Introduction: The Grand Bargain That Forged an Industry and a Battlefield

In the annals of American industrial policy, few pieces of legislation have been as quietly transformative, as profoundly impactful, or as ingeniously contentious as the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984. Known colloquially by the names of its sponsors, Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, this landmark act was far more than a simple regulatory update. It was a grand bargain, a carefully constructed compromise designed to solve two seemingly irreconcilable problems: the soaring cost of prescription drugs and the dwindling incentives for pharmaceutical innovation.1

On one side of this legislative scale, the Act sought to unleash the forces of market competition by creating a streamlined, efficient pathway for low-cost generic drugs to enter the market once a brand-name drug’s patent expired. On the other, it aimed to reward the immense risk and investment of innovator companies by restoring a portion of the patent life lost during the lengthy Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process.2 The goal was elegant in its symmetry: foster a vibrant generic market to drive down prices for consumers while preserving the intellectual property rights that fuel the discovery of new, life-saving medicines.

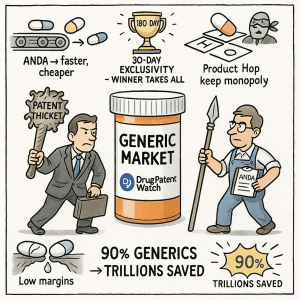

By any quantitative measure, the Hatch-Waxman Act has been a spectacular success. It single-handedly catalyzed the creation of the modern U.S. generic drug industry, a sector that was languishing in regulatory purgatory before 1984. In the four decades since its passage, the share of prescriptions filled with generic drugs has skyrocketed from a mere 19% to over 90% today.1 This seismic shift has generated staggering savings for the American healthcare system—trillions of dollars over its lifetime, with savings in 2023 alone exceeding $445 billion.2 It is no exaggeration to say that the Act fundamentally reshaped the economics of American healthcare.

But to view Hatch-Waxman solely through the lens of economic statistics is to miss its true, and far more fascinating, legacy. The Act did not merely create a market; it created a battlefield. By codifying the opposing interests of innovator and generic manufacturers into a set of interlocking rules, incentives, and legal triggers, it established a permanent state of strategic warfare. Every provision, from the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway to the arcane details of patent certification, became a weapon in a high-stakes corporate chess match. The prize? Control over the American pill bottle and the billions in revenue it represents.

This report will dissect the profound transformation of the U.S. generic drug industry in the wake of this grand bargain. We will begin by journeying back to the pre-1984 landscape, a world of stifling regulation where generic competition was more theoretical than real. We will then meticulously deconstruct the architecture of the Hatch-Waxman Act itself, revealing how each provision was designed to function as a strategic lever. From there, we will trace the explosive economic and corporate evolution that followed, charting the rise of generic titans and the trillions in savings they delivered.

Most critically, we will delve into the sophisticated strategies and counter-strategies—the patent warfare—that the Act unleashed. We will explore the innovator’s playbook of “evergreening,” “product hopping,” and “patent thickets,” and the challenger’s primary weapon: the Paragraph IV patent challenge. We will examine how landmark court cases and subsequent legislative tune-ups have continuously redrawn the lines of this battlefield. Finally, we will confront the unintended consequences and modern challenges—from chronic drug shortages to allegations of price-fixing—that have emerged from the very success of the Hatch-Waxman model.

For the business professional, the strategist, and the investor, the story of Hatch-Waxman is more than a history lesson. It is a masterclass in how a single piece of legislation can define an entire industry’s competitive dynamics for generations. Understanding this story—its triumphs, its loopholes, and its ongoing evolution—is essential for anyone seeking to navigate the complex and lucrative world of the modern pharmaceutical industry. Welcome to the world that Hatch and Waxman built.

A Market in Stasis: The U.S. Pharmaceutical Landscape Before 1984

To truly appreciate the revolutionary impact of the Hatch-Waxman Act, one must first understand the stagnant and deeply inefficient pharmaceutical market that preceded it. The America of the early 1980s was a world where brand-name drugs enjoyed a prolonged, often indefinite, monopoly, even long after their patents had expired. The generic drug industry, as we know it today, was a nascent and largely impotent force, shackled by a regulatory framework that made competition nearly impossible.

The roots of this market paralysis lay in a well-intentioned but ultimately flawed piece of legislation: the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.11 Passed in the wake of the thalidomide tragedy, these amendments were a landmark achievement in consumer protection. For the first time, they required drug manufacturers to prove not only that their products were safe, but also that they were

effective for their intended use before receiving FDA approval. While this was a monumental step forward for public health, it had a devastating and unintended consequence for generic competition.

Prior to 1962, the path to market for a generic drug was relatively straightforward. After 1962, the FDA interpreted the new effectiveness requirement to apply to all new drugs, including generic copies of previously approved medicines. This meant that a generic manufacturer couldn’t simply demonstrate that its product was a chemical copy of the original; it had to conduct its own, separate, and complete set of expensive and time-consuming clinical trials to independently prove safety and efficacy.1

This requirement was a death knell for the generic business model. The entire value proposition of a generic drug is its low cost, a result of avoiding the massive research and development expenditures of the innovator. By forcing generic companies to duplicate the most expensive part of the drug development process, the regulatory system created an insurmountable financial barrier. It was economically nonsensical to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on clinical trials to bring a product to market that, by definition, would have to sell at a steep discount to the original.

The result was a market where patent expiration meant very little. Even when a brand-name drug’s legal monopoly ended, it continued to enjoy a de facto monopoly. The regulatory lag time for a generic competitor to even attempt to enter the market was a staggering three to five years. Consequently, only about 35% of top-selling drugs faced any generic competition after their patents lapsed.2 The market penetration of generics was abysmal, accounting for a mere 19% of all prescriptions filled in the United States.1

This system created what can only be described as a “shadow exclusivity”—a period of monopoly protection that extended far beyond the statutory patent term, granted not by patent law but by the sheer inertia and impracticality of the regulatory process. For brand-name companies, it was a golden era of sustained profits. For consumers and the healthcare system, it was a period of perpetually high drug prices with no competitive relief in sight.

The FDA did make some attempts to rectify the situation. In 1970, the agency created an initial Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, allowing approvals based on bioequivalence for drugs approved prior to 1962. For drugs approved after 1962, a “paper NDA” policy was introduced, which allowed generic manufacturers to cite published scientific literature to support safety and efficacy claims.11 However, these pathways were slow, cumbersome, and fraught with uncertainty. Their ineffectiveness is starkly illustrated by the numbers: between 1979 and 1983, a paltry 19 generic drugs were approved under the paper NDA rule.

Yet, this challenging environment inadvertently forged the core competencies that would define the future generic industry. The few companies that dared to operate in this space, like Mylan and Teva, had to become masters of two domains: hyper-efficient, low-cost manufacturing and byzantine regulatory navigation. They learned to survive on razor-thin margins and to wring every ounce of efficiency out of their operations. They were battle-hardened and perfectly positioned for the moment the landscape would shift. When the Hatch-Waxman Act finally arrived and blasted away the primary barrier to entry—the duplicative clinical trials—these companies were not starting from scratch. They were coiled springs, ready to unleash their hard-won expertise onto a newly opened market. The Act provided the spark, but the kindling had been slowly accumulating for over two decades.

The Grand Bargain: Deconstructing the Hatch-Waxman Act

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 was a masterstroke of legislative compromise, a complex piece of machinery with interlocking gears designed to serve two masters: the innovator pharmaceutical companies and the nascent generic industry. At its core, the Act was a grand bargain that fundamentally rewired the relationship between patent law and drug regulation. To understand its transformative power, we must dissect this machine piece by piece, examining not just what each provision does, but its strategic purpose within the broader compromise.

The ANDA Pathway: The Engine of the Generic Revolution

The absolute centerpiece of the Hatch-Waxman Act, and the provision that breathed life into the generic industry, was the creation of the modern Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, codified under Section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.1 This was the legislative key that unlocked the market.

The ANDA process elegantly solved the pre-1984 conundrum by declaring that the extensive safety and efficacy trials conducted by the innovator company would suffice for the entire class of drugs. A generic applicant would no longer need to repeat these costly and ethically questionable human trials.15 Instead, the burden of proof was dramatically simplified. The generic company needed only to demonstrate two key things:

- Pharmaceutical Equivalence: The generic drug has the same active ingredient(s), dosage form, strength, and route of administration as the innovator product, known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD).

- Bioequivalence: The generic drug is absorbed into the body and becomes available at the site of drug action at the same rate and to the same extent as the RLD.14

By allowing generic manufacturers to rely on the innovator’s safety and efficacy data, the ANDA pathway slashed the time and cost of generic drug development from years and hundreds of millions of dollars to a fraction of that.1 It was the engine that would power the generic revolution, transforming the industry from a cottage enterprise into a global powerhouse.

The Innovator’s Reward: Patent Term Restoration and Market Exclusivity

Of course, this powerful new tool for generics was not given for free. The other side of the grand bargain was a suite of new protections designed to compensate innovator companies for the increased competitive pressure they would now face. These rewards came in two primary forms: patent term restoration and new types of regulatory exclusivity.

Patent Term Restoration (PTE): Innovator companies had long argued that the lengthy FDA review process was eroding their effective patent life. A significant portion of their 17-year patent term (at the time) was spent waiting for regulatory approval, during which they could not market their product. The Hatch-Waxman Act addressed this by allowing brand-name companies to apply for an extension of their patent term to compensate for a portion of the time lost during clinical testing and FDA review.3 This provision ensured that the new, faster generic competition would not unfairly penalize innovators by shortening their effective monopoly period.

Regulatory Exclusivity: Perhaps even more significantly, the Act created entirely new forms of market protection that are administered by the FDA and operate completely independently of a drug’s patent status.3 These “regulatory exclusivities” created a guaranteed period of market protection, even if a drug had no patent protection at all. The key exclusivities included:

- Five-Year New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A drug containing a new active ingredient that had never before been approved by the FDA was granted five years of data exclusivity. During this period, the FDA could not even accept an ANDA for filing, effectively barring any generic challenge.3

- Three-Year “New Clinical Investigation” Exclusivity: This was granted for drugs that were already approved but for which the manufacturer conducted new and essential clinical trials to get a new indication, formulation, or dosage strength approved. This exclusivity prevents the FDA from approving an ANDA for that specific change for three years.3

- Six-Month Pediatric Exclusivity: To incentivize the study of drugs in children, this provision adds an extra six months of protection to any existing patents and exclusivities on a drug if the manufacturer conducts requested pediatric studies.

These provisions were the critical “sweeteners” that brought the innovator industry to the negotiating table, ensuring that while competition would be fiercer, the rewards for true innovation would be preserved and even enhanced.

The Battlefield Defined: Patent Certifications and the Orange Book

To make this new system work, the Act needed a transparent and standardized way to manage the complex interplay between drug approvals and patent rights. This led to the creation of two foundational pillars of the Hatch-Waxman framework: the “Orange Book” and the system of patent certifications.

The FDA’s publication, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, colloquially known as the Orange Book, became the central repository of information.14 The Act required brand-name companies to list all patents that they believed could reasonably be asserted against a generic manufacturer for infringing their approved drug.3

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must review the Orange Book patents for the RLD and make a certification for each one. There are four possible certifications, but the one that would define the next four decades of pharmaceutical litigation is the Paragraph IV certification. By filing a Paragraph IV certification, the generic company boldly asserts that the brand’s listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product.21

This was a radical concept. The Act defined the very act of filing a Paragraph IV certification as an “artificial act of infringement”. This brilliant legal fiction allowed the brand-name company to sue the generic for patent infringement before the generic drug ever hit the market, setting the stage for pre-launch patent litigation that would become the industry’s primary battleground.

The Strategic Levers: 180-Day Exclusivity and the 30-Month Stay

If the Paragraph IV certification created the battlefield, two final provisions provided the strategic levers that each side could pull to gain an advantage. These two mechanisms, more than any others, would come to dictate the rhythm and strategy of Hatch-Waxman warfare.

180-Day Exclusivity: To incentivize generic companies to undertake the risky and expensive process of challenging a brand’s patent, the Act offered a powerful prize: a 180-day period of market exclusivity for the first generic applicant to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification.2 During this six-month period, the FDA is barred from approving any subsequent generic applications for the same drug. This effectively creates a duopoly between the brand and the first generic challenger, a period of immense profitability that often accounts for the majority of a generic drug’s total lifetime earnings.22 This “brass ring” transformed the generic business model from one of passive manufacturing into an aggressive, litigation-focused enterprise.

30-Month Stay: To protect the innovator’s rights during this pre-launch litigation, the Act created an automatic injunction. If the brand-name company files a patent infringement suit against the Paragraph IV challenger within 45 days of receiving notice, the FDA is automatically prohibited from granting final approval to the generic’s ANDA for up to 30 months.5 This “30-month stay” was intended to provide a sufficient window for the courts to resolve the patent dispute before a potentially infringing product could cause irreparable harm to the patent holder. However, as we will see, this procedural safeguard would quickly be repurposed by innovator companies into a powerful offensive weapon for predictably delaying competition, regardless of a patent’s underlying strength.

The “Safe Harbor”: Protecting Pre-Launch Development

Finally, the Act addressed a critical legal gray area that had previously chilled generic development. Before 1984, the very act of manufacturing and testing a generic version of a patented drug for the purposes of preparing an FDA submission could be considered patent infringement. This created a catch-22, effectively extending the brand’s monopoly because generics could not even begin their development work until after the patent expired.

The Hatch-Waxman Act created a statutory “safe harbor” provision, exempting generic firms from infringement liability for activities “solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the manufacture, use, or sale of drugs”.1 This crucial provision allowed generic companies to conduct their bioequivalence studies and prepare their ANDAs while the brand’s patents were still in force, ensuring that they could be ready to launch on the very day the patent expired, or even earlier if their Paragraph IV challenge was successful.

Together, these interlocking provisions created a complex, dynamic, and adversarial system. It was a masterpiece of legislative engineering that successfully balanced competing interests on paper. But in the real world, it unleashed a torrent of economic activity and legal conflict that would transform the industry beyond its architects’ wildest imaginations.

The Economic Revolution: Four Decades of Transformation and Trillions in Savings

The passage of the Hatch-Waxman Act was not merely a legislative event; it was an economic cataclysm. The “grand bargain” immediately uncorked decades of pent-up competitive pressure, unleashing a wave of generic entry that fundamentally and permanently altered the financial landscape of the U.S. healthcare system. The numbers tell a staggering story of market transformation, price deflation, and unprecedented cost savings.

The impact was immediate and overwhelming. In the very first year following the Act’s signing in 1984, the FDA was inundated with approximately 1,050 ANDA applications—a signal of the industry’s readiness to seize the new opportunity.2 This flood of new competition was projected to save the healthcare system $1 billion in its first year alone, a figure that would soon seem laughably small. At the pharmacy counter, the change was palpable. By the second year after the Act, the generic substitution rate—the percentage of brand-name prescriptions that were filled with a generic equivalent—had nearly doubled, jumping from 12% to 22%.

This was just the opening salvo in a four-decade-long market takeover. The growth trajectory of generic market share is one of the most dramatic trend lines in modern healthcare economics. From its meager 18.6% share in 1984, the generic portion of dispensed prescriptions climbed steadily:

- By 2004, it had reached 53%.

- By 2007, it stood at 63%.

- By 2014, it had surged to an overwhelming 86%.

- Today, more than 9 out of every 10 prescriptions filled in the United States are for a generic drug.1

This dramatic shift in volume was accompanied by an equally dramatic collapse in prices for off-patent drugs. The core economic principle of the Act—that competition drives down prices—was validated with textbook precision. Generic drugs are typically priced 30% to 80% less than their brand-name counterparts.2 More importantly, the price continues to fall as more competitors enter the market for a specific drug. Studies have consistently shown a direct correlation between the number of generic manufacturers and the depth of the price reduction. The entry of just three competitors can slash prices by 20%, while markets with ten or more competitors often see prices plummet by 70% to 80% relative to the pre-generic brand price. In highly competitive markets with six or more generic options, price reductions can exceed an astonishing 95%.

The cumulative effect of this massive shift to lower-priced alternatives has been a windfall for the American healthcare system. The savings have grown exponentially over time, creating a powerful deflationary force in an otherwise inflationary sector.

The use of generic and biosimilar drugs has saved patients and the U.S. healthcare system over $3 trillion dollars in the last ten years alone. In 2023, these medicines created $445 billion in savings. 9

This cascade of savings has been staggering. What began as a projected $1 billion in annual savings in 1985 grew to an estimated $8-10 billion by 1994. By 2014, the annual savings had surpassed $230 billion, and by 2021, they reached a record $373 billion.2 The table below provides a snapshot of this remarkable economic transformation over four decades.

| Year | Generic Rx Share (%) | Annual Healthcare Savings (Billions, Current USD) | Annual ANDA Approvals (Full & Tentative) | Key Legislative/Market Event |

| 1984 | 19% 1 | ~$0 | N/A | Hatch-Waxman Act passed. |

| 1994 | ~36% | ~$8-10 | ~300-400 (est.) | Uruguay Round Agreements Act extends patent terms. |

| 2004 | 53% | ~$50-60 (est.) | 384 | Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003 closes loopholes. |

| 2014 | 86% | >$230 | 530 (est.) | Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) of 2012 begins to clear ANDA backlog. |

| 2023 | >90% 8 | $445 | 956 | GDUFA reauthorizations continue to streamline approvals; Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) introduces new pricing dynamics. |

Of course, this revolution was not without consequences for innovator companies. The faster and more certain entry of generic competition did erode the tail-end profits of brand-name drugs. One early study estimated that the Act lowered the average returns from marketing a new drug by roughly 12%, or about $27 million in 1990 dollars, as the benefits of patent term extensions were roughly offset by the costs of more intense generic competition. This created a powerful incentive for brand-name companies to develop the sophisticated defensive strategies that will be explored later in this report.

However, the Act’s success in driving down prices also created a new, unforeseen economic vulnerability. The very hyper-competition that generated trillions in savings squeezed the profit margins on many older, high-volume generic drugs to razor-thin levels.8 This is particularly true for simple oral solid medications. When profits are negligible, there is little economic incentive for manufacturers to maintain redundant production lines or invest in modernizing older facilities. The market becomes brittle, with little capacity to absorb shocks like a manufacturing plant failing an inspection, a disruption in the global supply of a raw ingredient, or a sudden spike in demand.

This economic fragility, a direct and ironic consequence of the Act’s success, sowed the seeds for the chronic drug shortages that began to plague the U.S. healthcare system in the 2010s and continue to this day.32 The shortages are not a sign that the Hatch-Waxman market model has failed; rather, they are a systemic consequence of the model working exactly as designed—driving prices down to the marginal cost of production, leaving no economic buffer for resilience. The economic revolution, it turned out, had a hidden cost.

The New Titans: The Corporate Evolution of the Generic Industry

The economic upheaval unleashed by the Hatch-Waxman Act did not just reshape market statistics; it fundamentally reconfigured the corporate landscape of the pharmaceutical industry. Before 1984, the term “generic manufacturer” described a small, scattered collection of companies operating on the industry’s fringes. After 1984, the Act provided the fertile ground from which a new class of corporate titans would grow—companies that would eventually rival their brand-name counterparts in scale, sophistication, and global reach.

The effect on the early generic players was electric. Mylan Pharmaceuticals, a company founded in a former skating rink in West Virginia, saw its fortunes explode. In the 18 months following the Act’s passage, Mylan’s earnings skyrocketed by 166%, and its stock value soared by an incredible 800%. This sudden infusion of capital and market opportunity transformed the company from a small-time operator into a serious industry contender.

Similarly, the Israeli firm Teva Pharmaceutical Industries saw the Act as a gateway to the lucrative U.S. market. Seizing the opportunity, Teva established a joint venture in the U.S. in 1985 and acquired Lemmon Pharmacal Company, giving it an immediate foothold.36 These early moves, enabled directly by the new regulatory pathway, set the stage for Teva’s eventual rise to become the world’s largest generic drug manufacturer.

The growth of these new titans was fueled by a dual strategy of organic expansion and, more importantly, aggressive mergers and acquisitions (M&A). As the generic market matured and became more competitive, scale became a critical advantage. The decades following Hatch-Waxman were marked by relentless consolidation as larger players swallowed smaller ones to gain market share, expand their product portfolios, and achieve greater manufacturing efficiencies.

Teva’s acquisition history reads like a roadmap of industry consolidation. Key acquisitions included Barr Pharmaceuticals in 2008, Cephalon in 2011, and, in a blockbuster deal, Allergan’s generic business (Actavis Generics) in 2016. Each deal brought Teva a broader portfolio of generic and specialty drugs, expanded its R&D capabilities, and strengthened its global operational network.

Mylan followed a similar trajectory, acquiring Matrix Laboratories in India to become a major player in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), buying Merck KGaA’s generics division (which brought with it the blockbuster EpiPen), and purchasing Agila Specialties to bolster its presence in injectable drugs.34 This decades-long expansion culminated in the 2019 merger with Pfizer’s off-patent division, Upjohn, to create a new global giant, Viatris.

This wave of consolidation was not merely a typical business trend; it was a direct and inevitable outcome of the strategic landscape Hatch-Waxman created. As discussed, the Act’s most powerful incentive, the 180-day exclusivity for Paragraph IV challengers, transformed the generic business model into one centered on high-stakes patent litigation. This new reality fundamentally favored large, well-capitalized companies.

Patent litigation is an expensive, high-risk endeavor. A single case can cost millions of dollars in legal fees, with no guarantee of success. A small generic company might bet its future on challenging the patent of a single drug. If that challenge fails, the company could face financial ruin. A large, consolidated player like Teva or Viatris, however, can afford to operate on a portfolio basis. They can initiate dozens of Paragraph IV challenges simultaneously across a wide range of products. They can absorb the losses from ten failed challenges, knowing that winning the 180-day exclusivity on a single blockbuster drug will generate enough profit to cover all the failures and then some.

This creates a powerful economy of scale in litigation that smaller players simply cannot match. The strategic necessity of building a diversified litigation portfolio became a primary driver of M&A. Larger companies acquired smaller ones not just for their products or manufacturing capacity, but for their pipeline of ANDAs and potential Paragraph IV opportunities. Consolidation was the logical endpoint of a system that rewards not just manufacturing efficiency, but the ability to wage and withstand a sustained, multi-front legal war.

This evolution also led to a profound globalization of the supply chain. In the relentless pursuit of lower costs to compete in an increasingly price-sensitive market, manufacturing of both APIs and finished drug products shifted overseas, primarily to lower-cost hubs in India and China.32 While this globalization was key to achieving the massive cost savings celebrated by the healthcare system, it also introduced new layers of complexity and fragility into the supply chain, a vulnerability that would become painfully apparent in the subsequent era of drug shortages.

The Strategic Battlefield: A New Era of Patent Warfare

The Hatch-Waxman Act did more than just create a market; it codified a conflict. By establishing a direct, litigation-based pathway for generics to challenge patents before their expiration, the Act transformed the staid world of pharmaceutical intellectual property into a dynamic and intensely strategic battlefield. Success was no longer just about science or manufacturing; it was about legal acumen, strategic foresight, and the masterful exploitation of the Act’s intricate rules. Over the decades, both sides—the generic challengers and the brand-name innovators—developed sophisticated playbooks, turning the Hatch-Waxman framework into a high-stakes game of corporate chess.

The Challenger’s Playbook: Weaponizing the Paragraph IV Certification

For the generic industry, the Paragraph IV certification became the tip of the spear. It was the mechanism that allowed them to go on the offensive, to proactively seek market entry rather than passively waiting for patents to expire. The strategic value of a successful Paragraph IV challenge, crowned by the lucrative 180-day exclusivity period, was so immense that it justified the significant risks and costs of litigation.22

The process became a well-honed discipline. The first step for any aspiring challenger is deep patent intelligence. Generic firms must meticulously scan the landscape for upcoming opportunities, identifying brand-name drugs with patents that appear vulnerable to a validity or infringement challenge. This requires a sophisticated understanding of patent law, prior art, and pharmaceutical science. It is a process that relies heavily on specialized business intelligence platforms. For instance, services like DrugPatentWatch are indispensable tools for generic portfolio managers, providing comprehensive databases of patents, litigation history, and regulatory statuses that allow companies to identify the most promising Paragraph IV targets and assess the litigation track record of potential brand-name adversaries.40

Once a target is identified, the race is on to be the “first-to-file” a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. This “first-filer” status is the golden ticket to the 180-day exclusivity period, making speed and regulatory precision paramount. Upon filing, the generic company must deliver a detailed notice letter to the brand manufacturer, laying out the full factual and legal basis for its assertion that the patent is invalid or not infringed. This letter is not a mere formality; it is the opening salvo of the legal battle, and its quality can significantly influence the course of the ensuing litigation.

While the risks are substantial—litigation can take years and cost upwards of $5-10 million per case—the potential rewards are transformative. The 180-day exclusivity on a blockbuster drug can generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, more than enough to justify the investment. The high success rate for these challenges, estimated to be around 76% for first-filers, has made this aggressive, litigation-centric strategy the cornerstone of the modern generic business model.

The Innovator’s Counteroffensive: Defending the Monopoly

Faced with this new, aggressive threat, brand-name pharmaceutical companies did not stand idle. They responded by developing an equally sophisticated arsenal of defensive strategies designed to protect their monopolies, delay generic entry, and maximize the revenue from their blockbuster products. These counteroffensives are a masterclass in leveraging every available legal, regulatory, and commercial tool to protect a franchise.

“Evergreening” and “Product Hopping”

Perhaps the most ingenious and controversial of these strategies is the practice known as “evergreening” or “product hopping”.24 This tactic involves making incremental, often non-transformative, changes to a drug product as it nears the end of its patent life and then obtaining new patents on these minor modifications. These changes can include developing a new extended-release formulation, creating a new dosage strength, changing the delivery mechanism (e.g., from a tablet to a film), or even isolating a single active isomer of the original molecule.46

The strategy is not merely legal; it is also a masterclass in market manipulation. The process typically unfolds in a few key steps:

- Develop & Patent: As the patent on the original product (Product A) nears expiration, the innovator develops and patents a slightly modified version (Product B).

- Market Shift: The company then launches a massive marketing campaign aimed at physicians, promoting Product B as the “new and improved” standard of care. This is often accompanied by patient coupon programs and other incentives.

- Withdraw the Original: In the most aggressive form of the strategy, the company may withdraw or severely limit the supply of the original Product A, effectively forcing patients and doctors to switch to the new, patent-protected Product B.

The strategic brilliance of this maneuver lies in how it exploits state-level pharmacy substitution laws. When the patent on Product A finally expires and a generic version becomes available, pharmacists cannot automatically substitute it for prescriptions written for Product B, because the two are not considered bioequivalent. By the time the generic of the original drug launches, the market has already “hopped” to the new product, rendering the generic competitor largely irrelevant.

The industry is rife with famous examples of this strategy in action:

- Nexium: AstraZeneca famously developed Nexium, which is simply the active isomer of its blockbuster heartburn drug Prilosec, and successfully shifted the market just as Prilosec’s patents were expiring, extending its franchise for more than 15 years.45

- Suboxone: The manufacturer extended its monopoly on this opioid addiction treatment by developing a patented film version to replace the original tablet, a move that provided little to no additional therapeutic benefit.

- EpiPen: The life-saving epinephrine drug itself has been off-patent for over a century. Mylan extended its monopoly for decades by obtaining a series of patents on minor “tweaks” to the auto-injector device, allowing the price to balloon from under $100 to over $650.

- Trastuzumab (Herceptin): Roche developed a new, patent-protected subcutaneous formulation of its blockbuster intravenous cancer drug just before the original patent expired. While more convenient for patients, this move effectively split the market and blunted the cost-saving impact of incoming intravenous biosimilars.

“Patent Thickets”

A related strategy, often used in conjunction with the 30-month stay, is the creation of a “patent thicket.” Instead of relying on a single, strong composition-of-matter patent, innovator companies file dozens, sometimes hundreds, of secondary patents covering every conceivable aspect of a drug: its formulation, methods of use, manufacturing processes, and even its metabolites.9

This dense web of intellectual property creates a daunting legal minefield for a generic challenger. To launch its product, the generic company must navigate this thicket, challenging each patent and risking a separate infringement lawsuit for every one. This dramatically increases the cost, complexity, and risk of a Paragraph IV challenge. Furthermore, before the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 limited the practice, brands could trigger a new 30-month stay for each new patent they sued on, effectively “stacking” delays and keeping generics off the market for years. While that specific tactic is now restricted, the patent thicket remains a powerful tool for deterring and delaying competition.

“Pay-for-Delay” (Reverse Payment Settlements)

When a generic challenger could not be deterred by a patent thicket, some brand-name companies turned to a more direct approach: they paid them to go away. In a “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” settlement, the brand-name patent holder pays the generic challenger a substantial sum of money. In exchange, the generic company agrees to drop its patent challenge and delay the launch of its product for a specified period.16

These agreements were a win-win for the two companies. The brand maintained its monopoly profits for several more years, and the generic received a guaranteed, risk-free payment that was often more than it could have hoped to earn from competing in the market. The only loser was the consumer, who was denied access to lower-cost medicine. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) aggressively challenged these deals as anticompetitive, estimating they cost the healthcare system $3.5 billion annually.44 This fight would eventually escalate all the way to the Supreme Court, leading to a landmark ruling that fundamentally reshaped the legality of these settlements.

The “Authorized Generic” Gambit

The final and perhaps most subtle weapon in the innovator’s arsenal is the “authorized generic” (AG). An AG is a pharmaceutical product that is identical in every way to the brand-name drug—same active and inactive ingredients, same manufacturing process—but is marketed without the brand name on the label.53 It is, in essence, the brand-name company launching its own generic.

The strategic power of the AG lies in its timing. Because it is the same approved drug, it does not require a separate ANDA and can be launched at any time, including during a first-filer’s sacred 180-day exclusivity period. The launch of an AG during this period is devastating to the generic challenger, as it instantly turns their hard-won monopoly into a duopoly. FTC studies have found that the presence of an AG can slash a first-filer’s revenues during the exclusivity period by 40% to 52%.56

This creates a powerful paradox. The AG is, on its face, a pro-competitive tool; a second generic on the market drives prices down further for consumers. However, its primary strategic value for the brand company is as an anti-competitive threat. In settlement negotiations, the brand can offer a “no-AG agreement”—a promise not to launch an authorized generic—as a valuable, non-cash form of payment to induce the generic to accept a longer delay in entry.44 It is a classic example of weaponizing a pro-competitive tool to achieve an anti-competitive outcome, a practice that has also drawn significant legal scrutiny.

The Third Branch: How Courts and Regulators Have Shaped the Hatch-Waxman Legacy

The Hatch-Waxman Act, for all its intricate design, was not a static, self-executing law. It was a blueprint for a dynamic system, and its real-world application has been continuously shaped, refined, and redefined over the past four decades by the third branch of government—the judiciary—and by the very regulatory agencies tasked with its implementation. The original “grand bargain” was elegant but, in many ways, naive. It failed to anticipate the sheer ingenuity with which its provisions could be strategically “gamed” by industry players. Consequently, the legal and regulatory history of Hatch-Waxman is a story of continuous adaptation, a decades-long process of identifying and patching exploits as they emerge.

Landmark Litigation: Defining the Rules of Engagement

The federal courts, from district levels up to the Supreme Court, have served as the primary arbiters of the Hatch-Waxman battlefield. Their rulings in a series of landmark cases have clarified ambiguities, closed loopholes, and fundamentally altered the strategic calculus for both innovator and generic companies.

FTC v. Actavis, Inc. (2013): This Supreme Court decision was a watershed moment in the fight against “pay-for-delay” settlements. For years, lower courts had been split on whether these agreements were legal. Some, using a “scope of the patent” test, argued that as long as the settlement didn’t delay generic entry beyond the patent’s expiration date, it was immune from antitrust law. The FTC, on the other hand, argued they were presumptively illegal. The Supreme Court charted a middle course. In its 2013 ruling, the Court rejected the “scope of the patent” test, declaring that large and unjustified reverse payments could indeed violate antitrust laws.58 However, it stopped short of declaring them presumptively illegal, instead mandating that they be evaluated under a “rule of reason” analysis. This fact-intensive inquiry requires courts to weigh the pro-competitive benefits of a settlement against its anti-competitive harms.58 The

Actavis decision didn’t outlaw pay-for-delay deals, but it opened them up to significant legal challenges from the FTC and private plaintiffs, making them a much riskier strategy for pharmaceutical companies.

King Drug Co. of Florence, Inc. v. Smithkline Beecham Corp. (2015): Innovator companies, responding to the Actavis ruling, quickly pivoted from explicit cash payments to more subtle forms of compensation in their settlements. One of the most common was the “no-authorized generic” agreement. The question then became: does a non-cash payment of significant value also trigger antitrust scrutiny? The Third Circuit Court of Appeals answered with a resounding “yes.” In King Drug, the court held that GSK’s promise not to launch an authorized generic version of Lamictal constituted a “large transfer of value” to the generic challenger, Teva.63 The court reasoned that this promise was functionally equivalent to a cash payment, as it preserved a lucrative monopoly for the generic during its exclusivity period.65 This decision was critical because it extended the logic of

Actavis beyond simple cash transactions, signaling to the industry that courts would look at the economic substance, not just the form, of a settlement.

Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Warner Chilcott PLC (2016): This case provided a crucial counterpoint in the evolving law of “product hopping.” Mylan alleged that Warner Chilcott had engaged in anticompetitive product hopping with its acne drug, Doryx, by making a series of minor reformulations. However, the Third Circuit affirmed the lower court’s dismissal of the case.67 The court found that Warner Chilcott’s conduct was not anticompetitive for two key reasons: first, Mylan had failed to prove that the brand had monopoly power in a properly defined market (which included all oral tetracyclines, not just Doryx); and second, the generic was never truly foreclosed from the market and the product changes had legitimate, pro-competitive justifications, such as improved safety and patient convenience.68 The

Doryx decision demonstrated that not all product hops are illegal and that these cases are highly fact-specific, requiring plaintiffs to clear high hurdles related to market definition and anticompetitive harm.

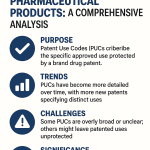

Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. v. Novo Nordisk A/S (2012): This Supreme Court case addressed a highly technical but strategically vital part of the Hatch-Waxman framework: the “use codes” in the Orange Book. Novo Nordisk held a patent on only one of three approved uses for its diabetes drug, Prandin. However, it submitted a broad use code to the FDA that implied its patent covered all three uses. This prevented Caraco from using a “section viii statement” to “carve out” the patented use from its label and launch its generic for the unpatented uses.70 The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of Caraco, holding that the Act’s counterclaim provision allows generic companies to sue to force a brand manufacturer to correct an inaccurate or overbroad use code.72 This was a significant victory for generics, preventing brand companies from using misleading Orange Book listings as a tool to improperly block competition.

Legislative and Regulatory Tune-Ups

In parallel with the courts, Congress and the FDA have periodically stepped in to patch the Hatch-Waxman Act and address its evolving challenges.

Generic Drug Enforcement Act of 1992: In the late 1980s, the nascent generic industry was rocked by a major scandal involving bribery and fraud, with some companies submitting fraudulent data in their ANDAs and some FDA officials accepting bribes to expedite approvals. In response, Congress passed this Act, which imposed stiff debarment penalties and other sanctions for illegal acts related to the ANDA process, helping to restore public confidence in the quality and integrity of generic drugs.11

Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003: This massive piece of legislation, best known for creating the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit, also contained several crucial amendments to Hatch-Waxman designed to close loopholes that brands had been exploiting.11 Most importantly, the MMA clarified that a brand-name company is entitled to only

one 30-month stay per drug, regardless of how many patents it lists or sues on. This put an end to the strategy of “stacking” multiple stays to create years of delay. The MMA also required that all patent settlement agreements be filed with the FTC and the Department of Justice, giving regulators the transparency needed to identify and challenge potentially anticompetitive deals.52

Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA): By the early 2010s, the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs was drowning in a massive backlog of ANDA applications, with review times stretching to 30 months or more. This backlog itself had become a significant barrier to competition. First passed in 2012 and reauthorized every five years since, GDUFA authorized the FDA to collect user fees from the generic industry to fund the hiring of more reviewers and the modernization of the review process.1 GDUFA has been highly successful, dramatically reducing the ANDA backlog and shortening median approval times, thereby accelerating the entry of new generics to market.

Recent FDA and FTC Initiatives: In recent years, regulatory agencies have become even more proactive. The FDA’s Drug Competition Action Plan (DCAP), announced in 2017, is a multi-pronged effort to encourage generic competition, particularly for complex drugs and drugs with no existing generic competitors.11 As part of this plan, the FDA created the

Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway, which provides expedited review and a 180-day exclusivity incentive for generics of drugs that have “inadequate generic competition”.11 Concurrently, the FTC has ramped up its enforcement efforts, challenging improper Orange Book patent listings and continuing its scrutiny of pay-for-delay settlements.77

This continuous cycle of strategic exploitation followed by judicial or legislative correction is the defining narrative of the Hatch-Waxman legacy. The framework is not a static set of rules but a living, breathing ecosystem in a constant state of flux. For industry participants, this means that a successful strategy requires not just compliance with the current rules, but an anticipation of the next loophole and the inevitable patch that will follow.

Unforeseen Fault Lines: Modern Challenges and Unintended Consequences

Forty years on, the Hatch-Waxman Act has matured from a disruptive piece of legislation into the foundational bedrock of the U.S. pharmaceutical market. Its success in fostering a competitive generic industry and containing costs is undeniable. Yet, this very success has given rise to a new set of complex and often paradoxical challenges—unforeseen fault lines in the market’s structure that now pose significant threats to the stability of the nation’s drug supply and the integrity of the competitive environment. These modern problems are not failures of the Hatch-Waxman model, but rather the unintended consequences of its design.

The Drug Shortage Crisis

One of the most pressing and paradoxical challenges is the chronic crisis of drug shortages. For years, the U.S. healthcare system has been plagued by persistent shortages of essential, life-saving medicines, particularly older, sterile injectable drugs used in hospitals, such as chemotherapy agents, anesthetics, and electrolytes.32 While the causes are multifactorial, a 2019 FDA task force report identified the primary root cause as economic: a market that fails to reward manufacturers for mature and robust quality systems and a lack of incentives to produce less profitable drugs.

This economic fragility is a direct downstream effect of the intense price competition that Hatch-Waxman was designed to create. For many older, off-patent drugs with multiple generic manufacturers, the market becomes a race to the bottom on price. This relentless downward pressure squeezes profit margins to unsustainable levels, sometimes just pennies per dose.8 When profitability is so low, manufacturers have little financial incentive to invest in upgrading aging facilities, maintaining redundant manufacturing capacity, or building resilient supply chains. The system becomes hyper-efficient but dangerously brittle.

In this environment, a single disruption—a manufacturing line failing an FDA inspection for quality control issues, a problem with a single supplier of a key raw material, or an unexpected surge in demand—can knock out a significant portion of the nation’s supply. Because other manufacturers are also operating at maximum capacity with no excess inventory, they are unable to ramp up production to cover the shortfall, leading to a prolonged, nationwide shortage. Thus, the very mechanism that delivered trillions in savings has also created a market structure that is inherently vulnerable to supply disruptions, putting patient care at risk.

Allegations of Price-Fixing and Collusion

At the opposite end of the spectrum from the race-to-the-bottom pricing that causes shortages is the equally troubling phenomenon of alleged price-fixing and collusion among generic manufacturers. In one of the largest antitrust investigations in U.S. history, the Department of Justice and attorneys general from nearly every state have filed sweeping lawsuits accusing dozens of generic drug companies of engaging in a massive conspiracy to artificially inflate the prices of hundreds of drugs.

The lawsuits allege that, contrary to the competitive ethos of the Hatch-Waxman Act, executives at competing firms colluded through informal meetings at trade shows, text messages, and phone calls to allocate markets and coordinate price increases for numerous generic drugs, including common treatments like the antibiotic doxycycline and the thyroid medication levothyroxine. In some cases, prices for these essential medicines surged by over 1,000%.

These seemingly contradictory phenomena—cutthroat competition leading to shortages on one hand, and illegal collusion to fix prices on the other—can be understood as two sides of the same coin. They are both rational, if sometimes unlawful, corporate responses to the extreme economic pressures created by the mature Hatch-Waxman market. For a given drug, manufacturers face a stark choice: either compete on price until the product is no longer profitable, leading them to potentially exit the market and contribute to a shortage, or, as alleged, collude with competitors to artificially stabilize prices and ensure mutual survival. The structure of the market itself, by pushing prices toward an unsustainable floor, creates powerful incentives for companies to seek ways to exit the competitive “death spiral.”

The Globalization and Fragility of the Supply Chain

The relentless pressure to reduce costs has also driven a profound geographic shift in the pharmaceutical supply chain. To remain competitive, U.S.-based generic companies have increasingly outsourced the manufacturing of both their final drug products and, more critically, their active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) to overseas facilities, primarily in India and China.32 Today, an estimated 86% of APIs and 62% of finished products are produced abroad.

While this globalization has been a key enabler of low-cost generics, it has introduced significant new vulnerabilities. The concentration of API manufacturing in a few geographic regions makes the entire U.S. drug supply susceptible to disruptions from natural disasters, geopolitical tensions, trade disputes, or public health crises in those countries. As the COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated, a lockdown in a single region of China or India can have immediate and severe ripple effects on the availability of critical medicines in the United States.

Furthermore, this extended and complex supply chain presents significant oversight challenges for the FDA. Ensuring consistent quality and compliance with U.S. manufacturing standards across thousands of foreign facilities is a monumental logistical task. These fault lines—the economic fragility leading to shortages, the alleged collusion to escape price wars, and the geographic concentration of the supply chain—represent the complex and often-unintended legacy of the Hatch-Waxman Act’s success. They are the defining challenges for the next era of pharmaceutical policy.

Charting the Future: From Generics to Biosimilars and Beyond

As the small-molecule generic market has matured, the next great frontier of pharmaceutical competition has emerged: biologics. These large, complex molecules, produced in living systems rather than through chemical synthesis, represent the fastest-growing and most expensive segment of the drug market. The question of how to apply the principles of the Hatch-Waxman Act to this new class of therapies has dominated the policy debate for the last 15 years, leading to a new legislative framework and a new set of strategic challenges.

The answer came in 2009 with the passage of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), which was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act. The BPCIA created, for the first time, an abbreviated approval pathway for “biosimilars”—products that are shown to be highly similar to, and have no clinically meaningful differences from, an existing FDA-approved biologic, known as the “reference product”.

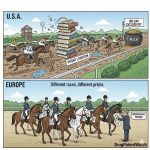

Conceptually, the BPCIA is a “Hatch-Waxman 2.0,” designed to bring competition and cost savings to the world of biologics. However, the BPCIA is a far more complex and innovator-friendly piece of legislation than its predecessor, reflecting two decades of lessons learned by the brand-name industry from the Hatch-Waxman experience. The differences are stark:

- Exclusivity Period: Where Hatch-Waxman provided a five-year data exclusivity for new chemical entities, the BPCIA grants the innovator biologic a much longer 12-year period of exclusivity before the FDA can approve a biosimilar.

- Litigation Process: Instead of the relatively straightforward Orange Book and Paragraph IV certification system, the BPCIA established a convoluted, multi-step process of information exchange between the innovator and the biosimilar applicant known as the “patent dance.” This process is designed to identify and litigate relevant patents before the biosimilar launches, but its complexity has been a source of significant legal dispute.

- Interchangeability: The BPCIA created a higher standard of “interchangeability,” which requires a biosimilar to demonstrate that it can be expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient and that it can be switched back and forth without issue. Only an interchangeable biosimilar can be automatically substituted at the pharmacy level, creating a higher bar for biosimilar manufacturers to clear to achieve the same market access that small-molecule generics enjoy.

These higher barriers to entry—longer exclusivities, more complex litigation, and a stricter standard for substitution—can be seen as a direct result of successful lobbying by the innovator biotechnology industry, which studied the success of generics under Hatch-Waxman and sought to create a system that was more protective of their interests. As a result, the uptake of biosimilars in the U.S. has been slower, and the price reductions less dramatic, than what was seen in the early days of small-molecule generics.2 While biosimilars are beginning to generate significant savings—over $36 billion since 2015—the path to a fully competitive market is proving to be longer and more arduous.

Meanwhile, the original Hatch-Waxman framework continues to evolve. Current legislative and policy debates are focused on closing the remaining loopholes that brand-name companies exploit to delay competition. These include proposals to curb the abuse of FDA-mandated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) to block generics from obtaining samples for bioequivalence testing, and reforms to the “citizen petition” process to prevent its use as a last-minute tactic to delay ANDA approvals.13

Furthermore, the entire pharmaceutical pricing ecosystem is being reshaped by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. For the first time, the IRA grants the federal government the authority to negotiate prices for certain high-cost drugs covered by Medicare. This introduction of government price-setting could fundamentally disrupt the delicate balance of incentives at the heart of the Hatch-Waxman Act. For example, if a government-negotiated price for a brand-name drug is already deeply discounted, it could significantly diminish the potential return on investment for a generic or biosimilar company considering a patent challenge, thereby weakening the incentive for competition that has been the engine of cost savings for 40 years.

The future of the generic and biosimilar industry will be defined by its ability to navigate these new realities: the complex pathway for biosimilars, the ongoing legislative efforts to refine the Hatch-axman Act, and the uncharted territory of government price negotiation. The grand bargain of 1984 is no longer the only game in town, and its principles must now coexist within a much more crowded and complicated policy landscape.

Conclusion: An Enduring, Evolving Legacy

Forty years after its enactment, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act remains the single most influential piece of legislation in the history of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry. Its legacy is a study in contrasts: a story of resounding success and profound, unintended consequences. It is at once a testament to the power of well-crafted policy to drive competition and a cautionary tale about the ability of market forces to exploit even the most carefully designed systems.

The Act’s primary achievement is monumental and undeniable. It took a moribund generic market, shackled by impossible regulatory burdens, and transformed it into a global powerhouse. By creating the ANDA pathway, Hatch-Waxman unleashed a wave of competition that has saved the American healthcare system trillions of dollars, fundamentally altering the economic calculus of prescription medicine. The fact that over 90% of prescriptions are now filled with affordable, high-quality generics is a direct and enduring tribute to the Act’s success. It has made essential medicines more accessible and affordable for millions of Americans, a public health victory of the highest order.

Yet, this triumph came with a complex and often-troubling set of side effects. The Act’s adversarial framework turned the pharmaceutical industry into a perpetual battlefield, where legal strategy became as important as scientific innovation. It gave rise to a sophisticated corporate arms race, with innovators developing an arsenal of defensive tactics like “evergreening,” “patent thickets,” and “pay-for-delay” settlements, and generics mastering the high-stakes art of the Paragraph IV patent challenge. The result has been four decades of relentless, high-stakes litigation that has enriched legions of lawyers and continuously tested the boundaries of patent and antitrust law.

Moreover, the very success of the Act’s hyper-competitive model has created new forms of market instability. The relentless downward pressure on prices has made the supply chain for many essential generic drugs fragile and prone to shortages. At the same time, it has created incentives for the very anticompetitive behavior—allegations of widespread price-fixing—that the Act was designed to prevent.

Today, the world that Hatch and Waxman built is facing a new era of challenges. The rise of biologics has necessitated a new, more complex framework in the BPCIA. And the introduction of government price negotiation under the Inflation Reduction Act threatens to disrupt the delicate balance of incentives that has governed the industry for a generation.

Ultimately, the enduring legacy of the Hatch-Waxman Act is the central tension it sought to resolve: the delicate balance between rewarding innovation and ensuring affordable access. That fundamental challenge remains as relevant today as it was in 1984. The grand bargain, it turns out, was not a final settlement, but the beginning of a permanent, evolving negotiation that continues to shape the health and wealth of the nation.

Key Takeaways

- The “Grand Bargain” Created a Battlefield: The Hatch-Waxman Act was a compromise that created a streamlined pathway for generic drugs (the ANDA) in exchange for new protections for innovators (patent term restoration, market exclusivities). This structure institutionalized a permanent, strategic conflict between the two business models.

- Economic Impact Was Transformative: The Act was spectacularly successful in its primary goal, increasing generic prescription share from 19% in 1984 to over 90% today and generating over $3 trillion in healthcare savings in the last decade alone.

- The Business Model Shifted to Litigation: The Act’s Paragraph IV patent challenge and 180-day exclusivity incentive transformed the generic industry from a passive manufacturing sector into an aggressive, litigation-focused enterprise where patent intelligence is a core strategic asset.

- Innovators Developed Sophisticated Counter-Strategies: Brand-name companies responded with a powerful playbook to delay competition, including “evergreening” (minor product changes), “patent thickets” (dense webs of secondary patents), “pay-for-delay” settlements, and the strategic use of “authorized generics.”

- The System is in Constant Flux: The history of Hatch-Waxman is a cycle of strategic exploitation of loopholes followed by corrective action from courts (e.g., FTC v. Actavis) and legislators (e.g., the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003). Navigating this landscape requires anticipating the next strategic move and regulatory response.

- Success Created Unintended Consequences: The Act’s hyper-competitive model has driven down profit margins on many older generics, leading to a fragile supply chain and chronic drug shortages. These same economic pressures are also cited as a driver for the alleged price-fixing and collusion among generic manufacturers.

- The Future is More Complex: The rise of biologics led to the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), a more complex and innovator-friendly version of Hatch-Waxman. The introduction of government price negotiation under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) adds another layer of complexity that could disrupt the traditional balance of incentives for both brand and generic/biosimilar companies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the fundamental difference between patent protection and the market exclusivity granted under the Hatch-Waxman Act?

This is a critical distinction that often causes confusion. Patent protection is a form of intellectual property granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) that gives an inventor the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling their invention for a limited time (typically 20 years from the filing date). It is a broad property right. Market exclusivity, on the other hand, is a statutory protection granted by the FDA that prevents the agency from approving a competing drug application (like an ANDA) for a specific period.3 The two systems run in parallel and can overlap, but they are independent. A drug can have patent protection but no exclusivity, exclusivity but no patent, both, or neither. For example, the five-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity is granted upon approval of a new drug, regardless of how much time is left on its patents. This provides a minimum floor of market protection that is separate from the patent system.

2. Why would a brand-name company ever launch an “authorized generic” to compete with itself? Isn’t that just cannibalizing its own sales?

Launching an authorized generic (AG) is a sophisticated strategic decision driven by profit maximization in the face of imminent generic competition. While it seems counterintuitive, it’s about choosing the most profitable outcome among several less-than-ideal options. When the first generic challenger launches with 180-day exclusivity, the brand’s monopoly is broken. The brand now faces a choice:

- Option A: Do nothing and let the single generic competitor capture a large portion of the market.

- Option B: Launch an AG to compete directly with the first generic.

By launching an AG, the brand company enters the generic market itself. While this does accelerate the erosion of its high-priced brand sales, it allows the company to capture a significant share of the new, lower-priced generic market—revenue it would have otherwise ceded entirely to the generic competitor. The calculation often shows that the combined revenue from the declining brand sales plus the new AG sales is greater than the revenue from brand sales alone in a market with a single generic competitor. It’s a defensive move to retain as much total market revenue as possible after the monopoly has been breached.

3. The Act was designed to increase competition, so how did it lead to allegations of widespread price-fixing among generic companies?

This paradox stems from the extreme economic pressures the Act creates in mature generic markets. For a newly off-patent drug, especially one with few competitors, the profit potential is high. However, for older drugs with many generic manufacturers (e.g., common oral solids), the competition becomes so intense that prices are driven down to near the marginal cost of production, making them minimally profitable.8 The lawsuits allege that in this environment, some manufacturers chose to illegally collude rather than compete in what they saw as a “race to the bottom”. According to the allegations, they conspired to allocate market share and coordinate on price increases to ensure stable, predictable profits. In this view, the alleged price-fixing was not a sign of a lack of competition, but rather an unlawful reaction to the

hyper-competition that the Hatch-Waxman model successfully created.

4. What is the “patent dance” under the BPCIA, and how does it differ from the Hatch-Waxman litigation process?

The “patent dance” is the colloquial term for the complex, multi-step process of information exchange and patent litigation established by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) for biosimilars. It is significantly different and more intricate than the Hatch-Waxman process for small-molecule generics.

- Hatch-Waxman: The process is relatively straightforward. The brand lists patents in the Orange Book. The generic files an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. The brand has 45 days to sue, which triggers an automatic 30-month stay.

- BPCIA “Patent Dance”: The process is a series of prescribed steps with strict timelines. The biosimilar applicant provides its application and manufacturing information to the innovator. The innovator provides a list of patents it believes could be infringed. The parties exchange detailed legal arguments about infringement and validity. They then negotiate a list of patents to be litigated in a first wave of litigation. There is no Orange Book equivalent and no automatic 30-month stay. The complexity and prescribed nature of the “dance” were intended to create a more structured process for resolving disputes over the many patents that can cover a complex biologic, but it has also been criticized for being cumbersome and creating its own set of strategic games.

5. How has the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) changed the strategic calculations for both brand and generic companies under Hatch-Waxman?

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) introduces a new and potentially disruptive variable into the Hatch-Waxman ecosystem: government price negotiation for certain drugs under Medicare. This could alter strategic calculations in several ways. For brand-name companies, the threat of having a drug selected for negotiation—which could lead to significant price reductions nine years (for small molecules) or 13 years (for biologics) after approval—might change R&D investment decisions and life-cycle management strategies. For generic and biosimilar companies, the IRA poses a significant challenge to the core incentive of the Paragraph IV pathway. The profitability of challenging a patent is based on being able to enter the market and sell a product at a discount to the high, pre-negotiation brand price. If the government has already negotiated that brand price down significantly, the potential profit margin for the generic challenger shrinks dramatically. This could reduce the incentive to engage in costly patent litigation, potentially leading to fewer challenges and, ironically, less competition in the long run. The full impact is still unknown, but the IRA fundamentally alters the pricing landscape upon which the Hatch-Waxman “grand bargain” has operated for 40 years.

References

- 40th Anniversary of the Generic Drug Approval Pathway | FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/40th-anniversary-generic-drug-approval-pathway

- The Transformation of the US Generic Drug Industry After the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/development-of-the-generic-drug-industry-in-the-us-after-the-hatch-waxman-act-of-1984/

- Hatch-Waxman 101 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-101-3/

- Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drug_Price_Competition_and_Patent_Term_Restoration_Act

- What is Hatch-Waxman Act? – DDReg Pharma, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.ddregpharma.com/what-is-hatch-waxman-act

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Quarter Century Later – UM Carey Law, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www2.law.umaryland.edu/marshall/crsreports/crsdocuments/R41114_03132013.pdf

- Hatch-Waxman Turns 30: Do We Need a Re-Designed Approach for the Modern Era? – Yale Law School Open Scholarship Repository, accessed August 3, 2025, https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/5929/Kesselheim_2.pdf

- Is the Era of Generics Over? A Critical Look at an Evolving Market and the Potential Oasis for Few – Amarin Technologies, accessed August 3, 2025, https://amarintech.com/is-the-era-of-generics-over-a-critical-look-at-an-evolving-market-and-the-potential-oasis-for-few/

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman – Trillions in Savings for Patients, accessed August 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/press-releases/40-years-hatch-waxman-trillions-savings-patients/

- 2024 U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report, accessed August 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2024-savings-report/

- Timeline: Generic medicines in the US | USP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.usp.org/our-impact/generics/timeline-of-generics-in-us

- Generic Drugs: History, Approval Process, and Current Challenges – U.S. Pharmacist, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/generic-drugs-history-approval-process-and-current-challenges

- GENERIC DRUGS IN THE UNITED STATES: POLICIES TO …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6355356/

- Hatch-Waxman Overview | Axinn, Veltrop & Harkrider LLP, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.axinn.com/en/insights/publications/hatch-waxman-overview

- Full article: Forces influencing generic drug development in the United States: a narrative review, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1186/s40545-016-0079-1

- Abuse of the Hatch-Waxman Act: Mylan’s Ability to Monopolize Reflects Weaknesses – BrooklynWorks, accessed August 3, 2025, https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1241&context=bjcfcl

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Primer – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html

- Seizing the Opportunity – PMC, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4115321/

- A little known law that made drugs more affordable – YouTube, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zku4Txlshk8

- 40 Years of Hatch-Waxman: What is the Hatch-Waxman Act? | PhRMA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://phrma.org/blog/40-years-of-hatch-waxman-what-is-the-hatch-waxman-act

- Challenging Patents To Promote Timely Generic Drug Entry: The Second Look Act And Other Options – PORTAL, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.portalresearch.org/blog/challenging-patents-to-promote-timely-generic-drug-entry-the-second-look-act-and-other-options

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- Hatch-Waxman 201 – Fish & Richardson, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/blogs/hatch-waxman-201-3/

- Earning Exclusivity: Generic Drug Incentives and the Hatch-‐Waxman Act1 C. Scott – Stanford Law School, accessed August 3, 2025, https://law.stanford.edu/index.php?webauth-document=publication/259458/doc/slspublic/ssrn-id1736822.pdf

- The Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Incentive Accelerates …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-hatch-waxman-180-day-exclusivity-incentive-accelerates-patient-access-to-first-generics/

- Recent trends in brand-name and generic drug competition – Duke University, accessed August 3, 2025, https://fds.duke.edu/db/attachment/2575

- Hatch-Waxman Act | Practical Law, accessed August 3, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/9-543-2565?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- Drug Competition Series – Analysis of New Generic Markets Effect of Market Entry on Generic Drug Prices – HHS ASPE, accessed August 3, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- HOW INCREASED COMPETITION FROM GENERIC DRUGS HAS AFFECTED PRICES AND RETURNS IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY JULY 1998 – Congressional Budget Office, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/6xx/doc655/pharm.pdf

- Report: 2022 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report, accessed August 3, 2025, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/reports/2022-savings-report/

- Estimating Cost Savings from New Generic Drug Approvals in 2022 | September, 2024 – FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/182435/download

- The Evolution of Supply and Demand in Markets for Generic Drugs …, accessed August 3, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8452364/

- Frequently Asked Questions about Drug Shortages – FDA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-shortages/frequently-asked-questions-about-drug-shortages

- Mylan – e-WV, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/entries/1497

- Mylan – Wikipedia, accessed August 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mylan

- Our History – Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.tevausa.com/our-company/article-pages/our-history/

- TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES LTD. History – Founding, Milestones & Growth Journey – BCC Research, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.bccresearch.com/company-index/profile/teva-pharmaceutical-industries-ltd/history

- Mylan (Viatris) History and Track Record | PPTX | Pharmaceutical Industry – SlideShare, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/mylan-viatris-history-and-track-record/249908311

- Domestic pharma industry may face setback if US imposes tariffs, accessed August 3, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/domestic-pharma-industry-may-face-setback-if-us-imposes-tariffs/articleshow/123002989.cms

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed August 3, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- DrugPatentWatch Pricing, Features, and Reviews (Jul 2025) – Software Suggest, accessed August 3, 2025, https://www.softwaresuggest.com/drugpatentwatch