH and stability of an injectable biologic.

- A taste-masked liquid formulation for pediatric use.

- A specific combination of polymers in a transdermal patch to control the rate of drug delivery through the skin.

Analyzing these patents reveals the innovator’s lifecycle management strategy and their efforts to overcome specific drug delivery challenges.

Method of Use Patents: New Applications

These patents protect a specific method of using a drug to treat a particular disease or condition. For example, a drug initially approved to treat epilepsy might later be found effective for treating migraines. The company can then obtain a new method-of-use patent for the treatment of migraines.

While not directly about formulation, these patents can have formulation implications. A new use might require a different dosage, a different delivery route (e.g., from oral to injectable for a different patient population), or a different release profile, which in turn would necessitate a new formulation, likely protected by its own patent. They signal the company’s strategy to expand the market for its drug.

Process Patents: The Manufacturing Blueprint

Process patents protect a specific, novel method of manufacturing a drug. This could be a new, more efficient way to synthesize the API or a unique method for producing the final dosage form. For example, a company might invent a novel continuous manufacturing process that improves the quality and consistency of their tablets, and they can patent that process.

For a competitor, this means that even if the composition and formulation patents have expired, they may still be blocked from using the most efficient manufacturing method. Analyzing these patents can reveal insights into the scale-up and commercial manufacturing of a drug, highlighting potential cost advantages or quality control measures the innovator has developed.

By understanding this layered approach to patenting, you can appreciate that a drug’s IP portfolio is a living, evolving entity. Each new patent filing is a strategic move, a breadcrumb trail that reveals the company’s long-term vision for its product.

Decoding Formulation Strategies from Patent Text

Now that we understand the structure and types of patents, we can move to the core task: extracting actionable intelligence. This is part forensic science, part detective work. You are looking for patterns, for subtle clues, and for the story behind the data. The goal is to reverse-engineer not just the formulation itself, but the rationale behind it. Why was this polymer chosen over that one? What does the inclusion of a specific antioxidant tell you about the API’s stability? Answering these questions is the key to unlocking true competitive insight.

Identifying Key Excipients and Their Roles

Excipients are the “inactive” ingredients in a drug product, but their role is anything but passive. They are the workhorses that ensure the API is delivered to the right place, at the right time, and in the right concentration. They solve problems. Therefore, the choice of excipients is a direct reflection of the problems the formulators encountered with the API. A patent’s excipient list is a diagnostic tool.

Reading Between the Lines: Why Certain Excipients are Chosen

Every class of excipient has a function, and its presence in a patent is a major clue. Let’s break down what to look for:

- Solubility Enhancers: Does the patent mention excipients like Poloxamers (e.g., Pluronic® F68), Vitamin E TPGS, Soluplus®, or cyclodextrins (e.g., Captisol®)? This is a massive red flag that the API has poor aqueous solubility—a common challenge for modern drug candidates (estimated to be over 70% of NCEs in the pipeline [1]). The patent may even describe technologies like amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) or lipid-based formulations (e.g., self-emulsifying drug delivery systems, SEDDS). The presence of these sophisticated techniques tells you that simple micronization or pH adjustment was not enough. This insight is critical for a generic developer, who must now plan for developing their own, non-infringing solubility enhancement platform.

- Stabilizers: Do you see antioxidants like butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), or ascorbic acid? This strongly suggests the API is prone to oxidative degradation. Are chelating agents like edetate disodium (EDTA) listed? This points to sensitivity to metal ions, which can catalyze degradation reactions. For biologics (proteins, antibodies), the presence of specific sugars (sucrose, trehalose) and amino acids (arginine, histidine) is a clear indicator of efforts to prevent aggregation and denaturation, which are the Achilles’ heel of protein-based drugs.

- Bioavailability Enhancers: Some excipients, such as permeation enhancers (e.g., certain surfactants or fatty acids) or efflux pump inhibitors (e.g., piperine derivatives), are included specifically to increase the amount of drug that gets absorbed into the bloodstream. Their inclusion in a patent signals that the API suffers from poor membrane permeability or is actively pumped out of cells by transporters like P-glycoprotein. This is a crucial piece of information, as it moves the formulation challenge from simple chemistry to complex biology.

- Controlled-Release Agents: The presence of hydrophilic polymers like hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), polyethylene oxide (PEO), or carbomers, or insoluble polymers like ethylcellulose, indicates a controlled-release formulation. The patent will often discuss different viscosity grades of these polymers and their impact on the drug release rate over 8, 12, or 24 hours. This reveals the innovator’s strategy to move from multiple daily doses to a more convenient once-daily regimen, a key lifecycle management tactic.

By creating a checklist of these functional excipient classes and scanning the “Detailed Description” and “Examples” sections of a patent, you can quickly build a profile of the API’s inherent weaknesses and the formulation strategy designed to overcome them.

Analyzing Excipient Concentrations and Ratios

It’s not enough to know what excipients are used; you need to know how much. Patents often provide ranges, but the real intelligence lies in the specific examples and the claimed ranges.

Consider a formulation for a moisture-sensitive drug. The patent might list a superdisintegrant like croscarmellose sodium. The “Examples” section might show three formulations with 2%, 4%, and 6% of this disintegrant, along with data showing that the tablet with 4% provides the fastest disintegration without compromising stability. The claims might then be narrowed to protect a formulation “comprising 3% to 5% by weight of croscarmellose sodium.”

This tells a story. The formulators likely found that at 2%, disintegration was too slow, and at 6%, the tablet absorbed too much atmospheric moisture, causing the API to degrade. The 3-5% range is the “sweet spot” they identified. For a competitor, this is invaluable. It saves you from repeating these same experiments and guides you toward a more promising starting point for your own development, perhaps using a different disintegrant like sodium starch glycolate, to design around the patent.

Furthermore, pay close attention to the ratio between key excipients, or between an excipient and the API. In an amorphous solid dispersion, the ratio of API to polymer is critical for maintaining the amorphous state. A patent for an injectable biologic will carefully specify the ratio of a stabilizing sugar (like sucrose) to a surfactant (like polysorbate 80) to prevent both aggregation and particle formation. These ratios are not arbitrary; they are the result of extensive optimization and are often the core inventive aspect of the formulation.

Case Study: Unpacking the Formulation of a Blockbuster Biologic

Let’s imagine analyzing the formulation patent for a hypothetical monoclonal antibody (mAb) called “Stabilimab.” The original composition of matter patent is nearing expiry, but a newer formulation patent provides another decade of protection.

- The Background: The patent starts by explaining that many mAbs, including Stabilimab, are prone to aggregation when formulated as a high-concentration liquid for subcutaneous injection. It mentions that previous formulations showed unacceptable levels of visible and sub-visible particles after 6 months of refrigerated storage. This immediately tells us the core problem: aggregation and particle formation in a high-concentration liquid formulation.

- The Detailed Description: It lists potential excipients. We see a buffer: histidine. We see a surfactant: polysorbate 20. We see a tonicity modifier: sodium chloride. But most interestingly, we see two stabilizers listed as “particularly preferred”: sucrose and arginine.

- The Examples:

- Example 1: A formulation with 100 mg/mL Stabilimab, 10 mM histidine buffer at pH 6.0, 9% sucrose, and 0.02% polysorbate 20.

- Example 2 (Comparative): The same formulation but without sucrose.

- Example 3: A formulation with 100 mg/mL Stabilimab, 10 mM histidine buffer at pH 6.0, 50 mM arginine, and 0.02% polysorbate 20.

- Example 4 (The “Winner”): A formulation with 100 mg/mL Stabilimab, 10 mM histidine buffer at pH 6.0, 5% sucrose, and 25 mM arginine, and 0.02% polysorbate 20.

- The Data: The patent provides stability data (using size-exclusion chromatography and micro-flow imaging) showing that Example 4 has significantly lower rates of aggregate and particle formation under both real-time and accelerated stress conditions compared to all other examples.

- The Claims: The independent claim protects “A stable aqueous pharmaceutical formulation comprising a monoclonal antibody, a histidine buffer, a polysorbate surfactant, sucrose, and arginine.”

The Intelligence Gained:

- The innovator’s core challenge was preventing aggregation at high concentrations.

- They found that neither sucrose nor arginine alone was sufficient.

- The synergistic combination of sucrose and arginine is the key inventive step.

- A competing biosimilar developer now knows that to enter the market, they must either (a) challenge the validity of this patent or (b) develop a stable, high-concentration formulation that does not use the combination of sucrose and arginine. They might investigate alternative stabilizers like trehalose or proline, for example. This is a clear, actionable strategic direction derived directly from the patent document.

Uncovering Novel Drug Delivery Systems

Beyond the specific ingredients, patents are a chronicle of the evolution of drug delivery technology. A company’s patent filings over time can show a clear progression from simple, conventional dosage forms to highly sophisticated systems designed to improve efficacy, safety, and patient compliance. This narrative is a powerful indicator of market trends and competitive pressures.

From Pills to Patches: Tracking Delivery Evolution

Consider the lifecycle of a successful drug for chronic pain.

- Initial Patent (Year 0): The composition of matter patent for the API. The examples might show a basic immediate-release (IR) tablet, intended for dosing 3-4 times per day.

- Second Patent (Year 5): A formulation patent for a 12-hour controlled-release (CR) tablet using an HPMC matrix. This reduces dosing frequency, improving convenience and likely adherence. This signals a move to capture the long-term therapy market.

- Third Patent (Year 9): A patent for a transdermal patch that delivers the drug over 72 hours. This is a significant technological leap, aimed at providing continuous pain relief and avoiding the gastrointestinal side effects associated with oral delivery.

- Fourth Patent (Year 12): A patent for an abuse-deterrent formulation (ADF) of the CR tablet, incorporating polymers that form a viscous gel when crushed and dissolved, making it difficult to inject. This is a direct response to regulatory and societal pressure to combat the opioid crisis.

By mapping these filings, a competitor sees a clear strategic path: improve convenience -> enhance safety -> address regulatory concerns. This timeline not only shows what the innovator has done but can also help predict what they might do next. Perhaps a tamper-resistant patch or a long-acting injectable is the next logical step in their lifecycle plan? Monitoring their new patent applications in these areas can confirm these suspicions.

Advanced Systems: Liposomes, Nanoparticles, and Controlled-Release Technologies

The cutting edge of formulation science is found in patents for advanced drug delivery systems. When you see these technologies mentioned, it signifies a major investment in overcoming significant biological barriers.

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Famously used for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, LNPs are a key enabling technology for delivering nucleic acids (like mRNA and siRNA). A patent for an LNP formulation will detail the specific lipids used (e.g., ionizable cationic lipids, helper lipids like cholesterol, PEGylated lipids) and their molar ratios. This is the secret sauce that protects the fragile genetic material and facilitates its entry into target cells. Analyzing these patents is essential for any company working in the gene therapy or vaccine space.

- Polymeric Micelles and Nanoparticles: These are used to encapsulate poorly soluble drugs, particularly in oncology, to target tumors through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Patents will describe the type of polymer (e.g., PLA, PLGA, PEG), the drug-loading efficiency, particle size distribution, and in vivo data demonstrating tumor accumulation.

- Drug-Eluting Stents and Implants: These patents combine medical device technology with formulation science. The claims will focus on the polymer coating applied to the stent or implant and the mechanism by which the drug (e.g., an anti-proliferative agent) is released over weeks or months to prevent tissue regrowth.

When you encounter patents for these complex systems, you’re looking at the forefront of R&D. The details within are a masterclass in advanced formulation, revealing solutions to some of the toughest challenges in medicine.

Revealing Stability and Shelf-Life Enhancement Techniques

A drug product is useless if it degrades before it can be administered. Stability is a non-negotiable requirement for regulatory approval and commercial success. Patents, particularly the examples section, are an open book on how innovators have battled instability.

Identifying Stabilizers, Buffers, and Preservatives

As discussed earlier, the mere presence of certain excipient classes tells a tale of instability.

- Buffers (e.g., Phosphate, Citrate, Histidine, TRIS): Their presence immediately tells you the API’s stability or solubility is highly pH-dependent. The patent will specify the target pH range, for example, “the formulation is buffered to a pH of between 6.0 and 6.5.” This is the optimal pH window for the drug’s survival. Any deviation can lead to rapid degradation or aggregation.

- Preservatives (e.g., Benzyl Alcohol, Phenol, m-Cresol): These are required for multi-dose injectable or ophthalmic formulations to prevent microbial growth after the vial has been opened. However, preservatives can also interact with the API, especially biologics, sometimes causing aggregation. Patents will often show data comparing the stability of the API in the presence of different preservatives, revealing which one was compatible. This is vital intelligence for a competitor developing a multi-dose version of the product.

- Cryo/Lyoprotectants (e.g., Sucrose, Trehalose, Mannitol): These are used in lyophilized (freeze-dried) formulations. The process of freezing and drying is extremely stressful for molecules, especially large proteins. These excipients form a glassy matrix that protects the API during the process and upon reconstitution. A patent for a lyophilized product reveals that the API was not stable enough to be marketed as a ready-to-use liquid, a significant finding for a competitor.

Interpreting Stability Data Presented in Patents

The “Examples” section is where you find the proof. Innovators must often provide data to support their claim that their new formulation is an improvement. This stability data is a gift to the competitive intelligence analyst.

Look for tables and figures showing the results of accelerated stability studies. The standard conditions are typically 40°C and 75% relative humidity for solid dosage forms. The patent will show how much of the API remains and how many degradation products have formed after 1, 3, and 6 months under these stress conditions.

By comparing the stability data for different formulations within the patent, you can quantify the benefit of the inventive step. For instance, you might see that a formulation with an antioxidant shows only 0.5% total impurities after 6 months at 40°C, while the same formulation without the antioxidant shows 5% impurities. This is hard evidence of an oxidation problem and its solution. This data can be used to build a “Quality Target Product Profile” (QTPP) for your own generic version, setting clear goals for your formulation team to meet or exceed.

Strategic Application of Formulation Intelligence

Gathering intelligence is only half the battle. The real value is realized when this information is translated into strategic action. The insights gleaned from patent analysis can inform critical business decisions, de-risk R&D programs, and create significant commercial advantages, whether you are an innovator or a generic developer.

For Generic and 505(b)(2) Developers: The Path to Market Entry

For companies looking to compete with established branded drugs, patent analysis isn’t just useful; it’s the foundation of the entire business model. The goal is to find a path to market that is both scientifically viable and legally defensible.

Designing Around Patents: The Art of Innovation

The most common strategy is to “design around” the innovator’s patents. This means creating a formulation that is bioequivalent to the branded product but does not literally infringe the claims of its formulation patents. The intelligence you’ve gathered is your guide.

Let’s revisit our “Stabilimab” case study. The innovator’s patent claims the synergistic combination of sucrose and arginine as stabilizers. Your mission, as a biosimilar developer, is to find an alternative. Your patent analysis has already told you the core problem is high-concentration aggregation. You can now direct your R&D team to explore other classes of stabilizers known to be effective for mAbs, such as:

- Alternative sugars: Trehalose, sorbitol.

- Alternative amino acids: Proline, glycine, histidine (at a different concentration or pH, if not claimed).

- Other GRAS (Generally Regarded as Safe) excipients: Certain polymers or cyclodextrins.

Your research is no longer a blind search; it’s a focused investigation into non-infringing solutions to a known problem. The patent has given you the problem definition for free. You can use services like DrugPatentWatch to monitor not only the key patents for your target drug but also the broader landscape of formulation technologies, helping you identify emerging, patent-free stabilization techniques that you could apply.

Identifying Weaknesses for Patent Challenges (Paragraph IV)

Under the Hatch-Waxman Act in the US, a generic company can challenge the validity of a branded drug’s patents. This is known as a Paragraph IV certification, where the generic applicant claims that the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by their product. Winning such a challenge can allow the generic to come to market before the patent expires, often with a lucrative 180-day period of market exclusivity.

Patent analysis is the first step in building a Paragraph IV case. You might uncover:

- Prior Art: The “Background” section of the patent might have missed a crucial scientific paper or an earlier patent that disclosed a similar formulation concept. If you can prove the invention was not truly “novel” or “non-obvious” at the time of filing, the patent can be invalidated.

- Lack of Enablement: Does the patent actually teach how to make the claimed formulation work across its entire scope? Sometimes claims are written very broadly. If you can show that making the formulation is only possible under a very narrow set of conditions described in the examples, but not across the full breadth of the claim, you can argue the patent is not enabled.

- Insufficient Written Description: Do the claims cover embodiments that are not adequately described in the specification? For example, if the claims cover a whole class of polymers, but the examples only show data for one, you might be able to challenge the claim’s breadth.

A thorough patent analysis, often in conjunction with patent attorneys, can identify these potential weaknesses, providing the foundation for a legal challenge that could accelerate your market entry by years.

Leveraging Expired Formulation Patents as a Starting Point

Not all patents are a barrier. Some can be a roadmap. The IP landscape around a drug is dynamic. A first-generation formulation patent might expire years before the later-generation patents.

For example, a branded drug might have an expired patent on a simple HPMC-based controlled-release tablet. The currently marketed version might be a more complex, multi-layered tablet protected by newer patents. A generic company could choose to ignore the complex version and instead use the teachings of the expired patent to develop a simpler, but still bioequivalent, controlled-release product. The expired patent becomes a public-domain recipe, providing a validated and well-documented starting point for development, significantly reducing R&D time and risk.

For Innovator Companies: Competitive Benchmarking and Lifecycle Management

Patent intelligence is not just for generics. For innovator companies, systematically monitoring competitors’ patent filings is a crucial form of competitive intelligence that can shape R&D, business development, and long-term strategy.

Monitoring Competitor R&D and Anticipating Market Moves

Patent applications are typically published 18 months after they are filed. This creates a window of insight into a competitor’s pipeline long before they announce clinical trial results or present at a conference.

By analyzing the formulation patents being filed by your key competitors, you can:

- Identify their new targets: Are they suddenly filing patents for oral formulations of peptides, which are traditionally injected? This signals a strategic move into a new technology platform.

- Understand the challenges they are facing: If a competitor files multiple formulation patents for the same API, each attempting to solve a solubility problem in a different way (e.g., first trying micronization, then solid dispersions, then lipid systems), it tells you they are struggling to find a viable path forward.

- Anticipate their next-generation products: Is a competitor with a successful once-daily tablet now filing patents on a weekly injectable or a monthly implant for the same drug? This is a clear signal of their lifecycle management strategy, and you can begin to plan your competitive response years in advance.

This “patent-forward” view of the competitive landscape allows you to be proactive rather than reactive.

Identifying “White Space” for New Formulation IP

“White space” analysis involves mapping the existing patent landscape for a particular technology or drug class to identify areas that are not protected. By understanding what your competitors have patented, you can strategically direct your own R&D into unexplored territory, creating novel, patentable formulations that give you a unique market position.

For example, imagine you are developing a drug in a crowded therapeutic area. Your analysis shows that all existing competitors use oral solid dosage forms. However, you also know that many patients in this population have difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). This identifies a “white space”: there is an unmet need and no IP blocking the development of a patient-friendly oral liquid, sublingual film, or orally disintegrating tablet. You can focus your formulation team on this specific goal, knowing that a successful outcome will be both clinically meaningful and commercially protectable.

The Power of Evergreening: Building a Patent Thicket Around a Core Product

This is the art of strategic patenting that all innovator companies practice. By continuously innovating on the formulation and delivery of a drug, companies can file new patents that extend its commercial life well beyond the expiration of the original composition of matter patent.

A deep understanding of the formulation landscape, derived from analyzing both your own and your competitors’ patents, is essential for a successful evergreening strategy. It allows you to ask strategic questions:

- What is the next logical improvement for our product? A higher concentration? A preservative-free version? A room-temperature stable formulation?

- What emerging drug delivery technologies could we apply to our API to create a truly differentiated next-generation product?

- Where are the weaknesses in our current patent portfolio? Do we need to file new patents to better protect our commercial formulation from design-around attempts?

A well-executed lifecycle management strategy, informed by robust patent intelligence, can add hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars to the total revenue of a blockbuster drug.

Tools and Methodologies for Systematic Patent Analysis

While manually reading individual patents is the core skill, it’s not scalable for comprehensive landscape analysis. In today’s data-driven world, leveraging specialized tools and advanced methodologies is essential to efficiently navigate the millions of patents in existence and extract meaningful, strategic insights.

Leveraging Professional Patent Databases and Analytics Platforms

Free patent search engines like Google Patents or the USPTO’s Patent Public Search are excellent for looking up a specific patent number or doing a simple keyword search. However, for serious competitive intelligence, professional-grade tools are a necessity.

Platforms like Derwent Innovation, PatBase, or Orbit Intelligence offer powerful features, including:

- Global Coverage: Access to patent documents from over 100 patenting authorities worldwide, translated into English.

- Patent Families: Grouping all patents related to a single invention filed in different countries into one family, simplifying analysis.

- Advanced Search Capabilities: Sophisticated Boolean search logic, semantic search, and the ability to search non-text fields like chemical structures.

- Analytics and Visualization: Tools to create patent landscape maps, identify key assignees and inventors, and track filing trends over time.

The Role of Services like DrugPatentWatch

For professionals focused specifically on the pharmaceutical industry, specialized services offer a more curated and targeted approach. Platforms such as DrugPatentWatch are designed to bridge the gap between raw patent data and actionable business intelligence. Instead of just being a search engine, these services provide structured data and analysis on drug-patent linkage.

For example, a service like this can provide you with a comprehensive list of all patents associated with a specific branded drug, including their types (composition of matter, formulation, method of use), their estimated expiration dates (including any patent term extensions or adjustments), and details of any litigation (like Paragraph IV challenges). This saves an enormous amount of time and effort compared to manually assembling this information from disparate sources. These platforms are invaluable for generic and biosimilar companies planning their pipeline, for brand managers tracking their competitive landscape, and for business development professionals scouting for licensing or acquisition opportunities. They essentially pre-process the complex IP landscape into a format that directly answers key business questions.

Using Keywords, Classifications, and Assignee Searches Effectively

Regardless of the tool you use, effective searching is a skill.

- Keyword Searches: Be specific. Instead of searching for “formulation,” search for terms related to the technologies you’re interested in, like “amorphous solid dispersion,” “lipid nanoparticle,” “taste masking,” or “controlled release.” Combine these with the API name or drug class.

- Classification Searches: Patents are categorized using systems like the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC). For example, classification A61K 9/00 covers “Medicinal preparations characterized by special physical form.” Learning the relevant CPC codes for different formulation types can yield much more precise results than keyword searches alone.

- Assignee Searches: This is the most direct way to monitor a specific competitor. Regularly run searches for all new patent applications filed by your key rivals. Set up alerts so you are notified automatically when they file something new.

Applying Text Mining and AI for Deeper Insights

The sheer volume of text in patents makes them ripe for analysis by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. These emerging technologies can uncover trends and connections that would be impossible for a human to spot.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) to Extract Formulation Data

NLP algorithms can be trained to read and understand the text of patents. They can be programmed to automatically extract specific pieces of information, such as:

- All excipients mentioned in a patent.

- The concentration ranges for each excipient.

- The specific API-to-polymer ratios used in examples.

- The stability and dissolution data presented in tables.

By running such an algorithm across thousands of patents in a given field, you can rapidly build a structured database of formulation data. This allows you to perform large-scale analyses, such as identifying the most commonly used solubility enhancers for a particular class of APIs or mapping the evolution of preservative use in ophthalmic solutions over the past two decades.

Visualizing Data: Patent Landscapes and Trend Analysis

The output of these searches and AI analyses can be overwhelming. Data visualization is key to making it understandable.

- Patent Landscape Maps: These are often topographical maps where patents are grouped into clusters based on their textual similarity. Peaks on the map represent crowded areas with lots of patenting activity, while open plains represent “white space” with little IP. This gives you an intuitive, at-a-glance view of the entire technology area.

- Trend Analysis Graphs: You can plot patent filings over time for a specific technology or company. Is the number of patents for oral biologics increasing? Is your competitor’s patent filing rate accelerating or declining? These trend lines can visualize strategic shifts in the industry.

- Citation Networks: Analyzing which patents cite each other can reveal the foundational inventions in a field and show how innovation has built upon earlier discoveries. It can also identify the most influential companies and inventors.

By combining powerful search tools, AI-driven text mining, and intuitive data visualization, you can elevate your patent analysis from a document-by-document review to a comprehensive, data-backed strategic intelligence function.

The Legal and Regulatory Context: Navigating the Maze

A discussion of patent strategy would be incomplete without acknowledging the complex legal and regulatory framework in which it operates. The insights you gain from patents must always be viewed through the lens of what is legally permissible and commercially viable. A brilliant “design-around” formulation is useless if it can’t get regulatory approval or if it inadvertently infringes a different, overlooked patent.

Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis: A Crucial Due Diligence Step

Before investing significant resources into developing a new product, whether it’s a generic, a biosimilar, or a new innovator drug, conducting a Freedom to Operate (FTO) analysis is essential. An FTO is a comprehensive search and analysis of third-party patent rights to determine if your proposed product is at risk of infringing any existing, in-force patents.

The formulation intelligence you’ve gathered is a key input to the FTO process. Your proposed formulation—the API, the excipients, their concentrations, the manufacturing process—must be carefully checked against the claims of all relevant patents. This is not something to be done casually; it requires the expertise of qualified patent attorneys. They will provide a legal opinion on the level of risk. An FTO analysis can:

- Give you a green light: Concluding that the risk of infringement is low.

- Identify specific blocking patents: Highlighting the patents you would need to license, invalidate, or design around.

- Guide your R&D: Suggesting specific modifications to your formulation to reduce infringement risk.

Ignoring FTO is a gamble that can lead to costly litigation, injunctions that halt your product launch, and potentially massive damages.

Understanding Patent Scope and Claim Interpretation

The legal power of a patent resides entirely in its claims. However, the precise meaning of the words in a claim is often the subject of intense legal debate. Claim construction, or “Markman hearings,” are a critical part of patent litigation where a judge determines the legal scope of the claims.

For example, a claim might recite a formulation “comprising” certain ingredients. “Comprising” is an open-ended term meaning “including but not limited to.” This means a formulation that contains the listed ingredients plus an additional one could still infringe. In contrast, if the claim used the word “consisting of,” it would be closed-ended, and any additional ingredient would take the formulation outside the claim’s scope.

Another key concept is the “doctrine of equivalents.” This legal principle states that a product can infringe a patent even if it does not fall within the literal scope of the claims, as long as it performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way to achieve the same result. This prevents competitors from making insignificant changes to a formulation simply to avoid literal infringement.

Understanding these legal nuances is crucial. Your scientific analysis might suggest a clear design-around opportunity, but a patent attorney is needed to assess whether that design-around would be considered “equivalent” in a court of law.

The Impact of the Hatch-Waxman Act and BPCIA

The legal landscape for small-molecule drugs and biologics in the US is largely defined by two landmark pieces of legislation:

- The Hatch-Waxman Act (for small-molecule drugs): This act created the framework for generic drug approval (the ANDA pathway) and the associated patent litigation system, including Paragraph IV challenges and the 180-day exclusivity period for the first successful challenger. It masterfully balances the interests of innovator companies (by offering patent term extensions to compensate for time lost during clinical trials and regulatory review) and generic companies (by creating an abbreviated path to market).

- The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA): This is the equivalent of Hatch-Waxman for biologic drugs, creating an abbreviated approval pathway for “biosimilars.” The BPCIA has its own unique and highly complex process for patent litigation, often referred to as the “patent dance,” which involves a series of information exchanges and negotiations between the biosimilar applicant and the innovator company.

A deep understanding of the specific provisions of these acts is essential for any company operating in the US pharmaceutical market. They dictate the timelines, the legal strategies, and the commercial opportunities associated with bringing a generic or biosimilar product to market. Your formulation and patent analysis must be conducted within the strategic context created by these laws.

Conclusion: From Data to Dominance

We began this journey by challenging the conventional view of a patent as a mere legal barrier. Throughout this exploration, we have deconstructed that barrier and reassembled it as a strategic blueprint—a rich source of competitive intelligence that is hiding in plain sight. We have seen how the dry, technical language of a patent document can tell a vivid story of scientific struggle and strategic triumph.

By learning the anatomy of a patent, we can pinpoint the sections that hold the most valuable data. By understanding the different types of patents, we can piece together a company’s entire lifecycle strategy for its most valuable assets. We have transformed from passive observers into active decoders, learning to read between the lines to identify the critical formulation challenges—poor solubility, instability, low bioavailability—that an innovator faced and, more importantly, how they solved them. The specific choices of excipients, their concentrations, and the advanced delivery systems employed are no longer just a list of ingredients; they are clues to a puzzle, revealing the “why” behind the “what.”

This intelligence is not an academic curiosity. It is a potent catalyst for business strategy. For generic and biosimilar developers, it is the compass that guides them toward non-infringing formulations and illuminates the weaknesses in a competitor’s patent fortress. For innovator companies, it is a periscope that allows them to see the R&D direction of their rivals, benchmark their own efforts, and identify the “white space” for future innovation.

In the relentless race for market share in the pharmaceutical industry, the companies that will win are not necessarily those with the biggest R&D budgets, but those that are the smartest. They are the ones who leverage every available source of information to make better, faster, and less risky decisions. By mastering the art of using drug patents to reveal formulation strategies, you are equipping your organization with a decisive edge. You are turning public data into private knowledge, and private knowledge into market dominance. The code is there for the cracking.

Key Takeaways

- Patents are More Than Legal Documents: They are rich technical disclosures that provide a roadmap to a competitor’s formulation strategies, challenges, and R&D direction.

- Anatomy is Key: Understanding the structure of a patent (Abstract, Background, Detailed Description, Claims, Examples) allows you to efficiently extract the most valuable information from each section. The “Examples” and “Detailed Description” are formulation goldmines.

- Excipients Tell a Story: The choice of excipients (e.g., solubility enhancers, stabilizers, controlled-release polymers) is a direct reflection of the problems formulators faced with the API. Analyzing them reveals the API’s inherent weaknesses.

- Strategy is Revealed in Patent Portfolios: A company’s portfolio of patent types (composition of matter, formulation, method of use, process) and their filing timeline reveals its long-term lifecycle management and market expansion strategies.

- Actionable for Both Sides: Generic/biosimilar developers can use patent intelligence to design around existing patents, identify weaknesses for legal challenges (Paragraph IV), and leverage expired patents. Innovators can use it for competitive benchmarking, identifying “white space,” and building their own robust patent thickets.

- Tools Magnify Insight: Professional databases, specialized services like DrugPatentWatch, and AI-powered text mining tools are essential for conducting efficient, large-scale patent landscape analysis.

- Legal Context is Crucial: All formulation intelligence must be interpreted within the legal and regulatory framework, including Freedom to Operate (FTO) analysis and the specific rules of the Hatch-Waxman Act and the BPCIA.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How can I tell which formulation “example” in a patent is the one that was actually commercialized?

This is a critical question. While a patent may list 10-20 examples, you can often deduce the commercial formulation through corroborating evidence. First, look for the “preferred embodiment” as described in the patent text—the authors often signal which one worked best. Second, and more definitively, compare the patent’s examples to the drug’s publicly available prescribing information or summary of product characteristics (SmPC). These regulatory documents list the excipients present in the final approved product. By matching the excipient list from the prescribing information to a specific example in the patent, you can identify the commercialized formulation with a high degree of confidence.

2. A key formulation patent for my target drug doesn’t expire for another 8 years. Is there any point in analyzing it now?

Absolutely. Eight years is a relatively short timeframe in pharmaceutical R&D. Analyzing it now is crucial for several reasons. It allows you to: (a) begin early-stage “design-around” R&D so that you have a non-infringing alternative ready to go well before patent expiry; (b) initiate a thorough analysis for a potential Paragraph IV patent challenge, a process that can take years; (c) understand the “state of the art” so you can potentially develop a “next-generation” product that improves upon the innovator’s technology and could be launched upon their patent expiry; and (d) avoid surprises by fully understanding the IP hurdles you will face long before you commit significant development capital.

3. Our company is small and can’t afford expensive patent attorneys for every analysis. What’s the most valuable ‘first-pass’ analysis our R&D team can do themselves?

Your R&D team can derive immense value by focusing on the scientific, not legal, aspects. The most valuable “first-pass” analysis involves:

- Identifying all formulation and method-of-use patents related to the target drug using free or specialized databases.

- Focusing on the “Examples” section of the most relevant patents to identify the key functional excipients and the problem they were intended to solve (e.g., “they used Soluplus, so the API must have poor solubility”).

- Replicating the innovator’s “best” example in your own lab (on a for-research basis) to understand its properties and challenges firsthand.

- Brainstorming scientifically viable “design-around” strategies based on this understanding.This scientific due diligence provides a strong foundation and allows you to engage with patent attorneys later in the process with highly specific, well-informed questions, making that engagement far more efficient and cost-effective.

4. The patent claims are written in very broad, confusing language. How can I get a clearer picture of what’s actually protected?

Claim interpretation is complex, but you can get a better picture by looking at the “prosecution history” or “file wrapper” of the patent, which is publicly available through patent office websites. This file contains all the correspondence between the inventor’s attorney and the patent examiner. You can see the examiner’s rejections of initial, broader claims and the arguments the attorney made to get the patent allowed. This back-and-forth often forces the applicant to clarify or narrow the scope of their claims, providing a much clearer definition of the protected invention than the final claim language alone.

5. We see a competitor filing patents on a new delivery technology, but we’re not sure if it’s for any of their existing drugs. How can we figure out their strategy?

This is a classic competitive intelligence challenge. While the patent application may not name a specific drug, it often provides clues. Look at the physicochemical properties of the example “model compounds” used in the patent—are they lipophilic, high molecular weight, or a biologic? This can help you match the technology to a drug in their pipeline with similar properties. Furthermore, look at the inventors listed on the patent. Are they part of the team that developed a specific blockbuster drug? This can link the new technology to a lifecycle management plan for that product. Finally, monitoring their clinical trial registry filings (e.g., on ClinicalTrials.gov) may reveal a new study for an old drug using a new dosage form, connecting the dots between the patent filing and a specific product strategy.

References

[1] Williams, H. D., Trevaskis, N. L., Charman, S. A., Shanker, R. M., Charman, W. N., Pouton, C. W., & Porter, C. J. (2013). Strategies to address poor solubility in discovery and development. Pharmacological Reviews, 65(1), 315-499.