Introduction: The High-Stakes Game of Pharma Investing

Welcome to the world of pharmaceutical investment, a domain where the stakes are stratospherically high, and the rewards can be life-changing—not just for investors, but for humanity itself. In this arena, fortunes are made and lost not on quarterly earnings alone, but on the outcome of a Phase III clinical trial, a surprise regulatory decision, or the subtle wording of a single patent claim. For decades, investors have relied on a traditional toolkit: financial statements, management interviews, and clinical trial pipelines. While essential, these tools only show you the visible part of the iceberg. What if you could see what lies beneath the surface? What if you could analyze the very genetic code of a company’s future revenue?

This is the power of leveraging drug patent data. It’s about shifting your perspective from rearview mirror analysis to predictive, forward-looking intelligence. In the intricate dance of drug development, a patent is not merely a legal document; it is a declaration of invention, a map of a company’s strategic intent, and a timer counting down to a moment of profound market disruption.

Beyond the Balance Sheet: Why Patent Data is the New Gold Standard

A company’s balance sheet tells you its financial health today. Its clinical pipeline tells you what it hopes to achieve tomorrow. But its patent portfolio tells you what it owns—the defensible, revenue-generating intellectual property (IP) that underpins its entire valuation. In an industry where the cost to bring a single drug to market can exceed $2 billion, protecting that investment is paramount [1]. The patent is the shield that allows a company to recoup its massive R&D expenditure.

For the savvy investor, this data is a goldmine. It allows you to:

- Identify undervalued companies with powerful, overlooked patent portfolios.

- De-risk investments by conducting thorough IP due diligence before an M&A or venture financing.

- Predict market-shaking events like the “patent cliff” with remarkable accuracy.

- Map the competitive landscape to see who is truly leading innovation in a specific therapeutic area.

This isn’t just about counting patents. It’s about understanding their quality, their scope, their strategic positioning, and their vulnerabilities. It’s about learning to read the tea leaves of innovation long before the results are announced in a press release.

The Core Premise: Turning Intellectual Property into Market Intelligence

Think of a pharmaceutical company as an architect designing a skyscraper. The clinical trial results are the glossy marketing brochures showing what the finished building will look like. The financial reports are the budget and accounting ledgers. The patent portfolio? That’s the detailed architectural blueprint. It shows the foundation, the structural supports, the unique design elements, and crucially, where potential weaknesses might lie.

By learning to read these blueprints, you move from being a passive observer to an active analyst. You can assess the strength of the foundation (the core composition of matter patent), understand the plans for future additions (method-of-use and formulation patents), and even see where competitors might be able to build a rival structure right next door (freedom-to-operate analysis). This guide is designed to hand you the tools and the framework to become that architecturally-minded investor.

Who This Guide Is For: Investors, Strategists, and Innovators

This comprehensive analysis is for the discerning professional who understands that in the information age, an edge comes from superior data and superior analysis. Whether you are:

- A Venture Capitalist scouting for the next biotech unicorn.

- An M&A Executive tasked with identifying and valuing acquisition targets.

- A Hedge Fund Manager looking to make informed bets on both innovator and generic pharmaceutical stocks.

- A Business Development Leader within a pharma company seeking to license-in new assets or understand the competitive IP landscape.

- A Patent Attorney or IP Strategist aiming to translate legal complexities into business value for your clients.

…this guide will provide you with a systematic framework for integrating patent intelligence into your strategic decision-making process. We will journey from the fundamentals of the patent ecosystem to advanced analytical techniques, using real-world case studies to illuminate the path. Let’s begin decoding the blueprint.

The Bedrock of Innovation: Understanding the Pharmaceutical Patent Ecosystem

Before we can leverage patent data, we must first speak its language. The pharmaceutical patent ecosystem is a complex web of legal statutes, regulatory frameworks, and scientific nuances. A superficial understanding can be dangerous, leading to flawed assumptions and costly mistakes. A deep understanding, however, is the foundation upon which all successful IP-driven investment strategies are built.

What is a Drug Patent? More Than Just a Monopoly

At its core, a patent grants its owner the exclusive right to prevent others from making, using, selling, or importing a claimed invention for a limited period—typically 20 years from the earliest filing date. It’s a societal bargain: in exchange for publicly disclosing the details of an invention, the inventor receives a temporary monopoly to encourage and reward innovation. In the pharmaceutical world, this monopoly is not a single, monolithic entity. It’s a carefully constructed fortress built with different types of patents, each serving a distinct strategic purpose.

H4: Composition of Matter Patents: The Crown Jewels

This is the most powerful type of drug patent. It covers the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself—the unique molecular structure that produces the therapeutic effect. Think of atorvastatin (Lipitor) or sildenafil (Viagra); the patents on these specific molecules were the bedrock of their blockbuster status.

Why are they the crown jewels? Because a valid composition of matter patent effectively blocks any competitor from selling the same drug for any use, regardless of how they make it or formulate it. For an investor, identifying a company with a robust, early-stage composition of matter patent on a promising new chemical entity (NCE) is like finding a map to buried treasure. The strength and remaining term of this single patent are often the most significant drivers of a small biotech’s valuation.

H4: Method-of-Use and Formulation Patents: The Life-Cycle Extenders

What happens when the crown jewel patent is nearing its expiration? The strategic game shifts to life-cycle management (LCM). Companies build a “thicket” or “picket fence” of secondary patents around their core product.

- Method-of-Use Patents: These cover a specific method of using the drug to treat a particular disease. For example, a company might first patent a drug for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Years later, they might discover it’s also effective for psoriasis and file a new method-of-use patent for that indication. This can block a generic competitor from marketing their version for the new use, even after the original composition of matter patent has expired.

- Formulation Patents: These patents don’t cover the drug itself, but rather the specific delivery mechanism or composition. This could be an extended-release version, a new injectable form, a combination product with another drug, or a specific set of inactive ingredients (excipients) that improve stability or bioavailability. These patents can be surprisingly effective at preserving market share, as they may force generics to use less convenient or less effective formulations.

For investors, analyzing a company’s LCM patent strategy is crucial for predicting the steepness of its post-expiration revenue decline—the infamous “patent cliff.” A company with a weak secondary patent portfolio will see its revenues plummet. A company with a strong one, like AbbVie with Humira, can fend off competition for years.

H4: Process Patents: The Manufacturing Moat

Process patents cover a specific method of manufacturing the drug. While generally considered less powerful than composition of matter patents—as a competitor could potentially invent a different, non-infringing manufacturing process—they are critically important for biologics.

Biologics are large, complex molecules (like antibodies) produced in living systems. The manufacturing process (the “process”) is inextricably linked to the final product (the “product”). It is incredibly difficult to replicate a biologic exactly, which is why we have “biosimilars” instead of “generics.” A strong portfolio of process patents can create a formidable moat around a biologic drug, making it much harder and more expensive for a biosimilar competitor to enter the market.

The Global Patent Landscape: A Patchwork of Regulations

There is no such thing as a “worldwide patent.” Patents are territorial rights, meaning they must be filed and granted in each country or region where protection is sought. For pharmaceutical investors, understanding the nuances of the major markets is non-negotiable.

H4: The United States: The FDA Orange Book and the Hatch-Waxman Act

The U.S. is the largest pharmaceutical market in the world, and its patent system is unique. The key framework for small-molecule drugs is the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. This act created the modern generic drug industry while also providing incentives for innovator companies.

Its central feature is the “Orange Book” (officially, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations). When an innovator company gets a new drug approved, it must list the patents that cover the drug, its formulation, or its method of use in the Orange Book.

When a generic company wants to market a version of the drug, it files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). In this ANDA, it must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book. The most important of these is the “Paragraph IV” (PIV) certification, where the generic company claims that the innovator’s patent is either invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.

A PIV certification is an act of war. It automatically triggers a patent infringement lawsuit from the innovator. This litigation is the crucible where patent strength is tested. For investors, tracking Orange Book listings, PIV filings, and the subsequent litigation is a direct window into the timing of generic competition for billions of dollars in revenue.

H4: The Europe: The European Patent Office (EPO) and Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs)

In Europe, companies can file a single patent application with the European Patent Office (EPO), which, if granted, can be validated in over 40 member and extension states. This simplifies the application process, but enforcement remains a country-by-country affair (though the new Unified Patent Court is changing this).

A key European-specific concept is the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC). Recognizing that much of a patent’s 20-year term is consumed by lengthy clinical trials and regulatory review, the SPC system provides a mechanism to extend the effective patent life for a drug. An SPC can add up to five years of protection beyond the patent’s expiration, followed by a potential additional six-month pediatric extension. For investors valuing a drug’s European revenue stream, correctly calculating the SPC-adjusted expiration date is absolutely critical.

H4: Other Key Markets: Japan, China, and Emerging Economies

Beyond the US and EU, other markets have their own unique systems. Japan has its own patent linkage system, while China, now the world’s second-largest pharma market, has been rapidly strengthening its IP laws to encourage innovation. Brazil, India, and other emerging economies present both vast opportunities and unique challenges, including different standards for patentability and enforcement. An investor with a global outlook must analyze the patent family—the collection of corresponding patents filed in different countries—to truly understand a drug’s worldwide revenue potential and risks.

The Patent Lifecycle: From Filing to Expiration and Beyond

Understanding the key dates in a patent’s life is fundamental to valuation.

H4: The Priority Date: Staking the Claim

This is the most important date. It is the earliest filing date for a particular invention (often from a provisional application). The 20-year patent term is typically calculated from this date. When you see a company touting a newly issued patent, the savvy investor immediately asks, “What’s the priority date?” A patent that took ten years to issue may only have ten years of life left.

H4: Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE)

These are two critical mechanisms in the U.S. that can extend a patent’s life beyond the standard 20 years.

- Patent Term Adjustment (PTA): This compensates the patent owner for delays caused by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) during the examination process. It’s a complex calculation, but it can add months or even years to a patent’s term.

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): This is the U.S. counterpart to Europe’s SPC. It compensates for the time a drug spends in clinical trials and FDA review. Up to five years of term can be restored, but the total effective patent life cannot exceed 14 years from the drug’s approval date.

These adjustments are not automatic and can be challenged. For an investor, verifying the correct, fully-adjusted expiration date of a key patent can mean the difference between projecting an extra year of monopoly revenue (worth billions for a blockbuster) or missing a looming patent cliff.

Sourcing and Verifying Patent Data: The Investigator’s Toolkit

Having established the “what” and “why” of the patent ecosystem, we now turn to the “how.” Where do you find this mission-critical data, and more importantly, how can you trust it? Accessing and interpreting patent information is both an art and a science. It requires knowing where to look, what to look for, and how to connect the dots between disparate sources of information.

Primary Sources: Going Straight to the Patent Offices

For the purest, most direct information, the national and regional patent office databases are the ultimate source of truth. They contain the full text of patent applications and granted patents, along with their legal status, history (the “file wrapper”), and ownership information.

H4: USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office)

The USPTO’s public search facilities (like Patent Public Search) are the gateway to all U.S. patents and applications. Here you can find:

- The full patent text, including the all-important “claims” that define the legal scope of the invention.

- The “prosecution history,” which is a record of all communications between the applicant and the patent examiner. This can reveal arguments and amendments made to get the patent granted, which can later become crucial in litigation.

- Assignments, which show who currently owns the patent—essential for tracking M&A activity.

While comprehensive, using the USPTO database directly can be cumbersome for strategic analysis. It’s like trying to drink from a firehose; the information is all there, but it’s not structured for easy business intelligence consumption.

H4: EPO (European Patent Office)

The EPO’s Espacenet database is another invaluable free resource. It’s particularly powerful because it provides access to over 140 million patent documents from around the world, not just Europe. It’s an excellent tool for researching patent “families”—finding all the international counterparts to a single invention. This is vital for assessing a company’s global protection strategy.

H4: WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization)

WIPO administers the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), an international system that allows inventors to file a single “international” application to start the process of seeking patent protection in over 150 countries. WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE database is the repository for all of these published PCT applications. Monitoring PCT filings is a fantastic way to get an early look at a company’s R&D pipeline, often 18 months after their initial priority filing and long before they might disclose the program in an investor presentation.

Curated Databases: The Power of Aggregation and Analytics

While primary sources are authoritative, they are not user-friendly for the investor. The real power comes from curated databases that aggregate this raw data and link it to other critical information, such as regulatory approvals, clinical trials, and litigation.

H4: The FDA’s Orange Book: The Bible for Small Molecule Drugs in the US

We’ve mentioned it before, but its importance cannot be overstated. The Orange Book is the definitive link between a specific approved drug product and the patents that protect it. It is the battleground for Hatch-Waxman litigation. For an investor, the Orange Book database provides answers to critical questions:

- Which patents does the innovator believe cover its drug?

- What are the expiration dates of those patents (including PTEs)?

- Is there any period of market exclusivity separate from the patents?

- Have any generic companies filed a Paragraph IV challenge, signaling impending litigation and competition?

H4: The FDA’s Purple Book: The Emerging Guide for Biologics

The counterpart to the Orange Book for biologics is the “Purple Book.” It lists all FDA-licensed biological products, including their approval date and whether they have been determined to be biosimilar to or interchangeable with a reference product. Crucially, under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), the Purple Book also contains a database of patents that may be subject to the complex BPCIA litigation process, often called the “patent dance.” As the biosimilar market matures, the Purple Book will become an increasingly vital resource for investors in the biologics space.

H4: Commercial Intelligence Platforms: The Role of Services like DrugPatentWatch

This is where the rubber meets the road for most professional investors. Sifting through patent office databases and cross-referencing them with FDA information is incredibly time-consuming and requires specialized expertise. This is the void filled by commercial intelligence platforms.

Services like DrugPatentWatch are designed specifically for this purpose. They do the heavy lifting of aggregating data from the USPTO, FDA (Orange and Purple Books), international patent offices, clinical trial registries, and court dockets. But they go much further than simple aggregation. They curate and structure this data to provide direct, actionable business intelligence. An investor using such a platform can, in minutes:

- Pull up a complete, verified patent and exclusivity profile for any drug.

- See accurately calculated, fully adjusted patent expiration dates, including PTA and PTE.

- Receive alerts on new patent listings, Paragraph IV filings, or the initiation of patent litigation.

- Analyze a company’s entire patent portfolio or screen for opportunities based on specific criteria (e.g., “all blockbuster drugs with a key patent expiring in the next 3 years”).

These platforms transform raw, disparate data points into a coherent strategic picture, saving hundreds of hours of manual research and, more importantly, reducing the risk of making a decision based on incomplete or inaccurate information. They are the professional investor’s shortcut to decision-grade intelligence.

The Critical Step of Data Verification: Avoiding Costly Errors

Whether you use primary sources or a commercial platform, a healthy dose of skepticism is essential. Patent data is complex and dynamic. Ownership can change, patents can be invalidated in court, and expiration dates can be adjusted. A single wrong date can throw off a valuation model by hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars.

“In the pharmaceutical industry, intellectual property is not just an asset; it is the cornerstone of value creation. A comprehensive analysis by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development found that the capitalized pre-launch R&D cost per new prescription drug approval is estimated at $2.6 billion. The patent system is the primary mechanism that enables companies to have a chance at recouping this massive investment.”— Based on data from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development [1]

Verification involves cross-referencing information from multiple sources. If analyzing a U.S. drug, check the patent’s expiration in the Orange Book, then cross-reference it with the USPTO’s calculation of PTA, and check court dockets for any ongoing litigation that might challenge the patent’s validity. For sophisticated investors, this rigorous verification is not optional; it is a fundamental part of IP due diligence.

The Strategic Investor’s Playbook: Key Analyses Using Patent Data

With a firm grasp of the patent ecosystem and access to reliable data, we can now move to strategy. How do we weaponize this information to generate alpha? This section outlines four core investment “plays” that leverage patent data to uncover opportunities and mitigate risks that are often invisible to the broader market.

Play #1: Identifying Undervalued Innovators and “Stealth” Companies

The public markets are reasonably efficient at pricing companies based on known information, like reported clinical trial results. The inefficiency—and thus the opportunity—often lies in the market’s inability to properly assess the quality and strategic value of a company’s underlying intellectual property. This is particularly true for early-stage and mid-cap biotech companies.

H4: Analyzing Patent Portfolio Strength and Breadth

Don’t just count patents; weigh them. A single, robust composition of matter patent on a novel target in a major disease area is worth more than a hundred narrow formulation patents on a me-too drug. When evaluating a company, ask these questions:

- What is the core protection? Do they have a granted composition of matter patent in key markets (US, EU, Japan, China)? If not, what is the status of the application?

- How broad are the claims? Do the patent claims cover just one specific molecule, or a broad class of related molecules, creating a “blocking” position that prevents competitors from designing around it?

- What is the global strategy? Has the company filed corresponding patents in all major commercial markets, or are there significant geographic gaps in their protection? A weak international filing strategy can severely cap the global sales potential of a drug.

- What is the remaining lifespan? Calculate the adjusted expiration date. A drug that looks promising but only has 5 years of patent life left is a very different investment proposition than one with 15 years remaining.

By performing this analysis, you might discover a small company whose lead asset is being undervalued by the market because analysts have not fully appreciated the strength and longevity of its patent moat. This is a classic IP-driven value investment.

H4: Spotting Early-Stage Companies with Disruptive IP

The earliest signs of true innovation often appear in the patent system long before they show up anywhere else. By setting up alerts and running searches on patent office databases (or using platforms that do this for you), you can spot trends and identify “stealth” companies.

- Track filings by key inventors: Are star scientists from a major university or a large pharma company now filing patents under a new, unknown company name? This could be a sign of a high-profile spin-out.

- Monitor filings in novel technology areas: Are you seeing a sudden cluster of patent applications around a new biological pathway or a new drug delivery technology (e.g., novel conjugates for antibody-drug conjugates, or new lipid nanoparticles for mRNA)? The companies filing these patents are at the bleeding edge of science.

- Look for “blocking” patents: Sometimes a small, unknown company holds a fundamental patent that a large pharmaceutical company may need to license or acquire to pursue its own R&D program. Identifying these “patent trolls” or, more charitably, “tollgate keepers” can be a lucrative investment strategy in itself.

This approach requires more technical expertise, but it’s how venture capitalists and sophisticated hedge funds find ground-floor opportunities before they hit the mainstream investment press.

Play #2: De-Risking Investments through IP Due Diligence

This play is less about finding new opportunities and more about protecting capital. For any M&A transaction, licensing deal, or significant equity investment, rigorous IP due diligence is not just a box to check; it is a critical risk mitigation exercise. Overlooking a fatal flaw in a target’s patent portfolio can lead to catastrophic value destruction.

H4: Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Navigating the Patent Minefield

An FTO analysis answers a simple but critical question: “Can we commercialize our product without infringing on someone else’s valid patent rights?” A company can have a perfectly valid patent on its own drug, but if manufacturing or selling that drug infringes a broader, pre-existing patent held by a third party, that patent is effectively worthless without a license.

Conducting a full FTO analysis is a complex legal task, but investors can perform a high-level screen:

- Search for broad patents in the company’s therapeutic and technology area that were filed before the company’s own patents.

- Pay close attention to patents held by major competitors and universities.

- Analyze the claims of these third-party patents. Do they appear to read on the product you’re evaluating?

Discovering a significant FTO issue—a “blocking patent”—is a major red flag. It could mean the company will have to pay hefty royalties to a competitor, face a costly injunction, or be forced to abandon the product altogether. Uncovering this before an investment is made is a prime example of how patent analysis saves money.

H4: Patent Validity and Enforceability Assessment

Just because a patent has been granted doesn’t mean it’s invincible. Patents can be challenged and invalidated in court or through administrative proceedings like an Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the USPTO. Before betting the farm on a company’s key patent, you need to assess its resilience.

- Review the Prosecution History: Did the patent examiner raise significant objections based on prior art (earlier inventions)? Did the company have to severely narrow its claims to get the patent granted? A tortured prosecution history can be a sign of weakness.

- Conduct a Prior Art Search: Can you find any patents or scientific publications that pre-date the patent’s filing and seem to disclose the same invention? If so, the patent may be vulnerable to an invalidity challenge.

- Check for “Inequitable Conduct”: Did the inventors or their attorneys fail to disclose known, material prior art to the patent office during examination? Such conduct can render an entire patent unenforceable.

This level of analysis often requires expert legal opinion, but for any nine-figure acquisition, it is an absolute necessity.

H4: Uncovering Hidden Liabilities: Patent Litigation and IPRs

A company’s SEC filings will disclose litigation that is “material,” but the definition of materiality can be subjective. Patent databases and court docket search tools provide an unvarnished view.

- Is the company currently being sued for infringement? This represents a direct financial risk and a potential injunction.

- Is the company’s own key patent being challenged in an IPR? IPRs have been dubbed “patent death squads” because a high percentage of challenged patent claims are invalidated. The initiation of an IPR against a company’s crown jewel patent is a significant negative catalyst.

- Is the company a serial plaintiff in patent suits? This could be a sign of a strong, assertive IP strategy, or it could indicate a business model that relies more on litigation than innovation.

A thorough scan for litigation and administrative challenges provides a crucial layer of risk assessment that complements traditional financial and clinical due diligence.

Play #3: Predicting and Profiting from the “Patent Cliff”

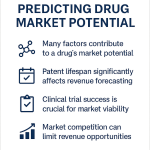

The patent cliff is one of the most dramatic and predictable events in the pharmaceutical industry. When a blockbuster drug with billions in annual sales loses its primary patent protection, its revenues can fall by 80-90% within a year or two as low-cost generics flood the market. For investors, this is a double-edged sword that presents opportunities on both sides of the trade.

H4: Identifying Blockbuster Drugs Nearing Expiration

This is the most straightforward application of patent data analysis. By screening databases for drugs with over $1 billion in annual sales and a key composition of matter patent expiring within a 1-3 year horizon, you can build a watchlist of upcoming patent cliffs.

Key data points to gather are:

- The drug’s annual sales and growth trajectory.

- The precise, fully adjusted expiration date of the primary patent(s).

- Any secondary patents (formulation, method-of-use) and their expiration dates.

- Any non-patent exclusivity (e.g., pediatric or orphan drug exclusivity) that could extend market protection.

This data allows you to model the expected revenue decline for the innovator company. This can inform a short-selling strategy or simply a decision to sell a long position before the cliff hits.

H4: Evaluating Generic and Biosimilar Entry Timing

The flip side of the innovator’s loss is the generic/biosimilar manufacturer’s gain. The first generic to market (or one of the first few) can capture enormous market share and profits. The timing of this entry is everything.

Patent data is your guide:

- Paragraph IV Filings: The first public signal of an impending generic challenge is the innovator company’s disclosure that it has received a Paragraph IV notice letter. This typically means a generic application has been filed with the FDA. The innovator has 45 days to sue, which triggers an automatic 30-month stay on FDA approval of the generic. Tracking these filings and the start of the 30-month clock is key to timing models.

- Litigation Outcomes: The 30-month stay is just a waiting period. The ultimate approval depends on the outcome of the patent litigation. Is the generic company likely to win, either by invalidating the patent or proving non-infringement? Monitoring key court rulings, settlements, or IPR outcomes is crucial. A settlement, for example, might include a specific date on which the generic is authorized to launch.

- 180-Day Exclusivity: For small-molecule drugs in the US, the first generic company to file a successful Paragraph IV challenge is rewarded with 180 days of market exclusivity, during which no other generics can be approved. Identifying the likely “first filer” is a key part of the investment thesis for a generic company’s stock.

By meticulously tracking these events, an investor can make a well-timed investment in a generic company poised to benefit from a major blockbuster’s patent expiration.

H4: Assessing the Brand’s Life-Cycle Management (LCM) Strategies

Innovator companies don’t just sit back and watch their revenues evaporate. They employ a host of LCM strategies to soften the patent cliff’s impact. An investor must evaluate the likely success of these defenses.

- “Patent Thickets”: As discussed, does the company have a dense web of secondary patents? Are these patents strong enough to deter or delay generic entry? AbbVie’s strategy for Humira is the canonical example.

- Product Hopping: Has the company launched a new, improved version of the drug (e.g., a once-daily formulation instead of twice-daily) and tried to switch patients to the new product before the original’s patent expires? The new product will have its own patent protection. The success of this switching effort is a key variable.

- Authorized Generics: Sometimes, the brand company will launch its own “authorized generic” through a subsidiary to compete with other generics and retain a portion of the market. Knowing if this is part of the company’s strategy is important for modeling post-expiration revenue.

The patent cliff is not a simple event. It’s a complex battle between the innovator’s defenses and the generic challengers’ offenses. Patent data is the map of this battlefield.

Play #4: Gauging Competitive Intensity in a Therapeutic Area

Beyond analyzing a single company or drug, patent data can be used to generate a panoramic view of an entire disease area. This “patent landscaping” is an invaluable tool for strategic planning and identifying investment themes. Who is winning the innovation race in oncology, cardiology, or immunology? Patent filings often hold the answer before sales figures do.

H4: Patent Landscaping: Mapping the IP Territory

A patent landscape analysis involves searching for and categorizing all of the patents and applications related to a specific technology or therapeutic area. This can be visualized to show:

- Who the major players are: Which companies are filing the most patents in this space? This includes large pharma, biotechs, and academic institutions.

- Trends over time: Is patenting activity in this area increasing or decreasing? A surge in filings can signal a “hot” area attracting significant R&D investment.

- Geographic focus: Where is the innovation happening, and where are companies seeking protection? Are U.S. and European companies dominating, or are Chinese and Korean firms emerging as major players?

This high-level map gives an investor a feel for the competitive dynamics of a market. A highly crowded landscape might suggest intense competition and pricing pressure, while a sparse landscape could indicate a less attractive market or a significant opportunity for a new entrant.

H4: White Space Analysis: Finding Uncharted Waters for Innovation

The most powerful output of a patent landscape is often the identification of “white space.” This is the inverse of landscaping; it’s about finding what is not being patented. White space analysis can reveal:

- Untapped biological targets: Are all the patents clustered around a few known mechanisms of action (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1 in immuno-oncology), while other promising biological pathways are being ignored? A company with IP in this white space could have a truly novel approach.

- Unmet needs in drug delivery: Is everyone focused on oral pills and injectables? A company developing a patented transdermal patch or inhalable version for a class of drugs could be addressing a significant unmet patient need.

- Underserved patient populations: Are there opportunities to develop and patent new formulations or dosage forms specifically for pediatric or geriatric patients?

For a venture investor or a corporate strategist, white space analysis is a direct map to R&D opportunities and potential investments in companies that are charting a unique course away from the crowded parts of the market.

H4: Tracking Competitor R&D Trajectories through Patent Filings

A company’s pipeline chart is a curated, public-facing document. Its patent filings are a much more raw and timely indicator of its true R&D direction. By systematically monitoring a competitor’s published patent applications, you can:

- See new projects 18-24 months before they are publicly disclosed.

- Understand the specific molecular structures and technologies they are working on.

- Infer their strategic priorities. Is a company traditionally focused on small molecules suddenly filing a wave of patents on cell therapies? This signals a major strategic pivot.

This kind of competitive intelligence is invaluable. It allows you to anticipate a competitor’s next move, assess the threat to your own portfolio, and identify companies whose R&D direction makes them attractive acquisition or partnership targets.

Advanced Analytics: Moving from Data to Decision-Grade Intelligence

The playbook above outlines foundational strategies. To gain a true, sustainable edge, investors must move beyond simple data retrieval and embrace more sophisticated analytical techniques. This involves quantifying patent quality, integrating IP data with other datasets, and harnessing the power of new technologies like artificial intelligence.

Quantitative Patent Metrics: Putting a Number on Innovation

How can you objectively compare the “strength” of two different patent portfolios? While a qualitative legal review is the gold standard, several quantitative metrics can serve as powerful proxies for patent value and quality.

H4: Patent Citation Analysis: Measuring Impact and Influence

When a new patent application is filed, the applicant and the examiner must cite any relevant prior art, including earlier patents. Conversely, over time, a patent will be cited by future patents as prior art. This creates a web of citations analogous to citations in academic literature.

- Forward Citations: The number of times a patent is cited by later patents is a strong indicator of its technological importance. A patent that is cited hundreds of times is likely a foundational piece of technology that many others are trying to build upon or design around. High forward citation counts are correlated with higher commercial value.

- Backward Citations: The number of patents a patent cites can also be revealing. A very high number of backward citations might suggest the invention is in a very crowded field and is more of an incremental improvement than a true breakthrough.

Analyzing citation patterns can help you quickly triage a large portfolio, identifying the most influential patents that warrant a deeper look.

H4: Patent Family Size: Gauging Geographic Ambition

As mentioned, a patent “family” consists of all the patents and applications around the world that relate to the same invention. The size of this family is a direct measure of the applicant’s investment and perceived commercial importance of the invention.

A company that only files a patent in its home country may not see a global market for the product. In contrast, an invention protected by a family of 20 patents covering the US, Europe, Japan, China, Canada, Australia, and key emerging markets is clearly one the company believes has significant worldwide commercial potential. It demonstrates a commitment to shouldering the high costs of international filing and prosecution, signaling a strong belief in the invention’s value.

H4: Claim Scope Analysis: Defining the Breadth of Protection

This treads closer to legal analysis but can be approached quantitatively. The “claims” are the numbered sentences at the end of a patent that define the legal boundaries of the invention.

- Number of Independent Claims: Independent claims stand on their own and define the broadest scope. A patent with multiple independent claims covering different aspects of the invention (e.g., the compound, a formulation containing it, and a method of using it) is generally stronger than one with a single independent claim.

- Claim Length and Limitations: Shorter claims with fewer limiting words are generally broader and more powerful. Sophisticated text analytics tools can be used to scan claim language across a portfolio to identify patents with particularly broad or narrow protective scopes.

These quantitative metrics are not a substitute for expert judgment, but they are powerful tools for screening large datasets, identifying outliers, and focusing due diligence efforts on the assets that matter most.

Integrating Patent Data with Other Datasets for a 360-Degree View

Patent data is powerful, but its predictive power multiplies exponentially when combined with other key datasets. The ultimate goal is to build a holistic, multi-dimensional view of a company or a drug.

H4: Clinical Trial Data (ClinicalTrials.gov)

The link between patents and clinical trials is fundamental. By mapping a company’s patent portfolio to its clinical pipeline (using a resource like ClinicalTrials.gov), you can answer critical questions:

- Does the company have strong, issued patent protection for the specific drug candidate in its Phase III trial?

- How much patent life will be left for that drug at the time of its potential launch? A drug that won’t launch until 2028 but whose key patent expires in 2031 has a very short window for recouping R&D costs.

- Are competitors running trials for similar drugs? Does your target company’s IP give it freedom-to-operate with respect to those competitors?

This integration turns abstract patent data into a concrete forecast of a specific product’s commercial viability.

H4: Financial Data (SEC Filings)

Cross-referencing patent intelligence with a company’s financial statements (10-K, 10-Q) can reveal a company’s strategy and potential vulnerabilities.

- Does the company’s stated R&D spending align with its patent filing velocity? A mismatch could be a red flag.

- In its disclosures of risk factors, how does the company describe its IP position and any ongoing litigation?

- If a company acquires another, analyzing the patent portfolio of the acquired entity can tell you the strategic rationale for the deal—was it for a product, a technology platform, or simply to remove a competitor?

H4: Regulatory Approvals and Scientific Publications

Linking patents to FDA/EMA approval documents and peer-reviewed scientific papers completes the picture. This allows you to trace the journey of an invention from the lab bench (publication), to legal protection (patent), to clinical validation (trials), and finally to market (regulatory approval). A company that shows a consistent ability to successfully navigate this entire pathway is a far more compelling investment than one that merely files a lot of patents.

The Rise of AI and Machine Learning in Patent Analytics

The sheer volume and complexity of patent data make it a perfect candidate for analysis using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). This is the cutting edge of IP-driven investment.

H4: Automating Landscaping and FTO Searches

Traditional patent landscaping and freedom-to-operate searches are labor-intensive, manual processes. AI-powered tools are changing the game by using natural language processing (NLP) to:

- Read and understand the technical content of millions of patents.

- Automatically classify patents into highly specific technical categories.

- Identify semantically similar patents, even if they don’t use the exact same keywords.

This allows analysts to conduct more comprehensive searches in a fraction of the time, uncovering relevant prior art or potential blocking patents that a manual search might miss.

H4: Predictive Models for Litigation Outcomes and Patent Value

This is the holy grail of patent analytics. Researchers and data science firms are now building predictive models that ingest dozens of variables to forecast key outcomes:

- Litigation Prediction: By analyzing factors like the technology area, the companies involved, the judge, and the specific arguments made, ML models can now predict the likelihood of a patent being invalidated in an IPR or district court case with increasing accuracy.

- Valuation Models: Other models attempt to predict a patent’s commercial value by correlating features (forward citations, family size, claim scope, etc.) with historical data on licensing royalties, M&A premiums, and product sales.

While still an emerging field, these AI-driven predictive tools represent the future of the industry. The investors who successfully integrate these capabilities into their workflow will have an unmatched analytical advantage.

Case Studies: Patent Data in Action

Theory and frameworks are essential, but the true test of their value is in their application. Let’s examine three landmark cases from recent pharmaceutical history, each of which powerfully illustrates a different facet of how patent strategy and analysis drive billion-dollar investment outcomes.

Case Study 1: The Gilead vs. Merck Battle over Sovaldi (Sofosbuvir)

This case is a masterclass in the paramount importance of IP provenance and due diligence, showing how a hidden flaw in a patent’s history can have staggering financial consequences.

H4: A Tale of Foundational Patents and Costly Litigation

Gilead Sciences launched Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) in 2013, a revolutionary cure for Hepatitis C that would go on to generate tens of billions in sales. The drug was the centerpiece of Gilead’s $11 billion acquisition of Pharmasset in 2011. The investment thesis was simple: acquire Pharmasset for its crown jewel patents covering this game-changing molecule.

However, Merck & Co. soon filed a lawsuit claiming that Sovaldi infringed on two of its own, earlier-filed patents covering a similar class of antiviral compounds. Merck argued that its scientists had invented the core scaffold of the drug first. If Merck won, it would be entitled to a significant royalty—initially pegged at 10%—on all of Sovaldi’s massive sales. A jury initially agreed, awarding Merck $200 million in past damages and setting the stage for billions more in future royalties.

The twist came later. During the legal proceedings, it emerged that a key Merck scientist involved in its patent application had lied under oath about his knowledge of a competing compound from Pharmasset. This “unclean hands” and “inequitable conduct” led a federal judge to throw out the entire $200 million verdict, declaring Merck’s patents unenforceable against Gilead [2]. Gilead walked away without paying a cent in royalties.

H4: Investment Lessons in IP Provenance and Due Diligence

The Sovaldi case offers several profound lessons for investors:

- FTO is King: Gilead’s $11 billion bet on Pharmasset was nearly upended by a pre-existing patent portfolio. This underscores the absolute necessity of a deep freedom-to-operate analysis before any major acquisition. Did Gilead’s due diligence team miss the Merck patents, or did they assess them and decide they had a strong non-infringement case?

- Validity is Not Enough; Enforceability Matters: Merck’s patents were deemed valid in a technical sense, but they were rendered useless by the company’s own misconduct during litigation. This highlights the importance of looking beyond the patent document itself to the “soft” factors of its history and the conduct of the parties involved.

- Litigation is Unpredictable: The outcome swung wildly, from a massive victory for Merck to a complete defeat. This shows the inherent risk in investment theses that depend on the outcome of a specific court case. For investors watching from the sidelines, the stock prices of both companies reacted sharply to each legal development.

Case Study 2: AbbVie’s “Patent Thicket” Strategy for Humira (Adalimumab)

If Sovaldi was about a single battle over a foundational patent, Humira is about a long, drawn-out war of attrition fought with a vast army of secondary patents. It is the definitive example of a successful life-cycle management strategy.

H4: Maximizing a Blockbuster’s Lifespan through Layered IP

Humira (adalimumab), an antibody for treating autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, was for many years the world’s best-selling drug, with peak annual sales exceeding $20 billion. Its core composition of matter patent in the U.S. expired in 2016. By traditional logic, this should have been the start of a precipitous patent cliff.

However, AbbVie had spent over a decade meticulously building a fortress of intellectual property around Humira. This “patent thicket” consisted of over 130 patents covering not the molecule itself, but everything else: specific formulations, methods of manufacturing, and various method-of-use patents for the dozen-plus indications for which Humira was approved [3].

When biosimilar manufacturers like Amgen, Samsung Bioepis, and Sandoz prepared to launch their versions in the U.S. after 2016, they found themselves facing a legal minefield. To launch, they would have to litigate and invalidate dozens of these secondary patents—a prohibitively expensive and time-consuming process.

Ultimately, one by one, the biosimilar challengers settled with AbbVie. In these settlements, AbbVie granted them licenses to launch their biosimilars, but not until 2023. This strategy single-handedly kept biosimilar competition out of the lucrative U.S. market for nearly seven years after the main patent expired, adding an estimated $100 billion in revenue for AbbVie [4].

H4: Implications for Investors in Both Brand and Biosimilar Companies

The Humira saga transformed how investors analyze the patent cliff:

- Secondary Patents Matter: It proved that a well-constructed portfolio of formulation and method-of-use patents can be just as commercially valuable, if not more so, than the original composition of matter patent. Investors can no longer look at just one expiration date.

- Valuing Innovators: When valuing an innovator company with a maturing blockbuster, you must now analyze the density and quality of its patent thicket. A company with a robust LCM portfolio will have a much shallower revenue decline post-expiration.

- Assessing Biosimilar Risk: For investors in biosimilar companies, the Humira case introduced a new level of risk. The investment thesis now depends not just on developing a good product, but on the company’s ability to navigate or litigate its way through a complex patent thicket, which can lead to long, uncertain delays.

Case Study 3: The Generic Entry Play – Teva and the Copaxone Windfall

This case highlights the other side of the coin: the high-risk, high-reward world of challenging a complex patent portfolio to launch a first generic, demonstrating how deep patent analysis is crucial for success in the generics industry.

H4: Navigating Complex IP to Launch a First Generic

Copaxone (glatiramer acetate) was Teva Pharmaceutical’s flagship branded drug for multiple sclerosis. Ironically, Teva is also one of the world’s largest generic drug manufacturers. When Copaxone’s patents began to expire, other generic companies, including a partnership between Momenta Pharmaceuticals and Sandoz (a Novartis division), lined up to launch a copy.

The challenge was immense. Copaxone is not a simple small molecule; it’s a complex mixture of polypeptides. Its protective patents were notoriously difficult to design around or invalidate. The generic challengers had to not only prove their product was equivalent but also fight off a barrage of patent infringement lawsuits from Teva.

Momenta and Sandoz embarked on years of painstaking litigation, challenging Teva’s patents one by one in court and through IPR proceedings. They successfully invalidated several key patents, clearing a path to launch. In 2017, they received FDA approval and launched Glatopa, the first substitutable generic version of Copaxone.

H4: The High-Risk, High-Reward World of Paragraph IV Challenges

This case study is a playbook for investors in the generic and specialty pharma space:

- Technical and Legal Expertise as a Moat: Momenta’s success was built on its sophisticated analytical capabilities to characterize complex drugs and its legal prowess to challenge difficult patents. For investors, evaluating a generic company’s R&D and legal track record is just as important as analyzing its finances.

- The Value of Being First: As the first generic, Glatopa captured significant market share from the much more expensive branded product. The 180-day exclusivity period for first filers is a massive financial incentive that can dramatically boost a generic company’s earnings for several quarters.

- Patience and Risk Tolerance: The journey from filing the ANDA to launch took many years and millions in legal fees. Investing in a Paragraph IV challenger requires a long time horizon and the stomach to withstand the ups and downs of litigation. An investor who had analyzed the weakness in Teva’s patents and understood Momenta’s capabilities could have made a highly profitable long-term investment.

These cases, each in their own way, demonstrate that understanding patent data is not an academic exercise. It is a fundamental driver of risk and return in the pharmaceutical sector.

The Future of Pharmaceutical IP and Investment Strategy

The principles we’ve discussed are timeless, but the landscape upon which they are applied is in constant flux. Investors who want to maintain their edge must not only master the present but also anticipate the future. Several powerful trends are reshaping the intersection of intellectual property and pharmaceutical investment.

The Impact of New Modalities: Cell and Gene Therapies, mRNA

The pharmaceutical industry is in the midst of a revolution, moving beyond traditional small molecules and antibodies to entirely new therapeutic modalities. These innovations present novel IP challenges and opportunities.

- Cell and Gene Therapies (CGTs): How do you patent a living drug, like a CAR-T cell therapy? The IP is incredibly complex, covering not just the therapeutic construct (the chimeric antigen receptor) but also the methods of extracting, modifying, and re-infusing the patient’s cells. The “process is the product” concept is even more critical here than for biologics. Investors will need to become adept at valuing portfolios that include patents on manufacturing protocols, gene editing tools (like CRISPR), and viral vectors.

- mRNA Therapies: The success of the COVID-19 vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech brought mRNA technology to the forefront. The IP landscape is a hornet’s nest of overlapping patents on the mRNA sequence itself, the chemical modifications that make it stable, and, critically, the lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery systems that get the mRNA into the cell. The ongoing litigation between Moderna, Pfizer, and smaller LNP pioneers like Arbutus Biopharma shows that the battles over this platform technology will shape the industry for years to come. Investors must track not just product patents but these foundational platform patents.

Policy Shifts and Their Investment Implications (e.g., Inflation Reduction Act)

Government policy can alter the value of pharmaceutical patents overnight. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) passed in the U.S. in 2022 is a prime example. For the first time, it gives Medicare the power to “negotiate” (effectively, set) prices for certain high-cost drugs.

Crucially, small-molecule drugs are subject to negotiation 9 years after approval, while biologics get a 13-year window [5]. This seemingly small difference has massive investment implications:

- It creates a powerful incentive for companies—and their investors—to prioritize the development of biologics over small molecules, as they will enjoy a longer period of free-market pricing.

- It may reduce the value of traditional patent cliff analysis for the most affected drugs. A drug’s revenue may start to decline due to negotiated prices before its patents expire, changing the financial models.

- It alters the strategic value of life-cycle management. Extending exclusivity through secondary patents may be less valuable if the price has already been significantly reduced by Medicare negotiation.

Investors must now layer this policy analysis on top of their patent analysis to accurately value future revenue streams.

The Digitization of R&D and AI-Discovered Drugs

The very process of drug discovery is being transformed by artificial intelligence. Companies like Recursion Pharmaceuticals and Schrödinger are using AI platforms to identify novel drug targets and design new molecules at a speed previously unimaginable. This trend has several IP implications:

- Inventorship Questions: Can an AI be an “inventor” on a patent? Current law in most jurisdictions says no, but this will be a subject of intense future debate. The legal framework will need to adapt.

- The Nature of the IP: The most valuable IP for these companies may not be the patent on a single drug, but the proprietary data, algorithms, and software platform that generates the drug candidates. Investors need to learn how to value these new types of “digital” IP assets, which are often protected by trade secrets rather than patents.

- Accelerated Timelines: If AI can shorten the discovery and pre-clinical phases of R&D, drugs may reach the market with more of their 20-year patent term intact. This would increase the value of each patent and could change the calculus for PTE and other extensions.

The future belongs to investors who can understand and value this convergence of biology, data science, and intellectual property law.

Conclusion: From Data Points to Strategic Dominance

We began this journey with a simple premise: that in the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical investing, patent data provides a unique, predictive lens into the future. We have seen how this data forms the bedrock of a drug’s commercial value, from the crown jewel composition of matter patents to the strategic thickets that defend against competition.

We have explored the practicalities of sourcing this data, from the authoritative halls of patent offices to the curated, user-friendly dashboards of commercial platforms. We have laid out a strategic playbook, demonstrating how to use this intelligence to find undervalued innovators, de-risk major investments, play the patent cliff, and map entire competitive landscapes. And we have looked over the horizon at the new technologies and policies that are reshaping the rules of the game.

Synthesizing the Approach

Leveraging drug patent data is not a single action but a continuous, integrated process. It means making IP analysis a core competency, not an afterthought. It requires a mindset that sees a patent filing not as a legal artifact, but as a signal of strategic intent; that sees an expiration date not as a simple fact, but as the starting gun for a complex competitive battle.

It is about connecting the dots between a patent claim, a clinical trial protocol, a line item in a 10-K, and a pending piece of legislation. The investor who can synthesize these disparate streams of information into a coherent thesis is the one who will make decisions with conviction and clarity while others are still reacting to yesterday’s news.

The Enduring Value of a Patent-Centric Investment Thesis

The pharmaceutical industry will always be defined by the dual pressures of innovation and access. The patent system, for all its complexities and controversies, remains the central mechanism for balancing these forces. As long as this holds true, the ability to decode its language and anticipate its consequences will remain one of the most potent sources of competitive advantage available to any investor.

By embracing a patent-centric approach, you are not merely looking at data points. You are reading the blueprints of innovation itself. You are positioning yourself to fund the next generation of life-saving medicines and, in the process, to generate extraordinary returns. The blueprint is there for the reading. The only question is whether you have the tools and the framework to understand what it is telling you.

Key Takeaways

- Patents are Predictive Intelligence: Unlike financial statements which are historical, patent data (filings, expirations, litigation) offers a forward-looking view into a company’s revenue potential, R&D strategy, and competitive threats.

- Not All Patents Are Equal: Composition of Matter patents are the “crown jewels” providing the strongest protection. Formulation, method-of-use, and process patents are crucial for life-cycle management and defending against generics/biosimilars.

- The “Patent Cliff” is a Strategic Battleground: Predicting the revenue decline of an innovator and the rise of a generic requires a deep analysis of patent expiration dates, Paragraph IV challenges, litigation outcomes, and the innovator’s defensive “patent thicket.”

- IP Due Diligence is Critical Risk Mitigation: Before any major investment (M&A, VC), a thorough analysis of Freedom-to-Operate (FTO), patent validity, and ongoing litigation can prevent catastrophic losses.

- Data Integration is Key: The true power of patent analysis is unlocked when it’s integrated with other datasets, including clinical trial data (ClinicalTrials.gov), financial filings (SEC), and regulatory information (FDA).

- Use Curated Platforms to Save Time and Improve Accuracy: Raw patent data from sources like the USPTO is difficult to analyze. Commercial platforms like DrugPatentWatch aggregate, verify, and structure this data into actionable business intelligence.

- The Future is Complex: New modalities like cell/gene therapy and policy shifts like the Inflation Reduction Act are creating new IP challenges and opportunities. Investors must adapt their analytical frameworks to stay ahead.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Q: How early can patent data provide a signal about a new drug?

A: Remarkably early. A company typically files a provisional patent application as soon as it has synthesized a promising new molecule and has some initial data, often before formal preclinical studies begin. This application is not published. However, within 18 months, the company will usually file a corresponding non-provisional or PCT application, which is published. This means you can get a detailed look at the chemical structure and intended use of a new drug candidate a full 18-24 months before the company might formally announce it as part of its development pipeline. For investors, this is an incredibly powerful early-warning system.

2. Q: I’m not a patent lawyer. Isn’t this analysis too technical for a business professional or investor?

A: While a full legal opinion requires a patent attorney, 80% of the strategic value can be unlocked by a business professional using the right tools and frameworks. You don’t need to be able to argue the nuances of claim construction to understand the strategic implications of key data points. For example, you can learn to identify the type of patent (composition vs. method-of-use), check its adjusted expiration date on a platform like DrugPatentWatch, see if it’s being litigated, and assess the size of its patent family. These high-level business metrics, derived from the legal data, are what drive most strategic investment decisions.

3. Q: With the rise of Inter Partes Reviews (IPRs) at the USPTO, which have a high rate of invalidating patents, is the U.S. patent system still a reliable way to protect a drug?

A: This is a critical question. While it’s true that IPRs have created a new and significant threat to patent validity, the system is far from broken. First, the high invalidation rates often cited include patents from all technology areas; pharmaceutical patents have historically fared somewhat better. Second, it has forced innovator companies to focus on filing higher-quality patents with stronger supporting data from the outset. For an investor, the existence of the IPR system makes patent due diligence more important, not less. It creates opportunities to bet against companies with weak, vulnerable patents and to invest with more confidence in companies whose key patents have either survived an IPR challenge or are of such high quality that they deter a challenge in the first place.

4. Q: How does the IP analysis for a biologic and its biosimilar competitor differ from a small-molecule drug and its generic?

A: The core principles are similar, but the details are critically different. For biologics, process patents are far more important, as the manufacturing process is incredibly complex and difficult to replicate. The litigation pathway is also different, governed by the BPCIA’s “patent dance”—a complex, timed exchange of information and patent lists between the innovator and the biosimilar applicant. Furthermore, there is no automatic 180-day exclusivity for the first biosimilar. The key takeaway for investors is that the barriers to entry for biosimilars are generally much higher than for small-molecule generics, involving not just patent hurdles but also more complex manufacturing and more extensive clinical trials. This often leads to fewer competitors and a less severe price erosion for the branded biologic post-expiration.

5. Q: My investment strategy is focused on MedTech (medical devices), not pharma. How much of this analysis is transferable?

A: A great deal of it is transferable, with some key adjustments. The concepts of patent strength, FTO analysis, competitive landscaping, and life-cycle management are all directly applicable to medical devices. However, the ecosystem is different. Instead of the Orange Book, you’ll be looking at the FDA’s 510(k) or PMA databases. The “patent cliff” can be less steep, as innovation is often more incremental and driven by a continuous stream of product improvements rather than a single blockbuster molecule. Patent thickets are extremely common in MedTech, with companies patenting every minor tweak to a device. Therefore, claim scope analysis and tracking competitor filings for iterative design changes become even more important for a MedTech investor.

References

[1] DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20-33.

[2] Fee, T. (2016). Merck’s $200M patent infringement verdict against Gilead is wiped out. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL2N18Y1U7/

[3] I-MAK (Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge). (2018). Overpatented, Overpriced: How Excessive Patenting on Humira is Driving up U.S. Drug Prices. Available at: https://www.i-mak.org/humira/

[4] Langreth, R., & Griffin, R. (2023). AbbVie’s Humira Hegemony Is About to End in a $100 Billion Moment of Truth. Bloomberg. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-01-26/humira-s-patent-cliff-is-a-100-billion-moment-of-truth-for-abbvie-abv

[5] The White House. (2022). FACT SHEET: The Inflation Reduction Act Supports Workers and Families. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/19/fact-sheet-the-inflation-reduction-act-supports-workers-and-families/