In pharmaceuticals intellectual property isn’t just a legal shield; it’s the very currency of progress. For every life-saving drug that reaches the market, there lies a trail of immense investment, breathtaking scientific risk, and a painstakingly constructed fortress of patents. These patents are the bedrock upon which multi-billion dollar franchises are built. Yet, for too long, many in the industry—from fledgling biotechs to savvy investors—have viewed these critical assets through a one-dimensional lens: as a barrier to competition. But what if that perspective is fundamentally incomplete? What if your patent portfolio is not just a defensive moat but a dynamic, liquid financial instrument waiting to be unlocked?

Welcome to the new frontier of pharmaceutical strategy, where drug patent data transcends its traditional role. We are moving beyond mere legal status checks and expiry date tracking. Today, sophisticated players are harnessing this data as the primary input for complex IP valuation models and pioneering patent-backed financing structures. This transformation is turning intangible assets into tangible capital, fueling the next wave of innovation, and creating unprecedented competitive advantages.

This is not a theoretical exercise. This is a practical playbook for C-suite executives, venture capitalists, IP managers, and life science entrepreneurs. We will journey deep into the methodologies that allow you to precisely quantify the economic value of your patent portfolio. We’ll dissect the financial instruments that can convert that value into non-dilutive or minimally dilutive growth capital. You’ll learn how to move from a defensive posture to an offensive strategy, leveraging your most valuable assets to fund R&D, navigate clinical trials, and secure a dominant market position. Get ready to rethink everything you thought you knew about the value locked within your patent vault.

The Bedrock of Biotech: Why Patents Reign Supreme in Pharma

Before we can even begin to discuss valuation and financing, we must first establish a core truth: in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors, patents are not just part of the business model; they are the business model. Unlike in the tech industry, where trade secrets, network effects, or branding can provide a sustainable advantage, the pharma world operates on a starkly different principle: a molecule’s structure can be reverse-engineered with relative ease. Without the government-granted right to exclude others from making, using, or selling a patented invention for a limited time, the entire economic incentive to innovate would evaporate.

The Double-Edged Sword of Pharmaceutical R&D

The journey from a promising molecule in a petri dish to a prescription in a patient’s hand is one of the most arduous and expensive endeavors in modern commerce. The statistics are as staggering as they are sobering. The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development estimates that the total capitalized cost to develop a new prescription drug and bring it to market is approximately $2.6 billion [1]. This figure accounts for the high cost of failure; for every one drug that successfully navigates the gauntlet of preclinical research and three phases of human clinical trials to gain regulatory approval, thousands of candidates fall by the wayside.

This process can take over a decade, a period during which a company is hemorrhaging cash with no revenue to show for its efforts. This immense, front-loaded risk creates a cavernous “valley of death” for many early-stage companies. Investors are asked to pour hundreds of millions of dollars into an enterprise with an uncertain outcome far in the future. What convinces them to take this leap of faith? The promise of a temporary, legally-enforced monopoly on the other side. The patent is the light at the end of the R&D tunnel, the mechanism that allows a company to recoup its massive investment and, hopefully, turn a profit that can fund the search for the next cure. Without it, the entire model collapses.

Patents as a Moat: Securing Market Exclusivity

A patent, at its core, is a strategic asset designed to create a period of market exclusivity. This exclusivity is the “moat” that protects a company’s “castle” of revenue generated by a successful drug. During this period, the patent holder can set a price that reflects not just the marginal cost of manufacturing a pill, but the amortized cost of a decade of failures, the cost of capital, and the value the drug provides to patients and the healthcare system.

This period of exclusivity allows for several critical business functions:

- Recouping R&D Investment: As discussed, this is the primary economic justification.

- Building a Brand: Companies use this time to establish their drug’s brand name (e.g., Lipitor®, Humira®) in the minds of physicians and patients, creating a “stickiness” that can even persist after patent expiry.

- Funding Future Innovation: The profits generated from one blockbuster drug are often the seed corn for the entire R&D pipeline of a pharmaceutical giant, funding research into dozens of other disease areas.

- Establishing a Market: For first-in-class drugs, the exclusivity period is used to educate the market, develop treatment guidelines, and integrate the new therapy into the standard of care.

However, this moat is not impregnable. It is constantly under assault from competitors seeking to design around the patents, challenge their validity in court, or launch generic versions the moment the last patent expires. This dynamic, adversarial environment is precisely why understanding the details of patent data is so crucial. The strength, breadth, and remaining lifespan of this moat are the key variables in any credible valuation.

The Hatch-Waxman Act and Its Global Counterparts

In the United States, the interplay between branded drugs and generic competition is largely governed by the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act [2]. This landmark legislation struck a delicate balance. On one hand, it created a streamlined pathway for generic drug approval (the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA), which has saved the U.S. healthcare system trillions of dollars. On the other hand, it compensated innovators for the patent life lost during the lengthy FDA approval process through a mechanism called Patent Term Extension (PTE).

Hatch-Waxman also created a complex system of “patent linkage,” where the FDA cannot grant final approval to a generic drug until the relevant patents on the branded drug have expired or been successfully challenged in court. This system gives rise to high-stakes patent litigation, where a generic challenger’s “Paragraph IV certification” (a claim that the branded drug’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed) automatically triggers a 30-month stay of FDA approval while the dispute is litigated. The outcome of this litigation can shift billions of dollars in market value overnight. Similar frameworks exist in other major markets like Europe, creating a global patchwork of regulations that must be navigated. Understanding these legal frameworks is not just for lawyers; it’s essential for anyone trying to value a pharmaceutical asset, as they directly impact the effective market exclusivity period, which is the single most important driver of revenue forecasts.

Unlocking the Vault: An Introduction to Drug Patent Data

If patents are the bedrock of pharmaceutical value, then patent data is the geological survey map that reveals its composition, depth, and structural integrity. To the untrained eye, a patent is a dense, jargon-filled legal document. But to a trained analyst, it is a rich tapestry of technical, legal, and commercial information. Moving beyond a superficial understanding of patent numbers and expiry dates is the first step toward leveraging this data for sophisticated financial modeling.

Beyond the Basics: What Constitutes “Drug Patent Data”?

When we talk about “drug patent data,” we’re referring to a multi-layered ecosystem of interconnected information points. It’s far more than just the abstract and claims of a single patent document. A comprehensive dataset includes:

- Core Patent Information: This includes the patent number, issue date, title, abstract, full specifications, and—most critically—the claims, which legally define the boundaries of the invention.

- Patent Term: The nominal term of a U.S. patent is 20 years from its earliest non-provisional filing date. However, the actual expiry date is a calculated value, not a static one.

- Legal Status: Is the patent currently in force? Has it lapsed due to non-payment of maintenance fees? Has it been invalidated by a court or a post-grant review proceeding?

- Patent Linkage: Which patents are listed in the FDA’s “Orange Book” (formally, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations) as covering a specific drug? This linkage is the trigger for Hatch-Waxman litigation. For biologics, a similar but distinct process exists under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), often referred to as the “Purple Book” [3].

- Litigation History: Has this patent been challenged before? What were the outcomes? A patent that has survived multiple legal challenges is often considered significantly more robust and valuable.

- Prosecution History: This is the complete record of communication between the inventor’s attorney and the patent office (e.g., the USPTO). It reveals which claims were initially rejected and why, the arguments made to overcome those rejections, and any disclaimers made about the scope of the invention. This “file wrapper” is a goldmine for assessing patent strength and potential vulnerabilities.

Patent Families, Continuations, and Divisionals

A single drug is rarely protected by a single patent. Innovators build a “patent estate” or “thicket” around their valuable assets. This involves understanding the concept of a patent family: a collection of patent applications filed in various countries that relate to the same or similar inventions, often stemming from a single priority application. A broad international patent family is an indicator of a drug with perceived global commercial potential.

Within the U.S., innovators use several strategic tools to broaden and extend their protection:

- Continuation Applications: These allow an applicant to file a new application (before the parent application issues or is abandoned) that claims subject matter disclosed but not necessarily claimed in the parent. This is often used to pursue claims of a different scope or to keep an application pending to cover future developments or competitor workarounds.

- Divisional Applications: When a patent examiner determines that an initial application contains more than one distinct invention, they will issue a “restriction requirement.” A divisional application is filed to pursue claims to the “restricted” invention(s).

- Continuation-in-Part (CIP) Applications: These add new matter to the disclosure of the parent application. Claims that rely on the new matter are only entitled to the filing date of the CIP, not the parent, which has significant implications for the 20-year patent term.

Understanding this web of related applications is critical. A competitor might find a way around one patent, only to discover that a pending continuation application has been amended to specifically block their new approach. This strategic use of the patent system creates a dynamic and shifting landscape that must be continuously monitored.

Legal Status, Expiry Dates, and Patent Term Adjustments (PTAs)

The single most important piece of data for any financial model is the final expiry date, as it defines the end of the high-margin revenue stream. This date is not a simple calculation. It starts with the 20-year term from the priority filing date and is then modified by several factors:

- Patent Term Adjustment (PTA): The USPTO grants PTA to compensate for delays during patent prosecution. If the patent office takes longer than specified by statute to examine the application, days are added back to the patent’s term. This can add months or even years of valuable exclusivity.

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): As mentioned under Hatch-Waxman, PTE is granted to compensate for regulatory review delays by the FDA. A company can get back up to half the time spent in clinical trials and the full time spent in FDA review, capped at a total of five years of extension and a total effective patent life of no more than 14 years post-approval.

- Terminal Disclaimers: To overcome an “obviousness-type double patenting” rejection (where an application is deemed too similar to an inventor’s earlier patent), an applicant can file a terminal disclaimer. This links the expiry date of the new patent to the expiry date of the earlier patent. This can prematurely shorten a patent’s life and is a critical detail to catch.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: A powerful incentive, this grants an additional six months of market exclusivity (attaching to all existing patents and regulatory exclusivities) if the drug sponsor conducts pediatric studies requested by the FDA. This six months can be worth hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars for a blockbuster drug.

Calculating the final, adjusted expiry date requires careful aggregation of all these factors. A mistake here can have a dramatic impact on a valuation model.

Key Data Sources and Platforms

Gathering, cleaning, and integrating this complex web of data is a monumental task. While primary sources like the USPTO’s PAIR system, the FDA’s Orange Book, and court records (via PACER) are the ultimate ground truth, they are notoriously difficult to use for large-scale analysis. Their data is often siloed, unstructured, and not designed for financial modeling.

This is where specialized commercial databases and platforms become indispensable. Services like DrugPatentWatch provide immense value by aggregating, curating, and structuring this information into a user-friendly and analyzable format. Instead of manually piecing together expiry dates, litigation statuses, and international family members, a user can access a comprehensive profile of a drug’s patent estate in one place. These platforms are purpose-built for the kind of analysis we are discussing. They often include:

- Calculated and verified patent expiry dates, including PTA and potential PTE.

- Links between patents, drugs, and NDAs/BLAs.

- Detailed litigation intelligence, including parties, dates, and outcomes.

- Information on regulatory exclusivities (like Orphan Drug Exclusivity or New Chemical Entity Exclusivity) that provide protection independent of patents.

- API access that allows this structured data to be fed directly into proprietary valuation models.

Using such a service is no longer a luxury; it is a necessity for any serious player in the IP valuation and financing space. It allows analysts to spend less time on data janitorial work and more time on high-level strategic analysis—the very core of turning data into dollars.

The Art and Science of IP Valuation in Pharmaceuticals

With a firm grasp of the necessary data, we can now turn to the central challenge: assigning a credible monetary value to a patent or a portfolio of patents. IP valuation is a discipline that blends rigorous financial analysis with subjective legal and technical judgment. It’s more art than science in some respects, but the science provides the framework that makes the art defensible. In the pharmaceutical space, where the asset being valued is often the sole driver of future revenue, getting this right is paramount.

Why Standard Valuation Models Fall Short for IP

If you asked a standard financial analyst to value a manufacturing company, they would likely start by looking at its tangible assets (factories, equipment) and its historical financial statements (revenue, profit margins). This approach is woefully inadequate for a pre-revenue biotech or even for valuing a specific drug within a large pharmaceutical company.

- Lack of Tangible Assets: A biotech’s most valuable assets might be stored in a freezer and on a server. Its physical footprint is negligible compared to its intellectual capital.

- No Financial History: A pre-revenue company has no sales or earnings to analyze or project from. Its value is entirely based on future potential.

- Binary Outcomes: The development process is characterized by binary risk. A Phase III trial either succeeds or it fails. There is often no middle ground. Standard valuation models struggle to accommodate these sharp, non-linear outcomes.

- Uniqueness: Every patented invention is, by definition, unique. This makes finding “comparable assets” for a market-based valuation extremely difficult.

Therefore, we must turn to specialized methodologies that are purpose-built to handle the uncertainty, technical complexity, and unique nature of pharmaceutical patents.

The Three Pillars of IP Valuation

In the world of asset valuation, there are three generally accepted approaches. Each has its place in pharma IP valuation, though they are not all created equal.

H4: The Cost Approach: A Baseline, But a Flawed One

The Cost Approach values an asset based on the cost to create or replace it. For a patent, this could be interpreted in two ways:

- Cost to Create: This would include the R&D expenditures, patent filing and prosecution costs, and scientists’ salaries that went into the invention.

- Cost to Replace/Design-Around: This estimates what it would cost a competitor to invent a non-infringing alternative that achieves the same therapeutic effect.

Limitations: The Cost Approach is deeply flawed as a primary valuation method for pharma patents. The cost of R&D has almost no correlation with the ultimate market value of a drug. A billion-dollar research effort can lead to a failed drug, while a serendipitous discovery costing far less could become a multi-billion dollar blockbuster. It completely ignores the economic potential of the invention. While the “design-around” cost can be a useful input for assessing the strength of a patent’s moat, the approach is best seen as establishing a rock-bottom floor value. It tells you what was spent, not what it’s worth.

H4: The Market Approach: Finding Comparables in a Unique World

The Market Approach, as its name suggests, values an asset by looking at the prices paid for similar assets in recent transactions. This is the standard method for valuing real estate—you look at what similar houses in the neighborhood have sold for.

In the context of IP, this means looking for:

- License Agreements: Analyzing the royalty rates, upfront payments, and milestone payments for patents on similar drugs in similar stages of development.

- Asset Sales: Looking at the purchase price when a company acquires a specific drug candidate or a small biotech focused on a single asset.

- Litigation Awards: Examining damages awarded in patent infringement cases for comparable technologies.

Limitations: The primary challenge here is the “C” word: comparability. Is a patent on a new Alzheimer’s drug really comparable to one for a new oncology drug? They have vastly different risk profiles, market sizes, and competitive landscapes. Even within oncology, is a CAR-T therapy comparable to a small molecule kinase inhibitor? Transaction details are also often confidential, making it difficult to find reliable public data. While databases of licensing deals exist and provide useful benchmarks, the Market Approach is often used as a “sanity check” or a secondary method to support a valuation derived from another approach. It can provide a range, but rarely a precise number.

H4: The Income Approach: The Gold Standard for Pharma Patents

The Income Approach is, by a wide margin, the most relevant and powerful method for valuing pharmaceutical patents. It focuses not on past costs or comparable sales, but on the future economic income the patent is expected to generate. The most common manifestation of this approach is the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model.

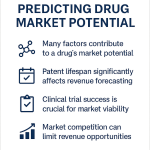

The logic is simple: a patent’s value is the present value of the future cash flows it will help generate over its effective life. The process involves several key steps:

- Forecast Revenue: This is the most critical and challenging input. It requires a deep analysis of the target disease’s epidemiology, the total addressable market (TAM), the drug’s likely market share (penetration rate), and its pricing and reimbursement strategy. This forecast must extend until the patent’s final expiry date, at which point a sharp “patent cliff” is modeled, where revenue drops dramatically due to generic entry.

- Estimate Expenses: Forecast the costs associated with generating that revenue, including the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), Sales, General & Administrative (SG&A) expenses, and ongoing R&D for line extensions or new indications.

- Calculate Free Cash Flow (FCF): FCF is calculated as Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) times (1 – tax rate), plus depreciation and amortization, minus capital expenditures, minus changes in working capital. This represents the cash available to be distributed to the asset’s owners (in this case, the patent holders).

- Determine the Discount Rate: The future cash flows are uncertain. The discount rate is used to convert these future, risky cash flows into their equivalent value in today’s money. A higher risk profile demands a higher discount rate, which results in a lower present value. For pre-revenue biotechs, the discount rate can be very high (30-50% or more) to reflect the immense clinical and regulatory risk. For an approved, marketed drug, the rate would be closer to a standard corporate Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), perhaps 8-12%. This is often called a “risk-adjusted” DCF or rNPV (risk-adjusted Net Present Value), where the cash flows in each year are also multiplied by the probability of success at that stage (e.g., 60% chance of passing Phase III).

- Calculate Net Present Value (NPV): Each year’s projected FCF is discounted back to the present day using the chosen discount rate, and these present values are summed up. The resulting NPV is the estimated value of the patent asset.

The beauty of the DCF model is its granularity. It forces the analyst to build a complete business case for the drug, molecule by molecule, assumption by assumption. Every input, from market share to patent expiry date, can be stress-tested in a sensitivity analysis to understand which variables have the most impact on the final valuation.

Advanced Valuation Models: Moving Beyond the Basics

While the rNPV/DCF model is the workhorse of pharma IP valuation, more sophisticated models are gaining traction, particularly for early-stage assets where flexibility and uncertainty are the dominant features.

H4: Real Options Analysis (ROA): Valuing Flexibility in R&D

Think about a patent on a drug candidate just entering Phase I trials. A standard DCF model would heavily discount its future cash flows due to the massive risk, likely resulting in a very low, or even negative, NPV. This might suggest the project should be abandoned.

However, this ignores a crucial element: managerial flexibility. The company doesn’t have to slavishly follow the development path. It has the option, but not the obligation, to proceed to the next stage. After seeing the Phase I data, management can choose to:

- Invest further (exercise the option to proceed to Phase II).

- Abandon the project (let the option expire).

- Delay the decision (wait for more information).

- License or sell the asset to another company.

This strategic flexibility has real economic value. Real Options Analysis (ROA) applies the principles of financial option pricing (like the famous Black-Scholes model) to value these “real” assets. In this analogy:

- The investment cost of the next clinical trial is the strike price.

- The present value of the cash flows if the drug is successful is the stock price.

- The time until the decision must be made is the time to expiration.

- The volatility of the drug’s potential value is the stock volatility.

ROA can demonstrate that even a project with a negative NPV might have significant value because of the potential for a massive upside if the early trials are successful. It provides a more nuanced framework for valuing early-stage, high-risk, high-reward opportunities, which are the lifeblood of the biotech industry.

H4: Monte Carlo Simulations: Embracing Uncertainty

One of the biggest weaknesses of a standard DCF model is that it uses single-point estimates for each input (e.g., market share will be 25%, price will be $10,000/year). We know this is an illusion of precision. In reality, each of these variables exists within a range of possibilities.

A Monte Carlo simulation addresses this head-on. Instead of using a single number, the analyst defines a probability distribution for each key input variable. For example:

- Market Share: Most likely 25%, but could be as low as 15% or as high as 40% (e.g., a triangular distribution).

- Time to Launch: Most likely 4 years, but with a normal distribution around that mean.

- Probability of Success: A binomial distribution (success or failure).

The model then runs the DCF calculation thousands or even tens of thousands of times, each time randomly picking a value for each variable from its defined distribution. The result is not a single valuation number, but a probability distribution of all possible valuation outcomes. This is incredibly powerful. Instead of just saying “the patent is worth $500 million,” you can say, “there is a 90% chance the value is greater than $200 million, a 50% chance it is greater than $550 million, and a 10% chance it exceeds $1.2 billion.” This provides a much richer understanding of the risk and reward profile of the asset, which is invaluable for both investment decisions and financing negotiations.

Bayesian Analysis: Updating Beliefs with New Data

The drug development process is a journey of learning. We start with a low degree of confidence in a drug’s potential, and with each piece of data—from preclinical studies to clinical trial results—we update our beliefs. The Bayesian statistical framework is perfectly suited for this.

In valuation, a Bayesian approach starts with a “prior belief” about a drug’s probability of success and potential value. This might be based on data from similar drugs or platform technologies. Then, as new information arrives (e.g., positive Phase I safety data), we use Bayes’ theorem to update our initial belief into a more refined “posterior belief.” This new belief then becomes the prior for the next stage.

This method allows for a dynamic valuation that formally incorporates new evidence as it becomes available. It’s particularly useful for valuing platform technologies, where success in one program can increase the perceived probability of success for other programs based on the same platform. It provides a structured way to answer the question: “How much does this new data change what we think this asset is worth?”

By combining the rigor of the Income Approach with the sophistication of Real Options, Monte Carlo, and Bayesian methods, analysts can build a multi-faceted and robust valuation model that truly reflects the complex reality of pharmaceutical IP. This detailed, defensible valuation is the cornerstone upon which patent-backed financing is built.

From Valuation to Capitalization: The Rise of Patent-Backed Financing

Once you have a credible, data-driven valuation for your intellectual property, a new world of strategic finance opens up. For too long, the primary way for a biotech to raise capital was through equity financing—selling ownership stakes to venture capitalists or through public offerings. While essential, this method is dilutive to existing shareholders, including the founding scientists and early investors. Patent-backed financing offers a powerful alternative or complement, allowing companies to leverage the value of their core assets without necessarily giving up a piece of the company itself.

The Financing Gap for Pre-Revenue Biotech

Traditional banks are often hesitant to lend to early-stage life sciences companies. Why? Because these companies lack the typical collateral that banks understand. They have no hard assets like factories or inventory, no predictable accounts receivable, and no history of positive cash flow. Their primary asset—the patent portfolio—is seen by traditional lenders as intangible and difficult to value or seize in case of default.

This creates a significant financing gap. A company might have a drug candidate valued at $100 million based on a rigorous rNPV model, but be unable to secure a simple $5 million loan. Venture debt can sometimes fill this gap, but it’s often tied to a recent equity round and comes with restrictive covenants and equity warrants. This is where specialized, IP-focused lenders and investors have stepped in, creating innovative financial products that treat the patent portfolio as the primary collateral.

What is Patent-Backed Financing?

Patent-backed financing is a broad term for a range of funding mechanisms where the loan or investment is secured, either directly or indirectly, by the value and future cash flows of a company’s patents. These structures are designed by financiers who have deep expertise in both IP law and pharmaceutical markets. They can perform the sophisticated due diligence required to get comfortable with the patent’s strength, validity, and commercial potential.

“Intangible assets now constitute 90 percent of the asset value of the S&P 500… The value of the S&P 500 today is $25 trillion in market capitalization. The value of the intangible assets, most of which are patents, is $22.5 trillion. This is the biggest economic sea change that no one knows about.” — David Kappos, Former Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office [4]

This seismic shift in what constitutes corporate value necessitates a corresponding shift in how that value is financed. Let’s explore the primary structures.

H4: Debt Financing: Collateralizing the Crown Jewels

This is the most straightforward form of patent-backed financing. A lender provides a term loan, and the borrower grants the lender a security interest in a specific patent or the entire patent portfolio. If the borrower defaults on the loan, the lender has the right to seize the patent(s) and sell them to recover their capital.

For this to work, the lender must be confident in two things:

- The Value of the Collateral: The lender will perform its own rigorous IP valuation, often using the same Income Approach models we’ve discussed. They will typically lend only a fraction of their estimated value (a loan-to-value ratio, or LTV) to create a safety cushion.

- Their Ability to Monetize: The lender needs a clear path to monetizing the patents in a default scenario. This could involve selling the patents to a large pharmaceutical company, a patent aggregator, or even spinning up a new entity to continue development.

These loans are particularly attractive for companies that are approaching a major value inflection point, such as the release of Phase III data or an FDA approval decision. A company might take on $20 million in patent-backed debt to fund the final push for commercial launch, avoiding the significant dilution that a “pre-commercial” equity round would entail. The interest rates are higher than traditional bank debt, reflecting the higher risk, but the cost is often far less than the cost of equity dilution.

H4: Royalty Financing (Synthetic Royalties)

Royalty financing, also known as a synthetic royalty, is a highly popular and flexible tool in the biopharma world. It’s not a loan, but rather the sale of a future revenue stream.

Here’s how it works: An investor pays the company a lump sum of cash upfront. In return, the company agrees to pay the investor a percentage of the future sales (a “royalty”) of a specific drug or group of drugs for a defined period or up to a certain total cap.

Key Features:

- Non-Dilutive: The company receives cash without giving up any equity.

- Risk-Sharing: The investor only gets paid if the drug is successful and generates sales. If the drug fails, the company owes nothing further. This aligns the interests of the company and the investor.

- Tailored Structures: The royalty rate can “tier” up or down based on sales levels. The term can be limited to the life of key patents. The total payout can be capped at a multiple of the initial investment (e.g., 3x to 5x), after which the royalty obligation disappears.

This structure is essentially a real-world application of the Income Approach valuation. The investor is buying a slice of the future cash flows that were forecasted in the DCF model. The price they are willing to pay upfront is their own risk-adjusted present value calculation of that future royalty stream. Companies like Royalty Pharma have built multi-billion dollar businesses on this model, providing capital to drug developers at all stages, from late-stage clinical development to commercialization.

H4: Equity and Hybrid Models

Some financing structures blend elements of debt, royalty, and equity.

- Convertible Debt: A loan that can be converted into equity at a future date, often at a discount to a future financing round. When secured by patents, it gives the lender downside protection (the collateral) and equity upside.

- Debt with Warrants: A patent-backed loan that also includes warrants, which give the lender the right to purchase equity in the company at a predetermined price. This gives the lender an “equity kicker” to compensate for the risk.

- Structured Equity: An equity investment where the investor’s return is tied directly to the success of a specific IP asset rather than the company as a whole. This can be used to fund a high-risk project without putting the parent company at risk (often done through a special purpose vehicle, or SPV).

The choice of structure depends on the company’s stage, its tolerance for dilution, its risk profile, and the specific needs it’s trying to meet.

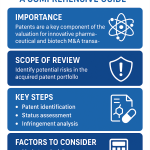

The Investor’s Perspective: Due Diligence on Patent Assets

Investors in this space are not passive financiers; they are deep domain experts. Before deploying a single dollar, they conduct exhaustive due diligence on the underlying IP, which goes far beyond a simple valuation number. Their analysis is a masterclass in risk mitigation.

H4: Assessing Patent Strength: The Litmus Test

An investor needs to know that the patent moat is deep, wide, and will withstand attack. Their due diligence will scrutinize:

- Claim Scope: Are the claims narrow and easy to design around, or are they broad and commanding, covering not just a specific molecule but also its mechanism of action, methods of use, and potential variations?

- Validity: They will commission their own legal experts to analyze the patent’s prosecution history, the prior art, and potential vulnerabilities that a competitor could use to challenge the patent’s validity in court or at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). A patent that has already survived a PTAB challenge (an inter partes review or IPR) is considered significantly “battle-hardened” and more valuable.

- Enforceability: Are there any issues of inequitable conduct during prosecution or other factors that could render the patent unenforceable?

- Patent Thicket Strategy: Does the company have a multi-layered portfolio of patents (composition of matter, formulation, method of use, manufacturing process) that creates overlapping fields of protection and extends the effective exclusivity period?

H4: Freedom to Operate (FTO) and Competitive Landscape Analysis

It’s not enough for a company to have its own strong patents. It must also be free to commercialize its product without infringing on the valid patents of others. A comprehensive Freedom to Operate (FTO) analysis is non-negotiable. This involves a thorough search and analysis of third-party patents to identify any potential roadblocks.

Simultaneously, the investor will map the entire competitive landscape. Who else is working in this therapeutic area? What do their patent portfolios look like? Are there large players who are likely to be aggressive litigants? This analysis, powered by patent data, helps the investor understand the potential for future legal battles and the likely market dynamics post-launch.

H4: The Role of Patent Data in De-Risking Investment

Ultimately, for the investor, every piece of patent data is a tool for de-risking their investment.

- Expiry Dates define the duration of the revenue-generating period.

- Litigation History provides a track record of the patent’s resilience.

- Patent Family Data indicates the global commercial ambition and potential market size.

- Claim Scope determines the defensibility of the market share assumption.

By meticulously analyzing this data, the investor can replace vague optimism with a quantifiable assessment of risk. They can model different scenarios: What if a key patent is invalidated two years early? What if a competitor launches a drug with a slightly different mechanism? The robustness of the IP portfolio, as revealed by the patent data, directly influences the terms of the financing deal—the interest rate on a loan, the royalty rate on a revenue sale, or the valuation in an equity round.

A Practical Guide: Leveraging Patent Data for Valuation and Financing

We’ve covered the theory, the models, and the financial structures. Now, let’s walk through the practical steps a company would take to translate its patent portfolio into a financing opportunity. This is where the rubber meets the road, transforming data into a compelling investment narrative.

Imagine a mid-stage biotech, “NeuroGenova,” with a promising Phase II candidate for Parkinson’s disease. They have a core composition of matter patent and several pending method-of-use applications. They need $50 million to run their pivotal Phase III trial. Here’s their playbook.

Step 1: Comprehensive Data Aggregation and Cleaning

NeuroGenova’s first step is to get their house in order. Their IP counsel and internal team will work to build a complete and verified database of their IP assets. This isn’t just a list of patent numbers. It’s a structured dataset, likely managed through a dedicated IP management system and supplemented with data from a service like DrugPatentWatch to ensure accuracy and completeness.

This master file will include:

- For each patent/application: Patent number, filing date, issue date, calculated expiry date (including best-case PTA/PTE scenarios), and full family linkage.

- Legal Status: Confirmation of maintenance fee payments, records of any office actions or correspondence with the USPTO/EPO.

- Technical Linkage: Clearly mapping which patents cover which aspects of their lead candidate (the molecule itself, the delivery mechanism, its use in treating specific symptoms).

- Competitive Intelligence: A preliminary landscape of patents held by competitors in the Parkinson’s space.

This clean, centralized data repository is the foundation for everything that follows. Without it, any valuation would be built on sand.

Step 2: Building a Robust Valuation Model

With the data organized, NeuroGenova’s corporate development or finance team gets to work on building the valuation model. They will likely build a risk-adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV) model, perhaps enhanced with a Monte Carlo simulation.

H4: Inputting the Data: Expiry Dates, Market Size, Pricing Assumptions

The model is a complex spreadsheet, and its inputs come from various departments:

- Patent Data (from Step 1): The final, calculated patent expiry date for the core composition of matter patent will define the end of the primary revenue forecast period. This is a hard input. Let’s say it’s 2041 after all adjustments.

- Clinical Team: They provide the probability of success for the Phase III trial. Based on industry benchmarks for neurology, they might estimate a 58% probability of success [5]. They also provide the timeline for the trial and submission for FDA approval.

- Commercial Team: This team does the heavy lifting on the revenue forecast. They research the epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease to determine the total addressable patient population. They analyze existing treatments and the clinical data for NeuroGenova’s drug to project a target market share, which might ramp up from 2% in the first year of launch to 20% at its peak. They conduct pricing studies and consult with reimbursement experts to arrive at a projected net price per patient per year.

- Finance Team: They project the SG&A costs required to launch and market the drug, as well as the ongoing manufacturing costs (COGS). They also determine the appropriate discount rate. Given the Phase III risk, they might select a rate of 25%.

H4: Running the Numbers: A Case Study Walkthrough

The team plugs these assumptions into their rNPV model:

- Revenue Forecast: They build a year-by-year sales forecast from the projected launch in 2028 out to the patent expiry in 2041. After 2041, they model a steep 80% decline in revenue due to generic entry.

- Cash Flow Calculation: For each year, they subtract costs to get to a pre-tax profit, apply a tax rate, and make adjustments to arrive at the unlevered free cash flow.

- Risk Adjustment: The cash flows for each year prior to approval are multiplied by the 58% probability of success. The cash flows post-approval are not probability-adjusted (as they only occur in the “success” scenario).

- Discounting: Each year’s risk-adjusted cash flow is discounted back to its present value using the 25% discount rate.

- Summation: The present values of all annual cash flows are summed up.

The result is the risk-adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV) of the asset. Let’s say the model produces a base-case rNPV of $250 million.

To make this more robust, they run a Monte Carlo simulation. They define ranges for peak market share (15%-25%), price ($50k-$70k), and discount rate (20%-30%). After running 10,000 iterations, they get a distribution of outcomes. They can now say with confidence that the mean valuation is $250 million, with a 95% confidence interval of $150 million to $400 million.

Step 3: Crafting the Investment Narrative

NeuroGenova now has a number, but a number alone doesn’t secure financing. They need to build a compelling story around it. This is where they translate the quantitative analysis into a qualitative investment thesis.

H4: Translating Patent Strength into Financial Projections

Their pitch to potential financiers (whether for debt or a royalty sale) won’t just show the final valuation. It will connect the dots, explaining how the strength of their IP underpins the entire financial forecast.

- “Our core composition of matter patent, expiring in 2041, provides 13 years of market exclusivity post-launch. This long runway is the foundation of our revenue projections.”

- “The broad claims in this patent cover not only our lead molecule but also a class of related compounds, creating a formidable barrier to entry and protecting our market share assumptions from design-around attempts.”

- “Our pending method-of-use patents, if granted, will add another layer of protection and could potentially extend exclusivity for specific patient populations, representing an upside to our base-case valuation.”

- “Our FTO analysis shows a clear path to commercialization, de-risking the project from a legal standpoint and protecting our future cash flows from infringement litigation.”

H4: Presenting to Investors: The Pitch Deck

NeuroGenova assembles a detailed pitch deck and data room for interested investors. The valuation model is a centerpiece. They present not just the base case, but also the sensitivity analysis and Monte Carlo results. This transparency shows sophistication and builds credibility. It allows the investor to see all the assumptions and pressure-test them.

They are seeking $50 million. They can now approach a specialized IP lender and make a powerful case for a patent-backed loan. With an asset valued at a mean of $250 million, a $50 million loan represents a very conservative 20% Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio, giving the lender a massive collateral cushion.

Alternatively, they could approach a royalty financing firm. They could offer to sell a 3% royalty on future sales in exchange for the $50 million upfront. The investor will run their own model, and if they agree with the general forecast, they will see that a 3% royalty stream has a present value well in excess of $50 million, providing them with their target return multiple. Because NeuroGenova has done its homework, they enter these negotiations from a position of strength, armed with data-driven valuation that justifies their “ask” and demonstrates the quality of their underlying assets.

Case Studies: Success Stories and Cautionary Tales

The theoretical framework and practical steps are best understood through real-world context. While many deals are confidential, the principles can be illustrated through archetypal examples of both resounding success and strategic failure.

Success Story: A Biotech Securing Series A with a Strong Patent Portfolio

Consider “OmniThera,” a university spin-out with a novel platform technology for delivering antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) with unprecedented precision. They had no clinical data yet, only strong preclinical results. For a typical seed-stage company, raising a large Series A would be an uphill battle based on the science alone.

However, OmniThera’s founders were strategically savvy. From day one, they worked with top-tier IP counsel to build a fortress around their technology. Before even approaching VCs, they had:

- A foundational patent, granted, with very broad claims covering their core linker technology.

- Multiple pending applications covering specific applications of the technology, different classes of payloads, and manufacturing methods.

- A thorough FTO analysis demonstrating they were not treading on the toes of the major players in the ADC space.

When they went to raise their $30 million Series A, their pitch led with the IP. They presented a valuation model based not on a single drug, but on the platform’s potential, using a Bayesian model that showed how success in one area would increase the value of the others. They argued that the broad, early patent gave them a “tollbooth” position in a hot therapeutic area.

The VCs were impressed. They saw not just promising science, but a de-risked asset. The strength of the patent portfolio gave them confidence that even if the first lead candidate failed, the core technology platform itself was a valuable, defensible asset that could be monetized through licensing or a sale. OmniThera secured its funding at a favorable valuation, a direct result of their proactive IP strategy. The patents weren’t just a shield; they were the cornerstone of the investment thesis.

Cautionary Tale: The Perils of Overvaluing a Weak Patent

Now consider “Vaxinova,” a company developing a new vaccine. They had a single, issued U.S. patent and used it as collateral to secure a significant debt facility from a non-specialist lender. The lender relied on a superficial valuation that took the patent’s existence at face value and accepted the company’s optimistic revenue projections. The valuation model failed to properly account for the patent’s vulnerabilities.

A competitor, a large pharmaceutical giant, saw Vaxinova’s vaccine as a threat. Their in-house legal team analyzed Vaxinova’s patent and discovered two critical flaws:

- Narrow Claims: The patent only covered the specific adjuvant used in Vaxinova’s vaccine formulation. It didn’t cover the core antigen itself.

- Devastating Prior Art: The competitor found a somewhat obscure scientific journal article, published before Vaxinova’s filing date, that they believed anticipated the claims of the patent.

The competitor didn’t even need to launch a product. They simply filed an inter partes review (IPR) petition at the PTAB to challenge the patent’s validity. The mere filing of the IPR cast a dark cloud over Vaxinova’s key asset. The PTAB instituted the review, signaling that the challenger had a “reasonable likelihood” of prevailing [6].

Panic ensued. Vaxinova’s stock plummeted. Their lender, realizing their collateral was now at severe risk of being completely invalidated, issued a notice of default, citing the material adverse change. Vaxinova, unable to refinance, was forced into bankruptcy. The lender was left with a patent that was ultimately invalidated, rendering their collateral worthless.

The lessons are stark:

- For companies: The quality of a patent is far more important than its mere existence. A single, narrow, vulnerable patent is a house of cards.

- For investors/lenders: IP due diligence cannot be a checkbox item. It requires deep legal and technical expertise to probe for weaknesses. Relying on a superficial valuation without stress-testing the underlying patent’s strength is a recipe for disaster. The model is only as good as its inputs, and a key input is the defensibility of the patent itself.

The Future Landscape: Trends Shaping IP Valuation and Financing

The intersection of patent data, finance, and pharmaceuticals is not a static field. It is constantly evolving, driven by technological advancements, new financial players, and shifting legal and regulatory paradigms. Staying ahead of these trends is crucial for maintaining a competitive edge.

The Impact of AI and Machine Learning on Patent Analysis

The sheer volume of patent and scientific literature is beyond human capacity to comprehensively analyze. Artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) are emerging as game-changing tools for IP analysis and valuation.

- AI-Powered Prior Art Searching: AI algorithms can scan millions of global patent and non-patent documents in minutes, identifying relevant prior art with a sophistication that can surpass human searchers. This can lead to more accurate assessments of patent validity early in the process.

- Predictive Analytics: Companies are developing ML models trained on vast datasets of litigation outcomes. These models aim to predict the likelihood of a patent surviving a PTAB challenge or a court case based on factors like its technology class, the examiner who allowed it, the language used in the claims, and the track record of the law firm that prosecuted it. This adds a powerful quantitative layer to validity assessment.

- Automated Landscape Mapping: AI can analyze thousands of patents in a specific technology space and automatically group them into clusters, identifying key players, white space for innovation, and the trajectory of R&D. This automates and enhances competitive landscape analysis.

- Valuation Model Inputs: AI can be used to generate more accurate inputs for valuation models. For example, by analyzing clinical trial data and real-world evidence across an entire disease area, an ML model might generate a more objective probability of success for a new drug than one based on broad industry averages.

As these tools become more sophisticated, they will bring greater speed, accuracy, and objectivity to the valuation process, making patent-backed financing more accessible and reliable.

The Rise of Specialized IP Investment Funds

The success of early pioneers in royalty financing has not gone unnoticed. A new asset class of specialized investment funds is emerging that focuses exclusively on intellectual property. These are not traditional VCs or private equity firms. Their teams are composed of a hybrid of PhD scientists, patent attorneys, and seasoned financiers.

These funds are raising billions of dollars to:

- Provide non-dilutive patent-backed debt and royalty financing.

- Acquire patent portfolios outright from distressed companies or universities.

- Fund patent litigation on behalf of smaller companies in exchange for a share of the winnings (litigation finance).

- Proactively assemble strategic patent portfolios in emerging technology areas.

The growth of this specialized capital pool is fantastic news for innovative companies. It creates a more liquid and competitive market for IP-based financing, giving companies more options and better terms. It also validates the very premise of this article: that pharmaceutical patents are a distinct, valuable, and financeable asset class.

Globalization and Harmonization of Patent Law

Drug development is a global enterprise. A drug’s value is derived from its sales in all major markets—the U.S., Europe, Japan, China, and beyond. This makes the global strength of a patent portfolio a critical component of its valuation.

While patent law remains national, there are powerful trends toward harmonization. The Unified Patent Court (UPC) in Europe, for example, creates a single venue for patent litigation across most of the EU, streamlining enforcement and creating a more predictable legal environment [7]. Similarly, major patent offices are collaborating on work-sharing initiatives like the Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH), which can speed up examination in multiple countries.

For valuators and investors, this means a few things. First, they must have expertise in international patent law and understand the nuances of each major jurisdiction. Second, the trend toward harmonization can simplify global valuation models, as it creates more uniformity in patent life and enforcement mechanisms. A company with a truly global patent portfolio, including protection in key emerging markets like China, will command a premium valuation and have access to a wider array of financing options. The ability to model and defend a global revenue forecast, backed by a global patent moat, will be a key differentiator.

Conclusion: Your Patent Portfolio is More Than a Shield—It’s a Financial Asset

We have journeyed from the fundamental role of patents in the pharmaceutical business model to the intricate details of advanced valuation methodologies and the innovative financial instruments they enable. The central message is both simple and transformative: your company’s intellectual property is not a static legal document to be filed away and forgotten. It is a dynamic, high-value financial asset that can be precisely valued, strategically managed, and actively capitalized.

Viewing your patents through this financial lens changes everything. It elevates the role of the IP team from a cost center to a core part of the corporate finance strategy. It empowers biotech startups to unlock non-dilutive capital to fuel their journey through the clinical valley of death. It provides investors with a sophisticated framework to de-risk their investments and identify true value in a field of high uncertainty.

The tools and techniques are here. Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide the curated data needed to fuel the models. Sophisticated methodologies like rNPV, Real Options Analysis, and Monte Carlo simulations provide the analytical rigor. And a growing ecosystem of specialized financiers provides the capital.

The challenge is no longer one of possibility, but of mindset. Companies that continue to see their patents merely as a defensive shield will be outmaneuvered and out-capitalized by those who have learned how to wield them as a financial sword. By embracing the principles of data-driven IP valuation and exploring the world of patent-backed financing, you can unlock the immense, latent value sitting in your own patent vault and, in doing so, accelerate the pace of innovation and bring life-changing medicines to the patients who need them. The alchemist’s playbook is in your hands.

Key Takeaways

- Patents are the Core Asset: In pharmaceuticals, market exclusivity granted by patents is the primary driver of value, allowing companies to recoup massive R&D investments.

- Data is the Foundation: Sophisticated valuation and financing depend on detailed, accurate, and structured drug patent data, including calculated expiry dates (with PTA/PTE), litigation history, and global patent family linkage.

- The Income Approach is King: The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) / risk-adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV) model is the gold standard for valuing pharma IP, as it directly links a patent’s exclusivity period to future cash flows.

- Advanced Models Provide Nuance: Real Options Analysis (ROA) is crucial for valuing the flexibility in early-stage R&D, while Monte Carlo simulations provide a probabilistic understanding of value, embracing uncertainty rather than ignoring it.

- Patents Can Be Collateral: Patent-backed financing allows companies to raise non-dilutive or minimally dilutive capital. Key structures include term loans secured by patents and royalty financing (the sale of a future revenue stream).

- Due Diligence is Paramount: For both the company seeking funds and the investor providing them, rigorous due diligence on patent strength (claim scope, validity) and Freedom to Operate (FTO) is non-negotiable to avoid catastrophic failures.

- IP is a Financial Strategy: The future of pharmaceutical finance involves leveraging AI for analysis, partnering with specialized IP investment funds, and building a global patent strategy. Viewing IP as a core financial asset is essential for competitive advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How does the rise of biologics and biosimilars change the calculus for patent-backed financing compared to small molecule drugs?

The core principles remain the same, but the details and risks differ significantly. For biologics, the “patent thicket” is often denser and more complex, involving not just the molecule but also manufacturing processes (cell lines, purification methods), formulations, and methods of use. The regulatory pathway for biosimilars, governed by the BPCIA in the U.S., involves a unique “patent dance” of information exchange and litigation waves that differs from the Hatch-Waxman framework. Financiers in this space need deeper expertise in biologics manufacturing and the specific legal nuances of the BPCIA. The value may be more distributed across a portfolio of process patents rather than a single composition of matter patent, making the due diligence on the entire portfolio even more critical.

2. What is the biggest mistake companies make when first trying to use their patents for financing?

The most common mistake is waiting too long and treating it as a last resort. Proactive IP strategy should be integrated with financial strategy from day one. Companies that only seek patent-backed financing when they are desperate for cash often have a weak negotiating position and may not have done the necessary groundwork. This includes failing to build a robust patent portfolio beyond a single patent, not having a clean and verified dataset of their IP assets, and not having a preliminary, data-driven valuation ready. A rushed, reactive approach leads to poor deal terms and can signal weakness to potential investors.

3. Can a company with only pending patent applications, and no issued patents, obtain patent-backed financing?

It is more difficult but not impossible, especially for platform technologies with strong preclinical data from a reputable source. In this case, the financing is really based on the potential of the future patent. An investor would conduct extremely deep “prior art” analysis to gauge the likelihood of broad claims being granted. The financing would likely be structured as a hybrid of equity and a future royalty/debt obligation that only kicks in if and when a key patent is issued. The cost of such capital would be very high to compensate for the significant risk that the patents may never be granted or may issue with very narrow, less valuable claims.

4. How do you value a patent portfolio that covers a platform technology rather than a single drug product?

Valuing a platform is more complex and often relies more heavily on advanced models. A portfolio approach is necessary. One common method is to value the lead product candidate using a standard rNPV model and then add the value of the platform itself. The platform’s value can be estimated using a Real Options framework, where each additional potential product is a separate “option.” Alternatively, one can build a sum-of-the-parts model, creating separate rNPV models for 2-3 of the most promising future applications and applying a higher discount rate or lower probability of success to each. The valuation also heavily considers the potential for out-licensing deals for applications of the platform that the company does not intend to pursue internally.

5. For an investor, what is a key “red flag” in the patent prosecution history of a target asset?

A major red flag is a prosecution history filled with arguments and amendments made to overcome “obviousness” rejections based on very close prior art. This suggests the invention is only incrementally different from what was already known. Specifically, if the patent holder had to significantly narrow their claims, add limiting features, or make strong statements disclaiming certain interpretations (an argument that can create “prosecution history estoppel”) to get the patent allowed, it signals a potentially weak and narrow patent. Such a patent is vulnerable to being invalidated in litigation and is easier for competitors to design around, making it a much riskier piece of collateral for a loan or investment.

References

[1] DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20-33.

[2] Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, Pub. L. No. 98-417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984).

[3] Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA), enacted as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148 (2010).

[4] Pearlstein, S. (2018, September 13). How a ‘bunch of crazy nerds’ are unlocking the real value of the U.S. economy. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/how-a-bunch-of-crazy-nerds-are-unlocking-the-real-value-of-the-us-economy/2018/09/13/463a5664-b779-11e8-a2c5-3187f427e253_story.html

[5] Thomas, D. W., Burns, J., Audette, J., Carroll, A., Dow-Hygelund, C., & Hay, M. (2021). Clinical Development Success Rates and Contributing Factors 2011–2020. BIO Industry Analysis.

[6] 35 U.S.C. § 314(a). “The Director may not authorize an inter partes review to be instituted unless the Director determines that the information presented in the petition… shows that there is a reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail with respect to at least 1 of the claims challenged in the petition.”

[7] Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (2013/C 175/01). Official Journal of the European Union, C 175/1.