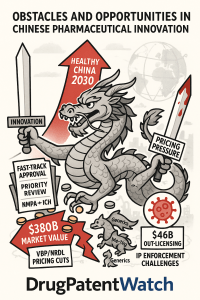

Section 1: The New Architecture of Chinese Pharma: From Global Factory to Innovation Engine

The global pharmaceutical landscape is being fundamentally reshaped by the meteoric rise of China, not merely as a manufacturing hub or a vast consumer market, but as an increasingly potent engine of innovation. The narrative of Chinese pharma has decisively shifted from imitation to invention, a transformation driven not by gradual market evolution but by a deliberate, state-orchestrated strategic pivot. This new architecture rests on three interconnected pillars: a top-down national policy mandate, a radical overhaul of the regulatory apparatus, and a massive, targeted infusion of capital. Together, these forces have engineered a dynamic and hyper-competitive ecosystem, creating a new paradigm for domestic firms, multinational corporations (MNCs), and global investors alike. Understanding the design and implications of this new architecture is the essential first step to navigating the complex array of opportunities and obstacles it presents.

1.1 The Policy Superstructure: The “Healthy China 2030” Mandate

At the apex of China’s pharmaceutical transformation is a clear and ambitious national strategy, most prominently articulated in the “Healthy China 2030” initiative. This is not merely a public health plan; it is a comprehensive blueprint that explicitly identifies the development of a domestic, research-based pharmaceutical industry as a crucial pillar for national health, economic prosperity, and strategic security.1 The initiative provides the high-level political will and strategic direction that underpins all subsequent reforms, signaling a fundamental commitment from the highest levels of government to move the industry up the value chain.

The core objective of “Healthy China 2030” is to create a balanced healthcare system that delivers quality and value while managing costs. A key component of this vision is the cultivation of an “innovation-friendly environment” for drug development.1 The government views a robust, innovative domestic pharmaceutical sector as indispensable for achieving its goals of universal health coverage and building a prosperous society.1 This state-led push is the primary catalyst for the ecosystem’s metamorphosis, influencing everything from research and development (R&D) investment priorities to the integration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) into modern healthcare practices.2

This grand strategy is operationalized through more granular policies, such as the “Pharmaceutical Industry High-Quality Development Action Plan (2023-2025),” which provides concrete support and guidance for the sector’s innovative pursuits.3 The government’s logic is clear: by fostering domestic innovation, China can reduce its reliance on foreign medicines, address the immense healthcare needs of its population, and generate significant economic value through job creation and investment in high-tech R&D.1 This coordinated, top-down industrial strategy demonstrates that China’s rise in pharmaceutical innovation is not a coincidental market phenomenon but a calculated act of statecraft. This engineered nature makes the ecosystem both incredibly dynamic and responsive to state priorities, yet also potentially susceptible to abrupt shifts in policy, creating a unique risk-reward calculus for all participants.

1.2 The Regulatory Revolution: Forging a Path to Global Harmonization

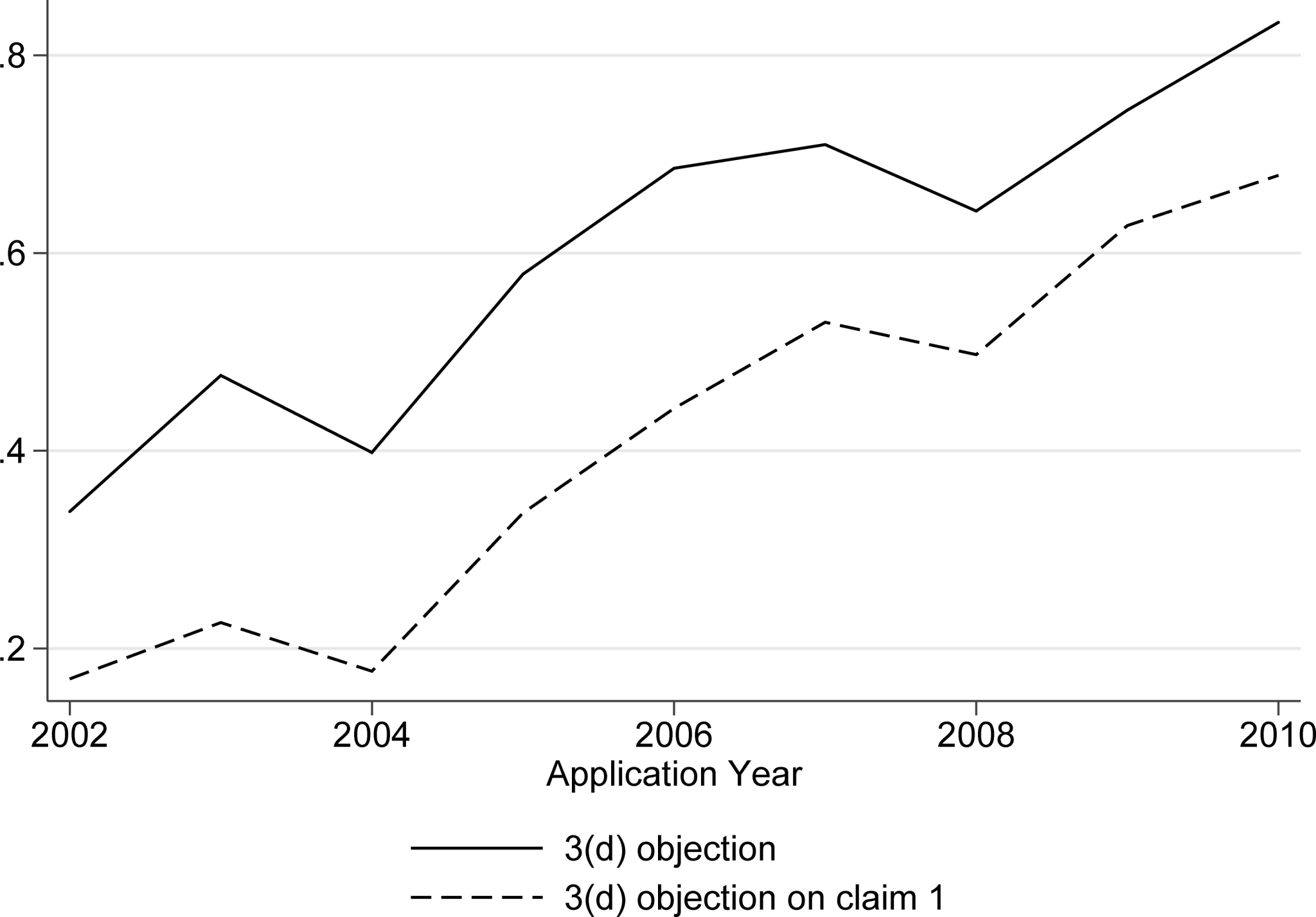

To translate the high-level ambition of “Healthy China 2030” into reality, a radical and rapid overhaul of the country’s drug regulatory system was necessary. Since 2015, China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) and its review body, the Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE), have executed a series of unprecedented reforms. These changes were designed to dismantle historical bottlenecks, accelerate approval timelines, and align China’s regulatory framework with international standards, fundamentally reshaping the drug development landscape.4

A critical first step was addressing the crippling backlog of drug applications that had stifled the system for years. The CDE dramatically expanded its capacity, increasing its review staff from just 150 in 2015 to over 700 by 2018, supplemented by hundreds of external experts. This surge in manpower enabled the agency to clear a staggering 20,000-application backlog within two years, a foundational achievement that allowed the system to pivot from administrative triage to fostering innovation.4

With the backlog cleared, the NMPA introduced a suite of accelerated pathways to shorten review times for new drugs. These include Priority Review, Conditional Approval based on surrogate endpoints, and a Breakthrough Therapy designation for drugs addressing significant unmet needs.4 The impact was immediate and profound. The proportion of new drug applications granted priority review soared from 14% in 2016 to 77% by 2019.4 This relentless push for speed continues; in June 2025, the NMPA proposed a new policy to halve the review time for eligible innovative drug clinical trial applications from 60 to just 30 working days, a move that would align its timeline directly with that of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).7

Perhaps the most significant reform was China’s 2017 accession to the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). This landmark event signaled China’s commitment to global standards and had crucial practical consequences. It enabled the NMPA to accept foreign clinical data and facilitated the inclusion of Chinese sites in global Multi-Regional Clinical Trials (MRCTs).4 This directly addressed the notorious “drug lag,” which previously saw innovative medicines reach the Chinese market an average of five to eight years after their launch in the US or EU.6 The acceptance of overseas data streamlines development, reduces the need for costly and duplicative standalone trials in China, and encourages global companies to include China in their development plans from the outset.6

A final, crucial structural reform was the implementation of the Marketing Authorization Holder (MAH) system. Previously, drug marketing approvals were tied directly to manufacturing licenses, a major barrier for research-focused institutions and small biotechs without their own production facilities.11 The MAH system decouples R&D from manufacturing, allowing innovative startups to focus on discovery and development while outsourcing production to specialized Contract Research Organizations (CROs) and Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs).5 This reform was a structural prerequisite for the emergence of the vibrant and agile biotech startup scene that now defines China’s innovation landscape.

The combination of these reforms has created a powerful competitive advantage. China’s large patient population already allows for faster clinical trial recruitment compared to the West.14 The new, accelerated regulatory pathways amplify this inherent advantage by minimizing administrative delays. The result is an ecosystem where Chinese biotechs can generate proof-of-concept clinical data significantly faster and more cost-effectively than their Western peers.8 This speed has become a key strategic asset, making Chinese innovation attractive to global MNCs who need to fill their pipelines quickly, and it stands as a primary driver of the country’s booming out-licensing activity.8

| Table 1: The NMPA Regulatory Revolution: Key Reforms and Impact (2015-2025) |

| Reform Area |

| IND Approval |

| NDA Approval |

| Clinical Trial Conduct |

| Marketing Authorization |

1.3 The Capital Fuel: Supercharging the Biotech Ecosystem

Policy vision and regulatory reform created fertile ground, but it was a massive influx of capital that provided the fuel for China’s biotech ecosystem to ignite. This flood of investment from venture capital (VC), private equity (PE), and newly accessible public markets created a powerful, self-reinforcing cycle of growth, attracting talent, and spurring intense competition and innovation. The availability of funding is now considered a cornerstone of the ecosystem’s strength.4

The financial transformation has been staggering. The collective market value of Chinese pharmaceutical innovation companies listed on the Nasdaq, Hong Kong Stock Exchange, and Shanghai’s STAR Market exploded from a mere $3 billion in 2016 to over $380 billion by July 2021.15 This was made possible by crucial changes to capital market rules. Notably, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX) amended its listing requirements in 2018 to allow pre-revenue biotechnology companies to go public, a change that opened the floodgates for investment. Shanghai’s technology-focused STAR board followed suit, creating vibrant and accessible financing channels that were previously unavailable to early-stage, R&D-intensive firms.4 In 2020 alone, these two exchanges hosted 21 of 23 Chinese biotech IPOs.4

This public market enthusiasm was mirrored by a booming private funding environment. A dynamic venture capital scene has emerged, with firms pouring billions into promising startups. Chinese biotechs have been able to secure impressive, large-scale funding rounds that rival or even exceed those in the West. For example, mRNA specialist Abogen Biosciences raised a massive $700 million in a Series C round in 2021, one of the largest private biotech financings ever recorded.13 Oncology firm Avistone Biotechnology secured over $200 million in its Series A round, and another $140 million in its Series B to fund its pipeline and commercialization efforts.13 This ample access to capital gives Chinese biotechs the runway needed to advance their pipelines through the costly stages of clinical development.4

The confluence of state-directed policy, regulatory streamlining, and deep capital pools has cultivated a series of thriving biotech hubs. Cities like Shanghai, Suzhou, Beijing, and Hangzhou have become bustling centers of innovation, attracting seasoned scientists—many returning from successful careers in the West—a growing pool of domestic talent, and a critical mass of startups, research institutions, and investors.4 This concentration of resources has created a highly competitive and collaborative environment that is now producing a remarkable output, positioning China as a leading source of new therapies for the global market.

Section 2: Opportunities in a Transformed Market

The new architecture of Chinese pharma has unlocked a powerful set of opportunities for both domestic companies and their international partners. The combination of a vast domestic market with immense unmet medical needs, a newfound and rapidly maturing innovative capacity, and accelerating integration into the global biopharma value chain is creating significant value. The opportunities range from serving the colossal internal market to leveraging Chinese innovation as a source of novel assets for worldwide pipelines.

2.1 The Domestic Demand Dynamo: A Market of Unparalleled Scale

The foundational opportunity in China’s pharmaceutical sector is the sheer scale of its domestic market. As the world’s second-largest pharma market, trailing only the United States, its size and growth potential are unmatched.17 The market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.5% between 2024 and 2032, propelled by powerful and enduring demographic and economic trends.2

A key driver is China’s rapidly aging population. The number of citizens over 65 is expanding, leading to a greater incidence of age-related and chronic diseases.12 This demographic shift, combined with the rising disposable income and healthcare awareness of a growing middle class, is fueling tremendous demand for modern medical treatments.12 The prevalence of major diseases is staggering. China records nearly 5 million new cancer cases annually, accounting for roughly a quarter of all diagnoses worldwide.15 It is also home to the world’s largest population of diabetes sufferers, with more than 96 million patients.12

This enormous unmet medical need has directly shaped the focus of the country’s innovation efforts. Oncology has become the primary engine of the domestic R&D pipeline, comprising 62% of all research programs.15 This intense focus is a direct response to the massive burden of cancer in the country and represents a clear market-driven opportunity. For any pharmaceutical company, domestic or foreign, the scale of the Chinese patient base provides a unique and powerful advantage, offering a vast market for both existing and newly developed therapies.12

2.2 China as a Global Source of Innovation: The “License-Out” Boom

One of the most profound shifts in the global pharmaceutical landscape is the reversal of the innovation flow. For decades, the model was dominated by multinational corporations licensing their drugs into the Chinese market. Today, the narrative has been decisively rewritten: China is now a premier source of novel assets for global pipelines, a trend validated by a surge in high-value “license-out” deals where Chinese firms grant global rights for their homegrown innovations to MNCs.16

The numbers tell a compelling story. The combined value of China’s out-licensing deals skyrocketed to approximately $46 billion in 2024.17 A report from Stifel showed that 30% of all licensing deals conducted by major global pharmaceutical companies now involve a Chinese biotech partner.17 This trend is driven by a confluence of factors. On one side, MNCs are facing looming patent expirations on blockbuster drugs and are under immense pressure to replenish their pipelines. On the other, Chinese biotechs, empowered by regulatory speed and efficient clinical trial recruitment, can deliver de-risked assets with compelling early-stage human data much faster than their Western counterparts.8

Landmark deals have underscored the high value now placed on Chinese-developed assets, even in the most competitive therapeutic areas:

| Table 2: The Rise of “License-Out” Powerhouses: Landmark China-to-Global Deals (2022-2025) |

| Chinese Biotech |

| Jiangsu Hengrui |

| 3SBio |

| Akeso Inc. |

| BeiGene |

These deals reflect a new, symbiotic relationship forming between Chinese biotechs and global pharma. Chinese firms excel at early-stage innovation and rapid clinical development, often due to a lack of global infrastructure for late-stage trials and commercialization. MNCs, in turn, need innovative, de-risked assets to fill their pipelines and possess the global expertise and capital to run large-scale Phase 3 trials and launch products worldwide. The out-licensing boom is the clear result of this synergy. For MNCs, the most effective China strategy is evolving from simply selling products to China to actively sourcing innovation from China. For many Chinese biotechs, partnership with Big Pharma represents the most viable path to global success.

2.3 The Rise of Domestic Champions: From Local Giants to Global Contenders

The transformation of China’s pharmaceutical landscape is not only defined by startups but also by the evolution of established domestic players and the emergence of new, globally-minded biotechs. These companies are leveraging their financial strength, scale, and rapidly growing R&D capabilities to compete head-to-head with MNCs, both within China and on the world stage.3

Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals stands as a prime example of this evolution. Once a dominant domestic player in generics and oncology, Hengrui has aggressively pivoted to become China’s leading innovative pharmaceutical firm.3 The company’s commitment to R&D is substantial, with spending reaching RMB 6.15 billion in 2023, representing over 26% of its total revenue.3 This investment is yielding tangible results, with three Class 1 innovative drugs and four Class 2 new drugs approved in 2023 alone, strengthening its portfolio in high-impact areas like oncology, cardiovascular disease, and CNS disorders.3 Hengrui is no longer just a domestic giant; it is a formidable global dealmaker, as evidenced by its massive $6 billion out-licensing deal for its GLP-1 portfolio.17

China Shijiazhuang Pharmaceutical Group (CSPC) has also demonstrated a remarkable ascent, rising to become a top-tier player through aggressive pipeline expansion and global R&D efforts.3 CSPC boasts one of the most ambitious pipelines in China, with over 130 innovative drug projects in development across a wide range of therapeutic areas.3 The company achieved a landmark milestone with the full US FDA approval of Xuanning, an antihypertensive medication. This marked the first time a novel small molecule drug developed entirely by a Chinese company received such approval, a powerful validation of its R&D capabilities on the global stage.3

Other companies like BeiGene and Sino Biopharmaceutical further illustrate this trend. BeiGene was founded from the outset with a global vision and has successfully become a “poster child” for China’s pharmaceutical ambitions, developing and marketing its own innovative oncology drugs worldwide.17 Sino Biopharmaceutical, another established domestic leader, is leveraging its scale and financial muscle to expand internationally through strategic partnerships and heavy investment in its internal R&D pipeline.17 These domestic champions have moved far beyond their origins in generics or modernizing TCM 18; they are now developing globally competitive novel drugs and are increasingly viewed as peers to Western pharmaceutical giants.

2.4 Unique Innovation Frontiers: TCM and Advanced Technologies

Beyond competing in established therapeutic areas, China possesses unique advantages and is cultivating leadership in specific innovation frontiers. These include the systematic modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and the development of cutting-edge technology platforms, which serve as distinctive sources of value and differentiation.

The modernization of TCM is a national strategic priority, explicitly supported by the “Healthy China 2030” plan.2 The approach has evolved from simple herbal remedies to a sophisticated, science-driven process. Companies are applying modern biotechnological and quantitative methods to discover, develop, and validate TCM-derived therapies. A classic example is Shijiazhuang Pharma Group’s development of butylphthalide (NBP), an antihypertensive drug extracted from celery seeds using modern pharmaceutical development processes.18 Today, this integration is being supercharged by technology. Researchers are leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics to dissect complex ancient formulations, identify bioactive compounds, and understand their mechanisms of action, effectively translating centuries of empirical knowledge into scientifically validated treatments.20 This “marriage of tradition and modernity” offers a unique source of new drug candidates for a range of chronic conditions and is a field where China has an unparalleled cultural and scientific advantage.22

Simultaneously, China is establishing a dominant position in select, high-value technology platforms. The ecosystem is producing a disproportionate number of innovations in areas like antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), bispecific antibodies, and cell and gene therapies.5 For instance, Chinese firms are at the forefront of developing novel PD-1xVEGF bispecific antibodies, which have attracted billion-dollar licensing deals from global MNCs.8 Companies like Abogen Biosciences are building proprietary messenger RNA (mRNA) platforms from the ground up, demonstrating self-sufficiency in one of the most advanced areas of biotechnology.13 This specialization in cutting-edge technologies is a key factor behind the high value of assets in out-licensing deals and positions China not just as a follower, but as a potential leader in the next generation of therapeutic modalities.

The intense focus on oncology, which constitutes 62% of the R&D pipeline, serves as a strategic incubator for these broader capabilities.15 Oncology offers relatively clear biomarkers and clinical endpoints, making it an ideal field to demonstrate efficacy quickly. The global regulatory environment, particularly at the FDA, has well-established accelerated pathways for promising cancer drugs. By focusing on oncology, Chinese firms can leverage their inherent speed advantage in patient recruitment to rapidly generate compelling clinical data for globally recognized targets like PD-1 or next-generation targets like TIGIT.24 Success in this high-profile arena—as seen with BeiGene’s Brukinsa or CSPC’s Xuanning—acts as a powerful proof-of-concept for the entire Chinese innovation ecosystem.3 It builds global credibility, attracts capital, and develops talent. In essence, oncology is the training ground where Chinese pharma is honing its R&D skills and navigating global regulatory pathways, providing the foundation to expand into more complex therapeutic areas like immunology, CNS disorders, and cardiovascular disease in the future.3

Section 3: Navigating the Headwinds: Critical Obstacles and Systemic Risks

Despite the immense opportunities, China’s pharmaceutical innovation landscape is fraught with significant obstacles and systemic risks. The very policies designed to catalyze innovation have simultaneously created a high-pressure, commercially challenging environment. Navigating this landscape requires a clear-eyed understanding of the formidable headwinds, which range from severe pricing pressures and a persistent gap between research and commercialization to intellectual property uncertainties and intense market competition. These challenges temper the optimistic narrative and demand sophisticated, risk-aware strategies from all market participants.

3.1 The Price-Volume Paradox: The Squeeze of VBP and NRDL

A central paradox of China’s pharmaceutical market is that the government is simultaneously encouraging high-risk, high-cost innovation while implementing aggressive cost-containment policies that severely erode the commercial value of those innovations. This tension is primarily manifested through two powerful mechanisms: the national Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) program for off-patent drugs and the National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) negotiations for innovative medicines.

The VBP program, initiated in 2018, is a centralized procurement system primarily for generic drugs that have passed a quality consistency evaluation.25 It operates on a “winner-takes-all” or “winner-takes-most” basis, where the company offering the lowest price is guaranteed a massive volume of sales across public medical institutions in a given region.26 This has led to brutal price competition and dramatic price reductions. On average, VBP has driven price cuts of 52-54%, with the price of some drugs plummeting by as much as 96%.26 The policy effectively squeezes the profit margins out of the low-end generic market, creating a powerful incentive for companies to either exit the market or invest in innovation to escape the price war.25

For innovative drugs, the primary hurdle is the NRDL negotiation process. Gaining inclusion on the NRDL is critical for achieving broad market access, as it ensures reimbursement coverage for the vast majority of the population covered by state medical insurance.28 However, this access comes at a steep cost. To be included, manufacturers must agree to substantial, often deep, price cuts. According to a McKinsey survey, pricing pressure from NRDL negotiations is a major concern for 81% of industry participants.4 Even market leaders are not immune; Novo Nordisk, for instance, had to accept price cuts of up to 50% on its insulin portfolio to maintain its market position after inclusion in VBP-like schemes.3

This creates a difficult strategic dilemma for manufacturers of innovative drugs. They can choose to forgo NRDL listing and attempt to sell their product in the small, private-pay market at a premium price, severely limiting patient access and sales volume. Alternatively, they can trade significant margin for volume by accepting a deep price cut to get on the NRDL.28 This price-volume trade-off fundamentally alters the commercial calculus for launching a new drug in China. The government has explicitly linked these two pressures through a policy known as “vacating the cage to change the bird,” where the cost savings generated from VBP for generics are used to create budget space to fund NRDL coverage for new, innovative drugs.25 This system, while effective at controlling overall healthcare spending, creates a high-pressure commercial environment that can make it difficult to recoup the substantial costs of R&D.

| Table 3: The VBP/NRDL Pricing Gauntlet: Summary of Pressures |

| Mechanism |

| Target Drugs |

| Mechanism of Action |

| Observed Price Impact |

| Strategic Implication for Companies |

This pricing system acts as a powerful, double-edged policy tool. On one hand, the VBP system brutally punishes companies that remain in the commoditized generics space, creating a strong “push” factor that forces them to invest in innovation to survive.25 On the other hand, the NRDL system, while rewarding innovation with market access, does so at a price that can make the economics of “me-too” or incremental innovation challenging. The logical strategy to navigate this environment is to develop a drug quickly, get it approved, and maximize revenue in the private-pay market for as long as possible before entering the inevitable NRDL negotiations. This logic inherently favors “fast-follower” or “best-in-class” drugs where the biological target and clinical pathway are already validated, as this is a much faster and less risky path than pursuing a truly novel, first-in-class target. Consequently, the pricing regime, while designed to foster innovation, may inadvertently be creating a “me-too trap,” incentivizing incremental advances over breakthrough science and thus contributing to the R&D-to-commercialization gap for truly novel medicines.

3.2 The R&D-to-Commercialization Chasm: A Gap Between Quantity and Quality

A persistent and fundamental challenge for China’s pharmaceutical sector is the significant gap between its massive R&D inputs and its output of globally recognized, truly innovative products. Despite skyrocketing R&D investment, a world-leading volume of scientific publications, and a surge in patent filings, China’s capacity to consistently translate this activity into first-in-class medicines remains a key weakness.11

A primary cause of this “commercialization chasm” is a structural imbalance in R&D funding. The system is heavily skewed towards later-stage experimental development, which accounted for 83.5% of R&D expenditure in a 2011 analysis, while neglecting foundational basic research, which received only 4.7%.11 This is in stark contrast to the US, where basic research received 19% of funding. This chronic underinvestment in basic science starves the innovation pipeline at its source, limiting the discovery of novel biological targets and mechanisms of action.11 Without a strong foundation in basic research, the ecosystem naturally gravitates towards developing “me-too” or “me-better” drugs that target well-understood pathways, rather than pioneering new ones.

This leads to a phenomenon of intense homogenization and redundant competition. The focus on a limited number of validated targets, such as PD-1 and EGFR in oncology, is significantly more concentrated in China than it is globally.24 While this strategy can be commercially viable in the short term, it reflects a weakness in original discovery and leads to a hyper-competitive landscape where numerous companies are chasing the same patient populations with similar products.12 China’s main strengths currently lie in cost-effective manufacturing, contract research, and generating these “me-too” and “me-better” versions of existing treatments, rather than in originating breakthrough therapies.14

The problem is compounded by systemic issues within academia and talent development. The “SCI-oriented” research assessment system in Chinese universities often incentivizes academics to produce a high quantity of publications rather than focusing on the quality, impact, or industrial relevance of their work.12 This creates a disconnect between academic research and the needs of the pharmaceutical industry. Furthermore, there is a recognized shortage of high-level talent with experience in translational science and clinical research leadership—the very skills needed to bridge the gap between a laboratory discovery and a viable drug candidate.23 The innovation conversion rate in China is estimated to be less than 8% annually, significantly lower than the 50-70% seen in developed countries, highlighting a structural separation between research resources and commercialization capabilities.24

The success of the NMPA’s regulatory reforms has, paradoxically, thrown these deeper weaknesses into sharp relief. In the past, the slow approval system and “drug lag” were often blamed for China’s weak innovation output.12 Now that these administrative bottlenecks have been largely removed, with approval times approaching or even beating Western standards, it has become clear that the true obstacles lie deeper within the ecosystem.8 China has successfully built the “superhighway” of regulatory pathways, but it is now grappling with the more fundamental challenge of producing a sufficient number of truly innovative “vehicles”—first-in-class drug candidates—to run on it. The next phase of China’s innovation journey will require addressing these core issues in basic science, talent development, and academic-industrial linkage, a far more complex and long-term undertaking than reforming administrative processes.

| Table 4: Global Innovation Scorecard: A Comparative Analysis (China vs. US vs. EU) |

| Metric |

| R&D Spend Growth (2010-2022) |

| Public R&D Funding Focus |

| Share of Global Drug Pipeline |

| Share of New Clinical Trials (2022) |

| Venture Capital (VC) Access |

| Innovation Conversion Rate |

3.3 The Intellectual Property Gauntlet: A Double-Edged Sword

China’s intellectual property (IP) environment for pharmaceuticals is a landscape of profound contradictions. On one hand, the country has made substantial and undeniable progress in strengthening its legal framework for patent protection. On the other, persistent challenges in practical enforcement and a perception of systemic bias create a high-risk environment for both foreign and domestic innovators. This duality makes navigating IP in China akin to wielding a double-edged sword: it offers powerful tools for protection but carries significant risks.34

The legislative progress has been significant. The Fourth Amendment to China’s Patent Law, effective in 2021, introduced several measures designed to align the system with international standards and provide stronger recourse for patent holders. These include the introduction of punitive damages of up to five times the compensatory amount for willful infringement, a substantial increase in the cap for statutory damages, and a shift in the burden of proof for damages calculation.34 Furthermore, China has established a patent linkage system, similar to the Hatch-Waxman Act in the US, which allows innovators to challenge generic drug applications before they are approved, triggering a 9-month stay on the generic approval.34 Specialized IP courts have been established in major cities, and data shows that foreign plaintiffs enjoy a high success rate (77%) in infringement cases against Chinese defendants, suggesting that on paper, the system is robust.34

However, these formal improvements are tempered by persistent practical challenges. One of the most significant hurdles is the lack of a US-style discovery process. In Chinese litigation, parties are responsible for collecting their own evidence, which can be exceptionally difficult in complex pharmaceutical cases involving trade secrets and proprietary manufacturing processes.34 This places a heavy and often insurmountable burden of proof on the plaintiff.

Moreover, despite high win rates in major urban courts, concerns about local protectionism and systemic bias remain, particularly in cases involving strategic industries or state-owned enterprises.35 A 2021 EU survey highlighted patent invalidation as a serious problem, with respondents expressing concern that court rulings tend to favor Chinese stakeholders in strategic sectors.35 There is evidence of Chinese courts being used to countersue foreign firms and issue anti-suit injunctions to halt litigation in other jurisdictions, adding another layer of strategic risk.35 For foreign companies, these legal complexities are compounded by language and cultural barriers, making expert local counsel an absolute necessity.34 This creates the “double-edged sword” scenario: the laws provide a strong basis for protection, but the reality of enforcing those rights can be a challenging, costly, and unpredictable gauntlet.34

3.4 The Hyper-Competitive Arena: Fragmentation and Redundancy

The Chinese pharmaceutical market is not only vast but also intensely competitive and highly fragmented. This competition comes not just from the traditional rivalry between MNCs and domestic firms, but also from a crowded field of thousands of local players, many of whom are pursuing similar strategies and targeting the same therapeutic areas.

The market structure is fundamentally different from that of most developed countries. China’s thousands of domestic companies account for approximately 70% of the market, yet the top 10 players control only about 20% of the market share.18 In contrast, in most developed nations, the top 10 companies command roughly half the market.18 This high degree of fragmentation means that no single company has a dominant position, leading to fierce competition for market share.

This landscape is still heavily influenced by the legacy of the generics industry. Generic drugs continue to command a large portion of sales, creating a “race-to-the-bottom” pricing environment that puts constant pressure on margins.18 While VBP is pushing companies towards innovation, the competitive dynamics of the generic market still cast a long shadow over the industry.

The innovation space itself is becoming dangerously crowded. As discussed, the focus on “me-too” and “me-better” drugs has led to severe product homogeneity, particularly in hot therapeutic areas like oncology.14 This results in multiple companies launching similar products targeting the same patient populations and competing for the same limited reimbursement quotas under the NRDL, further intensifying price pressure and making it difficult to achieve a return on investment.

In this environment, MNCs are facing unprecedented pressure. They are no longer just competing with each other but are also being challenged by increasingly sophisticated domestic firms that can offer high-quality alternatives at a fraction of the price. This is particularly evident in the vaccine market, where local manufacturers have developed their own HPV and shingles vaccines, disrupting the premium pricing strategies of global players like MSD and GSK and forcing them to rethink their commercial models in China.37 The government’s clear priority to boost its domestic industry means that the competitive headwinds for foreign firms are likely to intensify.37

3.5 Geopolitical and Cross-Border Complexities

Superimposed on these domestic challenges is a growing layer of geopolitical and cross-border risk. Rising strategic competition between the United States and China, coupled with Beijing’s own increasingly stringent data security regulations, is creating significant new complexities for investment, collaboration, and the conduct of global clinical trials.

From the US side, there is a growing tendency to view biotechnology as a sector of strategic national importance, on par with semiconductors and AI. This has led to increased scrutiny of cross-border deals and investments by bodies like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).16 There is a palpable “decoupling” impulse in some policy circles, which could lead to US companies reducing or severing ties with their Chinese partners and a more protectionist stance towards the industry.16

Simultaneously, China has implemented its own set of strict data security and biosecurity laws. While these regulations provide a competitive advantage to domestic firms, which have unparalleled access to vast pools of Chinese patient data for R&D and AI-driven drug discovery, they create significant hurdles for MNCs.38 The laws place tight controls on the cross-border transfer of human genetic resources and other health-related data, complicating the execution of global clinical trials and the integration of Chinese data into global development programs.29

This dynamic creates a strategic paradox, particularly for the United States. On one hand, national security concerns are driving a policy push to de-risk supply chains and compete with China’s biotech ascent.16 On the other hand, America’s own flagship pharmaceutical companies, facing internal R&D productivity challenges and patent cliffs, are becoming increasingly reliant on the Chinese biotech ecosystem as a vital source of rapid, cost-effective innovation to fill their pipelines.16 This creates a fundamental tension where US policy may seek to contain the very ecosystem that its own industry is increasingly partnering with for its growth and survival.

In response to these dual pressures, some Chinese firms are beginning to hedge their bets by pursuing regional strategies, such as strengthening ties with Southeast Asian nations through frameworks like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This allows them to build more resilient supply chains for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and access new growth markets outside the direct glare of US-China competition.38 For all players, the intersection of science, strategy, and security means that a geopolitically realistic and agile approach is no longer optional, but essential for navigating the future.16

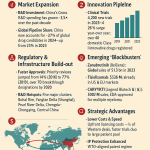

Section 4: Strategic Imperatives and Future Outlook

The transformation of China’s pharmaceutical sector into a global innovation player presents a complex matrix of high-stakes opportunities and deeply entrenched systemic risks. Success in this new era requires moving beyond tactical market-entry approaches to crafting sophisticated, resilient, and differentiated strategies that account for the unique dynamics of the ecosystem. The future trajectory of Chinese pharma will be defined by how stakeholders—multinational corporations, domestic biotechs, and global investors—navigate the central tension between state-driven ambition for innovation and state-enforced pressure for cost containment.

4.1 Crafting a Resilient China Strategy: Differentiated Approaches

The one-size-fits-all strategies of the past are no longer viable. Different players in the ecosystem must adopt tailored approaches to capitalize on the opportunities while mitigating the significant risks.

For Multinational Corporations (MNCs): The strategic imperative for MNCs is to evolve from a model of “In China, For China” (selling products to the domestic market) to one of “In China, For Global” (sourcing innovation from the domestic ecosystem for the worldwide market). This requires a fundamental shift in mindset and operations. It involves not just maintaining a commercial presence, but actively establishing on-the-ground incubators, expanding deal-sourcing capabilities, and forging multifaceted partnerships with local biotechs and CROs to tap into the stream of novel assets.9 Commercially, MNCs must adapt their go-to-market models to survive the VBP/NRDL pricing gauntlet. This may involve pivoting away from an over-reliance on top-tier hospitals towards retail and online pharmacy channels, as well as dedicating more resources to penetrating lower-tier cities and rural markets where growth potential remains.29 Operationally, building robust compliance frameworks to navigate China’s complex data security and cybersecurity laws is non-negotiable to manage the risks of cross-border data transfer.29

For Domestic Biotechs: For the majority of Chinese biotechs, the most direct path to significant value creation lies in global out-licensing deals. Success in this arena depends on a relentless focus on generating high-quality clinical data that meets the rigorous standards of global regulators like the FDA and EMA. This requires planning for internationalization early in the development process, aligning with global quality standards (such as USP), and designing clinical trials with global submission in mind.39 For the few companies with the ambition and resources to commercialize independently in China, success will hinge on pipeline differentiation. They must avoid the hyper-competitive “me-too” spaces and focus on developing assets with a clear clinical advantage that can justify their value in the tough NRDL pricing negotiations.

For Investors: The investment landscape demands a more nuanced and sophisticated approach than ever before. The “capital winter” and depressed valuations in recent years may have created a buyer’s market, but the highest-quality assets with truly differentiated science are still being acquired quickly, requiring speed and decisiveness.16 Due diligence must now extend beyond the traditional assessment of scientific, clinical, and commercial risk. A thorough evaluation must also incorporate the unique pressures of the VBP/NRDL system, the strength of a company’s IP portfolio and its defensibility in Chinese courts, and the rising geopolitical risks that could impact cross-border partnerships and future exit opportunities. Creative deal structures, such as the formation of new companies (NewCos) to house specific assets, are emerging as a way to manage risk and provide flexible financing and exit channels.39

4.2 The Future Trajectory: From “Fast Follower” to “Global Leader”?

The evolution of China’s pharmaceutical innovation ecosystem is likely to occur in distinct phases over the next decade, with the central challenge shifting from building capacity to enhancing the quality and originality of its output.

Short-Term (1-3 years): The current trends are expected to continue and intensify. The ecosystem will remain dominated by “best-in-class” and “me-better” innovation, as this model is well-suited to the current incentive structure. The out-licensing boom will likely persist as Chinese biotechs continue to monetize their key advantages in development speed and cost-efficiency for incremental innovation. On the commercial side, pricing pressures from VBP and NRDL will remain a defining feature of the market, forcing continued consolidation and a focus on cost control. Geopolitical tensions will continue to create uncertainty, prompting companies to build more resilient, localized strategies.

Mid-Term (3-5 years): The focus of both government policy and industry strategy will likely begin to shift more concertedly towards addressing the R&D-to-commercialization chasm. We can anticipate a significant increase in state-led investment into basic research and the creation of targeted talent development programs aimed at cultivating translational science expertise.23 During this period, the first wave of assets that were out-licensed in the early 2020s will generate pivotal late-stage clinical data or reach the market. The success or failure of these assets on the global stage will be a critical validation point, heavily influencing future investment trends and strategic partnerships.

Long-Term (5-10 years): China’s ultimate ability to ascend to the status of a true global leader in pharmaceutical innovation, on par with the United States and Europe, will hinge on its success in resolving the fundamental bottlenecks in its scientific ecosystem. The key metric of success will no longer be the quantity of new drug approvals or the value of licensing deals, but the number of truly novel, first-in-class medicines originating from Chinese labs that become global standards of care. This will require a cultural and strategic shift within the industry, moving from an emphasis on rapid implementation to fostering independent, curiosity-driven innovation and long-term strategic thinking.23

4.3 Concluding Analysis: Balancing Ambition with Reality

China has, in less than a decade, successfully engineered a world-class pharmaceutical innovation ecosystem. Through a combination of unwavering political will, sweeping regulatory reform, and immense capital investment, it has transformed itself from the world’s factory for generics into a global force in drug discovery and development that can no longer be ignored.15 Its share of the global R&D pipeline now rivals that of the United States, and its biotech hubs are vibrant centers of scientific activity.17

However, this remarkable achievement is defined by a central, unresolved tension: the state’s powerful ambition to foster world-leading innovation is in direct collision with its equally powerful mandate to control healthcare costs. The result is the “double-edged sword” that defines the market today. The system’s regulatory speed and vast patient pool create unparalleled opportunities to accelerate development. Yet, its aggressive pricing mechanisms can severely diminish the rewards of that innovation. Its strengthened IP laws offer protection, but enforcement remains a complex gauntlet. Its massive scale offers immense market potential, but also breeds hyper-competition and redundancy.

The future of Chinese pharmaceutical innovation will be shaped by the navigation of these paradoxes. The winners—be they multinational corporations, domestic biotechs, or global investors—will be those who can master this complex environment. They must develop strategies that leverage China’s undeniable strengths in speed, scale, and cost-efficiency while insulating themselves from its intense pricing pressures, its systemic weakness in basic research, and its growing geopolitical complexities. China is no longer just a market to sell to or a factory to produce in; it is a critical, complex, and indispensable node in the global biopharmaceutical network, and engaging with it requires a strategy as sophisticated and multifaceted as the ecosystem itself.

Works cited

- Healthy China 2030: China’s healthcare journey | Bayer Global, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.bayer.com/en/pharma/healthy-china-2030-chinas-healthcare-journey

- China Pharmaceutical Market Estimated to Reach a CAGR of 7.50% during 2024-2032, Impelled by the Rising Geriatric Population – BioSpace, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/china-pharmaceutical-market-estimated-to-reach-a-cagr-of-7-50-during-2024-2032-impelled-by-the-rising-geriatric-population

- China’s pharmaceutical sector: innovation meets demographic …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.imd.org/ibyimd/asian-hub/chinas-pharmaceutical-sector-innovation-meets-demographic-driven-demand/

- The dawn of China biopharma innovation | McKinsey, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/the-dawn-of-china-biopharma-innovation

- Five trends of China’s pharmaceutical industry in 2022 – PMC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10326289/

- Bridging the new drug access gap between China and the United States and its related policies, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10800674/

- China Proposes Reforms to Optimize Drug Trials – Cisema, accessed July 30, 2025, https://cisema.com/en/innovative-drug-trial-optimization-proposals/

- China proposes shorter clinical trial reviews in efforts to accelerate drug development, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/accelerate-drug-development-china-proposes-shorten-clinical-trial-review-time

- China Market Opportunities for International … – L.E.K. Consulting, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.lek.com/sites/default/files/PDFs/china-market-opportunities-pharma.pdf

- Bridging the new drug access gap between China and … – Frontiers, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1296737/pdf

- Obstacles and opportunities in Chinese pharmaceutical innovation – ResearchGate, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315631213_Obstacles_and_opportunities_in_Chinese_pharmaceutical_innovation

- Obstacles and opportunities in Chinese pharmaceutical innovation …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5366105/

- 5 private biotech companies in China you should know about – Labiotech.eu, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.labiotech.eu/best-biotech/china-healthcare-private-biotech-company/

- Lab leader, market ascender: China’s rise in biotechnology | Merics, accessed July 30, 2025, https://merics.org/en/report/lab-leader-market-ascender-chinas-rise-biotechnology

- China, the new epicenter of global pharmaceutical innovation – Servier, accessed July 30, 2025, https://servier.com/en/newsroom/china-global-pharmaceutical-innovation/

- China is Making Large Inroads into Biotech: Is Investment Money …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pharmaceuticalintelligence.com/2025/07/28/china-is-making-large-inroads-into-biotech-is-investment-money-following/

- The Dragon Awakes: Charting the Unstoppable Growth of Chinese …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-dragon-awakes-charting-the-unstoppable-growth-of-chinese-pharmaceuticals-in-the-global-market/

- Pharmaceutical industry in China – Wikipedia, accessed July 30, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharmaceutical_industry_in_China

- China’s Population Decline: Impact on Business and the Economy – China Briefing, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-demographic-shift-how-population-decline-will-impact-doing-business-in-the-country/

- Integrating artificial intelligence into the modernization of … – Frontiers, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2024.1181183/full

- Integration of TCM, modern medicine in the pipeline – Chinadaily …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202503/22/WS67ddfec9a310c240449dc3e7.html

- China’s Medicines: A New Frontier in Global Innovation – Linkdood Technologies, accessed July 30, 2025, https://linkdood.com/chinas-medicines-a-new-frontier-in-global-innovation/

- Shaping Future-Oriented R&D Talent Innovation in China: Part 2, accessed July 30, 2025, https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue/april-2022/shaping-future-oriented-rd-talent-innovation-in-china-part-2/

- New Drug Approvals in China: An International Comparative …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11974572/

- Does China’s national volume-based drug procurement policy promote or hinder pharmaceutical innovation? – PubMed Central, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11236746/

- Healthy China 2030: Pressure on Prices Under Pooled Procurement – Bayer Global, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.bayer.com/en/pharma/healthy-china-2030-pressure-prices-under-pooled-procurement

- Pricentric Insights: China Issues New Volume-Based Procurement …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.eversana.com/2021/02/02/pricentric-insights-china-issues-new-volume-based-procurement-policy-document/

- 2024 China Drug Pricing Update – Pacific Bridge Medical, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pacificbridgemedical.com/publication/2024-china-drug-pricing-update/

- Navigating China’s pharmaceutical industry landscape – PwC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/pharma-life-sciences/china-pharmaceutical-strategy.html

- Obstacles and opportunities in Chinese pharmaceutical innovation – PubMed, accessed July 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28340579/

- A comparative analysis of public R&I funding in the EU, US, and China, accessed July 30, 2025, https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/document/download/6eaa3b4e-2af3-46fd-87b5-aa92e4ad10ee_en?filename=ec_rtd_comparative-analysis-public-funding.pdf&utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

- Despite a decade of gradual growth, R&D spending in Europe …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.efpia.eu/news-events/the-efpia-view/statements-press-releases/despite-a-decade-of-gradual-growth-rd-spending-in-europe-outpaced-by-the-us-with-increasing-competition-from-china-new-data-shows/

- Biotechnologies: Europe struggles with China-US rivalry – Coface, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.coface.com/news-economy-and-insights/biotechnologies-europe-struggles-with-china-us-rivalry

- The Double-Edged Sword: Opportunities and Challenges in China’s …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-double-edged-sword-opportunities-and-challenges-in-chinas-patent-litigation-system/

- Tracking China’s Push To Invalidate Foreign Patents | Selendy Gay PLLC, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.selendygay.com/news/publications/2024-06-20-tracking-chinas-push-to-invalidate-foreign-patents

- Domestic Competition in the Chinese Pharmaceutical Industry – Western University, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.democracylab.uwo.ca/Archives/2016__2017_research_/pharma_in_china/domestic_competition_in_the_chinese_pharmaceutical_industry.html

- Big pharma faces headwinds in China as vaccine sales decline …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/features/big-pharma-faces-headwinds-in-china-as-vaccine-sales-decline/

- Biopharmaceuticals Rising: China’s Strategic Pivot to Southeast Asia Amid Great Power Tech Competition, accessed July 30, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/01/biopharmaceuticals-rising-chinas-strategic-pivot-to-southeast-asia-amid-great-power-tech-competition?lang=en

- Accelerating Chinese Innovative Drugs Going Global: International …, accessed July 30, 2025, https://cbiic.phirda.com/portal/article/index/id/896.html