In the modern pharmaceutical landscape, we find ourselves grappling with a profound and persistent paradox. On one hand, the investment in research and development has reached unprecedented levels, with billions of dollars poured into the quest for the next breakthrough therapy. On the other hand, the output of truly novel drugs—new molecular entities (NMEs) that represent a genuine leap forward in medicine—has not kept pace. This R&D productivity crisis, coupled with the relentless pressure of the patent cliff and the brutal commoditization of the traditional generics market, has created a strategic valley of death for many companies. It is a treacherous space caught between the high-risk, high-cost gamble of de novo drug discovery and the low-margin, high-volume battle of imitation.

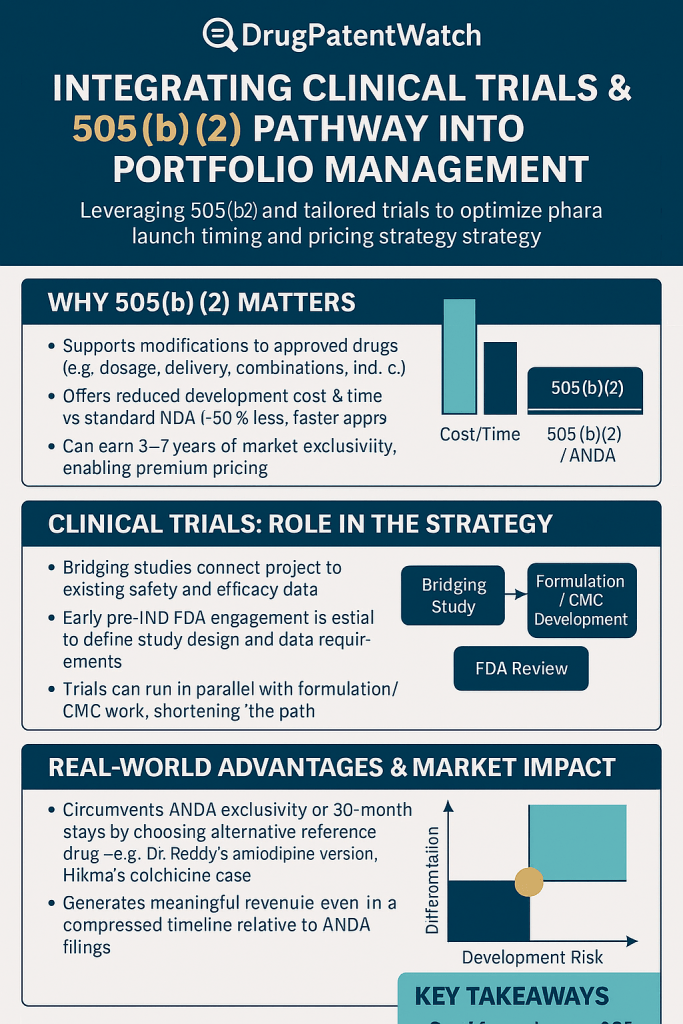

How, then, does a pharmaceutical company not only survive but thrive in this environment? The answer does not lie in simply doing more of the same. It requires a fundamental shift in strategy—a move towards smarter, more efficient, and more value-driven models of innovation. This is where the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway emerges not as a mere regulatory footnote, but as the strategic bridge across that valley.

This pathway, a hybrid that ingeniously blends elements of a full New Drug Application (NDA) with the efficiencies of a generic submission, represents one of the most powerful and underleveraged tools in the modern pharmaceutical arsenal. It allows for meaningful innovation—the creation of new, differentiated, and proprietary products—but on a foundation of established science, thereby de-risking development, compressing timelines, and dramatically reducing costs. For both branded and generic companies, it offers a route to escape the binary choice between blockbuster hunting and price-driven commoditization.

This report is designed to be your comprehensive strategic playbook for mastering the 505(b)(2) pathway. We will move far beyond a simple regulatory overview. Instead, we will dissect how to integrate this pathway into the very core of your corporate strategy, from portfolio management and candidate selection to clinical trial design and market access. We will explore how to leverage 505(b)(2) to build a resilient and diversified pipeline, how to design clinical programs that not only secure approval but also build a powerful value story for payers, and how to synergize this approach with aggressive generic launch strategies, including the high-stakes game of Paragraph IV patent litigation. Our journey will transform your understanding of the 505(b)(2) pathway from a tactical option into a cornerstone of sustainable growth and market dominance.

Part I: The Strategic Foundation: Modern Pharmaceutical Portfolio Management

The High-Stakes Balancing Act: Core Principles of Pharma Portfolio Strategy

At its core, pharmaceutical portfolio management is the strategic heart of the enterprise. It is the high-stakes crucible where science, finance, and market dynamics collide, and where the decisions made today will dictate the company’s viability a decade from now. It is far more than a simple administrative function of tracking projects; it is a dynamic, continuous process of evaluating, prioritizing, and allocating finite resources—capital, talent, and time—to a collection of high-risk, long-term assets in a way that maximizes value and aligns with the overarching goals of the business.2

The fundamental objective is to maximize the return on every R&D dollar invested. However, achieving this requires a delicate and perpetual balancing act. The portfolio must be structured to manage a central paradox of the industry: the need to fund long-term, high-risk, breakthrough innovation while simultaneously delivering the short-term financial stability and growth demanded by shareholders and the market. A portfolio composed entirely of high-risk 505(b)(1) NMEs is volatile, capital-intensive, and subject to brutal attrition rates. Conversely, a portfolio consisting solely of traditional 505(j) generic drugs is low-risk but suffers from relentless margin erosion and lacks the long-term growth drivers necessary for sustained success.

This is why a diversified portfolio is not a luxury but a necessity. Effective portfolio management seeks to achieve several interconnected goals:

- Maximize Portfolio Value: The ultimate goal is to maximize the financial value of the entire portfolio, often measured by metrics like risk-adjusted Net Present Value (eNPV). This requires a “value-driven” approach where every project is rigorously assessed for its potential commercial return and its probability of success.

- Ensure Strategic Alignment: Every project in the pipeline must have a clear and justifiable link to the company’s broader strategic objectives. These objectives should be specific, defining not only financial targets like ROI but also the disease areas of interest, the specific unmet medical needs the company aims to address, and the types of products it wishes to pursue.2

- Balance Risk and Reward: A healthy portfolio is a balanced one. It should contain a mix of assets across different risk profiles, therapeutic areas, and stages of development. This includes a blend of high-risk, high-reward projects (like first-in-class NMEs) with lower-risk, more predictable endeavors.

- Optimize Resource Allocation: With resources being inherently limited, the process must ensure that capital and personnel are directed toward the projects with the highest strategic value and potential return. This necessitates a disciplined and data-driven process for making tough decisions—including the crucial ability to “promote winners and stop losers” early and decisively.

In this strategic context, 505(b)(2) assets play a unique and vital role. They are not merely an alternative to NMEs or generics; they are an essential component of a resilient, diversified portfolio. By offering a pathway to proprietary, differentiated products with moderate risk, moderate cost, and faster timelines, 505(b)(2) projects can serve as the crucial middle ground. They can generate valuable near- and mid-term revenue streams that provide financial stability and can, in turn, be used to fund the more ambitious, longer-term, and higher-risk 505(b)(1) programs that are the lifeblood of future growth. Integrating these assets is the key to building a portfolio that can weather the storms of clinical failures and patent expiries while consistently delivering value.

The Portfolio Manager’s Toolkit: Frameworks for Decision-Making

To navigate the complexities of portfolio management, decision-makers rely on a spectrum of analytical tools, ranging from simple qualitative screens to highly sophisticated financial models. The mastery of portfolio management lies not in using the most complex tool, but in applying the right tool at the right stage of a project’s lifecycle. A phased approach to evaluation prevents “analysis paralysis” for early-stage concepts while ensuring the necessary financial and strategic rigor for late-stage, high-investment decisions.

Qualitative & Semi-Quantitative Tools

These foundational tools are ideal for the initial screening and triage of a large number of potential projects, where data is limited and uncertainty is high.

- Checklists and Scoring Models: At the simplest level, a checklist ensures that a project meets a minimum set of predetermined criteria covering scientific, medical, regulatory, and financial feasibility. A more advanced version is the scoring model, where various success factors (e.g., unmet medical need, competitive advantage, technical feasibility, strategic fit) are assigned weights based on their importance to the company. Each project is then scored against these factors, yielding a quantitative score that allows for objective comparison and ranking. Gaining buy-in from all key stakeholders on the criteria and weights is essential for the model’s credibility and utility.

- Profile Models: These models provide a powerful visual comparison of projects. Various criteria are listed, and each project is rated on a numeric scale (e.g., -5 to +5). When the ratings for a single project are connected, they form a unique visual “profile,” making it easy to see a project’s relative strengths and weaknesses at a glance compared to other candidates.

- Risk-Reward Matrices: Classic strategic frameworks like the BCG Growth-Share Matrix or the GE-McKinsey Nine-Box Matrix are invaluable for visualizing the overall balance of the portfolio.2 Products are plotted on a 2×2 or 3×3 grid based on dimensions like market attractiveness and competitive position. This categorizes assets into groups such as “Stars” (high growth, high share), “Cash Cows” (low growth, high share), “Question Marks” (high growth, low share), and “Dogs” (low growth, low share), guiding strategic decisions on whether to invest, maintain, harvest, or divest. A promising 505(b)(2) project, for example, might enter the portfolio as a “Question Mark” and, with successful development and commercialization, evolve into a “Star.”

Quantitative & Financial Tools

As a project progresses and more data becomes available, the evaluation must become more financially rigorous. These tools are essential for justifying the significant investments required for mid- and late-stage development.

- Standard Financial Metrics: These are the bedrock of project valuation.

- Return on Investment (ROI) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR): These metrics calculate the expected profitability of a project. The project’s expected IRR is compared against a predetermined minimum acceptable rate, or “hurdle rate,” to determine financial viability.

- Net Present Value (NPV): NPV calculates the present value of all future cash flows (both inflows and outflows) associated with a project, discounted at a specific rate. A positive NPV indicates a financially attractive project. The profitability index, which uses NPV as the numerator, provides a measure of project magnitude that is often more useful than IRR alone.

- Decision Tree Analysis and Expected NPV (eNPV): This is the gold standard for valuation in the pharmaceutical industry because it explicitly incorporates the immense risk and uncertainty inherent in drug development. A decision tree maps out the entire development path of a drug, with nodes representing key decision points (stage-gates) and chance events (e.g., success or failure of a clinical trial). Each branch is assigned a probability of occurrence and an associated cost or payoff. By working backward through the tree, one can calculate the Expected Net Present Value (eNPV), which is the risk-adjusted value of the asset. This powerful technique allows for a true “apples-to-apples” comparison of projects with different risk profiles, timelines, and potential rewards, making it an indispensable tool for prioritizing late-stage assets.6

- Advanced Quantitative Methods: For organizations at the cutting edge of portfolio management, even more sophisticated techniques can be employed. Mean-Variance Optimization, adapted from financial portfolio theory, can be used to construct an “efficient frontier” of R&D projects, identifying the portfolio mix that offers the highest expected return for a given level of risk (variance). Robust Optimization takes this a step further by designing portfolios that are optimized to perform well even under worst-case scenarios, addressing the deep uncertainty in input parameters like clinical success rates and peak sales forecasts.

By systematically applying this toolkit, portfolio managers can move from subjective, gut-feel decisions to a disciplined, data-driven process that ensures resources are consistently allocated to the assets that will create the most value for the organization.

Part II: The 505(b)(2) Pathway: Your Strategic Shortcut to Innovation

Decoding the “Hybrid” Pathway: What Is a 505(b)(2) Application?

At the heart of any advanced pharmaceutical strategy lies a deep understanding of the regulatory landscape. Among the pathways to market in the United States, the 505(b)(2) route is perhaps the most strategically versatile. Established by the landmark Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, the 505(b)(2) pathway was ingeniously designed to foster innovation while preventing the unnecessary and costly duplication of research.

So, what exactly is it? A 505(b)(2) application is a type of New Drug Application (NDA) submitted to the FDA. Like a traditional NDA, it must contain full reports of investigations demonstrating the drug’s safety and effectiveness. However, its defining feature—and the source of its power—is that it allows at least some of the information required for approval to come from studies that were not conducted by or for the applicant and for which the applicant has not obtained a right of reference.11 In essence, the FDA is given express permission to rely on existing data, such as its own previous findings of safety and efficacy for an approved drug or data from published scientific literature.13

This is why the 505(b)(2) is often referred to as a “hybrid” application.10 It strategically blends elements of the two other primary pathways:

- The 505(b)(1) Pathway: The traditional, “stand-alone” NDA for a new chemical entity (NCE), which requires the sponsor to conduct and submit a complete package of their own preclinical and clinical data.14

- The 505(j) Pathway: The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) for a generic drug, which does not require new clinical trials but instead demonstrates bioequivalence to a previously approved “Reference Listed Drug” (RLD).10

The 505(b)(2) sits squarely between these two. It is a full NDA, not a generic ANDA, but it is abbreviated in the sense that it leverages the foundation of knowledge already established for an existing drug. This makes it the ideal regulatory vehicle for innovations and improvements made to previously approved molecules. The types of products that are prime candidates for this pathway are those that introduce a meaningful change to an existing drug, such as 10:

- Changes in Dosage Form: e.g., developing an oral liquid from a solid tablet.

- Changes in Strength: Creating a new, unapproved dosage strength.

- Changes in Route of Administration: e.g., developing a transdermal patch from an oral drug.

- New Formulations: Modifying excipients to improve stability or patient tolerance.

- New Combination Products: Combining two or more previously approved active ingredients into a single product.

- New Indications: Repurposing an existing drug for a new therapeutic use.

- Prodrugs: Creating a new version of a drug that is metabolized into the active form in the body.

By providing a streamlined path for these value-added medicines, the 505(b)(2) pathway serves as a powerful engine for incremental innovation, allowing companies to bring clinically significant improvements to patients more efficiently.

A Tale of Three Pathways: A Strategic Comparison

Choosing the correct regulatory pathway is one of the most consequential decisions in drug development. It dictates the scope of the required research, the overall cost and timeline, and the potential for market exclusivity. For executives, understanding the strategic trade-offs between the 505(b)(1), 505(b)(2), and 505(j) pathways is not just a regulatory exercise; it is a fundamental business decision.

To illustrate these trade-offs, consider an analogy. Bringing a drug to market via the 505(b)(1) pathway is like designing and building a custom house from scratch on an undeveloped plot of land. It offers the greatest potential for a unique and valuable creation, but it is also the most expensive, time-consuming, and fraught with risk. The 505(j) pathway is akin to buying a mass-produced prefabricated home; it is fast, efficient, and low-cost, but it is identical to every other home in the development and offers no differentiation. The 505(b)(2) pathway, then, is like purchasing a historic home with a solid foundation and “good bones” and undertaking an extensive, modern renovation. You leverage the existing structure to save time and money, but the final product is a unique, differentiated, and highly valuable asset.

The following table provides a direct, at-a-glance comparison of these three pathways across the most critical strategic dimensions.

| Strategic Dimension | 505(b)(1) NDA | 505(b)(2) NDA | 505(j) ANDA |

| Purpose / Ideal Candidate | New Chemical Entities (NCEs); truly novel drugs with no prior FDA approval.18 | Modified versions of previously approved drugs (e.g., new dosage form, strength, indication, combination).10 | Generic duplicates of an existing Reference Listed Drug (RLD).10 |

| Data Requirements | Full, sponsor-conducted preclinical (animal) and clinical (human) safety and efficacy studies.18 | Full safety and efficacy reports, but can rely on existing data (FDA findings, literature) plus new “bridging” studies to link to the RLD.13 | No new clinical trials required. Must demonstrate bioequivalence to the RLD and sameness in key characteristics.15 |

| Development Cost | Highest ($1B – $2.6B+).13 | Moderate (typically $3M – $100M); significantly less than 505(b)(1) but more than 505(j).18 | Lowest; primarily costs associated with formulation and bioequivalence studies.19 |

| Development Timeline | Longest (10-15 years).10 | Moderate (3-5 years); significantly faster than 505(b)(1).10 | Shortest; focused on formulation and BE testing. |

| Market Exclusivity | Highest potential. Typically 5 years for an NCE, plus potential for 7-year orphan drug or 6-month pediatric exclusivity.13 | Strong potential. 3 years for new clinical investigations, 5 years if it qualifies as an NCE, 7 years for orphan drugs.10 | Generally none, except for the highly valuable 180-day exclusivity for the first successful Paragraph IV patent challenger.19 |

| Innovation Level | High. Represents a novel therapeutic approach or mechanism. | Incremental / Value-Added. Represents an improvement or modification to an existing therapy.19 | Low / None. Represents a direct copy of an existing therapy. |

One of the most critical takeaways from this comparison is that these pathways are not interchangeable at the whim of the sponsor. The FDA acts as a crucial gatekeeper. A drug product that is a duplicate of a listed drug and is eligible for approval as a generic must be submitted under the 505(j) ANDA pathway. The agency will generally refuse to file a 505(b)(2) application for such a product. This regulatory reality has profound strategic implications. It means that a 505(b)(2) strategy cannot be based on convenience; it must be predicated on a scientifically and clinically meaningful difference from the RLD. The very foundation of a successful 505(b)(2) program is the identification of a modification that is significant enough to preclude the 505(j) pathway while being streamlined enough to avoid the full burden of a 505(b)(1) development program.

Identifying the “Golden” Candidate: A Four-Pillar Viability Framework

The success of a 505(b)(2) strategy hinges on the very first step: selecting the right candidate. A winning candidate is one that possesses documented market differentiation, low development risk, and high profit potential.10 Simply identifying a possible modification to an existing drug is not enough. A rigorous, multi-faceted evaluation is required to separate the “golden” opportunities from those destined for clinical, regulatory, or commercial failure.

We advocate for a disciplined “Four-Pillar Viability Framework” to guide this critical assessment process. This framework ensures a holistic evaluation, forcing a cross-functional dialogue between R&D, regulatory, clinical, and commercial teams from the earliest stages of consideration. The most common and costly mistake is to view candidate selection through a purely scientific or regulatory lens, only to discover late in the process that there is no viable market or reimbursement path for the product.

The most critical insight driving this framework is the need to “begin with the end in mind.” The commercial viability assessment, particularly from the payer’s perspective, cannot be an afterthought; it must be a primary filter at the outset. Before a single dollar is spent on formulation development, the team must be able to articulate a compelling value proposition that will resonate not just with the FDA, but with the payers who ultimately control market access. This means the Target Product Profile (TPP)—the blueprint that defines the desired characteristics of the final drug—must be co-developed by a team that includes market access and commercial experts from day one.

The following table outlines the key questions and considerations for each of the four pillars.

| Pillar | Key Questions to Answer | Data Sources & Considerations |

| Scientific Viability | Is the proposed formulation stable and reproducible? Can the manufacturing process be reliably scaled up? Are the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and all necessary excipients readily available and affordable? Are there any significant chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) challenges? 10 | Feasibility studies, supplier audits, preliminary formulation work, cost-of-goods analysis, freedom-to-operate analysis on manufacturing processes. |

| Medical Viability | Does the product address a clearly defined and significant unmet medical need? Does the modification offer a meaningful clinical advantage (e.g., improved efficacy, better safety/tolerability, enhanced patient convenience or compliance)? Is the risk/benefit profile favorable compared to the RLD and other existing treatments? 10 | Clinical literature review, key opinion leader (KOL) interviews, patient advocacy group consultations, analysis of RLD’s adverse event profile, human factors studies. |

| Regulatory Viability | Is there a clear and appropriate RLD to reference? Is there sufficient public data (literature, FDA reviews) available to support reliance? What is the most likely bridging strategy (e.g., PK/BE, nonclinical, clinical)? What is the potential to obtain valuable market exclusivity (3, 5, or 7 years)? 10 | FDA Orange Book analysis, comprehensive literature search, gap analysis of available data, precedent analysis of similar 505(b)(2) approvals, patent landscape review. |

| Commercial Viability | Is there a commercially viable market and patient population for the product? What is the current and future competitive landscape (branded, generic, and pipeline)? How will payers perceive the product’s value? What is the likely reimbursement status and pricing potential? Can we generate the evidence needed to secure favorable formulary access? 10 | Market research, sales data analysis for the RLD, competitive intelligence (e.g., from DrugPatentWatch), early payer research and advisory boards, budget impact modeling. |

By systematically vetting every potential candidate against these four pillars, a company can dramatically increase its probability of success. This disciplined approach ensures that resources are focused only on those opportunities that are not only scientifically sound and regulatorily feasible but also medically necessary and commercially viable. It transforms candidate selection from a speculative exercise into a strategic, value-driven business process.

Part III: The Clinical Gauntlet: Designing Trials for 505(b)(2) Success

Building the Scientific Bridge: The Art and Science of Bridging Studies

The entire strategic advantage of the 505(b)(2) pathway rests on a single, pivotal concept: the “bridge.” A bridging study is the scientific and clinical evidence that connects your proposed new drug product to the existing data of a previously approved Reference Listed Drug (RLD).13 Its purpose is to scientifically justify your reliance on the RLD’s established safety and efficacy profile, allowing you to bypass the need to conduct a full, stand-alone development program. Designing an efficient and successful bridging strategy is therefore the most critical task in 505(b)(2) clinical development.

The nature of the required bridge depends entirely on the differences between your product and the RLD. The goal is to generate just enough new data to address the questions raised by your modifications. Bridging studies typically fall into three categories :

- Clinical Pharmacology (PK/BE) Studies: This is the most common and often sufficient type of bridging study. A pharmacokinetic (PK) study measures how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes a drug. A bioavailability/bioequivalence (BA/BE) study compares the rate and extent of absorption of your new product against the RLD. For two products to be considered bioequivalent, the 90% confidence interval for key PK parameters like maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) must fall within the range of 80% to 125%.

A crucial distinction must be made here. For a 505(j) generic ANDA, demonstrating bioequivalence is a strict requirement. For a 505(b)(2) application, however, the product does not necessarily have to be bioequivalent to the RLD. A difference in bioavailability might be the very point of the innovation (e.g., a new formulation designed for faster absorption or longer duration). In such cases, the PK study serves to quantify this difference, which must then be supported by additional nonclinical or clinical data to demonstrate that the new exposure profile remains safe and effective. - Nonclinical Studies: These studies, conducted in animals or in vitro, may be required to support the bridge when PK data alone is insufficient. Common triggers for nonclinical studies include the use of novel excipients that have not been previously used in an approved product of the same administration route, or if the new formulation results in significantly higher systemic exposure (Cmax or AUC) than the RLD. In the latter case, new toxicology studies may be needed to establish an adequate margin of safety at the higher exposure level.24

- Clinical Safety and Efficacy Studies: While the goal is to avoid large Phase 3 trials, new clinical studies are sometimes necessary. This is often the case when the proposed product is for a new indication or a new patient population not covered by the RLD’s label. For example, if you are repurposing a drug approved for adults for a pediatric indication, you will almost certainly need to conduct new efficacy and safety studies in children. Limited clinical studies may also be needed if your product is not bioequivalent and the difference in exposure raises questions about efficacy that cannot be addressed otherwise.

The critical importance of a robust and well-executed bridging strategy cannot be overstated. A flawed bridge can lead to significant delays or even outright rejection. A stark example is the initial submission for Neos Therapeutics’ methylphenidate extended-release orally disintegrating tablets (XR-ODT). The FDA issued a Complete Response Letter, citing a primary deficiency: the lack of an adequate bridge between the formulation used in the pivotal clinical trial and the final, to-be-marketed commercial formulation. This forced the company to conduct additional bioequivalence studies to link the different formulations, delaying approval and underscoring the need for meticulous planning and execution of the entire bridging package.

Beyond the Standard: Innovative Trial Designs to Demonstrate Value

In the competitive world of 505(b)(2) development, simply achieving regulatory approval is not the finish line; it is merely the price of entry. The ultimate commercial success of your product will depend on your ability to convince payers and physicians that your modification offers a meaningful value that justifies its use—and often its premium price—over the established RLD and its low-cost generic alternatives. A simple bioequivalence study might be sufficient for the FDA, but it does nothing to build this crucial value proposition.

Therefore, you must view your clinical development program not just as a regulatory hurdle, but as your primary marketing and market access tool. The data you generate must be strategically designed to provide the evidence that directly supports your core claims of differentiation and superiority. This requires moving beyond standard trial designs and embracing innovative approaches that can efficiently and powerfully demonstrate your product’s unique worth.

- Adaptive Designs: An adaptive trial design allows for pre-specified modifications to the trial’s parameters based on accumulating data from subjects in the trial itself.8 For a 505(b)(2) product, this could mean starting with several dose levels of a new formulation and, based on interim PK or safety data, dropping less promising arms and focusing enrollment on the optimal dose. This approach can make trials faster, more efficient, and more likely to yield a positive result compared to a traditional fixed design.

- Master Protocols: While often associated with oncology and NME development, the principles of master protocols (basket, umbrella, and platform trials) can be adapted for 505(b)(2)s.28 For instance, a sponsor developing several different modified-release formulations of the same active ingredient could use a platform trial design. This would allow all formulations to be tested simultaneously against a single, shared placebo or active comparator arm, dramatically reducing the number of patients and the time required compared to running separate, parallel trials.

- Real-World Evidence (RWE): The FDA’s increasing acceptance of RWE creates a powerful opportunity for 505(b)(2) developers. RWE is clinical evidence derived from the analysis of real-world data (RWD), such as electronic health records (EHRs), insurance claims data, and patient registries. For a 505(b)(2) seeking a new indication (repurposing), RWE could be used to characterize the natural history of the disease or to serve as an external control arm for a single-arm trial, potentially obviating the need for a large, randomized controlled trial. It can also provide invaluable data on how a product is used in a real-world setting, which is highly compelling to payers.

- Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs): This is arguably the most critical and underutilized tool for demonstrating the value of a 505(b)(2) product. A PRO is any report of a patient’s health status that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation by a clinician.32 If your new formulation’s value proposition is centered on the patient experience—for example, it’s more convenient, easier to use, causes fewer bothersome side effects, or improves quality of life—then PROs are the only way to scientifically

prove it. Data showing your new oral film formulation leads to higher patient-reported satisfaction and adherence compared to a large, hard-to-swallow tablet is far more powerful for a payer than simple BE data.

The strategic imperative is to reverse-engineer your clinical plan from your desired commercial outcome. Start by defining the key claims you want to make on your label and in your marketing materials. Then, design a clinical program that explicitly generates the high-quality evidence needed to support those claims. This transforms the clinical trial from a cost center into a value-creation engine.

The Pre-IND Meeting: Your Most Important Negotiation

For a sponsor pursuing the 505(b)(2) pathway, the pre-Investigational New Drug (pre-IND) meeting with the FDA is not a formality; it is the most important negotiation in the entire development program.13 Unlike a 505(b)(1) program where the development path is relatively standardized, the success of a 505(b)(2) hinges on gaining the FDA’s agreement on a streamlined, abbreviated plan. The entire value proposition of reduced time, cost, and risk can be won or lost in this single interaction.

The strategic objective of the pre-IND meeting is clear: to present your proposed development plan and gain the agency’s input and, ideally, its concurrence on the studies, the CMC strategy, and the clinical research plans in a way that minimizes the number of new studies required. Achieving this objective requires meticulous preparation.

- Do Your Homework: Before even requesting a meeting, you must conduct an exhaustive literature review and a formal gap analysis. This involves systematically identifying all available public data on the RLD and comparing it against the data required for your proposed label. This analysis will reveal precisely what information can be leveraged and what gaps must be filled with new studies.

- Build a Scientific Rationale: You cannot simply propose to skip studies. You must develop a robust, scientifically sound justification for your proposed bridging strategy. This rationale must clearly explain why reliance on the RLD’s data is appropriate and how your planned studies will adequately address any differences between your product and the RLD.

- Prepare a Comprehensive Briefing Package: The briefing package sent to the FDA ahead of the meeting is your primary tool of persuasion. It must be clear, concise, and comprehensive. It should lay out your full development plan, including the proposed RLD, the complete CMC strategy, the detailed bridging plan, and the protocols for any new studies you believe are necessary. Crucially, it must end with a list of specific, well-articulated questions for the agency. Vague questions will receive vague answers.

- Anticipate Key Discussion Points: Be prepared to discuss several critical topics in detail. The CMC plan is paramount, as the FDA expects that the materials used in your initial clinical studies (often Phase 1 BE studies) are representative of the final commercial manufacturing process. This means a significant amount of CMC work must be completed before the first human study. You must also be prepared to defend your choice of RLD and every aspect of your proposed bridging strategy.

A successful pre-IND meeting provides a clear roadmap for development, aligns expectations with the FDA, and significantly de-risks the program, making it far more attractive to investors. An unsuccessful meeting can lead to a request for additional, costly studies, erasing the inherent advantages of the 505(b)(2) pathway. The investment in thorough preparation for this pivotal negotiation will pay dividends throughout the entire product lifecycle.

Part IV: The Generic Frontier: 505(b)(2) and the New Launch Strategy

Beyond Commoditization: The Rise of the “Super-Generic”

The traditional generic drug market, governed by the 505(j) pathway, has been a resounding success for public health, saving the U.S. healthcare system trillions of dollars. However, for the manufacturers themselves, it has become a victim of its own success. The market is characterized by intense competition, with numerous players entering as soon as patents expire. This dynamic leads to rapid and severe price erosion, transforming once-profitable drugs into low-margin commodities.5

In this challenging environment, astute generic and specialty pharmaceutical companies are evolving their strategies. They are moving beyond pure imitation and embracing a new model of innovation centered on creating “super-generics” or “value-added medicines.” These are not simple copies; they are improved, differentiated versions of off-patent drugs that offer tangible benefits in areas like efficacy, safety, or patient compliance.36 The 505(b)(2) pathway is the primary regulatory engine driving this evolution.

This is not a niche strategy; it is a major and rapidly growing commercial market. The global super-generics market was valued at approximately $84 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to $200 billion by 2035, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of over 8%. This growth is fueled by patent expirations on blockbuster drugs, increasing pressure on healthcare systems to find value, and the strategic desire of manufacturers to escape the commoditization trap.

The competitive advantages of these value-added medicines over traditional generics are substantial :

- Product Differentiation: They compete on value and clinical benefit, not just price.

- Higher Profit Margins: Their unique features can command a premium price over standard generics.

- Market Exclusivity: Unlike most generics, they are eligible for their own periods of FDA-granted market exclusivity (typically 3 years), providing a protected window to establish market share and recoup investment.36

By leveraging the 505(b)(2) pathway, companies can transform an off-patent molecule into a new, proprietary, and commercially valuable asset, creating a powerful and sustainable engine for growth that sits comfortably between the high risk of NME development and the low margins of traditional generics.

The High-Stakes Game of Paragraph IV Patent Challenges

The Hatch-Waxman Act was a masterstroke of legislative balancing. While it created the 505(j) pathway to accelerate the entry of low-cost generics, it also established a powerful mechanism to ensure that weak or invalid patents do not unduly block that competition: the Paragraph IV patent challenge.35 For generic companies, mastering this high-stakes legal and regulatory game is one of the most direct routes to significant financial reward.

When a generic company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), it must make a certification for each patent listed for the brand-name drug in the FDA’s “Orange Book.” A Paragraph IV (PIV) certification is a bold declaration by the generic applicant that, in its opinion, the brand’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the proposed generic product.34 This filing is legally considered an “artificial act of infringement,” which sets in motion a highly structured and timeline-driven process.

Understanding this process is like understanding the rules of a complex board game, where each move has a specific consequence. The game unfolds as follows:

- The Filing: The generic company submits its ANDA to the FDA containing the PIV certification.

- The Notice: Within 20 days of the FDA accepting the ANDA for review, the generic firm must send a detailed “Notice Letter” to the brand company and the patent holder, explaining the basis for its challenge.

- The 45-Day Clock: Upon receiving the Notice Letter, the brand company has a critical 45-day window to file a patent infringement lawsuit against the generic applicant.40

- The 30-Month Stay: If the brand company files suit within that 45-day window, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay of FDA approval for the generic ANDA.40 This is a powerful defensive tool for the brand, providing up to two and a half years of continued market exclusivity while the patent litigation proceeds, regardless of the ultimate outcome.

- The Grand Prize: The first generic company to submit a “substantially complete” ANDA with a PIV certification becomes eligible for a coveted prize: 180 days of market exclusivity.34 If they prevail in the litigation (or the patent expires), the FDA will grant them final approval, and for the next six months, no other generic version of the drug can be approved.

This 180-day exclusivity period is the holy grail of generic strategy. It creates a temporary duopoly between the brand and the first generic, allowing the generic entrant to capture significant market share at a price that is only moderately discounted from the brand (often 15-25% less). The profit margins during this period are vastly higher than in the subsequent, fully commoditized market where multiple generic competitors can drive prices down by 80-90% or more. For a blockbuster drug, this six-month window can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, making the risk and expense of litigation a worthwhile gamble.

The following table summarizes the strategic chess match of the PIV process from both perspectives.

| Step | Description | Timeline | Strategic Implication for Generic Filer | Strategic Implication for Brand Company |

| 1. PIV ANDA Filing | Generic company submits ANDA challenging brand patents. | At filer’s discretion (subject to NCE rules). | Initiates the process. Establishes priority for potential 180-day exclusivity. | Puts patents at risk. Starts the clock on a potential loss of exclusivity. |

| 2. Notice Letter | Filer notifies brand company of the PIV challenge. | Within 20 days of FDA acceptance. | Formally begins the legal confrontation. | Triggers the 45-day window to respond with litigation. |

| 3. Litigation Decision | Brand company decides whether to sue for patent infringement. | Within 45 days of receiving notice. | A lawsuit is expected and factored into the strategy. No lawsuit means a faster path to approval. | Suing is the only way to trigger the 30-month stay. A critical defensive move. |

| 4. 30-Month Stay | FDA is barred from approving the ANDA. | Begins when lawsuit is filed; lasts up to 30 months. | A calculated delay. The filer uses this time to litigate the case and prepare for launch. | Guarantees up to 2.5 years of additional revenue, providing time to execute lifecycle management strategies. |

| 5. Resolution & Exclusivity | Litigation is resolved or patents expire. | Varies (2-3 years for full litigation). | If successful, the first filer gains 180 days of highly profitable market exclusivity. | A loss in court leads to immediate generic entry and rapid revenue decline. |

Navigating this complex process requires deep legal expertise and, critically, robust business intelligence. Companies must systematically monitor the patent landscape to identify high-value opportunities where patents may be vulnerable. This is where specialized patent intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch become indispensable tools. Such services provide the detailed, real-time data on patent expirations, new patent listings, and ongoing PIV challenges that are essential for identifying targets, assessing the competitive landscape, and making informed, data-driven decisions about which high-stakes games to play.35

Integrating 505(b)(2) and PIV into a Cohesive Portfolio Strategy

The most sophisticated pharmaceutical companies, whether they originate from the branded or generic side of the industry, do not view their development and launch strategies in silos. They recognize that the 505(b)(2) pathway and the Paragraph IV challenge are not mutually exclusive options but are, in fact, two sides of the same strategic coin. Both are powerful mechanisms designed to circumvent a brand’s full, patent-protected market lifecycle to achieve an earlier, more profitable, or more differentiated market entry.

A truly robust portfolio strategy involves managing a balanced collection of opportunities across the risk-reward spectrum :

- Low-Risk / Lower-Reward: These are the traditional 505(j) generic launches that occur after all relevant patents and exclusivities have expired. They are predictable but subject to immediate and intense price competition.

- High-Risk / High-Reward: These are the first-to-file Paragraph IV challenges against blockbuster drugs. The potential payoff from 180-day exclusivity is enormous, but the litigation costs are substantial, and the outcome is uncertain.

- Moderate-Risk / Moderate-Reward: This is the domain of the 505(b)(2) value-added medicine. The development and regulatory risk is lower than for an NME, and the commercial reward is typically higher and more sustainable than for a standard generic.

The real strategic genius lies in creating synergy between these approaches. A PIV challenge can be viewed as a direct legal assault on the brand’s patent fortress, aiming to breach the walls through litigation. A 505(b)(2) development, in contrast, is a strategic flanking maneuver. It seeks to go around the fortress by creating a new, improved product that may not infringe the brand’s core patents or can create its own new intellectual property.

A forward-thinking company will integrate these strategies in several ways:

- Cross-Funding: The stable, predictable cash flow from a portfolio of standard generics and the higher-margin revenue from successful 505(b)(2) products can be used to fund the expensive, high-risk PIV litigation efforts.

- Leveraging Technical Expertise: The formulation science and clinical development expertise required to create a differentiated 505(b)(2) product are the same skills needed to “design around” a brand’s patents to support a non-infringement argument in a PIV case.

- Creating Strategic Options: When evaluating a target molecule, the most advanced companies assess it for both PIV and 505(b)(2) potential simultaneously. They might initiate a PIV challenge as their primary strategy (“Plan A”) while concurrently beginning early formulation work on a 505(b)(2) version as a “Plan B.” If the PIV litigation falters, or if another company secures first-to-file status, they can pivot to the 505(b)(2) program, ensuring they still have a path to a valuable, proprietary asset.

This integrated approach transforms the company from a one-dimensional player into a multi-faceted strategic competitor, capable of challenging the market from multiple angles and maximizing the value extracted from every molecule in its portfolio.

Part V: From Approval to Access: Winning in the Real World

The Payer’s Perspective: “Show Me the Value”

In today’s healthcare environment, securing FDA approval is no longer the final victory; it is merely the ticket to enter the next, and arguably more challenging, arena: the battle for market access. The ultimate gatekeepers to commercial success are no longer just regulators and physicians, but the payers—the public and private insurance companies that control formularies and reimbursement. For a 505(b)(2) product, which often carries a premium price over its generic RLD, navigating the payer gauntlet is the defining challenge.

When a 505(b)(2) developer approaches a payer, the conversation is not about regulatory pathways; it is about value. Payers are laser-focused on a core set of tough questions :

- Is the Clinical Benefit Meaningful? Is the claimed improvement over the RLD—be it in efficacy, safety, or convenience—clinically significant and relevant to patient outcomes, or is it merely a marginal “tweak”?

- Does It Justify the Cost? In a therapeutic category that is already or soon-to-be genericized, why is the increased cost of the 505(b)(2) product necessary? What is the tangible economic or clinical benefit that justifies not using the low-cost alternative?

- Does It Solve a Real Problem? Does the product address a genuine unmet medical need for a specific patient population, or is it a solution in search of a problem?

Failure to provide convincing answers to these questions can lead to disastrous commercial outcomes, including outright denial of coverage, placement on a non-preferred formulary tier with high patient co-pays that suppress uptake, or a demand to return in 6-12 months after the product has “market experience”—a crippling delay for any new launch.46

This challenge has been significantly compounded by recent shifts in the reimbursement landscape, particularly concerning the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), or J-codes, used for billing physician-administered drugs. Historically, many 505(b)(2) products were grouped under the same J-code as their RLD. However, a pivotal 2022 policy shift by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) established that 505(b)(2) products that are not deemed therapeutically equivalent to their RLD will be considered “sole-source” drugs and receive their own unique J-code.48

This change is a double-edged sword. On one hand, a unique J-code allows the manufacturer to set their own Average Sales Price (ASP), freeing them from the pricing of the genericized RLD. On the other hand, it creates immense administrative complexity and confusion for providers, health systems, and payers, leading to potential miscoding, billing errors, and claim denials.50

To overcome these hurdles, a robust Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR) strategy is not optional; it is imperative. Companies must proactively generate the evidence that demonstrates their product’s value in the language that payers understand. This includes conducting cost-effectiveness analyses, budget impact models, and leveraging real-world evidence (RWE) and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to prove that the clinical benefits of the 505(b)(2) product translate into real-world value for the healthcare system.

Case Studies in 505(b)(2) Success

The theoretical advantages of the 505(b)(2) pathway are best understood through the lens of real-world products that have successfully navigated the path from concept to commercialization. These case studies illustrate the spectrum of strategies and the importance of aligning the product’s modification with a clear and compelling value proposition.

Case Study 1: Bendeka® (bendamustine HCl) – The Efficiency Play

- The Differentiating Feature: The Reference Listed Drug, Treanda®, was an anti-cancer agent supplied as a lyophilized powder that required a complex and time-consuming reconstitution process prior to intravenous (IV) administration. Bendeka® was developed as a ready-to-use, low-volume IV solution in a different solvent, addressing a significant real-world pharmacy workflow and administration burden.

- The Clinical Strategy: This was a model of 505(b)(2) efficiency. The sponsor did not need to conduct new large-scale efficacy trials. The core of the strategy was a single clinical pharmacology study demonstrating that Bendeka® had comparable bioavailability to Treanda®. This study served as the scientific bridge, allowing the application to rely on the FDA’s previous findings of safety and efficacy for the RLD.

- The Value Proposition: The value was not in superior efficacy, but in operational efficiency and safety. The ready-to-use formulation reduced pharmacy preparation time, minimized the risk of dosing errors, and was compatible with certain closed-system transfer devices, a noted limitation for Treanda®. It solved a tangible problem for oncology infusion centers.

Case Study 2: Valtoco® (diazepam) – The Patient-Centric Innovation

- The Differentiating Feature: The RLD, Diastat®, was a diazepam formulation delivered as a rectal gel for the acute treatment of seizure clusters. While effective, this route of administration was invasive, inconvenient, and socially stigmatizing for patients and caregivers. Valtoco® was developed as a nasal spray, utilizing Intravail® technology to enhance absorption across the nasal mucosa.

- The Clinical Strategy: The program focused on demonstrating reliable drug delivery and safety. It included an open-label PK and safety study to characterize absorption during and between seizures, and a long-term safety study. Efficacy could be inferred by bridging to the well-established efficacy of diazepam.

- The Value Proposition: This was a transformative improvement in patient care. Valtoco® offered a portable, non-invasive, ready-to-use rescue treatment that could be administered easily and discreetly by a caregiver or even the patient themselves in a public setting. It addressed a profound unmet need for a more dignified and practical solution, commanding a premium in the market.

Case Study 3: Jornay PM® (methylphenidate HCl) – The Problem-Solving Formulation

- The Differentiating Feature: Most extended-release stimulants for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are dosed in the morning. A common and significant challenge for parents is managing their child’s symptoms during the chaotic early morning routine before the medication takes effect. Jornay PM® is the first and only ADHD treatment designed for once-nightly dosing. It uses a novel formulation with delayed-release and extended-release beads, so the medication is taken at bedtime and begins working upon awakening, providing symptom control through the morning and the rest of the day.

- The Clinical Strategy: Because this was a novel dosing paradigm, the clinical program was more extensive than a simple BE study. It included two Phase 3 safety and efficacy studies to prove the clinical benefit of this new approach, in addition to Phase 1 PK studies.

- The Value Proposition: Jornay PM® did not just offer convenience; it solved a specific, well-defined, and highly frustrating problem for patients and their families. This targeted solution created a unique and defensible niche in the crowded ADHD market.

Case Study 4: Sustol® (granisetron) – The Complex Development Path

- The Differentiating Feature: Sustol® was developed as an extended-release subcutaneous injection for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, aiming to provide coverage for both acute and delayed phases with a single dose. It utilized a novel polymer technology to achieve this sustained release, differentiating it from the IV RLD, Kytril®.

- The Clinical Strategy: The use of a novel polymer and a different route of administration meant this was a far more complex 505(b)(2) program. It required a large and robust development plan, including extensive nonclinical safety evaluations of the new polymer and a significant clinical program to establish the new PK profile, safety, and efficacy. The program more closely resembled a 505(b)(1) in its scope and complexity.

- The Value Proposition: While the development was challenging, the end product offered a clear benefit: multi-day protection from a single injection, improving convenience and compliance for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. This case demonstrates that the 505(b)(2) pathway can accommodate highly innovative and complex science, but the development burden will be commensurate with the degree of deviation from the RLD.

Global Ambitions: The 505(b)(2) and International Equivalents

In our increasingly globalized pharmaceutical market, a successful drug development strategy cannot be confined to a single country. While this report focuses on the U.S. FDA’s 505(b)(2) pathway, it is crucial for companies with international ambitions to understand its counterparts in other major markets, most notably the European Union.

The closest equivalent to the 505(b)(2) pathway in Europe is the Hybrid Marketing Authorisation Application, governed by Article 10(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC.54 The core principle is strikingly similar: it is designed for medicinal products whose active substance is that of an authorized reference medicinal product, but which differ from that reference product in ways such as strength, therapeutic indications, or pharmaceutical form. Like the 505(b)(2), the hybrid application allows the applicant to rely in part on the data from the reference product’s dossier, supplemented by the results of new preclinical tests and clinical trials to cover the differences.

Despite their shared philosophy, there are important nuances and differences that can impact a global development strategy 56:

- Data Requirements: While the principles are similar, specific data requirements can differ. For example, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) may have different or more stringent requirements for certain bridging studies, such as sometimes requiring steady-state bioequivalence studies for extended-release products, which may not always be required by the FDA.

- Review Timelines: Historically, the FDA’s review times have often been shorter than the EMA’s, partly due to greater use of expedited review programs and a more streamlined administrative process post-scientific opinion. This can affect global launch sequencing.

- Regulatory Interpretation: The two agencies may interpret data differently or place emphasis on different aspects of the submission. What constitutes a sufficient “bridge” for the FDA may require additional justification or data for the EMA.

The key strategic implication is the need for early and integrated global planning. Rather than developing a product solely for the U.S. market and then attempting to adapt the data package for Europe, a company should consider the requirements of both the FDA and the EMA from the very beginning of the development process. By designing a single, robust clinical program that is powered to meet the evidentiary standards of both agencies, a sponsor can maximize efficiency, reduce the risk of needing to conduct duplicative or country-specific studies later, and streamline the path to simultaneous or closely sequenced launches in the world’s two largest pharmaceutical markets.

Part VI: Conclusion and Future Outlook

Key Takeaways for the C-Suite

As we’ve explored, the 505(b)(2) pathway and its associated strategies are not merely tactical tools but are central to building a competitive and sustainable pharmaceutical enterprise in the 21st century. For senior executives charting the course for their organizations, the following key takeaways should serve as guiding principles for action and investment.

- Embrace the 505(b)(2) as a Core Portfolio Strategy. View 505(b)(2) assets not as one-off opportunities but as an essential component of a diversified portfolio. They are a crucial tool for de-risking your pipeline, generating mid-term revenue, and providing the financial stability needed to fund higher-risk, long-term innovation in your 505(b)(1) programs.

- Recognize that “Differentiation” is a Regulatory Mandate. The 505(b)(2) pathway is a regulatory necessity, not a choice, for any modified drug that is not a direct generic copy. The FDA will not allow a simple duplicate to use this pathway. This means your innovation must be meaningful enough to justify the 505(b)(2) route, a fact that should guide your entire R&D focus toward value-added medicines.

- Make Payer Viability a Day-One Priority. The single biggest threat to a 505(b)(2) product’s success is a failure to secure market access. Your candidate selection process must be a holistic, four-pillar assessment (Scientific, Medical, Regulatory, Commercial), with payer viability and reimbursement potential evaluated rigorously from the very beginning, long before significant capital is committed.

- Weaponize Your Clinical Trial Program. Your clinical trial design is your primary marketing and value-demonstration tool. It must be strategically engineered to generate the specific evidence—especially Patient-Reported Outcomes and real-world data—that proves the clinical and economic value of your product’s modification to skeptical payers and busy clinicians.

- Integrate Your Offensive and Defensive Strategies. Treat your 505(b)(2) development and Paragraph IV litigation strategies as two sides of the same coin. When evaluating a target molecule, assess its potential for both a direct legal challenge (PIV) and a strategic flanking maneuver (505(b)(2)). The most agile competitors are proficient at both.

- Plan for Market Access as Diligently as You Plan for FDA Approval. FDA approval is the start, not the end, of the commercialization journey. A proactive market access strategy, supported by a robust Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR) plan, is absolutely essential for navigating the complex reimbursement landscape and achieving commercial success in a payer-dominated world.

The Future of Value-Added Innovation

The strategic importance of the 505(b)(2) pathway is only set to grow as several key trends converge to reshape the pharmaceutical landscape. The future of value-added innovation will be driven by data, technology, and an ever-increasing focus on patient-centricity.

We anticipate a much greater role for Real-World Evidence (RWE) in supporting 505(b)(2) applications. As data from electronic health records, claims databases, and patient registries become more robust and accessible, they will offer a powerful and cost-effective means to support new indications, characterize patient populations, and demonstrate a product’s real-world effectiveness, reducing the reliance on traditional, expensive clinical trials.

Simultaneously, the proliferation of digital health tools—from wearables and biosensors to mobile health apps—will revolutionize the collection of Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs). These technologies will allow for the continuous, real-world measurement of a drug’s impact on a patient’s daily life, function, and quality of life, generating a wealth of data to support claims of improved convenience, tolerability, and overall patient experience.

Furthermore, the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning will accelerate the identification of promising 505(b)(2) candidates. AI algorithms can scan vast databases of scientific literature, clinical trial data, and genomic information to uncover novel drug-disease connections, identifying high-potential repurposing opportunities far more efficiently than human researchers alone.

Finally, the payer landscape will continue to evolve, with an ever-stronger demand for evidence of value. This will make the strategic design of clinical trials and the generation of compelling HEOR data even more critical. The 505(b)(2) products that succeed in the future will be those that can not only demonstrate a clinical improvement but can also prove their value in improving outcomes and reducing the total cost of care. The companies that master this intersection of clinical innovation, regulatory strategy, and value-based evidence will be the leaders of the next generation.

Industry Insight: The Growing Dominance of the 505(b)(2) Pathway

The strategic shift towards value-added medicines is not a future trend; it is a current reality. Analysis of FDA approval data reveals the remarkable growth and importance of the 505(b)(2) pathway. According to one comprehensive review, “Of the over 600 drugs approved via this pathway between 1993 and 2016, many had market exclusivity ranging from 3 to 7 years”. This track record highlights not only the regulatory viability of the pathway but also its immense commercial value, cementing its role as a central pillar of modern pharmaceutical development strategy.

FAQ: Answering Your Critical Questions

1. My company is a traditional generic manufacturer. What are the first three steps we should take to build a 505(b)(2) capability?

Transitioning from a pure 505(j) model to incorporating 505(b)(2) development requires a shift in mindset and capabilities. The first three steps should be:

- Build a Cross-Functional Strategy Team: Assemble a dedicated team that includes not only your regulatory and formulation experts but also new hires or consultants with experience in clinical development, medical affairs, and, most importantly, commercial market access. This team’s first task is to develop the “Four-Pillar” viability framework tailored to your company’s strategic goals.

- Invest in Opportunity Identification: You cannot rely on the same processes used to identify generic targets. Invest in business intelligence tools and personnel focused on identifying unmet medical needs and clinical “pain points” that could be solved by modifying existing drugs. This involves analyzing clinical literature, attending medical conferences, and conducting early-stage research with physicians and payers.

- Start Small with a Pilot Project: Select a relatively low-risk, straightforward 505(b)(2) project as your first endeavor—perhaps a new dosage form or strength with a clear clinical rationale and a well-defined regulatory path. Use this project to build internal processes, establish relationships with clinical research organizations (CROs), and learn the nuances of negotiating with the FDA on a development plan before tackling more complex and costly programs.

2. We have a 505(b)(2) candidate with a clear clinical benefit, but the RLD market is small. How do we build a compelling commercial case?

A small RLD market does not automatically mean a small opportunity for a 505(b)(2). The commercial case should be built on market expansion, not just market share capture. Your strategy should focus on demonstrating how your product’s unique benefits will either:

- Expand the Treated Population: If the RLD’s limitations (e.g., difficult administration, poor tolerability) caused many potential patients to go untreated or abandon therapy, your improved version could bring these patients into the market. Your HEOR model should quantify this previously untapped population.

- Enable Use in a New Setting of Care: For example, if your modification allows a drug that was previously hospital-only to be administered at home, you are creating an entirely new market segment.

- Achieve a Premium Price Based on High Value: For orphan diseases, even a small patient population can support a commercially viable product if the unmet need is severe and the clinical benefit is substantial. The case must be built on the high value per patient, justifying a premium price that makes the overall market attractive.

3. What is the single biggest mistake companies make in their pre-IND meeting for a 505(b)(2), and how can it be avoided?

The single biggest mistake is a lack of preparation, which manifests as an inability to provide a robust, data-driven scientific rationale for the proposed development plan. This often takes the form of asking the FDA “What should we do?” instead of presenting a well-reasoned proposal and asking “Do you agree with our plan?” To avoid this, you must:

- Complete a comprehensive gap analysis before the meeting request.

- Develop a clear, written scientific bridge that justifies every study you propose to skip and every study you propose to conduct.

- Formulate specific, unambiguous questions for the agency in your briefing package.

The goal is to lead the conversation and demonstrate that you have thoroughly considered the scientific and regulatory issues, making it easier for the FDA to concur with your proposed efficient path forward.

4. How does the recent CMS ruling on J-codes change the strategic calculation of whether to pursue therapeutic equivalence (TE) for our 505(b)(2) product?

The CMS ruling fundamentally changes the strategic calculus. Previously, obtaining a TE rating and being assigned to the same J-code as the RLD was often seen as the path of least resistance for reimbursement. Now, the landscape is more nuanced:

- Pursuing TE (and a shared J-code): This strategy positions your product as a direct, substitutable competitor to the RLD and its generics. The advantage is easier operational adoption by health systems and potentially faster formulary acceptance as a “generic.” The disadvantage is that your reimbursement will be tied to the (likely declining) ASP of the multisource RLD. This is a volume-based strategy.

- Forgoing TE (and seeking a unique J-code): This strategy positions your product as a distinct, sole-source branded alternative. The advantage is control over your own ASP and pricing, allowing you to capture the full value of your innovation. The disadvantage is a much higher barrier to market access; you will face significant hurdles with payers and providers who will see you as a new, expensive brand and will need to be convinced of your superior value. This is a value-based strategy.

The decision depends entirely on your product’s clinical differentiation. If the value-add is marginal, a TE/volume strategy may be safer. If the clinical benefit is substantial and demonstrable, a unique J-code/value strategy offers a much higher potential return.

5. Can a Paragraph IV litigation settlement with a brand company impact our ability to launch a separate 505(b)(2) product based on the same molecule?

Yes, potentially and significantly. PIV litigation settlements are complex legal agreements that can have broad implications. A settlement agreement might include clauses that go beyond the specific generic product in the ANDA. For example, it could contain provisions that prevent the generic company from marketing any product containing that specific active ingredient for a certain period, which could block the launch of your 505(b)(2). These types of agreements have come under intense antitrust scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as potential “pay-for-delay” schemes. It is absolutely critical that any PIV settlement negotiations are handled by experienced legal counsel who can carefully scrutinize the language to ensure it does not inadvertently foreclose on your future 505(b)(2) strategic options.

References

- Mastering Strategic Decision-Making in the Pharmaceutical R&D Portfolio – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/decision-making-product-portfolios-pharmaceutical-research-development-managing-streams-innovation-highly-regulated-markets/

- Product Portfolio Management: The Complete Guide | monday.com Blog, accessed August 4, 2025, https://monday.com/blog/rnd/product-portfolio-management/

- Proposal of managerial standards for new product portfolio management in Brazilian pharmaceutical companies – SciELO, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.scielo.br/j/bjps/a/9sBZCkX5BgqZNmNWbnShTLg/?format=pdf&lang=en

- Portfolio Management In Pharmaceutical/Biotechnology R&D, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.wcu.edu/pmi/1994/94PMI368.PDF

- How to Develop a Competitive Edge in Generic Drug Development …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-develop-a-competitive-edge-in-generic-drug-development/

- (PDF) Value-driven project and portfolio management in the pharmaceutical industry: Drug discovery versus drug development – Commonalities and differences in portfolio management practice – ResearchGate, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/31998759_Value-driven_project_and_portfolio_management_in_the_pharmaceutical_industry_Drug_discovery_versus_drug_development_-_Commonalities_and_differences_in_portfolio_management_practice

- Pharmaceutical Portfolio Management: A Complete Primer – Planview, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.planview.com/resources/articles/pharmaceutical-portfolio-management-a-complete-primer/

- Pharma Consulting Frameworks & Methodologies – Umbrex, accessed August 4, 2025, https://umbrex.com/resources/faqs-about-consulting/faqs-about-pharmaceutical-consulting/what-are-some-helpful-frameworks-and-methodologies-used-in-pharmaceutical-consulting/

- Quantitative Methods for Drug Portfolio Optimization – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/quantitative-methods-for-portfolio-optimization/

- FDA’s 505(b)(2) Explained: A Guide to New Drug Applications, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/505b2

- premierconsulting.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/what-is-505b2/#:~:text=The%20provisions%20of%20505(b,developed%20by%20the%20NDA%20applicant.

- Review of Drugs Approved via the 505(b)(2) Pathway: Uncovering Drug Development Trends and Regulatory Requirements – PubMed, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008242/

- What Is 505(b)(2)? | Premier Consulting, accessed August 4, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/what-is-505b2/

- overview of the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway for new drug applications – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/156350/download

- 505(b)(2) vs. 505(j): NDA or ANDA for Your Drug? – Allucent, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/what-difference-between-andas-and-505b2-ndas

- What is the 505(b)(2) Regulatory Pathway? | Allucent, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/what-505b2

- The 505(b)(2) Drug Approval Pathway: A Potential Solution for the Distressed Generic Pharma Industry in an Increasingly Diluted ANDA Marketplace? | Sterne Kessler, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/insights/505b2-drug-approval-pathway-potential-solution-distressed-generic-pharma/

- 505(b)(1) versus 505(b)(2): They Are Not the Same – Premier Research, accessed August 4, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/505b1-versus-505b2-they-are-not-the-same/

- Understand the difference between 505(j), 505(b)(1) and 505(b)(2), accessed August 4, 2025, https://veeprho.com/understanding-difference-between-505j-505b1-and-505b2/

- Understanding the Differences Between 505(j), 505(b)(1), and 505(b)(2) Drug Approval Pathways – Pharma Growth Hub, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pharmagrowthhub.com/post/understanding-the-differences-between-505-j-505-b-1-and-505-b-2-drug-approval-pathways

- The 505(b)(2) Pathway: Unlocking a Hybrid Strategy for Drug …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-505b2-drug-patent-approval-process-uses-and-potential-advantages/

- Why is 505(b)(2) a must-have strategy for your company’s long-term growth, success, and survival?, accessed August 4, 2025, https://witii.us/505b2-a-must-have-strategy/

- Abbreviated Approval Pathways for Drug Product: 505(b)(2) or ANDA? | FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-small-business-industry-assistance-sbia/abbreviated-approval-pathways-drug-product-505b2-or-anda

- 505(b)(2) Bridging Studies| Rho, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.rhoworld.com/505b2-bridging-studies/

- Bridging Studies For 505(b)(2) Approval – Clinical Leader, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/bridging-studies-for-approval-0001

- Chemistry, Manufacturing, And Controls Requirements: Bridging And 505(b)(2), accessed August 4, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/chemistry-manufacturing-and-controls-requirements-bridging-and-505b2/

- CLINICAL REVIEW Application Type NDA, 505(b) (2) Application Number(s) NDA 205,489 Seq 027 Priority or Standard Standard Submit – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/106964/download

- Innovation in Clinical Trial Design White Paper final – EFPIA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.efpia.eu/media/547507/efpia-position-paper-innovation-in-clinical-trial-design-white-paper.pdf

- Advancing innovative clinical trials to efficiently deliver medicines to …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9834420/

- Cracking the Code: Mastering Clinical Trial Design – ncoda, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.ncoda.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cracking-the-Code_Mastering-Clinical-Trial-Design.pdf

- REAL-WORLD EVIDENCE PROGRAM – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/120060/download

- Full article: A call to action to harmonize patient-reported outcomes evidence requirements across key European HTA bodies in oncology – Taylor & Francis Online, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2217/fon-2022-0374

- Real-World Evidence: Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) – Introduction – Rethinking Clinical Trials, accessed August 4, 2025, https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/chapters/conduct/real-world-evidence-patient-reported-outcomes-pros/introduction/

- Paragraph IV Explained – ParagraphFour.com, accessed August 4, 2025, https://paragraphfour.com/paragraph-iv-explained/

- The Regulatory Pathway for Generic Drugs: A Strategic Guide to Market Entry and Competitive Advantage – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-regulatory-pathway-for-generic-drugs-explained/

- From generic drugs to super generics: understanding the differences – Adragos Pharma, accessed August 4, 2025, https://adragos-pharma.com/from-generic-drugs-to-super-generics-understanding-the-differences/

- Super Generics Market Size & Share Revenue Growth 2035, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.rootsanalysis.com/reports/super-generics-market/275.html

- Super Generics Market 2025-2034 Detailed Report – InsightAce Analytic, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.insightaceanalytic.com/report/super-generics-market/2437

- Super Generics Market Trends, Share and Analysis, 2025-2032 – CoherentMI, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.coherentmi.com/industry-reports/super-generics-market

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013–2020, accessed August 4, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- DrugPatentWatch – Business Profile – drugpatentwatch | PRLog, accessed August 4, 2025, https://biz.prlog.org/drugpatentwatch/

- NUCYNTA ER (tapentadol hydrochloride) Drug Profile, 2025 a book, accessed August 4, 2025, https://bookshop.org/p/books/nucynta-er-tapentadol-hydrochloride-drug-profile-2025-nucynta-er-tapentadol-hydrochloride-drug-patents-patent-challenges-litigation-ptab-case/e8b06437b3749d18

- Drug Patent Watch – PR Newswire, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.prnewswire.com/in/news-releases/drug-patent-watch-212131971.html

- Market Access for 505(b)(2) Drugs: Interview … – Premier Research, accessed August 4, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/market-access-for-505b2-drugs-interview-with-us-payers-reveals-a-better-approach/

- Review of Drugs Approved via the 505(b)(2) Pathway: Uncovering …, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/review-of-drugs-approved-via-the-505b2-pathway-uncovering-drug-development-trends-and-regulatory-requirements/

- 505(b)(2) Drugs: New Chaos for Infusion Centers, accessed August 4, 2025, https://jhoponline.com/web-exclusives/505-b-2-drugs

- Understanding Recent Changes to 505(b)(2) Drugs and Reimbursement – Pharmacy Times, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/understanding-recent-changes-to-505-b-2-drugs-and-reimbursement