Part I: The Strategic Imperative of Patent Due Diligence in Pharmaceutical M&A

Section 1.1: Beyond a Legal Formality: Due Diligence as a Core Driver of Deal Value

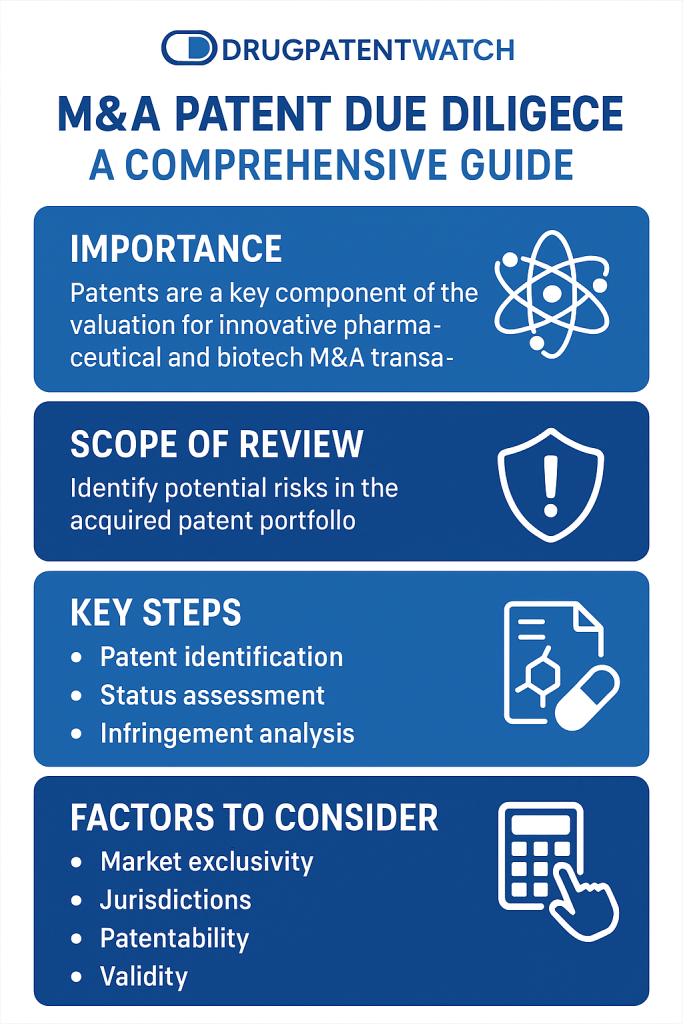

In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical mergers and acquisitions (M&A), intellectual property (IP) is not merely an asset; it is often the cornerstone of a target company’s entire valuation.1 For technology, pharmaceutical, and innovation-driven companies, IP due diligence, and specifically patent due diligence, transcends the role of a routine legal check. It is a foundational element of corporate strategy and a primary driver of deal value.2 Unlike in other industries where tangible assets like factories and equipment may form the bulk of a company’s worth, in the pharma and biotech sectors, the IP is the business.4 A single patent covering a molecule, a biological pathway, or a manufacturing process can be worth billions of dollars, representing the sole basis for a product, a licensing stream, and the very rationale for an acquisition.3

Consequently, patent due diligence is a systematic and rigorous investigation designed to evaluate a target company’s patent portfolio, assessing its legal standing, ownership, enforceability, and strategic fit with the buyer’s goals.1 This process is far more than a defensive measure to avoid liabilities; it is an offensive tool for uncovering hidden value and a critical input for shaping the financial and legal structure of the transaction.2 A thorough review ensures that an acquirer can accurately assess risks, validate the ownership of critical assets, and ultimately maximize the strategic value of the intellectual property being acquired.1 The findings from this crucible of analysis directly influence every facet of the deal, from the negotiation of the purchase price to the drafting of indemnification clauses and the structure of post-closing integration.1

Section 1.2: The Triad of Objectives: Risk Mitigation, Accurate Valuation, and Strategic Alignment

The purpose of patent due diligence in a pharmaceutical M&A context can be distilled into three interconnected objectives: mitigating risk, enabling accurate valuation, and ensuring strategic alignment.

Risk Mitigation: This is the most fundamental objective. The process aims to identify and quantify potential liabilities that could have significant financial and legal consequences after the transaction closes.2 These risks, often referred to as “red flags,” include third-party claims of infringement, which could expose the buyer to costly post-acquisition litigation; disputes over ownership or a broken chain of title, which could mean the target does not actually own its most valuable assets; and fundamental defects in the patents themselves that could render them invalid or unenforceable.2 Uncovering these encumbrances is critical to avoid inheriting a lawsuit or discovering that a billion-dollar asset is, in fact, worthless.2

Accurate Valuation: In the pharmaceutical industry, the vast majority of a company’s value often resides in its intangible IP assets.2 Therefore, a primary goal of due diligence is to ensure the acquirer does not overpay for assets that cannot withstand legal or competitive scrutiny.2 By verifying the validity, enforceability, and scope of the patent portfolio, the diligence process provides a clear-eyed assessment of the true value of the target’s IP.6 This data-driven valuation forms a solid foundation for negotiating a fair purchase price and other deal terms, ensuring that the price paid reflects the actual quality and potential of the intellectual property involved.6

Strategic Alignment: Beyond risk and valuation, due diligence must assess how the target’s patent portfolio aligns with the acquirer’s overarching business objectives.1 An acquirer may be pursuing a deal for various strategic reasons: to bolster a weak product pipeline, to enter a new therapeutic market, to build a defensive patent portfolio to deter competitors, or to establish market dominance in a particular technological area.1 The diligence process must confirm that the target’s patents can actually fulfill this strategic purpose. For example, if the goal is market expansion, the team must verify that the patents provide protection in the relevant geographical territories.1

A critical and evolving aspect of this strategic assessment involves geopolitical and macroeconomic factors. In an environment of increasing regulatory scrutiny, potential tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals, and shifting global drug pricing policies, the geographical footprint of a patent portfolio has become a paramount concern.12 A legally strong patent portfolio concentrated in a jurisdiction facing new tariffs or price controls may be a strategically weak asset. Therefore, modern due diligence must expand its scope to model these policy risks, integrating geopolitical analysis into the IP evaluation. This transforms the process from a reactive legal review into a proactive assessment of global operational risk, where a “good enough” patent in a stable jurisdiction may be more valuable than a “perfect” patent in a volatile one.

Section 1.3: The High-Stakes Environment: Why Pharma IP is Uniquely Complex

The due diligence process in pharmaceutical M&A is uniquely challenging due to the inherent complexity of life sciences intellectual property. Several factors contribute to this high-stakes environment.

First, pharmaceutical patent portfolios are characteristically deep, dense, and difficult to analyze.4 Unlike a consumer products company that may have a few key trademarks, a biotech or pharma company often holds hundreds of patents for a single drug. These patents are layered over time and cover not just the core active molecule but also its methods of manufacture, specific formulations, dosing regimens, delivery systems, and various methods of use for different diseases.4 This “patent thicket” is often filed across dozens of countries, creating a complex global web of rights that must be meticulously mapped and verified.

Second, IP ownership is frequently fragmented. Pharmaceutical innovation is rarely a solitary pursuit; it often involves intricate collaborations with universities, government research institutes, and other corporate partners.4 These joint development and licensing agreements can lead to complex ownership structures, where the target company may only co-own or hold an exclusive license to a portion of the IP essential for its product. Unraveling these agreements to determine true ownership and control is a critical and painstaking task.4

Third, and perhaps most distinctively, market protection in the pharmaceutical industry arises from a symbiotic relationship between patents and a complex system of regulatory exclusivities.4 These exclusivities, such as those for new chemical entities, orphan drugs, or biologics, are granted by regulatory bodies like the FDA and provide a period of market protection that is independent of patent status. These rights are highly jurisdiction-specific and vary significantly between the US and Europe.4 An acquirer must therefore map both the patent landscape and the regulatory exclusivity landscape in every key market to accurately determine a drug’s commercial runway. Overlooking a regulatory exclusivity could lead to a significant undervaluation of an asset.

Finally, the entire industry operates under the shadow of the “patent cliff”.13 The finite lifespan of a patent, coupled with the dramatic and immediate drop in revenue upon its expiration and the entry of generic competition, makes the accurate calculation of a patent’s remaining term a high-stakes exercise. With hundreds of billions of dollars in industry revenue at risk from patent expirations in the coming years, a miscalculation of a key patent’s expiry date, even by a few months, can have a catastrophic impact on a deal’s valuation and economic rationale.4

Part II: Assembling the Diligence Framework: Process, People, and Preparation

Section 2.1: The Cross-Functional Diligence Team: Assembling Legal, Technical, and Commercial Expertise

A rigorous and insightful patent due diligence process cannot be conducted in a silo. Its success hinges on the assembly of a dedicated, cross-functional team that integrates diverse areas of expertise.1 Attempting to conduct this analysis with only patent lawyers is a common and critical mistake. The ideal team is a carefully orchestrated collaboration of specialists who can address the multifaceted nature of pharmaceutical IP.

The core members of this team should include 1:

- Patent Attorneys: These legal experts form the backbone of the team, responsible for analyzing patent validity, enforceability, claim scope, and freedom-to-operate. They interpret the legal nuances of patents and related contracts.

- Technical Experts and Scientists: These individuals, often PhDs with deep domain knowledge in the relevant therapeutic area (e.g., oncology, immunology), are essential for assessing the underlying technology. They help patent attorneys understand the science, evaluate the technical merit of the inventions, and determine the relevance of prior art.

- Regulatory Specialists: Given the critical interplay between patents and regulatory exclusivities, experts in FDA and EMA regulations are non-negotiable. They are responsible for verifying the status and duration of all applicable regulatory protections.

- Financial Analysts: These professionals are tasked with translating the legal and technical findings of the diligence team into financial models. They work to quantify the value of the IP and model the financial impact of identified risks.

- Business Strategists / Corporate Development Professionals: This group ensures that the diligence process remains aligned with the strategic rationale for the acquisition. They help prioritize areas of focus based on the deal’s objectives and integrate the final report into the broader M&A decision-making process.

Identifying the right personnel, both from within the acquirer’s organization and from external advisory firms, is a crucial first step.17 Equally important is establishing a transparent and collaborative working relationship with the target company. Open communication channels can significantly accelerate the retrieval of necessary documents and the clarification of ambiguous points, making the entire process more efficient and accurate.1

Section 2.2: The Phased Approach: From Preliminary Review to Deep-Dive Analysis

Effective due diligence follows a structured, phased approach that allows the team to focus its resources efficiently. This process typically moves from a broad overview to a highly detailed analysis of the most critical assets.

- Phase 0: Pre-Diligence Preparation: Before the formal process begins, the acquiring company must clearly define its strategic goals for the acquisition.1 Is the primary objective to acquire a blockbuster drug, enter a new technology platform, or build a defensive patent portfolio? This strategic framework will guide the entire review, ensuring that the team’s efforts are aligned with the intended use of the patents.10

- Phase 1: Inventory and Categorization: The first operational step is to create a comprehensive inventory of all the target’s patents and pending patent applications.1 This list, often provided by the target in a data room, should be independently verified through public database searches. Once compiled, the portfolio must be categorized along several key axes 1:

- Technology Relevance: Distinguishing between “core” patents that protect the main products and “non-core” patents that are less central to the business.

- Jurisdiction: Mapping the geographic coverage of the portfolio and the filing status in each country.

- Legal Status: Identifying whether each patent is active (granted and in force), pending, or has expired or been abandoned.

- Phase 2: Deep-Dive Analysis on High-Value Assets: It is neither practical nor necessary to conduct a full-scale analysis of every patent in a large portfolio. The principle of materiality dictates that the team should focus its most intensive efforts on the “crown jewel” assets—those patents that underpin the majority of the target’s current and future value.1 For these high-value patents, the team will conduct the exhaustive analysis of ownership, validity, enforceability, and freedom-to-operate that is detailed in subsequent parts of this report.

Section 2.3: Defining Scope and Materiality: Focusing Resources on High-Value Assets

The scope and depth of the due diligence must be tailored to the specifics of each transaction.17 A one-size-fits-all approach is inefficient and can lead to either wasted resources or overlooked risks. The level of detail should be determined by several factors, including the transaction structure, the target’s industry, and, most importantly, the materiality of the IP to the target’s business.17

Materiality can be assessed based on a combination of factors 17:

- Current and anticipated revenue generated from products covered by the IP.

- The dollar amount of royalties or license fees, both payable and receivable.

- The competitive advantage that the IP provides, such as patent protection that excludes competitors from the market.

- The lack of commercially available alternatives for the technology covered by the IP.

A crucial consideration that fundamentally shapes the diligence scope is the structure of the M&A transaction. The decision to structure a deal as an asset purchase versus a stock purchase is not merely a legal or tax consideration; it has direct and profound consequences for the patent diligence process, particularly concerning licensed IP. In a stock purchase, the acquirer buys the target company as a whole, and its existing contracts, including license agreements, generally “flow through” to the new owner automatically.19 However, in an asset purchase, the buyer is acquiring specific assets from the seller. This requires that each individual license agreement be

expressly assigned from the seller to the buyer.19 This act of assignment frequently triggers “anti-assignment” or “change of control” clauses within the license agreements, which stipulate that the consent of the original third-party licensor is required for the transfer.17 Obtaining this consent can be a major hurdle, especially if the licensor is a competitor of the acquirer. Therefore, if a deal is structured as an asset purchase, the diligence team must place a significantly higher priority on scrutinizing the assignment provisions of all in-licensed IP agreements. The feasibility of obtaining these third-party consents can become a major deal risk and a key point of negotiation.

To manage this complexity, the use of standardized checklists is a well-established best practice.1 Resources such as Skadden’s IP Due Diligence Checklist or the checklists provided by Westlaw Practical Law offer comprehensive frameworks that cover the full spectrum of issues, from licensing agreements to litigation history.1 These checklists can be tailored to the specific needs of the transaction, ensuring a systematic and thorough review while allowing the team to focus its efforts where they matter most.

Table 1: Comprehensive Due Diligence Checklist

| Diligence Area | Diligence Item | Key Questions to Ask | Documents to Request | Potential Red Flags | Source(s) |

| I. Ownership & Chain of Title | Inventor Assignments | Have all inventors (employees, founders, contractors) assigned their rights to the company? Was this done before the patent application was filed? | Employment agreements, consulting agreements, invention assignment forms for all named inventors. | Missing assignments; assignments executed after patent filing; ambiguous language in employment contracts. | 1 |

| Recorded Title | Does the public record (e.g., USPTO database) show a clean, unbroken chain of title from the inventors to the target company? | USPTO Patent Assignment Search results (“Abstract of Title”). | Gaps in the chain; unrecorded transfers; assignments to incorrect corporate entities. | 19 | |

| Encumbrances | Are there any liens, security interests, or other encumbrances recorded against the patents? | UCC search results; patent assignment records. | Unreleased security interests from prior financing; government rights from federal funding. | 1 | |

| Joint Ownership | Is any key IP jointly owned with a third party (e.g., a university or development partner)? | Joint development agreements; collaboration agreements. | Any joint ownership. A co-owner can independently license the patent to a competitor without accounting to the other owner. | 19 | |

| II. Validity & Enforceability | Prior Art Search | Is there any prior art (patents or publications) that was not considered by the patent examiner that could invalidate the patent’s claims for lack of novelty or obviousness? | List of known prior art; results of new, independent prior art searches. | Newly discovered, highly relevant prior art; patents with very broad claims. | 1 |

| Prosecution History Review | Were any arguments or claim amendments made during prosecution that limit the scope of the patent (prosecution history estoppel)? | The complete patent “file wrapper” from the relevant patent office. | Amendments made to overcome rejections based on prior art; arguments disclaiming certain interpretations of claim terms. | 25 | |

| Post-Grant Challenge Risk | How vulnerable is the patent to a Post-Grant Review (PGR) or Inter Partes Review (IPR) challenge at the PTAB? | Analysis of patent strength against PGR/IPR standards. | Patent granted within the last 9 months (PGR risk); reliance on a single piece of prior art for novelty (IPR risk). | 27 | |

| Maintenance Fees | Have all required maintenance fees/annuities been paid on time in all jurisdictions? | Maintenance fee payment records from USPTO, EPO, etc. | Missed or late payments, which can lead to a patent lapsing or expiring early. | 1 | |

| III. Freedom to Operate (FTO) | Third-Party Patent Search | Do any of the target’s current or planned products/processes infringe on valid, in-force patents owned by third parties? | FTO search reports from qualified counsel for all key jurisdictions. | Identification of third-party patents with claims that appear to cover the target’s product. | 1 |

| Risk Assessment | What is the level of risk (high, medium, low) for each identified third-party patent? Are the high-risk patents likely valid and enforceable? | FTO opinion letters; validity analysis of high-risk third-party patents. | A high-risk, likely valid patent owned by a litigious competitor. | 31 | |

| IV. Licenses & Agreements | In-Licenses | What IP has the target licensed from third parties? Are these licenses exclusive? Will they transfer to the acquirer? | All in-license agreements, including research, collaboration, and supply agreements. | A critical license that is non-transferable or terminates upon a change of control. | 17 |

| Out-Licenses | What IP has the target licensed to third parties? What rights have been given away? | All out-license agreements. | An exclusive license granted to a third party in a key market the acquirer wishes to enter. | 19 | |

| Change of Control | Do any agreements contain clauses that are triggered by the M&A transaction, requiring consent or causing termination? | All material contracts. | “Change of Control” or “Anti-Assignment” clauses, especially in critical in-licenses. | 17 | |

| V. Litigation & Disputes | Litigation History | Is the target currently involved in, or has it previously been involved in, any IP litigation? | Litigation dockets; settlement agreements; correspondence with opposing counsel. | Ongoing litigation that could result in a large damages award or an injunction against selling a key product. | 1 |

| Threats / Cease & Desist | Has the target sent or received any cease and desist letters or offers to license? | Copies of all such correspondence. | An unresolved infringement claim from a major competitor or a Non-Practicing Entity (NPE). | 5 | |

| VI. Regulatory | Regulatory Exclusivities | What regulatory exclusivities (e.g., NCE, Orphan, Biologic, Pediatric) apply to the target’s products in key markets (US/EU)? | FDA/EMA correspondence; Orange Book/Purple Book listings. | Misunderstanding the type or duration of exclusivity, leading to incorrect market life projections. | 33 |

| Patent Term Extension/SPC | Has the target applied for, or is it eligible for, PTE in the US or SPCs in the EU? What is the calculated extension period? | PTE/SPC applications and calculations; regulatory timelines (IND, NDA, approval dates). | Inaccurate calculation of patent term extension, leading to an overestimation of patent life. | 35 |

Part III: The Core Pillars of Patent Examination: Ownership, Validity, and Freedom to Operate

Section 3.1: Verifying Ownership and Chain of Title: Establishing Uncontestable Rights

The absolute, non-negotiable foundation of patent due diligence is the verification of ownership.1 An acquirer cannot purchase rights that the seller does not unequivocally own.7 A flawed or incomplete chain of title can dramatically devalue a patent portfolio and, in the worst-case scenario, render the core assets of an acquisition worthless. This process involves two primary activities: auditing the chain of title and uncovering any encumbrances.

3.1.1 Auditing the Chain of Title

Under U.S. law, ownership of a patentable invention initially vests with the named inventors.5 For a company to own the patent, those rights must be formally transferred. The diligence process must meticulously trace this transfer.

The first step is to review all relevant agreements to confirm that every inventor—including full-time employees, part-time employees, founders, and independent contractors—has properly assigned their rights to the target company.1 This is a frequent point of failure. Employment or consulting agreements may have ambiguous language, or worse, a formal assignment document may never have been executed.22 The Federal Circuit cases of

Whitewater W. Indus., Ltd. v. Alleshouse and Core Optical Techs., LLC v. Nokia Corp. underscore this risk, as both found that inventions created by employees during their employment were not properly assigned to the employer due to specific contractual language, meaning the ownership remained with the employee.22

The second step is to corroborate these internal documents with public records. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) maintains an online Patent Assignment Search database that allows for a search of recorded title transfers.8 The resulting “Abstract of Title” shows the sequence of recorded conveyances, providing a public record of the chain of title.23 The diligence team must compare this public record with the internal documents to identify any gaps, inconsistencies, or unrecorded transfers.17 While these searches are invaluable, it is important to recognize their limitations; they will not reveal assignments that have been made but not yet recorded with the patent office.17

3.1.2 Uncovering Encumbrances

Beyond confirming ownership, the team must identify any third-party rights or restrictions, known as encumbrances, that could limit the acquirer’s ability to use or transfer the patents. These can include 1:

- Liens and Security Interests: The patents may have been used as collateral for financing. A search of assignment records and Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) filings is necessary to identify any security interests that must be released before or at closing.

- Outbound Licenses: A review of all agreements where the target has licensed its IP to others is crucial to determine if any exclusive rights have been granted that would conflict with the acquirer’s strategic plans.19

- Joint Ownership: This is one of the most significant red flags in an ownership review. Collaborative research agreements with universities or other companies can sometimes result in joint ownership of the resulting patents.24 Under U.S. patent law, each joint owner can independently make, use, sell, and license the patented invention without the consent of, or a duty to account for profits to, the other co-owners.24 This means an acquirer could find itself with a “competitor in the patent”—the co-owner could license the technology to the acquirer’s fiercest rival. For this reason, unresolved joint ownership of a key patent can be a deal-breaker.24

Section 3.2: Assessing Patent Validity and Enforceability: Gauging the Strength of the Shield

Once ownership is confirmed, the focus shifts to the quality and defensibility of the patents themselves. A patent is a valuable asset only if it is valid and enforceable.3 This assessment involves a deep dive into the patent’s substance and the history of its prosecution.

3.2.1 Prior Art Analysis

The core of any validity assessment is a search for “prior art”—the body of public knowledge existing before the invention was made.37 If relevant prior art exists that the patent examiner did not consider, it can be used to challenge the patent’s claims as lacking novelty (under §102 of the Patent Act) or being obvious (under §103).1

A comprehensive prior art search for a pharmaceutical patent is a highly specialized task. It requires a multi-pronged strategy that goes beyond simple keyword searching.39 Effective strategies include:

- Keyword and Text Search: Starting with broad concepts and narrowing down to specific terms.37

- Classification Search: Using systems like the International Patent Classification (IPC) or Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) to search within specific technology fields.39

- Citation Search: Analyzing both “backward” citations (the art cited by the patent) and “forward” citations (the art that cites the patent) to find related documents.39

- Structure and Sequence Search: For chemical and biological inventions, this is essential. For complex biologics like antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), the search must cover not only the final ADC but also its individual components: the antibody (requiring specific protein sequence searches), the linker, and the cytotoxic payload (requiring chemical structure and Markush structure searches).39

This process requires access to and expertise in using professional scientific and patent databases like CAS STNext®, MARPAT®, and Delphion.37

3.2.2 The File Wrapper: Prosecution History Estoppel and Its Implications

The complete record of correspondence between the patent applicant and the patent office during the examination process is known as the “prosecution history” or “file wrapper”.26 This record is a treasure trove of information for a diligence team, as it reveals the arguments and amendments the applicant made to secure the patent.

A critical legal doctrine that arises from this history is prosecution history estoppel (also known as file wrapper estoppel).25 This doctrine prevents a patent owner, during infringement litigation, from using the “doctrine of equivalents” to recapture subject matter that was surrendered during prosecution.25 The doctrine of equivalents allows a patent to be infringed even if a product doesn’t literally match the claim language, as long as it performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way to achieve the same result. However, if the patent owner narrowed a claim to overcome a prior art rejection, they are “estopped” from later arguing that a competitor’s product, which falls within the surrendered territory, is an equivalent.25 Analyzing the file wrapper for such disclaimers is crucial because it can significantly limit the effective scope of the patent’s claims, reducing its value and its power to block competitors.

3.2.3 Post-Grant Challenges: The Impact of IPR and PGR on Patent Value

The America Invents Act of 2011 (AIA) fundamentally changed the patent landscape by creating two powerful administrative trial proceedings at the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB): Inter Partes Review (IPR) and Post-Grant Review (PGR).27 These proceedings provide a faster, less expensive, and often more effective way to challenge the validity of a patent compared to traditional district court litigation.27

- Post-Grant Review (PGR): Can be filed within the first nine months of a patent’s grant. It allows a challenge on nearly any ground of invalidity, including novelty, obviousness, subject matter eligibility (§101), and written description/enablement (§112).27

- Inter Partes Review (IPR): Can be filed after the nine-month PGR window has closed. It is limited to challenges based on novelty and obviousness, and only using prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.27

The high rate of claim cancellation in these PTAB proceedings means that the diligence team must assess the vulnerability of the target’s key patents to an IPR or PGR challenge. A patent that is likely to be invalidated by the PTAB represents a significant, quantifiable risk to the acquirer.28

Table 2: Comparison of Patent Challenge Mechanisms (PGR vs. IPR)

| Feature | Post-Grant Review (PGR) | Inter Partes Review (IPR) |

| Filing Window | Within 9 months of patent grant. | After 9 months from patent grant (or after termination of a PGR). |

| Grounds for Challenge | Broad. Any ground of invalidity under §101 (subject matter), §102 (novelty), §103 (obviousness), and §112 (written description, enablement, indefiniteness). | Narrow. Only §102 (novelty) and §103 (obviousness), based on prior art consisting only of patents and printed publications. |

| Burden of Proof (to institute) | Petitioner must show it is “more likely than not” that at least one challenged claim is unpatentable. | Petitioner must show a “reasonable likelihood” of prevailing on at least one challenged claim. |

| Typical Timeline | 12-18 months from institution to final written decision. | 12-18 months from institution to final written decision. |

| Estoppel Effects | Petitioner is estopped from raising in any future USPTO proceeding or civil action any ground that they “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the PGR. | Petitioner is estopped from raising in any future USPTO proceeding or civil action any ground that they “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the IPR. |

| Strategic Use Case in M&A | Offensive: Challenging a competitor’s newly issued, problematic patent on broad grounds (e.g., subject matter eligibility). Defensive: Assessing risk for a target’s very recently granted “crown jewel” patent. | Offensive: A cost-effective tool to invalidate a competitor’s blocking patent based on strong prior art, clearing the way for FTO. Defensive: Assessing the validity risk of a target’s key patents that are older than 9 months. |

Sources: 27

Section 3.3: Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Ensuring the Right to Commercialize

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is the process of determining whether a company’s proposed commercial product, process, or service can be brought to market without infringing the valid and enforceable patent rights of a third party.1 In pharmaceutical M&A, where the entire value of the deal rests on the ability to sell a drug, a comprehensive FTO analysis is a mandatory and intensely scrutinized part of due diligence.4 An FTO problem can expose the acquirer to costly litigation, injunctions that halt sales, or the need to pay substantial royalties, any of which can destroy the economic rationale for the deal.1

3.3.1 Methodology for a Robust Pharmaceutical FTO Search

A proper FTO analysis is a systematic, multi-step process conducted by experienced patent counsel.31

- Understand the Product: The process begins with a deep dive into the target’s product, identifying all of its key features, including the drug’s chemical structure, formulation, manufacturing process, and all intended methods of use.32 Since products are often still in development, this may be an iterative process where features are “locked” and searched in stages.32

- Design the Search Strategy: The next step is to design search strings to identify potentially relevant third-party patents. This requires a delicate balance between creating a search that is broad enough to not miss any relevant patents, while being narrow enough to avoid being overwhelmed by irrelevant results.32 Effective techniques include limiting the search to specific technology fields, searching for key feature terms directly within the claims of patents, and, if necessary, narrowing the search to key competitors known to be active in the space.32

- Analyze Patent Claims: This is the most critical and nuanced part of the FTO process.31 It involves a meticulous, feature-by-feature comparison of the target’s product against the claims of the patents identified in the search. This legal analysis determines whether there is a potential for infringement.

3.3.2 Analyzing and Categorizing Infringement Risk

Not all identified patents pose the same level of threat. The results of the FTO search should be categorized to help prioritize risk 31:

- High-Risk Patents: These are patents with claims that appear to directly read on or closely match the target’s product or its method of use.

- Medium-Risk Patents: These patents have some overlapping claims, but there may be reasonable non-infringement arguments or potential design-around strategies.

- Low-Risk Patents: These are patents that are only tangentially related and are unlikely to pose a significant threat.

For any patents categorized as high-risk, the analysis does not stop at infringement. The next step is to assess the validity of that high-risk patent. A blocking patent that is likely invalid is not a true threat.31 This creates a powerful feedback loop between FTO and validity analysis. The discovery of a potential FTO risk is no longer just a signal of a potential lawsuit; it is now a signal of a potential IPR petition that could neutralize the threat. The diligence team must therefore assess not just its own vulnerability to infringement, but also the vulnerability of the blocking patent to an invalidity challenge. This transforms FTO diligence from a purely defensive exercise into a more offensive strategic assessment. A deal may proceed even in the face of a clear FTO risk if the team concludes with high confidence that the blocking patent can be successfully invalidated at the PTAB.

3.3.3 The Critical Importance of Geographical Scope in FTO

Patent rights are territorial; a patent granted in the United States provides no protection in Europe, and vice versa.40 Therefore, a comprehensive FTO analysis must be conducted for every jurisdiction where the acquirer intends to develop, manufacture, or sell the product.11 Failing to conduct a global FTO analysis is a common and dangerous pitfall. This geographical dimension has become even more critical in light of increasing geopolitical trade risks and shifting supply chains.12 A product may have perfect FTO in the United States, but if its Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is sourced from a country where its manufacturing process infringes a third-party patent, the entire business is at risk. The FTO analysis must mirror the company’s global operational footprint.

Part IV: Valuation of Pharmaceutical IP Assets

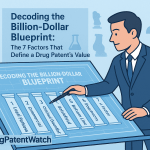

Section 4.1: Methodologies for Valuing Drug Patents

Determining the value of a patent portfolio is a complex undertaking that is both an art and a science, requiring a sophisticated understanding of the market, the technology, and the legal landscape.3 In pharmaceutical M&A, several methodologies are employed to assign a monetary value to these critical intangible assets, with the income-based approach being the most prevalent.

- Income-Based Valuation: This method, which focuses on the future income a patent is expected to generate, is the most widely used in M&A because it provides the clearest picture of an asset’s revenue-generating potential.9

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) / Net Present Value (NPV): This is a foundational model used to value commercial-stage drug companies and assets. It involves projecting all future cash flows (revenues minus costs) associated with a drug over its protected life and then discounting those cash flows back to their present value using a discount rate that reflects the risk of the investment.41

- Risk-Adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV): This is the predominant and most sophisticated valuation technique in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors.41 The rNPV model enhances the standard DCF analysis by explicitly incorporating the high risk of failure inherent in drug development. It adjusts the projected cash flows at each stage by the statistical probability of success (POS) for that stage (e.g., Phase I, Phase II, Phase III, Regulatory Approval). Because the probability of success increases dramatically as a drug moves through clinical trials, its rNPV can jump significantly with positive data. For instance, the rNPV of a hypothetical drug might increase from $45.8 million at Phase I to $312.1 million upon submission of a New Drug Application (NDA).42

- Market-Based Valuation: This approach attempts to value a patent by comparing it to similar patents or IP assets that have recently been sold or licensed in comparable transactions.9 While useful for providing a market benchmark, this method is often difficult to apply in practice due to the unique nature of each patented invention and the general lack of publicly available, directly comparable transaction data.41

- Cost-Based Valuation: This method assesses a patent’s value based on the historical costs incurred to develop it, including all research and development (R&D) expenses, legal fees for patent prosecution, and other related costs.9 While this approach can provide a baseline or “floor” value, it is generally considered the least effective method as it fails to capture the patent’s future market potential or commercial value, which may be vastly different from its development cost.9

- Sum-of-the-Parts (SOTP) Valuation: This methodology is commonly used for biotech companies with a diverse pipeline of multiple drug candidates. In a SOTP analysis, each individual drug or asset in the pipeline is valued separately, typically using the rNPV method. The individual values are then summed up to arrive at a total valuation for the company’s entire portfolio.41

The choice of valuation methodology often reflects the strategic positions of the buyer and seller. An informed buyer, such as a large pharmaceutical company, will almost certainly anchor its valuation in a conservative rNPV model that systematically accounts for development risk.41 In contrast, the seller of an early-stage asset may argue that the static rNPV model fails to capture the “real option” value of managerial flexibility—the ability to expand, pause, or redirect a project based on emerging data. Consequently, sellers often prefer valuation methods like real options analysis, which can yield higher valuations.41 This predictable valuation gap between buyer and seller is a primary driver for the increasing use of creative deal structures, such as earn-outs and contingent value rights (CVRs). These structures effectively bridge the gap by allowing the buyer to pay an upfront price based on its rNPV, while the seller receives additional future payments if and only if the asset achieves the de-risking milestones that the seller’s more optimistic valuation model had prized. This allows a deal to close by deferring the final determination of value until the underlying risks have been resolved.12

Section 4.2: Key Valuation Drivers: Patent Strength, Market Size, and Competitive Landscape

The outputs of any valuation model are only as good as their inputs. The value of a pharmaceutical patent is driven by a confluence of legal, commercial, and scientific factors that must be rigorously assessed during due diligence.

- Patent Strength and Legal Status: The quality, defensibility, and scope of the patent protection are paramount.3 A patent with broad, well-drafted claims that has survived legal challenges is significantly more valuable than one with narrow claims or a history of litigation. The geographic coverage of the patent is also critical; protection in key markets like the US, EU, and Japan is essential.3 A strong “patent wall” of multiple, layered patents can deter generic entry and secure a longer period of market exclusivity, thereby increasing the asset’s value.42

- Market Potential and Revenue Projections: A core input for any income-based valuation is the projected revenue stream from the drug. This requires a detailed analysis of the total addressable market, including the size of the target patient population and the prevalence of the disease.45 The diligence team must also develop realistic forecasts for peak sales, market penetration, and pricing strategy, taking into account reimbursement landscapes in different countries.41

- Competitive Landscape: No drug exists in a vacuum. The valuation must consider the competitive environment, including the efficacy and safety of existing treatments and, crucially, the pipeline of competing drugs under development by other companies.45 A new drug that offers a significant clinical improvement over the current standard of care will command a higher value than one entering a crowded market with little differentiation.

- Research & Development Costs: The high costs associated with bringing a new drug to market, which can exceed $1 billion, are a significant factor in valuation.42 These sunk costs represent the initial investment that the patent-protected revenue stream must recoup for the project to be profitable.45

Section 4.3: The Patent Cliff: Modeling the Financial Impact of Expiration

The “patent cliff” is a term used to describe the sharp and dramatic decline in a drug’s revenue that occurs upon the expiration of its patent protection and the subsequent market entry of lower-priced generic or biosimilar competitors.14 This is a pivotal and unavoidable event in a drug’s lifecycle, and its financial impact is profound.

Upon patent expiration, generic competition typically enters the market at a significant discount, often 70% or more below the branded price.14 This leads to a rapid erosion of the originator’s market share as payers and patients switch to the more affordable alternatives. For blockbuster drugs, this can mean a loss of billions of dollars in annual sales in a very short period. For example, analysts projected that sales of the blockbuster drug Keytruda would decline by 19% in the first year after its patent expiration.14 The industry as a whole is projected to have approximately $300 billion in revenue at risk due to patent expirations in the next few years alone.13

Given these high stakes, a critical task for the diligence and valuation team is to accurately calculate the final expiration date of all relevant patents, including any patent term extensions. This date determines the end of the high-revenue period in the financial model. Miscalculating the remaining patent life, even by a short period, can lead to a significant overvaluation of the asset and can completely undermine the economic basis for an acquisition.4 The valuation model must explicitly account for the patent cliff by forecasting a steep drop-off in revenues and margins in the years immediately following the loss of exclusivity.

Part V: Beyond the Patent: The Regulatory Exclusivity Landscape

Section 5.1: Understanding the Symbiotic Relationship Between Patents and Regulatory Exclusivity

In the pharmaceutical industry, market exclusivity—the period during which a drug is protected from generic or biosimilar competition—is not derived from patents alone. It is the result of a complex and symbiotic relationship between patent rights and a separate system of regulatory exclusivities granted by agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).4

Regulatory exclusivity is a statutory right that prevents the regulatory agency from approving a competing generic or biosimilar application for a specified period, regardless of the patent status of the originator drug.33 These two forms of protection, patents and regulatory exclusivities, run concurrently from the date of a drug’s approval.46 The actual, effective period of market exclusivity for a drug is therefore determined by whichever form of protection lasts longer.46 For this reason, a comprehensive due diligence process must meticulously analyze both the patent landscape and the full scope of applicable regulatory exclusivities in all key markets. Failing to map this dual-layered protection system will lead to an inaccurate assessment of a drug’s commercial runway and, consequently, a flawed valuation.4

Section 5.2: U.S. Exclusivity Deep Dive: Hatch-Waxman, PTE, Biologics, and Orphan Drugs

The United States has the most intricate system of regulatory exclusivities, established primarily by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 and subsequent legislation.

- Hatch-Waxman Act Exclusivities: This landmark legislation created the modern framework for generic drug approval and established key exclusivities for small-molecule drugs.47

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A drug containing an active moiety that has never before been approved by the FDA is granted five years of data exclusivity. During this period, the FDA cannot accept an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) from a generic manufacturer for the first four years (unless it contains a patent challenge).34

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: A three-year period of exclusivity is granted for applications that contain reports of new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) that were essential to the approval. This typically applies to new formulations, new dosage forms, or new indications for a previously approved drug.34

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): A cornerstone of the Hatch-Waxman Act, PTE was created to restore a portion of a patent’s term that was lost while the drug was undergoing the lengthy FDA regulatory review process.47 The calculation, codified at 35 U.S.C. § 156, is complex. It generally restores one-half of the time spent in the clinical testing phase (from IND effective date to NDA submission) and the full time spent in the FDA approval phase (from NDA submission to approval).51 However, the total extension is subject to several important caps: it cannot exceed five years, and the total remaining patent term after approval plus the extension cannot exceed fourteen years.47 Accurately calculating the potential PTE for a target’s key patent is a critical diligence task that requires precise regulatory dates.35

- Biologics Exclusivity: The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA) created an abbreviated approval pathway for biosimilars and established a distinct and highly valuable exclusivity for new biologic products. A pioneer biologic receives 12 years of data exclusivity from the date of its first licensure.46 This is significantly longer than the five years granted to small-molecule NCEs and serves as a powerful “insurance policy” to incentivize innovation in the high-risk biologics space, especially when patent protection may be uncertain or vulnerable to challenge.46

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): The Orphan Drug Act of 1983 provides powerful incentives for the development of drugs for rare diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the United States. A drug that receives an orphan designation for a specific indication is granted seven years of market exclusivity for that indication upon approval.34 During this period, the FDA may not approve another application for the same drug for the same orphan indication. This powerful exclusivity is a major driver of M&A activity in the rare disease sector.53

- Pediatric Exclusivity: To encourage the study of drugs in children, an additional six months of exclusivity can be granted. This six-month period is added to all existing patent and regulatory exclusivity periods for all of the sponsor’s approved formulations of the active moiety, making it a highly valuable incentive.34

The significant difference in exclusivity periods between biologics (12 years) and small molecules (5 years) in the U.S. creates a powerful structural incentive that shapes global R&D investment and M&A strategy. This “exclusivity arbitrage” makes investment in biologic R&D a more financially secure proposition, as the long data exclusivity period provides a robust backstop against potentially weak or challenged patents. Consequently, in an M&A context, large pharmaceutical acquirers looking to de-risk their pipeline acquisitions will often place a strategic premium on biotech targets with promising biologic candidates over those with small-molecule drugs, all else being equal. The due diligence process must therefore not only verify the existence of these exclusivities but also weigh their strategic value in the context of these global regulatory asymmetries.

Section 5.3: European Exclusivity Deep Dive: Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) and Recent Reforms

The European system for extending market protection also relies on a combination of regulatory data protection and a patent extension mechanism.

- Data and Market Protection: The EU provides a harmonized “8+2+1” formula for new drugs. This includes eight years of data exclusivity, during which a generic company cannot reference the originator’s data, followed by two years of market protection, during which a generic application can be reviewed but not approved. An additional one year of market protection can be granted for a significant new therapeutic indication.49 Unlike the U.S., this period is generally harmonized for both small molecules and biologics.

- Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs): The primary mechanism for extending patent life in the European Economic Area (EEA) is the SPC.36 An SPC is a

sui generis IP right that extends the term of a basic patent for an approved pharmaceutical product to compensate for the time lost during regulatory review. An SPC can extend a patent for a maximum of five years.36

- Pediatric Extension: Similar to the U.S., a six-month extension can be added to the SPC term if the product has been tested in children according to an agreed-upon Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP).36

- Recent Reforms and Unitary SPC: In April 2023, the European Commission proposed a major reform to streamline the SPC system. This includes creating a centralized examination procedure and, significantly, introducing a “unitary SPC” that will provide a single, unified extension for the new European Unitary Patent, aiming to reduce costs and improve legal certainty across member states.36

- Manufacturing Waiver: A 2019 regulation introduced an important exception, known as the “SPC manufacturing waiver.” This allows EU-based generic and biosimilar manufacturers to produce an SPC-protected medicine during the certificate’s term, but only for the purpose of exporting it to non-EU markets or for stockpiling in the final six months of the SPC term for a day-one launch in the EU.36 This waiver introduces a competitive nuance that must be considered in global market forecasts.

Section 5.4: Integrating Exclusivity Analysis into Overall Diligence

The diligence team’s ultimate output for this workstream should be a comprehensive timeline for each major global market. This timeline must clearly map out the expiration dates of all relevant patents (including calculated PTE/SPC extensions) alongside the expiration dates of all applicable regulatory exclusivities. This integrated view is the only way to determine the true, effective period of market protection for a drug. This timeline is a critical input for the financial valuation model. Overlooking a form of exclusivity can lead to a significant undervaluation of an asset, while miscalculating a patent expiration date can lead to a catastrophic overvaluation.

Table 3: Major Regulatory Exclusivities in the US & EU

| Exclusivity Type | Jurisdiction | Duration | Applies To | Triggering Event | Key Strategic Implication for M&A |

| New Chemical Entity (NCE) / New Active Substance | US | 5 Years Data Exclusivity | Small-molecule drugs with a new active moiety. | FDA approval of the first NDA for the active moiety. | Standard protection for innovative small molecules. The 5-year clock is a key valuation input. |

| EU | 8 Years Data Exclusivity + 2 Years Market Protection | All new medicinal products (small molecules and biologics). | EMA marketing authorization. | Provides a longer, harmonized baseline protection period in Europe compared to US NCEs. | |

| Biologics Exclusivity | US | 12 Years Data Exclusivity | New biologic products (BLAs). | FDA licensure of the first BLA for the product. | A highly valuable exclusivity that makes biologic assets in the US particularly attractive and less reliant on patent strength. |

| Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) | US | 7 Years Market Exclusivity | Drugs for diseases affecting <200,000 people in the US. | FDA approval for the designated orphan indication. | A major driver of M&A in the rare disease space; provides strong protection for a specific indication. |

| EU | 10 Years Market Exclusivity | Drugs for life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting not more than 5 in 10,000 people in the EU. | EMA marketing authorization for the designated orphan indication. | Even longer exclusivity period than in the US, making EU orphan assets valuable. | |

| Patent Term Extension / Restoration | US (PTE) | Up to 5 Years | Patented products subject to premarket regulatory review. | Calculated based on regulatory review time; added to patent term. | A critical, but complex, calculation to determine the true patent expiry date. Errors can lead to major valuation flaws. |

| EU (SPC) | Up to 5 Years | Patented products subject to premarket regulatory review. | Calculated based on regulatory review time; extends the basic patent. | The European equivalent of PTE; diligence must verify eligibility and duration in each member state. | |

| Pediatric Extension | US | 6 Months | Any drug for which the sponsor conducts requested pediatric studies. | Added to all existing patents and exclusivities for the active moiety. | A valuable “kicker” that can add hundreds of millions in revenue by extending total exclusivity. |

| EU | 6 Months | Any drug with an SPC for which a Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP) is completed. | Added to the term of the SPC. | Similar to the US, a valuable incentive that extends the SPC term and overall market protection. |

Sources: 33

Part VI: Contractual Entanglements: Analyzing Licensing and Collaboration Agreements

Section 6.1: Dissecting In-Licensing and Out-Licensing Agreements

A pharmaceutical company’s intellectual property rights are often defined not just by the patents it owns, but by a complex web of contracts that govern how it can use its own IP and the IP of others. A thorough due diligence process must therefore include a meticulous review of all material IP-related agreements, as these documents can contain critical rights, restrictions, and obligations that will pass to the acquirer.16 These agreements fall into two main categories.

- In-Licensing Agreements: These are contracts where the target company has acquired the rights to use intellectual property owned by a third party (e.g., a university, another biotech company). For these agreements, the central diligence question is whether the target has secured all the necessary rights to develop and commercialize its products, and, crucially, whether those rights are transferable to the acquirer upon the closing of the M&A transaction.19 The value of the target can be severely diminished if a critical in-licensed patent cannot be transferred to the new owner.

- Out-Licensing Agreements: These are contracts where the target company has granted rights to its own intellectual property to a third party. Here, the diligence team must determine precisely what rights have been given away.19 For example, has the target granted an exclusive license in a key geographical territory that the acquirer was planning to enter? Has it granted rights in a field of use that the acquirer intended to explore? Such grants can place significant constraints on the acquirer’s post-closing strategic and commercial plans.28

Section 6.2: Red Flags in Contractual Language: Change of Control, Grant-Backs, and Sublicensing Rights

The review of these agreements must go beyond a simple summary and focus on specific contractual clauses that pose the greatest risk in an M&A context.

- Assignment and Change of Control: This is arguably the most critical provision to scrutinize in any license agreement during M&A due diligence.17 These clauses govern whether the agreement can be assigned to another party or what happens in the event of a change in ownership of the licensee. A poorly drafted clause could mean that the M&A transaction itself constitutes a breach of the agreement, allowing the licensor to terminate the license or demand consent.17 The risk associated with these clauses is not merely legal; it is deeply strategic. If the target has in-licensed a critical piece of technology from a company that is a direct competitor to the acquirer, that competitor-licensor can use the change of control clause as a weapon. It can refuse to grant consent, thereby blocking the acquisition, or it can use its consent as leverage to extract significant concessions, such as higher royalty rates or a cross-license to the acquirer’s own valuable IP. Therefore, the diligence team must not only identify these clauses but also analyze the identity and competitive position of the counterparty to accurately assess the strategic risk.

- Scope of the License: The team must carefully analyze the definitions of “Licensed IP,” “Field of Use,” and “Territory” to understand the precise boundaries of the rights that have been granted or received.56 Ambiguous language can lead to future disputes over the scope of the agreement.

- Exclusivity: The nature of the license—whether it is exclusive, co-exclusive, or non-exclusive—is a key determinant of value. An exclusive in-license for a core technology is a highly valuable asset. Conversely, an exclusive out-license in a major market can be a major liability for an acquirer with global ambitions.56

- Grant-Back Clauses: Acquirers must be wary of “grant-back” provisions in in-licensing agreements. These clauses may require the licensee (and thus the future acquirer) to license or even assign back to the original licensor any improvements or new inventions it develops based on the licensed technology.17 This can result in the acquirer inadvertently giving away valuable, self-developed IP.

- Sublicensing Rights: The agreement should be reviewed to determine if the target has the right to grant sublicenses. The ability to sublicense can be critical for operational flexibility, allowing the company to partner with others for manufacturing or distribution in certain territories. If the target has already granted sublicenses, those derivative agreements must also be reviewed.56

- Financial Terms: All financial provisions, including upfront payments, milestone payments, and royalty rates, must be reviewed to understand the economic burden of the agreement. The team should pay special attention to “royalty stacking” provisions, which can cap the total royalty burden if multiple licenses are needed for a single product, as this can significantly impact profitability.

Section 6.3: Joint Development and Research Agreements: Unraveling Shared IP Rights

In the collaborative world of pharmaceutical R&D, it is common for companies to enter into joint development or sponsored research agreements with universities, research institutions, or other companies.4 These agreements are a frequent source of complex IP ownership issues and must be scrutinized with extreme care.

The diligence team must examine these agreements to determine who owns the intellectual property that arises from the collaboration. The default legal rules for joint inventorship can be unfavorable, and if the agreement is silent or ambiguous on IP ownership, it can result in joint ownership of the resulting patents.24 As discussed previously, joint ownership is a significant red flag because it can create a “competitor in the patent” who can operate independently.24 The diligence team must also look for any rights retained by funding entities, such as government agencies or academic institutions. These entities often retain “march-in rights” or a non-exclusive license for research purposes, which can encumber the IP and limit the acquirer’s control.17

Table 4: Critical Clauses in IP License Agreements for M&A

| Clause | What to Look For (Key Language) | Risk if Licensee (In-License) | Risk if Licensor (Out-License) | M&A Red Flag Level |

| Change of Control / Assignment | “This agreement may not be assigned… without the prior written consent of the other party.” “A change of control of Licensee shall be deemed an assignment.” | HIGH. The transaction could trigger termination of a critical license or require consent from a potentially hostile licensor (e.g., a competitor). | Medium. Acquirer loses control over who can ultimately practice the technology if the licensee is acquired by a competitor. | High |

| Scope of Grant (Field/Territory) | Definitions of “Licensed Technology,” “Field of Use,” “Territory.” | Medium. A narrow grant may not cover the acquirer’s intended product expansion or new indications, requiring renegotiation. | High. A broad grant may have given away rights in a market or field that the acquirer intended to pursue, creating a direct business conflict. | High |

| Exclusivity | “Exclusive,” “sole,” “co-exclusive,” “non-exclusive.” | Low (if exclusive). An exclusive license is a valuable asset. High (if non-exclusive). A non-exclusive license means competitors may have access to the same technology. | High (if exclusive). An exclusive license prevents the acquirer from using the IP or licensing it to others in that field/territory. | High |

| Sublicensing | “Licensee shall have the right to grant sublicenses…” | Medium. Lack of sublicensing rights can restrict operational flexibility (e.g., using contract manufacturers or regional distribution partners). | Medium. Broad sublicensing rights granted to the licensee can dilute the acquirer’s control over its technology and brand. | Medium |

| Grant-Backs | “Licensee hereby grants to Licensor a… license to any Improvements.” | High. The acquirer could be forced to license or assign its own future innovations back to the licensor, potentially on unfavorable terms. | Low. This is a favorable clause for the licensor/acquirer, ensuring access to improvements made by the licensee. | High |

| Royalty Stacking | “In the event Licensee is required to pay royalties to a third party… the royalty rate payable hereunder shall be reduced…” | High (if no clause). Without this clause, the acquirer may face an unsustainable total royalty burden if multiple licenses are needed for one product. | Medium. This clause can reduce the royalty stream payable to the acquirer if the licensee needs other third-party technology. | Medium |

| Termination | “This agreement may be terminated by Licensor upon…” | High. A termination clause for convenience or for minor breaches could put a critical asset at risk post-acquisition. | Low. Provides the acquirer with flexibility to terminate underperforming licenses. | High |

Sources: 17

Part VII: Translating Findings into Deal Strategy: Risk Mitigation and Post-Closing Integration

Section 7.1: Leveraging Diligence Findings in Negotiations: Price Adjustments, Reps & Warranties, and Indemnification

The due diligence report is not an academic exercise; it is a powerful negotiation tool that directly informs the structure and terms of the M&A agreement.1 The findings of the diligence process provide the acquirer with the leverage needed to mitigate identified risks and allocate them appropriately between the buyer and seller.

- Purchase Price Adjustments: If the diligence process uncovers significant risks—such as a weak patent portfolio, a serious freedom-to-operate issue, or an impending patent expiration—the acquirer can use this information to argue for a reduction in the purchase price.20 The valuation models can be adjusted to quantify the financial impact of these risks, providing a data-driven basis for the negotiation.

- Representations and Warranties: The acquirer should negotiate for robust and specific representations and warranties from the seller regarding the intellectual property. These are contractual promises made by the seller about the state of the IP assets. Key IP reps and warranties should cover 10:

- The seller’s sole and unencumbered ownership of the patents.

- The validity and enforceability of the key patents.

- The fact that the operation of the business does not infringe any third-party IP rights.

- The disclosure of all material IP-related litigation and disputes.

A savvy buyer will push to limit or eliminate any “knowledge qualifiers” (e.g., “to the seller’s knowledge”), which weaken these promises.10 - Indemnification: To protect against losses from pre-existing liabilities that may only come to light after the deal closes, the acquirer must secure strong indemnification clauses.1 These clauses obligate the seller to compensate the buyer for specific types of damages, such as those arising from a breach of the IP representations and warranties or from a pre-closing infringement claim. To give these clauses teeth, a portion of the purchase price is often held back in an escrow account for a specified period to serve as a ready source of funds to cover any potential indemnification claims.1

Section 7.2: Advanced Risk Mitigation: Earn-Outs, Options, and R&W Insurance

For acquisitions involving early-stage or particularly high-risk pharmaceutical assets, standard contractual protections may not be sufficient. In these cases, acquirers are increasingly turning to more sophisticated deal structures to mitigate risk.12

- Earn-Outs (Contingent Consideration): This structure makes a significant portion of the total purchase price contingent upon the target asset achieving specific, pre-defined future milestones.44 For an R&D-stage drug, these milestones could be successful completion of a Phase III trial, receipt of FDA approval, or hitting certain sales targets post-launch. Earn-outs are an effective way to bridge valuation gaps and reduce the buyer’s upfront risk, as the full price is only paid if the asset proves its value.44

- Option Structures: An option agreement allows a buyer to secure the right, but not the obligation, to acquire an asset or a company at a pre-negotiated price at some point in the future.44 A large pharmaceutical company might pay a smaller biotech for an option to acquire its lead drug candidate after it has been de-risked by generating positive Phase II clinical data. This allows the buyer to secure access to a promising asset while deferring the bulk of the investment until a key risk inflection point has passed.44

- Representation & Warranty Insurance (RWI): RWI is an insurance policy that the buyer or seller can purchase to cover losses arising from a breach of the seller’s representations and warranties in the M&A agreement.44 Historically considered difficult to obtain for high-risk life sciences deals, RWI is now increasingly viable and provides a powerful risk-shifting mechanism. It allows the seller to achieve a “clean exit” with limited post-closing liability, while providing the buyer with a more certain path to recovery (from a creditworthy insurer) than chasing the seller for indemnification.44

The growing use of RWI in life sciences M&A is fundamentally altering the negotiation landscape. By transferring risk to a third-party insurer, it can break deadlocks over the size and duration of the seller’s indemnification obligations. However, this shift introduces a new dynamic. The insurer’s own counsel will conduct a rigorous “bring-down” diligence, heavily scrutinizing the buyer’s original diligence report as a key underwriting document. A superficial or poorly documented diligence report will result in a policy with significant exclusions, higher premiums, or an outright refusal by the insurer to provide coverage. Therefore, while RWI appears to de-risk the transaction for the parties involved, it actually places an even greater premium on the quality, thoroughness, and documentation of the buyer’s due diligence process. The diligence report is no longer just an internal tool; it is a critical document for securing the very insurance that may be enabling the deal.

Section 7.3: The Post-Closing Mandate: A Roadmap for IP Integration

The work of due diligence does not end when the deal closes. The findings of the diligence report should form the basis of a comprehensive post-closing integration plan to ensure that the full value of the acquired IP is realized.1

Key elements of this plan include:

- IP Asset Transfer and Recordation: The legal team must ensure that all patents and other registered IP are properly reassigned to the acquirer and that these assignments are recorded in a timely manner in the patent offices of all relevant jurisdictions.1

- License Management: The business and legal teams must address any problematic licenses identified during diligence. This may involve terminating certain agreements, renegotiating unfavorable terms, or managing the process of obtaining any required post-closing consents.1

- Strategic Portfolio Alignment: The acquired patent portfolio must be integrated with the buyer’s existing IP assets. This involves harmonizing patent filing, prosecution, and enforcement strategies to eliminate redundancies, identify synergies, and maximize the value of the combined portfolio.9 This strategic alignment is crucial for leveraging the combined technologies to create new products, enhance existing ones, and open up new market opportunities.9

Part VIII: Lessons from the Field: In-Depth Case Studies in Pharmaceutical M&A

Theoretical frameworks for due diligence are best understood through the lens of real-world transactions. The following case studies illustrate the critical impact of patent and IP-related issues on the outcomes of major pharmaceutical M&A deals, providing powerful lessons on the value of a thorough and strategic diligence process.

Section 8.1: Gilead/Kite ($11.9B, 2017): The Value and Risk of a Foundational CAR-T Patent Portfolio

- Context: In 2017, Gilead Sciences executed a landmark $11.9 billion acquisition of Kite Pharma, a move designed to establish Gilead as an immediate leader in the revolutionary and rapidly emerging field of CAR-T (chimeric antigen receptor T-cell) therapy.57 The central asset of the acquisition was Kite’s lead product candidate, axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel), which would later be approved as Yescarta®.58

- Diligence Focus: The entire valuation of the deal was predicated on the strength and durability of Kite’s intellectual property. The diligence process would have been intensely focused on Kite’s patent portfolio, which included an exclusive license to the foundational Eshhar ‘465 patent, considered a pioneering asset in the CAR-T space.60 Key diligence tasks would have included assessing the validity and enforceability of this and other core patents, as well as conducting a comprehensive FTO analysis in what was already a crowded and notoriously litigious field, with multiple players developing similar CAR-T therapies.

- Post-Acquisition Outcome: Shortly after the acquisition, Gilead was plunged into a high-stakes patent war. Juno Therapeutics (which was subsequently acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb) filed a lawsuit alleging that Kite’s Yescarta infringed a patent owned by Juno and the Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research. In 2019, a jury found that Kite had willfully infringed the patent, and Gilead was hit with a staggering $1.2 billion judgment.61 However, in a dramatic reversal in August 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit overturned the verdict, ruling that Juno’s patent was invalid because its written description was not specific enough to meet the requirements of patent law.61

- Strategic Lesson: The Gilead/Kite saga is a stark illustration of the immense litigation risk inherent in acquiring companies on the cutting edge of science. It demonstrates that even with a strong, internally-vetted patent portfolio, an acquirer can inherit billion-dollar lawsuits from competitors. The case underscores that due diligence must extend beyond analyzing the target’s own patents to include a thorough assessment of the patent portfolios of key competitors. Furthermore, it highlights the critical importance of all aspects of validity analysis; in this instance, it was not prior art but a failure to meet the written description requirement that ultimately decided the case and saved Gilead over a billion dollars.

Section 8.2: Merck/Cubist ($8.4B, 2014): The Peril of a Post-Announcement Patent Invalidation

- Context: In December 2014, Merck & Co. announced its intention to acquire Cubist Pharmaceuticals for $8.4 billion.62 The primary driver of the deal was Cubist’s blockbuster antibiotic, Cubicin (daptomycin), a key weapon against drug-resistant “superbugs.” The acquisition also included a promising pipeline of other anti-infective drugs.64

- Diligence Focus: The financial rationale for the acquisition was heavily dependent on the projected revenue stream from Cubicin, which in turn depended on its patent protection. Cubist was embroiled in patent litigation with generic manufacturer Hospira, and the key diligence task would have been to scrutinize the strength of the five patents protecting Cubicin from generic competition, which were set to expire between 2016 and 2020.62

- Post-Acquisition Outcome: In a stunning turn of events, on the very same day that Merck announced the acquisition, a U.S. District Court in Delaware handed down its ruling in the Hospira litigation. The court invalidated four of the five key Cubicin patents, upholding only a single patent that was set to expire in June 2016.62 This decision effectively moved the “patent cliff” for Cubist’s main revenue generator forward by several years. Despite this massive blow to the deal’s valuation—with analysts estimating that Merck had overpaid by $2 billion to $3 billion—Merck proceeded with the acquisition.65 The company stated that it had modeled for this potential outcome and that the deal remained strategically sound due to the long-term value of Cubist’s pipeline.63

- Strategic Lesson: The Merck/Cubist case is a classic cautionary tale about the timing and impact of litigation risk. It demonstrates that a key patent’s value can be erased in an instant, dramatically altering a deal’s financial calculus. The case highlights the absolute necessity of conducting deep, scenario-based valuation modeling that accounts for various potential litigation outcomes. It also underscores the importance of having a clear strategic rationale for an acquisition that extends beyond the patent life of a single flagship product.

Section 8.3: AbbVie/Pharmacyclics ($21B, 2015): Analyzing the “Patent Wall” Strategy for Imbruvica

- Context: In 2015, AbbVie acquired Pharmacyclics in a massive $21 billion deal, with the crown jewel being the blockbuster blood cancer drug Imbruvica (ibrutinib).67

- Diligence Focus: For an asset of this value, the due diligence would have required an exhaustive analysis of the breadth, depth, and durability of Imbruvica’s patent protection. This would go far beyond just the core composition of matter patent to encompass the entire portfolio strategy.

- Post-Acquisition Outcome: AbbVie acquired an asset protected by one of the industry’s most formidable “patent walls” or “patent thickets.” An analysis by the non-profit group I-MAK revealed that Imbruvica is protected by at least 165 patent applications, with 88 patents granted to date, extending its commercial exclusivity out to 2036.69 A majority of these patent applications (55%) were filed

after Imbruvica was first approved by the FDA, covering not the core molecule itself, but secondary aspects like new methods of use, different formulations, and manufacturing processes.69 This strategy has been described as a “drip-feed” of patenting designed to systematically delay generic competition for as long as possible.69 - Strategic Lesson: This case illustrates an advanced, and highly controversial, IP lifecycle management strategy. For an acquirer like AbbVie, this patent thicket represented a tremendously valuable and durable asset, capable of protecting a multi-billion dollar revenue stream for decades. However, such strategies also attract significant legal and political risk. AbbVie’s patenting practices for both Imbruvica and Humira have been the subject of intense scrutiny, including U.S. congressional investigations and criticism for contributing to high drug prices.70 The diligence lesson is twofold: first, it is essential to understand and value the entire patent portfolio, not just the primary patent. Second, the diligence must assess not only the legal strength of the patent wall but also the associated reputational, political, and antitrust risks that come with enforcing it.

Section 8.4: Boston Scientific/Guidant (2006): A Cautionary Tale of Inherited Product Liability

- Context: While this is a medical device transaction, the 2006 acquisition of Guidant by Boston Scientific offers a powerful and universally applicable lesson on the necessary scope of M&A due diligence. Guidant was a major manufacturer of implantable cardiac defibrillators.72

- Diligence Focus: While patent and IP diligence would have been a component of the process, the critical failure appears to have been in the silos of operational, quality, and regulatory diligence.