Beyond the Active Ingredient: How Excipients Quietly Dictate Drug Effectiveness

Introduction: The Unsung Heroes of Pharmaceutical Formulation

In the grand theater of medicine, the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) has always been the star of the show. It’s the molecule that fights the disease, alleviates the pain, and garners the headlines. We celebrate the discovery of new APIs as monumental breakthroughs, and rightly so. But what if I told you that this star performer often can’t even get on stage, let alone deliver a compelling performance, without an enormous, highly specialized, and largely invisible supporting cast? This cast, known in the pharmaceutical world as excipients, is the true powerhouse behind nearly every drug you’ve ever taken.

Welcome to the hidden world of excipients—the so-called “inactive” ingredients that are anything but. These are the binders, fillers, disintegrants, lubricants, coatings, and preservatives that make up the bulk of a pill, capsule, cream, or injection. They are the silent partners to the API, the unsung heroes that ensure a drug is stable, safe, effective, and actually deliverable to the human body in a form it can use.

Think of it this way: an API is like a world-class sprinter. On their own, they have incredible potential. But to win an Olympic gold medal, they need a starting block, a perfectly maintained track, specialized shoes, and a precise hydration strategy. Excipients are all of these things and more. They are the entire infrastructure that allows the API to perform its function reliably and predictably. Without them, that potent molecule might degrade on the shelf, fail to dissolve in the stomach, get destroyed by acid before it can be absorbed, or be impossible to manufacture at scale.

Demystifying the Role of Excipients

For decades, the prevailing view of excipients was that they were inert, simply volumetric fillers to create a tablet of a reasonable size from a few milligrams of potent API. The term “inactive ingredient” itself cemented this perception. However, this view is not just outdated; it’s fundamentally incorrect and, in a business context, dangerously simplistic.

Today, we understand that excipients are highly functional components that critically influence a drug’s entire lifecycle, from manufacturing efficiency to clinical performance and patient adherence. They are the master levers that formulation scientists pull to control a drug’s physical properties, chemical stability, and biological behavior. Does the drug need to release its payload instantly for fast pain relief? There’s an excipient for that. Does it need to release slowly over 24 hours to provide steady medication levels? There’s a sophisticated polymer matrix for that. Does it need to survive the acidic crucible of the stomach to be absorbed in the intestine? A precisely designed enteric coating handles that job.

The selection of excipients is a complex dance of chemistry, biology, and engineering. It’s a multidimensional optimization problem where the goal is to create a final drug product that is not only effective but also stable, manufacturable, and patient-friendly. A change in the grade of a single excipient, or a switch from one supplier to another, can have cascading effects that might render a billion-dollar drug product ineffective or even unsafe.

The Billion-Dollar Impact of “Inactive” Ingredients

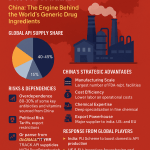

The strategic importance of excipients extends far beyond the formulation lab. It has profound implications for a pharmaceutical company’s bottom line, its market position, and its intellectual property portfolio. The global pharmaceutical excipients market was valued at approximately USD 8.6 billion in 2022 and is projected to grow significantly, reaching over USD 13.5 billion by the early 2030s, driven by the increasing demand for novel drug delivery systems, the rise of biologics, and the expansion of the generic drug market [1].

This growth underscores a critical business reality: excipients are a key battleground for competitive advantage. In the world of generic drugs, for instance, replicating the brand-name drug’s performance isn’t just about having the same API. Generic manufacturers must prove that their product is bioequivalent, meaning it performs in the same manner as the original. This often hinges on reverse-engineering the innovator’s formulation and understanding the subtle interplay of their chosen excipients.

Furthermore, clever formulation strategies using unique excipient combinations can become the basis for new patents. These “formulation patents” can extend a drug’s market exclusivity long after the initial patent on the API has expired, protecting blockbuster revenue streams for years. This is where turning data into a competitive advantage becomes paramount for business professionals in the pharmaceutical space.

A Paradigm Shift: From Inert Fillers to Functional Powerhouses

The journey of excipients from “inert fillers” to “functional enablers” represents a major paradigm shift in pharmaceutical science. This evolution has been driven by several key factors:

- The Rise of Poorly Soluble Drugs: A huge percentage of new chemical entities (NCEs) discovered today fall into the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Class II or IV, meaning they have low solubility and/or low permeability. For these drugs, the API simply will not work unless it is formulated with specialized excipients that enhance its solubility and absorption.

- Advances in Drug Delivery: The demand for more sophisticated drug delivery systems—like controlled-release, targeted delivery, and patient-friendly dosage forms (e.g., orally disintegrating tablets)—has spurred massive innovation in excipient science. We now have “smart” polymers that release drugs in response to specific physiological triggers like pH or temperature.

- The Biologics Revolution: Large-molecule drugs like monoclonal antibodies and vaccines are incredibly fragile. They require a highly specialized suite of excipients (stabilizers, cryoprotectants, buffering agents) to keep them from degrading or aggregating, both on the shelf and upon administration.

- Regulatory Scrutiny: Regulatory agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have become increasingly sophisticated in their evaluation of drug products. They recognize the profound impact of excipients on drug quality and performance, placing a greater burden on manufacturers to justify their choice of every single ingredient.

In this new paradigm, excipients are not an afterthought; they are a foundational and strategic element of drug development. Understanding their power is no longer optional—it is essential for anyone involved in the pharmaceutical industry, from the research scientist to the brand manager to the patent attorney. This article will take you on a deep dive into this fascinating world, exploring how these humble ingredients shape drug effectiveness, create commercial value, and are paving the way for the medicines of tomorrow.

The Core Functions of Excipients: More Than Just Sugar and Starch

To truly appreciate the strategic value of excipients, we must first understand the fundamental roles they play. They are the workhorses of formulation, performing a myriad of tasks that are essential for transforming a raw API into a finished, effective drug product. These functions can be broadly categorized into four critical areas: ensuring stability, enhancing bioavailability, controlling drug release, and enabling manufacturability. Let’s dissect each of these, because the devil—and the competitive advantage—is in the details.

H3: Enhancing Stability and Shelf-Life

An API’s therapeutic power is useless if it degrades before it even reaches the patient. Drugs are complex chemical entities, often susceptible to degradation from oxygen, water, light, heat, and microbial contamination. Excipients act as the drug’s personal bodyguards, protecting it from these environmental threats and ensuring it remains potent and safe throughout its intended shelf-life, which is often two years or more.

Antioxidants and Preservatives: Guarding Against Degradation

Oxidation is a primary enemy of many drug molecules. It’s the same chemical process that causes an apple to turn brown or iron to rust. An oxidative reaction can break down the API, reducing its potency and potentially creating toxic byproducts. To combat this, formulators add antioxidants. These excipients are more readily oxidized than the API. They act as sacrificial lambs, reacting with stray oxygen radicals and thereby preserving the integrity of the drug. Common examples include ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), and sodium metabisulfite. The choice of antioxidant is critical; it must be compatible with the API and other excipients and effective at very low concentrations.

Another major threat, particularly for liquid and semi-solid formulations like syrups, creams, and eye drops, is microbial contamination. Bacteria, yeasts, and molds can thrive in these water-containing systems, leading to spoilage and a serious risk of infection for the patient. Preservatives are added to prevent or inhibit microbial growth. These include parabens (e.g., methylparaben, propylparaben), benzyl alcohol, and benzalkonium chloride. Selecting the right preservative involves a delicate balance. It must be potent enough to be effective against a broad spectrum of microbes but safe enough for human consumption or application at the required concentration.

Buffering Agents: Maintaining the Perfect pH

Many drugs are most stable within a very narrow pH range. A shift in acidity or alkalinity can accelerate degradation reactions like hydrolysis (breakdown by water) or cause the drug to precipitate out of solution. This is especially critical for liquid formulations, from oral solutions to complex injectable biologics.

Buffering agents are chemical systems (typically a weak acid and its conjugate base, or a weak base and its conjugate acid) that resist changes in pH. They act like a chemical shock absorber. If an acidic or basic substance is introduced, the buffer system neutralizes it, keeping the overall pH of the formulation stable. Common buffer systems used in pharmaceuticals include citrate buffers (citric acid and sodium citrate) and phosphate buffers (sodium phosphate monobasic and dibasic). For a biologic drug like a monoclonal antibody, maintaining a precise physiological pH (around 6.0 to 7.5) is absolutely non-negotiable to prevent aggregation and loss of activity. The buffer is arguably one of the most important excipients in the formulation.

Improving Bioavailability and Absorption

Bioavailability is a cornerstone of pharmacology. It refers to the fraction of an administered drug dose that reaches the systemic circulation (i.e., the bloodstream) in an unchanged form. A drug given intravenously has 100% bioavailability by definition. But for an oral drug, the journey is far more perilous. It must first dissolve in the gastrointestinal fluids, then permeate through the gut wall into the bloodstream, all while surviving enzymatic and acidic degradation. Many modern APIs are “brick dust”—highly potent but almost completely insoluble in water. For these compounds, excipients are not just helpful; they are the sole reason the drug has any effect at all.

“It is estimated that 40% of drugs on the market and nearly 90% of molecules in the discovery pipeline are poorly water-soluble. For these drugs, formulation approaches using functional excipients are not just an option but a necessity for achieving therapeutic efficacy.”

— Adapted from industry analysis and publications on BCS Class II/IV drugs [2]

Solubility Enhancers: Unlocking the API’s Potential

How do you get “brick dust” to dissolve? You surround it with excipients that change its environment. This can be done in several ways:

- Co-solvents: For liquid formulations, formulators can use a mixture of water and one or more water-miscible organic solvents, like propylene glycol, ethanol, or glycerin. These co-solvents can increase the solubility of a hydrophobic drug by orders of magnitude.

- Surfactants (Surface Active Agents): These are amphiphilic molecules, meaning they have a water-loving (hydrophilic) head and a fat-loving (lipophilic) tail. At a certain concentration, they form tiny spheres called micelles. The lipophilic tails form a core, creating a pocket for the insoluble drug molecule to hide in, while the hydrophilic heads face outward, allowing the entire micelle to be dispersed in water. Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80) and sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) are classic examples.

- Cyclodextrins: These are fascinating, cone-shaped molecules made of sugar units. The exterior of the cone is hydrophilic, while the interior cavity is hydrophobic. They act like molecular cages, trapping a poorly soluble drug molecule inside their cavity. This drug-cyclodextrin complex is then readily soluble in water, dramatically increasing the API’s apparent solubility and bioavailability. Hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) is a widely used example.

Permeation Enhancers: Opening the Gates for Drug Delivery

Even if a drug dissolves, it still has to cross the formidable biological barrier of the intestinal epithelium. This layer of cells is designed to be selective about what it lets through. Permeation enhancers are excipients that transiently and reversibly increase the permeability of this membrane, making it easier for drug molecules to pass through. They can work through various mechanisms, such as fluidizing the cell membrane or temporarily opening the “tight junctions” between cells. Examples include certain medium-chain fatty acids and their derivatives. The use of these excipients requires extreme care, as altering a fundamental biological barrier can have safety implications if not properly controlled.

Controlling Drug Release Profiles

Not all drugs are meant to be delivered in a single, rapid burst. In many cases, the ideal therapeutic effect is achieved by maintaining a constant, steady concentration of the drug in the blood over a long period. This can reduce side effects associated with high peak concentrations and improve patient compliance by reducing dosing frequency from three times a day to just once. This is the domain of modified-release technologies, and it is almost entirely enabled by advanced excipients, primarily polymers.

Immediate-Release Formulations: For Rapid Onset of Action

For conditions like acute pain or allergies, you want the drug to work as fast as possible. Immediate-release (IR) formulations are designed to do just that. The key excipients here are disintegrants. After the tablet is swallowed, these excipients rapidly absorb water, swell, and exert a strong force that breaks the tablet apart into smaller granules. This dramatically increases the surface area of the drug exposed to the gastrointestinal fluid, leading to rapid dissolution and absorption. So-called “superdisintegrants” like croscarmellose sodium and sodium starch glycolate can absorb many times their own weight in water and cause a tablet to explode apart in under a minute.

Modified-Release Formulations: Sustained, Delayed, and Pulsatile Delivery

This is where excipient science becomes truly sophisticated.

- Sustained-Release (SR) or Extended-Release (ER): The goal here is to release the drug slowly and continuously over 8, 12, or 24 hours. The most common way to achieve this is by creating a hydrophilic matrix system. The API is mixed with a high-viscosity polymer like hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC). When the tablet is swallowed, the HPMC on the surface hydrates to form a thick, gelatinous layer. The drug must then slowly diffuse through this gel layer to be released. As the outer layer erodes, a new gel layer forms, ensuring a constant release rate over many hours. The release rate can be precisely tuned by changing the viscosity grade or concentration of the HPMC.

- Delayed-Release (DR): Some drugs are destroyed by stomach acid, or they can irritate the stomach lining. For these, we need a delayed-release formulation. This is achieved using an enteric coating. This is a special polymer coating applied to the tablet or capsule that is insoluble at the low pH of the stomach (pH 1-3) but dissolves readily at the higher pH of the small intestine (pH > 5.5). This allows the tablet to pass through the stomach intact and release its contents only where it can be properly absorbed. Common enteric polymers include cellulose acetate phthalate and acrylic acid derivatives (e.g., Eudragit®).

- Pulsatile Release: Some therapies, such as those mimicking natural circadian rhythms, require the drug to be released in pulses. This can be achieved through complex multi-layer tablets or capsules containing different populations of beads with different coatings, designed to release their payload at different times.

The Polymer Matrix: The Backbone of Controlled Release

The field of controlled release is dominated by polymers. The choice of polymer is the single most important factor determining the release mechanism and kinetics. Scientists can choose from a vast library of polymers with different properties:

- Hydrophilic vs. Hydrophobic: Does the matrix swell and erode (hydrophilic) or is it an inert scaffold that the drug leaches out of (hydrophobic, like ethylcellulose)?

- pH-Dependent vs. pH-Independent: Does the polymer’s solubility change with pH (like enteric polymers) or is it consistent throughout the GI tract?

- Biodegradable vs. Non-biodegradable: For implantable drug delivery systems, will the polymer matrix safely degrade and be absorbed by the body over time?

The ability to manipulate these polymeric excipients gives formulators god-like control over where, when, and how fast a drug is delivered in the body.

Aiding the Manufacturing Process

Finally, we come to the immensely practical and economically vital role of excipients in manufacturing. A brilliant formulation is useless if you can’t produce it reliably, consistently, and cost-effectively in batches of millions or even billions of tablets. Pharmaceutical manufacturing is a high-speed, precision operation, and excipients are the lubricants that keep the entire process running smoothly.

Binders, Fillers, and Diluents: Ensuring Uniformity and Size

Most drug doses are tiny, often just a few milligrams. It’s impossible to make a tablet that small. Fillers or diluents are added to increase the bulk volume of the powder, creating a tablet of a practical size for handling and swallowing. The most common filler is lactose, but others like microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), starch, and mannitol are also widely used.

After mixing the API and filler, the powder needs to be formed into granules with good flow properties. This is where binders come in. Binders are the “glue” that holds the ingredients together, added either as a dry powder or as a solution during a process called wet granulation. They ensure the final tablet has adequate mechanical strength so it doesn’t crumble during packaging or transport. Common binders include starch, povidone (PVP), and HPMC.

Lubricants, Glidants, and Anti-adherents: Keeping the Machines Running Smoothly

High-speed tablet presses can churn out hundreds of thousands of tablets per hour. This process involves forcing a precise volume of powder into a die cavity and then compressing it with immense force between two punches. Several excipients are critical here:

- Glidants (e.g., colloidal silicon dioxide) are added to improve the flowability of the powder blend, ensuring the die is filled uniformly and consistently every single time. Poor flow can lead to variations in tablet weight and, therefore, dosage.

- Lubricants (e.g., magnesium stearate) are added to prevent the powder from sticking to the faces of the punches and the wall of the die. Without a lubricant, the friction would be immense, leading to defects in the tablet surface and potentially seizing the machine.

- Anti-adherents also reduce sticking, particularly to the punch faces, which is crucial for producing a smooth, elegant tablet.

The selection and concentration of these processing aids are critical. For example, magnesium stearate is an excellent lubricant, but it is highly hydrophobic. If you add too much or mix it for too long, it can form a water-repellent film around the drug particles, which can slow down tablet disintegration and drug dissolution, negatively impacting bioavailability. It’s a classic example of how a seemingly simple manufacturing aid can have profound clinical consequences.

In summary, the functions of excipients are far-reaching and deeply interconnected. They are not merely passive components but active, functional materials that are meticulously chosen to solve a complex set of challenges related to stability, delivery, and manufacturing. Understanding these functions is the first step toward leveraging them for strategic advantage.

A Deep Dive into Excipient Classes and Their Mechanisms

Having established the broad functions of excipients, let’s zoom in on the specific classes of these materials. The world of excipients is vast and diverse, with hundreds of different substances available to the formulation scientist. Each class has unique chemical and physical properties that make it suitable for particular applications. Understanding the “how” and “why” behind their use is crucial for anyone involved in drug development, from R&D to business strategy. We will explore some of the most important classes, their mechanisms of action, and real-world considerations.

Binders: The Glue Holding It All Together

Binders, or adhesives, are the agents responsible for imparting mechanical strength to the tablet. During the granulation process, they “glue” the API and other excipients together to form larger, more free-flowing aggregates. During tablet compression, they ensure these granules cohere into a robust tablet that can withstand the rigors of coating, packaging, and handling without breaking or chipping (a defect known as ‘friability’).

Natural vs. Synthetic Binders

Binders can be sourced from both natural and synthetic origins, each with its own set of advantages and disadvantages.

- Natural Binders: These are derived from natural sources and have been used for decades. Examples include:

- Starch: Typically used as a paste (e.g., 5-10% w/w starch paste). It’s cheap and effective but can have high batch-to-batch variability.

- Acacia and Tragacanth: These natural gums produce very hard granules but are also prone to variability and microbial contamination.

- Gelatin: An effective binder, but its animal origin can be a concern for certain patient populations and can pose risks related to diseases like Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE).

- Synthetic/Semi-Synthetic Binders: These are chemically modified or fully synthetic polymers that offer greater control, purity, and consistency.

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP or Povidone): A highly versatile and widely used binder. It’s available in different molecular weights (grades), allowing formulators to fine-tune the binding strength. It’s soluble in both water and alcohol, making it useful in various granulation processes.

- Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC): While we discussed HPMC as a controlled-release agent, its lower viscosity grades are also excellent binders in both wet and dry granulation.

- Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC): MCC is a true multifunctional excipient. While often used as a filler, it also has excellent binding properties, especially in a process called direct compression.

Case Study: The Impact of Binder Choice on Tablet Hardness and Dissolution

Imagine you are developing a tablet for a new cardiovascular drug. You need a tablet that is strong enough to be film-coated but will still dissolve quickly to release the API.

- Scenario 1: Using a strong binder like PVP K30 at a high concentration. You produce a very hard, robust tablet with low friability. This is great for manufacturing and packaging. However, during dissolution testing, you find that the tablet barely breaks down, and only 30% of the drug is released after 45 minutes, failing the quality control specification. The strong binder has created such a dense, non-porous structure that water cannot penetrate to dissolve the drug.

- Scenario 2: Using a weaker binder or a lower concentration. The resulting tablets are softer. They might be more prone to chipping, causing issues on the coating line. However, they dissolve rapidly, releasing over 90% of the drug in 15 minutes.

- The Solution: The formulation scientist must find the sweet spot. This might involve using a moderate concentration of PVP, or perhaps switching to a different binder like a low-viscosity HPMC, or even blending two binders to achieve the desired profile. This optimization process is a perfect illustration of the critical trade-offs involved in formulation development. The choice of a single excipient—the binder—directly dictates both the manufacturability and the clinical performance of the drug product.

Fillers and Diluents: Providing the Bulk

As mentioned, the amount of API in a single dose is often too small to be handled conveniently. Fillers, also known as diluents, are added to increase the weight and size of the tablet to a manageable level (typically between 120 mg and 700 mg). The ideal filler should be inert, compatible with the API, cheap, non-hygroscopic (doesn’t readily absorb moisture), and have good biopharmaceutical properties (e.g., soluble, not impeding drug release).

Common Examples: Lactose, Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC)

- Lactose: This is the workhorse of the tablet world. Lactose, a disaccharide derived from milk, is by far the most common filler used in pharmaceuticals. It’s cheap, stable, and has excellent flow and compaction properties, especially when spray-dried. It comes in various grades (e.g., different particle sizes) to suit different manufacturing processes like wet granulation or direct compression.

- Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC): MCC is another superstar excipient. It’s a purified, partially depolymerized cellulose derived from wood pulp. It is not just a filler; it’s also an excellent binder, a disintegrant, and a glidant, all in one. Its unique fibrous nature gives it fantastic compressibility, allowing for the creation of very hard tablets at low compression forces. This makes it the cornerstone of direct compression, a modern manufacturing process that avoids the time-consuming and costly steps of wet granulation. Brands like Avicel® are ubiquitous in the industry.

Other common fillers include dicalcium phosphate (DCP), which is useful for moisture-sensitive drugs due to its non-hygroscopic nature, and mannitol, a sugar alcohol that provides a cool, pleasant mouthfeel, making it ideal for chewable or orally disintegrating tablets.

The Challenge of Lactose Intolerance and Alternative Solutions

The widespread use of lactose highlights an important issue: the potential for excipients to cause adverse effects. Lactose intolerance is a common condition where individuals lack the enzyme lactase needed to digest lactose. While the amount of lactose in a single tablet is usually very small and well below the threshold that triggers symptoms in most people, it can be a concern for severely intolerant individuals or those taking multiple medications containing lactose.

This has driven the development and use of lactose-free formulations. Pharmaceutical companies are increasingly aware of this and other sensitivities, and they often develop alternative product lines using fillers like MCC, dicalcium phosphate, or starch to cater to these patient populations. For a business, being able to market a product as “lactose-free” can be a valuable differentiator.

Disintegrants: The Agents of Breakdown

For an immediate-release solid dosage form, dissolution is preceded by disintegration. The tablet must first break apart into smaller fragments or primary particles to expose the maximum surface area of the drug to the dissolution medium. This crucial step is facilitated by disintegrants.

The traditional disintegrant was starch. When starch granules come into contact with water, they swell, and this swelling force helps to rupture the tablet matrix. However, this process can be relatively slow and inefficient.

How Superdisintegrants Revolutionized Formulation

The development of superdisintegrants in the late 20th century was a game-changer. These are excipients that are effective at much lower concentrations (typically 2-5% of the tablet weight) and have a much greater and more rapid disintegrating action. The three main families of superdisintegrants are:

- Croscarmellose Sodium: An internally cross-linked form of sodium carboxymethylcellulose. It works via a wicking and swelling mechanism, pulling water rapidly into the tablet core and swelling to break it apart.

- Sodium Starch Glycolate: A modified potato starch. It swells dramatically in water, with some grades capable of absorbing 200-300% of their weight in water.

- Crospovidone: A cross-linked, insoluble version of PVP. Unlike the others, it doesn’t swell as much but acts primarily through a combination of wicking (capillary action) and its porous particle structure, which allows it to rapidly absorb water into the tablet. It also recovers its shape after compression, which can help to push the tablet apart.

The use of superdisintegrants enables the formulation of rapidly dissolving tablets and orally disintegrating tablets (ODTs), which disintegrate in the mouth in seconds without the need for water, dramatically improving patient convenience and adherence.

Mechanism of Action: Swelling, Wicking, and Deformation

The power of disintegrants comes from a few key physical mechanisms:

- Swelling: This is the most common mechanism. The excipient absorbs water and expands, creating an internal pressure that overcomes the binding forces holding the tablet together.

- Wicking: This refers to the ability of the disintegrant to pull water into the porous network of the tablet via capillary action. This is crucial for delivering water to the other disintegrant particles deep within the tablet core.

- Deformation Recovery: Some particles, like those of crospovidone, are deformed during the high pressure of tablet compression. When they come into contact with water, they tend to return to their original shape, and this strain recovery exerts a force that contributes to disintegration.

- Repulsion: Some disintegrants carry an electrical charge. As water enters the tablet, these particles repel each other, helping to break apart the structure.

Often, a disintegrant works through a combination of these mechanisms, and their efficiency depends on their concentration, the tablet’s hardness, and the properties of the other excipients in the formulation.

H3: Coatings and Films: The Protective Outer Layer

Many tablets are not left as plain, compressed cores. They are covered with a thin layer of polymer, a process known as film coating. This coating can serve a multitude of purposes, from the purely functional to the aesthetic.

A basic film coat, often made of HPMC, can improve the tablet’s appearance, mask the unpleasant taste or odor of the drug, make the tablet easier to swallow, and protect the drug from light or moisture. It also prevents dusting of the tablet core, which is important for protecting healthcare workers from exposure to potent APIs. The color of the coat can also serve as a key branding element and a safety feature to prevent medication errors.

Enteric Coatings: Bypassing the Stomach’s Acidic Environment

As discussed earlier, enteric coatings are a brilliant example of “smart” excipient technology. These are pH-sensitive polymers. The key to their function lies in their chemical structure. They contain acidic functional groups (like carboxylic acid, -COOH).

- In the acidic environment of the stomach (pH ~1-3): The acidic groups remain protonated (as -COOH). In this form, the polymer is uncharged and therefore insoluble in water. The coating remains intact, protecting the tablet core.

- In the more neutral environment of the small intestine (pH > 5.5): The surrounding environment is less acidic, so the polymer’s acidic groups deprotonate and become ionized (as -COO⁻). This charge makes the polymer chain soluble in water. The coating rapidly dissolves, releasing the drug where it is needed.

This technology is essential for drugs like proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole) which are acid-labile, and for drugs that can cause gastric irritation, like aspirin or NSAIDs.

Film Coatings for Taste Masking and Aesthetics

Patient experience is a critical driver of adherence. If a pill tastes bitter or has a chalky texture, patients, especially children, are less likely to take it as prescribed. Taste-masking coatings are a simple yet highly effective solution. A thin polymer film (often containing flavors and sweeteners) creates a physical barrier between the drug and the patient’s taste buds.

Aesthetics also matter more than one might think. A smooth, brightly colored, elegantly shaped, and branded tablet has a higher perceived value and can improve patient confidence in the medication. Pharmaceutical companies invest significant resources in the “trade dress” of their products, and the coating is a central part of this. The choice of colorants (which are also excipients) is carefully regulated to ensure they are safe for consumption.

The deep dive into these specific classes reveals a world of incredible chemical and physical sophistication. The formulator’s palette is rich and varied, allowing for the creation of drug products that are tailored with incredible precision. For the business professional, this granularity is where the opportunities lie—in understanding how these choices impact manufacturing costs, clinical performance, patient perception, and, ultimately, the patentability and market exclusivity of a drug product.

The Critical Link Between Excipients and Patient Outcomes

While we’ve explored the technical and manufacturing roles of excipients, their most profound impact is felt at the end of the chain: by the patient. The success of any therapy is not just measured by the pharmacological action of the API but by real-world patient outcomes. This includes whether the patient takes the medication correctly (adherence), whether they tolerate it without adverse effects, and whether the drug consistently delivers its therapeutic benefit. In all these areas, excipients play a pivotal, and often underestimated, role.

Patient Adherence and Acceptability

Non-adherence to medication is a massive global health problem, leading to poor health outcomes and costing healthcare systems hundreds of billions of dollars annually. While there are many reasons for non-adherence, the physical characteristics of the drug product itself are a major contributing factor. This is where excipient-driven formulation science becomes a powerful tool for improving public health.

The Importance of Taste, Smell, and Mouthfeel

Imagine trying to convince a child to take a medication that tastes intensely bitter. It’s a daily battle for millions of parents. Excipients offer a whole toolkit to solve this problem:

- Sweeteners: Both natural sugars (sucrose, fructose) and artificial sweeteners (aspartame, sucralose, acesulfame potassium) are used to mask bitter tastes.

- Flavoring Agents: Natural and artificial flavors, from cherry and grape to mint and vanilla, can make a medicine far more palatable. The choice of flavor is often culturally specific and targeted to the intended age group.

- Taste-Masking Polymers: As mentioned, coatings can physically block taste buds from interacting with the drug. Another technique is to use ion-exchange resins. A bitter-tasting drug that is, for example, a cation can be complexed with a cationic exchange resin. The drug remains bound to the resin in the neutral pH of the mouth, preventing the bitter taste. Once in the stomach, the high concentration of ions and acidic pH cause the drug to be released from the resin for absorption.

- Mouthfeel: For chewable tablets or oral suspensions, the texture is critical. Excipients like mannitol and xylitol provide a smooth, cool sensation, while viscosity modifiers like xanthan gum in a suspension prevent a gritty or chalky feeling.

By investing in palatability, pharmaceutical companies don’t just create a “nicer” product; they create a more effective one because it is more likely to be taken as directed.

Pediatric and Geriatric Formulations: A Special Challenge

Children and the elderly represent two populations with unique needs that excipients are crucial in addressing.

- Pediatrics: Children often cannot swallow solid tablets. This necessitates liquid formulations (solutions, suspensions), orally disintegrating tablets (ODTs), or chewable tablets. Creating a stable, taste-masked liquid formulation of a poorly soluble drug is a significant technical challenge that relies heavily on the right combination of solubilizers, suspending agents, preservatives, and flavoring systems. Furthermore, some excipients that are safe for adults may not be safe for neonates or infants, whose metabolic pathways are not fully developed. For example, benzyl alcohol, a common preservative, can be toxic to newborns. Regulators place extreme scrutiny on the excipients used in pediatric products.

- Geriatrics: Elderly patients often suffer from dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and may be on multiple medications (polypharmacy). Large, hard-to-swallow tablets are a major barrier to adherence. ODTs, liquid formulations, or smaller, film-coated tablets can make a world of difference. The choice of fillers and binders to create the smallest possible tablet for a given dose is a key formulation goal for this demographic. The risk of excipient-related adverse effects is also higher in the elderly, who may have compromised renal or hepatic function.

Excipient-Related Adverse Events

The term “inactive ingredient” is a dangerous misnomer because it implies a complete lack of biological activity. While excipients do not have the intended therapeutic activity of the API, they are chemical substances being introduced into the body and can, in some cases, cause unintended and adverse biological effects.

The “Inactive Ingredient” Misnomer: When Excipients Cause Harm

History is replete with examples of excipients causing unforeseen problems. One of the most tragic was the “Elixir Sulfanilamide” disaster of 1937. A company dissolved the antibiotic sulfanilamide in diethylene glycol, a toxic industrial solvent, to create a palatable liquid version. The solvent was, in fact, a deadly poison, and over 100 people, mostly children, died. This event was the primary impetus for the passage of the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in the United States, which mandated that companies prove the safety of their products before marketing them and created the modern framework for the FDA.

While such acute toxicity is now rare due to rigorous testing, more subtle adverse events can and do occur. Propylene glycol, a common co-solvent, can cause hyperosmolality in infants. Certain dyes, once considered safe, have been linked to hyperactivity in children. This is why regulatory bodies like the FDA maintain an Inactive Ingredient Database (IID), which lists excipients used in approved drug products and provides information on the maximum amounts used for different routes of administration.

Allergies, Intolerances, and Sensitivities

A more common issue is hypersensitivity reactions. Patients can be allergic or intolerant to specific excipients.

- Lactose Intolerance: As previously discussed, this is a digestive issue.

- Celiac Disease: Patients with this autoimmune disorder must avoid gluten. Wheat starch has sometimes been used as a filler or binder, and while pharmaceutical-grade starch is highly purified, there is still a risk of trace gluten content. This has led to a push for certified gluten-free excipients.

- Allergies: True IgE-mediated allergic reactions can occur to excipients, although they are rare. Peanut oil has been used in some formulations, which poses a severe risk to allergic individuals. Sulfites, used as antioxidants, can trigger severe asthma attacks in sensitive people.

Patients and healthcare providers are becoming more aware of these issues. A patient who experiences an unexpected side effect from a medication might not be reacting to the API, but to one of the excipients. This is particularly relevant when switching between a brand-name drug and a generic version.

The Excipient Effect: How Seemingly Minor Changes Can Alter Bioequivalence

Perhaps the most subtle and complex issue is the “excipient effect,” where the specific choice and combination of excipients alter the bioavailability of the API, even if the formulation appears superficially similar to another. This is the central challenge in generic drug development.

Generic Drug Formulation and the Challenge of “Sameness”

When a generic company develops a version of an off-patent drug, they are not required to use the exact same excipients as the innovator. The innovator’s full formulation is a trade secret. The generic company must simply use the same API and demonstrate that their product is bioequivalent to the innovator’s product (the Reference Listed Drug, or RLD). Bioequivalence is typically established by conducting a study in healthy volunteers to show that the rate and extent of absorption (measured by parameters like Cmax and AUC) are statistically indistinguishable from the RLD.

However, achieving this can be tricky.

- Example: A BCS Class II Drug: Let’s say the innovator drug uses a specific grade of a surfactant and a specific process to create a solid dispersion that enhances the solubility of a poorly soluble API. The generic company might use a different surfactant or a different manufacturing process. Even if their lab-scale dissolution tests look similar, the in vivo performance could be different. The way the excipients interact with the complex environment of the human GI tract—with its bile salts, enzymes, and variable pH—can lead to unexpected differences in absorption.

- Example: A Modified-Release Product: Replicating a 24-hour controlled-release profile is even harder. The innovator might use a specific high-viscosity grade of HPMC from a particular supplier. The generic company might use HPMC with the same nominal viscosity but from a different supplier. Subtle differences in the polymer’s molecular weight distribution, particle size, or degree of substitution could lead to a slightly faster or slower release rate. This could cause the generic to fail its bioequivalence study, or worse, lead to “dose dumping” (releasing the drug too quickly) or sub-therapeutic levels in patients.

There have been documented cases where switching from a brand-name drug to a generic, or between different generics, has led to a loss of efficacy or new side effects in patients, particularly for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (where the window between an effective dose and a toxic dose is small), such as anti-epileptics or thyroid medications. While the vast majority of generics are perfectly safe and effective, these cases underscore the powerful influence that excipients wield over a drug’s ultimate performance in the body. For the patient, these “inactive” ingredients are active determinants of their health outcome.

Navigating the Regulatory and Patent Landscape of Excipients

For any business operating in the pharmaceutical sector, understanding the interplay between science, regulation, and intellectual property is the key to success. Excipients sit squarely at the intersection of these domains. The path to getting a drug approved is paved with regulatory hurdles related to excipients, while the path to commercial longevity is often protected by patents built upon clever formulation. Mastering this landscape provides a significant competitive edge.

The FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database (IID)

One of the most important tools for any pharmaceutical formulator is the FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database (IID). This publicly available database is a comprehensive list of all excipients that are part of drug products that have been approved by the FDA. It is not a list of “approved excipients,” but rather a record of their use. This is a crucial distinction.

The IID provides vital information, including:

- The name of the excipient.

- The route of administration (e.g., oral, topical, intravenous).

- The dosage form (e.g., tablet, capsule, injection).

- The maximum potency (or maximum daily exposure) of that excipient ever used in an approved product for that specific route and dosage form.

Understanding Precedent of Use and Maximum Potency

The concept of “precedent of use” is central to the regulatory process. If a formulator wants to use a common excipient like microcrystalline cellulose in a new oral tablet, they can consult the IID. They will see that it has been used in thousands of approved oral tablets. If the amount they intend to use per tablet is at or below the “maximum potency” listed in the IID for an oral tablet, the regulatory path is relatively straightforward. They can justify its use based on this extensive precedent, and the FDA will likely not require additional safety studies for the excipient itself.

However, if a company wants to use an excipient in a way that has no precedent—for example, using a higher amount than is listed in the IID, or using an excipient via a new route (e.g., using a previously oral-only excipient in an injectable)—they face a much higher regulatory burden. They would likely need to conduct extensive toxicology studies to prove the safety of the excipient at that new level or for that new route, which is a costly and time-consuming process. This system encourages formulators to stick with well-established excipients, creating a high barrier to entry for new ones.

GRAS, Novel Excipients, and the Path to Approval

There are two main pathways for an excipient to be accepted for use. The first is the one described above: leveraging the precedent of use documented in the IID. The second involves substances that are Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). This designation is typically for food ingredients. If a substance has a long history of safe use in food, it may be considered GRAS. Many common pharmaceutical excipients, like starch, sucrose, and gelatin, are also common food ingredients and fall under this category.

The most challenging path is the approval of a novel excipient—a substance that has no history of use in approved drug products in a given jurisdiction.

The High Bar for Introducing a New Excipient

Why would a company go through the enormous trouble and expense of developing and getting a novel excipient approved? Because it might be the only way to formulate a particularly challenging API, or it might offer functionality that is impossible to achieve with existing excipients (e.g., a new polymer for an ultra-long-acting implant).

The process for approving a novel excipient is almost as rigorous as approving a new API. The excipient manufacturer must compile a massive data package, including detailed chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) information, as well as a full suite of toxicology and safety studies in animals. This data can then be submitted to the FDA in a Drug Master File (DMF). A pharmaceutical company wishing to use this novel excipient in their drug product can then reference this DMF in their New Drug Application (NDA).

This high bar means that true innovation in the form of completely new excipient molecules is relatively slow. More common is the development of new grades or co-processed versions of existing excipients, which can often follow a less burdensome regulatory path.

Intellectual Property and Formulation Patents

This is where the strategic business implications of excipients truly come to the fore. In the pharmaceutical industry, market exclusivity is everything. The initial period of exclusivity is provided by the patent on the new API, which typically lasts for 20 years from the filing date. But what happens when that patent is about to expire, exposing a multi-billion dollar drug to generic competition? This is where formulation patents, built on the clever use of excipients, become a company’s most valuable defensive weapon.

How Excipients Can Extend Market Exclusivity

A company can’t re-patent the same API. But it can patent a new, improved formulation of that API that offers a tangible benefit to the patient. This is a common “life cycle management” strategy.

- Switching from Immediate-Release to Extended-Release: A company might first launch a drug as an immediate-release tablet taken three times a day. A few years before the API patent expires, they can launch a new, once-daily extended-release version. This new version, enabled by specific controlled-release polymers (excipients), is a separate invention and can be protected by its own set of patents. These formulation patents can provide an additional 5, 10, or even 20 years of market protection. The company then works to switch patients over to the new, more convenient formulation before the original version faces generic competition.

- Creating a New Dosage Form: A company might have a successful injectable drug but then develops a new oral version using advanced solubility-enhancing excipients like cyclodextrins or lipid-based delivery systems. This new oral formulation would be a major innovation and highly patentable.

- Developing a Combination Product: Combining two different APIs into a single tablet can improve adherence for patients who need both drugs. The challenge lies in formulating two potentially incompatible APIs together, which requires a careful selection of excipients to ensure stability and proper release of both drugs. The resulting fixed-dose combination product can be patented.

These patents are not on the API itself, but on the combination of the API with a specific set of excipients to achieve a specific outcome (e.g., “a tablet comprising Drug X and polymer Y, wherein the drug is released over 24 hours”).

Leveraging Databases like DrugPatentWatch to Track Formulation Patents

For both innovator and generic companies, staying on top of this complex patent landscape is critical for strategic planning. This is where specialized databases and intelligence services become invaluable. For instance, a platform like DrugPatentWatch provides comprehensive data on drug patents, including those related to formulations and methods of use.

- For an Innovator Company: A brand manager can use such a service to monitor the competitive landscape, see what kinds of life cycle management strategies competitors are using, and identify potential white space for their own products. Are competitors patenting new pediatric formulations? New controlled-release systems? This intelligence can inform their own R&D and intellectual property strategy.

- For a Generic Company: A business development team planning to launch a generic version of a drug needs to know exactly which patents they need to challenge or design around. The API patent might be expiring, but is there a formidable wall of formulation patents still in effect? DrugPatentWatch can help them dissect this patent estate. They can analyze the claims of the formulation patents to see if they can develop a non-infringing formulation. For example, if the innovator’s patent claims the use of HPMC to achieve extended release, the generic company might experiment with a different polymer, like polyethylene oxide, to achieve a similar release profile, thereby “designing around” the patent.

In this high-stakes game of pharmaceutical chess, excipients are not just pawns; they are strategic pieces that can be used to control the board, defend territory, and secure victory. Understanding their regulatory and IP implications is non-negotiable for any serious player in the industry.

The Future of Excipients: Innovation on the Horizon

The world of pharmaceutical excipients is far from static. As our understanding of biology deepens and our drug development targets become more complex, the demands placed on drug delivery systems are intensifying. This is fueling a new wave of innovation in excipient science, pushing the boundaries of what these “inactive” ingredients can do. The excipients of tomorrow will be smarter, more functional, and more integrated into the therapeutic process than ever before.

Smart Excipients and Stimuli-Responsive Polymers

One of the most exciting frontiers is the development of “smart” excipients, particularly stimuli-responsive polymers. These are materials designed to undergo a significant change in their physical or chemical properties in response to a specific biological or external trigger. This allows for drug delivery systems that are not just controlled, but are truly “intelligent” and interactive.

Imagine a drug delivery system that only releases its payload in the presence of a specific enzyme that is overexpressed in tumor cells. This would allow for highly targeted cancer therapy, maximizing the drug’s effect on the tumor while minimizing its exposure to healthy tissue, thereby reducing side effects. This is the promise of enzyme-responsive polymers.

Other examples of stimuli include:

- pH: We already have simple pH-responsive polymers in enteric coatings. Future versions could be tuned to respond to much more subtle pH changes within different tissues or even cellular compartments.

- Temperature: Thermo-responsive polymers can exist as a liquid at room temperature (for easy injection) but then instantly form a solid gel depot upon injection into the body (at 37°C). This gel can then release a drug slowly over weeks or months.

- Light: Photosensitive polymers can be designed to release a drug when exposed to a specific wavelength of light, allowing for on-demand, externally controlled drug administration.

- Glucose: For diabetes management, researchers are developing glucose-responsive systems where a polymer matrix containing insulin swells and releases the hormone only when blood glucose levels are high.

These technologies are moving from the academic lab to preclinical and clinical development and will require a new generation of excipients that are not just functional, but are themselves part of the therapeutic mechanism.

Co-processed Excipients: The Rise of Multifunctional Ingredients

While novel excipient molecules face a high regulatory bar, significant innovation is happening in the field of co-processed excipients. This is a clever approach where two or more existing, well-established excipients are combined using a specific manufacturing process (like spray drying or granulation) to create a new, synergistic excipient with superior properties.

Because the individual components are already known to regulators, the co-processed version often has a more streamlined regulatory path than a completely new chemical entity. The goal is to create multifunctional, “plug-and-play” solutions for formulators.

For example, Silicified Microcrystalline Cellulose (SMCC) is a co-processed excipient made of MCC and colloidal silicon dioxide. It combines the excellent binding properties of MCC with the flow-enhancing properties of silicon dioxide, resulting in a product with significantly improved compressibility and flowability. This makes it a high-performance excipient for direct compression, simplifying the formulation process and improving manufacturing efficiency.

Another example is co-processed lactose and starch, which can offer better binding and disintegration than a simple physical mixture of the two. This trend towards high-functionality, integrated excipients will continue, as it allows drug manufacturers to simplify their formulations, reduce the number of ingredients, and shorten development timelines.

Applications in Biologics and Advanced Therapies (e.g., mRNA vaccines)

The rise of biologics—large, complex molecules like proteins, antibodies, and nucleic acids—has created a whole new set of challenges and opportunities for excipient science. These molecules are incredibly fragile and sensitive to their environment.

- Stabilization of Biologics: Formulating a stable liquid biologic requires a sophisticated cocktail of excipients. Buffers (like histidine or citrate) are needed to control pH. Stabilizers (like amino acids, e.g., arginine, or sugars, e.g., sucrose and trehalose) are used to prevent the protein from unfolding or aggregating. Surfactants (like Polysorbate 80) are included at very low concentrations to prevent the protein from adsorbing to the surface of the vial or syringe.

- Lyophilization (Freeze-Drying): For many biologics that are not stable in liquid form long-term, they are freeze-dried into a solid powder (a “cake”). This process requires cryoprotectants and lyoprotectants (often sugars like sucrose or trehalose) which form a glassy matrix around the protein molecules, protecting them from the stresses of freezing and drying.

- mRNA Vaccines: The stunning success of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna was, in many ways, an excipient and drug delivery triumph. The mRNA itself is extremely unstable. The breakthrough was enclosing it in a Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP). This LNP is a sophisticated drug delivery system, and its components are essentially excipients. It typically consists of four different types of lipids:

- An ionizable cationic lipid: This is positively charged at a low pH (during manufacturing, to bind the negatively charged mRNA) but neutral at physiological pH (to reduce toxicity). This is the key “smart” component.

- A PEGylated lipid: A lipid with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) chain attached. This forms a hydrophilic stealth coating on the outside of the nanoparticle, helping it to evade the immune system and prolong its circulation time.

- A phospholipid: A structural lipid that helps form the bilayer of the nanoparticle.

- Cholesterol: Another structural lipid that helps stabilize the nanoparticle and control its fluidity.

The precise ratio and chemical nature of these four lipid excipients are what make the vaccine work. They protect the mRNA, facilitate its uptake into cells, and help it escape the endosome to reach the cytoplasm where it can be translated into the spike protein. This is perhaps the most powerful example to date of excipients not just supporting an API, but forming an integral, indispensable part of the drug product’s mechanism of action.

As we move further into an era of cell therapies, gene therapies, and other advanced therapeutic modalities, the role of excipients will only become more critical and more complex. They will be the enabling materials that make these futuristic medicines a clinical reality.

Conclusion: Elevating Excipients from Afterthought to Strategic Imperative

We began this journey by calling excipients the “unsung heroes” of pharmaceutical formulation. Throughout this deep dive, we have seen how this moniker, while fitting, may still understate their importance. They are not merely helpers; they are fundamental enablers. They are the architects of stability, the gatekeepers of bioavailability, the conductors of drug release, and the grease in the gears of manufacturing. They are the bridge between a promising molecule in a test tube and a life-saving medicine in a patient’s hand.

The paradigm has irrevocably shifted. The notion of an “inactive” ingredient is a relic of a simpler time. In the modern pharmaceutical landscape, characterized by complex molecules, sophisticated delivery demands, and fierce market competition, excipients are active, functional, and strategic assets.

For the scientist in the lab, they are a toolkit of incredible power and precision. For the clinician and the patient, they are the silent determinants of adherence, safety, and ultimately, therapeutic success. And for the business professional, the patent attorney, and the brand manager, they represent a critical nexus of regulation, intellectual property, and competitive strategy. Understanding how to leverage formulation science and excipient selection can mean the difference between a blockbuster drug with a long and profitable life and a promising API that never realizes its potential.

As we look to the future—to personalized medicine, to intelligent drug delivery systems, to the complex challenges of formulating advanced biologics and gene therapies—the role of excipients will only continue to expand. They will become more integrated, more functional, and more “active” than ever before. The companies, scientists, and business leaders who recognize this and place the science of excipients at the core of their strategy will be the ones who lead the next generation of medical innovation. The supporting cast is ready for its leading role.

Key Takeaways

- Excipients are Not “Inactive”: They are highly functional components that are critical for a drug’s stability, bioavailability, release profile, and manufacturability. The term “inactive ingredient” is a misnomer.

- Core Functions are Diverse: Excipients perform essential jobs, including protecting the API from degradation (antioxidants, buffers), enhancing absorption (solubilizers, permeation enhancers), controlling the rate and location of drug release (polymers), and enabling efficient manufacturing (binders, lubricants).

- Direct Impact on Patient Outcomes: The choice of excipients directly influences patient adherence through taste-masking and ease of swallowing. They can also be a source of adverse events, such as allergic reactions or intolerances (e.g., lactose), making their careful selection critical.

- Central to Generic vs. Brand Competition: Generic drugs must be bioequivalent to the brand-name product. Achieving this often depends on successfully navigating the “excipient effect,” where different excipients can lead to different in vivo performance, even if the API is identical.

- A Key Lever for Intellectual Property: Clever use of excipients to create new formulations (e.g., extended-release versions) is a primary strategy for life cycle management, allowing companies to file new patents that can extend market exclusivity long after the original API patent expires.

- The Future is Functional and Integrated: Innovation is driving the development of “smart” excipients that respond to biological triggers, co-processed excipients that offer superior performance, and highly specialized delivery systems (like Lipid Nanoparticles for mRNA) where the excipients are integral to the drug’s mechanism of action.

- Regulatory & Business Strategy Nexus: Navigating the FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database (IID) and understanding the high bar for novel excipient approval is crucial. At the same time, leveraging databases like DrugPatentWatch to monitor formulation patents is essential for competitive intelligence and strategic planning.

FAQ Section

1. Can an excipient in a generic drug cause a different side effect profile than the brand-name drug?

Yes, absolutely. While the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is the same, generic manufacturers can use different excipients than the innovator. If a patient has a specific allergy or intolerance to an excipient used in the generic formulation (e.g., a certain dye, lactose, or a specific polymer) that was not present in the brand-name drug, they could experience a new adverse effect. While the vast majority of patients switch to generics with no issues, this is a recognized phenomenon, particularly for patients with known sensitivities.

2. What is the biggest hurdle in getting a “novel excipient” approved by regulatory bodies like the FDA?

The biggest hurdle is the immense cost and time required to generate the necessary safety and toxicology data. A novel excipient is treated almost like a new drug itself. The manufacturer must provide a comprehensive data package proving its safety for human use, including detailed manufacturing information, characterization, and extensive animal toxicology studies. Because there is no “precedent of use” documented in the FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database (IID), the regulatory risk and financial investment are substantial. This high barrier means that true novel excipient approval is rare and is typically only pursued when the new excipient unlocks a critical, otherwise impossible, formulation capability.

3. How are excipients playing a role in the stability of mRNA vaccines?

Excipients are not just playing a role; they are the core enabling technology for mRNA vaccines. The mRNA molecule is incredibly fragile. Its stability and delivery are entirely dependent on the Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) that encapsulates it. This LNP is composed of four key lipid excipients: an ionizable cationic lipid to bind the mRNA, a PEGylated lipid to provide a “stealth” coating, and a phospholipid and cholesterol for structural integrity. In addition to the LNP, the formulation also contains excipients like sucrose (a cryoprotectant to protect during freezing) and various salts (buffering agents) to maintain the correct pH and tonicity. Without this precise cocktail of excipients, the mRNA would degrade in seconds and would be unable to enter human cells.

4. If an excipient is ‘Generally Recognized as Safe’ (GRAS), does that mean it’s safe for all patient populations and routes of administration?

No, not necessarily. The GRAS designation typically applies to the use of a substance in food, meaning it’s considered safe for oral consumption by the general population. However, “safe” is context-dependent. An excipient that is safe when eaten might not be safe when injected, inhaled, or applied to a sensitive area like the eye. Furthermore, a substance safe for a healthy adult might pose a risk to a specific population, like a premature infant whose metabolic systems are immature. For example, the preservative benzyl alcohol is GRAS for adults but can be toxic to neonates. Therefore, regulators evaluate the safety of an excipient based on the specific dose, route of administration, and intended patient population for each drug product.

5. How can a company use excipient selection as a competitive strategy to defend against generic competition, even after the API patent expires?

This is a core life cycle management strategy. An innovator company can develop a new and improved version of their drug that is based on a complex formulation, then patent that formulation. For example, they might use a highly specialized, proprietary polymer matrix to create a once-daily, extended-release tablet that is more convenient for patients than the original twice-daily version. This new formulation patent protects the method of achieving that 24-hour release with specific excipients. When generic companies arrive, they cannot simply copy this formulation. They must “design around” the patent, which can be technically challenging, costly, and time-consuming. They would have to develop their own extended-release system using different excipients or methods, and prove it is bioequivalent, giving the innovator company several more years of market exclusivity for their advanced product.

References

[1] Precedence Research. (2023). Pharmaceutical Excipients Market (By Product: Organic Chemicals, Inorganic Chemicals; By Functionality: Fillers & Diluents, Binders, Suspending & Viscosity Agents, Coatings, Flavoring Agents, Disintegrants, Colorants, Lubricants & Glidants; By Formulation: Oral Formulations, Topical Formulations, Parenteral Formulations) – Global Industry Analysis, Size, Share, Growth, Trends, Regional Outlook, and Forecast 2023-2032.

[2] Williams, H. D., Trevaskis, N. L., Charman, S. A., Shanker, R. M., Charman, W. N., Pouton, C. W., & Porter, C. J. (2013). Strategies to address low drug solubility in discovery and development. Pharmacological reviews, 65(1), 315–499. (Note: Statistic adapted and generalized from data common in such reviews).