Introduction: The High Cost of a Small Bottle

It’s one of the most glaring paradoxes in American healthcare, a statistical riddle that costs patients, employers, and the government hundreds of billions of dollars every year. On the one hand, the U.S. pharmaceutical market is a resounding success story of efficiency and cost-savings. The vast majority of prescriptions filled—a staggering 80% to 90%—are for low-cost, highly effective generic drugs . This is the result of decades of policy designed to foster a competitive marketplace, and it has saved the healthcare system trillions of dollars over the years. Yet, if you look at where the money actually goes, the picture flips entirely on its head. That same 80% of total prescription drug spending is consumed by a relatively small sliver of the market: brand-name drugs .

How can this be? How can a system be dominated by low-cost products in terms of volume but high-cost products in terms of expenditure? This isn’t just a curious anomaly; it is the central, defining feature of the American pharmaceutical landscape. It’s the economic engine that drives record profits for some of the world’s largest corporations while simultaneously pushing millions of American families to the financial brink. It’s the reason a vial of life-saving insulin can cost more than a monthly mortgage payment and why a new cancer therapy can launch with a price tag that rivals the cost of a house.

This report will argue that this immense overspend on branded drugs is not the result of a single market failure, a greedy CEO, or a flawed policy. Rather, it is the predictable, logical outcome of a complex and deeply interconnected system of incentives, regulations, and strategic business practices that has been built and refined over decades. It is a system where the societal bargain of granting temporary monopolies to spur innovation has been masterfully extended and exploited; where a labyrinth of opaque intermediaries thrives on complexity and high list prices; and where a fragmented purchasing landscape has, until very recently, lacked the power to say “no.”

To truly understand this paradox, we must deconstruct this system piece by piece. We will begin by quantifying the scale of the problem, comparing U.S. drug prices not only to the rest of the world but also within our own borders. We will then pull back the curtain on the engine of exclusivity—the intricate world of patents, “evergreening,” and “patent thickets”—that allows brand-name drugs to fend off competition for far longer than intended. From there, we will navigate the maze of the pharmaceutical supply chain, exposing the perverse incentives of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and the rebate system that often reward high prices. We will explore how billions in direct-to-consumer advertising shapes patient demand and influences prescribing habits. Finally, we will examine the devastating consequences of this system on patients and the economy, and analyze the landmark policy changes, like the Inflation Reduction Act, that are beginning to reshape this landscape. For business leaders and pharmaceutical professionals, understanding these interconnected parts is no longer just an academic exercise; it is the key to navigating the market, mitigating risk, and identifying the strategic opportunities that will define the next decade of the industry.

By the Numbers: Quantifying the U.S. Price Anomaly

Before dissecting the machinery of the U.S. pharmaceutical market, it is essential to grasp the sheer magnitude of the pricing disparity. The numbers are not just large; they are staggering, painting a picture of a nation that stands in stark isolation from its economic peers. This price anomaly exists on two fronts: externally, when compared to the rest of the developed world, and internally, in the widening chasm between the cost of brand-name drugs and their generic counterparts.

A Global Outlier: The International Price Chasm

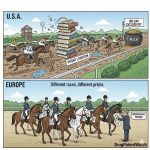

The data is unequivocal: Americans pay, by far, the highest prices for prescription drugs in the world. This is not a marginal difference but a chasm that separates the U.S. from every other high-income nation. According to a 2022 analysis by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), overall drug prices in the United States were nearly 2.78 times as high as in comparable countries . When isolating for brand-name drugs, the gap becomes even more pronounced. Even after accounting for the confidential rebates and discounts that are central to the U.S. system, American prices for branded products were at least 3.22 times higher than those in peer nations .

Independent research confirms this stark reality. A comprehensive study by the RAND Corporation found that U.S. prescription drug prices averaged 2.56 times those seen in 32 other nations. For brand-name drugs, the primary driver of the overspend, U.S. prices were an astonishing 3.44 times higher. As the study’s lead author, Andrew Mulcahy, bluntly stated, “It’s just for the brand name drugs that we pay through the nose” .

A 2020 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) provides a concrete illustration of this gap. Examining 20 selected brand-name drugs, the GAO found that U.S. retail prices were more than two to four times higher than those in Australia, Canada, and France. Critically, the GAO noted that this comparison likely understates the true difference. Their analysis compared U.S. net prices (the price after rebates are paid) to the publicly available gross prices in the other countries. Since other countries also have their own systems of confidential discounts, the actual gap between what is ultimately paid in the U.S. versus elsewhere is almost certainly even larger. For some drugs, the difference was as high as tenfold .

This international price gap is not merely a quantitative difference; it reflects a fundamental philosophical and structural divergence in how healthcare is approached. In countries like Australia and France, prescription drug pricing is nationally regulated, and coverage is universal . Their governments act as a single, powerful purchaser, leveraging the negotiating power of their entire population to demand lower prices from manufacturers. They often employ formal health technology assessments to determine what a drug is worth based on its clinical benefit, effectively treating drug pricing as a public utility that must be controlled.

In stark contrast, the U.S. has historically operated a fragmented system. It is a patchwork of thousands of private insurance plans, self-insured employers, and multiple government programs, each negotiating separately. Until the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the largest single purchaser—Medicare—was legally forbidden from negotiating prices directly. This lack of a unified, countervailing power creates a market uniquely vulnerable to the monopoly pricing power granted by patents. The price difference, therefore, is not a reflection of a drug’s higher intrinsic value in the U.S. market; it is a direct outcome of a systemic inability to constrain that monopoly power.

The Domestic Divide: Brand vs. Generic Economics

The pricing paradox becomes even clearer when we look inside the U.S. market itself. Here, we see two distinct and opposing economic forces at work. On one side, the generic drug market is a model of competitive efficiency. On the other, the brand-name market operates like a luxury goods sector, with prices that seem untethered from traditional economic pressures.

The success of the generic market is undeniable. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act created an abbreviated pathway for generic drug approval, unleashing a wave of competition that has been a powerful force for cost containment. According to the FDA, the entry of even a few generic competitors can lead to significant price reductions below the brand price . Data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) vividly illustrates this trend. Between 2009 and 2018, as the share of generic prescriptions filled in Medicare Part D soared from 72% to 90%, the average net price of a generic prescription fell from $22 to $17. This increased use of lower-cost generics is the primary reason that overall growth in drug spending slowed significantly in the mid-2000s .

Yet, during that same period, the price of brand-name drugs moved in the exact opposite direction, and at a breathtaking pace. The CBO found that from 2009 to 2018, the average net price of a brand-name prescription in Medicare Part D more than doubled, rocketing from $149 to $353. This dynamic is the reason why, even with generics accounting for 9 out of every 10 prescriptions, brand-name drugs still command 80% of the total spending . The savings generated by the hyper-competitive generic market are being consumed by the hyper-inflationary branded market.

This divergence is not a coincidence; the two trends are causally linked. The very effectiveness of the Hatch-Waxman Act in creating a robust and predictable pathway for generic competition created what the industry famously calls the “patent cliff.” For a brand manufacturer, the revenue from a blockbuster drug doesn’t gradually decline over time; it plummets, often by 80% or more, in the year immediately following the entry of the first generic competitor. To compensate for this guaranteed and severe future loss of revenue, and to satisfy investor demands for perpetual growth, manufacturers adapted their strategy. They began to focus intensely on maximizing revenue during the finite period of monopoly protection. This was achieved through two primary levers, both identified by the CBO as the key drivers of spending: “higher launch prices for new drugs and growth in the prices of individual drugs already on the market” . In essence, the intense price competition that defines the post-patent period created an equal and opposite reaction of intense price maximization during the pre-patent period. The two phenomena are two sides of the same coin, defining the deep economic divide within the American pharmaceutical market.

The Engine of Exclusivity: Patents, Thickets, and Evergreening

At the heart of the brand-name drug pricing paradox lies the U.S. patent system. It is the legal and economic foundation upon which the entire industry is built, granting the temporary monopolies that allow for premium pricing. Originally conceived as a grand bargain to foster innovation, the system has evolved into a complex strategic battleground where legal maneuvering to extend these monopolies has become as important as the scientific research itself. To understand why Americans overspend, we must first understand how this engine of exclusivity works—and how it is being pushed far beyond its original design.

The Patent Bargain: Innovation vs. Monopoly

The pharmaceutical patent system is, at its core, a societal contract. Developing a new drug is an incredibly risky, time-consuming, and expensive endeavor. The vast majority of compounds that enter preclinical testing never make it to market. To incentivize companies to undertake this massive financial risk, society offers a powerful reward: a patent. A patent grants the innovator the exclusive right to make, use, and sell their invention for a set period, typically 20 years from the date the patent is filed .

During this period of market exclusivity, the manufacturer can charge prices well above the cost of production, free from direct competition. This allows them to recoup their research and development (R&D) investment, reward their shareholders, and, in theory, fund the discovery of the next generation of innovative medicines . In exchange for this temporary monopoly, the inventor must publicly disclose the details of their invention, adding to the collective pool of scientific knowledge that others can build upon once the patent expires. This is the bargain: a short-term monopoly for a long-term public benefit. The industry rightly defends this system, arguing that without the promise of strong patent protection, the flow of investment into life-saving R&D would slow to a trickle .

Extending the Monopoly: The Art of Evergreening and Patent Thickets

The fundamental tension of the patent system arises when the strategies to protect this monopoly shift from rewarding initial, groundbreaking innovation to simply prolonging the period of exclusivity for as long as possible. Over the past few decades, brand-name pharmaceutical companies have developed sophisticated and highly effective legal strategies to do just that, often pushing a drug’s monopoly protection far beyond the original 20-year term. The two most prominent of these strategies are known as “evergreening” and the creation of “patent thickets.”

Evergreening is the practice of filing for new, secondary patents on minor modifications of an existing drug as the original, core patent nears expiration . These are not patents on the active molecule itself, but on peripheral aspects of the product. This can include new formulations (e.g., changing from a twice-daily pill to an extended-release, once-daily version), new methods of delivery (e.g., a new injector pen design), new dosages, or even new methods of use (e.g., getting the drug approved to treat a different condition) . While the industry argues these represent legitimate, incremental innovations that improve patient care, critics contend that they are often trivial changes designed primarily to add another layer of legal protection and delay the entry of generic competitors . As Dr. Joel Lexchin, a health policy professor, notes, “Typically, when you evergreen something, you are not looking at any significant therapeutic advantage. You are looking at a company’s economic advantage” .

A patent thicket is the result of this process scaled up to an industrial level. It refers to the creation of a dense, overlapping, and complex web of dozens or even hundreds of patents around a single drug product . This thicket acts as a formidable barrier to any generic or biosimilar company wanting to enter the market. To launch their product, the competitor must not only challenge the original core patent but also navigate this legal minefield, potentially facing dozens of infringement lawsuits on secondary patents. The sheer cost and risk of this litigation can be enough to deter or significantly delay competition, even if many of the secondary patents are weak and might not hold up in court .

The scale of this practice is immense. A report by the Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge (I-MAK) that evaluated twelve of the bestselling drugs in the U.S. found that manufacturers had filed, on average, 125 patent applications and had been granted 71 patents for each drug. This amounted to an attempt to secure 38 years of patent protection—nearly double the 20-year monopoly the system was intended to provide .

These strategies represent a fundamental shift in the focus of pharmaceutical R&D. Resources that could be directed toward discovering truly novel treatments for unmet medical needs are instead channeled into “defensive” or “lifecycle management” innovation. The primary goal is no longer just a scientific breakthrough but the creation of new intellectual property that can serve as a legal and financial bulwark against competition. The patent system, designed to spur innovation, is thus being strategically used to protect existing revenue streams, creating a crowded and complex legal landscape that can stifle the very competition it was meant to eventually enable.

Case Study: The Humira Fortress

There is no better illustration of a patent thicket in action than the strategy employed by AbbVie for its blockbuster drug, Humira (adalimumab). For years, Humira was the best-selling drug in the world, generating over $20 billion in annual sales at its peak . Its commercial success was underpinned by one of the most formidable and aggressive patent strategies the industry has ever seen.

Humira was first approved by the FDA in 2002. Its core patent on the active molecule was set to expire in 2016. However, AbbVie did not stop there. The company proceeded to build a legal fortress around its prized asset. In the United States, AbbVie filed a total of 247 patent applications related to Humira. A remarkable 89% of these applications were filed after the drug was already on the market, with nearly half of them filed after 2014—more than a decade into the drug’s commercial life.

The result was a patent thicket of staggering density, with AbbVie ultimately holding over 130 granted patents on Humira in the U.S. . These secondary patents covered everything from specific manufacturing processes to new formulations and methods of treating the various inflammatory conditions for which Humira is approved. This legal fortress achieved its goal with ruthless efficiency. While biosimilar versions of Humira entered the European market in 2018, leading to immediate and steep price reductions, AbbVie used its patent thicket to hold off any U.S. competition until 2023, an additional five years of monopoly sales . The cost of this delay to the American healthcare system has been estimated at over $14.4 billion .

Protected from competition, AbbVie was free to raise Humira’s price with impunity. Between 2012 and 2018 alone, the price of the drug nearly doubled, from approximately $19,000 per year to $38,000 per year . This case study is a masterclass in modern pharmaceutical lifecycle management. It highlights that for generic and biosimilar companies, bringing a lower-cost alternative to market is not merely a scientific and regulatory challenge; it is a legal and financial war of attrition against a deeply entrenched incumbent.

Successfully navigating this landscape requires an extraordinary level of sophisticated patent intelligence. This is precisely where a service like DrugPatentWatch becomes an indispensable strategic tool. For a company planning to launch a generic or biosimilar, it is not enough to know when the primary patent expires. They must have a granular understanding of the entire patent estate—every secondary patent, its expiration date, its legal status, and its litigation history. DrugPatentWatch provides this critical, actionable intelligence, allowing companies to analyze the vulnerabilities in a patent thicket, assess the litigation risk, and strategically plan a market entry that can withstand the inevitable legal onslaught . In the high-stakes world of pharmaceutical patents, data is ammunition, and platforms like this are the key to leveling the playing field.

The Middlemen Maze: Unpacking the Role of PBMs and the Rebate System

While patent monopolies create the opportunity for high drug prices, they don’t fully explain the complex and often counterintuitive pricing dynamics that exist in the U.S. market. To understand that, we must venture into the opaque world of the pharmaceutical supply chain and examine the powerful intermediaries who stand between the drug manufacturer and the patient: Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). Originally created to control costs, the business model of these middlemen has evolved in ways that can perversely incentivize the very high prices they are supposed to combat.

The Theory vs. The Reality of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

In theory, the role of a PBM is straightforward and beneficial. PBMs are third-party administrators hired by health insurance plans, large employers, and government programs to manage their prescription drug benefits . Their primary value proposition is to leverage the collective purchasing power of the millions of patients they represent to negotiate significant discounts from drug manufacturers. By creating formularies—lists of covered drugs—and favoring certain drugs over others, they can force manufacturers to compete on price to gain access to their network of patients . In return for these services, the health plan pays the PBM an administrative fee.

For decades, this model was credited with helping to manage drug spending. However, as drug prices have continued to soar, the PBM industry has come under intense scrutiny. Critics now argue that the business practices of the largest PBMs, which operate with very little transparency, are riddled with conflicts of interest that can inflate costs for everyone. As one analysis notes, while PBMs were created to contain spending, many now argue they may be “directly responsible for the increased health cost in the United States” . A scathing investigation by The New York Times came to a similar conclusion, stating, “The job of the P.B.M.s is to reduce drug costs. Instead, they frequently do the opposite. They steer patients…source billions of dollars in hidden fees” .

The Perverse Incentive of the Rebate System

At the core of the controversy surrounding PBMs is the rebate system. A rebate is a discount that a drug manufacturer pays to a PBM after a drug is dispensed. In exchange for this rebate, the PBM agrees to place the manufacturer’s drug in a favorable position on its formulary, such as a “preferred” tier with lower patient cost-sharing, thus encouraging its use . The scale of these rebates is massive; in 2023 alone, total manufacturer rebates paid to PBMs for brand-name drugs reached an estimated $334 billion .

The problem lies in how these rebates are structured. They are typically calculated as a percentage of a drug’s list price (also known as the Wholesale Acquisition Cost, or WAC). This creates a perverse incentive. A PBM can often generate more revenue for itself by favoring a drug with a very high list price and a large percentage rebate over a competing drug that has a lower list price and a smaller rebate, even if the second drug has a lower net cost (the price after the rebate is applied) for the health plan and patient.

Let’s illustrate this with a simple, hypothetical example. Imagine two competing drugs for the same condition:

- Drug A has a list price of $1,000 per month and the manufacturer offers a 40% rebate ($400).

- Drug B has a list price of $600 per month and the manufacturer offers a 10% rebate ($60).

The net price of Drug A is $600, while the net price of Drug B is $540. Clearly, Drug B is the more cost-effective option for the health plan. However, the PBM’s financial incentive may point in the opposite direction. If the PBM retains even a small portion of the rebate as its fee, it stands to make far more from the $400 rebate on Drug A than the $60 rebate on Drug B. This gives the PBM a powerful reason to place the more expensive Drug A on its preferred formulary, steering patients and doctors toward it.

This dynamic creates what is often called the “rebate wall.” It actively discourages manufacturers from launching new drugs with lower list prices because PBMs may refuse to cover them, preferring the higher-priced incumbents that generate larger rebates. The result is an “invisible price” for drugs, where the publicly stated list price is artificially inflated to accommodate this complex system of back-end payments.

This system is particularly harmful to patients. A patient’s cost-sharing, especially if they have a co-insurance plan, is often calculated based on the drug’s high list price, not the lower, post-rebate net price that the insurer and PBM ultimately pay. In our example, a patient with 20% co-insurance would pay $200 for the “preferred” Drug A ($1,000 * 20%), but would have only paid $120 for the non-preferred Drug B ($600 * 20%). The patient is penalized with higher out-of-pocket costs, while the intermediaries in the system profit from the high list price and the large rebate it generates. This is a crucial point: rebates do not lower what a patient pays at the pharmacy counter .

Spread Pricing and Other Revenue Streams

The rebate system is not the only controversial PBM business practice. Another is known as “spread pricing,” which primarily affects generic drugs. In a spread pricing model, a PBM charges a health plan a certain amount for a generic drug but then reimburses the pharmacy a lower amount for dispensing it. The PBM simply pockets the difference, or the “spread” . This practice is particularly opaque, as neither the health plan nor the pharmacy knows what the other is being paid. The financial impact can be substantial; one analysis found that the three largest PBMs generated an estimated $1.4 billion in income from spread pricing on just 51 generic specialty drugs over a five-year period .

Adding another layer of complexity is the rampant vertical integration in the industry. The three largest PBMs—CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum Rx—which control nearly 80% of the market, are now owned by or integrated with major health insurance companies (Aetna, Cigna, and UnitedHealth Group, respectively) and, in some cases, their own massive pharmacy chains (like CVS Pharmacy) . This creates a clear conflict of interest, as the PBM has an incentive to design formularies and networks that steer patients toward its own specialty or mail-order pharmacies, potentially at the expense of independent pharmacies and patient choice. These integrated systems, shrouded in contractual confidentiality, make it nearly impossible for employers and patients to understand the true cost of their medicines and where the money is flowing.

Shaping Demand: The Power of Advertising and Perception

The high price of brand-name drugs in the United States is not sustained by supply-side factors alone. A crucial part of the equation is the powerful machinery used to generate and shape demand. Unlike any other developed nation except New Zealand, the U.S. permits direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) for prescription drugs. This, combined with a lingering, often subconscious, skepticism about the quality of generic alternatives, creates a potent cultural and psychological environment that steers patients toward the most expensive treatment options, often irrespective of clinical necessity or value.

“Ask Your Doctor”: The Influence of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising (DTCA)

Turn on an American television during prime time, and you will be inundated with advertisements for prescription drugs. These ads, with their scenes of happy, active people and rapidly spoken lists of potential side effects, are a unique feature of the American media landscape. They are also an incredibly powerful business tool. Pharmaceutical companies invest billions of dollars in DTCA, with annual spending reaching $6.58 billion by 2020 . This investment yields a handsome return.

The primary goal of DTCA is to create patient-driven demand. The ubiquitous tagline, “Ask your doctor,” is a direct call to action, and patients respond. Research from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that nearly a third of American adults (30%) have talked to their doctor about a specific drug they saw advertised. The influence doesn’t stop there. Of those who initiated that conversation, a remarkable 44% reported that their doctor provided them with a prescription for the very drug they asked for. The economic impact is profound. One landmark study concluded that DTCA accounted for 12% of the total growth in prescription drug spending in the year 2000, calculating that every additional dollar spent on advertising generated $4.20 in additional drug sales.

Proponents of DTCA argue that it serves a valuable public health function by educating consumers about treatable conditions and empowering them to have more informed conversations with their physicians . However, the evidence suggests a more complicated reality. Since only expensive, on-patent brand-name drugs are advertised, DTCA inherently skews patient demand away from older, often equally effective and far cheaper generic alternatives.

More troublingly, this advertising may be driving the use of drugs with questionable clinical benefits. A recent study published in JAMA uncovered a startling trend: pharmaceutical companies actually spent more money on DTCA for drugs that had demonstrated lower added clinical benefit compared to existing treatments . Furthermore, this increased spending directly translated into higher sales for these medically inferior drugs . This finding suggests a deliberate strategy. If a drug’s clinical data is not compelling enough to convince evidence-based physicians to prescribe it, manufacturers can bypass the physician’s judgment by creating a groundswell of demand directly from patients. The physician is then put in the difficult position of either refusing a patient’s request, potentially damaging the doctor-patient relationship, or acquiescing and prescribing a drug they might not otherwise have chosen. In this light, DTCA is not simply an informational tool; it is a strategic lever to drive utilization of high-margin products, sometimes at the expense of more cost-effective or clinically superior care.

The Ghost of Doubt: Generic Skepticism

While DTCA actively pulls patients toward branded products, a more subtle psychological factor can also push them away from generics: a lingering, often unfounded, skepticism about their quality and efficacy. Despite decades of evidence and regulatory assurance, some patients and even healthcare providers harbor doubts.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has exceptionally strict standards for generic drugs. To be approved, a generic manufacturer must prove that their product is “bioequivalent” to the brand-name original. This means it must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength and dosage form, and be absorbed into the bloodstream at a comparable rate . In essence, it is a molecular and therapeutic replica. Numerous large-scale studies have confirmed the clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs for treating a wide range of conditions, from cardiovascular disease to epilepsy .

Yet, the perception gap persists. This can be fueled by subtle differences in the appearance of the pills (trademark laws require generics to look different) or by the simple psychological association of lower price with lower quality . This skepticism can have a measurable impact on patient choice. One fascinating study examined the behavior of patients who had just received “bad medical news,” such as a borderline high blood sugar test result. The researchers found that these anxious patients showed a significantly increased propensity to choose a more expensive brand-name drug over its generic equivalent in the days following their diagnosis . This suggests a “flight to quality,” where in moments of fear and uncertainty, patients are willing to pay a premium for the perceived safety and reliability of the familiar brand, even when no therapeutic difference exists.

This ghost of doubt comes at a tremendous cost. A study published in JAMA Internal Medicine calculated that between 2010 and 2012, patients and the healthcare system spent an estimated $73 billion on branded drugs when a chemically different but therapeutically equivalent generic was available within the same drug class . The excess out-of-pocket spending for patients alone was $24.6 billion . Another analysis estimated that the U.S. system could save an additional $36 billion a year if patients simply chose the direct generic equivalent every time one was available . While generic utilization is already high, these figures show that overcoming the last vestiges of brand preference represents one of the largest remaining opportunities for cost savings in the entire healthcare system.

A Tale of Two Systems: Federal Pricing in Medicare vs. Medicaid

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that high drug prices in the United States are a product of policy choices, rather than an immutable law of economics, can be found by examining the federal government’s own programs. Within the U.S. healthcare system, two massive public payers, Medicare and Medicaid, purchase drugs for tens of millions of Americans. Yet, they do so under vastly different rules, resulting in dramatically different prices for the exact same medications. This internal comparison provides a powerful natural experiment, revealing how the structure of a drug benefit program can either amplify or constrain manufacturer pricing power.

Medicare Part D: A Market-Based Approach with Limited Leverage

When the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit was created in 2003, it was designed around a market-based philosophy. Instead of having the federal government, the single largest purchaser of drugs in the country, negotiate prices directly with manufacturers, the law explicitly prohibited it . Instead, the program relies on a network of private insurance companies to offer prescription drug plans (PDPs). These private plans, in turn, hire PBMs to negotiate with drug companies on their behalf, creating formularies and setting cost-sharing tiers, much like in the commercial market .

The theory was that competition among these private plans would drive down costs for both beneficiaries and the government. In practice, however, this fragmented approach left the program with limited leverage against the monopoly power of brand-name drug manufacturers. While PBMs do negotiate substantial rebates, the system inherited all the flaws of the commercial market, including the perverse incentives of the rebate system that favor high list prices.

The results are reflected in the prices Medicare pays. A 2017 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) provides a stark picture. For a sample of 176 top-selling brand-name drugs, the average net price per prescription in Medicare Part D was $343 . For specialty drugs, which treat complex conditions like cancer and rheumatoid arthritis, the average net price was a breathtaking $4,293 per prescription . These high prices translate directly into high costs for both taxpayers, who fund the majority of the program, and for beneficiaries themselves. It is important to remember that until recent reforms, patient out-of-pocket costs were based on the high pre-rebate list price, meaning seniors could face thousands of dollars in costs for a single medication, even with insurance .

Medicaid: The Power of Statutory Rebates

The Medicaid program, which provides health coverage for low-income Americans, operates under a completely different set of rules established by the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP). This program is not based on voluntary negotiations between private plans and manufacturers. Instead, it leverages the power of federal law to command steep discounts .

As a condition of having their drugs covered by Medicaid—a market too large for any manufacturer to ignore—companies are required to provide a statutory rebate to the government. This rebate is defined by a formula set in law. For most brand-name drugs, the basic rebate is the greater of two options: 23.1% of the drug’s Average Manufacturer Price (AMP), or the difference between the AMP and the “best price” the manufacturer offers to any private commercial purchaser in the country . This “best price” provision ensures that Medicaid, as the payer of last resort, gets at least as good a deal as the most favored private customer.

Furthermore, the MDRP includes a powerful inflation penalty. If a manufacturer raises the price of a drug faster than the rate of general inflation, they must pay an additional rebate to Medicaid equal to the excess amount . This mechanism effectively claws back inflationary price hikes and strongly disincentivizes the kind of aggressive annual price increases common in the commercial and Medicare markets.

The impact of this statutory rebate system is nothing short of dramatic. It results in the lowest net drug prices of any major payer in the United States. The same CBO study that found an average brand-name drug price of $343 in Medicare Part D found that the average net price for the same basket of drugs in Medicaid was just $118 . This represents a 65% discount compared to Medicare. For specialty drugs, the difference was just as stark: $1,889 in Medicaid versus $4,293 in Medicare . Overall, the CBO concluded that Medicaid’s average net price for brand-name drugs was only 35% of Medicare Part D’s average price . This is a direct result of the power of the rebate formula; on average, total rebates in Medicaid equaled an incredible 77% of a brand-name drug’s retail price, compared to just 35% in Medicare Part D .

A Stark Comparison of Federal Drug Prices

The most effective way to visualize this policy-driven price disparity is to compare the programs side-by-side. The following table, using data from the CBO’s 2017 analysis, illustrates the profound difference in net prices paid by America’s largest public health programs for the same categories of top-selling brand-name drugs .

| Drug Category | Medicare Part D (Average Net Price) | Medicaid (Average Net Price) | Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) (Average Net Price) | Medicaid Price as % of Medicare Price |

| All Top-Selling Drugs | $343 | $118 | $190 | 34.4% |

| Specialty Drugs | $4,293 | $1,889 | $2,018 | 44.0% |

| Non-Specialty Drugs | $246 | $64 | $143 | 26.0% |

Source: Analysis of data from the Congressional Budget Office reports on brand-name drug prices among selected federal programs.

This table serves as a powerful testament to the impact of purchasing power and policy design. It shows that within the same country, for the exact same products regulated by the same FDA, vastly different prices are not just possible, but are a daily reality. The fact that Medicaid consistently pays a fraction of what Medicare Part D pays demonstrates that high drug prices are not an unavoidable consequence of innovation. Rather, they are a direct result of a fragmented, market-based system that, by design, has lacked the leverage to effectively counter manufacturer pricing power. This internal comparison laid the political and economic groundwork for the eventual reforms in the Inflation Reduction Act, which sought to bring a measure of Medicaid’s purchasing power to the Medicare program.

The Ripple Effect: Consequences for Patients, Payers, and the Economy

The exorbitant cost of brand-name drugs in the United States is not an abstract economic issue confined to corporate balance sheets and government budgets. It creates a series of cascading and destructive ripple effects that touch every corner of the healthcare system and the broader economy. For patients, the consequences can be devastating, forcing them to make impossible choices between their health and their financial stability. For employers and insurers, it fuels an unsustainable rise in healthcare costs that gets passed on to everyone in the form of higher premiums. And for the nation as a whole, it represents a massive and inefficient allocation of resources that strains public finances and hinders economic productivity.

The Human Cost: Cost-Related Non-Adherence and Health Outcomes

The most immediate and tragic consequence of high drug prices is their impact on patients. When people cannot afford the medications their doctors prescribe, they do not simply absorb the cost; they alter their behavior in ways that can be dangerous and even fatal. This phenomenon is known as cost-related non-adherence (CRN).

According to polling from the Kaiser Family Foundation, nearly one in four Americans currently taking prescription drugs report that it is difficult to afford them . This financial strain forces patients to engage in risky cost-saving measures. They may delay filling a prescription, skip doses to make a 30-day supply last for 60, or cut pills in half against medical advice . For many, the choice is even starker, forcing them to choose between paying for their medication and paying for other basic necessities like food or rent .

The clinical consequences of this behavior are severe. Medication adherence is a primary determinant of treatment success, especially for chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and asthma . When patients fail to take their medications as prescribed, their conditions can worsen, leading to a cascade of negative health outcomes: reduced effectiveness of treatment, exacerbation of symptoms, preventable complications, and an increased risk of hospitalization .

The ultimate cost of non-adherence is measured in lives. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that non-adherence contributes to at least 100,000 preventable deaths in the U.S. each year . A specific CDC study focusing on CRN found that among patients with chronic conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease, those who reported not taking their medication due to cost had a 15% to 22% higher all-cause mortality rate than those who were adherent . The message is brutally simple: when drugs are unaffordable, people get sicker, and some of them die.

Case Study: The Insulin Crisis

No single drug illustrates the human cost of the American pricing system more powerfully than insulin. Discovered over a century ago, its patent was famously sold by its creators to the University of Toronto for a symbolic $1, with the explicit wish that it would always be affordable for those who needed it to survive. For decades, that wish was honored. But over the past 20 years, that humanitarian legacy has been systematically dismantled, turning a life-saving commodity into a luxury good.

The price of insulin in the U.S. has risen by more than 300% in the last two decades . The same vial of insulin that cost $21 in 1996 now costs upwards of $250, despite the fact that its production cost is estimated to be as low as $2 to $4 per vial . This price explosion is not the result of any significant innovation in the molecule itself; it is a product of a market dominated by just three manufacturers—Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk—that have raised their prices in near-perfect lockstep, a practice known as “shadow pricing” . This market structure, combined with the perverse incentives of the PBM rebate system that favors high list prices, has created a full-blown public health crisis .

The consequences for the millions of Americans living with diabetes have been catastrophic. A 2022 study found that more than one in seven American insulin users—1.3 million people—had rationed their supply in the past year due to cost . Stories of young adults dying from diabetic ketoacidosis after aging out of their parents’ insurance and being unable to afford their insulin have become tragically common. For many, the cost is simply unsustainable. One study found that 14% of insulin users in the U.S. experienced “catastrophic” spending, meaning they spent at least 40% of their post-subsistence income on insulin alone . The insulin crisis is a microcosm of the entire system’s failures, where market dynamics and intermediary profits have been prioritized over access to a century-old, life-sustaining medicine.

The Economic Burden on Payers and the System

Beyond the direct harm to patients, the overspend on branded drugs imposes a massive economic burden on the entire U.S. healthcare system and the broader economy. Total inflation-adjusted spending on prescription drugs reached $603 billion in 2021, accounting for a substantial 18% of all national healthcare expenditures . This relentless growth in spending puts immense pressure on every payer in the system.

For the nearly 160 million Americans who receive health insurance through their employer, high drug costs are a primary driver of rising premiums and deductibles . As the cost of the drug benefit rises, employers are forced to either pass those costs on to their employees, reduce other benefits, or suppress wages. This makes American businesses less competitive and erodes the financial security of working families.

For the federal government, prescription drug spending is a major driver of the national debt. Medicare and Medicaid are two of the largest line items in the federal budget, and the high price of drugs is a significant contributor to their long-term fiscal unsustainability . The CBO has repeatedly highlighted rising drug costs as a key challenge for policymakers seeking to control federal spending .

Finally, the economic damage extends beyond direct healthcare costs. Medication non-adherence leads to lost productivity from increased sick days and disability, costing employers billions . The financial strain on families can reduce consumer spending in other sectors of the economy. The annual cost of morbidity and mortality associated with poor medication adherence has been estimated to be as high as $528.4 billion . This is not just a healthcare problem; it is an economic problem that acts as a persistent drag on American prosperity.

Charting a New Course: Policy Reforms and Strategic Opportunities

For decades, the trajectory of U.S. brand-name drug prices seemed to move in only one direction: up. The complex, interwoven system of patent extensions, opaque intermediaries, and fragmented purchasing power appeared intractable. However, the last few years have witnessed a seismic shift in the policy landscape. Spurred by public outrage and mounting economic pressure, federal and state governments have begun to take unprecedented steps to challenge the status quo. This new era of intervention, headlined by the Inflation Reduction Act, is fundamentally altering the rules of the game, creating both significant challenges and new strategic opportunities for every player in the pharmaceutical ecosystem.

Federal Intervention: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

Signed into law in August 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) represents the most significant reform of U.S. prescription drug pricing policy in a generation . Its provisions directly target several of the core drivers of high costs within the Medicare program, establishing new mechanisms of federal power that were once considered politically impossible.

The centerpiece of the IRA is the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. For the first time in its history, the law empowers the federal government, through the Secretary of Health and Human Services, to directly negotiate the prices of certain high-cost drugs covered under Medicare Parts B and D . The program targets drugs that have been on the market for several years without generic or biosimilar competition. The first 10 drugs were selected for negotiation in 2023, with their new, lower prices set to take effect in 2026. The number of negotiated drugs will expand each year, creating a growing portfolio of medicines with federally set maximum prices .

A second key provision establishes inflation rebates. The IRA requires drug manufacturers to pay a rebate back to Medicare if they increase the price of their drugs faster than the rate of general inflation . This is a direct assault on the long-standing practice of aggressive, year-over-year price hikes on existing products. By clawing back price increases that exceed inflation, the policy aims to stabilize prices for older drugs and remove the incentive for such behavior.

Finally, the IRA provides direct financial relief to patients through a redesign of the Part D benefit. Most notably, it establishes an annual cap on out-of-pocket drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries, which is set at $2,000 beginning in 2025 . This provision will be life-changing for seniors with conditions like cancer or multiple sclerosis who previously faced unlimited out-of-pocket liability that could run into the tens of thousands of dollars per year.

The IRA represents a profound paradigm shift. It moves a significant portion of the U.S. drug pricing model, at least within Medicare, away from the traditional, distorted market-based dynamics and toward a more regulated, value-based framework akin to what exists in other developed nations. While its initial scope is limited to a specific subset of drugs within Medicare, it establishes a permanent federal mechanism for price constraint that will have far-reaching strategic implications.

The law effectively creates a “countdown clock” for the industry’s most successful products. Single-source small-molecule drugs become eligible for negotiation 9 years after their FDA approval, and biologics become eligible after 13 years . This introduces a predictable future event where a drug’s price will be significantly reduced by government action. This fundamentally alters the long-term revenue projections for any new blockbuster drug and changes the calculus for R&D and lifecycle management. The strategic ground is shifting from a purely legal defense of a monopoly (extending patents) to a hybrid legal and economic defense, where companies must be prepared to justify their prices based on clinical value to government negotiators.

State-Level Laboratories of Democracy

While the IRA is a landmark federal achievement, it was preceded by years of policy innovation at the state level. Frustrated by federal inaction, states have increasingly acted as “laboratories of democracy,” experimenting with a wide range of policies to control drug costs for their citizens.

One major area of focus has been the regulation of Pharmacy Benefit Managers. States like Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Maine, and New York have passed laws aimed at increasing PBM transparency, banning controversial practices like spread pricing, and imposing a fiduciary duty on PBMs to act in the best interest of their health plan clients . These laws are a direct attempt to rein in the power of middlemen and ensure that negotiated savings are passed on to payers and patients.

An even more ambitious approach has been the creation of Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs). A growing number of states, including Maryland, Colorado, and Oregon, have established these independent bodies, which are empowered to review the prices of high-cost drugs and, in some cases, set upper payment limits on what can be paid for them within the state . These boards function much like public utility commissions, treating certain high-cost medicines as essential services whose prices must be regulated to ensure public affordability. While these state-level actions face legal challenges from the pharmaceutical industry, they represent a powerful grassroots movement to assert control over drug prices from the bottom up.

The Path Forward: Leveraging Intelligence for Competitive Advantage

The pharmaceutical landscape is in the midst of a historic transformation. The old rules of unchecked pricing power and indefinite monopoly extensions are being rewritten. In this more complex and regulated environment, success will no longer be determined by marketing muscle or legal might alone. It will be defined by superior market intelligence, strategic foresight, and the ability to adapt to a rapidly evolving playing field.

For Generic and Biosimilar Firms: The opportunities have never been greater, but the challenges remain immense. The key to success lies in identifying the right drug targets and the optimal time for market entry. This requires a forensic understanding of the complex patent estates surrounding blockbuster drugs. This is where business intelligence platforms like DrugPatentWatch are no longer just helpful; they are essential. By providing granular, real-time data on patent expiry dates, new patent filings, ongoing litigation, and regulatory exclusivities, these tools transform a chaotic legal landscape into a strategic map of market opportunities . They allow companies to analyze the weaknesses in a patent thicket, forecast the true loss of exclusivity, and make multi-million-dollar investment decisions with a greater degree of confidence.

For Brand-Name Firms: The strategic imperative is shifting dramatically. Defending a product’s revenue stream now requires more than just a strong patent portfolio; it demands a compelling and evidence-based value proposition to justify prices to payers, providers, and, increasingly, government negotiators. Lifecycle management strategies must now account for the predictable timeline of the IRA’s negotiation program. The focus may need to shift away from late-stage, minor product tweaks toward generating robust real-world evidence that demonstrates a drug’s clinical and economic value from the moment of launch.

For Payers and Employers: The new policy environment provides greater leverage, but it must be actively used. The focus must be on demanding radical transparency and accountability from PBM partners. This means moving away from opaque rebate-driven contracts and toward models based on a drug’s true net cost, such as pass-through pricing or flat-fee administrative models . It also means designing formularies that aggressively promote the use of lower-cost generics and newly available biosimilars to capture the full potential of market competition. The era of passively accepting high drug prices is over; the future belongs to those who can harness data and smart policy to drive value.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The phenomenon of Americans overspending on brand-name drugs is not an accident but a design. It is the carefully constructed result of a unique healthcare ecosystem where a government-granted monopoly system has been strategically amplified by an opaque supply chain and a fragmented payer landscape. For decades, this system allowed brand-name drug manufacturers to set prices at levels unheard of in the rest of the developed world, insulated from both meaningful competition and negotiation. The consequences have been severe, imposing a heavy burden on the health of patients and the health of the national economy.

However, the ground is now shifting. A wave of federal and state policy reforms, most notably the Inflation Reduction Act, is beginning to dismantle the pillars of this old model. The introduction of Medicare price negotiation, inflation penalties, and greater scrutiny of intermediaries marks a fundamental change in the rules of engagement. The future of the pharmaceutical industry will be defined not by the ability to unilaterally dictate prices, but by the ability to demonstrate value, navigate a more complex regulatory environment, and compete in a market where cost-effectiveness is no longer a secondary consideration. For every stakeholder—from the largest pharmaceutical company to the smallest employer—adapting to this new reality is the most critical strategic challenge of our time.

Key Takeaways

- The 80/80 Paradox Defines the Market: While generics account for the vast majority of prescriptions filled in the U.S. (80-90%), brand-name drugs consume the vast majority of the spending (80%), highlighting a market of extreme price concentration.

- The U.S. is a Global Price Outlier: Americans pay prices for brand-name drugs that are, on average, more than three times higher than in other developed countries. This is a direct result of a fragmented payer system that has historically lacked the centralized negotiating power seen in nations with national health programs.

- Patents are a Double-Edged Sword: The patent system, designed to spur innovation, is systematically used to delay competition. Strategies like “patent thickets” and “evergreening” extend drug monopolies far beyond their intended term, costing the healthcare system billions.

- Intermediaries Can Inflate Costs: The PBM business model, particularly the rebate system, creates perverse incentives that can favor high-list-price drugs over more cost-effective alternatives. Opaque practices like “spread pricing” further add to system-wide costs.

- High Prices Have Severe Human and Economic Consequences: The unaffordability of brand-name drugs leads directly to cost-related non-adherence, which results in poor health outcomes, preventable deaths, and hundreds of billions of dollars in avoidable healthcare costs and lost productivity.

- The Policy Landscape is Fundamentally Changing: The Inflation Reduction Act has introduced Medicare price negotiation and inflation caps, creating a new federal mechanism to constrain prices. This marks a paradigm shift that will force long-term changes in industry business models.

- Intelligence is the New Competitive Advantage: In this evolving market, success for all stakeholders—brand firms, generic manufacturers, and payers—will depend on leveraging sophisticated market and patent intelligence to navigate new regulations, anticipate market shifts, and make informed strategic decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Don’t high U.S. drug prices fund global research and development (R&D)? If we adopt European-style prices, won’t innovation disappear?

This is the pharmaceutical industry’s most prominent argument, and it contains a kernel of truth but is often overstated. The U.S. market, due to its high prices, does contribute a disproportionate share of global pharmaceutical profits, which are the source of R&D funding. However, the relationship between price and innovation is not linear. A significant portion of industry spending goes toward marketing, administration, and “lifecycle management” R&D aimed at creating patent thickets rather than discovering novel medicines. Furthermore, analyses by bodies like the Congressional Budget Office project that policies like the IRA’s price negotiation will have only a modest impact on the number of new drugs coming to market over the next 30 years—a small reduction, but far from the collapse of innovation that industry warnings suggest. The policy debate is not about eliminating the incentive for innovation but about rebalancing it to ensure that the rewards are not so excessive that they render the innovations unaffordable for the public that ultimately funds them.

2. If generics account for 90% of all prescriptions, why is overall drug spending still rising so fast?

This is the central paradox of the U.S. market. The answer lies in the extreme price disparity between the two segments. While the average price of a generic prescription has been stable or falling, the average price of a brand-name prescription has been skyrocketing. A single new specialty drug for a condition like cancer or hepatitis C can have an annual cost of tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient. The spending on just a few of these high-cost blockbusters can easily overwhelm the savings generated by millions of generic prescriptions that cost only a few dollars each. Therefore, even as the volume of prescriptions shifts heavily toward generics, the total spending is driven by the price inflation and high launch prices of the 10% of drugs that remain on-brand.

3. How can a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM), whose stated job is to lower drug costs, actually end up increasing them for patients and payers?

This counterintuitive outcome stems from the PBM’s business model and its reliance on opaque rebates. Because rebates are calculated as a percentage of a drug’s high list price, a PBM’s revenue can be maximized by placing a drug with a high list price and a large rebate on its formulary, even if a competing drug has a lower net cost. This “rebate wall” incentivizes high list prices across the market. For patients, this is particularly harmful because their out-of-pocket co-insurance is often based on the inflated list price, not the lower net price the PBM and insurer pay. So, a patient can end up paying more for a “preferred” drug precisely because the rebate that benefits the PBM is so large.

4. What is the most significant long-term impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on the pharmaceutical industry’s business model?

The most significant long-term impact is the introduction of price and revenue predictability—or, from the industry’s perspective, uncertainty. Before the IRA, a successful blockbuster drug could expect a long period of unchecked price increases followed by a steep patent cliff. The IRA changes this by creating a “countdown clock.” Now, a highly successful drug is almost guaranteed to face government price negotiation 9 or 13 years after its launch. This forces companies to fundamentally rethink their long-term financial models. It may reduce the value of late-stage “evergreening” patent strategies and place a much higher premium on launching with a strong clinical value proposition to justify a high price before the negotiation window opens. It shifts the strategic focus from indefinite price maximization to optimizing revenue within a more defined and regulated lifecycle.

5. Beyond patents, what other types of “exclusivity” protect brand-name drugs from competition?

While patents are the primary form of protection, the FDA also grants several types of regulatory exclusivity that can run concurrently with or extend beyond patent life. These are granted as incentives for conducting certain types of research. Key examples include:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A five-year period of market exclusivity for drugs containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): A seven-year period of exclusivity for drugs developed to treat rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.).

- Pediatric Exclusivity: An additional six months of exclusivity added to existing patents and exclusivities as a reward for conducting studies in children.

These exclusivities function like patents by blocking the FDA from approving a competing generic application for a set period, providing another important layer of monopoly protection for brand-name manufacturers.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Comparing Prescription Drugs. ASPE.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (n.d.). Prescription Drug Spending. GAO.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Generic Competition and Drug Prices. FDA.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2022). Prescription Drugs: Spending, Use, and Prices. CBO.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Trends in Prescription Drug Spending, 2016-2021. ASPE.

- PhRMA. (n.d.). GAO Report Finds Drug Prices Increasing at Lower Rate than Medical Inflation.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2021). Prescription Drugs: U.S. Prices for Selected Brand Drugs Were Higher on Average than Prices in Australia, Canada, and France. GAO-21-282.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (n.d.). Prescription Drug Spending: States Have Enacted a Variety of Laws to Regulate Pharmacy Benefit Managers. GAO-24-106898.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2009). Federal Employees Health Benefits Program: Approaches to Control Prescription Drug Spending. GAO-09-819T.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2007). Prescription Drugs: Oversight of Drug Pricing in Federal Programs. GAO-07-481T.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (n.d.). Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Initial Implementation of Medicare Drug Pricing Provisions. GAO-25-106996.

- Congressional Budget Office. (n.d.). Prescription Drugs. CBO.

- Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. (2021). New CBO Study Compares Net Prices for Brand-Name Drugs Among Federal Programs, Finds Medicaid Gets Largest Discounts.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2021). A Comparison of Brand-Name Drug Prices Among Selected Federal Programs.

- Pharmaceutical Care Management Association. (2022). CBO Report on Prescription Drug Trends.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2024). Recent Trends in Medicaid Outpatient Prescription Drugs and Spending.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2024). Alternative Approaches to Reducing Prescription Drug Prices.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Trends in Prescription Drug Spending, 2016-2021.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2024). Prescription Drug Spending, Pricing Trends, and Premiums in Private Health Insurance Plans.

- NFP. (2024). HHS Issues RxDC Report on Prescription Drug Spending.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Trends in Prescription Drug Spending, 2016-2021. ASPE.

- SSG. (2024). Key Takeaways from the HHS Prescription Drug Cost Report.

- American Economic Association. (2022). HHS Releases Two New Reports on Prescription Drug Prices and Spending.

- Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. (n.d.). Generic vs. brand name and the cost of bad news.

- RAND Corporation. (2021). Prescription Drug Prices in the U.S. Are 2.56 Times Higher Than in Other Countries.

- UCSF Magazine. (n.d.). Generic Drugs: Are They on Par with Pricier Brands?.

- University Hospitals. (2022). Generic vs. Brand-Name Drugs: Is There a Difference?.

- Terman, S. W., et al. (2023). Trends in Antiseizure Medication Use and Costs Among US Medicare Beneficiaries From 2008 to 2018. Neurology, 100(23), e2349-e2359.

- Gilchrist, A. (2016). Generic Therapeutic Substitution Could Curb Soaring Drug Costs. Pharmacy Times.

- Hernandez, R. (2018). Copay exceeds drug cost in 23% of claims: JAMA research. BioPharma Dive.

- Shinkman, R. (2016). Drug prices: Generics may keep costs stable but there aren’t enough of them. Fierce Healthcare.

- Hernandez, I., et al. (2019). Trends in List Prices, Net Prices, and Discounts for Brand-Name Drugs in the US, 2007-2018. JAMA, 321(18), 1823-1825.

- Kesselheim, A. S., et al. (2008). Clinical Equivalence of Generic and Brand-Name Drugs Used in Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA, 300(21), 2514-2526.

- AHIP. (n.d.). JAMA Study Examines Skyrocketing Prices of Newly Marketed Drugs.

- Armstrong, W. S. (2020). ART Medication Costs: A Significant Barrier to Ending the HIV Epidemic. NEJM Journal Watch.

- BioPharma Dive. (2015). NEJM joins the fray in drug pricing debate as 2 thought leaders share divergent views.

- Collier, R. (2013). Drug patents: the evergreening problem. CMAJ, 185(9), E385-E386.

- Congressional Research Service. (2020). Drug Pricing and Pharmaceutical Patenting Practices. R46221.

- International Journal of Law, Science and Social Studies. (2025). Patent Evergreening In The Pharmaceutical Industry: Legal Loophole Or Strategic Innovation?.

- I-MAK. (n.d.). Patents 101.

- IP Protection Matters. (2024). Patent Thickets, Evergreening and Product Hopping: Falsehoods vs. Fact.

- Congressional Research Service. (2024). The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing. R46679.

- The Commonwealth Fund. (2025). PBM Regulations on Drug Spending.

- American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). PBM Policies and Their Impact on Drug and Device Costs.

- The Commonwealth Fund. (2025). What Pharmacy Benefit Managers Do, and How They Contribute to Drug Spending.

- Center for American Progress. (2024). 5 Things To Know About Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

- American College of Rheumatology. (2024). Understanding Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Middlemen for Your Medications.

- The New York Times. (2024). How PBMs Are Driving Up Prescription Drug Costs.

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Direct-to-consumer advertising.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2003). Understanding the Effects of Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2003). Impact of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising on Prescription Drug Spending.

- USC Schaeffer Center. (2023). Should the Government Restrict Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising? Six Takeaways on Their Effects.

- Health Affairs. (2000). Direct-To-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising: Trends, Impact, And Implications.

- Glatter, R., & Shah, Y. (2023). Does Direct-to-Consumer Advertising Directly Harm Patients?. TIME.

- I-MAK. (2021). Humira: Overpatented, Overpriced.

- YouTube. (2024). From Breakthrough to $173 Billion Blockbuster: HUMIRA’s Patent Strategy Decoded.

- CSRxP. (2021). DOSE OF REALITY: HUMIRA: A CASE STUDY IN BIG PHARMA GREED.

- BioSpace. (2024). Opinion: Lessons From Humira on How to Tackle Unjust Extensions of Drug Monopolies With Policy.

- Campanelli, G. (2022). Feeling Evergreen: A Case Study of Humira’s Patent Extension Strategies and Retroactive Assessment of Second-Line Patent Validity. Harvard University.

- Pharmaceutical Technology. (2021). AbbVie’s successful hard-ball with Humira legal strategy unlikely to spawn.

- Hirsch, I. B. (2016). Insulin in America: A Right or a Privilege?. Diabetes Care, 39(9), 1518-1520.

- Diabetes Care. (2024). Lessons From Insulin: Policy Prescriptions for Affordable Diabetes and Obesity Medications.

- UF HealthStreet. (2018). A brief history of insulin prices.

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. (2023). Why Eli Lilly’s Insulin Price Cap Announcement Matters.

- Yale School of Medicine. (2023). The Price of Insulin: A Q&A with Kasia Lipska.

- Cefalu, W. T., et al. (2021). 100 years of insulin: Why is insulin so expensive and what can be done to control its cost?. The American Journal of Medicine, 134(11), 1333-1339.

- Stanford Medicine. (n.d.). Policy Options to Reduce Prescription Drug Costs.

- Fox News. (2025). Here’s how Trump’s tariffs on China could impact drug pricing and other healthcare costs.

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2024). Bernie Sanders describes ‘dysfunctional’ U.S. health care system—and how to fix it.

- Medicare Rights Center. (2025). New Research Confirms Importance of Drug Affordability and Low Out-of-Pocket Costs.

- Eaddy, M. T., et al. (2011). How patient cost-sharing trends affect adherence and outcomes: a literature review. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 36(1), 45–57.

- Arnold Ventures. (2025). Drug Costs and Their Impact on Care.

- Briesacher, B. A., et al. (2022). Medication adherence and characteristics of patients who spend less on basic needs to afford medications. Journal of general internal medicine, 37(Suppl 1), 127–134.

- National Pharmaceutical Council. (2022). High Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs Lead to Worse Medication Adherence Without Overall Health Care Savings.

- Magellan Health. (2024). Prescription Predicament: The Impact of Rising Drug Costs on Medication Adherence.

- Pharmacy and Therapeutics. (2014). Are Specialty Drug Prices Destroying Insurers and Hurting Consumers?.

- California Department of Insurance. (2021). Impact of Prescription Drug Costs on Health Insurance Premiums.

- The Commonwealth Fund. (2025). Drug Costs and Their Impact on Care: Insights from Medicare Patients and Providers.

- American Academy of Actuaries. (2018). Prescription Drug Spending in the U.S. Health Care System.

- Highmark. (n.d.). Prescription Drugs and Their Role in Rising Health Care Costs.

- U.S. Department of Labor. (2024). Prescription Drug Spending, Pricing Trends, and Premiums in Private Health Insurance Plans.

- Prasad, V., et al. (2020). The high cost of prescription drugs: causes and solutions. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 17(8), 465-466.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Trends in Prescription Drug Spending, 2016-2021.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2022). Prescription Drugs: Spending, Use, and Prices.

- TCU Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences. (2024). Harris Talks Economic and Policy Impacts on Drug Prices.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2023). Public Opinion on Prescription Drugs and Their Prices.

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation. (2024). Infographic: Spending on Prescription Drugs Has Been Growing Exponentially.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2025). FAQs about the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program.

- The Commonwealth Fund. (2025). Medicare Drug Price Negotiations: All You Need to Know.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (n.d.). Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Initial Implementation of Medicare Drug Pricing Provisions.

- National Pharmaceutical Council. (n.d.). IRA & The Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program.

- Epstein Becker Green. (2025). Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program: The Inflation Reduction Act “Pill Penalty” and Other IRA Reforms on the Horizon for 2026.

- The Hospitalist. (2025). Understanding the Inflation Reduction Act’s Impact on Prescription Drug Costs.

- The Times of India. (2025). Donald Trump’s crackdown at pharma: ‘Americans need lower drug prices’; sets 29 September deadline or face action.

- National Academy for State Health Policy. (2025). State Laws Passed to Lower Prescription Drug Costs: 2017–2025.

- AMCP. (n.d.). Regulation of the Prescription Drug Benefit.

- Doctors for America. (n.d.). Prescription Drug Affordability Boards and State-Led Effort to Control Drug Pricing.

- Center for American Progress. (2020). State Policy Options To Reduce Prescription Drug Spending.

- DIA Global Forum. (2024). US Drug Pricing and Reimbursement: Players, Payers, PBMs, and Prospects – A Conversation with Two Experts.

- Business Group on Health. (2025). Taking Action on Pharmacy Benefits: A Business Group on Health Viewpoint.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2024). Alternative Approaches to Reducing Prescription Drug Prices.

- Pharmacy Times. (2023). Balancing Pharmaceutical Reimbursement and Market Access With the Right Partner.

- DrugPatentWatch. (n.d.). Using DrugPatentWatch to Support Out-Licensing and Partnering Decisions.

- DrugPatentWatch. (n.d.). About DrugPatentWatch.

- PitchBook. (2025). DrugPatentWatch Company Profile.

- AdhereTech. (2025). Impact of Medication Nonadherence on Health & Quality of Life.

- Cutrona, S. L., et al. (2025). Enhancing Therapy Adherence: Impact on Clinical Outcomes, Healthcare Costs, and Patient Quality of Life. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 345.

- University of Nebraska Medical Center. (n.d.). The Association of Lower Medication Adherence and Increased Medical Spending.

- Cutler, R. L., et al. (2018). Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 8(1), e016982.

- Horne, R., et al. (2022). Medication nonadherence: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 74(11), 1499-1510.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Cost-Related Nonadherence and Mortality in Patients With Chronic Disease: A Multiyear Investigation, National Health Interview Survey, 2000–2014.

- Fox Business. (2025). Trump leveling the global medicine playing field.

- Fox Business. (2025). Trump sends letters to 17 pharmaceutical companies on reducing drug prices.

- The Economic Times. (2025). Trump pressures 17 pharma CEOs to cut US drug prices.

- The White House. (2025). Delivering Most-Favored-Nation Prescription Drug Pricing to American Patients.

- Becker’s Hospital Review. (2017). 5 quotes on managing high drug costs from Ascension’s COO.

- U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. (2019). A Price Too High.

- Patients For Affordable Drugs Now. (2025). STATEMENT: Patients For Affordable Drugs Now Responds To Trump Administration’s Most Favored Nation Letters To Drugmakers.

- The White House. (2025). Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Announces Actions to Get Americans the Best Prices in the World for Prescription Drugs.

- Jacobin. (2025). Big Pharma Puppet Groups Are Keeping Your Drug Prices High.

- ASHP. (n.d.). Drug Pricing.

- Patients For Affordable Drugs. (n.d.). Join the Fight to Lower Drug Prices.

- U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. (2024). Statement of David E. Mitchell.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2022). Estimated Budgetary Effects of Subtitle I of Reconciliation Recommendations for Prescription Drug Legislation.

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. (2022). CBO Estimates Drug Savings for Reconciliation.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2023). How CBO Estimated the Budgetary Impact of Key Prescription Drug Provisions in the 2022 Reconciliation Act.

- Congressional Budget Office. (n.d.). Prescription Drugs.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2021). CBO’s Model of Drug Price Negotiations Under the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act: Working Paper 2021-01.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2022). Prescription Drugs: Spending, Use, and Prices.

- PubMed. (2025). The Price Effects of Biosimilars in the United States.

- Office of Inspector General, HHS. (2024). Data Snapshot: Biosimilar Cost and Use Trends in Medicare Part B.