Introduction: Section 3(d) – India’s Great Patent Gatekeeper

In the intricate and high-stakes world of global pharmaceutical intellectual property, few legal provisions have attracted as much attention, debate, and consternation as Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970. It is far more than a mere clause in a statute; it is a declaration of national policy, a gatekeeper standing at the confluence of innovation, public health, and economic strategy. This provision, unique in its explicit mandate, has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of patent prosecution in India, creating a distinct and challenging environment for innovator companies while simultaneously forging a powerful shield for the country’s formidable generic drug industry.

At its core, Section 3(d) embodies a central tension that defines modern healthcare debates worldwide: how does a nation balance the need to incentivize costly pharmaceutical research and development with the moral and economic imperative to ensure its citizens have access to affordable medicines? While most patent systems address this through the lenses of novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability, India has introduced an additional, formidable filter. The provision explicitly states that “the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance… is not patentable”.2 This simple phrase has become the fulcrum upon which thousands of patent applications have pivoted, often towards rejection.

This report will dissect the multifaceted and evolving role of Section 3(d). It will journey from its politically charged legislative origins in the crucible of India’s integration into the global IP framework to its baptism by fire in the landmark Supreme Court case of Novartis v. Union of India. We will explore how subsequent judicial interpretations have continued to mold its application, expanding its reach and refining its procedural requirements. Furthermore, this analysis will move beyond the courtroom to the front lines of patent prosecution, examining how the Indian Patent Office (IPO) applies this provision in practice—often in surprising and controversial ways.

Ultimately, this analysis will demonstrate that Section 3(d) has evolved from a contentious legal text into a dynamic policy instrument. It actively shapes R&D decisions in global boardrooms, dictates market entry strategies for both innovator and generic firms, and serves as a powerful testament to India’s sovereign commitment to prioritizing public health. For any business professional or legal counsel aiming to navigate the Indian pharmaceutical market, understanding the nuances of this provision is not just an academic exercise; it is a prerequisite for survival and success.

The Crucible of TRIPS: Forging Section 3(d) as a National Safeguard

The story of Section 3(d) is inextricably linked to India’s journey from a self-reliant, generics-driven pharmaceutical market to a key player in the global, TRIPS-compliant intellectual property ecosystem. Its creation was not a quiet legislative refinement but a loud, deliberate act of policy-making designed to preserve a hard-won national advantage in the face of immense international pressure.

From Process Patents to a New World Order

Prior to 2005, India’s patent regime, governed by the Patents Act of 1970, was a catalyst for the rise of its domestic pharmaceutical industry. The 1970 Act deliberately excluded product patents for pharmaceuticals, food, and chemicals. It only recognized process patents, meaning that as long as an Indian company could develop an alternative method of synthesis, it could legally manufacture and sell a generic version of a drug patented elsewhere.4 This legal framework was instrumental in transforming India into the “pharmacy of the developing world,” fostering a generation of companies highly skilled in reverse engineering and cost-effective manufacturing, which in turn dramatically lowered the price of essential medicines globally.

This paradigm shifted dramatically when India joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 and became a signatory to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). A core mandate of TRIPS was the requirement for all member states to provide patent protection for both processes and products across all fields of technology, including pharmaceuticals, for a minimum term of 20 years.4 India was given a transitional period, but by January 1, 2005, it was obligated to amend its patent law to introduce a full-fledged product patent regime.1

This impending change created widespread anxiety. Public health advocates, domestic pharmaceutical companies, and political parties feared that the introduction of product patents would end the era of affordable generics, grant long-term monopolies to multinational corporations (MNCs), and lead to exorbitant drug prices, putting life-saving treatments out of reach for millions.5 It was in this charged atmosphere that the Indian Parliament sought to utilize the “flexibilities” within the TRIPS agreement, such as those affirmed by the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, to design a patent law that was compliant on its face but contained robust safeguards to protect national interests.1 Section 3(d) was to become the most prominent and powerful of these safeguards.

The Mysterious Birth of a Legislative Gatekeeper

The legislative process that produced the final version of Section 3(d) was anything but straightforward. It was a “mysterious and intriguing” affair, marked by intense political negotiations, last-minute changes, and a notable lack of clear legislative guidance.

The initial drafts of the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005, proposed only minor changes to the pre-existing Section 3(d). However, intense lobbying from domestic industry groups like the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance (IPA) and political pressure from the Left Front, which provided crucial support to the ruling government, pushed for much stronger measures to prevent “evergreening”—the practice of extending patent monopolies by obtaining new patents for minor, non-substantive modifications of existing drugs.7

The final, potent version of the clause, with its “enhanced efficacy” requirement and detailed Explanation, appeared almost out of nowhere just a day before the bill was introduced in Parliament. Its authorship was attributed to a retired Supreme Court judge known for his strong anti-patent and pro-public health views. This ad-hoc and politically charged genesis meant that the text was not accompanied by detailed parliamentary reports or definitions clarifying key terms like “efficacy” or “significantly.” This legislative vacuum set the stage for the judiciary to become the primary architect of the provision’s meaning and power.

Dissecting the Text: The Three Limbs and the Crucial Explanation

The final text of Section 3(d) is a carefully constructed legal filter with multiple components. It can be broken down into three main prohibitory “limbs” :

- The New Form Limb: This is the most frequently cited part of the provision. It states that “the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance” is not an invention. This directly targets secondary patents on new salts, polymorphs, or other physical variations of a drug.

- The New Property/New Use Limb: This part bars the patenting of “the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance.” This is aimed at preventing companies from re-patenting an old drug simply because a new therapeutic use for it has been found (a practice common in other jurisdictions).

- The Known Process Limb: This final part excludes “the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant.”

What gives the first limb its true power is the accompanying Explanation. This text clarifies what the law considers to be the “same substance” as a known drug:

“For the purposes of this clause, salts, esters, ethers, polymorphs, metabolites, pure form, particle size, isomers, mixtures of isomers, complexes, combinations and other derivatives of known substance shall be considered to be the same substance, unless they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy”.3

This Explanation effectively creates a legal presumption. When a company files a patent for a new salt or crystal form of a known drug, the Indian Patent Office presumes it to be the same as the original substance. The burden of proof then shifts entirely to the applicant to overcome this presumption by demonstrating a significant enhancement in efficacy. This reversal of the typical burden of proof is a cornerstone of the provision’s strength and a primary reason for its profound impact on pharmaceutical patent prosecution in India.

The Novartis Judgment: Defining “Efficacy” and Drawing the Battle Lines

If the 2005 amendment was the birth of Section 3(d), the Indian Supreme Court’s 2013 judgment in Novartis AG v. Union of India & Others was its coming of age. This landmark case was not merely a patent dispute; it was a global referendum on the limits of intellectual property and a nation’s right to define invention in the context of public health. The Court’s definitive interpretation of “efficacy” became the bedrock of Indian pharmaceutical patent law and sent shockwaves through the global industry, establishing a precedent that continues to govern every patent prosecution in the sector today.

The Battle Over Gleevec

The case centered on Novartis’s blockbuster anti-cancer drug, Gleevec. The active pharmaceutical ingredient is imatinib. Novartis had first patented the free base form of imatinib outside India in the early 1990s. For the drug to be effective when administered orally, the company developed a specific salt form, imatinib mesylate, which was more soluble and bioavailable. Subsequently, Novartis discovered a particular crystal structure of this salt—the beta crystalline form—which it claimed had even better properties, such as improved stability and flow, making it more suitable for manufacturing into a pill.11

In 1998, Novartis filed a patent application in India for this beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate. Following the 2005 amendment, the application was examined and faced a barrage of pre-grant oppositions from generic manufacturers and public health groups. The Indian Patent Office, and later the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB), rejected the patent application, primarily on the grounds that it was barred by Section 3(d). They ruled that the beta crystalline form was a new form of a known substance (imatinib mesylate) and that Novartis had failed to demonstrate any “enhanced efficacy” over this known substance.12

The Core of the Dispute: What is “Efficacy”?

Novartis appealed this decision all the way to the Supreme Court. The central legal question was the meaning of the word “efficacy” in Section 3(d). Novartis’s argument was that the term should be interpreted broadly. They presented evidence that the beta crystalline form had significantly improved properties compared to the original imatinib free base, including a 30% increase in bioavailability—the extent and rate at which the active ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream.11 They contended that such a significant physicochemical advantage should qualify as an “enhancement of the known efficacy.”

The opponents, and ultimately the Supreme Court, disagreed profoundly. The Court embarked on a deep analysis of the legislative history and purpose of Section 3(d), concluding that it was specifically designed to be a higher standard for patentability, a “second tier” filter to prevent evergreening in the crucial field of pharmaceuticals.

The Supreme Court’s Seminal Verdict: “Therapeutic Efficacy”

In its historic judgment delivered on April 1, 2013, the Supreme Court delivered a clear and unequivocal interpretation: for pharmaceutical substances, “efficacy” in Section 3(d) can only mean “therapeutic efficacy”.1

The Court reasoned that the function of a medicine is to treat a disease or produce a therapeutic effect. Therefore, any claimed enhancement in efficacy must relate directly to this function. The judgment made several critical points that now form the guiding principles for examiners and courts:

- Physicochemical Properties are Not Efficacy: The Court explicitly rejected Novartis’s arguments about improved flow properties, thermodynamic stability, and lower hygroscopicity. It ruled that these properties, while potentially beneficial for manufacturing or storage, “have nothing to do with therapeutic efficacy” and are therefore irrelevant for the Section 3(d) analysis.

- Bioavailability is Not a Surrogate for Therapeutic Efficacy: This was the most crucial part of the ruling. The Court held that an increase in bioavailability, while potentially important, does not automatically equate to an enhancement in therapeutic efficacy. It explained that bioavailability is merely a pharmacokinetic property—it measures how much of a drug gets into the body. It does not, by itself, prove that the drug works better to cure the disease.

- The Burden of Proof: The Supreme Court placed a high evidentiary burden squarely on the patent applicant. It stated that if an applicant wishes to rely on increased bioavailability, they must provide concrete evidence that this increase results in a tangible enhancement of the drug’s therapeutic effect on the human body. Novartis, the Court found, had failed to provide any such data linking the 30% increase in bioavailability to a better clinical outcome for leukemia patients.13

The Court’s decision was a masterclass in judicial statecraft. It did not declare secondary patents illegal outright. Instead, by defining “therapeutic efficacy” so narrowly and demanding a high, data-driven evidentiary burden, it created a formidable barrier that is exceptionally difficult for innovators to overcome at the early stage of patent filing. This established a “catch-22”: a company often needs a patent to justify the enormous expense of the clinical trials required to prove enhanced therapeutic efficacy, but under Indian law, it now needs the data from those trials to secure the patent in the first place. This practical dilemma, born from the Novartis judgment, has fundamentally shifted the balance of power in Indian pharmaceutical patent prosecution.

Life After Novartis: The Evolving Judicial Interpretation of Section 3(d)

The Novartis judgment was not the final word on Section 3(d), but rather the beginning of a new chapter in its judicial evolution. In the decade since that landmark ruling, Indian High Courts and the IPAB have continued to refine, clarify, and even expand the provision’s application. This ongoing judicial dialogue has transformed Section 3(d) from a blunt instrument into a more nuanced, though still formidable, legal tool. The trend reveals a clear shift from defining the substance of the law to policing its procedure, ensuring that the IPO’s powerful gatekeeping function is not wielded arbitrarily.

Beyond Pharmaceuticals: The Expansion to Biochemicals

One of the most significant post-Novartis developments was the question of whether Section 3(d)’s stringent efficacy test was confined to pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals, the sectors for which it was primarily intended. The Madras High Court provided a decisive answer in the 2023 case of Novozymes A/S v. The Assistant Controller of Patents & Designs.

The case involved a patent application for a variant of phytase, a biochemical enzyme used in animal feed to improve digestion. The IPO had rejected the application under Section 3(d), arguing the variant was a new form of a known enzyme without enhanced efficacy. Novozymes countered that Section 3(d) should not apply to biochemicals and that, in any case, their enzyme’s improved thermostability constituted enhanced efficacy.

The High Court’s ruling was twofold and highly influential:

- Section 3(d) is Not Limited to Pharmaceuticals: The court noted that the text of the law refers to a “known substance,” not a “known pharmaceutical substance.” Therefore, the provision’s reach extends to other chemical and biochemical inventions.10

- “Efficacy” is Context-Dependent: Echoing the logic of the Supreme Court in Novartis, the High Court held that the test for efficacy must be tailored to the intended function of the product. For a medicine, efficacy is therapeutic. For an industrial enzyme like phytase, efficacy relates to its function in its intended environment. The court accepted that improved thermostability was a valid form of “enhanced efficacy” because it allowed the enzyme to better withstand the high temperatures of the animal feed pelleting process, thereby improving its ultimate effectiveness in aiding digestion.

This judgment was pivotal. It confirmed that Section 3(d) is a broad principle of Indian patent law applicable across chemical arts, but also demonstrated a pragmatic approach, allowing the definition of “efficacy” to adapt to the specific technical field of the invention.

Clarifying the Boundaries: Section 3(d) vs. Section 3(e)

Another area of evolving jurisprudence has been the distinction between Section 3(d) and its neighboring clause, Section 3(e), which bars patents for substances obtained by a “mere admixture” unless they exhibit a synergistic effect. Patent examiners sometimes conflated the two, improperly applying the “enhanced efficacy” test of 3(d) to inventions that were actually combinations under 3(e).

Recent court decisions have put a stop to this. In a July 2025 order, the Calcutta High Court, in Oramed Ltd. v. The Controller General of Patents, overturned a patent refusal where the Controller had rejected a combination under Section 3(e) by demanding data on therapeutic efficacy and bioavailability—hallmarks of a Section 3(d) analysis.18 The court was unequivocal: the two sections are distinct and have different tests. Section 3(d) requires a showing of

enhanced efficacy over a known substance, while Section 3(e) requires a showing of synergism between components of an admixture. The Controller cannot mix and match the criteria.18 This insistence on legal precision prevents the IPO from using a vague, blended objection and forces examiners to apply the correct legal standard to the facts of the case.

The Rise of Procedural Fairness

Perhaps the most significant trend in recent years has been the judiciary’s focus on procedural fairness in the IPO’s application of Section 3(d). Recognizing the provision’s power to summarily reject an application, High Courts have established clear procedural guardrails to prevent its arbitrary use.

In a series of important rulings, such as DS Biopharma Limited v. The Controller of Patents & Designs and Nippon Steel Corporation v. The Controller General of Patents, the Delhi High Court has repeatedly remanded cases to the IPO for reconsideration when examiners issued Section 3(d) objections without proper reasoning.21 The courts have laid down a clear, three-part test that an examiner must satisfy to sustain a Section 3(d) objection:

- Identify the “Known Substance”: The examiner cannot simply assert that an invention is a new form of a known substance. They must specifically identify the prior art compound they are using as the baseline for comparison.22

- Explain the Link: The examiner must provide a clear explanation as to why the claimed invention is considered a derivative or new form of that identified known substance.

- Enable a Comparison: The objection must be framed in a way that allows the applicant to make an objective comparison between the therapeutic efficacy of their invention and that of the known substance.

By mandating this level of detail and reasoning, the courts are ensuring that a Section 3(d) objection is not a mere assertion but a well-founded argument that the applicant has a fair opportunity to rebut. This judicial oversight has introduced a new level of discipline and predictability into the examination process, signaling a maturation of the Section 3(d) jurisprudence from establishing a powerful substantive rule to ensuring its fair and reasoned application.

Inside the Patent Office: Section 3(d) in Practice

While landmark court cases define the legal boundaries of Section 3(d), its true impact is felt daily in the trenches of patent prosecution—in the First Examination Reports (FERs) issued by the Indian Patent Office (IPO). An analysis of the IPO’s practical application of the provision reveals trends that are both expected and, in some cases, deeply surprising, painting a picture of a powerful tool being wielded with increasing frequency and in ways that extend beyond its original legislative intent.

The Rising Tide of Section 3(d) Objections

Empirical studies of FERs issued by the IPO have confirmed what many patent practitioners have experienced firsthand: the use of Section 3(d) as a ground for objection has increased dramatically over time. Research analyzing patent applications filed over a decade shows a sharp upward trend, with the percentage of pharmaceutical applications receiving a 3(d) objection rising from less than 40% in the early 2000s to more than 80% in later years.24 This indicates that the IPO, emboldened by the Supreme Court’s backing in the

Novartis case, has grown more confident in using the provision as a primary examination tool. The data also shows that these objections are increasingly aimed at the heart of the invention—the main claims—further underscoring the provision’s central role in the examination process.

The “Redundancy” Debate: A Belt-and-Suspenders Approach

One of the most consistent findings from analyses of IPO practice is that Section 3(d) is rarely used in isolation. In the vast majority of cases—over 94% according to one study—a Section 3(d) objection is raised alongside traditional objections for lack of novelty (anticipation) or, more commonly, lack of inventive step (obviousness).

This has sparked a debate about whether the provision is truly adding a “second tier” of patentability criteria or is simply being used “redundantly” by examiners. On one hand, this “belt-and-suspenders” approach can be seen as a sign of rigorous examination, where an application is tested against every possible legal hurdle. On the other hand, it makes it difficult to isolate the independent impact of Section 3(d). If an application is rejected for both lacking an inventive step and failing to show enhanced efficacy, which was the decisive factor?

However, the data does provide a clue. Studies have found that applications facing both inventive step and Section 3(d) objections have a significantly lower grant rate than those facing only an inventive step objection. This suggests that even when used in conjunction with other grounds, a Section 3(d) objection adds a distinct and formidable barrier to patentability, one that is particularly difficult for applicants to overcome. It also leads to a more protracted and costly prosecution process, with applications facing 3(d) objections taking, on average, hundreds of days longer to reach a final decision.

The Primary Patent Paradox: A Tool Used Off-Label

Perhaps the most surprising and controversial aspect of the IPO’s application of Section 3(d) is its frequent use against primary patent applications—those claiming a truly new chemical entity (NCE), not a modified form of an existing one.24 This practice appears to directly contradict the provision’s stated purpose, which is to prevent the evergreening of patents for “known substances.” How can a substance that is, by definition, new and not previously known, be a “new form of a known substance”?

This seemingly illogical practice can be understood as a form of “defensive examination” by the IPO. Faced with a high volume of complex pharmaceutical applications and a mandate to uphold a high standard of patent quality, examiners may be using Section 3(d) as a strategic shortcut. A standard inventive step rejection requires the examiner to meticulously identify prior art references and construct a detailed argument for why the invention would have been obvious. In contrast, raising a Section 3(d) objection, especially after Novartis, immediately shifts the burden of proof to the applicant to proactively provide robust data demonstrating the new molecule’s therapeutic value.

In effect, the IPO is using an anti-evergreening tool as a heightened utility or inventive step requirement for NCEs. It is a pragmatic, if legally questionable, strategy to compel applicants to put their best evidence of a genuine therapeutic advancement on the table from the outset. While applicants with truly novel compounds often succeed in arguing that Section 3(d) is not applicable, the practice adds another layer of complexity and cost to the prosecution process and reflects how the provision’s influence has expanded far beyond its textual confines. The recent surge in overall patent grants in India, as reported by WIPO for 2023, must be viewed against this backdrop of a rigorous, and at times unorthodox, examination process that contributes to a lengthy average pendency time of over four years.

A Comparative Perspective: How India’s “Efficacy” Filter Stands Apart

To fully grasp the unique nature of Section 3(d), it is essential to place it in the context of international patent law. While all major patent systems have a mechanism to prevent the grant of patents for trivial inventions, India’s approach is fundamentally different from the standards of “non-obviousness” in the United States and “inventive step” in Europe. Section 3(d) is not merely India’s version of these concepts; it is an additional, substance-focused hurdle that an invention must clear after satisfying the traditional tests of novelty and inventiveness.

This distinction is critical for any company devising a global patent strategy. An invention that easily clears the patentability bar in the US and Europe may falter at the first hurdle in India, not because it is obvious, but because it fails to demonstrate a specific type of functional superiority.

United States: The “Non-Obviousness” Standard

In the United States, the core requirement for inventiveness is “non-obviousness,” codified in 35 U.S.C. § 103. The seminal Supreme Court case, Graham v. John Deere Co., established a factual framework for this analysis, which remains the standard today. To determine if an invention is obvious, an examiner must assess:

- The scope and content of the prior art.

- The differences between the prior art and the claimed invention.

- The level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art.

Against this factual background, the ultimate question is whether the invention as a whole would have been obvious at the time of invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art. The US system also gives significant weight to “secondary considerations” or objective evidence of non-obviousness, such as the commercial success of the invention, a long-felt but unsolved need, or the failure of others to achieve the same result. For a new form of a known drug, a patent might be granted if it exhibits “unexpected results” compared to the prior art. These unexpected results could be improved stability, better bioavailability, or reduced side effects. There is no strict requirement that these results must translate into superior therapeutic efficacy.

Europe: The “Inventive Step” and the “Problem-Solution” Approach

The European Patent Office (EPO) assesses inventiveness under Article 56 of the European Patent Convention, which requires an invention to involve an “inventive step.” The EPO has developed a structured methodology known as the “problem-solution approach” to make this assessment objective. This approach involves three steps:

- Determining the “closest prior art”: Identifying the most relevant single piece of prior art.

- Establishing the “objective technical problem”: Defining the technical problem that the invention solves, based on the technical effect achieved by the distinguishing features of the invention compared to the closest prior art.

- Considering whether the invention was obvious: Asking whether a person skilled in the art, starting from the closest prior art and faced with the objective technical problem, would have arrived at the claimed invention in an obvious manner.29

Like the US system, the focus is on the technical contribution over the prior art. A new crystal form of a drug could be deemed inventive if it surprisingly solves a technical problem, such as poor stability or formulation difficulties, even if it does not offer a better clinical outcome. The key is whether the solution was technically obvious, not whether it was therapeutically superior.

India’s Section 3(d): A Fundamentally Different Question

Section 3(d) operates on a different plane. It presumes that new forms of known substances are not inventions. To overcome this presumption, the applicant must answer a question that the US and European systems do not explicitly ask: Does this new form work better at treating the disease?

The following table crystallizes the fundamental differences in legal philosophy and practical application:

Comparative Analysis of Patentability Standards for Incremental Pharmaceutical Inventions

| Feature | India (Section 3(d)) | United States (35 U.S.C. § 103) | European Patent Office (Art. 56 EPC) |

| Core Principle | Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy | Non-Obviousness | Inventive Step |

| Nature of Test | A substantive eligibility filter for a specific class of invention (new forms of known substances). | A universal test of inventiveness based on the state of the art at the time of invention. | A universal test of inventiveness based on the state of the art. |

| Key Framework | Direct comparison of the new form’s efficacy against the “known substance’s” efficacy. | The Graham Factors: Scope of prior art, differences, level of skill, and secondary considerations. | The Problem-Solution Approach: Closest prior art, objective technical problem, and obviousness of the solution. |

| Primary Focus | The clinical or therapeutic outcome of the invention. | The technical advancement of the invention over the prior art. | The invention as a technical solution to a technical problem. |

| Evidentiary Focus | Requires data demonstrating an improved therapeutic effect. A mere physicochemical advantage is insufficient. | Evidence of “unexpected results,” long-felt need, or commercial success can overcome an obviousness rejection. | Evidence that the claimed solution was not obvious to a person skilled in the art for solving the identified problem. |

This comparison makes it clear why India is considered a global outlier. The Section 3(d) “efficacy” filter is not a substitute for the inventive step analysis; it is a prerequisite. An applicant in India must first prove that their new form of a known substance has enhanced therapeutic efficacy to even be considered an “invention.” Only then will it be subjected to the traditional tests of novelty and inventive step. This additional, outcome-oriented requirement is what makes Indian pharmaceutical patent prosecution a uniquely challenging endeavor.

Strategic Playbook: Navigating the Section 3(d) Gauntlet

The unique legal framework created by Section 3(d) necessitates a tailored and sophisticated strategic approach for any company operating in the Indian pharmaceutical market. The rules of the game are different here, and strategies that succeed in other jurisdictions may be insufficient. For innovator companies, navigating this gauntlet requires a proactive, data-centric approach that integrates R&D and legal strategy from day one. For generic companies, Section 3(d) presents a powerful strategic weapon to challenge patents and accelerate market entry.

For Innovator Companies: Building a Section 3(d)-Proof Application

For innovator companies, success in India requires a paradigm shift. The patenting process cannot be an afterthought to R&D; it must be a core consideration from the earliest stages of development. The goal is to build a patent application that is not just legally sound but is fortified with the specific evidence needed to withstand a Section 3(d) challenge.

The Primacy of Compelling Efficacy Data

The single most critical element for overcoming a Section 3(d) objection is robust, compelling evidence of enhanced therapeutic efficacy.8 The

Novartis judgment made it clear that theoretical advantages or improvements in intermediate properties like bioavailability are not enough. The data must establish a clear and plausible link to an improved clinical outcome. This could include:

- Comparative Clinical Data: While full-scale Phase III trial data is often not available at the time of filing, any available human data, even from early-phase trials, showing a superior therapeutic effect (e.g., faster onset of action, higher response rate, better patient outcomes) is invaluable.

- In Vivo Animal Studies: Well-designed comparative studies in relevant animal models that demonstrate superior therapeutic outcomes can be highly persuasive.

- Data on Reduced Toxicity or Improved Safety Profile: A significant reduction in adverse side effects compared to the known substance can be a powerful argument for enhanced therapeutic efficacy, as improved safety is a direct therapeutic benefit for the patient.

The key is that the data must be comparative. It must directly compare the new form against the “known substance” and demonstrate a significant difference.

Leveraging Post-Filing Evidence

Recognizing that drug development is a lengthy process, the Indian patent system provides a crucial lifeline: the ability to submit additional evidence during prosecution. Sections 57, 59, and 79 of the Patents Act allow applicants to amend specifications and submit evidence via affidavits to support their claims.

The courts have affirmed the importance of this flexibility. In the 2023 case of Oyster Point Pharma Inc v. The Controller of Patents and Designs, the Calcutta High Court overturned a rejection, emphasizing that the IPO must consider efficacy data submitted after the initial filing. The court acknowledged that it may not be possible to provide all data at the time of application and that post-filing evidence is permissible and necessary for a fair evaluation.

This creates a critical strategic timeline for innovators. While the patent application should be filed as early as possible to secure a priority date, a parallel R&D track must be focused on generating the necessary comparative efficacy data. This data can then be strategically introduced during the examination process to rebut a Section 3(d) objection.

Sophisticated Claim Drafting and Strategic Focus

Beyond data, patent strategy begins with the claims themselves. Innovators can proactively design their patenting strategy around concepts more easily defensible under Section 3(d) :

- New Formulations with Clear Benefits: A new sustained-release formulation that reduces dosing frequency from twice-daily to once-weekly has a clear, demonstrable therapeutic benefit in terms of patient compliance and adherence, which can be a strong argument for enhanced efficacy.

- New Routes of Administration: An intranasal spray version of a drug previously only available as an injection offers a significant therapeutic advantage in terms of ease of use and patient comfort.

- Combinations with Synergistic Effects: While primarily governed by Section 3(e), a new combination of drugs that demonstrates synergy resulting in a superior therapeutic outcome can also overcome a Section 3(d) challenge if one of the components is considered a new form.

However, pitfalls remain. As seen in the Ovid Therapeutics case, merely showing increased bioavailability without linking it to a therapeutic benefit will fail. Furthermore, any amendments made to the claims during prosecution must not impermissibly broaden the scope of the invention.

For Generic Companies: Wielding Section 3(d) as a Strategic Weapon

For India’s generic pharmaceutical industry, Section 3(d) is not a barrier but an opportunity. It is the single most powerful legal tool available to challenge the validity of secondary patents and clear the path for the timely launch of affordable generic alternatives.1

The Power of Opposition

The Indian patent system allows for both pre-grant and post-grant oppositions, providing two windows for competitors to challenge a patent’s validity. Section 3(d) is consistently one of the most potent grounds for these oppositions.34 A generic company can proactively monitor innovator patent filings and, upon publication, file a pre-grant opposition arguing that the claimed new form of a known substance lacks evidence of enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

This strategy has been used effectively in numerous high-profile cases. Generic manufacturers like Cipla and Natco Pharma have successfully used Section 3(d) arguments to challenge or revoke patents for major drugs, including Roche’s Tarceva (erlotinib) and Gilead’s Sovaldi (sofosbuvir).34

Shifting the Competitive Landscape

Section 3(d) has fundamentally altered the nature of competition in the Indian market. It is no longer simply about waiting for a 20-year patent term to expire. Instead, the competitive battle begins the moment a secondary patent application is filed. Generic companies have developed sophisticated legal and scientific teams dedicated to scrutinizing these applications, identifying vulnerabilities under Section 3(d), and launching legal challenges.

This transforms patent opposition from a purely legal function into a core business development activity. A successful opposition can invalidate a secondary patent, potentially opening up the market years earlier than expected. This makes the ability to effectively wield Section 3(d) as important to a generic company’s success as its manufacturing and distribution capabilities. It has created a dynamic environment of legal and scientific attrition, where the strength of a patent is constantly tested against India’s uniquely high bar for invention.

Leveraging Competitive Intelligence: The Role of DrugPatentWatch

In the complex and high-stakes environment shaped by Section 3(d), timely and accurate business intelligence is not a luxury; it is a critical necessity. The provision’s inherent uncertainty—whether a patent will be granted, and if so, whether it will withstand a challenge—makes strategic planning incredibly difficult. This is where a sophisticated competitive intelligence platform like DrugPatentWatch becomes an indispensable tool for both innovator and generic companies seeking to gain a competitive edge in the Indian market.

The value of such a platform transcends simple data provision. In the context of Section 3(d), it becomes a predictive analytics tool, allowing companies to transform raw data on patent filings and litigation into actionable strategic insights. By aggregating and analyzing prosecution histories, it becomes possible to model the probability of a patent grant, assess the risk of a Section 3(d) rejection for a specific class of technology, and thereby make more informed R&D, investment, and litigation decisions.

Core Capabilities for the Indian Market

DrugPatentWatch offers a fully integrated database providing business intelligence on both biologic and small molecule drugs. Its services include comprehensive information on international drug patents across more than 130 countries, patent expiration dates, ongoing litigation, API vendors, and formulation details.38 The platform’s global coverage explicitly includes India, allowing users to closely monitor the country’s unique patent landscape.

Strategic Applications for Innovator Companies

For an innovator company planning its Indian patent strategy, DrugPatentWatch can be used to:

- De-risk Filing Strategy: Before filing a patent for a new formulation or polymorph in India, a company can analyze the prosecution histories of similar patents. By tracking how competitors’ applications in the same therapeutic class have fared against Section 3(d) objections, R&D and legal teams can better assess the likelihood of success and determine the level of efficacy data required.43

- Monitor Competitor Activity: The platform allows innovators to set up alerts and watch lists to track the progress of competitors’ patent applications. This provides real-time intelligence on how other companies are arguing against Section 3(d) objections, what kind of evidence they are submitting, and which arguments are succeeding with the IPO.

- Strengthen Patent Applications: By studying the claims and litigation history of previously granted secondary patents, companies can learn how to draft stronger, more defensible claims and build a more robust data package to preemptively address potential Section 3(d) challenges.

Strategic Applications for Generic Companies

For a generic company, DrugPatentWatch is a powerful tool for identifying and capitalizing on market opportunities:

- Identify Vulnerable Patents: The platform can be used to identify blockbuster drugs with patents nearing expiration. More importantly, it allows generics to monitor for the filing of secondary patents (e.g., for new salts, esters, or formulations) intended to extend market exclusivity. These filings are prime targets for a pre-grant opposition based on Section 3(d).40

- Anticipate Market Entry: By tracking patent litigation involving Section 3(d), generic companies can anticipate early market entry opportunities. A successful challenge by one generic company can invalidate a patent for all, opening the market sooner than expected.

- Inform Portfolio Management: Data on which types of secondary patents are most frequently rejected under Section 3(d) can help generic companies prioritize their own development pipeline, focusing resources on products where the innovator’s IP fortress is most likely to crumble.

A New Paradigm for CDMOs and Strategic Partners

The platform’s utility extends to the broader ecosystem, particularly for Indian Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs). As India solidifies its “China Plus One” status, Indian CDMOs are increasingly partnering with global innovators. In this context, IP intelligence shifts from being adversarial to collaborative. An Indian CDMO must be able to conduct thorough freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis to assure its global partner that its manufacturing processes do not infringe on any third-party patents. Using a comprehensive platform like DrugPatentWatch allows a CDMO to map a client’s technology against the competitive IP landscape, identify risks, and transform itself from a mere service provider into a knowledgeable, value-added strategic partner. This capability is essential for commanding higher-value contracts and building resilient, long-term business relationships.

The Broader Impact: Economics, Policy, and Global Perception

The influence of Section 3(d) extends far beyond the confines of the Indian Patent Office and courtrooms. It has generated significant economic ripple effects, shaped domestic industrial policy, and provoked strong reactions on the international stage. The provision is a focal point in the global debate over intellectual property, public health, and the economic development of nations, making it a subject of intense scrutiny from governments, multinational corporations, and public health advocates alike.

The International Response: A Contentious Divide

Internationally, Section 3(d) is viewed through two sharply contrasting lenses. For many developing nations and global health organizations, it is lauded as a pioneering public health safeguard—a model for how to use TRIPS flexibilities to prevent patent abuse and promote access to affordable medicines.1

However, for innovator pharmaceutical companies and their home governments, particularly the United States, the provision is seen as a significant trade barrier that undermines intellectual property rights. This view is most prominently articulated by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) and in the annual Special 301 Report issued by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). For years, the USTR has placed India on its “Priority Watch List,” consistently citing Section 3(d) as a primary concern. The reports argue that the provision’s “restrictions on patent-eligible subject matter” create “major obstacles” for innovators and represent a departure from international norms.48 This sustained international pressure has made Section 3(d) a recurring point of friction in bilateral trade negotiations between India and its major trading partners.

This statistic, highlighted in a recent analysis, underscores the ongoing tension between the law’s intent and its implementation, fueling both domestic calls for stricter enforcement and international criticism of the system’s perceived flaws.

The Tangible Impact on Drug Pricing

One of the most direct and celebrated consequences of Section 3(d) is its role in controlling drug prices. By setting a high bar for secondary patents, the provision facilitates the timely entry of generic competition, which is the most effective mechanism for reducing prices. The Novartis case remains the starkest example: after the Supreme Court’s denial of the patent for Gleevec, generic versions were available in India for approximately $2,500 per year, compared to the patented drug’s price of $70,000 per year in the United States.1 This dramatic price differential has had a life-saving impact for thousands of patients in India and in other developing countries that import Indian generics.

However, it is important to note that while Section 3(d) is a powerful tool, it is not a panacea for India’s complex drug affordability challenges. Many Indians still face high out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures, and pricing for many essential medicines remains a significant concern, influenced by a host of factors beyond patent law.

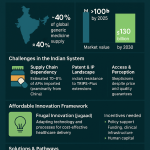

The R&D Investment Conundrum: Stifling or Stimulating Innovation?

The most contentious debate surrounding Section 3(d) revolves around its impact on research and development. Critics, primarily from the innovator industry, argue that the provision’s stringent standards disincentivize investment in India. They contend that by making it difficult to protect incremental innovations—which are often crucial for improving a drug’s safety, delivery, or manufacturing efficiency—the law reduces the potential return on investment and discourages companies from launching new products or conducting clinical trials in the country.1

Proponents and available data paint a more nuanced picture. They argue that Section 3(d) does not stifle innovation but rather directs it towards more meaningful advancements. By filtering out trivial modifications, the law encourages companies to focus on developing genuinely new drugs or making improvements that offer a significant therapeutic benefit.1

Recent trends in R&D spending seem to support this latter view. While overall private sector R&D investment in India still lags behind global peers, spending by leading Indian pharmaceutical companies is on the rise. Companies like Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Sun Pharma, and Biocon are allocating between 6-8% of their revenue to R&D, with a strategic focus on complex areas like biosimilars, specialty generics, and novel drug delivery systems—innovations that are more likely to meet the “enhanced efficacy” standard. A 2010 report by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) also concluded that Section 3(d) had not hampered the growth of the pharmaceutical industry or stifled innovation, noting a significant increase in the number of pharma patents granted post-2005.

This suggests that Section 3(d) may be functioning as an industrial policy tool, creating a bifurcated innovation landscape. It might deter some MNCs from pursuing incremental patent strategies in India, but it simultaneously incentivizes domestic firms to invest in more substantial, “3(d)-proof” R&D to compete not just at home but also in highly regulated global markets. The provision, therefore, may be inadvertently pushing the Indian industry up the value chain, from simple reverse engineering towards more complex and genuinely innovative products.

The Road Ahead: The Future of Section 3(d)

As the pharmaceutical industry stands on the cusp of transformative changes driven by biotechnology and artificial intelligence, the enduring relevance of Section 3(d) is once again in the spotlight. For nearly two decades, its application has been shaped primarily by judicial interpretation rather than legislative amendment. Looking forward, its future will likely be defined by its adaptation to new scientific frontiers and the ongoing debate about whether its “crude” but effective text requires refinement to keep pace with the evolution of medicine.

The Debate on Legislative Reform

Despite its profound impact, Section 3(d) has remained unchanged since its 2005 amendment. There are currently no active, high-profile legislative proposals to alter its text, suggesting a broad political consensus in favor of maintaining the status quo.59 The prevailing view within India is that the provision is a TRIPS-compliant and necessary safeguard for public health.

However, this has not silenced calls for reform from legal experts and academics. Critics argue that the provision, born of a hurried political compromise, is “crudely worded” and contains ambiguities that create legal uncertainty.63 They point to several areas ripe for clarification:

- Defining the “Known Substance”: A clearer statutory definition of the baseline substance against which efficacy is compared could reduce litigation.

- Clarifying the Standard of Proof: The type and quantum of evidence required to prove “enhanced efficacy” remains a grey area, largely defined by case law.

- Refining the Scope: Some have proposed amendments to explicitly state that the provision targets “structurally similar” compounds, which would align it more closely with the scientific basis of obviousness in other jurisdictions.

While a full legislative overhaul seems unlikely in the near future, these critiques may influence future judicial interpretations or prompt the IPO to issue more detailed examination guidelines to bring greater consistency and transparency to the process.

Adapting to Emerging Technologies: The Next Frontier

The greatest challenge—and the most interesting question—for the future of Section 3(d) is how its principles will be applied to the next generation of medicines. The legal framework, conceived in an era of small-molecule chemistry, must now grapple with the complexities of biotechnology and computational drug discovery.

- Biologics and Biosimilars: How does one define “enhanced efficacy” for a biosimilar? Is a change in a glycosylation pattern that leads to a slightly better pharmacokinetic profile but no proven difference in clinical outcome sufficient? The Novozymes case, which applied Section 3(d) to enzymes, provides a precedent for a context-dependent approach, but the scientific complexity of biologics will test the limits of this framework.

- Gene and Cell Therapies: For these revolutionary treatments, what constitutes a “new form of a known substance”? Is a new viral vector for delivering a known gene therapy a “new form”? How would “enhanced efficacy” be measured—by improved transfection efficiency, greater durability of effect, or a better safety profile?

- AI-Driven Drug Discovery: As artificial intelligence becomes more prevalent in designing new molecules, Section 3(d) could take on a new role. If an AI algorithm modifies a known drug scaffold to create a new compound predicted to have higher potency, this new compound could be considered a “new form.” The patentability would then hinge on whether the applicant can provide in vitro or in vivo data to validate the AI’s prediction of enhanced efficacy.9

The future of Section 3(d) will be one of adaptation, not abolition. The core question it asks—”Does this new version offer a real, tangible benefit over what we already have?”—is technology-neutral and arguably more relevant than ever in an age of rapid, iterative innovation. The battleground will shift from the crystal forms of small molecules to the intricate details of biologics and the predictive power of algorithms. This will demand an ever-increasing level of scientific sophistication from India’s patent examiners, lawyers, and judges, ensuring that Section 3(d) remains a dynamic and central feature of the country’s intellectual property landscape for years to come.

Conclusion

Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act is far more than a legal technicality; it is a defining feature of India’s place in the global pharmaceutical order. Born from a desire to balance WTO compliance with a deep-seated commitment to public health, it has evolved through judicial interpretation into a sophisticated gatekeeping mechanism. The landmark Novartis judgment cemented its core principle: in the realm of medicine, true invention must be measured by its therapeutic benefit to the patient.

This high bar for patentability has created a unique and challenging jurisdiction for innovator companies, compelling them to integrate R&D and legal strategies and to come armed with compelling evidence of clinical superiority. Simultaneously, it has empowered India’s generic industry, providing a potent tool to challenge weak secondary patents and ensure the timely arrival of affordable medicines. The provision’s influence has rippled across the globe, sparking international trade disputes and positioning India as a leader among nations prioritizing access to medicine.

While debates surrounding its ambiguities and economic impact will continue, the role of Section 3(d) is set to expand, not diminish. As medicine advances into the complex worlds of biologics and AI-driven discovery, the fundamental question of “enhanced efficacy” will remain central. The future of Section 3(d) will be written not through legislative repeal, but through its continuous adaptation to new scientific frontiers, ensuring it remains a powerful, and uniquely Indian, instrument of industrial and public health policy.

Key Takeaways

- A Unique Public Health Safeguard: Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act is a globally unique provision designed to prevent “evergreening” by prohibiting patents for new forms of known substances unless they demonstrate “enhanced efficacy.”

- “Efficacy” Means “Therapeutic Efficacy”: The Indian Supreme Court’s landmark 2013 ruling in Novartis v. Union of India definitively interpreted “efficacy” for pharmaceuticals as “therapeutic efficacy,” setting a high, data-driven evidentiary bar for patent applicants. Physicochemical advantages like increased bioavailability are insufficient unless proven to result in a better clinical outcome.

- Judicial Interpretation is Key: The scope and application of Section 3(d) have been primarily shaped by the judiciary. Recent court decisions have expanded its application to biochemicals and established strict procedural fairness requirements for the Indian Patent Office (IPO), mandating clear and reasoned objections.

- Dual Impact on Industry: The provision acts as a significant hurdle for innovator companies, requiring a proactive strategy of generating compelling efficacy data. For generic manufacturers, it is a powerful strategic tool used in pre-grant and post-grant oppositions to challenge secondary patents and accelerate market entry.

- Global Outlier with Economic Consequences: Section 3(d) makes India a challenging jurisdiction for IP protection, drawing consistent criticism in the USTR’s Special 301 Report. However, it has been instrumental in keeping drug prices low and may be stimulating a shift in domestic R&D towards more substantial, “3(d)-proof” innovations.

- Future-Proof Principle: The core principle of demanding tangible therapeutic benefit is adaptable to emerging technologies like biologics, biosimilars, and AI-generated drugs, ensuring Section 3(d) will remain a central and evolving feature of Indian patent law.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act compliant with the TRIPS Agreement?

Yes, Section 3(d) is widely considered to be compliant with the TRIPS Agreement. The Madras High Court upheld its constitutional validity, and India has consistently maintained its compliance at international forums.8 The TRIPS Agreement provides member states with “flexibilities” to design their patent laws to suit their socio-economic needs and protect public health. Article 27 requires patents to be available for inventions that are new, involve an inventive step, and are capable of industrial application, but it does not define “invention.” India has used this flexibility to statutorily define certain subject matters—like new forms of known substances without enhanced efficacy—as not being “inventions” under its law.

2. How does Section 3(d) affect patenting strategies for biologics and biosimilars in India?

While the jurisprudence is still developing, the principles of Section 3(d) are applicable. A biosimilar could be considered a “new form” of a “known substance” (the reference biologic). To secure a patent on a “biobetter” (a biosimilar with improvements), an applicant would likely need to demonstrate “enhanced therapeutic efficacy.” This could involve showing a superior clinical response, a significantly improved safety profile (e.g., reduced immunogenicity), or a more convenient route of administration. The definition of “efficacy” would be context-specific, focusing on the clinical function of the biologic, making the evidentiary burden scientifically complex and high.

3. Can a significant improvement in safety or a reduction in side effects satisfy the “enhanced therapeutic efficacy” requirement?

Yes, this is a strong possibility. The Supreme Court in the Novartis case left the door open for a broader interpretation of “therapeutic efficacy” beyond just curative effect. A new form of a drug that has the same primary therapeutic effect but is demonstrably safer or has significantly fewer side effects provides a direct therapeutic benefit to the patient. An applicant would need to provide robust comparative data from clinical or preclinical studies to substantiate such a claim. This remains one of the most promising, though challenging, avenues for innovators to overcome a Section 3(d) objection.

4. What is the most common mistake innovator companies make when facing a Section 3(d) objection in India?

The most common mistake is relying on data for physicochemical properties or intermediate endpoints (like bioavailability) without explicitly and convincingly linking that data to an improved therapeutic outcome. After the Novartis ruling, it is a fatal error to assume that an examiner or court will infer therapeutic enhancement from improved stability, solubility, or bioavailability data. The applicant must connect the dots and provide evidence—or at least a strong, scientifically-backed argument—that this property translates into a tangible benefit for the patient, such as a better clinical response, lower toxicity, or improved patient compliance.

5. Has Section 3(d) actually harmed foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Indian pharmaceutical sector?

The impact is debated and difficult to isolate from other economic factors. Critics argue that the challenging IP environment, with Section 3(d) as a centerpiece, deters R&D-based foreign investment. However, the data on FDI is mixed. While there are concerns, India’s massive market size and manufacturing capabilities continue to attract foreign investment, often through mergers and acquisitions rather than greenfield R&D centers.6 The provision may deter investment aimed at securing monopolies for incremental innovations, but it does not appear to have stopped investment in manufacturing, marketing, or collaborations focused on the Indian market’s unique opportunities.

References

- Indian pharmaceutical patent prosecution: The changing role of Section 3(d), accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/indian-pharmaceutical-patent-prosecution-the-changing-role-of-section-3d/

- Section-3 (D) of The Patents Act, 1970 | PDF – Scribd, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/485092771/c2-docx

- Section Details – India Code, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_11_61_00002_197039_1517807321764§ionId=15871§ionno=3&orderno=3

- TRIPS Agreement: Balancing Trade & IP Rights, accessed August 3, 2025, https://depenning.com/blog/trips-agreement-balancing-trade-and-intellectual-property-rights/

- From Pharmacy of The World to Patent Prison: India’s Shift Under Trips – IIPRD, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.iiprd.com/from-pharmacy-of-the-world-to-patent-prison-indias-shift-under-trips/

- Public Policy and Economic Development Case Study of Indian …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ris.org.in/sites/default/files/Publication/Public%20Policy%20and%20Economic%20Development%20Case%20Study%20of%20Indian%20Pharmaceutical%20Industry-min.pdf

- Pages from history: The mysterious legislative history of Section 3(d …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://spicyip.com/2011/11/pages-from-history-mysterious.html

- How to analyze section 3(d) of Indian Patent Act? – SSRANA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ssrana.in/wp-content/themes/ssrana/pdf-file/How-to-analyze-section-3(d)-of-Indian-Patent-Act.pdf

- Indian Patent Law Section 3d: Preventing Evergreening & True Innovation, accessed August 3, 2025, https://thelegalschool.in/blog/indian-patent-law-section-3d

- Relooking at the reach of Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.asialaw.com/NewsAndAnalysis/relooking-at-the-reach-of-section-3d-of-the-indian-patents-act-1970-after-nov/Index/1854

- Novartis AG v. Union of India & Others – UNCTAD, accessed August 3, 2025, https://unctad.org/ippcaselaw/sites/default/files/ippcaselaw/2020-12/Novartis%20AG%20v.%20Union%20of%20India%20%26%20Others%20Indian%20Supreme%20Court%202013_0.pdf

- Novartis AG v. Union of India & Others – IP Matters, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.theipmatters.com/post/novartis-ag-v-union-of-india-others

- Novartis Indian Supreme Court judgment: what is efficacy for …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.nishithdesai.com/Content/document/pdf/ResearchArticles/MIPR_Novartis.pdf

- The Judgment In Novartis v. India: What The Supreme Court Of India …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ip-watch.org/2013/04/04/the-judgment-in-novartis-v-india-what-the-supreme-court-of-india-said/

- Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act – Part I | The National La, accessed August 3, 2025, https://natlawreview.com/article/section-3d-indian-patents-act-part-i

- Biochemical substances and the realm of S. 3(d) (Novozymes vs …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://legalblogs.wolterskluwer.com/patent-blog/biochemical-substances-and-the-realm-of-s-3d-novozymes-vs-the-assistant-controller-of-patents-and-designs-scope-of-applicability-of-section-3d-redefined-by-madras-high-court/

- ‘Non’-Pharmaceutical Substance and Efficacy under Sec 3(d) – SpicyIP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://spicyip.com/2024/02/non-pharmaceutical-substance-and-efficacy-under-sec-3d.html

- Therapeutic Efficacy: A Requirement Under Section 3(d), Not Section 3(e) of the Indian Patents Act – The IP Press, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.theippress.com/2025/07/14/therapeutic-efficacy-a-requirement-under-section-3d-not-section-3e-of-the-indian-patents-act/

- Understanding the Difference between Section 3(d) and 3(e) through Oramed, accessed August 3, 2025, https://kankrishme.com/understanding-the-difference-between-section-3d-and-3e-through-oramed/

- Resolving the conflict between section 3(d) and section 3(e) | LexOrbis, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.lexorbis.com/resolving-the-conflict-between-section-3d-and-section-3e/

- Section 3(d) Strikes Again: Nippon Steel v. Controller General of Patents – Kan and Krishme, accessed August 3, 2025, https://kankrishme.com/section-3d-strikes-again-nippon-steel-v-controller-general-of-patents/

- Indian Patent Office must Identify the Known Substance to Objectify the Claimed Compound under Section 3(d) – DS Biopharma Limited v. The Controller of Patents and Designs. – Kan and Krishme, accessed August 3, 2025, https://kankrishme.com/indian-patent-office-must-identify-the-known-substance-to-objectify-the-claimed-compound-under-section-3d-ds-biopharma-limited-v-the-controller-of-patents-and-designs/

- Delhi HC Clarifies the Threshold of Section 3(d): Enhanced Efficacy & Procedural Fairness in Patent – K&S Partners, accessed August 3, 2025, https://kandspartners.com/delhi-high-court-clarifies-the-threshold-of-section-3d-enhanced-efficacy-and-procedural-fairness-in-patent-cases/

- Indian pharmaceutical patent prosecution: The changing role of …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0194714

- Indian pharmaceutical patent prosecution: The changing role of Section 3(d) – PubMed, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29608604/

- An-Analysis-on-the-Hypothetical-Interpretations-of-Section-3D-of-the-Indian-Patent-Act-and-its-Impact.pdf, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ijlsi.com/wp-content/uploads/An-Analysis-on-the-Hypothetical-Interpretations-of-Section-3D-of-the-Indian-Patent-Act-and-its-Impact.pdf

- A Closer Look at the Patent Stats from WIPO’s 2024 IP Indicator …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://spicyip.com/2024/11/a-closer-look-at-the-patent-stats-from-wipos-2024-ip-indicator.html

- 2141-Examination Guidelines for Determining Obviousness Under …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2141.html

- Determination of Obviousness/Inventive Step by the European …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.invntree.com/blogs/determination-obviousnessinventive-step-european-patent-office

- Comparative Study on Hypothetical/Real Cases: Inventive Step/Non …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://link.epo.org/trilateral/Comparative_Study_on_Cases_Inventive_Step.pdf

- How to overcome Section 3(d) Objections ? – Stratjuris Law Partners, accessed August 3, 2025, https://stratjuris.com/how-to-overcome-section-3d-objections/

- Patent protection strategies – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3146086/

- (PDF) Provisions of Generic Drugs under Section 3(d) of Indian IP …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363210741_Provisions_of_Generic_Drugs_under_Section_3d_of_Indian_IP_Act_What_does_Data_from_the_Backward_States_Reveal

- Section 3(d): Implications and key concerns for pharmaceutical sector – ResearchGate, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318887875_Section_3d_Implications_and_key_concerns_for_pharmaceutical_sector

- Section 3(d) and Pharmaceutical Patents in India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/55114/1/JIPR%2025%283-4%29%2065-73.pdf

- Section 3(d) – Landmark Cases | candcip, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.candcip.com/section-3-d-landmark-cases

- Review Article, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.asianpharmtech.com/articles/concept-of-substantial-similarity-in-pharmaceuticalpatent-infringement-cases-and-the-implications-ofsection-3d-of-indian.pdf

- DrugPatentWatch – 2025 Company Profile & Competitors – Tracxn, accessed August 3, 2025, https://tracxn.com/d/companies/drugpatentwatch/__J3fvnNbRBdONp_-p-gLex5dxrrF6shPqUenXhHlGHHM

- DrugPatentWatch Reviews 2025: Details, Pricing, & Features | G2, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.g2.com/products/drugpatentwatch/reviews

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 3, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- India’s Growing Importance in Generic Drug API Manufacturing …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/indias-growing-importance-in-generic-drug-api-manufacturing/

- India drug patents, expiration dates and freedom-to-operate – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/p/international/index.php?country=India

- Understanding Pharmaceutical Competitor Analysis – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-importance-of-pharmaceutical-competitor-analysis/

- The Pharmaceutical Patent Playbook: Forging Competitive Dominance from Discovery to Market and Beyond – DrugPatentWatch, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/developing-a-comprehensive-drug-patent-strategy/

- Online Course: Business intelligence for bio/pharma drugs – DrugPatentWatch from Udemy, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.classcentral.com/course/udemy-generic-drug-portfolio-branded-drug-lifecycle-management-401093

- An Analysis on leveraging the patent cliff with drug sales worth USD …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pharma-dept.gov.in/sites/default/files/FINAL-An%20analysis%20on%20leveraging%20the%20patent%20cliff.pdf

- “India must not relent on Section 3(d)”, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/india-must-not-relent-on-section-3d/

- USTR 2025 Special 301 Report corrects course | PhRMA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/ustr-2025-special-301-report-corrects-course

- USTR: 2019 SPECIAL 301 SUBMISSION – Regulations.gov, accessed August 3, 2025, https://downloads.regulations.gov/USTR-2018-0037-0017/attachment_1.pdf

- US pharma body slams Indian patent regime – Times of India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/us-pharma-body-slams-indian-patent-regime/articleshow/50908408.cms

- USTR Special 301 report criticized as unfair, ignoring India’s IP progress – MLex, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.mlex.com/mlex/trade/articles/2335630/ustr-special-301-report-criticized-as-unfair-ignoring-india-s-ip-progress

- Current challenges in the patent system – Hindustan Times, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.hindustantimes.com/ht-insight/governance/current-challenges-in-the-patent-system-101754125565353.html

- High Drug Prices Hurt Everyone – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4904249/

- Drug pricing policies in one of the largest drug manufacturing …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4326966/

- Indian Supreme Court rejects Novartis’s appeal on drug patent | The …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f2099

- How Indian Pharma Can Become Global Leaders – ProMarket, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.promarket.org/2023/12/21/how-indian-pharma-can-become-global-leaders/

- Indian Pharma Hits R&D Salvo – BioSpectrum India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.biospectrumindia.com/features/18/25489/indian-pharma-hits-rd-salvo.html

- ROUNDTABLE ON SECTION 3(d) OF THE PATENTS ACT … – FICCI, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ficci.in/public/storage/SEDocument/20142/Report_on_section_3d.pdf

- MEMORANDUM EXPLAINING THE PROVISIONS IN THE FINANCE BILL, 2025 – Union Budget, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/memo.pdf

- IAPP Global Legislative Predictions 2025, accessed August 3, 2025, https://iapp.org/resources/article/global-legislative-predictions/

- Text – H.R.1574 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): RESTORE Patent Rights Act of 2025, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1574/text

- Report of the Joint Committee on Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2024 – Digital Sansad, accessed August 3, 2025, https://sansad.in/getFile/lsscommittee/Joint%20Committee%20on%20the%20Waqf%20(Amendment)%20Bill,%202024/18_Joint_Committee_on_the_Waqf_(Amendment)_Bill_2024_1.pdf?source=loksabhadocs

- (PDF) The “Efficacy” of Indian Patent Law: Ironing out the Creases in Section 3(d), accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228155308_The_Efficacy_of_Indian_Patent_Law_Ironing_out_the_Creases_in_Section_3d

- The “Efficacy” of Indian Patent Law: Ironing out the Creases in Section 3(d) Shamnad Basheer & T. – SCRIPTed, accessed August 3, 2025, https://script-ed.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/5-2-BasheerReddy.pdf

- An Attempt at Quantification of ‘Efficacy’ Factors under Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act – Manupatra, accessed August 3, 2025, http://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/02C35991-70A8-4244-B7E0-2A33C0A152A9.pdf

- Federis – Examination Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Patent Application involving Known Substances, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.federislaw.com.ph/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Examination-Guidelines-for-Pharmaceutical-Patent-Application-involving-Known-Substances.pdf

- Patent Examination Guidelines – IPOPHL, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ipophil.gov.ph/services/patent-examination-guidelines/

- INDIA- Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act: Comprehending identification of “A Known Substance”, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.candcip.com/single-post/india-section-3-d-of-the-indian-patents-act-comprehending-identification-of-a-known-substance

- Pharma downplays 25% tariff impact: US healthcare could feel the blow instead of India- what sector experts say, accessed August 3, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/pharma-downplays-25-tariff-impact-us-healthcare-could-feel-the-blow-instead-of-india-what-sector-experts-say/articleshow/123015633.cms

- RETHINKING OBVIOUSNESS – Wisconsin Law Review, accessed August 3, 2025, https://wlr.law.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1263/2015/11/5-Kennedy-Final.pdf

- 2014, PhRMA discussion of India – Knowledge Ecology International, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.keionline.org/25948

- India: The implications for patent owners of section 3(d) | Managing …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.managingip.com/Article/3261987/India-The-implications-for-patent-owners-of-section-3d.html

- MANUAL OF PATENT OFFICE PRACTICE AND … – IP India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/IPOGuidelinesManuals/1_28_1_manual-of-patent-office-practice_and-procedure.pdf

- Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) – USPTO, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/index.html

- MANUAL OF PATENT OFFICE PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/world/asia/in/ip/pdf/201103_tokkyo_02.pdf

- Manual Of Designs Practice &Procedure – IP India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/IPOGuidelinesManuals/1_30_1_manual-designs-practice-and-procedure.pdf

- Manual of Patent Practice & Procedure – IP India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/IPOGuidelinesManuals/1_59_1_15-wo-ga-34-china.pdf

- MANUAL OF PATENT OFFICE PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – IP India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/Images/pdf/Manual_for_Patent_Office_Practice_and_Procedure_.pdf

- Agilent Technologies Launches Biopharma Experience Center in Hyderabad to Enhance Drug Development Efficiency – GeneOnline News, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/agilent-technologies-launches-biopharma-experience-center-in-hyderabad-to-enhance-drug-development-efficiency/

- Indian Pharmaceutical Industry: Navigating Challenges and …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/indian-pharma-some-challenges-and-acceptances/

- Patent watch: Drug patenting in India: Looking back and looking forward | Request PDF, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280117693_Patent_watch_Drug_patenting_in_India_Looking_back_and_looking_forward

- Complexity of Pharmaceutical Patent Regulation in India – AIPPI, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.aippi.org/news/complexity-of-pharmaceutical-patent-regulation-in-india-an-all-inclusive-analysis-of-the-dolutegravir-patent-case/

- What inventions cannot be patented in India? | epo.org, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.epo.org/en/service-support/faq/searching-patents/asian-patent-information/india/general-information-about-3

- The R&D Scenario in Indian Pharmaceutical Industry – Research and Information System for Developing Countries, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ris.org.in/sites/default/files/Publication/dp176_pap.pdf

- PhRMA Special 301 Submission 2025, accessed August 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/resources/phrma-special-301-submission-2025

- 2023 Special 301 Report | USTR, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2023-04/2023%20Special%20301%20Report.pdf

- The Patents Act, 1970 – IP India, accessed August 3, 2025, https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/portal/ipoact/1_31_1_patent-act-1970-11march2015.pdf

- The Global Significance of India’s Pharmaceutical Patent Laws, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.aipla.org/list/innovate-articles/the-global-significance-of-india-s-pharmaceutical-patent-laws

- What is section 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act – The Economic Times, accessed August 3, 2025, https://m.economictimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/pharmaceuticals/what-is-section-3d-of-the-indian-patent-act/articleshow/19321453.cms

- Robert Bosch Limited v. Deputy Controller of Patents and Designs – interpretation of Sec 3(m), accessed August 3, 2025, https://depenning.com/blog/robert-bosch-limited-v-deputy-controller-of-patents-and-designs-interpretation-of-sec-3m/

- IP News Updates: March – June 2025 – IP Matters, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.theipmatters.com/post/ip-news-updates-march-june-2025