The Multi-Billion Dollar Reverse Flow: Deconstructing the Pharmaceutical Returns Landscape

Introduction: From Operational Nuisance to Strategic Imperative

In the pharmaceutical industry, the forward supply chain—the journey of a drug from manufacturing to patient—has been the subject of intense optimization, investment, and strategic focus for decades. However, its shadow counterpart, the reverse supply chain, has often been relegated to the status of an operational nuisance, a mere “cost of doing business.” This perspective is not only outdated but financially perilous. The flow of returned pharmaceutical products represents a significant, multi-billion dollar financial variable that directly impacts corporate profitability, regulatory compliance, and the very funding of future innovation. Ignoring its strategic importance is a luxury the modern pharmaceutical enterprise can no longer afford.

The scale of the market contextualizes the magnitude of the returns challenge. The global pharmaceutical market is a colossal entity, valued at USD 1.67 trillion in 2024 and projected to swell to an astonishing USD 3.03 trillion by 2034.1 North America stands as the dominant region within this landscape, with a market size valued at USD 799.67 billion in 2024 alone.2 Within this vast commercial ecosystem, the reverse flow of goods is not a trivial trickle but a substantial current. A landmark report from the Healthcare Distribution Alliance (HDA) Research Foundation quantifies the value of products moving through the reverse distribution process at over

$13 billion annually. This staggering figure corresponds to more than 120 million individual product units being sent backward through the supply chain each year.3 This is not an accounting rounding error; it is a massive financial stream, laden with both risk and opportunity, that demands sophisticated management, rigorous control, and, most critically, accurate forecasting. Understanding, predicting, and mitigating this reverse flow has become an essential pillar of financial fitness for every pharmaceutical manufacturer.

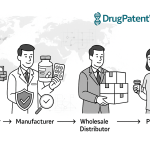

The Anatomy of a Return: The Reverse Distribution Process

The journey of a returned pharmaceutical product is a complex, highly regulated process that stands in stark contrast to the linear path of forward distribution. This process, formally known as “reverse distribution,” involves a coordinated effort among pharmacies, wholesalers, specialized third-party logistics providers, and the original manufacturers to ensure that unsaleable products are handled safely, efficiently, and in full compliance with a web of federal and state regulations.5

The process typically unfolds across several distinct stages:

- Identification and Segregation at the Dispenser Level: The lifecycle of a return begins at the pharmacy, hospital, or clinic. Staff must meticulously inspect inventory on shelves, in refrigerators, and in vaults to identify products that are unsaleable. This category primarily includes drugs that are expired or nearing their expiration date, have been recalled by the manufacturer or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), or have been damaged.6 Once identified, these products are segregated from active, saleable inventory to prevent accidental dispensing and to prepare them for processing.

- Engagement with a Reverse Distributor: Rather than managing the labyrinthine complexity of returning products to hundreds of different manufacturers, most dispensers contract with a specialized third-party reverse distribution company, such as Pharma Logistics or Return Logistics International.5 These firms act as central consolidators and processors, simplifying the process for the pharmacy and ensuring regulatory compliance.8

- Shipment and Processing: The segregated products are inventoried, often using a web portal provided by the reverse distributor, and then shipped to the third party’s secure facility.6 Upon arrival, the reverse distributor undertakes the critical task of sorting and processing. Products are batched and sorted by their original manufacturer. Each item is then evaluated against that specific manufacturer’s returned goods policy to determine its eligibility for credit.5 These policies are highly variable and can dictate the return window (e.g., up to 12 months past expiration), the condition of the product (e.g., unopened original packaging), and which product types are ineligible for credit (e.g., injectables, partial containers of generics).6

- Credit Reconciliation and Final Disposition: For products deemed returnable, the reverse distributor sends them to the manufacturer or the manufacturer’s designated processor and manages the Return Goods Authorization (RGA) process.5 The manufacturer then issues a credit, which typically flows back to the wholesaler from which the product was originally purchased. The wholesaler, in turn, passes the credit to the reverse distribution company, which finally issues payment or credit to the pharmacy.5 Products that are not eligible for credit, or those that pose a safety or environmental risk, are handled for final disposition. This includes the compliant destruction of controlled substances, which must adhere to strict Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) protocols, and the disposal of hazardous materials according to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations.5

While outsourcing this process provides significant operational efficiencies and ensures specialized compliance, it also introduces a strategic challenge. The act of handing off the physical management of returns can create a data and control gap for the manufacturer. The third-party processor’s primary function is the efficient execution of the steps above—reconciling credits and ensuring compliant disposal. Their core business is not necessarily to provide the manufacturer with deep, real-time, root-cause analysis for why a particular product is being returned at a specific velocity from a certain region. This potential for data lag or abstraction means that underlying problems—such as a flaw in a regional demand forecast, an ineffective sales incentive program, or an unforeseen product stability issue—may not become fully visible to the manufacturer until they manifest as a significant and unexpected financial charge on the quarterly earnings report. This reliance on an external partner for execution paradoxically increases the importance of the manufacturer’s internal forecasting capability. The problem cannot be simply managed by the vendor; it must be accurately predicted by the manufacturer to protect the financial integrity of the organization.

The Core Drivers of Returns: A Taxonomy of Unsaleable Goods

The multi-billion dollar stream of returned pharmaceuticals is fed by several distinct tributaries. Understanding this taxonomy of drivers is the first step toward developing targeted forecasting models and mitigation strategies. While often grouped under the single heading of “unsaleable,” the root causes are varied, each carrying unique financial implications and demanding a different analytical approach.

- Product Expiration: This is the most significant, predictable, and persistent driver of returns. In 1978, federal law was changed to mandate that prescription drug products carry expiration dates, a practice that has since been extended to most over-the-counter medications.11 This date, established through rigorous stability testing and approved by the FDA, reflects the time period during which a product is known to retain its strength, quality, and purity when stored under labeled conditions.12 Once a drug passes its expiration date, its chemical composition can change, potentially reducing its efficacy or, in rare cases, leading to the formation of toxic compounds.12 Consequently, expired drugs are a primary source of unsaleable inventory. Manufacturer policies typically allow for the return of products within a specific window around the expiration date, often from six months prior to up to twelve months after expiration, to facilitate the removal of this stock from pharmacy shelves and recoup a portion of its value.6

- Product Recalls and Market Withdrawals: These events represent an acute and often costly driver of returns. A recall is initiated in response to a significant consumer safety concern, such as contamination, mislabeling, or the discovery of a harmful side effect.14 The FDA oversees and classifies recalls based on the level of health hazard. A Class I recall, the most serious, is issued when there is a reasonable probability that the use of the product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death.15 These urgent events can require the removal of the product down to the consumer level, triggering a complete and immediate purge from the entire supply chain. A market withdrawal, by contrast, is typically initiated by the manufacturer for a minor violation that does not warrant FDA legal action, but it still involves removing the product from the market.14 Both recalls and withdrawals create a sudden, un-forecasted surge of returns that can overwhelm the reverse logistics system and carry substantial direct and indirect costs.16

- Product Damage and Improper Storage: The pharmaceutical supply chain is a long and complex journey, and products are vulnerable to damage at every stage, from the manufacturer’s warehouse to the wholesaler’s distribution center to the final point of care.7 Beyond simple physical damage, exposure to improper environmental conditions represents a critical and often irreversible cause for a product to become unsaleable. The FDA’s CGMP regulations are unequivocal on this point: drug products that have been subjected to improper storage conditions, including extremes in temperature, humidity, smoke, or radiation, “shall not be salvaged and returned to the marketplace”.17 This means a failure in a refrigerated storage unit or a temperature excursion during transit can result in a total financial loss for the affected inventory.

- Demand and Supply Mismatches: This broad category encompasses a range of systemic issues where the supply of a drug in the channel exceeds actual patient demand. The drivers are multifaceted:

- Patient-Level Dynamics: Demand can be volatile due to factors beyond a manufacturer’s control. A physician may switch a patient to a different course of treatment, a patient may cease their therapy due to non-compliance, or they may simply choose to fill their prescription at a different pharmacy.18

- Competitive Pressures: In therapeutic areas with multiple treatment options, aggressive competition among retailers for patients’ business can lead to overstocking as a defensive measure to avoid losing a sale.18

- New Product Launches: To encourage distributors and pharmacies to stock a new, unproven drug, manufacturers have historically created returned goods policies that offer credit for any unsold product. While this practice facilitates market entry, it inherently builds the cost and volume of future returns directly into the launch strategy.18

The following table provides a structured overview of these primary drivers, linking their operational causes to their distinct financial consequences, and setting the foundation for the detailed financial analysis to follow.

Table 1: Primary Drivers of Pharmaceutical Product Returns and Their Financial Implications

| Driver | Primary Cause | Direct Financial Impact | Indirect Financial Impact |

| Expiration | Inaccurate demand forecasting; Poor inventory rotation | Credit issuance; Third-party processing fees; Destruction costs | Lost revenue opportunity on expired units; Strain on working capital |

| Recall | Manufacturing defect; Contamination; Adverse event discovery | Product replacement costs; Logistics for mass return; Administrative costs of recall management | Brand reputation damage; Litigation costs; Regulatory fines; Stock value decline |

| Damage/Improper Storage | Supply chain failure; Equipment malfunction; Human error | Total inventory write-off (unsalvageable); Replacement costs | Potential for drug shortages; Investigation and remediation costs |

| Demand Mismatch | Poor inventory management; Patient non-compliance; Competitive overstocking | Credit issuance for unsold goods; Increased handling and storage costs | Inefficient capital allocation; Lost sales due to stock-outs of other products |

| Patent Loss of Exclusivity (LoE) | Generic/biosimilar competition | Massive spike in returns of unsold branded inventory; Credits issued at potentially inflated prices | Accelerated revenue decline; Erosion of market share |

The Financial Black Hole: Quantifying the Impact of Returns on the Bottom Line

Gross-to-Net (GTN) Erosion: The Epicenter of Financial Impact

To comprehend the profound financial consequences of product returns, one must first understand their central role in the Gross-to-Net (GTN) revenue calculation. For pharmaceutical manufacturers, GTN is not merely an accounting exercise; it is the crucible where list prices are transformed into actual, recognized revenue. It represents the critical difference between a company’s gross sales revenue, typically calculated at the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) or list price, and the final net revenue that appears on the income statement after a cascade of deductions.19 These deductions—which include government and commercial rebates, wholesaler chargebacks, distribution fees, and, critically, provisions for product returns—are substantial. In some cases, the total value of GTN adjustments can erode the gross price of a drug by as much as 70%.20

Product returns are a direct and potent agent of this erosion. When a pharmacy or wholesaler returns a product for credit, the transaction effectively reverses the initial sale. Under modern revenue recognition standards, such as ASC 606, companies are required to estimate and reserve for these future returns at the moment the initial revenue is recognized.21 Units returned from the channel that are damaged, expired, or otherwise cannot be resold are treated as a direct deduction from gross revenue.23 The financial impact can be illustrated with a simple example: for a product generating $10 million in gross revenue, a returns provision of just $200,000 immediately reduces the potential net revenue by 2% from this single factor.23 For a multi-billion dollar blockbuster drug, this seemingly small percentage translates into tens of millions of dollars in direct revenue reduction.

The challenge is compounded by the fact that these deductions are not static; they are estimates of future events, making the accuracy of the underlying forecast paramount. An error in this forecast does not simply result in an inventory discrepancy; it can lead to a material misstatement of a company’s recognized revenue, a serious issue that invites intense scrutiny from auditors and regulators.

“When a CFO hears about financial statement errors, the first thing that comes to mind is the risk of material restatement of prior period financials. However, in the GTN world, financial statement errors are synonymous with GTN accrual true-ups… Prior period GTN true-ups are reported in a public company’s 10-K and 10-Q, and result in heavy scrutiny by auditors.” 24

This connection between forecasting accuracy and financial reporting integrity elevates the issue to the highest levels of corporate governance. A failure to accurately predict and reserve for returns is not just a supply chain problem; it is a direct threat to the credibility of a company’s financial statements.

Furthermore, the financial damage caused by an error in returns forecasting is uniquely amplified compared to a similar error in forward demand forecasting. A 10% over-forecast of demand might lead to a corresponding 10% increase in manufacturing and inventory carrying costs—a linear and relatively predictable financial impact. However, a 10% under-forecast of returns has a more pernicious, non-linear effect on the profit and loss statement. The product that is unexpectedly returned was already recognized as gross revenue. Its return forces a reversal of that revenue, effectively erasing a sale that was already booked. In addition to this revenue reversal, the company now incurs a host of new, unbudgeted costs for the reverse logistics, processing, and destruction of that same unit. The situation is exacerbated in the period leading up to a drug’s patent expiry, where manufacturers often implement price increases. Because return credit is frequently based on the current WAC, not the original sale price, a company can find itself issuing a credit for a returned product that is significantly higher than the price at which it was initially sold, transforming a once-profitable unit into a definitive net loss.25 This amplification effect makes an error in returns forecasting disproportionately more damaging than an equivalent error in forward logistics, elevating the practice from a simple inventory management task to a critical function of profit protection.

Beyond the Credit Memo: The Hidden Costs of Reverse Logistics

The financial impact of product returns extends far beyond the direct cost of the credit memo issued to the channel. A complex and often poorly tracked ecosystem of secondary costs emerges, creating a “financial black hole” that can consume resources and erode profitability in ways that are not immediately apparent on the face of the income statement. These costs can be broadly categorized into direct and indirect expenses.

The direct costs are the tangible, quantifiable expenses associated with the physical management of the reverse supply chain. These include the logistical costs of product recovery and transportation from thousands of points of care back to a central processing facility, the fees paid to third-party reverse distributors, and the final costs of compliant product destruction, which can be substantial for hazardous materials or controlled substances.16 Added to this are the significant internal administrative costs—the hours spent by personnel in finance, quality assurance, legal, and supply chain departments to manage the documentation, reconciliation, and compliance aspects of the returns process, which can extend for years in the case of a major recall.16

More significant, however, are the indirect costs, which are often larger and more damaging to the long-term health of the enterprise. These include:

- Lost Sales and Market Share: When a product is recalled or out of stock due to returns-related inventory issues, sales are immediately lost. More critically, this creates an opportunity for competitors to capture that market share, which can be difficult and expensive to win back.16

- Production Disruptions: A large-scale recall can force the shutdown of manufacturing lines, rescheduling of production runs, and reallocation of resources, creating widespread operational inefficiency.16

- Brand and Reputation Damage: In the age of instant information, a product recall, particularly one related to safety, can inflict lasting damage on a brand’s reputation and erode patient and physician trust.16 A 2014 consumer poll found that after a recall, 21% of consumers would not buy any brand associated with the recalling manufacturer again.27

- Litigation and Fines: Product recalls frequently lead to costly litigation from consumers and shareholders, as well as potential fines from regulatory bodies.16

- Stock Value Decline: The announcement of a major product recall or a significant earnings miss due to unexpected returns can have an immediate and negative impact on a company’s stock price.27

The cumulative financial impact of these hidden costs is enormous. While specific to the pharmaceutical industry, broader research from Deloitte into the consumer goods sector provides a sense of scale, estimating that “unsaleable” shipments, a category that includes damages and expirations, account for an average of 0.83% of gross sales. For an industry of this size, this translates to a staggering $15 billion annually in lost value.28 A single product launch delay in Switzerland, which necessitated the rework and return of mislabeled product, was estimated to have cost the manufacturer between €517 million and €620 million in lost market share and opportunity costs.16 These figures underscore that the true cost of returns is a multifaceted financial burden that requires comprehensive tracking and strategic management.

The R&D Equation: How Returns Forecasting Impacts Innovation and ROI

The financial leakage caused by product returns does not exist in a vacuum; it directly threatens the core business model of the entire research-based pharmaceutical industry. This model is predicated on a high-risk, high-reward cycle of innovation. Companies invest vast sums of capital over long periods to fund research and development (R&D), with the expectation that the revenues from a few successful “blockbuster” drugs will be sufficient to cover the costs of the numerous failures inherent in the drug discovery process and to fund the next generation of innovation.29

The scale of this investment is immense. The pharmaceutical industry spent $83 billion on R&D in 2019, a figure that, when adjusted for inflation, is approximately ten times the annual expenditure in the 1980s.30 The average capitalized cost to develop a single new drug and bring it to market is now estimated to be between $1 billion and more than $2.3 billion.30 This high-stakes financial model depends entirely on the ability to generate a sufficient return on these investments. However, the industry’s return on investment (ROI) from R&D has been under significant pressure for over a decade. According to Deloitte’s annual analysis, the projected internal rate of return (IRR) for the top 20 biopharma companies hit a record low of 1.2% in 2022 before recovering modestly to 5.9% in 2024, a fragile recovery at best.31

This context reveals the true strategic threat posed by product returns. The entire pharmaceutical business model can be viewed as a high-risk portfolio investment strategy, where the massive, long-term success of a few assets must compensate for the total loss of many others. The financial viability of this entire enterprise hinges on maximizing the net revenue generated by those successful blockbuster drugs during their period of market exclusivity. Product returns act as a direct and significant leakage from this absolutely critical revenue stream. When the forecasting of these returns is inaccurate, the company’s entire financial plan—its projections for cash flow, its earnings guidance to investors, and its capital allocation strategy—is built on a foundation of flawed assumptions about its capital inflows.

A sudden, un-forecasted spike in returns, such as the one that inevitably follows a patent cliff, can create a cash flow crisis that has immediate and severe consequences for the R&D pipeline. The capital required to fund ongoing, multi-million dollar Phase III clinical trials is not discretionary. A shortfall in projected revenue can force a company to make difficult decisions, such as delaying a promising trial, divesting a pipeline asset at an unfavorable valuation, or cutting back on early-stage discovery research. Therefore, the accurate forecasting of product returns is not merely about financial reporting hygiene or inventory management. It is a fundamental component of strategic capital allocation and a critical safeguard for the company’s innovation engine and its long-term viability.

Navigating the Gauntlet: Operational and Regulatory Challenges in Returns Management

The Reverse Supply Chain: A High-Stakes Logistical Puzzle

The operational management of pharmaceutical returns presents a set of challenges that are fundamentally different and more complex than those of the forward supply chain. While forward logistics is a system designed for efficiency, predictability, and speed in delivering products to market, reverse logistics must contend with uncertainty, variability, and significant risk at every step.34 The process is inherently more complicated due to the lack of clear forecasting for the quantity, quality, and timing of incoming returned goods.35

This complexity is amplified by the sensitive nature of the products themselves. The reverse supply chain requires specialized handling procedures to manage temperature-sensitive biologics, secure chain-of-custody for controlled substances, and compliant disposal of hazardous materials.36 Every step must be executed in accordance with Good Distribution Practices (GDP), a set of quality standards for the sourcing, storage, and transportation of medicines.36

Beyond logistical complexity, the reverse supply chain represents a critical point of vulnerability for the entire pharmaceutical ecosystem. It has been identified as a potential entry point for counterfeit, diverted, or otherwise illegitimate products to infiltrate the legitimate supply chain.37 The global market for counterfeit drugs is a staggering $200 billion problem, posing a grave risk to patient safety and causing significant financial and reputational damage to manufacturers.37 A lack of secure, serialized tracking within the returns process creates an opportunity for fraudulent actors to introduce fake medications, making robust security and verification protocols an absolute necessity.37

The Compliance Burden: Adhering to FDA, DEA, and Environmental Mandates

The management of pharmaceutical returns is governed by a dense and overlapping framework of regulations from multiple federal agencies. Navigating this compliance gauntlet is a non-negotiable aspect of the process, where failure can result in severe legal and financial penalties.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): The FDA’s Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations form the bedrock of returns management. Specifically, 21 CFR 211.204 mandates that companies must establish and follow written procedures for the holding, testing, and reprocessing of returned drug products. It also requires the maintenance of detailed records for every return, including the product name, lot number, reason for return, quantity, and final disposition.39 Perhaps the most financially significant regulation is 21 CFR 211.208, which explicitly states that drug products that have been subjected to improper storage conditions “shall not be salvaged and returned to the marketplace”.17 This regulation transforms a logistical failure, such as a temperature excursion in a warehouse, into a direct and often total financial loss.

- Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): A significant portion of returned pharmaceuticals consists of controlled substances or materials classified as hazardous waste. Reverse distributors must be licensed with the DEA to legally handle and document the destruction of Schedule II-V pharmaceuticals, ensuring these potent drugs do not re-enter the market illicitly.5 Similarly, compliance with EPA regulations is required for the proper disposal of hazardous pharmaceutical waste to prevent environmental contamination. Adherence to these regulations establishes a compliant “chain of liability,” protecting all parties in the supply chain from legal action.8

- Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA): The DSCSA introduces a further layer of complexity and a powerful tool for enhancing the security of the returns process. The act mandates an interoperable, electronic system to trace prescription drugs as they are distributed in the United States.40 For returns, this means that trading partners must be able to verify the unique product identifier on a returned saleable product before it can be reintroduced into the supply chain for resale. This serialization and verification requirement is a critical defense against the introduction of counterfeit or illegitimate products through the reverse channel.40

Accounting and Accountability: SOX Compliance and the Perils of Inadequate Return Reserves

The challenges of managing pharmaceutical returns extend deep into the realms of corporate finance, accounting, and legal accountability. The process is not merely operational; it is a matter of corporate governance with significant implications for a company’s financial reporting integrity and the personal liability of its senior executives.

At the heart of the issue are revenue recognition standards. Under frameworks like the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s (FASB) ASC 606, Revenue from Contracts with Customers, a company cannot simply book the full value of a sale and deal with returns later. The standard requires that at the time revenue is initially recognized, the company must estimate the amount of consideration that will be variable—including future product returns—and constrain the recognized revenue accordingly.21 This effectively means that a company must create a reserve or accrual for expected future returns. The accuracy of this reserve is therefore a prerequisite for compliant financial reporting.

This requirement gains significant legal weight under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). A key provision of SOX mandates that the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of a public company must personally certify the accuracy of their company’s financial statements and the effectiveness of their internal controls.42 This places the responsibility for the reasonableness of the returns reserve squarely on the shoulders of the C-suite.

The potential consequences of failure are severe, as demonstrated by the landmark enforcement action taken by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) against Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS). The SEC alleged that BMS engaged in a fraudulent scheme to inflate its sales and earnings, partly by “channel stuffing”—inducing its wholesalers to take on massive amounts of excess inventory beyond underlying patient demand. This practice was coupled with the material understatement of its accruals for customer rebates and, by extension, its reserves for the inevitable return of this excess product.42 The SEC’s action resulted in BMS agreeing to pay a

$150 million civil penalty and consenting to a permanent injunction against future violations.42

The BMS case serves as a stark warning. The intentional or negligent underestimation of return reserves is not treated as a simple forecasting error by regulators; it can be, and has been, prosecuted as securities fraud. The SOX certification process means that the CFO is legally attesting to the integrity of the financial statements, which includes the adequacy of the returns reserve. This transforms the company’s returns forecasting model from a mere planning tool into a critical component of its internal controls over financial reporting. A weak, poorly documented, or easily manipulated forecasting process can be identified by auditors as a significant material weakness, a major red flag for investors and a direct source of legal and financial risk for the company and its leadership.

The Patent Cliff Effect: Forecasting the Inevitable Returns Tsunami

Why Loss of Exclusivity (LoE) Triggers a Surge in Branded Drug Returns

Among the various drivers of pharmaceutical returns, none is as predictable in its occurrence yet as disruptive in its financial impact as the loss of market exclusivity (LoE) for a blockbuster branded drug. This event, colloquially known as the “patent cliff,” describes the precipitous and often dramatic decline in a company’s revenue when a key product’s patent protection expires, opening the floodgates to low-cost generic or biosimilar competition.43 The financial stakes are monumental; the pharmaceutical industry is projected to face over $200 billion in annual revenue risk from patent expiries through 2030.44 This event triggers a massive and sustained surge in product returns that can reverberate through a company’s financial statements for years.

The mechanism behind this returns tsunami is straightforward yet powerful. In the weeks and months leading up to a drug’s LoE, the entire pharmaceutical supply chain—from the manufacturer’s own distribution centers to wholesaler warehouses and the shelves of thousands of pharmacies—is stocked with the branded product to meet ongoing patient demand. However, the moment the first generic competitors launch, often at a significant discount, prescription patterns shift dramatically and rapidly. Payers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) aggressively steer patients toward the cheaper alternatives, causing demand for the branded product to plummet. A blockbuster drug can lose as much as 80% to 90% of its revenue within the first year of facing generic competition.44

This sudden collapse in demand leaves the channel holding millions of dollars’ worth of branded inventory that it can no longer sell in a timely manner. As this inventory ages and approaches its expiration date, it becomes eligible for return under the manufacturer’s returned goods policy.25 The result is a massive wave of returns that begins shortly after LoE and can continue for an extended period. While the normal return rate for a successful blockbuster drug is typically low, in the range of 1% to 2% of annual sales, this rate spikes significantly in the 18 to 48 months following LoE as the channel purges its now-unsaleable branded stock.25

Case Studies in Post-LoE Returns Management

The experiences of major pharmaceutical companies that have navigated the patent cliff provide invaluable lessons in the financial impact of LoE and the strategic responses required. Two of the most prominent examples are Pfizer’s Lipitor and the Sanofi/Bristol-Myers Squibb alliance’s Plavix.

- Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin): For years, Lipitor was the best-selling drug in the history of the pharmaceutical industry, a cholesterol-lowering medication that earned Pfizer over $125 billion in revenue during its 14 years of patent protection.49 Facing the loss of its U.S. patent in November 2011, Pfizer deployed a multi-pronged strategy to manage the inevitable revenue decline and the associated returns. To compete directly with the first generic entrant, Pfizer launched an aggressive rebate program called “Lipitor-For-You,” which offered privately insured patients a coupon card to purchase the branded drug for a copayment as low as $4 per month, significantly undercutting the typical generic copay.50 Simultaneously, Pfizer entered into an agreement with Watson Pharmaceuticals to launch an “authorized generic” version of Lipitor. This allowed Pfizer to capture a portion of the revenue from the generic market itself, as Watson marketed a chemically identical product under a different label.49 Finally, Pfizer explored a long-term strategy of seeking FDA approval to switch a low-dose version of Lipitor to over-the-counter (OTC) status, which would have granted it a new period of market exclusivity in the consumer health space.50

- Sanofi/BMS’s Plavix (clopidogrel): Plavix, an anti-platelet agent used to prevent heart attacks and strokes, was another massive blockbuster whose patent expiration had a profound market impact. When its primary patent expired, the market witnessed a rapid and aggressive entry of generic manufacturers. The availability of low-cost alternatives led to a swift erosion of the branded product’s market share. Market analyses indicate that generic versions of clopidogrel captured between 56% and 92% of all prescriptions within one to eight years following the patent expiry.51 This dramatic shift resulted in intense price competition, a substantial reduction in the overall cost of clopidogrel-based therapies, and a corresponding steep decline in revenues for the branded product.51

These cases highlight a critical point for forecasting: the post-LoE period is not a passive decline but an active battleground. The strategies a company employs to defend its brand—be it aggressive rebating, launching an authorized generic, or pursuing new formulations—directly influence the rate at which branded inventory is depleted from the channel and, consequently, the volume and timing of returns. An aggressive rebate program might sustain branded sales longer than historical analogs would suggest, delaying and potentially reducing the returns spike. Conversely, launching an authorized generic could accelerate the cannibalization of the branded product’s channel inventory, leading to an earlier and sharper returns peak. Therefore, any credible post-LoE returns forecast must be intrinsically linked to the company’s commercial strategy.

Strategic Inventory Management in the Face of Generic Competition

Given the certainty of a post-LoE returns surge, proactive management of channel inventory in the period leading up to and immediately following patent expiry is a critical financial lever. However, this is complicated by a significant challenge: a lack of visibility. While manufacturers typically have excellent, near-real-time visibility into the inventory levels held by their direct wholesale partners through Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) 852 feeds, the inventory held further downstream is often a “complete blind spot”.25 The stock held on the shelves of tens of thousands of independent pharmacies, within the distribution centers of large retail chains, and in hospital formularies is not systematically reported back to the manufacturer. This uncertainty about the true volume of product in the total channel is a primary driver of inaccurate post-LoE returns reserves.

To combat this, leading pharmaceutical companies are adopting more sophisticated, data-driven strategies to manage the LoE transition:

- Enhanced Data Collection and Analytics: Companies are moving beyond reliance on wholesaler data alone. By leveraging EDI 867 data, which reports product sales and transfers from wholesalers to specific downstream locations, manufacturers can begin to model inventory levels at major pharmacy chains and other large customers. This data can be supplemented with large-scale, targeted pharmacy surveys to build a more statistically robust picture of downstream inventory, reducing the margin of error in national estimates.25

- Proactive Channel Partnerships: Armed with better data, manufacturers can engage in strategic partnerships with their largest channel partners. This can involve collaborating with major retail chains to deliberately and systematically reduce their on-hand inventory in the months leading up to LoE, or negotiating agreements to allow for the early return of excess stock immediately following the generic launch to clear the channel more quickly.25

- Strategic Returns Policy Adjustments: Companies are also re-evaluating their returns policies to gain more transparency and control. This can include tightening policies to disallow the crediting of “bundled” returns from third-party processors where the origin of the product is unclear, giving finance and trade teams a clearer view of where inventory pockets exist.25

These strategies highlight a core dilemma that brand managers face as LoE approaches: a delicate trade-off between maximizing the final quarters of branded revenue and minimizing the massive future liability of product returns. Aggressively pushing product into the channel just before patent expiry can inflate short-term sales figures and meet quarterly targets, a practice known as channel stuffing.42 However, this strategy guarantees a massive and financially painful returns charge-back in subsequent periods. Conversely, throttling supply too aggressively in the run-up to LoE risks creating stock-outs, frustrating patients and physicians, and ceding market share to generic competitors even more rapidly than necessary. The only way to effectively navigate this critical, end-of-life financial balancing act is through an accurate and integrated forecast that models not only the lingering demand for the branded product but also the true level of inventory across the entire supply chain. The forecast thus becomes the central tool for optimizing this final, crucial phase of a blockbuster drug’s lifecycle.

The Forecaster’s Toolkit: From Statistical Models to Predictive Intelligence

Traditional Forecasting Models and Their Limitations

Historically, the forecasting of pharmaceutical sales and returns has relied on a toolkit of established statistical methods. These are primarily time-series models that analyze historical data to identify patterns and extrapolate them into the future. Common methods include:

- Naïve and Moving Average Models: The simplest approaches, where future forecasts are based on the most recent observation or an average of several recent periods.52

- Exponential Smoothing: A more sophisticated technique that applies exponentially decreasing weights to older observations, giving more significance to recent data.52

- ARIMA (Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average) Models: These models are workhorses of time-series forecasting, capable of capturing complex trend and seasonality patterns within the data. Variants like SARIMA (Seasonal ARIMA) are specifically designed to handle data with strong seasonal components, such as the predictable spikes in demand for flu vaccines or allergy medications.52

While these models can be effective for stable products in mature markets, they share a fundamental limitation: they are inherently backward-looking. They operate on the assumption that the underlying patterns of the past will continue into the future. In the dynamic and often volatile pharmaceutical market, this assumption is frequently violated. Traditional time-series models are ill-equipped to predict the impact of sudden, paradigm-shifting events such as the unexpected results of a competitor’s clinical trial, a sudden product recall, or, most notably, the market-shattering impact of a patent expiry. Their reliance on historical data alone makes them poor instruments for navigating the industry’s inherent uncertainty.

Building a Modern Forecasting Engine: Key Data Inputs and Methodologies

To overcome the limitations of traditional methods, a modern forecasting engine must adopt a more holistic, multi-factorial approach. Instead of relying solely on past returns data, a robust forecast is built from the ground up, integrating a wide array of disparate data sources to create a comprehensive model of the market. This “bottom-up” approach constructs a forecast based on the fundamental drivers of demand and returns, rather than simply extrapolating past trends.55

The key data inputs for such an engine include:

- Epidemiological Data: The foundation of any demand forecast is an understanding of the disease itself. This includes data on the incidence (number of new cases per year) and prevalence (total number of cases at a given time) of the target condition.55

- Market and Patient Data: This layer refines the total potential market into an addressable one. It includes data on the total population, the percentage of patients who are actually diagnosed, the percentage of those who receive treatment, and the current market penetration rates of all competing therapies.55

- Clinical Trial Data: The safety and efficacy profile of a drug, as determined through its Phase I-IV clinical trials, is a powerful predictor of its potential market adoption and positioning. Strong clinical outcomes can support premium pricing and rapid uptake, while a challenging side-effect profile may limit its use to specific patient subgroups.32

- Supply Chain Data: This provides a real-time view of the product’s physical journey. It includes inventory levels at wholesalers (from EDI 852 data), sales from wholesalers to downstream partners (from EDI 867 data), shipment volumes, and, crucially, historical returns data that has been meticulously categorized by reason code (e.g., expiration, damage, recall) to identify specific failure points.25

- Commercial and Pricing Data: The forecast must account for the company’s own commercial strategy and the broader reimbursement landscape. This includes the drug’s list price (WAC), the negotiated rebate rates with payers, its formulary status, and the impact of sales force detailing and marketing efforts.55

By integrating these diverse data streams, a company can build a dynamic model that is far more sensitive to shifts in the market than a simple time-series analysis. This approach acknowledges that returns are not an isolated phenomenon but the end result of a complex interplay of clinical, commercial, and logistical factors.

“Like many other industries, manufacturers of pharmaceutical products have historically created returned goods policies that offer credit for unsold products that meet specific criteria. These policies assist in sales efforts to distributors and retailers, particularly during the launch of new products. Addressing returned goods in the healthcare supply chain offers an opportunity for total system cost reductions… However, this also has led some to rely on the returns process rather than on more proactive inventory management efforts.”

— Understanding the Drivers of Expired Pharmaceutical Returns, Healthcare Distribution Management Association (now HDA), 2011. 18

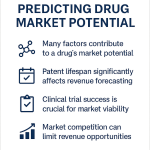

The Role of Competitive Intelligence: Leveraging Platforms like DrugPatentWatch

A truly robust forecast cannot be built in an internal vacuum. It must be informed by a keen understanding of the external competitive landscape and future market events. This is particularly true when forecasting for the single most disruptive event in a drug’s lifecycle: the loss of patent exclusivity. Predicting the timing and impact of generic entry is a critical input for any post-LoE returns model.

This is where specialized competitive intelligence platforms become indispensable tools for the forecasting team. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide critical, forward-looking business intelligence that serves as a direct input into sophisticated forecasting models. By consolidating and analyzing complex patent and regulatory data, these services allow a company to:

- Predict Patent Expiration Dates: Accurately identify the precise dates when key patents for both their own and competitors’ products are set to expire, providing a clear timeline for expected market shifts.57

- Identify Generic Competitors: Track which generic and biosimilar manufacturers have filed applications (like Abbreviated New Drug Applications, or ANDAs) with the FDA to market a competing version of a drug, signaling who the likely first entrants will be.57

- Monitor Patent Litigation: Follow the progress of patent litigation challenges (such as Paragraph IV challenges), as the outcome of these legal battles can significantly accelerate or delay the timeline for generic entry.57

- Inform Channel Partners: Provide wholesalers and distributors with clear, data-driven intelligence on upcoming patent expiries, enabling them to proactively manage their inventory and prevent the overstocking of branded drugs that are about to face generic competition.57

Integrating this type of external, forward-looking intelligence transforms a forecast from a reactive, statistical exercise into a proactive, strategic one. Knowing with a high degree of certainty when a blockbuster patent will expire and who is poised to launch a generic competitor allows a manufacturer to model the anticipated decline in its own sales and the corresponding spike in product returns with a level of precision that is simply unattainable through the analysis of historical data alone.

The Future of Returns Forecasting: AI, Machine Learning, and Strategic Optimization

Leveraging AI and ML to Predict Return Rates with Unprecedented Accuracy

The next frontier in pharmaceutical returns management lies in the application of advanced analytics, specifically Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). These technologies offer the potential to move beyond traditional forecasting models and develop predictive capabilities with a level of accuracy and granularity previously thought impossible. Predictive analytics is the practice of using vast amounts of data, sophisticated statistical algorithms, and ML techniques to identify the likelihood of future outcomes.58

When applied to the problem of product returns, AI and ML models can ingest and analyze massive, disparate datasets in real time. They can simultaneously process historical sales data, live supply chain inventory levels, patient-level prescription data, clinical trial outcomes, regulatory filings, and even unstructured external data like news reports or social media sentiment.37 By doing so, these models can uncover subtle, non-linear patterns and correlations that are invisible to human analysts and traditional statistical methods.

For example, an ML model might learn to identify that a specific combination of factors—a particular drug batch manufactured during a period of high humidity, shipped through a specific logistics corridor known for temperature fluctuations, and ordered in unusually large quantities by a pharmacy chain in a certain region—consistently leads to a higher-than-average rate of returns due to expiration 18 months later. Armed with this predictive insight, the manufacturer can take proactive steps, such as working with that pharmacy chain to rebalance its inventory or flagging that specific batch for closer monitoring, thereby preventing the future loss before it occurs. This represents a fundamental shift from reacting to returns to preempting them.

Building a Resilient Supply Chain: Using Predictive Analytics to Minimize Unsaleable Goods

The ultimate promise of predictive intelligence is not merely to forecast a financial loss with greater accuracy, but to provide the insights needed to prevent that loss from ever happening. By integrating AI and ML into the core of their supply chain and commercial operations, pharmaceutical companies can build a more resilient, efficient, and financially sound enterprise.

The applications extend across the returns lifecycle:

- Optimized Inventory and Demand Forecasting: AI-powered platforms can provide real-time demand forecasting that is far more dynamic and responsive to market signals than traditional models. This allows for intelligent inventory optimization across the entire supply chain, preventing the overstocking in specific channels that is a primary cause of expired product returns.60

- Enhanced Security and Fraud Detection: The reverse supply chain is a known vulnerability for counterfeit drug infiltration. AI-based fraud detection systems can analyze return patterns in real time to identify anomalies and suspicious activities, such as an unusually high volume of returns for a specific lot number from a non-traditional source, flagging it for investigation and preventing fraudulent products from entering the system.37

- Intelligent Process Automation: The manual processes involved in handling, sorting, and reconciling returns are labor-intensive and prone to error. AI, combined with robotics and computer vision, can automate many of these tasks, from scanning and verifying returned products to intelligently routing them for credit, reprocessing, or destruction. This not only increases operational efficiency and reduces administrative costs but also frees up human capital for more strategic, value-added activities.62

The true transformative potential of AI in this domain lies in its ability to act as an integrator of disparate and complex risks. The preceding analysis has identified a series of distinct risk categories: financial (GTN erosion), operational (logistical failures), regulatory (FDA compliance), and market (patent expiry). A human analyst, or even a traditional statistical model, struggles to effectively model how these different risks interact and compound one another. An AI-powered platform, however, can. It can simulate how a change in a major PBM’s formulary (a financial risk), combined with a prolonged heatwave affecting a key distribution corridor (an operational risk), might dramatically increase the probability of a specific product lot becoming unsaleable due to temperature excursions (a regulatory risk), just as that product is facing a patent cliff (a market risk). This capacity for integrated, multi-variable risk assessment is far beyond the scope of conventional methods. It allows a company to move from managing returns as a series of siloed, functional problems to optimizing it as a single, interconnected system, thereby unlocking immense financial and strategic value.

Strategic Recommendations for Financial and Supply Chain Executives

To harness the power of predictive intelligence and transform returns management from a cost center into a source of competitive advantage, senior leadership must champion a strategic shift in mindset, investment, and organizational structure. The following actions are recommended:

- Invest in a Unified Data Architecture: The foundation of any advanced forecasting capability is high-quality, accessible data. Companies must prioritize breaking down the data silos that traditionally separate finance, commercial operations, and the supply chain. Investing in a unified data platform or data lake is essential to create a “single source of truth” that can feed sophisticated analytical models.

- Embrace Predictive Technologies and Talent: The era of relying on spreadsheets for critical financial forecasting is over. Executives must champion investment in modern AI and ML platforms specifically designed for supply chain and revenue management. This technological investment must be paired with an investment in human capital, recruiting and developing the data science talent required to build, validate, and operate these advanced models.

- Redefine and Align Performance Metrics: Organizational incentives must be aligned with the new strategic goal. The performance of the supply chain and returns management teams should be measured not just on the efficiency with which they process returns, but on the measurable reduction in the volume and value of preventable returns.

- Foster Deep Cross-Functional Collaboration: Returns management is not solely a supply chain or finance problem; it is an enterprise-wide challenge. Companies should establish a dedicated, high-level GTN and returns management task force. This group should include senior representatives from finance, supply chain, market access, commercial operations, and legal affairs to ensure that returns are managed as a cohesive strategic issue, not a series of disconnected operational tasks.

Key Takeaways

- Pharmaceutical product returns are not a minor operational cost but a massive financial liability, representing a reverse flow of goods valued at over $13 billion annually, which directly erodes net revenue through Gross-to-Net (GTN) deductions.

- The failure to accurately forecast and reserve for product returns constitutes a significant financial and governance risk, impacting cash flow, the ability to fund R&D, and potentially leading to material financial restatements and regulatory scrutiny under the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act.

- The loss of patent exclusivity (the “patent cliff”) for a blockbuster drug is the single largest and most predictable catalyst for product returns, triggering a massive and sustained spike in returned inventory that requires dedicated, data-driven strategic forecasting to manage.

- Effective, modern forecasting must evolve beyond simplistic, backward-looking time-series analysis. It requires a sophisticated, bottom-up model that integrates diverse data streams, including clinical, commercial, real-time supply chain data, and forward-looking competitive intelligence from platforms like DrugPatentWatch.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning represent the future of returns management, offering the potential to transform the function from a reactive process to a proactive, strategic capability. These technologies enable not only more accurate forecasting but also the predictive optimization of inventory and the integrated analysis of complex risks, ultimately preventing financial losses before they occur.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What is the single biggest driver of pharmaceutical product returns?While multiple factors such as product damage and recalls contribute, the most significant and financially impactful driver is the loss of patent exclusivity (LoE) for a branded drug. This event triggers the launch of low-cost generic competitors, causing demand for the brand to plummet and leading to a massive, sustained spike in returns of unsold inventory from the entire supply chain.

- How do product returns directly impact a pharmaceutical company’s financial statements?Product returns are a primary deduction in the Gross-to-Net (GTN) revenue calculation. When a product is returned for credit, the gross revenue that was initially recognized for that sale must be reversed. This directly reduces the company’s reported net revenue and, consequently, its profitability. Inaccurate reserves for future returns can lead to material financial restatements, which can damage investor confidence and attract regulatory scrutiny.

- Why is it so difficult to accurately forecast returns?Forecasting is challenging due to several factors. A primary issue is the lack of visibility into “downstream” inventory held at thousands of pharmacies and hospitals. Additionally, forecasting must account for unpredictable patient demand, the sudden and dramatic impact of unforeseen events like product recalls, and complex market dynamics, especially the rapid and severe shift in demand that follows a generic launch.

- What is the role of the FDA in the returns process?The FDA sets and enforces strict Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) regulations for handling returned pharmaceutical products. A crucial aspect of this oversight is the mandate that any drug product subjected to improper storage conditions, such as a break in the cold chain (temperature excursions), cannot be salvaged and resold. This regulation makes supply chain integrity and monitoring a critical factor in preventing financial losses from unsaleable returns.

- How can Artificial Intelligence (AI) improve returns forecasting?AI and Machine Learning algorithms can analyze vast and diverse datasets—including sales figures, real-time inventory levels, clinical trial outcomes, and even external factors like weather patterns affecting logistics—to identify complex patterns that precede returns. This allows for more accurate and granular predictions than traditional models. More importantly, it enables a strategic shift from simply forecasting returns to proactively taking steps, such as rebalancing inventory or adjusting sales incentives, to prevent those returns from occurring in the first place.

References

- Pharma Logistics. (n.d.). A Step-by-Step Guide to the Pharmacy Drug Return Process. Retrieved from https://pharmalogistics.com/a-step-by-step-guide-to-the-pharmacy-drug-return-process/

- Wouters, O. J., et al. (2022). Biopharma company valuation and deal value in the drug development process. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0263326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263326

- Healthcare Distribution Management Association. (2011). Understanding the Drivers of Expired Pharmaceutical Returns. NACDS.

- AmerisourceBergen. (2020, August 14). Manage Your Margin: Recouping Your Losses on Unsaleable Pharmaceuticals.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025, January 21). Expiration Dates – Questions and Answers.

- Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. (n.d.). Returned Goods Policy. Retrieved from https://www.otsuka-us.com/returned-goods

- CMP Pharma, Inc. (n.d.). Return Goods Policy. Retrieved from https://cmppharma.com/legal/return-goods-policy/

- Chartwell Pharmaceuticals. (n.d.). Returned Goods Policy. Retrieved from https://chartwellpharma.com/returned-goods-policy/

- Inmar Intelligence. (n.d.). Understanding Market Actions: Returns, Recalls, and Corrections. Retrieved from https://www.inmar.com/blog/insights/healthcare/understanding-market-actions-returns-recalls-and-corrections

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Understanding Drug Recalls with Dr. Ileana Elder.

- Schlafender Hase. (n.d.). The ripple effect: Exploring the extensive costs associated with product recalls. Retrieved from https://www.schlafenderhase.com/shblog/the-ripple-effect-exploring-the-extensive-costs-associated-with-product-recalls

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025, January 21). Questions and Answers on Current Good Manufacturing Practice Requirements for Returned and Salvaged Drug Products.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). 21 CFR § 211.204 – Returned drug products. Code of Federal Regulations.

- Return Logistics International. (n.d.). Manufacturer of Pharmaceuticals or Personal Care Products. Retrieved from https://returnlogistics.com/who-we-serve/manufacturer-of-pharmaceuticals-or-personal-care-products/

- National Pharmaceutical Returns. (2022). Blog. Retrieved from https://www.npreturns.com/Blog/tabid/128/Category/4/Default.aspx

- American Associated Pharmacies. (n.d.). Optimize Medication Returns in the Pharmacy. Retrieved from https://www.rxaap.com/featured-article-return-solutions/

- NextPharma Logistics. (2025). Returns Management. Retrieved from https://nextpharma-logistics.com/en/solutions/pharma-support/returns-management/

- ClickPost. (2025, June 30). Returns Management Software for Healthcare & Pharma. Retrieved from https://www.clickpost.ai/returns-management-software/for-healthcare

- Pharmaceutical Returns Service. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved from https://pharmreturns.net/

- Roambee. (n.d.). The Ultimate Guide to Pharmaceutical Supply Chain. Retrieved from https://www.roambee.com/pharmaceutical-supply-chain-guide/

- JungleWorks. (2020, August 3). Reverse Logistics in Pharma Industry: Importance and Best Practices. Retrieved from https://jungleworks.com/reverse-logistics-in-pharma-industry/

- Congressional Budget Office. (2021, April). Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry.

- Clinical Trials Arena. (2025, May 29). The impact of drug pricing and reimbursement on the pharmaceutical industry.

- Deloitte. (2024). Deloitte Pharma Study: R&D returns are improving.

- iHealthcareAnalyst, Inc. (n.d.). Revenue Forecasting Techniques for New Pharmaceutical Drugs. Retrieved from https://www.ihealthcareanalyst.com/revenue-forecasting-new-pharma-drugs/

- Deloitte. (2024). Measuring the return from pharmaceutical innovation 2024.

- Clinical Leader. (n.d.). Digitalized Drug Forecasting Minimizes Waste in Clinical Trial Supply Chain.

- Deloitte. (2025, April 2). Deloitte’s 15th Annual Pharmaceutical Innovation Report: Pharma R&D returns continue upward for second consecutive year [Press release]. PR Newswire.

- PwC. (2024). Pharmaceutical industry trends 2025.

- PatSnap. (n.d.). When Does a Drug Patent Expire? Retrieved from https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/when-does-a-drug-patent-expire

- RAND Corporation. (2025, January 7). Typical Cost of Developing a New Drug Is Skewed by Few High-Cost Outliers [Press release].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2024, October 2). Drug Development.

- Precedence Research. (2025, June 16). Pharmaceutical Market Size to Hit USD 3.03 Trillion by 2034.

- Grand View Research. (2025, June 15). Pharmacy Market Size And Share | Industry Report, 2030.

- Clinical Trials Arena. (2025, May 29). The impact of drug pricing and reimbursement on the pharmaceutical industry.

- West Health Policy Center. (2019, November 13). How Much Can Pharma Lose?

- Fassoula, E. D. (2006). Reverse logistics as a means of reducing the cost of quality. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 17(5), 621-633.

- Dabeesing, D., et al. (2024). Reverse logistics capabilities and supply chain performance in a developing country context. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications.

- Reuters. (2025, July 29). AstraZeneca tops expectations on robust drug sales, US demand. PharmaLive.

- Mestre-Ferrandiz, J., et al. (2018). Projecting Pharmaceutical Expenditure in EU5 to 2021: Adjusting for the Impact of Discounts and Rebates. PharmacoEconomics, 36(12), 1475-1486.

- West Health Policy Center. (2019, November). How Much Can Pharma Lose?.

- Baker Tilly. (n.d.). The challenges of gross-to-net functions in life sciences.

- EisnerAmper. (2024, July 12). Gross-to-Net Revenue Accounting in Life Sciences.

- Magnolia Market Access. (2024, December 11). What Does Gross to Net (GTN) Mean for Drugs?

- Patra, S. (n.d.). Pharma-Sales-Analysis-and-Forecasting. GitHub. Retrieved from https://github.com/SaibalPatraDS/Pharma-Sales-Analysis-and-Forecasting

- iHealthcareAnalyst, Inc. (n.d.). Revenue Forecasting Techniques for New Pharmaceutical Drugs.

- MedeAnalytics. (2025, July 17). Partnership Uses Predictive Analytics to Address Medication Failure [Press release]. PR Newswire.

- nexocode. (2021, October 14). Predictive Analytics: A Revolutionary Tool for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing.

- Let’s Talk Supply Chain. (2025, March 7). Machine learning adoption into supply chain management on the horizon.

- RTS Labs. (2024, March 29). Optimizing Reverse Logistics: Pricing & Reselling Strategies.

- Owoade, A., et al. (2025). AI and Predictive Modeling for Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Optimization and Market Analysis. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology, 17(1).

- Parkview Health Research Repository. (2025). Forecasting the impact of artificial intelligence on clinical pharmacy practice.

- Bailey Walsh. (2025, May 9). The Impact of Patent Cliff on the Pharmaceutical Industry.

- Esko. (2025, May 1). The Patent Cliff: From Threat to Competitive Advantage.

- DrugPatentWatch. (n.d.). What Happens When a Drug Patent Expires? Understanding Drug Patent Life.

- Dylst, P., et al. (2018). The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: A Systematic Literature Review. PLoS ONE, 13(9), e0202505.

- McKesson. (n.d.). Pharmacy Returns for Prescription Drugs and OTC Health Products.

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025, July 23). How Clinical Trial Data Supports Accurate Pharma Forecasting.

- Crozdesk. (n.d.). DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives.

- The Logistics of Logistics. (2025, July 26). Overcoming Pharma & Healthcare Supply Chain Challenges with Michael Needham [Video]. YouTube.

- Pharmaceutical Commerce. (2025, January 29). Challenges Facing Pharma Supply Chains.

- NetSuite. (n.d.). A Guide to Reverse Logistics: How It Works, Types and Strategies.

- Internal Revenue Service. (n.d.). Annual Fee on Branded Prescription Drug Manufacturers and Importers.

- Deloitte. (2024). Measuring the return from pharmaceutical innovation 2024.

- Import Globals. (2024). Pharmaceutical Exports of the United States: Unlock the Key Insights of the Latest Shipments Details of 2024.

- Fortune Business Insights. (2024). North America Pharmaceuticals Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis.

- Fortune Business Insights. (2024). Pharmaceuticals Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis.

- InsightAce Analytic. (2024). Pharma 5.0 Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report.

- IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. (2025). Reports and Publications.

- IQVIA. (2025, January). Biopharma M&A: Outlook for 2025.

- IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. (2021). Global Medicine Spending and Usage Trends: Outlook to 2025.

- Gartner. (2024). The Gartner Healthcare Supply Chain Top 25 for 2024.

- Manhattan Associates. (n.d.). Reverse Logistics: The Ultimate Guide.

- Supply Chain Management Review. (2019, October 15). Gartner Identifies 5 Actions to Optimize Logistics Costs From Within the Organization.

- Recall InfoLink. (n.d.). What’s the True Cost of a Recall?

- Marsh. (2018, August). Life Sciences Risk Study.

- BD. (n.d.). Expired Medications, What’s the Cost?

- Al-Shareef, H., & Al-Ghamdi, M. (2022). The Dilemma of Expired Drugs: An Overview on the Controversial Issue. JMA Journal, 5(4), 369-373.

- Ali, A., et al. (2023). Modeling Criteria for Product Return in a Pharmaceutical Company. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Production Research, 34(3), 361-375.

- Pundziene, D., et al. (2022). Forecasting Model for Drug Supply Chain. Transformations in Business & Economics, 21(2), 143-161.

- XiltriX. (n.d.). Predictive Analytics for Life Science Facility and Operations Management.

- Maguluri, K. K., & Ganti, V. K. A. T. (2019). Predictive Analytics in Biologics: Improving Production Outcomes Using Big Data. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data, 2(2), 1-14.

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025, July 23). How Clinical Trial Data Supports Accurate Pharma Forecasting.

- Zdravkovic, M. (n.d.). Pharma Sales Data Analysis and Forecasting. Kaggle.

- Zhang, Y., & Fodinger, M. (2016). Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor. Journal of Strategy and Management, 9(2), 256-274.

- Zhang, Y., & Fodinger, M. (2016). Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a case study of Lipitor. Journal of Strategy and Management, 9(2), 256-274.

- PatSnap. (n.d.). When Does the Patent for Clopidogrel Expire?

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025, February 13). The Impact of Patent Expiry on Drug Prices: A Systematic Literature Review.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding the Global Public Health Implications of Substandard, Falsified, and Counterfeit Medical Products. (2013). Countering the Problem of Falsified and Substandard Drugs. National Academies Press (US).

- Pharmaceutical Commerce. (2011, April 8). Forecasting Returns When Patents Expire.

- Breakaway Technologies. (2025, March). 5 Critical Gross-to-Net Challenges Facing Pharmaceutical Revenue.

- Sidley Austin LLP. (2008, October). Charting a Course: Revenue Recognition Practices in the Current Enforcement Environment.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2014). ASU 2014-09, Revenue from Contracts with Customers (Topic 606).

- Investing.com. (2025, July 27). Earnings call transcript: Botanix Pharma Q4 2025 sees strong sales growth.

- Withum. (2021, June 8). Revenue Recognition for Pharmaceutical Companies: Gross to Net and ASC 606.

- IntegriChain. (2023, March 6). 5 Pharma Gross-to-Net Questions You Should Be Asking.

- Informa Connect. (2025). Pharma & Biotech Gross-To-Net Summit 2025.

- Pharmaceutical Commerce. (2024, December 5). Going Inside the Gross-to-Net Bubble and Its Nuances.

- SlideShare. (n.d.). Keyrus Gross-to-Net.

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Friedman doctrine.

- Nasdaq. (2025, July 29). After a 700% Rally Over the Last 3 Years, This Magnificent Artificial Intelligence (AI) Stock Looks Poised For Even More Monster Gains.

- McKinsey & Company. (2024, April 15). Increasing your return on talent: The moves and metrics that matter.

- The Commonwealth Fund. (2025, March). What Pharmacy Benefit Managers Do, and How They Contribute to Drug Spending.

- Institute for New Economic Thinking. (2022, December 6). Sick with “Shareholder Value”: US Pharma’s Financialized Business Model During the Pandemic.

- Federal Trade Commission. (2024, July). FTC Releases Interim Staff Report on Prescription Drug Middlemen.

- Morningstar. (2025, July 29). Vizient Projects Continued Cost Pressures Across the Healthcare Supply Chain in 2026.

- Raymond James. (2025). Pharma Services Insights.

- Healthcare Dive. (2025, February 3). Healthcare supply chain, pharmacy costs to rise in 2025: report.

- AmerisourceBergen. (2023, January). J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference [Presentation].

- SlideTeam. (2025). Top 10 Pharmaceutical Supply Chain PowerPoint Presentation Templates in 2025.

- BrightSpring Health Services. (2025, March 6). Fourth Quarter 2024 Earnings Presentation.

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (n.d.). HDA Research Foundation.

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (2025, June 24). Pharmaceutical Traceability (DSCSA).

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (n.d.). Home.

- HDA Research Foundation. (2018). The Role of Reverse Distribution.

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (2023, October 12). HDA Factbook: Rx Sales Through Traditional Healthcare Distributors Increase.

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (2024). 95th Edition HDA Factbook (2024–2025).

- Ecofin Agency. (2025, July 23). Toxic Russian Fuels Flood Africa, Aliko Dangote Warns of Health Crisis.

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (n.d.). HDA Publications – Role of Reverse Distribution.

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (2007). HDA Guidelines for Trading Partners on Downstream Product Actions.

- Chain Drug Review. (2018, August 13). Report takes close look at reverse distribution.

- Healthcare Distribution Alliance. (2022, April). Exceptions Handling Guidelines for the DSCSA.

- DrugPatentWatch. (2025, May 25). The Hidden Costs of Pharma Procurement—And How to Cut Them.

- AmerisourceBergen. (2020, August 14). Manage Your Margin: Recouping Your Losses on Unsaleable Pharmaceuticals.

- Purolator International, Inc. (2016). From “Free” Shipping to Product Returns: Understanding Hidden Costs in Your Supply Chain.

- Tive. (n.d.). Pharma Companies Cut Supply Chain Costs With IoT.

- National Association of Chain Drug Stores. (2011). Understanding the Drivers of Expired Pharmaceutical Returns.

- McKesson. (2025, June 24). Four Ways to Improve Your Unsaleable Returns Process.