The Foundation of Market Exclusivity: A Legal and Regulatory Primer

The duration of a drug’s market monopoly in the United States is not determined by a single patent but by a complex, overlapping patchwork of patents granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and various statutory exclusivities administered by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This legal architecture, designed to balance competing interests, has inadvertently created a set of levers that can be systematically manipulated to prolong market protection far beyond the baseline 20-year patent term.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Delicate Balance

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, fundamentally reshaped the pharmaceutical landscape.7 It established the modern generic drug industry by creating a streamlined approval pathway while simultaneously offering new protections to innovator companies.9 Before its passage, generic manufacturers were required to conduct their own costly and duplicative clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy.7 The Act’s dual goals were to facilitate generic competition and to compensate innovators for patent time lost during the lengthy FDA regulatory review process.9

The Act introduced the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, which allows a generic manufacturer to gain FDA approval by demonstrating that its product is bioequivalent to the branded drug, relying on the innovator’s original safety and efficacy data.7 This dramatically lowered the barrier to entry for generics. Today, generic drugs account for over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., a direct legacy of the Act.7

However, to secure support from innovator companies, the Act included several key provisions that have since become central to monopoly extension strategies:

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): This provision allows a brand-name drug manufacturer to apply for an extension of its patent term to compensate for a portion of the time consumed by the FDA’s pre-market regulatory review.9 This ensures that the effective patent life is not unduly eroded by regulatory delays.

- 30-Month Stay of Approval: When an ANDA filer challenges a brand’s patent (a “Paragraph IV certification”), the brand-name company can sue for patent infringement. The filing of this lawsuit automatically triggers a 30-month stay, or pause, on the FDA’s ability to grant final approval to the generic drug.10 While intended to provide time to resolve the patent dispute in court, this mechanism has evolved into a powerful tool for innovators to impose an automatic, guaranteed delay on competition, regardless of the underlying patent’s strength.12

- 180-Day Generic Exclusivity: To incentivize generic companies to undertake the risk and expense of challenging patents, the Act grants a 180-day period of market exclusivity to the “first-to-file” generic applicant.9 This can be a lucrative prize, but it has also become a focal point in controversial “pay-for-delay” settlements, where the brand company pays the first-to-file generic to delay its launch, thereby also blocking any subsequent generics from entering the market.6

FDA-Granted Exclusivity: The Statutory Safeguards

Separate and distinct from patents, the FDA grants several types of market exclusivity that provide additional layers of protection. These exclusivities, which run concurrently with any existing patents, prevent the FDA from approving a competing generic or biosimilar application for a specified period.13 The primary forms include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A drug containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA is granted five years of market exclusivity from the date of its approval.13 During this time, the FDA cannot accept an ANDA application from a generic manufacturer for the first four years (unless it contains a Paragraph IV patent challenge).

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): To encourage the development of treatments for rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.), the Orphan Drug Act provides seven years of market exclusivity for a drug approved for an orphan indication.13 This powerful incentive can be strategically applied to blockbuster drugs by seeking approval for a new, narrow rare disease indication, as seen with Crestor.14

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): This is one of the most widely used and effective extension tactics. If a manufacturer conducts pediatric studies as requested by the FDA, it is rewarded with a six-month extension of exclusivity. Crucially, this six-month period is added to all existing patents and exclusivities held by the sponsor for that drug’s active moiety.13 A six-month extension on a multibillion-dollar drug can be worth billions in additional revenue, making it a highly valuable prize for a relatively modest investment in pediatric trials.

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: This provides three years of exclusivity for a new drug application or supplement that contains reports of new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) essential to the approval.13 This is often granted for new indications or other significant changes to an already-approved drug.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA): A New Frontier of Exclusivity

The approval pathway for biologics—large, complex molecules derived from living organisms, such as monoclonal antibodies—is governed by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009. This legislation was intended to create a pathway for “biosimilars,” which are the biologic equivalent of generic drugs.16 Recognizing the immense cost and complexity of developing biologics, the BPCIA provides innovators with a significantly longer period of statutory protection than small-molecule drugs.18

The cornerstone of the BPCIA is a 12-year period of data exclusivity for new biologics, starting from the date of FDA approval.18 During this time, the FDA cannot approve a biosimilar application based on the innovator’s data. This establishes a much more formidable baseline of monopoly protection, meaning that any patents extending beyond this 12-year period become the new battleground. This long runway gives innovator companies ample time to construct elaborate patent defense strategies, effectively making 12 years a minimum, not a maximum, period of market exclusivity. The average market exclusivity period for top-selling drugs has been shown to be around 14.5 years, and the increasing prevalence of biologics is expected to lengthen this average further.19

International Context: Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs)

As a point of comparison, the European Union and other European countries utilize a different mechanism known as a Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC). An SPC is not a patent extension but a separate sui generis IP right that comes into force after the basic patent expires.22 Its purpose is to compensate the patent holder for the effective loss of patent life that occurs during the mandatory, lengthy process of clinical trials and regulatory approval.22

The term of an SPC is calculated based on the period between the patent filing date and the date of the first marketing authorization, but it cannot exceed a maximum of five years.22 A further six-month extension is available if the product has undergone pediatric testing in accordance with an approved Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP), making the maximum possible extension 5.5 years.23 This system provides a more structured and capped period of compensation compared to the more open-ended and strategically malleable combination of mechanisms available in the U.S.

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of U.S. Market Exclusivity for Pharmaceuticals

| Mechanism | Governing Authority | Standard Duration | Key Features & Notes |

| Patent | U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) | 20 years from filing date | Protects an invention (e.g., compound, formulation, method of use). Term can be extended via PTE. Multiple patents can create a “patent thicket.” |

| Patent Term Extension (PTE) | USPTO / FDA | Up to 5 years | Compensates for patent time lost during the FDA’s regulatory review process. A key provision of the Hatch-Waxman Act.10 |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity | FDA | 5 years | For drugs containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA. Prevents generic application submission for 4 years.13 |

| Biologic Exclusivity | FDA | 12 years | Granted to new biologic products under the BPCIA. Prevents FDA approval of a biosimilar for 12 years from the innovator’s approval date.18 |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) | FDA | 7 years | For drugs that treat a rare disease or condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S..13 |

| Pediatric Exclusivity (PED) | FDA | 6 months | Added to all existing patents and exclusivities for an active moiety as a reward for conducting requested pediatric studies.13 |

| New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity | FDA | 3 years | For applications with new clinical studies essential for approval, such as for a new indication or formulation of an existing drug.13 |

| 30-Month Stay of Approval | FDA | Up to 30 months | An automatic pause on generic approval triggered when an innovator files a patent infringement suit in response to a Paragraph IV challenge.10 |

The Art of Extension: Anatomy of Pharmaceutical Patent Evergreening

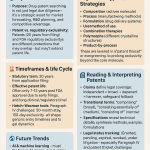

The strategic prolongation of a drug’s monopoly, a practice known as “evergreening,” is not a single act but a sophisticated, multi-pronged corporate strategy often referred to as “life-cycle management”.5 It is a planned process that begins years before a drug’s primary patent is set to expire, involving the coordinated efforts of a company’s legal, R&D, and marketing departments. The goal is to create a series of overlapping IP barriers that delay or deter generic and biosimilar competition, thereby preserving a blockbuster revenue stream. This is achieved through a toolkit of legal and commercial tactics designed to exploit the intricacies of the patent and regulatory systems.

The Patent Thicket: Building an Impenetrable Fortress

At the core of many modern evergreening strategies is the “patent thicket.” This involves creating a dense, overlapping web of dozens or even hundreds of patents around a single drug product.3 While the initial patent may cover the core active ingredient, subsequent patents are filed on every conceivable incremental modification: different salt forms, crystalline structures (polymorphs), formulations, dosages, manufacturing methods, and new medical uses.25

The primary purpose of a patent thicket is not necessarily to protect a series of genuine, breakthrough inventions, but to create a prohibitive legal barrier for potential competitors.27 The sheer volume of patents creates a chilling effect. A generic or biosimilar manufacturer wishing to enter the market must navigate this legal minefield. The cost of litigating dozens of patents simultaneously is exorbitant, and the risk is immense.28 To successfully launch its product, the challenger must invalidate or prove non-infringement for every single patent asserted against it—a task akin to “batting one thousand” in baseball. The innovator company, in contrast, needs only one patent to be upheld in court to block competition, or at the very least, secure a favorable settlement.28 This asymmetry of risk heavily favors the patent holder and can deter challenges altogether, even when many of the patents in the thicket are weak or of questionable validity.

Secondary Patenting: The Toolkit of Incrementalism

Secondary patents are the building blocks of a patent thicket. They are patents filed after the original compound patent and cover incremental changes that may or may not offer significant therapeutic advantages over the original product. Studies have shown that the vast majority of new drug patents—as high as 78%—are for existing drugs rather than new ones, highlighting the prevalence of this strategy.6 Key tactics include:

- New Formulations: A common strategy is to develop a new formulation of an existing drug and patent it. This frequently involves changing an immediate-release drug to an extended-release (ER) or controlled-release (CR) version. While this may offer the convenience of less frequent dosing, the active ingredient and its primary clinical effect remain unchanged.25 A prime example is Purdue Pharma’s development of an extended-release version of oxycodone, which extended its patent protection for OxyContin.25

- New Delivery Systems: Instead of changing the drug itself, companies can patent the device used to administer it. This is particularly effective for injectable drugs. Sanofi, for instance, extended the monopoly for its insulin product Lantus by obtaining patents on its SoloSTAR disposable injector pen and listing them in the FDA’s Orange Book.31 This forces a competitor not only to create a biosimilar insulin but also to design a new, non-infringing delivery device, adding significant cost and complexity.

- New Methods of Use/Indications: A company can obtain a new patent by discovering and proving that an existing drug is effective for treating a different disease or a new patient population. Pfizer successfully employed this strategy for Lyrica (pregabalin), which was first approved for epilepsy and later patented for the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Similarly, Viagra’s (sildenafil) market life was extended via a new patent for its use in treating pulmonary arterial hypertension after its blockbuster patent for erectile dysfunction expired.3

- Chiral Switching and Isomers: Many drugs are synthesized as a mixture of two stereoisomers (enantiomers), which are mirror images of each other. Often, only one of these isomers is therapeutically active. A “chiral switch” involves isolating the single active isomer from a previously patented racemic (50/50) mixture and patenting it as a new drug. AstraZeneca’s Nexium (esomeprazole) is the archetypal example. It is the S-isomer of omeprazole, the active ingredient in AstraZeneca’s earlier blockbuster, Prilosec. By launching Nexium as a “new, improved” product just as Prilosec’s patent expired, AstraZeneca effectively extended its monopoly on the world’s most popular acid reflux treatment.34

- Manufacturing Processes: For biologics, which are complex proteins produced in living cells, the manufacturing process is incredibly specific and difficult to replicate. This creates a fertile ground for patenting. The exact cell lines, purification methods, and production conditions can all be protected by patents and trade secrets.17 This “process is the product” reality means that a biosimilar manufacturer faces the dual challenge of replicating the final molecule and navigating a web of patents protecting how it is made, a significantly higher barrier than for small-molecule generics. Amgen’s long-running monopoly on Enbrel is heavily dependent on patents covering its complex manufacturing process.26

Strategic Litigation and Settlements

Litigation is not just a defensive measure; it is a proactive offensive strategy in pharmaceutical life-cycle management. As previously noted, filing a patent infringement lawsuit against a generic challenger automatically triggers a 30-month stay on FDA approval, providing a guaranteed period of continued monopoly.11

Furthermore, the threat of protracted and costly litigation often leads to settlements. In some cases, these settlements are pro-competitive, allowing a generic to enter the market years before the final patent in a thicket would have expired.28 The orchestrated 2023 entry of Humira biosimilars is a key example of this, where AbbVie traded years of potential monopoly for a certain and predictable market entry date for its competitors.38

However, some settlements, known as “pay-for-delay” or reverse payment agreements, are highly controversial. In these arrangements, the brand-name manufacturer pays the generic challenger to delay its market entry.6 Because the first generic filer holds a 180-day exclusivity period, delaying its entry also blocks all other generics from the market. These agreements have come under intense scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as being anticompetitive.

Titans of Longevity: In-Depth Analysis of the 10 Longest-Running Drug Patents

The strategic application of the legal and commercial tactics outlined above has allowed a select group of blockbuster drugs to achieve extraordinary periods of market exclusivity, generating unprecedented revenues. The following case studies examine the ten most prominent examples, dissecting the specific strategies that led to their prolonged monopolies.

Table 2: The Top 10 Longest-Running Drug Patents: A Comparative Overview

| Drug (Brand/Generic Name) | Manufacturer | Primary Indication | Peak Annual Sales (USD) | Original Patent Expiration | Final/Projected Exclusivity End | Total Monopoly Duration | Key Extension Strategies Employed |

| Humira (adalimumab) | AbbVie | Autoimmune Diseases | >$21 Billion 39 | 2016 3 | 2034 38 | ~39 years 5 | Patent Thicket (>247 apps), Strategic Settlements |

| Enbrel (etanercept) | Amgen | Autoimmune Diseases | ~$8 Billion 26 | 2012 3 | 2029 3 | ~30 years 40 | Foundational Fusion Protein & Manufacturing Patents |

| OxyContin (oxycodone) | Purdue Pharma | Pain | Not Available | 2013 3 | 2030 3 | ~17 years | Abuse-Deterrent Formulation (Product Hopping), FDA Petition |

| Revlimid (lenalidomide) | Celgene / BMS | Multiple Myeloma | ~$12.9 Billion 41 | 2019 3 | 2027 3 | ~8 years (managed decline) | Strategic Settlements, Secondary Patents, REMS |

| Lantus (insulin glargine) | Sanofi | Diabetes | >$7 Billion (€6.39B) 42 | 2015 3 | 2028 3 | ~13 years | Delivery Device Patents (Injector Pen) |

| Lyrica (pregabalin) | Pfizer | Neuropathic Pain | ~$5 Billion 43 | 2010 (US) 3 | 2018 (US) 3 | ~8 years | New Method of Use Patent (Pain Indication) |

| Lipitor (atorvastatin) | Pfizer | High Cholesterol | ~$13 Billion 44 | 2011 3 | 2012 (US) | ~1 year | Patent Term Extension, Pediatric Exclusivity |

| Crestor (rosuvastatin) | AstraZeneca | High Cholesterol | ~$5.8 Billion 45 | 2016 3 | 2023 3 | ~7 years | Orphan Drug Exclusivity, Pediatric Exclusivity |

| Viagra (sildenafil) | Pfizer | Erectile Dysfunction | ~$1.9 Billion 46 | 2012 (main patent) 3 | 2020 (PAH use) 3 | ~8 years | New Method of Use Patent (PAH Indication) |

| Nexium (esomeprazole) | AstraZeneca | Acid Reflux | >$2.6 Billion (Medicare) 35 | 2014 3 | 2018 (US) 3 | ~4 years | Chiral Switch (Isomer Patent), Formulation Patents |

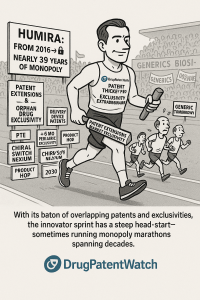

Case Study 1: Humira (adalimumab) – The Thicket Masterclass

Profile: Developed by AbbVie, Humira (adalimumab) is a monoclonal antibody used to treat a wide range of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease. For years, it reigned as the world’s best-selling pharmaceutical product, with peak annual sales surpassing $21 billion.3

Timeline: Humira’s primary patent on its active ingredient was set to expire in 2016. However, through an unprecedented and aggressive patenting strategy, AbbVie delayed the entry of biosimilar competitors in the lucrative U.S. market until January 2023. Some of its patents extend protection as far as 2034, giving the drug a potential monopoly lifespan of nearly 39 years from its first patent filings.3

Strategy Analysis: Humira is the archetypal example of a “patent thicket.” An investigation by the Initiative for Medicines, Access, & Knowledge (I-MAK) found that AbbVie had filed a staggering 247 patent applications on Humira in the U.S. alone. This is more than three times the number filed at the European Patent Office, where biosimilars launched in 2018—five years earlier than in the U.S..5 Critically, 89% of these patent applications were filed

after the FDA first approved Humira in 2002, and nearly half were filed after 2014, more than two decades after the initial research began.5 These secondary patents did not cover new breakthrough discoveries but rather incremental variations related to the drug’s formulation, manufacturing process, and methods of treatment.3 This dense web of IP was designed to make a legal challenge economically unviable for any single competitor. Generic drugmaker Boehringer Ingelheim attempted to fight AbbVie’s thicket in court, arguing it was an anticompetitive abuse of the patent system, but ultimately abandoned the effort and agreed to a settlement.38

Competitive Impact: Rather than risk unpredictable litigation outcomes across its vast patent estate, AbbVie employed a masterful settlement strategy. It entered into licensing agreements with at least eight different biosimilar manufacturers, including Amgen, Sandoz, and Pfizer.38 These settlements created an orderly, staggered schedule for biosimilar launches throughout 2023. This allowed AbbVie to trade a decade of potential future monopoly for a certain, managed decline, preventing a chaotic “patent cliff” and maximizing revenue in the final years of its exclusivity. The entry of biosimilars is projected to save the U.S. healthcare system billions of dollars, but their adoption rate is heavily influenced by the complex dynamics of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and payer formularies, which can sometimes favor the higher-priced, high-rebate brand-name product.16

Case Study 2: Enbrel (etanercept) – The 30-Year Fortress

Profile: Marketed by Amgen in the U.S., Enbrel (etanercept) is a fusion protein used to treat autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. It has been a cornerstone of Amgen’s portfolio for decades, with peak annual sales approaching $8 billion.26

Timeline: Enbrel’s primary patent, filed in 1990, expired in the early 2010s.3 However, Amgen secured two powerful, late-issued patents that extended its U.S. market exclusivity all the way to 2029.3 This gives Enbrel a potential 30-year monopoly from its first FDA approval in 1998, a remarkable duration.40

Strategy Analysis: Enbrel’s longevity strategy differs from Humira’s. Instead of a “death by a thousand cuts” thicket of numerous minor patents, Amgen’s defense rests on a fortress built around two foundational patents: U.S. Patent No. 8,063,182, which covers the etanercept fusion protein itself, and U.S. Patent No. 8,163,522, which covers a method of producing it.40 These patents were granted in 2011 and 2012, respectively, long after the drug was on the market. They were based on patent applications filed in the mid-1990s that had been kept alive through a series of continuations.

Competitive Impact: This strategy has proven incredibly effective at warding off competition. Sandoz, a division of Novartis, received FDA approval for its Enbrel biosimilar, Erelzi, in August 2016.50 However, Amgen’s litigation successfully blocked its launch. Sandoz challenged the validity of Amgen’s two key patents, but the courts upheld them, and in 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Sandoz’s appeal.48 As a result, Erelzi and another approved biosimilar, Samsung Bioepis’s Eticovo, are barred from the U.S. market until 2029.50 This delay comes at a significant cost; it is estimated that an etanercept biosimilar could have saved the U.S. healthcare system around $1 billion per year.51 The Enbrel case demonstrates that a few strategically timed, powerful patents can be just as effective, if not more so, than a large patent thicket.

Case Study 3: Revlimid (lenalidomide) – The Power of Settlements and Strategy

Profile: Revlimid (lenalidomide), originally from Celgene and now owned by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), is an oral medication for multiple myeloma and other cancers. It has been one of the most commercially successful drugs in history, with total lifetime sales exceeding $100 billion.3

Timeline: The original patent on Revlimid was set to expire in 2019. Through a series of patent extensions and strategic settlements, BMS has managed to protect the drug from full generic competition until 2027, with limited, volume-controlled generic entry beginning in March 2022.3

Strategy Analysis: Revlimid’s life extension strategy is a masterclass in combining secondary patenting with shrewd legal and commercial agreements. Celgene/BMS built a portfolio of patents covering not just the compound but also its methods of use and, crucially, its distribution system.41 Revlimid is subject to a strict Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program due to the risk of severe birth defects, which adds a layer of complexity for generic manufacturers seeking to replicate its distribution. The core of the strategy, however, was a series of carefully negotiated settlements with generic drugmakers like Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories and Cipla. These agreements permitted the generic companies to launch, but only with a limited volume of product in the initial years, with the allowed volume gradually increasing until full generic entry is permitted in 2026-2027.3

Competitive Impact: This “managed entry” approach has successfully blunted the financial impact of the patent cliff. Instead of a sudden, sharp drop in revenue, BMS is experiencing a controlled, predictable decline. The brand retains significant market share and pricing power, as the limited supply of generics cannot meet the full market demand.41 This strategy demonstrates how settlements can be used not only to resolve litigation but also to shape the competitive landscape for years after initial patent expiry, maximizing revenue for the innovator long after the primary monopoly has ended.

Case Study 4: OxyContin (oxycodone) – The Abuse-Deterrent Gambit

Profile: OxyContin (oxycodone), developed by Purdue Pharma, is a powerful, extended-release opioid analgesic. Its role in fueling the U.S. opioid epidemic has made it one of the most controversial drugs in modern history, leading to massive litigation and Purdue’s bankruptcy.54

Timeline: The patent on the original formulation of OxyContin expired in 2013. However, Purdue was able to extend its monopoly with a new formulation, with patents running until 2030.3

Strategy Analysis: Purdue’s strategy is a textbook example of “product hopping,” an evergreening tactic where a company makes a minor modification to a product and switches the market to the new version just as the original’s patent is about to expire.6 As the 2013 patent cliff approached, Purdue developed and patented a new abuse-deterrent formulation (ADF) of OxyContin, known as OxyContin OP, which was designed to be more difficult to crush, snort, or inject.25 Purdue then took a crucial step: it successfully petitioned the FDA to determine that the original, easily abused formulation of OxyContin was withdrawn from the market for reasons of safety and effectiveness. Based on this, the FDA announced it would not approve any generic applications that referenced the original formulation.55

Competitive Impact: The FDA’s decision was a monumental victory for Purdue. It effectively blocked the entire pipeline of generic competitors who had developed versions of the original OxyContin. To enter the market, a generic manufacturer would now have to not only copy the drug but also develop its own novel, FDA-approved abuse-deterrent technology—a far higher, more expensive, and time-consuming barrier.55 This move single-handedly extended Purdue’s lucrative monopoly for many years, demonstrating how regulatory processes can be leveraged in concert with patent strategy to forestall competition.

Case Study 5: Lantus (insulin glargine) – The Device is the Drug

Profile: Lantus (insulin glargine), from Sanofi, is a long-acting basal insulin used for the management of diabetes. For years, it was Sanofi’s flagship product and a dominant force in the global diabetes market, with sales peaking at over €6.39 billion ($7.19 billion) in 2015.42

Timeline: The primary patent on the insulin glargine molecule expired in 2015. However, Sanofi extended its market protection through patents on its delivery devices and certain formulations, with some patents listed as expiring as late as 2028.3

Strategy Analysis: Sanofi’s primary evergreening strategy for Lantus focused on patenting the delivery device rather than the drug itself. The company developed and patented the Lantus SoloSTAR, a disposable pre-filled injector pen that offered greater convenience and ease of use compared to traditional vials and syringes.31 Sanofi then listed several of these device patents in the FDA’s Orange Book alongside the drug patents. This tactic is controversial because the Orange Book is intended for patents that claim the drug substance or a method of using the drug. In 2020, a U.S. Court of Appeals found that Sanofi had improperly listed a key SoloSTAR patent because it claimed a drive mechanism in the pen, not the insulin glargine itself.32

Competitive Impact: Despite the eventual legal rebuke, the strategy was commercially successful for a significant period. It created additional hurdles for biosimilar developers, who had to design their own non-infringing injector pens, adding to their development costs and timelines. Even after the launch of biosimilar and interchangeable versions of insulin glargine, such as Semglee, the market uptake has been slower than expected. This is due in large part to the complex dynamics of the U.S. payer system, where PBMs may favor the higher-priced brand-name product due to the substantial rebates they receive from the manufacturer, a barrier to competition that exists even after patents have fallen.56

Case Study 6: Lyrica (pregabalin) – The Second-Act Patent

Profile: Lyrica (pregabalin) is a blockbuster drug from Pfizer used to treat neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and certain types of seizures. At its peak, it was a $5 billion-per-year product for the company.43

Timeline: The original U.S. patent on the pregabalin compound expired around 2010. However, Pfizer had obtained a secondary patent covering the method of using pregabalin to treat pain, which extended its monopoly in the U.S. until 2018.3 In the UK, the epilepsy patent expired in 2013, while the pain patent was valid until 2017.2

Strategy Analysis: Lyrica is a classic case of extending a drug’s life through a “new medical use” patent. After initially developing pregabalin for epilepsy, Pfizer conducted further studies and secured a separate, later-expiring patent for its use in treating neuropathic pain.2 When the original compound patent expired, generic manufacturers were able to launch their products but were required to use a “skinny label”—a product label that omits the still-patented indication (pain) and only lists the off-patent uses (epilepsy). Pfizer then aggressively litigated, arguing that despite the skinny label, doctors would inevitably prescribe the cheaper generic versions for the patented pain indication, thus inducing infringement of its method-of-use patent.2

Competitive Impact: The litigation, though ultimately unsuccessful for Pfizer in a landmark UK Supreme Court case, created years of legal uncertainty and risk for generic manufacturers.2 This delay was worth billions of dollars in protected sales for Pfizer. The case highlighted the significant challenges posed by method-of-use patents and the skinny label system. Today, the pregabalin market is highly competitive, with generic versions capturing the vast majority of prescriptions and driving down costs significantly.57

Case Study 7: Lipitor (atorvastatin) – The Pediatric and Term Extension Play

Profile: Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin) is a statin drug used to lower cholesterol. It is one of the most commercially successful drugs of all time, once holding the title of the world’s best-selling pharmaceutical with peak annual sales of around $13 billion and projected lifetime sales of $178 billion.44

Timeline: Lipitor’s main U.S. patent was scheduled to expire in late 2011. Through the standard mechanisms of the Hatch-Waxman Act, its exclusivity was extended into mid-2012.3

Strategy Analysis: Lipitor’s extension was not the result of a complex patent thicket or controversial product hop, but rather a textbook execution of the tools provided to innovators by the Hatch-Waxman Act. Pfizer benefited from a Patent Term Extension (PTE) that partially restored the patent time lost during the FDA’s review process.3 More importantly, the company secured a crucial six-month pediatric exclusivity (PED) by conducting studies of the drug in children as requested by the FDA.3 This seemingly short extension was immensely valuable for a drug of Lipitor’s commercial scale.

Competitive Impact: The six-month pediatric extension alone was worth billions of dollars in additional sales for Pfizer. To manage the eventual patent cliff, Pfizer also employed savvy commercial tactics. It launched its own “authorized generic” version of Lipitor through a subsidiary, allowing it to compete in the generic market it had once monopolized.60 Furthermore, it entered into a licensing agreement with the Indian generic manufacturer Ranbaxy, granting it 180 days of exclusivity for the first generic launch.60 This allowed Pfizer to control the timing and initial phase of generic competition, ensuring a more gradual decline in revenue rather than an abrupt fall.

Case Study 8: Crestor (rosuvastatin) – The Orphan Drug Exclusivity Angle

Profile: Crestor (rosuvastatin), developed by AstraZeneca, is another highly successful statin used to treat high cholesterol. It reached peak global sales of $5.8 billion in 2013 before facing generic competition.45

Timeline: Crestor’s primary substance patent expired in the U.S. in January 2016. Its market exclusivity was extended by six months, to July 2016, due to pediatric exclusivity.61 Further exclusivity for certain indications extended protection to 2023.3

Strategy Analysis: AstraZeneca employed a multi-faceted strategy to maximize Crestor’s revenue before the loss of exclusivity. Like Pfizer with Lipitor, it secured a valuable six-month pediatric exclusivity extension.61 More uniquely, just before the main patent expired, AstraZeneca gained FDA approval for Crestor to treat a very rare genetic condition: pediatric homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH).14 This approval granted Crestor a seven-year Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) for that specific, narrow indication.14

Competitive Impact: The orphan drug designation was a strategic move. While it did not prevent generics from being approved for the broad cholesterol-lowering indications, AstraZeneca attempted to leverage it to create legal and regulatory hurdles for its competitors. The company petitioned the FDA to require that generic labels include the complex pediatric HoFH safety information, a move that could have complicated the generic approval process. The FDA and a federal court ultimately rejected this demand.14 Nonetheless, the combination of pediatric exclusivity and the orphan drug strategy helped to prolong the drug’s revenue stream and manage its lifecycle. Since generic rosuvastatin entered the market in 2016, Crestor’s sales have significantly declined due to intense price competition.45

Case Study 9: Viagra (sildenafil) – A New Purpose, A New Patent

Profile: Pfizer’s Viagra (sildenafil) famously transformed the treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED) and became a cultural phenomenon. It is also approved under the brand name Revatio for treating a serious condition called pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).46

Timeline: The main patent covering Viagra for ED was set to expire in 2012. However, Pfizer was able to maintain patent protection on the sildenafil compound for its use in treating PAH until 2020.3

Strategy Analysis: This is another prime example of a “new method of use” patent extending a drug’s commercial life. While the blockbuster patent for ED was expiring, Pfizer’s separate patent for the PAH indication remained in force.33 This created a complex and fragmented patent landscape.

Competitive Impact: After 2012, generic sildenafil became available in the U.S., but it was technically only approved for the PAH indication (Revatio). Doctors were free to prescribe this cheaper generic version “off-label” for ED, but Pfizer was able to continue its powerful direct-to-consumer marketing for the Viagra brand, which was still protected by formulation and dosage patents.46 Pfizer also engaged in aggressive litigation and strategic settlements with generic manufacturers like Teva to manage the timing of generic Viagra entry.46 This led to a confusing international patchwork of patent situations, with Viagra’s patent being invalidated in some countries like Canada and Brazil years before its U.S. expiration.46 The strategy allowed Pfizer to extract significant value from the Viagra brand for several years after its primary patent had fallen.

Case Study 10: Nexium (esomeprazole) – The “Purple Pill” and the Power of Isomers

Profile: Marketed by AstraZeneca, Nexium (esomeprazole) is a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) used to treat acid reflux and other related conditions. Known as “the purple pill,” it became a massive blockbuster, with Medicare Part D alone spending $2.66 billion on the drug in 2014.35

Timeline: Nexium’s primary U.S. patent expired in 2014, but its exclusivity was extended through various secondary patents until 2018.3

Strategy Analysis: Nexium’s success is a direct result of a “chiral switch” strategy combined with a masterful marketing campaign. AstraZeneca’s first blockbuster PPI was Prilosec (omeprazole), which was set to lose patent protection in 2001. Omeprazole is a racemic mixture of two isomers (mirror-image molecules), an S-isomer and an R-isomer. AstraZeneca isolated the S-isomer, named it esomeprazole, and patented it as a new chemical entity.34 The company’s clinical trials suggested that esomeprazole provided a marginal improvement in efficacy for a subset of patients compared to Prilosec.35 Armed with this new patent and data, AstraZeneca launched a massive marketing campaign to convince doctors and patients to switch from Prilosec to the “new and improved” Nexium just before Prilosec went generic.35

Competitive Impact: The strategy was immensely successful. Millions of patients were migrated from Prilosec to the newly patented Nexium, allowing AstraZeneca to preserve its multi-billion-dollar PPI franchise for many more years.35 This tactic of patenting an incremental modification of an old drug and marketing it as a superior successor is a classic form of evergreening. It effectively created a new monopoly from an expiring one, delaying widespread, low-cost generic competition in the PPI class for years and costing the healthcare system billions.

The Ripple Effect: Economic and Societal Consequences of Extended Monopolies

The sophisticated strategies employed to prolong drug monopolies have consequences that reverberate throughout the entire healthcare ecosystem. While generating immense profits for innovator companies, these extended periods of market exclusivity impose significant and quantifiable costs on payers, patients, and the very process of pharmaceutical innovation itself. The result is a system where the intended balance between rewarding invention and ensuring affordable access is often tilted heavily in favor of the former.

Quantifying the Cost: Impact on Payers, Patients, and the Healthcare System

The most direct consequence of delayed generic and biosimilar competition is financial. During the extended monopoly period, brand-name drugs are sold at premium prices, free from the competitive pressure that typically drives prices down by 80-90% or more.41 These high costs are borne by public payers like Medicare and Medicaid, private insurance companies, and ultimately, by patients through premiums, deductibles, and co-pays.

The scale of this financial impact is staggering. Humira’s U.S. sales in 2020 alone were $16.1 billion, a figure largely protected by its patent thicket.38 The lifetime sales of Revlimid have surpassed $100 billion, a sum enabled by strategies that delayed full generic competition.53 The delay of Enbrel biosimilars in the U.S. is estimated to cost the healthcare system approximately $1 billion for every year they are kept off the market.51 This dynamic creates stark international price disparities; for example, a monthly supply of Eliquis can cost over seven times more in the U.S. than in Australia, and U.S. patients pay up to eight times more for Ozempic than their European counterparts.30 These are not just abstract numbers; they represent a direct transfer of wealth from the healthcare system and its participants to the shareholders of a few pharmaceutical companies. The empirical evidence consistently shows that stronger IP rules and longer monopolies are associated with increased drug prices and higher costs for both consumers and governments.4

Stifling Competition: The Chilling Effect on Generic and Biosimilar Development

Beyond the direct financial costs, evergreening strategies have a “chilling effect” on the competitive landscape. The creation of dense patent thickets and the threat of serial, high-cost litigation can deter generic and biosimilar companies from even attempting to enter a market.12 The business risk becomes untenable. Developing a biosimilar is already an expensive and lengthy process, costing between $100 million and $300 million.64 When this investment must be followed by a legal battle against a hundred or more patents, where losing on a single claim can result in crippling damages, many potential competitors will choose not to proceed.28

This is precisely the intended effect of the patent thicket strategy. It allows brand-name companies to delay competition by relying on the sheer volume and cost of challenging their patents, rather than on the innovative merit of the patents themselves.29 The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM), which represents generic and biosimilar manufacturers, has repeatedly argued that these tactics are not about protecting true innovation but are abuses of the patent system designed to unlawfully block competition.27 This lack of competition not only keeps prices high but also limits patient and physician choice, locking the market into a single, high-cost product for years or even decades longer than intended by law.

The Innovation Paradox: Does Evergreening Foster or Hinder Breakthrough Research?

The central justification for strong patent protection is that it fosters innovation. Innovator companies argue that the revenue generated during a drug’s monopoly period, including any extensions, is essential to recoup the billion-dollar-plus investment required for R&D and to fund the search for the next generation of breakthrough cures.1 From this perspective, life-cycle management is a prudent business practice that ensures the long-term viability of the innovation engine.

However, a growing body of evidence and criticism suggests that the evergreening model may actually stifle true innovation. The controversy hinges on the definition of “innovation.” When a company develops a new extended-release formulation or isolates a single isomer, it is presented as an improvement that benefits patients.1 Critics, however, argue that these are often low-risk, incremental tweaks designed primarily to extend a patent, not to achieve a significant therapeutic advance.1

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Instead of investing billions in high-risk research to find a truly novel therapy for an unmet medical need, a company may find it more profitable and less risky to dedicate its resources to developing minor variations of its existing blockbuster drug to extend its monopoly.1 Data showing that 74% to 78% of new drug patents are for modifications of existing drugs, rather than for new molecular entities, supports this view.6 This “innovation paradox” raises a critical question for policymakers: does the current system, by rewarding incrementalism so handsomely, divert resources and talent away from the kind of high-risk, high-reward research that leads to genuine medical breakthroughs?

The Battleground for Reform: Stakeholder Perspectives and the Legislative Horizon

The profound economic and societal consequences of extended drug monopolies have ignited a fierce and multifaceted debate over patent reform. This battleground features a range of stakeholders with competing interests—patient advocates, generic and biosimilar manufacturers, and innovator pharmaceutical companies—each vying to influence the legislative and judicial landscape. In recent years, this pressure has begun to yield tangible results, with courts and regulators showing increased scrutiny of the most aggressive evergreening tactics.

The Voice of the Patient: Advocacy for Affordability and Access

Patient advocacy groups have become a powerful force in the push for patent reform. Organizations like Patients For Affordable Drugs Now (P4ADNow) and Generation Patient frame the issue in stark, human terms: patent abuse is not an abstract legal issue but a direct barrier that prevents people from affording the medicines they need to live.12 P4ADNow highlights that one in three Americans cannot afford their prescriptions and argues that bills that would further strengthen patent protections, such as the PREVAIL Act, are “dangerous” and “rig the system in favor of the pharmaceutical industry at the expense of patients”.30

These groups advocate for policies that would curb anti-competitive tactics, such as limiting the number of patents that can be asserted in litigation and banning “pay-for-delay” agreements.12 Their core argument is that the patent system’s purpose should be to serve public health, and when it is manipulated to prioritize profits over patients, it has failed in its mission.

The Generic and Biosimilar Industry’s Position on Fair Competition

The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM), which represents the generic and biosimilar industries, is at the forefront of the legal and legislative fight against patent abuse. While AAM supports strong IP protection for true innovation, it argues that brand-name companies too often use the system to block competition indefinitely with thickets of low-quality, non-innovative secondary patents.27

AAM’s proposed solutions focus on rebalancing the system. They advocate for strengthening the inter partes review (IPR) process at the USPTO, which provides a cheaper and more efficient mechanism for weeding out “bad” patents than federal court litigation.27 They also support legislation like the ETHIC Act, which would limit a brand’s ability to assert numerous patents from the same family against a competitor, thereby thinning the patent thicket.64 The AAM also defends patent settlements as a pro-competitive tool that can bring lower-cost drugs to market years earlier than would be possible through litigation, pointing to the billions of dollars in savings generated by such agreements.28

The Innovator’s Defense: Protecting R&D Investment

Innovator companies and their trade organizations, such as PhRMA, consistently defend robust patent protections as the essential foundation of biomedical progress. Their defense, often articulated in legal filings and public statements, is that the revenue generated from a successful drug, including during its extended life, is necessary to justify the enormous financial risks of R&D.2 The development of a single new drug can cost over a billion dollars and take more than a decade, with a high rate of failure.

From this perspective, strategies like obtaining patents on new formulations or delivery systems are not abuses but legitimate rewards for continued innovation that can improve a drug’s safety, efficacy, or patient convenience.1 They argue that weakening patent protections or restricting their ability to defend their IP would disincentivize investment, ultimately harming patients by slowing the pipeline of new, life-saving therapies.

Recent Judicial and Regulatory Developments

The tide may be slowly turning against the most egregious patent extension strategies. A confluence of public pressure, increased regulatory scrutiny, and key court decisions has begun to erect new guardrails.

- Regulatory Scrutiny: The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has become more aggressive in challenging patent practices it views as anticompetitive, including the improper listing of patents in the FDA’s Orange Book.66 The USPTO itself has proposed rule changes aimed at making it more difficult to build patent thickets using strings of related patents.67

- Judicial Rulings: The courts are also playing a critical role. In Teva v. Amneal (2025), the Federal Circuit ruled that device patents that do not claim the active drug ingredient are improperly listed in the Orange Book, a direct challenge to the strategy used for drugs like Lantus.66 In

Amgen v. Sanofi (2025), the Supreme Court affirmed a high bar for the “enablement” requirement for antibody patents, making it more difficult to secure overly broad patents that claim a function without detailing how to achieve it across the full scope of the claim.68 These rulings signal that courts are less willing to accept patents that are not supported by specific and substantial scientific disclosure. - Proposed Legislation: Several bipartisan bills have been introduced in Congress to address these issues. Proposals aim to cap the number of patents that can be asserted in litigation, ban pay-for-delay deals, and provide statutory safe harbors for “skinny labels” to ensure method-of-use patents do not unfairly block generics.12

While the path to comprehensive reform is long and contested, these developments indicate a system that is beginning to self-correct in response to the well-documented excesses of the past two decades.

Conclusion: The Future of Pharmaceutical Innovation and Patent Strategy

The history of the ten longest-running drug patents is more than a chronicle of commercial success; it is a definitive case study in the strategic mastery of a complex and exploitable legal and regulatory framework. The analysis reveals that extraordinary patent longevity is not an accident but the calculated result of “evergreening” or “life-cycle management” strategies. These strategies, from building impenetrable patent thickets and product hopping with new formulations to leveraging every available statutory exclusivity, have successfully extended drug monopolies for years, and in some cases decades, beyond the standard 20-year patent term. This has generated hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue for innovator companies while simultaneously imposing immense and well-documented costs on the U.S. healthcare system and limiting patient access to more affordable medicines.

The central conflict is a definitional one, revolving around the term “innovation.” The current system has proven to be exceptionally effective at rewarding incrementalism—minor modifications that, while sometimes offering convenience, rarely provide transformative therapeutic benefits. This has created a powerful incentive for companies to invest in low-risk life-cycle management for existing blockbusters rather than pursuing high-risk, truly novel research for unmet medical needs. The result is an innovation paradox, where the very system designed to foster breakthroughs may inadvertently be channeling resources away from them.

However, the landscape is evolving. A confluence of heightened public outrage, more aggressive regulatory scrutiny from the FTC, and a series of critical court decisions is beginning to rein in the most flagrant abuses. The era of the simple evergreening tactic may be waning as legal and regulatory headwinds grow stronger.

Looking ahead, the next frontier of intellectual property battles is already taking shape around biologics, cell therapies, and gene therapies. These cutting-edge modalities present even greater complexity and opportunity for IP protection.17 For these treatments, the “process is the product,” and the intricate, proprietary manufacturing methods and trade secrets may become even more durable barriers to competition than traditional composition-of-matter patents.37 The 12-year statutory exclusivity for biologics already provides a longer runway for building these defenses. Future IP conflicts will be fought on this more complex technological and legal terrain, demanding even greater expertise from all stakeholders.

Ultimately, the fundamental tension between rewarding innovation and ensuring affordable access will remain the central policy challenge for the foreseeable future. The lessons learned from the past two decades of pharmaceutical evergreening are not merely historical. They are an essential guide for policymakers, investors, and industry participants navigating the future of pharmaceutical competition. Achieving a system that both vigorously encourages genuine, breakthrough innovation and guarantees that the fruits of that innovation are accessible to all who need them will require a more nuanced, adaptive, and vigilant regulatory approach than ever before.

Works cited

- Evergreening Strategy: Extending Patent Protection, Innovation or Obstruction?, accessed July 27, 2025, https://kenfoxlaw.com/evergreening-strategy-extending-patent-protection-innovation-or-obstruction

- Pfizer loses Lyrica medicine patent case in UK Supreme Court, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/pfizer-loses-lyrica-patent-case/

- The Top 10 Longest-Running Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-top-10-longest-running-drug-patents/

- What is the impact of intellectual property rules on access to …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9013034/

- Humira – I-MAK, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/i-mak.humira.report.3.final-REVISED-2020-10-06.pdf

- Evergreening – Wikipedia, accessed July 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evergreening

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway – FDA, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- What is Hatch-Waxman? – PhRMA, accessed July 27, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/what-is-hatch-waxman

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed July 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- What is Hatch-Waxman Act? – DDReg Pharma, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.ddregpharma.com/what-is-hatch-waxman-act

- Hatch-Waxman Act – Practical Law, accessed July 27, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Glossary/PracticalLaw/I2e45aeaf642211e38578f7ccc38dcbee

- News — Generation Patient, accessed July 27, 2025, https://generationpatient.org/blog

- Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity – FDA, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity

- The Push for Additional Orphan Drugs: Can the FDA Do More to …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5083072/

- Qualifying for Pediatric Exclusivity Under Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act – FDA, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/qualifying-pediatric-exclusivity-under-section-505a-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-frequently

- The Humira Biosimilars Have Arrived! Will They Make a Difference? – Health Advances, accessed July 27, 2025, https://healthadvances.com/insights/blog/the-humira-biosimilars-have-arrived-will-they-make-a-difference

- Intellectual Property Protection for Biologics – Academic Entrepreneurship for Medical and Health Scientists, accessed July 27, 2025, https://academicentrepreneurship.pubpub.org/pub/d8ruzeq0

- Drug Marketing Exclusivity: Types & Developer Benefits – Allucent, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/types-marketing-exclusivity-drug-development

- Determinants of Market Exclusivity for Prescription Drugs in the United States – Commonwealth Fund, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2017/sep/determinants-market-exclusivity-prescription-drugs-united

- How Long Does Patent Protection Last for Biologics? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 27, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/how-long-does-patent-protection-last-for-biologics

- Market Exclusivity Length for Drugs with New Generic or Biosimilar Competition, 2012-2018 – PubMed, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32654122/

- Supplementary Protection Certificates – Hlk-ip.com, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.hlk-ip.com/knowledge-hub/supplementary-protection-certificates-additional-protection-for-regulated-products/

- Supplementary protection certificate – Wikipedia, accessed July 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supplementary_protection_certificate

- Supplementary protection certificates for pharmaceutical and plant protection products – European Commission – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, accessed July 27, 2025, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/strategy/intellectual-property/patent-protection-eu/supplementary-protection-certificates-pharmaceutical-and-plant-protection-products_en

- (PDF) International Journal of Intellectual Property Rights (IJIPR) PATENT EVERGREENING IN PHARMACEUTICALS: IMPACT AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS – ResearchGate, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387934243_International_Journal_of_Intellectual_Property_Rights_IJIPR_PATENT_EVERGREENING_IN_PHARMACEUTICALS_IMPACT_AND_ETHICAL_CONSIDERATIONS

- Enbrel | I-MAK, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/i-mak.enbrel.report-2018-11-30F.pdf

- Stop patent abuse and unleash generic and biosimilar price competition, accessed July 27, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/campaign/abuse-patent-system-keeping-drug-prices-high-patients/

- Patent Settlements Are Necessary To Help Combat Patent Thickets | Association for Accessible Medicines, accessed July 27, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/patent-settlements-are-necessary-to-help-combat-patent-thickets/

- Biological patent thickets and delayed access to biosimilars, an American problem – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9439849/

- STATEMENT: Patients For Affordable Drugs Now Strongly Opposes Reintroduction of Patent Bills That Protect Pharma Profits Over Patients, accessed July 27, 2025, https://patientsforaffordabledrugsnow.org/2025/05/01/statement-patients-for-affordable-drugs-now-strongly-opposes-reintroduction-of-patent-bills-that-protect-pharma-profits-over-patients/

- USD652136S1 – Medical injector – Google Patents, accessed July 27, 2025, https://patents.google.com/patent/USD652136

- First Circuit Finds Device Patent Improperly Listed in the Orange Book – Fish & Richardson, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/first-circuit-device-patent-improperly-listed-orange-book/

- PATENT PLUS: a blinded, randomised and extension study of riociguat plus sildenafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension – ERS Publications, accessed July 27, 2025, https://publications.ersnet.org/content/erj/45/5/1314

- When does the patent for Esomeprazole expire? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed July 27, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/when-does-the-patent-for-esomeprazole-expire

- The Drug Price Controversy Nobody Notices – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4911722/

- Manufacturing history of etanercept (Enbrel ࣨ ): Consistency of product quality through major process revisions – ResearchGate, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320342064_Manufacturing_history_of_etanercept_Enbrel_Consistency_of_product_quality_through_major_process_revisions

- Patent vs. Trade Secret Considerations for Cell and Gene Therapies | MoFo Life Sciences, accessed July 27, 2025, https://lifesciences.mofo.com/topics/patent-vs-trade-secret-considerations-for-cell-and-gene-therapies

- The top 15 blockbuster patent expirations coming this decade …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.fiercepharma.com/special-report/top-15-blockbuster-patent-expirations-coming-decade

- The best-selling drugs in 2024 – Biostock, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.biostock.se/en/2025/03/lakemedlen-som-salde-bast-under-2024/

- Did the Federal Circuit doom Amgen’s Enbrel® monopoly? – IPWatchdog.com | Patents & Intellectual Property Law, accessed July 27, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2017/11/10/federal-circuits-doom-amgens-enbrel-monopoly/id=89929/

- When do the REVLIMID patents expire, and when will REVLIMID go …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/tradename/REVLIMID

- Lantus sales decline as competition heats up at Sanofi – PMLiVE, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmlive.com/pharma_news/lantus_sales_decline_as_competition_heats_up_at_sanofi_929619/

- Pfizer loses Lyrica patent case in UK Supreme Court – Pharma IQ, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.pharma-iq.com/regulatorylegal/articles/pfizer-loses-lyrica-patent-case-in-uk-supreme-court

- Atorvastatin (Lipitor): Top 12 Drug Facts You Need to Know, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugs.com/article/atorvastatin.html

- CRESTOR historic drug sales – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/drug-sales/drugname/CRESTOR

- Sildenafil – Wikipedia, accessed July 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sildenafil

- Increasing access to lifesaving treatments: How Humira® biosimilars will reshape the healthcare industry – Cardinal Health Newsroom, accessed July 27, 2025, https://newsroom.cardinalhealth.com/2023-08-21-Increasing-access-to-lifesaving-treatments-How-Humira-R-biosimilars-will-reshape-the-healthcare-industry

- Amgen Wins U.S. Patent Battle on Arthritis Drug Enbrel – The Rheumatologist, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/amgen-wins-u-s-patent-battle-on-arthritis-drug-enbrel/

- New Amgen Enbrel patent could block biosimilars until 2028, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/news/New-Amgen-Enbrel-patent-could-block-biosimilars-until-2028

- Sandoz Is 0-3 in Enbrel Patent Case – Center for Biosimilars, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/sandoz-is-0-3-in-enbrel-patent-case

- US Supreme Court denies Sandoz petition to review biosimilar Erelzi® (etanercept-szzs) case | Novartis, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/us-supreme-court-denies-sandoz-petition-review-biosimilar-erelzi-etanercept-szzs-case

- Nine More Years? Sandoz Loses Again On Enbrel Biosimilar – Citeline News & Insights, accessed July 27, 2025, https://insights.citeline.com/GB150038/Nine-More-Years-Sandoz-Loses-Again-On-Enbrel-Biosimilar/

- Why Is Cancer Drug Revlimid So Expensive? – ProPublica, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.propublica.org/article/revlimid-price-cancer-celgene-drugs-fda-multiple-myeloma

- Purdue Pharma – Wikipedia, accessed July 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purdue_Pharma

- OxyContin, the FDA, and Drug Control | Journal of Ethics | American …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/oxycontin-fda-and-drug-control/2014-04

- Payer Controls Limiting Semglee Uptake Despite Patient Demand, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/payer-controls-limiting-semglee-uptake-despite-patient-demand

- Pregabalin Market Size & Industry Report, 2025-2033 – Global Growth Insights, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.globalgrowthinsights.com/market-reports/pregabalin-market-108464

- Global Pregabalin Market Size, Share, and Trends Analysis Report – Industry Overview and Forecast to 2032, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.databridgemarketresearch.com/reports/global-pregabalin-market

- Lipitor: Why It Remains the Best-Selling Drug in Pharmaceutical …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.accio.com/business/lipitor-best-selling-drug-in-history

- Drug Patent Expirations and the “Patent Cliff” – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/drug-patent-expirations-and-the-patent-cliff

- AstraZeneca settles litigation over CRESTOR patent, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2013/astrazeneca-crestor-patent-litigation-settled-25032013.html

- www.drugpatentwatch.com, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/drug-sales/drugname/CRESTOR#:~:text=Crestor’s%20market%20share%20in%20statins,to%20%242.1%20billion%20in%202023.

- DOSE OF REALITY: I-MAK REPORT FINDS BIG PHARMA’S PATENT ABUSE WILL GENERATE BILLIONS OF DOLLARS FOR MANUFACTURERS WHILE DELAYING COMPETITION – CSRxP.org, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.csrxp.org/dose-of-reality-i-mak-report-finds-big-pharmas-patent-abuse-will-generate-billions-of-dollars-for-manufacturers-while-delaying-competition/

- Patent Thickets and Litigation Abuses Hinder all Biosimilars, accessed July 27, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/press-releases/patent-thickets-and-litigation-abuses-hinder-all-biosimilars/

- Intellectual Property & Patent Reform | Association for Accessible Medicines, accessed July 27, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/advocacy/intellectual-property-patent-reform/

- Landmark Ruling Reshapes Pharmaceutical Patent Litigation – Today’s General Counsel, accessed July 27, 2025, https://todaysgeneralcounsel.com/landmark-ruling-reshapes-pharmaceutical-patent-litigation/

- STAT quotes Sherkow on pharmaceutical patents – College of Law, accessed July 27, 2025, https://law.illinois.edu/stat-quotes-sherkow-on-pharmaceutical-patents/

- Life Sciences Companies Have New Avenue to Challenge Patent Applications After Federal Court Ruling | Parker Poe, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.parkerpoe.com/news/2025/05/life-sciences-companies-have-new-avenue-to-challenge

- Biopharmaceuticals: Patenting Challenges in Gene Editing Technologies – PatentPC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patenting-challenges-in-gene-editing-technologies